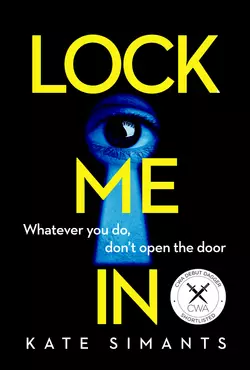

Lock Me In

Kate Simants

‘A five star, unputdownable thriller that had me gripped from the very first page… I read it in one sitting!’ Caz Finlay, author of The Boss Shortlisted for the CWA Debut Dagger award Whatever you do, don’t open the door… By day, Ellie Power has a normal life. She has a stable home, a loving boyfriend, a future. But at night, she suffers from a sleep disorder. She becomes angry, unpredictable, violent. Her mother locks Ellie in her bedroom every night, to keep them both safe. Then one morning, Ellie wakes up, horrified to find the lock on her bedroom door smashed from the inside. She is covered in injuries, unable to remember anything about the night before. And her boyfriend Matt is nowhere to be found… Praise for Lock Me In ‘Intricately plotted, beautifully written’ Harriet Tyce, author of Blood Orange ‘This ambitious and wide-reaching novel had me hooked from the very first page’ S. E. Lynes, author of The Women ‘One of the best debuts I have ever read’ Clare Empson, author of Him 'A flawlessly written, jaw-dropping, chilling and twisty psychological thriller' Sam Carrington, author of Saving Sophie ‘A disturbing psychological thriller’ Rachel Sargeant, author of The Perfect Neighbours ‘The characters are fresh, the dialogue sharp’ G. D. Abson, author of Motherland ‘A stunning debut. Gripping, compelling and skilfully crafted’ N J Crosskey, author of Poster Boy

Lock Me In

KATE SIMANTS

A division of HarperCollinsPublishers

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

One More Chapter

an imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

First published in Great Britain by HarperCollinsPublishers 2019

Copyright © Kate Simants 2019

Cover design by Micaela Alcaino © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd2019

Cover images © Shutterstock.com (http://Shutterstock.com)

The CWA Dagger logo is a registered trademark owned by and reproduced with the permission of the CWA.

Kate Simants asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Ebook Edition © October 2019 ISBN: 9780008353292

Version: 2019-09-27

For Tom, who never once suggested I give up this nonsense and get a real job.

You’re the best mate a girl could have.

Table of Contents

Cover (#u79f1c16f-d70b-5d62-901b-382e3e6e02f8)

Title Page (#u373e94d0-f346-55fa-b511-a13584e6cd13)

Copyright (#u48154ad9-a76f-5e38-8de2-00435e845f44)

Dedication (#ub24fe957-6a08-5407-94c9-41e7f0dda71c)

Prologue

1. Ellie

2. Mae

3.

4. Ellie

5. Mae

6. Ellie

7. Mae

8. Ellie

9. Mae

10. Ellie

11.

12. Mae

13. Ellie

14. Mae

15. Mae

16. Ellie

17. Mae

18. Ellie

19. Mae

20. Ellie

21.

22. Mae

23. Ellie

24. Mae

25. Ellie

26. Mae

27. Ellie

28. Mae

29.

30. Ellie

31. Mae

32. Ellie

33. Mae

34. Ellie

35. Mae

36. Ellie

37. Mae

38.

39. Ellie

40. Mae

41. Ellie

42. Mae

43. Ellie

44. Mae

45. Ellie

46. Mae

47. Ellie

48.

49. Mae

50. Ellie

51. Mae

52. Ellie

53. Mae

54. Ellie

55. Mae

56.

57. Mae

58. Ellie

59. Mae

60. Mae

61. Ellie

62. Mae

63. Ellie

64. Mae

65. Ellie

66.

67. Mae

68. Ellie

69. Mae

70. Ellie

71. Christine

72. Mae

73. Ellie

74. Ellie

75. Mae

76. Ellie

Epilogue

Acknowledgements

About the Author

About the Publisher

Prologue (#u079d501d-f43d-5e2f-9341-37d3e850f369)

You want to know fear?

Imagine someone there, every day when you wake. Imagine knowing, without even opening your eyes, that someone is watching you.

Take your time. Let your mind get used to consciousness.

A girl. There. Not in the passage, not at the door, or by the window. Not even at the end of your bed.

Closer than that.

She stares, unblinking, her eyes burning into yours even though you keep your eyelids shut tight. You move, and for a moment, she slips away from you. But she’s not gone. You know that much.

You think, please. Not again. Your teeth tighten so hard they squeak against each other. You don’t mean to do it, but this is real, right-now fear, and your body doesn’t care what you want. Your heart starts firing out ball-bearings instead of blood. Open your eyes, you tell yourself.

You say her name, and she stiffens. You feel her do it, rigid and alert in your stomach. She is inside you. She is always inside you, listening under your skin.

When you were little, the doctors said this was a known disorder, that they could help. That this other you, your alter, the one who’s always there like an unwanted imaginary friend, could be brought out into the light. That this other girl that you sometimes became was there because, at some point in your life, you needed to switch your reality off. There must have been something, they said, that brought her bursting out of you: some trauma, some incitement, some moment of quickening. You never found it. In the end they gave up, telling you she was nothing to fear, that she could be managed, medicated, contained.

The doctors were wrong.

You feel her rising. And it doesn’t matter how much you know it’s not a physical condition, that it’s all in your head: when she fights you, it hurts. If you want your body to be yours and not hers, you have to fight back.

Now comes the tension, a thickening, swelling the marrow of your bones. You wrench the bedclothes in your fists, and you press your heels into the mattress. She is stiff and screaming in your veins, inside the cells of your blood. You try to cry out but your voice sticks behind your tongue, no breath behind it. She has her hands in the wet depths of your throat, bending the stiff cartilage of your windpipe.

And just like that she bursts into smoke. Goes quiet. You’re left with the ragged sound of your breath, your heartbeat thundering in your ears. Even as it slows, you know she isn’t gone. She doesn’t go, ever.

You have learned never to trust the silence, never to let your guard down. Even as you sleep.

Especially as you sleep.

You want to know fear?

Fear has a name.

Her name is Siggy.

1. (#u079d501d-f43d-5e2f-9341-37d3e850f369)

Ellie (#u079d501d-f43d-5e2f-9341-37d3e850f369)

London, 2011

I woke gasping, the sheet dislodged and twisted tight around my limbs.

I kicked a leg out against the thin partition between my room and the kitchen. Through the wall I heard the radio being clicked off.

‘Ellie?’ Mum’s voice, muffled through the plasterboard.

Siggy went still, and became a cold, thin layer at the base of my brain. She was quiet for a few moments, then she disappeared like a flame in a vacuum, leaving just the staccato sound of my breathing.

‘Ellie, sweetheart? You awake?’

I let my eyes open, worked my jaw and mumbled a croaky, ‘Yeah.’

It was later than I’d thought. A cold screen of early winter daylight sliced through the middle of my tiny room. Motes of dust danced in its blade. I spread my hand across the bare wall. All our walls were bare, in all the flats and houses we’d lived in since I was a child. We never stayed long, and whenever we left, we left in a hurry.

‘She gone?’ Mum called. She always managed to sound cheerful.

‘Mm-hmm.’ I untangled myself from the sheet and tried to swing my knees over the edge of the bed, but I couldn’t do it. Too heavy. It was bad this morning, worse than usual. Soreness bloomed across my right shoulder and down my arm. I had to heave my breath in.

‘Just doing coffee,’ she said, her voice already moving away. She turned the radio back up. The track finished and was replaced by a DJ in an inoffensive, sing-song voice. I heard her unlock the crockery cupboard, taking out mugs, locking it again, setting them down.

I lay for a minute in the S-shape of warmth, trying to salvage what I could of the dream. There was a bright blue sky, and that building. Always that building, the one I’d drawn as a child over and over again: long and low, as unchanging and precise as a photograph, every time. Every night.

Slowly, under the duvet, I shifted. But as I moved to push myself up, bright, brilliant pain shot across my hand, bringing tears to my eyes.

Bisecting my palm, intermittent but extending right over to the base of my thumb, was a ragged tear. Deep punctures, red and swollen. I touched it and winced: it was exquisitely sore, the flesh not yet dry.

Gingerly, I pushed away the covers and looked myself over. Across the right of my pelvis, a blue-black mess of bruising. I pressed the tip of a finger to the centre of the darkest part. The ache, bone-deep, rose up to meet it.

Where had it come from?

A fine thread of fear started to tug at me, hard. I sat up, planted my feet on the floor. Built up the courage to look at the door.

