Saluki Marooned

Saluki Marooned

Robert Rickman

“Saluki Marooned”

Robert P Rickman

Edited by Nathan Beck

Copyright 2012 Robert P Rickman

Second Edition Published by Tek Time

All rights reserved

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

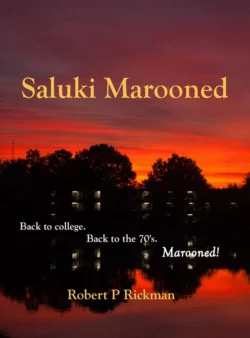

I spent nearly 8 years staring at a computer screen, with my mind in the 1970s, as I wrote this novel. Though it was a solitary job, I wasn’t alone because I had Nathan Beck, ‘07, as a consultant. Nathan, who received his MFA from SIU, took a broadcast writer and taught him how to write fiction. Sandra Barnhart of the Carbondale Public Library played an essential role in the formatting of the manuscript for publication. Mary Mechler, MBA ‘93, of the SIU Small Business Development Center helped me to develop a marketing plan for Saluki Marooned and also tutored me on everything from website development to business cards. The cover photograph of the Campus Lake at dusk was shot by Taylor Reed, BA ‘09. Bob Kerner of La Vergne, Tennessee, took the picture for the back cover. Though Bob is not an SIU alum, he did wear a maroon t-shirt for the occasion. The SIU Alumni Association has helped with marketing the book to alumni all over the world. Finally, special thanks to SIU Radio and TV graduates Bob Smith, ‘73, and Roger Davis, ‘72, who assisted with the marketing and proofreading of this novel.

Forward

Two wild rivers splashed together in Mid 20th Century America—the peace movement, and youth. It was one big freak out, with kids grooving to the gnarly music, mod threads, kickin' stash, swingin' chicks, and violence. UC Berkley led the way with campus unrest.

2000 miles to the east stood the Berkley of the Midwest—Southern Illinois University at Carbondale. In 1969, an arsonist torched Old Main, its oldest building. When the National Guard killed four students at Kent State, Ohio in the spring of 1970, riots closed SIU and its president resigned.

Adding to the edginess was an extensive rap sheet for the southernmost thirteen counties of Illinois. The most violent earthquake in the contiguous 48 states shattered the region during the early 1800’s. In 1922, 23 coal miners were killed during the Herrin Massacre. The Great Tri-State tornado, deadliest in American history, struck in 1925 killing 695 people. Below ground, the New Orient Mine explosion took the lives of 119 miners in 1951. And in more recent times, the May 2009 inland hurricane spawned three tornadoes in Southern Illinois, which uprooted trees, blew out windows and demolished buildings.

That Fall 58-year-old Peter Federson wandered onto SIU after binging on drugs and alcohol. Deeply depressed, the former Saluki crawled under a canoe on the lake, fell into a stupor and joined the region's long list of extraordinary statistics. Because, when Pete awoke in 1971, the world was out of kilter, just as he had remembered it.

Chapter 1

There is something wrong with my emotional thermostat; good things make me nervous, bad things make me even more nervous, and uncertainty drives me wild. Yet I loathe boredom and routine. It’s been that way for my entire 58-year life.

Gleefully twisting the dial of my thermostat is a squadron of gremlins, living deep in my mind, which pry out bad memories, distort them into parodies of themselves, grossly amplify them, and propel them rudely into my consciousness. The gremlins use my memories to bludgeon my tender nerves until I writhe in agony.

There is a line of these chemicals—because that’s what they are, disarranged brain chemicals—that begins in the late 1960’s and stretches to the present. This long and jagged line represents a demonic resume of my work history. I have been employed as a security guard, proofreader, adult school instructor, janitor, server, ticket taker, carpenter, bar disc jockey, radio disc jockey, photographer, and grocery store bagger. After I flunked out of college, I was a private in the United States Army. That was the worst job.

The best job was working as a news reporter and anchorman at radio stations in Iowa and California. Being on the air is my number one talent; the thing that I am tailor made for, except that I couldn’t tolerate stress for very long. I could bottle it up for a while, maybe for months, and occasionally years, but eventually the cork would pop off with a bang, releasing the fulminating gremlins. Then I would either walk out on the job, get fired, or a sometimes combine the two so that both former employee and former employer were confused as to what exactly happened. I was fired from my last job in radio in 1999 when I got into an argument with the news director about how to pronounce “Des Plaines,” the name of a Chicago suburb. Since I’m from Chicago I told him the right pronunciation was Dess-Planes. Yet he went on the air with the some strange French pronunciation, and I called him a frog. I didn’t know he was of French descent.

My latest gig ended in the usual spectacular way on a bright fall day in 2009 at a company called Testing Unlimited, located down the street from where I lived in Fox Lake, Illinois, another suburb of Chicago. The job was classified as part time/occasional, which meant that I couldn’t claim unemployment insurance, had no benefits, and worked only six to eight months out of the year. Some weeks I didn’t know what days I would work, or how many hours per day. I was comfortable with that, because the job offered me absolutely no security, and though the lack of security was bad, the idea of a change to something better was even worse.

With a big smile, the manager called our work the intellectual equivalent of ditch-digging. A group of a hundred of us—all with some college under our belts—sat on folding chairs, two chairs to a table, with a computer monitor, a keyboard, and a mouse in front of us. Our job was to score elementary school tests. Sometimes there would be paragraphs about a kid’s favorite pet; other times we’d score entire essays about what a the child did on his summer vacation.

The last ditch I dug for the company involved how to spell the word “cat”. Our instructions at the beginning of the project were simple: “cat” spelled correctly was worth two points, and if the spelling was close, like k-a-t, c-u-t, or c-o-t, we scored one point. Everything else earned a 0. But the parents of one child challenged the scoring with the logic that an r-a-t could be chased by a c-a-t, and a rat was also a four-legged animal with a tail, and should therefore be given one point because a rat was close in spelling and general appearance to a cat—if it was a big rat and a person squinted. The state board of education sided with the parent, and from that, the rubric morphed from two simple sentences to five pages of convoluted instructions. We had to complete 6 papers per minute, 360 papers per hour, 2700 per eight-hour day, with two fifteen-minute breaks and a half-hour lunch. The computer kept tabs on us with ruthless accuracy.

After a month of c-a-t, r-a-t, b-a-t, s-a-p and “friend” (1 point), my brain started to wander, which led to a drop in accuracy and speed, and a whole lot of fear. So I decided to set production goals and keep track of my progress by making a tick mark on a sticky note every time I scored a paper.

One afternoon in the fall of 2009, I had my thick glasses slid down on my nose so that I could see closely, and was counting tick mark number 552 when suddenly Jim, the head ditch digger, shattered my concentration.

“Ahhh Peter,” he said, speaking in his soft monotone.

The pencil flew out of my hand. “What?”

“Take a look at this paper…” He leaned over me, tapped a few letters on my keyboard, and clicked the mouse. A paper came up on the screen.

“…it should be a one,” he said.

I scowled at him. “It looks like c-a-t to me.”

“Well, if you look closely at the last letter, what appears to be the crossing of the ‘t’ is only a stray mark.”

“It still looks like a ‘t’ to me.” I looked at him hard.

“I showed it to Becky, and she agrees with me that the last letter is not a ‘t’, so we need to change the score to a one.”

“We do, huh? Well, how long did you and Becky spend studying this letter?”

Jim looked uncomfortable.

“About ten minutes, then we took it to Bill—you know Bill, the project captain—and he examined it with the Challenger Program. You know, the special program that uses fuzzy logic to analyze a child’s writing. Anyway, Bill agreed with us that it should be a one.” Jim was staring at me now.

I turned to him and asked, “Well, then, who the hell is scoring this paper, you, Becky, Bill, or me?”

“Why you are, of course.” Jim looked frightened.

“Fine, then it’s a two.”

“Mr. Federson, I think we need to talk with Bill.” Suddenly, mellow Jim wasn’t so mellow anymore.

It’s hard to understand how a person with a PhD, two people with Master’s degrees in English, and a guy with two years of college (me) could get into a shouting match over how to spell c-a-t, but we did, and that’s how I lost my job with the testing company. As usual, it was irrelevant whether I walked out on the job or was kicked out of it. As a parting shot, “Project Captain” Bill suggested I seek professional help.

Yah, like I’ve never heard that before.

