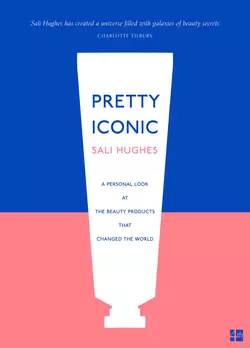

Pretty Iconic: A Personal Look at the Beauty Products that Changed the World

Sali Hughes

Over 200 iconic products that are among the best and most influential in the beauty world – past, present and future.‘Sali Hughes has created a universe filled with galaxies of beauty secrets’ Charlotte TilburyPacked full of beauty wisdom, Pretty Iconic takes us from the evocative smell of Johnson’s baby lotion through to Simple Face wipes, NARS Orgasm and beyond, looking at the formative role beauty plays in our lives.Considering which much-hyped beauty buys are worth the buzz, and who they might be best suited for, in Pretty Iconic Sali Hughes uses her witty, inclusive and discerning style to look at some of the most significant products in beauty – from treasured classics such as Chanel No 5, to life-changers such as Babyliss Big Hair, and the more recent releases from Charlotte Tilbury, Sunday Riley and others that are shaping the beauty industry today.Delving into the products that are simply the best at what they do, the inventions that changed our perception of beauty and the launches that completely broke the mould, Pretty Iconic is a treasure trove of knowledge from Britain’s most trusted beauty writer.

Copyright (#u05ae0cd1-1c58-5ce0-8b84-4eba8a4d7653)

4th Estate

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.4thEstate.co.uk (http://www.4thestate.co.uk/)

First published in Great Britain by 4th Estate in 2016

Text copyright © Pretty Honest Ltd 2016

Cover credit © Heike Schussler

All photographs © Jake Walters 2016

www.Jakewalters.com (http://www.Jakewalters.com)

Illustrations by Mel Elliott

www.ilovemel.me (http://www.ilovemel.me)

The right of Sali Hughes to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Design and Patents Act 1988.

Design and Art Direction by BLOK

www.blokdesign.co.uk (http://www.blokdesign.co.uk)

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008194536

Ebook Edition © June 2018 ISBN: 9780008194543

Version: 2018-06-12

For Marvin and Arthur

This was Mum’s Ferraris and Pokémon

Contents

Cover (#ud1fed975-5fe9-57e4-a21a-2bf7e368e085)

Title Page (#litres_trial_promo)

Copyright

Dedication (#ue50c3158-53c5-5515-ada0-fd0f41210596)

Introduction

The Icons (#ue63d7269-22e9-5bf8-9d29-28a7b0c28bd8)

The Nostalgics (#litres_trial_promo)

The Gamechangers (#litres_trial_promo)

The Rites of Passage (#litres_trial_promo)

The Future Icons (#litres_trial_promo)

Picture Credits

Index

Acknowledgements

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher

Introduction (#u05ae0cd1-1c58-5ce0-8b84-4eba8a4d7653)

In my loft, there’s a red plastic B&Q toolbox filled with make-up no longer fit for purpose but that I’ll never, ever throw away. There’s a dried out, once-black Body Shop eyeliner pen that my mother put in my Christmas stocking circa 1989, which I wore with cut-off Levi’s and a lycra bodysuit to Cardiff’s Square Club. There’s a pot of Clinique face powder in a dreadfully unsuitable shade of pink, that I’d saved at least six weeks’ pocket money to buy before realising it made me look embalmed. The Rimmel lilac eye palette I was convinced made me appear 18, the apricot lip balm bought for me by fourth form squeeze Hywel White, a dry, cracked Kryolan professional concealer palette bought in haste less than a year later, when I heard I’d be making up the Pet Shop Boys, the half-used Prescriptives foundation given to me by my boss because I could never have afforded my own, and the Mary Quant eyeshadows I found in a dusty box in a discount chemist on South Molton Street, and thought I’d won the lottery. These aren’t just products. This isn’t just a toolbox. It’s a time capsule, and everything in it takes me back to a moment, a hope, a mistake, an achievement. These unassuming bits and pieces each have their own significance and collectively make something as potent and meaningful as any long-saved C90 compilation. They’re my beauty mixtape.

But like any true music lover, I always want to hear something new that excites me just as much. And so it is with beauty. Good job, because I’m sent around 2000 new beauty products a year, from designer fragrances and state of the art skincare, to supermarket shampoos and lipsticks costing less than a two pinter of milk – all of them promising something new and extraordinary. It’s an extremely fortunate and wonderful position to be in (teenage me is never far from memory, and believe me, she’s having kittens), but not one without some stress. Storage and eating surfaces aside, I worry constantly that I’ll miss something wonderful. A product so brilliant, so revolutionary and life-changing, that it will deserve to become a beauty icon, used by millions, remembered always, popped in someone’s future treasured toolbox.

But what makes an icon? Quality alone is neither enough nor strictly the point. The beauty products in this book aren’t always, in my view, the best – at least not for me personally. Very many of my all time favourites are not here (and as ever, everything in this book has been chosen by me and me alone, with absolutely no commercial consideration). I happen to prefer By Terry Touche Veloutée and Clinique Airbrush Concealer to the mighty YSL Touche Éclat pen, but in terms of influence, memorability and its creation of an entire beauty category, the latter wins by a country mile. Likewise, you may not love Chanel No 5. But the fact is, you will probably still have an opinion on what is, without question, the towering icon of perfumery. You might not find Estée Lauder Advanced Night Repair ideal for your skin but in all likelihood, the serum you do love would not exist without it. These three items, in their own ways, changed how countless beauty products were designed and used thereafter. They are reference points, or the stars of a beauty ‘moment’, or so familiar and relied upon that they’re practically part of the family.

While to many, beauty products are silly, an irrelevance, the currency of the vain and the shallow, they are, to me, the furniture of our lives. Just as we chart life’s journey through music, food and places, I also attribute the same importance and sentimentality to the beauty products I saw, touched, and smelled all around me. The flipping of a lid on a bottle of Johnson’s baby lotion triggers a Proustian rush. I’m immediately back in my grandmother’s living room, my clean pyjamas warming on the fireguard, the soothing hum of Antiques Roadshow and the rattle of a twin tub washer in the background. I don’t just remember my first kiss, I remember the Miss Selfridge Copperknockers lipstick smeared messily over my cheeks afterwards. My first ever gig was notable not only because I saw The Smiths on their last tour, but because I’d stolen my mum’s Rimmel lipliner and Givenchy Ysatis perfume for this life-changing occasion. A memorable beauty product can transport me to my nan’s backstreet curl and set parlour, my teenage cabin bed, a school disco or my wedding day. When I look back at pivotal moments in my life, I can almost always remember the cosmetics and toiletries that accompanied me, and how I came to be wearing them. These are the lotions, potions, creams, colours and powders that defined how we presented ourselves to the outside world. They were companions at major life events. The perfumes that gave us backbone for important job interviews, the make-up chosen to come on our first dates with a partner, the toiletries taken on family holidays, the little luxury bought with a first pay packet.

It’s easy to forget that these cosy, familiar make-up, skincare and toiletries of our youth were often born from world-changing innovation and where particularly interesting, I’ve tried to provide some context. Likewise, if I feel a product is oft-misunderstood or unfairly maligned, I’ve suggested best practice techniques and tips, on how better to utilise them. In Future Icons are some products that, to me, represent either an unforgettable moment – welcome or otherwise – or a great advance in beauty. Whether history will agree with me remains to be seen.

Most importantly, I should say that my interpretation of the word ‘icon’ is wholly subjective and seen very much through the lens of a 41-year-old British woman and is therefore a shamelessly Western view of products. I absolutely acknowledge that Japanese beauty rituals and technology, for just one example, have always been extremely influential and that in recent years, Korean products have changed our beauty culture, but they don’t have the same personal meaning to me (no doubt they will to our children). Radox, Poison and Sun-In – these are the products that made my life. There will, I hope, be some products you remember from your own upbringing. The shampoo that sat at the corner of your childhood bath, the pot of face cream your mother kept on the bedside table, perhaps. There will no doubt be others that are entirely new to you and equally, some omissions that figure hugely in your past or present but not in my own – I would really love to hear what they are.

Chanel No 5

In perfume-nerd circles, saying Chanel No 5 is your favourite perfume is as obvious and dreary as declaring Citizen Kane your favourite film, Shakespeare and the Mona Lisa your favourite playwright and painting. But sometimes, things are seen as the best because they simply are. There’s no use fighting a towering icon just to be contrary and interesting. And even if you don’t like No 5 (and very many genuinely don’t – smell is a wholly subjective business), you should still respect this remarkable 94-year-old French perfume and what is arguably the most iconic and recognisable beauty product of all time.