It would be locked. It had to be locked. Hadn’t I heard Mum lock it? I played back the last moments of the day before. Matt had dropped me off after our quick trip to the pub near the narrowboat he was renting. Mum had made me dinner, a pasta thing we ate together in the kitchen. I’d gone to bed early to read for a while. Mum had locked me in before she left for her late shift. She had.

With my blood roaring in my temples, I turned my head. Opened my eyes.

It was only a fingerbreadth, but the door was open. There, on the white gloss of the frame, was something that made me shoot out of bed as if it had caught fire. I crossed the room in three steps and lifted my fingers to the dark marks on the paintwork.

Smears of reddish-brown, crusted at the edge. And on the backs of my hands – I saw it now – the same thing, the same colour, exactly.

Mud.

Siggy had taken me outside.

Mum appeared in the corridor, holding mugs. She stopped dead, then nudged the door fully open with her toe.

‘What—?’ she started.

I met her eyes. ‘You locked it.’

She gripped her eyelids shut for a second, as if dislodging an image.

‘You locked it,’ I repeated, louder. ‘You did. I heard you.’

She set down the two mugs of coffee and bent to touch the door. She was still wearing her cleaning uniform from the nightshift at the same hospital where Matt worked, the bleach-stained mauve tabard over blue scrubs.

‘Holy shit,’ she whispered, the blood sinking from her skin. She went back out, examining it from the other side. ‘What the hell happened here?’

I followed her. In the hall, the bolt that should have been above the mortice lock on the outside of my door was lying on the floor, its two separate sections still secured together with the padlock. Torn paint and splinters of wood clung to the screws where they’d been wrenched out of place. Several inches higher was what remained of the sliding chain lock, the plug hanging uselessly, swinging on the chain. The force it would have taken to break it like that, wrenched inwards with enough power to break the locks on the outside …

Siggy’s little fingers plucked the fibres of my biceps. If I hadn’t known her better I would have wondered if she was smiling.

‘Do you not remember anything?’ Mum asked.

‘No. But … look.’ I lifted my hand, and her eyes went wide.

I let her take it, and she turned it over. Under her breath she muttered, ‘Jesus,’ then decisively, ‘Bathroom. Got to wash it. Come on.’

Holding me by the wrist so she didn’t touch the wound, she guided me through into the bathroom and pulled the cord for the light. She flipped the toilet lid down and sat me on it like a child, then yanked up her sleeves, exposing her ropey, muscular forearms, hardened from the years of push-ups she did to make sure she was stronger than Siggy.

‘This’ll sting, love.’ The tap screeched as she turned it on, and a thick twist of cold water ran into the avocado-coloured sink. ‘Stick it under here.’

I did as I was told.

Frowning at my palm, she pointed. ‘My guess is barbed wire. Look at the spacing.’ She was right: the punctures were even. Each a centimetre from the last.

She turned and angrily whipped the towel from the electric heater that hadn’t worked in the eight months we’d been there. She dried her hands and kicked it into a bundle by the washing basket.

‘Fucking Siggy,’ she said, dragging her fingers hard across her scalp. ‘What did she do with you this time?’

She wasn’t expecting an answer. We called them fugues, and I never knew what Siggy made me do during them, where she took me. Or why. All I could do was piece it together from whatever mess Siggy left behind, crowbarring in cause by surveying the effect, trying to make sense of it. The fact that the fugues always happened at night had baffled psychologist after psychologist, neurologist after sleep specialist when I was younger until Mum got so frustrated with them that we stopped going altogether. It’s a time in my life I have almost no memory of, but Mum kept journals: all the medicines, all the experts, all the sessions and techniques and homework. Nothing worked. The drugs they said would help with the dissociation made no difference. The fugues continued; the nightmares kept coming. Although I didn’t get worse for a long time – I was plagued by panic attacks, but I never started ‘switching’ during the day, which had always been my fear – I didn’t get better. Eventually, they ran out of things to try. We never got a cure, and we never got an answer: we were dismissed as an anomaly.

But this was back when Siggy was playful, doing small stuff, things that didn’t matter. Like when she filled our shoes with milk while we slept or pulled all the books off the shelves and made them into colour-coded piles. Just the little things, things we could laugh about, almost.

This was before we started needing locks.

This was before Jodie.

My fingers were going numb with the cold, but the torn flesh on my hand was burning now and had started to swell. The mud darkened and flaked off under the water until soon there was nothing left, just clean, pink, angry skin. I turned to wash the mud from the other hand too, and found more of it, up my arm, as far as my elbow.

Where had I gone last night?

What had I done?

Eventually the cold got too much to bear, and I pulled my hand out of the sink and shook my hair back. Mum’s eyes went to my throat.

‘What the hell happened to your neck?’

I got up, dodging round her to get to the mirror. I lifted my chin.

‘Don’t freak out.’ Mum stood behind me, put a hand on my shoulder. ‘Control it. Do not freak out.’

Dark marks the size of grapes, with blue-white crescents indented at their outer edges. Bruises: four in a line on one side of my windpipe, one on the other. Just above the old, jagged scar from years before.

Four and one. Fingers and a thumb.

‘Come on, sweetheart, try,’ she said, angry now. ‘Try to remember.’

I studied the bruises, touched my fingers to them, lining them up, then I stared at myself in the eyes in the mirror: one green, one blue. One for me, one for Siggy.

Think.

Mud.

Barbed wire on my hand.

And a handprint on my neck.

My breath turned solid in my chest as the thought bloomed, running its course.

‘Mum. What if someone was trying to stop …?’

I trailed off. Matt. I lurched out of the room.

My phone wasn’t beside my bed, and it wasn’t in the jeans I’d worn the previous night. I went to look for it in the pocket of the raincoat I was sure I’d left on the back of the door, but neither the phone nor the coat were there. I stumbled out into the living room. Spotting my phone charging in the corner, I yanked the cable out and dialled, pressed it to my ear, thinking, answer. Answer, for Christ’s sake.

‘OK, stop,’ Mum said from behind me. ‘Take a moment to think about this. Ellie. Stop.’

I turned to face her. ‘What?’

‘We need to think smart,’ she said, reaching for the phone.

I ducked away from her before I processed what she’d said. I’d been thinking there must have been a fight, something I could fix. But my mother, she was already thinking of Jodie. Of what Siggy had done before.

That she’d done it again.

The fog in my head cleared suddenly and the gentle Scots of Matt’s voice was in my ear saying you’ve reached Matt Corsham. I’m probably in my dungeon – the photo lab, in the hospital basement – leave a message. I hung up before the beep and dialled it again. Looked at the clock: 07:43. He was on earlies, started at eight, he should have been on his way to the hospital, on the 267. He should have his phone in his hand. I slumped onto the sofa. He should be texting me.

Mum sat beside me and took my face in her hands.

‘What do we do?’ she asked me gently. ‘Things get tough, what do we do?’

‘We deal with it,’ I told her in a whisper.

‘That’s exactly what we do. You and me.’ She sighed, took my good hand and peeled each finger from the phone, until I released it. It went on the table, out of reach, then she moved up next to me, pulling me close. I relented, sank my head against her chest.

‘Please don’t let this happen again, Mum.’

‘Shh. He’ll be OK, though. Probably just have worked late or started early or something.’ She gave me a gentle nudge. ‘Don’t worry. Just a bit of mud. Just some scrapes.’

Even then, neither one of us believed it.

2. (#u079d501d-f43d-5e2f-9341-37d3e850f369)

Mae (#u079d501d-f43d-5e2f-9341-37d3e850f369)

Detective Sergeant Ben Kwon Mae stopped at the lights. He raised his eyebrows in the rear-view mirror and the kicking to the back of his seat immediately ceased. Bear, his 8-year-old daughter who was suspiciously engrossed in the palm of her hand, slowly lifted her chin to meet his gaze.

‘What?’ Eyes all wide, butter-wouldn’t-melt incredulous. ‘It wasn’t me!’

He laughed. Thirty quid a pop, the drama lessons his ex-wife made him shell out for and look what it bought.

‘You’re a terrible actress, Bear. Really bad,’ he said, returning his attention to the school-run gridlock. Should have walked.

The kicking resumed, and he swung around. ‘Oi! Stop it!’

She laughed, but then he clocked the crisps all over her almost-freshly-laundered school sweater. Busted, she started to brush at them, scattering them into the footwell.

He blew out his cheeks. Didn’t say anything. Didn’t need to.

‘I’m hungry.’

‘But crisps, mate?’

He wanted to leave it, because the clock on the dash gave him eight minutes to get Bear to school and wasting one of those minutes complaining about her diet meant wasting them all. When the bell rang at 8.45 he’d be looking at a clear week and a half until he got her back. But Nadia had complained enough times about having to deal with what she called ‘the BMI situation’ on her own. It wasn’t fair on her for him to just ignore it.

