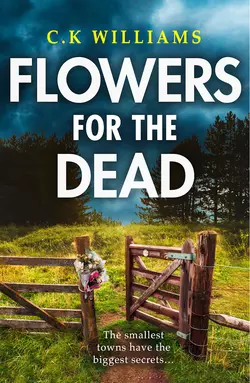

Flowers for the Dead

C. K. Williams

I am the reason girls are told not to trust strangers. I am their cautionary tale. Nineteen years ago Linn Wilson was attacked. Seventeen-years-old and home alone, she’d been waiting for her friends to arrive when she heard the doorbell ring. But when she opened the door, Linn let in her worst nightmare. The culprit was never found. It was someone I knew. I am going to find out who did this to me. Now, Linn is determined to get to the bottom of the night that changed her life forever. Returning to the village where she grew up, she knows that someone must know something. The claustrophobia and isolation of small town living means secrets won’t remain secrets for long… A wonderfully tense and gripping suspense thriller that will have you hooked! Perfect for fans of D. K Hood’s Detective Kane and Alton series and Sheryl Browne.

Flowers for the Dead

C.K. Williams

Copyright (#uc37d2a70-1a8e-50ba-b650-149c08b4efc8)

Published by ONE MORE CHAPTER

A Division of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

First published in Great Britain by HarperCollinsPublishers 2019

Copyright © C.K. Williams 2019

Cover Design © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2019

Cover Photographs © Shutterstock.com (http://Shutterstock.com)

C.K. Williams asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this ebook on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Ebook Edition © November 2019; ISBN: 9780008354398

Version: 2019-09-23

Dedication (#uc37d2a70-1a8e-50ba-b650-149c08b4efc8)

for Thérèse

and for my parents

Epigraph (#uc37d2a70-1a8e-50ba-b650-149c08b4efc8)

No coward soul is mine

Emily Brontë

CONTENTS

Cover (#u1e5a8404-a8d2-5897-bf9a-bef42239b23d)

Title Page (#u3bac391a-29bb-56a5-98d1-bbc4bd33692f)

Copyright

Dedication

Epigraph

The doorbell rings … (#u4189aa3e-e5cb-5d44-8c10-b1d6ae0d585c)

I. LIES (#ua60cda52-109d-5226-857a-9d2de2a16ef5)

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

II. TRUTH (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 9

III. JUSTICE (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 10

Acknowledgements

About the Publisher

The doorbell rings.

It sounds shrill in the small attic flat. The walls are slanted, lights turned off, the floral wallpaper barely visible in the dark. A small kitchen merges into a sitting room, an old dining table stuffed into the corner. The TV is on, but there is no one in sight. A pot of begonias is sitting on the windowsill. The flowers are drooping their heads. Outside, streetlamps cut stark shadows into the dark London street.

The doorbell rings again. Urgently, it resounds through the empty flat.

The bedroom door opens. A woman comes stumbling out. She must be in her thirties. She is dressed in floral sweatpants and a dressing gown, a little threadbare, the wool as dark as her eyes. Pulling it around herself, she stares at the front door. A shiver runs through her body, from the tip of her black hair to the soles of her bare feet, peeking out from the dressing gown. For a moment, she looks inexplicably frightened.

Then she takes a deep breath. Her lips are moving, although no words are coming out. You can do this.

Glancing at the windowsill for a moment, she then focuses on the door, rubbing the palm of her hand. It seems to be cramping. Her lips are still moving as she walks up to the door. Hesitantly, she presses the buzzer.

Through the peephole, the woman stares out into the hallway, cast in darkness. Someone is coming up the stairs. She can hear their steps ringing through the stairwell. Their laboured breaths. Their heavy boots.

The woman freezes. A drop of sweat runs down her neck, caressing her bare skin.

A dark figure comes into view. Distorted by the peephole. A man. Tall. Broad-shouldered, his face in the shadows. Breathing heavily. Raising a hand.

She takes a panicked step back.

The man’s hand finds a light-switch. Suddenly, the hallway is flooded with light.

He is wearing a delivery uniform. Carrying a parcel.

The woman lets out a breath, relief softening all of her features. Just a delivery man. Her muscles relax as she opens the door and steps out onto the landing. ‘Thank you for coming all the way up here,’ she says. Her voice is melodious if soft. She gives him a shy smile, which he returns. She is closer to forty than thirty, but men still like it when she smiles.

‘All right,’ he says. He makes her sign for the parcel, then hands it over to her. They say goodbye as strangers do. She watches him retrace his steps, making sure he’s left, then retreats into her flat.

The parcel is small, no bigger than a shoebox. She sets it down on the dining table, making the wood creak, and leans against the windowsill. Absent-mindedly, she feels the soil of her begonias, making sure they want for nothing as she looks at the parcel, careful curiosity written all over her face.

Until she sees where the parcel is from.

The moment she notices the address, her pulse quickens. It’s come all the way from Yorkshire.

The woman takes a step back. Her eyes race to the kitchen area, to the rubbish, the recycling bin. She could simply bury it deep, under carrot peel and the remnants of dead flowers. Her hands are shaking as she reaches for the parcel. Touches it. Hesitates. Looks back at the kitchen.

Again, her lips are forming words. You can do this.

She picks up the parcel and moves into the kitchen. For a moment, she is overwhelmed by an absurd urge to shake it. Hold it up to her ear and listen.

Then she turns away, forcefully, and reaches for a pair of scissors. Carefully, she cuts it open.

Inside the parcel sit only a few harmless items. Trinkets, really. A copper thimble, an old drawing of a wildflower, a few souvenir magnets from mountain villages all over Europe. A picture frame of an older couple, smiling into the camera, bearing an obvious resemblance to the woman. A letter sits on top.

As soon as the woman lifts up the letter, she sees it.

Underneath the paper lies a flower. Pressed and dried. Shaped like a bell, dark petals, black berries.

The woman recoils. Her breath is coming in hard, short bursts. A memory sears through her, like a crack in the walls of a dusty room. Sweat on her skin. Saliva running down her neck. A shout ripped from her throat and the taste of leather on her tongue.

She takes another step back. Her mouth is forming the words you can do this, you can do this, but the memories keep driving her back. Back until her body hits the wall. She digs her nails in, tries not to slide down. To keep herself upright. You have to fight it. But there is no way she can fight this. The dark berries, the purple petals.

The woman knows what sort of flower this is.

Her hands begin cramping. The soles of her bare feet. Her chest, her lungs, her windpipe. She reaches for her throat, the clammy skin as she tries to push the memories away.

This is deadly nightshade.

She knows because she has had it in her mouth. Tasted its sweet, deadly berries, nineteen years ago. Nineteen years ago, on a night just as dark as this one. The night when she opened the door to her parents’ house and let in her worst nightmare. The torn sheets. The shards of glass, the smell of lavender, the blood between her legs. Her raw throat and the taste of leather in her mouth.

The woman slides down the wall, silently, eyes fixed on the table. All you can hear is a soft swoosh as the dressing gown slithers along the wallpaper. The low noise of the telly. The occasional car driving by. Her finger, tapping on the floor.

It is only in the woman’s memory that another sound can be heard. And this is a new memory. Something she had burnt out of her mind as utterly as possible. Something she has not remembered until this very moment.

It is a doorbell.

And it is ringing.

Ding, ding, ding.

I. LIES (#uc37d2a70-1a8e-50ba-b650-149c08b4efc8)

Chapter 1 (#uc37d2a70-1a8e-50ba-b650-149c08b4efc8)

LINN

I am the reason girls are told not to trust a stranger. In the small town in the Yorkshire Dales where I grew up, the homes as lonely as the mountains, what happened to me is every parent’s cautionary tale. They tell it to their daughters, their precious little girls, their nieces, cousins, sisters, mothers. Don’t open the door to strangers. Don’t walk home too late at night. Don’t wear that skirt.

It has been nineteen years, and I’ve never been back there. It has been nineteen years, and I’ve never told anyone this story. That is why what I’m about to do is so utterly, breathtakingly stupid. Or brave. Maybe that’s one and the same thing, anyway.

I am in our bedroom, packing the rest of what I will need. Listening carefully for any sounds from outside the bedroom, I’m stuffing my things into an inconspicuous shopping bag from Tesco. In a hurry, I put the parcel that I received last night into the bag, making sure it is stowed away safely. The dried flower of deadly nightshade now sits in my pocket. My movements are harried. Frantic. Energetic. As they have not been in many, many years.

