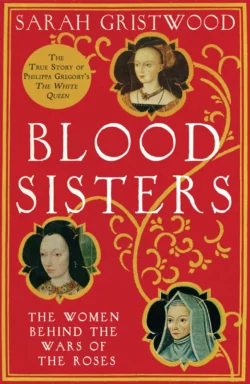

Blood Sisters: The Hidden Lives of the Women Behind the Wars of the Roses

Sarah Gristwood

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Биографии и мемуары

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 619.36 ₽

Статус: В продаже

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: A fiery and largely unexplored history of queens and the perils of power and of how the Wars of the Roses were ended – not only by knights in battle, but the political and dynastic skills of women.The events of the Wars of the Roses are usually described in terms of the men involved; Richard, Duke of York, Henry VI, Edward IV, Richard III and Henry VII. The reality though, argues Sarah Gristwood, was quite different. These years were also packed with women′s drama and – in the tales of conflicted maternity and monstrous births – alive with female energy.In this completely original book, acclaimed author Sarah Gristwood sheds light on a neglected dimension of English history: the impact of Tudor women on the Wars of the Roses. She examines Cecily Neville, the wife of Richard Duke of York, who was deprived of being queen when her husband died at the Battle of Wakefield; Elizabeth Woodville, a widow with several children who married Edward IV in secret and was crowned queen consort; Margaret Beaufort, mother of Henry VII, whose ambitions centred on her son and whose persuasions are likely to have lead her husband Lord Stanley, previously allied with the Yorkists, to play his part in Henry′s victory.Until now, the lives of these women have remained little known to the general public. In ‘Blood Sisters’, Sarah Gristwood tells their stories in detail for the first time. Captivating and original, this is historical writing of the most important kind.