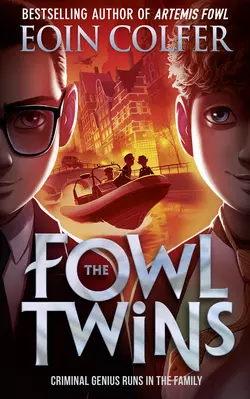

The Fowl Twins

Eoin Colfer

Criminal genius runs in the family… Myles and Beckett Fowl are twins but the two boys are wildly different. Beckett is blonde, messy and sulks whenever he has to wear clothes. Myles is impeccably neat, has an IQ of 170, and 3D prints a fresh suit every day – just like his older brother, Artemis Fowl. A week after their eleventh birthday the twins are left in the care of house security system, NANNI, for a single night. In that time, they befriend a troll on the run from a nefarious nobleman and an interrogating nun both of whom need the magical creature for their own gain... Prepare for an epic adventure in which The Fowl Twins and their new troll friend escape, get shot at, kidnapped, buried, arrested, threatened, killed (temporarily)... and discover that the strongest bond in the world is not the one forged by covalent electrons in adjacent atoms, but the one that exists between a pair of twins. The first book in the blockbusting new series from global bestseller Eoin Colfer.

First published in Great Britain by HarperCollins Children’s Books in 2019

Published in this ebook edition in 2019

HarperCollins Children’s Books is a division of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd,

HarperCollins Publishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

The HarperCollins Children’s Books website address is

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

Text copyright © Eoin Colfer 2019

Cover illustration © Petur Antonsson

Cover design copyright © HarperCollinsPublishers 2019

Eoin Colfer asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this ebook onscreen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008324810

Ebook Edition © November 2019 ISBN: 9780008324834

Version: 2019-10-03

For my sons, Finn and Seán, who are neither twins nor foul

Contents

Cover (#u0872ccb8-67f9-5f87-aecc-a91a4cd495ae)

Title Page (#u2ecf2d93-77fd-58a2-b40b-5d6dfcac68be)

Copyright (#u791cdf8e-1fc0-52ce-a27f-6eed10e7ee94)

Dedication (#ub255b30a-b4be-54da-8748-0aa502d17d4e)

Prologue

1. Meet the Antagonists (#u1c3179dc-c3e8-5696-a194-10cf3737fe22)

2. Mirror Ball (#u605e5e77-c916-574f-b19d-2624f98e3c5c)

3. Jeronima, not Geronimo (#ud0451efc-02bd-5c97-9ef3-52912234b508)

4. Operation Fowl Swoop (#uf5aa5ca8-14db-57a6-8151-545ff3589361)

5. Doveli (#litres_trial_promo)

6. Clippers and Lance (#litres_trial_promo)

7. Who Put the Dam in Amsterdam? (#litres_trial_promo)

8. Mr Circuits and Whoop (#litres_trial_promo)

9. Muy Inconveniente (#litres_trial_promo)

10. Vegas-Era Elvis (#litres_trial_promo)

11. Night Guard (#litres_trial_promo)

12. Concierge Level (#litres_trial_promo)

13. Nos Ipsos Adiuvamos (#litres_trial_promo)

14. Chomp (#litres_trial_promo)

15. The Sword and the Pen (#litres_trial_promo)

16. The Most Powerful Gull in Cornwall (#litres_trial_promo)

17. Farewell, Friends (#litres_trial_promo)

18. The Next Crisis (#litres_trial_promo)

Epilogue (#litres_trial_promo)

Keep Reading … (#litres_trial_promo)

Books by Eoin Colfer (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

(#uc5387964-3730-5416-92c4-ba1898e1f32c)

THERE ARE THINGS TO KNOW ABOUT THE world.

Surely you realise that what you know is not everything there is to know. In spite of humankind’s ingenuity, there are shadows too dark for your species to fully illuminate. The very mantle of our planet is one example; the ocean floor is another. And in these shadows we live. The Hidden Ones. The magical creatures who have removed ourselves from the destructive human orbit. Once, we fairies ruled the surface as humans do currently, as bacteria will in the future, but for now we are content for the most part to exist in our underground civilisation. For ten thousand years, fairies have used magic and technology to shield ourselves from prying eyes, and to heal the beleaguered Earth mother, Danu. We fairies have a saying that is writ large in golden tiles on the altar mosaic of the Hey Hey Temple, and the saying is this: WE DIG DEEP AND WE ENDURE.

But there is always one maverick who does not care a fig for fairy mosaics and is hell-bent on reaching the surface. Usually this maverick is a troll. And, specifically in this case, the maverick is a troll who will shortly and for a ridiculous reason be named Whistle Blower.

For here begins the second documented cycle of Fowl Adventures.

(#ulink_d51a111d-2c2e-543a-baf5-02fe4b3444fc)

THE BADDIE: LORD TEDDY BLEEDHAM-DRYE, THE DUKE OF SCILLY

IF A PERSON WANTS TO MURDER ANY member of a family, then it is very important that the entire family also be done away with, or the distraught survivors might very well decide to take bloody revenge, or at least make a detailed report at the local police station. There is, in fact, an entire chapter on this exact subject in The Criminal Mastermind’s Almanac, an infamous guidebook for aspiring ruthless criminals by Professor Wulf Bane, which was turned down by every reputable publisher but is available on demand from the author. The actual chapter name is ‘Kill Them All. Even the Pets’. A gruesome title that would put most normal people off reading it, but Lord Teddy Bleedham-Drye, Duke of Scilly, was not a normal person, and the juiciest phrases in his copy of The Criminal Mastermind’s Almanac were marked in pink highlighter, and the book itself was dedicated as follows:

To Teddy

From one criminal mastermind to another

Don’t be a stranger

Wulfy

Lord Bleedham-Drye had dedicated most of his one hundred and fifty-plus years on this green Earth to staying on this green Earth as long as possible, as opposed to being buried beneath it. In television interviews, he credited his youthful appearance to yoga and fish oil, but, in actual fact, Lord Teddy had spent much of his inherited fortune travelling the globe in search of any potions and pills, legal or not, that would extend his lifespan. As a roving ambassador for the Crown, Lord Teddy could easily find an excuse to visit the most far-flung corners of the planet in the name of culture, when in fact he was keeping his eyes open for anything that grew, swam, waddled or crawled that would help him stay alive for even a minute longer than his allotted three score and ten.

So far in his quest, Lord Teddy had tried every so-called eternal-youth therapy for which there was even the flimsiest of supporting evidence. He had, among other things, ingested tonnes of willow-bark extract, swallowed millions of antioxidant tablets, slurped litres of therapeutic arsenic, injected the cerebrospinal fluid of the endangered Madagascan lemur, devoured countless helpings of Southeast Asian liver-fluke spaghetti, and spent almost a month suspended over an active volcanic rift in Iceland, funnelling the restorative volcanic gas up the leg holes of his linen shorts. These and other extreme practices – never, ever to be tried at home – had indeed kept Bleedham-Drye breathing and vital thus far, but there had been side-effects. The lemur fluid had caused his forearms to elongate so that his hands dangled below his knees. The arsenic had paralysed the left corner of his mouth so that it was forever curled in a sardonic sneer, and the volcanic embers had scalded his bottom, forcing Teddy to walk in a slightly bow-legged manner as though trying to keep his balance in rough seas. Bleedham-Drye considered these secondary effects a small price to pay for his wrinkle-free complexion, luxuriant mane of hair and spade of black beard, and of course the vigour that helped him endure lengthy treks and safaris in the hunt for any rumoured life-extenders.

But Lord Teddy was all too aware that he had yet to hit the jackpot, therapeutically speaking, in regards to his quest for an unreasonably extended life. It was true that he had eked out a few extra decades, but what was that in the face of eternity? There were jellyfish that, as a matter of course, lived longer than he had. Jellyfish! They didn’t even have brains, for heaven’s sake.

Teddy found himself frustrated, which he hated, because stress gave a fellow wrinkles.

A new direction was called for.

No more small-stakes half measures, cribbing a year here and a season there.

I must find the fountain of youth,he resolved one evening while lying in his brass tub of electric eels, which he had heard did wonders for a chap’s circulation.

As it turned out, Lord Bleedham-Drye did find the fountain of youth, but it was not a fountain in the traditional sense of the word, as the life-giving liquid was contained in the venom of a mythological creature. And the family he would possibly have to murder to access it was none other than the Fowls of Dublin, Ireland, who were not overly fond of being murdered.