I’m about to go back there. Drive from our London flat onto the motorway and ever further north into the dark autumn night. To the lonely house where I grew up and the High Street in the village where I played knock, knock, ginger as a child with my friends under the red boughs of the rowans. Where we always used the same code when we rang the doorbell, until all of the village knew it:

Ding, ding, ding.

I take the book I’m reading from my nightstand and throw it into the bag next to the parcel. Quickly, I tie the bag closed and hide it under the bed, covering it with the extra bedding we keep there. I can feel the pulse in my palms, my heart beating frantically.

For nineteen years, I believed the official story. The police said it, and I believed it. At seventeen years of age, still living with my parents in Yorkshire, one night I opened the door of our house to a stranger. My parents were not at home, gone to see a show in Manchester. By the time they came back, the police were already there. Their daughter had already been raped, and could not recall anything except the pain splitting her open, blood running down between her legs. She could not remember how she had got there, or who had done it.

I couldn’t remember.

I straighten. Close my eyes. Listen to my heartbeat, trying to calm myself down. I am thirty-six now. For nineteen years, that is the story I believed.

But it is not the true story.

I turn to the dressing table, looking into the mirror, putting my hair back in order, strands that have come undone in my hurry. My face looks just the same as yesterday, but everything else is changed: when I looked at the dried flower in the parcel, a memory came back to me. Like a titan arum suddenly coming to bloom after years of nothing, the deadly nightshade made me remember.

It made me remember how the doorbell rang that night.

Ding, ding, ding.

That was why I opened the door in the middle of the night. Because I thought it was someone I knew.

I stare at my face in the mirror. The lines around my mouth and my eyes, on my forehead. For nineteen years, I believed it had been someone I didn’t know, a stranger who’d made the most of their opportunity and had been long gone before I was found.

But no stranger would have rung the doorbell like that. Everybody in the village knew that that was my code. Our code.

It was someone I knew.

Even in the mirror, I can see that my shoulders are shaking, my chest, my hands. With fear, and with fury. That is why I am going back to Yorkshire. Back to the one place where I swore to myself I would never return. Back to where it all happened.

I am going to find out who did this to me.

Turning away from the mirror, I let my eyes sweep through the bedroom once more. There is nothing else I need to pack. My suitcase is already downstairs in the boot of the car. I am ready. All I need is for Oliver to leave.

I can hear him puttering around in the kitchen, just beyond the bedroom door. He is setting the table for our farewell dinner. He is leaving for a conference tonight.

Taking a deep breath, I look into the mirror once more. I put on a smile, watching the corners of my mouth lift. Then I leave the bedroom.

Oliver smiles at me when I emerge, as kind as absent-minded. He whistles as he sets the table. If it can be called that. My husband pushes out air through his lips while he hums and calls it whistling. It would be infuriating if it weren’t so utterly, thoroughly him – sweet and funny and a little bit awkward. His woollen sweater is orange and blue. I gave it to him.

I try and pretend that everything’s normal. Water my begonias on the windowsill, however hopeless a case it might be, making sure they have enough to drink. I try not to look at Oliver, because the truth is, while he’s here and doing that silly whistle, I will never bring myself to leave. Suddenly, I feel the need to tell him. Tell him everything. It’s like a pull, or more like a push, like he’s pushing me against the wall. I will tell and then stay here and keep living this life that we have got used to, but which can’t give him what he wants.

Determined, I walk into the kitchen and turn off the stove where the mash has been simmering. Dinner’s ready, nothing fancy, just mashed potatoes and pork pies from the supermarket down the street. Oliver doesn’t mind that I’m not a world-class cook, and I like to think my baking makes up for it. I love baking. Made our wedding cake myself. That was also because money was a little tight – when isn’t it, really, with the rent you have to pay these days? – but still. It was a feast of chocolate, almonds, vanilla and marzipan, decorated with edible flowers.

While I serve the mashed potatoes in small bowls on our plates with the pies next to them, Oliver reaches for the remote. ‘You want me to turn off the TV, Linnsweet?’ he asks.

‘Thanks, Sweet-O.’ The name jolts through me as I say it out loud. That’s what I call him, Sweet-O. Have always called him that. It was a joke at first, because of what his mum used to call him. My sweet Oliver. Sweet-O, I used to tease him. He came up with Linnsweet in return. They stuck.

He’s set the table nicely, I realise as I sit, with a candle and the cloth napkins his mother gave us for Christmas five years ago. After we had just moved here. It is our third flat. We’ve been together ever since we were seventeen. Went to school together. People sigh wistfully when they find out. Those are the most romantic stories, aren’t they, they say, where you marry your childhood sweethearts.

Except the story that’s told about me isn’t one of romance. Except that I’m not good for him. I have always known this, known that he could have done so much better for himself than a traumatised high-school girlfriend who did not even manage to feed the fish regularly. That he deserves so much better. A real family, a proper partner. But I was never brave enough. Never brave enough to go, not even for his sake. When you love someone, you let them go, they say. But how could I let him go?

Until I received the doctor’s letter, three months ago. The results were clear. Oliver is not going to have any children if he stays with me. He will never have a family.

Oliver digs in; he could never wait for anyone when it came to food. Nor can I, actually; for such a mediocre pair of cooks, we sure love good food. But not tonight. Tonight, I sit across from Oliver, clutching the fork in my hand, incapable of taking a single bite. My knuckles feel like they are about to burst through my clammy skin. In sickness and in health, to love and to cherish. I know he won’t leave me. Not after he’s stuck with me for nineteen years. He is too loyal. Too kind. But I cannot take that away from him, too. He has always wanted a family. He was so excited, that morning three months ago when we thought I might finally be pregnant. I had woken up to his hands on my body, to his lips on mine, the scent of a fresh bouquet of flowers and warm croissants on the dresser. The fit of nausea had been so sudden, I didn’t even make it to the bathroom before I threw up. He thought it meant we were going to be a family. I thought so, too, so I went to the doctor’s.

Turns out that’s not what it meant. If there’s one thing I can’t get, it’s pregnant.

I look at Oliver, watch him eat, talk, his soft face, his shaved head hiding that he’s going bald and grey, that deep line on his forehead and his bright blue eyes, bright even after all these years. Till death do us part. It is so hard sitting here and saying nothing. Funny, because I thought I was good at lying.

I hope he won’t look into the car on the way out, when he leaves for his conference. I hid the suitcase under a woollen blanket and bags of groceries. In case he looks into the boot, out of curiosity. I hope he won’t realise. It would break his heart. My husband. For better, for worse.

But how much worse?

Finally, I also make myself take a bite. The mash turned out fine, actually. Then I ask him about the conference. It calms me down just to hear his voice. The corners of my mouth twitch into a half-smile. The conference will last for a week. He has been on the road more and more this past year to go to conferences, to workshops, but this is the first time he will be delivering a keynote. He has been so excited, so nervous, so busy, he’s hardly had the time to think about anything else. To realise that I had become quieter. To think about what I might have been thinking about. To wonder about the fact that I never told him what came of the visit to the doctor’s except to say we’d been wrong.

‘Linnsweet?’

I look up at him. Maybe he made a joke. Maybe I missed it. There is a crease on his forehead – he’s worried about me. Poor Oliver, always having to worry about me. Nineteen years of little else.

Again, I make myself smile. ‘Sorry. You like the pies? They turned out quite nicely, didn’t they?’

A grin flits across his face. ‘Always so modest,’ he teases.

‘It was intended as a compliment to Tesco,’ I insist, corners of my mouth twitching again.

This time, he laughs for real. I would love to laugh with him, but my throat constricts. He has sacrificed enough, I remind myself as I force another bite down my throat. Let him go.

*

Oliver smiles at me when dinner is over. Blows out the candle. This one’s blue. They’re always blue. Then he takes me into his arms, his strong arms, maybe not as strong as they used to be, but still a place where I can’t move once I find myself in them. To have and to hold. ‘Will you be okay while I’m gone?’ Oliver asks. ‘Doing anything nice? Go see a show, maybe? Bake something for me?’

Tell him. Just tell him.

I open my mouth.

‘Sweet-O,’ I say. He looks at me. His blue eyes and large pupils, blown wide from how we have been pressed against each other.

I swallow. He wants me so much. Even after all these years. All these years that he has taken care of me.

Now it is my turn to take care of him.

