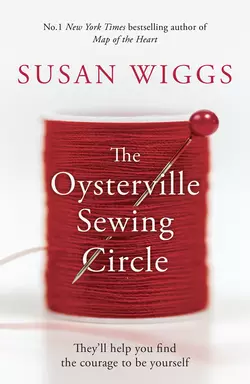

The Oysterville Sewing Circle

Susan Wiggs

The #1 New York Times bestselling author brings us a searing and timely novel that explores the most volatile issue of our time—domestic violence. Caroline Shelby has come home to Oysterville. And in the backseat of Caroline's car are two children who were orphaned in a single chilling moment–five-year-old Addie and six-year-old Flick. She's now their legal guardian—a role she’s not sure she’s ready for. But Oysterville has changed. Her siblings have their own complicated lives and her aging parents are hoping to pass on their thriving restaurant to the next generation. And there's Will Jensen, a decorated Navy SEAL who's also returned home after being wounded overseas. Caroline is drawn back to her favorite place: the sewing shop owned by Mrs. Lindy Bloom, the woman who inspired her and taught her to sew. There she discovers that even in an idyllic beach town, there are women living with the darkest of secrets – and one of those women is her. Thus begins the Oysterville Sewing Circle, where Caroline finds the courage to stand and fight for everything—and everyone—she loves.

THE OYSTERVILLE SEWING CIRCLE

Susan Wiggs

Copyright (#u5cd290a1-241d-5bf6-849a-4955efaba810)

Published by HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

The News Building

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

First published in the USA by HarperCollinsPublishers 2019

Copyright © Susan Wiggs 2019

Cover design © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2019

Cover photograph © Laura Kate Bradley/Arcangel Images (front)

Shutterstock.com (http://Shutterstock.com) (back)

Susan Wiggs asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008151386

Ebook Edition © September 2018 ISBN: 9780008151393

Version: 2019-07-12

Dedication (#u5cd290a1-241d-5bf6-849a-4955efaba810)

Contents

Cover (#u1a5555bd-c816-55de-b751-0f08a5b017c9)

Title Page (#u999ff0c4-8401-550b-aa54-0890639b05aa)

Copyright

Dedication

Prologue

Part One

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Part Two

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Part Three

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Part Four

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Part Five

Chapter 21

Part Six

Chapter 22

Part Seven

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Chapter 31

Epilogue

Author’s Note

Acknowledgments

Keep Reading …

About the Author

Also by Susan Wiggs

About the Publisher

(#u5cd290a1-241d-5bf6-849a-4955efaba810)

In the darkest hour before the breaking dawn, Caroline Shelby rolled into Oysterville, a town perched at the farthest corner of Washington State. The tiny hamlet hung at the very tip of a narrow peninsula, crooked like a beckoning finger between the placid bay and the raging Pacific.

She was home.

Home to a place she’d left behind forever. To a place that held her heart and memories, but not her future—or so she’d thought, until this moment. The chaotic, unplanned journey that had brought her here had frayed her nerves and blurred her vision, and she nearly missed seeing a vague shadow stir at the side of the road, then dart in front of her.

She swerved just in time to miss the scuttling possum, hoping the lurching motion of the car wouldn’t wake the kids. A glance in the rearview mirror reassured her that they slept on. Keep dreaming, she silently told them. Just a little while longer.

Familiar sights sprang up along the watery-edged roadway as she passed through the peninsula’s largest town of Long Beach. Unlike its better-known namesake in California, Washington’s Long Beach had a boardwalk, carnival rides, a freak show museum, and a collection of oddities like the world’s largest frying pan and a carved razor clam the size of a surfboard.

Beyond the main drag lay a scattering of small settlements and church camps, leading toward Oysterville, a town forgotten by time. The settlement at the end of the earth.

She and her friends used to call it that, only half joking. This was the last place she thought she’d end up.

And the last person she expected to see was the first guy she’d ever loved.

Will Jensen. Willem Karl Jensen.

At first she thought he was an apparition, bathed in the misty glow of the sodium-vapor lights that illuminated the intersection of the coast road and the town center. No one was supposed to be out at this hour, were they? No one but sneaky otters slithering around the oystering fleet, or families of raccoons and possum feasting from upended trash cans.

Yet there he was in all his six-foot-two, sweaty glory, with Jensen spelled out in reflective block letters across his broad shoulders. He was jogging along at the head of a gaggle of teenage boys in Peninsula Mariners jerseys and loose running shorts. She drove slowly past the peloton of runners, veering into the oncoming lane to give them a wide berth.

Will Jensen.

He wouldn’t recognize the car, of course, but he might wonder at the New York license plates. In a town this small and this far from the East Coast, locals tended to notice things like that. In general, people from New York didn’t come here. She’d been gone so long, she felt like a fish out of water.

How ironic that after ten years of silence, they would both wind up here again, where it had all started—and ended.

The town’s only stoplight turned red, and as she stopped, an angry roar erupted from the back seat. The sound jerked her away from her meandering thoughts. Flick and Addie had endured the tense cross-country drive with aplomb, probably born of shock, confusion, and grief. Now, as they reached the end, the children’s patience had run out.

“Hungry,” Flick wailed, having been stirred awake by the change in speed.

I should have run that damn light, Caroline thought. No one but the early-morning joggers would have seen. She steeled herself against a fresh onslaught of worry, then reminded herself that she and the children were safe. Safe.

“I have to pee,” Addie said. “Now.”

Caroline gritted her teeth. In the rearview mirror, she saw Will and his team coming toward her. Ahead on the right was the Bait & Switch Fuel Stop, its neon sign flickering weakly against the bruised-looking sky. OPEN 24 HRS, same as it had always been, back in the days when she and her friends would come here for penny candy and kite string. Mr. Espy, the owner of the shop, used to claim he was part vampire, manning the register every night for decades.

She turned into the lot and parked in front of the shop. A bound stack of morning papers lay on the mat in front of the door. “I’ll get you something here,” she said to Flick. “And you can use the restroom,” she told Addie.

“Too late,” came the reply in a small, chastened voice. “I peed.” Then she burst into tears.

“Gross,” Flick burst out. “I can smell it.” And then he, too, started to cry.

Pressing her lips together to hold in her exasperation, Caroline unbuckled the now-howling Addie from her booster seat. “We’ll get you cleaned up, sweetie,” she said, then went around to the back of the dilapidated station wagon and fished a clean pair of undies and some leggings from a bag.

“I want Mama,” Addie sobbed.

“Mama’s not here,” Flick stated. “Mama’s dead.”

Addie’s cries kicked into high gear.

“I’m sorry, honey,” Caroline said, knowing the soothing, overused phrase could never penetrate the five-year-old’s uncomprehending grief. With a scowl at Flick, she said, “That’s not helpful.” Then she took the little girl’s grubby hand. “Let’s go.”

A small bell chimed as she opened the door. She turned in time to see Flick heading the opposite way at a blind, angry run toward the road. “Flick,” she called. “Get back here.”

“I want Mama,” Addie sobbed again.

Caroline let go of her hand. “Wait right here and don’t move. I need to get your brother.”

He was quicker than any six-year-old should be, darting through the half dark across the damp asphalt parking lot. Within seconds, he was shrouded in mist as he headed toward the cranberry bog behind the store. “Flick, get back here,” Caroline yelled, breaking into a run. “I swear …”

“Whoa there,” came a deep voice. A large shadow moved into view, blocking the little boy’s path.

Caroline rushed over, engulfed in a sweet flood of relief. “Thank you,” she said, grabbing for Flick’s hand.

The kid wrenched his fingers from her grip. “Lemme go!”

“Flick—”

Will Jensen hunkered down, blocking his path. He positioned his large frame close in front of the boy and looked him in the eye. “Your name’s Flick?”

The boy stood still, his chest heaving with heavy breaths. He glowered at Will, giving the stranger a suspicious side-eye.

“I’m Coach Jensen,” Will said, showing a sort of practiced ease with the kid. “You’re a fast runner, Flick,” he said. “Maybe you’ll join my team one day. I coach football and cross-country. We train every morning.”

Flick gave the briefest of nods. “Okay,” he said.

“Cool, keep us in mind. The team can always use a fast runner.”

Caroline forgot how to speak as she stared at Will. There had been a time when she’d known the precise set of his shoulders, the shape of his hands, the timbre of his voice.

