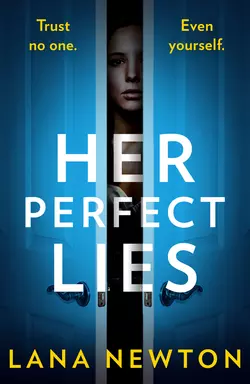

Her Perfect Lies

Lana Newton

TRUST NO ONE. EVEN YOURSELF. __ ‘Sucks you in from the first page, with twists and turns that will leave you gasping for air!’ Netgalley reviewer, 5***** __ When Claire Wright wakes in hospital, she doesn’t recognise the person staring back at her in the mirror. She’s told that she has the perfect life: she’s beautiful, famous, with a husband and a house to die for. But Claire can’t remember anything from before the devastating car crash that’s left her injured. And now she’s surrounded by strangers, saying they’re her family and friends. As Claire discovers the person she used to be she must also unravel the mystery that surrounds the accident. But the more Claire uncovers, the more she will be forced to face up to the dark secrets from her life before… ___ What readers are saying about Her Perfect Lies: ‘Awesome psychological thriller with edge of your seat suspense. If you're planning to read only one psychological thriller this year then make it Her Perfect Lies!’ ‘Unpredictable and full of suspense, this engrossed me from page one. ’ ‘Suspenseful and full of mystery!’ ‘WOW! I didn’t see that coming! So many twists and turns; I couldn’t put the book down!’ ‘An entertaining and gripping book that kept me on the edge till the end. ’ ‘Loads of mystery, twists and turns and filled with suspense!’ ‘This book caught hold of me and had me hooked from the start. I was literally on the edge of my seat reading this book!’

About the Author (#u960d4df5-c19b-5e90-ab30-9b0beadc82b8)

LANA NEWTON grew up in two opposite corners of the Soviet Union – the snow-white Siberian town of Tomsk and the golden-domed Ukrainian capital, Kyiv. At the age of sixteen, she moved to Australia with her mother. Lana and her family live on the Central Coast of NSW, where it never snows and is always summer-warm.

Lana studied IT at university and, as a student, wrote poetry in Russian that she hid from everyone. For over a decade after graduating, she worked as a computer programmer. When she returned to university to complete her history degree, her favourite lecturer encouraged her to write fiction. She hasn’t looked back, and never goes anywhere without her favourite pen because you never know when the inspiration might strike.

Lana’s short stories appeared in many magazines and anthologies, and she was the winner of the Historical Novel Society Autumn 2012 Short Fiction competition. Her novels are published by HQ Digital, an imprint of HarperCollins UK.

Lana also writes historical fiction under the pen name of Lana Kortchik.

To find out more, please visit http://www.lanakortchik.com (http://www.lanakortchik.com)

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/lanakortchik (https://www.facebook.com/lanakortchik)

Twitter: https://www.twitter.com/lanakortchik (https://www.twitter.com/lanakortchik)

Her Perfect Lies

LANA NEWTON

HQ

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

First published in Great Britain by HQ in 2019

Copyright © Lana Newton 2019

Svetlana Newton asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

E-book Edition © November 2019 ISBN: 9780008364854

Version: 2019-09-11

Table of Contents

Cover (#u8021ca52-feb0-581a-92fa-cb7c84b62ec8)

About the Author

Title Page (#uaedf06e7-2e72-57f8-b4e7-188722352287)

Copyright (#u957874b4-df29-57c2-88c4-b8326c0504f6)

Dedication (#u9020fdcf-e201-51d9-8b55-550aa42d338d)

Part I

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Part II

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Epilogue: A Year Later

Acknowledgements

Dear Reader … (#litres_trial_promo)

Keep Reading … (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher

For Sal, the bravest of the brave

Part I (#u960d4df5-c19b-5e90-ab30-9b0beadc82b8)

Chapter 1 (#u960d4df5-c19b-5e90-ab30-9b0beadc82b8)

A stranger watched her from the mirror. Grey eyes, pale lips, blonde – almost white – hair, as if bleached by the sun, a face she felt she had never seen before. The only thing she knew about this stranger was her name.

Claire. They said her name was Claire.

They told her other things, of course – things she found hard to believe. She was famous, touring around the world with the largest ballet company in the country. The nurses talked about her as if they knew her. One had even seen her perform, in far away Australia of all places.

Through mindless hours in her hospital bed, she imagined herself on stage in front of thousands. Impossible, she would whisper, the stranger in the mirror nodding in agreement. Yet, there were pictures and videos to prove it. She peered at herself in the photographs, as Odette, Sugar Plum Fairy, Cinderella. Dazzling costumes, elegant posture, long limbs. Was it really her? She looked at the twirling doll on the screen of her phone until her eyes hurt. Impossible, impossible, impossible.

Tchaikovsky’s Swan Lake, like a clap of thunder, filled the room. Unfamiliar, and yet, she felt she ought to know it, as if she had heard it a thousand times before. Every time she willed her body to move, her feet would slide into a ballet position like it was the most natural thing in the world. What her mind had forgotten, her body remembered. Pirouettes, jetés, and pliés came to her in time to Tchaikovsky’s eternal creation, each as perfect as a summer rain.

Today was a special day. The nurses seemed excited for her. She felt she should be excited, too. Staring in the mirror, right into the stranger’s eyes, she forced her face into a smile and widened her eyes, but instead of happy she looked scared. She was exhausted, as if she had lived a thousand lifetimes, none of which she could remember. Splashing her face with cold water, she brushed her hair and tied it in a high ponytail. Reaching for her bag, she applied some makeup. Black for her eyelashes, pink for her cheeks, red for her lips. The last thing she wanted was to look like she was part of this grey hospital room.

The London sky outside wasn’t grey but a vivid purple. She watched the last traces of sunlight disappear, and then, out of nowhere, the rain came. It battered the lone oak tree outside, and the leaves thrashed in the wind. Over the music she could hear their rustle. This sky, this oak tree, the room she was in, the cafeteria down the hall – these were the boundaries of her world. Beyond them, she knew nothing.

The music stopped and she turned sharply away from the window. She could sense his gaze. The man standing in the doorway was tall, and she felt dwarfed by him. They stared at each other in silence for a few seconds too long – Claire, her cheeks flush with rouge, eyes filled with fear, and her husband, impeccably dressed, unsmiling, unfamiliar.

‘Hi, Claire.’ The man took a few steps in her direction.

‘Hi, Paul.’ In two weeks she had seen him twice. Now he had finally come to take her home.

‘Feeling better today?’

She didn’t know how to answer his question. Better than two weeks ago? Yes. But better in general? She couldn’t remember what that felt like. ‘I still get headaches. But my back is almost healed.’ She peered into his face. There were wrinkles around his eyes and dark stubble on his chin. She didn’t have it in her heart to tell him he was a stranger to her. But he was looking at her as if she was a stranger, too. His eyes remained cold.

‘Do you have everything?’ he asked.

‘I just need to say goodbye. Wait here for me? I won’t be long.’

She made her way down a busy corridor, navigating gurneys, trolleys and people. She had made this trip many times before, could probably do it with her eyes closed – a left turn, twenty uncertain paces, another left, down two flights of stairs and a right. The door she wanted was hidden behind a pillar, tucked away from prying eyes. You could easily walk past and not even know it was there. Today it was wide open, as if inviting her in.

It was quiet in the room, no music playing, no television murmuring in the background, no eager visitors with their chatter and flowers. Only the heartbeat of the machines, like clocks counting down the seconds, and the ventilator puffing, struggling, breathing in and out. If nurses or doctors spoke in here, they did so in hushed voices, as if they were afraid of disturbing the man on the bed. Which was ironic because all they wanted was for him to wake up.

Outside the window was the hospital car park, a noisy anthill of activity, with ambulances screeching and cars vying for spaces. The rumble of engines was a muffled soundtrack to the man’s artificial existence. She felt grateful for the oak tree outside her room, for the peace and quiet. She would have hated having nothing but cars to look at. But the man didn’t care. He was asleep.

Sitting on the edge of the bed, Claire took his hand. After two weeks, this gesture had become a habit. Day after miserable day she would do it on autopilot, looking into the man’s face, studying his lifeless features. Today she could swear his eyelids were moving. She wanted to ask the doctor if it meant anything. Fluttering eyelids – was it a sign? Was he about to wake up? Or was it her imagination showing her what she wanted to see?