‘Maybe I’ll just stay in and wait for you to come home,’ I say, every word painful, my mouth twitching. ‘Keep the couch warm.’

‘Do some laundry, maybe?’ He laughs.

‘That sounds crazy,’ I manage.

‘I know, right? Lock him up now, he’s a nutter.’

‘I’ll iron your shirts,’ I say, feeling that non-smile on my face again. He needs his shirts, now that he’s in management, and frankly, he’s rubbish at ironing. When they offered him the promotion, from nursing to public health manager, he said, Hell, yes. That is why he’s been going to all these staff training courses, all these conferences. I always knew he would be great at it. Oliver has always wanted to help people, told me so on our very first date. No matter how hopeless a case, he doesn’t give up on anyone. Sometimes I think that’s why he’s stuck with me so long.

He laughs again, lets me go and grabs his travel bag. I breathe in, then out. Press my arms to my body, my legs together so that I won’t pull him back towards me. He deserves to be happy.

When his cab has arrived, we go downstairs together. He is taking the late-night train to Cornwall. He likes trains. I put on my coat, my gloves and scarf and the hat I made for myself when I took up knitting for a bit. The front door needs a heavy push to open, then we step outside. It’s a cold autumn night.

‘I miss you already, Linnsweet,’ he says and kisses me.

I kiss him back and try to tell myself to do the right thing, not to cave now. Not to be selfish. To let him go. He looks at me, so much want in his eyes and desire and regret. ‘I’m sorry I’ve got to go,’ he says, and I cannot speak.

Don’t speak.

So all I do is nod.

Then I watch him walk to the kerb.

I watch him greet the driver, a friendly ‘How’re you, mate?’ I watch him put his bag in and wave at me.

Then I watch him glance at our car.

He hesitates.

My pulse quickens. Slowly, he turns back to me. My throat goes dry. He looks at me, in my coat, with the gloves and the hat and the scarf, too. I feel perspiration in my armpits and my thighs and the palms of my hands, like sweaty fingers stroking my skin. Let me do the right thing.

He turns to the driver. Tells him something. Then he walks back towards me. ‘Did you forget something?’ I ask, my voice sounding normal even as my tongue feels like it is stuck to the roof of my mouth.

He takes my hand and kisses its back, making my insides twist. ‘Don’t you need help with the groceries?’

I shake my head, glad I’m wearing gloves. Otherwise, he might notice the sweat on my palms. The fluttering of my pulse, the shaking of my fingers. ‘No, that’s all right, Oliver.’

‘No, come on, you don’t have to carry them up on your own. He said he could wait. You should have told me, I’d have helped you when you got in.’

‘No, really, you’ll miss your train,’ I say, laughing even, playfully pushing him towards the cab. ‘Go, Mister Manager.’

Oliver doesn’t budge. He does not like being pushed. ‘You should’ve told me.’

‘I’m sorry,’ I say, rubbing my hand across my lips. There are so many things I should have told him. ‘The only thing that’d make me even sorrier is if it made you miss your train.’

As he gets into the cab, I let out a relieved breath. I watch him until the cab has turned around the corner, towards the city centre, waving till I can no longer see him.

I wait five more minutes. Ten.

He does not come back.

I stare at the corner my husband disappeared around. The red-brick house, the bare tree on the corner, the blue light of a TV set flickering through the curtains. It takes me a moment to notice that there is something wet on my cheek.

Confused, I take off my glove and lift my hand. There are wet tracks on both sides of my face. Wiping the liquid away, I realise they are tears.

I don’t know if they include this in their story. When they tell their cautionary tale about me, up in Yorkshire once night has fallen. Do they add, And after it all happened, she decided it was safer to just stop feeling things? That’s what trauma is, girls, not being able to feel anything, not even sad when you let the person go that you love. Don’t open the door to strangers. Don’t walk home alone at night. Don’t wear that skirt.

I hope they do. I hope they tell the true story.

Well. If we knew what the true story was.

I hesitate, car keys already in my pocket. I’m ready. If I only knew how to do this. I haven’t gone anywhere without Oliver, except to the shops, in years.

Just take one step at a time.

Slowly, I start walking towards the car, hands buried in the pockets of my jeans.

Already in the driver’s seat, I glance up at our flat one last time. It’s then that I realise I’ve forgotten something. Two things, actually.

I rush back upstairs and unlock the flat once more. I’m leaving Sweet-O everything, of course, everything except what I need and he can’t use, my clothes and my makeup and the last picture of my parents, taken two months before their deaths. It was one year ago that they left us.

I hesitate as I look at the CD rack; all my hand-signed records of The Dresden Dolls are already in the car, but there are still The Police’s Best Of, Blondie’s Greatest Hits. I take a deep breath, then I leave them. Oliver loves our music. And it may be selfish, but I want something for him to remember me by.

What I came back for aren’t CDs. It’s my bag with the parcel, and my begonias. The bag in one hand, I leave the bedroom and walk across the living room to the windowsill facing the busy street below. ‘Left behind just because you droop your heads?’ I whisper to my begonias, running a finger along the green stems. They are hardy begonias, Begonia grandis. I got them on a whim in the summer, when they were looking so sad and thirsty inside Tesco.

Wrapping them in a plastic bag, I look around the flat one last time. I reach into my pocket and take out the note I wrote for Oliver. That’s all I am brave enough for. It says that I am fine, and that this is the best way, and that I don’t want him to come looking for me. That he has spent too many years of his life taking care of me already. That I truly wish him all the very best and a real family with someone who can give him what he needs. Someone who will be good for him.

My hands are trembling as I put it on the table. Look at it, the innocent piece of paper, the blue candle on the table, blue like my husband’s eyes. Feel him push me against the wall.

Stay.

The doorbell rings. I flinch. Then I remember it is past ten, and the drunks are starting to stumble out of the pub across the street. Some of them think it’s funny to play a round of knock, knock, ginger with the pub’s neighbours before going home. First time it happened to me, when we’d just moved here, it was the middle of the night. I woke up in panic, the cold sweat of fear leaving traces all over my body, like insistent fingers. With time, I got used to it, though. At least they usually don’t piss in your doorway when they’ve rung all the bells.

Then it rings again.

They never ring again.

That’s Oliver. It must be Oliver.

I rush to the door. Press the button. Nothing happens. I press again. Someone pushes against the front door, downstairs, I hear it echo through the hallway. It won’t open. Jammed.

I dash downstairs to open it, carrying my bag and the begonias. If it’s him, I’ll stay.

When I open the door, it is not Oliver, not his soft, bald face. Instead, there is a delivery woman, red hair tucked under her cap. ‘Bloke named Oliver sends you these,’ she says unceremoniously. ‘Hope he’s not a creep.’

‘We’re married,’ I say, shuffling my bag and the begonias around so that I can take the large bouquet she hands me – autumn flowers, red and orange and yellow, so tasteful.

If only there weren’t also stems of lavender tucked deeply into the bouquet.

‘Doesn’t answer my question,’ she says and puts out her hand.

I stare at the bouquet; it is the same he bought a week ago, before I went to the doctor’s. Then my eyes drop to her fingers. Her nails are polished blue. Behind her, two drunks are falling out of the pub doors.

Then I realise she wants a tip. I fumble with my wallet and press a few coins into her hands and watch her leave. I put the bouquet down as soon as she is out of sight. Now all I’ve got to do is walk out, unlock the car and drive.

I hesitate. Breathe in the scent of the flowers at my feet.

Then I push out. Out into the cold and the dark. I haven’t wanted anything in a long time. But I want this.

I want to find out who did this to me.

THE NEIGHBOUR

It is early morning when I hear the engine roar, lying awake as I often do. It is barely dawn, the light outside white and grey. Must be an old car, the way it sounds. I saw lots of cars like that before I moved here. Now, not so much.

A country road leads past my drive, single lane, old stones piled up into low walls on both sides, grey during the day and black at night. It is absurd. Even after all this time, I still start when I hear a car. They come down this road so rarely.

Surrounded by starch-white pillows and sheets, I listen to the sound of the engine, trying not to be nervous. You can hear them coming a mile off, cars like that. Do not be nervous. And do not get up. It is an obsession, my therapist told me. You are obsessed.

The sound of the engine turns louder. I turn onto my back, fiddling with the bed sheets. They are clean and stiff. There are no other houses down this road, bar one.

Is that why you bought the Kenzies’ home? my therapist asked me. No, I lied, I needed more space.

