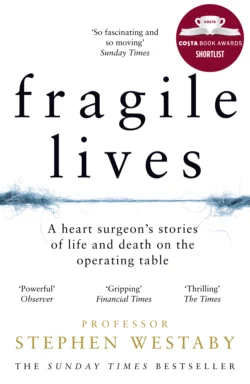

Fragile Lives: A Heart Surgeon’s Stories of Life and Death on the Operating Table

Stephen Westaby

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Социология

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 463.26 ₽

Статус: В продаже

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: SHORTLISTED FOR THE COSTA BIOGRAPHY PRIZETHE SUNDAY TIMES NO.2 BESTSELLERWINNER OF THE BMA PRESIDENT’S AWARD 2017An incredible memoir from one of the world’s most eminent heart surgeons, recalling some of the most remarkable and poignant cases he’s worked on.Grim Reaper sits on the heart surgeon’s shoulder. A slip of the hand and life ebbs away.The balance between life and death is so delicate, and the heart surgeon walks that rope between the two. In the operating room there is no time for doubt. It is flesh, blood, rib-retractors and pumping the vital organ with your bare hand to squeeze the life back into it. An off-day can have dire consequences – this job has a steep learning curve, and the cost is measured in human life. Cardiac surgery is not for the faint of heart.Professor Stephen Westaby took chances and pushed the boundaries of heart surgery. He saved hundreds of lives over the course of a thirty-five year career and now, in his astounding memoir, Westaby details some of his most remarkable and poignant cases – such as the baby who had suffered multiple heart attacks by six months old, a woman who lived the nightmare of locked-in syndrome, and a man whose life was powered by a battery for eight years.A powerful, important and incredibly moving book, Fragile Lives offers an exceptional insight into the exhilarating and sometimes tragic world of heart surgery, and how it feels to hold someone’s life in your hands.