I threw my ID badge on the receptionist’s desk, stalked out into the parking lot with stern resolve and…couldn’t get the door open to my 1976 Dodge Charger. After hammering it with my fist a couple of times, the door opened with a rusty screech, and soon I was roaring out of the parking lot in a cloud of blue smoke.

I drove around aimlessly, burning precious gas while I burned off my anxiety. The Charger was a broken-down mess; I never washed or waxed it, never changed the oil—never even looked at the dipstick—and never fixed the huge dent on the left rear panel. The dash was cracked to pieces. The radio and air conditioner hadn’t worked for years. Fast food wrappers, grocery receipts, and brittle envelopes of old mail covered the floor. And in the back seat rose a pile of dirty laundry that had been accumulating for weeks. I glanced at the pile through the cock-eyed rearview mirror, then looked down at what I was wearing: a dirty pinstriped business shirt with an unbuttoned collar and mismatched socks. As much as I hated the routine, it was time to do the laundry.

Soon, I was parked at the local laundromat and, as usual on laundry day, my temper was rising because I was reliving a memory of someone taking my wet clothes out of the dryer, throwing them in a heap on the floor, and putting his clothes in their place. This gremlin-enhanced memory came from an incident in the dorm laundry room while I was attending Southern Illinois University in 1971. As usual, the gremlins tormented me as I watched my tattered 2009 clothing spin around in the dryer. When the dryer stopped, I reached in to test the clothes.

Still wet! Shit!

As I was reaching into my pocket for two more precious quarters, my fingers touched the sticky leather case of my cell phone. I hadn’t talked with Ronald Stackhouse for a while. He had helped me organize my thinking when I worked for WSIU, the radio station at Southern, so that when the record ended I wasn’t sitting there with nothing to say. In 1999, he helped me to find another job when I got blown out the door of WREE, the all-news station, and helped me get back on my pivot when I was axed from the security, proofreading, and janitorial jobs. He always handled me with great tact, as if not being able to hold a job, though troubling, was just a glitch in the grand format of life. Ronald was stability personified, so the gremlins were afraid of him.

I punched the speed dial, but nothing happened because the battery was dead again; it had virtually no charging capacity left. I stuffed the phone back into my pocket quickly, before I surrendered to the impulse of throwing it against the dryer.

An hour later I threw the clean laundry into the back of my car, a place it would stay for another few weeks, for it was destined to make its way back into my house piece by piece, as I needed it. Change was stressful to me, even small changes. And, as of the fall of 2009, I was making fewer and fewer changes in my life because I didn’t want to risk losing what little I had.

I stumbled over the cell phone adapter on the back seat, plugged it into the cigarette lighter, and called Ronald. Before he could even say “Hello” I barked,

“Goddamn it, Ron, this has been one hell of a goddamn day!”

“Who? What? Oh, it’s you, Pete.”

“Damned right it is! I’m at the laundry, and do you remember that son-of-a-bitch who yanked my wet clothes out of the dryer and threw them on the floor when we were in college?”

“He did it again?”

“Oh, funny, Ronald! Do you remember?”

“Pete, that was almost forty years ago.”

“Well, it seems like yesterday because I got pissed off all over again while I was watching my laundry in the dryer a few minutes ago.”

“And?”

“Nothing else, just that.”

“Pete, have you been drinking a lot of coffee again?”

“Not yet. That’s the next stop.”

“Well, don’t. You know that coffee exacerbates your, uhhhhh, you know…”

As Ronald’s voice trailed off, I started the car.

“Ronald, I lost my job today,” I said as I drove out of the parking lot.

“What, not a….uhhh…what happened?”

“The usual. An argument.”

There was a long pause at the other end. I turned out into the street.

“Pete…” Ronald said. “You know the format: take a few days off, update the resume, get your nice clothes ready for an interview…”

I’d heard this advice many times from Ronald. And every time he was right.

“I might have something you can do for me…” Ronald continued. “Do you still have that good mic of yours, and a laptop? Are you still connected to the Internet?

“Yah.” I knew what was coming.

“Well, you could read a few newscasts a day for the station. You won’t have to cover any news. You won’t even have to write it, and the money’s good.”

Ronald worked at WSW in Omaha.

“Ron, I’m burned out on radio…I…”

I was starting to tear up, and I think Ronald sensed it.

“Pete, look. Take some time off. Get your head together, and call me back in a few days, and we’ll talk. Okay?”

“Okay,” I choked.

I didn’t know what Ronald saw in me. I really didn’t.

I threw the cell into the back of the car, and it landed on top of the laundry pile just as I rolled into the Shop King parking lot. Shop King featured not only the cheapest groceries in Fox Lake, but also a 25-year-old redhaired beauty named Lilly. I found a bottle of Old Spice rolling around on the floor, splashed a copious amount on my face, and went in.

In a few minutes, I was standing at the end of Lilly’s line, carrying a basket that included a 16-ounce jar with a black and white label that simply said PEANUT BUTTER. Lilly lifted me out of morbid depression and into boundless joy as she scanned the peanut butter, a loaf of 99-cent bread, a small onion, and a small jar of mayonnaise. When she got to the tuna fish, I was ready to make my move.

“This isn’t really for me,” I said. “It’s for my pet tiger.”

Lilly looked up with expression of disinterest. She knew it probably wasn’t worth the energy to respond, but since she was already bored to distraction, almost any stimulation would be welcome.

“Pet tiger?” she said.

“Yeah, he’s in the car. Do you want to see him? He loves nice girls.”

Oops, that was dumb.

Lilly’s expression hardened.

“No, my boyfriend doesn’t like tigers,” she said as she thrust the plastic bag full of groceries at me. She made sure that when I took the bag, our fingers didn’t touch. She quickly turned to the next customer, our interaction forgotten.

I fell back into profound depression, but sauntered toward the exit, acting as if I were the happiest person in the world. I even whistled a fragment of a Liszt rhapsody.

The gremlins ripped the bag as I was placing it in the van, scattering the groceries in all directions. There was no way to evict these destructive little bastards. The professionals had tried. One counselor drew a circle and put a dot in it, which represented “the self,” and for eight weeks, in dozens of ways, he impressed upon me that most people’s “selves” are essentially good, and that the problems occur in the outer circle. People are good, but their actions are not. Another time, a psychiatrist put me on tricyclic antidepressants and Paxil for anxiety. Then he prescribed Ritalin to offset the energy-draining effects of Paxil and treat a side problem, Attention Deficit Disorder.

“Better living through chemistry,” said the psychiatrist with a jolly grin as he wrote out the prescription.

Everything I tried worked for a while, until my brain rebelled from everyone constantly tinkering with it. I forgot that people were essentially good, and began to need larger and larger doses of the drugs to counteract my anxiety/lethargy/hyperactivity/ depression/ADD. This led to fuzzier and fuzzier thinking, until by the summer of 2009, I felt as if I were losing my personality and turning into a hard drive.

My next stop was the Mellow Grounds Coffee Shoppe and Croissant Factory, located in one of those modern buildings that’s made to look as if it were built a hundred years ago. The modern plaster walls were artfully designed to appear cracked and peeling; the straight-backed chairs were probably 70 years old, and the slate-topped tables looked like they had come from an old high school biology lab where frogs were dissected. People loved the place because it “reminded” them of good old days they had never lived through.

Every time I walked in there, I felt pain in my right rotator cuff and a surge of anger. Like the laundromat, the coffee shop reminded me of an unpleasant incident, this time on a summer morning in 2008 at the Demonic Grounds Coffee Emporium, across town. That morning I had taken my usual doses of Ritalin, tricyclic antidepressants, and Paxil, and felt as if I were teetering on a knife edge between sullen apathy and hyperactive outrage. When I found out that I had been charged for a triple latte, after being served only a large cup of plain coffee, I demanded to see the manager. After a short discussion, I came down on the side of hyperactive outrage and swung at him, missed and fell against the wall, banging my shoulder and head, which dinged my rotator cuff and crashed the hard drive, so to speak.

After getting out of jail the next morning, I threw the drug container across my bedroom and left a nasty message on my psychiatrist’s voicemail, thus ending our relationship.

By the fall of 2009, the gremlins had awakened from their drug-induced coma and were pounding my brain once again. This caused a buzzing sensation in my solar plexus, which I call the “heebie-jeebies.” I wished there was a drug that could purge me of the heebie-jeebies. They could purge the bowels, so why couldn’t they purge the mind?