‘Your father, is it?’ A nurse crept up behind her silently, like a cat. She looked a little like a cat too, scruffy and ginger, her eyes cagey. She paused next to the man’s bed, removed the chart from its folder and checked the monitors. ‘You look just like him.’

The man’s skin was grey today, more so than usual. His face was gaunt, his body a skeleton on the white sheet.

‘Yes,’ said Claire. ‘I’m waiting for him to wake up, so he can tell me about my life.’

If the nurse was surprised, she didn’t show it. ‘Are you a patient here?’

Claire didn’t answer but turned away from the nurse and towards her father. The woman’s mouth opened as if to repeat her question, but at the last moment she seemed to change her mind. Her eyes darted over Claire’s face as she made a few notes on the chart and placed it back. ‘I hope he pulls through,’ she said finally. ‘I’ll pray for him. And for you.’

She was already out the door when Claire called out, ‘Can he hear me? If I talk to him, can he hear?’

The ginger head reappeared in the doorway. ‘They do believe so. I mean, after all the research they’ve done. Speak to him, tell him you love him. It will help.’ The nurse nodded as she spoke, as if for emphasis. Her eyes filled with compassion.

Claire squeezed the man’s fingers. Ever so slightly she shook him, pushed his shoulder with her tiny fist, willing him to open his eyes. His hand felt cold in hers, a dead weight pulling down. She brought it to her face and saw her tears fall on the calluses of his palm. These hands held me when I was a child, she thought. These lips, now motionless, read bedtime stories and kissed me goodnight. How could she have forgotten all that? It didn’t seem possible. Memories like that were part of one’s DNA, only gone when life itself was gone. She leant over, pressing her lips to his forehead. ‘Wake up, Dad,’ she whispered. ‘I need you.’

She had spent the last two weeks feeling guilty. Guilty that she was awake, while her dad was unconscious. That she could walk, look out the window, enjoy the pale sunlight and the meagre hospital food. And now she felt guilty she was leaving this place, returning to what once had been her normal existence, while he was stuck in this bed, not yet dead, but not quite alive either.

On the way back she walked slowly, delaying the inevitable, not ready to leave the familiar for the unknown.

Paul was waiting in her room. ‘Time to go,’ he said and his lips stretched into a smile. Even to her confused, drug-addled mind, it looked forced. Glancing away, she nodded quickly and reached for her bag. Her whole life, all two weeks of it, packed into a small travel case. Paul walked out without touching her. As she waited for him to talk to the doctors and sign the paperwork, she felt sweat drops on her forehead. Her throat was dry.

The nurses came to say goodbye. As she hugged them, she cried like she was parting with the only family she had.

In the car Paul was silent. The only sound was the swish-swish-swish of windscreen wipers as they sped through the rain. There was so much she wanted to know. How did we meet? How long have we been married? Do we make each other laugh? Are we happy? She didn’t ask any of those questions. Instead, she said, ‘Where were we going?’

‘What?’ Paul startled as if she woke him from a dream.

‘Dad and I – where were we going on the day of the accident?’

‘I don’t know. I wasn’t there.’

Shadows loomed outside the car window – trees, houses, lampposts. Claire watched them whiz past at forty miles an hour. She could make out manicured lawns, flowers and driveways. Some windows were dark, others brightly lit. She imagined a different life inside each one. Perhaps a married couple sitting down to dinner before retiring to bed to read and fall asleep in each other’s arms. Or a grandfather listening to his grandson play the piano.

‘Do I have any other family?’ she asked as they turned onto a motorway. There were no more houses, no more lights, only dark skies and even darker trees.

‘There’s your mother.’

‘She never visited me at the hospital. Why is that?’

For a moment he looked confused. ‘I was surprised when I didn’t see her there. I expected her to be by your side at a time like this.’

I have a mother, she thought. Squeezing her eyes shut, she searched for a recollection. If she reached deep enough, if she focused hard enough, would she be able to see her mother’s face? That wasn’t something one could easily forget. Not even someone like her. Swallowing the sudden lump in her throat, she dug her nails into the soft skin at the back of her wrist. She wondered what her mother was like. Had she taken her to ballet classes when she was little? Had she stayed up late baking cupcakes for her birthdays? Did she look just like her, only slightly older?

‘Any brothers or sisters?’

‘You’re an only child.’

Before she could ask another question, the car screeched to a stop outside a two-storey house. In the headlights she could see a sprawling lawn and a white staircase curving up to a set of French doors. It was not a house; it was a mansion. As she gaped at it, wide-eyed, Paul opened her car door. She emerged, slipping on wet gravel. He caught her mid-fall but almost immediately let go.

Bright lights snapped on suddenly along the front of the house, startling her. ‘Motion sensors,’ explained Paul. He carried her suitcase up the stairs and there was nothing left for her to do but follow into the life she knew nothing about. The rain lashed the side of her face as she walked, and the droplets ran down her body, filling her shoes with water.

When they reached the front door, she heard whimpering. Surprised, she glanced at Paul, but he was busy fumbling for the keys. Finally, he unlocked the door, letting her in. As soon as she stepped over the threshold, she was under attack. Something enormous crashed into her, making her cry out in terror. She lost her footing and fell, at the last moment grasping a wall. A large beast wrestled her to the ground, its heavy breathing in her ear. Barking excitedly, it slathered her with a long, wet tongue. Catching her breath, she ran her fingers through the fur. When Paul turned on the lights, she saw the beast was only a dog. It was a large Labrador, with a long tail and droopy ears.

‘Down, Molokai,’ said Paul. Instantly the dog leapt off but continued jumping on the spot, its yellow tail dancing.

‘Molokai?’ The word stirred something in her, a distant memory that wouldn’t rise to the surface. It wasn’t a word she recognised, and yet it sounded familiar, as if a dozen threads of her life were intertwined in those three syllables. In frustration she looked at the dog and the dog looked back, its mouth open in a smile.

‘Molokai is an island in Hawaii,’ explained Paul. ‘That’s where we honeymooned.’

‘Oh. How old is she?’

‘He is five.’

Carefully she rubbed Molokai behind his ear. Something told her dogs loved that. This one certainly did – as soon as Paul’s back was turned, he jumped all over her again. ‘That’s a nice welcome,’ she muttered, not sure what to do next.

‘Yes, he’s very friendly. Sometimes too friendly. If ever there are burglars in the house, he’ll probably lick them to death. He loves you the most.’

Looking into the dog’s dark eyes, Claire suspected the feeling was mutual. For a moment she felt a little less lonely.

‘Come in,’ said Paul. ‘No point standing in the doorway like an unwanted guest.’

But that’s how I feel, she wanted to tell him as she walked into the living room. Like an unwanted guest who had confused date and time, ending up in the wrong place when she was least expected. Luckily, Molokai was by her side. Her hand on his neck, she stared at the high ceiling and the marble floors. In the far corner of the room she spotted a white cat. It glanced at Claire for a few seconds and ran off as fast as it could, hiding behind a curtain. Looking up, she noticed an enormous crystal chandelier, all baubles and fake candles. It was the ugliest thing she had ever seen.

‘Your pride and joy,’ said Paul. ‘You bought it in Italy.’

Choosing to ignore this information, Claire perched on the edge of a sofa. Paul watched her for a few seconds. ‘No need to look so overwhelmed. This is your home. Make yourself comfortable. Hungry? There are sandwiches in the fridge.’

‘You made me sandwiches?’ She was touched.

‘Our housekeeper did.’

‘We have a housekeeper?’ Why did she find that so surprising? The housekeeper seemed to go hand in hand with the marble floors and the sprawling staircase. ‘How can we afford such a big house?’

‘Your mother bought it for us.’

‘My mother is rich?’

‘Old family money,’ he explained.

Although food was the last thing on her mind, Claire sat down at the dining table with Molokai at her feet. She could feel his cold nose on the bare skin of her leg. Paul didn’t eat, nor did he look at her, staring at the newspaper instead. She could tell he wasn’t reading. His eyes remained steady, far away. Like jigsaw puzzle pieces that didn’t quite fit they sat in awkward silence on opposite sides of the table.

Soon there was nothing left of the sandwiches but a few pickles. She didn’t like the salty taste on her tongue.

‘You don’t want those? They’re your favourite,’ said Paul. ‘You always ask for extra pickles on everything.’

Uncertainly she poked a pickle with her fork. ‘They taste like seawater.’