* * *

This is how the entire regrettable episode kicked off:

Lord Teddy Bleedham-Drye reasoned that the time-honoured way of doing a thing was to ask the fellows who had already done the thing how they had managed to do it, and so he set out to interview the oldest people on Earth. This was not as easy as it might sound, even in the era of worldwide-webbery and marvellous miniature communication devices, for many aged folks do not advertise the fact that they have passed the century mark lest they be plagued by health-magazine journalists or telegrams from various queens. But nevertheless, over the course of five years, Lord Teddy managed to track down several of these elusive oldsters, finding them all to be either tediously virtuous, which was of little use to him, or lucky, which could neither be counted on nor stolen. And such was the way of it until he located an Irish monk who was working in an elephant sanctuary in California, of all places, having long since given up on helping humans. Brother Colman looked not a day over fifty, and was, in fact, in remarkable shape for a man who claimed to be almost five hundred years old.

Once Lord Teddy had slipped a liberal dose of sodium pentothal into the Irishman’s tea, Brother Colman told a very interesting story of how the holy well on Dalkey Island had come by its healing waters when he was a monk there in the sixteenth century.

Teddy did not believe a word of it, but the name Dalkey did sound an alarm bell somewhere in the back of his mind. A bell he muted for the present.

The fool is raving,he thought. I gave him too much truth serum.

With the so-called monk in a chemical daze, Bleedham-Drye performed a couple of simple verification checks, not really expecting anything exciting.

First, he unbuttoned the man’s shirt, and found to his surprise that Brother Colman’s chest was latticed with ugly scars, which would be consistent with the man’s story but was not exactly proof.

The idiot might have been gored by one of his own elephants,Teddy realised. But Lord Bleedham-Drye had seen many wounds in his time and never anything this dreadful on a living body.

There ain’t no fooling my second test, thought Teddy, and with a flash of his pruning shears he snipped off Brother Colman’s left pinky. After all, radiocarbon dating never lied.

It would be several weeks before the results came back from the Advanced Accelerator Mass Spectrometer Laboratory, and by that time Teddy was back in England once again, lounging dejectedly in his bath of electric eels in the family seat: Childerblaine House, on the island of St George in the Scilly Isles. Interestingly enough, the island had been so named because, in one of the various versions of the St George legend, the beheaded dragon’s body had been dumped into Cornish waters and drifted out to the Scilly Isles, where it settled on a submerged rock and fossilised, which provided a romantic explanation for the small island’s curved spine of ridges.

When Lord Teddy came upon the envelope from AAMSL in his pile of mail, he sliced it open listlessly, fully expecting that the Brother Colman excursion had been a bally waste of precious time and shrinking fortune.

But the results on that single page made Teddy sit up so quickly that several eels were slopped from the tub.

‘Good heavens!’ he exclaimed, his halo of dark hair curled and vibrating from the eel charge. ‘I’m off to Dalkey Island, begorra.’

The laboratory report was brief and cursory in the way of scientists:

The supplied specimen, it read, is in the four-hundred- to five-hundred-year-old age range.

Lord Teddy outfitted himself in his standard apparel of high boots, riding breeches, and a tweed hunting jacket, all topped off with his old commando beret. And he loaded up his wooden speedboat for what the police these days like to call a stakeout. It was only when he was halfway across the Irish Sea in the Juventas that Lord Teddy realised why the name Dalkey sounded so familiar. The Fowl fellow hung his hat there.

Artemis Fowl.

A force to be reckoned with. Teddy had heard a few stories about Artemis Fowl, and even more about his son Artemis the Second.

Rumours,he told himself. Rumours, hearsay and balderdash.

And, even if the stories were true, the Duke of Scilly’s determination never wavered.

I shall have that troll’s venom,he thought, opening the V-12 throttles wide. And I shall live forever.

THE GOODIES (RELATIVELY SPEAKING)

DALKEY ISLAND, DUBLIN, IRELAND

THREE WEEKS LATER

Behold Myles and Beckett Fowl, passing a late summer evening on the family’s private beach. If you look past the superficial differences – wardrobe, spectacles, hairstyles and so on – you notice that the boys’ facial features are very similar but not absolutely identical. This is because they are dizygotic twins, and were, in fact, the first recorded non-identical twins to be born conjoined, albeit only from wrist to little finger. The attending surgeon separated them with a flash of her scalpel, and neither twin suffered any ill effects, apart from matching pink scars that ran along the outside of their palms. Myles and Beckett often touched scars to comfort each other. It was their version of a high five, which they called a wrist bump. This habit was both touching and slightly gross.

Apart from their features, the fraternal twins were, as one tutor noted, ‘very different animals’. Myles had an IQ of 170 and was fanatically neat, while Beckett’s IQ was a mystery, because he chewed the test into pulpy blobs from which he made a sculpture of a hamster in a bad mood, which he titled Angry Hamster.

Also, Beckett was far from neat. In fact, his parents were forced to take up Mindfulness just to calm themselves down whenever they attempted to put some order on his catastrophically untidy side of the bedroom.

It was obvious from their early days in a double cradle that the twins did not share similar personalities. When they were teething, Beckett would chew dummies ragged, while Myles chose to nibble thoughtfully on the eraser end of a pencil. As a toddler, Myles liked to emulate his big brother, Artemis, by wearing tiny black suits that had to be custom-made. Beckett preferred to run free as nature intended, and, when he finally did agree to wear something, it was plastic training pants, in which he stored supplies, including his pet goldfish, Gloop (named for the sound it made, or at least the sound the goldfish was blamed for).

As the brothers grew older, the differences between them became more obvious. Myles grew ever more fastidious, 3-D-printing a fresh suit every day and taming his wild jet-black Fowl hair with a seaweed-based gel that both moisturised the scalp and nourished the brain, while Beckett made zero attempt to tame the blond curls that he had inherited from his mother’s side of the family, and continued to sulk when he was forced to wear any clothes, with the exception of the only article he never removed – a golden necktie that had once been Gloop. Myles had cured and laminated the goldfish when it passed away, and Beckett wore it always as a keepsake. This habit was both touching and extremely gross.

Perhaps you have heard of the Fowl family of Ireland? They are quite notorious in certain shadowy circles. The twins’ father was once the world’s preeminent crime lord, but he had a change of heart and reinvented himself as a champion of the environment. Myles and Beckett’s older brother, Artemis the Second, had also been quite the criminal virtuoso, hatching schemes involving massive amounts of gold bullion, fairy police forces and time travel, to name but a few. Fortunately for more or less everyone except aliens, Artemis had recently turned his attention to outer space, and was currently six months into a five-year mission to Mars in a revolutionary self-winding rocket ship that he had built in the family barn. By the time the world’s various authorities, including NASA, APSCO, ALR, CNSA and UKSA, had caught wind of the project and begun to marshal their objections, Artemis had already passed the moon.

The twins themselves were to have many adventures, some of which would kill them (though not permanently), but this particular episode began a week after their eleventh birthday. Myles and Beckett were walking along the stony beach of a small island off the picturesque coast of South Dublin, where the Fowl family had recently moved to Villa Éco, a newly built, state-of-the-art, environmentally friendly house. The twins’ father had donated Fowl Manor, their rambling ancestral home, to a cooperative of organic farmers, declaring, ‘It is time for the Fowls to embrace planet Earth.’

Villa Éco was a stunning achievement, not least because of all the hoops the county council had made Artemis Senior jump through just for planning permission. Indeed, the Fowl patriarch had on several occasions considered using a few of his old criminal-mastermind methods of persuasion just to cut through the miles of red tape, but eventually he managed to satisfy the local councillors and push ahead with the building.

And what a building it was. Totally self-sufficient, thanks to super-efficient solar panels and a dozen geothermal screws that not only extracted power from the earth but also acted as the building’s foundation. The frame was built from the recycled steel yielded by six compacted cars and had already withstood a hurricane during construction. The cast-in-place concrete walls were insulated by layers of plant-based polyurethane rigid foam. The windows were bulletproof, naturally, and coated with metallic oxide to keep the heat where it should be throughout the seasons. The design was modern but utilitarian, with a nod to the island’s monastic heritage in the curved walls of its outbuildings, which were constructed with straw bales.

But the real marvels of Villa Éco were discreetly hidden until they were called upon. Artemis Senior, Artemis Junior and Myles Fowl had collaborated on a security system that would bamboozle even the most technically minded home invader, and an array of defence mechanisms that could repel a small army.