At Mellow Grounds that evening, I tried to use sheer will power to avoid an explosion of temper after the Lilly debacle, but the barista had sided with the gremlins. He was talking both to me and to someone outside at the drive-thru window with one of those boom microphones growing out of his ear. He looked like he’d feel at home in any air traffic control tower in the country. After the usual confusion as to whom he was addressing—the irritated driver at the drive-thru or the heebie-jeebie-suffering patron standing right in front of his face—I received my coffee and sat at the nearest dissection table. The barista looked relieved.

As usual, I was pitifully lonely, and had a vague, unrealistic idea of interacting with someone that evening. But, of the 20 or so people in the coffee shop, it seemed that all were texting, talking on their cell phones, listening to their iPods, working on their laptops, or reading their eBooks. Everyone was connected, except for me.

I chugged my Grosse Sud Amerikaner Kaffee, which, translated into 20th century English, was “a large cup of coffee.” Perhaps it was too large, because as I stood up, I felt as if the back of my head had blown outward and the stuff inside was jetting me toward the door at a terrific speed. Yet my thinking had slowed down so that I could see every pseudo-crack in the plaster wall in fantastic detail. My mind started fragmenting like that plaster, only in my case there was nothing pseudo about it.

The drive home, through film noir-harsh street lights and darting black shadows, took ten minutes. As I pulled into the entrance of my trailer park, the one working headlight on my car lit up my miniature front yard with a preternatural glare, changing the faded green of my trailer to a chalky white. The TV antennae on the roof looked like a deranged pretzel thanks to a storm ten years before, and a jagged shadow fell away from the mailbox pole that I had hit with my car last year. The headlight revealed a discoloration across the entire front of the trailer that I hadn’t noticed before. I jumped out of the car, pressed my glasses to my nose to sharpen my vision, and saw that the entire side wall of the unit was delaminating from its frame. I needed to do something about that fast, because my trailer was coming apart, and squinting up at it, I thought, And so am I.

Chapter 2

The next day I woke up at noon with a coffee-induced hangover, and for a few seconds, I thought that was the worst of my problems. But as I rubbed my eyes, the mild anxiety that ran through me as a chronic undercurrent quickly expanded into a full-blown heebie-jeebie attack. I had lost my job. The gremlins plucked a cluster of nerves encircling my heart and jolted me to my feet. I ran into the kitchen to the only drawer in the trailer that was organized and grabbed a pen, a piece of paper, and an avocado that had disappeared that summer. I threw the avocado into the overflowing garbage can near the sink and cleared debris off the kitchen table with a swipe of my arm.

In a masterful letter to Testing Unlimited, I questioned the wisdom of state governments mandating standardized tests for first graders to show how smart their kids are, so that the state receives more federal money…for more testing. I also felt it was a waste of money to pay college-educated people $10 an hour to analyze the spelling of “cat.” At the nearly-illegible end, I wrote a filthy word and suggested that one of their $13-hour PhD test scoring supervisors read the word to the Board of Directors to see if they could spell it. I signed the letter with a scrawl, stuffed it into an envelope, addressed it, stuck three or four stamps on it, and went outside to the mailbox.

The trailer park had looked good when I moved there in 1989, but now the grass was sporadically mowed, the rocks along the drive were displaced, the dumpster was overflowing with garbage, and many of the residents had the haggard look of people who worked underpaid full-time jobs, then went directly to their underpaid part-time jobs so they could afford their $600-a-month lot rents and gas for their 15-year-old cars.

The mailbox was stuffed mostly with junk mail, on top of which was a letter from my folks. I pulled the glasses to the bottom of my nose to read the letter. It seemed that it cost Mom and Dad a few thousand dollars to convert the front yard from grass to gravel. But, it would save the cost in water many times over. It seemed that Los Angeles was in the midst of yet another drought.

Under my folks’ letter was a bill from Harry Morton, M.D. Usually, I would not even have opened the bill, but a perverse desire for undesirable stimulation—the gremlins hate boredom—prompted me to tear open the envelope. The first thing I saw was the figure $4,579.92, the cost of a CAT scan I had undergone six months before. My general practitioner had thought I needed a chest X-ray because of a chronic cough and had sent me to a cardiac specialist, who in turn remanded me to the CAT scanner because I had moderately high blood pressure, that was treated with an ACE inhibitor.

I tried to tell everyone that the cough was caused by the ace inhibitor, which I had stopped using. The cough had stopped, too. But my GP insisted that I needed the chest X-ray, and the cardiologist insisted that I also needed a CAT scan, even though the stress test electrocardiogram and the other tests all came out normal.

“You can’t put a price tag on your health,” the cardiologist admonished with a used car salesman’s smile.

“Relax, I just called your insurance company. They’re covering it!” the medical assistant chimed in.

My insurance paid $77.64.

The results? High blood pressure controlled by medication, which caused a $4,502.28 cough.

Clutching the mail to my chest, I walked up the jagged path to my front door and tossed everything on the floor with the rest of the debris. Craving the hair of the dog that bit me, I opened the pantry, shooed away the cockroaches, opened a fresh can of chicory-laced coffee, and made a pot, black as coal, just the way I liked it. Stay at home, hunker down, drink coffee, and avoid all nerve-provoking stimulation. That was the ticket.

But I kept looking through the mail anyway. Next in the pile was another unwelcome letter from Marta, a hippie I’d met years ago while at SIU. Out of the blue, after almost 40 years, a series of letters from Marta had started arriving that summer. I’d never replied to any of them. The letters absolutely baffled me, but I read them anyway because they were so…interesting. This one was absolutely fascinating:

Dear Peter,

I trust everything is cool with you. Hopefully you and the instrument have reached an epiphany, and your life is in the groove by now.

Do you remember what we talked about while at SIU; that science will solve your problems? Well, if not science, maybe magic!

Hah, Hah.

If life has changed for you, you’ll know what I mean. But if it hasn’t, then you won’t know what the f--- I’m talking about. In any event, write me. I’d love to hear from the sanest guy I‘ve ever met.

Your friend,

Marta

I didn’t remember talking with Marta for more than two seconds, only to say “Hi” and “Bye” in the cafeteria at college, forty years ago. For the first time, I looked at her return address, which was illegible except for “Carbondale” and the first letter of her last name, which was an M. I took her cryptic letter and threw it at my new mail drop: the floor. By then, I had lost patience with tearing open envelopes, and threw the rest of the unopened mail on the floor as well.

I checked the front door to make sure it was locked. Although I had little tolerance for routine, I had even less tolerance for surprises. I didn’t answer the door unless I was expecting someone, and made sure I was expecting no one. Ditto for answering the phone and returning emails. I figured that if I didn’t read, see, or hear bad news, then the gremlins would have no tools to torture me.

I also chose to do without making decisions, even small decisions, such as how to clean my trailer, which caused me to be “conflicted,” according to the head shrinkers. A dust mop had been leaning against the wall in the bedroom for more than a year because, for the life of me, I couldn’t decide where to start the cleaning project. Should I vacuum the carpet first? The carpet was covered with stains, coffee grounds, eggshells, dirt, paper and what looked like dried-out olives. But to get to the rug I’d have to pick up all of the clothes off the floor, and they needed to be washed, didn’t they? But if I threw them in the car they’d get mixed up with the clean clothes in the back seat. So to get around that, I decided to leave the clothes where they were, and wash them individually in the bathtub as necessary.

And what about the tub? I hadn’t cleaned that since before the water heater had broken that past winter. Maybe washing the clothes there would clean the tub, but that left the filthy sink and toilet. In what order should I clean them? Until I figured that one out, they’d have to stay dirty. On a positive note, I considered the oven and the stove to such messes that they would be impossible to clean, so I didn’t have to decide which to clean first. And the refrigerator really didn’t need to be cleaned, either, because it had died three years ago, and anything in there was safely out of my sight as long as I didn’t open the door.

Hiring someone to fix up the place for me was out of the question, not only because I couldn’t afford it, but because another human being walking into my squalor would pin the needle of my anxiety meter deep in the red.

It had taken five years for the parallel deterioration of my home and my mind to progress to this point: I was now living and thinking like a street person.

Nevertheless, through my mental malaise I dimly realized that human relationships keep a person sane. But that depends on the people one is interacting with. Other than Ronald, my “friends” were intimate with their own personal gremlins.