The windows are frail things. I feel the draft wafting in. When I heard the Kenzies were moving, when I saw the price they had put the house up for, I did not hesitate. I phoned up Mrs Kenzie and went round and signed the lease the following week.

The car is up on the crest of the hill now.

I do not have an obsession.

I get up, bare feet cold on the old wooden floor. The boards creak when I put my toes on them. The summer nail polish came off a while ago, only traces left, dark green like the forests where I was born. I pull back the curtains, white lace so that I can look out and watch the road even when they are drawn.

The house is situated off the dirt road; when it snows, you cannot make it out of here without a 4x4. Like in Gdańsk, but that feels very, very far away. It always smelled like salt there. I still wake up and miss the sea.

The car comes into view, headlights cutting through the woods.

It has the right colour. I have seen it on her social media.

A frisson runs through me.

You are obsessed, my therapist says, her voice very calm.

Aren’t you? I would like to ask her back.

I see it, a white blur through the gnarly trees and their bare branches, a white blur in the heavy fog. I watch it.

My body is shivering.

It is the right make.

It could be her.

LINN

Mist thickens into fog as dawn approaches. I am heading along Grassington Road after I turned off the A59 at Skipton. The narrow road dissolves into a milky grey mass. Houses are turned into shadows, rising and falling by the side of the road as I pass them. Trees seem to suddenly appear, gnarled branches reaching across the road, as if they were reaching for me. The steep slopes of the peaks are familiar even in the dark. The grass, grey in the morning, is glinting with dew. I even recognise the old stone walls, black blurry lines climbing up the bare slopes. My fingers are clenching the steering wheel so hard my knuckles hurt. Have been ever since I passed the sign: COUNTY OF NORTH YORKSHIRE.

The fog thickens and thickens as I continue down the A684, on and on. I pass through Aysgarth and along the Ure. This must be Worton. Then Bainbridge, this sharp bend to the right, past the low houses and the roses climbing up their walls, sprawling like spidery fingers in the fog. I am so very close now. On and on I go, turning off the A684 onto the single-lane side road leading to our village. I thought it would make me nervous, these narrow roads, not wide enough for two cars. But it is not the roads I am worried about. Nor is it the shadows passing me on both sides, the silhouettes of trees and walls and roadside heath.

I do not slow down until I see the silhouette rise on my right: the crippled old oak tree by our village sign. The village I know so well, even when I cannot see it. The narrow old bridge across the brook, the High Street where I used to play, the farns growing thick on the steep slopes surrounding us. The Dresden Dolls are filling the car with their disturbing sounds, louder and louder the closer I get to my parents’ old house.

It is far out of the village, sitting on a dead-end dirt road where farns and goatsbeard and marsh orchids grow, with only one neighbouring house, the Kenzies’. And even they lived a mile off before they moved away. They were friends, Mum and Dad and the Kenzies. Best friends. It was they who sent me the parcel – the Kenzies. In the letter that came with the parcel, they explained that they had moved out of their house, out of that village, not half a year after my parents’ death. They said that they were now settled in their new home in the East Riding, by the coast, and that they wanted to send me a few things of my parents’ they’d found as they’d unpacked their boxes. The dried nightshade, for example, which my mum had given to them for safekeeping. She hadn’t said what they were keeping it for, only that she didn’t want it to be thrown away, but that she no longer wanted it in her house, either.

That was Mum’s thing, drying flowers. They were all over the house. Even this one. Deadly nightshade.

The fog is so thick that I do not see the graveyard, either. Thank God. I know I pass it on the left. Know where it is. Know whose graves I haven’t been to see.

I do not slow down but drive on, drive on until the dirt road comes into view, sloping up into a forest before it leads to the two lonely houses. I turn.

At the crest of the hill, driving past the Kenzies’ old house, I take a glance, but the fog is still too heavy. I only catch a glimpse of the sharp gable and the uppermost window, emerging from the white, milky mass.

For a moment, I believe I see someone standing there. A slim silhouette. Dressed all in white.

Watching me.

The car stutters. Quickly, I push my foot down on the accelerator. When I look back up, the window is empty.

The Kenzies never said whether they had found a buyer. My begonias bob their heads up and down on the back seat, peeking out of the plastic bag as I keep driving. They make me think of our flat in Leyton. Make me glance in the rear mirror. Just to check.

As if I had to. This is the last place Oliver would expect me to go. On our computer, I’d checked websites for a few cheap places to stay in Brittany, in Norfolk and Kent, just in case. But wherever he would suspect me to be, it wouldn’t be here. Not after I didn’t even return for my parents’ funeral, twelve months ago.

My face turns hot as I think of it. There is something wet in my eyes. I blink rapidly as the road turns narrower and narrower, from a dirt road to a path in the woods, snaking its way back to the main road on the other side of the forest. It disappears amidst the pale stems of the sycamores and the winding branches of the ash trees, between the wych elms and bare rowan trees. I used to take my bike down that path, even when it was dark. It seems far too frightening now that I look at it, dwindling like a dying brook in the headlights ahead of me.

I nearly miss our drive even as the fog keeps clearing. At the last moment, I recognise the downy birch and the high hedge and derelict stone wall on my right. I realise my hands are shaking so badly that I cannot stabilise the steering wheel. As if there are climbing plants sprouting in my lungs, it is difficult to breathe.

*

Braking, I turn into our drive. Between the shreds of fog, the old house emerges: two floors, made of limestone, standing between hunched hawthorn and sharp holly and tall birches. There is an abandoned garden and a wooden front porch with a roof, damp and dark.

You can do this, I tell myself. You have to do this if you want to find out what happened to you. This house is a part of it. This house surrounded by woods, with a front porch and a set of chimes by the door that I gave to my mum when I was fifteen, the small bells still dangling in the wind when they left for the hike they would never return from.

The moment I come to a stop at the bottom of the drive, the moment I turn off the engine, I sink back into my seat.

I made it.

For a moment, all I feel is light. As if I am floating. I made it. I did the right thing.

A little unsteady on my feet, I get out of the car, the cold wrapping me into its cool arms. I open the boot and take out my suitcase. It’s heavy. Then I fetch the begonias from the back seat. ‘We made it,’ I whisper to them. ‘Well done, my darlings.’ I’m a florist, and let me tell you, you don’t pass your exams if you don’t talk to flowers.

The pot in my arms, I walk up the front porch, a rather eccentric addition of my father’s. I walk past the chimes on the front porch.

Wait.

I stop. Turn to the side, still on the wooden steps. I remember the chimes. Dangling onto the stairs, announcing every visitor. Remember their sound. Remember the doorbell. Remember the sweat and the noises.

But the chimes are gone.

Putting down the begonias carefully, I walk up and down the porch, then onto the dead meadow on both sides, looking for them. They must have been blown away by the wind. Or a cat came and … I don’t know. The Kenzies told me in their letter that the chimes were still here. But I suppose that happens. No one has been here since my parents left.

A hiking accident. That’s how they died. Here, too. Right here in the Dales.

Returning to the front steps, I take my begonias back up and look for my parents’ keys in my handbag, blinking rapidly, trying not to think about the Kenzies’ voices over the phone, stained with tears as they delivered the news. My hands are cramping, so are the soles of my feet. Instead, I think about having a bath, or a shower, after I have lugged the suitcase from the car into the house. A nap on the couch, even, once I’ve got the heating back up and running. Before I face my parents’ bedroom. Before I make a battle plan.

Finally, managing to fish the keys out of my bag in spite of the cramp in my hands, I bend over to put them into the keyhole. It is a bit rusty, I think at first, when I do not manage to turn the key.

Then I realise that is not the case.

I cannot turn the key because the door is already open.

THE DETECTIVE INSPECTOR

Things get stolen here. Not often, mind, but it does happen. There is no such thing as 100 per cent security. Other than that, we are doing well. Break-ins, occasionally. This is an area where people don’t exactly come from old money. Some, though. And the break-ins, they have become more frequent. It is a problem.

A set of chimes, though? To be honest, I think she’s blowing things out of proportion a little, don’t you? I don’t want to say hysterical. It’s not like she’s shouting. But a set of chimes. You might think the wind has blown it away or some animal has come and torn it off. Maybe the Kenzies took it when they moved. Who would go all the way out there just to steal some chimes?