There was, however, an Achilles heel in this system, as the twins were about to discover. This Achilles heel was the twins’ own decency and their reluctance to unleash the villa’s defences on anyone.

On this summer evening, the twins’ mother was delivering a lecture at New York University with her husband in attendance. Some years previously, Angeline had suffered from what Shakespeare called ‘the grief that does not speak’,and, in an effort to understand her depression, had completed a mental-health doctorate at Trinity College and now spoke at conferences around the world. The twins were being watched over by the house itself, which had an Artemis-designed Nano Artificial Neural Network Intelligence system, or NANNI, to keep an electronic eye on them.

Myles was collecting seaweed for his homemade-hair-gel fermentation silo, and Beckett was attempting to learn seal language from a dolphin just offshore.

‘We must be away, brother,’ Myles said. ‘Bedtime. Our young bodies require ten hours of sleep to ensure proper brain development.’

Beckett lay on a rock and clapped his hands. ‘Arf,’ he said. ‘Arf.’

Myles tugged at his suit jacket and frowned behind the frames of his thick-rimmed glasses. ‘Beck, are you attempting to speak in seal language?’

‘Arf,’ said Beckett, who was wearing knee-length cargo shorts and his gold necktie.

‘That is not even a seal. That is a dolphin.’

‘Dolphins are smart,’ said Beckett. ‘They know things.’

‘That is true, brother, but a dolphin’s vocal cords make it impossible for them to speak in the language of a seal. Why don’t you simply learn the dolphin’s language?’

Beckett beamed. ‘Yes! You are a genius, brother. Step one, swap barks for whistles.’

Myles sighed. Now his twin was whistling at a dolphin, and they would once again fail to get to bed on time.

Myles stuffed a handful of seaweed into his bucket. ‘Please, Beck. My brain will never reach optimum productivity if we don’t leave now.’ He tapped the right arm of his black plastic spectacle frames, activating the built-in microphone. ‘NANNI, help me out. Please send a drobot to carry my brother home.’

‘Negative,’ said the house system in the strangely accented female voice that Artemis had selected to represent the AI. It was a voice that both twins instinctively trusted for some reason.

Myles could hear NANNI through bone-conduction speakers concealed in the arms of his glasses.

‘Absolutely no flying Beckett home, unless it’s an emergency,’ said NANNI. ‘Mother’s orders, so don’t bother arguing.’

Myles was surprised that NANNI’s sentences were unnecessarily convoluted. It seemed as though the AI were developing a personality, which he supposed was the point. When Artemis had first plugged NANNI into the system, so to speak, her responses were usually limited to one-word answers. Now she was telling him not to bother arguing. It would be fascinating to see how her personality would develop.

Providing NANNI doesn’t become too human, thought Myles, because most humans are irritating.

At any rate, it was ridiculous that his mother refused to authorise short-range flights for Beckett. In tests, the drone robots had only dropped the dummy Becketts twice, but his mother insisted the drobots were for urgent situations only.

‘Beckett!’ he called. ‘If you agree to come back to the house, I will tell you a story before bed.’

Beckett flipped over on the rock. ‘Which story?’ he asked.

‘How about the thrilling discovery of the Schwarzschild radius, which led directly to the identification of black holes?’ suggested Myles.

Beckett was not impressed. ‘How about the adventures of Gloop and Angry Hamster in the Dimension of Fire?’

Now it was Myles’s turn to be unimpressed. ‘Beck, that’s preposterous. Fish and hamsters do not even share the same environment. And neither could survive in a dimension of fire.’

‘You’re preposterous,’ said Beckett, and went back to his whistling.

The crown of Beck’s head will be burned by the evening UV rays, thought Myles.

‘Very well,’ he said. ‘Gloop and Angry Hamster it is.’

‘And Dolphin,’ said Beckett. ‘He wants to be in the story too.’

Myles sighed. ‘Dolphin too.’

‘Hooray!’ said Beckett, skipping across the rocks. ‘Story time. Wrist bump?’

Myles raised his palm for a bump and wondered, If I’m the smart one, why do we always do exactly what Beck wants us to?

Myles asked himself this question a lot.

‘Now, brother,’ he said, ‘please say goodnight to your friend, and let us be off.’

Beckett turned to do as he was told, but only because it suited him.

If Beckett had not turned to bid the dolphin farewell, then perhaps the entire series of increasingly bizarre events that followed might have been avoided. There would have been no nefarious villain, no ridiculously named trolls, no shadowy organisations, no interrogations by a nun (which are known in the intelligence community as nunterrogations, believe it or not) and a definite lack of head lice. But Beckett did turn, precisely two seconds after a troll had surged upwards through the loose shale at the water’s edge and collapsed on to the beach.

Fairies are defined as being ‘small, humanoid, supernatural creatures possessed of magical powers’, a definition that applies neatly to elves, gnomes, sprites and pixies. It is, however, a human definition, and therefore as incomplete as human knowledge on the subject. The fairies’ definition of themselves is more concise and can be found in the Fairy Book, which is their constitution, so to speak, the original of which is behind crystal in the Hey Hey Temple in Haven City, the subterranean fairy capital. It states:

FAIRY, FAERIE OR FAERY: A CREATURE OF THE EARTH. OFTEN MAGICAL. NEVER WILFULLY DESTRUCTIVE.

No mention of small or humanoid. It may surprise humans to know that they themselves were once considered fairies and did indeed possess some magic, until many of them strayed from the path and became extremely wilfully destructive, and so magic was bred out of humans over the centuries, until there was nothing left but an empath here and there, and the occasional telekinetic.

Trolls are classed as fairies by fairies themselves, but would not be so categorised by the human definition, as they are not magical – unless their longevity can be considered supernatural. They are, however, quite feral and only slightly more sentient than the average hound. Another interesting point about trolls is that fairy scholars of their pathologies have realised that trolls are highly susceptible to chemically induced psychosis while also tending to nest in chemically polluted sites, in much the same way as humans are attracted to the sugar that poisons them. This chemical poisoning often results in uncharacteristically aggressive behaviour and uncontrollable rage. Again, similar to how humans behave when experiencing sugar deprivation.

But this troll was not sick, sluggish or aggressive – in fact, he was in remarkable physical health, all pumping limbs and scything tusks, as he followed his second most powerful instinct: REACH THE SURFACE. (Trolls’ most powerful instinct being: EAT, GOBBLE, DEVOUR.)

This particular troll’s bloodstream was clear because he had never swum across a chromium-saturated lake and he had never carved out his burrow in mercury-rich soil. Nevertheless, healthy or not, this specimen would never have made it to the surface had the Earth’s crust under Dalkey Island not been exceptionally thin, a mere two and a quarter miles, in fact. This troll was able to squeeze himself into fissures that would have made a claustrophobe faint, and he wriggled his way to the open air. It took the creature four sun cycles of agonisingly slow progress to break through, and you might think the cosmos would grant the fellow a little good fortune after such Herculean efforts, but no, he had to pop out right between the Fowl Twins and Lord Teddy Bleedham-Drye, who was lurking on a mainland balcony and spying on Dalkey Island through a telescopic monocular, thus providing the third corner of an irresistible triangular vortex of fate.

So, the troll emerged, joint by joint, reborn to the atmosphere, gnashing and clawing. And, in spite of his almost utter exhaustion, some spark of triumph drove him to his feet for a celebratory howl, which was when Lord Teddy, for diabolical reasons which shall presently be explored, shot him.

Once the shot had been fired, the entire troll-related rigmarole really got rigmarolling, because the microsecond that NANNI’s sensors detected the bullet’s sonic boom, she dispensed with her convoluted sentences and without a word upgraded the villa’s alert status from beige to red, sounded the alarm klaxon, and set the security system to siege mode. Two armoured drobots were dispatched from their charging plates to extract the twins, and forty decoy flares were launched from mini mortar ports in the roof as countermeasures to any infrared guided missiles that may or may not be inbound.

This left the twins with approximately twenty seconds of earthbound liberty before they would be whisked into the evening sky and secured in the eco-house’s ultrasecret safe room, blueprints of which did not appear on any set of plans.

A lot can happen in twenty seconds. And a lot did happen.