Will straightened up. She sensed the moment he recognized her. His entire body stiffened, and the friendly expression on his face shifted to astonishment. Nordic blue eyes narrowed as he said, “Hey, stranger. You’re back.”

Hey, stranger.

This was the way she used to greet him at the start of every summer of their youth. She had grown up on the peninsula, with salt water running through her veins and sand dusting her feet like a cinnamon doughnut from her parents’ beachside restaurant. Will Jensen had been one of the summer visitors from the city, polished and privileged, who came to the shore each June.

You’re back.

Now the decades-old greeting wasn’t accompanied by the grins of anticipatory delight they’d shared each year as they met again. When they were kids, they used to imagine the adventures that awaited them—racing along the endless beaches with their kites, digging for razor clams while the surf eddied around their sun-browned bare feet, feeling the shy prodding of youthful attraction, watching for the mythic green flash as the sun went down over the ocean, telling stories around a beach fire made of driftwood bones.

Now she merely said, “Yep. I am.” Then she took Flick’s hand and turned toward the Bait & Switch. “Come on, let’s go find your sister.”

The entrance to the shop, where she’d left the little girl, was deserted.

Addie was missing.

“Where’d she go?” Caroline demanded, looking from side to side, then lengthening her strides as she towed Flick along with her. “Addie?” she called, ducking into the shop. A quick scan of the aisles yielded nothing. No movement was reflected in the convex security mirrors. “Have you seen a little girl?” she asked the sleepy-looking clerk at the counter. Not Mr. Espy, but an overweight youth with a game going on his phone. “She’s five years old, mixed race, like her brother.” She indicated Flick.

“Is Addie lost?” Flick asked, his gaze darting around the aisles and display racks.

The clerk shrugged his shoulders and palmed his hair out of his face. “Didn’t see nobody.”

“I left her right here by the door, like thirty seconds ago.” Caroline’s heart iced with fear. “Addie,” she called. “Adeline Maria, where are you? Help me look,” she said to the kid. “She can’t have gone far.”

Will, who had followed her into the shop, turned to his team of sweaty athletes. “Go look for her,” he ordered. “Little girl named Addie. She was here just a minute ago. Come on, look lively.”

The boys—there were about a half dozen of them—fanned out across the parking lot, calling her name.

Caroline found the clean leggings and undies in a small heap by the door. “She needed the restroom. I told her to wait. I was only gone a minute.” Her voice wavered with terror. “Oh, God—”

“We’ll find her. You check inside the store,” Will said.

She grabbed the clothes and stuffed them in her jacket pocket. “Stay with me, Flick,” she ordered. “Do not let go of my hand, you hear me?”

His sweet round face was stony, his eyes shadowed by fear. “Addie’s lost,” he said. “I didn’t mean for her to get lost.”

“She was here a minute ago,” Caroline said. “Addie! Where’d you go, sweetheart?” They went up and down the aisles, looking high and low among the stocked shelves. The store seemed no different from decades ago. They passed bins of candy and bags of marshmallows for s’mores. There were fishing supplies in abundance and a noisy chest freezer filled with bait and ice cream treats. Boxes of soup mix and Willapa Bay oyster breading and fish fry. A sign designating goods from local vendors—kettle corn, bread, eggs from Seaside Farm, milk from Smith’s Dairy. Caroline’s mother used to send her or one of her siblings to the Bait & Switch for supplies—bread, peanut butter, toilet paper, cupcake tins … With five kids in the house, they were always running out of something.

She made her way methodically along each aisle. She checked the restroom—twice. The indolent clerk pitched in, poking around the supply room in the back, to no avail.

Good God. Good fucking God, she’d only been in charge of these kids for a week and she’d already lost one of them. They had come from the urban pile of Hell’s Kitchen back in New York City, yet here in what had to be the smallest town in America, Addie had gone missing.

Caroline unzipped her pocket and fumbled for her phone. No signal. No goddamn signal.

“I need your phone,” she said, grabbing the clerk’s from the counter. “I’m calling 911.”

The guy shrugged. At the same time, Will stuck his head in the door. “Found her.”

Caroline’s legs nearly gave out. She set down the phone. “Where is she? Is she all right?”

He nodded and crooked his finger. Feeling weak with relief, she grabbed Flick and followed Will outside to Angelique’s car—her car now, Caroline supposed.

She leaned down and peered into the window. There, curled up on the back seat, was Addie, sound asleep, clutching her favorite toy, a Wonder Woman doll with long black hair. Caroline took a deep breath. “Oh, thank God. Addie.”

“One of the guys spotted her,” Will said.

Flick climbed in through the opposite door, his face stolid with contrition.

Caroline collapsed momentarily against the car, trying to remember how to breathe normally. The panicked departure, the jumbled, seemingly endless days of the drive, her terrible fears and confusion, the careening sense that her life was reeling out of control, rolled over her in a giant wave of exhaustion.

“You all right now?” asked Will.

Another echo sounded in Caroline’s head. He’d asked her that question ten years before, the night everything had fallen apart. You all right?

No, she thought. Not even close to all right. Had she done the right thing, coming here? She nodded. “Thanks for helping. Tell your guys thanks, too.”

“I will.”

After so many years, he didn’t look so very different. Just … more solid, maybe. Grounded by life. Big and athletic, a square-jawed all-American, he had kind eyes and a ready smile. The smile was fleeting now.

“I guess … you’re headed to your folks’ place?”

“They’re expecting me.” She felt a sense of dread, anticipating a barrage of welcome. Yet it was nothing compared to the situation she’d fled.

“That’s good.” He cleared his throat, his gaze moving over her, the crappy car stuffed with hastily packed belongings, the little kids in the back seat. Then he studied her face with a probing gaze. His eyes were filled with questions she was too exhausted to answer.

She remembered the way he used to know her every thought, could read her every mood. That was all so long ago, in an era that belonged to different people in a different life. He was a stranger now. A stranger she had never forgotten.

He went around to the rear of the car, where she’d left the hatchback wide open. His gaze flicked over the crammed interior—hastily stuffed luggage and gear, her prized single-needle sewing machine broken down in pieces to fit, her serger, boxes of belongings. He shut the door and turned to her.

“So you’re back,” he stated.

“I’m back.”

He looked in the car window. “The kids …?”

Not now, she thought. The explanation was far too complicated to explain to someone she barely knew anymore. Right now she just needed to get home.

“They’re mine,” she said simply, and got back in the car.

(#u5cd290a1-241d-5bf6-849a-4955efaba810)

The cure for anything is salt water: sweat, tears or the sea.

—ISAK DINESEN

(#u5cd290a1-241d-5bf6-849a-4955efaba810)

NEW YORK CITY

Fashion Week

A plume of vapor from a garment steamer clouded the backstage section where Caroline was working. She and a couple of others from the Mick Taylor design team inspected, tagged, and hung each item in readiness for the show. The area was overheated with makeup lights, klieg lights, and too many bodies crammed into the space.

When an elite designer was about to unveil his work to the public, the bustling pre-show energy was palpable. Caroline loved it, even the stress and drama. Today’s event was particularly exciting for her, because several of the designs she’d created for Mick’s label would be featured. It wasn’t quite the same as having her own line, but it was definitely a step in that direction. Although she labored long hours for Mick, she used every spare moment to work on her own collection. She gave up lunch hours, social time, sleep. She was a striver. She did what it took.

This was a key show for Mick Taylor, too. The past couple of seasons had failed to impress the fashion critics and influencers. Investors were getting nervous. Buyers for high-end stores wanted to be blown away. Mick and his design director were on edge. The whole industry was watching to see if he would climb back to the top of the food chain.

Everyone on the design team had been told to focus on the wow factor that would carry the designer to even greater heights. Rilla Stein, the design director, was dogged and demanding of her staff, and her loyalty to Mick was absolutely ferocious. Most of the team members were terrified of her. Though she favored pointy glasses and Peter Pan collars and looked like a cartoon librarian, she breathed fire in the design studio and had the personality of a pit viper.

“Hey, Caroline, can you give me a hand over here?” called Daria. She was a model on hiatus due to pregnancy, and was now working as a stylist. Her girl-next-door looks and growing baby bump contrasted dramatically with Angelique, Mick’s longtime favorite model, who stood on an upended crate. Angelique had become the hottest runway model in the city. She hadn’t even gone through casting. Mick had anointed her as his muse.

