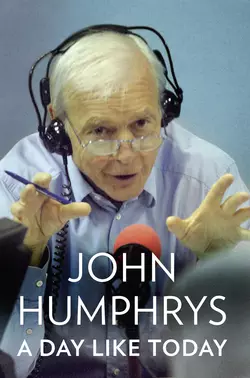

A Day Like Today: Memoirs

John Humphrys

For more than three decades, millions of Britons have woken to the sound of John Humphrys’ voice. As presenter of Radio 4’s Today, the nation’s most popular news programme, he is famed for his tough interviewing, his deep misgivings about authority in its many forms and his passionatecommitment to a variety of causes. A Day Like Today charts John’s journey from the poverty of his post-war childhood in Cardiff, leaving school at fifteen, to the summits of broadcasting. Humphrys was the BBC’s youngest foreign correspondent; he was the first reporter at the catastrophe of Aberfan, an experience that marked him for ever; he was in the White House when Richard Nixon became the first American president to resign; in South Africa during the dying years of apartheid; and in war zones around the globe throughout his career. John was also the first journalist to present the Nine O’Clock News on television. Humphrys pulls no punches and now, freed from the restrictions of being a BBC journalist, he reflects on the politicians he has interrogated and the controversies he has reported on and been involved in, including the interview that forced the resignation of his own boss, the director general. In typically candid style, he also weighs in on the role the BBC itself has played in our national life – for good and ill – and the broader health of the political system today. A Day Like Today is both a sharp, shrewd memoir and a backstage account of the great newsworthy moments in recent history – from the voice behind the country’s most authoritative microphone.

(#uf192a6ac-418b-5fc5-bf50-b19d2d1196fb)

Copyright (#uf192a6ac-418b-5fc5-bf50-b19d2d1196fb)

William Collins

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.WilliamCollinsBooks.com (http://www.WilliamCollinsBooks.com)

This eBook first published in Great Britain by William Collins in 2019

Copyright © John Humphrys 2019

Cover image © Jeff Overs/Getty Images

All images courtesy of the author unless otherwise stated.

Every effort has been made to trace copyright holders and to obtain their permission for the use of copyright material. The publisher apologises for any errors or omissions in the above list and would be grateful if notified of any corrections that should be incorporated in future editions of this book.

John Humphrys asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780007415571

eBook Edition © October 2019 ISBN: 9780007415601

Version: 2019-09-13

Dedication (#uf192a6ac-418b-5fc5-bf50-b19d2d1196fb)

For Sarah

Contents

1 Cover (#ud1f01468-19a4-5f89-bd04-8225e2e76ed1)

2 Title Page

3 Copyright

4 Dedication

5 Contents (#uf192a6ac-418b-5fc5-bf50-b19d2d1196fb)

6 Prologue

7 Part 1 – Yesterday and Today

8 1 A childhood of smells

9 2 The teenAGE pAGE

10 3 Building a cathedral

11 4 A gold-plated, diamond-encrusted tip-off

12 5 A sub-machine gun on expenses

13 6 A job that requires no talent

14 Part 2 – Today and Today

15 7 A very strange time to be at work

16 8 Why do you interrupt so much?

17 9 ‘Come on, unleash hell!’

18 10 A pretty straight sort of guy?

19 11 Management are deeply unimpressed

20 12 Hamstrung by a fundamental niceness

21 13 A meeting with ‘C’

22 14 The director general: my part in his downfall

23 15 Turn me into a religious Jew!

24 Part 3 – Today and Tomorrow

25 16 The political deal

26 17 Shrivelled clickbait droppings

27 18 Goodbye to all that

28 Picture Section

29 Also by John Humphrys

30 About the Author

31 About the Publisher

LandmarksCover (#ud1f01468-19a4-5f89-bd04-8225e2e76ed1)FrontmatterStart of ContentBackmatter

