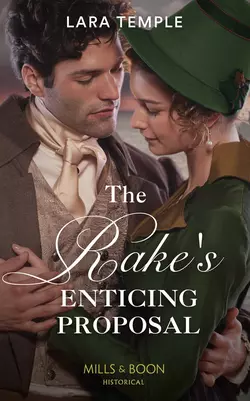

The Rake′s Enticing Proposal

The Rake's Enticing Proposal

Lara Temple

The rake has a proposition… Will she accept? Part of The Sinful Sinclairs. When globe-trotting Charles Sinclair arrives at Huxley Manor to sort out his late cousin’s affairs, he meets practical Eleanor Walsh. He can’t shake the feeling that behind her responsibility to clear her family’s debt, Eleanor longs to escape her staid life. Chase can offer her an exciting adventure in Egypt… But that all depends on her response to his shocking proposal!

The rake has a proposition...

Will she accept?

Part of The Sinful Sinclairs: When globe-trotting Charles Sinclair arrives at Huxley Manor to sort out his late cousin’s affairs, he meets practical Eleanor Walsh. He can’t shake the feeling that behind her responsibility to clear her family’s debt, Eleanor longs to escape her staid life. Chase can offer her an exciting adventure in Egypt... But that all depends on her response to his shocking proposal!

LARA TEMPLE was three years old when she begged her mother to take the dictation of her first adventure story. Since then she has led a double life—by day she is a high-tech investment professional, who has lived and worked on three continents, but when darkness falls she loses herself in history and romance…at least on the page. Luckily her husband and two beautiful and very energetic children help her weave it all together.

Also by Lara Temple (#ue50fdf6f-7dac-5c95-9e86-65b699c50dce)

The Duke’s Unexpected Bride

Unlaced by the Highland Duke

Wild Lords and Innocent Ladies miniseries

Lord Hunter’s Cinderella Heiress

Lord Ravenscar’s Inconvenient Betrothal

Lord Stanton’s Last Mistress

The Sinful Sinclairs miniseries

The Earl’s Irresistible Challenge

The Rake’s Enticing Proposal

Discover more at millsandboon.co.uk (http://www.millsandboon.co.uk).

The Rake’s Enticing Proposal

Lara Temple

www.millsandboon.co.uk (http://www.millsandboon.co.uk)

ISBN: 978-1-474-08917-3

THE RAKE’S ENTICING PROPOSAL

© 2019 Ilana Treston

Published in Great Britain 2019

by Mills & Boon, an imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers 1 London Bridge Street, London, SE1 9GF

All rights reserved including the right of reproduction in whole or in part in any form. This edition is published by arrangement with Harlequin Books S.A.

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, locations and incidents are purely fictional and bear no relationship to any real life individuals, living or dead, or to any actual places, business establishments, locations, events or incidents. Any resemblance is entirely coincidental.

By payment of the required fees, you are granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right and licence to download and install this e-book on your personal computer, tablet computer, smart phone or other electronic reading device only (each a “Licensed Device”) and to access, display and read the text of this e-book on-screen on your Licensed Device. Except to the extent any of these acts shall be permitted pursuant to any mandatory provision of applicable law but no further, no part of this e-book or its text or images may be reproduced, transmitted, distributed, translated, converted or adapted for use on another file format, communicated to the public, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of publisher.

® and ™ are trademarks owned and used by the trademark owner and/or its licensee. Trademarks marked with ® are registered with the United Kingdom Patent Office and/or the Office for Harmonisation in the Internal Market and in other countries.

www.millsandboon.co.uk (http://www.millsandboon.co.uk)

Note to Readers (#ue50fdf6f-7dac-5c95-9e86-65b699c50dce)

This ebook contains the following accessibility features which, if supported by your device, can be accessed via your ereader/accessibility settings:

Change of font size and line height

Change of background and font colours

Change of font

Change justification

Text to speech

This one is for my soul sisters.

Armed with tea or wine or cake—

they sweep in and rescue me from my worst selves and let me do the same for them.

Wherever we are around the globe—

the sisterhood holds firm.

Contents

Cover (#u68cd0664-f59f-5193-9e55-44facd65037d)

Back Cover Text (#u47591e71-1df7-5ee2-9bb4-d7f4da589360)

About the Author (#uf89aa6ef-2f53-565c-827e-b23d25f4eb88)

Booklist (#uddb1d2b7-9693-5edb-9146-93face13af95)

Title Page (#u28b7e064-8ef0-5acf-b6c1-cfef55d6e20c)

Copyright (#ub802b78e-639b-52f7-999c-3fc12044b392)

Note to Readers

Dedication (#u4856bbd9-aaf1-5bdc-b4e6-9f37592492bd)

Chapter One (#u41a6d332-bd93-581f-945a-70a9c3bc9f41)

Chapter Two (#u3aa531a3-00a4-5e41-aaf4-6384da10fb79)

Chapter Three (#uc04f8e69-44af-51c3-89d8-b920b84f3dbe)

Chapter Four (#ufb95a3b9-6daa-5374-a7b5-12869004b4de)

Chapter Five (#uc294a318-e187-51c3-8c08-1ad96f11a9d2)

Chapter Six (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Seven (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Eight (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Nine (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Ten (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Eleven (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twelve (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Fourteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Fifteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Sixteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Seventeen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Eighteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Nineteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-One (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Two (#litres_trial_promo)

Epilogue (#litres_trial_promo)

Extract (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter One (#ue50fdf6f-7dac-5c95-9e86-65b699c50dce)

‘I have one last, but very important, quest for you, Chase...’

Chase drew Brutus to a halt at the foot of Huxley’s Folly.

The last time he’d seen his cousin, he’d stood precisely there in the arched doorway of the stone tower, his wispy grey hair weaving in the breeze like an underwater plant.

The last time he’d seen him and the first and last time Huxley had ever expressed any sentiment regarding Chase’s chosen occupation.

‘I do hope what you do for Oswald doesn’t place you in too much peril, Chase. Tessa would be very upset if you joined her too soon.’

Huxley always referred to Chase’s mother as if her death was merely a temporary absence. It was one of the reasons Chase found visiting Huxley a strain, but that was no excuse for neglecting him these past couple of years, no matter how busy Oswald kept him.

‘It’s my fault, Brutus.’ He stroked the horse’s thick black neck. ‘I should have visited more often. Too late now.’

Brutus huffed, twin bursts of steam foaming into the chilly air.

Chase sighed and swung out of the saddle. Coming to Huxley Manor always stretched his patience, but without Huxley himself his stay would be purgatorial. Nothing wrong with postponing it a little longer with a visit to the ramshackle Folly tower. Every time he came it looked a little more stunted, but as children he and Lucas and Sam fantasised that it was populated with ogres, magical beasts and escaped princesses.

He approached the wall where Huxley kept a key behind a loose brick, when he noticed the door was slightly open. He frowned and slipped inside, a decade of working as emissary for his uncle at the Foreign Office coming into play even though he knew there was probably no need. Being sent to smooth out some of the less mentionable kinks in relations with Britain’s allies meant one collected as many enemies as friends. Wariness had the advantage of increasing longevity, but it also flared up at inappropriate moments, and this was probably just such a case.

No doubt whoever was in the tower was merely his cousin, Henry, the new Baron Huxley, or Huxley’s trusted secretary, Mallory, Chase told himself as he climbed the stairs silently.

It was neither.

For a moment as he stood in the doorway of the first floor of the tower he wondered if he’d conjured one of their old tales into being—the Princess locked away and pining for her Prince.

His mouth quirked in amusement at his descent into fancy as he took in the details of her attire. Definitely not a princess.

She was seated at Huxley’s desk, which was positioned to provide a view from the arched window, so she was facing away and all he could see was the curve of her cheek and tawny-brown hair gathered into a tightly coiled bun exposing the fragile line of her nape and a very drab-coloured pelisse with no visible ornamentation.

She was leaning over some papers on the desk with evident concentration and the opening words in Huxley’s cryptic letter forced their way back into his mind.

There is something I have but recently uncovered that I must discuss with you. I think it will be best you not share this revelation with anyone, except perhaps with Lucas, as it can do more harm than good to those I care about most...

Huxley’s letter, dated almost a month ago, awaited him on his return from St Petersburg two days ago, as well as a message from his man of business with news of Huxley’s demise and his last will and testament.

Chase hadn’t the slightest idea what Huxley was referring to, but he had every intention of finding out. Through the centuries the Sinclair name became synonymous with scandal, but now Lucas was married and Sam widowed Chase had every intention of keeping his family name out of the muck and mire it so loved wallowing in. If Huxley had uncovered something damaging and had it here at the Manor, Chase intended to destroy it as swiftly and quietly as possible.

