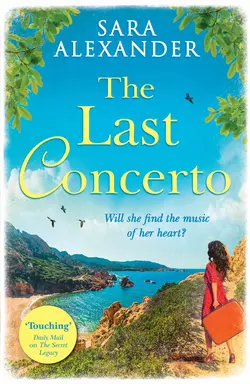

The Last Concerto

Sara Alexander

The perfect summer read for fans of Santa Montefiore, Victoria Hislop and Dinah Jeffries Will Alba find the music of her heart? Sardinia, 1968. When eleven-year-old Alba Fresu witnesses her father and brother kidnapped by bandits, her previously happy and secure family life is shaken to the core. The pair are eventually released, but the experience leaves Alba deeply disturbed, unable to give voice to her inner turmoil. While accompanying her mother to cleaning jobs, Alba visits the villa of an eccentric Signora and touches the keys of a piano for the first time. She is transported to another world, one where she can finally express emotion too powerful for words alone. She takes secret piano lessons and, against her parents’ wishes, accepts a scholarship to the Rome conservatoire. There she immerses herself in the vibrant world of the city, full of heat and passion she’s never experienced before – and embarks on an affair that will change the course of her life forever. But Alba soon reaches a crossroads, and must decide how to reconcile her musical talent with her longing for love and family... Praise for Sara Alexander: ‘Will leave readers riveted until the explosive conclusion’Publishers Weekly ‘This enchanting novel is a delightful read, perfectly suited for a warm beach with a cold beverage. Readers who enjoy Adriana Trigiani’s historical Italian family sagas will adore Alexander’s debut. ’Booklist

SARA ALEXANDER attended Hampstead School, went on to graduate from the University of Bristol, with a BA hons in Theatre, Film & TV. She followed on to complete her postgraduate diploma in acting from Drama Studio London. She has worked extensively in the theatre, film and television industries, including roles in much-loved productions such as Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows, Doctor Who, and Franco Zeffirelli’s Sparrow. She is based in London.

Also by Sara Alexander (#ulink_a14a1a14-95cf-5aa4-b265-bf984558aee0)

Under A Sardinian Sky

The Secret Legacy

The Last Concerto

Sara Alexander

ONE PLACE MANY STORIES

Copyright (#ulink_3e7751b2-b115-5b49-957a-5330e1f2ec1e)

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

First published in Great Britain by HQ in 2019

Copyright © Sara Alexander 2019

Sara Alexander asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

E-book Edition © August 2019 ISBN: 9780008273729

Note to Readers (#ulink_00b58f7f-4dc1-58c6-9735-c3f2328746eb)

This ebook contains the following accessibility features which, if supported by your device, can be accessed via your ereader/accessibility settings:

Change of font size and line height

Change of background and font colours

Change of font

Change justification

Text to speech

Page numbers taken from the following print edition: ISBN 9780008273712

For Mum & Dad, thank you for the piano

Music was my refuge. I could crawl into the space between the notes and curl my back to loneliness.

– MAYA ANGELOU

Contents

Cover (#u791455dd-ea03-5673-b72e-418631816e3f)

About the Author (#ufb9d9e9e-5561-56ee-b927-1a5d4f9f4310)

Booklist (#ulink_2f4b15ec-528d-50f5-96cb-77358320d7d5)

Title Page (#ub225fd78-8d50-5ba5-bde6-86b55c5c0959)

Copyright (#ulink_ea5e0aaa-462c-5af9-a97f-9c85d7abd976)

Note to Reader (#ufa9cd02d-91dc-545f-ad1b-50caf60fbc7f)

Dedication (#u1c55f6d4-d9c8-54ee-8b23-ef0f25732753)

Epigraph (#u2f356c8d-9882-53da-9f25-a158152e2b45)

I MOVIMENTO

CHAPTER 1 (#ulink_12650c58-e37b-50d5-a0a2-278ad0bc3cfe)

CHAPTER 2 (#ulink_fc64f88d-cd3c-57b3-9c4f-cd1273c1efb8)

CHAPTER 3 (#ulink_ecd1c225-055e-56ee-b6ef-17a28bcef594)

1975

CHAPTER 4 (#ulink_e8db799c-16c8-57ba-947e-920fa285b134)

CHAPTER 5 (#ulink_229c2a17-2fa2-580f-96cc-1d75e364e2f8)

CHAPTER 6 (#ulink_67a78faa-d823-576d-8267-7e0cad4f305e)

CHAPTER 7 (#ulink_2c5137fa-671f-5ba6-bbfc-53de391ea029)

CHAPTER 8 (#ulink_7e04047d-4020-5254-a8f5-ef2d83b37d84)

II MOVIMENTO

CHAPTER 9 (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 10 (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 11 (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 12 (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 13 (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 14 (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 15 (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 16 (#litres_trial_promo)

1978

CHAPTER 17 (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 18 (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 19 (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 20 (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 21 (#litres_trial_promo)

III MOVIMENTO

ROME 1988 (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 22 (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 23 (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 24 (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 25 (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 26 (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 27 (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 28 (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 29 (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 30 (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 31 (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 32 (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 33 (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 34 (#litres_trial_promo)

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS (#litres_trial_promo)

A READING GROUP GUIDE (#litres_trial_promo)

DISCUSSION QUESTIONS (#litres_trial_promo)

ABOUT THE PUBLISHER (#litres_trial_promo)

I Movimento (#ulink_3f26885b-1c02-5b94-b1d2-3fa65499da82)

1 (#ulink_0d2ffb00-6f8d-5b56-b3f1-c66e26e2ce46)

Overture (#ulink_0d2ffb00-6f8d-5b56-b3f1-c66e26e2ce46)

a piece of music that is an introduction to a longer piece

When her brother opened his eyes, Alba was convinced she was present at his wake. Her mother, Giovanna, knelt on one side of his bed, forehead resting on her thumbs whilst they crawled over the worn beads of her rosary. In the corner three wailers sobbed their own prayers in warbled unison, invoking Mary, Jesus and any saint who wished to assist. On the other side of the bed, their neighbour Grazietta held a bowl with oil and water. She told the women that the way in which the liquids mixed confirmed that Giovanna’s first-born, Marcellino, was, in fact, yet another victim of the evil eye. There could be no other explanation as to why he had been kidnapped alongside his father, Bruno, who was still held captive, whilst his son was released by the bandits the night before, after three days of white panic for all their family and friends. Grazietta grasped her wand of rosemary twigs and dipped it into the liquid, dousing the sheets like a demented priest. The wailers let out a further cry, which trebled across the sheets. A droplet fell on his forehead from another swing of the rosemary, this time a close miss of Alba’s eye. With his wince, everyone at last noticed that Marcellino was in fact conscious.

Giovanna jumped to her feet and held her child into her bosom. Alba could smell the reassuring scent of sofritto in the folds of her housedress, even from where she stood at the foot of the bed, those tiny cubes of carrots, onion, and celery fried in olive oil before making Sunday’s batch of pasta sauce for the week, cut through with the sweat of her panic beneath.

‘Biseddu meu,’ she murmured in Sardinian, rocking Marcellino with such passion that Alba knew it would induce a vague seasickness. This was a woman obsessed with omens. If the sauce boiled too fast, three starlings rather than two screeched their morning tweet, or a feather fell unexpectedly from nowhere, her particular strain of logic would portend horrific visions. She sang prayers to St Anthony at the crossroads in their Sardinian town when they needed something specific, accepting that it would lead, by necessity, to her forfeiting something in return. Alba had faded memories of her mother praying to miss her cycle one month because there was extra work to be done, only to be doubled up in excruciating pain the following month. Saints gave to those who prayed, but at a cost: the original protection racket. It sat at an uncomfortable angle in Alba’s mind, this idea of bargaining with a saint, the very thing she’d been taught was the devil’s speciality. Alba’s prodding at this point met only with the stone-setting stares of her aunts at best, physical harm at worst. She chose her battles with care, and made a silent pact with herself never to be indebted.