‘That explains why you like them. You love the sea.’ There was a fleeting smile on Paul’s face and this time Claire could swear it was genuine. ‘You look exhausted,’ he added. ‘Why don’t I show you to your room?’

Gratefully, she followed him up the stairs to a spacious room decorated in beige. It was tidy but for a worn-out silk robe on an armchair. The king-size bed looked so enticing, Claire was tempted to fall in and lose herself under the covers, wet clothes and all.

The room was quiet – no traffic, no voices and only a muffled whisper of leaves reached her through the open terrace doors. She peeked through the curtains but couldn’t see beyond the darkness.

‘My room is across the corridor. If you need anything, anything at all, just knock.’ He kissed her good night. His lips on her cheek were arctic. He might as well have been kissing a distant aunt.

‘Wait,’ she said. He paused in the doorway. She cleared her throat. ‘My mother. What’s her name?’

‘Angela. Angela Wright.’

‘And my father?’

‘Your father’s name is Tony.’

And with that he was gone, shutting the door and taking Molokai with him. Claire barely had the energy to change into her nightdress, but despite her exhaustion, sleep wouldn’t come. She closed her eyes under her beige covers and concentrated on the sound of rain hitting the windowsill, repeating her parents’ names quietly to herself and hoping to remember something, anything, about them. The events of the day played over and over in her mind until she heard the phone ring, and then Paul’s voice. A minute later there was a knock on her bedroom door.

‘Someone just called from the hospital,’ Paul said. ‘Your father is awake.’

Chapter 2 (#u960d4df5-c19b-5e90-ab30-9b0beadc82b8)

The human mind … what a fragile thing it was. One minute your life had meaning. You had a past, a present and a future that was anticipated and planned for. You went to work, saved money, paid into your pension. You got married, travelled the world, fell in love, had babies, pizza every Saturday and takeaway Chinese every Friday night. And then, just like that, without any warning or indication, your mind could turn its back on you, leaving you in a void. Knowing who you are, where you are in life, all gone like an early morning fog. Without that knowledge, what was left?

One day at the hospital, Claire had overheard the nurses chatting over their cups of coffee. If you could be anyone else for one day, who would you be, they mused as they took careful sips of their flat whites. Wouldn’t it be wonderful, to live someone else’s life for a day, to be them, to feel like them? A movie star, perhaps, or a famous singer. A cattle drover in Australia. To live a life as far removed from yours as possible, wouldn’t that be something? That was how Claire felt – like she was living someone else’s life. But it wasn’t wonderful. She felt like she was drowning and no one was there to save her.

With a start she woke up and for a moment didn’t know where or who she was. The strange room, the luxurious bed, the expensive furniture – none of it looked familiar. And then she remembered – she was home.

Sitting up, she rubbed her eyes. Spotting a silk robe draped casually over an armchair, she threw it on and stepped out of bed. She crossed the room in small, tentative steps and pulled the curtains open. The rain of the night before was gone. All she could see was the blue of the skies and the green of the trees. She wished she was outside, walking in the park, window shopping or having a coffee in one of the many cafés lining the nearby streets. She didn’t want to be in the alien house that was supposed to feel like home but didn’t.

Glancing at the clock, she noticed it was only nine in the morning. Another three hours until Paul drove her to the hospital to meet her father. How was she going to fill the time? A part of her wanted to fast-forward these three hours, while another part of her, a shy and retreating part, wanted to hide. It’ll be okay, she told herself. I might not remember him but he is my father. He loves me. We love each other. Last night when the hospital had called, she’d wanted to rush to her father’s side right away. But she had to wait. There were no visiting hours in the middle of the night.

She could hear a soft whimpering outside. Molokai, she thought. And she was correct – the dog leapt into her arms, whining happily, as soon as she opened the bedroom door. She ran her hand through his fur and was rewarded by a thousand kisses. ‘Look at you, you’re all muddy. Have you been out for a walk? No, not on the bed.’

Miraculously, the dog obeyed. Accompanied by Molokai, she set out to explore. There was an en-suite bathroom in her bedroom. She marvelled at the size of it – it was twice as big as her hospital room. All marble and granite, it was decorated in the same colour scheme as the bedroom. Absentmindedly stroking a cotton towel, she wondered whether she had picked out this colour.

There were two bathroom sinks next to each other. Did she once share this room with her husband? For a few seconds, as she peered at her reflection in a hexagonal mirror above the sinks, she thought about her marriage. There was so much she didn’t know.

The freestanding bathtub in the middle of the room – for it was a room in its own right – looked so tempting, she wanted to climb straight in and feel the water on her body. But for now, the shower would do. She undressed behind a waterfall of crystal-like beads and eagerly turned the shower taps. For ten minutes she stood under cascades of warm water, while Molokai patiently waited outside the glass door.

Afterwards, while the dog bounced around like an overexcited toddler, she sat in front of a tall mirror in her bedroom. One after another she opened five bottles of perfume, spraying a little bit of each on her wrists and neck and regretting it instantly. The smell was overwhelming and made her gag.

The house was quiet. No cars driving past, no voices from the park. She didn’t know where Paul was. His car wasn’t in the driveway. Tying the cord of her robe together, she left the room. There were three other doors on this floor and, holding her breath, she opened each one. Two of the rooms contained no personal touches and seemed unoccupied. The last of the three clearly belonged to Paul. It was untidy, with clothes all over the floor. The room looked like Paul – masculine brown wood and dark furniture. She stood in the doorway, feeling like a child locked in an unfamiliar house with no way out. It was unsettling and more than a little scary.

She didn’t want to snoop on Paul. It felt too much like encroaching on the private life of a stranger. She shut the door to his bedroom and walked down the marble staircase. Although she remembered the majestic living room from the night before, it still took her breath away. Suddenly she felt confused, like she was lost in the woods and didn’t know what direction to take. Everything in this house seemed alien and she couldn’t believe this was where she lived. Shivering, she walked into the kitchen. Just like she expected, it was spacious, with what she assumed must be all the latest appliances. In the fridge, she found a dozen sandwiches similar to the ones she’d had the night before. Reaching for a ham sandwich, she ate it as quickly as she could and then looked through cupboards. In amazement she stared at fruit she didn’t recognise, delicate crystal glasses, porcelain plates and every flavour of tea imaginable. She found some cat food and refilled the cat’s bowl, wondering whether it was hiding somewhere, too nervous to come out.

Her strength restored, she explored further, walking from the kitchen to the dining room to another guest room. They had a sauna, a swimming pool and an air hockey table in the basement. Finally, she spotted an old-fashioned piano in the drawing room. Tired now, she slid into a chair in front of it and ran her fingers over the keys. The most beautiful sounds escaped from under her fingertips and she paused for a moment, lifting her hands and staring at them as if she had never seen them before. Then she resumed playing. It wasn’t Swan Lake or any of the music she’d heard in the hospital but a melody she didn’t recognise.

‘What do you think, Molokai? Did you know I could play the piano?’ she asked the dog, who wagged his long tail in response.

As Claire contemplated this newly discovered ability, somewhere inside the house a phone rang. She stopped playing and stood up, nervously clutching her hands to her chest. What was she to do? Did she answer the phone? Or let it go to voicemail? Slightly unsteady on her feet, she walked towards the sound and watched the phone like it was an explosive device about to go off. Eventually it stopped ringing and Paul’s voice could be heard asking to leave a message. ‘Claire, it’s me, Gaby. Call me back as soon as you get this. I need to see you.’

When the person on the other end hung up, Claire returned upstairs. She felt safer there. There were no phones she could see, no unfathomable voices coming through the speakers.

Back in her bedroom, she opened the wardrobe. Walking inside – yes, the wardrobe was big enough to walk inside it – she examined rows of designer clothes, shoes and underwear. It was like being in a department store. She went through every drawer, rummaged through dresses and looked behind shoe racks. Who needed what seemed like a hundred pairs of shoes? And all these clothes … most of them looked like they had never been worn.

Suddenly, Molokai leapt off the bed and growled. Seconds later she heard the doorbell. Unsure of what to do, she froze with a shoe in her hand. Molokai ran through the door and soon his excited barking could be heard from downstairs. She followed on legs that seemed to have turned to jelly.

From behind the front door, she heard a woman’s voice. ‘Hello, anyone there?’

