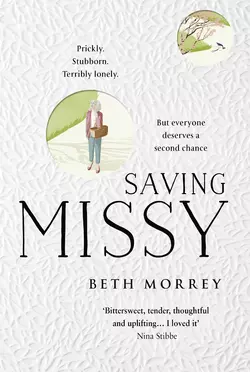

Saving Missy

Beth Morrey

Prickly. Stubborn. Terribly lonely. But everyone deserves a second chance… A dazzling debut for 2020 – are you ready to meet Missy Carmichael? Missy Carmichael’s life has become small. Grieving for a family she has lost or lost touch with, she’s haunted by the echoes of her footsteps in her empty home; the sound of the radio in the dark; the tick-tick-tick of the watching clock. Spiky and defensive, Missy knows that her loneliness is all her own fault. She deserves no more than this; not after what she’s done. But a chance encounter in the park with two very different women opens the door to something new. Another life beckons for Missy, if only she can be brave enough to grasp the opportunity. But seventy-nine is too late for a second chance. Isn’t it? ’Bittersweet, tender, thoughtful and uplifting … I loved it’ Nina Stibbe

Copyright (#uaca527fe-9ac8-5623-9d78-92ec8ef5690c)

Published by HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London, SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

First published in the UK by HarperCollinsPublishers 2020

Copyright © Beth Morrey

Jacket design by Claire Ward. Illustration © Stefania Infante/Richard Solomon Artists

Beth Morrey asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008334024

Ebook Edition © February 2020 ISBN: 9780008334048

Version: 2019-10-15

Dedication (#uaca527fe-9ac8-5623-9d78-92ec8ef5690c)

To Mum, Dad and Ben – my first oikos

Epigraph (#uaca527fe-9ac8-5623-9d78-92ec8ef5690c)

Every heart sings a song, incomplete, until another heart whispers back.

Attributed to Plato

Contents

Cover (#u1d0ff6c4-8e56-503c-93d4-9dc070f0155a)

Title Page (#ud944e2c9-42d6-5e0e-be7c-e61c17019ce4)

Copyright

Dedication

Epigraph

PART 1

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

PART 2

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

PART 3

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Chapter 31

Chapter 32

PART 4

Chapter 33

Chapter 34

Chapter 35

Chapter 36

Chapter 37

Chapter 38

Chapter 39

Chapter 40

Chapter 41

Chapter 42

Chapter 43

Chapter 44

Chapter 45

Chapter 46

Chapter 47

Chapter 48

Chapter 49

Acknowledgements

About the Author

About the Publisher

PART 1 (#uaca527fe-9ac8-5623-9d78-92ec8ef5690c)

‘Let your hook always be cast; in the pool where you least expect it …’

Ovid

Chapter 1 (#uaca527fe-9ac8-5623-9d78-92ec8ef5690c)

It was bitterly cold, the day of the fish-stunning. So bitter that I nearly didn’t go to watch. Lying in bed that morning, gazing at the wall since the early hours, I’d never felt more ancient, nor more apathetic. So why, in the end, did I roll over and ease those shrivelled feet of mine into my new sheepskin slippers? A vague curiosity, maybe – one had to clutch on to that last vestige of an enquiring mind, stop it slipping away.

Still in my dressing gown, I shuffled about the kitchen making tea and looking at my emails to see if there were any from Alistair. Well, my son was busy, no doubt, with his fieldwork. Those slippers he bought me for Christmas were cosy in the morning chill. There was a message from my daughter Melanie but it was only to tell me about a documentary she thought I might like. She often mistook her father’s tastes for mine. I ate dry toast and brooded over my last conversation with her and for a second bristles of shame itched at the back of my neck. It felt easier to ignore it, so instead I read the newspapers online and saw that David Bowie had died.

At my age, reading obituaries is a generational hazard, contemporaries dropping off, one by one; each announcement an empty chamber in my own little revolver. For a while I tried to turn a blind eye, as if ignoring death could somehow fob it off. But people kept dying and other people kept writing about it, and some perverse imp obliged me to keep up to date. Bowie’s death upset me more than most, although I never really listened to his music. I did remember him introducing the little animation of The Snowman, but when we watched it with my grandson at Christmas they’d replaced the introduction with something else. So my one recollection of Bowie was him holding a scarf and looking sombre, and for some reason the image was a disturbing one. The unmade bed beckoned, but then Leo’s voice in my head as it so often was, ‘Buck up, Mrs Carmichael! Onwards and upwards!’

So I went up to my room to put on my thickest pair of tights and a woollen skirt, grimacing at the putrid blue veins, and creaking along with the stairs on the way back down to fetch my coat. Struggling with the buttons, I sat down for a moment to catch my breath, thinking about the sign in the park the previous week.

My post-Christmas slump was particularly bad this year, the warm glow of festivities punctured by Alistair’s departure, and with him Arthur, my golden grandson, his voice already taking on the Australian upward lilt. And it was still hard, being in the park, without remembering Leo. He was a great believer in a constitutional; enjoyed belittling self-important joggers and jovially berating cyclists. Every landmark had a dismal echo, but I was drawn back again all the same – the resident grey lady, idly roaming. There was a certain oak tree we used to visit – Leo liked its gnarled old trunk and said it was a Quercus version of him, increasingly craggy in old age. I would no doubt have spent hours standing there wool-gathering that day, but was distracted by a child who sounded like my Arthur. A boy of his age was tugging his mother fretfully as she read a notice pinned to the railings that circle each lake. Moving closer, I pretended to read it.

‘Mummmmmeeeeeeee!’ He had strawberry blonde locks and biscuit crumbs at the corner of his mouth that begged to be wiped away. Children are so beautiful, flawless and shiny, like a conker newly out of its shell. Such a shame they all grow up to be abominable adults. If only we could preserve that giddy-with-possibility wiring, everything greeted with an open embrace.

‘Jeez, Otis, give me a break,’ said the mother, in a broad Irish accent, batting him off. She had dyed red hair and I loathed her instantly. She glanced sideways at me, the old crone leering at her son, and I resumed my faux-study of the notice.

‘What do you think, Oat?’

Oat? Good Lord, people today.

‘They’re gonna electrocute the fish! Wanna watch?’

The park caretakers needed to move the fish from one lake to the other, which required them to be stunned. Electrofishing. I’d never seen or heard of such a thing, nor did it seem particularly interesting, but maybe if I could see ‘Oat’ again then the tightness I’d felt in my gullet since Ali and Arthur got on the plane might ease a little. It would be something to do, after all …

Since that afternoon a week ago, I’d changed my mind half a dozen times, dwelling on the decision as only the terminally bored and insecure can. In the end, I decided to go so that there would be something to tell Alistair about. My life had become so circumscribed I’d grown worried he might think me trivial, and I only read the papers (including the obituaries) so that I knew what he was talking about when he mentioned a politician’s gaffe, or asked which new plays were on in the West End. I could tell Ali was impressed when I went to the Turner exhibition, so the three buses in the rain were worth it.

Seeing some carp get electrocuted wasn’t quite the dazzling metropolitan excursion, but it was better than nothing. So there I was, off to see the fish-stunning in my best winter coat, already drafting the email I would write on my return. Perhaps I might bump into little Otis and feed the ducks with him and queue up with his mother for a coffee, and … I ran adrift at this point, and nearly turned back, but by then my legs were stiffening up in the cold, and the bench by the lakes was nearest.

A small group had gathered to watch. Someone was handing out croissants, and when one was offered I took it, not because I was hungry but just grateful to be noticed. I put it to my lips and remembered a time in Paris with Leo when we’d had pain au chocolat on the banks of the Seine and then went to a bookshop where he’d disappeared up a rickety staircase while I petted a cat curled on a battered sofa, picked shards of pastry out of my teeth and worried which hand I was using to do which. They smelt of chocolate and cat for the rest of the day because we couldn’t find anywhere to wash. My eyes filled with tears: Leo and I would never go to Paris again, even though it wasn’t a particularly pleasant memory as I found the city dirty and unfriendly, there were no green spaces, and despite Leo speaking fluent French, they used to curl their lips at him because he never sounded anything but English and as puffed up as their croissants.

I swayed and sank onto the bench, blinking and fighting the breathlessness, until a warm patrician voice said, ‘Oh my love, don’t look so horrified – they’re not Greggs or anything. I made them myself.’ A middle-aged woman with eyes like berries was smiling down at me, waving a napkin, so I made a show of nibbling the croissant and mumbling my thanks, cursing myself for being such a distracted old bat. She carried on moving through the crowd, handing out her pastries and pleasantries, then everyone surged forwards, so I struggled to my feet again, to watch two men in waders and lurid jackets sailing across the pond in a curious-looking boat.