Therefore, the sight of a strange woman seated at Huxley’s desk and looking through his papers was not the most welcome vision at the moment.

As if sensing his tension, she straightened, like a rabbit pricking its ears, then turned and rose in one motion, sending the chair scraping backwards. For the briefest moment her eyes reflected fear, but then she did something quite different from most women he knew. Like a storm moving backwards she gathered all expression inwards and went utterly flat. It was like watching liquid drain out of a crack in a clay vessel, leaving it empty and dull.

They inspected each other in silence. With all trace of emotion gone from her face she was as unremarkable as her clothes—her height was perhaps a little on the tall side of middling, but what figure he could distinguish beneath her shapeless pelisse was too slim to fit society’s vision of proper proportions and the pelisse’s hue, a worn dun colour that hovered between grey and brown and was an offence to both, gave a sallow cast to her pale skin. Only her eyes were in any way remarkable—large and a deep honey-brown. Even devoid of expression they held a jewel-like glitter which made him think of a tigress watching its prey from the shadows.

‘Who are you? What are you doing here?’ she demanded, her voice surprisingly deep and husky for someone so slight. That, too, was unusual. Similar demands were fired at him by friend and foe since he’d joined the army and not nearly as imperiously. Predictably he felt his hackles rise along with his suspicions.

‘I could ask the same question. Are you another of Lady Ermintrude’s nieces? I thought I had met the lot.’

She moved along the desk as he approached, putting it between them, but he concentrated on what lay on top. Piled high with papers and books, it was much more chaotic than he remembered and he wondered if his cousin or the young woman were the cause.

He glanced at the slip of paper she’d inspected with such concentration. It was a caricature of a camel inspecting a pot of tea through a quizzing glass, grey hair swept back in an impressive cockade over a patrician brow. The resemblance to his cousin’s antiquarian friend Phillip ‘Poppy’ Carmichael was impressive and a fraction of Chase’s tension eased, but only a fraction. This particular scrap of paper might have nothing to do with Huxley’s message, but any of the other papers here might hold the key to understanding it.

He returned his attention to the woman. She was younger than his first impression of her—perhaps in her mid-twenties. Her hand rested on a stack of books at the edge of the desk and she looked like a countrified statue of learning, or a schoolmistress waiting for her class to settle. She did have rather the look of a schoolmistress—proper, erect, a little impatient, as if he was not merely a slow pupil, but purposely recalcitrant. With her chin raised, her eyes had a faintly exotic slant, something an artist would attempt if he wanted to depict a goddess to be wary of.

And he was. If there was one thing he’d learned was that appearances could be and often were deceptive. So he leaned his hip on the desk, crossed his arms and gave her his best smile.

‘It is impolite to read another person’s correspondence. Even if he is dead.’

‘I didn’t mean...’ The blank façade cracked a little, but the flash of contrition was gone as quickly as it appeared and she raised her chin, her mouth flattening into a stubborn line that compressed the appealing fullness of her lower lip. ‘As I am betrothed to Lord Huxley I have every right to be here. Can you say the same?’

‘Unfortunately not. He wouldn’t have me.’

She gave a little gasp of laughter and it transformed her face as much as that brief flash of contrition—her eyes slanting further, her cheeks rounding and her mouth relaxing from its prim horizontal line. Then something else followed her amusement—recognition.

‘I should have guessed immediately. You must be one of the Sinclairs, yes? Henry said one of you would likely come to Huxley Manor because of Lord Huxley’s will.’

‘One of us. You make us sound like a travelling troupe of theatrical performers.’

‘Much more entertaining according to Miss Fenella.’

‘My cousin Fen was always prone to gossip. You can stop edging towards the door; I have no intention of pouncing on Henry’s freshly minted betrothed, whatever the requirements of my reputation. I am surprised, though. I had not heard he was engaged.’

‘We...we are keeping it secret at the moment because of the bereavement. Only Lady Ermintrude and the Misses Ames know. I should not have told you, either, but I assume Henry will have to tell you if you are staying at the Manor. Please do not mention it to anyone, though. It would be improper...while he is in mourning...’

Unlike her previous decisive tones, her voice faded into a breathy ramble and the defiance in her honey-warm eyes into bruised confusion. Perhaps she was hurt by Henry’s refusal to acknowledge her position?

‘Of course the proprieties must be observed,’ he soothed. ‘But that still does not explain why you are here alone at the Folly, reading Cousin Huxley’s papers. Shouldn’t you be at the Manor flirting with Henry or paying court to Lady Ermintrude along with everyone else?’

‘Henry is fully occupied with his land steward and Lady Ermintrude and Miss Ames and Miss Fenella are busy with preparations for the annual meeting of the Women’s Society, which apparently trumps all mourning proprieties. Since my embroidery skills are on the wrong side of atrocious, I am persona non grata and had to find some other way of passing the time.’

‘I imagine your embroidery skills are the least cause of your lack of popularity among the womenfolk of the manor. However, that, too, doesn’t explain why you are here.’

‘Henry showed me the hidden key when we explored yesterday. I merely wanted some place quiet to read.’

‘To read other people’s letters,’ he said softly. She flushed, but didn’t answer, and he felt a twinge of contrition himself. He was becoming too much like Oswald—ready to suspect everyone of everything. She was no doubt bored of being slighted and indulging in a sulk—in which case he was being unfairly harsh.

‘Is Lady Ermintrude making your life difficult? I am not surprised. She always intended that my cousin would marry one of her nieces.’

‘Yes, she made that only too clear. I thought Henry was exaggerating, but...’ She stopped and cleared her throat, throwing him a suspicious look, as if realising she was being far too frank with a stranger. He smiled and tried another tack.

‘You still should not come to the Folly unaccompanied. The tower itself is solid enough, but all these boxes and stacks could prove hazardous. It always looked as though a whirlwind has passed through, but it appears to have reached new levels of chaos since I was last here. Is his study in the east wing as bad?’

‘Henry did not take me there. He said the will specified all the contents of the east wing went to you and your siblings so he did not wish to meddle. He only showed me the Folly because it is such a peculiarity and I was curious to see inside. Perhaps I should not have insisted.’

Chase wondered at his growing sense of discomfort. There was something about this young woman that was...off. It put him at a disadvantage, which was precisely where he did not like being put.

‘He was always a biddable fellow.’

‘Henry is polite and considerate. That is very different from being biddable.’

‘You are quite right, it is. I apologise for maligning him.’

She snorted, her opinion of his apology all too clear. The hesitation and vulnerability were gone once more and the watchful glitter was back. She looked too soft to be so hard, another discordant note. Chase considered moving so she could access the stairway, but remained where he was.

‘Excuse me, Mr Sinclair.’ She looked up and he saw the schoolmistress again—in the light from the window the honey in her eyes was sparked with tiny shards of green just around the iris, like jade slivers dipped in gold.

‘For what?’ he asked, not budging.

‘I was not begging your pardon,’ she replied, spacing out the words as if to someone hard of hearing. ‘I was asking you to stand aside so I may pass.’

‘In a moment. Congratulations on your betrothal, by the way. Where did you meet Henry?’

She eyed the space between him and the doorway, clearly calculating her odds of slipping by.

‘We are neighbours in Nettleton.’

‘How charming. I didn’t know Nettleton harboured such hidden gems. How are you enjoying Huxley?’

‘We only arrived two days ago.’

‘A diplomatic but revealing answer. Not at all, then.’

She laughed and the tiny lines at the corners of her eyes hinted she smiled easily, which surprised him.

‘Judging by Lady Ermintrude’s comments about the Sinclairs, my welcome may be warmer than yours.’

‘You shouldn’t say that with such relish.’

‘True. It is very uncharitable of me. I hope Lady Ermintrude welcomes you with open arms, Mr Sinclair.’

‘That sounds a far worse prospect. May I ask how you would benefit from that unlikely scenario?’

‘Anything that puts a smile on her face would be welcome.’

‘Having never seen her smile, I cannot judge if it would be an improvement, but when that unlikely event occurs I doubt I will have been its cause.’

‘Was she always like that? Or is her stony façade a concession to mourning her brother-in-law?’

‘Façade implies something hidden, but after years of observation I can safely say her interior is completely consistent with her exterior. There is no inner sanctum, complete with crackling fireplace and a good book, so do not waste your time searching for it. Ermy is as devoid of emotion as she is of humour.’