‘One second,’ said Claire, throwing a quick glance in the mirror and wondering whether she was dressed appropriately for a visitor. Through a gap in the curtains she could see a delivery truck parked on the opposite side of the road. Concluding it was just a courier and breathing out in relief, she fiddled with the lock. It was complex and she couldn’t open it. ‘I’m sorry, I don’t have the keys for this door,’ she called out. ‘Are you delivering something? Can you leave it outside, please?’

‘Claire, it’s me, Gaby,’ she heard in reply. ‘Can I come in?’

Claire recognised the voice from the answer machine. To her surprise, a key turned and the door opened.

A stunning brunette was standing in the doorway. She looked like she had just walked off a movie set. There was a hint of something foreign about her – the Mediterranean tinge to her skin, the deep caramel to her eyes. A leather skirt hugged her slim hips. There was a bouquet of flowers in her hands.

‘Oh my God, look at you!’ she exclaimed, drawing Claire into a hug and almost crushing the flowers. Claire struggled but only for a second – resistance seemed pointless. ‘It’s so good to see you! You have no idea how worried we were.’

Claire extricated herself from the embrace, mumbling, ‘It’s good to see you, too.’ She didn’t know what else to say. Unlike Claire, Molokai seemed to know exactly who the woman was. A chewed dog toy – a plastic duck with its head missing – miraculously appeared in his mouth and he presented it to the visitor. His tail was wagging.

The brunette ignored the decapitated duck but gave Molokai a distracted stroke. ‘These are for you,’ she said. Her eyes twinkled as she shoved the flowers into Claire’s hands. ‘They’re orchids.’

Intimidated by the woman and the flowers, Claire wished she had brushed her hair instead of dousing herself in all that perfume. I must smell like a bouquet of flowers myself, she thought. But the woman didn’t seem to mind.

‘You don’t remember me, do you?’ The brunette shook her head with disapproval, as if talking to a child who was struggling with her homework. ‘It’s me, Gaby. Your best friend.’

As Claire stood in the doorway gawking, Gaby made her way into the dining room. She seemed to know her way around Claire’s house much better than Claire did.

‘You have the key to the house?’ Claire asked to break the silence.

‘Of course I do. You and I are like sisters. I went to school with Paul. That’s how we met.’

While Claire arranged the flowers in a vase she had found, Gaby walked into the kitchen and poured two glasses of red wine. A sudden thought occurred to Claire. Didn’t a person tell their best friends everything? If that was the case, Gaby would have all the answers she was so desperately searching for.

Gaby handed Claire her wine. Taking a careful sip, Claire put her glass down.

‘You don’t like it?’ asked Gaby. ‘It’s your favourite.’

Claire found it hard to believe. Her taste buds seemed unacquainted with the sharpness of the wine. She was desperate for a sip of water to get rid of the bitter taste but didn’t want Gaby to think less of her. She felt a little intimidated by her old self, who would have enjoyed the wine and known what to say to this beautiful stranger.

In the first week at the hospital, many people dropped in to see her, faces and conversations she could hardly remember now, so confused and drugged up she had been back then. Little by little, however, the stream of visitors dwindled, before finally disappearing altogether. There was only so much one-sided conversation even a good friend could take. Only so much small talk with someone who did nothing but sit in her bed, staring into space, not knowing what to say, not knowing who she was.

What if she couldn’t live up to the person she had once been? And how could she, if she remembered nothing about her? ‘I’m not sure I’m allowed wine. I’m on all sorts of medication.’ She pushed the glass away.

‘I’m sorry I haven’t been to see you in hospital. I’ve been away for work. My first time in Japan, what a fascinating place …’ Gaby spoke fast, and her cheeks looked flushed. ‘Yesterday we went to that amazing Thai place you love. What is it called?’ She looked at Claire expectantly. ‘Oh yes. Thai Basil. Tina, Ruth and Betty were there. We were talking about you. Let me tell you, I was absolutely beside myself when I heard. I wanted to cut my trip short, of course, but there was still so much to do. And I thought, you’re already in hospital. Paul and your mum are there. There’s nothing I can do.’

‘My mum wasn’t there.’

Gaby’s eyebrows shot up in surprise but she didn’t comment. Instead, she told Claire all about Nijo Castle (‘I’ve never seen anything like it!) and Mount Fuji (‘We went on the most amazing boat.’ A boat on the mountain? Claire wanted to know. But apparently there was the most amazing lake there, too.). Finally, Gaby lowered her voice and said, ‘I’m sorry about your dad.’

‘My dad’s awake. He’s going to be okay. Paul is taking me to the hospital to see him later.’ Impatiently she looked at the clock. Another two hours to go. ‘Have you met him? What is he like?’

‘Paul?’

‘My dad.’

‘I’ve met him a few times. I thought he was quite the flirt.’

‘He was?’ asked Claire, wondering if Gaby was making things up, embellishing to make her stories more exciting. She seemed just the type to do something like that.

‘All completely innocent, of course.’

‘Of course.’

‘He seemed besotted with your mother. I remember wondering if I would ever meet anyone who loved me that much. The guys I meet …’ She shook her head. ‘Never mind. So, are you telling me you don’t remember—’ Gaby leaned forward and lowered her voice to a whisper ‘—anything? Not even your birthday party last month? Come on, no one could forget that night.’

Dejectedly Claire shook her head. ‘No,’ she said quietly. ‘No, I don’t.’

‘Wow,’ Gaby whispered, staring at Claire like an entomologist studying a particularly rare beetle. ‘What does it feel like?’

‘It just feels …’ Claire thought about it. ‘It feels blank.’

‘Sometimes I wish I could forget my life.’ Gaby seemed lost in thought for a moment, then shrugged. ‘Enough about me. You have to promise you are looking after yourself. It must be so terrible. I can’t even imagine.’

Now it was Claire’s turn to shrug. ‘Tell me something about me. A story to jog my memory.’

‘How about some photographs? Let me have your phone.’ Gaby grabbed Claire’s phone and pressed a few buttons. ‘Here is your Facebook page. You must have thousands of photos up there.’

She scrolled through pictures, telling Claire funny anecdotes about all the people in them. Claire had spent hours in the hospital staring at the photos. But it was one thing looking at faces of strangers and quite another listening to Gaby bringing these strangers to live. ‘This is Tiffany,’ Gaby was saying. ‘You went to ballet school together.’ Tiffany was wearing a tight-fitting business suit, as if she had just stepped out of a job interview, but her posture, her body, the way she carried herself betrayed a dancer.

‘She’s beautiful.’

‘You call her the cow behind her back. And sometimes even to her face.’ Another photo popped up. ‘And this is Kevin. He tried to kiss you at your birthday last year. And when you turned him down, he kissed three other people just to prove it didn’t mean anything.’

‘Three other women?’

‘Not all of them women.’ There must have been shock on her face because Gaby laughed and added, ‘Dancers, what can I say?’ She had a good laugh, loud and infectious. It lit up her face and made her eyes twinkle. Suddenly Claire felt like a ray of light had illuminated her otherwise dark universe. She had a friend. She was no longer alone.

When a photo of a blonde woman in her fifties appeared, Claire exclaimed, ‘That’s Mum!’

‘You remember?’

‘I just knew.’ But she didn’t know how she knew. She pondered it for a moment, wondering if it was a memory or just intuition. Her mother was looking straight at Claire from the screen, her light hair pulled away from her face, her arms around the man Claire had spent hours watching at the hospital.

‘This is her with your dad at a barbecue a few years ago.’

Angela looked tiny next to Tony. She seemed lost in his embrace, and he hovered over her, holding her close as if he wanted the whole world to know she was his.

Claire couldn’t stop looking at her mother. She was so beautiful, her eyes so kind, her features delicate. Suddenly she found herself unable to speak or smile at Gaby or think of anything else. Tears filled her eyes and she didn’t know why. To change the subject, she asked, ‘What about me and Paul? Are we happy?’

Gaby seemed thrown off balance by her question. She emptied half her wine glass before she replied, ‘If you need to ask, the answer is probably no.’

‘We’re not happy?’ As if Paul’s cold smile and distant eyes hadn’t already alerted Claire that something was wrong.

‘Let’s just say, you have some issues.’

‘What kind of issues?’

‘It’s not my place to tell you.’

‘If you won’t tell me, no one else will.’

Gaby stepped from foot to foot, as if she wanted to be anywhere but here, having this conversation with Claire. ‘Maybe that’s for the best. I have to run, anyway. I’m always late, to everything. How do I look?’