He shook his head. ‘I did offer you a proper breakfast. I thought you loved scrambled eggs.’

‘Not since I was like three. I hate it.’ He could only see the top of her head now, but he was pretty sure she was holding back tears. ‘You never have any decent food in your stupid flat. I’m always hungry at school after I have to stay at yours.’

‘OK, well. I’ll stock up next time.’ The lights changed and he turned back to the road. ‘Just have to make healthy choices, that’s all I’m saying.’

‘All you’re saying is I’m fat and no one likes me.’ She stared angrily out of the window, nicking at the raw skin around her thumbnail with her teeth.

‘That’s absolutely not true.’ Nice one, Superdad. One guess what she’d remember about the visit with him now. In the mirror he saw her lean her head on the glass, and they finished the journey in silence. Could they bunk off for an hour? Take her to the park, make things okay between them so they’d part on good terms? No. Obviously not. Nadia would find out, for a start, and his approval rating was already on the floor. Things had eroded badly enough between them lately without him adding truancy to the list.

Only three minutes late, he swung into a space miraculously close to the school entrance. He got out and went round to open Bear’s child-locked door.

‘My tummy hurts,’ she whined.

‘OK. Well, let’s get some fresh air and see how you feel in a minute.’

‘But I’ve got a headache.’ Her voice was quieter. He followed her gaze out across the playground to where two boys, older, were in direct line of sight. They turned away as soon as he made eye contact. Bear sighed and looked at her feet.

He leaned across her to undo her seatbelt. ‘Friends of yours?’

‘No! Get off, Ben,’ she snapped, twisting away.

He made sure the sudden sag in his chest didn’t make it to his face.

‘It’s Dad,’ he told her, pulling her bag and reading folder out from the back seat. This Ben thing was new this visit. No way did she call Nadia by her first name. He hadn’t even heard her shorten it from Mummy yet. He wasn’t having it. ‘You call me Dad.’

‘Whatever.’ She squeezed past him and stumped off towards the gate. Catching her up, he reached for her shoulder but let his hand drop before it touched her. Best not push it.

‘Tell you what. If you don’t give me a cuddle, I’ll cave your head in with a fire extinguisher.’ A bit too hopeful, the way it came out, but she let him draw level. He coughed, dropped his voice a bit. ‘Gouge your eyes out with a soup spoon. I will. I’ve done it before. In Helmand.’

Which won him a very small smile. ‘You haven’t been to Helmand.’

‘Flipping have.’

‘And you’ve used that one before, too.’

‘Right, right. Sloppy.’ He shoved his hands in his pockets, thinking. ‘In that case I’ll just have to grate your nose off.’

‘Yeah? How?’

‘Cheese grater. Like I did in Operation Desert Knickers.’

A single sniff of a laugh, and she glanced at him. The shape of her eyes so almost-Caucasian, hardly a sniff of Korean about her. Like even his genes were being diluted, rinsed out of her life.

But her sideways smile was all his. She took a deep breath. ‘I’ll boil you alive and peel your skin off and sell it to the shoe shop so they can make shoes out of you.’

The realization that she’d planned that, rehearsed it, glowed like a coal in his belly.

‘Nice.’ He gave her a serious look and slow-nodded. ‘What’s the score? Seventeen-twelve?’

‘You wish,’ she said, appeased now. ‘Nineteen-twelve.’ She cheerfully swung her bag at him, obliviously but narrowly missing his bollocks.

Bear started to skip but stopped when she got to the gate. She was scanning the yard for those boys.

Mae crouched. ‘If there’s anything you need me to deal with—’

She shot him a serious look. ‘No. There’s nothing. There isn’t.’

‘Because if—’

‘Please, Dad.’

Mae shrugged, straightened up, committing those two lads to memory: bags, hair, sneery little faces. The last of the latecomers ran past them, ushered in by her classroom assistant (Mr Walls, 29, newly qualified last year, single, previously a gardener, caution for shoplifting aged 13). Mae bent to fix the mismatch of toggles on her coat, and she let him.

‘Thanks for hanging out with me, Bear.’ He squeezed her shoulders. ‘See you next week.’

She ducked him and was gone, off down the path, trying to press into a group of girls he half-recognized. Flicking a hand up briefly as a backwards goodbye. He flexed his fingers a few times in his pockets and headed back to the car.

It didn’t get to him. Saying goodbye and not even getting a hug: it was no big deal. He dealt with assaults and suicides and RTAs, no problem, all the time. Cat C murders, child abuse, DV, the lot. All the fucking time. So, his little girl forgot to give him a hug before a whole nine days away from him, even though five minutes ago she was three years old, falling asleep in his arms as he read The Gruffalo for the eighteenth time? Christ! Take more than that to make him cry.

From the driver’s seat he watched Bear disappear into the building.

Music. He reached round to dig a CD out from the pocket behind his seat, and his fingers closed on a disk in a square plastic wallet. She must have left it there by mistake. He brought it out: Lady Gaga for Bear! on the disk in sharpie, and then under the hole,

(not really, it’s Daddy’s very best CLEAN hip-hop mixtape).

And it was clean, too: he’d checked and double-checked each track, and there wasn’t a single swear. It had taken some doing.

He tucked it into the glovebox, then tried again and found Snoop Dogg’s Doggystyle under a fine layer of fried potato crumbs. It was scratched to shit but last time had played fine up to ‘Who Am I (What’s My Name)?’, which would be long enough to get him to the nick. His speakers were almost as creaky as his brakes, but they were loud, and loud meant a clear head.

Ignition, arm round the headrest to reverse. And off.

All business.

3. (#u079d501d-f43d-5e2f-9341-37d3e850f369)

CC: OK, I think that’s recording … Good. Right, before we begin can we just confirm this because we’ve got a slightly unusual situation here. You have asked for your friend Jodie – our mutual friend, should I say – to be here during this first session?

EP: Yes. Please. If that’s all right.

CC: Certainly, whatever makes you feel comfortable. OK. So, what I’d like to do to begin with is to have a chat about the dissociation, and the range of what you’re experiencing on a daily basis.

EP: OK.

CC: And from there we can move on to having a think about where you’d like me to get you to. Does that sound OK?

EP: Yeah. Yes. That’s fine.

CC: So. A normal day then. How does that start?

EP: OK well, it depends on whether I’ve had a fugue or not.

CC: Tell me about that.

EP: So, um, Siggy sometimes—

CC: Siggy is your alter.

EP: Yeah, sorry yeah my alter, she sometimes kind of takes over. I wake up at night sometimes but I’m not like, actually awake, it’s not me, it’s her. She talks to my mum sometimes, otherwise she’ll just try to go outside, that kind of thing. Sometimes we’ll only know Siggy was up because things will be moved, or lights will be on. Stuff like that. But I always know anyway because I feel her there.

CC: Physically?

EP: Not exactly. I mean, I always feel sick afterwards, sort of achy.

CC: OK, so let’s say you’ve woken up, got up. What happens next?

EP: Well, she’s always there. Just … like I can sort of sense her, whatever’s going on. It’s like she thinks things that I can hear—

CC: Does she speak? Does she have a voice?

EP: Well … no. Not really. But it’s like she’ll get scared or angry or whatever and I know it’s not me feeling those things. Does that make any sense?

CC: Yes, it does. It sounds like what you experience is what I call co-conscious dissociation, which is when a person can feel that they have more than one identity at the same time.

EP: Right. Yes, that’s what it’s like. But the times she gets me up and does stuff with me at night, and … I just have completely no memory of that at all.

CC: OK. I’m getting from the way you’re speaking now that it’s quite distressing.

EP: I just … I don’t know.

[pause: 32 sec]

CC: Would you feel comfortable going into a little more detail about the episodes you have at night?

[pause: 12 sec]

EP: Look, I-I don’t know.

CC: OK: Eleanor—

EP: Ellie.

CC: Ellie. A lot of the people I see, they find it very hard at the beginning. They can feel like … well, they don’t know if they can trust me. Or it might be that they don’t trust that talking is going to help.

[pause: 27 sec]

EP: No. It’s not that. I just know what’s going to happen. We’re going to go through all this, and then you’re going to give up.

CC: Ah, OK. Tell me a bit more about that.

EP: I’m just … like, I’ve tried. You know? I talk to Siggy, I talked to other people, tried medicine and everything. All kinds of stuff. I don’t want to do all of that again. Just tell you all of it and then have you just say that actually you can’t help. Or that you don’t believe me.

CC: Who does believe you, Ellie?

EP: My mum.

CC: She’s always believed you.

EP: Yeah. She’s-she’s seen what happens. The fugues, and – everything.

CC: Anyone else close to you? Other family?

EP: I’m an only child. My dad’s dead.

CC: OK.

[pause: 11 sec]

CC: OK. And was that a long time ago that you lost him?

