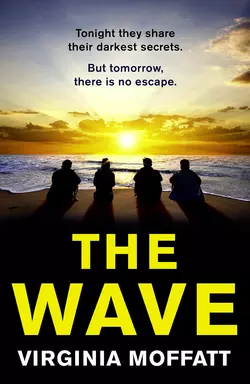

The Wave

Virginia Moffatt

‘I couldn't put my Kindle down until I'd finished it’⭐⭐⭐⭐⭐ Amazon reviewer ‘It's left me an emotional wreck’ ⭐⭐⭐⭐⭐ Amazon reviewer ‘One of the BEST books ever’ ⭐⭐⭐⭐⭐ Amazon reviewer Tonight they’ll share their darkest secrets, but tomorrow, there is no escape… A devastating tsunami is heading towards the Cornish coast. With no early warning and limited means of escape, many people won’t get away in time. While the terrifying reality of the news hits home, one young woman posts a message on Facebook, ‘With nowhere to run to, I’m heading to my favourite beach to watch the sunset, who wants to join me?’ A small group of people follow her lead and head towards the beach; each of them are harbouring their own stories ̶ and their own secrets. As they come together in the dying light of the Cornish sunset, they will discover something much more powerful than they ever imagined. But there is no escaping the dawn… the wave is coming…

The Wave

VIRGINIA MOFFATT

A division of HarperCollinsPublishers

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

Copyright (#u6801ab08-7652-56dc-8acf-7838d25b6a40)

Killer Reads is an imprint of

HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

First published in Great Britain by Killer Reads 2019

Copyright © Virginia Moffatt 2019

Cover design © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2019

Cover photograph © Shutterstock.com (http://www.Shutterstock.com)

Virginia Moffatt asserts the moral right

to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue record for this book is

available from the British Library

This novel is entirely a work of fiction.

The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are

the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to

actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is

entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International

and Pan-American Copyright Conventions.

By payment of the required fees, you have been granted

the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access

and read the text of this e-book on screen.

No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted,

downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or

stored in or introduced into any information storage and

retrieval system, in any form or by any means,

whether electronic or mechanical, now known or

hereinafter invented, without the express

written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008340742

Ebook Edition © April 2019 ISBN: 9780008340735

Version 2019-05-12

In loving memory of Pip O’Neill, and my parents,

Ann and Joseph Moffatt, who taught me

how to face the wave.

‘Death closes all: but something ere the end,

Some work of noble note may yet be done.’

Alfred, Lord Tennyson. Ulysses

Table of Contents

Cover (#uc5026c5c-d315-5300-aeb7-cc036c0f3d65)

Title Page (#u55bf8196-604f-51be-b321-f89c1ecc332a)

Copyright (#u0b9560e5-6c1d-5547-a49b-45287dc0f5b6)

Dedication (#u82817777-e558-5033-af0f-fed49a1c6c50)

Epigraph (#u095a92f6-a492-5c85-9056-65e9ebcfaf83)

Vespers (#u0ebb7cc3-8f29-55d9-9fd7-100f9f85f991)

Poppy (#u65df02f8-641c-52c1-a154-0c76c9446e01)

Yan (#ub96d1677-5ab0-56ba-bda6-28e1c59bbf08)

Margaret (#ub4e56e27-61b9-547e-94e5-dce642d7492a)

James (#u10f52d1a-7b05-59af-b7f0-48372ed01523)

Nikki (#ucb1445df-1e20-58eb-8aae-4d7eb4add8f4)

Harry (#uef4b387b-44eb-5258-a12e-7cd0e5e1bd04)

Shelley (#u8f095cbd-c2c0-5cae-aa8f-29790d2d6f19)

Compline (#u645e36d6-4752-5b8d-b912-d21034232a50)

Poppy (#u51f32a9d-7184-59a7-99f2-467d2d403719)

Yan (#litres_trial_promo)

Margaret (#litres_trial_promo)

James (#litres_trial_promo)

Nikki (#litres_trial_promo)

Harry (#litres_trial_promo)

Shelley (#litres_trial_promo)

Poppy (#litres_trial_promo)

Yan (#litres_trial_promo)

Margaret (#litres_trial_promo)

James (#litres_trial_promo)

Nikki (#litres_trial_promo)

Harry (#litres_trial_promo)

Shelley (#litres_trial_promo)

Lauds (#litres_trial_promo)

Poppy (#litres_trial_promo)

Yan (#litres_trial_promo)

Margaret (#litres_trial_promo)

James (#litres_trial_promo)

Nikki (#litres_trial_promo)

Harry (#litres_trial_promo)

Shelley (#litres_trial_promo)

Prime (#litres_trial_promo)

Poppy (#litres_trial_promo)

Yan (#litres_trial_promo)

Margaret (#litres_trial_promo)

James (#litres_trial_promo)

Nikki (#litres_trial_promo)

Harry (#litres_trial_promo)

Shelley (#litres_trial_promo)

Prayers for the Dead (#litres_trial_promo)

Poppy (#litres_trial_promo)

Yan (#litres_trial_promo)

Margaret (#litres_trial_promo)

James (#litres_trial_promo)

Nikki (#litres_trial_promo)

Harry (#litres_trial_promo)

Shelley (#litres_trial_promo)

Acknowledgements (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

The Divine Office (Liturgy of the Hours)

‘the recitation of certain Christian prayers at fixed hours according to the discipline of the Roman Catholic Church’ before the second Vatican Council (1962-1965)

Vespers Evening Prayer ‘At the lighting of the lamps’ 6.00 p.m.