Claire assured Gaby she looked fine, better than fine. But what she wanted to do instead was ask her friend not to go because for an hour in her grim morning she had laughter and joy. Gaby almost made her forget that she had forgotten her whole life. And for a brief moment with Gaby she felt hopeful. ‘Will you come back to see me?’

‘Of course.’

When the door closed behind her friend, Claire went up to her room. Climbing into bed and hugging Molokai, she reached for her mobile phone. It was as if her fingers once again had a life of their own. They knew exactly what numbers to press to unlock the phone. She looked through every photo until she came across the one she was looking for. Stroking her mother’s beautiful face with her fingertips, she struggled not to cry. Her mother was smiling at her as if telling her everything was going to be okay.

Claire loaded her contact list, hoping to find her mother’s number. And there it was, listed under Angela, ten digits that just a few short weeks ago she had probably known by heart. She stared at the number, blinking rapidly, reading it out loud, rolling every syllable off her tongue, hoping it would trigger a shadow of recollection, a glimmer of hazy remembrance.

Her whole body trembling, she pressed the call button. The phone rang and rang.

* * *

As Claire followed her husband across the hospital car park and through the front entrance, she realised she was petrified of the real world. She had spent a morning in that world and felt out of place, an outsider looking in. But at the hospital she was at home. As if this was where she belonged. Others had childhood memories, heartwarming and sweet, sometimes bitter, but always there to remind them that once there had been a different life, a different journey. They had memories of weddings, anniversaries and holidays by the sea. All Claire had was this place, with its closet-sized rooms, grim corridors and overworked staff. Nothing had changed here since the day before. It was still grey, shabby and depressing. So why did it feel so infinitely comforting to be walking down the familiar corridor?

No one expected her to be herself here, she realised. No one expected her to be anything. She could just be. Wake up in the morning, eat her meals, wrinkling her face in disgust, have her meds. She didn’t have to make decisions because they were made for her, by the doctors and the nurses. And that was what she missed when she stayed inside her beautiful mansion wearing her designer clothes, living someone else’s dream life but feeling like a prisoner.

She wished she could go back to her old room and remain like before, confined within her small world where nothing threatened her peace. She wished she could sit by the window, watching the oak tree outside, longing for a different life but not forced to go out there and live it. Could she stay with her father instead of going back to the alien house with a husband who treated her like a stranger? Of course, her father was a stranger to her, too. But she’d spent so long watching him, studying his face for clues, memorising his every feature, she felt she could open her mouth and recount every little detail of his life. His life was on the tip of her tongue, at the edge of her subconscious.

On the drive to the hospital, she had asked Paul what her father was like. ‘He’s not the friendliest man in the world. I don’t think he likes me much,’ he’d said. ‘But he’s your father. He loves you.’ His answer wasn’t what she wanted to hear, and it didn’t match the inner picture of her dad she had painstakingly created over long hours of watching and thinking, so she put Paul’s words to the back of her mind, to that place where her other memories were hiding.

But now, as she was about to face the man who had known her since the day she was born, the man she remembered nothing about other than the shape of his nose and the curve of his mouth, she wondered why her husband would say something like that. Didn’t Paul and her dad spend time together, discussing football and weather over a pint of beer? Were there no family barbecues, Christmases and birthdays where sausages sizzled on the grill and intoxicated confidences were exchanged late into the night? Or maybe Paul not getting along with Tony was completely natural. Fathers didn’t always like to share their little girls with their husbands. And husbands were often intimidated by their fathers-in-law.

As she turned the handle and pushed the door to her father’s room, she tried to calm her beating heart. She didn’t want the nurses at the reception area to hear it but how could they not? The thumping in her chest was deafening. It was like church bells ringing in her ears.

Her mind was filled with snippets of imaginary conversations with her father. Would she know what to say? Would he know what to say? Would they be able to pick up where they had left off, even though she couldn’t remember anything? Her relationship with her father, was it instinctive? Was it in her blood, in his blood? Did it transcend crashing cars and lost memories? She didn’t want small talk with her father. She wanted him to tell her who she was.

The door wouldn’t give in. She pushed and pushed.

‘Here, let me help,’ said Paul, pulling the door lightly, making her feel silly and a little light-headed. ‘Good luck. I’ll wait here for you.’

‘You aren’t coming in?’

‘I’ll give you two some privacy. In the meantime, I’ll speak to his doctor.’

A part of Claire was relieved she was about to face her father alone. She felt a little less nervous meeting him unobserved. She didn’t want their relationship to be judged by an outsider, even if that outsider was her husband. She wanted to be alone with her dad, to find her own way back to him, to let him find his own way back to her.

On tiptoes she walked in, sliding her feet as if she were on stage, performing a pas de deux she hadn’t yet mastered. She paused in the doorway, watching the man on the bed just like she had so many times over the past two weeks. Only this time everything was different. This time he was awake.

She wondered if she would always remember this moment. Everything in her life was about to change. Or, rather, a little bit of her old life was about to come back.

From where she stood she couldn’t quite tell whether he was sleeping. Not a part of him moved and his breathing was calm. Without the ventilator inhaling life into her father’s lungs, the room seemed quiet and lifeless. Tony was tall and broad-shouldered, a bear of a man, but he appeared frail, propped up on his pillows and leaning to one side. He didn’t seem to hear her. She took a few steps forward.

He looked like an old man laid out on a white sheet, his stubble making his face look grey, his eyelids trembling like butterfly’s wings. Her heart pricked with pity.

‘Dad,’ she called out softly. She sounded high pitched and unsure of herself. Was she being presumptuous, calling him that? It didn’t feel unnatural. Quite the opposite, the word slipped out easily, on reflex. Yes, she didn’t know anything about him, but he wasn’t a stranger. He was blood. Shaking a little, her legs unresponsive as if they were filled with cotton wool, she crossed the room and perched on the edge of his bed.

He didn’t stir. His eyes were closed. Just like all those other endless days in the hospital, she studied him in silence, trying to memorise the features that she had known since birth but that were completely unfamiliar to her. A straight nose, bushy eyebrows, wide cheekbones, a mop of grey hair that needed a comb.

Suddenly, unlike all those other times she had sat here, he moved his arms in his sleep. Claire got up, her cheeks burning. She needed to cool down, feel cold water on her face. Slowly and uncertainly, as if she was learning how to walk, she made her way to the bathroom attached to his hospital room and leaned on the sink, watching her face in the mirror.

‘Good afternoon. How are we feeling today?’ came a loud voice. Claire peeked through the creak in the door and saw a doctor leaning over Tony. He wore a white coat over his business suit. There was a cold smile on his face, a smile of someone who was paid to care but didn’t.

‘Never better,’ croaked Tony. He sounded hoarse, like he was recovering from a bad cold.

‘That’s good to hear. If it’s alright with you, I am going to ask you a few questions, just to see if your memory has been affected. Take your time to answer. There’s no rush. And don’t worry if you can’t remember something. It’s completely normal in your condition. Can we start with your name?’

‘Wright. Tony Wright.’

‘Very good, Tony.’ A machine gun fire of questions followed – what was his address, his date of birth, his occupation, his marital status, how long had he lived at his address, how long had he held his driver’s license, did he have any children, any pets, what did he enjoy doing. Her father responded in a lifeless voice but without any hesitation.

And finally, ‘Do you know what happened on the day of the accident?’

Tony spoke through gritted teeth. ‘I was in the car. That’s the last thing I remember.’

‘I expect the police will want to speak to you later today. They’ve been waiting for you to wake up.’

From the bathroom, Claire heard the bed creak. ‘Why?’ asked Tony.

‘There’s been a serious accident. Two people got hurt.’

‘Two people? I crashed into the motorway divider. No one else was involved.’

‘Your daughter Claire was with you.’

A few seconds ticked by before Tony answered. ‘That’s not true. I was alone in the car.’

Claire wished she could see her father’s face but from where she was hiding, it was impossible. Was his memory affected, just like hers? Was he confused, just like her?

‘Don’t worry, the police are treating it as an accident. I will tell them you don’t remember. You’ve been through a lot and—’

‘I remember perfectly well, Doctor. There was no one in the car with me.’ His voice rose as if he was angry. At the doctor? At the never-ending questions? Claire felt sorry for her father. What he needed was a rest, not an interrogation.

As if he could read her mind through the bathroom door, the doctor said, ‘I’m sorry for disturbing you. Please try and get some rest.’

