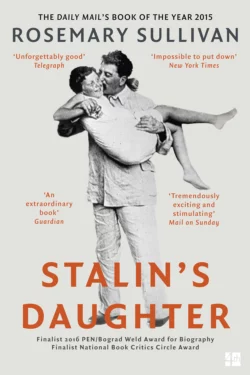

Stalin’s Daughter: The Extraordinary and Tumultuous Life of Svetlana Alliluyeva

Rosemary Sullivan

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Историческая литература

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 1252.89 ₽

Статус: В продаже

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: Winner of the Hilary Weston Writers’ Trust Prize for Non-FictionA New York Times Notable Book of 2015A painstakingly researched, revelatory biography of Svetlana Stalin, a woman fated to live her life in the shadow of one of history’s most monstrous dictators – her father, Josef Stalin.Born in the early years of the Soviet Union, Svetlana Stalin spent her youth inside the walls of the Kremlin. Communist Party privilege protected her from the mass starvation and purges that haunted Russia, but she did not escape tragedy – the loss of everyone she loved, including her mother, two brothers, aunts and uncles, and a lover twice her age, deliberately exiled to Siberia by her father.As she gradually learned about the extent of her father’s brutality after his death, Svetlana could no longer keep quiet and in 1967 shocked the world by defecting to the United States – leaving her two children behind. But although she was never a part of her father’s regime, she could not escape his legacy. Her life in America was fractured; she moved frequently, married disastrously, shunned other Russian exiles, and ultimately died in poverty in Spring Green, Wisconsin.With access to KGB, CIA, and Soviet government archives, as well as the close cooperation of Svetlana’s daughter, Rosemary Sullivan pieces together Svetlana’s incredible life in a masterful account of unprecedented intimacy. Epic in scope, it’s a revolutionary biography of a woman doomed to be a political prisoner of her father’s name. Sullivan explores a complicated character in her broader context without ever losing sight of her powerfully human story, in the process opening a closed, brutal world that continues to fascinate us.