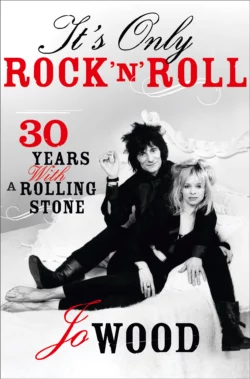

Its Only Rock n Roll: Thirty Years with a Rolling Stone

Jo Wood

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Биографии и мемуары

Язык: на английском языке

Стоимость: 623.51 ₽

Статус: В продаже

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв

О книге: Previously published in hardback as Hey Jo, this is a moving and candid memoir from the woman who married the most controversial member of the Rolling Stones, and had the strength and courage to bounce back from heartbreak.When young model and mother Jo met rock star Ronnie Wood, she had no idea what her brief flirtation with this brilliant, charismatic musician would become.A raw and rollicking narrative from the eye of the storm, Jo’s extraordinary story of life as a Rolling Stone girlfriend, then wife, mother and more, is a never-before-heard account of the heady hedonistic Ronnie Wood years – the drugs, the roadies, the tours, and the booze – and a celebration of her new-found happiness as an entrepreneur, fashion icon and beauty expert.Following the public breakdown of her marriage, Jo moved on with a dignity and lack of bitterness that won her fans across the country. Now a successful businesswoman, a passionate campaigner of pure, organic living, and a thriving name in fashion, Jo has learnt to embrace her new found vitality, and in doing so has become the heroine of everyone from 20-something fashionistas to Strictly Come Dancing devotees.This is Jo’s journey, from the breathtaking highs of her and Ronnie’s shared infatuation and love, to the devastating lows of his sudden disappearances, drug-induced mania and seizures, and how she learned to walk away without regret or bitterness, and forgive.