If something was lost, the Fresus would seek their neighbours’ cousins’ friends who were well practised in a branch of acceptable magic. In return for fresh eggs, home-made wine, or some other kindness other than money, these soothsayers would murmur secret prayers at midday at a crossroads on the second Tuesday of a month and relay a dutiful list of everything they heard on the street in order to find said lost item. One day, when twenty lire had gone missing from her mother’s kitchen drawer, one such prayer had returned with the word Francesco repeated three times. Alba remembers her mother pinning the unsuspecting labourers working on the house next door with her Sardinian glare, black eyes like darts, thick eyebrows scouring a frown, when she found out they were from out of town and all shared that very same name. After that incident Giovanna stitched her cash into her skirts like her grandmother used to do.

None of these accepted manias were woven into the morning of 27 May, 1968. No red sky in the morning to warn the shepherds, no burned garlic, curdled milk, dough that wouldn’t prove, solitary nightingale calls. It was a joyous late spring day, the kind that teases you with the golden kiss of the Mediterranean summer to come. Giovanna had shrieked at Alba to return in time to accompany her father to the vineyard, her brothers Marcellino and Salvatore needed a rest and besides, it was her turn, but the familiar trill of her mother’s voice fell on deaf ears. Alba had lost track of time, or rather decided never to pay much attention to it to begin with, and when she sauntered home at last, was met with the kind of pummelling from her mother that should have been reserved for the making of bread or churning of butter alone. Marcellino had been sent in her place and because of it, he now sat wrapped up in bed with her family facing a daily terror of a missing father.

Giovanna drew back and clasped Marcellino’s face in hers. ‘Eat, yes? Oh my tesoro, did they hurt you?’ More questions tumbled out, but the noise spun around the room like a gale. Grazietta muttered another snippet of a prayer before crossing herself and leaving, oily water in tow. As news spread to the crowd downstairs that the first-born had, at last, awoken, more women came upstairs and filled the room. Alba was shot a look that she recognized as her cue to bring the tray her mother had prepared. She pressed past the well-wishers and returned with the feast in hand, setting it down on his bed: fresh spianata, Ozieri’s renowned flatbread, enough cheese for a small football team, a handful of black figs, two long slipper-shaped papassini biscuits, and a glass of warm milk with a splash of coffee in it. If he wasn’t dead yet, it seemed the army of mothers were to kill him off with overfeeding.

‘O Dio mio,’ one of the wailers cried. ‘His eyes, Giovanna, the look in this poor child’s eyes!’

They took another breath in preparation for a further fervent chorus when a shout tore through the pause. The door flung open. Grazietta reappeared, face flushed, her circular wire glasses askew on her nose. ‘Benito’s on the television, Giova’, beni – come quickly!’

Giovanna followed Grazietta out, with the tumble of others close behind. Alba followed down the stone steps to their small living room. She’d never been in a room with so many quiet Sardinians. Even in church or at funerals words couldn’t fail to escape, a titbit of gossip, a grievance about the lack of flowers or the ostentatious abundance of them, the age of the priest or lack thereof. Now the dozen or more neighbours crammed into their room made Alba feel like the charred aubergines her mother would squeeze into jars throughout the summer.

On the small square of screen in the corner, above a chest of drawers topped with a lace doily, was her father’s brother Benito. The angle of the camera pointed up towards him; beyond, the familiar outline of the Ozieri valley in silver tones. He seemed relaxed, even though Alba was sure the words he spoke were some of the hardest he’d ever have to say. ‘I speak on behalf of all my family,’ he began. ‘The bandits have picked on the wrong man. Our family is not rich. We don’t have the money they are asking. We will not pay the ransom to release my brother Bruno.’

The lump in Alba’s throat became a stone. A murmur rippled across the room.

Then the scene snapped to men signing a form at the police station. The neighbours took it in turns to shout at the screen as they recognized their husbands, brothers, sons. The clipped voice of the Rai Uno journalist began to describe a town in revolt. The scenes flipped between the main square with men huddled in groups, back to the police station where the men were being described as signing onto a counter-army to uncover the whereabouts of Bruno Fresu. Their firearms were being registered. Shepherds from the surrounding hills had come to town to aid the search efforts, citing the fact that they knew their Sardinian hills better than any bandit. All this was happening for her father. The rescue efforts were coupled with a revolutionary protest about to take place, the journalist said.

The noise inside the stone room began to rise, the voices ricocheted over their heads to an unbearable volume. Someone called out from the street and the room began to herd out of the small door onto the cobbles. People lined the road outside her house. A cry pelted down from further up the vicolo just before Alba saw the first of the banners. A sea of schoolchildren from the upper years snaked around the corner, wooden signs above their heads. They were chanting and so were their teachers. There were decrees against the bandits. Someone shouted they had gone too far this time. Another screamed that the Fresus were one of the people, not rich folk. Even Alba’s teacher, the most prim woman she knew, waved a sign high above her head, yelling like she’d never heard her do before. The sea of students and teachers paraded past their house; there were shouts to not give up, to not give in, that Ozieri would stand against the criminal disease eating their island, that the bandits must not be bullied into taking one of their own by mainlanders. Alba should have been with her father when the men jumped out of a vehicle in the twilight. She should have been huddled with him in that damp cave, not Marcellino. A swell of guilt. Her father was the man who made her town revolt. No one marched when the rich landowners were kidnapped a few months back. There was little more than hand-wringing when the fancy American heir was kidnapped on the north-east coast the year before. There were even some hushed whispers that the rich had it coming to them, that their bandits maintained a warped equilibrium in society; the wealthy had no right to run their island as they pleased.

This time, however, they had gone too far. Her father was a hard worker; his father, Nonno Fresu, had accumulated huge debts to gain the first Fiat dealership in town. For this they were captured, for a ransom that none of them had. Bruno and his three brothers worked around the clock at the dealership. There was not wealth to speak of yet; it was swallowed by the bank. That’s why Giovanna cleaned villas in the periphery, took on extra washing, fed the babies whose mother’s milk had dried up, all to keep her own family fed.

Alba’s father was now a celebrity. He had started a revolution. Was it wrong to feel proud? Alba shook off the sharp twist of guilt, because thinking of her father in this way was the only way to stop herself picturing him shot through the head with his blood seeping out onto the fennel-scented dirt beneath him.

Alba woke to find her school grembiulino hanging on the door of the wardrobe she shared with her brother. This apron she wore over her own clothes looked like a relic from a distant past; one in which Alba played in the street, fought with her brothers, and recited poems by memory under the glare of her teacher. Life after Marcellino’s release and her father’s continued captivity was disorientating. Each time it seemed to tease reality, Giovanna would yell at her daughter for picking a fight with poor Marcellino as if his recovery rested on Alba’s behaviour alone. He was served his favourite breakfast every morning. Neighbours would stop their whisperings as he entered the room. It was like living with a celebrity recluse, and Alba suspected that her brother’s ability to mine the situation for all that it was worth, with more than a little performance thrown in, was apparent to no one but his younger sister. Thank God it wasn’t the girl, women would lament over the never-ending pots of coffee bubbled to calm the nerves of the tormented wife, but their voices were a constant reminder that she was not guiltless in all of this. If she’d been home in time, they might have got to the vignia earlier, missed the bandits perhaps. The life Alba once knew was nowhere to be found.

That morning the familiar dread of school awaited. Her black apron with the scalloped white collar a promise of normality. Giovanna took extra time saying goodbye to Marcellino. He walked beside her and Salvatore, only running ahead as usual when his friends caught up with him and enveloped him with their bombardment of questions. By the time they’d reached school Alba was sure that he had embellished his story from how it had begun in half sentences back at the house on that first day, when he’d arrived a scruff, mute in silent shock. Alba stepped through the tall gates of the elementary school, lit by the promise of life easing back to recognizable order. She took her place at the third desk from the front.

That’s when all her classmates stared. Unhurried Sardinian glares. Dozens of dark eyes pierced her. Her own darted across the once-familiar faces, but they seemed waxen, the disembodied type that haunted her dreams, people she thought she once knew who might spin off their axis on their own accord, or shape-shift into monsters.

Somewhere in the distance there was an echo of a familiar voice. Her gaze swiped to the front of the class. Her teacher peered at her over the glasses perched on the tip of her nose.

‘Well, Alba? What do you say to that?’

‘To what, Signora Maestra?’ she replied, trying to ignore the wave of dizziness.

‘Our class wishes your brother well. It’s polite to say grazie.’

Alba sipped a breath. Her whispered thank-you felt like it was warbling out from under water.

