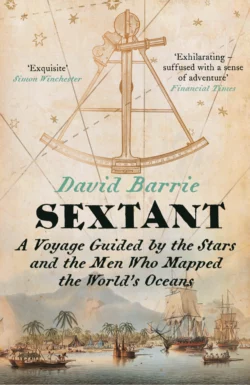

Sextant: A Voyage Guided by the Stars and the Men Who Mapped the World’s Oceans

David Barrie

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Биографии и мемуары

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 698.87 ₽

Статус: В продаже

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: In the tradition of Dava Sobel′s ‘Longitude’ comes sailing expert David Barrie′s compelling and dramatic tale of invention and discovery – an eloquent elegy to one of the most important navigational instruments ever created, and the daring mariners who used it to explore, conquer, and map the world.This book is an eloquent elegy to the sextant – the odd-looking instrument that changed the world. It tells the story of how and why the sextant was invented; how it saved the lives of many navigators in wild and dangerous seas—as well as its vital role in man’s attempts to map the world. Among the protagonists in this story are Captain James Cook, Matthew Flinders – the first man to circumnavigate Australia, the great French navigator, Laperouse, who built on Cook′s work in the exploring the Pacific during the 1780s, but never made it home, Robert Fitz-Roy of the Beagle, George Vancouver, Frank Worsley of the Endurance, and Joshua Slocum, the redoubtable old ‘lunarian’ and first single-handed round-the-world yachtsman. Much of the book is set amidst the waves of the Pacific ocean as explorers searched for the great southern ocean, charted the coasts of Australia, New Zealand, California, Canada, Alaska as well as the Pacific islands. Their stories are interwoven with the author’s account of his own maiden voyage on Saecwen in 1973, and they are infused with his sense of wonder and dramatic discovery.A heady mix of adventure, science, mathematics and derring-do, Sextant is a timeless tale of sea-faring and exploration, a love letter to the sea which will appeal to the many thousands of readers who loved Dava Sobel’s Longitude as well as the work of Simon Winchester, Patrick O’Brian and Richard Holmes. This is narrative history and storytelling at its best.