She was sought after for her innate sense of drama and her ability to switch looks at lightning speed, sometimes in as little as thirty seconds flat. She had dramatic chiseled cheekbones, bee-stung lips, and the slightest gap between her teeth. Her wide-set eyes held a shadow of mystery. Daria had styled her with a bold palette of makeup and a swirling updo, bringing the model’s features into sharp relief. To those who didn’t know Angelique, there was something vaguely frightening about her, a trait that commanded attention. She was one of Caroline’s best friends in the city, though, and rather than being scared of her, Caroline was inspired by her.

Orson Maynard, a Page Six reporter and fashion blogger, introduced his newest intern, Becky Barrow, to Angelique. “She’s working on a blog post for me, and she’s been wanting to meet you,” Orson said.

“And now you have.” Angelique’s expression softened as she shook hands with Becky, who regarded her with worshipful eyes. Angelique had avid fans in the fashion world. She’d been discovered in her native Haiti by Mick himself, who had been on a shoot on one of the island’s dramatic beaches. The cutting-edge designer was known for going to third world countries and using local talent in his fashion shoots. He’d even won humanitarian awards for his contributions to the places he’d visited.

“You must have been so excited when Mick discovered you,” Becky said. “I’d love to hear how it came about. And is it okay to record?”

Angelique nodded. A mention on the right blog was good business. “Ah, that. It is not such a big story. I was just sixteen and as green as saw grass. I thought I was prepared, of course, because I was so keen. Haiti has some of the most beautiful beaches in the world. Every time I heard of a shoot going on near Port-au-Prince, I made myself useful, doing odd jobs and absorbing everything like a sponge. I learned to walk, to pose. I learned styling and makeup. I started asking for work. Any kind of work—fetching and carrying, running errands, translating because the people who came from the U.S. always needed an interpreter.”

“And that’s when Mick Taylor discovered you.” Becky was starstruck.

“Discover is not quite the right word. He noticed me on a shoot when I was too young to work. Then on another shoot a year later. By that time, I had my son, Francis—he’s six now. Yes, I was a teen mom,” Angelique said.

“You’re a fabulous mom, and Flick is amazing,” Daria said.

“A year after that, I had Addie and we were able to come to New York.”

“He changed your life.”

“Speaking of change,” Orson said, giving Caroline a nudge, “I hear you’re exhibiting your original designs for the Emerging Talent program.”

“I am indeed,” Caroline said, aiming for a casual tone. Deep down, she was wildly excited about the opportunity. She turned to Becky. “Don’t put that in your blog post, though. It’s not my first rodeo, and I’m a dark horse.”

“So you’ve exhibited before?”

“Several times.”

The Emerging Talent program, funded by a consortium of established designers who had formed a nonprofit in order to nurture new artists, was the most prestigious in the New York fashion world. A panel of industry experts would view the work of several designers. The chosen one would be given a chance to exhibit their collection at the biggest runway show of the season.

If the featured designs impressed the right people, it could be the start of a successful career.

“Five minutes, everyone,” called a production assistant.

“We’ll find you after the show,” Orson said. “Get the rest of the story.”

The energy in the room heightened a notch. With a critical eye, Caroline studied a cutout jersey dress she had designed. The look featured an experimental serape made of yarn from recycled sari silk. Rilla had raised objections to the woven pieces, but Caroline had held her ground. Regarding Angelique in her show-ready hair and makeup, she was glad she had. The look was arresting, otherworldly, a stunning way to lead off the show.

“You’re a fantasy woman,” Caroline said. “People are going to be picking themselves up off the floor when they see you.”

Angelique laughed softly. “I wouldn’t want to cause an accident, chère.” She tilted her head at a haughty angle, then stepped down and took a few practice strides.

“Amazing,” Caroline said. “You’re like a master class on how to walk past your ex in public.” She hesitated, then said, “Speaking of your ex, what’s going on with Roman?”

A few weeks before, Angelique had fallen in love. Roman Blake, a fit model for a big athletic brand, had seemed like her perfect match. He was stunningly handsome, with tattoos in all the right places, a shaved head that somehow made him even better looking, and—according to Angelique—mad skills in the sack. The few times Caroline had met him, she’d found him intimidating, with a flinty gaze and not much to say. He and Angelique had broken up the week before.

Angelique muttered a phrase in Kreyòl, her native patois, that needed no translation. “He is someone else’s problem now, I imagine,” she added.

“And you?” Caroline asked. “Are you doing all right?”

“I am doing fantastic,” she said, turning so the serape wafted like wings, “and I think it might have something to do with this fantastic look I’m wearing.”

Caroline backed off. She and Angelique and Daria were close, but Angelique had always been intensely private. “Thanks,” she said. “So you like it? Really?” Caroline was constantly second-guessing herself.

“Really, copine.” Angelique’s face lit with a smile, breaking through her signature coolness.

“I owe you big-time for this gig,” Caroline said. It had been Angelique who had introduced Caroline to Rilla, which had led to her getting the contract job. “If there’s ever anything I can do for you …”

“Let’s see … balance my checking account? Finish raising my kids? Find me a bigger apartment?” Angelique stuck out her tongue. “Just a few small favors.”

“I’ll get right on that.” Caroline thought of her own tiny checking account and apartment to match. Even if she wanted kids, she couldn’t afford them.

Angelique stepped back up on the riser and used a hand mirror to check her makeup. “Wearing your clothes is reward enough,” she said, and Caroline felt a rush of gratitude.

“I love everything about this look,” Daria said. “It’s going to stop the show, just you watch.”

“Thanks, Dar.” Caroline looked at them both—twin towers of excessive beauty. “There’s a special place in heaven for loyal friends.” She had enormous respect for what they did as runway models. But she never felt the urge—nor did she have the looks or skills—to join their ranks.

The industry could be hard, sometimes brutal. Up close and firsthand, she’d witnessed young women who barely made a living, crammed together in overcrowded apartments and struggling to make ends meet. Too many of them—even some of the most successful models in the business—suffered from eating disorders, financial manipulation by agencies, sexual predation, and loneliness.

As a designer, she struggled with her conscience. She was part of an industry that set up the models for a hard, even dangerous road. Early on, she’d made a promise that she wouldn’t fall prey to the industry’s worst practices. Her own designs were meant to be beautiful on any woman, not just a size 2 supermodel.

A flurry and buzz erupted as Mick himself swept through the staging area, leaving a ripple of excitement in his wake. Despite his stature in the design world, he looked unremarkable—modest, even. He was middle-aged and paunchy in jeans and a plain polo, and he had the affable mien of everyone’s favorite uncle. Those eyes, though. They were the clearest, brightest blue, the heart of a flame, and so intensely sharp they didn’t seem to belong in his ordinary face.

When he’d burst onto the scene, the press had described him as an everyman whose cutting-edge designs translated seamlessly into ready-to-wear looks. Emerging designers like Caroline regarded him as the perfect mentor—encouraging without demanding, critiquing without disparaging. She liked working for him because she’d learned so much. Looking at him now, you would never know his brand was on shaky ground and that he was just back from a stint in rehab.

He moved through the crowded space, pausing to make a comment or adjustment, greeting models and designers with an affable grin. Rilla, his shadow, followed behind, making more adjustments, though not looking at all affable.

“Well, well, well,” Mick said when he got to Angelique, who was still on the pedestal. She stood like a statue of a goddess, gazing straight ahead as if barely acknowledging his existence. “So this is our lead look today.”

Caroline held her breath while he inspected the garment. When he turned to her, she nearly passed out.

“This is your work?” he asked.

“I … Yes. It is.” Don’t stammer, Caroline, she told herself. Own it.

At his side, Rilla held up her clipboard and said something to him, sotto voce.

He nodded.

Caroline was half-dead by the time he spoke to her again. Had she done something wrong? Did he hate it? Was the upcycled sari too ambiguous? Would he insist on leading with a different look?

He paused, studied the outfit. She’d worked for hours to perfect it. He walked in a circle around Angelique, then turned once again to Caroline. “It’s brilliant,” he said. “What’s your name again?”

“Caroline Shelby.” Her reply came on a gust of relief.

“Good work, Ms. Shelby.” He gave her a thumbs-up sign, and then he strode away.