Compline Night Prayer before retiring 9.00 p.m.

Matins During the night or Midnight

Lauds Dawn Prayer 3.00 a.m.

Prime Early Morning Prayer 6.00 a.m. (the first hour)

30 August 12.00 p.m.

MattRedwood@VolcanowatchersUK 21 s They were wrong about the Cumbre Vieja volcano on La Palma. If you’re in Cornwall don’t even stop to pack. Get out NOW.

BBC Breaking 12.20 p.m.

… Downing Street confirms the Prime Minister has cut her bank holiday weekend short and will be making a statement at 12.30 p.m.

Poppy Armstrong

30 August 12.45 p.m.

I am going to die tomorrow.

Sorry to be so melodramatic, but if you’ve seen the news, you’ll know it is true. It took a while to sink in, didn’t it? The idea that, only yesterday the geologists at Las Palma were so sure the seismic activity they were observing was nothing unusual they didn’t even raise an alert. The revelation that if it hadn’t been for a bored intern noticing that the tiny tremors were building to a huge unexpected one, we’d have been carrying on with life as normal; the knowledge that it took so long for that intern to persuade her superiors that they were about to witness a massive volcanic collapse, there are now less than twelve hours before half the mountain falls into the sea, raising megatsunamis that will hit the American, UK, Irish and African coasts by eight o’clock tomorrow morning. So that I and thousands of others will be killed by the time most of you are getting out of bed. The how, when and why of our deaths making headlines around the globe, before it has even happened.

I’m still trying to think of it as a blessing of sorts. After all, it’s more than most people get – victims of car crashes receive no such warning; the terminally ill can’t know the exact point their disease will overwhelm them; the elderly face a slow decline. I’m lucky, really, to know the precise instant my life will end. It provides me with this one, tiny consolation: knowing how much time I have left means I get to plan how to spend each moment. And I mean to make the most of every last second.

Because … for me, the information has come too late. The authorities have managed to evacuate some hospitals, and it seems that local dignitaries can’t be allowed to drown, but they say there is no time to execute a rescue plan for the rest of us. We will have to make our own way, by road, rail or boat: three million people attempting to leave this narrow peninsula simultaneously. Already, it is a less than edifying sight. The roads are too narrow, the station too crowded, the boats available in insufficient numbers. I do not want to spend my last hours like this, frantic, rushing, out of control, in a race I have no chance of winning.

Perhaps I am wrong, but I have weighed the odds, and finding them stacked so heavily against me, I have made my choice. If this is the remaining time allotted to me, I will spend it doing what I want. The sun is shining, the surf is up. It’s a perfect day for the beach. There’s no point keeping the shop open, so I will pack a bag, bring my tent, and pitch it down at Dowetha Cove, my favourite place in the whole world. If this is to be my last day, my last night, I want to spend it doing everything I love: swimming, surfing, lying out among the stars. I want to make the most of the time left to me.

Perhaps there are some people out there who feel the same. If so, it would be good to have company.

Join me, won’t you?

Like Share Comment

25 Likes 10 Shares

15 other comments

Alice Evans Roads not too bad at the moment. I wish you’d come with us, Poppy, but sending you lots of love x

20 mins

Jill Hough Poppy, I just don’t know what to say. Thoughts are with you.

10 mins

Andrew Evans Saw the news couldn’t believe it. Are you really stuck? Useless, I know, but sending love.

Yan Martin We’ve not met but I’ve made the same calculation. See you on the beach.

20 seconds

VESPERS (#u6801ab08-7652-56dc-8acf-7838d25b6a40)

Poppy (#u6801ab08-7652-56dc-8acf-7838d25b6a40)

I stand at the top car park, gazing down on the beach below. If I needed any confirmation the news is not a hoax, the silence and emptiness provide it. On a sunny August Bank Holiday, with an offshore wind, the sea should be full of surfers and screaming children diving through the waves. The sand should be crammed with family groups, couples sunning their bodies side by side, pensioners in their fold-up chairs. Everywhere should be movement: parents struggling down the slope with bags and beach balls, their offspring running ahead, shouting in anticipation of the joys to come, people in wetsuits striding towards the water, surfboards under their arms. But the beach is vacant, the air free of all human noise, the only sound the screeching gulls and the ruffle of the wind in the bushes behind. It is as if the world has ended already and left me, a sole survivor, to survey the remains. Normally, the sight of an empty shoreline would fill me with joy – the knowledge that these waves are for me alone – but not today. Today, I find myself unable to move, either to the car to collect my belongings, or to the beach below. Instead, I stand by the sea wall, staring at the yellow sunlight glistening on the blue-green waves, listening to the birds whose calls rise and fall with my every breath …

Years ago, when I was little, I used to stand at this spot, on the last day of the holidays, not daring to go down. Every step forwards was an admission that it was nearly all over, that there was nothing to look forward to but the long journey home and school the week after next. Every year, Mum, perhaps, sensing my emotions, and who knows, maybe even sharing them, would tap me on the shoulder, ‘Come on, I’ll race you,’ she’d say, knowing that my desire to win overtook every other feeling. Standing here, I’m overwhelmed by a wave of longing for her, wishing she was here, issuing me with such a challenge again. A useless desire at the best of times – she has been gone so long, I sometimes struggle to remember her face and voice – but today it seems more pointless than ever. What could she do, if she were here? What can anyone do?