About four feet off the bow hung a circular contraption with small bars dangling from it into the water, like a giant set of wind chimes. Next to me, a chap was explaining the process to the woman on his other side. The device worked in combination with a conductor on the hull to create an electrical field in the water wherever the boat travelled, with an on-board lever controlling the current. The men made large circles around the lake, one steering and operating the electrical lever while the other knelt poised with a net. For a while nothing happened, but then a glistening grey buoy popped gaily to the surface – the first stunned fish. ‘Ooooh,’ said the onlookers, clapping politely. After that they started bobbing up everywhere, gleaming and flaccid, waiting to be fished out. Every time the second man scooped one up, the watching crowd cheered and clinked their paper cups of mulled wine.

But the longer it went on, the more unsettling it became. The rhythmic ‘plash’ as they juddered out of the water, the slow whoosh of the net, the resulting thud as they hit the container. Plash, whoosh, thud. Plash, whoosh, thud. Then … flap. The stunning only lasted long enough to get the fish into the boat. Those vast, prehistoric-looking carp, covered in pond-mud, were hauled on board and immediately started writhing and flopping. Plash, whoosh, thud, plash whoosh, thud. Flap, flap, flap.

One minute you’re gliding along, not a care in the world, and the next a huge prod appears and knocks you for six, and then everything is different and you’re gasping with the shock of it. And there’s no triumph in survival, because you’re just swimming round and round endlessly in a new lake, mouthing pointlessly. I’d rather someone put me out of my misery. Ashes to ashes. The breathlessness, back. Plash, whoosh, thud. I could look the other way, then it would go away. Don’t think, don’t think. Thud, thud, thud. I clutched the railings, trying to ignore the looming branches above, but my skin prickled around the edges, flared, and I felt myself fall amidst reaching hands and faraway shouts as the blackness took over …

Chapter 2 (#uaca527fe-9ac8-5623-9d78-92ec8ef5690c)

Something rough was rubbing against my cheek, moving up my face like a scourer. Moaning, I turned my head away.

‘She’s coming round, move back!’

The scourer was back, rough and warm, with sour breath behind it. I could feel my nose wrinkle as the stench flooded my nostrils.

‘Give her some air! Nancy, get away with you!’

Reaching out feebly, I encountered a handful of fur. Then felt the scourer on my hand. A tongue. I pushed it away and moaned again.

I must have been a bit under the weather, because when I finally came to I was lying on the bench and the woman with the berry eyes and pastries was holding a wet napkin to my forehead, onlookers peering around her shoulders. Struggling to the surface, clammy and astray, I could still feel the link with whatever underworld I’d been to, and closed my eyes again, hoping they would all go away.

‘Gosh, you took a bit of a turn, my love,’ the woman said, holding my wrist. ‘I don’t have a clue what I’m doing with this pulse nonsense,’ she continued, jiggling my hand gently. ‘What’s right, after all? Seventy, eighty? I don’t know. No, don’t get up just yet.’

‘Oh no, I’m fine, really.’ I heaved my legs off the bench. ‘Sorry to be such a bother, I don’t know what came over me.’ The darkness was receding, replaced by the equally cold sweat of embarrassment. My cheek and hand were coated in some sort of sticky substance and there was that urge to go and wash it off.

‘Probably the weather, sweetie. It’s a bit parky, isn’t it? Let’s just sit for a moment and look at the trees. Aren’t they beautiful? Would you like another croissant? Go on, build up your strength. I’m Sylvie, by the way. And these two are Nancy and Decca.’

Still dazed, I realized she was indicating two small dove-blue dogs prancing round her feet. As she sat down on the bench next to me they jumped up either side of her, and I had to shift along to make room, wiping the back of my hand on my skirt. We sat eating croissants, looking up at the trees, and they were rather beautiful in a bleak way, stark and spiky against the pearly sky, with weak sunlight clawing through the clouds and dappling on the lake. The crowd had dispersed, although the men continued to circle, scooping the last of the fish.

‘Something toxic in the water, apparently,’ remarked Sylvie, nodding towards the lake. ‘I do hope they survive the experience. Who’s Leo, by the way? Your son? Would you like someone to fetch him?’

Leo.

I would have liked nothing more. Someone to go and fetch him, bring him back to me. He’d march up, take my hand, say, ‘Missy! What have you been up to, silly old girl?’ And we’d walk home together and light a fire to ward off the cold. The tears came again and I dabbed them away, the drops warm on my white fingers.

‘I’m sorry,’ said Sylvie, patting and squeezing my icy hand. ‘I shouldn’t have asked. You said his name, and I thought, maybe … Anyway, let’s just sit here awhile, shall we? No hurry.’

So we sat, mostly in silence, but sometimes Sylvie would point out a plant or bird or dog of note, and I was able to reply adequately without worrying I was boring her or saying the wrong thing. Then I finished my croissant and dusted off the flakes, ready to get up and say goodbye to this easy, undemanding woman who had been the first stranger to speak to me in weeks. Best to end the conversation before I wanted to instead of after she did.

‘Thank you so much,’ I said, awkwardly holding out my still-sticky hand. ‘So kind, but I must be going …’

‘Bollocks, we missed it.’

We both turned to see Otis’s red-haired mother dragging her sulking son down the path between the lakes. He was wearing a cape and had hooked a shield over the handlebars of his scooter, his russet hair sticking out in different directions. I wanted to smooth it down, then ruffle it up again.

‘See, I told you they’d die without us,’ she huffed, shouldering an enormous over-stuffed bag and leaning down to fondle the dogs.

‘Angela, love,’ said Sylvie. ‘Late as ever. Fancy a coffee? I was just about to ask … um …? She turned to me expectantly.

‘Millicent,’ I murmured, scarcely able to believe my luck. Would it be all right to say yes? Surely I deserved a treat? But it wouldn’t do to look too eager.

‘Millicent … to join us.’

Angela sighed and hefted her bag again. ‘Go on, then. But I wanted to see some fish being killed. So did Otis, but he couldn’t find his Spider-Man outfit, daft beggar.’

‘Millicent, would you like to come and have a coffee with us? Or tea – don’t want to get dictatorial about beverages!’ Sylvie’s eyes crinkled engagingly as she linked arms with Angela and held out her hand to Otis.

They seemed such a merry little band. Of course they didn’t want a fuddy-duddy like me tagging along and slowing them down, so I said I had an appointment to get to, which was true in a way, and watched them walk down the avenue towards the café. The sky cleared a bit more as I headed off, feeling cheered by my outing. At least they asked. I told Leo about it, exaggerating some of the details to make it sound more dramatic. But of course it didn’t matter which way I told it, there was no one there to listen, so after leaving some flowers and tidying up, I left for my empty home.

Back in my kitchen, there was the tick-tick-tick of the clock, with no other sound to drown it out, and in the living room Leo’s chair was empty, and I didn’t have any new friends – I would never see Sylvie or Angela or Otis again, and would have to avoid the park now in case they thought I was trying to run into them.

I cleaned the house and remembered when we had young children and it was impossible to keep anything tidy. Now everything was spotless, and stayed that way. Eating an over-boiled egg for my lunch, I read more about David Bowie, and thought of the scarf and The Snowman. I had made Arthur a scarf for Christmas, forgetting that it was summer in Sydney, and now the knitting needles just rolled around my cutlery drawer, reminding me of my mistake. Later, I couldn’t be bothered with making dinner so just had cereal and thought about watching television, maybe that documentary, but really, what was the point? Alistair watched Australian television now, bought me Australian slippers. I turned in early, checking the cupboards and shivering as I got into bed, waiting for the blankets to warm up. ‘Sibyl told me … before she died. I don’t think she knew what she was saying.’ I blinked to banish the image of my daughter Melanie, wide-eyed in my kitchen, backing away. The guilt gnawed away at me, as it had since that terrible day. Whenever I tried to weed it out, it just took a deeper root.

So the day ended as miserably as it began. But I still felt it somewhere – that spark. The beginning of something. Or the end. Who knows?

Chapter 3 (#uaca527fe-9ac8-5623-9d78-92ec8ef5690c)

‘Come closer, Missy.’

Kensington, 1942, and impervious to the booms above, Fa-Fa bent to light the spill on one of the candles, cupping huge hands around his pipe and puffing away to get it going. With each inward breath my grandfather’s lined face glowed in the charring light. A crash overhead made me flinch, but I was too caught up in his stories to pay attention to the bombs, snuggled in our bunk, nestling closer under scratchy wool, with half-eaten carrot sandwiches squashed in our hands. Fa-Fa blew out a stream of smoke and settled back.