“Fix the armhole,” Rilla said in a clipped imperative.

Caroline slumped against Daria. “He likes it.”

Daria high-fived her. “He likes it.”

“Help me figure out what’s up with the armhole.” Caroline lifted Angelique’s elbow.

Angelique flinched and sucked in her breath with a hiss.

“Oh, sorry! Did I hurt you? Is there a pin stuck somewhere?” Caroline brushed aside the draped fabric. Then she noticed a smudge of concealer makeup along the edge of the garment. She grabbed a pad and scrubbed at it. That was when she noticed a livid bruise coloring Angelique’s side from rib cage to armpit. “Hey, what happened here? Oh my God, Daria, did you see this?”

“No.” Daria frowned. “Looks painful. Ange, how did you hurt yourself?”

“That.” Angelique pulled away and waved a dismissive hand. “I did hurt myself—I tripped and fell on the stairs. I’m so clumsy sometimes.”

Caroline felt a nudge of concern. “You’re not clumsy,” she said, exchanging a glance with Daria, who looked on, wide-eyed. “You’re one of the most graceful models in the business. Did someone hurt you?”

A production assistant with a headset and clipboard brushed past. “Two minutes,” she said to the group.

“I told you, I fell,” murmured Angelique.

Caroline was at a loss. Her hands worked independently of her mind, quickly altering the armhole even as she studied her friend’s bruises. “That’s not what this looks like. Talk to me.”

“Finish the draping,” said Angelique. “Do not make this into something that it’s not.”

Maybe it was nothing, Caroline told herself. Extremely thin models tended to bruise easily, which was another thing to worry about. But maybe she should heed what the subtle quiver of instinct was telling her—Angelique was in trouble.

“If you ever need anything … maybe just to talk—”

“I hate talking.”

“I know. I talk all the time, though.”

“I know,” Angelique echoed.

“Just … I’ll help, whenever you need me. I mean that. Any hour of the day or night. You can come to me anytime.”

Angelique offered a swift eye roll. “Listen, I’ve been on my own since I was sixteen. Taking a fall down the stairs is the least of my worries.”

“Places, everyone,” someone said. “Line up over here.” An assistant organized the models at the side entrance.

“Remember what I told you,” Caroline said. “If you ever need anything, if I can help—”

“Nom de Dieu, just stop.” Angelique’s face froze into a regal mask as she prepared to walk. A pro to the last inch of her shadow, she squared her posture, getting into character for the show. “We have work to do.”

“We’re not done with this conversation,” Caroline said.

“Yes, we are.” Angelique stepped down and followed a PA to the runway, gliding effortlessly to her place at the head of the line.

Music floated in from the runway area, and the backstage monitors showed a packed house. Caroline’s gaze was glued to a monitor.

“I’m worried about her,” she said to Daria as she tracked Angelique’s progress through the shifting sea of people to the head of the line.

“Me too. Was she in a fight? Did someone hit her?”

“I immediately thought of Roman Blake,” Caroline said. “They broke up, but what if he didn’t take it so well?”

“In that case, it’s good they’re history, then,” Daria said.

Caroline flashed on a memory from a few weeks back. A group of friends had met at Terminus, a club favored by actors and models. She’d spotted Angelique and Roman on the rooftop terrace, their postures tense as they spoke heatedly. Roman had grabbed her arm and she’d flung him off and walked away. Caroline hadn’t said anything that night. Now she wished she had.

“Guess so,” she said.

“And we could be totally wrong,” Daria pointed out, organizing a suitcase-size makeup box. “One time, I fell off a horse during a shoot and I looked like the walking dead for days. What are the chances that it might be exactly what she said, that she fell down the stairs?”

“When was the last time you fell down the stairs?” Caroline stepped back as more models made their way to the lineup. Another of her designs drifted past, but she was too distracted to inspect it. “I hope we’ve seen the last of Roman.”

Daria nodded. “Could it be someone else? A new guy? Someone from her past? What do you know about the father of her kids?”

“She once said he’s not in the picture and never mentioned him again.”

Daria gestured at the backstage monitor. “Look at her now. My God, Caroline.”

The screen displaying the action on the runway showed Angelique at the height of her powers, leading off one of the most important collections of the season. The dramatic lighting and the haunting music by Sade surrounded her angular, gliding form as she conquered the runway. Onlookers held still, leaning forward, their gazes devouring her.

“She looks like a fucking queen,” Daria whispered. “And that outfit …”

Caroline couldn’t suppress a smile as the look she’d designed created a stir in the audience. The top fashion critics and bloggers furiously scribbled or tapped out their notes as the camera flashes detonated.

Angelique did look like a queen, the controversial serape floating behind her like a royal robe. The last thing she looked like was a victim.

(#u5cd290a1-241d-5bf6-849a-4955efaba810)

On the day she was set to exhibit her original line for adjudication, Caroline stepped outside her apartment in the Meatpacking District. The crisp air had the kind of brilliant clarity that caused even the most jaded New Yorkers to lift their eyes to the diamond-sharp blue sky.

The light of late afternoon painted the entire landscape with layers of rare and shimmering gold. The temperature was exactly right for jeans and boots and a cozy sweater. Under such conditions, it was impossible not to appreciate the world’s most exciting city. She took the weather as a sign from above. People tended to romanticize New York City in autumn for good reason. When the weather gave the city a gift, it was spectacular.

Rolling her shrouded garment rack down the sidewalk, she buzzed and hummed with anticipation. Beside her—dwarfing her—were two towers of runway expertise: Daria and Angelique. Her friends were going to help showcase her designs for the panel of judges tasked with selecting the next candidate for the Emerging Talent program. As they passed the flagship store of Diane von Furstenberg, with spotless windows framing her iconic designs, Caroline felt a wave of nerves.

“I’m dying,” she said. “What if they hate my stuff?”

“They will love it,” said Angelique. Without the artifice of hair and makeup, she was still striking, long-necked and graceful, her bold features intense. “These people have taste.”

Caroline sent her a grateful smile. “I couldn’t do this without you,” she said.

“You could, but I am happy to help.”

“How are you doing?” Caroline asked. Tentative, not wanting to pry, but unable to forget the day she’d seen her friend’s body ripe with bruises.

“I’m brilliant,” Angelique said with a breezy smile. “I am ready to watch you blow the panel away today with this collection.”

“They’ve never seen anything like it,” said Daria. She was eight months pregnant now, and until today had been sidelined by the pregnancy. But with her full-moon belly and soft features, she was exactly what Caroline needed.

She was too broke to pay her models, but they had made a swap. She’d made school clothes for Angelique’s kids, Flick and little Addie. For Daria, she’d created a six-piece maternity wardrobe, and Daria swore that every time she wore something from the collection, people asked where she’d bought it.

“Did you get leg cramps?” Daria asked Angelique as they walked along. “When you were pregnant, I mean.”

“I did, yes, with Flick especially. When I was carrying my little boy, the cramps would keep me up at night. Try eating a banana at bedtime. The potassium might help.”

Caroline tried to picture her friend pregnant. Angelique would have been just sixteen or seventeen, already on her own in Haiti. Flick came along, and less than a year later, Addie—no partner to help. It almost made Caroline feel guilty about her freakishly normal family back in Washington State.

“Did you find yourself getting up every couple of hours to pee?” Daria asked. “That’s all I’ve been doing lately.”

“Welcome to the third trimester,” said Angelique. “Consider it training for getting up for night feedings.”

“You both make childbearing sound so pleasant,” Caroline said.

“What hospital did you use?” Daria asked.

“It was in Port-au-Prince.” Angelique cut her glance away, stepping around a crack in the sidewalk. “We came to New York when they were babies. Addie was still nursing. I remember that, because of leaks during one of my agency interviews.”

“Oh, man.”

“You should have seen their faces. They signed me, though, and because of Mick I didn’t have to go through casting.”

“They would have been crazy not to,” Caroline said. “You’re incredible.”

The venue for the design challenge event was a cavernous, light-filled old building that had once been a meat warehouse. Now it was at the center of the design district, a gathering place exploding with creativity. Caroline slowed her pace as they approached the big double doors.

“You seem nervous,” Daria observed, helping to navigate the rolling rack past a busy food cart and angling it into the staging area.

“What if they love something else more?” Caroline said, eyeing the other hopeful designers waiting to present their styles. She knew most of them, at least in passing. The world of design was a small one, and the pool of talent made for intense competition.