When the bell rang for morning break at long last, Alba shot out of the room to her usual spot in the concrete playground. The sun beat down. The noise was deafening; she’d never noticed how much her school friends shrieked. A hand tapped her shoulder. She twisted round. Mario Dettori stood before her, not a soul she despised more, his familiar sideways smile plastered over his face. ‘There she is, boys! The bandit girl!’

Alba pinned him with her hardest stare. He laughed.

‘What? Your brother spends a few nights in the woods and you’ve forgotten to speak too?’

He turned to the pack of snotty boys gaggled around him, cackling.

‘What do you say, boys? I think she looks wilder too now. Surprised you managed to remember how to get dressed. My uncle said they hung Marcellino naked in there!’

A snip-spark of something flamed in Alba’s chest. She didn’t remember throwing him to the ground, or swinging at his face, or breaking the skin, or the wild cries of the other children as they crowded around her.

Giovanna sat beside Alba. Her feet tapped nervously. Her bottom spread over the edges of the wooden child-sized seat. Alba stared down at her bruised knuckles. One of the cuts seeped a little blood as she bent it into a fist. Giovanna slapped them flat. Alba winced.

‘Thank you for coming, Signora Fresu,’ her teacher began, slicing through the room and perching on her desk. ‘Today has been difficult. For everyone. You and your family are under a lot of pressure, I know, but that is no excuse for the violence she instigated.’

Alba could feel her mother stiffen beside her.

‘Let me be blunt, signora. Alba is not a bright child at the best of times. She’s now missed two weeks of a critical time in school. She will never catch up with where she ought to be. And, to be frank, I think the experience you’re all going through is making her a danger to others. Let us recall the tussles back in the spring, the recurring altercations during the winter. Her ability to deal with typical childhood challenges is poor. At the slightest provocation she fights. This is not the kind of behaviour I am trying to instil in the girls in my class.’

Alba’s mind streamed incessant images of all the times her brothers fought her. The way her mother would admonish her for partaking but never them for instigating. She recalled the fights ignored by the teachers between two boys. The way Mario would always get palmed off with a disapproving stare whilst she would stay inside writing line upon line about why she should never fight. Her face felt hot.

‘So we are agreed, yes, Signora Fresu?’

‘Si. I know you know best, signora.’

‘I do. I will make allowances, but only if we expel Alba for this last month and have her retake the missed classes throughout the summer to catch up. If I allow Alba to stay in the class now, what kind of message am I giving to the others?’

Neither Giovanna nor Alba had an answer for that.

Their silence pleased the teacher.

The vice that strangled Alba’s household continued to tighten. Sometimes her mother looked like she was close to breaking, even though a stream of women flowed through the house delivering never-ending trays of gnocchetti, sauce, pasta al forno. Grazietta swept the swept floors, dusted where there was none to remove, and incanted prayers where necessary. Sometimes Alba would find her clapping into the corners of the room, shifting the menacing energy. Her brothers left for school each morning. Her uncles would come by for lunch, when they would update Giovanna on the search efforts. Alba wafted around the house like a ghost, finding comfort in invisibility. Grazietta would give her stitching to occupy her, but needlework was her nemesis, and after a while even Grazietta grew impatient with her.

Everyone’s prayers were answered a week later.

Her father’s release was the miracle the entire island had been praying for. Her town threw a festa in his honour the following day. It was the first time in their history that a captive was released unharmed and without a paid ransom. Bruno Fresu had left an indelible mark on Sardinian history. This, along with him remaining intact, unlike other victims whose ears or digits were cut off and sent to relatives as warnings, gave rise to nothing short of a national holiday. Tables lined the length of the vicolo. Every family cooked something for the feast. Her uncle Benito built a firepit at the end of their street and spent the entire day overseeing a suckling pig, dripping its fat into the moist flesh, caressed with rosemary wands dipped in olive oil, its salty scent curling down the street. The feast was bigger than any wedding any of them had ever been to.

Her father sat at the head of the snaking tables. He was thin. His skin pale. His eyes no longer the sparkling onyx Alba remembered. He shaved away his thick beard that had grown the past month, on Giovanna’s insistence. Without it, his face looked smaller still. Everyone raised their glasses. There were tears. Alba even noticed several of the older men wipe their faces, then place their flat caps on their heads to shade their emotions.

The party trickled through the night till the wine-infused singing began. The men warbled in their thick Sardinian voices. The sound rang up the stone fronts, echoed down the viccoli to the piazza. Alba imagined the valley beyond, plains humming with the distant rumble of their celebratory voices. And beyond further still, the empty caves where he had slept, the damp crevices where her father had been stowed. Her heart hardened, trying to clamp her tears from escaping. Everyone was celebrating now, it was no longer her time to grieve for her missing father. The tears crystallized into a heavy weight in her chest. She wanted to feel the happiness surrounding her, but it felt like she was celebrating a family she knew, not her own. She hated herself for begrudging everyone’s fawning on her brother, or rather, the flicker of infuriating pride she saw in his eyes as they caught her own. Marcellino was crowned the prince after all, and Alba, as always, the disappointing renegade. All the faces along the long table joined in her parents’ disapproval of the girl who should have gone through this mortal test but failed even to show up. Her father seemed happiest that his son had survived, more so even than being reunited with his family and having been released himself. Where Alba grasped for any feelings close to pride, relief or love, only anger surfaced, a bitter taste in her mouth, burned artichoke, singed pigskin.

Her father was closeted in quiet. After his return, the house became a hushed mausoleum. Alba had never seen her mother so stilted, tiptoeing around her kitchen so as not to make any sudden noise. She waved over at Alba, who was on dusting duty.

‘Come on, get a move on, I’ll be late!’ Giovanna whispered, emphasizing every vowel with a theatrical movement of her lips.

‘For what, Mamma?’

‘You’re to come to work with me today. I can’t leave you here. Babbo needs to rest!’

Before Alba could ask anything further, she was bundled out of the door and the two began marching uphill. The sounds of the market awakening clanked up from the main square. Giovanna stomped at full speed. Alba was glad the morning heat had not fully cooked. By the time they reached Signora Elias’s villa, Alba could feel the droplets of sweat snake down the back of her neck. Giovanna gave her daughter’s shirt a tug or two and it curled back into its original shape. She smoothed her work apron. The door opened.

Signora Elias appeared behind it, the doorframe encasing her like a painting of an aging Madonna, black hair scraped off her face into a low bun, streaked with waves of grey. Her face wrinkled into a grin. The tiny woman, with the sharp intelligent eyes of a bird, snapped her gaze from mother to daughter.

‘Buon giorno, signora. Sorry I am a little late today,’ Giovanna said, breathless.

‘Nonsense. Your husband had quite the celebration last night. I fell asleep to the sound of it!’

She stepped back a little to let the two inside.

‘This must be your girl, yes?’

‘Si. She won’t make any trouble, signora.’

Giovanna’s face creased with streaks of worry. Did her mother fear Alba might pick a fistfight with this old lady too?

‘Piacere, signorina,’ Signora Elias said, reaching out a hand for Alba to shake. No adult had ever done such a thing. Alba felt Giovanna flick her shoulder to reciprocate.

Signora Elias’s hand was small but strong. Her fingers were assured, muscular, belying her size and age. She looked straight into Alba, without the pity or mistrust she was more accustomed to receiving from older Sardinian women. They shuffled through the darkened hallway, along the cool of the tiles, which opened out into the biggest room Alba had ever seen. At the far end three sets of double glass doors framed the Ozieri plains. Parched yellows streaked with ochre beneath the graduating blues of the summer sky, and they stood as if floating in the space above it.

‘Stop gawking!’ her mother spat under her breath.

Alba scurried behind her mother as they worked their way through to the utility cupboard beside the kitchen and removed all the cleaning supplies for the morning’s work. Her eyes slitted sideways, registering the paintings on the walls, the huge Persian rug that covered the centre of the room. As Giovanna flew out through the kitchen Alba had just enough time to see the enormous range, the double oven below, the bold, colourful designs on the tiles surrounding it. Giovanna headed to the upper floors only to discover she’d left the broom downstairs. She ordered Alba to fetch it.

That’s when she heard it for the first time.

A golden sound; uplifting like the first light, reassuring as the afternoon sun’s streaking glow through the fig trees. In silence Alba’s feet stroked the carpet lining the stairs, not wanting to interrupt the cascade of notes running towards her, the mesmerizing trickle of a creek as it winds its way around mossy boulders and uncovered tree roots; cooling, comforting, ancient.