There was Bob, for instance, who I’d met at an AA meeting. From time to time over the years, we’d sit and drink coffee all night long, scheming to make money. In the summer of 2007, we’d planned to sell water filters to trailer parks. We figured that the filters would keep the trailers’ hot water tanks from corroding with minerals, so they wouldn’t have to be replaced so often. The plan was to divide up the territory, with Bob phoning twenty-five trailer parks in the northern half of Illinois during the week, while I made twenty-five nerve-racking calls to trailer parks in the southern half. We agreed to touch base by phone the following Friday.

When I asked Bob about his progress, he responded: “I’m just about finished.”

Which meant he hadn’t even started yet.

After making another heebie-jeebie-inducing twenty-five calls the next week, I called Bob again.

“Oh yah, I’ve almost finished,” he said.

This meant he had just gotten started.

A week later I called once more and left him a message, which was never returned. Several more calls and emails went unanswered as well. Six months went by with no Bob, until finally, he popped out of the ether like an electronic jack in the box.

“Hey, I’ve got a great way to make money. We can sell collapsible shields for laptops so people can work in the sun, and the screen won't be washed out...”

The water filter project was never mentioned again, because Bob was avoiding accountability by hiding in his home surrounded by an electronic moat teeming with unanswered emails and ignored voice messages. He was like a child who was playing blocks with one of his friends, saw another friend playing marbles, and ran over to play with him for a while, until he spotted a kid climbing a tree, and ran to join him. Bob had never grown up.

And then there was my former wife Tammy, who changed her name back from Tammy Federson to Tammy Allen. Once upon a time, she’d been really good-looking. She was also intelligent and her parents had money. I was head over heels in love with her when I was at SIU in the early 70’s. But Tammy was attending the University of Illinois 100 miles to the north, so it was a long distance relationship. When I flunked out of college and joined the Army, we stayed in touch, with letters and phone calls during those two years. We did everything but truly get to know one another. After I came home, we got married immediately, and finally, finally, we were together, and it was paradise…for about six weeks. We found out the hard way that we were indeed made for each other. In fact, Tammy and I were as interchangeable as two peas in a pod—two nervous people living together, which made our union about as happy as the marriage between a jackhammer and a buzzsaw. We divorced childless, I saved no photos from the marriage, and I never wanted to talk to her again. I still didn’t want to talk to her. Yet…

I went out to my car, retrieved my cell phone from under the clothes, and dialed Tammy’s number. Even a conversation with a jackhammer would be better than silence. I sat down on the kitchen chair, but felt my bottom touch the seat only after a long delay. I started to feel woozy, something like the sensation I got after a roller coaster ride at Riverview—a big amusement park on the Chicago River—when I was a kid. The heebie-jeebies ran up my spine as I greeted Tammy with:

“I lost my job yesterday, and I’m feeling as if I’m moving when I’m really standing still...”

“Oh that’s too bad. They’re threatening to foreclose on my house,” said Tammy.

“What, again?”

“Oops, hang on, I’ve got another ca—“

Two minutes later Tammy came back on.

“That was them, and this time, they mean it,” Tammy said. “They told me that unless I pay at least $600 of the $7000 I owe them from the past six months, they’ll start eviction proceedings.”

Tammy kept hopping from one crisis to another, with her cell phone in one hand and her computer’s mouse in the other, so that all of her “friends” would instantly get the play-by-play account. From Tammy’s stream of consciousness emails with no paragraphs, no capital letters, no spell check and only dots for punctuation, I’d learned that she was making $25,000 a year as a security guard, had her second ex-husband and her son cosign the loan for a $150,000 house, which depreciated by $50,000 because she couldn’t maintain it, and now she couldn’t pay the loan installments, either. She also owed another $80,000 on credit card balances, was driving around in her brother’s car, and frittering away her money by eating at fast food places, devouring chocolates, and enrolling in pricey weight loss programs.

“Tammy, I’ve told you again and again…” I was starting to get worked up.

“Hang on, Pete; I just got another ca—”

Five minutes later: “Back with you, Chet,” chirped Tammy.

“It’s Pete, goddamn it!”

“Don’t you talk to me like…”

“Listen, Tammy, you can’t possibly pay for that house on what you’re making. You need to get rid of—”

“I’m never going to sell it! No apartment will allow twelve cats, it’s worth less than it was when I bought it, and I don’t want to drag my son into bankruptcy and ruin my good credit, and shit, I got another call. I’ll text you—”

And Tammy was gone in a storm of text messages and call waiting. She wasn’t much different from Bob, except that Bob hid in cyberspace, while Tammy bombarded people with endless communications, so that she would have no time to listen to anyone. By the end of Tammy’s electronic monologue, my teeth were clenched and buzzing. I took a deep breath, exhaled, and suddenly, it was awfully quiet in the Federson household, and awfully boring.

I was sitting with the coffee mug resting on my knee, amidst the mail and books, in a nauseous funk on the floor of an eerily quiet kitchen. To quickly fill what I knew would be a lonely, unbearable silence, I turned on the radio to WFMT.

I gulped down the last of the coffee as Liszt’s 1st Piano Concerto began with Martha Argerich at the piano. When Martha punched out her first chords, they resonated in my solar plexus, displacing the gremlins and stimulating me to action. Soon, I was full of gremlin-resistant, heebie-jeebie-blocking positive energy.

I needed to move, to get something done, something tangible. I needed a project and that required a decision. I spotted the dust mop that had been leaning against the wall for so long that it had left a mark.

Decision made!

I poked the mop under the bed and pulled out bits of rotted food, dead insects, dust bunnies, dirty pens, napkins, wadded-up notebook paper… and a bottle of pills.

That’s where they went.

At one time, I had put all of my pills—uppers, downers, pills for depression, pills for lethargy, and pills for anxiety—into one big bottle. The rationale was that it would be harder to lose one container than five. Right? Then I lost the bottle by forgetting about it after I’d thrown it against the wall the year before.

Another swipe with the mop revealed the presence of The Excitement Of Algebra!, a library book due two years ago. A few years before, I’d had some ideas about going back to college to get my Bachelor’s degree, but I had to repair my miserable undergraduate GPA first. At the top of the academic list was algebra. I had failed it twice in high school and twice in college, and spent so much time obsessing over it that my other classes suffered, which was why I’d flunked out of the university at the end of my sophomore year. With a low draft number, I’d traded the dormitories of college for the barracks of Vietnam. Within 24-months, the Army and I parted company—with prejudice—because my captain was convinced that I didn’t have what it took to be a soldier.

So, the gremlins had made sure that my study of algebra was indelibly linked to my tour of Vietnam. I threw The Excitement of Algebra!, which I had never opened, on the kitchen floor.

Next, the manic dust mop dragged out a clanking plastic Kroger bag with a stylized sketch of the American flag, under which was printed: 1776-1976. In this patriotic bag was a half-full fifth of vodka with a price sticker on the cap: $1.50. There was also a pocket watch with a fisherman etched on its cover that I had bought in Europe while on a student tour in 1970. Next to the watch was an old, yellowed computer-punched photo ID of me, made four decades and fifty pounds ago, and clipped to the ID was a bright photo, taken in the super-realistic colors of Kodachrome, of an olive-skinned girl with high cheekbones, brown eyes and curly brown hair parted in the middle.

Catherine!

The shade of red in the booth in which she was sitting was brightly saturated, and the dark wood wall behind her seemed to glow: Catherine was sitting across from me in a booth at Pagliai’s Pizza in Carbondale, during my sophomore year of college. And for a moment, I was there again, sitting across from the girl I should have married.

In 1971, I’d plodded through my emotional life like a somnambulist. I’d dealt with my ever-present anxiety by ignoring all but the most superficial human interactions. Catherine Mancini was a girl of Italian descent who lived with her family a few miles down the road from SIU. She was pretty in a country way and had a cute way of talking, a combination of a Southern and Midwestern dialect. I loved the way she said “quit” (“kuh-wit”). She’d said “quit” to me a lot. But what set Catherine apart from the other girls I’d dated during college was that her personality was made up of a critical balance of empathy and assertiveness that could have awakened me from my emotional slumber, had I allowed her to.

I didn’t remember much about my college years or the drab intervening decades. Liberal doses of vodka and pills had darkened or blotted out most of the memories. But I did recall that Catherine had tried to lead me out of the haze, and I pretty much ignored her. And when we finally broke up I wasn’t even upset about it, because I was smitten with Tammy, and so I relegated the memory of Catherine—who I was much better suited for—to a Kroger bag.