“You can’t think that way,” Daria said.

“Am I awful for wanting this so much?” asked Caroline. The event was renowned in the fashion world, and the stakes couldn’t be higher. She had entered the competition before but had never made the cut. Her collection was not edgy enough. Not tasteful enough. Not bold enough. Too bold. Incoherent. Unmanageable. She’d heard it all.

“Just awful, chérie,” said Angelique.

“This is my sixth attempt,” she said. “If I fail this time …”

“You’ll what?” Daria demanded.

Caroline took a deep breath. She remembered advice she’d read somewhere: Don’t ask who is going to let you. Ask who is going to stop you. “I’ll try again.”

“You never give up,” Daria said. “I like that. This is it for you. Sixth time is the charm.” She patted her pregnant belly. “This is our shot, and you’ve worked your ass off. It’s a can’t-miss. What’s this fabric?”

“It’s a silk jersey. Gets its shimmer from copper thread.” Caroline busied herself with the chosen looks on the rolling rack. The samples had to be flawless and pristine. Not a stray thread or fleck of lint. She had poured hours into these designs, and she wanted them to shine on the runway.

While she styled her models in the staging area, she couldn’t help having her doubts. There was so much talent crammed into the space, it was ridiculous. Several of the designers had attended the Fashion Institute of Technology, same as her. Others she knew from jobs at the big design houses. And they were good. She saw spectacular gowns, palazzo pants, dramatic sheaths, hand-painted fabrics, and shapes that draped the models like living sculpture.

She could feel the attention on her as well—for good reason. It wasn’t every day a designer showed up with a pregnant model and someone as well-known as Angelique. But Daria’s pregnancy was key to Caroline’s exhibit. Creating a collection like this was a huge risk. She knew that. She also knew that the biggest achievements of her career so far had resulted from risk-taking. Two years before, she’d landed the contract job with Mick Taylor by showing a collection of rainwear that changed color when it got wet.

Daria and Angelique were behind a folding screen, putting the finishing touches on their looks. Angelique stepped aside for a moment. “I want you to have a token—for luck.” She held out a triple-strand bracelet of small shells expertly strung together. “When I was a girl, I gathered cowrie shells on the beach and made bracelets to sell to tourists. The shell is a symbol of the ocean spirit of wealth and earth, and it offers goddess protection—very powerful, because it is connected with the strength of the ocean.”

Caroline held out her arm so Angelique could tie on the three strands. “You’re going to make me cry,” she said. “What did I do to deserve a friend like you?”

Angelique didn’t answer. Instead, she stepped back and said, “There, you’re fully protected. Now go and show off your hard work.”

Caroline rolled the garment rack into the showroom. The five-judge panel sat at a draped table littered with papers, cameras, smartphones, and coffee cups. The adjudicators were bright lights of the fashion world—a magazine editor, a fashion critic, and three top designers, all eager to find new talent. So many ways to fail, thought Caroline, hoping they couldn’t see her sweat.

She stood in front of her garment rack and unzipped the covering. Maisie Trellis, the critic, perched a pair of reading glasses on her nose and consulted the screen of her tablet. “You’re Caroline Shelby, from Oysterville, Washington.”

Caroline nodded. “That’s where I grew up, yes. It’s about as far west as you can get before falling into the ocean.”

“Tell us a bit about your career so far.”

“I went to the Fashion Institute of Technology and I’ve been doing contract work. My first job out of school was refurbishing vintage couture. I did alterations, piecework, anything that would help me pay the rent.”

“And now you’re designing for Mick Taylor.”

“Just finished working on a ready-to-wear collection.”

“Tell us about this.” Maisie peered over her glasses at the rack.

Caroline paused. Drew a breath. This was her moment. “I call this line Chrysalis.” She unveiled the rack. Fabrics in a palette of earth and sky tones shimmered in the autumn light through the windows. Daria emerged from behind the folding screen, her pregnancy eliciting murmurs from the panel. The fabric draped her ripe belly like a cocoon of gossamer, floating with every step she took. Next, Angelique stepped out, a willow-slim goddess, wearing a similar look.

“My garments won’t be obsolete after the baby comes,” Caroline said, encouraged by the expressions on the people’s faces. “Like a chrysalis, the top transforms.”

With a sweep of drama, Angelique demonstrated the conversion. The gorgeous tunic draped upward, fastening at the shoulders. “It creates a sling for the baby, and a modesty shroud for the nursing mother,” Caroline said. “It’s a piece that will last beyond the pregnancy, and even beyond nursing.”

She showed the rest of the collection, piece by piece. Each garment had a secret conversion achieved by different ways of draping and fastening. The fabrics were all sustainable and organic, with bright accents shot through with mother-of-pearl, a nod to her childhood home by the sea. She had created a signature grace note at the shoulder of each piece, a stylized nautilus shell highlighted with shimmering thread.

“What was your inspiration?” asked one of the judges. “Do you have children?”

“Oh my gosh, no.” In a moment of stark honesty, she added, “I doubt I’ll ever have kids. I’m the middle child of five, and I kind of got lost in my busy family. I do like other people’s kids, but I love my independence. My inspiration comes from people like Angelique and Daria. They’re working moms, and they deserve to wear beautiful things every day, through pregnancy, nursing, and beyond. And it’s also my commitment to sustainable practices. I imagine you hear that a lot. It’s a buzzword—what to do about textile waste created by discarded garments. My maternity tunic can live on as a nursing top and carrier sling, and the fabric source I used was CycleUp for most of the pieces.” It was the industry standard for recycled fabrics.

The panel inspected each garment while she watched, her heart in her mouth. Her craftsmanship was impeccable, every stitch in place, every edge and pleat knife-sharp. She knew this was her finest work. And when the demonstration ended, she felt a wave of pride. “This is the best I’ve got. I hope you like it. Thank you for the opportunity.”

The judges consulted one another, asked more questions, made more notes. Then Maisie dismissed her with an impenetrable look. “We’re intrigued, Caroline Shelby. But we have a long way to go today. We’ll let you know.”

(#u5cd290a1-241d-5bf6-849a-4955efaba810)

Caroline bumped her way down the stairs of her apartment, lugging an overstuffed suitcase. She always brought extra supplies to a show—fabric and thread, pins, scissors, touch-up for makeup, towels, a flashlight and double-sided tape, and wipes in case of model meltdowns … or designer meltdowns.

She was not going to have a meltdown today. Totally the opposite. Today was going to be a huge leap forward in her career. Finally, after so many abject failures and near misses, her Chrysalis line had been selected for the Emerging Talent program. The collection bearing her name would be showcased on the runway in front of all the fashion elite in the city.

If she impressed the right people, she would get her shot at creating apparel under her own name.

That, she knew, would be life-changing. People back home had never quite understood her aspirations. They had been kind enough. They were quick to say they appreciated her creativity. Yet they’d always been mystified by her life and work. Her entry-level jobs, most of them involving long hours and low pay, had struck them as thankless and unrewarding. Which was quite an indictment, coming from her family of restaurateurs.

But a line of apparel—that would be concrete proof that she’d set out on the right path. A ready-to-wear collection was a tangible achievement, something everyone could see. That alone was thrilling. It also gave Caroline the kind of fulfillment she’d always sought—the satisfaction of a particular creative hunger.

She had been focused on this goal for eight seasons of working for Mick Taylor. She’d learned a lot, but it wasn’t her dream. The dream was what she did after she went home, after she’d spent uncounted hours designing season after season of cutting-edge fashions under the keen eye of Rilla Stein. She’d learned to subsist on microwave burritos and too much caffeine, staying up long into the night to create something wholly her own, an exuberant expression of her unique aesthetic.

She pulled her gear along the sidewalk toward Illumination, dreaming of a day when she’d have assistants and stylists to help. Today’s show venue had a long runway and brilliant lighting, a waterfall backdrop, and tons of backstage monitors so she wouldn’t miss a moment. Every time she pictured her collection on display, she had to pinch herself.

She hoped her outfit was okay. She had opted for stark black and white, her usual work attire. The skinny black pants and boxy white top, chunky jewelry and flat shoes were well suited for rushing around the city.