‘Mesopotamia, 1916. Flies like soot around my face.’ He waved at the grey fog in front of him, and I could almost see them.

‘That blasted fever, too weak to brush them away … When I’d recovered, I was allowed home on leave. Marvellous to be back in London after that terrible heat. Your grandmother and I went out to a restaurant in – where was it, Jette? Swallow Street? – to toast my return.’

Our grandmother, sniffling over there in a dark corner. I couldn’t imagine anyone wanting to have dinner with her – she barely ever opened her mouth, either to eat or speak. She gave us a watery smile and ducked her head at another skirl above. Then the gap, like thunder after a lightning strike. When it came, it was quite faint.

‘We had a grand blowout, then walked back to Piccadilly to find a hackney – you couldn’t whistle for one, and of course it was dark along the back roads, and we were a trifle fuddled, must admit.’ He chuckled and drew on his pipe, Henry and I giggling at the thought of Fa-Fa, and particularly our grandmother, in such a state. No beating about the bush; that was why we loved him.

‘Then, in the darkness, Jette tripped and fell, and as I helped her up, a thief darted forwards and filched her purse, the rascal! I immediately gave chase.’

Fa-Fa shifted his bulk on the low stool as Henry and I gasped and clutched each other. Jette, hunched in the shadows, the mouse to his man. I couldn’t see her expression in the gloom, only her hand gripping the handkerchief.

‘Caught up with him fairly easily, turned him round and saw he was a young lad, too young to fight in a war but old enough to steal in one. Nothing much in the purse of value, a few coins maybe, but I wasn’t going back to Jette without it. Gave him a bit of a tap, just to let him know I wasn’t going anywhere. Thought that would be the end of it, but he clung on for dear life and try as I might, I couldn’t get it out of his grasp. Locked fast in his fingers, he just wouldn’t let go.’ Fa-Fa held up a ham-fist, tendons bulging, sending a few flecks of tobacco to the floor. He stooped forward to sweep them up before he continued.

‘In the end, had to give him a rare old pummelling, a good going over, but no matter what I did, his grip still wouldn’t budge from the bag.’

Another draw on the pipe – puff, puff, puff – along with the slow glow of the burn. Jette’s thin fingers plucked at her dress.

‘Punch, jab, punch! But he wouldn’t let go. Like a dog with a bone.’

Boom went the bombs. My grandmother blew her nose. We were all wreathed in the fug of Fa-Fa’s smoke. It made my eyes water, but I couldn’t take them off him.

‘Started kicking him in the shins, stamping on his feet. He was screaming but he wouldn’t let go. By the time I’d finished with him, he was curled in a ball at my feet, but his hands still gripped the purse. It was dirty and covered in blood as well. Realized even if I got it back, Jette wouldn’t want it. So I left him there, lying in the street, mewling like a baby, with the bag still clenched in those bloody hands.’

There was a brief silence, even from above, as Fa-Fa put down the pipe and polished his spectacles, rheumy eyes focused on the job. His hands were shaking a little as he put them back on.

‘Damned scamp got the bag. Admired him for it. Whatever was in it that he wanted, he got. Good on him.’ Leaning forward, he licked his fingers and pinched out the candle nearest our bunk. ‘And that’s the moral of the story tonight. If you really want something, you hang on. Don’t give up. Hang on, as if your life depended on it.’

‘Even if someone beats you black and blue?’ piped up Henry.

‘Even if they do that!’ retorted Fa-Fa, ruffling his hair. ‘Even if they cuff you,’ he tweaked Henry’s ear. ‘Even if they thump you,’ he aimed a mock punch at Henry’s stomach, then again a little harder. ‘Even if they bash the hell out of you, you hang on!’ He and Henry began play-fighting, but as the bombs started up again, the frolic became something else. Fa-Fa had Henry in a headlock, my brother’s face a livid red, eyes sparkling with excitement or tears, I couldn’t tell which. Jette stood, holding out her white handkerchief.

‘Father! What are you doing?’

My mother had slipped in through the cellar door, unnoticed. She was unwinding a scarlet scarf from her neck, pale from the cold and angry as usual. Jette rushed forward to embrace her, but Mama ignored her, still glaring at my grandfather. Fa-Fa looked up and released his hold on Henry, who fell back on the bunk, his hands at his throat.

‘When will you learn to be gentle around the children? They’re not your recruits. I suppose you’ve been telling them awful stories again. Now, Milly, Henry, let’s get you in bed, it’s far too late for you to be up.’ She began the motherly round of tucking us in, picking up our half-eaten pieces of bread and leaving them on the side for morning.

Fa-Fa retreated to a chair in the corner to pack another pipe, sulking, as Mama lay down on her pallet. The last thing I remembered was her blowing out the final candle, and the comforting smoulder as Fa-Fa smoked the night away. Then the ink-blot shadows on the walls sent me into a deep sleep that even the booms outside couldn’t penetrate.

The next night, an SC250 landed in the road outside our house, reducing the garden wall to rubble. No one was injured although Fa-Fa’s spectacles fell and shattered in the blast. After that, my mother decided we would be better off in the country and packed us off to my Aunt Sibyl in Yorkshire. But it seemed the decision wasn’t so much based on the bomb as the story of the bag, which Henry recounted to Mama the next morning, provoking another tirade. Fa-Fa was reprehensible, telling disgraceful stories which probably weren’t even true (Jette wouldn’t confirm or deny when asked), it was high time we got some country air, etcetera. So off to Kirkheaton we went, to a draughty old rectory where we slept in the garret, searched priest holes for ghouls, made dens in the woods and mostly forgot about the war and Fa-Fa’s strange habits.

We didn’t forget that story though, and used to tell it back to each other, lying in those hard narrow beds under the eaves. Each time, we’d add an embellishment – a dramatic flourish, some sordid detail, until eventually we weren’t sure where Fa-Fa’s tale ended and ours began. Did he make it up, or did we? Did any of it happen, or none of it? As the years passed, I was inclined to believe the latter.

Still, it’s true though, isn’t it? If you really want something, you hang on.

Chapter 4 (#uaca527fe-9ac8-5623-9d78-92ec8ef5690c)

A week went by without anything happening that I could put in an email to Alistair. I hardly left the house, except to get a few bits – a scrag end at the butchers, a prescription from the chemist. I thought Sylvie was in front of me in the queue and bent my head so she wouldn’t notice me, but it wasn’t her at all, just some other middle-aged woman buying indigestion tablets.

I splashed out on a bottle of wine on the way home, though drinking on my own seemed like a slippery slope. But the evenings stretched, and a glass of something gave the synapses a sly tweak, lending a little ‘entheos’ – the Greek buzz of enthusiasm. Just the one glass, maybe two small ones, distracting myself from the rest of the bottle by poking around various rooms in the house, most of which were hardly ever used any more. What did I need a dining room for? All those dinner parties?

The dust in Leo’s study gave me a coughing fit. I should really pack up the books and get rid of them, but he would have been horrified; most of them were first or rare editions and I didn’t know enough about them to be sure of getting a decent price. So instead I wiped them, and read the inscriptions: ‘Darling Leo, Christmas ’86, with love’; ‘Leo, read this and please be kind – Asa’; ‘Dad – another old tome for you – Mel’. ‘Tómos,’meaning ‘slice’. Each book a slice of the man. None of them were mine. I stopped reading when the children were born.

One night and another visit to the vintners later, I found myself in Alistair’s room, still as it was when he was a boy. His Arsenal posters, his Lego models, his fossils. My son, the archaeologist! The room was like one of his sites; the artefacts and remains of some revered Pharaoh. And now the next in line slept here – I smoothed the pillow where Arthur’s golden head had lain. How I missed him. A gap in the shelf where the first edition should be.

The day Ali left home, we drove him to his halls, Leo chuntering about red-bricks, while I was speechless with the effort of not crying, smiling as we unloaded his bags and settled him in that dingy little room, as if it were just wonderful to think that he was going off into the world to make his own way. What an adventure! Just at the end though, when we said goodbye and he hugged me, I found I couldn’t let go. Eventually, Leo gently prised my fingers from Alistair’s sweater and gave them a reassuring squeeze. ‘He’ll be back at Christmas,’ he said heartily. Christmas, always Christmas – casting its fairy lights on the banality of every other day.