I look at her. Clutching that flowerpot to her chest and trying very desperately to smile. I haven’t seen Linny in years. Recognised her straightaway, though, when she walked in, and what a shock that was. To see Linny back here, Linny of all people, after all these years. How long has it been, twenty years, nineteen? Hellfire! Nineteen years since I last saw her. I mean, not even at the funeral. Can you believe that? The only child not showing up to her parents’ funeral? And that house of theirs just sitting down in that hollow at the end of that dirt road, all empty and nobody using it?

So, you know, a right shock, seeing her again. But shock’s nothing new to a policeman, is it? So, when Linn shows up like that and tells me her parents’ door was open, not just unlocked, I thought it was serious, I really did. But then we drove there together and went inside, and nothing had been stolen or damaged or even moved, and I looked at that rusty old thing of a lock and have to say I’m not surprised it didn’t hold.

Didn’t say that, though. We’re back at the station now and I want to help her, I do. She’s always been a darling of ours, Little Linny from Down-in-the-Dip. That’s what we used to call her parents’ house, Mark’s and Sue’s, because of how they built it right at the bottom of that hollow in the woods. It’s the only house on that road except the Kenzies’. But the Kenzies don’t live there any more. Mind you, it’s none of my business whom they sell their house to. I only know, I wouldn’t have picked that one. That’s all I’m saying. But I guess they didn’t want to stay after Mark and Sue were gone. Bloody hiking accident.

‘You’re in good hands here,’ I tell Linny as I take out a form from the shelf behind me. The police station has been renovated. It’s all white and modern now and there are neat lines on the floor telling people where to stand and where not to go. Not to come too close to the counter, for example, unless they’ve been asked to. That must be a London thing. Where they have shootings at police stations when someone from Tower Hamlets comes walking in. Or Leeds, at the very least. Here, I tell everybody to just come up to the counter. Right up.

‘Come here, Linny,’ I tell her. She’s in ratty jeans and a worn coat that used to be quite nice, I think. Her hair has turned a little bit lighter. Thinned out, too. I remember her hair as black as the forest up by her house, and her eyes as large as a doe’s, even when she was a teenager. Pretty girl, that. She moved away pretty early, right out of school. With her boy. Her man. Oliver. Good man, that one. Promising swimmer, he was, and I should know, I coached the team for a while. Shame he didn’t go into swimming professionally. He could have really made it as a swimmer. Better than Jacob Mason, even. Olympics, absolutely. Gold for England, that would have been something!

So, we were sorry to see them go. Her parents especially, of course. But I did not blame them. How could I?

I knew it was my fault. Know it was my fault she never came back, not even to visit. I tried to do all I could to help, but she didn’t want to stay after all that.

All the more reason why I want to help her now. That’s why I don’t say, You know, the fair was in town a couple of months ago, may have been a few teenagers out for an adventure, or just time passing and wearing down that old lock, you know? Taking the chimes as a bonus, so to speak.

Besides, I get it. Alone as a woman, you’d get flayed easily, wouldn’t you? Scared, I mean, you’d get scared easily. So I hand her a form and when she’s filled it all out, I fax it straight up to Northallerton (tried and true, a fax machine). Looks like it puts her at ease. She’s smiling again, and that’s all I want.

Let me tell you about all the ways this girl could smile. She had the most expressive face as a kid – you could always tell there was something going on in that bright mind of hers. Especially when she’d played a trick on you and you hadn’t found out yet. There was that twitch in her face. She loved to play tricks, Little Linny did. Now, her smile’s friendly, maybe a little shy. I walk around the counter to show her out, putting my hand on the small of her back to reassure her. Let her know I’m here.

‘I’ll keep you posted on any developments, Linny,’ I say.

‘Thank you, Detective.’

Something tugs at my chest as I remember her as a little child, coming to play knock, knock, ginger with her friends in the town centre, giggling behind the bushes on the other side of the street as I pretended not to see them. Ding, ding, ding, that’s how they always rang the doorbell. Everybody in the village knew it.

‘Please, Linny, call me Graham.’

There was that boy with them, too. A bit weird, wasn’t it? Even as teenagers, they still stuck together. Linny and Anna and that boy. Teoman Dündar. He didn’t play footie or go loitering around pubs with other young men his age, smoking cigarettes. Wasn’t that what folks of his background did? Instead, always trailing those lasses. Maybe that’s what people do where he’s from, though. Don’t take women seriously, do they? Linny’s parents were worried, in any case, I remember that.

I watch her leave, still trying to smile, dropping purple petals where she goes, watch her through the bulletproof windows (another London regulation, that, I’m sure). There is a feeling just beneath my skin. A prickling sensation.

Just a set of chimes.

I return to the counter, tell Angela, I mean Constable Johnson, that I’ll be right back. Then I go into the back. Down the set of stairs, grey concrete, low ceilings. Along the narrow corridor, dark walls and blue doors with a couple of cells behind them. At the end, the only wooden door, the one leading to the archives.

Takes me a while to dig out her file. It’s still on paper. I can’t believe I haven’t looked at it in so long. The prickling turns stronger.

I have sharp instincts, I do. I wonder if it’s coincidence. I wonder if she knows.

That Teoman is back as well.

LINN

I know it’s silly to have gone to the detective. To Graham. I couldn’t believe it at first, when I saw it was him standing behind that counter. Not because of how much, but of how little he seemed to have changed. Sure, he looked different, but he still talks, moves, listens exactly like he did all those years ago.

I try to relax my hands around the handle of the suitcase. Graham was kind enough to take note of my complaint, and the lock was very old. It may have come undone, simply, like the chimes. It gets fairly windy here, even down in the hollow in the woods. We’ve arranged for a new one to be put in. The locksmith will be by later today.

Now I am standing in the hall of the house, clutching my bags. The house I have not been in for nineteen years. Slowly, I put down the bags and push open the first door on the left. It leads to the mud room. Cloakroom, my mum called it, a euphemism if ever I heard one. There is the low wooden bench we threw all of our coats on, and the rack for the shoes and the wellies, and the shelf for the gardening tools that Mum said she needed at hand, not all the way out in the shed in the garden. All of it is covered under white sheets. The Kenzies must have done this after the funeral. I pull off the sheets, one by one, dropping them onto the floor. The tools are still up on the shelf, some of them rusty, some of them still shining bright, bought only recently, never to be used.

I put my coat down on the bench and toe off my shoes. A pair of trainers sits on the rack still. They were my father’s.

I go back out into the hall, the kitchen the first door on my right, the staircase to the first floor right ahead. I go into the kitchen first, pulling away sheet after sheet, uncovering birch wood and local pottery, the blue heavy plates and mugs from my childhood. The sitting room next, windows and the back door leading out into the garden, framed by high bookshelves. Looking out, I can see the shed behind the house by the tree line, blue paint flaking away.

And then I climb the wooden staircase, the carpet soft under my feet. The stairs still creak in all the right places as I ascend to the first floor, to the two bedrooms and the bathroom. Here, the furniture under the sheets is all of dark wood. It was my grandma’s, and so are the doors. The house still looks so much like it did back then. It even smells like back then, because everywhere, on every available surface, sit Mum’s dried flowers.

Stopping at the top of the stairs, one hand on the bannister, my yellow socks on the blue carpet, I stand and stare. At the door leading to my parents’ bedroom. The room where it happened. I stand and stare and breathe.

Involuntarily, I turn back around. I have to go into town. I need to get some more groceries before the locksmith comes over. Besides, I should also begin investigating. Find out who is still here. Find out where to start.

I collect the sheets I dropped and leave them in the mud room, before I check the cupboards in the kitchen, making a quick shopping list. Then I grab my coat from the mud room and rush back outside. With the grey, bright light in my eyes, I drive back to the main road, allowing it to take me back into the village. The fog has lifted, and I find the short-stay parking lot up on the High Street without any trouble.

I kill the engine, looking through the windshield at the village where I used to play. The narrow stone bridge across the brook is right in front of me. Even sitting inside the car, I can hear the sound of the water rushing down across the stones and into the valley. It used to be our favourite place, this bridge and the brook. It is surrounded by cottages and houses with names, RIVER VIEW and BLYTHE’S COTTAGE and THE OLD DAIRY.

And on the High Street goes, across the bridge up to Cobblestone Snicket, which looks like a house but really is only a façade leading to an old, narrow snicket, an alley with a cute café and an antique shop. Its façade’s been repainted, blue and red now instead of green and yellow. Other than that, it hasn’t changed. Not even the High Street seems to have changed, the small houses of grey stones or white plaster turning grey, the shops and the pub and red parasols packed up for the cold season, sitting amidst gnarled alder trees and bare rowans. I remember my father made jelly from the rowan berries in our garden and put it on the table when we ate game, its taste bitter and tangy.