EP: Yes. Before I was born.

CC: I see. It can be challenging, growing up without—

EP: No. It wasn’t.

CC: You don’t want to talk about your father.

EP: No.

[pause: 31 sec]

CC: OK, Ellie, there’s a couple of things I’d like you to know. Sometimes therapists can be a bit mystifying. They can wait for you to work things out for yourself even if they have a good idea of what’s going on and what needs to shift in order to improve. But that can take a lot of time. In my experience I think it’s best to be up front and tell you what I think is happening, and what we’re going to do to put it right. Seems more honest, that way. Does that sound OK?

EP: Yes. I just want her gone. I want to be better.

CC: I hear you. So the first thing is, the aim of the psychotherapeutic work I’m going to do with you is to understand what’s happened. What I want to do is reduce the conflict between the different parts of your identity, help them cooperate.

EP: OK. I mean, I can’t see that happening, but OK. We can try.

CC: Good. So, the second thing I need you to know is that the kind of issues you’re having with Siggy, they’re something that almost always stem from quite a significant trauma, often something in early childhood.

[pause: 34 sec]

EP: OK.

CC: And so at some point in our sessions we’re going to need to talk about that. What you yourself think is at the bottom of it, how it all started.

[pause: 19 sec]

CC: Would you like us to come back to this at another time?

EP: No.

CC: OK. I understand. The reason I’m—

EP: I just … look, nothing happened, OK? There’s no deep dark secret. She’s just there. I don’t know why. I’m not going to come along here and just suddenly remember some massive, buried … it’s not going to happen. She’s always been there. I just want her gone. OK? I want her to leave me alone.

[pause: 22 sec]

EP: I just want her to leave me alone.

4. (#u079d501d-f43d-5e2f-9341-37d3e850f369)

Ellie (#u079d501d-f43d-5e2f-9341-37d3e850f369)

It felt like she was gone forever. I called Matt again and again but there was no answer.

I checked the time on the wall clock – three hours gone – and then saw the streak of pink highlighter on the calendar. I was supposed to be doing a shift that afternoon, volunteering in the children’s ward in the hospital where Mum cleaned, and Matt worked in the imaging lab. He’d set the whole thing up for me, sorting all the stuff out with the permissions, after I told him how one day I’d like to work with children. But after his effort, I’d managed to miss my slots twice in the last few weeks. The HR person had already come to see me about it, but I couldn’t explain to her what had really happened: that if I went back to sleep after a fugue, I was impossible to wake.

Matt said I should just come clean about it, explain that I had a mental illness. It was a hospital, he said – how could they not understand? I didn’t dare, but I knew then I’d made the right decision in confiding in him.

At first I’d been careful to stick to the rules, to censor myself. Mum knew how serious I was about him, and in his company at least, she approved of him. I’d come home once to find them roaring with laughter over a game of cards: he was genuine, polite, reliable, she said, and nothing like my father. She made me promise not to let myself fall asleep with him, no matter how tired I got, but she was still worried. There wasn’t a man alive who was patient enough, understanding enough, to be with someone who’d always sleep alone. Even good guys can break your heart,she said.

To begin with I said nothing at all about Siggy, but I couldn’t keep the secrecy up for long. There was no boundary where I stopped and she began, and after a few months, I realized I couldn’t be myself without telling him.

Matt had listened to it all. We’d been sitting in front of the log burner in his narrowboat, sharing a bottle of wine. I sat propped against his chest, and I told him the whole story. From the first time Siggy had got me up at night and taken me outside, until Mum, frantic at 4 a.m., found me lying underneath the car. I told him about the exhaustion I got the mornings after a fugue, the grinding headaches, the ten-tonne limbs. I told him everything.

No. Not everything. I didn’t tell him about Jodie.

After my very long monologue, there was a very long silence. And then he’d lifted my head from his shoulder and looked right into my eyes.

‘I’m not going to lie to you,’ he said. ‘I don’t understand this yet, but I’m going to. We’re going to make you OK.’

I told Mum later, and she was silent for a long while. Eventually, she just hugged me. ‘It’s your life,’ she said. ‘Remember to be careful, though. He’s a good guy, but I can’t protect him from her.’

The very next morning, there were bruises all up her arms. I had no memory of what Siggy had done – what I had done. How I had slammed my own mother against a wall and thrown her out of my way.

Like I was an empty coat, Mum said. But it wasn’t your fault.

I heard a sudden movement and I froze, listening, but it wasn’t Mum coming back. Just boxes being moved around downstairs, from what I guessed was the stock room. Our flat was above a shop, an off-licence, and from the way sound travelled it seemed Mr Symanski’s ceiling, our floor, was made from little more than cardboard.

I gave a start. Thin floors.

If I could hear him …

I pulled on my shoes and was at the front door before Mum’s warnings about him sounded in my head. Don’t talk to the neighbours. It only takes one person to suspect us.

What was I going to say? Did you hear me leave the flat in the middle of the night? Because I’ve got a whole load of unexplained injuries and I don’t remember what happened? I stood there for a moment, my forehead resting on the cold glass of the door. Then I took my shoes back off and kicked them sullenly away.

In the kitchen, next to the sink, Mum had left a beaker for me and a carton of orange juice. Forgetting the damage to my hand, I made the mistake of trying to twist the cap. I recoiled and knocked the whole box to the floor where it slopped out across the lino.

Irritated, I opened the safe cupboard under the sink and took out the homemade cleaning fluid and some latex gloves. We didn’t take chances anymore: everything harmful was locked away. I couldn’t even be left alone with a bottle of bleach. I tried all the other doors, out of habit. All locked. Knives, matches, bleach, all beyond my grasp. I snapped on the gloves and clenched and stretched my hands, feeling the thin scabs on the wounds split, reasserting myself over her.

My pain, Siggy. Not yours.

After I mopped up the juice I carried on cleaning, using the soft scourers to attack the rest of the floor, the dented metal sink, the wood-effect laminate of the worktops. I scrubbed until my jaw ached from gritting my teeth. Folded in a corner, Siggy eyed me.

My phone rang, and I pulled off the gloves, my heart leaping as I recognized the first few of digits of the number on the screen. It was the hospital.

‘Matt?’

‘Oh, hi,’ said an awkward voice, a man. Not Matt. ‘Ellie, right?’

I let my eyes close. If someone at his work was calling me, that meant—

‘Listen, do you know where Matt is? Only, we were expecting him in, and he hasn’t shown up.’

I told him – after swallowing the lump of lead in my throat – that I hadn’t. ‘Who is this?’

‘Leon. From the hospital. The imaging lab?’

‘Oh, OK. Leon.’ Matt had mentioned Leon: they’d been working together for a couple of months now and he’d gone for a pint with him after work once or twice, though I didn’t get the sense they were particularly good friends.

‘Did you see him yesterday?’ Leon asked, concern in his voice. ‘Like, in the evening? Because I can’t get hold of him on the mobile, and the guy at his moorings says he’s not there, and with yesterday being a bit … you know.’

‘A bit what?’

The wet sound of him opening and closing his mouth told me he was choosing his words. ‘No it’s … it’s nothing. But look, if you hear from him—’

‘It was a bit what, Leon?’

‘Nothing. Just, you know. Busy.’

Matt hadn’t mentioned anything unusual. Had I even asked? I told Leon I’d call if I heard anything and hung up.

I went to the window, pulling the net aside. The thick cloud of the early morning was gone now, swept clean to expose a sky of cold blue, scarred all over with sharp shards of white.

Wherever Matt was, he wasn’t OK. He wasn’t OK at all.

My eye was caught by movement. I recognized Mr Symanski’s son, Piotr. Maybe a little older than me, mid-twenties and already paunchy. He was a sullen figure, shuffling up the road. I watched him bend to scratch a passing cat behind the ears, and let it weave between his ankles a few times. When he stood, he saw me. Stock still, nothing on his face, staring straight at me for five seconds, ten. More. Then as if he’d suddenly come to his senses, he looked away, got out his keys, and went inside.

I dropped the corner of the net curtain, and stood there blinking, thinking only of that stare. Did he know something? I thought again of going down, speaking to them. But before I could make a decision, I heard movement on our steps outside and the clatter of fumbled keys against concrete.

5. (#u079d501d-f43d-5e2f-9341-37d3e850f369)

Mae (#u079d501d-f43d-5e2f-9341-37d3e850f369)

The Snoop Dogg was damaged worse than he’d thought, so he felt around in the side pocket for anything CD shaped and slipped it in. Turned out to be a demo from a mate of a mate, who Mae vaguely remembered wanting to punch. White guy, gangster lean, called everyone bruv. Mae gave it until after the first refrain, pressed eject, checked for witnesses, and windowed it.