The backstage was divided into two wings, east and west, separated by a folding wall. Caroline was assigned to the east side. In the staging area, a buzz of excitement vibrated through the air, which smelled of hair spray and aniline. She joined the flow of rushing designers, dressers, assistants, models, producers, photographers and their entourages, bloggers, and reporters. It was a ballet of barely controlled chaos as showtime approached. The established designers would show their collections, and Caroline’s debut would come at the very end.

She wove a path through the racks and found her station. She checked her notes and spotted Angelique standing on a riser and chatting with Orson Maynard, who was furiously taking notes.

“I heard a rumor that you’re responsible for all this lovely,” Orson said, regarding the fantasy ball gown Caroline had designed for Mick Taylor’s line.

“The garment’s my design, but all the lovely comes from Angelique.” Caroline noticed a raw edge peeking out of the bodice. “Hold still,” she said, swiftly threading a needle to tack it into place.

Daria arrived, huffing and puffing as she set down a box of accessories. She stepped back to admire Angelique. “Wow.”

“How are you feeling?” Caroline took a chunky cocktail ring from the box and tried it on Angelique.

“I’m good,” said Daria. “I’d rather be out on the runway, but you’re the only designer in need of a massively pregnant model.” She selected a makeup brush and touched up Angelique’s cheekbones.

“You both looked incredible at my presentation,” said Caroline.

Orson bustled forward with his notepad. “And …?” he asked.

Caroline had forgotten he was there. She ducked her head and busied herself by sorting through the accessories.

“You’re not supposed to have heard anything.” Caroline suppressed a riff of excitement.

“You know how the rumors fly,” he told her.

“What did you hear?”

“That your originals have been selected for the Emerging Talent program.”

She tried not to react. Tried not to hyperventilate. “Oh?”

“Stomp your foot once if it’s true, twice if it’s not.”

“It is true,” Angelique murmured between strokes of Daria’s makeup brush. “But you cannot say anything about it yet.”

“She’s right,” said Caroline. “This whole conversation has to be off the record.”

“Of course.” Orson put away his notes. “So I take it you’re stomping once.”

Caroline couldn’t keep the grin from her face. “The whole world will see at the end of today’s show.”

“It’s so awesome,” Daria said. “When I saw the work she submitted to the panel, I knew they’d pick her.”

“Now I’m salivating,” said Orson.

“I’ve barely been able to sleep or eat since I got the call.” Caroline was bursting. The moment she’d heard the news, her entire world had shifted on its axis.

“Can you set my phone by me?” Angelique asked. “I need to call my kids.”

Caroline propped the phone on a rack close by, and Angelique made a video call. Her daughter picked up, poking her face in close. “Maman,” she said in her little Minnie Mouse voice, and then asked something in Haitian Kreyòl.

“At the show, ti cheri mwen. Tell your brother to come.”

The picture tilted as Addie called for Flick. The two of them leaned in close, chattering to their mother in a rapid patois of French and English.

“Her kids are so danged cute,” Daria said.

Caroline poked her face next to Angelique’s. “Hi, guys! Remember me?”

“Caroline!” Addie clapped her hands. “You made me a hood with a mask.”

“That’s right. For when you need to hide from the paparazzi.”

“What’s paparazzi?” asked Flick.

“All the people who want to take your picture when you’re getting coffee,” said Caroline.

“I don’t like coffee,” Flick said.

“Then you probably don’t have to worry about the paparazzi,” said Angelique.

“When are you coming home, Maman?” asked Addie.

“After the show. After you’re asleep. Be good for Nila, okay?” She added something in French and blew them a kiss.

“They’re wonderful,” Caroline said.

Angelique smiled. “They’re my life.”

“I don’t know how you do it all, being a single mom and having this amazing career.”

Daria nodded. “It must be really hard. No idea how I could make it work if I didn’t have Layton.”

“I don’t wonder about these things,” said Angelique. “I do what must be done.”

Daria’s hand drifted to her distended belly. She gasped and moved her hand lower.

“Are you all right?” asked Caroline.

She nodded. “Braxton-Hicks contractions.”

“You’re sure?”

“Yep. Saw the doctor this morning.”

“Here we go,” a production manager called. “Five-minute warning!”

Caroline had to set aside her worry through the backstage frenzy of the show. Everyone pitched in to style the models and send them out to the percussive soundtrack that flowed through the speakers. Between hurried wardrobe changes, Caroline and Daria watched on the live-feed monitors set backstage. The buzziest stars and media types sat in the front rows along the runway. Plugged-in bloggers commented on the show in a constant stream, and the feed scrolled along the bottom of the monitors.

Even on the screens, the scene looked incredible. The theme of water and light worked beautifully. The models appeared to float along with the current projected on the surface of the runway.

“God, I love my job,” she murmured, watching a gaucho pants and midriff blouse ensemble she’d designed for Mick Taylor shimmer past the admiring crowd.

The accolades for the entire collection were enthusiastic, judging by the popping of cameras, the eruptions of applause, and the sight of critics and bloggers madly live-tweeting and broadcasting the show. She checked her phone’s live feed. The list that scrolled up the screen was filled with words of praise.

Daria high-fived her. “That was incredible. And we’re done here. The finale is coming from the other side of the stage. After that, it’s your moment.”

She shuddered with pleasure and nerves. “Cool. Let’s watch.”

Jostled by models hurrying to and fro to change, they found a spot by a large screen just as the final collection came from the opposite side of the stage. The soundtrack shifted to a haunting electronic version of Handel’s Water Music.

The lead model emerged, and a collective gasp issued from the audience. The live feed at the bottom of the screen immediately lit with comments. Caroline tilted her head up to watch. She blinked, then frowned in confusion. What the hell …?

The model, visibly and dramatically pregnant, was wearing a tunic. And not just any tunic. It was a piece Caroline had designed for her original line.

She grabbed Daria’s arm and dug her fingers in deep.

“Ouch! Hey—”

“Look at the runway,” Caroline said in a strangled whisper. At the far end, the model demonstrated the garment’s conversion from maternity tunic to nursing top, and the audience went crazy.

“Holy crap,” Daria said. “Is that …? Oh, God.”

“It’s my collection.” Caroline felt nauseous as her clothes paraded down the runway, garnering looks of admiration and bursts of applause. The garments were virtually indistinguishable from her designs. Her original designs. The samples were made from slightly different fabrics. More expensive headwear and footwear. Models she’d never seen before.

But the unique aspects of the clothing—the conversion from maternity to nursing to fashion, and even the stylized nautilus motif at the shoulder—had been lifted straight from Caroline’s own designs. A blatant, outright theft.

The collection was touted as Mick Taylor’s innovative new line called Cocoon.

Caroline crossed her arms in front of her middle as a wave of nausea reared up inside her. The sense of violation was as overwhelming as a physical assault, invasive and shocking. The live tweet feed at the bottom of the screen lit with more praise: Mick Taylor is back with a stunner of a collection.

Daria was saying something, but Caroline couldn’t hear through the roar of outrage in her ears. Her gaze stayed glued to the monitor, which now showed Mick Taylor at center stage, accepting accolades like a conquering hero.

All through the backstage area, the post-show rush continued to swirl like a tornado, but still she didn’t move. Yet her thoughts whirled around and around. Mick Taylor had copied her original collection, the one that was meant to launch her own career. The man she worked for, the man to whom she’d given her loyalty and hard work, had stolen her designs.

She staggered, dizzy with outrage. Angelique appeared at her side, bringing her to a stool. “Did you see?” Caroline asked, still too shocked to feel anything but numb disbelief.

“I’m so sorry. Come sit,” Angelique said.

“How completely shitty,” Daria said. “What an underhanded thing to do.”

Caroline took a deep breath. The numbness was wearing off and giving way to something more awful. Everyone knew what stealing looked like, but nothing could have prepared her for the shock of it. “I’m shaking. God, I feel so violated.”

“He is terrible,” said Angelique. “I’m ashamed to even know him.”

Caroline had to remind herself to breathe. This was a common occurrence in the fashion industry, happening at all levels. No one was safe. This particular situation was a virtual case study of a major label appropriating designs from an independent artist. Students in design school were told to expect it, and maybe on some level she had. The practice went by different names—“referencing,” “inspired by,” “an homage.”

Trying not to puke, she rocked back and forth on the stool. “No one is dead or injured,” she muttered. “No one has been given a cancer diagnosis. It’s not the end of the world.”