A glance at my watch is a reminder how quickly the minutes are passing. The sun is still high in the sky, but it is moving inexorably towards the west; the surf is at its best now, but that will pass. I need to get down there if I am going to make the most of it. And really I should make the most of, and stick to my plan, otherwise I might as well have gone with the others in the van. I have to be decisive. I return to the car, grab my rucksack, tent and surfboard and walk towards the slope. I will have to come back later for the furniture and refreshments, but it’s still awkward carrying so much stuff. I stagger down the stone path, which gradually gives way to sand, first a light dusting and then my feet are sinking among the hot grains. It is a struggle to stay upright with all the equipment I am carrying, but I force myself forward, sliding down the incline until I reach the firmer sand just above the high tide mark where it is a relief to put everything down. As I am sorting out the pop-up tent, a memory surfaces – another day, another pop-up tent, another beach – Seren and I preparing for our first surfing adventure. ‘It’s not as good as Dowetha,’ I’d said, ‘but it will do.’ I had had every intention of bringing her to Dowetha one day, before everything went wrong between us. I never will now.

Once I have set up camp, I realize I am happy to be alone for once. I appreciate the freedom of undressing with no one watching, the fact that there is no one in my way as I run to the shore. No one to jockey with for the best position in the water. No one to block me as I throw myself into the ocean, drenching myself in the spray and foam. The sea has been waiting for me; I gasp at the cold, as it welcomes me into the rise and fall of its chilly waters.

When I have acclimatized to the shock, I paddle out to the breaker zone, watching for the swell coming from the horizon. I position my board, wait for the right moment, and then stand upright to ride the wave. Soon I am lost in the act of riding through water and foam, warmed by the sun, cooled by the wind, repeated over and over again. I am so absorbed that, at first, I don’t notice the man on the surfboard. It is only when he has paddled to the breaker zone a few yards away from me that I spot him. He is tall, white, with a mass of curly hair. He nods hello and I acknowledge him with a raised arm. I don’t like to talk when I’m surfing. I prefer the silent communication of lying in wait together, rising to hit the crest at the perfect moment, sweeping towards the beach at speed until the foam peters out into tiny bubbles, where we can jump off and head back to our starting point. Over and over again, we follow the waves in the same pattern. Occasionally, I give my companion a smile after a particular good ride, but in the main we are both focussed on the line between the area where the surf forms and the beach. Our world is reduced to this one short journey from sea to shore, over and over again until I have lost count of how many waves we’ve ridden, how long we’ve been in the water.

At last, the chill of the sea begins to penetrate my wetsuit, my shoulders start to ache, and so I shout, ‘Last one?’ He nods, and we ready ourselves for the next swell. This time, as we mount our boards, the wind builds up and it is harder to stay steady. I crouch down low to avoid toppling off, glancing behind to see a mountainous wave racing towards us. I time it perfectly, catching the crest and pulling myself up. I stand triumphant on its back, enjoying the thrill of the rush to the shore, before I notice something is wrong. The other surfer is not with me, and when I look back I can see his surfboard floating on the water. There is no sign of him. In a panic, I paddle towards it as fast I can, though it’s a struggle in the stronger current and the increased swell. Spray breaks over my head, salt water fills my mouth, causing me to retch. Ahead of me I can see a head bobbing up and down, arms flapping; then he sinks below the surface, a few feet from his surf board. My arms are hurting with the effort, my body exhausted with the battering of the waves, but I cannot abandon him. I cannot. The knowledge that I cannot abandon him, gives me a spurt of energy, shooting me forwards to the spot where I saw him go under. I dive down, eyes smarting, searching for his body in the blur of blue, green and yellow. I can’t see him, and now my lungs are gasping, so I swim to the surface, gulping huge breaths of air. I am about to dive again, when to my relief his head comes back up again. I race towards him, grabbing his torso before he can sink again, holding tight as a large wave rolls over our heads. He is heavy, gasping for breath; it is a struggle to keep hold of him, particularly in these strong currents. His board is still bobbing to the side; his leg has caught on the leash and it is too tight to disentangle out here. I tell him to lie back and he relaxes into my body – which makes it easier to keep hold of him as I backstroke towards the board. As we arrive, he has the sense to grab it and I can push him up. Soon he is lying on top, red faced, worn out from the effort to survive; for a brief second I wonder whether it was worth it, for either of us. Then practicalities intervene: we are cold, tired, we need to get back to land.