Firstly, let us discuss the marksman. When I say Lord Teddy shot the troll, this is possibly misleading, even though it is accurate. He did shoot the troll, but not with the usual explosive variety of bullet, which would have penetrated the troll’s hide and quite possibly killed the beast through sheer shock trauma. That was the absolute last thing Lord Teddy wanted, as it would void his entire plan. This particular bullet was a gas-powered cellophane virus (CV) slug that was being developed by the Japanese munitions company Myishi and was not yet officially on the market. In fact, Myishi products rarely went into mass production, as Ishi Myishi, the founder and CEO, made quite a lot of tax-free dollars giving a technological edge to the world’s criminal masterminds. The Duke of Scilly was a personal friend and possibly his best customer and had most of his kit sponsored by Ishi Myishi so long as the duke agreed to endorse the products on the dark web. The CV bullets were known as ‘shrink-wrappers’ by the development team, and they released their viruses on impact, effectively wrapping the target in a coating of cellophane that was porous enough to allow shallow breathing but had been known to crack a rib or two.

And then there is the physicality of the troll itself. There are many breeds of troll. From the three-metre-tall behemoth Antarctic Blue, to the silent jungle killer the Amazon Heel Claw. The troll on Dalkey Island beach was a one-in-a-million anomaly. In form and proportion, he was the perfect Ridgeback, with the distinctive thick comb of spiked hair that ran from brow to tailbone, and the blue-veined grey fur on his chest and arms all present and correct. But this creature was no massive predator. In fact, he was a rather tiny one. Standing barely twenty centimetres high, the troll was one of a relatively new variety that had begun to pop up in recent millennia since fairies were forced deep in the Earth’s mantle. Much in the same way as schnauzer dogs had miniature counterparts known as toy schnauzers, some troll breeds also had their shrunken varieties, and this troll was one of perhaps half a dozen toy Ridgebacks in existence and the first to ever reach the surface.

Not at all what Lord Teddy had been expecting. Having seen Brother Colman’s scars, the duke had imagined his quarry to be somewhat larger.

When the little troll’s heat signature had popped up in his eyepiece like an oversized gummy bear, the duke had exclaimed, ‘Good heavens! Could that little fellow be my troll?’

It certainly matched Brother Colman’s description, except for the dimensions. In truth, the duke couldn’t help feeling a little let down. He had been expecting something more substantial. That diminutive creature didn’t look like it could manufacture enough venom to extend the lifespan of a gerbil.

‘Nevertheless,’ muttered the duke, ‘since I’ve come all this way …’

And he squeezed the trigger on his sniper’s rifle.

The supersonic cellophane slug made a distinctive yodelling noise as it sped through the air, and impacted the toy Ridgeback square in the solar plexus, releasing its payload in a sparkling globule that quickly sprawled over the tiny creature, wrapping it in a restrictive layer of cellophane before it could do much more than squeak in indignation.

Beckett Fowl spotted the cartwheeling toy troll, and his first impressions were of fur and teeth, and consequently his first thought was, Angry Hamster!

But the boy chided himself, remembering that Angry Hamster was a sculpture that he himself had constructed from chewed paper and bodily fluids and therefore not a living thing, and so he would have to revise his guess as to what this tumbling figure might be.

But by this time the troll had come to rest at his feet, and Beckett was able to snatch it up and scrutinise it closely, so there was no need for guessing.

Not alive, he realised then. Doll, maybe.

Beckett had thought the figure moved of its own accord, perhaps even made a squealing noise of some kind, but now he could see it was a fantasy action figure with a protective plastic coating.

‘I shall call you Whistle Blower,’ he whispered into the troll’s pointed ear. The boy had chosen this name after barely a second’s consideration, because he had seen on Myles’s preferred news channel that people who squealed were sometimes called whistle-blowers. Also, Beckett was not the kind of fellow who wasted time on decisions.

Beckett turned to show Myles his beach salvage, though his brother had always been a little snooty when it came to toys, claiming they were for children even though he was patently a child himself and would be for a few more years.

‘Look, brother,’ he called, waggling the action figure. ‘I found a new friend.’

Myles sneered as expected, and opened his mouth to pass a derogatory remark along the lines of, Honestly, Beck. We are eleven years old now. Time to leave childish things behind.

But his scorn was interrupted by a deafening series of honks.

The emergency klaxon.

It is true to say that there is hardly a more alarming sound than an alarm klaxon, heralding as it does the arrival of some form of disaster. Most people do not react positively to this sound. Some scream; some faint. There are those who run in circles, wringing their fingers, which is also pointless. And, of course, there are people who have involuntary purges, which shall not be elaborated upon here.

The reactions of the Fowl Twins could seem strange to a casual observer, for Myles discarded his seaweed bucket and uttered a single word: ‘Finally.’

While Beckett spoke to his new toy. ‘Do you hear that, Whistle Blower?’ he asked. ‘We’re going flying!’

To explain: designing the security system had been a fun bonding project for Myles, Artemis and their father, so Myles had a scientific interest in putting the extraction drobots through their paces, as thus far they had only been tested with crash dummies. Beckett, on the other hand, was just dying to be yanked backwards into the air at high speed and dumped down a security chute, and he fervently hoped the ride would last much longer than the projected half a minute.

Myles forgot all about getting to bed on time. He was in action mode now as the countermeasure flares fanned out behind his head like fireworks, painting the undersides of passing cumuli. NANNI broadcast a message to his glasses, and Myles repeated it aloud to Beckett in melodramatic tones that he knew his brother would respond to, as it made him feel like he was on an adventure. And also because Myles had a weakness for melodrama, which he was aware he should at least attempt to control, as drama is the enemy of science.

‘Red alert!’ he called. ‘Extraction position.’

The twins had been drilled on this particular position so often that Beckett reacted to the command with prompt obedience – two words that he would never find written on any of his school report cards.

Extraction position was as follows: chin tucked low, arms stretched overhead, and jaw relaxed to avoid cracked teeth.

‘Ten seconds,’ said Myles, slipping his spectacles into a jacket pocket. ‘Nine, eight …’

Beckett also slipped something into his pocket before assuming the position: Whistle Blower.

‘Three,’ said Myles. ‘Two …’

Then the boy allowed his jaw to relax and spoke no more.

The two drobots shot from under the villa’s eaves and sped unerringly towards the twins. They maintained an altitude of two metres from the ground by dipping their rotors and adjusting their course as they flew, communicating with each other through coded clicks and beeps. With their gears retracted, the drobots resembled nothing more than old propeller hats that children used to wear in simpler times as they rode their bicycles.

The drobots barely slowed as they approached the twins, lowering micro-servo-cable arms that lassoed the boys’ waists, then inflated impact bags to avoid injuring their cargo.

‘Cable loop in place,’ said Myles, lowering his arms. ‘Bags inflated. Most efficient.’

In theory, the ride should be so smooth that his suit would not suffer one wrinkle.

‘No more science talk!’ shouted Beckett impatiently. ‘Let’s go!’

And go they did.

The servo cables retracted smoothly to winch the twins into the air. Myles noted that there had been no discernible impact on his spine, and while acceleration was rapid – zero to sixty miles an hour in four seconds according to his smartwatch – the ride was not jarring.

‘So far so good,’ he said into the wind. He glanced sideways to see Beckett ignoring the flight instructions, waving his arms around as though he were on a roller coaster.

‘Arms folded, Beck!’ he called sternly to his brother. ‘Feet crossed at the ankles. You are increasing your own drag.’

It was possible that Beckett could not hear the instructions, but it was probable that he simply ignored them and continued to treat their emergency extraction like a theme-park ride.

The journey was over almost as soon as it began, and the twins found themselves deposited in two small chimney-like padded tubes towards the rear of the house. The drobots lowered them to the safe room, then sealed the tubes with their own shells.

NANNI’s face appeared in a free-floating liquid speaker ball, which was held in shape by an electric charge. ‘Perhaps this would be a good time to activate the EMP? I know you’ve been dying to try it.’

Myles considered this as he unclipped the servo cable. Villa Éco was outfitted with a localised electromagnetic-pulse generator, which would knock out any electronic systems in the island’s airspace. The Fowls’ main electronics would not be affected, as the entire villa had a Faraday cage embedded in its walls, and the Fowl systems had back-ups that ran on optical cable. A little old-school, but, should the cage fail, the cable would keep systems ticking until the danger was past.

‘Hmm,’ said Myles. ‘That seems a bit drastic. What is the nature of the emergency?’

‘Sonic boom detected,’ said NANNI. ‘I would guess from a high-powered rifle.’

NANNI is guessing now, thought Myles. She really is developing.

‘Guessing is of little use to me, madam,’ said Myles. ‘Scientists do not guess.’