“That is right,” Angelique said. “You’re strong. You’ll get through this. You will go on to do great things.”

She tried to shake off the nausea. Tried to pull herself together. Her phone vibrated, the screen crowded with messages and notifications. After a few minutes, a new sensation coursed through her—a slow burn of anger. “Right,” she said. “I never got into this field because it was easy, did I?”

“Exactly,” said Daria.

“I’m going to go find him.”

“No,” said Angelique, her eyes widening. “Don’t do it, Caroline. Mick will—”

“He’ll what?” Caroline stood. The anger simmered like a fever, heightening her senses. “What will he do? Destroy my career? He’s already done that.” The reality shuddered through her: “I can’t show my collection now. I literally have nothing to lose.”

Daria and Angelique looked at each other. “I’m sorry,” Daria whispered.

Mick had planned the theft just right, Caroline realized. He had preempted her debut and sabotaged any attempt she might make to launch her line—with these designs, anyway. “I’ll survive,” she said with quiet conviction. “But that doesn’t mean I’ll go without a fight.”

To her utter mortification, an announcement was made, and her collection was sent out on the runway. The audience was expecting a big reveal of the Emerging Talent recipient. Caroline couldn’t bring herself to look at the monitors. She didn’t want to see the expressions on the faces of the attendees. Didn’t want to see them pointing and whispering, speculating about the rampant similarities between her designs and those of Mick Taylor. As far as the audience knew, she was the thief, not him.

It was the ultimate betrayal by a man she had trusted. She had a complicated relationship with him; for the past couple of years it had been the biggest relationship of her life, leaving little room for anything else. She owed her career to him. Yet today he’d stolen that and destroyed her in public. She felt duped and naive. How could she have trusted him? How had she not seen this coming?

Maybe she’d been dazzled by his fame, drawn in by his aw-shucks charm and charisma. Maybe she’d missed the signs.

Someone—a production assistant or intern—gave her a shove to follow the final model out onto the runway. What should have been a march of triumph had turned into a walk of shame. The applause was subdued, and instead of her prepared remarks about her inspiration and her expressed gratitude to Mick Taylor, she managed to choke out, “Thank you for the opportunity.”

There was a collective hush, followed by a scramble as the audience made for the exits. Caroline rushed backstage, on fire with a sense of betrayal.

“Caroline, wait.” Angelique reached for her.

Caroline shook her head, then wove a path through the crowd and made her way into the auditorium. It was emptying out slowly. The star designers were clustered near the runway, surrounded by their entourages, accepting congratulations, getting invited to after-parties, posing for photos, answering questions from the press.

Mick was easy enough to find, the center of an undulating cluster of reporters and photographers. He and Rilla were all smiles as they basked in the afterglow of the successful show.

Caroline jostled a path through the crowd. Rilla noticed her first. “Good show, Caroline,” she said. “The looks you worked on were so great.”

Caroline ignored her, even though Rilla was her mentor at work, the one who’d hired her and the supervisor she reported to. Rilla was supposed to protect her designers. But of course the design director’s first loyalty was to Mick.

Squeezing through an opening in the crowd, she planted herself directly in front of him. “You stole my designs,” she stated, speaking slowly and clearly.

He looked down at her, his brow quirked in a small frown. “Sorry, what?”

Several cameras snapped their picture.

She went up on tiptoe and said into his ear, “You copied my designs—your so-called Cocoon line.”

The frown deepened. His gaze flicked briefly to Rilla. Then he reacted with a patronizing smile. A few more camera flashes went off. “And what was your name again?”

Caroline knew the deliberate, direct cut was meant to put her in her place. Standing on tiptoe again, she cupped her hands and said with perfect articulation, “I’m about to be your worst nightmare. That’s who I am.”

His easy smile never wavered. Her bravado now felt like a curl of dread in her gut. Deep down, she knew what he was doing. “And five minutes from now,” Mick said, “no one will remember your name.”

(#u5cd290a1-241d-5bf6-849a-4955efaba810)

The door buzzer sounded in the middle of the night. Caroline scrambled out of bed in confusion and went to stand in front of the receiver by the door. All the locks were done up.

The buzzer went off again.

Still she hesitated. Nobody came to see her in the middle of the night. Nobody came to see her at all anymore. Not since she had declared war on Mick Taylor—and lost. She’d gone down in flames of glory. No, not even glory. All the righteous anger in the world was no foil for reality in the fashion business—designers stole from one another, shamelessly and blatantly, all the time. And the victims had almost no recourse. Mick held all the cards. He had the power to get someone fired and blackballed with a single swipe on his phone.

Shrugging into a hoodie, she went to the front window and looked out. Angelique’s car was parked on the street in front of the downstairs deli. What the hell? She buzzed her in, then clumped down the stairs.

“We need a place to stay,” Angelique said. “Me and my kids.” Addie and Flick clung to her legs.

“Did something happen?”

Angelique ducked her head, indicating the children. “Can you help?”

Caroline was not mystified. She knew this had something to do with the bruises she had observed on Angelique at the fashion show a while back. She nodded. Within minutes, they had brought the children up to her place. Her impossibly tiny place. Flick and Addie whined in sleepy protest. Caroline and Angelique managed to get them settled on the foldout sofa. After they were asleep, Angelique collapsed into a chair. Even in the dim light, Caroline could see that the model’s lip was swollen and crusted with dried blood.

“Who did this?” She got a damp cloth and some ice for her friend’s lip. “Was it Roman?”

“Roman? No. He’s … we’re … no.” She seemed confused, agitated. “I told you, I broke up with Roman. He’s not—”

“Is he pissed about the breakup? Will he be a problem?”

“Roman? No,” she said again.

“Then who hurt you? We need to get you to a doctor. Or the police.”

Angelique shook her head. “And be up all night answering questions? What do I do with my kids? Listen, I don’t need either. I’m … I just need to get away. I was behind on the rent. There was an eviction notice. Everything I own is in the car.”

“Ange, I had no idea. I thought you were doing so well.”

“My agency was deducting rent money from my pay—but not paying the rent. And that is only the start.”

Caroline knew some agencies were notorious for taking advantage of models. She didn’t want to press Angelique tonight. “Tell me who did this. This is serious. You need help. More help than I know how to give.”

“No,” she said again. “I can’t—I’ll be all right. It’s complicated.”

“It’s not complicated. You’ve been assaulted—and not for the first time. I’m calling the police.”

“You can’t. You must not. I’ll be deported.”

Caroline frowned. “Are you undocumented?”

Angelique nodded. “My work visa expired. If you call the authorities, I could lose my kids. I’m just so tired. I need to rest. Can we talk about it tomorrow?”

“Are you safe?” Caroline asked. “Were you followed?”

“No. I wouldn’t put you in danger.”

“Listen, you and your kids can stay as long as you need to,” said Caroline. “But if you don’t report this, there’s no guarantee that you’ll be safe.”

“I can’t risk being deported,” she repeated with a shudder.

“Then could you claim asylum or something? I know it’s probably not a simple process, but it would be a start.”

“I’m not starting anything tonight.” Angelique gave a weary sigh and dabbed gingerly at her lip. “It was a mistake to come here. I should go.”

“Don’t you dare. I want to help. But I have to know how. We need to figure out what to do in a situation like this.”

Angelique steadfastly refused to name her attacker. She refused to press charges. “My visa’s expired,” she explained again. “That means I’m here illegally. My kids are here illegally. I can’t risk it.”

“What happened to you is illegal, regardless of your status.”

“Perhaps, but I still won’t risk it.”

“What would happen if you did go back to Haiti?” Caroline asked. “Would it be the end of the world?”

“As a matter of fact, it would.”

“It would be worse than being battered by a man you’re scared to name?” She still suspected Roman, the jilted boyfriend, but for some reason, Angelique was protecting him.

“Haiti is much worse, and I do not say that lightly.”

“Seriously? Don’t you have family back home? Friends?”

Angelique looked at her for several seconds. “Let me tell you about life in Haiti. What I would go back to. We lived in the Cité Soleil slum—that’s in Port-au-Prince—in a shack made from sheets of corrugated tin. I was three years old when I lost my mother. I’m told she died of the cholera along with my baby brother. There is always a cholera outbreak in Cité Soleil.”

“I’m sorry. I didn’t know.”

“My father had no education because his family turned him out to work when he was ten years old. He survived by working as a bayakou.” She paused. “Do you know what that is?”