Thankfully, once he has a chance to recover his face begins to lose its purple flush; he is able to raise himself to a paddling position. I give him a push in the right direction, before striking out for my own board. I mount it and follow in his wake as he begins to paddle, first tentatively, then with more strength and purpose. At last we reach the shallows, where we slip off, wavelets splashing around our feet. He staggers to the edge of the beach, trailing the surfboard behind him, before sitting in the wet sand. The cord has tightened with the struggle; it takes both of us to loosen it, and wrest the rope off. He is left with an indented mark all the way around his ankle which he rubs ruefully.

‘Thanks. Thought I was going to drown for a minute …’ He grins, ‘Ironic, considering.’

‘Considering.’ I return his grin. ‘I’m Poppy,’

‘I know. I saw your post. Yan.’

‘You’re the one who replied? I thought you might be joking.’

‘It’s like you said … There’s no point hanging around, we might as well make the most of what’s left.’

I am so happy that someone read my post that I smile broadly, immediately regretting it when his returning smile is accompanied by a look I find all too familiar. My ‘puppies’ look’, Seren used to call it, in honour of a long chain of men whose crushes developed within minutes of meeting me. I never quite understood it as I never intended to give them any encouragement. Seren thought it was a combination of having big breasts and smiling too much. Perhaps she was right, but I’d discovered by then that people trusted me when I smiled, and being penniless and parentless, I’d always had more need than she for allies. Back then it was easy enough to deter the puppies with a casual kiss for her and an arm around her shoulder. I have long since lost that defence, and somehow I always find words fail me. I am left with deflection, so I suggest we go back to my car for the rest of the gear. Thankfully, he is happy to agree, and by the time we reach the car park, the doe eyes have gone. Which is a relief. Because now he is here, it is a physical reminder to me that I haven’t imagined this whole thing. There really are only a few hours left. The knowledge is terrifying enough without any of the complications unwanted attention can bring. What I need tonight, is a friend, someone who can help me make it through the dark. Watching Yan lift the furniture out of the car as he chats away cheerfully, I think he might be able to do that, which is a comfort, because comfort is what we both need.

Yan (#u6801ab08-7652-56dc-8acf-7838d25b6a40)

Poppy … Poppy … Poppy … A name to march by. A vision of pale beauty on Facebook – slim hips, round breasts, long black hair - that is going a long way to helping me fight off the fear. It’s a fantasy I know, but given I’ve had the shockingly awful misfortune to be trapped here by the floods, I deserve a little luck, don’t I? Poppy … Poppy … Poppy … I walk through the shrubland to the beat of such thoughts. There’s a breeze up, but the sun is strong, and with a tent and food supplies on my back, the journey is tougher than I’d expected. I haven’t been this way for ages, and have forgotten how the land rises and falls, the bushes overhang, their roots throwing obstacles in my path. I stumble frequently. Today is made even worse by the waterlogged soil, which has created bog after bog for me to navigate. Normally the sight of the sea ahead – greeny-blue water glinting in the sunshine – would be enough to motivate me, but today it has lost its allure. It’s not just the thought of the destructive powers that will be unleashed tomorrow – I am thirsty, sweating; my legs ache, my boots are clogged with mud. I can’t help feeling that by the time I arrive at Dowetha I’ll be too tired to appreciate it.

At the stile onto the cliff path, I stop for a break, relieved to remove my burdensome rucksack and hurl it to the ground. I find a bottle of water and a bar of chocolate, plonk myself on my coat to protect me from the damp earth. I sit with my back against the wall, gazing back at the cow field I have just crossed and the standing stones in the distance. I’m hoping that by not looking at the sea, I can quell the panic, and pretend for a short while at least this is an ordinary hike, on an ordinary day, and nothing much is about to happen. I fail miserably. As soon as I stop, the full force of the last few hours sweeps over me like a tidal wave. My mind races through the events of the day, over and over again, leaving me no room to escape …

The news trickled out slowly at first. A twitter rumour followed by a rash of speculation on Facebook. Followed by a breaking news line on the BBC. By the time the first full article was up, their website crashed. Last time that happened was 9/11. Remember that? I was sitting at a computer at York, horrified by the suffering of people thousands of miles away. Today, as my screen filled up with a dizzying array of facts and figures, images, analysis, infographics, it dawned on me that this time the rest of the world would be the appalled bystanders, while I was here, right in the thick of one of the danger zones. And being on peninsula meant this particular danger zone would be more dangerous than most. I’m a statistician; it didn’t take long to make the calculation, to realize there was no hope of getting out of here alive. They were too many people, trying to leave by too narrow an exit. We didn’t have a chance. With the whole of the South East and Welsh coastlines expecting a battering, the government made it clear evacuation efforts would have to be focussed further north. There would be no use relying on the Dunkirk spirit to come to our aid. It’s not that people wouldn’t want to help, but anyone with a boat would be too busy getting themselves to safety, they wouldn’t have time to come down here and rescue us. There was some talk about organising plans, but most commentators agreed that there weren’t enough airstrips, and with the airlines arguing about airspace, the unions about staffing, and the Transport Secretary being too paralysed with doubt or fear to intervene, the wrangling got nowhere. It was clear to me we were on our own. There would be no way out.

