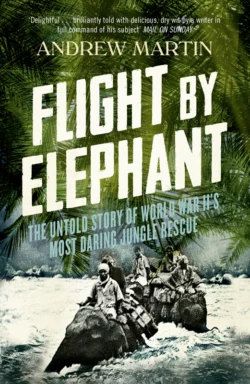

Flight By Elephant: The Untold Story of World War II’s Most Daring Jungle Rescue

Andrew Martin

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Биографии и мемуары

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 234.27 ₽

Статус: В продаже

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: In the summer of 1942, Gyles Mackrell, together with twenty elephants, and a team of mahouts (elephant riders) performed heroic rescue-missions in the hellish jungles of Japanese-occupied Burma.At the age of 53, Mackrell – a decorated First World War pilot, then overseeing tea plantations for a company called Steel Brothers – went into the ‘green hell’ of the Chaukan Pass on the border of North Burma and Assam. Here, in what became a three-phase mission, he rescued Indian army soldiers, together with British civilians and their Indian servants, from the pursuing Japanese, directing his elephants through jungle passes and over raging rivers, through territory previously unseen by any white man and infested with sand flies, horse-flies, mosquitoes and innumerable leeches. Those he saved were all on the point of death from starvation or fever: the whole of that summer was spent in a fight against time.The most astonishing aspect of Gyles Mackrell’s heroics is that they have yet to be fully dramatised. Now in Andrew Martin’s hands they are given the shape of a suspenseful adventure, a wartime rescue whose facts are the stuff of Commando Comic-fiction. But he has also made a classic in the kingdom of animal fiction, with a starring species as awesome as literature’s most powerful horse, as exotic as its most elusive whale, as loveable as its most faithful dog. And finally Martin has pointed a portrait of war and of jungle-survival from an historically under-nourished point of view; a picture of fading British imperial virtues at their most dignified and robust. This book’s appeal will embrace together for the first time those happy disciples of adventure, history and the elephant.