‘Oh yes, that’s right. Scientists hypothesise,’said NANNI. ‘In that case, I hypothesise that the sonic boom was caused by a rifle shot.’

‘That’s better,’ said Myles. ‘How certain are you?’

‘Reasonably,’ replied NANNI. ‘If I had to offer a percentage, I would say seventy per cent.’

A sonic boom could be caused by many things, and the majority of those things were harmless. Still, Myles now had a valid excuse to employ the EMP, something he had been forbidden to do unless absolutely necessary.

It was, in fact, a judgement call.

Beckett, who had somehow become inverted in the delivery chute, tumbled on to the floor and asked, ‘Will the EMP hurt my insects?’

Beckett kept his extensive bug collection in the safe room so it would be safe.

‘No,’ said Myles. ‘Unless some of them are robot insects.’

Beckett pressed his nose to the terrarium’s glass and made some chittering noises.

‘No robots,’ he pronounced. ‘So activate the EMP.’

For once, Myles found himself in agreement with his brother. While the sonic boom could possibly be the by-product of a harmless event, it also might herald the arrival of an attack force hell-bent on wreaking vengeance on one Artemis or the other. Better to press the button and survive than regret not pressing it just before you died.

So, thought Myles, I should activate the EMP. But before I do …

Myles rooted in the steel rubbish bin until he found some aluminium foil that he had been using for target practice with one of his many lasers. He used it to quickly wrap his spectacles then stuffed them down to the bottom of the bin. This would protect the lite version of NANNI that lived in the eyeglasses in the event that both his safeguards failed.

‘I concur,’ said Myles. ‘Activate the EMP, NANNI. Tight radius, low intensity. No need to knock out the mainland.’

‘Activating EMP,’ said NANNI, and promptly collapsed in a puddle on the floor as her own electronics had not yet been converted to optical cable.

‘See, Beck?’ said Myles, lifting one black loafer from a glistening wet patch. ‘That is what we scientists call a design flaw.’

Lord Bleedham-Drye was doubly miffed and thrice surprised by the developments on Dalkey Island.

Surprise number one: Brother Colman spoke the truth, and trolls did indeed walk the Earth.

Surprise the second: the troll was tiny. Whoever heard of a tiny troll?

Surprise the last (for the moment): flying boys had sequestered his prey.

‘What on earth is going on?’ he asked no one in particular.

The duke muttered to himself, ‘These Fowl people seem prepared for full-scale invasion. They have flare countermeasures. Drones flying off with children. Who knows what else? Anti-tank guns and trained bears, I shouldn’t wonder. Even Churchill couldn’t take that beach.’

It occurred to Lord Teddy that he could blow up the entire island for spite. He was partial to a spot of spite, after all. But, after a moment’s consideration, he dismissed the idea. It was a cheery notion, but the person he would be ultimately spiting was none other than the Duke of Scilly, i.e. his noble self. He would hold his fire for now, but, when those boys re-emerged from their fortified house, he would be ready with his trusty rifle. After all, he was quite excellent with a gun, as his last shot had proven. Off the battlefield, it was unseemly to shoot anything except pheasant, unless one were engaged in a duel. Pistols at dawn, that sort of thing. But he would make an exception for a troll, and for those blooming Fowl boys.

Lord Teddy loaded the rifle with traditional bullets and set it on the balcony floor, muzzle pointed towards the island.

You can’t stay in that blasted house forever, my boys, he thought. And the moment you poke your noses from cover, Lord Teddy Bleedham-Drye shall be prepared.

He could wait.

He was prepared to put in the hours. As the duke often said to himself: one must spend time to make time.

Teddy lay sandwiched between a yoga mat and a veil of camouflage that had served as a hide of sorts for almost a month now, and ran a sweep of the island through his night-vision monocular. The whole place was lit up like a fairground with roaming spotlights and massive halogen lamps. There was not a millimetre of space for an intruder to hide.

Clever chappies, these Fowls, thought the duke. The father must have a lot of enemies.

Teddy sat up, fished a boar-bristle brush from his duffel bag, and began his evening ritual of one hundred brushes of his beard. The beard rippled and glistened as he brushed, like the pelt of an otter, and Teddy could not help but congratulate himself. A beard required a lot of maintenance, but, by heaven, it was worth it.

He had only reached stroke seven when the duke’s peripheral vision registered that something had changed. It was suddenly darker. He looked up, expecting to find that the lights had been shut off on Dalkey Island, but the truth was more drastic.

The island itself had disappeared.

Lord Teddy checked all the way to the horizon with his trusty monocular. In the blink of an eye, the entirety of Dalkey Island had vanished with only an abandoned stretch of wooden jetty to hint that the Fowl residence might ever have existed at the end of it.

Lord Bleedham-Drye was surprised to the point of stupefaction, but his manners and breeding would not allow him to show it.

‘I say,’ he said mildly. ‘That’s hardly cricket, is it? What has the world come to when a chap can’t bag himself a troll without entire land masses disappearing?’

Lord Teddy Bleedham-Drye’s bottom lip drooped. Quite the sulky expression for a hundred-and-fifty-year-old. But the duke did not allow himself to wallow for long. Instead, he set his mind to the puzzle of the disappearing island.

‘One can’t help but wonder, Teddy old boy,’ mused the duke to the mirror on the flat side of his brush, ‘if all this troll malarkey is indeed true, then is the rest also true? What Brother Colman said vis-à-vis elves, pixies and gnomes all hanging around for centuries? Is there, in fact, magic in the world?’

He would, Lord Teddy decided, proceed under the assumption that magic did exist, and therefore, by logical extension, magical creatures.

‘And so it is only reasonable to assume,’ Teddy said, ‘that these fairy chaps will wish to protect their own, and perhaps send their version of the cavalry to rescue the little troll. Perhaps the cavalry has already arrived, and this disappearing-island trick is actually some class of a magical spell cast by a wizard.’

The duke was right about the cavalry. The fairy cavalry had already arrived.

One fairy, at least.

But he was dead wrong about a wizard casting a spell. The fairy responsible for the disappearing-island trick was a far cry indeed from being a wizard, and could no more cast a spell than a frog could turn itself into a prince. She had made a split-second decision to use the only piece of equipment available to her, and was now pretty certain that her decision was absolutely the wrong one.

(#ulink_21bfb8b1-a40a-5e38-b5e7-7c06bcf89c09)

THE GNOME PROFESSOR DR JERBAL ARGON ONCE presented a theory, dubbed the Law of Diminishing Probabilities, to the fairy Psych Brotherhood. Argon’s law states that the more unusual the subjects involved in a conflict, the more improbable the resolution to that conflict will be. It is possibly the vaguest behavioural theory ever to make it into a journal, and it is really more of a notion than a law. But, in the case of the Fowl Twins’ first magical adventure, it would certainly prove to be accurate, as we will see from the hugely improbable finale to this tale.

The law’s requirements were certainly fulfilled, as this day was, without doubt, one for unusual individuals:

An immortalist duke …

A miniature troll …

And a set of fraternal human twins: the first a certified genius with a criminal leaning lurking in his prefrontal cortex, and the second possessed of a singular talent that has been hinted at but not fully explored as yet.

There are two additional unusual individuals still to join the tale. The nunterrogator, to whom we have already alluded, will presently make one of her trademark theatrical entrances. But the next unusual individual to join our cast of protagonists is more than simply unusual – she is biologically unique. And she made her appearance from above, hovering ten metres over Dalkey Island.

This unusual individual was Lower Elements Police Specialist Lazuli Heitz, who, five minutes earlier, entered the island’s airspace to complete a training manoeuvre in the Fowl safe zone. Usually such safe zones were in remote areas, but in rare cases where there was a special arrangement with the human occupants, a zone could be closer to civilisation and provide more of a challenge for the specialists. A case in point being Dalkey Island, where Artemis Fowl the Second, friend to the LEP, had guaranteed safe passage for fairies.

From a human perspective, Lazuli was unusual simply by virtue of being an invisible flying fairy, but, from a fairy perspective, LEP Specialist Heitz was unusual because she was a hybrid, that is to say a crossbreed. Hybrids are common enough among the fairy folk, especially since the families were forced into close quarters underground, but, even so, they are each and every one idiosyncratic, for all hybrids are as unique as snowflakes and the manifestation of their magical abilities is unpredictable.