I went to the fridge again, then to Mel’s room to pack up a few of her books. She had her own flat in Cambridge, and it wasn’t like she ever visited any more – not since that terrible afternoon. After checking the cupboard doors on my way to bed, I remembered the lights were still on in the living room, so had to drag myself downstairs again. As the room flicked into darkness, the street outside was illuminated, revealing a young couple wrapped around each other, making their way home after a night out. Her teeth glinted in the lamplight as she smiled up at him, tucking his hand more firmly under her arm as he kissed the top of her head. Lithe and blithe with most of their mistakes unmade. It might have been Leo and me, half a century ago. I closed the curtains, did another round of checking and reeled off to bed.

The next day, nursing a headache, I went to the chemist again, and again saw a woman who looked like Sylvie, only this time it was Sylvie. I ducked, but it was too late.

‘There you are!’ she exclaimed, as if I’d only been gone five minutes. ‘You rushed off the other day. How are you feeling?’

‘Fine, thank you.’ I shuffled forward in the queue, hoping she wouldn’t notice the paracetamol, which I always used to hide from Leo. A hangover was an admission of guilt. If I didn’t have one, then I hadn’t drunk too much the night before.

‘Snap.’ Sylvie nudged her box against mine. ‘I’ve got the most god-awful monster behind the eyes. All self-inflicted, of course. Angela can really put it away. She’s a hard-drinking journalist. What about you?’

She had the air of everything in life being a tremendous joke, a flippancy that made me want to kick off my shoes and talk of cabbages and kings – to be in a world where things didn’t matter so much. But all I could manage was a weak shrug.

‘Fancy a coffee?’ She nodded at the café opposite. It looked as warm and inviting as Sylvie herself, all low lamps, metro tiles and bare wood. There was the row of workers at their laptops, bashing away; two mothers with prams, heads together as they coochy-cooed at their offspring; a couple deep in conversation, their hands entwined. I didn’t belong there, amidst all that companionship and industry, and had no idea why Sylvie would offer such a thing.

‘Oh thank you, but I really must be going.’ I handed over my coins and reached for my paper bag of painkillers.

‘All right, well, see you soon, hopefully. Millicent.’ She remembered.

‘It’s actually Missy,’ I blurted, as she pulled open the door. It tinkled merrily and she turned back with a raised eyebrow.

‘I’m sorry?’

‘Well, my name is Millicent, but everyone calls me Missy,’ I floundered, dropping my change, feeling the heat building in my face.

‘Oh, right, well, Missy it is! I’m sure I’ll bump into you again, I’m always around,’ Sylvie waved and exited, wielding her wicker basket like a 1950s housewife.

I left the chemist, flustered and overset. No one called me that. Not since Leo, and before him, Fa-Fa. She must have thought me completely doolally. Cheeks still burning, I found myself walking across the road towards the café. If she was there I’d jolly well have a coffee with her, stop being so silly.

The workers were still tapping away, the mothers clucking over their babies and gossiping, but the couple had gone. There was no sign of Sylvie, but I ordered a coffee anyway and sat at a table, feeling stiff and embarrassed, sure everyone was watching me, wondering why an old lady would come in here on her own. But no one seemed to notice, and gradually the warmth and noise of the place started to sink in. Someone had left a newspaper on the next table. I took it and read about Jeremy Corbyn, who lived nearby, and the astronaut Tim Peake, living much further away, and Alan Rickman, not living anywhere any more. He was in one of Leo and my favourite films, about a ghost who tries to cheer up his bereaved wife. I was a bit like Nina, the wife, wandering around my empty house in the hope of a miraculous resurrection. I always thought she was wrong not to stay with her husband Jamie, even though he was dead.

I stayed there for a while, sipping my coffee and reading the paper, and when I’d finished, the smiling waitress collected my cup, the mothers shifted their prams for me, and a man left his laptop to hold open the door. I walked home slowly, noting the pine needles that still littered the pavement but occasionally holding my face up to the weak winter sun.

When I got back, rather than embark on my usual round of cleaning, I went upstairs to the spare room and brought down an old paisley throw, draping it experimentally over the sofa. Then I went back up and fetched a lamp, placing it on a low stool to one side. I stood contemplating it for a while, then, feeling faintly foolish, went into the kitchen to make myself a cup of tea.

Later on though, when the light faded, the lamp and blanket looked rather snug. I skipped cereal for once and cooked myself some pasta, eating it off a tray on the sofa while I watched some new period drama. Leo would have scoffed at the anachronisms, but it was a relief to be pulled in by gentle domestic tribulations. I considered rounding my evening off with a glass of wine but remembered I’d finished the bottle the night before. Ah well, I could always buy another tomorrow. Who knew who I’d bump into?

I still didn’t have much to write to Alistair about, but at least I’d been invited for a coffee and went, in a way. Baby steps. Old lady steps. Even if I wasn’t quite sure where I was going.

Chapter 5 (#uaca527fe-9ac8-5623-9d78-92ec8ef5690c)

Down, down, down, and it’s 1956 and I’m in Cambridge, kneeling on the floor trying to make a fire.

There I was, Milly Jameson, in my second year at Newnham College, miserable in a freezing room, pretending I enjoyed reading Homer. The other students were so glamorous, shrieking down the long corridors and sneaking men into their rooms. The girl next door to me was garrulous and captivating, my polar opposite. Tiny and curvy, with tinted blonde hair set in perfect waves, she kept a bottle of gin under her bed for ‘Magic Hour’ cocktails served to her numerous guests. Alicia Stewart and her legendary soirées – every night, I heard her gramophone and banged on the wall as she sang to the tune of ‘Mr Sandman’: ‘Mr Barman, bring me a driiiink … Make it so strong that I can’t thiiiink.’ I had no idea how she intended to get a degree – probably by charming the exam paper into submission.

However, Alicia’s fearsome cocktails were one of the few things that allowed me to unbend, so we had become friends of a sort, or at least she facilitated my drinking habit. My room had a window that opened handily onto a lean-to, serving as an escape route for those who found themselves locked in college after hours, so in return for the odd tipple, I permitted her to smuggle her gentlemen friends out. She swore there was no more going on than heavy petting, as if I were in any way an arbiter in these matters, being as far from ‘necking’ as I was from singing with The Chordettes.

Midway through the second year of my degree, it was becoming apparent that I was not the gift to the academic world I’d imagined. My supervisor described me as ‘a skimming stone’, which was fair – who wanted to contemplate the depths? In the eleven years since my father died, I’d become particularly adept at disregarding deeper waters.

Rather than wrestle with ‘Catullus 85’, ‘Odi et amo’, I was sitting on the threadbare rug that chilly February evening, trying to coax a flicker in the grate. We were in Peile Hall, a draughty old building where they had yet to install gas heating. Instead there were these metal sheets we held in front of the fireplace to draw the air – Sydneys, they were called – but there were only two to go round all of us. We had to traipse along the corridors knocking on doors to hunt one down, so when there was a knock on my own door I assumed it was someone after the Sydney. Instead it was Alicia, already three sheets to the wind, propping herself up against the doorframe.

‘Milish … Mishilent. What’s that smell?’

‘Smoke. I’m trying to light a fire.’

‘Why?’

‘Because it’s cold.’

‘Is it? Never mind. There’s a party. For a new poetry magazine.’

‘Oh good. Have fun.’

‘No. You have to come with me.’

‘Why?’

‘Because I can’t find it.’

‘I’ve got nothing to wear.’

‘You can borrow something.’

‘I don’t feel like it.’

‘There’ll be wine. And it’ll be warm.’

Which was how I found myself, wearing one of Alicia’s black dresses that was too short and big in the bust, tottering through the streets of Cambridge as we searched for the Women’s Union in Falcon Yard. When we finally got there, I wished we hadn’t bothered. So loud and dark, with pockets of light illuminating the jazz band, and people reciting verse that made me cringe. I’ve always found poetry – particularly the reading aloud – excruciating. Like religion and Bongo Boards, best practised in private.

Alicia weaved off and disappeared, so I went in search of the wine she’d promised. At least it was warm, with all those people, all that hot air. There was a poet standing in the corner, head flung back as he declaimed to an earnest little throng – something about buttocks and crystals. Good Lord, it was awful.

I stood with my back to the wall, gulping wine, examining my lack of cleavage and wondering how soon I could escape. And then, across the room, there he was. Like everyone else, he was drunk. But he was the only man wearing a suit, rather than a turtleneck, and that, along with his height, made him distinguished. He saw me, and grinned as though he knew me, and that moment was a homecoming. He ambled over, still smiling. Then, as he drew nearer: ‘Oh, gosh, sorry! I thought you were someone else!’

Up close, he was even drunker than I thought, swaying like a great oak in a gale. But he was very handsome, big and blonde, a Labrador of a man, and I was emboldened by the wine.

‘Who else do you want me to be?’