He took a little detour and got a coffee from a new Cuban place on the corner by Acton Central. He ordered short and black on the grounds that it would be fastest and bounced on the balls of his feet as the barista made it up, feeling the snip of unspent energy amassing in his blood. A muted newscast on the screen above the counter was wringing the final drops from an American school shooting, a week old and almost forgotten.

After paying, he got out of there, and had emptied half the scalding caffeine into his mouth before he’d even pulled away. Needing the buzz, needing the lift, because there hadn’t been a chance for a run that morning, either.

He tolerated the flack he got about his thing for exercise. If it made his colleagues feel better about themselves to call him vain, call him a poser, that was their business. But to Ben Mae, exercise had never been optional. Without a run in the morning, without an hour of circuits or weights or anything else in the evening, the noise in his head got too much and he knew where that ended. These days, he could trust himself to recognize that inevitable build-up of whatever-it-was and burn it off in the gym. But age as he might, those years after his dad died of finding himself prowling, angry without provocation, skulking around for a fight or a fuck never seemed that far behind him.

Objectively, he thought, as he slowed for the barrier and flashed the fob at the reader, it was doubtful that coffee helped. Objectively, the right thing to do was to deal with the anger, understand it. Go right back to that dark six months when he changed from a normal teenage boy and into a thug, to the point where his life could have gone either way. Tear the thing out by the root.

But who would he be then?

Leaning back in his desk chair, Mae transferred the phone to the other ear, then rubbed the stubble on his head up and down hard with the palm of his hand. Around him, the office was already in the full throes of post-briefing activity.

‘But he’s still missing,’ the woman at the other end of the line was saying, her voice rising towards the inevitable crack. ‘He’s still gone. We can’t cope with this not knowing. My poor kids—’

Her name was Charlotte, wife of Damien Hayes. Widow, almost certainly, of Damien Hayes. Mother of his four kids. Six months previously, Mr Hayes had left the final shift of his job at the vehicle plant just outside Uxbridge, driven his car half the way home, abandoned it, and disappeared. He left no note but, as it unravelled, it was a tale that told itself. The poor bastard had been in the red by almost forty grand, had defaulted on his last half a dozen mortgage payments and then, just to kick the man while he was down, the plant had laid him off. Mrs Hayes had only discovered in the weeks following his evaporation that he left behind no savings, no pension, and no insurance.

‘Mrs Hayes I promise you we’ve done everything we can—’

‘Done? Done?’

Mae winced. ‘Doing. We’re doing everything—’

‘Are you? Like what? What have you done, since you made this call a month ago? On our last weed date,’ she said, bitterness curling at the term.

He lifted the top sheet of the stack of paper in front of him and stifled a sigh. Four more calls exactly like this one, scheduled for today, but there was no news, no concrete developments in a single one of them. Thing was, in this business no news was bad news, even if – especially if – it wasn’t the kind of bad news that had an event attached, a clear and obvious trauma that could at least heal cleanly. In the majority of the cases he had the misfortune to head in his current role, the misper was there and then they were not. No stages of grief to work through, no ritual to mark the end of the life. The family around them remained in stasis until eventually, secretly and ashamedly, they started to long for news of a body being found.

‘I’m afraid without new information, there’s really not much else—’

‘So you’ve given up?’ And right on cue, the sob. ‘If you had any idea of what this is doing to us.’

Mae pressed closed his eyes. They always said that. Every one of them, and not just in Missing but in everything he’d ever been assigned. Murders and rapes and robberies, beatings, the lot. Nearly always, they were right. No, he’d never been sexually assaulted. Hadn’t suffered the violent death of someone he loved. Since he’d been leading Missing, though, the accusation that he didn’t know how it felt had been harder to take. But he never let it out, never put them right, not even to McCulloch when she’d given him the gig. Especially not then.

He was going to need that run, he decided.

‘Look, Mrs Hayes,’ he said, quietly. ‘Charlotte. I’ll put some calls in to the charities again, OK? See if there’s anything new there. Sometimes there are delays with them putting stuff through to our systems. I’ll see if I can extend the hospital checks a bit. I’m not promising anything,’ he added as he heard her intake of breath, but the hope had already returned to her voice.

‘Yes. Please.’ She paused to delicately blow her nose. ‘Anything you can do.’

A red light started blinking on his desk phone. Mae straightened, dispatched Mrs Hayes as sensitively as he could, and answered it.

‘Should I send down a written invitation?’ The gentle Hebridean lilt of DCI Colleen McCulloch.

Mae glanced at the time. Shit. ‘Sorry, ma’am. On my way.’

He bombed it up the back steps and made McCulloch’s floor in about thirty seconds flat. He slowed to a stroll as he passed her glass-fronted office for the sake of some semblance of cool, then went in.

‘Sorry ma’am,’ he muttered, ‘difficult call to a—’

‘Spare me,’ she said, nodding over her glasses to the door, which he dutifully closed. Standing at ease the other side of the room was a statuesque, stony-faced uniform, a woman. He nodded an acknowledgement: he’d seen her swinging kettlebells around in the basement gym. She had cropped, bleach-blonde hair and had to be a good 180 lbs and rising six foot. The kind of woman who occupied every inch of herself. Lot of tattoos, he’d noticed: not that they were visible now.

McCulloch cleared her throat. ‘How’s it been going downstairs these past few weeks, Ben? Haven’t seen you since I went to Egypt. Ooh, talking of which,’ she said, turning to dig something out of a drawer, ‘got you one of these. From the pyramids.’

He caught the paper bag just before it struck him on the head – she was nothing if not a good shot – and opened it. Inside was a small, stuffed camel, made from some kind of felt. He closed the bag. ‘Uh, I’m honoured?’

She shrugged. ‘Don’t be, it’s cursed. Paid the extra, thought why not.’

The uniform bit back a grin.

McCulloch had arrived on the force six months after Mae: they’d both started out in Sussex, albeit at very different levels of seniority. She’d been a hard sell to the whole department, straight in from civvy street to detective inspector, leapfrogging not only a whole generation of CID sergeants who’d been waiting in the wings – some of them – for literally years, but also sprinting past the two long years of uniform service. She was part of a new Philosophy of Recruitment, they’d been told, which recognized outside skills and combatted red tape. Translated: stuffed suit. Decoded: clueless leg-up wannabe. The entire team had been rooting for her to fuck up her first major job, but she’d steered the investigation to a solve with the cool, effortless ease of a seasoned skipper. Those who still remained unconvinced waited, hoping for a trip up to ratify their prejudices. It never came. Problem was, she might have come from some woolly sounding NGO background, but she was also bulletproof. She was bright as a supernova, knew her PACE back to front, her Murder Manual inside out and recited her CPS guidelines with her eyes closed. She bit only when antagonized, and she called every single decision with blistering speed and perfect judgement. What made all of that worse was that she was the most eminently likeable boss any of them had ever had.

And after Brighton, when his immediate superior had been sacked and Mae himself had been given a month’s suspension, she’d moved to the Met to take the helm at Brentford and had been in the role ever since. It was McCulloch who’d encouraged him to relocate, to come and work in the capital with her, and with nothing on the coast to stay for, he’d eventually relented.

McCulloch pushed aside the wireless keyboard to make room for her tailored-shirted forearms and took a sip from a steaming mug of her ubiquitous mint tea.

‘Detective. Ben.’ She gave him a broad smile that pushed the plump cheeks into freckled bulges and exposed the quarter-inch gap between her front teeth.

‘Ma’am.’

‘I have a job for you.’

‘That’s very kind, Ma’am, but I have seventeen open—’

‘Call it an expansion of your already impressive burden,’ she said, waving his reluctance away. ‘Tell me, how long have we been in the force?’

She knew the answer to this. She knew everything. Where he’d been to school, his bench press PB, and the name of his first pet. Not for the first time, it occurred to him she probably even knew about the dark years after his mum disappeared, even though he’d always managed to keep a half-step ahead of the law.

‘Eight years, Ma’am.’

She pulled the keyboard back over. ‘I’ve had some applications. Some of your colleagues putting themselves forwards for inspector.’ She was looking at her screen now, scrutinizing it for his benefit. ‘But I’m not seeing your name here.’

‘I’m happy where I am.’ He glanced at the uniform, wondering where this was going.

Ignoring him, McCulloch folded her arms and leaned back in her chair, addressing the ceiling. ‘You see, Ben, when we rank people up, we like to see people proving themselves as leaders. Showing managerial qualities.’

‘I’m not looking to rank up. Sergeant suits me fine.’

‘I see. Well anyway. Detective Sergeant Mae, this,’ she said, gesturing at the mystery uniform, ‘is DC Catherine Ziegler.’

‘Right.’