I’m not sure how long I sat at my desk, considering my options. Should I cadge a lift from James in the vain hope that we could outrun the water? Hide under the duvet, with a bottle of whisky for company? Pills before bed, so I’d never wake up? None seemed appealing. It was only when I turned to Facebook that I found what seemed to me the obvious solution. The minute I read Poppy’s post, my mind was made up. Making the most of the time left sounded better than sitting in traffic or drinking myself into a stupor. And she was hot, the kind of woman I wouldn’t normally have a chance with. But in these circumstances? Anything might happen. So I gathered my belongings together, swimming trunks, warm clothes for the night-time, kagoul just in case, camping equipment, sleeping bag, tent, food and threw them in a backpack, and because I hate leaving a book unfinished, my partly-read copy of The Humans.

I was just emptying the fridge when there was a knock at the door. It was James, bag over his shoulder, keys in hand, road map at the ready. Oh, James. Ever the optimist. I tried to explain to him he was wasting his time but he wasn’t having any of it. He was desperate to persuade me to join him but I was equally adamant. Story of our friendship. Him half-full, me half-empty. Always leads to arguments in the pub and then days of mutual sulks till one or other of us tries to put it right. Today we took great pains not to go into our usual combative mode. When it was clear we couldn’t agree, we had a rather awkward goodbye on the doorstep and went our separate ways. It was so odd, that goodbye on the doorstep. Five years of propping up the bar, putting the world to rights, and now we’ll never see each other again …

… Never see each other again. The reality of that hits me like a wave of cold water. I managed to keep the dread at bay while I was walking, but now I’ve stopped for a bit, it is rising in my stomach again. I push it back down again as I get to my feet. I should keep moving, live moment, by moment. There is simply no point thinking about the future I don’t have. It doesn’t change anything. I hoist my pack back on my shoulders. The straps chafe; it feels heavier than before, but the rest and food has done me good. As I walk, my thoughts return to Poppy; I imagine her falling off the board, enabling me to come to her rescue. In her gratitude she opens up her wetsuit, and lets me rub my face in her breasts, and more besides …

Poppy … Poppy … Poppy … I walk to the beat of her name, thinking only of the ground in front of me, till I reach Dowetha. I dump my luggage at the clubhouse where I keep my surfing gear. I grab a wetsuit, and force my thighs through the constrictive material. Jeez, I’ve got fat. Working from home has confined me too my desk for too long. I catch a glimpse of myself in the mirror, wincing at the beer belly that indicates too many nights in the pub, too few in the water. God, I need to lose weight, an absurd and pointless anxiety now. I pick up my board and leave my gear behind. There is no need to lock the doors behind me – who will come here today but me?

As I turn towards the slope, it suddenly occurs to me that the message was fake, that I have turned up here full of ridiculous hopes that are about to be dashed. That all I’ve done is tire myself out with a long walk to reach a deserted beach and the prospects of facing my death alone. It is a relief to reach the top of the slope and see signs of her presence. A small blue tent pitched above the high tide mark, towels and a blanket spread out beside it. And there she is in the water: a slim figure, striding the waves till they crash on the shore. It is all the signal I need to run down to the water’s edge, ploughing through the waves with my board. I am careful not to come too close, I don’t want to crowd her. She is so focussed, she doesn’t notice me at first; it is not until I reach the surf zone that she acknowledges me with a wave and a smile. What a smile. It drives away every fear. I no longer care about anything other than the bliss of surfing alongside her. Waiting in unison for the swell, positioning the board, crouching, standing, riding the wave, till it takes us back to the beach. Then striking back out to sea for more. Again and again and again. We do not speak, we do not need words, already we are intimate. I could stay like this for ever.

That’s until the cold begins to seep through my wetsuit as the waves begin to strengthen in intensity. Ploughing back to the breaker zone begins to be an effort. Pride won’t let me stop till she does, and I am grateful when, at last, she shouts this should be the last one. I ready myself for the coming wave, rising at its approach, and then … disaster. The surf is stronger than I anticipated, I turn too sharply and slip off the board, my foot tangling in the rope. Suddenly, I am dragged under the water, eyes stinging with the salt, a rush of blue, green and yellow, a deafening gurgle of sea pounding my ears. I try to force myself upwards, emerging to gasp a breath before another wave knocks me down again. My lungs begin to hurt with the pressure, my eyes to tingle, my head to pound, as I flail up and down through the foam. Fuck, this is what is like to drown. As I slide down again, it crosses my mind that I might as well let it happen now. If I survive this, I am only delaying the inevitable. Why bother fighting it for the sake of a few more hours? But even as I have the thought, something inside refuses to give in to it. I push myself up through the water, and suddenly there she is. Her arms are round me pulling me through the waves. It wasn’t quite the way I planned it, but I love this sensation, lying back safe, cradled, as she transports me to my board, pushes me up, and helps me get back to the shore.