I’d always been a terrible flirt. I just couldn’t do it, even with lubrication. Luckily it was so loud in there, with the jazz and the poetry and people smashing glasses, that it didn’t seem to matter.

‘Well, since the girl I thought you were doesn’t seem to be here, shall we have another drink?’

He led me over to the long table stacked with bottles, and poured me a glass while I tried to think of something clever to say.

‘It’s a terrible name for a magazine, St Botolph. Sounds like something to do with church,’ I blurted. Oh blast, he was probably one of the editors. But he just laughed.

‘I know, but this party puts paid to that notion. Definitely nothing godly about it.’ He dodged a wine bottle as it sailed past. ‘Do you like poetry?’

‘Not really. It’s a bit self-indulgent for me.’ I didn’t know why I was so forthright all of a sudden. Probably the alcohol, but also a strange sense that I couldn’t stop myself unfurling – a flower opening up to the sun.

‘Really? What do you study?’

‘Classics. But I’m more of a prose person generally.’

‘Tell me something you like.’

I looked around the room. ‘One half of the world cannot understand the pleasures of the other.’ I felt very erudite.

‘Ain’t that a shame,’ he replied, reducing me to gauche schoolgirl again. Across the room there was a couple ferociously kissing, or wrestling, I wasn’t sure which. I had to do something spectacular, be spectacular, so that he would remember this point, and when people asked how we met, we would be able to say, ‘now, there’s a story …’

Instead, Alicia Stewart chose that moment to re-enter the room, waving a glass of wine, tripping over a discarded bottle, grabbing a tablecloth to break her fall and vomiting spectacularly over her old black dress, with me in it. The poet stopped reciting for a second, looking at us curiously, then resumed his discourse on bloated knaves.

‘Shit.’ She lay on the floor, drops of red wine caught on her eyelashes like beads of blood. Roaring with laughter, my knight stooped to help her to her feet. In the circle of his arms she looked up at him admiringly.

‘Oooh, you’re nice!’ Alicia exclaimed. She shifted her glance to me. ‘Milly, you’re covered in sick. You look dreadful. You should go home before you disgrace yourself.’

I glared at her and used the tablecloth to wipe myself.

‘I shall have the honour of escorting you both,’ said our hero, offering us his arms.

‘Lovely,’ slurred Alicia, grabbing hers like a drowning woman. ‘I’m Alishia and this is Milish … Milish … Misha.’

‘Hello, Misha. I’m Leo.’

‘Ooooh, Leo the lion!’ she crowed. ‘Take us back to your lair, Leo!’

We picked our way through the broken glass, swiping a half-empty bottle of wine along the way. Outside in the corridor a girl was sobbing and being comforted by a bony young man who kept patting her shoulder, saying ‘Don’t worry, he was a sod anyway.’ He was always going to be the friend who picked up the pieces.

Outside we could see puffs of our breath in the frigid air as we weaved through the cobbled streets. The sky had cleared, and when we emerged on to King’s Parade it was swathed in a velvety blanket of stars that winked above the chapel. Even they were mocking me.

As soon as a decent interval had elapsed I dropped Leo’s arm and fell behind so they could walk together. But I kept the wine. The streetlamps caught the golden tints in Alicia’s hair as she gazed up at him, doing that tinkly little giggle she affected with men – her real laugh was more of a charlady cackle.

We crossed the bridge on Silver Street, and I looked down at the sluggish River Cam, remembering how I’d imagined Cambridge would be all punting to Grantchester, and cycling through quads with my gown flapping in the breeze – skimming stones that barely rippled the waters. Instead I got the bolt at St Botolph’s, following my sozzled neighbour home in the early hours, covered in her sick, while she seduced someone I saw first. ‘Odi et amo’. Draining the last of the bottle, I threw it in the river and watched it slowly sink into the depths. I suppose it’s still there somewhere.

Chapter 6 (#ulink_9984cc28-12a0-5239-b02c-361daf9f2c78)

The following Tuesday, there was a fight at my new café.

After my encounter with Sylvie in the chemist, I took to loitering around that row of shops, the café in particular, until the smiling waitress began to recognise me and serve my coffee with plain cold milk, none of that frothy nonsense. They gave me a little card that got stamped every time I bought a cup, eventually resulting in a free drink. The bread in the Turkish shop next door was cheap and fresh, and I browsed the children’s fiction in the charity bookshop, picking up a Thomas the Tank Engine book for Arthur for fifty pence.

I’d never bothered with any of these local explorations before – I’d been busy with the children and running the household, and later, when he got ill, looking after Leo. I didn’t have to worry about money then either, whereas now I spent my time rooting out meagre bargains as if it would make the slightest difference. My meanderings whiled away the hours and the pennies, but there was still no sign of Sylvie.

That Tuesday, enjoying my regular ‘Americano’, who should come in but Angela, this time without Otis. She was unkempt as usual, tendrils of too-red hair escaping from a topknot, smudged eyeliner, leather jacket and scruffy boots with buckles that clinked as she walked. At first I didn’t notice the woman she was with, but as they sat down together in the corner I saw she was crying, and that Angela appeared to be comforting her. She was speaking quickly, persuasively, but the woman kept shaking her head, wiping at her cheekbones. She was terribly thin, with a sucked-in look that led me to conclude she was probably on drugs.

Then Angela suddenly sat back, smacked the table like she was finished, and the other woman got up and cannoned her way out of the café. Angela half-stood up and called out something that sounded like ‘Flicks!’ but maybe she was just cursing. The woman stopped in the doorway and turned around, mascara in streaks down the hollowed panes of her face, her mouth twisted into a snarl.

‘You don’t get it,’ she snapped. ‘You’ll never get it.’

They both seemed oblivious to the other customers, who had fallen silent at the spectacle, watching over the rims of their cups as they appreciated this little soap opera scene.

‘I want to help you,’ said Angela. ‘Please.’ She held out a hand.

Like a tennis match, all eyes darted across to the other woman in the doorway.

‘Then stop interfering. Leave me alone,’ she spat, reaching for the door handle. What happened next was extraordinary. Angela leapt forward and pushed the door shut, barring her way; the woman tried to shove her aside, and they grappled in the entrance, pulling each other this way and that. Occasionally one of them would say, ‘no!’ or ‘don’t’, as they continued their ungainly shuffling, oblivious to the dropped mouths of the onlookers. Then the other woman suddenly lifted her hand and slapped Angela across the face. She fell back with a short cry and there was a collective gasp from the customers; one of the row of laptop-workers stood up, as if to protest, then thought better of it as Hanna the waitress hurried forwards and pulled Angela back a step. The other woman watched them for a second, chest heaving, hair askew, then wrenched the door handle and stumbled out into the street.

There was a barely perceptible sigh of disappointment as she exited – the fun spoilt when it was just getting going – but I’ve always found such public displays sordid. Leo and I once had an argument at a party, sotto voce out the sides of our mouths, lifting our glasses and nodding to passing guests. People have no standards nowadays; they just let it all hang out.

Angela, a livid mark on one cheek, sank into her seat, took a cigarette packet out of one pocket and lit up right then and there. Hanna went back over to remonstrate with her. Grimacing, Angela stubbed out the cigarette in a saucer. She sat with her head in her hands for a while, then picked up her bag and made her way to the door. As she passed my table she caught sight of me and raised her eyebrows wearily.

‘Oh, hi, er …’ Unlike Sylvie, she’d forgotten.

‘Millicent.’

‘Hi, Millicent. You OK?’

‘Fine, thank you. Um … you?’ To my dismay she suddenly hefted her bag on to the floor next to me and took the seat opposite, beckoning Hanna over to take her order.

‘I’m fucking awful, as you can see. I’m just gonna sit here for five minutes if that’s OK, stop me doing something stupid.’ Pulling the bowl of sugar cubes towards her, she crunched one between yellow teeth. She was very pale, with dark circles under her eyes. Probably all that hard drinking with Sylvie.

‘Of course.’ I hoped this didn’t mean I would have to pay for her coffee.

We sat in silence for a few seconds as she picked at the skin around her fingernails, which were bitten to the quick and flecked with chipped nail polish. Hanna delivered her coffee and she slurped it, wiping her mouth on her sleeve.

Eventually she looked sideways at me. ‘You married?’

I caught my breath. ‘Yes. But he’s not … he’s not …’

She waved away the question. ‘I’m not,’ she said grimly. ‘And sometimes I’m so fucking relieved, you know? More trouble than it’s worth.’

I was intrigued enough to venture a question of my own. ‘What about your son? Is his father … around?’