And now I was kneeling at the side of the bed with the mop and staring at the photo of a pretty young girl whose image I hadn’t seen in nearly forty years.

The contents of that grocery bag condensed my life story into a Tweet: Opportunities offered me@frightened. Opportunities terrifying@scared. Opportunities rejected@misery

I thought about my Testing Unlimited! job with c-a-t and r-a-t, Bob with his water filters, Tammy with her house, and me who never mastered algebra or broadcasting or anything else.

I looked at that slim, clear-eyed teenager on the student ID; touched my face, and felt the nerves running beneath my exceedingly thin skin. Muscles corded around the nerves until they tightened into lines of tension on either side of my jaw, like strings on a violin. The strings were wound too tight, so my neck was bent by the pressure. This nervous energy sunk my cheeks until they were hollow cups, traced wrinkles down either side of my nose like gashes, and drew dark rings around my eye sockets, from which crow’s feet radiated like jagged scars.

God, I wish I could start over again!

I dropped my hand from my face and it landed on the pill bottle.

I took two pills, washed them down with a swig of vodka, wound my watch, and stared at Catherine’s face. Soon, voices speaking gibberish and noises that sounded like rushing water and leaky faucets filled my head. I felt a sudden acceleration...

…And found myself sitting upright with my head lolling against a train window. Sunlight was bouncing off the glass of skyscrapers, passing through the window, and refracting deep in my eyes.

What the hell?

I was on some train, passing the massive black column of the Willis Tower—formerly the Sears Tower—in downtown Chicago. The train rumbled over switches and crossed over jammed expressways with ramps twisting in all directions. Soon I could see glimpses of Lake Michigan.

“Theh lake looks a little chee-oppy.” said some guy behind me.

A girl answered, “I think it was the storm that passed through lee-ast night.” The couple had the top-heavy accent that had evolved in this city of big shoulders.

“Deh ya remember last New Year’s when we nearly froze walking across theh Michigan Avenue bridge to theh Hancock tower?”

“Oh God, yes,” said the girl.

“It must have been ten below; theh white caps on the lake had free-OZ-enn. Theh wind cut like a knife!”

“Well, I won’t be missing it. Where we’re going it’ll be like Floridah.”

They must be from the west side.

And, as if in rebuttal, I heard in front of me:

“Can I use your ink pin? I can’t fahnd mine.”

The guy answered, “Here…” And then, “…I figure, if we git into Carbondale ontime, we’ll make Cairo by about 11:00.”

Keh-row? These people are from Southern Illinois!

Above the lake, the sky was crisp and well-defined, and looked colder than I thought it should look in early fall. What was it—September, October? I wasn’t good with dates. A bright maroon leaf drifted past the slowly-moving train. Soon, manicured green lawns appeared, then tract houses, and finally the black loamy Northern Illinois soil, whose furrows passed like rapid little black waves that never seemed to end. Wave after wave, after wave...

I started when I heard: “MAHHHHHHHHH-TOOOON…Mattoon is the next stop.”

The train was in Central Illinois.

I looked at my wrist, but my watch was gone, and I wasn’t wearing my cell phone either. I reached into my pocket and pulled out the pocket watch with the fisherman on the cover and snapped it open: 6:56. Somehow I had lost three hours and missed seeing most of the state of Illinois. My pill container was in my pocket, and since dusk was fading fast, I took what I thought were two uppers, and soon was grooving to the cadence of the train wheels skipping over the gaps in the track.

Dah-Dah-Dah-Daaaaaaaah!

It sounded like the beginning of Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony.

Dah-Dah-Dah-Daaaaaaaah!

Stupid-assed people with their “Making Fun of the Classics” ringtones.

“Hello?” said a young, disembodied voice in front of me.

Pause.

“….Oh yah, we’re on the Saluki about an hour from Carbondale.”

Pause.

“Not again! OK, you…you’re cutting out. I’ll call you tomorrow and see if we can deal with the issue. Yah, bye.”

Issue?

“Who was that?” said another disembodied voice.

“Kyla. I’m helping her with her term paper. She’s having some issues converting from Mac to Windows.”

And I’m having some issues with calling problems “issues.”

Issues, quality time, texting, gaming, ripping a tune, peeps…terms such as goal oriented, core competencies, thinking outside the damned box, and partnering…all of this grated on my ears like a fingernail scratching slate. Stupid understatements like, “I’m a little bit outraged.” Idiot expressions such as, “Sweet!” and the mere mention of the word frappuccino made me sick. The list was especially disgusting when everything was done at the same time—“multitasking.” And of course, all of it had to be accomplished with speed, speed, speed! It seemed that technology had accelerated the revolution of the world so that each minute was compressed into 55 seconds, each hour was now only worth fifty-five minutes, and every day had only 23 hours, yet people were expected to squeeze 25 hours into that same day. Humans weren’t biologically suited for this, so they either did a half-assed job of it, or went nuts like me.

I glanced out the train window, saw the last flush of a maroon dusk, and found a pink pill to extend it just a little bit more.

Dah-Dah-Dah-Daaaaaaaah! went the ring tone again.

“Yo,” answered the disembodied voice.

Pause.

“He did what? Oh hah hah hah hah haaaaaaah. Man, he dropped a hammer on it? That was really stupid, hah, hahhhhh. I bet, yah, he’ll be limping for a while after that. Hah, hah! Bye!”

And you’ll be limping for a while if you don’t stop that horse laugh.

Pause.

Dah-Dah-Dah-Daaaaaaaah.

That tears it!

I leaned over the top of the seat in front of me and faced two upside-down teenagers dressed in blue jeans and Tshirts. Both of their eyes bulged, as if an angry cobra was hanging over the seat.

“Alright, if I hear that goddamned ring tone again, I’m gonna throw the phone, and the idiot it’s attached to, off of this fuckin’ train,” I hissed.

The two kids froze for a second, then quickly collected their laptops, iPods, cell phones and other toys and hurriedly left the car, looking back with terrified glances.

Children shouldn’t be allowed in the same car as adults.

As I was starting to doze again, I felt an unwelcome presence sit down next to me. Out of squinted eyes I saw six gold stripes on a green sleeve.

“Hey fella, it seems like you’re having some sort of trouble.” The soldier wore a black beret and had a chest full of ribbons. He sounded like one of the people talking about Cairo earlier on the trip.

“I’m okay,” I said.

“I don’t think you are. You look like you’re being eaten up from the inside out. Let me ask you…are you happy with your life?”

“No.”

“People? Do you like people?”

“No.”

“Do you like anything?”

“No.” All I wanted to do was sleep.

“Listen fella, I was where you are now, about six months ago in Iraq. They told me that I had what is called ‘a thousand yard stare.’ Just before I planned to kill myself, someone gave me this.”

The soldier reached into his inside pocket, pulled out a mechanical pencil, placed it on the windowsill for a few seconds, and then held it up to my face. I slid my glasses over my brow and looked at the thing with my myopic eyes and saw clouds swirling around a maroon sunset inside the pencil—as if that simple writing instrument had absorbed a chunk of the sky while sitting on the windowsill.

“Sometimes writing things down helps,” said the soldier dryly.

“I’ve got plenty of pencils.” I didn’t want to touch the damned thing. I ignored the soldier, turned toward the window, and fell asleep again.

I was awakened by the train running over a switch. That’s when I saw the sign out the window—or thought I saw the sign…or maybe I imagined seeing the sign in the field stubble. Whatever the case, it burned itself onto my retinas like the after-image of a flashbulb. The sign was spectacularly ugly, a monstrosity supported by massive pillars hewn out of bituminous coal and painted in rude swaths of maroon and silver. Chunks of fool’s gold, glittering unnaturally in the dark, formed the words WELCOME TO SOUTHERN ILLINOIS! And below that, barely legible from the train window, was scrawled in maroon magic marker: IT’S GONNA BE ONE HELL OF A TRIP.

Chapter 3

I awoke to a dark, empty train car with the photo of a young Catherine in my lap, and placed it carefully into my shirt pocket. Through a dripping window I saw maroon-tinted, luminescent clouds descending over the roofs of old brick and wooden buildings burnished by light drizzle and stained orange by streetlights. The buildings were vaguely familiar, but distorted by an imperfect memory made decades ago. I had walked past these buildings many times during the two years I had attended SIU in the early 1970s. But the trees were different; many had entire limbs missing, and there were stumps here and there along the street. I had read about this. An inland hurricane had blasted through the region in May and left such incredible damage that it was still being cleaned up months later.