List of Pagesiii (#ulink_d3a8f057-cb41-590b-b0d8-4c4be5af50ee)iv (#ulink_1cd3dd7e-0b9b-509c-93e7-74e05c132b9f)v (#ulink_ac023449-6826-5ac4-bd1a-58fe4a3fa8bd)1 (#ulink_d29a0ad8-5a2f-5e79-907a-2fcae940f647)2 (#ulink_4b78dc0d-bac2-5347-aa7b-bb7c0ee306cb)3 (#ulink_b8100873-63f1-59c6-b0fa-8fabbd2d4d78)4 (#ulink_d0f150bf-2584-579d-ba03-5400ec5903de)5 (#ulink_93a3dfe1-4c2d-56cd-bd2b-18fabdd67cf3)7 (#ulink_867df108-a699-5f4e-a117-61f5ebf7b3e7)9 (#ulink_d8bfb4cf-aee4-5008-9c22-ab87b34931f0)10 (#ulink_36ae02e5-dbc5-54a9-a189-7f397533bf54)11 (#ulink_44f9c9b9-687f-5302-ba2b-be6b553e6d81)12 (#ulink_ae524b20-b34a-5cfb-9c2b-2cdb224144cd)13 (#ulink_e06d5348-114f-5840-92e2-c2c8e2baa6b8)14 (#ulink_0a4df85b-cffe-55f5-a8ad-deae8d457b32)15 (#ulink_56f94e00-0b92-5b7e-8728-c26a9dd265fd)16 (#ulink_d216c097-67d5-5fea-b280-585bd47ddd49)17 (#ulink_06216175-45a9-5e97-8549-e6f38d68386a)18 (#ulink_0165ceec-5564-5a0e-a127-dfe7d5e0d6de)19 (#ulink_358ec895-2a61-5e02-843b-cdd68d2a1225)20 (#ulink_3846b007-f4ea-515e-83ed-9c01eafa61cb)21 (#ulink_4e1855a0-65a3-5de7-8d84-46ff05a6aadc)22 (#ulink_86a32a2a-277d-590a-bec6-b3efad30d23b)23 (#ulink_9826e55d-6a64-5d01-87ee-12b27760e1c0)24 (#ulink_6320352f-113b-57d3-91c7-884cd431eb74)25 (#ulink_cfe57390-4165-55e6-b1df-fe198d3790cc)26 (#ulink_e42d8019-b1be-5415-9140-e8ee96e5d5e1)27 (#ulink_9b9e4c19-993b-5ed9-a3a0-e9704dc7953b)28 (#ulink_551fabc6-5d8a-5466-ac62-6e5fdd595970)29 (#ulink_ffc40ad3-6450-5f9f-9955-95ec86ca3b44)30 (#ulink_98e83835-9778-5b8e-9d1b-3c83acd36a7a)31 (#ulink_06d5a6cf-c4fa-5c21-b753-102965fa329d)32 (#ulink_3945eab7-bd4a-5dc1-9a39-06594ba038f5)33 (#ulink_5d19c2b7-7856-5a3e-8b5d-5f8eca4c247b)34 (#ulink_a172b7a3-4a8c-5ef6-bd42-d4ed8dd5eb18)35 (#ulink_c9a24f4b-6cf3-5193-a17b-6011a6cbd4dd)36 (#ulink_2f8662b7-b559-5121-9d90-b0593659ab80)37 (#ulink_3729c9f3-5739-5d61-af8c-3a67e84b0621)38 (#ulink_457f570b-71c4-5d1c-b2e2-f933c77596cd)39 (#ulink_2da33ebd-99b6-5d86-bd1d-d3372c70b130)40 (#ulink_98320382-b0b2-5337-891c-2f26ef89f24b)41 (#ulink_61ceebf8-bbbf-5546-802f-1efeefc2b12a)42 (#ulink_cea7a05a-10f9-5d7d-82eb-b19bd9690a0f)43 (#ulink_d0864895-bbdf-5df4-bd9b-d7b36a750b12)44 (#ulink_3e4cc23b-7998-5de6-af46-35ae04529662)45 (#ulink_e6ca41ff-28d4-5090-b621-08ef4cb5d93a)46 (#ulink_53e4c33c-bfbd-5f54-8ff1-ba173567358c)47 (#ulink_22732a3f-a136-5823-8f24-a37560e17ca8)48 (#ulink_e1b16593-24a3-55bf-b2f5-a6bf38739633)49 (#ulink_41004633-1cc6-5875-9556-7b6e62826195)50 (#ulink_e8d08ff2-44fa-5d7d-8a23-388a55f62d39)51 (#ulink_8aa49e21-3294-5e2a-99c0-aeef9d66a40b)52 (#ulink_ef2be89a-eea8-5797-b87e-38ac182bda30)53 (#ulink_e3fd8979-4776-5b69-b0a1-d4abbd50dacc)54 (#ulink_82ac9ae7-dab1-50b2-8729-c029f4e5d918)55 (#ulink_9438b4af-5313-5bf6-9e40-3ebf02900783)56 (#ulink_5da2e98d-801a-548e-9292-81a25cdff83d)57 (#ulink_4c23598e-da6a-538e-85cb-361973a33bdd)58 (#ulink_7c3976a2-bd0d-56e0-aada-1a63487754c7)59 (#ulink_0892939c-b7f5-5e1e-9b65-dd95bbab3708)60 (#ulink_e6e16acf-c836-5b56-98aa-86477041fac5)61 (#ulink_7bad0454-8318-5524-94d7-d2ec1196edd0)62 (#ulink_2f081b7f-ecb1-5431-8d33-3d1fbd0f6b85)63 (#ulink_2d3a15b2-22f4-5b4a-b47f-4dc42bbee90c)64 (#ulink_68f2e83c-46ea-5c47-b87e-d852ff0aa308)65 (#ulink_4b814c53-bea5-5783-a0b0-0ddce8c397de)66 (#ulink_0b75521e-da2a-585d-80a5-977b8269afeb)67 (#ulink_c2722d9a-6882-520b-b94d-69ad2e54d5c1)68 (#ulink_394d886a-c1fd-5bed-9f43-e7bd1d2139e3)69 (#ulink_56618657-35b9-5215-b60e-f0ad4532cd7a)70 (#ulink_22f96d25-687a-5b92-95c0-2d4b7e1c2d91)71 (#ulink_2f6af7fb-7990-5e87-9417-35c091831b8c)72 (#ulink_ca6f78be-3f06-5ecb-ae17-fccacbdf4034)73 (#ulink_0a989216-4d6d-5501-8e5d-1ed34d876661)74 (#ulink_fc47f572-ec43-5a99-8ba9-d3e5a3dc62d5)75 (#ulink_fcd5de5b-ddc7-515a-8d9d-f3c0a53ab972)76 (#ulink_6f89e7c9-7821-520f-a314-078276acb905)77 (#ulink_49250b30-db2a-5b10-8779-c5b5ff0afa5b)78 (#ulink_0c68021a-8dd8-503f-a9fc-c9e367b0465e)79 (#ulink_a1eb771a-66c5-5658-b2ed-4c5f65706c83)80 (#ulink_0193af5f-79ce-539c-963a-0c7748a38f5f)81 (#ulink_e2a0be91-a9d6-5b0f-8d9a-9231355eea03)82 (#ulink_0b1dbc0b-72f7-56a8-ad34-8d5212663a2d)83 (#ulink_653d91e2-69df-567d-83e5-797f2f044983)84 (#ulink_f38cf843-2ac9-5f97-a5b4-3a596b69add8)85 (#ulink_cf9e3430-ae52-5b5b-860f-36283a6bebc0)86 (#ulink_e2992d5b-e298-503d-98b0-71b568c37db2)87 (#ulink_6ebfa104-63f7-52af-bdd9-a6ff99515d22)88 (#ulink_445aec0b-9cfb-5660-ad67-1ccc918950f6)89 (#ulink_9e25eaf6-2e36-5da5-a60d-f15d053895d3)90 (#ulink_6fa6fc11-b9f3-51e0-bc17-022c425f5027)91 (#ulink_a7ebbd70-9229-5ddc-a984-3f7f614fda24)92 (#ulink_53d1b8cb-6cc1-5e10-b2c9-f23cbf2333b7)93 (#ulink_7aa2c395-06bf-5ee7-84ab-31fd1c3f6193)94 (#ulink_32ff876c-9986-5c83-a6eb-cf9a8be05056)95 (#litres_trial_promo)96 (#litres_trial_promo)97 (#litres_trial_promo)98 (#litres_trial_promo)99 (#litres_trial_promo)100 (#litres_trial_promo)101 (#litres_trial_promo)102 (#litres_trial_promo)103 (#litres_trial_promo)104 (#litres_trial_promo)105 (#litres_trial_promo)106 (#litres_trial_promo)107 (#litres_trial_promo)108 (#litres_trial_promo)109 (#litres_trial_promo)110 (#litres_trial_promo)111 (#litres_trial_promo)113 (#litres_trial_promo)115 (#litres_trial_promo)116 (#litres_trial_promo)117 (#litres_trial_promo)118 (#litres_trial_promo)119 (#litres_trial_promo)120 (#litres_trial_promo)121 (#litres_trial_promo)122 (#litres_trial_promo)123 (#litres_trial_promo)124 (#litres_trial_promo)125 (#litres_trial_promo)126 (#litres_trial_promo)127 (#litres_trial_promo)128 (#litres_trial_promo)129 (#litres_trial_promo)130 (#litres_trial_promo)131 (#litres_trial_promo)132 (#litres_trial_promo)133 (#litres_trial_promo)134 (#litres_trial_promo)135 (#litres_trial_promo)136 (#litres_trial_promo)137 (#litres_trial_promo)138 (#litres_trial_promo)139 (#litres_trial_promo)140141 (#litres_trial_promo)142 (#litres_trial_promo)143 (#litres_trial_promo)144 (#litres_trial_promo)145 (#litres_trial_promo)146 (#litres_trial_promo)147 (#litres_trial_promo)148 (#litres_trial_promo)149 (#litres_trial_promo)150 (#litres_trial_promo)151 (#litres_trial_promo)152 (#litres_trial_promo)153 (#litres_trial_promo)154 (#litres_trial_promo)155 (#litres_trial_promo)156 (#litres_trial_promo)157 (#litres_trial_promo)158 (#litres_trial_promo)159 (#litres_trial_promo)160 (#litres_trial_promo)161 (#litres_trial_promo)162 (#litres_trial_promo)163 (#litres_trial_promo)164 (#litres_trial_promo)165 (#litres_trial_promo)166 (#litres_trial_promo)167 (#litres_trial_promo)168169 (#litres_trial_promo)170 (#litres_trial_promo)171 (#litres_trial_promo)172 (#litres_trial_promo)173 (#litres_trial_promo)174 (#litres_trial_promo)175 (#litres_trial_promo)176 (#litres_trial_promo)177 (#litres_trial_promo)178 (#litres_trial_promo)179 (#litres_trial_promo)180 (#litres_trial_promo)181 (#litres_trial_promo)182 (#litres_trial_promo)183 (#litres_trial_promo)184 (#litres_trial_promo)185 (#litres_trial_promo)186 (#litres_trial_promo)187 (#litres_trial_promo)188 (#litres_trial_promo)189 (#litres_trial_promo)190 (#litres_trial_promo)191 (#litres_trial_promo)192 (#litres_trial_promo)193 (#litres_trial_promo)194 (#litres_trial_promo)195 (#litres_trial_promo)196 (#litres_trial_promo)197 (#litres_trial_promo)198 (#litres_trial_promo)199 (#litres_trial_promo)200 (#litres_trial_promo)201 (#litres_trial_promo)202 (#litres_trial_promo)203 (#litres_trial_promo)204 (#litres_trial_promo)205 (#litres_trial_promo)206 (#litres_trial_promo)207 (#litres_trial_promo)208 (#litres_trial_promo)209 (#litres_trial_promo)210 (#litres_trial_promo)211 (#litres_trial_promo)212 (#litres_trial_promo)213 (#litres_trial_promo)214 (#litres_trial_promo)215 (#litres_trial_promo)216 (#litres_trial_promo)217 (#litres_trial_promo)218 (#litres_trial_promo)219 (#litres_trial_promo)220 (#litres_trial_promo)221 (#litres_trial_promo)222 (#litres_trial_promo)223 (#litres_trial_promo)224 (#litres_trial_promo)225 (#litres_trial_promo)226 (#litres_trial_promo)227 (#litres_trial_promo)228 (#litres_trial_promo)229 (#litres_trial_promo)230 (#litres_trial_promo)231 (#litres_trial_promo)232 (#litres_trial_promo)233 (#litres_trial_promo)234 (#litres_trial_promo)235 (#litres_trial_promo)236 (#litres_trial_promo)237 (#litres_trial_promo)238 (#litres_trial_promo)239 (#litres_trial_promo)240 (#litres_trial_promo)241 (#litres_trial_promo)242 (#litres_trial_promo)243 (#litres_trial_promo)244 (#litres_trial_promo)245 (#litres_trial_promo)246 (#litres_trial_promo)247 (#litres_trial_promo)248 (#litres_trial_promo)249 (#litres_trial_promo)250 (#litres_trial_promo)251 (#litres_trial_promo)252 (#litres_trial_promo)253 (#litres_trial_promo)254 (#litres_trial_promo)255 (#litres_trial_promo)256 (#litres_trial_promo)257 (#litres_trial_promo)258 (#litres_trial_promo)259 (#litres_trial_promo)260 (#litres_trial_promo)261 (#litres_trial_promo)262 (#litres_trial_promo)263 (#litres_trial_promo)264 (#litres_trial_promo)265 (#litres_trial_promo)266 (#litres_trial_promo)267 (#litres_trial_promo)268 (#litres_trial_promo)269 (#litres_trial_promo)270 (#litres_trial_promo)271 (#litres_trial_promo)272 (#litres_trial_promo)273 (#litres_trial_promo)274 (#litres_trial_promo)275 (#litres_trial_promo)276 (#litres_trial_promo)277 (#litres_trial_promo)278 (#litres_trial_promo)279 (#litres_trial_promo)280 (#litres_trial_promo)281 (#litres_trial_promo)282 (#litres_trial_promo)283 (#litres_trial_promo)284 (#litres_trial_promo)285 (#litres_trial_promo)286 (#litres_trial_promo)287 (#litres_trial_promo)288 (#litres_trial_promo)289 (#litres_trial_promo)290 (#litres_trial_promo)291 (#litres_trial_promo)292 (#litres_trial_promo)293 (#litres_trial_promo)294 (#litres_trial_promo)295 (#litres_trial_promo)296 (#litres_trial_promo)297 (#litres_trial_promo)298 (#litres_trial_promo)299 (#litres_trial_promo)300 (#litres_trial_promo)301 (#litres_trial_promo)302 (#litres_trial_promo)303 (#litres_trial_promo)304 (#litres_trial_promo)305 (#litres_trial_promo)306 (#litres_trial_promo)307 (#litres_trial_promo)308 (#litres_trial_promo)309 (#litres_trial_promo)310 (#litres_trial_promo)311 (#litres_trial_promo)312 (#litres_trial_promo)313 (#litres_trial_promo)315 (#litres_trial_promo)317 (#litres_trial_promo)318 (#litres_trial_promo)319 (#litres_trial_promo)320 (#litres_trial_promo)321 (#litres_trial_promo)322 (#litres_trial_promo)323 (#litres_trial_promo)324 (#litres_trial_promo)325 (#litres_trial_promo)326 (#litres_trial_promo)327 (#litres_trial_promo)328 (#litres_trial_promo)329 (#litres_trial_promo)330 (#litres_trial_promo)331 (#litres_trial_promo)332 (#litres_trial_promo)333 (#litres_trial_promo)334 (#litres_trial_promo)335 (#litres_trial_promo)336 (#litres_trial_promo)337 (#litres_trial_promo)338 (#litres_trial_promo)339 (#litres_trial_promo)340 (#litres_trial_promo)341 (#litres_trial_promo)342 (#litres_trial_promo)343 (#litres_trial_promo)344 (#litres_trial_promo)345 (#litres_trial_promo)346 (#litres_trial_promo)347 (#litres_trial_promo)348 (#litres_trial_promo)349 (#litres_trial_promo)350 (#litres_trial_promo)351 (#litres_trial_promo)352 (#litres_trial_promo)353 (#litres_trial_promo)354 (#litres_trial_promo)355 (#litres_trial_promo)356 (#litres_trial_promo)357 (#litres_trial_promo)358 (#litres_trial_promo)359 (#litres_trial_promo)360 (#litres_trial_promo)361 (#litres_trial_promo)362 (#litres_trial_promo)363 (#litres_trial_promo)364 (#litres_trial_promo)365 (#litres_trial_promo)366 (#litres_trial_promo)367 (#litres_trial_promo)368 (#litres_trial_promo)369 (#litres_trial_promo)370 (#litres_trial_promo)371372 (#litres_trial_promo)373 (#litres_trial_promo)374 (#litres_trial_promo)375 (#litres_trial_promo)376 (#litres_trial_promo)377 (#litres_trial_promo)378 (#litres_trial_promo)379 (#litres_trial_promo)380 (#litres_trial_promo)381 (#litres_trial_promo)382 (#litres_trial_promo)383 (#litres_trial_promo)384385 (#litres_trial_promo)386 (#litres_trial_promo)387 (#litres_trial_promo)388 (#litres_trial_promo)389 (#litres_trial_promo)390 (#litres_trial_promo)391 (#litres_trial_promo)392 (#litres_trial_promo)393 (#litres_trial_promo)394 (#litres_trial_promo)395 (#litres_trial_promo)396 (#litres_trial_promo)397 (#litres_trial_promo)ii (#litres_trial_promo)