At the foot of the stairs she reached stillness. In the far corner of the room Signora Elias sat on an upholstered stool, facing towards the enormous glass-paned doors and the expanse of their burnished valley. Her fingers caressed the keys of a deep mahogany instrument. Its lid was lifted at an angle like a sail, the mirror sheen of the wood reflecting the paintings on the opposite side of the room. Bright yellow notes of birdsong followed by sonorous, melancholic blues. Alba couldn’t move. Signora Elias danced on further carousels of notes till, at last, her fingers eased down onto the white and black; peaceful, heavy. The song reached its final rest. Alba couldn’t quite count all the different tones and sensations that wove out of the piano, but she knew the ending made her think of a sunset dipped in orange and ruby, or the memory she had created of her father before the kidnapping, edged with the silver-grey tinge of a farewell.

2 (#ulink_446b33b0-e27f-5d89-a6b6-7f68f3334857)

Pianoforte

1. formal term for piano

2. mid-18th century, ‘soft and loud,’ expressing the graduation in tone

Alba couldn’t force the following week to pass quickly enough. The days dripped by unhurried, excruciating, as if she were listening to a leaking tap’s droplets echo into a metal watering can till it reached the rim. Her restlessness did not go unnoticed by Giovanna, who admonished her for hurriedly rolling out the gnocchetti from a large lump of dough, sweeping the floor without noticing what furniture she banged against in the process, and eating her food without chewing it first.

For Alba, the sounds around her became a claustrophobic symphony of erratic percussion; orderless, out of time, passionless. Her brothers rushed in from school each lunchtime, with stories of whom they had defeated in the playground, peacocking their self-appointed celebrity status amongst their peers for being sons of a hero. Her father would give them a swift glare, but his eyes smiled. He still spent his days in his room, but somehow the cacophony of her brothers brought him pleasure where the smallest noise of Alba’s broom would make Giovanna wince at best, swing her hand at her daughter at worst.

Alba tried to bury the worm of envy inching around her belly. When the feeling deepened, she thought about Signora Elias. The sounds of hungry boys and crisscrossing conversations then hushed into the near distance as the memory of her song rippled closer.

‘Alba! Do as your father said!’ Giovanna’s voice pierced the reimagined musical haze.

‘What, Mamma?’

‘Clear up. They’ve finished, can’t you see? Bring the cheese from out back.’

Alba stood and reached the cool stone cupboard towards the back of the room where several perette cheeses hung to form a hardened skin. She reached one and brought it to her father.

‘What’s got into you today, Alba?’ he asked, grabbing a knife and wiping it clean on the tablecloth.

‘Nothing.’

‘You’re a wet cloth. This is how you thank your mother? She’s supposed to be taking it easy. Lord knows we’ve put her through enough.’

We. The way he slipped that tiny word into his sentence made Alba feel like she was folding down into a tiny parcel of tight paper. We. Giovanna had wanted her to go. The events had all been, in part, her fault. Bruno gripped the round-ended cheese in his palm and carved a slice. The boys eyed him as if they hadn’t just licked their bowls of gnocchetti clean. Bruno passed each of them a peeled piece, which they prised off the tip of his knife, then started to peel the rind off his own.

‘Well, don’t just sit there, Alba. Go and help your mother.’

Alba left the room for the narrow kitchen beside it. Giovanna was filling a plastic container inside the deep sink with suds and water.

‘Is this how you’re helping him get better?’ Her words were swallowed by the sloshing water. Alba could hear the force of it smack against the side; thwacks of cascading frustration.

Replying was pointless.

At last, Wednesday rolled around. Giovanna’s calls for Alba not to run on so far ahead fell on deaf ears, or rather ears that were attuned to the treble of birdsong, the metallic click-clang of the house at the end of the street whose upper terrace was being rebuilt, or the bee that buzzed close, which Alba watched land on the passiflora creeping up a neighbour’s front door. As they wove further uphill towards Signora Elias’s home, the sun bore down and the cicadas hummed. Alba noticed their perfect synchronization, how their notes shifted but nevertheless sang in unison.

Alba rang the bell before Giovanna could stop her. And Signora Elias’s smile silenced Giovanna before she could yell.

‘Good morning, signora. Alba is with us again today, I see?’

‘Sorry, signora, it won’t always be like this.’

‘It’s been too long since I’ve had children in my house. I’ve been looking forward to it all week.’

She welcomed them inside. This time the smell of the silent house was powdered with a sugary vanilla scent. Alba’s mouth watered.

‘I’ve made sospiri this morning. I hope you’ll have some, Alba. If Mamma says it’s all right?’

Giovanna shook her head. ‘We’ll get on with our work, signora.’

‘Very well, Giovanna, but I want you to send Alba down when you begin with the bleach in the bathroom. Those smells are toxic for young noses. She will sit down here in silence, of course, until you come down again, yes?’

This time Alba knew her mother could not refuse. A victory. She would have grinned if she knew it wouldn’t lead to mild physical harm.

Giovanna raised her eyebrows in unspoken agreement. When Signora Elias turned away to walk to her piano, Giovanna gave Alba a glare. In the utility cupboard Alba found all the cleaning equipment from the week before. This time she took a moment to commit the kitchen to memory. The white-tiled counters stretched one length of the facing wall with a window at the far end, which opened out onto the valley. Beyond lay the purple hills of Tula surrounding Lake Coghinas. A small wooden table beside the wall opposite the range was covered in baking parchment and topped with perfect medallions of almond paste sospiri, dipped in white icing. They were uniform in size and the morning light cast a tempting gleam across the tops of their perfect levelled surfaces.

‘Run on up to your mother before she calls now, won’t you, Alba.’ Signora Elias’s voice made her jump round. Her guilt dissipated on seeing the old woman’s grin. ‘You’ll have some when you come down, I promise.’

Giovanna gave Alba several more chores to do before she at last allowed her downstairs with a squinty-eyed Sardinian glower. Alba left, trying not to look too happy about the fact.

‘There you are at last!’ Signora Elias called out, coming in from the kitchen with a porcelain plate of sospiri. She placed it down on a lace doily, which sat at the centre of a spindle-legged side table, a pink velvet hall chair beside it.

‘Do sit down, Alba, we were never meant to digest standing up, you know.’

Alba took a tentative seat.

‘Those are for you. And yes, I will be offended if you don’t finish them all. You’ve lived on our island long enough to know that, surely?’

Alba wanted to join her laughter, but the corners of her mouth clamped down the impulse, in case her mother heard.

‘This is my practice time, Alba. If you don’t mind, I will carry on as I always do. I don’t do very well if I don’t stick to my routines. I don’t go to church often like the other women my age in town. But if I miss my morning practice my day does go off track somewhat. Perhaps I’m getting old after all.’

Her smile lit up her little face, her eyes a dance of sagacity and infectious childlike joy. Alba took her first bite. It was perfection; sweet, nutty, smooth.

‘Glad you like them,’ Elias said. Alba looked up. The signora must have other magic powers beyond the songs her fingers made.

Signora Elias sat on the piano stool. She turned away from Alba now and let her hands rest on her lap. Alba watched her breathe in and out three times. For a moment she wondered if maybe the old lady wasn’t falling asleep. No sooner had she thought that, the woman’s hands sprang to life. Her wrists lifted and her fingers touched the keys, soundless, elegant as a ballerina’s silent feet.

They gave a twirl upon the keys, followed by a fierce, effortless run of notes. In her left hand, the notes spaced at even intervals undulated up and down towards the centre notes. In her right, her fingers trilled into ripples of watery movements as if the two hands fought to be heard over each other; a heated conversation. The music rolled on, in waves, urgent, chasing, till Signora Elias reached up for the higher notes, spreading her palm wide and playing stacked notes at the same time. The tune from the earlier passage repeated, fuller for the addition of the lower notes, emphatic. The scarlet sounds burst with passion, insistence. And then, as quick as the storm blew over the instrument, it fell back, like a tide fast retreating. The reds were replaced by golden yellow tones, making Alba think of how the sun shines all the warmer after a summer downpour. Yet beneath the hope, Alba heard nostalgia, as if the song harkened to a lost peace. The tune was a bitter balm. An involuntary tear left a wet streak on her cheek. Then the waves crashed in again, Signora Elias’s fingers racing, till, at last, her rocking hands wove an ending, the repetition of the midsection playing over echoes of the tumultuous start, reaching a truce, both points of view sounding in their own right.