When I stood up, the blood drained from my head, leaving a thick sludge that weighted my head so that I was looking down at my feet. The sludge shifted ponderously around as I reeled to the exit door, slipped on the wet train steps, and landed in a heap on the ground.

Welcome to Carbondale!

With the help of a lamppost, I pulled myself to my feet and stood swaying like a bottom-heavy blow-up clown, then stumbled out onto the sidewalk and started a shambling walk down Illinois Avenue—the main drag—until I reached a coffee shop. The ache in my shoulder reminded me of last year’s brawl at Demonic Grounds, and I didn’t need a visit from the gremlins, so I chose to stay outside and behave myself. Yet I hung around the shop’s entrance, curious to see what modern SIU students looked like.

At first glance, they didn’t look much different than my generation did in the early ‘70s. Except: A kid walked in the door with a tastefully camouflaged backpack fitted with compartments for his laptop, cell phone, iPod, and one of those blessed water bottle-things we never had in the ‘70s. In the Vietnam era, students wore Army surplus backpacks with something like a peace symbol sewn raggedly on the flap.

The door to the shop edged open and a coed (Do they call them that anymore?) left the shop while awkwardly balancing three cups of coffee in her hands in an effort to avoid spilling them on her Versace jeans. When I attended SIU, I walked around in beat-to-hell combat boots, and our “designer” jeans were stiff-as-a-board bellbottoms that took a month of washings to soften up. Fashion-conscious students tie-dyed the jeans in the bathtub, then wore them until they fell apart—and no one gave a damn what was spilled on them.

Inside the shop, a petite girl sitting with a swimming pool-sized cup of coffee was sporting a short, razor-cut hairstyle, dyed the SIU colors—maroon with white streaks—and the guy sitting across from her had the same hairstyle, but in brown. In the ‘70s, our hair wasn’t “styled.” We either cut it ourselves or went to an old-fashioned barber and hoped he didn’t cut off too much. We wore our hair stacked on our heads like leaves of lettuce piled in a salad bowl or splayed out in all directions like frazzled steel wool pads. And no one thought of dyeing his or her hair maroon, pink, or any other color, because we wanted it to look “natural.” Besides, SIU students of the early ‘70s didn’t have that much school spirit, and except for an occasional school sweatshirt, we didn’t wear maroon and white.

I noticed a youth sitting on a paisley cushion and playing a guitar, who looked like he had been teleported there from 1971. The kid affected a scraggily beard and wore a torn T-shirt, dirty jeans, and scuffed combat boots. But the outfit looked too perfect, as if he had seen an old photo of a genuine hippie on the Internet and had practiced dressing like him. I suspected that behind the façade lurked a squeaky-clean college student, circa 2009.

But I did notice a hint of genuine rebellion in this coffee shop crowd, because students wore glasses with larger lenses than what most people wore in 2009, probably because small lenses were “in” for everyone else, which meant they were “out” for college students. But, aside from this mild ophthalmological revolt, the rebellious look of the ‘70s was no longer rebellious—it had been studied and refined until it was the standard for the 21st-century student.

Two guys tried to exit the shop at the same time and got stuck in the door.

“Sorry,” said one guy.

“Excuse me,” said the other.

Such politeness! In the ‘70s this place would probably have been a bar, the two students probably would have been drunk and stoned, and their abrupt meeting would probably have led to a fight.

Yet there was something particular to SIU that stretched across the generations. A few students almost furtively came through the door of the coffee shop, slumped over, and sat down with sheepish looks, as if they had been beaten into submission by the very act of attending Southern and felt they didn’t deserve to be in such a nice place as this one. I remembered the “Saluki slump”—Harry, my roommate, slumped liked that every time he entered our dorm room. But his was an arrogant slump, as if to say, “I’m here, no big deal, unless you want to make something of it.”

I stood outside the coffee shop window, staring at this terrarium of student culture, and the students stared right back at me, as if mesmerized by a poisonous snake. I could see why, because my reflection in the shop window showed two demonic eyes staring a thousand yards into the distance, with the red pupils almost indistinguishable from the bloody whites. It was a face that was anything but normal. I looked down, saw the footprints of an impossibly big dog painted on the sidewalk, and followed them south.

Just ahead was Pizza King. PK’s never served pizza while I lived in Carbondale, but I drank a lot of beer there, and the suds were flowing that night. However, across the street, the Golden Gauntlet nightclub was now a pet store.

Sad.

I sensed there was more missing, a lot more, but I didn’t see it immediately, so I stared down the street until it came to me.

The Strip is gone!

The Purple Mouse Trap, Das Fass, Jim’s, Bonaparte’s Retreat, the Golden Gauntlet and The Club were all missing. All of the bars along the southernmost three blocks of South Illinois Avenue had transmogrified into nice-looking, nearly upscale bicycle stores, donut shops, fast food restaurants, and places like the one I was standing in front of. The display window showcased several life-size dolls that resembled greyhounds with long floppy ears. The Saluki dolls were sitting in a circle of maroon and white megaphones, looking up in admiration at a female mannequin that was wearing absolutely nothing, not even hair.

Salukis and maroon and white in business windows meant the merchants now had school spirit, which was different from my time, when business owners rarely hung anything in their windows that reminded them of SIU. The conservative Southern Illinoisans frowned on student riots and impromptu street parties downtown. And they looked askance at the bombing of the Agriculture Building in 1968, the burning of Old Main in 1969, and the closing of the university during the spring riots of 1970. What a difference forty years had made: Carbondale had gone from a jumble of low-rent businesses to an average, respectable university town: clean, orderly…and boring.

Yet there was one thing that separated Carbondale from other college towns, and that was size. The population had been 25,000, more or less, for decades, which made it a small town. On the other hand, SIU, to the south, had a maximum enrollment of 24,000 students, which made it the 24th largest university in the country in 1970. Very few huge institutions like SIU are located in isolated small towns, thirteen miles from the closest interstate, in a world of their own.

I leaned against a lamppost and studied the photo of Catherine while squeezing, twisting, and wrenching the CPU in my head in an attempt to release another kilobyte of memory from the past. But I came up with nothing. Any image of the past was overlaid by what was right in front of my eyes in the present. I was the same person, and Carbondale was the same town, but both of us had moved ahead on the timeline and could never return to the ‘70s.

I walked past the Varsity Theater, which was vacant with a FOR SALE sign in the window and newspapers blowing around the doorway. I passed the old Dairy Queen, which was dark except for the big ice cream cone on the roof with its bright little lights. I continued south until I reached an old house that had been converted into a bar back in 1971. Redwood stain was peeling off the former 1910 American Tap, rocks were missing from the cement wall enclosing the beer garden, and FOR SALE signs decorated both front windows. American Tap looked like an old man who had lost his lower front teeth.

But, oddly, a pipe with a curved stem was smoldering in an ashtray on a table in the window. The aroma of the burning tobacco seemed to come from far away. I felt as if my body was in the 21st century, but my sense of smell was somewhere else.

I followed the giant Saluki paw prints to the entrance of Southern Illinois University Carbondale and stepped on campus for the first time in twenty years. A light rain fell from the low clouds making the original one-square-block campus look like it had been built in a vast cavern. Wheeler Hall, with its ghastly blood-red brick, rose behind a gothic wrought iron fence, and in front of Davies Gymnasium, the old girls’ gym, a little boy stood holding an umbrella over a little girl.

Still there!

Paul and Virginia had been placidly standing on the island of a small fountain for more than a century, but tonight, the bronze faces of the two children looked cold and emotionless. I walked to the west, beyond the dismal statue, past the bust of a frowning Delyte Morris—placed where the halls of Old Main used to cross—and past the mausoleum-like Shryock Auditorium to the location of the brutal, concrete Faner Hall.

But Faner wasn’t there. I edged my way closer, and my knee bumped with a crack into a giant reel of wire. As I rubbed the bruise, I looked around and saw stacks of pipe and wire mesh, work trucks, and wooden planks lying in mud, bordered by deep trenches. I guessed a new building was going up, but where was Faner? The thing had been started in 1970 and finished in 1975, after being expanded to include classroom space that had been lost when Old Main was torched. Faner had been longer than the Titanic.