‘That is what Henry says, but one cannot help wondering... Everyone has redeeming features. She appears devoted to her nieces.’

‘Yes, poor Dru and Fen. They would have fared better without it. Though devotion isn’t quite the word.’

‘What is, then?’

He opened his mouth to answer and paused, surprised by his willingness to satisfy her curiosity. He was not usually so revealing to a complete stranger.

‘You do know that in Aunt Ermy’s small universe, Henry marrying one of her nieces was as obvious as the sun rising in the east or two plus two equals four.’

‘My brother would point out that while the latter is indeed a given, there is nothing to say the sun must always rise in the east.’

‘Good God, I hope you didn’t make that Humean point to Aunt Ermy. Is that why you have banished yourself to the Folly?’

Her smile flashed again and was tucked away.

‘I had best return now. Good day, sir.’

She took a step forward, but stopped once more as he did not move out of the way. It was childish to be toying with her, but he was curious about Henry’s bride-to-be. His memories of his awkward but good-natured cousin did not tally well with this intelligent and curious specimen of femininity.

‘I must return to the Manor, sir.’

‘In a moment. Since there is no one here to help us follow convention, shall we break with it and introduce ourselves? I am Charles Sinclair, though my friends and quite a few of my enemies call me Chase. May I know the name of my cousin-to-be?’

‘Then will you stand aside and allow me to leave?’

He bowed. ‘My word on it.’

She huffed a little, as if considering a snort of disdain.

‘Miss Walsh.’

‘Walsh. Walsh of Nettleton.’ He shouldn’t have spoken aloud. Her eyes widened at his tone and their coolness turned to frost.

She didn’t look anything like the Fergus Walsh he’d once met in London. That man had been a red-haired Celt with charm and a temperament to match. He’d also been a charming wastrel and inveterate gambler who’d frequented all the clubs and gaming hells until bad debts drove him to ever more dissolute establishments. He’d brought his family to the brink of ruin and then compounded his shame by drowning in a ditch outside a gambling hell off the Fleet while inebriated.

Chase had also heard of him from Huxley who’d been bemused by his younger brother’s friendship with the man. Arthur Whelford, father to new Lord Huxley, was a vicar and possessed all the virtues of his calling. But despite these differences the Whelfords and Walshes had been the best of friends. And now the wastrel’s daughter was engaged to the vicar’s son and new Lord Huxley.

‘I shan’t keep you from your betrothed any longer, Miss Walsh. You may run along.’

‘How kind of you, Mr Sinclair.’ Resentment seethed in her deep voice, but as she moved towards the doorway something else caught his attention—a folded slip of paper held in her hand. The world shifted, both his pity and the last remnant of his enjoyment of the absurd little scene draining away in an instant, and he tweaked the letter from her hand.

‘I believe my cousin’s will stipulated that the contents of the Folly are mine and my siblings’, so I suggest you leave this here.’

‘How dare you! Return that to me this instant!’

She reached for the letter and in his surprise he raised it above his head, just as he would when he and Sam squabbled over something as children. And just like Sam, Fergus Walsh’s daughter lunged for it. Her move was so unexpected she almost made it, but just as her fingers grazed the letter he raised it further and she grabbed the lapel of his coat, staggering against him and shoving him back on to the stack of boxes that stood by the stairway.

He should have steadied himself on the wall, but instead he found his other arm around her waist as he toppled backwards. The top boxes tumbled down the stairway in a series of deafening crashes and he abandoned the letter to brace himself against the doorjamb before he followed them into the void. He saw the moment the anger in her eyes transformed to shock and fear as they sank towards the stairs, her hand fisting hard in his coat as if she could still prevent him from falling. The impact against the tumbled boxes and the top step was painful, but nowhere near as painful as their precipitous descent down them might have been.

‘My God, I am so sorry. Are you hurt?’ She was still on him, one hand fisted on his greatcoat, the other splayed against his chest. Her eyes were wide with concern and he could see all the shades of gold and amber and jade that meshed together around the dilated pupils and he had the peculiar sensation he was still sinking, as if the fall hadn’t stopped, just slowed.

‘Are you hurt?’ she demanded again, giving his coat a little tug. Out of the peculiar numbness he noticed her elbow was digging painfully into his abdomen and he forced himself to shake his head. At last the strange sensation ebbed, but now his body woke and instead of reconnoitring and reporting back on the damage, it focused on something completely different. She was sprawled on top of him, astride his thigh, her legs spread and her own thigh tucked so snugly between his if he shifted the slightest bit he...

‘You are hurt,’ she stated, her fist tightening further in his coat, her gaze running over him as if trying to locate his wounds and, though he hadn’t felt a blow, he wondered if perhaps he had after all struck his head on the wall and that accounted for this strange floating feeling.

‘Not hurt. Just winded,’ he croaked and managed a smile and thankfully her brows drew together into a frown.

‘Serves you right! That is my letter. Not Lord Huxley’s.’

She struggled to rise, her thigh dragging against his groin with startling effectiveness and his normally obedient body shocked him by leaping into readiness. Instinctively his arm tightened around her and with a cry she slipped and fell back against him, leaving him doubly winded, her hair a silky cushion under his chin. Perhaps if he had not been so surprised and not a little embarrassed by his body’s perfidy, he might have kept quiet. But instead of helping her as a gentleman should, he kept his arm where it was and succumbed to the urge to turn his head to test the softness of her hair with his lips.

‘Don’t go yet...we’ve just got comfortable,’ he murmured against her hair, absorbing the scent of lilies and something else, sweet and tempting... Vanilla? Her elbow sank even more painfully into the soft flesh under his ribs, but he felt the pain less than he noticed the rest of her anatomy as she wriggled off him and shoved to her feet.

‘Henry is utterly right about you!’

He levered himself into a sitting position and watched as she picked up the letter with a gesture that was a perfect reflection of her scold. She didn’t even glance at him as she stepped over him and stalked down the stairs.

‘And you may tidy up that mess you made.’ Her scold echoed up the stairwell the moment before the slamming of the wooden door sent a whoosh of cold air up towards him. He heard Brutus’s shrill whinny and hauled himself to his feet with a spurt of fear only to hear her voice, faint but all too clear as she admonished his sixteen-hand fiend of a horse.

‘Out of my way, you great lug. You’re as ill mannered as your master!’

Chase inspected the tear in the seat of his buckskins where the shattered box had ripped through the sturdy material. It stung and throbbed and he began laughing.

His brother Lucas would love that he found himself flat on his backside with his head handed to him within minutes of arriving. What a fitting beginning to what was likely to prove a dismal week.

Chapter Two (#ue50fdf6f-7dac-5c95-9e86-65b699c50dce)

‘Ellie, wait.’

Ellie stopped halfway up the stairs, indulging in a string of mental curses. She didn’t wish to speak to anyone in her present state, not even Henry.

‘I’ve escaped the steward and was just about to set off in search of you, Ellie. There is tea in... Good Lord, what happened to you? Have you fallen down a coal chute?’ Henry’s eyes widened as they took in the state of her skirts and the uncharacteristic anger on her face.

‘I must change, Henry.’

‘First come into the parlour and tell me what’s about before the three witches find us. Come, tea and lemon seed cake are just what you need...’ Henry coaxed.

The smile and the concern in his sky-blue eyes were a balm after the look of distaste that had doused the laughter in Mr Sinclair’s grey eyes the moment he realised who her father was.

Though how someone with his reputation had the gall to look down upon a fellow reprobate...

She shouldn’t be surprised—it was the way of the world that even rakes and rascals felt superior to those of their breed foolish enough to sink into debt and disgrace. Apparently the notion of there but for the grace of God go I didn’t occur to the likes of Charles Sinclair. Chase, Indeed! She would like to chase him off with a croquet mallet!

‘You’re looking fierce, Ellie. Is this Lady Ermintrude’s fault?’

‘No. I had an encounter with your cousin,’ she said and he grinned, looking even more angelically boyish.

‘Dru or Fen did this? Over me? Good lord, I wouldn’t have thought they had the pluck!’

‘Not them, you vain popinjay. Your cousin The Right Honourable Charles Sinclair. Though I saw nothing very honourable about him.’

His grin vanished.

‘Oh, lord, is Chase here already? And what the devil do you mean you had an encounter? I’ve heard he’s a devil with the ladies, but...’

‘Henry Giles Whelford!’

‘Sorry, Eleanor. I was funning... Never mind. I thought you were at the Folly escaping Aunt Ermintrude.’

‘I was. He appeared there while I was trying to read Susan’s letter. And he is a hundred times worse than you said.’