And then it was over.

Signora Elias looked at Alba’s face.

‘The first time I heard Chopin’s Fantaisie-Impromptu I cried like a baby. You show remarkable self-control to shed only a solitary tear.’

Alba laughed at that, in spite of herself.

‘That’s the piece which made me want to become a pianist.’

Signora Elias held the silence, unhurried, as unflustered by it as the great splash of sound she’d just made. Then she stood up from her stool. Alba took it as her signal to leave, and she jumped up from her seat and pounced towards the stairs. Elias called out to her.

Alba turned back.

‘My piano. Would you like to play it?’

Alba wanted nothing more than to know how that magic poured out of her fingers, but she stood, frozen between terror and embarrassment.

‘Mamma will be busy for a while yet. I can show you some things. Only if you like, of course?’

Alba glanced towards the stairs, imagining the look on her mother’s face if she came down to see her daughter fingering this magnificent instrument.

‘Here, take a seat and I’ll adjust the stool to your height.’

Alba felt the thickness of the plush rug beneath her feet. She walked to the stool as if drawn to it by an invisible cord of golden thread. She listened to the metallic squeak of the stool as it rose.

‘Now, just place your hands on the keys, see what they want to naturally do.’

Alba did. They reflected back to her in the polished wood; twenty expectant fingers.

‘Have you ever sat at a piano, Alba?’

She shook her head.

‘Goodness. You hold your hands as if you have, my dear.’ Elias reached over and lifted her hands and moved them a little to the right until they seemed to be at the centre of the keyboard.

‘Why don’t you go ahead and play a few notes then?’

Alba turned to face Signora Elias, feeling like a trespasser.

‘Any note at all, any order, doesn’t matter, just feel the weight of them.’

Alba looked down at her hands. She pressed her second finger down. A bright sound rose up from beneath the lid, a fizz of yellow.

‘And another,’ Signora Elias encouraged.

Alba pressed her little finger down. This one was higher, prouder, a more certain sound.

‘What happens if you play one at a time starting with your thumb all the way up to your little finger, do you think?’

Alba felt the smoothness under the pads of her fingers, the thickness of the key, and let her fingers press down on each note in turn. A ladder, stepping-stones, sounds stacked on top of one another like building blocks.

‘Now come back down,’ Signora Elias said. Alba did. Her fingers were hot. They ached to touch every key, to hear the colour of each note, to race up and down like Elias.

‘Very good, Alba. Your fingers look quite at home there, wouldn’t you say?’

Alba looked up at Signora Elias. She hadn’t felt this safe since before her father’s ordeal, or perhaps ever. Her eyes grew moist. This time she swallowed her tears before they escaped.

‘Alba Fresu, what do you think you are doing?’ Giovanna cried, waddling down the stairs with buckets and brooms in tow. ‘Signora, I’m so so sorry – this won’t happen again.’

‘I think it would be criminal if it didn’t.’

Giovanna looked at her, unsure if she was about to be fired.

‘Giovanna, I would very much like to teach this young lady, if you and she were agreeable to the idea.’

Alba looked down at her fingers on her lap.

‘That’s very kind, signora’ – Giovanna flustered a laugh – ‘but right now we must get on and finish your downstairs and get home to make lunch. I’m so sorry if she made a nuisance of herself.’ Giovanna’s gaze flitted to the sospiri crumbs on the doily. Alba’s cheeks burned.

‘Very well, Giovanna, but once you’re finished you’ll take some of these sospiri home to your family, won’t you? No pleasure without sharing.’

Giovanna nodded. Alba jumped up from her stool.

They mopped the kitchen and downstairs bathroom in silence.

Outside, the heat swelled. The cicadas were in operatic form and the tufts of yellow fennel blossoms on the side of the road gave off their sweet sun-toasted anise scent. It was of some comfort ahead of Giovanna’s tirade.

‘What exactly did you make that poor old woman do? Did you ask her to play on that expensive piano?’

‘Of course not, Mamma, she asked me.’

Giovanna skidded to a stop. She pinned Alba with a glower. ‘Alba Fresu, we don’t have much, but I work every hour under the sun to teach my children one thing: honesty. You stand here lying to my face and think you won’t be punished? You wait till your father hears this.’

‘She asked me to listen!’

‘Maybe she did. But that’s no excuse to push your way in like a peasant. You know better.’

Tears of injustice prickled Alba’s eyes.

‘I’ve been waiting for the moment where you show some kind of thanks, for your father being alive, for having escaped this ordeal. But nothing! You float around like you’re invisible. Like a princess. It’s disgusting. You don’t talk. You help, but I have to redo the things after you’ve finished. Is this how I’ve taught you to be?’

Alba would have liked to cry then and there, to spit out that her night terrors were more than she could bear, that the feeling of a cave’s dampness skirted her dreams and waking hours, that she didn’t know how to describe the way her heart thudded in her chest for no reason during the day. That every bush held a secret promise of bandits lurking beneath. That their job was unfinished. That they would return for more. She longed to be held by her mother, told that everything would be fine, that one day she wouldn’t have the sinking feeling of dread trail her like a menacing shadow, that the dusk wouldn’t seep white panic through her veins. Instead, a sun-blanched silence clamped down.

‘There, you see? More sulky silence. Well, this has got to stop, signorina. You hear me?’

Alba swallowed. Her throat was hot and dry. The pine trees further up the hill swished their needled branches. Their woody scent wafted down on the breeze. Alba longed for them to be the comfort they once were.

3 (#ulink_13673ae2-2d99-58ce-b61e-9ba3a9c66ce7)

Fantasie

1 a free composition structured according to the composer’s fancy

2 a medley of familiar themes with variations and interludes

The following week, just as Alba was starting to speed up her run towards Signora Elias, her mother handed her a crumpled piece of paper. On it was a detailed list of vegetables she wanted Alba to buy at the market. Alba looked up at her mother.

‘Don’t just stand there. Get on down before it gets too hot. You can clean the artichokes and cut the potatoes. Get a can of olives from the shop and see at the end of the list I’ve added a few strips of pancetta. I’ll make pasta al coccodrillo for a treat, I know how much your brothers love that. They’ll be hungry after the morning at the officina.’

Giovanna’s words tumbled out in one blast of breath. Alba’s stomach growled. She wanted to think it was because she’d only eaten half a roll with her milk and coffee. Signora Elias was the highlight of her week. Her mother had just robbed her of it.

When they both returned home, Giovanna took her frustration out on the unsuspecting white-skinned onion she massacred into tiny pieces. Next, she launched an attack on the slices of pancetta, thwacked open the lids of passata from their glass jars, and ripped into the can of drained black olives that turned into little discs in a brusque breath or two. Alba was instructed to chop the slab of semi-soft fontina cheese into tiny cubes whilst her mother whooshed a pan with warmed olive oil and the softening onions. Pancetta was thrown in soon after, and the smell in their galley kitchen would have filled it with the promise of a comforting lunch if it wasn’t for Giovanna banging every pan on the range. Alba knew better than to ask what the matter was. Instead she eased her knife down through the cheese, taking her time so that she wouldn’t have to lay the table yet. Each blade slice, Alba half expected her mother to tell her how Signora Elias was that day, what she’d played, if it had been a swirling piece like the others. No descriptions of her morning were offered, but the way Giovanna threw a fist of salt into the boiling water of a deep stockpot for pasta made Alba worry she’d been fired for her daughter’s impoliteness after all.

Alba’s brothers returned soon after to bellows from their mother to scrub their hands. Alba carried the huge pot of pasta to the table. The fontina cheese had melted over all the pennette mixed in with the red pancetta sauce and olives. As she scooped the spoon down towards the base and up onto one of her brother’s bowls, strands of fontina oozed off it.