Maybe they tore it down, but why?

Suddenly, from the east, I heard shouts and dozens of feet running towards me from the direction of the overpass that stretched across Highway 51. It sounded like a live broadcast of a riot from a distant a.m. radio station, fading in and out.

My comfortable alma mater was starting to creep me out. The heebie-jeebies began buzzing in my chest as I quickly sought refuge in Thompson Woods, behind where Faner should have been. The woods were reeking with the odors of wet moss, leaves, wood, pot, tear gas, fear, and sweat. As I wandered in darkness, branches seemed to deliberately bar my way along the slick asphalt paths, and slippery leaves muffled my footsteps. Many of the trees were lying on the ground; others were split or missing limbs. The woods looked ghastly.

I broke out of the trees and into a swirling fog behind the Agriculture Building. A siren sounded in the distance, and as it got closer, the pitch lowered, but the volume increased to an ear-splitting scream, and an SIU police car careened into view. It looked as if it was going to miss the curve and crash into the trees ahead—but it faded away. And it didn’t drive off into the distance, either. No, it faded into invisibility, and I felt the physical sensation of fading along with it, though I was standing rigid with fear at the crosswalk.

Oh, Jesus.

I was hallucinating. Yet my mind was as lucid as a diamond. I reached in my pocket for the pill container and threw it into the street, where it broke open, and all of the colored pills bounced into the mist. By now, my head was congested, my ears were filled with fluid, and all I wanted to do was turn around, walk back to the train station, and return to Chicago. But I knew what I would face on the return trip: a riot, the ghost of brutal Faner Hall, pensive Paul and Virginia, and that pipe in the ashtray in the window of the American Tap.

I crossed the street and walked into the woods around Campus Lake toward a picnic shelter I remembered. As I got closer to the shelter, I saw a woman in a long dress lying on her back on one of the picnic tables, but her form dissolved into a shadow as I walked past. Beyond the shelter, I spotted the geometric roof of the campus dock, trudged my way to it, and stood at the flagpole in front of the boat shelter while I wound my pocket watch. It was 6:34

I didn’t care whether it was day or night, because now I was entering the time frame where my body had finished metabolizing the drugs and alcohol, leaving only the miserable dregs of aches, pains, confusion and profound depression. As I clung to the flagpole, I felt as if I were rushing toward the lake.

I inhaled the muggy air, and those little chemical gremlins in my nervous system polluted it with such profound melancholy that when I exhaled, my face was inundated in a miasma of gloom. My head was filled with boiling oil that splashed against the back of my eyes every time my heart pounded. The fulminating oil emptied into my throat, ripped down my esophagus, and hit my stomach with a splash of corrosive acid. I gagged, but the corrosion only got so far as my throat, and I started coughing and hacking phlegm. My right rotator cuff was attached to my shoulder with a nail, and down below, my hips and flat feet throbbed in agony. But my eyes hurt most of all: that cottony silver light forced the corrosive oil into the backs of them, until everything I saw was tinged with red. I tried to squint in an attempt to cut the glare, but my eyelids fluttered involuntarily and were threatening to close. The fog shifted a little, briefly revealing the Thompson Point residence halls.

The dorms looked like how I felt: washed out, colorless, joyless. The engineering buildings behind me were mere phantoms in the fog, and the trees in the woods looked as if they were sketched in pen and ink against the swirling gray mist, their reflections etched in water the color of gun metal. Many of the trees were broken and jagged, lying half in the water near the dock and across the lake on Thompson Point.

My God, there is absolutely no color to anything!

A cold, gray drizzle swirled around me, and I felt the gray of the ground pass through the soles of my shoes and up into my head until my feelings turned dark gray. Boiling oil in the rotator cuff, boiling oil in the feet, the hands, and the neck. Boiling oil in the cough.

This was worst day of my pallid 58-year-long life.

The police car I’d seen earlier came rushing back from the opposite direction on Lincoln Drive, and screeched to a halt. The big, boxy cruiser looked like it had been built forty years ago, but it appeared to be in mint condition. I could see the shadow of the policeman behind the wheel reach down and turn on the siren. The noise sounded as if the damned thing was going off inside my damned head.

The siren blew for at least a minute—60 seconds of audio spikes stabbing my ears. When I turned my head away from the siren, the broken black-and-white trees started rushing past me, and I felt as if I was flying a jet fighter at Mach 1 through the woods.

And that did it.

With catastrophic finality, the broken woods, Tammy, Testing Unlimited!, Bob, my trailer, the vodka, the pills and the gremlins came down on me like a piano and pushed me to my knees so forcefully that indentations were cast in the sod.

I was kneeling next to a rack of canoes with my hands over my ears when the siren stopped. I crumpled to the ground, rolled under the canoes, and passed out.

I was awakened by the mechanical pencil digging into my chest; the soldier on the train must have slipped it in my shirt pocket while I slept. As I rolled out from under the canoes, I was blinded by a bright morning sun reflecting off the lake. I stood up slowly, and was surprised at how I felt, considering the previous night’s bender. I had no headache, no nausea; the minor pains in my feet and back were gone, and so was the chronic ache in my rotator cuff. My eyesight had sharpened, so that I noticed the individual leaves on the Kodachrome green trees. The light blue roof of the boathouse pleasantly complimented the azure sky shimmering in the blue water of the lake. My sense of smell had intensified as well, so I felt awash in pleasant odors: blooming flowers, damp grass, and water gently lapping over the mud near the shore. I could hear the chirp of the crickets, which sounded higher pitched and more musical than they used to. The temperature must have been in the upper 70’s—not too hot, not to cold—and I felt all of these sensations with a passion that I scarcely remembered.

But what happened to fall?

It also seemed that the trees, dock, grass and lake were slightly out of place. Either that or I was.

As I walked over to a picnic table in front of the dock shelter, a bright green grasshopper jumped past me, and I felt as if I weighed only fifty pounds. Past the flagpole, the redwood trim on the Thompson Point residence halls glowed in the sun. But there was something off kilter with TP as well. It was there, right in plain sight, but it took a minute or so for me to realize that the trees around the buildings had been repaired: there were no broken branches, none of the trees were laying in the water, and none of them were split, yet they were shorter than they should have been considering that The Point was fifty years old.

I started a fast walk through the trees near the dock and was soon striding on the path along the edge of the lake, past the picnic shelter with its geodesic dome—which was white. Last night it had been brown. I felt the gremlins clustering at the base of my spine, waiting for one more weird revelation to start their attack. So I rationalized that maybe I’d been so messed up on drugs the night before that I couldn’t tell brown from white. I quickened my pace, and walked over a little wire and wood bridge that crossed a small rivulet behind a residence hall. My senses were high, probing everywhere as I reached the sidewalk between the dorm and the Lentz Hall commons unit—which didn’t look new, but it didn’t look half a century old, either.

Just leaving Lentz was a familiar figure of a girl—familiar as an old statue, even though it’s been decades since you last saw it. Her honey blond hair was down to her waist, and an apricot shift with big flowers clung to her immature figure, revealing skinny legs with a soft blond down glistening in the sun. The figure waived at me.

“Hey, Peter!” she yelled.

The girl was not so much walking as gliding down the sidewalk with a deportment that indicated that as far as she was concerned, anything that was going on in the world at this moment was about as okay as it could be, and that the moon, the stars, and all of the planets were in their proper order, as her horoscope for the day revealed.

When the girl was 50 feet from me, her vaguely familiar figure became chillingly real. It looked like Marta, the woman who had sent me the letters that past summer.

But that’s impossible!

The girl was wearing rose-colored sunglasses and a big hat that threatened to flop over her face. As unreal as it was, I felt as if I were the only person on the planet. And when she got within five feet of me, it was as if I’d been pulled into a bubble of infinite wellbeing. A strong scent of saffron incense clung to her clothes.

“Peter, how are you?” she asked in a way that would imply that I was the most important person in the world, and meeting me was the single most important event in her life. Furthermore, the “are” carried an additional connotation: that regardless of how I responded or how I felt, everything was indeed okay with me.

“Are, are you…you look like…Marta?”

“Yes, I’m Marta!” she chirped proudly.

“What…but you look... what brings you here?”

The girl gave me a sideways look. “You mean right now?”

“Yes, right now!”

“I came to check the mail.”

“What!? I mean what are you doing on this campus?”

The girl looked at me as if I were nuts.