Prologue (#uf192a6ac-418b-5fc5-bf50-b19d2d1196fb)

In which I answer the questions in the way I choose …

JH: Good morning. It’s ten past eight and I’m John Humphrys. With me live in the studio is … John Humphrys. It’s just been announced that he’s finally decided to leave Today after thirty-three years. Mr Humphrys, why leave it so long?

JH: Well, as you said it’s been thirty-three years and that’s—

JH: I know how long it’s been … far too long for the taste of many listeners, some might say. It’s because your style of interviewing has long passed its sell-by date, isn’t it?

JH: Well I suppose some people might say that but—

JH: You suppose some people might say that? Is it true or not?

JH: I’m not sure it’s really up to me to pass judgement on that because—

JH: What d’you mean you’re ‘not sure’! You either have a view on it or you don’t.

JH: Well I do but you keep interrupting me and—

JH: Ha! I keep interrupting you! That’s a bit rich. Isn’t that exactly what you’ve been doing to your guests on this programme for the past thirty-three years and isn’t that one of the reasons why the audience has finally had enough of you … not to mention your own bosses?

JH: I really don’t think that’s fair. After all it was only politicians I ever interrupted and only then if they weren’t answering the question.

JH: You mean if they didn’t answer YOUR questions in the way YOU chose—

JH: Again that’s not fair because—

JH: Are you seriously suggesting that you didn’t approach every political interview with your own views and if the politician didn’t happen to share those views they were toast? You did your best to cut them off at the knees.

JH: That’s nonsense. The job of the interviewer is to act as devil’s advocate … to test the politician’s argument and—

JH: And to make them look like fools and to make you look clever. It’s just an ego trip, isn’t it?

JH: No … and if that were really the case the politician would refuse to appear on Today. And mostly they don’t—

JH: Ah! You say ‘mostly’, which is a weasel word if ever I heard one. Isn’t it the case that when they do refuse it’s because they know you will deny them the chance to get their message across because all you want is a shouting match?

JH: Not at all. They’re a pretty robust bunch and I’d like to think they hide from the live microphone because they don’t want to be faced with questions that might very well embarrass them if they answer frankly and honestly.

JH: I’m sure that’s what you’d like to think but the facts suggest otherwise don’t they? And when they do try to answer frankly, you either snort with disbelief or try to ridicule them.

JH: Look, I wouldn’t deny that I get frustrated when the politician is simply refusing to answer the question, and I’m sure the listeners feel the same. It’s my job to ask the questions they want answered and if the politician refuses to engage or pulls the ‘I think what people really want to know …’ trick, then it’s true that occasionally I do let my irritation show.

JH: Nonsense! The fact is you have often been downright rude and that is simply not acceptable.

JH: Well … we agree on something at last! You’re absolutely right when you say being rude is unacceptable and I admit that I’ve been guilty of it – but not often. In my own defence I can think of only a tiny number of occasions when it’s happened and I regret it enormously – not least because it really does upset the audience. One of the biggest postbags I’ve ever had (in the days before email which shows you how long ago it happened) was for an interview in which I really did lose my temper. The audience ripped me apart afterwards and they were quite right to do so. If we invite people onto the programme we have to treat them in a civilised manner.

JH: So we’ve established that you’re not some saintly figure who always occupies the moral high ground. I suppose that’s a concession of sorts. But what I’m accusing you of goes much wider than that. Of course you have a responsibility to the audience and to the interviewee but you also have a wider responsibility. Let me suggest that when people like you treat politicians with contempt you invite us, the listeners, to do the same. And that’s bad for the whole democratic process.

JH: Once again, I agree with you. Not that we treat them with contempt, but that programmes like Today might contribute to the growing cynicism society has for politicians and the whole political process. But which would you prefer: a society in which politicians are regarded with awe and deference, or a society in which they are publicly held to account for their actions by people like me who question them when things go wrong or when we suspect they might be misleading us?

JH: Not for me to say: I’m the one who’s asking the questions this time remember! But what I’m asking you to deal with is a rather different accusation. If people like you, who’ve never been elected to so much as a seat on the local parish council, don’t show any respect to the people the nation has elected to run the country … why should anyone else?

JH: But that’s not what I’m saying. Quite the opposite. I can’t speak for my colleagues, but I have huge respect for the men and women who choose to go into politics. I hate the idea that for so many people politics has become a dirty word. Henry Kissinger once said ninety per cent of politicians give the other ten per cent a bad reputation. The wonderful American comedian Lily Tomlin put it like this: ‘Ninety-eight per cent of the adults in this country are decent, hard-working, honest Americans. It’s the other lousy two per cent who get all the publicity. But then – we elected them.’ Yes, that’s funny, but it’s wrong. One of the greatest broadcasters of the last century, Edward R. Murrow, got closer to it when he chastised politicians who complained that broadcasters had turned politics into a circus. He said the circus was already there and all the broadcasters had done was show the people that not all the performers were well trained.