‘Is he? I mean...what on earth did he do?’

‘He accused me of stealing! And then he took my letter and when I tried to take it back we almost fell down the stairs.’

‘No! Ellie, are you hurt? Do let me see.’

Her anger fizzled at the concern in her friend’s voice.

‘I’m not hurt, but I never should have allowed you to convince me to masquerade as your betrothed. I knew everything would go wrong.’

‘Hush!’ Henry flapped his hands, glancing at the closed door. ‘You never know when that sneaky Pruitt might be hovering about listening at keyholes. If I am to protect your reputation, the engagement must remain just between us, Lady Ermintrude and her nieces.’

‘I know, but I’ve already blurted it out to Mr Sinclair.’

‘What? Why on earth...?’

‘I don’t know. He looked at me so suspiciously and the words were out before I could think. I warned you I am dreadful at subterfuge. If I had not been so desperate...’

‘We are both desperate, remember?’

‘My problems are slightly more serious than yours,’ she replied sharply. ‘If I cannot find the funds to prevent the banks from foreclosing on Whitworth, Edmund and Susan and Anne and Hugh will lose their home at best and end up in debtors’ prison at worst. I think that is a little more fateful than whether you can withstand Lady Ermintrude’s pressure to wed one of her nieces. I did try to recover my mistake by telling him it was to remain a secret while you were in mourning.’

‘Well, that should be enough—Chase was never one to spill. Matters are a little more complicated here than I thought, but once I untangle the accounts I am certain to find a way to raise the funds to prevent the banks foreclosing on Whitworth. And then in a few weeks you may jilt me and I will mope around, declaring myself inconsolable and determined never to wed and that will put an end to Aunt Ermintrude’s plans to force me into marrying Dru or Fen. By the time she overcomes her scruples I will hopefully have the Manor sufficiently on its feet so I can dispense with her funds.’

‘I still think this is madness, Henry. I don’t know if I shall uphold this masquerade for days, let alone weeks. Besides, the children never had to manage without me...’

‘Well, high time they did. Susan and Edmund wouldn’t thank you for calling them children. Why, Susan is almost on the shelf herself.’

‘Thank you kindly, Henry. I’m well aware of my advancing years.’

‘You’re still a year younger than I so listen to a wise old man—it will come right in the end. I promise. All you must do is be precisely who you are—the indomitable Miss Eleanor Walsh. If you could keep Whitworth afloat for the past five years, beating back bankers and creditors from the doorstep, you can take on one ill-tempered spinster. Well, three of them. You’ve already made grand progress last night, admiring Aunt Ermintrude’s brooch. Now she is convinced you are a scheming golddigger.’

‘I was trying to make polite conversation!’

‘Well, some more of that politeness and she’ll be mighty pleased with me when you jilt me. It’s deuced uncomfortable that Uncle Huxley allowed the estate to become dependent on her funds, but I suspect that was her doing, trying to make herself indispensable. No doubt she wished it was her and not her sister Hattie my poor uncle married.’

‘I feel rather sorry for her...’

‘Well, don’t be. There isn’t a shred of kindness in her.’

‘It was kind of her to take Drusilla and Fenella in when their parents died.’

‘That isn’t kindness. She brought them here like two dolls and treated them just the same. If they weren’t so annoying, I would feel sorry for them. Why, Dru is twenty-three and has never had a true Season even though she is an heiress in her own right. It’s shameful.’

‘There, that is something for you to do. Really, you led me to believe they were much worse than they are. Once I break your heart, I suggest you take your cousins to town and find them husbands.’

‘Fen might enjoy it, but Dru prefers the country. You should have seen her today when she came with me and the steward out to the pastures, the two of them rattling on about sheep and wool and lambing until I was ready to cry. I can’t see her enjoying the brouhaha of London any more than I would.’

‘I think it a good sign Dru made such a gesture of goodwill. You should encourage her to come out with you more often, knowing she will enjoy it more than embroidering with her aunt.’

‘It feels more like a cross between a lecture and a scold than a gesture of goodwill.’

‘Well, she is rather shy...’

‘Shy? Dru? The girl tore strips out of me that time I put frogs in her bed. Had me carry them all the way back to the pond in the dark.’

‘Well, you were a horrid little boy and I would have done the same.’

Henry laughed, his freckled cheeks a little pink, and not for the first time since her arrival at Huxley, Ellie wondered if he was being quite honest with himself. His tales of Huxley Manor over the years led her to expect a household of scheming harpies, but it was clear only Lady Ermintrude merited that title.

She decided to toss one more stone into the well.

‘Once the period of strict mourning is over, you should hold a ball here at the Manor and bring all the landed gentry so she can find a nice country squire. Then settling Fen would be her and her husband’s task.’

‘I don’t fancy playing matchmaker, if you don’t mind. But perhaps I should ask Dru to help with the da—the darling sheep. I might as well derive some benefit from her superior airs. But even if Dru isn’t...well, you know...that doesn’t mean my aunt wouldn’t try to force my hand with her. I told you about that time three years ago when Aunt Ermintrude arranged matters so that we were left stranded in a carriage on the way back from an assembly. If the Philbys had not come along we’d have been long married, believe me. I left the next day before the old witch could try something else. You’re my only defence, Ellie.’

Ellie sighed. She might think Dru rather suited Henry, but she could not argue against his aversion to being coerced into marriage. She knew enough about being coerced into situations not of one’s choosing.

‘It’s only a few weeks, Ellie. In fact, it’s dashed good news Chase has come. My aunt always resented Huxley’s strong ties to the Sinclairs. After his wife passed, he spent much more time with them and their widowed mother in Egypt than he ever spent here and when they did come to visit they always managed to rub her the wrong way. Perhaps you could flirt with him and then...’

‘No!’

‘Oh, very well. It was only a thought.’

‘A typically noddy-headed one, Henry! Though if I were at all sensible I should encourage anything that will hasten your plan. I couldn’t bear it if Edmund lost everything because I failed. I had it all planned, you know. All we needed were a few more years of decent harvests and for nothing terrible to go wrong with the livestock or the tenants, then poor Mr Phillips fell ill so of course we could not press for rents and then there was the drought last year and...’

Her voice cracked as she recalled the last summons to meet with Mr Soames at the bank. He’d been regretful, but very clear. They’d shown far too much leniency already. Problems of their own... Pressure from the board... Fiscal duty... Three months...

Three months...

Her head and stomach had reeled and halfway back on that endless walk from town she’d hurried into the bushes and been viciously ill. She’d only told Henry because he’d been waiting at Whitworth to tell her of Huxley’s passing and somehow the truth tumbled out of her. So when he said it was fate and proposed this mad plan she’d agreed. For once, just for once, she wanted someone to swoop in and save her, like a sorcerer in a story.

She’d forgotten that most swooping-in sorcerers tended to exact a hefty price for their services.

But three months...

She felt another wave of weariness and fear beat at her embattlements. It was even stronger now that she was away from Whitworth where she didn’t have the constant reminders of her duty. Even coming here felt like a betrayal despite the fact that this was her only hope of saving her family’s home. She didn’t know what to think any longer.

Just that she was so very, very tired. And scared.

‘Oh, God, Henry, I’m so frightened,’ she whispered and the tears began to burn. She would not cry. She hadn’t cried since her mother and baby sister died that horrible day five years ago and she would not begin now.

‘Dash it all, Ellie, don’t come apart at the seams now,’ Henry said, his eyes widening in alarm, but he put his arm around her shoulders, drawing her to him. ‘You’re the indomitable Eleanor Walsh, remember? Nothing is too difficult for you. So buck up, everything will come right in the end. Word of honour. I...’

‘Henry Giles Whelford! I will have none of that in my household!’

They both jerked apart at the command. For such an ancient house, the door hinges were well oiled—neither had noticed the door open. Lady Ermintrude stood flanked by Drusilla and Fenella Ames, their cheeks flaming, and behind them, as out of place as a panther in a litter of kittens, stood the dark and impassive Mr Sinclair.

Ellie’s face flamed in embarrassment and lingering misery, her pulse tumbling forward as it had when he appeared behind her in the Folly. It was not quite fear, more like the sensation of waking in the middle of a vivid dream, her mind struggling to separate fact from fiction. She had an utterly outrageous thought that he was not really there, just a figment of her imagination—that if she blinked he would disappear and all she would see were the three disapproving women.

‘I didn’t...we weren’t...’ Henry stammered, but Lady Ermintrude waved a hand, cutting him off as she turned.