In Lazuli Heitz’s case, her magic had resolutely refused to manifest itself in any shape or form. Lazuli’s particular category of hybrid was known as a pixel, that being a pixie–elf cross. There were other species in the ancestral DNA mix too, but pixie and elf accounted for over ninety-five per cent of her total number of nucleotides. And, even though both pixies and elves are magical creatures, not a single spark of power seemed to have survived the crossbreeding. In height, Specialist Heitz followed the pixie type at barely eighty centimetres tall, but her head adhered to the elfin model and was smaller than one might expect to see on a pixie’s shoulders, with the customary elfin sharp planes of cheekbone, jaw and pointed ear. This was enough to give her away as a hybrid to any fairy who cared to look. And, just in case there were any lingering doubt, Lazuli’s skin and eyes were the aquamarine blue of Atlantean pixies, but her hair was the fine flaxen blonde associated with Amazonian elves. Scattered across her neck and shoulders was a mottling of yellow arrowhead markings, which, according to palaeofatumologists, had once made Amazonian elves look like sunflowers to airborne predators.

Unless that elf is a hybrid with blue skin, Lazuli often thought, which ruins the effect.

All this palaeofatumological knowledge only meant one thing to Lazuli, and that was that her parents had probably met on holiday, which was about the sum total of her knowledge on that subject, apart from the fact that one or both of them had deserted her on the north corner of a public square, after which the orphanage administrator had named her Lazuli Heights.

‘I changed the spelling, and there you have it,’ the administrator had told her. ‘It’s my little game, which worked out well for you, not so much for Walter Kooler or Vishtar Restrume.’

The sprite administrator had a human streak and often made barbed remarks along the lines of: The lapis lazuli is a semi-precious stone. Semi-precious, hybrid. I think your parents must have been thinking along those lines, or you wouldn’t have ended up here.

The administrator chuckled drily at his own tasteless joke every single time he cracked it. Lazuli never even smiled.

It was exceedingly exasperating for a pixel not to possess the magical phenotypic trait, especially since her driving ambition was to achieve the rank of captain in the LEPrecon, a post where abilities such as the mesmer, invisibility and healing powers would most certainly prove to be boons. Fortunately for Heitz, her obdurate streak, sharp mind and dead eye with an oxalis pistol had so far carried her through two years of intense training in the LEP Academy and now to specialist duty in a safe zone. Lazuli did suspect that her Academy application might have been bolstered by the LEP’s minority-inclusion policy.

And Lazuli certainly was a minority. Her DNA profile breakdown was forty-two per cent elf, fifty-three per cent pixie and five per cent undeterminable. Unique.

The evening’s exercise was straightforward: fairies were secreted around the island, and it was her mission to track them down. These were not real fairies, of course. They were virtual avatars that could be tagged by passing a gloved hand through holograms projected by her helmet camera. There would be clues to follow: chromatographic reactions, tracks, faint scents, and a learned knowledge of the species’ habits. Once she punched in, Specialist Heitz would have thirty minutes to tag as many virtual fugitives as she could.

Before Lazuli could so much as repeat the mantra that had sustained her for many years and through several personal crises, which happened to be small equals motivated,a pulsating purple blob blossomed on her visor’s display.

This was most unusual. Purple was usually reserved for live trolls. Perhaps her helmet was glitching. This would not be in the least surprising, as Academy equipment was always bottom of the priority list when the budget was being carved up between departments. Lazuli’s suit was threadbare and ill-fitting, and packed with weapons that hadn’t been standard issue in decades.

She blinked at the purple blob to enlarge it and realised that there was indeed a troll on the beach, albeit a tiny one. The poor fellow was smaller than her, though he did not seem as intimidated by the human world as she was.

I must rescue him,Lazuli told herself. This was undoubtedly the correct action, unless this troll was involved somehow in a live manoeuvre. Lazuli’s angel mentor, who directed the exercise from Haven City, had explicitly and repeatedly ordered her never to poke her nose into an operation.

‘There are two types of fast track, Specialist Heitz,’ the angel had said only that morning. ‘The fast track to the top, and the fast track out the door. Poke your nose into an operation where it doesn’t belong, and guess which track you’ll be on.’

Lazuli didn’t need to guess.

A thought occurred to her: could it be that the coincidental appearance of a troll on this island was her stinkworm?

This was very possible, as LEP instructors were a sneaky bunch.

A specialist’s mettle was often stress-tested by mocking up an emergency and observing how the cadet coped. Rookies referred to this testing as beingthrown a stinkworm, because, as every fairy knew, if a person were thrown an actual stinkworm and they mishandled it, there would be an explosive, viscous and foul-smelling outcome. There was a legend in the Academy about how one specialist had been dropped into the crater of an apparently active volcano to see how he would handle the crisis. The specialist in question did not respond with the required fortitude and was now wanding registration chips in the traffic department.

Lazuli had no intention of wanding chips in traffic.

This could be my stinkworm,she thought.

In which case, she should simply observe, as her angel would be keeping a close eye.

Or it could be a genuine operation.

In which case, she should most definitely steer clear, as there would be LEP agents in play.

But there was a third option.

Option C: was it possible that the Fowls were running an operation of their own here? The human Artemis Fowl had a chequered history with the People.

If that were the case, then she should rescue the toy troll, who was perhaps three metres away from two children her facial-recognition software labelled as Myles and Beckett Fowl.

Lazuli hung in the air while she mulled over her options. Her angel had mentioned the name Artemis before the Dalkey Island exercise.

‘If you ever meet Artemis Fowl, he is to be trusted,’ she’d said literally minutes before Lazuli boarded her magma pod. ‘His instructions are to be followed without question.’

But her comrades in the locker room told a different story.

‘That entire family is poison,’ one Recon sprite had told her. ‘I saw some of the sealed files before a mission. That Fowl guy kidnapped one of our captains and made off with the ransom fund. Take it from me, once a human family gets a taste of fairy gold, it’s only a matter of time before they come back for more, so watch out up there.’

Lazuli had no option but to trust her angel, but maybe she would keep a close eye on the twins. Should she do more than that?

Observe, steer clear or engage?

How was a specialist supposed to tell a convincingly staged emergency from an actual one?

All this speculation took Lazuli perhaps three seconds, thanks to her sharp mind. After the third second, the emergency graduated to a full-blown crisis when a shot echoed across the sound and the little troll was sent tumbling with the force of the impact, landing squarely at the rowdy child’s feet. Beckett Fowl immediately grabbed and restrained the toy troll.

This effectively removed Specialist Heitz’s dilemma. It was just as her comrades had foretold: the Fowls were kidnapping a fairy!

An LEP operative’s first responsibility was to protect life, prioritising fairy life, and so now Lazuli was duty-bound and morally obliged to rescue the toy troll.

The prospect both terrified and thrilled her.

The first thing to do was inform her angel of the developing situation, even though radio silence was protocol during exercises.

‘Specialist Heitz to Haven. Priority-one trans-mission …’

If anyone had been on the other end of that transmission, they would have been left curious, because at that moment dozens of flares were launched from the house, and Specialist Heitz was forced to take evasive action to avoid being clipped. She had barely got her rig under control when there came a rumbling series of booms and Lazuli felt a wave of crackles pass through her body. The crackles were not particularly painful, but they did have the effect of shorting out her communicator along with every circuit and sensor in her shimmer suit. Lazuli watched in horror as her own limbs speckled into view.

‘Oh …’ she said, then fell out of the sky.

Not all the way down, fortunately, as Specialist Heitz’s suit launched its back-up operational system, which ran like clockwork because it was clockwork: a complicated hub of sealed gears and cogs ingeniously interlinked in a series of planetary epicyclic mechanisms that fed directly into a motor in Lazuli’s wing mounts.

Lazuli felt the legs of her jumpsuit stiffen and instinctively began to pedal before she hit the earth like an injured bird. The gears were phenomenally efficient, with barely a joule of energy loss thanks to the sealed hub, and so Specialist Heitz was able to reclaim her previous altitude with a steady mid-air pedal. But she was still quite plainly in the visible spectrum, looking for all the world like she was riding an invisible unicycle.

Though Lazuli’s spine had not been compacted by a high-speed impact with Dalkey Island, she still had the problem of how to effectively engage a sniper when she was operating under pedal power. If Lazuli attempted to approach the sniper, he could take potshots at his leisure.

Visibility was the problem.

So become invisible, Heitz.

But how to become invisible without any magic or even an operational shimmer suit?

There was a way, but it was neither foolproof nor field-tested, though it had been tried in somewhat raucous conditions, those being the communal area of the cadets’ locker room – inside lockers 28 and 29, to be precise. Lazuli knew this because she had witnessed the bullying, and lost ten grade points for repeating the experiment on the bully.