JH: In other words you regard political interviewing as a branch of showbiz rather than your high-flown pretension to be serving democracy!

JH: Look, I’m not going to pretend that we don’t want our listeners to keep listening and if that means we want to make the interviews entertaining as well as informative I’m not going to apologise for that. After all, the BBC’s founder Lord Reith said nearly a century ago that its purpose was to ‘inform, educate and entertain’. But you’ll note that he made ‘entertain’ the last in that list. Ask yourself: what’s the point of doing long, worthy and boring interviews if nobody is listening?

JH: Ah … so now we get to the nub of it don’t we? It’s all about ratings!

JH: Of course it’s not ‘all about ratings’ but obviously they matter …

JH: … because the higher they are the more you can get away with charging the BBC a king’s ransom to present the programme!

JH: Ah … I wondered how long it would take you to get onto this because—

JH: I trust you’re not going to deny that you’ve been paid outrageous sums of money over the years for sitting in a comfy studio asking a few questions when somebody else has probably briefed you up to the eyeballs anyway?

JH: That’s not entirely fair is it? You know perfectly well I spent years as a reporter and foreign correspondent in some very dangerous parts of the world. And anyway are you really saying the amount a presenter gets paid shouldn’t be related to the size of his or her audience? That’s rubbish!

JH: Ooh … touchy aren’t we when it comes to your own greed! Have you forgotten it’s the licence payer who foots the bill and the vast majority of them earn a tiny percentage of what you take home?

JH: Yes, I am a bit touchy on this subject and that’s partly because for various reasons I got a bit of a bum rap when BBC salaries were first disclosed back in the summer of 2017. And anyway I volunteered several pay cuts as you well know …

JH: Yes yes yes … we all know you’re a saint but I’m afraid we’ve run out of time. John Humphrys … thank you.

JH: And thank you too. And now I’m going to tell my own story without all those impertinent questions …

PART 1

Yesterday and Today (#uf192a6ac-418b-5fc5-bf50-b19d2d1196fb)

1

A childhood of smells (#uf192a6ac-418b-5fc5-bf50-b19d2d1196fb)

By the time I joined Today in 1987 I had been a journalist of one sort or another for thirty years and I’d been exposed to pretty much everything our trade had to offer. I had been a magazine editor at the age of fourteen – though whether the (free) Trinity Youth Club Monthly Journal with its circulation reaching into the dozens properly qualifies as a magazine is, I’d be the first to admit, debatable. I’d had the most menial job a tiny local weekly newspaper could throw at a pimply fifteen-year-old – and that’s not just the bottom rung of the ladder: it’s subterranean.

At the other end of the scale I had written the main comment column for the Sunday Times, the biggest-selling ‘quality’ newspaper in the land, for nearly five years. I’d had the glamour of reporting from all over the world as a BBC foreign correspondent – not that it seems very glamorous when you’re actually doing it. I’d had the even greater (perceived) glamour of being the newsreader on the BBC’s most prestigious television news programme.

And I had reported on many of the biggest stories in the world: from wars to earthquakes to famines. I’d seen the president of the United States forced out of office and the ultimate collapse of apartheid. I’d seen the birth of new nations and the destruction of old ones. So on the face of it I had done it all. But, of course, none of it properly equipped me for the biggest challenge in broadcast journalism: the Today programme.

Presenting a live radio news programme for three hours a day, day in and day out, is bound to test any journalist’s basic skills, not to mention their stamina. You need to know enough about what’s going on in the world to write decent links and ask sensible questions. You need enough confidence to be able to deal with unexpected crises.

You need the stamina to get up in the middle of the night and be at your best when people doing normal jobs are just finishing their breakfast and wondering what the day holds in store. And you need to be able to do all that with the minimum of preparation. Sometimes no preparation at all.

But thirty-odd years of trying to do it tells me you need something else. You need to know who you are and what you can offer to a vast audience that’s better than – or at least different from – your many rivals. My problem when I started was that I had no idea what I was offering. I had done so many different things I wasn’t at all sure who or what I was.

Was I a reporter?

I’d like to think so. Reporting is, by a mile, the most important job in journalism. Without detached and honest reporting there is no news – just gossip. At the heart of any democracy is access to information. If people don’t know what is happening they cannot reach an informed decision. I like to think I did the job well enough. I had plenty of lucky breaks and even won a few awards. But I was never as brave as John Simpson or as dedicated as Martin Bell and I never had the writing skills of a James Cameron or Ann Leslie. I did not consider myself a great reporter and knew I never would be.

Was I a commentator?

Positively not. Columnists may not be as important as reporters, but they matter. The best not only offer the reader their own well-informed views on what is happening in the world, they cause them to question their own assumptions. They make the reader think in a different way. I very much doubt that I managed that.

Was I a newsreader?

Well, again, I was perfectly capable of sitting in front of a television camera and reading from an autocue without making too many mistakes. Not, you would accept, journalism’s equivalent of scaling Everest without oxygen. Whether I had the gravitas to command the attention and respect of the audience is another matter altogether. Probably the greatest news anchorman in the history of television news was Walter Cronkite, who presented the CBS Evening News in the United States for nineteen years when it was at its peak in the 1960s and 70s. Cronkite not only had enormous presence and authority, he had a relationship with the viewers that any broadcaster would kill for. It can be summed up in one word. Trust. He was named in one opinion poll after another as the most trusted man in America. He also happened to be a deeply modest and decent man.

As for me, back in 1987, I was just a here-today-gone-tomorrow newsreader who was about to become a presenter of the Today programme and who had not the first idea what he had to offer its enormous audience. I tried asking various editors who had worked over the years with some of the great presenters what I needed to do to make my mark or, at the very least, survive. Most of them gave me pretty much the same answer: be yourself.

As advice goes, that was about as much use as telling me to write a great novel or run a four-minute mile. How can you ‘be yourself’ if you don’t know who or what you are? How can you impose your personality on the programme if you’re not quite sure what it is? It’s not as if you can pop out and buy one off the peg.

‘Good morning, I’m looking for a radio personality.’

‘Certainly sir, anything specific in mind?’

‘Well, it’s for Radio 4 so nothing too flash. Obviously I need to be trusted by the listeners and I suppose it would help if they liked me.’

‘Of course sir, wouldn’t want them gagging on their cornflakes every time they heard your voice would we? But when you say “liked” do you have anyone in mind? Dear old Terry Wogan maybe? Or a bit more on the cutting edge, if I may be so bold? Perhaps a touch of the Chris Evans? It’s always a little tricky designing a personality if the customer doesn’t have a specific style in mind.’

‘Yes, I can see that. How about the trust factor then?’

‘Just as tricky as likeability in a way, sir. Takes rather a long time to earn trust.’

‘Of course … So what about “authority”?’

‘Sorry to be so negative sir, but that doesn’t come easy either. Bit like trust in a way … takes time and depends on your track record.’

‘Hmm … I think what you’re telling me is that you don’t actually have anything in stock that would give me a Today programme personality eh?’

‘I’m afraid so. Perhaps I could offer sir a suggestion?’

‘Please!’

‘Why not stick with what you’ve got and then pop back in … shall we say … five years or so and we’ll see whether it needs a little adjustment?’

‘Thank you … most kind of you.’

‘Not at all sir … is fifty guineas acceptable …?’

Had such a shop existed in the real world I might very well have popped back – not after five years but more likely after a week. Because I learned something very quickly, and it’s this: a curious thing happens when you present a live radio programme such as Today for several hours on end, mostly without a script or without any questions written down. You discover that you have no choice but to ‘be yourself’. There is so much pressure that there is no time to adopt somebody else’s persona or even to think about creating a new one for yourself. And that can be a blessing and a curse. In my case it is both.

Those of us who practise daily journalism need to be able to write to a deadline. You either master that skill or you find another way of making a living, and I can make the proud boast that I have never missed a deadline. Very impressive, you might say, given how long I’ve been practising this trade and how many deadlines I have faced. You might be rather less impressed if I reproduced here some of the rubbish I have written over the years as the clock ticks down – but that’s another matter altogether. The rule is: never mind the quality … get it done and get it done NOW!

I’ve lost track of the number of times the 8.10 story on Today has suddenly changed and another story has taken its place, meaning that I’ve had only three or four minutes to write the introduction. In the pre-computer days it meant hammering away at the typewriter in the newsroom, ripping it out of the rollers as the clock ticked down and then running like hell into the studio with it. That, by the way, is always a mistake. I learned the hard way that you might save five seconds if you run to the studio, but when you drop into your seat in front of the microphone you will be unable to speak for the next thirty seconds because you are out of breath. And you will sound very silly.