Once out of the water, and after we have disentangled the rope, I am able to sit back and catch my breath. I rub my ankle, red from the pressure of the rope, and thank her. ‘Thought I was going to drown for a minute …’ I grin as the thought occurs to me, ‘Ironic, considering.’ She grins back. When we introduce ourselves and I explain her Facebook post brought me, her smile is even warmer; I melt. I can’t stop myself from giving her a dopy smile in return. Luckily she decides she needs to change, giving me the excuse to return to the surf hut and do the same. By the time we meet at her car to collect the rest of her gear, I have composed myself enough to ensure I don’t make an absolute tit of myself.

Half an hour later, we are sitting back at our tents, with a cup of tea and two large slices of Madeira cake. She has taken off her wetsuit, and is now dressed in shorts, a loose cotton shirt and a bikini top that is low cut enough to give a good view of her breasts. I look away quickly, hoping she hasn’t noticed me ogle them, though her arch smile suggests I haven’t been as discreet as I’d wished. I resolve to rein it in. I need to take this easy if I’m to have any success

‘So what now?’ I say as I finish the last gulp of tea.

‘Fancy a swim?’

‘Always wait at least half an hour in case of cramp.’

‘Says who?’

‘My mother,’ I say, laughing ‘Fuck knows if it’s true. It’s just what she always said. Which reminds me. ‘I suppose I’d better call her …’

‘… but you don’t know what to say?’

‘Nope. How about you?’

‘My parents died a long time ago.’

‘Sorry.’

‘Don’t be. Are you close to your mum?’

‘Not especially. She lives in Poland now. She’s a bit of a recluse.’ To be honest, I don’t know if she’ll even have seen the news. It’s been at least six weeks since we’ve spoken, so how can I ring her now and tell her I’m going to die tomorrow? I could add that our relationship, always a tricky one, had got worse after Karo’s death, but that’s way too intimate for someone I’ve just met. I take a different tack.

‘What do mums know anyway? Let’s risk cramp.’

The wind has died down, but the current is still strong. Without our wetsuits the water is gaspingly cold, though once we start moving around we soon warm up. We race each other across the bay, dive and tumble, splash and jump the waves as if we are ten years old. It is exhilarating till the exertion of the surfing catches up with us and we decide, simultaneously, to head back to our camp. We dry ourselves off before flopping onto the towels. Poppy starts spraying suntan lotion.

‘Do my back and shoulders, will you?’ she says sitting up. Her skin is soft to the touch; I rub the lotion quickly and pull on a shirt before she can return the favour. I dive back on the towel and pick up my book; the last thing I need now is an embarrassing arousal. Particularly when she is lying so close to me. I wish I could reach out and touch her, confident that she’d respond in kind but she has given no indication that such advances would be welcome and I don’t want to push my luck. I force myself to focus on the page.

Soon, my eyes are crossing and before long I am asleep. I am walking in a forest with Karo and Mum, who is a few yards ahead of us. Karo and I are getting tired, we ask Mum to slow down, but she quickens her pace. Mum, we cry, slow Down, Wait for us. She doesn’t seem to hear us, and so we raise our voices louder. She stops this time, turns round and looks at us. ButKaro, Yan, you can’t follow me. You’re dead.Why didn’t you tell me you were going to die? I wake with a start. My eyes are full of tears, and to my embarrassment I have dribbled on the towel. I can hear voices above my head. I wipe my eyes and mouth discreetly and sit up. We have a visitor, a white woman in her sixties, who is sitting beside Poppy, talking quietly.

‘This is Margaret,’ says Poppy. ‘She was in her car, but she needed some fresh air. Margaret, meet Yan.’

‘I’m not sure if it’s sensible,’ Margaret’s voice is shaking, ‘I should be on the road, really, but the traffic …’ I exchange a glance with Poppy, not sure whether I should feel glad or sad to be proved right. Margaret takes a deep breath and carries on, ‘It was so hot and there were so many cars – I just had to get out …’

‘Looks like you need to rest for a bit,’ says Poppy. ‘Why not stop and have a drink, then check traffic in a while. If things are better, you can get going, but if not, you can stay as long as you like.’

I know it is churlish, Poppy is right to be so sympathetic and, after all, this is what she promised she would do. Still, I can’t help resenting this stranger interrupting our little idyll. I am not sure I want to share her with anyone.

‘This is so kind of you.’ Margaret accepts a proffered cup of tea.

‘Don’t mention it,’ says Poppy. ‘The more the merrier, wouldn’t you say Yan?’

‘Of course.’ I am forced into my very best polite smile. I even let her know she can use the surf club if she needs to recharge her phone. But, although I take the tea Poppy offers, and join them on the chairs, I don’t join in the conversation; I pretend to read my book instead. It’s not Margaret’s fault – she seems pleasant enough - it’s just that she’s shattered the intimacy Poppy and I have been building up. And now there are three of us, the atmosphere isn’t quite the same. .

I can see it is going to be a very long night.