She snorted. ‘Didn’t want to know. Better that way, trust me. Anyway, I’m not talking about me. You got children? Grandchildren?’

‘Yes, two children. And one grandchild.’

‘Boy or girl?’

‘A boy. Arthur.’

She grinned. ‘Bet he’s a terror.’

‘Yes,’ I said. ‘A terror.’ But she’d drifted off again, staring into space, drumming her fingers on the table in time to the jazz playing in the background.

‘She’s got to get the kids out. And Bob. That’s the trouble,’ she mumbled, more to herself than to me.

I sat in silence, waiting for her to work it out. Women like her always have some drama or other. Just as I was wondering if it would be rude to signal Hanna to bring the bill, Angela leaned back in her chair, rubbed her face and heaved a great sigh.

‘You’re right, I can’t get involved,’ she said.

I inclined my head, and caught Hanna’s eye.

Angela pinched the bridge of her nose and huffed again. ‘Fuck.’

The expletives that pepper today’s conversations are particularly unsavoury, so ugly and unimaginative, although it was more the repetition that bothered me than the word itself. Angela’s curses were so frequent that they were like punctuation points, each one provoking a twinge of distaste, a sourness in my mouth and hers. Her speech was as sloppy as her scuffed shoes. I picked up my bag and put it onto my knee, ready.

Hanna brought over the bill. As she put the saucer down in front of us, she briefly squeezed Angela’s shoulder, but before I could decide what the gesture meant, Angela tweaked the paper between her fingers. ‘I’ll get this.’

I shook my head, ‘Oh no, please don’t,’ fumbling coins out of my purse. Angela waved them away, ‘No, go on. I barged in on you, it’s the least I can do.’ She slapped a five-pound note on the table and gave a hovering Hanna the thumbs up.

‘Well, there was no need. No need at all. But thank you.’ I stood up, feeling awkward as always, on the cusp of conversations. Beginnings and endings, I’m never sure how they should go. ‘Er, goodbye then. Hope you manage to … sort it out.’ But as I backed away, she grabbed her bag and slid out of her chair. ‘I’ll walk with you, I could do with the fresh air.’ I muttered an oath of my own.

Angela lit up again as soon as we were outside, inhaling her ‘fresh air’, head back and eyes closed, the bruise on her cheek already darkening. She turned to me, smoke curling out of her flared nostrils.

‘Where is Arthur?’

I nearly stumbled, so discomfited – and offended – by the question that for a while I didn’t reply. There was something disturbingly direct and intense about her.

‘He lives with his father, my son. In Australia. They moved out there three years ago.’ The words had to be choked out, everything in me rebelled against them. Angela stared at me for a second, then turned and kicked a fallen leaf.

‘That’s some tough shit,’ she said. ‘What’s he like?’

The marble was back in my throat. ‘He’s four. He likes Lego, and football, and Batman, and all the usual things a boy of his age likes, I suppose.’ I stopped, then found I couldn’t. ‘I don’t see them often, but when I do … He’s busy. Always playing, running, fighting. He hardly ever sits still, he’s just fizzing with energy all the time, so when he does stop, you want to … pin him down, moor him somehow. It’s so hard to keep up with him. But I want to. I want to keep a version of him at every age. He just keeps getting better and better. But I miss all the babies and boys he was, and want them all back.’ I tailed off, embarrassed.

Angela nodded slowly. ‘Yes, it’s like that, isn’t it?’

‘What’s Otis like?’

‘Such a sweet boy,’ she said. ‘Nothing like me. Nothing like his father either, thank Christ. There’s no side to him, no edge at all. I get scared sometimes, by the love. I used to be hard as nails – had to be, doing what I do – but he’s taken it out of me, made me soft. Like when you bash a steak.’

‘Tenderized,’ I said.

‘That’s it. He’s tenderized me, the little sod. I’m no bloody good at my job any more.’

I still didn’t like her much, but she had Otis and I had Arthur. ‘Sylvie said you’re a journalist?’

‘Yeah, but freelance, so you’re always hustling for the next thing.’ She switched into interrogation mode again. ‘You’re retired, right? What did you do?’

‘I was a librarian. Before I had children.’

‘They’re closing all the libraries now,’ she said glumly.

‘Well, this is me,’ I said, my hand on the gate.

Angela looked up. ‘Fuck me, the whole house? I’m just down the road, but in the top-floor flat. Postage stamp. You’ve got the whole house?’

‘We bought in the sixties. The area wasn’t quite so gentrified then.’ I thought of the riots, the strikes, the burglaries. The rubbish piling up in the street. We’d been pioneers.

Resigned to the fact that Angela wanted to come in, I made a last stand all the same. ‘Where’s Otis?’ I asked, hoping she’d remember she had to go and pick him up.

‘He’s at the childminder’s,’ she murmured, still gazing up. ‘The whole house. Jesus.’

Unlocking the front door, I could sense her behind me, hopping from foot to foot in anticipation. Pushing it open, we stepped inside.

The first time I went into that hallway was back in 1964. Heavily pregnant, and daunted by the wide sweep of stairs, I’d waddled left and discovered the most charming drawing room. A huge bay window sent sunlight flooding through, casting rays along the varnished floorboards; dark and light, dust particles rolling in the shafts as I wandered between them. Unfurnished – the previous owner had died and evidently the relatives had swooped in and snaffled the lot – it was a blank slate. While Leo argued with the agent about damp, the house whispered to me that it was mine.

Nowadays, of course, people would move in and immediately gut the place, stripping out and paring back so they can fill it all up again. New owners are so keen to ‘put their stamp on things’ – such an aggressive term, as if a house can be branded with one’s personality. We preferred to let the building’s own character shine through and didn’t change a thing, apart from re-painting one of the bedrooms for the baby. In fact, beyond general maintenance, it was still the same as it was just after Miss Edith Crawshay passed away in it.

‘Shit a brick,’ said Angela, seeing the kitchen. ‘This is a fecking time warp.’ It was rather outmoded, I suppose – the cabinets dated from the fifties. There was an Aga, which seemed incongruous in a city house, but it worked perfectly well, and to demonstrate, I put the kettle on the boiling plate. Angela had already prowled off. I scurried after her, keen to stop her before she reached …

Leo’s study. The door was already ajar. How dare she barge into my house and take stock like this? But as I opened my mouth to berate her she turned and her face was so transfixed with wonder it brought me up short.

‘Oh, Millicent,’ she breathed. ‘This is fabulous.’ She was stroking Leo’s John Milton reverently. ‘It’s a treasure trove. Look!’

‘It’s my husband’s,’ I said, taking it off her and putting it back on the shelf.

‘Some collector,’ she observed, unabashed, wandering over to his still-dusty Dickens collection. ‘Is this him?’ she stopped by his desk to pick up a photo of us, taken shortly after we were married.

‘Yes.’

‘Very attractive,’ she noted, then looked at me appraisingly. ‘Both of you.’ She picked up another photo. ‘Your children? The son, who’s in Australia. What about the girl?’

‘Melanie. She lives in Cambridge.’ I resisted the urge to snatch the frame back.

‘Do you see her often?’ She’d already moved along to the historical section.

‘Not really. She’s very busy. She teaches at the University.’ Once again, Melanie, backing away in my kitchen. ‘What you did … it wasn’t wrong … You shouldn’t blame yourself …’

‘Who’s Leonard Carmichael?’ She pointed at the shelf, stacked with his books, his name again and again on the spines.

‘My husband,’ I said, my voice shaking only slightly. ‘He wrote historical biographies. Mostly political ones.’

She stood on her thin ice and looked at me without saying anything, then the kettle started to whistle and I rushed off to deal with it. When I brought the tea into the living room she was already there, rocking on her heels and gazing around with her mouth open.

‘Have you had a car boot sale or something?’ She gestured around the room.

‘What do you mean?’

‘Well … It’s a bit bare, isn’t it?’

Apart from the throw and lamp I’d reclaimed the other night, there was very little in the living room other than a sofa, a stool serving as a coffee table, and the television on a stand. No rugs, no pictures on the walls, no knick-knacks of any kind. I loathed clutter. When the children were little I felt as though I were drowning in it, and gradually banished the lot, finding that the less stuff I had surrounding me, the calmer things felt. Leo didn’t care one way or the other – as long as he had his books he was happy.

‘There’s rather a lot up in the attic.’ Angela’s eyes gleamed at the thought of untold treasure, but we certainly weren’t opening that can of worms. So she drank her tea and moaned about a deadline. Then she said she’d do a feature on ‘the houses that time forgot’ and use mine as an example, as if I would consider such a vulgar thing. But as she left, running a finger along the banister and casting one last look up at the grubby chandelier above the landing, she suddenly squeezed my arm like a conspirator.