No 5 was created by the extraordinarily clever and talented Russian-French perfumer Ernest Beaux, but, for me, his creation is Coco Chanel from crystal stopper to basenote. The couturier had been obsessed with cleanliness from a young age, but was frustrated with the ephemeral characteristics of fresh-smelling citrus colognes. She wanted something stronger, longer lasting, more characterful, and so Beaux mixed traditional floral extracts with aldehydes – isolated chemicals that artificially gave a clean smell, but stuck around on the skin until bedtime. These synthetics were deemed inferior and tacky in 1921, but Coco gave not a damn. Beaux made up ten versions of the scent, numbered 1–5 and 20–24. Superstitious Coco chose five, her lucky number. She packaged it in a typically unfussy flacon, inspired by men’s toiletries and adorned with nothing more than a square label and simple type – a pretty subversive move in itself, when luxury perfumes came in big, blowsy balloon-atomisers. The No 5 bottle – since then, the subject of works by artists and photographers such as Andy Warhol, Louis-Nicolas Darbon and Ed Feingersh in his portraits of Marilyn Monroe – is as recognisable a French icon as the Eiffel Tower.

The scent itself – powdery, fizzy, sexy, grown-up, chic and refined – is magnificent, whether or not your particular bag (though impressively, it remains the world’s bestselling scent). But for me it goes way beyond smell. It’s true to say that outside those with my immediate family, the most enduring relationship of my life has been with No 5. I discovered it at 12 years old and wore it with vintage Levi’s and Smiths T-shirts at school discos; I spritzed it over my uniform when I ran away from home three years later. It moved to London with me when I had nothing but a PE bag worth of belongings, it lost my virginity with me, it came on my driving test, it laced my smiley T-shirts and accompanied me to acid house raves (thankfully, not on the same day). Naturally, it was a guest at my wedding. Some years later, broken, confused and tearful, I considered no other fragrance for my father’s funeral. On such a hideous and unwanted day, I needed an old friend to stop me from falling.

Nowadays, I don’t wear No 5 every day – perhaps once or twice a month. I love perfume too much to be monogamous, and besides, while familiarity could never breed contempt, to use it daily is to forget how wonderful it really is. But when I have a big work day, or special occasion, I unfailingly turn to its strength, unflappable appropriateness (No 5 is literally never a bad idea), respect for occasion and soft, welcoming femininity. I call No 5 my backbone in a bottle, the loaded pistol in my knickers; with it, I am instantly bolstered and prepared for whatever life throws at me. Like Calpol, cheese and red wine, I’ll simply never not have it in the house.

MAC Ruby Woo Lipstick

To choose a favourite red lipstick is impossible. You might as well ask me to name my favourite child. But ask me for the most iconic, and the answer comes easily. Ruby Woo is an ultra-bold phone-box red launched in 1999, effectively as a slightly more vivid, super-matte version of MAC’s (already matte) Russian Red, the lipstick favoured by Madonna during the ‘Who’s Girl?’ and ‘Blond Ambition’ years (and consequently bought by me, of course). Ruby Woo became an instant bestseller and, until a Kardashian-Jenner told the world she wore its less interesting stablemate Velvet Teddy, was MAC’s most popular lipstick – no mean feat when you have both a colour and formulation that’s pretty hard for most women to wear. Ruby Woo is extremely matte. Glide silkily across the mouth like butter on hot toast, it does not. It more chugs along like wellies down a wet slide. What it gives in superb longevity, it robs in moisture. Its blue base, while fabulous for whitening teeth and making an impact, demands the level of confidence of a seasoned red-wearer.

But none of this matters, because Ruby Woo is meant to be a loud statement by an uncompromising woman. It’s not meant to be pretty, it’s designed to be fabulous, and on that it more than delivers. It looks glorious against extreme hair colours – platinum blonde or jet black – and on very pale, very olive or very dark skin (Dita Von Teese is a Ruby Woo fan – it looks sublime on her) and is the perfect vintage rockabilly red. It’s the kind of lipstick that belongs with tattoos, leather jacket and a hoop petticoat, or maribou mules and mink stole. Since launching Ruby Woo, MAC has introduced a specially tweaked version for Ruby Woo fan Rihanna, called RiRi Woo, plus a much needed Ruby Woo liner, and a matching lip gloss. The latter rather misses the point for me. This is a true red shade for strong women who love proper lipstick, not for those who can’t take the heat.

The Parlux Hairdryer

Similarly to boyfriends, I didn’t realise how needlessly rubbish 99 per cent of hairdryers were – and still are – until I found a brilliant one. For years, I thought good haircuts existed only for one day, when a professional could magically dry them into shape. After that, I was on my own with the hot, noisy, smelly hunk of plastic that woke the kids, scared the dog and left my head with the functionality of a Van de Graaff generator. In Britain, they were bad. Plugged into an American hotel wall, they were tear-inducingly awful.

And then there was Parlux. These are professional dryers available in any salon supply store for the not inconsiderable sum of around £80/$120/100 euros. They’re quite old-fashioned-looking (not in a particularly pretty way) and weigh about the same as a newborn baby in chainmail, which is why you should opt for the Compact model (already heavier than the average dryer) or the new Power Light, which have all the same features as their mother. All will style your hair in a way you previously thought impossible.

The impressively fast motor halves drying time, the three temperatures and speeds (in general, you want to start hot and fast and move down the settings during your blow dry, as a hairdresser would) give excellent shape and smoothness, and the high wattage makes a joke of your last dryer. Crucially, the Parlux has a proper cool shot setting, rather than a puny burst of tepid air offered by high street dryers. This allows you to properly set your style; leaving hair warm is like putting on a hot blouse straight from the ironing board. It’ll ruin again in seconds. The unit is sturdy too. I’ve dropped my Parlux many times, and while I’d caution against recklessness, I must commend my 11-year-old dryer’s stoicism – on and on it nobly goes. I’ve since moved on to a newer, similarly brilliant professional dryer (namely, the Hersheson) and bestowed the Parlux onto my gloriously thick-haired assistant, but only because the former is a little lighter. Age has not withered the Parlux, only weakened my right arm.

Dior Diorshow Mascara

I find natural mascaras to be rather missing the point. I don’t enhance my determinedly straight, short lashes to look like I have normal ones. I want them to be long, thick and fluttery like a Hereford cow’s. I want good separation and a brush that coats hairs, not eyelids, and a formula that doesn’t dry out in a matter of weeks. It seems so little to ask and yet is amazingly hard to find. It seems Pat McGrath, genius make-up artist, felt so similarly ill-served by the dramatic lash mascaras available that in 2001, she took a pile of toothbrushes backstage at the Dior catwalk show. The fat, dense bristles, when coated in black mascara, gave models a fanned, false lash effect that made lashes noticeable even to those sitting in the back row.

Inspired by McGrath’s ingenuity, the product development team set about designing a commercially available mascara that created the same look as the somewhat impractical toothbrushes. The result was Diorshow, a sleek, elegant silver and black tube housing a fat brush that could perhaps clean the loo in a crisis. It was an instant bestseller and in my experience is the mascara most likely to make a red carpet appearance on a starlet’s lashes. Make-up artists adore it, customers can’t get enough of it. It gives lush, dark, bovine lashes to those previously deprived, layers brilliantly, and has good staying power on most. It smudges on me, but unless you’re a serial mascara smudger, don’t let that put you off – my dry skin is so thickly basted in greasy moisturiser that it could smudge a tattoo. Diorshow now comes in an additional, waterproof formula and several permanent and seasonal colours. Which is all very nice, but my mascara motto will always be Go Black or Go Home.

Estée Lauder Double Wear Foundation

Sometimes a single beauty product is so huge, so instantly recognisable and ubiquitous, that it becomes an entire brand in its own right. Such is the case with this, the world’s bestselling foundation and the base readers most often rave about at my events. Launched in 1997, Double Wear was designed to stay on, come what may, and it certainly does that. It doesn’t transfer onto clothes and would probably survive nuclear holocaust to perfect the complexions of cockroaches and Keith Richards. Its shade range is ethnically inclusive, as is typical of American (as opposed to French) brands, its price is neither prohibitively obscene nor suspiciously low. The full coverage formula covers spots, blemishes, blotches, melasma and even faint scars but remains surprisingly comfortable to wear. It is, in my experience, what male and female popstars are most likely to wear on a hot, sweaty tour stage.