‘Supper is in an hour. Do not be late.’ She sailed away and the cousins trailed in her wake, but Mr Sinclair remained, leaning on the doorjamb. As the silence stretched the absurdly fanciful sensation that he was not quite corporeal faded, but he still looked utterly out of place. He must only have entered because he was still wearing his greatcoat and Ellie noticed his buckskins were as streaked with dust and grime from their fall as her skirts.

Peculiarly, this mundane observation reassured her a little, but when she looked up he smiled and her well-developed inner alarms began pealing once more. Instinctively she donned the supercilious look she reserved for visits from creditors and bank officials, but his smile merely deepened and he turned to Henry.

‘Hello, Henry. You really must train Aunt Ermy to call you by your title now. Hard to establish your authority when she’s calling you Henry Giles.’

Henry stood and tugged at his waistcoat, his face flushed.

‘I don’t need to establish my authority. I’m Lord Huxley now. Why didn’t you send word you were arriving today? Will you be staying here or in town?’

‘Well, that puts me in my place.’

Henry’s stiff look crumbled.

‘Oh, deuce take you, Chase. I hope you are staying here because we need to even the odds.’

‘I hadn’t realised I was being enlisted into battle again. Aren’t you planning to introduce me to the other troops, by the way?’

The mocking edge was gone from his smile and Ellie felt her own lips curve in answer. She wasn’t surprised Henry found it hard to be annoyed at his cousin—no doubt this man was accustomed to deploying his easy humour to smooth his path. It was probably not genuine, but it was very effective.

‘Eleanor said the two of you already did that,’ Henry replied. ‘So, how long shall you be staying?’

‘I have to see what awaits me in the East Wing. If it is anything like the chaos of the Folly, it will take more than a couple of days, I’m afraid.’

‘Oh, Good. Supper last night was dreadfully dull, but hopefully now you are here you will liven things up. I’m dashed glad you’re here, Chase.’

Chase Sinclair’s gaze flickered past Henry to assess Ellie’s less-welcoming expression.

‘Well, that makes one of us, Henry.’

Chapter Three (#ue50fdf6f-7dac-5c95-9e86-65b699c50dce)

Ellie paused halfway down the stairs, wondering how she had sunk so low that her stomach was contracting just as nervously at going down to supper as it did when facing Mr Soames at the bank. Henry called her indomitable, but she could not seem to find her balance now she was away from Whitworth.

Now she would not only have to face the combined hostility of Lady Ermintrude and the two Misses Ames, but also the mocking and perceptive Chase Sinclair. It would be a wonder if the masquerade didn’t unravel that very evening.

She didn’t even have any finery to hide behind. Her one good dress was pathetically dowdy compared to the cousins’ ostentatious mourning dresses and the under-chambermaid assigned to assist her had no experience being a lady’s maid, so Ellie had simply twisted her hair into a bun at her nape as she always did. At Whitworth none of this mattered, but here...

Perhaps she should plead a headache?

She sighed, gathering her courage as Pruitt opened the door to the yellow salon just as the clock finished chiming the hour.

‘You are late, Miss Walsh. I said five o’clock.’ Lady Ermintrude announced before her foot even crossed the threshold.

‘But...’

Henry raised his hands behind his aunt’s back and Ellie swallowed her words.

‘My apologies, Lady Ermintrude.’ She curtsied, something she had not done in years, wobbling a little on the way up. Henry stood by the window next to Mr Sinclair and the setting sun encased the two men in a red-gold halo, making Henry look more angelic than ever, in stark contrast to Mr Sinclair’s sharply hewn face, deep-set grey eyes, and black hair. Together they could have modelled for a painting of Gabriel and Lucifer.

Though perhaps not—one wouldn’t want to have Lucifer dominating that painting and Mr Sinclair certainly took up more than his fair share of space. He had changed out of his riding clothes and was dressed in a style she would have found hard to describe, but next to Henry’s tightly nipped waist and high shirt points he looked both less fashionable and much more elegant. Perhaps it was his sheer size. He appeared even taller in the civilised pale-yellow and walnut-wood colours that dominated the drawing room than he had in the shambolic room in the Folly. Without his greatcoat she could see the impressive breadth of his shoulders had nothing to do with its many capes.

It was strange that after the first disorienting moments of his appearance at the Folly and earlier in the parlour she hadn’t felt any real apprehension, but now in the safety of the yellow salon he suddenly looked dangerous.

He raised his glass as he met her eyes, his mouth quirking slightly at one corner. Lady Ermintrude’s eyes narrowed and Henry stepped forward hurriedly.

‘Eleanor, may I introduce my cousin, Mr Charles Sinclair. Chase, this is Miss Walsh.’

Mr Sinclair put down his glass and Ellie straightened her shoulders and waited for the man to add to her destruction in Lady Ermintrude’s estimation.

‘Miss Walsh.’ He bowed slightly, his voice cool and polite and nothing like the familiar tones he had employed in the Folly or with Henry. But just as her shoulders dropped a little he turned to Henry.

‘I didn’t know you had it in you, Cousin.’

Henry floundered at the ambiguous comment and there was a moment’s awkward silence, but Chase Sinclair merely went to stand by the fireplace, watching them as if waiting for the next act to commence.

There was a sudden stifled giggle from Fenella and both Lady Ermintrude and Drusilla directed a dampening look at her.

‘The betrothal is not yet a public fact, Charles,’ Lady Ermintrude said in her most damping tones. ‘It is hardly appropriate to be contemplating such matters while still in mourning. We would all appreciate if you refrain from referring to it in public or in front of the servants. Indeed, in any setting.’

Mr Sinclair arched one dark brow, but he gave a slight, mocking bow. Ellie indulged in some very satisfying silent rejoinders to Lady Ermintrude, but went to sit meekly on the sofa. Henry approached the sofa as well, but at a lift of Lady Ermintrude’s veined hand he chose a spindly chair instead.

For a moment there was no sound but the rustle and snap of the fire and Ellie battled against the absurd urge to succumb to giggles like Fenella even as she struggled to think of something, anything to say that wouldn’t make matters more uncomfortable. She caught sight of a book on the low table between the open fashion plates of La Belle Assemblée. She knew nothing of fashion, but surely Ovid was unexceptionable?

‘That is my favourite translation of the Metamorphoses.’ The words tumbled out of her and into a silence more awful than before.

‘I beg your pardon?’ Lady Ermintrude demanded. ‘You have been permitted to read such salacious blasphemy?’

‘I don’t think it is quite fair to call Ovid’s Metamorphoses blasphemy, Aunt Ermy,’ Mr Sinclair interjected. ‘His Ars Amatoria, on the other hand, can be safely called salacious, but I sincerely doubt Miss Walsh has read that. Or have you, Miss Walsh? If not, I recommend the third volume in particular.’

Ellie met her tormentor’s gaze, not at all certain she should be grateful to him for drawing Lady Ermintrude’s fire.

‘I won’t have you discussing such topics in front of my dear Drusilla and Fenella, Charles Sinclair! And you may take that book and put it with the rest of Huxley’s belongings. I do not know why it is here at all.’

‘Yes, Lady Ermintrude.’

Mr Sinclair obediently took the book and went to sit on a chair across from Fenella. Fenella giggled again, but subsided under her aunt’s glare.

‘How long do you believe it will take you to sort through the East Wing, Charles?’

‘I will try to be as quick as possible and not allow myself to be distracted by any salacious antiquities, Aunt Ermy,’ he replied and her ladyship snorted.

‘I sincerely doubt Huxley had anything salacious there aside from those horrid books. You will need help. I suggest that since Henry is engaged in estate matters and since Miss Walsh appears to be proficient in Latin and all that heathenish nonsense, she may be of some use in helping you sort through Huxley’s belongings. I do not believe in sitting idle.’

Ellie stared at her and Henry roused himself.

‘But Aunt, surely...’ His voice dwindled under her gaze.

‘Surely what, Henry? Speak up! I detest mumbling. Drusilla and Fenella are hard at work helping me with the embroidering for the parish’s Poor Widows and Orphans Society and do not have time to entertain your...betrothed. And since she so charmingly admitted she cannot set a stitch she will hardly be of use to us in our duties.’

‘Surely I could help with the housekeeping; I am...’

‘I oversee the housekeeping,’ Lady Ermintrude snapped. ‘You are not yet wed and until that day I see no reason to upheave Mrs Slocum’s routine. Meanwhile you may either be of use assisting the clearing of the East Wing or entertain yourself while Henry is engaged elsewhere. Now it is time for supper.’

‘Sorry, Eleanor,’ Henry whispered as they stood to follow Lady Ermintrude into supper. He looked so miserable she smiled and patted his arm.