‘Coccodrillo, Ma?’ her elder brother, Marcellino, yelled from the other end of the table. He reached out a hungry arm for his bowl. He had entered his teenage years in earnest and Giovanna moaned about having to cook almost two kilos of pasta for their family these days. His thick black hair was like his father’s, and his crooked smile, and the way his eyes twinkled with unspoken mischief. His voice was deep and broad and he held the weight of an heir upon his wide shoulders with pride. Beside him sat their younger brother, Salvatore, who had their mother’s moon-shaped face and never fought to step out of his elder brother’s shadow. Salvatore had his grandfather’s patter and a speed of speech and reaction to match Marcellino. Neither measured the volume of their voices.

‘It’s a treat for you all today!’ her mother cried from the kitchen.

When all the bowls were full and Giovanna and Bruno took their places, silence replaced the gaggle of voices. The boys were sent out to play after lunch whilst Alba helped clear the table. Her father took his time to peel an early peach and chop it into tiny cubes, which dropped into his tumbler. When it was almost full, he reached for a slice of melon and did the same. Then he poured wine over the fruit-filled glass and began to swirl the mixture, pressing the soft fruit down with a gentle spoon until it was submerged. He scooped up his first spoon of wine-infused fruit. The smell made Alba’s mouth water. She found herself, as always, hanging to her place waiting for him to cast her a story, share a secret. Since his return home, none came. He was in his faraway place that Alba was instructed to never interrupt.

‘Let your father eat his macedonia in peace, Alba, and finish up inside.’

Alba followed her mother’s instructions. Her parents’ voices became muffled all of a sudden. It made her tune in through the doorway; when adults whispered there was always information that would be better known than not.

‘And Signora Elias wants Alba to go every day to do this?’ she heard her father say.

‘Yes. I don’t know why. She has a car. She likes to walk into town every day. But she says it would be a big help. And the extra money wouldn’t be so bad, would it? Get Alba out of the house doing something too.’

Her father harrumphed.

‘So shall I tell her yes, Bruno?’

‘Is this some kind of charity bone for us poor down in town, Giovanna? You be sure that Alba works for every one of those lire, you hear me? We’re workers not takers, you hear me?’

Alba heard her father’s feet climb up the stairs for his siesta.

Giovanna didn’t mention anything more of that conversation for several days. At last, over breakfast one morning, Giovanna looked up from her little coffee cup, which she had been stirring without stopping for several minutes. Alba couldn’t remember if she’d even put sugar in it yet.

‘Signora Elias would like you to do a job for her over the summer, Alba.’

Alba looked up. The bit of bread she’d dipped into her hot milk and coffee split from the roll and fell into her deep tin cup with a plop.

‘You will collect her morning rolls from the panificio and newspaper from the tabacchi each day. She wants you at her house by seven and not a minute later.’

Alba blinked. The woman who forbade her to go with her was now sending her to that house on daily visits. It was better than any Christmas.

‘Well, say something, child. ‘Thank you for the job. Yes, Mamma I’ll do that.’ Anything!’

Alba nodded.

‘I’ll take that as agreement to do the best job you can. Now, you and I both know that the poor lady is taking pity on me. Everyone knows what I’ve been through. Now my only daughter, the girl who is going to look after me in old age, who will make me a grandmother, doesn’t speak? That’s not how daughters are to behave. From the boys I’d understand. They need their father. But you? A shadow.’

The tumble of words were hot, like the boiling water that wheezed through the packed coffee grounds of their morning pot. Alba held onto the hope that her own silence would be like lifting that screeching pot off the gas ring.

Her mother stood up. ‘You start tomorrow.’

Alba jumped out of her bed the next day, prepared the coffee pot for her mother, set out the cups for all the family, and ran out of the door for the panificio, across the cobbled street that ran in front of their narrow four-room house, clustered in the damp shade between a dozen others behind the town’s square. Down the viccoli, washing draped in waves of boiled white flags of surrender across the house fronts. After a few hairpin turns along stony streets, meant for donkeys and small humans, not noisy cars, she reached the main road, which funnelled around their town, snaking out towards the hills that encircled the valley. The baker gave her a milk roll on the house and filled a small thick brown paper bag with a slice of oil bread and two fresh rolls. At the tabacchi, the owner, Liseddu, handed her a copy of La Nuova Sardegna over the counter, and then told her, with a wink, that she could have a stick of liquorice for herself. With her load underarm, she swung up to Signora Elias feeling like the plains opening up below were a promise. The cathedral steeple shone in the morning light, its golden tip gleaming at the centre of town. The huddles of houses, narrow town homes, clustered together straining for height, top floors encased with columned terraces, now gave way to firs and pines as she climbed towards the pineta, the pine forests of the periphery, the cool sought by young or illicit lovers, shadows protecting their secrets, their desires permissible for a snatched breath or two. Behind them the piazzette of the town, the greengrocers hidden within the stone ground floor of houses, the shoe and clothes shops for which the town was famous sheltered in the crooks of shady alleyways. Up here, in the fresher air beneath the trees that lined the hills surrounding her town, the men traipsed the ground for truffles or edible mushrooms. And in the unbearable heat of August, families would climb to seek respite from a punishing sun.

Alba loved the smell of this part of town. She turned her face out towards the trees, feeling their spindled shadows streak across her face, her mouth open now to the pine air, its earthy scent whispered over her tongue. On she strode, her feet crunching along the gravel that led to Signora Elias’s front door. She pulled down on the iron handle. The bell rattled inside the hallway. Signora Elias appeared. Her face lit up.

‘As I suspected. Your timing is, indeed, impeccable.’

‘Grazie, signora,’ Alba replied, and handed her the packages.

‘Lovely. They smell divine as always.’

Alba had never heard the daily bread described with such delight.

‘Do bring them into the kitchen, Alba, yes?’

She knew better than to do anything other than what she was asked. The kitchen was laid for two. At the centre were two porcelain dishes, one with a white square of butter and a smaller one with jam. A large pot of coffee sat on the range. The windows were open. The room filled with birdsong.

‘Grazie, Alba. Now, do sit down and have some with me. I’m sure you’re thirsty after your climb, no? Judging by the shine on your forehead I’d even say you ran.’

‘I did.’

That Alba knew something about this woman’s house made it easier for her to breathe, to speak, though it was impossible to decide whether it was the crisp, clear air, the light that flooded in from the surrounding gardens, or the peaceful silence of the home itself.

‘Here, do sit down after you’ve given your hands a wash, yes?’

Alba hesitated.

‘You won’t be late home.’

Alba watched Signora Elias light the pot and cut her roll, butter it, and smear it with jam. She handed half to Alba.

Maybe it was the home-made fig jam, the sound of the medlar tree leaves twirling in the light breeze just beyond the window, or the sensation of being in this lady’s kitchen, but Signora Elias was right: it was divine.

Once the pot simmered to ready, Elias poured herself a cup and signalled for Alba to follow her into the next room.

‘I think we ought to learn your first scale today.’

Alba looked at her, trying to mask the thrill soaring up her middle.

‘Only if you’d like, of course?’

‘I would love that, signora.’

She took her seat. They repeated the stool dance from the other day. Alba looked down at the shiny keys. She’d remembered where Signora Elias had placed her thumb last time and laid it back there.

‘Very good, Alba. You have a keen memory. That is wonderful.’

Alba turned her head to look at Signora Elias. She looked a little younger today.

‘Now, like the other day. Just five to start. Then we’ll reach up a little more.’

Alba was soothed by Signora Elias’s voice, firm yet gentle, like being under the protection of a queen. It felt far safer than the constant dodge of evil eye, that quiet but incessant terror that trailed Alba now that at any moment things might change, or be lost.

Signora Elias’s voice turned mahogany, rich tones that guided her up the familiar notes and then directed her thumb to scoot beneath her third for her to trace further notes still. Her fingers spidered across the new and familiar sounds, the sunlight streaming in from the double doors and lighting up the backs of her hands as if they too had been dipped into a little of the golden magic that overtook those of Signora Elias.

Throughout the summer Elias spun tales about numbers, their families, the way the notes were grouped together and why. Elias painted pictures with her voice and hands that described a cosmic symmetry. The mathematical patterns bewitched Alba, and the more Elias explained the more Alba yearned to know. At night, her terrors ebbed away as her fingers tip-tapped upon her sheets; up to five down to one, up to eight, down to one, one, skip to three, skip to five, down to three. She made up her own patterns too, which she showed Elias with great enthusiasm the next day. When the white notes sang out with confidence under her fingers, Elias introduced a few black ones too. This time the scale shifted mood. Here was a moonlit forest, a bad dream, something hidden in the dark. The scales peeled open like the pages of books, unfolding pictures of far-off places, imagined worlds, miniature stories of heroines in the wilderness. Elias showed Alba how to recognize the key notes within the scale, how they were all linked by intrinsic tone, vibration and mathematics. How it repeated up the keyboard, each eight notes resonating at double the speed as the same note eight notes below. Alba hung onto every word, every nuance, sepulchring the musical secrets, as if she and Elias were standing before an enormous map of the universe feeling her reassuring hand at her back that told Alba it was safe to sail.