I like to think I had a pretty rigid routine when I was presenting Today. I would skim the newspapers in the back of the car that picked me up at about 3.45 a.m. so that by the time we got to New Broadcasting House I had a rough idea of what was going on in the world. Then I would log on to my computer, heap praise on the overnight editor for the invariably wonderful programme he had put together (or not as the case may be) and would set about writing my introductions – or ‘cues’ as we call them. Then I had my breakfast sitting at my desk – a bowl of uncooked porridge oats, banana and yoghurt – while I started to think of the questions I’d be asking my interviewees over the next three hours. So by the time I got into the studio, I had lots of questions written down just waiting to be asked.

In my dreams.

Look, I KNOW it made sense to do just that. I KNOW I should have done what most of my colleagues did, which was read the briefs that had been so painstakingly prepared by the producers the day before and had the structure of the interview written down with some questions just in case the brain went blank at a crucial moment. Something which, I promise you, happened more often than you might think. So why didn’t I do it? God knows. I always ended up finding another dozen things to do that seemed infinitely more important at the time but never were.

It meant that at some point in the programme I would realise that I hadn’t the first idea what vitally important subject it was that I was meant to be addressing with the rather anxious person who had just been brought into the studio. Every morning I promised myself I would be more disciplined in future and every morning I failed. I tried to justify my idiotic behaviour by telling myself that interviews are better if you have no questions written down. After all, we wanted our audience to feel they are listening to a spontaneous conversation rather than to some automaton reading from a list of prepared questions. But there was a balance to be struck and I invariably erred on the side of telling myself it would be alright on the night – even when there was a tiny warning light flashing in my brain telling me I might be about to make a fool of myself.

I remember one torrid morning when everything that could go wrong did go wrong. The radio car broke down en route to the interviewee. The person who was meant to be operating the studio for the guest in some remote local radio station had a ropy alarm clock that had failed to go off so he never turned up. The politician who was meant to be coming into Broadcasting House had changed his mind at the last minute. The stand-by reports prepared for just such an emergency had all been used. We were on our last tape. About the only things that didn’t go wrong were the microphones in the studio, but that wasn’t much consolation because at approximately fourteen minutes to nine we had no one left to interview.

And then, just as I was planning to fall off my chair clutching my chest, thus leaving it to the other presenter to deal with the crisis and being able to blame him if he failed, my producer shrieked into my headphones. There were approximately five seconds to go before the report we were broadcasting reached its end – just time enough for him to tell me: ‘We’ve got the leader of the Indian opposition on the line and—’

And that was all he had time to say because then my microphone was live and I was broadcasting to the nation. In theory. Instead I was left to ponder not only what the name of the Indian opposition leader on the other end of the line might be but what might have happened on the subcontinent to cause my colleagues in the newsroom to set him up for a live interview. In short, I had not the faintest idea who he was nor why I was interviewing him. In the milliseconds available I ran through the options short of staging that mock heart attack.

There were only two. I could play for time and say something like: ‘Good morning sir and many thanks for joining us. May I say what an honour it is that you have given up your valuable time to join us this morning on such an auspicious day for your great country …’

A fairly uncharacteristic approach to a politician on Today I grant you, but the strength of it was that if I said it sufficiently slowly it would give my producer a vital few seconds during which he might just possibly be able to tell me why the hell I was talking to whatever-his-name-was. The weakness of the plan was that maybe nothing auspicious had happened and the mystery guest in New Delhi would decide he was dealing with a raving lunatic in London and hang up.

So I went for the opposite approach, gambled that we tend to interview foreign opposition leaders only when they are out to make trouble for their country’s government, and tried this:

‘Many thanks for joining us … it seems the government is facing a pretty serious crisis eh …?’

And then I prayed. If there was no crisis I was toast. It was a fifty-fifty gamble and luck was with me.

‘Yes indeed …’ he began. And that was enough. The opposition politician who ducks the chance of taking a swipe at his government has yet to be born and he was away. The rest of the interview was child’s play.

That sort of thing happens all the time on Today. Scarcely a day goes by without a presenter having to go off-piste for one reason or another. It comes with the territory and, obviously, any live radio presenter who can’t think on their feet would be much better getting a rather less stressful job. Rudyard Kipling wrote a pretty good job spec for Today in the first verse of his poem ‘If’:

If you can keep your head when all about you

Are losing theirs and blaming it on you;

If you can trust yourself when all men doubt you,

But make allowance for their doubting too;

If you can wait and not be tired by waiting,

Or being lied about, don’t deal in lies,

Or being hated, don’t give way to hating …

I especially like the line about not dealing in lies – can’t imagine why it puts me in mind of certain politicians – but I’m not so sure about ‘being hated’ and ‘giving way to hating’. It raises the tricky question of how much presenters should worry about the way they are perceived by the listener and takes me back to my search for a ‘radio personality’. Presumably if you are a so-called ‘shock jock’ anchorman of the sort they seem to specialise in on the other side of the Atlantic, being hated by a large chunk of your audience is an essential qualification. Perhaps not so much for a Today presenter. But is the opposite true in the more civilised world of Radio 4? Is it important to be liked by the listener? I’ve never been quite sure about that. I like to think that so long as you’re doing your job reasonably competently you will be tolerated. Well … up to a point. Sometimes you get just a tiny hint that not everyone loves you. I got more than a hint from the broadcasting critic on the Observer one Sunday morning. He wrote that if he ever found himself sitting next to me at a dinner party he would probably drive a fork through my hand.

So I turned to some fan mail to cheer myself up and there was this:

Dear John,

Some people ask me what I live for. Well I tell them that I live for the day when Mother Nature finally takes the old codger that you are out and releases the rest of us of suffering your miserable existence. For the sake of humanity, may you rest in peace, and the sooner the better. When you are finally dead heaven will descend on earth and disease, starvation, inequality and suffering will all be things of the past and there will be much merriment and rejoicing in every corner of the globe.

Thank you

It’s the polite ‘Thank you’ at the end of that letter that I cling on to. And I suppose it’s nice that someone out there thinks I have it in my power to make the world a better place – albeit by dying.

The overriding priority of BBC news is to deliver information and try to analyse what it means – but there’s no point in doing a brilliant interview if nobody is listening. Getting the balance right is never easy compared with, say, a Radio 2 show where entertainment is what matters. Someone like Terry Wogan knew exactly what buttons to press. He presented himself as a loveable old Irishman with an endless supply of easy-going charm. His gentle, self-deprecating sense of humour hid a quick wit and a sharp mind but what mattered above all else was that the audience liked him. His vast army of TOGs (‘Terry’s Old Geezers or Gals’) were invited to believe that he was just like them really: just one big happy family. The genius of his radio persona was that the audience could imagine sharing a glass of Guinness with him, enjoying a chat and probably agreeing about pretty much everything. In truth Terry was a complicated man tortured by the same demons that afflict most of us, but that’s not what the adoring listeners heard.

Of course Today presenters want to be liked – don’t we all? – but life is not like that. And certainly not in the world of journalism. One small test of my own humanity (if not necessarily likeability) came on a morning when I was scheduled to interview a senior political figure about the war in Iraq. She was in our radio car rather than in the studio so I’d had no chance of a quick chat in the green room before the interview. If I had, we’d have aborted it there and then. Within roughly thirty seconds of going live I realised she was drunk. It was 7.20 in the morning. The listeners might have thought she sounded a bit slurred but would probably have assumed she’d just got out of bed or was maybe a bit hungover. I knew her well enough to know the truth and that she was capable of saying anything. I pretended there was a problem with the radio-car connection and ended the interview very quickly.

Was that the right thing to do? Certainly not if I were being strictly faithful to the (unwritten) journalists’ code. I should have exposed her frailty and allowed the audience and her political masters to reach their own judgement. It would have almost certainly finished her career. But I liked her and respected her both as a politician and as a human being. I might have asked myself in those few seconds whether the world of politics would have been better off without her and concluded it would not – but I probably didn’t. The fact is, I acted on instinct and I agonise about it still – as I do with another similar interview for slightly different reasons.

This happened at a party conference in the late 1980s. The difference is that it was a pre-recorded interview with a prominent Northern Ireland minister late one evening for use the following morning. Party conferences don’t have too much in common with Methodist temperance meetings. There are many parties and receptions and a great deal of drink is taken. The minister had taken too much. Far too much. He or his advisers should have refused to do the interview but they didn’t.

What he said was pretty incendiary and would almost certainly have had a seriously damaging effect on the peace process, which was going through a tricky time. Should we run it? I talked about it at some length with my editor and in the end we decided not to. Again it was not an easy decision. It might well have made headlines the next day, but what’s a headline in the context of a vicious conflict that killed and injured many thousands of people?