‘Wait, Doctor. I can’t feel my legs. Why can’t I feel my legs?’ Tony’s voice quivered.

Five seconds passed before the doctor replied. Claire knew how long it took because her gaze followed the silver-plated hand of the clock on the wall. In that time the doctor shuffled uncomfortably, averted his gaze, coughed. He didn’t meet Tony’s eyes when he said, ‘Your spine was severely damaged in the accident. We did all we could but …’

‘I can’t walk?’

‘I’m very sorry. With time and extensive physiotherapy there’s a chance, a small chance—’

‘Is there anything you can do? Operate, do something, fix it.’

‘We tried our best but the damage was quite severe, I’m afraid.’ The doctor was moving away from Tony. Imperceptibly, little by little, he was shifting towards the door. ‘There was nothing we could do.’

‘Nothing you could do?’ Tony sounded close to tears. Claire felt close to tears herself.

‘I’m very sorry, sir.’

The doctor left without another word. Claire glanced at the door, at her father’s back, at his heaving shoulders. She wondered if she could slip out without him noticing. Although she wanted to comfort him, to take him in her arms and make it all go away, she knew it was impossible. And she didn’t want to meet him for the first time when he was sobbing uncontrollably on his bed and all she felt was helpless and lost.

Soon his crying subsided and his breathing became regular. Claire tiptoed past him to the door, turning the handle softly. She was about to walk out when she heard his voice. ‘Hello, Teddy Bear.’

His voice was soft like a caress. She turned around. Tony had pulled himself up in bed and was watching her intently. With his mop of grey hair and bushy eyebrows, his crooked nose, like an eagle’s beak, and his narrow cheekbones, he looked moody, as if permanently disappointed with life – until he smiled. His smile transformed his face and made him appear attractive and kind. It made Claire’s heart feel lighter.

‘Hi, Dad. How are you feeling?’ She stepped from foot to foot, not sure what to do with her hands, then closed the door and walked back to his bed.

‘I’ve been better.’ He laughed like it was a joke only he could understand. ‘Come over here and give your old man a hug.’

She leaned closer and he scooped her up in his arms, effortlessly pulling her to him. ‘Be careful,’ she said. ‘I’m heavy.’

‘Oh yes, as heavy as a feather.’

As she relaxed into his arms, she thought he was surprisingly strong for someone who was bedridden and unable to move. He smelt of hand sanitiser and soap, hospital smells she found familiar and reassuring. His heartbeat was a comfort against her chest. For a few seconds he didn’t let go. And she didn’t want him to.

‘Ask me again,’ he said, finally releasing her.

‘Ask you what?’

‘How I’m feeling.’

‘How are you feeling?’ she repeated like an obedient daughter.

‘After a hug like that? Like a million dollars!’ He winked and patted the bed next to him, urging her to come closer. His fingers wrapped around hers, squeezing tightly. ‘So what did I miss?’ he asked, smiling brightly. He had a good smile. It was kind. It inspired trust. Paul had got it all wrong, she thought. Her father wasn’t unfriendly. He was warm and welcoming.

‘I wouldn’t know. After the accident, I lost my memory. I was in the hospital with you for a long time.’

‘What accident?’

‘Our accident.’

‘I know they keep saying you were with me. But they are wrong. It was just me in the car that day.’

‘But if I wasn’t with you …’ She hesitated. ‘What happened to me?’

‘I don’t know, darling. Did you say you lost your memory?’ His eyes appraised her, taking her in. She was glad she had made an effort with her appearance. Her hair was tied back into a bun as if she was about to perform on stage. Heavy mascara made her look older, more mature. A layer of powder concealed the dark shadows under her eyes, making her appear less vulnerable. But her father seemed to look right through the mask. The look of concern on his face made her heart beat faster, happier. ‘Have they done any tests? What’s the prognosis?’

‘All they do is tests. I’m convinced one guy is writing his PhD paper on me. I don’t mind, as long as he helps. But all he seems to care about is the sound of his own voice.’

‘So it could be a while?’

‘No one really knows.’ She didn’t want to talk about herself anymore. To change the subject, she asked, ‘What happened on the day of the accident? Were you speeding? Tired?’

‘Why do bad things happen to good people? In my line of work, I have to believe in luck. And every now and again luck turns its back on you.’

‘In your line of work? What is it that you do?’ She felt silly asking this question, as if she was an impostor, pretending to be this stranger’s daughter. And yet, she knew she was his daughter. She could feel the pull, the connection between the two of them, a lifetime of memories waiting to be discovered.

‘I take calculated risks for a living.’ He fell quiet, as if lost in thought. It was almost like he didn’t want to tell her. He cleared his throat before saying, ‘I run the family business for your mother. When your grandfather was alive, I was his right-hand man. Then I took over from him. But enough about me. How have you been?’

She shrugged. ‘Like a fish out of water. I don’t remember anything about myself.’ To her horror, she started to cry and couldn’t stop.

He pulled her close, enveloping her in his arms. Instantly she felt better. ‘I wish your mother was here,’ he said. ‘She’d know what to do.’ There was a wistful expression on his face. He must miss Mum so much, she thought. How could he not, when even Claire missed her and she didn’t even know her.

‘Where is Mum? She hasn’t visited us in hospital. I was wondering …’

‘She had to go away for a couple of months.’

‘Away where?’ How could she be away at a time like this?

‘She’s in California, looking after her elderly aunt.’

‘Tell me something about her. What is she like?’

‘Your mother is the kindest person I know. Everyone loves her. When she’s around, she makes you forget all your sorrows. The day I met her was the luckiest day of my life.’ His eyes were dreamy, as if he was no longer in the drab hospital room but somewhere far away where there was no sorrow, only joy. ‘Would you like to see a photo of her?’

‘More than anything.’

‘I always keep one in my wallet. It’s on the table over there.’ Claire passed the wallet to her father. His hands were shaking, from nerves or maybe because he was unwell, and he dropped the wallet. The contents spilled out all over the floor, his bed and his lap. Claire helped him collect coins, bank notes, loyalty cards for shops and cafés, a lighter, a silver chain – and a family photograph of the three of them. Earmarked and yellow around the edges, it looked like it had been repeatedly unfolded, examined and re-folded. ‘This was taken on a holiday in Paris. You were 15.’

With reverence Claire held up the photograph to the light. Her 15-year-old self was wearing a pair of shorts and a T-shirt, and her hair was a shade lighter, a touch longer and curlier. But it wasn’t herself she wanted to see. As she looked at her mother’s face, once again her eyes filled with tears. It was like looking at herself, only two decades older. Her mother had the same slim build, the same light hair pulled back into a bun. She radiated joy, while the Eiffel Tower was a misty silhouette behind her. Claire wondered if the joy was genuine. Didn’t everyone look happy when posing in front of the Parisian icon? Her father didn’t. He seemed gloomy, as if Champ de Mars in autumn was the last place he wanted to be.

‘Your mother loves her shopping, especially in Paris. And you love the museums. Every day it was a battle between the two of you, trying to decide where to go and what to do. I never took sides. No matter where we went, I’d get bored and complain. You called me a grumpy old man. You’d ask why I bothered to go away in the first place. I’d tell you it’s because I wanted to be with you. And you’d say, “but if you want to be with us, does it matter where we are? So quit your complaining and enjoy the three-hour shopping spree or the five-hour tour of the Louvre.”’

‘We look like a happy family.’ And they did. They looked like they wouldn’t be out of place on a Hallmark card.

‘We are. I’ve always made sure of it.’

Claire felt her heart soar. Yes, she didn’t remember the people in the photograph. She knew nothing about their relationship with one another, their life together, their hopes and dreams. But she had a family. She was a part of something bigger than herself. There was meaning to her life, even if she didn’t know what it was.

‘You can keep the photo if you like,’ said Tony.

‘Are you sure? What about you?’

‘I have it in here.’ He pointed at his heart.

Affectionately Claire squeezed Tony’s hands and stood up. ‘I wish I could stay longer.’ She realised how much she meant it. ‘But Paul needs to get back to work.’ She hugged him goodbye and added, ‘I know you’re putting your brave face on for me. You don’t want to upset me. But I need to know. How do you really feel?’

He was silent for a while. She couldn’t see his eyes. He was hiding them from her. When he finally looked up, she saw the truth. She saw sadness and pain as if something inside him was broken. Tony had a smile on his face but it wasn’t a happy smile. It broke Claire’s heart. ‘I feel like I’m living my worst nightmare. If only I could stay asleep forever,’ he murmured.