‘And she,’ McCulloch went on with a twinkle of the eyes, ‘is going to be your new TI.’

Mae took the hand extended towards him, met her eyes, and briefly returned a rough approximation of the broad, open smile she gave him. Thinking, shit. Trainee Investigator meant a shadow. Constant company.

‘Hate to say it, Ma’am—’ Mae started, but he was silenced with a finger held aloft.

‘Then don’t.’ McCulloch folded her arms across her chest, assessing the two of them like a mother at a playdate. ‘I understand that Catherine—’

‘Kit,’ the younger woman put in.

‘I understand that Kit passed her NIE with stand-out results,’ McCulloch was saying. ‘So when HR asked me for a mentor, I looked around the floor and I thought to myself, Colleen, who have you got with the kind of skills and characteristics to drive a talent like that? I thought, who’s willing to take the time to make opportunities for a new generation of detectives?’

My arse you did, Mae thought. Try, who have I got who’s been coasting for getting on for half a decade, without a foot of movement in any direction? Who have I got spare? Not that he could begrudge it. If it had been DCI Anyone Else, this would have been a punitive move. But she’d called it right, he couldn’t deny it. Sure, he’d sat the exams and taken the promotion to sergeant when he came back from his absence, even though he was fairly sure she’d swung it for him. After that, he’d kept his head down. He’d gone where he was sent, done the courses, gone through the motions. But it didn’t take an HR review to see he’d been treading water since … since before … since before it had all gone wrong. He pumped his fists tight and loose, tight and loose at his sides, dispelling it.

‘I thought Missing would give Kit a nice easy start,’ McCulloch told him, ‘and you can get her used to the juggling.’ Turning, she added, ‘Ignore the grumpy exterior, Kit. They’re all the same: like to pretend they’re brooding mavericks but buy them a bacon roll and they’re anyone’s.’

DC Catherine Ziegler glanced at him to gauge his reaction, and he conceded a reluctant twitch at the corners of his mouth. Might as well be decent, because he could see he wasn’t going to win this.

‘Squirt of HP and we can talk.’

‘Then that’s sorted,’ the boss said. ‘And don’t forget your camel.’

McCulloch was already pulling the keyboard close, on to the next thing. She started typing, then looked up. ‘What are you waiting for, lollies? Run along.’

But he could tell from the meaningful, encouraging look on his boss’s face as she shooed them out of the door that there was nothing malicious about this. He wasn’t despised, he was pitied. This was intended to aid his personal development. She thought this was what he needed.

And as Mae left the office, with his new TI following behind like a rugby-shouldered Valkyrie, he hated McCulloch for always being right.

6. (#u079d501d-f43d-5e2f-9341-37d3e850f369)

Ellie (#u079d501d-f43d-5e2f-9341-37d3e850f369)

Mum’s outline was distorted through the bumpy glass as she bent to retrieve the dropped key. She cursed, but it was the weakness in her voice that made me certain that something was not good.

She came inside, her hair stuck across her face in muddy streaks as she unbuttoned her coat.

I took it from her and asked, ‘Did you find him?’

‘I’m sorry, baby,’ she said. ‘No luck.’

‘So where have you been?’

‘Just down to the boat, but he’s not there. I thought I’d get a run in on the way back.’ She started stripping off, moving quickly, her T-shirt slopping to the floor where she dropped it. Leggings going the same way; socks, the tube-bandage support she used on her dodgy knee. The bare wet flesh of her arms and torso was paling from the cold and stiffened with goosebumps, ropes of muscle tensing underneath as she moved.

She found a plastic bag and shoved the clothes inside. ‘Don’t look so worried, love. He’ll be … I don’t know. Out for a walk? Or out taking pictures?’

‘He’s supposed to be at work. They called, Mum. He’s not there.’

She was suddenly serious. ‘What did you tell them?’

I shrugged. ‘Nothing.’

‘You didn’t say …’ she started, her eyes drifting down the hall, to my bedroom door.

‘That I smashed my way out of my room in the middle of the night and I don’t remember it, and I’ve woken up covered in bruises? No. I kept that to myself.’

‘OK. Stupid question. I’m sorry.’

I followed her into her room. She unlocked the box beside her bed where she kept tools, matches, things she couldn’t leave lying around. She removed a pair of nail scissors and started cutting her nails down.

‘So where is he?’

She sighed. ‘I don’t know, Ellie.’ Finishing her own no-nonsense manicure, she gestured for my hand, which I gave her. ‘There’s nothing to say you had anything to do with it,’ she said, trimming the white from the tops of my nails.

I tried to pull away. ‘Mum, if you found something—’

‘I didn’t. It’s nothing.’

‘But it’s not, is it?’ I said, disentangling. ‘What if Siggy … what if it’s happened again?’

‘Don’t. Please. Just don’t think about it.’ Mum took a deep breath, held it, as if bracing for something. ‘And even if something has happened. We should definitely sit tight,’ she said at last.

I broke free, stood up, went into my room.

‘Where are you going?’ she called.

‘I’m calling the police.’

It took her about half a second to come after me. ‘No.’ She grabbed the phone out of my hand. ‘No. That’s not the right play. Not at all.’

I stared at her. ‘Play? He could be—’ I stopped myself from saying it.

‘But he’s not. OK? He’ll be fine. There could be any number of explanations. He might have just gone on a trip.’

I folded my arms. ‘Right. A trip.’

‘Maybe he wanted a break.’

It took me a moment to process that. ‘From me?’

She shrugged apologetically.

‘You’re saying this is just him breaking up with me?’

‘Men. They eat your pies and tell you lies,’ she offered. It was our joke, the phrase with which every conversation we’d ever had about my father would eventually end. But I wasn’t in the mood, and she saw it. ‘I’ve got to get to work, sweetheart.’

‘Me too. I’ve got a shift with the kids. What?’ I said, when she made a face.

‘Maybe best call in sick?’

‘What? Why?’

She spread her hands but didn’t answer my question. Didn’t need to. She didn’t want me to go because she wanted to keep me out of sight.

She thought I’d killed him.

Had I killed him?

After she left, I stood in the hall, taking in our dingy home. Nothing to mark it as ours. Our rent paid in cash – everything always paid in cash – so we could leave at a moment’s notice if anyone came knocking on the doors, asking questions about me, about Jodie. Mum used a different name, Christine Scott, wherever she could. She chose agency work over proper contracts because it meant wages in cash, and there were always agencies with a relaxed approach to background checks.

Our whole existence, Mum’s jobs, everything we did, was built around Siggy. Everything in her life was about me: boyfriends had been dismissed when they started to ask too many questions, jobs abandoned when demands were made that took her away from her duty to me. She’d given up everything just to cover my tracks and keep me happy, or at least keep me safe. Even before Jodie, we’d never put down roots, but since? I’d lost count of the number of times we’d moved. Always in a hurry when someone recognized her. It made her curse herself for ever having had success: if she’d never been on TV, it wouldn’t be half this hard.

I padded back to where the calendar hung on the wall: my shifts marked in pink highlighter.

It’s not like it’s actually a job.

I was coming up twenty years old. I was the same person I’d been at fourteen. Afraid of everyone and everything, locked into the bedroom in my mother’s flat every night for fear of what I might do if I was free. Whatever she said about my value in the world, I was jobless, dependent.

But I had Matt. Loving, understanding Matt. Patient. Blindly at risk.

I made a promise right there and then, that if Siggy had hurt him in any way, that I was ending it. I’d take her with me. I didn’t care.

Nobody wins, Siggy. Do you hear me? This ends here.

Siggy heard. Her black eyes flashed wide, but she shrank back, flattening into the shadows. Didn’t move, not a moment of a challenge. She’d been around me long enough to know when I meant what I said.

7. (#u079d501d-f43d-5e2f-9341-37d3e850f369)

Mae (#u079d501d-f43d-5e2f-9341-37d3e850f369)

Mae arsed the access door open and climbed the steel steps, steep enough to make the toe of his size twelves clang on the underside of each one as he ascended. The fire door at the top swung open and banged against the wall. He squinted as he went out. Bright. Stretching his arms out, opening his chest, he made a circuit of the flat roof then leaned out across the suicide bars, looking down to the street below.

He bit into his bacon roll. He’d lost DCCatherineZiegler shortly after she’d handed it to him in the canteen. Or maybe not lost, exactly, more turned and walked away from, without checking she was behind him.

He rarely ate in the canteen. The food was adequate, but the place was rammed full of cops. For him, up here was the place to be. He chewed slowly, felt the cold on his skin, had a stretch. Movement at the edge of the roof caught his eye: from the door of the shed-like block that housed the steps came his new TI. Striding out across the felt roof like an uncaged animal.

‘Sarge,’ she called, ‘got a sec?’ She carried a sheet of paper, the other hand visored across her forehead against the sharp November sunshine.