Despite my uneven skin pigmentation, Double Wear is not my own foundation of choice, because my skin is otherwise clear and to cover it so opaquely feels a little like throwing out the baby with the bathwater. Others criticise Double Wear’s ‘heavy’ and not entirely natural-looking finish, but while I take their point (with the reminder that Double Wear still looks way more realistic than any foundation launched pre-1995), I’m not personally of the opinion that make-up’s role should always be that of ‘convincing liar’ anyway. How joyless and dull. If that were the case, there’d be no red lipstick. An unthinkable tragedy indeed.

Clinique Almost Lipstick in Black Honey

In 1989 Clinique launched a new type of lip colour. Almost Lipstick was ‘not quite a lipstick, not quite a gloss, but the best of both’, and I was instantly intrigued. There were six shades in the range (Ruby Melt – the first sheer red I’d seen – was given to me by my brother David, much to my giddy joy), but the jewel in the crown was Black Honey, a blackberry stain without the jammy stickiness. Black Honey was so sheer, forgiving and thin of bullet (Almost Lipsticks came in a slender, stylo-type applicator) that it could be applied in mirrorless nightclub loos or standing on a bumpy night bus, or even while driving a car, as demonstrated by Julia Roberts, who slicks on Black Honey while behind the wheel in nineties film Stepmom. It made the wearer seem dressed up without looking try-hard. I was, and am, a huge fan myself and wore it throughout the nineties, but it looks good on literally everyone. As long as you had Black Honey in your kit, you could make any woman, regardless of age, race, hair or skin tone, look pretty great.

The rest of the shade line-up failed to make as much of an impact and so, some years later, Clinique axed Almost Lipsticks, leaving only bestseller Black Honey as a stand-alone product. I can think of few other examples of a single shade becoming so popular that it outlives its entire product line, but in this case it’s wholly deserved. Clinique rolled again and relaunched Almost Lipsticks in the early 2000s, this time capitalising on its hero-shade’s popularity by namechecking it throughout the rest of the range (Flirty Honey, Lovely Honey, Bare Honey and so on), but by now lip stains and tinted balms were ten a penny and the second-generation shades failed to take off. Almost Lipsticks were withdrawn yet again, with one inevitable exception. We’re still sweet on Black Honey.

Max Factor Creme Puff

Max Factor’s Creme Puff face powder is one of the first make-up items I was ever really aware of. As a tiny girl I would sit next to my grandmother on the bus and, as we neared our destination, watch her reach into her handbag for a gilt Stratton compact housing a pan of Creme Puff. She’d sweep the sponge over her nose and chin briskly and unfussily before clicking it shut, but just long enough for the strong, sweet baby powdery-smelling particles to become airborne and scent the whole top deck.

That Creme Puff smell, unchanged in six decades, still does strange things to me. It is one of the most instantly affecting, most nostalgic of fragrances. It smells of my nan, yes, but mostly Creme Puff just smells unapologetically of make-up (much like Dior lipstick does, or Bourjois powder rouge) at a time when make-up often smells of nothing at all. None of this sensitive skin molly-coddling, the Max Factor face powder hits you with a proper old-fashioned dressing-table smell and you’ll bloody well like it. Fortunately, I love it. And if you’ve ever hovered over your gran’s open handbag, trying to breathe in the interior’s scent, then you will too.

Creme Puff is glamorous, feminine, special. It’s not minimal, or pretending to be state of the art – it’s an old-fashioned formula that made golden age Hollywood actresses like Ava Gardner, Vivien Leigh and Jean Harlow appear flawless and luminous on set. It continues to do the job extremely well today, in its seventh decade (though sadly, its nostalgia is misplaced in its Caucasian-only shade range). Creme Puff is soft and creamy, with excellent coverage, and gives a matte finish without ever looking chalky. It contains light-reflecting particles to mimic a smoother, clearer surface. It’s perfect with retro red lips, black flicks and falsies, but also its full, layerable coverage makes it a great way to skip foundation on a more natural face – just brush over moisturiser and concealer. It’s a product I use rarely, but I would never pack a full kit without it because sometimes it’s exactly what a look needs, and the only thing that will do.

The Max Factor brand, founded by the man who literally invented the phrase ‘make-up’ (yes, really), is no longer sold in the States, where it first went on sale. I’d be very sad to see the same happen in Britain. We should cherish Creme Puff, beloved elder stateswoman of make-up and unarguably one of the most iconic beauty products of all time. I’m afraid it may be a case of use it now or lose it for ever.

Clarins Cleansing Milks

My first foray into luxury skincare came via the Clarins catalogue, supposedly free but granted only after weeks of grooming a saleswoman who knew full well the schoolchild before her could barely afford a seven-inch single. I read this (and the ‘Clinique Directory’) like one might read a car repair manual, working out which products came in which order, where they were placed, how they might work, what they might do. The relative affordability of Clarins cleansing milks (and I really do mean relative, like gold to pavé-diamond platinum) made me save up my pocket money and Saturday job wages to get a bottle of my own, but not before I’d pinched some of my big brother’s girlfriend’s and sneakily refilled it with green Boots Natural Collection body lotion (I’m so sorry, Clare). It remains one of my more shameful decisions. I can only say in defence that I was stealing to invest in my future career.

Gratifyingly, the cleansers themselves (ivory ‘With Gentian’ and green ‘With Alpine Herbs’) remain unchanged since their launch in 1966 (the brand’s first products after their plant oils and an absolutely extraordinary bust firming contraption that looks like an industrial funnel attached to a garden hose) and I applaud Clarins’s apparent belief in ‘if it ain’t broke, don’t fix it’. These cleansers really are still wonderful. They shift make-up very thoroughly when used with a hot cloth (though I tend to use them in the morning and a balm, cream or oil at night), they leave no sticky residue, only softness and comfort, and they smell blissfully cosying. The packaging has changed a little – I miss the fat, weighty glass bottles of my teenage dressing table – but the modern version maintains the simplicity of the old. The new squeezy cap does, however, prevent tampering, which in my case is probably for the best.

MAC Spice Lip Pencil

When someone sits down to write the history of the nineties, they should do so in MAC Spice lip pencil. This reddy-brown liner became the Canadian-born professional brand’s first ‘hero product’ and was the make-up accessory of the supermodel era; it graced a hundred glossy magazine covers and Linda Evangelista was never without it (I’m told she always conveniently needed to pee before shooting, then snuck on some Spice in the ladies’ loo if the make-up artist had failed to). It became the look for a generation of girls like me, who thought it the height of sophistication to wear a lip pencil five shades darker than the lips it outlined. After making a pilgrimage to buy my first Spice in Harvey Nichols (MAC’s only UK stockist at that time), and having nicked my mum’s peach CoverGirl lipstick, I debuted the look at a Salt-N-Pepa concert in Newport leisure centre. The band failed to show up but I didn’t care because I felt a million dollars.

Spice subsequently accompanied me to acid house clubs, to gigs and on capers, out on dates with inappropriate men. It accessorised Kookai hotpants, Lycra frocks from Pineapple, smiley T-shirts and red Kickers. I teamed it with fishnets, a velvet choker and beret and imagined myself in an Ellen von Unwerth shoot. I wore it with jeans and a wide headband and felt like Bardot, with a football shirt and Adidas Gazelles and thought I was Christy Turlington on the John Galliano catwalk. I was far from any of these things, but look back on Spice without a moment’s regret because, unlike so many products that completely sum up a fleeting moment in life, Spice is still a much loved, often used, part of my beauty kit. Only nowadays I wear Spice with a matching lipstick of brick red or terracotta brown, not a contrasting gloss the colour of Elastoplast.

Ardell Lashes

The age of the selfie has reintroduced so many old-fashioned beauty techniques that I’d quite happily have left in the history books with lead face powder and chastity belts, and yet I feel nothing but joy at the huge resurgence in popularity of false eyelashes. Falsies were invented in 1916 (later than one might perhaps imagine), on the set of the film Intolerance, for leading actress Seena Owen’s big close-up. The director wanted the lashes on Owen’s sad eyes to skim her cheeks, and so the film’s hairdresser threaded wig hair onto some gauze and glued it to her lashline. Reusable false lashes went into production – initially using real hair or animal fur – and became a key element in almost all iconic Hollywood beauty looks. Nowadays, lashes are synthetic and mainly come on strips, but there’s still something so brilliantly decadent and utterly mad about sticking fake hair onto eyelids with glue, something so satisfying about fluttering huge lashes more at home on Tweetie Pie. No one can be bothered every day, of course, but the occasional application of falsies is a wonderful thing when you know how – and it really is so much easier than you may fear.