‘Never mind, Henry. We shall laugh about it later.’

‘You might. This is my destiny.’ He sighed.

‘Coming, Henry?’ Lady Ermintrude barked and Henry took Ellie’s arms and propelled her after his cousins.

Inside the supper room Ellie realised Lady Ermintrude had taken another step in her battle to separate her from Henry. Leaves had been added to the already impressive table, lengthening it by several yards. Now Henry sat at one end, flanked by Dru and Lady Ermintrude, while she was seated at the other end with Charles Sinclair and Fenella. At least that meant she was far from Lady Ermintrude’s sharp comments and Drusilla’s brooding silences, but she felt sorry for Henry. If he’d hoped Mr Sinclair would swell the ranks of his supporters, he’d underestimated the superior tactical skills of his enemy. Though Ellie was a little surprised Lady Ermintrude felt Fen was safe in her sinful cousin’s presence, especially given Fen’s rather mischievous streak. This was immediately in evidence as Fen demanded ‘Cousin Chase’ regale her with London gossip, though she kept her gaze demurely on her plate, hiding her giggles behind her napkin.

* * *

In the end supper was not as horrid as Ellie had expected. She listened idly to the fashionable nonsense Mr Sinclair offered his cousin, rather in the manner of a man tossing a stick to a puppy. She herself had no interest in gossip about fashionable fribbles, but at least he was amusing and neither of them appeared to want her to contribute which suited her, leaving her to stew in her own concerns.

When these became too depressing, Ellie turned her attention to the dining room. It was very grand, but from experience she recognised the signs of economy in the draughts whistling faintly past the warped window frames, in the threadbare carpet and in the creaking of the uncomfortable chairs. Lady Ermintrude might be a wealthy woman, but it was evident she kept the household on a short string. Ellie’s hopes that Henry might be able to save Whitworth, already sinking since her arrival, sank further—what were the chances of Lady Ermintrude giving Henry funds merely for the asking?

She was deep in her morose calculations, but her ears perked up when Fen leaned towards Mr Sinclair and asked in a whisper, ‘What was that book you mentioned, Cousin Chase? Is it very wicked?’

Ellie glanced at Mr Sinclair. Surely he wouldn’t? He met her gaze with a slow, speculative smile that drew her into full alertness. Just as in the Folly she was suddenly utterly present, her senses absorbing everything—the sound of cutlery on china, the whisper of the draught just touching her nape, the flicker of the fire piercing the ruby-rich liquid in his wine glass.

‘Is it, Miss Walsh? Wicked?’

The single word twisted out of its mould and became an entity in itself. She had read several Greek and Latin tomes from her father’s library that might be considered fast for a proper young woman, but she had never thought they deserved the label wicked. Now, under the force of that smile, she was no longer certain. Of anything.

‘No! Have you read it, Miss Walsh? Is it one of those books?’ For the first time there was a glimmer of respect in Fenella’s eyes as she turned to Ellie.

‘I don’t think your aunt will approve you discussing such matters, Miss Fenella; certainly not with Mr Sinclair.’

‘You have read it. Do you think there is an English copy in the library?’

‘If I remember correctly there is one in Latin, Fen,’ Sinclair answered. ‘It would do you good to apply yourself to something other than embroidery and gossip.’

Fen wrinkled her nose.

‘Aunt never allowed us to study Latin. Only a little Italian so we can sing. She says German rots the mind and French enlarges the heart.’

‘Good Lord. I had no idea Ermy was a student of medieval medicine. I’m afraid to ask what she thinks about Greek. Something unmentionable in polite society, no doubt.’

Lady Ermintrude swivelled in their direction, causing Fen to stifle her giggle and apply herself to her syllabub. Chase motioned to Pruitt to refill his glass, then turned to Ellie.

‘I was wondering what it would take for you to smile again,’ he murmured. ‘Don’t let Ermy see you do that too often. Her hopes to scuttle your plans will only intensify if she sees that smile.’

‘Thank you for your concern on my behalf, Mr Sinclair.’

‘Being called Mr Sinclair always reminds me of my uncle. Not a nice man. Call me Chase, or, if you must, Cousin Chase like Fen does.’

‘It would hardly be proper for me to call you Chase and we are not cousins.’

‘We will be soon and since we are apparently to work together over the next few days, I suggest you try. I don’t answer to Mr Sinclair.’

‘Oh, good. That means our time together is likely to be very quiet and I much prefer working without interruptions.’

He laughed.

‘I see your weapon of choice is the sharp rebuke of silence. I cannot remember if that is among Ovid’s suggestions to women in his Art of Love. Did you really read it or is that merely bravado?’

‘Did you really read it or is that merely braggadocio?’

‘My God, Henry has no idea what he is in for. And you are quite right—I only read the interesting parts and skimmed the rest. I particularly liked the segment where he suggests women take a variety of lovers of all types and ages...’

‘Cousin Chase!’ Fen gasped, her spoon halfway to her mouth and her eyes as wide as saucers, darting from him in the direction of her aunt.

‘You are quite right, Fen, this is not a suitable topic to be discussed at the supper table, certainly not while such horrible pap is being served. Miss Walsh and I will discuss it later.’

‘Miss Walsh would as soon spend her day practising cross-stitches, Mr Sinclair.’ Ellie replied.

‘Is that a euphemism?’

Ellie did her best not to smile. The more he talked, the more her discomfort faded. He might be the irreverent rogue Henry said, but to regard him as a threat was ludicrous. In fact, she could see the wisdom of Henry’s hopes that at least with him in the house Lady Ermintrude’s fire would not be directed solely at her. And helping him in the East Wing would be an improvement to further demolishing her fingers with embroidery.

‘All that energy you expend trying not to smile could be better spent, you know?’ he said and behind the humour she saw the same speculation as in the Folly. It was a strange combination. Discordant. As if he were two wholly different people, like the two-faced god Janus—half-rogue, half-jester. And something else as well...

‘What then could be said about all the energy you expend in maintaining your rogue’s mask?’ she asked, curious which aspect would respond to her thrust. He didn’t answer immediately, watching her as he raised his glass.

‘A mask implies something to conceal. I am not so complex a fellow. Just like Lady Ermintrude I possess no hidden depths, I’m afraid. Fen could tell you as much. She has known me for dogs’ years, right, Fen?’

He flashed his cousin a smile and she shook her head.

‘He is hopeless. Aunt says it is only a matter of time before he and Lord Sinclair end in gaol or debtors’ prison or worse.’

‘With a hopeful emphasis on worse,’ Chase added.

‘I thought Henry said your brother was recently married.’ Ellie said and his smile shifted for a moment, went inwards, and contrarily Ellie felt her shoulders tense.

‘Lucas was always the serious one in our family. As befits the eldest sibling.’

‘Besides, she is an heiress,’ Fen said, leaning forward conspiratorially. ‘Aunt Ermintrude says...’

‘Do tell us what Aunt Ermy says about my sister-in-law.’ His voice did not change, but the table fell silent. Even Pruitt stopped in mid-motion, Henry’s plate of uneaten syllabub hovering. The power of Chase Sinclair’s stillness was as shocking as a full outburst of fury might have been and Ellie’s curiosity sharpened.

‘N-nothing,’ Fen replied, her shoulders hunched, and Ellie threw herself into the breach.

‘Henry told me she employs a man of business to manage her extensive financial concerns. I am very envious.’

His smile returned, a little wry.

‘You like the idea of ordering men about, Miss Walsh?’

‘I can see its merits.’

‘You may always practise on me, if you wish. When you aren’t smoothing over troubled waters.’

‘Ah, the mask is back in place. And just in time for Lady Ermintrude to call a halt to our evening’s entertainment.’

They stood as Lady Ermintrude rose and announced the women would retire.

‘Goodnight, Miss Walsh. Cousin Fenella.’ Chase Sinclair bowed properly, but ruined the polite gesture by murmuring in Latin as she passed, ‘Spero autem frigus cor calida fovere somnia.’

She could not prevent the flush that rose to her cheeks at the suggestive quote from Ovid, but she answered as coolly as his assessment of her heart.

‘I shall leave that office to my betrothed, thank you, Mr Sinclair.’

‘What did he say?’ Fen whispered as they left the supper room. ‘Something about sparrows in autumn and insomnia?’

‘Precisely. His Latin is quite atrocious,’ she lied, grateful that the darkened corridors masked her blush. The thought of hot dreams warming cool hearts did not sound quite as innocently romantic as when she and her sister Susan read that particular section of the Ars Amatoria. ‘He was merely trying to be clever and failing.’