I realise I missed that taste. I missed the alder trees and the rowans and bright red parasols.

Sitting in the car, I have trouble tearing myself away from the view. Now that I am here, where do I start? Originally, my plan had been to return to the house first, get my bearings, unpack my bags. Go into the bedroom I haven’t entered in nineteen years, see if it would help me remember anything like the nightshade did. But the village is as good a place to start.

Determined, I take a notebook out of the glovebox, a pretty one from Paperchase, and dig into my old handbag, the red leather faded to a pale pink, in search of a pen. I chance upon the USB key in the shape of an astronaut that I bought seven years ago, as well as two dangerously dry chrysanthemums I nicked from the neighbour’s balcony, and an old bright-red lipstick, before I finally find a pen at the very bottom of the bag. Crouching over, I prop the notebook up against the steering wheel and think.

This is where I grew up. This is where I rang the doorbells playing knock, knock, ginger, all up and down the High Street. Everybody knew. Everybody could have done it.

But not everybody was at the crime scene that night. When I came back to my parents’ house, I was not alone. The police were already there, Detective Inspector Walker. He had been called in by my best friends, Anna Bohacz and Teoman Dündar, who had found me. And I have a blurry memory of Jacob Mason’s face, my ex-boyfriend. Quickly, I jot down their names:

Detective Inspector Walker

Anna Bohacz

Teoman Dündar

Jacob Mason

I hesitate as I write Jacob’s name. What was he doing there? We had been friends as children and dated as teenagers, but we had not been on speaking terms for a while at that point.

Tapping the pen against the steering wheel, I keep thinking. Of course, there is also Miss Luca – the school therapist. She wasn’t at the scene, but we went to see her afterwards. We all did, separately of course. Anna, Teo, Jay and me.

I add her name to the list. Then I stare at the pen, the red plastic, a freebie from the London Planetarium. Wasn’t there someone else? There is a shadow at the back of my mind, but whenever I reach for it, it recedes, like a whisper just loud enough that you can hear it, but too quiet to understand what is being said.

Graham would know; I should ask him. There are places I could try visiting, too, retracing my steps of that night: the party at Jacob’s house; the way home from the village through the woods; my parents’ bedroom.

I shiver as I think of the bedroom. As I remember the searing pain, the scent of lavender, of sweat and blood. My parents’ sheets, damp under my bare skin. My dress, torn all the way up to my breastbone.

I can feel my skin go clammy. Quickly, I add a list of places to the piece of paper, my hand shaking so badly I nearly scrawl the letters all over the page.

Detective Inspector Walker

Anna Bohacz

Teoman Dündar

Jacob Mason

Miss Luca, school therapist

Jacob’s house (party)

way home (woods?)

bedroom

*

I’m shaky as I get out of the car. I will have to speak with them. With whoever’s still here. And if there is one person who’ll know, it is Kaitlin Parker.

I walk out of the parking lot, across the bridge and up the High Street, listening to the rush of the water as I hope that Kaitlin’s copy shop’s still there, the one where I interned when we had to get some work experience. Kaitlin was our village gossip. She used to know about all comings and goings in this place. She always wanted to get out of here, but she wouldn’t be the first not to make it.

As I walk, I realise I had forgotten how many flowers there are in the village. They grow in everyone’s front garden, in every window box, even just on the side of the road: roses climbing up the walls of shops and cottages, bushes of marsh orchids growing in front of the Old Dairy, yellow hay rattle and white bogbean peppering the riverbank. Someone must be nursing them, otherwise they would not be in bloom still so late in the year.

I have just passed the bank where I opened my first account when I see it: the copy shop. As I approach, I realise that they have a new sign, bit more modern, but it is still Kaitlin behind the counter – Kaitlin and Anvi.

For a moment, I stop and watch them through the window. It comes as a shock. Kaitlin has grown so fat. Her face is still the same, but it seems distorted, like it has been pushed out into all directions, like dough that’s been rolled out.

Then I see my own self reflected at me in the window and hurry inside.

‘Ey up,’ Kaitlin calls out the moment I walk in. Recognition shoots through me at the familiar greeting, the phrase I have not heard in years. ‘What can I do for you to—’

She doesn’t finish the sentence. I see her small eyes widen as she takes me in. Within moments, her expression turns from naturally friendly to flabbergasted. ‘Hellfire, is that … Linn?’

‘Hello, Kaitlin,’ I say, a little embarrassed. A grin spreads out over her face.

‘Is it really you?’ she says as she comes around the counter. She wears felt. Her brown hair has thinned out. She still blinks far too often, looking at me with her bright-green eyes. ‘Is it really? I can’t believe it. I really can’t. Think I gotta sit down.’ Instead, she grips the counter, staring me up and down unabashedly. ‘Wow! Sorry, I just … Never thought we’d see you again! Now that your parents, God rest their souls …’

‘Yes,’ I say hastily, mouth twitching before I shape it into a grin. ‘It is good to see you. Good to be back. Hello, Anvi.’

‘Ey up, Caroline,’ Anvi says. She always used my full name. Said it was a sign of respect. She is as slim as ever. It’s the first time that I’ve seen her wear a sari, though. It looks pretty, all orange and purple. She is much more collected than Kaitlin, who is still gripping the edge of the counter, looking a lot like she could use a drink. At least Kaitlin’s grinning, though. Anvi, on the other hand, is watching me with what can only be called hostile suspicion. ‘How have you been?’ she asks.

‘Good,’ I say, corner of my mouth twitching into another smile. ‘Very good. And you two?’

‘Great,’ Kaitlin says. ‘Just peachy.’ She has taken out her phone. ‘Sorry, luv, I just got to let Mum know, she won’t believe it when I tell her …’

See? Village gossip.

Anvi is still watching me. ‘Everything is fine. A lot has changed, of course. Not that you would know. But at least the shop is doing well.’

She is dropping the ‘g’s at the end of her words just like Kaitlin. I have missed the way people talk up here. No ‘g’s at the end, no ‘h’ in the front, that dialect that instantly feels like home. Suddenly self-conscious, I wonder if I sound like a Londoner to them. ‘I’m glad to hear it.’

We fall silent. It turns awkward as we look at each other, looking for the traces the last nineteen years have left. Wondering if we look as tired, as old, as the person we see standing across from us. Wondering who these strangers are that use the voices, the tics, the gestures of people we once knew. Abruptly, I remember being sixteen and helping print T-shirts for hen dos. An exciting night out in Leeds, in Blackpool. Remember worrying about my braces. Remember how Kaitlin and Anvi were only a few years older than me, really, always fighting behind the curtain in the back of the shop, trying to make ends meet.

This isn’t exactly a boom town. When the weaving loom went out of fashion, everyone who had legs to walk on left the Dales, and that was in the eighteenth century. There’s only 18,000 of us left now. If there is any reason for people to have heard of us, it will be because of Emmerdale. Highly arguable if that’s an honour.

And I left too, didn’t I? Even though I loved it here. The memory comes back to me as unexpectedly, as painfully as the nightshade: the way it felt to live here and love it. Even this copy shop, these two wide-eyed young women, trusting that their community would have need for their business. I remember that Anvi wore trousers even though her father didn’t want her to and how Kaitlin could make amazing cinnamon rolls. I remember the wildflowers in the Dales and how they made me want to be a florist: the small blooms of pink bell heather and the beautiful golden globeflowers. I remember Mum showing them to me, all the way at the back of our garden, where Dad had cut the first line of trees.

She showed me the deadly nightshade too, the dried flowers in her bedroom and the fresh ones in the woods. ‘Kings and queens used them to assassinate their enemies,’ she told me, speaking conspiratorially, as if she was telling me a secret. ‘Ten berries can kill a grown man. And two are enough for a cat or a small dog.’ Their taste is sweet, so sweet you won’t be able to tell, really, if they’ve been mixed into a heavy red wine. I should know. ‘They are called Atropa belladonna,’ she explained to me as she showed me the exact shape and colour of the plant, taught me to tell it apart from the bitter nightshade. ‘That’s from Atropos, one of the Three Fates, the Greek goddess who cuts the thread of everybody’s life. And belladonna means pretty lady; they were used for makeup once upon a time, that’s why. Only this pretty lady is here to kill you,’ she said, and pressed me close to her, both arms around my shoulders. ‘But don’t worry,’ she whispered into my curly hair. ‘Mummy and Daddy will protect you.’

