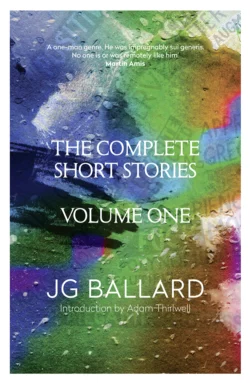

The Complete Short Stories: Volume 1

Adam Thirlwell и J. Ballard

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Современная зарубежная литература

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 1007.75 ₽

Статус: В продаже

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: First in a two volume collection of short stories by the acclaimed author of Empire of the Sun, Crash, Cocaine Nights and Super-Cannes.J.G. Ballard is firmly established as one of Britain’s most highly regarded and influential novelists. However, during his long career he was also a prolific writer of short stories, many of which show the germination of ideas he used in his longer fiction.This, the first book in a two-volume collection, offers a platform from which to view Ballard’s other works. Almost all of his novels had their seeds in short stories and this collection provides an extraordinary opportunity to trace the development of one of Britain’s most visionary writers.