‘Well, I am glad he is here. He is so wickedly amusing.’

‘Fenella!’ Drusilla admonished and Fen sighed and hurried after her aunt and sister. Ellie trailed behind them, looking forward to reading a book in bed.

Her siblings were rarely amenable to retiring before dusk and she could not remember the last time she had the luxury of reading herself to sleep. Bedtime at Whitworth was always a hectic time, rather like trying to herd stampeding bulls. By the time she herself reached her room she was too exhausted to do more than fall into bed and even then her mind was a whirl of worries about debts and mortgages that leaked into her dreams.

But instead of sinking into this all-too-temporary respite from her world, she sat staring at the walls well into the night, her mind full of fear of the future and the peculiar nature of the Huxleys. And Sinclairs.

* * *

‘Thank God!’

Henry collapsed into an armchair as Pruitt closed the door after the women’s departure. ‘I don’t know how much more of that I can bear.’

‘You shall have to develop an immunity, I’m afraid.’ Chase handed him a glass of port. ‘At least until after your wedding. Then I suggest you allow your bluestocking betrothed to deliver Aunt Ermy her marching papers. Having the two of them in one house is likely to prove disastrous. How the devil did you convince that unflappable piece of work to marry you, Henry? She is hardly your type.’

‘She is more my type than yours,’ Henry snapped.

‘I don’t have a type. It limits me.’

‘Well, I do. Ellie is the best woman I know.’

‘That still doesn’t explain why you are marrying her and certainly not why she is marrying you.’

‘You leave her alone, Chase.’

Chase laughed. Having observed Miss Walsh throughout that interminable meal, he realised his initial concerns about her were probably completely unfounded. Whatever sins her father had committed and whatever hidden currents existed in her own character, that core of schoolmistress’s rectitude was not assumed. But there was still something that did not quite ring true and it pricked his curiosity.

‘Don’t worry, Henry. I don’t poach and certainly not on virgin territory. I’m merely curious. Besides, you ought to have more faith in your beloved’s constancy than your concern implies.’

‘I’m not worried she will fancy someone like you; she is far too sensible. But I don’t want you bothering her with your teasing. This is hard enough for her as it is.’

‘Very gallant of you. I am doing you a service, though.’

Henry’s brows lowered, creating a sandy bar over his blue eyes, and Chase continued.

‘The more your beloved disapproves of me, the more Ermy is likely to approve of her.’

‘Blast you, Chase, you always make having your own way sound so reasonable.’ A grin replaced his frown and he sighed. ‘I hadn’t realised how awful matters are until we arrived this week. Have you had a look at the East Wing? Is it bad?’

‘Bad enough that I’m afraid I might go missing in that bog never to be found again, but it must be done. I am certain that if I left Huxley’s belongings to the care of Aunt Ermy she will have the lot of it thrown on to a bonfire and I cannot allow that; I do have some scruples.’

‘Why not let someone else see if there is anything worth salvaging so you can run back to London and your ladies?’

‘I am between ladies at the moment. Besides, I would rather see if there is anything of more than cultural value before I hand over the remains to the dry sticks at the Museum.’

‘What, have you run aground? Even with a new heiress in the family?’

Chase gathered in his temper once more and counted to ten. Henry’s freckles dimmed as he flushed.

‘Sorry. That was uncalled for. I only... Oh, blast. I’m in over my head. I never wanted to be Lord Huxley or a landowner. I was content working with the solicitors in Nettleton and I don’t know a dashed thing about sheep or land management or...or anything.’

‘That’s comprehensive. Chin up, Henry, it will become easier with time.’

‘No, it won’t. At least not until we can revive the estate to turn a profit. Uncle might have been a brilliant scholar, but he was a terrible landlord and it’s only Ermy’s money that keeps this place afloat. He spent every penny he had on travel and curios. It really isn’t fair he left them to you.’

‘Ah, I see the point of sensitivity about heiresses. I presume Miss Walsh is not bringing funds to this union?’

Henry’s expression was an answer in itself. Clearly Fergus Walsh’s estate had not recovered with his demise.

‘You should have proposed to Dru or Fen, Henry. Two plump heiresses ripe for the plucking and emblazoned with Ermy’s approval. They suit you better than Miss Walsh, anyway.’

‘How the devil do you know what suits me?’

Chase didn’t answer. His encounters thus far with his prim cousin-to-be were not conclusive and he had nothing to support his conviction Henry was making a very serious mistake. In fact, he could not quite make sense of Henry’s engagement. The title was modest but respectable and, without Huxley draining the accounts to pay for his travels and artefacts, in a few years the estate could be dragged into profitability.

If Henry chose, he could do better than an impoverished neighbour from a scandal-stricken family, past her first blush of youth and with nothing but passable good looks and a sharp tongue to recommend her. Strangely, though, Chase didn’t think she had done the running. Or perhaps it was merely his unexpected reaction to her accidental proximity in the Folly that was colouring his judgement. And his inability to pin her down. She was... He was not quite certain what she was. In her plain dress and her hair sternly disciplined into a depressingly practical bun, she looked every inch the spinster schoolmistress. She even ate like one—as if measuring each bite for its utility and dismissing the syllabub as pure frivolity.

But though her cool haughtiness did not appear assumed, it did not accord with that burst of temper in the Folly or her sudden and unsettling flashes of humour. Under the ice he sensed there were volatile forces at work and he wondered if she suffered from any of her father’s instability of character. For Henry’s sake he hoped not.

Henry sighed and put down his glass, dragging Chase out of his uncomfortable reverie.

‘The truth is I’m glad you’re here, Chase. Don’t take it wrong, but I think Aunt Ermy might resent me and Ellie less if she has you to dislike. Ellie isn’t precisely the type of biddable females Aunt is used to.’

Chase smiled despite himself and rubbed the sore spot on his thigh. That was a mistake, as the memory of their near tumble down the stairs woke other aspects of his anatomy. Her mercurial transformation from ice maiden to scolding hellcat was a very enticing combination, dowdy or not.

‘You just might be luckier than you deserve, Henry.’

Henry stood and stretched.

‘I know. She’s a good ’un. Well, goodnight, Chase. I must rise at dawn for some absurd reason to do with sheep and pastures.’

‘You won’t object to Miss Walsh helping me in the East Wing?’

Henry yawned and wandered towards the door.

‘No, she will enjoy rooting through Uncle’s rubbish heaps. She likes books and things.’

‘Aren’t you worried I might take advantage of her?’

Henry’s laughter trailed back from the hallway and was swallowed by another jaw-cracking yawn.

‘She can keep you in line, believe me. G’night, Chase.’

Chapter Four (#ue50fdf6f-7dac-5c95-9e86-65b699c50dce)

Two steps into the passage connecting the East Wing to the rest of the Manor, Ellie understood why the servants were so reluctant to enter the previous Lord Huxley’s domain. The passage walls were lined by glass-fronted cabinets crowded with a bizarre and unsettling collection of masks, jars, figurines and other artefacts.

Like a child witnessing something she knew was forbidden, she was drawn inexorably by a collection of jars filled with viscous fluids and what appeared to be lizards or snakes or...something.

She approached cautiously and rose on tiptoe to make out the contents of a particularly large glass jar with a purplish mass inside. It looked horrid, but her disgust wasn’t sufficient to counter her curiosity and her hand rose towards the latch securing the cabinet door.

‘Careful.’

She jerked away from the voice directly behind her, her hands flying out to stop her descent towards the cabinet, and an arm closed about her waist, pulling her back.

‘Trust me, you don’t want to bring that lot crashing down on us. I’ve already torn one pair of trousers because of you and I don’t want to sacrifice another.’ His breath was warm against her ear and temple as he held her against him and again she felt the unravelling of heat, her body exploring the points of contact with his as it had yesterday. It was foreign and unwelcome, but too powerful to reason away.

Like other unwelcome realities of life, she allowed it to present itself fully before she set about beating it back. Piece by piece. She began by prying his hand from her waist, which was perhaps a mistake because his hand felt just as warm and strong under hers as it felt against her waist. She dropped it and moved away, focusing on the disgusting object in the jar.

‘What is that?’

‘That is...or rather was an Egyptian cat. A mummified one. My cousin thought it might be interesting to see what would happen if he rehydrated a mummy.’

She moved away, feeling a little ill.

‘That is horrid. Why is it purple?’

‘The gauze around the mummy was decorated with indigo. It is a rather dominant colour.’

‘Why on earth would they do that to a cat?’