‘Listen, give me your number. It’s my day off on Friday and I’m taking Otis to the park. You should come. He’d like to see you. He hasn’t got a grandma, or at least, not one in this country.’

It was nonsense of course. Otis had barely noticed me. But my face flamed with gratification as I tapped my number into her phone.

‘Maybe,’ I said. ‘If the weather’s nice.’ I shut the door behind her, allowing myself a rare moment of triumph. At last, I would have something to email Alistair about.

Chapter 7 (#ulink_9675c080-0cc5-5687-a94d-0282854fa468)

Angela wanted a babysitter. Of course she did.

On Thursday night I was sleepless with anticipation, checking the weather forecast online all day to make sure it wasn’t going to rain, planning my outfit – trousers, in case I needed to do any bending in the playground – and wondering if I should bring a picnic for Otis in case he got hungry. But I didn’t know his mother’s views on snacks, so instead I put one of Arthur’s little cars ready in my coat pocket, just in case.

When Mel was younger she became interested in amateur dramatics, and used to try out for roles in school plays. She would get hopelessly overwrought about them beforehand, storming around the house saying she couldn’t remember her lines, didn’t understand the text, hadn’t had time to prepare. I had no patience with such dramas, but Leo would indulge them, bearing her off to his study to go through her monologues. Now, tangled up in my blankets, it felt like I was about to mess up an audition.

The next morning, gritty-eyed and irritable, I slumped at my kitchen table drinking strong tea for the caffeine and catching up with the news. Today’s death was Harper Lee. Ten years older than me. Would I last another ten years? I was fit, in good health, compos mentis. But as everyone else dropped off, it felt more and more like I was outstaying my welcome. Sometimes the loneliness was overpowering. Not just the immediate loneliness of living in a huge house on my own, loved ones far away, but a more abstract, galactic isolation, like a leaking boat bobbing in open water, no anchor or land in sight. I might sink, or just float further and further out, and I wasn’t sure which was worse.

I was just wondering whether to telephone Angela and say I wasn’t well enough to go out when there was a resounding knock on the door. As I walked into the hall I could hear Angela outside: ‘Jesus, Otis, you’ll break it down at this rate.’ They were both on the doorstep, Otis dressed as the Incredible Hulk, with a witch’s hat perched incongruously above his mask. Unable to see his face, I felt a stirring of delight. It might have been Arthur under there.

‘Hello, Hulk,’ I said, twitching his hat.

A voice mumbled out from the mask, ‘I’m Bruce Banner.’

‘Hello, Bruce.’ I led them both into the kitchen, wondering if there were biscuits in the bread bin.

‘Sorry we’ve door-stepped you,’ said Angela, hustling him in. The mark on her cheek had faded to a mottled blue. ‘He was up at five-thirty and I’ve been going insane. Ooooh, Otis, say thank you!’ she added, as I handed him a slightly stale digestive.

‘Would you like a cup of tea?’

‘No thanks, I’ll get my fix in the park.’

I put on my coat, checking the pockets for the car, and we set off together in the winter sunshine. Otis shambled along kicking leaves and occasionally hoiking up his costume as his mother launched into a rant about the government. I noticed Otis’s Hulk feet were trailing, picking up debris. We should roll them up for him in the playground. As Angela’s voice reached a higher pitch, I pretended Otis was Arthur, though they were quite different, really. My grandson had a rather forceful personality whereas Otis seemed more pensive. But they both had the droll, quintessential charm of little boys.

‘Anyway, it’ll be fine,’ concluded Angela, having got whatever it was off her chest. By then we’d arrived at the arboreal avenue that led up to the café, the few leaves that still clung to the branches bristling as the gentlest of castanets. The air was crisp and there was a pleasing freshness to the day, as if everything were newly minted.

Angela nodded towards the lakes. ‘I heard a rumour that the fish all died. The shock was too much for them.’

‘The electric shock?’

‘No, the shock of being in a different pond.’

She went off to get her coffee while I stood with the little one watching the park’s resident goats stump around their enclosure. After a minute or two of silence he said, ‘Goats have rectangles in their eyes.’

I looked over at the impassive mask, two dark circles regarding me solemnly from within.

‘Do they? I didn’t know that.’

‘Yes.’ He pulled me towards the fence. ‘Look!’ As the darker goat passed us and snuffled its nose against the wire, he pointed at one rolling eye. Bending and peering, I saw that the pupil was rectangular-shaped, like a horizontal slit. It looked rather alarming.

‘How extraordinary,’ I said, squeezing his hand. ‘Why is that, do you think?’

‘That mean,’ – he had such a quaint way of speaking – ‘that mean he gets hunted. The hunted animals have square eyes. The ones who hunt them are round.’

‘Our eyes are round,’ I noted.

‘Yes,’ he agreed. ‘That mean we are the hunters.’ He scampered off towards Angela, who was approaching with a steaming paper cup, puffing away on a cigarette.

‘You go on ahead, I’ve got to get this smoked before I can go in. Fucking shirty mums,’ she grunted.

At this time of day the playground was sparsely populated, just a few mothers chatting as their children scuttled around. Otis immediately climbed onto the trampoline, tripping over his Hulk feet and sending the witch’s hat askew. By the time Angela rejoined us I was holding the costume and Otis was jumping in his normal clothes, holding Arthur’s car.

Angela stood next to me, shivering in her leather jacket. ‘God, this is awful, isn’t it? Half the time I’m panicking he’s going to break something or get snatched by a paedophile, and the other half I’m going out of my mind with boredom. I could do with a drink, they should put a bar here or something.’

I thought it was perfectly pleasant to watch the children playing and enjoy the fresh air, but Angela was already furiously jabbing at her phone. She would periodically dash out of the playground to greet people she knew, though she seemed more interested in their dogs. Frankly, she didn’t watch Otis as well as she should have, but I suppose that was the point of inviting me. An extra pair of hunter eyes.

Every time she returned there was a new tirade. The park wardens were jobsworths, the cyclists went too fast, the joggers were wankers and whoever poisoned the pond and the fish deserved to drink their own toxic water. She held forth on a number of subjects, another cigarette perched between two fingers, despite the disapproving looks, as Otis ditched the climbing frames in favour of chasing pigeons and digging rice cakes out of his mother’s bag. I hadn’t warmed to Angela particularly, but true to her profession she was something of a raconteur, and I began to enjoy the stream of invective, storing tidbits of gossip for Alistair. A famous news correspondent had had his morning jog interrupted by a Cockapoo and had started a furious row with its owner: ‘like he thinks his pissy little run is as important as Syria.’ A Red Setter had got into the playground and his subsequent rampage had parents up in arms: ‘they should shut the fucking gates then, shouldn’t they?’ A Retriever had run off with an old lady’s wig: ‘She was livid but it wasn’t the bloody dog’s fault, was it? It was his tosspot of an owner; too busy chatting up some tart with a Chihuahua.’

She paused for breath. ‘Otis, not over there!’ she bellowed. ‘Tramps piss there and stuff.’ She turned back to me. ‘Listen, talking of dogs … I need to ask you about my friend. The one you saw the other day. She’s in a bit of a mess and I’ve got this idea …’

‘Angela, darling, why aren’t you wearing a proper coat?’ We turned to see Sylvie ambling towards us, eyes crinkling at the corners as she picked her way through scurrying children.

‘I feel quite the adventurer in here, with no little people. Millicent! No – Missy! How lovely. I came to invite you all to lunch. I’ve just bought some Le Creuset and want to show it off.’

‘All right,’ said Angela. ‘We’d better go now though. You left the gate open and Decca and Nancy have got in.’

‘Heavens.’ Sylvie swivelled round and saw her dogs frantically digging in the sandpit, showering nearby children, who shrieked with laughter and flung sand in each other’s faces as their mothers bore down on us, fingers wagging.

‘Oh, hell.’ Angela grabbed a passing Otis by his sweater and pushed him towards the gates. ‘Let’s get out of here before one of them takes a shit on the seesaw.’

Lunch at Sylvie’s; my crazy-old-lady fantasy made flesh … I wondered how to say no, but it seemed they just assumed I would be coming, so I picked up Arthur’s discarded car and followed, feeling rather light-headed.

‘Why did Sylvie call you Missy?’ asked Angela, as Sylvie secured her dogs and, scattering apologies, we left the playground.

‘Just a silly nickname,’ I hedged, still embarrassed about it.

‘It suits you,’ she said, and I couldn’t decide whether to be pleased or not.