First, the lashes must be cut to size (unless they’re half lashes – those designed to be worn on the outer corners only and often just the thing for a more natural look). Cutting is important because if a strip lash is even the tiniest bit too wide for your lids, then the end will hit the bridge of your nose and peel off at some point during the course of the night, and a droopy falsie is never a good look. Cut from the outside; it’s tempting to preserve maximum flutter and cut from the inside, but this will rob the fan-shape of its gradual incline, and look unnatural. Second, always, always allow the glue (preferably Duo) to become a little dry and tacky. Wet glue is too messy and makes the lash too mobile and prone to wandering maddeningly onto fingers during application. Third, apply a little black liner and black mascara to disguise any joins. That’s it.

There are hundreds of wonderful lashes on the market. I love MAC 20, Red Cherry Joan, We Are Faux Carey Red and a host of designs by Eylure, but the affordable drugstore brand Ardell makes my favourites of all – and not only because of their deliciously naff 1970s branding. Ardell’s selection of designs is vast and caters for all eye sizes and tastes: from spiky and Twiggy-like to sleepy noir-era Bacall, to sumptuous feline flutters à la Loren. They either come without glue (my preference) or with Duo (the best). The invisible bands mean they can be worn more convincingly by chemotherapy patients than many other lashes, and, on a similarly practical level, they come out of the packaging without tearing or warping, go on like a dream and the tapered shapes and soft materials ensure that, generally speaking, they look more Old Hollywood, less Spearmint Rhino.

Johnson’s Baby Lotion

Among my earliest memories is one of lying on a towel as a young toddler, fresh from the bath, toasty from the nearby coal fire, giggling hysterically as my grandmother ‘iced me like a birthday cake’ with Johnson’s Baby Lotion, squeezed direct from the bottle like a piping bag. Forty years on, it remains one of my favourite smells of all time. It’s the smell of comfort, of security, of uncomplicated and predictable times. One deep whiff is like being cosseted in a warm blanket and tucked tightly and cosily into a single bed. It’s a fragrance I always think of as smelling exactly how it looks – pink, mellow, delicate, old-fashioned, soft and sweet. It’s frankly no good on my dry skin (it works as a cleanser for light make-up at a push, and is a nice body lotion for normal skins), but I love the smell so much that I’m never without a bottle in the house. If I feel inexplicably sad or stressed out, I flip open the cap and inhale.

Clarins Beauty Flash Balm

I feel about Beauty Flash the way I feel about olives: I should like them, they’re very much my kind of thing, other people love them and I doggedly keep trying to join in, but I just can’t pull it off. This is a balm that goes over moisturiser to plump and blur lines, pep up tiredness and general haggishness, but on me – and apparently me alone – it has always peeled off in clumps as soon as I attempt to apply make-up over the top. No matter, because what is indisputable is Beauty Flash’s iconic status. This is the product, I think, that first tabled the notion of primer – a skincare/make-up hybrid to smooth and perfect the complexion in readiness for foundation. There was nothing else like it when I first tried it some twenty-six years ago, and while things may have since moved on considerably to include primers for every conceivable skin type and gripe, blur balms and light reflectors for instant de-ageing, and so on, Beauty Flash’s countless fans remain utterly devoted to the original. I almost envy them.

Guerlain Météorites Pearls

If beauty had a grande dame, an impossibly glamorous French nana, who turned up at parties in a great dress and smoked Sobranie cigarettes through a Bakelite holder, she would be Guerlain’s Météorites. These are multicoloured pastel pearls of face powder designed to be swirled together with a brush then buffed into the skin to brighten and illuminate. Launched in 1987, Météorites may have looked outwardly like an antique shop find, but was remarkably ahead of its time. For years, it was one of very few consumer powders designed to give the complexion a radiant, rather than matte, finish (the radiance trend didn’t really hit the mainstream until Revlon launched Skinlights over a decade later), and the first to introduce the concept of powder balls (or ‘pearls’), allowing several different colours or shades to be used simultaneously to give a multi-dimensional look, before technology could provide it in traditional pressed formulations. Météorites was prohibitively expensive for many, but hugely influential on the mass market. Body Shop, Boots and Avon soon made bronzer, blusher and face powder in pearls, taking them from inaccessible luxury to full-on beauty craze. Météorites remained aloof and became a beauty icon with a devoted cult following.

Nowadays, illuminating powders are ten a penny and I won’t pretend that Météorites is my own weapon of choice, but I’m not sure I’d have so many to choose from were it not for Guerlain’s trailblazing. The pearls come in a stained-panel pot not a million miles from a Tiffany lamp, which when opened, releases the delicious powdery fug of crushed Parma Violet sweets. The whole thing is bulky, breakable and wholly impractical for any manner of travel, and should be moored to some art nouveau dressing table next to a string of beads and a Dirty Martini. But Guerlain has made some concessions to modernity: there are now different colourways for more skin tones, pressed versions, travel containers and various seasonal limited editions. Each is as unfeasibly pretty as the next.

Carmex

There was a time in the late eighties/early nineties when a 79-cent pot of Carmex lip balm had as much cachet as an army surplus-store MA1 flight jacket and selvedge Levi’s – perhaps more, since it had to be scored in an American drugstore and flown home. The opaque glass jar topped with a bright yellow printed tin cap, almost entirely unchanged since its 1937 launch by cold-sore sufferer Alfred Woelbing, represented the kind of vintage Americana we Brits were already lapping up via Levi’s 501 commercials, Dax Wax and Athena airbrush prints of James Dean.

But those in the industry were ostensibly more concerned with its contents. Unlike Vaseline and Blistex, Carmex had a matte finish. It didn’t interfere with the shine-free lipsticks of the day, and didn’t cause lip pencils to lose friction and veer off-course. It was utilitarian, serious, slightly butch. All budding and actual make-up artists carried it in their kit and for many years the staple make-up look for all male models and musicians on shoots was ‘foundation, Kryolan concealer, powder, Guerlain bronzer, clear mascara, Carmex’ (I couldn’t tell you how many times I dutifully performed this routine). Off set and away from the industry, there was great snob-value in pulling a jar of Carmex from your mini backpack and so understandably, but somewhat disappointingly, Carmex saw their chance and soon the balm was available in UK pro-supply stores and fashion boutiques (including the original Space NK, which also sold juices, handbags and frocks) and later even Boots and Superdrug. It led the way for Smith’s Rosebud Salve – another nostalgically tin-packaged balm – and for Vaseline to repackage its petroleum jelly in a flat tin and rebrand it as ‘Lip Therapy’.

With the curse of accessibility and the benefit of perspective, Carmex lost its allure. Its shine-free finish is still useful, if no longer unique, but its lip-saving capabilities are bettered elsewhere. I find men still love the camphor smell, non-greasy feel and ungirlie packaging, which occasionally gets a limited edition makeover (the recent Peanuts/Snoopy and superheroes collaborations were a well-conceived delight). I rarely use it now, but always keep a pot in my kit to remind me of exciting times and endless possibilities, and for the occasional mentholated whiff of an industry that was to change my life for ever.

Nars Orgasm Blusher

One can almost chart British society’s increasing liberality through the growing confidence with which the average woman asks a Nars sales assistant for an Orgasm. As recently as 2010, the inclusion of this powder blusher in my Guardian Weekend beauty column prompted one reader to accuse me of wilfully setting up the women of Britain for humiliation. All I could say is that it’s worth a moment’s shame, because Nars Orgasm is a must. I can think of few other colour cosmetics – least of all, complexion products – that genuinely look pretty on every skin tone, from white to olive to brown to black. The clue is in the name. This is a blusher designed to mimic the flush of colour to the cheeks at sexual climax or, in less florid language, it makes you look just-shagged. A smart and attention-grabbing way to market a product, for sure. Orgasm launched in 1999 and its name certainly helped it get plenty of publicity and celebrity endorsement (Jennifer Lopez, at the height of her fame, was rarely seen without it), but it’s still absolutely true that just like a climactic rush of blood to the face, Nars Orgasm makes almost everyone look better.