“No, sorry, I don’t.”

“Consider yourself fortunate that you don’t. You see, in Haiti, in many parts of the city, there is no sewage system. Families that can’t afford them have latrines instead. And these latrines need to be emptied. That is the job of the bayakou. My father earned the equivalent of four dollars a night doing this work. It was barely enough to keep us alive. He went out at night while I slept.” She paused. “Are you sure you want to hear this?”

“You lived it. I can handle hearing it.”

“He worked his job naked, because there was no way to clean clothes tainted by the filth. When I was very small, I was proud to have such a hardworking papa. By the time I reached school age, that all changed. The other children shunned me because of the labor my father did. You can imagine the names they called me.”

“Jesus, Angelique. I had no idea.”

“Most of the world does not. I was fifteen when Papa died. It was an infection. He was always getting something from the work he did—infections, sores that wouldn’t heal. He kept me away from him. I have no memory of ever touching him. When he died, I had nothing. I sold bracelets made from cowrie shells I found on the beach, and sometimes relied on the charity of strangers.”

Caroline gently covered Angelique’s slim, elegant hand with her own. Angelique’s nails were bitten and ragged. “You had it so rough. I can’t even imagine. Now I know you’re even more awesome because you found a way to survive.”

Angelique was silent for several seconds. Then at last she cried. Her tears were fierce and regal, and she looked like a queen sitting there, her life in tatters. “I came here to give my children a chance at a better life. What a terrible failure I am now.”

Caroline tried to sound confident and decisive. “None of this is your fault. And you’re not alone. I want you to try getting some sleep. Tomorrow we’ll figure out a way through this.”

Caroline didn’t sleep at all that night. She couldn’t. It was too upsetting to think about some monster hitting her friend. It was the height of frustration that she was at such a loss. She was angry—at her friend for not leveling with her. At the assailant Angelique refused to name. At the agency that exploited a vulnerable model. At herself for not knowing how to support her friend.

She spent hours online, researching shelters and aid organizations for both immigrants and victims of domestic violence. She stalked Roman Blake online. She stalked Angelique, too, culling through her list of friends and associates, trying to determine who else in her life might have attacked her.

In the morning, they went together to the kids’ school. Despite what had occurred the night before, Angelique looked incredible—her damaged lip concealed, fingernails trimmed, hair done, boxy top over skinny jeans with half boots. It made Caroline wonder how many times her friend had hidden the horrors she’d endured.

The children seemed unaware of the drama. They knew only that they were moving, a frequent occurrence in their lives. At the school, Caroline filled out a form designating herself as the children’s guardian and emergency contact. Then she convinced Angelique to go with her to the Lower East Side Haven, a place that provided services to victims. The staff there was discreet and moved with incredible swiftness, offering ways to keep her and her children safe. To Caroline’s surprise, no one pressured Angelique to name her abuser or to turn him in. One of the counselors explained that in the midst of a volatile situation, the priority was safety before justice.

After an exhaustive round of questions, the counselor said, “I wish I had better news. But I have to tell you, there’s a waiting list for accommodations. It’s a sad fact that the need is greater than what we can provide.”

Seeing the anguish on her friend’s face, Caroline took Angelique’s hand. “You and the kids will stay with me.” She turned to the counselor. “We’ll make it work.”

“Coming here was the right thing to do.” The counselor leveled her gaze at Angelique. “It’s incredibly important to have a plan.” She went through it step by step. Gas in the car. A prepaid phone, bought with cash. An emergency fund.

Angelique tensed up when the counselor asked about personal documents—ID, birth certificates for herself and the kids, insurance policies and papers, financial documents. She was caught in the horrible bind that so many undocumented workers with children faced. She could be deported at any time. She might be separated from her children. The prospect made her physically ill; Caroline could see her shaking.

“I’m sorry to have to ask this,” the counselor went on. “Do you have a plan for your children in case something happens to you?”

“The plan is that I’ll be the guardian. I know your kids, Ange. And it’s just a backup, after all.” Caroline tried to sound reassuring.

Angelique stared down at the stack of papers. She held herself very still.

“Every parent is obligated to have a plan, no matter what the circumstances. I know you love your children,” the counselor pointed out. “Have you made a will?”

(#u5cd290a1-241d-5bf6-849a-4955efaba810)

Caroline’s phone vibrated like a trapped bee against her chest. She ignored it. She was on a city bus, swaying under the weight of a duffel bag stuffed with vintage leather jackets that needed refurbishing. Thanks to Mick Taylor, she had been blacklisted. She had tried to defend herself, blasting Mick on social media, contacting bloggers and reporters. But the situation was all too common, and she was ignored. None of the design houses in the city would hire her, so in order to make the rent, she had to take in piecework the way she used to do when she was in design school.

It was a huge step backward. Many steps, in fact. After crawling forward for years, she’d been knocked all the way back to square one. Thinking about all the time and effort she’d poured into getting this far in her career, she wondered what the point was now. There were moments when she wanted to give up, to curl into a ball and wail about the injustice of it all.

And then, with the same dogged determination that had driven her to New York, she forced herself through those moments. Sometimes it felt like she was dragging herself from one side of the moment to the other through a pit of mud.

Then she would picture Mick’s smug, patronizing face, and the image would help her find the fire once again. How could she ever have thought he was her mentor, her mild-mannered surrogate uncle? He might have copied her designs, but she refused to allow him to steal her dream. And despite his status in the fashion world, he and his design director knew what they had done, whether they admitted it or not.

The trouble with being a design thief was that he would forever be in the trap of having to steal. Caroline knew she had an infinite variety of designs inside her. A thief was limited to those he could appropriate from others.

“You are an empty soul, Mick Taylor,” she muttered under her breath. “As empty as—”

The phone vibrated again. She wrenched it out of her pocket, but missed the call. As empty as my bank account. Christ.

She exited the bus as the phone vibrated yet again—another notification of an incoming call and a voice mail. She didn’t recognize the number. Maybe for once it would be good news. God, wouldn’t it be nice if she found a gig?

She ducked inside her apartment building to escape the street noise. The usual pile of junk mail had escaped the too-small boxes and littered the foyer of the building, which always seemed to smell like soup. Nothing of note. Coupons, credit card offers, her Con Ed bill with a U-shaped heel mark where someone had stepped on it, stamping it with the honeycomb tread of a high-end Apiary shoe.

She threw the mail on top of her duffel and lugged it upstairs, then set it down to let herself in. The door wasn’t locked, which rankled her. Since Angelique and her kids had come to stay, Caroline’s tiny space was even more crowded than ever. “Hello?” she called.

The apartment was quiet. There was … something. Something was off. Caroline couldn’t quite place the niggling sensation that prickled across her skin. It was subtle, just a peculiar heaviness in the air. An unfamiliar scent.

“Oh, hey, Angelique,” she said, shaking off the feeling.

Her friend was napping on the overstuffed sofa. She didn’t stir. Her routine was erratic sometimes, although each day after getting the kids off to school, Angelique went to church at Saint Kilda’s. It was just something she did, and she seemed private about it, so Caroline didn’t ask questions.

“Ange.” Caroline dragged the duffel into the room. “Hey, girl,” she said. “You left the door unlocked. Bad idea to—” Her phone buzzed again, and this time she picked up. “Hello?”

“This is the attendance clerk at Sunrise Academy,” said a voice. “We haven’t been able to get hold of Ms. Baptiste, and her children are waiting to be picked up. Your number is listed as an alternate contact. Would you have any idea where she is?”

“As a matter of fact, I just walked in the door, and she’s here.”

“Oh, good. Can you tell her to come right away? Unfortunately, it’s late and no one can stay with Ms. Baptiste’s children.”

“I’ll tell her,” Caroline said, feeling a twinge of annoyance as she rang off. How could Angelique forget her kids? “Hey, girl,” she said. “You need to get over to the school, stat. Your kids are waiting.”

Angelique still didn’t wake up. She didn’t move.

Caroline felt a weird knot of apprehension in her gut. Crossing the cluttered room, she swept aside the window drape and looked at her friend.

“No.” Her voice was a low plea of disbelief. “Dear God, no.” She froze for three beats of her heart. One—the angle of Angelique’s head. Two—the ashy pallor of her skin. Three—some kind of drug paraphernalia on the floor.