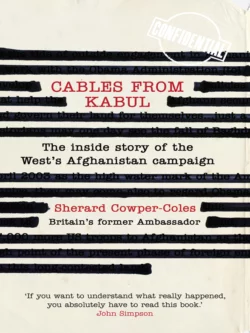

Cables from Kabul: The Inside Story of the West’s Afghanistan Campaign

Sherard Cowper-Coles

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Политология

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 1174.18 ₽

Статус: В продаже

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: A frank and honest memoir by Britain’s former ambassador to Kabul which provides a unique, high-level insight into Western policy in Afghanistan.The West’s mission in Afghanistan has never been far from the headlines. For Sherard Cowper-Coles, our former Ambassador, Britain’s role in the conflict – the vast amount of money being spent and the huge number of lives being lost – was an everyday reality.In Cables from Kabul, Cowper-Coles takes the reader on a journey through the backstreets of Afghanistan’s capital to the corridors of power in London and Washington. He pays tribute to the tactical successes of our soldiers but asks whether these will be enough to secure stability. Nobody is better placed to tell this story of embassy life in one of the most dangerous places on earth. Powerful and astonishingly frank, Cables from Kabul explains how we got into the quagmire of Afghanistan, and how we can get out of it.