The secret is Orgasm’s perfectly balanced mix of peach and pink pigments that both brightens pale or sallow complexions and neutralises rosy ones, and teams with red and pink lipstick as well as it matches apricots and peach. A subtle, shimmery gold fleck stops it ever looking ashy or chalky on dark skins. This universal quality is what makes Orgasm not only Nars’s biggest seller (120 are sold every hour of the day), but also the matriarch of an entire franchise including spin-offs like Super Orgasm (a hyper-glittery version of the original), the Multiple Orgasm (a stick creme blush and an open goal for the product namers, let’s face it), a nail polish, lip gloss and illuminator. But none is as indispensable as the original. I’d only discourage its use on those whose cheeks are scarred or bumpy, as Orgasm’s slight shimmer will do them no favours. But I’d urge those same women to simply choose another (ideally matte) shade from Nars’s range, perhaps Sex Appeal or Zen. Because while it’s impossible to describe any brand as the best at everything, I have no hesitation in declaring Nars the very best at blush.

Clinique 3-Step

Clinique is my first love, and alongside a hereditary skin condition that saw me in and out of dermatologists’ offices throughout my childhood, sparked my enduring passion for skincare. Like every woman I know, I still have many of Clinique’s products on my bathroom shelf and dressing table (you will need to prise Bottom Lash Mascara, Take The Day Off Cleansing Oil and Superbalm from my cold dead hands), and yet I haven’t used its iconic and revolutionary 3-Step skincare system for decades. But I still give it huge credit and reverence, because much like a teenage boyfriend who introduced me to great music and nightlife, but ultimately wasn’t for me, 3-Step represents a moment of awakening and explosion in my curiosity and knowledge.

The three-part regime, developed by respected dermatologist Dr Norman Orentreich and Estée Lauder executive Carol Phillips in 1968 (and barely changed since, the addition of a little hydrating hyaluronic acid aside), comprises a facial soap, four numbered salicylic acid liquid exfoliators of increasing strength (at time of writing, a new alcohol-free version is in the pipeline), and a pale yellow moisturiser for all skin types. Fragrance-free and allergy tested – unheard of in those days – it introduced the concept of exfoliation (the removal of dead skin cells to reveal brighter, newer, smoother skin beneath) to the masses, was the first nationally available dermatologist’s range (others were sold locally, in anonymous medication bottles direct from doctors’ offices), and, as such, revolutionised the entire cosmetics industry. Customers were given an on-counter analysis using a ‘computer’ (and when I say computer, I mean something that nowadays has more in common with an abacus), and prescribed the specific soap and clarifying lotion for their needs.

In 3-Step, Clinique also introduced the concept of functional, rather than needlessly fancy, premium skincare for the masses, and its packaging – pared down, clean, stylish and minimal – was photographed by the great still life photographer Irving Penn in a series of iconic advertisements without model or figurehead, cleverly appealing to all women, regardless of age, colour or skin type. The products, dressed only with a toothbrush, were sold as the new basics: the white T-shirt and jeans of every woman’s skincare wardrobe, onto which all other lotions or potions were to be layered. This core message – three simple products and three quick steps for better skin – proved enormously successful and endures to this day, and provided the basis for an entire brand of simple, effective, problem-solving cosmetics upon which so many of us still rely.

And yet despite the fact that it remains the world’s bestselling skincare routine, 3-Step can still be described as a cult. Women (and men – the Clinique For Men range differs only in packaging) who love 3-Step, really love it, and will countenance no other regime. And I certainly won’t argue – I’ve seen tremendous results on skin of all ages. Personally, I simply cannot get on board with facial soap in any guise; there are liquid exfoliants I prefer (though they might not exist if it weren’t for Clinique’s groundbreaking Clarifying Lotion), and the mighty Dramatically Different Moisturizing Lotion isn’t mighty enough for my naturally drier-than-sawdust face. But none of this matters. It works for millions, it may work for you, and no one can begin to deny that it permanently changed how most of us see skincare. Clinique 3-Step changed the world, and respect is very much due.

Weleda Skin Food

I can never lay claim to being a great lover of natural skincare. Ethics are certainly important, and I am all for paraben-free if that’s important to you (the evidence against them is woolly at best, and most of us eat parabens every day, so I’m sceptical, to say the least). I’m certainly a lover of many essential oils and balm cleansers, I choose organic milk to pour in my tea, boil organic eggs for my breakfast, but when it comes to skincare, my priorities are efficacy and results – and in my view, those usually come from a combination of the best of both science and nature, not from homeopathy for its own sake.

Skin Food, by Swiss-German health shop beauty brand Weleda, is a notable exception. It’s a rich, unctuous and affordable balm made from 100 per cent natural ingredients like almond oil, beeswax, calendula, rosemary, pansy and chamomile, for the purpose of moisturising dry faces and bodies. There’s something so lovely about its slightly medicinal metal tube and 1970s earth mother green design. But the product, sold at a rate of one every thirty seconds, is the real star here. Used by Victoria Beckham, Alexa Chung, Julia Roberts, Winona Ryder, Adele, a million models, make-up artists and, erm, me to baste my face like a turkey on long-haul flights, Skin Food acts as the name suggests: it’s exactly what to reach for when your skin feels peckish for something lovely, and leaves face and body snug, cosseted and comfy. I adore its gorgeous botanical smell, its reasonable price point, its assured place next to mung beans and nut bars in health food stores, its integrity and modesty. But most of all, I love that Skin Food has steadfastly stuck to its guns through every imaginable beauty trend and, almost a hundred advertising-free years after launching, is as relevant and more widely loved than ever, like some kindly great-grandmother who always quietly knew best.

YSL Touche Éclat

Touche Éclat is arguably the most iconic make-up item of all time. The evidence can be seen everywhere: make-up artists referring to a ‘touche éclat look’ (as one might use the term ‘Hoover’ for vacuum cleaner) when they actually just mean the artificial adding of brightness; men raiding their wives’ make-up bags for an instant pick-me-up; women who own no other make-up keeping a regular stock to perk up sleepless eyes; a thousand copycat products; sales figures so vast that this one gold tube is a brand all on its own. But oh, Touche Éclat, our own relationship is complicated. I first discovered this elegant gold clicky pen of salmon-pink cream in the early nineties, when it had secured its place in every make-up artist’s kit I invariably poked my nose into. The buzz escalated outside the professional world, partly thanks to the explosion of celebrity culture and countless ‘What’s in my make-up bag’ interviews with A–Z list actresses and popstars, all wildly singing its praises. Somewhere in this process, Touche Éclat became known as a concealer, and this, for me, is where my issues began.

Touche Éclat is not a concealer. It is a brightening corrector, and one launched way before any other mainstream brands had considered their usefulness (nowadays, correctors are everywhere). On white skin, its sheer pinky hue helps cancel out grey tones commonly found under the eyes, and highlights cheekbones to make them pop. It does not cover spots, blemishes, patches of sun damage or much else for that matter, and to misappropriate it is often to make things much worse. When flicking through a wedding photo album on Facebook, I can invariably spot Touche Éclat before I’ve even had time to digest the frock. When worn in abundance as a generic cover-all, with no proper concealer over the top, it creates the impression of a fortnight spent skiing in goggles in Val d’Isère. On dark skins, the original shade (called Radiant Touch, it has now rightly been joined by several brand extensions, including more skin tones, colour correctors for different uses, and a very good light-reflecting foundation) looked sickly and unnatural.

Its woeful misuse was and is a terrible shame, because when used judiciously and sparingly as an undercoat for concealer or as a straightforward highlighter, Touche Éclat is actually rather wonderful. Its revolutionary click pen packaging makes it very convenient for making up on the move (you’ll need to wash the brush regularly, of course), its thin formula blends beautifully, and its sparkle-free light reflection is perfect on brow bones to sharpen their appearance. On cheekbones, or applied lightly across the centre of the face in a cat’s whiskers formation (then blended, of course), it can bathe skin in gloriously flattering light.

Sadly, my appreciation for Touche Éclat came way too late in the day. I am horribly allergic (and I say this as someone who, after a lifetime of product testing, has skin as hardy as Shane MacGowan’s liver), and so I cannot finally make amends for my former harshness. I use Bobbi Brown or Becca corrector on my own dark circles. But to the vast majority of women who can click, sweep and blend Touche Éclat with no adverse effects, all I can say is that I finally see where you’re coming from.