Mae jerked his chin to greet her, then chased a dot of brown sauce from the corner of his mouth with his tongue.

‘Love it up here, too,’ she said, tilting her head back to the open sky and filling her lungs. An exchange of car horns sounded, and she glanced over the edge of the building.

She laughed softly. ‘Funny little bastards.’

‘Who?’

She shrugged. ‘I don’t know. All of us.’

Mae followed her eyeline, down to the stop-start of traffic by the junction of Boston Manor Road. Tiny faraway people pottering around, in and out of shops and cars and offices, fluid masses of them sloshing out of buses and onto the streets where they dispersed easily, innocuous as peas from a split bag. When he looked back at her, a smile had risen over her face.

‘Did you need something, Ziegler?’ he said, popping the last mouthful of the butty into his mouth and balling up the bag.

‘Please don’t call me by my surname, Sarge. Makes me feel like I’m at boarding school.’ She followed him back out towards the steps and passed him a printout. ‘Got a new one in. Misper.’

Mae glanced at the sheet she was holding out, swept his eyes over the first couple of lines. Just a log from a triple-9. He handed it back, frowning.

‘Give it to uniform. If it’s already marked as low-risk they’ll do the work-up. They hand it over as and when.’

‘Usually, yeah. But I thought the name might be of interest,’ she said.

He sighed, took the sheet back. They went down the metal steps into the blue-walled normality of the nick. ‘What was the name?’

‘Matthew Corsham,’ she said, peeling the top sheet off, handing it to him. ‘White male, twenty-six, some kind of technician at Hanwell Hospital. No history of missing, not a pisshead or a junkie.’

He nearly choked. ‘I think that’s supposed to read, no history of drugs or alcohol abuse.’

She shrugged and moved on. ‘The workmate who called it in said he’s worried because it was the guy’s last shift yesterday, dismissal was a bit out of the blue and he was distressed. Corsham promised to take his work computer back, and didn’t show, which is very out of character because he swore he’d be there and he’s very reliable. So the workmate calls, but it goes straight to voicemail, so goes round to his place – he lives on a boat, just up towards Isleworth – and he’s disappeared.’

Mae scanned the text for dates. ‘What timescale we talking?’

‘It’s only half a day. Leon, the colleague, says he spoke to him yesterday and he was really agitated about having lost his job.’

‘Half a day? Give the bloke a chance, Christ! They never heard of a bender?’

‘I think that’s supposed to read, excessive period of alcohol consumption.’

Mae gave her a look. ‘And anyway, I don’t know a Matthew Corsham. Am I supposed to?’

‘Not him. The girlfriend.’

Mae returned his eyes to the document. And his heart skidded to a stop. Eleanor Power.

Kit leaned against the doorframe. ‘Rings a bell, right?’

It wasn’t a question, and they both knew it. He gave her a quick glance. ‘You like your homework, then?’

He read the whole thing en route to his desk, walking on autopilot. Not taking his eyes from it until he was in his chair, screen on. A dull wince, the kind that sits there for years until it’s so familiar it almost goes unnoticed, tightened in his chest.

Yeah. It rang a bell.

Mae pulled the keyboard over, put the name through the PNC. Fourteen Eleanor Powers in the country, three in London.

Could it really be her?

‘I’ve run her already,’ Kit told him, reminding him of her presence behind his chair. ‘No records on her, DWP, electoral roll, nothing. Hasn’t had contact with a GP in five years.’

It figured. Five years meant 2006. The year everything fell apart. Eleanor, Ellie, who had seen Jodie Arden getting into a car the night she went missing. Ellie Power, whose mother held her hand and finished her sentences for her when she was too upset to speak. Who was consumed with the irrational belief that her friend’s disappearance – her death, Ellie believed – was her fault. To the extent that, one afternoon, after the session of questioning that would end up being replayed and dissected in the tribunals that lost DS Heath his job and nearly destroyed Mae’s career, she decided that her imagined guilt was unbearable. She followed that conviction through with such brutal decisiveness that Mae was unable to hold it together at work the next day, or the day after that. He’d never gone back, not to his old job, not to any of the spots they’d offered him in Traffic or Custody. Not to anything in the Brighton and Hove district. Not to anything on the Sussex force at all.

But there was one other tiny detail. One minor footnote that he hadn’t come across before or since and would happily never come across again, not least because it was this that discredited her in the eyes of the CPS and collapsed the entire case against Cox: Ellie Power suffered from Dissociative Identity Disorder. He felt the fine hairs on his arms lift as he recalled the specifics of it. How according to her own testimony, sometimes she did and said things, went places that she couldn’t remember. Stopped being Ellie Power at all and became – someone else.

Siggy. The name sounded like a whisper in his head, crept like insects on his skin.

He rubbed his palm over the stubble on his scalp and willed his heart to decelerate.

Kit, oblivious, reached over for the mouse and clicked through the pages. ‘Coincidence she turned up here, on your patch. Nothing on her since your missing prostitute, and now—’

‘Jodie Arden was a fucking child.’

She lowered eyes. ‘Sir.’

Mae sighed. He leaned forward, started lifting the various notes and notices pinned to the blue hessian-fronted panel at the back of his desk. Under several sheets of stuff he’d been meaning to read, there was a photo. He pulled the rusting pin out.

Kit leaned close. ‘Is that her?’

It was a head-and-shoulders of a dark-blonde girl in a dress that fastened at the neck: Jodie Arden at her cousin’s Bat Mitzvah. It was the shot they’d used in the police press packs, but the media had rejected it in favour of a racier snapshot taken by a friend on a night out, that showed her in an altogether different light. The papers had treated her like an adult, which meant printing whatever they wanted. She’d missed the social media explosion by a hair’s breadth, but the hacks had got hold of everything, nonetheless. Including the drinking, including the drug use. And including the fact that she had been sleeping with a much older man, a psychotherapist by the name of Charles Cox, who just so happened to be treating her best friend Ellie. Worse still, Cox also just so happened to be dating Jodie’s own mum. It was this man who owned the car Ellie Power saw Jodie climbing into before she disappeared off the face of the planet. Her disappearance had been news for all of two days, after which another girl in another part of the country had gone missing. A nicer girl, Aryan and clean, a girl who’d volunteered in Uganda and had a place at Cambridge and played the oboe or whatever. With no new information, Jodie Arden had just become another statistic, one among thousands of almost-adult runaways who slipped through the cracks.

‘She was a week off eighteen when she disappeared,’ he said, carefully. ‘I don’t know what you were like, but I sure as hell wouldn’t fancy being judged for life at that age.’

Kit put her hands up. She ventured a tentative laugh. ‘You always this heavy first thing on a Monday?’

‘You just wait till end of the week,’ he said, replacing the photo. ‘I’m an unstoppable gag machine by Thursday lunch.’

‘Right. Well, apologies.’ She gathered up the paper she’d delivered, giving him a sideways look that he couldn’t interpret. ‘Just saw the name and thought you’d be interested. Given your involvement.’

‘Ancient history, to be honest.’ He stood up and straightened his shirt. ‘Come on.’

‘So we are looking at it?’

‘You’re the trainee, so I’m training you. Got to start somewhere.’ Good thing about rank was how you didn’t have to explain yourself to anyone under you. He swept his jacket off the back of his chair and felt in his drawer for a tie, then remembered something. ‘You got a change of clothes?’

Kit frowned, shook her head. ‘Not apart from my gym stuff. Why?’

‘Best ditch the uniform. There’s a plain-clothes store down by the armoury, you can get the key from the guy in Evidence. Find something there, OK? Meet me in reception in five.’ He flipped the collar of his shirt up and gestured an after you.

8. (#ulink_77c71461-6b7c-5800-873c-67068e78a588)

Ellie (#ulink_77c71461-6b7c-5800-873c-67068e78a588)

I stood back from the door, head on the side, to admire the result. Cosmetically at least, my doorframe was OK now. Between the tub of wood putty and a few scraps of sandpaper I’d found, I’d rebuilt the splintered section back up and shaped it to match the contour of the rest. There had been an inch of gloss paint left in the tin from last time it had needed repairing, and I’d done a fair job. I was proud of it. Mum would be pleased.

I felt my shoulders drop as I thought how Matt would be proud, too. I’d managed to convince him I was pretty handy with repairs the first time I’d gone to his narrowboat. It was about a month after I’d first got talking to him at the hospital while I waited for Mum to finish her shift. For weeks, we’d accidentally-on-purpose bumped into each other before he properly asked me out. Our first real date was on a Saturday afternoon: a lazy lunch at a riverside pub. Matt invited me back to see the boat afterwards but had forgotten that he’d been halfway through laying new floorboards until we went inside.

