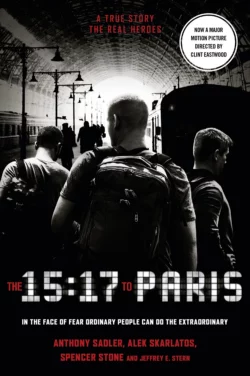

The 15:17 to Paris: The True Story of a Terrorist, a Train and Three American Heroes

Anthony Sadler и Alek Skarlatos

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Политология

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 861.19 ₽

Статус: В продаже

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: The 15:17 to Paris is the amazing true story of friendship and bravery, and of near tragedy averted by three heroic young men who found the unity and strength inside themselves when they – and 500 other innocent travellers – needed it most.On 21st August 2015, Ayoub El-Khazzani boarded train #9364 in Brussels, bound for Paris. There could be no doubt about his mission: he had an AK-47, a pistol, a box cutter and enough ammunition to obliterate every passenger on board. Slipping into the bathroom in secret, he armed his weapons. Another major ISIS attack was about to begin, but Khazzani wasn’t expecting Anthony Sadler, Alek Skarlatos and Spencer Stone. Stone was a martial arts enthusiast and airman first class in the US Air Force, Skarlatos was a member of the Oregon National Guard, and all three were fearless. But their decision, to charge the gunman, then overpower him even as he turned first his gun, then his knife, on Stone, depended on a lifetime of loyalty, support, and faith.Their friendship was forged as they came of age together in California: going to church, playing paintball, teaching each other to swear, and sticking together when they got in trouble at school. Years later, that friendship would give all of them the courage to stand in the path of one of the world′s deadliest terrorist organisations.