Avon Skin So Soft

I do so love a product with a sneaky sideline in something for which it was never designed. KY Jelly as a hair styler on short retro haircuts, non-oily eye make-up remover on stubborn carpet and soft furnishing stains, and clear nail polish on freshly laddered tights are just a few hugely satisfying deployments of products entirely fit for multiple purpose. Perhaps the most polymathic product of all is this, a cheap-as-chips fragrant body moisturising spray, reportedly used for decades by the US Navy as a standard-issue mosquito spray for soldiers stationed abroad. Meanwhile, on Civvy Street, Skin So Soft’s vast legion of fans (40 million bottles have been sold since its 1961 launch, and Avon representatives stockpile it at the beginning of every summer) claim the dry-oil spray makes an excellent remover for candlewax, chewing gum and paint. Artists and decorators use it to clean brushes, housekeepers swear by it to remove carpet stains, and Hollywood film crews douse themselves in large quantities before entering an insect-ridden shooting location. Even the royal household is rumoured to use it for purposes on which we can only speculate.

What we can be sure of is that Skin So Soft is a hidden gem of a product, and that to have this somewhat dated and naff-looking bottle (more like something kept under the sink than in the bathroom cabinet) handy at all times is to be in on an immensely satisfying secret. So wide is Skin So Soft’s skill set that it’s easy to forget that it delivers admirably on its original brief. It has a light, pleasant smell, a non-greasy texture, and leaves limbs softened and more evenly toned. And mercifully abhorrent to mozzies.

Elizabeth Arden Eight Hour Cream

I admire beauty brands with a sort of benign arrogance about their star products, a self-belief so strong that to tweak, reformulate or move with the times would be an unthinkable admission that any improvement on the original is even possible. This is why I so admire Elizabeth Arden’s Eight Hour Cream, a thick, glossy, greasy preparation invented in the 1930s by Miss Arden herself and used ever since on the burns, cuts, windburn, chapping, grazes, dry lips, ragged cuticles and unruly brows of humans, and on the aching legs of thoroughbred horses (yes, really – Miss Arden always kept jars in her stable and it caught on. I suppose if you’re dropping half a million on an animal, then twenty quid on some luxury hoof ointment is mere loose change).

But modern beauty fans will know 8-Hour less as a medicinal balm, more as a multi-purpose gloss quite unlike the rest. While other paraffin-based products like Vaseline become thin and slide gradually off the skin or into the eyes, 8-Hour remains thick, holds its gel-like structure well and tends to stay firmly (and stickily) on the job. This makes it peerless in changing the consistency and finish of all manner of traditional cosmetics. Make-up artists mix it with powder shadows to create eye gloss, with kohl to make brow wax, with lipstick for a sheer lip gloss or gleaming flush of cheek colour. But this is no industry secret. It’s by far Elizabeth Arden’s most successful product, with a tube of the original formula (as opposed to its many spin-offs) selling every thirty seconds worldwide. Millions of women, including Victoria Beckham, Penélope Cruz, Emma Watson and Kate Moss, use 8-Hour neat to add a flattering sheen to cheekbones and lips, softening the skin and adding a very subtle pinky-peach tint. I see 8-Hour primarily as cosmetic, but I don’t quibble with its skincare benefits in certain applications – the mild beta hydroxy acids slough dead skin flakes, particularly on the mouth and nose – while the vitamin E and paraffin provide temporary moisture and relief.

Those who love 8-Hour seem never to be without a tube in their handbag, ready for emergency deployment, and will suggest its use in seemingly any skin crisis or extreme weather condition. It provides an almost unmovable barrier of emollient and for this reason, many women even swear by 8-Hour for basting the face in readiness for long-haul flights, though some of us really wish they wouldn’t; the smell is a pungent and not universally pleasing combination of roses, lanolin, a nana’s handbag and Germolene. The relatively new unscented version – though by no means odourless – is a tad more sociable, if a little inauthentic.

Lush Bath Bombs

To the young or disinterested, bath bombs must have just appeared from nowhere, piled high in Lush shop windows, their distinctive and sometimes obnoxious smell polluting the air for fifty yards. But for me, bath bombs will always be a reminder of Cosmetics-to-Go, Lush’s innovative forerunner in Poole, Dorset. This was the first incarnation of Lush, founded in 1987 by husband and wife Mo and Mark Constantine and beauty therapist Liz Weir, selling natural, British-made and faintly bonkers products like solid shampoo bars, fresh fruit-enzyme face masks hand blended on the premises like smoothies, peanut butter face scrubs that were literally good enough to eat, and Second World War-inspired liquid stockings in glass bottles that looked like Camp Coffee. Like the Body Shop’s errant, less neurotic little sister (the Constantines had invented many products for Anita Roddick’s fledgling empire, including its bestselling Cocoa Butter Hand & Body Lotion), Cosmetics-to-Go was the first time I’d seen beauty with both a sense of humour and a strong sense of purpose.

A cruelty-free stance was at the heart of the brand, without it becoming so worthy and earnest as to be dull. Quite the contrary: I looked forward to new Cosmetics-to-Go catalogues like new issues of Just Seventeen, and pored over the quirky illustrations and chatty copy. I’d then ring the order line whenever I had a spare couple of quid, and two days later, a brown paper-wrapped box covered in primary-coloured labels would arrive, crammed with truly groundbreaking and extraordinarily packaged products. Eyeshadows in faux-marble wedges, popped in a Camembert box to create a bespoke palette not a million miles from a Trivial Pursuit wheel, a men’s grooming range festooned in chintzy florals when everyone else was flogging aftershaves got up to look like car parts, and a blackberry-scented bath powder moulded to look like the kind of Acme bomb beloved of Wile E. Coyote. This was the first ‘bath bomb’ – a fizzing mix of fragrance, essential oils, moisturising butters, citric acid and bicarbonate of soda, directly inspired by the uplifting, soothing qualities of Alka-Seltzer. Its relative cheapness and versatility spawned a whole range of bombs in multiple shapes, colours and scents, and an entirely new product category was born.

Ultimately, Cosmetics-to-Go had too many brilliant and impractical ideas, too little business acumen. Even as a child, I wondered how they could possibly be making enough money when, as a matter of course, they’d mistakenly send me free duplicates of practically every order I placed. They weren’t, as it turned out. Cosmetics-to-Go went down the plughole in 1994, but their bath bombs stayed afloat, providing the old CTG team with a basis for new venture Lush, now a hugely successful British high street retailer based on the same environment/employee/animal-friendly principles as before. Lush still makes dozens of different bath bombs (selling well over 26 million of them to date), all copied endlessly by rivals, often with much less care for quality and ethics. Even when the real thing enters my house via press sample, kid’s birthday gift or party bag, my heart sinks in anticipation of post-bath scrubbing to remove some glittery lurid puce tidemark. But I always give in to the pleas and chuck one in because I want my kids to see that modern beauty products aren’t only for making someone’s nose look skinny on Instagram. They can also be fun, kitsch, bonkers and kind. No one demonstrates that better than Lush. Long may they fizz.

Kent Combs

Any company awarded a Royal Warrant – a recognition of excellence for selected small firms that supply the royal households – must be doing something right. A firm granted Royal Warrants by nine successive sovereigns, though, can claim quite persuasively to be doing pretty much everything better than anyone else. Founded in 1777, the brush-making concern G.B. Kent & Sons was awarded its first warrant by George III and has received royal thumbs-up from every king and queen since. Kent, the UK’s longest established brush-maker, is a heart-swelling example of a firm peopled by artisans, preserving specialist skills in the face of mass production and foreign imports.

Kent allies British pluck and ingenuity – the Second World War saw the firm produce a shaving brush with a secret compartment for map and compass to facilitate the escape of prisoners of war – with meticulous production methods to produce doughty, tactile artefacts of enduring loveliness. Its saw-cut combs are polished and buffed by hand, the teeth free of the tiny, snaggy ridges found in injection-moulded combs. The women’s tail comb – a seventies classic that sells a pleasingly un-mass-market forty a day – is a sleek, frictionless delight that makes you want to keep on combing, mermaid-like, long after the practical necessity has gone. I like to imagine Princess Anne using one to tease her crown before sweeping everything into a no-nonsense riding bun, or Charles reaching for his Kent brush in the hope of making his remaining strands go further.

If sharing a brush supplier with the Queen doesn’t float your royal yacht – and I do understand – focus instead on the preciousness of British-made beauty tools, made with love, pride and devotion to the craft, and sold widely at a very reasonable and accessible price point (my paternal grandfather always carried a tortoiseshell Kent – and he was a lowly stable lad). Kent is a company I wish to exist for ever. We should never assume that’s a given, and perhaps replace our old combs forthwith.