‘Oh god, state of the place,’ he said, shoving the mess of cushions on the built-in sofa up to one end to clear a space for me. ‘Sorry, not a great start.’ He started lugging the new boards across from where they were propped by the log burner, roughly laying them into place to give us something to stand on.

I sat where I was shown, but raised an eyebrow, flirty from the wine. ‘Start to what, exactly?’

He glanced up, embarrassed, ‘I meant, I—’

Nudging him with a toe, I put him out of his misery. ‘Kidding.’ And he laughed, and it felt good. Then, seized with the urge to show off, I got to my feet, rolled up my sleeves, and picked up a hammer from a pile of tools in the corner.

‘Let’s do it, then,’ I said, indicating the boards. ‘I’ll help you get this floor down.’

He bit the corner off a wry smile. ‘You don’t strike me as the woodworking type.’

‘Stronger than I look.’

‘Oh yeah?’ He grinned, ran his eyes over me. I let him do it, my hands on hips, weighing the hammer in my hands. After that, it was a matter of pride to prove it.

The memory of it split like a burning frame of celluloid the moment I heard the front door. I glanced at the time: Mum wasn’t due back for another half hour.

She burst into my bedroom. ‘Has he rung?’

‘No. I’d have told you—’

‘OK. All right,’ she said, slumping slightly.

‘What’s happened? How come you’re early?’

‘I swapped cleaning sectors with Angie so I could leave early,’ she said, then she told me how she’d gone to the photographic lab where Matt worked, to see if Matt had been there. ‘There were two blokes talking outside his office, one of them said Matt’s name, so I hung around. He said he’d been to find Matt, hadn’t got anywhere, so he’d called the police.’

It was probably Leon, I thought, the friend who’d called me before. ‘But the police weren’t actually there.’

‘No, but—’ she made a gesture with her hands, flustered. ‘Look – I just – are we still OK here? I mean, you’ve been careful, even with Matt, right? They’re not going to find the address?’

I tried to hold her eye, but I couldn’t.

She gaped. ‘Oh no, Ellie. What did you do?’

‘I’d been meaning to tell you,’ I said weakly. ‘It was when we were applying for the volunteering.’

‘You gave them our address?’

‘No, he did it. He didn’t know not to. I could hardly tell him not to, could I? How would I explain it?’

‘Well, fuck!’ She threw her free hand up. ‘Great! Wonderful, good work!’

I wanted to say sorry, but she hated me apologizing.

‘I said this would happen. I said, the first time you brought him round. It was too big a risk. Didn’t I say?’ She went into her bedroom and started to rush about, pulling off her tabard and stuffing it into the washing basket. Then as if remembering, she went out to the kitchen and returned with the bag containing the wet clothes from that morning.

As calmly as I could, I said, ‘Mum. Tell me what’s going on.’

‘Nothing! I just want to be prepared.’ She roughly pulled a shirt on and went to the dressing table, plonked herself down and pulled out her make-up. ‘They’re going to come here, aren’t they? The police. And they’re going to ask questions.’

‘So we answer them.’

‘Yeah?’ She spun round, a blob of foundation balancing on fingertip halfway to her face. ‘With what?’

‘How about the truth?’

‘We don’t know what happened! We’ve got no fucking idea what the truth is, have we?’

I bit into my cheek until I tasted blood. I wasn’t going to cry.

Mum applied the make-up, sighed and got up. She went to the bed and patted the place beside her.

I sat, and she put an arm around my shoulders. ‘Come on then.’ She squeezed. ‘They’re going to come, so let’s think what we’re saying. Where had you been, last night?’

‘The pub, but—’

‘Which pub?’

‘Mum, why are we even—?’

‘Which one?’

‘The Windmill. He had an IPA; I had a lemonade.’

‘And people saw you.’

‘Yes. No. Not people we knew.’

‘You weren’t arguing?’

‘No! Why would we be?’

She sighed heavily and went back to the mirror, flipped open a compact. ‘They’re going to ask you this, Ellie. You need to get this right. If they get a whiff that you might be hiding something, we’ve got trouble. They’re already going to have linked you to … what happened before. You do understand that, right?’

‘I’m not hiding anything!’

She raised her eyebrows, then moved her gaze pointedly to my neck. Gave a loose, open-handed gesture to my shoulder, my hip. Siggy shuddered in the aches, as if she was part of them, like they were hers.

Quietly, I said, ‘I’ll just tell them what happened.’

‘About the bruises?’ she said, incredulous.

‘He might be somewhere right now needing help, Mum!’

‘You can’t talk to them. Not yet. Not until we know what’s happened.’

‘But that’s what they do! That’s what the police do, they find out what happened!’

She said nothing to that, but the rise of her eyebrows said, not always. I looked away. If there was one thing I did not want to be talking about right now, it was Jodie Arden.

My eyes lighted on the bag of wet clothes from the morning. ‘What are you going to do with that?’ I asked, nodding to it.

She peered into the mirror. ‘I am going,’ she said, lifting her lashes now with the mascara wand, ‘to incinerate it.’

I waited for her to face me, to grin. But she wasn’t joking.

‘What did you find, Mum? This morning?’

An infinitesimal pause. ‘Ellie—’

And then, from outside, we heard a woman’s voice. ‘This one. Over here.’

We both stood up, fast. She had turned towards the sound but swung back to face me, hands on my shoulders, pulling me into a hug.

‘Listen to me,’ she said, her voice dropping to a whisper. ‘Let me talk to them. We can make sure they look for Matt properly, and maybe it’ll all be fine. But it wasn’t before, with Jodie, was it? And if something has happened to him, and if you – Siggy – had anything to do with it, we need to control this as best we can.’

Three knocks at the door.

‘You are a good person, Ellie. We are good people. We’ve done our bloody best. I will not allow that bitch to ruin your life, or mine.’ She brought her mouth right against my ear, and in a vicious whisper she said, ‘Do you hear me? Siggy? You’re not having her. You’re not going to take my daughter.’

From the other end of the corridor I could hear a second voice, a man, calling through the front door.

My mother touched my face. ‘Not. A. Sound.’ And then she left the room, closing the door softly behind her.

9. (#ulink_ff0f5615-6040-5edc-8018-83e1d51a5d0c)

Mae (#ulink_ff0f5615-6040-5edc-8018-83e1d51a5d0c)

Mae knocked again.

Cold spiked in the morning air, and the sky above Abson Street was a flat, formless grey. Kit, looking distinctly uncomfortable in a borrowed pinstripe skirt suit, took a step back to assay the building, intermittent clouds of breath forming in front of her face. She stretched, then pressed her fists into the small of her back, wincing.

He cocked his head. ‘Been fighting?’

She let out a small grunt and straightened up. ‘Roller derby.’

‘You’re kidding.’

Kit grinned. ‘Nope. You’re looking at west London’s fourth-finest blocker.’

He’d seen bruises on her legs before, at the gym, and wondered what her sport was. Hockey, he’d guessed, or rugby possibly. But roller derby was something else. Explained the tattoos, too. He tried extremely hard not to think about her in war paint and fishnets. Extremely hard wasn’t hard enough.

‘You play round here?’ he asked, bending to call through the letterbox. ‘Ms Power? Ellie?’

‘Sure. Another reason that I’ll hate you forever for making me wear this—’ she gestured at her skirt, ‘monstrosity. I look like I’m selling insurance. I’ve got a rep to protect. This is my “hood”.’ She accompanied that with some kind of gesture that he guessed was supposed to be gangsta.

‘Straight outta Acton,’ he offered, but she just frowned, too young for the reference. ‘Never mind.’

There was the scrape of several locks, and the door opened to reveal a lean, serious woman in her fifties. For just a moment, she gave them a warm smile that didn’t match the restless eyes, and he remembered her in her entirety: the feeling that she always had a mask up, was always trying to calm herself down, keep something in.

Christine Power.

‘Can I help you?’ she asked. Then she recognized him. ‘Ah. DC Mae.’ The finest splinter of ice in her voice.

‘It’s DS now, actually. How are you, Christine?’

She didn’t answer the question. This was the moment to say she looked good, that she hadn’t aged. But the truth of it was that every minute of the five years since their paths had last crossed was in stark evidence in each crease of her face, in the near-complete greying of her hair.

Kit cleared her throat.

‘This is DC Ziegler,’ he said. ‘She’s a Trainee Investigator.’

Christine pulled her gaze away from Mae and greeted Kit, turning on the smile that reminded him how she’d been semi-famous once. A reporter, back when women covering international stories were vanishingly scarce.

‘We’ve come for a chat with Ellie. Is she in?’ he asked, taking in what he could of the corridor behind her, given the lack of light. ‘We’re concerned about the whereabouts of a Matthew Corsham?’