All of which makes me appear as a saintly soul whose only wish is to make this world a better place. The reality is that self-interest played a pretty large part in my calculations too. Experience told me that presenters tend to win more brownie points with the listeners if they are not seen to be behaving like total thugs. I’d had a taste of how much the good Today listeners disapprove of such behaviour following an interview with John Hume I did in my early years on the programme.

At the time he was the leader of the Social Democratic Party in Northern Ireland, a formidable and brave politician who went on to win the Nobel Peace Prize. And I was rude to him. I interrupted for no good reason, told him he wasn’t answering the questions without giving him a chance to do so and generally behaved like a pub bore after one pint too many. Those were the days before emails when the postman arrived with the mail in a sack. The day after the Hume interview there were several sacks dumped in the Today office – almost all filled with letters from angry listeners. I survived – only just – and I’d like to think that I learned a lot from that ghastly interview. But that’s for others to judge.

I suggested earlier that I had a problem deciding on my ‘radio personality’ – assuming it existed outside my own imagination.

What I did not decide on my first morning in the Today studio was that I would set out to be the stroppiest Welshman on the airwaves. And, contrary to popular assumptions, I do not set out when I interview someone to have an argument – even if it’s with a politician. But I cannot deny that I enjoy arguing. Nor would I deny that I approach people in power – all of them – with a pretty strong dose of scepticism. Whether that is a good thing or a bad thing is for others to judge, but either way it’s not my fault. And I have that on pretty good authority. Aristotle is quoted as having said: ‘Give me a child until he is seven and I will show you the man.’ If he was right it must surely mean that our parents are bound to have a profound influence on us – one way or another.

A few years ago one of our leading universities offered me the chance to become ‘Professor’ Humphrys: a very tempting prospect for a grammar-school boy whose single academic achievement had been a handful of O levels. I even managed to fail woodwork. My father never quite forgave me for that. I accepted the university’s offer immediately but imposed one condition: I would close down the department in my first week. The offer was withdrawn. The department was (what else?) media studies.

Maybe my response had been a bit childish and maybe I’m wrong about the value of a media studies degree. I’m sure that many bright young people have left university with them and gone on to great things. I’m equally sure that they would have succeeded without a media studies degree. I simply do not believe that you can learn to be a journalist. I’m with that late, great reporter Nicholas Tomalin who said the only qualities essential for success as a journalist are rat-like cunning, a plausible manner and a little literary ability. Tomalin wrote in a pre-digital age and he would have been forced to add to that list today the ability to understand and navigate the world of social media. I would add insatiable curiosity, and something else: a good journalist needs, in my book, to be contumacious.

Not a word, I concede, that one hears every day but it’s been around a long time and apparently we have St Benedict to thank for it. He applied it to people who ‘stubbornly or wilfully resist authority’. The punishment for it 1,500 years ago was excommunication – which is fair enough I suppose if you are in the business of founding the greatest monastery in history. You can’t have monks calling into question the supreme authority of the Catholic Church, can you? Equally, in my rather more humble view, you can’t have journalists who do the opposite: who accept supreme authority without questioning it. Or any other kind of authority for that matter. And that is not something you can learn. You are either contumacious or you are not. I am, and I have my father, George, to thank. Or to blame.

He was born into a working-class family in Cardiff in what we would now call a slum but was pretty standard housing for people like them in the early years of the last century: a tiny back-to-back terraced house with an outdoor lavatory and a tin bath in front of the fire. He was, by all accounts, a bright and rather wilful child who loved reading and running. But his disobedience was to cost him his eyesight.

Like most youngsters in those pre-vaccine days he caught measles – a particularly bad dose – and my grandmother was told that on no account was she to let him out of the house. He was to be kept in a bedroom with the curtains drawn. The next day she had to go shopping, leaving him in the house alone with strict orders to stay put. Obviously he didn’t. It was a glorious winter’s day – bright sunshine after some heavy snowfalls – and there were snowballs to be thrown and snowmen to be built. The temptation was too great for him. The sun reflected off the snow and that, coupled with the poor nutrition common in working-class families at that time, did massive damage to his optic nerve. For the next couple of years he was blind. His education effectively ended when he was twelve.

Gradually his sight began to recover enough for him to get an apprenticeship and he became a French polisher. He got a job with the firm where he’d served his apprenticeship and, confident of a steady income, promptly proposed to my mother. She accepted. The job lasted barely a week. My father took great exception to something the foreman had said to him, punched him on the nose and he was out on his ear. The dole was not an option – he was far too proud to take what he called ‘charity’ anyway – so he set about building up his own business.

There were always people in the richer parts of Cardiff who wanted a table or a piano polished and, one way and another, he made enough money to keep hearth and home together – with my mother doing the neighbours’ hair in the kitchen and me doing a paper round before school and my older brother making deliveries for the local grocer. We also tramped the streets of the posher suburbs sticking little circulars through letter boxes advertising Dad’s services. I’ve never been sure if it was worth the effort but at least it gave me an idea of how the other half lived.

Obviously we didn’t get paid for it but there was some compensation. I carried two bags – one for the leaflets and the other for any apples hanging temptingly near the garden walls. It’s always puzzled me that my friends and I would not have dreamed of stealing apples from a shop but I think we must have seen scrumping as a victimless crime. And anyway there were always far more apples than the posh people could possibly eat. Or so we reasoned. I also made a modest income from our own neighbours: selling them little bundles of mint door to door which I picked from the backyard where it grew in the ashes thrown out from the coal fires. Twopence for a small bunch: an extra penny for a bigger one. I always sold out. That was where my entrepreneurial career began and ended.

We were told endlessly what was wrong and what was right, and not just by our parents. For those of us who went to Sunday school, the vicar reinforced the message. There was a clear line of authority running through our tight little community, with the vicar and perhaps also the GP at the top. Perhaps it was a small-scale reflection of the wider world, in an age when we deferred to figures in authority, when elites told us what our responsibilities were.

My father had an abiding dislike and distrust of the clergy mostly, I think, because they thought they were a cut above ordinary people like him. That can probably be traced to an experience he had as a young man when he was staying with his aunt at her little cottage in a Somerset village, not long after the First World War. They were about to sit down for lunch when the door burst open and the vicar strode in. Without so much as a by-your-leave or a ‘Good morning’ he demanded to know why my great-aunt had not been at the morning service. She did a little bob and stammered an apology. She tried to explain that she seldom had visitors and that she’d been preparing lunch for her nephew whom she hadn’t seen for a year and who had come from a long way away. She said she would be sure to turn up for evensong. He was having none of it. He did not even glance at my father but barked at his auntie: ‘See that you do and don’t let it happen again!’ Then he turned on his heel and left.

Instinctive deference – unearned deference – is dying if not dead. Its defenders say it has taken respect with it but I doubt that. Over the years I have received countless letters (invariably letters) blaming me and my ilk but I suspect we were reacting to, rather than creating, a change in attitudes to authority. Richard Hoggart, who was one of Britain’s most respected cultural critics, thought that attitudes to authority, whether religious or lay, really began to change at the end of the last war – when the soldiers came home and the women, who’d been forced to work in the factories, decided they didn’t want to go back to the old ways.

I behaved according to the rules of my community when I was growing up, but I think (perhaps thanks to my father) it instilled in me not just deference to authority but a questioning attitude to it too. I don’t like being defined or told what to do, whoever is in charge. I even have a thing about wearing identity tags at work. Once, during the Gulf War, when BBC security was at its tightest, I was rushing to the studio with a few minutes to spare and a man in a peaked cap stopped me at the door.

‘You can’t go in there,’ he told me sternly.

‘Why not?’

‘Because you’re not wearing your ID.’

‘But you know who I am and I’m on air in two minutes.’

‘Sorry. No ID, no admission.’

‘OK,’ I said, ‘you do the bloody programme.’

Mercifully, he gave in. Yes, I know I was being petulant and he was just doing his job but I thought at the time I was striking a small blow for freedom. Today, I suspect I was just being difficult because I don’t like authority.

Mine was a childhood of smells: the horrible smell of the chemical Mam used for perms and the even more horrible (and probably dangerous) fumes from the chemicals Dad used when he had to polish furniture in the kitchen – which was often. One of the tricks of his trade – I was never quite sure why – was to pour methylated spirits onto, say, a tabletop, wait a few seconds and then set fire to it. There’d be a great ‘whoosh!’ Job done. Remember … this was in the kitchen where my mother cooked and the family ate. Even worse, because it was so noxious, was his use of oxalic acid. The crystals were boiled up in a baked beans tin on the gas stove and the liquid used as a very powerful bleach if he needed to lighten the colour of a particular piece of furniture. The fumes got into the back of your throat. God knows what they did to your lungs. My mother suffered the most and died a relatively early death. The doctor said her lungs ‘just gave out’. Unsurprising really.