Sylvie lived in an elegant Georgian house west of the park, with a glossy wrought iron gate and an exquisite little parterre in the front garden. She led us up the flagged path, and turning back as she unlocked the front door, winked at me.

‘My abode,’ she said, and pushed it open.

We were immediately greeted by the smell of cinnamon, and a very grand black and white cat who weaved around our legs as we entered. The walls were papered in the same William Morris design that adorned my old college halls and I felt a sense of nostalgia as we made our way through to her kitchen and wandered amongst the artful clutter of crockery, copper pans and poinsettia, the room as homely and twinkling as Sylvie herself. Thinking of my own bare and antiquated space, I decided she must never see it.

We had the most delightful lunch, perched (in my case, rather precariously) on bar stools around the peninsula. Home-made hummus and plump olives, a quiche warm from the oven, tangy blue cheese, flatbreads dipped in a broad bean and feta concoction that was salty and moreish, all displayed on matching teal blue crockery. I’d never seen food as something to be fussed over, but there was something about Sylvie’s unaffected pleasure in it all that was infectious, encouraging me to relish every mouthful. Otis lay on the sofa in the sitting room, draped in cat and dogs, hummus around his mouth as he watched CBeebies. Angela was reading Country Living, occasionally stabbing a page to complain about the size of people’s houses, as Sylvie bustled about, arranging her smart new pots and dishes.

‘How do you two know each other?’ I asked, picking up an olive.

‘I kidnapped her dog,’ mumbled Angela, through a mouthful of bread.

Sylvie chortled. ‘It’s true. Four years ago. She stole Nancy from the park. I sent out a search party and found a dog walker who’d spotted her with a mad-looking Irish woman and a screaming baby. Then someone else pointed the way to Angie’s garret. Found them both on the sofa eating Hobnobs and watching Bargain Hunt.’

‘It was a mistake,’ protested Angela. ‘I thought she was a stray.’ She reached down and fondled one of the dogs – I assumed it was Nancy, though still couldn’t tell the difference. ‘I was a bit mad, I’d just had Otis. Thought a dog would complete the family.’

As shadows lengthened on the walls, candles were lit, and – really too early – a bottle of red wine opened. I declined, but was pressured into a small glass. After that, to the accompaniment of Frank Sinatra, Angela became more raucous, knocking back her drink and fulminating again. Sylvie asked me lots of questions about myself, which was nice of her though I wouldn’t bore her with any details. I did tell her a bit about Arthur and noticed her eyes flick towards Otis on the sofa.

Drifting off as I sipped my wine and admired the leaping flames in the fireplace, I found myself thinking of families and oikos, an important concept in ancient Greece. It’s not an easy idea to describe as it can mean different things. A house or dwelling, but also the inhabitants. Home and hearth. The hearth part always interested me as I thought of oikos as a kind of rock – the rock upon which a family was built. But how big a family did one need to achieve it? I didn’t perceive anything lacking in Sylvie, whereas my loneliness, my emptiness, was a balloon that bellied and dragged me away. But when the house had been full of my husband and children, I didn’t notice, didn’t appreciate my oikos. Or maybe I had never had it at all. Perhaps the threads of my life were always loose, always out of my control, just waiting to slip out of reach.

‘Millicent. Missy,’ barked Angela, rousing me. ‘What are you thinking about? You were a million miles away.’

Only half a mile down the road, actually. The bottle was nearly empty and suddenly I felt I shouldn’t be around for the second. I had somewhere I needed to be.

‘I must be going,’ Gripping the marble table top, I gingerly slipped off the stool. ‘Thank you so much, it’s been lovely.’

‘I’ll come round next week,’ said Angela, picking up a corkscrew. ‘I want to talk to you about my idea. And maybe you could take Otis to the park again?’ She fixed her round eyes on me innocently.

Like I said, she wanted a babysitter. But when it came to that kind of thing, I was easy prey. I went through to the living room and mussed Otis’s hair as he sleepily watched a Peter Rabbit cartoon.

Sylvie led me back down the hallway, switching on lamps as she went.

‘You have a lovely house,’ I said, picking up my purse.

‘Thank you, sweetie,’ responded Sylvie, helping me with my coat. ‘Angie says yours is gorgeous too. Lovely to have a big house round here.’

Not if there was no one in it. ‘You should come round,’ I found myself saying. ‘I wish it looked more like this.’

‘Darling, I’m a designer – I live for that sort of thing.’ She kissed me on the cheek and I could feel tears starting, so I ducked my head and walked quickly out the door, humming Sinatra to distract myself.

Out in the dusk, I hit rush hour; commuters, heads down like mine, braced against the chill, gunning for hearth and home. I walked slowly towards my destination, torn between hope and melancholy. I’d had a lovely day, but the warmth and cheer only served to highlight the dismal prospect of my lonely walk to an even lonelier place, trying to hold on to the threads of a previous life.

After my bleak pilgrimage to take flowers to the empty space that was once Leo, I headed home, trying to cheer myself up. Maybe Sylvie would come round. Maybe I would take Otis to the park. I let myself in and switched on the lights, wincing a little at the glare. Going through to the kitchen, I put the kettle on, opened my laptop, my state-of-the-art laptop given to me by my son the archaeologist, and logged into my email.

‘Darling Ali,’ I began.

Chapter 8 (#ulink_3f9facab-463f-5092-b883-37da344dafd9)

I was a virgin, of course. This was 1956 – what else could I be? An uptight nineteen-year-old, carefully reared in Kensington and Kirkheaton? I’d spent weeks hearing him traipse up and down my corridor on his way to Alicia’s room, gramophone blaring, though not entirely drowning out the sound of that grating little giggle. Once I bumped into him en route to the bathroom in my robe, and nodded awkwardly, cheeks burning with the shame of rejection, though it had never even got to that stage. Thankfully, Alicia had the decency not to ask me to let him out through my window after their late-night shenanigans. But then that just went to show, didn’t it, that she knew. I didn’t drink with her any more, but found other ways to acquire alcohol.

Despite my social and seductive limitations, I was not entirely a loner. Dutifully doing the usual round of parties and gatherings, I acquired a few friends and was even asked to a play by a young man from St Catharine’s. I put on my best green dress with a sweetheart neckline, my hair curled right for once, and cycled over to the ADC theatre to meet him. He was called Percy, but I wasn’t sure if that was his first name or last. He met me outside the theatre and under the streetlamp I could tell he would go bald in later life. The play wasn’t a play at all but a series of little skits, none of which I found very funny, though everyone else roared with laughter throughout.

After an excruciating drink in the café round the corner, Percy walked me home, which was unnecessary as I had my bicycle with me, so he pushed it while I hugged my wrap around myself and wished I’d worn something warmer. Outside the door to the porter’s lodge he lunged, letting the bicycle fall to the ground in his enthusiasm. The feeling of that tongue forcing its way down my throat, his hands digging into my shoulders and ripping my dress, made me gag. He apologized afterwards. I think the experience upset him as much as me. So I apologized as well, and he picked up my bicycle like a gentleman. Then he left for his college, promising to call on me the following week, although we both knew he wouldn’t.

Back in my room I cried a little and hung up my dress although it kept slipping off the hanger because of the tear. Then I got a bottle of sherry out of my desk and poured myself a glass, and another, and another, so that by the time Leo knocked on my door just after midnight, I was already well away.

‘Can I come in? Sorry, I’ve had rather a bad night,’ he leaned against the doorframe, blinking owlishly and waving a half-empty bottle of wine. I tightened the cord of my dressing gown, feeling thankful my hair was still done. Of course I let him in; I’d let him in the moment I first saw him across a crowded room.

We shared the rest of the bottle as Leo told me Alicia had finished with him, that she’d met someone else, a viscount from St John’s. He was so stoic about it – ‘obviously I can’t compete, he’s got a castle in Northumberland’ – that when he kissed me, I didn’t mind at all. He was so different from Percy or any of the other bumbling, self-absorbed boys I’d met. He just felt like my home.

So when he led me to that narrow, creaking bed I didn’t resist, and in fact it was I who pulled him down on top of me, to feel the weight of him, mooring me. Then there was the moment he looked into my eyes and said, ‘shall I?’ and I nodded, fiercely, because right at that moment there was no fork in the road, no other option open to me but to pursue him, us. Afterwards, we lay together in the embers, every bit entwined, him ringleting my hair on one of his fingers, and I felt replete, complete. My song, answered.

But later, when the dawn light pierced the thin curtains, I saw the blood on the sheets, felt the pounding in my head and heart, and realized what a mess I’d made of it all. Why couldn’t I be as sophisticated and experienced and elusive as Alicia and all the other girls who twirled around Cambridge as though they owned it?