“Going to school, just like you… and, I’m late for class.” She looked serious for just a moment.

“I’m not going to school! Now come on, what are you doing here?”

I was terrified. She cocked her head, as if appraising my mood.

“OK…you caught me...” Marta confessed. “I’m not really going to college. I’m actually from the planet Neptune. We’re here to study you earthlings. And might I say you dudes are really weird…particularly you...” She laughed. “Peter, you need to loosen up, man!”

With a giggle and a wave, Marta started walking toward the Agriculture Building.

“See you at lunch,” she said over her shoulder.

This can’t be!

Even though her hat and sunglasses had covered most of her face, it looked like Marta hadn’t aged a day since I had last seen her, nearly four decades ago!

As I stared in shock at the girl’s retreating figure, I noticed old, boxy cars passing behind her along Lincoln Drive. I snapped my head around, and saw that old, boxy cars were parked in the lot near Lentz and along Point Drive as well. I ran up the drive, and found vehicles that I hadn’t seen in such good condition for years: a 1970 Impala, a 1966 Fury, a 1965 Mustang. And every one of them had Illinois license plates dated 1971.

Suddenly the Point exploded with students. Many wore Tshirts; others sported dress shirts with all of the buttons fastened or none of the buttons fastened. There were Army field jackets, denim jackets, and an occasional sport coat. The kids wore corduroy trousers or bell bottom jeans cinched with big, wide belts. And it was all unisex; there were no skirts. The students carried their books at their sides, or wore Army surplus backpacks. Their hair was long and styled in bangs, or split down the middle so that it cascaded down either side of the face.

Several of these children looked vaguely familiar.

My eyes frantically snapped from the students to the cars, to the cafeteria, to the trees and lake—looking for anything that would tell me I was still in the 21st Century.

I reached into my trousers for the pocket watch, but it was gone, and in its place was a chain with the SIU crest attached to it, along with a single key with a sticker displaying the number 108. I was standing in front of a three-story brick and concrete building in all of its mid-20th century glory, with brushed steel letters on the side wall that spelled BAILEY HALL. The redwood slats over the casement windows looked like they had been freshly stained, and glass bricks made the stairwell windows shine in the sun. This was home during my sophomore year at SIU.

I looked neither left nor right, because I was afraid I might see anything from a charging rhinoceros to Richard Nixon. I walked up to the entrance and tried the key…and the door opened. It felt as if the SIU police were about to come down on me at any minute as I ducked furtively inside a hazily familiar hall. In a trance, I walked up to 108, stuck the key in the door, gingerly pushed it open, and was enveloped in the smell of stale tobacco and whiskey. The front half of the room was neat as a pin: the bed was made and all of the books were meticulously lined up on a shelf at the bottom of a blond wood desk. Nearby was a coffee pot and a hotplate, sitting on top of a log standing on its end. As I passed the mirror above the sink, I saw the reflection of a skinny student, and turned around to address the kid, but there was no one there. I turned back to the mirror and saw the reflection of the kid again. I whirled around: there was no one else in the room. I snapped back to the mirror, and facing me was that kid with an agitated expression on his face. He looked the way I felt, except he was fifty pounds lighter and almost forty years younger and wore this ridiculous mustache and…

His eyes widened like saucers. I jerked away from the mirror as if I had seen a ghost, and faced the window overlooking Point Drive. Below it was another blond wood desk, buried in books and papers. Against the wall and facing the sink was an unmade bed with a distantly familiar dark red bedspread that I had forgotten about long ago. And next to it was a nightstand with a fake-walnut-covered clock radio, just like the one that had been stolen from me at a youth hostel I had stayed at in San Diego during a drunken binge in 1981, when I was homeless.

My mind started spinning with the realization that I was reliving in rich detail what had been only minutes ago an indistinct memory. If all of this was a hallucination, I was in deep trouble, and if it wasn’t, I was in even deeper trouble. I gingerly stepped over to the mirror and risked another quick glance at the kid, followed by a longer glance, and yet another, and still another, until I was staring at him. What I saw was not just the image of a 20-year-old youth.

Hell….what’s here for me? College again? No! Everything is in the future. The trailer, marriage, Testing Unlimited… No! Nothing’s in the future! I have nothing in the past and nothing in the future!

I lost my equilibrium and fell into the chair, in front of my desk, and stared down at an open book to stop the spinning. The first line I saw was: Nervous people must ruthlessly separate opinion from facts in their daily lives, because—good or bad—only facts can be relied upon.

I looked at the table of contents. Taming the Agitated Mind: A Handbook for Nervous People, by Robert Von Reichmann, MD.

I sat down and started reading, with the book clenched in my hands in a death grip. My concentration was desperately intense. I’d do anything to avoid looking at or thinking about what I was doing in my old dorm room, in my young body, governed by a 58-year-old, burned-out brain in the year 1971.

Chapter 4

I fell asleep at “my” desk, slumped over the Von Reichmann book, when something loud, harsh, and jangling awakened me with a jerk. I hadn’t heard the ring of an old rotary telephone for years. I jumped up with incredible speed, overturned the chair, and reached the receiver of the wall phone just as the clattering of the chair against the floor died away. As I lifted the receiver, I thought, Where the hell am I? But by the time I got the instrument to my ear, I realized that I was back at 108 Bailey Hall, Thompson Point, Southern Illinois University at Carbondale.

“Huh-Hello!” I said.

“Darling!”

I almost didn’t recognize her voice.

“Tammy? Is that you!?…”

“Of course it’s me. Are you expecting some other girl to call?”

She sounded so young, so intense, but without the strident overtones that later flawed her perfect voice. It was as if the miserable four-year marriage had never happened—which it hadn’t, not yet. I felt a burst of desire that was quickly overlaid by anxiety as I became fully awake.

“Hello? Hello? Peter, are you still there? Peter…”

“Yes I’m still here, but I wish I weren’t…”

“What do you mean?”

“I mean, I mean, that I don’t belong here.” My eyes were moving around the dorm room as I visualized Tammy at the other end of the line, probably in Urbana in her dorm room, lying on her bed, maybe in her underwear, with her red hair and perfect figure.

“What’s wrong, Peter? Is there something wrong? Tell me.”

“I mean…” I didn’t know what I meant, other than feeling suddenly nauseous and lightheaded.

“What do you mean, Pete? You’ve pulled this before. You just stop communicating. You’ve got to tell me what’s going on.”

I was looking at the wall, at shadows of the little holes. The green cinder block should have been blurred into gray obscurity by time, but instead was as sharp and colorful as a Kodachrome slide. I sat heavily on my red bedspread in a haze of wooziness. Soon I became aware of plaintive chirping coming out of the receiver now hanging from its cord.

“Peter, Peter! Are you there? What’s going on?”

I hung up.

I got up and caught a glimpse of my 20-year-old self in the mirror, and searched deep in his eyes for any signs of a 58-year-old man in there, but all I saw was the face that was on my student ID which I had found in my a dirty wallet located in my side pocket. Also in it were four dollars, a Park Forest library card, a cardboard Illinois driver’s license, and several scraps of paper with notes scrawled on them. I went into the bathroom and threw up. When I came back out, I opened the medicine cabinet, found a glass bottle of aspirin, and took two of them while sitting on the edge of my bed. I stared out the window at the big, boxy cars of the ‘70s passing by on Lincoln Drive.

Right now I’m involved with Tammy and that’s going to lead to a miserable marriage. My parents live in a Chicago suburb and are the same age as I am, or was. My younger brother—who was in his early fifties the last time I saw him—is now a high school kid. My neighborhood in Park Forest, the next-door neighbors, Rich East High School, WRHS, the high school radio station, my childhood friends…are all right there for me, three hundred miles to the north…and almost forty years in the past. If I saw them what would I think? What would they think? Would it change the future? Am I changing the future now? And what about Catherine? What’s my relationship with her now? I don’t remember!

I was frantically trying to push past a huge, implacable block of time that separated me from my memories of 1971, but after 38 years, there weren’t many memories left.

In the midst of this confusion, I heard a key scratching around in the hall door lock behind me. From the reflection in the window, I saw the door slowly open, and I gingerly turned around, afraid of what I was about to see. In shambled a short, muscular, teenager with swarthy, rounded features who wore a dull red and brown T-shirt, jeans, white socks and black canvas tennis shoes. His brown hair was considered short for the ‘70s, and he could have been mistaken for either a young gym coach or a hood.