Shu Uemura Eyelash Curler

In the eyes of critics, perhaps no product better sums up the madness of beauty than the eyelash curler. Here is a prohibitively dangerous-looking piece of metal that resembles something a Victorian dentist might use to winch out a rotting molar, used for the sole purpose of lifting and curving one’s eyelashes temporarily. It does seem slightly bonkers, on reflection. And yet, with the right curler, it really is a uniquely gratifying twenty-second job.

The Shu Uemura eyelash curler is such a reference point for all other beauty tools, that it’s easy to forget that it only launched in 1991. When Japanese make-up artist Shu Uemura launched his groundbreaking eponymous brand, there were few luxury lash curlers on the market and he felt all of them failed to sufficiently and comfortably curl short lashes. And so he briefed his son Hiroshi Uemura to create one that did. Hiroshi worked with professional make-up artists to test different widths, lengths, gradient curves, rubber elasticity and pressure intensity until he had what the professionals still believe to be the eyelash curler against which all others should be measured. And while to the untrained eye it may look the same as a three quid version in Boots, they are apples and oranges. The Shu Uemuras don’t pinch or bend lashes in an unflattering right angle. They can be used both under and over mascara (this is always my preference – you get a better hold) without damage and even on short, pin-straight lashes like mine they give great and lasting curve. The mechanism is loose enough to allow partial release of tension, but can be tightened in case it becomes slack.

At time of writing, Shu Uemura’s eyelash curler has won a major beauty award for fifteen consecutive years and in all that time I don’t think I’ve met a single make-up artist who doesn’t own at least one set. The curler has appeared on magazine covers (Kylie Minogue’s iconic 1991 shoot for The Face), in films (The Devil Wears Prada, where it’s namechecked) and in pop videos (Annie Lennox’s wonderful ‘Why’ promo, featuring the extraordinary make-up skills of the great Martin Pretorius – a must-see for any beauty nerd), and been honoured with several limited editions, including a twenty-four-carat gold version. Shu Uemura’s eyelash curler is a beauty icon because, quite simply, it’s the best.

Bourjois Little Round Pots

There are few products more cheering than a little fat pot of Bourjois blush or eyeshadow, nor as instantly recognisable. None of us has lived in a time where these multicoloured pastel powders didn’t line high street chemist racks like freshly baked macarons in a patisserie window. These are domed, single shadows and blushers in sheer, muted tones including matriarch Cendre de Rose, an old Hollywood rouge, the deep, black-red hue of crushed rose petals, released in 1881, and Rose Thé, a dusky nude-pink blush born in 1936. For over 150 years, these traditional powders have provided the basis for the entire Bourjois brand, however cutting edge the rest of its offering has become.

The Fard Pastel powders – now known as Pastel Joues – are baked (much like Chanel’s European market shadows; for years, rumours abounded that they were made in the same factory) and so colour payoff is not as dramatic as with a modern, pressed pigment powder, but the finish is soft and blendable, and the colours are gentle, pretty washes that are hard to get wrong. Their rose scent is blissful, reminiscent of the dusty, flowery interior of a great-granny’s hanky drawer, and among my all-time favourite beauty smells.

The Little Round Pot franchise has been expanded over the years to include creme blushers that are among the very best at any price, and the packaging updated from rococo cherub design cardboard to chintzy floral tin, to gold-stamped coloured Bakelite (the packaging I grew up with), and the more convenient mirrored snap-compact we see today. But what has remained throughout is the chubby, tactile shape and moreish shade line-up that make Bourjois Little Round Pots the kind of rainy lunchtime purchase that can keep a girl going until clock-out.

Evian Brumisateur

I must give props to Evian for somehow making a beauty icon of an almost laughably unnecessary product, but then the entire bottled water industry is based on turning a relatively free resource into a marketable commodity, so I guess popping water into an aerosol in the name of beauty was a fairly short leap for them to make. Yes, I am deeply cynical but yes, I am also no more immune to the hype than the next person. There was a time in my life when an Evian Brumisateur was all my heart desired. Magazines of the 1980s were always singing its praises, and if you were the kind of person who hoovered up every interview with make-up artists and beauty editors, you soon realised that this large can of water was in every industry kitbag.

Why? It’s a good question. The assertion by beauty professionals was that it ‘set’ make-up in place, though I’ve never personally found any evidence that this could be true, even over old-fashioned make-up formulas. It was also used to ‘freshen’ skin at the start of photo shoots, which is valid, if one has no access to a tap and an empty spray bottle, which admittedly were not as commonly available, and much less fine in the eighties (gardening sprays were more of a shower than a spritz). Where I can see the use for a Brumisateur is if you are working in some remote location, where cold water is scarce (the tin can tends to keep the water cooler), or if you are easily overheated – like in menopause – and you want something cooling and chemical-free in your handbag that won’t potentially cause any irritation.

In any case, Evian Brumisateur was successful in making itself a hugely desirable product, and in securing its place in every beauty junkie’s arsenal. I associate its packaging with the cluttered make-up table on countless photo shoots and filming sets and absolutely will concede that it launched an entire beauty category of facial spritzers, now a feature in most skincare brands with the addition of plant extracts, hyaluronic acid, glycerin and so on. I’ve also no doubt the dubious myth that a final spray of water locks make-up in place went on to inspire the development of true make-up fixing sprays like those by Urban Decay, MAC, NYX, Clarins and many others. But mostly I still see Evian’s original as little more than a status symbol born in an era obsessed with acquiring them. As with our obsession with buying wasteful plastic bottles of water in safe and plentiful supply from our own kitchen taps, I often think that future generations will look at Evian Brumisateur and wonder if ours had temporarily taken leave of its senses.

Benefit Benetint

Much like prawns, gin and bracelets, Benefit Benetint is something that looks so completely up my street, and yet, however persistently I try, I just can’t get onboard. My skin is too dry and too thirsty for this liquid rose-petal lip and cheek stain and so it sinks in well before I can blend it, and there it remains, like a clumsy Malbec spill on a white shag pile. On normals and oilies, Benetint is beautiful – but this isn’t the only reason I’m able to love it. Sometimes one quirky, interesting product can create enough mystique and ecstatic word of mouth, that it alone has the power to launch an empire – and never has that been more pleasingly demonstrated than here.

In 1977 an exotic dancer entered the tiny San Francisco beauty boutique of twins Jean and Jane Ford, and asked for something to stain her nipples (I do so enjoy hearing of a beauty gripe even I’d never considered), making them bright, perky and noticeable throughout a long show on a dark stage. The sisters took up the gauntlet and began experimenting in their kitchen, steaming real rose petals to create a deep, vivid red liquor to stain the skin. The liquid was poured in a tiny cork-stoppered glass bottle, hand-labelled with a naive line drawing of a single bloom, named ‘Rose Tint’ and delivered to the dancer. Needless to say, it was enthusiastically received, applied more widely than on the nips, and soon dozens of San Franciscan women wanted in.

Gradually, Benefit took off, arriving in the UK in the late nineties, where just a tiny handful of products were sold at Harrods. The press were captivated, the buzz about the by then repackaged and renamed Benetint in particular was huge. Now, Benefit is one of Britain’s top five bestselling colour brands. Some of their products are superb: they are particularly good at brows, bronzers and highlighters, but that original nipple tint remains its hero. When brushed onto the right skin and rubbed in with fingertips, it adds a pretty, effortless rose flush straight out of a Pre-Raphaelite watercolour that, sadly, I can only admire second-hand.

Mason Pearson Hairbrushes

I don’t know if you’ve ever sat in a hairdresser’s salon and witnessed your stylist find themselves temporarily unable to locate his or her Mason Pearson hairbrush, but I have on several occasions and can assure you it’s not pretty. Woe betide any chancer who attempted to make off with it. This is because a Mason Pearson rubber cushion brush remains, over 200 years after its original invention, the gold standard throughout the hairdressing world, with each owner feeling as attached to theirs as a chef to her favourite paring knife. I feel similarly about my own cherished brushes.

I encountered my first Mason Pearson at around six years old, when my aunt came to stay from London with a girlfriend who unpacked a large Mason Pearson and placed it ceremoniously on my tiny dressing table next to her Z-bed. Before then, I’d thought that hairbrushes were two quid jobs from the corner shop or chemist and associated them with tortuous and tear-filled detangling sessions in front of the fire – so fraught that my father once felt a yellow plastic handle, defeated by a knot as unyielding as a boulder, snap clean in half in my hair and sort of dangle, like Fay Wray in King Kong’s clutches. The Mason Pearson was different. Like the Mary Poppins of hairbrushes, it was firm, sturdy and no-nonsense but kind, modest and uncommonly elegant. Sadly, there was no way a family like ours could ever spend a week’s grocery money on a hairbrush, and so I had to wait until adulthood, when I was earning my own money and found myself in a traditional chemist in Mayfair ostensibly looking for Nurofen. That same 19-year-old ‘Handy’ sized Mason Pearson is still on my dressing table today, nobly doing its job, while an 8-year-old ‘Pocket’ size lives permanently in my handbag.

