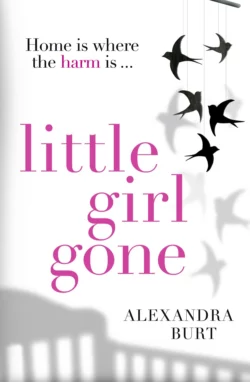

Little Girl Gone: The can’t-put-it-down psychological thriller

Alexandra Burt

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Современная зарубежная литература

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 152.29 ₽

Статус: В продаже

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: **Read the must-have Sunday Times bestseller today. GONE GIRL meets THE GIRL ON THE TRAIN in this stunning, unsettling psychological thriller.**A baby goes missing. But does her mother want her back?When Estelle’s baby daughter is taken from her cot, she doesn’t report her missing. Days later, Estelle is found in a wrecked car, with a wound to her head and no memory.Estelle knows she holds the key to what happened that night – but what she doesn’t know is whether she was responsible…