The memory almost makes me choke. Dragging myself back to the present, I pull out the USB key I brought. I did not only spend last night packing: I also updated my CV. I have a little money saved up, but I’ll be needing a job soon. ‘I would like to print something, actually,’ I say, before the silence in the copy shop can turn even more awkward.

‘Aye,’ Kaitlin says, taking the little astronaut off me with her free hand. She is still gaping at me whenever she glances up from what is quickly turning into texting the entire village. ‘Seriously, I can’t believe it! How have you been? How is Oliver?’ Her fingers are sweaty. I flinch. Her eyes widen again. ‘Sorry! Have I put my foot in it? Here I am, just assuming … Last time I talked to your parents, they mentioned that you two … It’s just we don’t get any news of him any more since his parents moved away, I mean with their divorce and all that …’

I laugh it off. To have and to hold, till death do us part. ‘No, it’s fine. We live in Leyton now. I trained as a florist. Oliver went into nursing, he’s a health manager now, he … We have this lovely flat in London, no balcony, but still, I mean, can you imagine finding a flat in London at all – it’s insane.’

‘I bet,’ Kaitlin says as she walks to the computer. Still holding her phone, continuing to type with one hand. ‘Must be down south. Just wait till I’ve told Mum, she won’t believe it, she really won’t, it’s …’

‘So you have come back with him?’ Anvi asks. Her eyes are narrowed. She hasn’t let me out of her sight once.

‘Oh no,’ I say lightly. ‘No, not at all.’

‘Where’s Oliver, then?’ Kaitlin asks. ‘Hellfire, haven’t seen him in nineteen years either, have we?’

I knew they would ask. ‘At a conference,’ I say and can’t help but think of him. What he’s had for breakfast. If the pillows in the hotel are soft enough for him. The blinds dark enough. He will be so busy with his presentation. I wish I could have helped him more, supported him.

I know Oliver won’t realise what’s happened till he comes back. He will be texting me from the conference, trying to call, too, but he knows how I get sometimes, especially when he’s gone: not answering the phone, not texting back. He knows I bury myself sometimes. He’s learned not to push.

‘He is not with you, then?’ Anvi is watching me. Why is she watching me like that?

‘No,’ I say, the moment that Kaitlin makes a pleased sound. Actually, she almost squeals.

‘Oh, CVs? You want to apply for jobs here? It would be so good to have you back, luv! People don’t come back often, you know how it is. Not a lot of jobs. I mean, they do sometimes come back, but usually for Christmas or funerals …’ She peters out. Keeps glancing at her phone. It pings. And pings and pings. ‘See, they won’t believe me! Maybe we could take a photo, for proof.’

‘Yes, definitely looking for a bit of work,’ I say. Trying to sound as casual as I can, even though the words alone are scaring me. I haven’t worked in years, not since 2008, you know? Not a lot of demand for florists since then.

But my training still counts, doesn’t it? They need people, don’t they? That’s what they’ve been saying in the papers, at least, and on TV. Well, in the health sector mostly, not exactly in floristry. Because of Brexit. Anyway, I need to get these CVs sent out. Maybe a florist in Northallerton, or Leeds, or even further north. Maybe in Scotland.

But that’s not what I came here for. ‘So,’ I ask, trying to sound casual as I think of my list. ‘Who else is still around?’

‘Oh, quite some people,’ Kaitlin goes on, obviously in her element. ‘The two of us, of course, we never left, did we, Anvi? Even though we always said we would.’

‘Evidently,’ Anvi says drily.

‘What about the Masons?’ I ask carefully. ‘What about Jacob?’

‘Yes,’ Anvi says, putting as much distaste into the one syllable as she can. ‘He is still here.’

‘Oh, don’t be like that,’ Kaitlin says as the printer starts up. ‘Yes, the Masons still live here, in the same house, too. Though it’s only Jacob now.’ She leans over the counter conspiratorially, motioning for me to come closer. ‘It’s outrageous. He sent his mother to a nursing home a couple of months ago. Barely seventy and already in a nursing home, can you believe it?’

Anvi lets out an angry snort. ‘Instead of caring for his mother at home, where she has lived all her life. It is a disgrace.’

Kaitlin just seems gleeful. ‘Isn’t it just?’ she says, sounding rather thrilled about it. Then her eyes widen. ‘You went out with Jacob for a while, didn’t you?’

‘And Miss Luca?’ I ask, avoiding her question. Anvi is narrowing her eyes at me again. As if she is seeing right through me. ‘I’m just so curious,’ I offer. ‘After so many years.’

‘’Course you are,’ Kaitlin says happily. ‘Antonia Luca’s still around, too. Has her own practice now. She lives on the outskirts of the village, on the corner of Meadowside and Foster Lane. Nice house, that. Number 32.’

As the printer whirrs away, I try to memorise what they’re telling me. I hope I can still find the Masons’ house, hope they haven’t changed it too much. Kaitlin is still fiddling with her phone, in all likelihood preparing to take a photo. They are both so shocked still. Kaitlin’s even shaking a little with excitement; Anvi’s all tense. As if I was a robber. Or worse. ‘Why didn’t Oliver come?’ she asks. ‘How is he doing?’

I will myself not to think about him. ‘Like I said. He is at a conference. Do you still have envelopes, too? Could I get, oh, I don’t know, ten, maybe?’

Anvi hands them to me, then collects my money. ‘It is just such a coincidence, isn’t it? That you and he would both come back to town?’

‘Oliver won’t be in town,’ I say, trying not to let my impatience seep through. I haven’t come here to talk about my husband. My – about Oliver.

‘I do not mean Oliver,’ Anvi says, her voice hard, even as Kaitlin’s camera clicks. ‘You know perfectly well who I am talking about.’

‘I am afraid I don’t,’ I say as I take the CVs that Kaitlin hands me. I feel the little hairs on the back of my neck rise. On my arms. As if a cold draft has come in through the door. From behind the counter.

You know perfectly well who I am talking about. Suddenly, I can’t wait to get out of there. ‘Well, it was lovely seeing you two.’

‘So chuffed that we got to see you, luv!’ Kaitlin says, walking me to the door, obviously happy to see me even if she still doesn’t quite believe it. ‘In a bit!’

Without turning back, I walk out the door. If I walk a little more quickly, nobody has to know. I might be in a hurry. Hurrying to get to the post office before it closes. When do post offices close in a place this size these days? If there’s a post office left at all. I think of where it used to be, by the car park, the back lot where we smoked in secret, and I decide that I might get the groceries tomorrow – there is enough left for a few meals, I’m sure. Anything not to think about him.

He cannot be back.

Teoman swore he would never come back.

THE NEIGHBOUR

The car returns at noon. I am upstairs in the corridor, both arms buried elbow-deep in the second wardrobe, ready to bring out the winter clothes. My summer clothes sit next to me in a pile on the floor, all freshly washed as I listen to the sound of the engine coming up the road.

It is her.

I know it is her.

LINN

The house smells like baking. It is a smell that makes me feel all loose-limbed. All happy, like it hasn’t in years. The locksmith has been by and put a new lock in. And I sent out ten applications. Surely, one of them will work out. I’m a trained florist, did some gardening work as well. Something just has to work out.

Getting ready for bed, on my first night in this house that I was so scared of, I am in the bathroom, a plate of shortbread precariously balancing on the edge of the sink next to me. No cinnamon rolls. I have earned shortbread. As I remove my makeup, I don’t think of silly Anvi and her silly allusions, but of the businesses, their sleek websites. I will have clients. Colleagues. After-work drinks. There might be promotions. There will be money.

I need to reopen my bank account. Put in the money my parents left me, the money that will tide me over in the meantime.

Once the makeup has come off, I bend over the sink and have a drink straight from the tap. The water tastes wonderful up here, clean and fresh, very different from London. I collect it in both hands, then splash it onto my face. Drying my skin off on my parents’ plush towels, I look into the mirror once more. For a moment, it doesn’t even scare me, the prospect of work, of a new job, a new life. That I will have to leave the house every day. That I will be in a place I don’t know, that I can’t navigate. That it might be loud and dirty and confusing and there will be buses with a silly numbering system. Like when Oliver and I moved to London for the first time. It was our second flat; we’d never lived on such a busy street … It was lovely though. Oliver had found it by marching straight into a local pub, getting drunk and then asking everyone in the vicinity if they knew of somewhere that was available. It got us a two-bedroom flat. Not bad. Only one set of keys, the heating working intermittently at best, and a leaky tap, but still not bad.