It’s endlessly satisfying to me that in an age of ceramic-barrelled, laser-cut, heated and rotating contraptions, this high-quality British-made icon prevails. Anyone who’s ever owned a Mason Pearson will know why. The weighty plastic handle (or a wooden one if you’re a purist – they’re still available on some models) feels smooth and solid in the hand, the bristles (natural bristle for fine hair, a bristle and nylon mix for normal hair, nylon bristles for thick and curly hair) glide through locks like a spoon through cream, gently massaging the scalp to dislodge dirt and distribute natural oils down the shaft, thus eliminating frizz. It backcombs brilliantly, neither scratches nor pulls, tames hair without causing static, and dries fringes or bangs better than anything (just pull the brush back and forth across your forehead while the dryer nozzle points downward). The Mason Pearson can also be used on children’s hair (I invariably buy the child’s size as christening gifts) without them wailing from bath to bedtime. The brush itself is extremely easy – and satisfying – to clean with a sturdy wide-toothed comb.

Of course, any Mason Pearson owner would be lying if they claimed not to have been drawn, at least in part, to its heirloom-worthy looks. The signature gold-blocked ‘Dark Ruby’ (black on first glance, a gemstone red when held up to the light) handle and orange rubber cushion make it utilitarian but elegant, and recognisable the world over. And despite the incomparability of the Mason Pearson, so many are still trying to copy it, even marking up the already painful price point. It’s wholly unseemly and I reject them utterly.

Clairol Herbal Essences

Let’s be perfectly honest, there’s nothing exceptional or special about Herbal Essences shampoo and conditioner. They smell rather lovely, they do the job perfectly well, they come at a great price point, can be bought anywhere and their name sounds pleasingly like a reggae compilation album circa 1973. What makes them iconic is a single marketing campaign, conceived as a do-or-die last-chance saloon for a tired-looking haircare franchise at Clairol, at a time when Herbal Essences was a generic family haircare brand with no USP to speak of. By the late 1990s, beauty brands using natural plant extracts were a dime to a dozen, many of them doing it more thoroughly and more authentically. Herbal Essences had always been marketed at everyone, and thereby appealed to no one.

Ad execs decided to give the brand a boot up the backside with a campaign zoning in on women rather than the entire family. Borrowing heavily from Nora Ephron’s When Harry Met Sally, the groundbreaking new campaign featured women, standing alone in the shower, loudly climaxing as they lathered up with Herbal Essences shampoo, suggesting that this run-of-the-mill brand was far from an unremarkable, stuffy seventies relic, but a ‘totally orgasmic’ experience. The ads were pretty tame – cheeky rather than softly pornographic – but for a generation of women who’d grown up in token sex education classes without ever hearing mention of the female orgasm, they represented a sea-change in middle-of-the-road beauty advertising and marketing. Herbal Essences was no longer about the dutiful housewife leaning over the bath to wash her children’s hair while a chicken roasted in the oven, it was a brand for women and recognised their need for ‘me time’ (I promise I will never use this mortifying expression again). Of course, the campaign rather overstated the product’s effects – unless a woman was to be more imaginative with the water hose, a shower with Herbal Essences was unlikely to yield greater results than cleaner hair. And it’s true that after we became inured to the original gimmick, and other brands pushed the envelope further, Clairol was back to square one. We now lived in a world where reality TV stars had sex on telly and defecated in front of six hidden cameras.

In the mid-noughties, P&G, having acquired Clairol, redesigned and relaunched Herbal Essences, scrapping the pastel bottles and Totally Orgasmic Experience in favour of lurid brights and a red carpet-wannabe message. These effects were also short-lived. A few years later, P&G rightly went back to the old, by now iconic bottles and smells. Where that leaves Herbal Essences is anyone’s guess. Where it perhaps leaves women is with little more than sexual frustration and a pleasant, vaguely chemical herbal scent.

Old Spice

Old Spice Original, launched in 1938, is the smell from the backseat of my grandad’s brown Austin Allegro as he drove me to Little Chef for the giddy treat of jumbo cod, chips, banana split and a free lollipop for clearing my plate. Its warm, not-too-strong but lasting spiciness is the smell of day trips to Tenby, of candy-stripe brushed flannel sheets from the market, of a tiny metalwork room made from a cubby-hole under the stairs. It’s the smell of the armchair where we took Sunday naps during the rugby, had cuddles and belly laughs in front of Victoria Wood’s As Seen On TV, where my grandad sat patiently as I stood on a stool behind him, tying bows, plaits, jewels and fancy clips in his white hair, not giving a damn if he had to answer the door for the postman.

Old Spice is the scent of him trying to teach me long division when everyone else had long ago lost patience, of very gentle flirting with the checkout ladies at Kwiksave, of seemingly endless chats with every Indian and Pakistani immigrant in Blackwood to practise his beloved Urdu and Burmese learned during the Second World War in Burma. It’s the smell that filled a silent room whenever I asked what had happened to his friends there. Old Spice is the smell of his old shirt worn over my ra-ra dress to wash the car, of well-thumbed Robert Ludlum novels, of huge cotton handkerchiefs, of an often empty wallet, of the green zip-up anorak bought via twenty weekly payments from the Peter Craig catalogue. Old Spice was there when J.R. Ewing was shot, when I first saw Madonna on Top of the Pops, when the miners went back to work and when we sat under blankets at military tattoos, both of us weeping like newborns. Its absence was felt acutely when I last saw his face, eyes closed in the room of a hospice; when I got married and when my babies were born.

Clearly, I’m too sentimental about Old Spice for my opinion to be truly objective, but unlike so many other scents of my youth, I believe Old Spice Original (not its newer, nastier incarnations) is still a gorgeous fragrance in its own right. It’s neither ironic nor retro, just a wholly pleasant blend of nutmeg, cinnamon, clove, star anise, exotic jasmine, warm vanilla and sweet geranium, packaged in one of the most beautiful perfume bottles of all time. For the world’s bestselling mass-market fragrance, and an indisputable beauty and grooming icon, Old Spice Original still feels like a very unique and personal affair. I revere it for many reasons, but not least because, as its early ad campaign asserted, ‘You probably wouldn’t be here if your grandfather hadn’t worn Old Spice’.

OPI I’m Not Really A Waitress

I give huge credit to OPI for creating a polish that in many ways has become as standard a red as that of London buses, award season carpets, Welsh Guards, the stripes on American flags and the coats on Chelsea Pensioners. It is consistently at number one across OPI’s shades and, cumulatively, is officially the brand’s bestselling lacquer of all time. For a polish launched as late as 1999, I’m Not Really a Waitress has certainly got around. Apart from being the go-to red for TV and film make-up artists who love its dense, multi-dimensional finish (it shows up really well on camera without stealing the scene), I’m Not Really a Waitress has featured as the $16,000 question on the US version of Who Wants to Be a Millionaire, been used as the colour reference point for a red Dell laptop and has won the Reader’s Choice Favourite Nail Colour Award in Allure magazine a staggering nine years on the skip. The seal on its iconic status: the Urban Dictionary even recognises I’m Not Really a Waitress as ‘The specific color of red nail polish that is used in countless movies and commercials for its sheer mass appeal’.

I agree that the key to its success is that I’m Not Really a Waitress truly looks good on everyone, and with everything. It’s a ruby slippers red that flatters black, brown, yellow, pink and white skins equally, and layers very well for greater depth. It looks expensive and neat, leaving nails like the bonnet of a metallic red Porsche. The sparkling – but not glittery – finish makes it glamorous enough for parties (it’s my default Christmas polish – so festive and jolly) but restrained enough for work meetings. The unforgettable if slightly annoying name also helps. Launched originally for OPI’s Hollywood Collection, the name – typical of the brand’s quirky wordplay – is a homage to wannabe movie stars making rent by waiting tables while they wait for their big break. And so it’s fitting, really, that I’m Not Really a Waitress has ended up making so many uncredited appearances in big Hollywood blockbusters.

Pantene Shampoo