Margaret (#u6801ab08-7652-56dc-8acf-7838d25b6a40)

I am in the middle of ironing when I hear the news. I’m still trying to work out what I think about the end of a play that I’ve just heard and at first I’m not really paying attention. It is only the mention of La Palma that makes me take notice. All at once, I am back in that horrible room sifting through paper after paper, trying to make rational decisions about which organisations to save and which to cut. Every decision was a bad one, but at the time some options were more palatable than others. La Palma was one of many such arguments. David tried to persuade us we needed the early warning unit because one day something bad would happen. He used the example of Cumbre Vieja to illustrate his point, providing graphic detail of how monitoring seismic activity could prepare us for its possible collapse enabling us to evacuate. His projections even identified Cornwall as a high risk area.But Andrew was equally persuasive the other way,arguing that we couldn’t afford the luxury of spending money worrying about things that might never come to pass. Now it seems that that David was right: the decision we made was the worst of all and I am caught in the middle of it. Shocked, I drop the iron on my favourite shirt. It sizzles, marking the material with a permanent burn as I pull it away. I curse and then it occurs to me that a ruined shirt might be the least of my worries.

The funny thing is that, once I’ve convinced myself that the choice we made eight years ago has nothing to do with what is happening now, my first thought isn’t escape, or whether I might drown. It isn’t even Hellie. My first thought is that I should ring Kath. Ring Kath? That’s a joke. We haven’t spoken for years. She’d hardly appreciate a phone call from me now and where would I start? I switch the iron off, put the shirt to one side and sit down by the window, considering my options. The sun is high in the sky, its beams glinting on the blue water in the bay in front of me. It doesn’t seem possible that this time tomorrow it will be gone. I stand there for far too long, pondering what to do: a balance between driving long distance with my dodgy knees or scrambling for a place on the train. Even getting to the station will take some effort. Hellie always said I’d regret living this far out of town but up until now I’ve always told her she worries too much, citing the freedom of walking into open countryside from my front door. Today, for the first time I have to admit maybe she was right.

Hellie … Thinking of Hellie makes up my mind. I have to get to her as quickly as I can, and judging by the pictures on my TV screen I’ll have no chance of making my way through the crowds at the station. Knees or no knees it looks like the car is my only option. I send her a reassuring text and begin to get ready to leave. Despite the urgency, once I’ve made the decision, I just cannot make myself hurry. A sense of disbelief washes over me. I still can’t quite take in the thought that I am leaving my home for good, that by this time tomorrow the house will be gone and with it all the possessions I can’t take with me. I find myself paralysed with indecision about what to take and what leave behind. Some things are obvious: Grandma’s recipe book, my wedding photos and Hellie’s baby pictures. Others less so. I want to bring the painting of Venice that hangs in the living room. Richard and I bought it on honeymoon – it’s had pride of place in all our houses since – but it’s heavy and takes up a lot of space. I’d love to keep the family Bible. It’s been with us since 1842, with every generation meticulously recorded since then. With regret, I decide to leave it: it is just too bulky. I spend far too long trying to choose what stays and what comes with me. In the end, I store the Bible, the painting and a couple of other precious items in a cupboard upstairs, wrapped in plastic, in the vain hope that this will protect them from the sea. It seems criminal to leave such things behind, but I just can’t manage them. It’s going to be hard enough that I’m going to have to camp in Hellie’s tiny flat for a while without me filling it with clutter. So, in addition to the personal items, I just take a couple of suitcases of clothes, a handful of my favourite novels, and a few CDs.

I am just about to leave when I remember Minnie, my nearest neighbour. She has no family and I can’t imagine the carer has been in today. Who’s going to look after her? I’ll have to bring her with me. I drive along the lane, park in the drive by her cottage and walk up the garden path. There is no answer to my knock, which is not unusual. Minnie often naps during the day, leaving a spare key under the mat for the rare visitor. I have been telling her for ages it’s not sensible in this day and age, but today I am glad she does so.

I call out a greeting as I enter. There is an answering shout from the back room where I find Minnie sitting in a chair, looking out to sea. The TV is on low and there is a remote control on her lap.

‘Is it true?’ she says. ‘What they’re saying on the news?’

‘Yes, I’m just about to leave.’

‘I thought it might be a hoax – like Orson Welles, perhaps.’

‘Sadly not ‘ I sit next to her and take her hand. ‘Come with me.’

‘Where?’

‘We have to get to higher ground. We have to go now if we’re to have a chance.’

‘I don’t know, dear.’ Minnie shakes her head. ‘I don’t think I can leave this house.’ Her clock strikes one o’clock. I try to ignore the panic that it invokes and concentrate all my efforts on her.

‘You’ll drown if you stay here.’

‘But this is my home, dear. I have nowhere else I could go.’

‘You could stay with me and Hellie.’

‘Your daughter? She won’t want an old woman like me around. She’s got a little one to look after.’

‘We’d manage.’

‘I think I’d prefer to stay here. In my own bed. With any luck I’ll sleep right through it.’

Why does she have to be so stubborn? I blank out the ticking clock and offer to make her a cup of tea, hoping that perhaps she just needs a little more time. Hellie calls while I am in the kitchen. ‘Mum, where are you? Are you on the road yet?’

‘At Minnie’s. I’m trying to persuade her to leave.’

‘You need to get going; they say the roads are jammed already.’

‘I will.’

‘Please get out of there.’

‘As soon as I can.’ There is a wail from the end of line.

‘I must go. Toby needs me. Call me when you’re on the road.’ She hangs up.