Lazuli reached into one of the myriad pockets in her suit and drew out a pressurised pod of chromophoric camouflage filaments held together by reinforced spider silk. The Filabuster, as it was known by LEP operatives, was rarely deployed, and in fact was due to be removed from duty kits in the next few months because of the unpredictability of its range, but now it was the only weapon in Lazuli’s arsenal that was actually of any use, as it had no electronic parts and came pre-primed.

The Filabuster operated on the same system that certain plants employ to disperse their seeds. The fibres inside the dried egg pull against each other to create tension, and when the silken cowl is ruptured the reflective filaments explode with considerable force, creating a visual distortion that can provide enough cover to cause momentary confusion.

But I need more than momentary confusion, Lazuli thought. I need to be invisible.

Which was where the locker-room antics came in. When a hulking demon cadet had forced a tiny pixie into his own locker and then tossed in an armed Filabuster, the pixie had emerged coated in filaments and practically invisible, and also, it turned out later, battered and bruised.

Perhaps this is not a good idea,thought Lazuli. Then she pulled the spider-silk ripcord before she could change her mind. Now there were approximately ten seconds before the silk surrendered to the internal pressure and exploded in a dense fountain of chromophoric filaments that would adjust to the region’s dominant colour, which ought to be the blue-black of the early evening Irish Sea.

‘D’Arvit,’ swore Lazuli in Gnommish, knowing that this experience was going to be, at the very least, quite unpleasant. ‘D’Arvit.’

But what were a few cuts and bruises in the face of a troll’s life?

Specialist Heitz hugged the Filabuster close to her body and went to her happy place, which was the cubicle apartment she’d recently rented on Booshka Avenue that she shared with one single plant and absolutely no people.

‘See you soon, Fern,’ she said, and then the Filabuster exploded with approximately ten times more force than the locker model.

The sensation was more kinetic than Specialist Lane had anticipated, and Lazuli instantly had more respect for the locker pixie who’d borne the torment without complaint. She felt as though she had been dropped into a nest of extremely irritable wasps that were not overly fond of hybrid fairies. The filaments clawed at every millimetre of her suit, more than a few managing to wiggle inside and tear her skin. This laceration was accompanied by a tremendous concussive force, which sent pedalling to the bottom of Lazuli’s list of priorities and sent the pixel herself tumbling to earth, with only the drag of doubledex wings to slow her down.

As she fell, Lazuli had the presence of mind to notice a ragged shroud of Filabuster filaments assemble around the small island, rendering it invisible to anyone outside the field.

Good, she thought. If I survive the fall, the camouflage filaments should hang around long enough to facilitate a toy-troll rescue.

Though perhaps her thoughts were not so lucid. Perhaps they were more as follows: Aaaargh! Sky! Rescue! D’Arvit!

Whichever the case, Specialist Heitz was correct: if she survived – which was a gargantuan if for a fairy without magic – then the Filabuster drape should afford her time to rescue the toy troll.

And it would have afforded her time if left undisturbed. Unfortunately, mere moments later, an army helicopter thundered over Sorrento Point, the downdraught from its rotors scattering the Filabuster curtain to the four winds. And, just as suddenly as Dalkey Island had disappeared, it returned to view.

Specialist Lazuli Heitz hit the earth hard. Technically she did not hit the earth itself, but something perched on top of it. Something soft and slimy that popped like bubblewrap as she sank through its layers.

Lazuli could have no way of knowing that her life had been saved by Myles Fowl’s seaweed fermentation silo. She ploughed her way through several slick levels before coming to a stop in the bottom third of the giant barrel, and in the moment before the seaweed covered her entirely she watched the lead helicopter hover above and noticed a black-clad figure standing right out on the landing skid, her skirt flapping in the rotor-generated wind.

Is that what the humans call a ninja? Lazuli wondered, trying to remember her human studies. But ninja was not the right word. What had come after ninja on the human occupations chart?

Not a ninja, she realised. It’s a nun.

Then the seaweed slid over Lazuli’s small frame, and, because the universe likes its little jokes, this felt almost exactly the same as being submerged in a brass tub of eels.

(#ulink_fd9fecc5-6252-5356-88a7-be5cf7cc9b3d)

INSIDE VILLA ÉCO’S SAFE ROOM, MYLES AND Beckett Fowl were experiencing a shared emotion – that emotion being confusion. Confusion was nothing new to either boy, but this was the first occasion on which they had felt it simultaneously.

To explain: as the twins were so dissimilar in everything except for physiognomy, it was not unusual for the actions of the one to confound the mind of the other. Myles had lost count of how many times Beckett’s attempted conversations with wildlife had bewildered his logical brain, and Beckett, for his part, was flummoxed on an hourly basis by his brother’s scientific lectures.

So, generally, one twin was lucid while the other was confused, but on this occasion they were mystified as a unit.

‘What’s happening, Myles?’ asked Beckett.

Myles did not answer the question, reluctant to admit that he couldn’t quite fathom what exactly was going on.

‘Just a moment, brother,’ he said. ‘I am processing.’

Myles was indeed processing, almost as quickly as the safe room’s processors were processing. NANNI’s gel incarnation may have been a puddle on the floor, but the AI itself was safe inside Villa Éco’s protected systems and was now replaying footage from a network of cameras slung underneath a weather balloon. These cameras were outside the Faraday cage and, unfortunately, had succumbed to the EMP, but before then they had managed to transmit the video to the Fowl server. NANNI had zeroed in on two points of interest. First, the AI located a dissipating bullet vapour trace and followed it back to the mainland to find that there was a camouflaged sniper there, a hirsute chap with an antique Russian Mosin-Nagant rifle, which would be over eighty years old, if NANNI were correct.

‘There’s the culprit,’ she said from a wall speaker. ‘A sneaky sniper near the harbour.’

This was not the source of Myles’s confusion, as the sonic boom had to have come from somewhere, and, after all, the Fowl family had many enemies from the bad old days. The fact that one enemy would employ an antique weapon could relate back to some decades-old vendetta having to do with any number of the twins’ ancestors, most probably Artemis Senior, who had once attempted to muscle in on the Russian mafia’s Murmansk market. This sniper might simply be on a revenge mission, and what better way to hurt the father than to target the sons?

The second point of interest, and the cause of Myles’s bewilderment, was another, much smaller figure that had been captured by one camera. The tiny creature had appeared out of thin air, pedalled to keep herself aloft and then plummeted into the seaweed silo.

Beckett’s confusion was more general in nature, but he did have one question as the brothers reviewed the balloon footage. ‘A pedalling fairy,’ he said. ‘But where’s her bicycle?’

Myles was not inclined to answer, but was inclined to disagree. ‘There’s no bicycle, brother mine,’ he snapped. ‘And I do not happen to believe in fairies or wizards or demigods or vampires. This is either photo manipulation or interference from a satellite system.’

He rewound the footage and froze the figure in the sky, stepping closer for a decent squint.

‘Magnify,’ he told his spectacles, which he had augmented with various lenses pillaged from his big brother’s sealed laboratory. Artemis had set a twenty-two-digit security code on his door that he did not realise Myles had suggested to him subliminally by whispering into his ear every night for a week as he slept. To add further insult, the numbers Myles had chosen could be decoded using a simple letter–number cipher to spell out the Latin phrase Stultus Diana Ephesiorum,which translated as Diana is stupid, Diana being the Roman version of the Greek goddess Artemis, for whom Artemis had been named. It was a very complicated and time-consuming prank, which, in Myles’s opinion, was the best kind.

‘Yes,’ said Beckett. ‘Magnify.’

And the blond twin accomplished his magnification simply by taking a step closer to the screen, which, in truth, was both more efficient and cost-effective.

Myles studied the suspended creature and it seemed clear that there was, at the very least, a possibility it was not human.

Beckett jabbed the wall screen with his finger, daubing it with whatever gunk was coating his hand at the time.

‘Myles, that’s a fairy on an invisible heli-bike. I am one million per cent sure.’

‘There is no such animal as a heli-bike and you can’t have a million per cent, Beck,’ said Myles absently. ‘Anyway, how can you be so sure?’

‘Remember Artemis’s stories?’ asked Beckett. ‘He told us all about the fairies.’

This was true. Their older brother had often tucked in the twins with stories of the Fairy People who lived deep in the earth. The tales always ended with the same lines:

The fairies dig deep and they endure, but, if ever they need to breathe fresh air or gaze upon the moon, they know that we will keep their secrets, for the Fowls have ever been friends to the People. Fowl and fairy, fairy and Fowl, as it is now and will ever be.