Dad would have had an easier life had he been a bit less stroppy. He hated ‘snobs’ – a word that encompassed a vast range of people – and he hated authority in all its manifestations. Almost all. There was one exception. He did a lot of work at Cardiff and Port Talbot docks polishing the officers’ quarters on the banana boats and iron-ore carriers. I sometimes worked with him as an (unpaid) labourer and was always surprised to see how he treated the captain. He even called him ‘sir’. That was a word I’d never heard him use.

His politics were perfectly balanced. He hated capitalism – specifically those who got rich from it – and inherited wealth. And he hated socialism. When he turned up at a really grand house to do some work he would always ring the bell at the main entrance, and if he was ordered to use the servants’ entrance – which happened from time to time – he would tell them to bugger off and walk away. He was, as he unfailingly pointed out, a skilled craftsman. He was absolutely NOT a ‘servant’. The fact that he needed the work took second place to his pride.

He had a special place in hell reserved for the bosses of large companies, specifically the ship owners and the banks, who hired him to do a job and did not pay him for at least a couple of months. I decided long ago that when I become prime minister the first law I shall propose will be one that forces all companies to pay their bills within one month – except in the case of one-man firms like my father’s in which case it will be one week. Why not?

Dad hated royalty too. He was the only person in our street who did not go to see the Queen when she visited Cardiff soon after her coronation, even though her motorcade passed down a road only a few minutes’ walk from our house. ‘Why should I?’ he’d demand. ‘She’s just another human being … she’s no better than me.’ He was thrown out of his club because of her. It was a busy Friday night and the only spare seat was beneath a portrait of her. ‘Buggered if I’m sitting there!’ he announced. And that was the end of his club membership. He hated socialism equally. He regarded trade union leaders as dangerous and their members as dupes. The welfare state was an excuse for lazy men to live off hard-working men like him. He made an exception for women who had lost their husbands in the war or were struggling desperately to bring up their children. The Man from the Board, with his large notebook, intrusive questions and prying eyes, was hated by everyone in our street. If you applied for benefits you had to prove your need. One of our neighbours, who’d been widowed and was struggling desperately to bring up her two children, told my mother how he had demanded to know why she had four chairs around her kitchen table when there were only three in her family, her husband having died in the war. The Man from the Board said it would count against her when ‘the office’ reached a judgement on her case. Obviously my father hated him too.

The curious thing was that Dad never admitted we were poor – even when there was no work and we were really on our uppers. I remember one night – I was probably seven or eight – being woken up by him screaming when he should have been snoring. My brother told me he was having a nervous breakdown – not that he really knew what that meant. I understood much later that he was at breaking point because he didn’t know how he was going to put enough food on the table for all of us. I think what I understand now is that he regarded himself as a failure and that was more than he could handle.

In fact, we kids never really went hungry. We knew when times were hard because there would be lamb bones boiled for a very long time with potatoes and onions for dinner (meaning lunch) and sugar sandwiches for tea (meaning supper). In better times meals were strictly regimented. I can remember exactly what we had for dinner every day of the week. It almost never varied and it gave me my unshakeable conviction that the cheapest meat is the tastiest.

Scrag-end of lamb neck made the perfect stew, and point end of brisket the perfect roast – so long as you left it in the oven for about six hours. It was at least seventy per cent fat but that was fine because my father preferred fat to lean meat – especially when it was burned to a crisp. I can’t imagine it was terribly healthy food, but he made up for it by drinking the water the cabbage had been boiled in. And, yes, it was just as disgusting as it sounds.

Tea was slightly more flexible, especially in summer when the allotment was producing lots of lettuce and other salad ingredients. Funny how the middle class came to discover the joy of allotments for themselves in later years. Unlike the working class who grew the food because they needed it, the middle class grew it for the pleasure of it. Nothing was wasted in our house. I mean nothing. Stale bread was soaked in water and used to make bread pudding and, on the vanishingly rare occasion when one of us left some food on our plate for dinner it would be served up again for tea. Obviously there was no fridge, but that didn’t matter because nothing stayed around for long enough to go rotten. On hot days the milk stood in a saucepan of cold water. It worked.

My father’s nervous breakdown did not last long. He was not a man to show emotion of any kind. In the language of the time he ‘pulled himself together’ – almost as though his breakdown had been a fault in his character. I’m not sure the word ‘counselling’ existed in those days, possibly because there were so many men who had survived the war but were still suffering from what we would now call post-traumatic stress disorder. We had no language for PTSD then.

My favourite uncle, Tom, had fought in the Great War and was still suffering horribly. He had been gassed in the trenches, shipped back to Britain and put to work in the docks. Unbelievably, given the state of his lungs, his job was offloading coal. The coal dust completed the job that the gas had begun. His lungs were wrecked. He was never again able to lie down to sleep because his lungs would fill with fluid. His life had been hellish enough anyway.

He and Auntie Lizzie had one child, Tommy – or ‘Little Tommy’ as everyone called him even though he was a very large man. His brain and his face had been terribly damaged at birth and he had the mental age of a toddler and no speech. In fact, he had nothing – except an unlimited supply of love from his utterly wonderful parents. Whenever I went to his house Little Tommy would bring out the photograph albums and point gleefully at every picture of me and my siblings and parents and look terribly proud of himself for having made the connection. Then he would laugh uproariously.

Uncle Tommy and Auntie Lizzie had a hard life by even the harshest of standards. Desperate would be a better word. Their one constant worry was what would happen to Little Tommy ‘when we are gone’. But I never once heard them complain. Yes, I know that’s one of the oldest clichés in the book but so what? It happens to be true. Whether their lives might have been improved if they had complained we shall never know.

My father’s proudest possession was a medallion he won representing Glamorgan on the running track. He carried it with him in his jacket pocket everywhere. He was a first-class sprinter but two things held him back: his eyesight and his poverty. It’s not easy to race if you can’t see the man in front of you clearly. A friend of his told me how Dad once ran off the course and into a barbed-wire fence alongside the track. He kept going. He always did. But poverty proved to be a bigger problem. He had been selected to run for his athletics club in a meet some fifty miles from Cardiff. He had no money and so the club paid his bus fare for him. But those were the days when athletics was a strictly amateur sport and when the Amateur Athletics Association got to hear about his subsidised bus fare he was banned. Like Uncle Tom he did not complain. Unlike Uncle Tom he got angry.

I am sometimes told how remarkable it is that I made such a success of my career in spite of my poor background and having to leave school at fifteen. But of course that’s nonsense. I succeeded not in spite of it but because of it. And anyway I had some huge advantages. My mother was one of them. She left school at fourteen without a single qualification and had never, as far as I could tell, read a book in her life. Not that there was much time for reading with five children and no little luxuries such as a vacuum cleaner or washing machine or fridge. The only time I remember her sitting down was when there was darning to be done. Mostly socks as I recall.

She seldom expressed opinions – certainly never political ones. But she was utterly, single-mindedly determined that her children should have the education that was denied to her and my father. That meant that, unlike the other kids in our street, we were forced to do homework. It also meant that when the Encyclopaedia Britannica salesman came knocking on our door Mam made my father buy a set.

It cost a shilling a week and the salesman called every Saturday morning to collect the payment. It was the only thing my parents ever bought on the never-never. She told us one evening that the woman who lived opposite had paid for a holiday on the never-never. She could not have been more shocked if the neighbour had sold her children to the gypsies who came to the door every few weeks selling clothes pegs.

So precious were the encyclopaedias that my father built a bookcase especially to protect them. It had glass doors so the neighbours could admire them. Sadly, the doors had a lock and he was the key holder so when he was out – which was most of the time – we kids couldn’t use them. That might have seemed rather to defeat the reason for buying them, but even if we had never opened them they sent out an important message. Knowledge was important. It was empowering. My parents wanted their children to have something they could not have dreamed of in their own childhoods: access to everything they wanted to know beyond the grinding poverty of their own lives. Hence the homework.

There were two rooms downstairs in our house: the kitchen with a coal fire in it where we cooked and ate and washed (dishes and selves) and a tiny front room where no one was allowed except at Christmas and for homework. At least a couple of hours a night. That was when the encyclopaedias came out of the bookcase.

My parents were utterly determined that we would pass the eleven-plus and go to high school – we didn’t use the term ‘grammar school’ then – but beyond that, I don’t think they had any real ambitions for us. There was just the unswerving certainty that if we went to high school we would have a very different life from theirs. And we did pass – all of us. My younger brother Rob and I went to Cardiff High, which was regarded as the best school in Cardiff, if not in Wales. I hated it from the day I joined until the day I left.