1975 (#ulink_7590019b-74e5-5be9-ac5d-4d03943c6577)

4 (#ulink_4fa498a2-1d8e-516f-8239-3bda859399b2)

Battaglia

battle. A composition that features drumrolls, fanfares, and the general commotion of battle

For the seven years that followed, Alba’s fingers were in perpetual motion. Giovanna gave up yelling at her to cease their incessant tapping. Over time the compulsive movement paled into mild irritation because Alba performed her duties at home. The silent melodies became just another tic to join her other obsessive behaviours, like wiping a clean counter, scouring a gleaming range, or checking the taps were twisted tight. The more her fingers percussed, the less Alba spoke. The silence cloaked her in a guarded invisibility, a cocoon from which she could witness the world at a safe distance. After dinner, she would sit beside the record player and piano albums Signora Elias had lent her and play them without stopping. When Giovanna started moaning about the constant music, Signora Elias also let her borrow some headphones. The pieces she studied wove into her mind like a dance, and after listening for an evening, several sections would escape from her fingers onto the keyboard with ease. It was like repeating a conversation, almost word for word, and where discrepancies remained Signora Elias took time to make the necessary corrections, of which there were often very few.

Each morning Alba rose with the dawn she was named after, striding down to the bakery and back up through the hills of obsidian and crimson-streaked winter sunrises and the peony-orange haze of the summers. Signora Elias greeted her like a cherished granddaughter each of those days, never once forcing conversation, nor prying. The space they created every morning was a secret Signora Elias and Alba held close, clasped in complicit trust like the two photographic faces of a snapped-shut locket.

When her teachers crowbarred their way into Alba’s personal and mental space, yelling from their desk, haranguing her out of her self-imposed silence, Alba replayed minute details of Signora Elias’s mornings on a loop. The images squared into view, ordered, yet singular, like the family slides her neighbours would project onto their white walls, the mechanical clicks between each image a metronome chasing time; scales, morning light, gleaming floors, fresh coffee, arpeggios, the taut strings of the piano, their vibration, their frequency, their power.

May of 1975 was in full bloom. The grasslands surrounding Ozieri were splattered yellow with blossom. In the crags between the granite along the roadside leading up to Signora Elias, rock roses grappled with gravity, their fuchsia-purple blossoms widening to the sun. Giant wild fennel swayed on the gentle breeze, scenting the air with anise. Tiny orchids appeared in the cracks between the boulders; Alba gazed at their petal faces, minuscule mournful masks. By Signora Elias’s gate, tufts of wild poppies greeted Alba, and each day she visited, another unfurled its bloodsplat petals.

Shafts of morning light cut through Signora Elias’s large room and across the open piano lid, striking a golden gleam across its polished top. Alba could feel its heat trace her outline and light up her fingers. She looked down at the keys. Her fingers sprang into action.

Signora Elias interrupted at once. ‘You took a breath, yes, but it was high in your chest, snatched. You cannot expect to be able to keep up with this Bach fugue in this way. Bach is stamina, precision, absolute clarity. He is the source.’

Alba tilted her head back, blowing a puff of air out from her lower lip, which lifted a few strands of hair that had fallen onto her forehead.

‘And there’s no use in succumbing to frustration either. We can’t create or practise from that place. Sorrow? Yes. Feel the pain of those notes escaping from under you. Then simply work out what you must do to fix it.’

Alba wanted to say sorry, but the words stuck in her throat, a knot of silence.

‘Don’t apologize,’ Signora Elias continued, as always, intuiting what Alba longed to say but couldn’t, ‘this is the work, Alba. This is the constant reminder that you are merely human. What Bach is laying out for us is the entire cosmos, layers of mathematics, interweaving with glorious symmetry. Then he twists it in on itself, revelling in the asymmetry of those rules. It’s a kaleidoscope of patterns. We know this. So we honour this.’

Alba was accustomed to Signora Elias’s tempo increasing as she charged through her corrections, sometimes striding beside the piano, then drawing to a curt pause when the pinnacle of her thought was reached, a mountaineer charging towards the peak. She stood still now, in the spotlight of the sun’s glow. ‘Will you return to the beginning?’

‘Slower.’

‘And?’

Alba swallowed. ‘Then I’ll play these first few measures, repeating at speed, playing with alternate rhythms.’

Signora Elias raised her eyebrows, waiting for the end of the thought.

‘Until my fingers play me,’ Alba whispered.

‘Until there is no space between those patterns and you,’ Signora Elias added. ‘I don’t want to see Alba Fresu play with her fingers. I want to see the music ripple out of you. That’s when we know that you truly know the piece. When we have stripped it to its core, asked what it is, why it is, what it needs to tell us, and then step inside.’

Alba looked at Signora Elias and allowed herself to smile in spite of a sinking in her stomach. When would these exercises become instinctive?

‘It’s about learning to control every minute movement of your body to produce the precise tone the piece requires,’ Signora Elias began, ‘and then, in performance, being able to shift that focus on control alone, and simply allow your technique to be in place, so your musicality can soar. We want to hear the music, not the practice. Music is about control and the loss of it at the same time; a beautiful contradiction. At this moment, from your flushed cheeks I see you are still grappling with the sensations of losing control in the first instance.’

The past seven years Signora Elias had sat beside her each and every morning leading her down these waterways of her music. Now, at eighteen, as Alba approached her final year at school, their lesson together was a cool balm before class. After it, Signora Elias would permit her to practise unguided.

‘I want to apologize,’ Alba replied, her voice dry.

‘I know. Hold onto this thought – my corrections are leading you towards your music, Alba, they are never criticism alone, however it might feel.’

Signora Elias invited the silence for a moment, as if it were an unexpected yet welcome guest. Alba lost herself in it. Her breath dropped down into her abdomen, warm, deep. She felt her lower back unlock, each vertebra separating a little, rising up out of the top of her head. Her fingers lifted back onto the keys. As she exhaled, they became heavy, assured, curious. The first few measures tumbled out effortless, precise. Alba stopped, then began again, each time her breath deepening a little more, each time her feet finding the reassurance of the wooden parquet rise up to meet them. As the cascade of notes became equal, controlled, her hands began to relax, speeding up without tension. Her fingers sank into the ivories, weighted but free. The glorious symmetry of the sounds and patterns washed over her, shining light. She was no longer in Ozieri. She was far beyond the plains, above her turquoise coast. She was deep in the forests of Gennargentu, beneath a gushing waterfall, icy cold electrifying her body. She was everywhere but here. And the feeling lit her up from her feet and lifted up out of her head. She was inside her body and far beyond it at the same time.

The final run descended and landed, in perfect alignment, both hands announcing the last chord. The vibrations lifted out of the piano thinning to a faint blue glow somewhere in the air above the strings.

And then it was over.

She returned to a stark awareness of the room, once more a piano student surrounded by the landscape paintings on the wall around her, the promise of the spring morning outside sketching hope. She looked over at Signora Elias. Her eyes appeared wet, or perhaps it was the morning light, which caught a spiral dance of dust motes in the space between them.

‘You and I both know our lessons will reach their end after the summer. Your father has made it quite clear that you will be working at the officina. That will leave little or no time for you to be coming here.’

Alba nodded. The thought of the minutes ticking away towards a time when the piano wouldn’t be part of her daily life made Alba feel like she was suffocating.

‘It’s time at this crucial point in your training that you are allowed to perform. At the very least once. Every performance I gave taught me something I needed to learn, and stayed with me forever. I want to give you that.’

Alba felt her chest crease into a tight knot.

‘Don’t look so terrified, Alba. Perhaps in preparation you might play for my friend first? She is staying with me at the moment and her favourite thing is to listen to piano music. Would that be all right? After next lesson would be the perfect time.’

