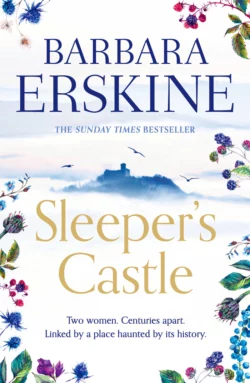

Sleeper’s Castle: An epic historical romance from the Sunday Times bestseller

Barbara Erskine

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Фольклор

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 1926.79 ₽

Статус: В продаже

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: The Sunday Times Top Ten bestseller.Two women, centuries apart. Linked in a place haunted by its history . . .Separated by more than six hundred years of history, two women are drawn together by Sleeper’s Castle, a house steeped in memory and magic. This is an epic tale of forbidden love, cruel revenge and a war that time can’t forget.Grieving and lost, Miranda has moved to Hay to escape, and slowly she feels herself coming to life in the solitude of the mountains. But her vivid dreams at Sleeper’s Castle introduce her to Catrin, a young women whose gift for foretelling the future embroiled her in a bloody revolt against English rule – many centuries ago.An unbreakable connection is forged across history. Catrin is reaching out . . . and only Miranda can help. But time is running out…Sunday Times bestselling author Barbara Erskine returns to Hay in the year that marks the 30th anniversary of her sensational debut bestseller, Lady of Hay.