‘I’m so sorry, Dad. I’m sorry you feel this way.’

‘Don’t be. God has a plan for all of us. We all go through dark times. Every once in a while, we find ourselves standing over an abyss. The darkness is mesmerising. It pulls us in. Some people will want to jump. Others will find the strength to move away from the edge.’

‘Do you want to jump?’ she asked in a tiny voice.

‘Only time will tell.’ As she was about to walk through the door, he added, ‘Next time you visit, bring me something to read.’

‘Of course. I’ll see you later, Dad.’ I love you, she wanted to add but didn’t dare. It seemed to her that she had only met him for the first time today. And yet in her heart she felt like she had known him her whole life. If only she could remember. As she looked at him in silence, she felt so sad, but also warm inside. She was no longer a raft adrift in the ocean, a blank slate of a life with no past, no present and no future. She had her father. She was loved. She belonged.

* * *

Claire stepped outside her father’s room and into the waiting area, nauseous and dizzy, as if she was not on firm ground but on a ship swaying on stormy seas. When she looked up, she saw two police officers walking down the corridor towards her. A man and a woman, they looked like twins in their identical uniforms, both ginger and short, their faces tired and drawn, as if they had seen too much in the line of duty. Claire faintly remembered being questioned by them shortly after the accident. But she couldn’t recall what they had asked, nor what she had said to them. She couldn’t even remember their names. The first week at the hospital had been a blur.

They smiled at her in recognition and nodded in unison, then marched into her father’s hospital room without much ado or so much as a knock. Claire retraced her steps, stopping outside her father’s door, peeking through the gap.

The police had their backs to her but she could see her father’s face. What if he could see her too? Even though he wasn’t looking at her, his eyes on the police officers, his face stretched into an uneasy smile, Claire shifted her body slightly to the left, so that she was no longer by the door but leaning on the wall next to it. Nurses and doctors rushed past her, visitors and patients walked by at a more leisurely pace. None of them paid the slightest attention to a pale young woman with her hands clasped nervously and her eyes wide. She could no longer see her father or the police officers but she could hear them. The man introduced himself as PC Stanley. The woman said her name was PC Kamenski. Claire was surprised they had different surnames. They looked so alike, she expected them to be related.

‘Is this a good time? You seemed like you were sleeping,’ said the woman.

‘I was trying to. Couldn’t sleep last night,’ said Tony.

‘We can come back later if you want to rest.’

‘I’ve rested for two weeks. It’s been a regular holiday resort.’

The cops laughed uncomfortably. ‘Is it okay if we ask you a few questions?’

‘That’s what you’re here for, isn’t it?’ Her father sounded exhausted, and suddenly Claire felt a wave of anger so strong, she almost gasped. Why couldn’t the cops see how ill he was? Why wouldn’t they leave him alone? Didn’t they have real crime to solve and real criminals to catch?

‘Can I start with your full name, please?’

He told them.

His date of birth, address, occupation, marital status.

He told them.

And finally, ‘Where were you on the fifth of March at four o’clock in the afternoon?’

‘That was the day of the accident. I believe I was driving. But you already know that or you wouldn’t be here.’

‘Were you drinking that day? Taking drugs?’

‘Why don’t you ask my doctor? They would have done a blood test.’

‘Please answer the questions, sir,’ said PC Stanley in a voice that sounded tired rather than annoyed.

‘No, I wasn’t drinking. Or taking drugs.’

‘Who was in the car with you?’

Tony didn’t say anything at first and then coughed, clearing his throat and asking for a glass of water. Claire felt her body lean forward involuntarily, waiting for his answer. She held her breath.

‘There you are,’ she heard a loud voice behind her. Turning around sharply, she saw Paul approaching her form the direction of the doctor’s office. She almost groaned out loud. She desperately wanted to hear what her father had to say but at the same time she didn’t want Paul to see her eavesdropping outside Tony’s hospital room. What would he think? She moved away from the door and smiled at Paul. He asked, ‘How did it go with your father?’

‘Wonderful. I have no memories of him but I feel like I’ve known him my whole life. Did you talk to the doctor?’

He nodded. ‘Your father will need extensive physiotherapy. He has to work hard if he wants to walk again. His recovery might take a long time. He was upset and confused when he woke up. Pulled his IV out, scared the nurse. But he seemed to recover quickly. He remembers who he is, remembers what happened, which is extraordinary.’

‘Poor Dad. I wish I could have been there for him when he woke up.’

‘Are you ready? I have fifty minutes for lunch before I need to get back to work.’

Paul was already walking towards the exit and Claire trailed behind him, trying to keep up, when out of the corner of her eye she saw the police officers leaving her father’s room. ‘Can you wait for me for a minute? I want to speak to the police.’

She caught up with them near the reception. They seemed desperate to leave the hospital and who could blame them? When they saw her, they slowed down but didn’t stop. She walked with them. ‘Do you have a moment? I want to ask you something.’

‘Of course, anything,’ said the woman.

They found some empty chairs in a waiting area outside a room that wasn’t her father’s. Claire was glad. She didn’t want a nurse to wheel Tony out in his wheelchair only for him to see his daughter speaking to the police. For some reason she felt he wouldn’t like that. PC Stanley and PC Kamenski moved from side to side, trying to get comfortable. Although lacking in height, they were both wide-shouldered and looked out of place on the small hospital chairs, like grown-ups sitting in toddler seats. The woman took out a notebook and scribbled something down. Claire noticed her glance at the clock above their heads. There was only one question she desperately needed to ask. But she didn’t know how to bring it up, so she coughed and cleared her throat, just like Tony did moments earlier, and said something else entirely. ‘I’m concerned about my father. How did he seem to you? Was he confused? Having problems remembering?’

‘On the contrary. He seemed quite sure of himself.’

‘If you are concerned, why don’t you talk to his doctor?’ asked PC Stanley. He, too, glanced at the clock. Of course, thought Claire. It was lunchtime for them. The last thing they wanted was to be stuck in a hospital waiting area, talking to her.

‘Thank you. I will,’ said Claire. The police officers rose to their feet. Before they had a chance to say goodbye, she added, ‘One more thing. I’m not quite sure I was in the car on the day of the accident.’

‘Did you remember something?’ Both of them were staring at her now, all thoughts of lunch seemingly forgotten.

‘Not really. It’s more …’ She hesitated. She couldn’t tell them the truth. She didn’t want to contradict anything her father might have said to them. ‘It’s just a feeling I have.’

‘You are still confused. It’s understandable,’ said PC Kamenski softly.

‘Are you sure I was in that car?’

‘Positive. I pulled you out myself.’

Claire tried to imagine her fragile, broken body trapped in the back of a car on the side of a motorway somewhere. Tried to imagine the pain and the fear, police sirens blaring, strong arms yanking her out, and couldn’t. In her mind she couldn’t see anything other than this hospital waiting room, her father’s immobile body in a bed down the corridor, herself alone and afraid and searching for answers. Maybe her father was right. Maybe she hadn’t been in that car after all.

PC Kamenski was looking at her with suspicion and Claire felt tears perilously close. She almost opened her mouth and told the police officers everything. All her fears and misgivings and how confused she was. But she doubted they wanted to hear.

The man stepped from foot to foot impatiently. The woman closed her notepad. ‘If you remember anything, please don’t hesitate to call. Here is my direct number,’ she said, reaching into her pocket and placing a card in Claire’s hands.

Long after they were gone, Claire stared at the card but couldn’t see the writing from the tears in her eyes, couldn’t hear her husband’s voice from the noise in her head. She was lost in a maze with no way out.

* * *

On the way home, Paul suggested lunch at Claire’s favourite restaurant, Thai Basil. Having heard of it from Gaby and hoping it would trigger a memory, she agreed. Thai Basil was a red oasis in grey and rainy London. The furniture, the walls, the carpets, even the ceiling were a variation of that colour. Dotted around the room were porcelain elephants with their trunks pointing up – for luck, Paul told her. Claire relaxed into her ruby cushion, fighting to stay awake. Suddenly the day had become too much. Too many new faces and places, too much new information to process.

Taking a deep breath to stave off the panic, Claire closed her eyes and thought of her father. Immediately she felt better. The warm feeling she’d experienced earlier was back. He was just as confused as she was, even though he tried not to show it. And just like her, he clearly had trouble remembering the accident. She wasn’t alone, and neither was he.