Alba nodded, though the idea sent a sliver of terror scorching through her.

Signora Elias looked into her. ‘When you practise in the way you have today, Alba, anything is truly possible. When you can acknowledge that fire and channel it with humility and passion, this instrument, and you, will sing.’

The next morning Signora Elias instructed Alba to use their lesson time to warm up and run through her repertoire. ‘Take all the time this morning to repeat whatever you need. What have I told you?’

‘A piece soars only when it’s shared.’

‘Why?’

‘Because it’s then that we find out what we really feel about it, how much careful time we’ve given it. Whether our practise has been well directed.’

‘Which, of course, it has. You have the most wonderful teacher, I hear.’

They laughed at that.

‘We’ll be down in a little while so you aren’t observed during practice. I have a gentleman coming to work on my car shortly, but he shouldn’t make too much noise; I’ll look out for him so he doesn’t ring the bell.’

‘Grazie, Signora Maestra.’

Signora Elias closed the door behind her as she left. The doorbell clanged soon after. ‘I spoke too soon! I’ll see to it, you carry on.’

She thought about the anticipation brewing in her house for Marcellino’s upcoming wedding. The way her mother insisted they practise her make-up. The way every breath of life seemed to be directed towards their first-born, the boy who could do no wrong, now set to marry the most beautiful young woman in town. The town was electric with the imminent nuptials. Alba was tired of the incessant talk of it after the first day back in the freezing fog of January, when all of a sudden, both families had agreed the marriage should go ahead sooner rather than later. Her mother clawed at her attention now, the picture of her demanding she return at a good hour today to help set up the luncheon with the closer family members as they sampled all the food the caterer was planning on providing. Giovanna, Grazietta and several other women would already be at their vignia now, setting up a long table in the one-room cottage, the wood heaving.

With a breath, Alba wiped her thoughts clear. In her mind’s eye, she pictured the surrounding vines, the gnarled rows that grew to eclipse the terror of what first happened there. The grapes had exorcised those memories and now the vignia would be the centre of more celebration for the boy who was kidnapped in place of his sister. She pictured the cottage behind her as she walked through the vines, down the hills towards the plains, across them, past the Nuragic towers, onto Lake Coghinas, its glassy surface urging her to step in. She imagined turning around in the water with the jagged mountains surrounding her, breathing in the juniper and toasted thyme air.

Her breath fell deep, down into the watery bed of her thoughts. Her hands lifted. Her fingers stretched along the piano keys. Her left hand began a wave rolling deep currents of passion and longing whilst her right soared above. She was a bird swooping towards the lake from above, ripples shooting out from the flick of her tail upon the crystal liquid. The music tugged her deeper into thoughtlessness. She was diving into her sea, unfathomable, powerful, free. Her skin flushed, her arms hot and fast as they stretched up and down the keys. Now she was the lover yearning to be understood, to be forgiven, to be heard, to be loved with every fibre, to be touched, tasted, savoured, honoured.

The door creaked. Her fingers lifted.

A shattering silence: Mario’s face was in the slit of the opening.

Splintering currents of electricity fractured the space between them. She felt naked. Stinging vulnerability crawled up her calves. He didn’t blink. Neither breathed.

He was the last person in town she would have liked to be spied on by. Now he had the ultimate arsenal for his incessant attacks. Alba snapped into panic. The person she trusted least was privy to the biggest betrayal of her parents. She sat, motionless in cloying dizziness, as if her feet were sticky in almond brittle before the tacky molten sugar sets.

Signora Elias and her friend swept in, and she watched Mario tumble a clumsy apology for being inside the house rather than outside with his father. The women closed the door behind them. Mario’s face disappeared.

Signora Elias’s friend was a reed. Long, thin, with an elegant bearing about her. A woman Alba desired not to cross. Yet as she spoke, her voice wove out like a clarinet, woody and warm. Her face lit up listening to Signora Elias, crinkling the wrinkles on her thin white skin deeper still. The many colours of her dress undercut her poise. Here were washes of blues and reds, a scarf swooped across her with a tropical print. Geometric earrings clasped her earlobes in colourful anarchy. She reached a hand out for Alba’s. The nails were painted fuchsia. Her hand was firm, unapologetic.

‘I’m Celeste. So very lovely to meet you, tesoro. Elena has told me so very much about you. I’m terribly excited to hear you play.’

Alba flushed, embarrassed by her embarrassment. She was about to play for a lady who appeared to value confidence and Alba wished she could find some. It was impossible, having just heard that Signora Elias had already spoken about her to a distinguished friend. It made their lessons at once less private. A secret had been divulged elsewhere too.

‘I would absolutely adore it if you would play?’ Celeste asked. Signora Elias turned towards her too. There was a different buoyancy to her this morning. Perhaps she was lonelier than Alba had thought?

‘Si,’ Alba replied. ‘Do you have a preference on which one I play first?’

‘Not at all,’ replied Signora Elias. ‘You must play what you feel is right for you this morning.’

Alba nodded. She scooted the stool a little way from the keys and rolled the knobs at the side up to where was comfortable. She’d never played for anyone else. Signora Elias was right. Doing so was the hardest thing. At once she was exposed, filled with doubt without knowing why. She turned back to Signora Elias, annoyed for seeking reassurance. Signora Elias responded with the calm and clarity Alba needed; an effortless smile, as if Alba playing for a stranger was the most natural thing to do this morning.

Alba took a breath. Mario’s face crisped into focus. She blew away the picture, though it remained at the fringes, like a spider’s sticky silk. ‘Clair de Lune’ was one of her favourite pieces. She allowed mind to be soothed by the fact. She began, fingers light, silver tones sparkling in a starry Sardinian night, silent, fragrant with sun-cooked rosemary and myrtle. She wove towards the midsection, letting her body move into the melody supporting her fingers. Mauves and violets replaced the metallic shimmer from the opening and then returned home, like waking from a dream. Alba lifted her fingers off, unhurried.

She turned towards the women.

Celeste was nodding her head. Signora Elias was a sunbeam.

‘My second piece is a Chopin.’

‘I should hope so too,’ replied Celeste with a twinkle.

The further two pieces wound out of Alba’s body like a story she’d lived and retold a thousand times. Then the final staccato of her last Bartók piece leaped off the soundboard with the perk of a vibrant orange. The energy of the frenetic rhythms hung in the air when she turned back to the women.

‘That’s all I have ready to share just now,’ said Alba, thrumming with a mixture of elation and relief.

‘No “just” about it, signorina,’ Celeste replied with a grin that stretched her thin crimson-painted lips. She stood up, wafting her silk kaftan behind her as she did so and planted two kisses on Alba’s cheeks.

‘And what, may I ask, do you intend to do with this talent? And the years of service my wonderful friend has invested in you?’

The question was so absurd Alba almost chuckled. Catching sight of the woman’s serious expression she stopped herself.

‘I don’t really know. I’m not sure how I could ever repay my debt.’

‘No debt to me, Alba,’ Signora Elias said. ‘Celeste is asking you whether you think you would pursue a life in music. Should you have the chance.’

Alba’s mouth opened then shut again.

‘You have undeniable talent, Alba,’ Celeste began. ‘You have a light inside you and it streams out when you play. It is unfettered. Unaffected. I listen to a great deal of young people play and very few have this, an affinity with the instrument. A respect. A lack of desire to be watched, but rather an ability to communicate with brutal honesty. Believe me when I tell you how rare that is.’

Alba longed for words, expression, something other than the numbing silence fogging her body.

‘When Signora Elias and I met at the Accademia of Santa Cecilia in Rome we were told the same thing.’

Signora Elias chuckled now.

‘It is a great responsibility – talent,’ Celeste said. ‘You were born with something to honour, nurture, share. And this fabulous woman Elias saw it right away. I can see that. She’s not as much of a fool as she looks, no?’

The women laughed in unison now. Celeste’s laughter tumbling out like a scale, Signora Elias’s voice warm, like papassini fresh from the oven.

‘It is so wonderful to meet you, Alba dear.’ Celeste stretched out her hands and held Alba’s. ‘Tell me one thing. How do you feel when you play?’

Alba took a breath. Signora Elias nodded.

‘I’ve never been asked really.’

‘I’m asking you now. And I want to see if you can be as honest with your answer as you are when you play.’

Alba let the words reach her like a lapping wave.