Now, it does not scare me, the prospect of a new place. No, it actually … it gives me a thrill. Like seeing the shock on Anvi’s and Kaitlin’s faces when I walked into their shop today. Like I couldn’t be overlooked. Like I was really there.

I haven’t felt a thrill like that in years.

It is what bolsters me as I take one last look into the mirror. Take up the plate. Straighten my shoulders.

Then I go into my parents’ bedroom.

The floorboards creak as I cross the threshold. The bed in the centre of the room is still the same, its frame of dark wood, its tall headboard, the small nightstands. The bed almost disappears under all the pillows and blankets. The wallpaper has changed, midnight blue on one wall, a wooden texture on the others. To the right of the bed is a door to the en suite I did not use – it feels too much like my parents’ bathroom still – and on its left a window overlooking the hollow, right above the roof of the front porch.

Carefully, I put the plate of shortbread onto the nightstand on the right. My nerves are fluttering. Have been ever since I decided to sleep up here tonight.

To see if it will trigger a memory.

I stare at the bed. At the spot at its foot, the wooden floorboards in front of it.

That is where I woke up.

Slowly, I pad over there. My dressing gown billows up around me as I lie down. My bare skin touches cold wood, my thighs, the sides of my legs, my panties. I put my cheek to the floor, feeling the cold seep through me, and close my eyes. Ready to remember.

The floorboards creak. Outside, the wind sneaks through the hollow, through the treetops, shaking their leaves, whispering at the edges of the old window frames. The room smells dusty. There is a hint of another scent, but they are both overshadowed by the shortbread, still warm, sitting on my nightstand.

It smells really good, that shortbread.

I sit back up.

Well, this isn’t working.

I let out a breath I didn’t know I’d been holding. Then, out of nowhere, I feel something rise in my throat. A giggle. It comes out before I have even realised what is happening. Goodness, look at me. Crouching on the floor, hoping for some kind of revelation.

I stand up, dust off my nightgown, draw the curtains and return to the hallway to take out fresh sheets. On the way, I fetch my begonias as well, and once I’m back inside the bedroom I put them on the nightstand next to the shortbread. Then I take the nightshade from the pocket of my dressing gown and stow it in the drawer of the nightstand. Making up the bed with the fresh sheets, I realise that I do not recognise them: black flowers climbing across dark blue fabric, a silken touch to them. They must be new. They feel soft on my skin.

Taking up a piece of shortbread, I sink into the bed. Gently, I stroke the purple petals of the begonias sitting on my nightstand as the warm dough fills my mouth. They have raised their heads a little. I feel the earth in their pot, just to make sure they have had enough to drink. Then I smile at them, swallowing the shortbread. ‘Goodnight, my darlings.’

Snuggling down into the covers, I breathe in their familiar smell. Still the same detergent. It feels as if I’d never left. As if Mum and Dad were merely away on a holiday, a hiking weekend in the Highlands. And the dried flowers, too, spreading their scent all through the house. Mum had such a passion for them. People brought dried flowers to her funeral, hers and Dad’s. Heaps of them. There were piles of dried roses, of rosemary and thyme and laurel, even some bell heather and globeflowers. The Kenzies sent me pictures. They were dropped onto the coffins, they surrounded the funeral wreaths gifted by those who didn’t really know my parents.

One of those wreaths was mine.

I know what you must be thinking. I wish I could make you understand what it’s like to hear that the two people who’ve always been there, as long as you can remember, are gone, and not feel anything. Your mum, who used to be your idol, with her white hair and incredible bravery, and your dad, who would hug you like it meant everything just to hold you. To look at your husband as he takes you into his arms, trying to give you comfort, and swallowing down the truth, which is that you’re feeling nothing. That he might as well have told you about the death of a badger he had hit on the way home, or a wasp he had squished outside the pub with his beermat.

Maybe that was when it became unbearable, actually. When I decided something needed to change. That I needed the truth. Maybe it wasn’t the Kenzies’ parcel and the deadly nightshade. Maybe that was just the last straw.

We had a ceremony in London, of course, Sweet-O and me. That’s how I said goodbye to my parents.

I turn on my back, staring at the white ceiling. And here I am. Lying in their bed. Finally back in their house. Our house.

The deadly nightshade is back too, sitting inside the nightstand drawer, on top of one of Mum’s old Chilcott catalogues: one of those mail-order companies where you could get homely pillows and handmade blankets and scent diffusers. Every single one of their products came with a pouch of British lavender. I wonder if they still exist.

Above the bed hangs a spray of lavender. When my parents still lived here, it always smelled so much like lavender in this room, like there wasn’t any other smell in the world. Only once or twice a year would my mother go for rosemary and thyme instead, usually in winter and spring. She would never have both out at the same time; it was either lavender or rosemary and thyme. Now the scent is so subtle it barely registers with the shortbread right next to me. It’s comforting. The pillow feels soft beneath my head. I feel like I am floating. It may be a little frightening, but it’s also exhilarating. To be so light. I did the right thing.

I will have the truth.

Before I turn off the light, I have another piece of shortbread. I feel like I can have as much shortbread as I like now. Don’t know what to call this feeling. Maybe it’s the shortbread feeling. The-world-is-your-shortbread.

Involuntarily, I giggle again as I close my eyes. The pillows smell like home and the crumbs taste delicious and the night is deep and dark.

It is still dark when I wake up.

The room smells like lavender. Just like that night. The odour of the old, dry flowers feels heavy in the air. Like it is pushing down on the blanket. Like it is wrapping itself around me.

My legs are sweaty. So are my armpits. It smells.

Slowly, I breathe in and out. It’s cold. Why do I feel trails of perspiration on my body when it is so cold? Like light cuts on my skin.

I turn onto my other side, keeping my eyes closed. Go back to sleep, I tell myself.

Why is it cold?

Why does sweat run across my skin like clammy fingers?

I open my eyes. The curtains are too thick. It is dark.

I close my eyes again. Maybe I’m running a fever. That’s why I might feel cold and hot at the same time. That’s it.

Wrapping the blankets more tightly around my body, I tell myself to go back to sleep and close my eyes again.

I am already dozing off when I think:

Why did I wake up?

The doorbell rings.

I turn onto my other side, mumbling into the pillow. The drunks from the pub. They’ll go away eventually. It smells like lavender.

It takes me a moment to realise.

I am not in Leyton. I am not in my flat with Oliver.

I open my eyes. It is dark.

That is what has woken me.

Someone is standing in the hollow. Someone is standing in front of my door.

Someone is ringing the doorbell.

THE NEIGHBOUR

Her house is dark in the night.

THE DETECTIVE INSPECTOR

The one case I couldn’t close.

THE NEIGHBOUR

I am not obsessed.

LINN

I cannot breathe.

Those aren’t the drunks from the pub.

I lie as still as I can. There is no pub. There are no neighbours, nothing but the Kenzies’ old place. This is a back road, a dead end, dwindling down to a path through the woods. Dead trees on all sides, rising like thin fingers through the thick fog.

The sheets rustle beneath my shaking hands. I ball them into fists. It might be nothing. They might need help. Maybe their car broke down.

On a dead-end country road.

I feel the sweat collect beneath my armpits. Between my thighs. There is no sound. Only the stale smell of dead flowers and perspiration. There is someone standing down on the porch. In front of a large, dark house. The door isn’t sturdy. They could come in if they put their mind to it.

Maybe they already have.

Maybe they are already inside, walking through the hallway, towards the stairs leading up to my bedroom. The carpets, grey and silent, swallowing the sound of their steps. More than one person. Or just one man. One man and his silent steps on the stairs to my bedroom. The closed door coming into view. His hands are gloved. His breath is going quickly. His pupils dilated. His heart beating with excitement.

I almost choke on my own breath.

Stop. A car’s broken down, that’s it.

Should I check? What if they need help?

They would ring again then, wouldn’t they?

Wouldn’t you ring again?

I pull the blanket up to my nose. There are no sounds at all. I didn’t hear a car. You hear cars from miles off on this road.

As the minutes pass by, I start wondering. Did I only imagine it?