‘Cats were considered sacred in ancient Egypt. One of their gods, Bastet, even had the form of a cat and not far from where we lived in Egypt there was a cemetery dedicated solely to felines. Did you know it was said that if a house cat died a natural death the members of the household must shave their eyebrows?’

She touched the tip of her own eyebrow and he smiled. She took another step back.

‘That sounds rather extreme.’

‘No more than many religious practices and far less violent than some.’

‘True. What will you do with this relative of...Bastet?’

‘I think I shall donate her to the Museum. Along with her amphibian friends.’

‘Amphibian? Are those frogs?’

His smile widened at the revulsion in her voice.

‘Huxley was in his biblical phase at the time and was fascinated by the ten plagues of Egypt. Luckily, he confined himself to mostly frogs and locusts and avoided boils and the like. Would you care to see the locusts?’

She backed away yet another step, shaking her head, all too aware she was giving him fodder for his teasing, but the sight of that gelatinous feline was defeating her attempt to remain cool and collected.

‘Here,’ he said, moving forward. He twitched a string and a blind descended over the cabinet, hiding the most offensive sights from view. ‘Huxley wasn’t immune to their grisliness, though they did serve to keep other members of the Manor away. I’ll have them packed and removed first thing. Meanwhile you can help me in the study. There is nothing more terrifying there than reams of scribbles and more salacious Latin tomes.’

She followed, both resentful and grateful for his casual acceptance of her queasiness. She did not like being considered weak in any way.

The study was surprisingly small after the imposing passage, though the bookcases and the cherrywood desk were covered with haphazard stacks of books, bound notebooks, and papers. Chase went to stand by the desk, frowning as he leafed through one of the notebooks.

‘How may I help?’ she asked, clasping her hands before her.

‘Do you wish to? Or was this merely a ploy to escape from Aunt Ermy’s despotic influence?’

‘She clearly hates it when you call her that. But then I reckon you are aware of that. And delight in it.’

‘Delight is a word I prefer to save for more suitable subjects. My irreverence keeps her at bay and that is all I ask.’

‘Are you always so blunt?’

‘It saves time and effort.’

‘For you, perhaps.’

‘That is the whole point.’

She sighed and turned to survey the desk, frowning at the chaos.

‘What is it we need to do?’

‘You need to do nothing but hide until Ermy tires of toying with you, but I must begin working on this paper labyrinth. Go refresh your memory of Ars Amatoria. It is somewhere on the far shelf with the other immoral ancients. Just don’t tell Henry; he won’t thank me for colluding with your efforts to keep him on a short leading string.’

‘I am not Fenella, you needn’t expend so much effort trying to shock me, Mr Sinclair. If you wish to keep me at bay, you have only to ask.’

‘Do you really wish to help?’

‘I may as well be of use. And this place clearly needs a great deal of work if it is to be approached properly.’

‘That sounds intriguing. How would one approach it improperly?’

She really should know better than to encourage someone like Chase Sinclair, but she could not stop her smile.

‘You are giving a fair example of just that, Mr Sinclair. I do wish to help, if you feel I can be of use.’

It was the first time she had seen him smile without calculation or mocking and she wished she had not prompted the change. It was like the morning mist clearing outside Whitworth, revealing soft fields sparkling with wildflowers and dew—a moment of clear beauty, suspended and unique.

Even for a rake he was disconcertingly handsome, his face worthy of a renaissance sculpture, all sharp angles and hard planes, its harshness softened only by the fullness of his lower lip and the lines of laughter and mockery at the corners of his steel-grey eyes.

She was surprised Drusilla and Fenella weren’t infatuated with this unfairly endowed specimen of manhood, or perhaps they had once been and his light-hearted teasing cured them—he might look like a fairy-tale hero, or perhaps even a villain, but he certainly did not act like one. Heroes tended to take themselves seriously, but Chase Sinclair did not appear to take anything seriously, least of all himself.

But as she waited for his response, she again felt the presence of an inner shadow, as if another person entirely was moving behind the handsome façade, considering how to wield it to his advantage.

‘Very well,’ he said at last, placing his hand on a stack of slim leather-bound books on the desk. ‘These notebooks contain my cousin’s accounts of his travels in Egypt. All the years I knew him he always kept them in order and in custom-made trunks, but as you can see that is no longer the case.’

Ellie glanced from the stack on the desk to the shelves he indicated and realised they, too, were populated not only by books and curios, but also stacks of brown-leather volumes.

‘My goodness, there are hundreds of them!’

‘Possibly. I would like to send them to my sister at Sinclair Hall, but first I want to put them in order, so I can ascertain if any are missing and hunt them down in this paper bog Huxley created. I wonder what Mallory was up to allow matters to deteriorate like this. He was always a stickler for neatness.’

‘Are you speaking of Mr Mallory? His secretary?’

‘Yes. Do you know him?’

She smiled. ‘Why, yes. Well, not very well. I met him on two occasions when he visited Henry’s father before he passed away. He did strike me as a very competent and serious young man. I do hope the notebooks are dated, at least?’

‘The notebooks aren’t, but the entries are, so with some you may have to leaf through them to find a dated entry. If you prefer not to...’

Ellie planted her hands on her hips. It would be a relief to do something useful to keep her mind off her woes.

‘I shall be happy to help. I shall need some pen and paper so I can keep a record of the ones I have and perhaps separate them by year or month. And I think I will insert a sheet of paper at the beginning of each with its date and some reference to the notebooks which precede and follow it as I find them. Once I complete that stage, I will compile a catalogue so we can see which volumes are missing.’

She turned to see if her plan met with his approval, just in time to see his smile tucked away.

‘Did I say something amusing, Mr Sinclair?’

‘Not at all. You are the very model of good sense, Miss Walsh, and I commend your plan of attack. Mallory would approve. Pen and paper you shall have.’

‘What shall I do with these strips of paper?’ Ellie asked as she picked up one of the notebook with two notes dangling like pennants from between the pages.

‘Leave them. No, in fact, if you find anything, bring it to me.’

* * *

‘Oh, look!’

Chase looked. It was the third time that expletive had burst from Miss Walsh’s lips in as many hours, accompanied by a look of delight that was beginning to grate on his nerves. Not that it was not a charming sight—her mouth softening into her rare smile and her eyes widened and lit with joy, turning them from mere brown to warm honey flaked with dancing sparks of gold and the tiny glimmer of green around the iris.

For the third time Chase found his attention wholly captured by her excitement. This time he tried for dismissiveness.

‘What have you found tucked inside his notebooks now? Another mouldering pressed daisy? An ancient Egyptian shopping list, perhaps? For ten yards of mummy wrappings and a sheave of papyrus?’

‘No. This was under the notebooks and it looks quite old.’ She approached the desk, holding a small leather-bound book with the gentleness of a lepidopterist balancing a rare butterfly on her palm. He took it just as carefully, memories flooding back.

‘You are right; it is very old. It is a book of hours given to my cousin by a friend of his, Fanous, an abbot at a Coptic monastery near his house in Qetara.’

‘It is exquisite.’

It was indeed exquisite. A monk had probably toiled for months over the detailed illustrations and squiggly Coptic letters. The picture was of a man and a woman in medieval garb standing hand-fasted and heads bowed, either in joint prayer or in mutual embarrassment. He could almost feel the tension between them and he breathed in, surprised at his unusually sentimental interpretation of the image.

‘It is a wedding, I think,’ she said, her voice low and serious. ‘Look here in the corner, that is the priest and those tables might signify a wedding feast. Those look like greenish pumpkins.’

‘Either that or rotund babes. Those two clearly look as if they have anticipated their wedding vows.’

Her mouth quirked almost into a smile and she tucked a strand of light-brown hair behind her ear as she leaned over him to turn the page.

Unlike Dru and Fen she didn’t dress or curl her hair, just dragged it back into a mercilessly regimented bun that did nothing to enliven her looks. But the deeper she delved into the notebooks, the more she unravelled. Her bun was slowly loosening its hold and though she kept tucking the escaping strands of hair behind her ears, they rarely stayed there, adding character and life to her face.

‘See? These are their children, helping with the harvest.’ Her voice was low and warm, lost in the imaginary world she concocted from the colourful illustrations. This is probably how she saw her little world with Henry—a safe, bucolic haven surrounded by gambolling lambs and sandy-haired babes or honey-eyed little girls with determined brows and far too much intelligence for comfort. Reality, as he knew only too well, was unlikely to be as pleasant.

She turned another page and caught a slip of paper before it fluttered to the ground. It was covered in Huxley’s scrawl and before he could take it she read it aloud, a frown in her voice.