‘Those were stories,’ said Myles. ‘How can you be certain there is a drop of truth to them?’

‘I just am,’ said Beckett, which was an often-employed phrase guaranteed to drive Myles into paroxysms of indignant rage.

‘You just are? You just are?’ he squeaked. ‘That is not a valid argument.’

‘Your voice is squeaky,’ Beckett pointed out. ‘Like a little piggy.’

‘That is because I am enraged,’ said Myles. ‘I am enraged because you are presenting your opinion as fact, brother. How is one supposed to unravel this mystery when you insist on babbling inanities?’

Beckett reached into the pocket of his cargo shorts and pulled out a gummy sweet.

‘Here,’ he said, wiggling the worm at Myles as though it were alive. ‘This gummy is red and you need red, because your face is too white.’

‘My face is white because my fight-or-flight response has been activated,’ said Myles, glad to have something he was in a position to explain. ‘Red blood cells have been shunted to my limbs in case I need to either do battle or flee.’

‘That is soooo interesting,’ said Beckett, winking at his brother to nail home the sarcasm.

‘So the last thing I shall do is eat that gummy worm,’ declared Myles. ‘One of us has to be a grown-up eleven-year-old, and that one will be me, as usual. So, whatever I do in the immediate future, gummy-eating will not be a part of it. Do you understand me, brother?’

By which time Myles had actually popped the worm in his mouth and was sucking it noisily.

He had always been a sucker when it came to gummy sweets. In this case, he was a sucker for the gummy he was sucking.

Beckett gave him a few seconds to unwind, then asked, ‘Better?’

‘Yes,’ admitted Myles. ‘Much better.’

For, although he was a certified genius, Myles was also anxious by nature and tended to stress over the least little thing.

Beckett smiled. ‘Good, because a squeaky genius is a stupid genius. I dreamed that one time.’

‘That is a crude but accurate statement, Beck,’ said Myles. ‘When a person’s vocal register rises more than an octave, it is usually a result of panic, and panic leads to a certain rashness of behaviour untypical of that individual.’

But Myles was more or less talking to himself at this point, because Beckett had wandered away, as he often did during his twin’s lectures, and was peering through the safe room’s panoramic periscope’s eyepiece.

‘That’s nice, Myles. But you’d better stop explaining things I don’t care about.’

‘And why is that?’ asked Myles, a little crossly.

‘Because,’ said Beckett. ‘Helicopter.’

‘I know, Beck,’ said Myles, softening. ‘Helicopter.’

It was true that Beckett didn’t seem to either know or care about very many things, but there were certain subjects he was most informed about – insects being one of those subjects. Trumpets was another. And, also, helicopters. Beckett loved helicopters. In times of stress, he sometimes mentioned favourite items, but there was little significance to his helicopter references unless he added the model number.

‘A helicopter,’ insisted Beckett, making room for his brother at the mechanical periscope. ‘Army model Agusta Westland AW139M.’

Time to pay attention, thought Myles.

He propped his spectacles on his forehead and studied the periscope view briefly for visual confirmation that there was, in fact, a helicopter cresting the mainland ridge. The chopper bore Irish Army markings and therefore would not need warrants to land on the island, if that were the army’s intention.

And I cannot and will not fire on an Irish Army helicopter,Myles thought, even though it seemed inevitable that the army was about to place the twins in some form of custody. For most people, this knowledge would be a source of great comfort, but, historically, incarceration did not end well for members of the Fowl family, and so Father had always advised Myles to take certain precautions should arrest or even protective custody seem inevitable.

‘Give yourself a way out, son,’ Artemis Senior had said. ‘You’re a twin, remember?’

Myles always took what his father said seriously, and so he regularly updated his Ways Out of Incarcerationfolder.

This calls for a classic,he thought, and said to his brother, ‘Beck, I need to tell you something.’

‘Is it story time?’ asked Beckett brightly.

‘Yes,’ said Myles. ‘That’s precisely it. Story time.’

‘Is it one of Artemis’s? The Arctic Incident or The Eternity Code?’

Myles shook his head. ‘No, brother, this is a very important story, so you will need to concentrate. Can you achieve a high level of focus?’

Beckett was dubious, for Myles often declared things to be important when he himself regarded them as peripheral at best.

For example, some of the many things Myles considered important:

1 Science

2 Inventing

3 Literature

4 The world economy

And things Beckett considered hugely important, if not vital:

1 Gloop

2 Talking to animals

3 Peanut butter

4 Expelling wind, however necessary, before bed

Rarely did these lists overlap.

‘Is this important to me, or just big brainy Myles?’ Beckett asked with considerable suspicion. This was a most exciting day, and it would be just like Myles to ruin it with common sense.

‘Both of us, I promise.’

‘Wrist-bump promise?’ said Beckett.

‘Wrist-bump promise,’ said Myles, holding up the heel of his hand.

They bumped and Beckett, satisfied that a wrist-bump promise could never be broken, plonked himself down on the giant beanbag.

‘Before I tell you the story,’ said Myles, ‘we must become human transports for some very special passengers.’

‘What passengers?’ asked Beckett. ‘They must be teeny-tiny if we’re going to be the transports.’

‘They are teeny-tiny,’ said Myles, not entirely comfortable using such a subjective unit of measurement as teeny-tiny,but Beckett had to be kept calm. He opened the Plexiglas door on top of the insect hotel and scooped out a handful of tiny jumping creatures. ‘I would even go so far as to say teeny-weeny.’

‘I thought we weren’t supposed to touch these guys,’ said Beckett.

‘We’re not,’ said Myles, dividing the insects between them. ‘Except in an emergency. And this is most definitely an emergency.’

It took a mere two minutes for Myles to relate his story, which was, in fact, an escape plan, and an additional six minutes for him to repeat it three times so Beckett could absorb all the particulars.

Once Beckett had repeated the details back to him, Myles persuaded his twin to don some clothing, namely a white T-shirt printed with the word UH-OH!, a phrase often employed both by Beckett himself upon breaking something valuable, and also by people who knew Beckett when they saw him approach. Myles even had time to disable the villa’s more aggressive defences, which might decide to blow the helicopter out of the sky with some surface-to-air missiles, before the knock came on the door.

Here comes the cavalry,thought Myles.

In this rare instance, Myles Fowl was incorrect. The woman at the door would never be mistaken for an officer of the cavalry.

She was, in fact, a nun.

‘It’s a nun,’ said Beckett, checking the intercom camera.

Myles confirmed this with a glance at the screen. It was indeed a nun who appeared to have been winched down in a basket from the hovering helicopter.

If we do nothing, she might go away, thought Myles. After all, perhaps this person doesn’t even know we’re here.

Myles should have voiced this thought instead of thinking it, for, quick as a flash, Beckett pressed the TALK button and said, ‘Hi, mysterious nun. This is Beckett Fowl speaking, one of the Fowl Twins. My brother Myles is here too, and we’re home alone. We’ll be with you in a minute – we’re down in the safe room because of the sonic boom. I’m so glad the EMP didn’t kill your helicopter.’

Beckett’s statement contained basically every scrap of information that Myles had wanted to keep secret.

‘Gracias,’ said the unexpected nun. ‘I shall await your arrival.’

Beckett was hopping with excitement. ‘Myles, it’s a nun with a helicopter! You hardly ever see that. This is the start of our first real adventure. It has to be – I can feel it in my elbows.’

Beckett often felt things in his elbows, which he claimed were psychic. He sometimes pointed them at cookie jars to see if there were cookies inside, which Myles had never considered much of a challenge, as one of NANNI’s robot arms filled the kitchen containers as soon as their smart sensors informed the network they were empty.

‘Beck, with no disrespect to your extrasensory elbows,’ said Myles, ‘why don’t we stay calm and stick to the plan? If we can stay, we stay, but, if we go, remember the story.’

Beckett tapped his forehead. ‘It’s all in here, brother. Angry Hamster in the Dimension of Fire.’

‘No, Beck!’ snapped Myles. ‘Not that story.’

‘Ha!’ said Beckett. ‘You snapped at me. I win.’

Myles counted up to ninety-seven in prime numbers to calm himself. One of Beckett’s pleasures in life was teasing his brother until he snapped. It was unfair, really, as it was very difficult to tell the difference between a Beckett who genuinely didn’t know something and a Beckett who was pretending not to know something.