The headmaster was a snob and I was clearly not the sort of boy he wanted at Cardiff High – far too working class for his refined tastes. I remember being beaten by him because I was late one morning. I tried explaining to him that it was because I had a morning newspaper round and the papers had not been delivered to the shop as early as usual because it was snowing heavily, which also made it difficult to get around on my bike. I tried to suggest I could not let down the shop’s customers and we needed the money from my job, but he was not impressed. The pain from the beating did not last long, but the anger never faded. Some years later, when I had started appearing on television and was considered something of a celebrity, I had a letter from the school. Would I accept the great honour of making a speech at the annual prize-giving? I replied immediately. Yes of course, I wrote, and then I added a few lines about what I proposed saying. The invitation was swiftly withdrawn.

By then the various chips on my shoulder had been firmly welded into place. Growing up in the immediate post-war years in Splott (an ugly name for a pretty ugly neighbourhood) I’m not sure children like me were really aware of being poor. We knew there were rich people, of course, but we simply did not come into contact with them. The man who owned the timber yard a couple of doors up from my house had a car, and that put him in a totally different class way beyond our own imaginings. It wasn’t, I think, until some of the neighbours got television sets and we were able to see inside the houses of middle-class people like the Grove Family (the first TV soap opera in Britain) that we realised the gulf between them and us.

I remember clearly the first time I was invited for tea in a middle-class home and how surprised I was that the milk came out of a jug rather than a bottle and the jam was in little cut-glass bowls. There was even a bowl of fruit on the table for anybody to help themselves. An old friend of mine, the brilliant comedian Ted Robbins, always says you could tell someone was really rich if they had fruit in the house even when no one was ill … and if they got out of the bath to have a wee.

Envy was one thing. Anger was something else again. Anger not because they were richer than us but because of the sense that some looked down at us for being poor. People like my old headmaster, and the hospital consultant I was sent to see when I was thirteen because I had developed a nasty cyst at the base of my spine. I was lying naked face down on a bed when the great man arrived, surrounded by a posse of young trainee doctors. He took a quick look at my cyst, ignoring me completely, and told his adoring acolytes: ‘The trouble with this boy is that he doesn’t bathe regularly.’ Mortified, I lay there, cringing with shame and embarrassment and hating the arrogant posh bastard and all those smug rich kids surrounding him who were sniggering at the great man’s disgraceful behaviour.

The resentment had been building for a long time. I was barely six years old when it began. It was a Friday lunchtime (dinner time) and although it was seventy years ago I remember it in terrible detail. I had been sent out to the local fish and chip shop to buy dinner. This was a huge treat – the closest we ever got to eating out. All the more special because it happened so rarely and only ever on Fridays. I got back to the house, clutching the hot, soggy mass wrapped in newspaper, vinegar dripping through, the smell an exquisite torture of anticipation. When I stepped into the kitchen my small world had changed for ever.

Dr Rees, our local GP, was there. This in itself was an extraordinary event. He visited very rarely – only when one of us was literally incapable of walking to his surgery – was always handed a glass of whisky by my father who kept a half-bottle in the cupboard for just this purpose, and never stayed more than a few minutes. This time he looked different and so did my parents. They were white and visibly trembling. The tears came later for my mother. I never saw my father cry. The doctor had just told them that Christine, my baby sister and the apple of my mother’s eye, was dead. She had been admitted to hospital the day before, suffering from gastroenteritis.

That is not a disease that kills people – not even in those more clinically primitive days – and for as long as he lived my father believed she died because we were poor. How can I make a judgement on that? All I know, because he told me years later, was that he and my mother had not been allowed to visit their dying child in hospital and, had they been middle class, things would have been different. She had been put in the ‘wrong’ ward and nobody spotted how ill she was. My mother would have spotted it had she been allowed to.

She never recovered from it. She had been blessed with a head of magnificent raven hair. It went white almost overnight. She had been strong and confident and healthy. She lost all that when Christine died. Eventually, of course, she came to terms with the loss. People do, don’t they? But she was never the same woman, and my father’s resentment and anger towards what he saw as the ruling class grew even stronger.

Their one consolation was their surviving children – especially my younger brother Rob, who was born five years after Christine died and took her place in my mother’s affection if not in her memory. As for me, I found another reason to rail against the establishment some years later.

My career had prospered and I was living overseas. On one of my weekly calls home my father told me he was desperately worried because he had been summoned to an interview with the tax man. It was a serious matter. He had been accused of fiddling his taxes. I knew this to be total nonsense. My parents were as honest as it is possible for two people to be. And anyway, my father earned so little from his one-man business he scarcely paid any taxes. That, it turned out, was the problem. My mother was summoned with him because she kept his accounts – such as they were. She told me some years later what happened.

She and Dad had been made to sit on two hard chairs in the inspector’s office and he sat behind his desk. He handed Mam a copy of her accounts and told Dad to swear they were accurate and that they would be in very big trouble if they were not. Dad said they were. Then the inspector said:

‘The accounts show you have earned very little money indeed. If that is so, would you explain how it is that you and your wife were able to take very long holidays not only to the United States of America but also to South Africa? And don’t try to deny it. We have checked out the information handed to us and it is accurate in every detail.’ Presumably some jealous neighbour had snitched.

Dad told me what happened next:

‘Your mother leaped to her feet and she looked that man straight in the eyes and said: “My son lived in America and he lives in South Africa now and he sent us the tickets and paid for both holidays. My son is the correspondent for the BBC. And if you don’t believe me you can watch him on television!”’

I talked to Mam about it in her closing years. She told me it had been one of the proudest moments of her life.

You can add that tax inspector to my blacklist of authority figures. It is a long one and, I fear, still growing.

2

The teenAGE pAGE (#litres_trial_promo)

I was seven when I knew that I wanted to be a reporter. I’d like to claim I was inspired by grandiose visions of speaking truth to power and enthralling my millions of readers with eyewitness accounts of the great events that would determine the future of humanity. The reality was rather more prosaic and a lot more embarrassing.

In post-war Britain poor families like mine did not squander what little spare cash they had on buying books and there was no television, and so much of my spare time was spent reading comics – mostly Superman. Vast bundles of second-hand comics were sent to this country from the United States as ballast in cargo ships. They ended up being sold for a penny or two in local newsagents and then getting swapped between one scruffy kid and another. Superman, as all aficionados will know, took as his human alter ego a chap called Clark Kent and Clark Kent was a reporter. Ergo: reporters were akin to Superman. I would break free from my grim existence in the back streets of Cardiff and save the world into the bargain by becoming Superman. And Lois Lane – adored by everyone who read the comics – would be my girlfriend.

You might say that for a very small boy that logic was perfectly understandable. Not so much for a grown adult maybe. But no matter, when I left school at fifteen I had only one ambition and that was to get a job on a local paper. There wasn’t much alternative. The monster of media studies had yet to be created.

No, you learned on the job – if you were lucky enough to get one. I got mine by lying, or, as we journalists prefer to describe it, through a little creative embellishment of the facts. My years in school had been, to put it kindly, undistinguished and highly unlikely to impress any prospective boss. But I’d been told that the editor of the Penarth Times – a weekly paper in a small seaside town a few miles outside Cardiff – was more impressed by athletes than brainboxes. So I allowed him to believe that I had often been first across the finishing line when Cardiff High School staged its cross-country races. It was technically true – but only because I was so hopeless at running that I was never selected to compete and instead chose to cycle alongside the real athletes shouting encouragement (or abuse). My deception worked.

‘Just what reporters need,’ huffed the editor, ‘plenty of stamina and determination!’ I still feel a twinge of guilt – but only a very small one.

I learned a great deal during my two years on the Penarth Times. For a start: how local papers stayed in business. The good people of Penarth were far more likely to buy it if their names were printed in it, so one of my regular jobs was to stand outside the church after a funeral or wedding and take the names of everyone who had attended. That taught me something else. Accuracy. By and large our readers asked little enough of the paper, but if their name was spelled incorrectly my editor would hear of it. They would demand an apology and a correction the following week. He would not be pleased.

Another skill I developed was how to stay awake in the local library, which was where I spent very large chunks of my time leafing through past issues of the paper in the hope that I might find something interesting enough to fill the ‘Penarth 50 Years Ago’ column. There almost never was anything interesting, so I filled it with boring stuff instead. Nobody seemed to mind – I suspect for the very good reason that nobody read it.

My biggest contribution to the survival of the Penarth Times was on a more practical level. I became an expert in operating a Flit gun: a hand pump you filled with insecticide and squirted at flies or other nasty insects in the house. It was a lifesaver for the Penarth Times when the printers went on strike. The proprietor had refused to shut the paper down. He rampaged around the place declaring that he wasn’t going to allow a couple of bolshie inky-fingered troublemakers to deprive the good people of Penarth of their democratic right to be informed about the local council’s latest pronouncements or who was the latest miscreant to be fined five shillings for urinating against a wall in the town centre after a pint too many. So the paper would be printed without them.