‘I didn’t realise ballerinas ate Thai food,’ she said to her gloomy husband when the starters arrived. Although everything looked delicious, she didn’t seem to have much of an appetite. It surprised her. Other than the sandwich in the morning, she had had nothing to eat, so nervous was she about meeting her dad. The sandwich was a distant memory now.

‘Your diet consisted of grapefruit and Thai once a month, for which you punished yourself at the studio for days,’ replied Paul.

‘Sounds healthy.’

‘It wasn’t.’

‘I was being sarcastic.’

‘Oh.’

They were seated at a corner table, away from the other diners. Pouring some tea, she said, ‘What do you do for a living?’ Once again, she felt silly asking this question. She felt like she should already know the answer.

‘I’m a heart surgeon at the hospital.’

‘Which hospital?’

‘Yours.’

She wanted to ask him why she had only seen him twice in two weeks if he worked at the same hospital where she had been a patient. But she didn’t want to upset him. They sat in silence for a while. She shifted uncomfortably in her chair, while Paul absentmindedly checked his phone and glanced at his watch, as if he would rather be anywhere but sitting across from her at a restaurant table. Frantically she searched her mind for something else to say but couldn’t think of anything. Finally, Paul said, ‘Try these spring rolls. You love them.’

‘They’re delicious.’

‘Have another one. Have them all if you like.’

‘What about you?’ She pulled the plate closer.

‘I prefer this satay chicken.’

She picked up a stick of satay chicken, took a quick bite, took a bite of the spring roll and looked at him like he was a madman. Paul filled both their plates with stir-fry.

‘Tell me about our marriage. Are we happy?’ she asked when the food was gone – all but the fish cakes which she didn’t like.

‘Very,’ he said.

‘We don’t have any …’ Claire hesitated, trying to think of the exact word Gaby had used. ‘Issues?’

‘Of course not. What makes you think that? We are one of those rare couples who never argue.’

‘Tell me stories. Something to jog my memory. How did we meet?’

He squinted his eyes as if appraising her. Then he said, ‘The night I first noticed you, you literally danced into my life. I saw you through the window of your dance studio. You were practising the same sequence of steps over and over. I was transfixed. I think I forgot where I was going. It took me four days to find the courage to talk to you. Four evenings of watching you from the street like a common criminal.’

‘What did you finally say to me?’

‘Can I bum a cigarette?’

‘You asked a ballerina for a cigarette? What did I say?’

‘You said you didn’t have one but you could ask the janitor at the studio. And you did. Then I had to smoke it in front of you. I didn’t even smoke. It was horrible.’

‘But worth it?’

‘Absolutely. Six years later we were married.’ He spoke of what was possibly the most romantic memory of his life with a detached expression on his face, as if reciting a poem he had been forced to memorise.

‘And what is our life together like?’

‘It’s wonderful. We are very much in love.’ He glanced at the clock. ‘I wish I could stay longer but I have to rush.’

Perplexed at this change of subject, Claire watched his face as he paid the bill and led her outside, opening the car door like the perfect gentleman she knew he was. When they were slowly navigating the London traffic, she asked, ‘Do you know what happened on the day of the accident?’

‘You went to visit your parents that morning, like you do every Saturday. You were going to meet some friends for lunch afterwards. I don’t know how you ended up in the car with Tony. As far as I know, you’d made no plans with him.’

Paul dropped her off outside their house, and when she was about to walk through the front door, she turned around. He was still there, his hands on the steering wheel, the engine running, watching her intently, as if making sure she got home safely. She wondered why he felt the need to do that. It wasn’t like she was going to run away the minute his back was turned. She smiled at herself, at how silly that sounded, then waved and he waved back, before finally turning the car around and speeding away.

Chapter 3 (#u960d4df5-c19b-5e90-ab30-9b0beadc82b8)

From her balcony on the first floor, Claire watched as night bus after night bus pulled up opposite and groups of drunken passengers spilled out, stumbling, laughing and shouting. Claire envied them, wishing she too could be merry and carefree. It was past midnight and she’d spent most of the night staring at her mother’s face in the photograph, searching for answers. Eventually, she must have drifted off because she dreamt her mother stepped out of the picture and leaned over her. Angela’s lips moved but Claire couldn’t hear the words. She leapt up in her chair and looked around, half expecting to see her mother. But she was alone. All was quiet, and only the wind made the leaves whisper.

She returned to bed but couldn’t sleep, and at eight in the morning she got up. Gliding like a ghost from room to room, she felt like an actress hired to play a part of a stranger she had never met before. She questioned everything – the way she moved, the way she talked, the way she stood. Would the old Claire pause by the mirror as she made her way downstairs and study her face for a few seconds too long, as if she didn’t know it? Would she stand under the hot shower for five minutes, ten, fifteen, hiding from the world?

Waiting for her on the kitchen table was a note from Paul. Her heart quickened.

Breakfast in the fridge, someone from the hospital is coming to check on you at 9.30.

Gasping, Claire rushed back upstairs to get dressed and brush her hair. Only when she was satisfied with her appearance did she look inside the fridge where she found an omelette, a wilted tomato and a jar of olives. Ignoring the tomato and the olives, she ate the omelette cold.

A nurse was coming to see her. She wondered if it was someone she knew. It would be nice to see a familiar face. Claire wanted to know when her memory was coming back. She couldn’t get her life back if she didn’t remember anything about it. And she couldn’t fix her marriage if she didn’t know what was wrong between Paul and her. He might have told her they were the happiest of couples who never argued but she didn’t believe him. A happy couple didn’t behave like them, not touching, barely talking and not sharing a room. A loving husband would have visited her more often as she lay in her hospital bed, trying to make sense of who she was. Suddenly nauseous, she leaned on the edge of the dining table and closed her eyes, counting down from fifty to one, just like the nurses had taught her.

On twenty-five, she was breathing easier. On seven, the doorbell rang.

The man standing outside was dressed in a business suit and held a folder in his hands. He was small and wrinkled, and his prune-like face was stretched into a smile. He introduced himself as Dr Johnson.

‘A doctor? I was expecting a nurse,’ she said, clasping her hands nervously.

‘Is that why you won’t let me through the door?’ The doctor’s smile grew wider.

Claire realised she was blocking the doorway. ‘I’m so sorry,’ she exclaimed. ‘I don’t know what I’m thinking. I’m not myself these days.’ She stepped aside and the doctor walked in.

‘That’s why I’m here. To make you feel more like yourself.’

‘You think it’s possible? Will I remember everything? How long will it take? I didn’t realise doctors made house calls.’ Claire was talking fast, tripping over her words. She paused and studied the doctor, who made himself comfortable on the sofa.

‘That’s a lot of questions. We usually don’t make house calls, you’re right. But I’m a friend of your husband’s.’

‘You knew me before the accident?’

Dr Johnson nodded but didn’t say another word, hiding behind his folder.

‘I’m so sorry. I forgot my manners, among other things. You must think I’m awfully rude. Would you like something to drink?’

A dismissive wave in reply. It was clear Dr Johnson didn’t believe in small talk. He got straight down to business. ‘So, Claire, I understand you returned home from hospital yesterday?’ As if for emphasis, his finger pointed at something in his file.

‘The day before yesterday.’ Claire sat down opposite the doctor. With his small glasses perched on the tip of his nose, he looked like he had all the answers. Surely he would be able to suggest something, give her a magic pill that would help her remember. All she had to do was ask, and he would fix her. That was his job, wasn’t it?

Dr Johnson looked up. ‘How are you finding it so far? Overwhelming, I would imagine.’

‘That’s an understatement, Doctor.’

‘Don’t worry, it’s a normal reaction in a patient with memory loss when returning to their normal life. Have you been feeling unusually agitated lately?’ When Claire nodded, he continued, ‘Again, completely normal, nothing to worry about.’ He wrote something on the chart. ‘What about headaches?’

Claire rubbed her aching temples. ‘Not as bad as before.’

‘Have you been feeling confused? Disoriented?’

‘I don’t remember who I am. Of course I’m disoriented and confused.’

‘That’s—’

‘Perfectly normal. I know. Most of the time I feel afraid. Like something bad is about to happen. I think it’s my meds. They make me paranoid. Sometimes I wonder if I should stop taking them.’

Dr Johnson appraised her for a few seconds before replying, ‘I wouldn’t recommend that.’

‘No, of course not. Forget I said anything. And please don’t mention it to my husband.’