With renewed urgency, I return to the sitting room, only to find that Minnie has fallen asleep. Her mouth is open, her head droops forward on her lap. She often does this, drifting in and out of wakefulness for short intervals. I have to leave, but I can’t just abandon her. I put the cup on the coffee table and wait, watching the rise and fall of her chest. It is just like sitting with Grandma, in the days before her final illness. I was in my twenties, then, a time when old age seemed remote and unreal. Forty years have passed since and though I still have the energy and health of the well-off retiree, a life like Minnie’s can’t be too far away. Perhaps she is right. Perhaps it would be best to sit and wait for the wave to take us away rather than escape to battle through years that will only weaken my body into helplessness. I shake my head. What am I thinking? I’ve only been retired a couple of years. There is so much I want to do still.

‘Margaret? Are you still here?’ Minnie suddenly raises her head, ‘You must be going, dear.’

‘Not without you.’

‘It’s all right, dear. I’m too old to start a new life. I’d rather stay here.’

‘But …’

‘I’ll be asleep, anyway. I never get up before eight. Much the best way.’ She waves away further protest. ‘Don’t worry about me. I’ll be fine. I’ve got Misty to look after me.’ Right on cue, the grey cat enters the room, meanders across towards his mistress and sits on her lap, purring contentedly. ‘You see? I have everything I need right here. You have a daughter and grandchild to live for. Go.’

I hate to do it, but Minnie is insistent, and she’s right – I do have more to live for. I head out to the car, drive off down the lane and onto the road to Penzance. At first all is well. I speed along, hopeful that the reports of traffic jams were exaggerated. Even so, the sight of the vivid green grass, the bright blue sky and the sea sparkling in the distance is filled with menace. As if, underneath the surface of the water, there is a malevolent being that will bring the sea to life and destroy me. I feel sick and anxious, a mood not improved when I hit a queue of cars four miles from Penzance.

The traffic moves slowly. I inch forward and now the traffic reports are of solid jams further ahead. By three o’clock I have just reached the outskirts of Penzance. This is a nightmare, made worse by my engine beginning to steam. In my hurry, I forgot to check the water levels. Something else Hellie is always nagging me about – this car has a propensity for overheating if stuck in traffic too long. I switch off the engine to cool it down – the cars ahead aren’t moving, anyway – and try to think. I glance down at the map. They say Dartmoor is safe, but that’s still over eighty miles away. I’ve driven four miles in two hours. At this rate, I’m never going to make it. That can’t be right. It can’t be possible that I won’t get out of this alive, that I’ll not get to see Hellie and her family ever again. I pull out my map to see if I can find an alternative route. But the radio announcer is reporting pile ups at Bodmin and Redruth and gridlock on every road going north. There are no alternatives, this is my only way out.

I put my head on the steering wheel and howl. I’ve had long and happy life; in a previous era sixty-seven would have been considered a good innings, but I’m not ready to die yet. I still have too much to do. I am booked on a tour of Greece and Italy in the summer. I have signed up for a Masters in Theology in the Autumn. Hellie is pregnant. It cannot be possible that I will miss out on all that. But … there are too many cars, the road is too packed. If we don’t get a move on, nobody in this jam is going to make it. None of us. By tomorrow morning we might have reached Truro – and it won’t be far enough. Even if we could outrun the wave, the constant rain this summer means that the water table is so high the whole county will be awash with water. A line from the Bible comes to me: ‘The water prevailed more and more upon the earth, so that all the high mountains everywhere under the heavens were covered.’ So God, you gave Noah fair warning – why not us? And don’t tell me a wild theory about a possible volcanic collapse was a divine message. Not on the basis of that flimsy evidence. Why didn’t you give us more? Why didn’t you allow us enough time to build ourselves an ark? Why are we left behind to drown?

I cannot stand any more news, so I switch to the CD player. Immediately the sound of French monks singing Vespers in plain chant calms me.

Glory be to the Father, and to the Son, and to the Holy Spirit:

As it was in the beginning, is now, and ever shall be, world without end.

Amen.

I stare at the crowded road ahead. It may be my only chance of escape but I’m beginning to believe it’s no chance at all. I am hot and tired and I can’t stay in this car for much longer: I need some air. I passed the turn to Dowetha Cove a mile or so back. Perhaps if I go down to the sea, spend a bit of time by the water’s edge, the fresh air will revive and renew me. Perhaps by then the traffic will have died down and I can try again. I am not giving up yet, I tell myself, I am just taking a breather. I turn the car round, passing the long queue of drivers heading towards Penzance. Ahead of me flecks of golden sunlight light up the blue sea, calming my spirits. I text Hellie, traffic slow, but on my way. I don’t want to worry her yet. I just need to get out of the car for a bit, breathe some sea air and then I can be on my way again.

James (#u6801ab08-7652-56dc-8acf-7838d25b6a40)

I hate it when Yan is right. He’s always so smug about it. Even in these circumstances, if we meet again, I bet he’ll be smug. Because he always is. It’s infuriating.

I was so sure he was wrong three hours ago when I turned up on his doorstep, telling him we had to go, NOW. He just replied in a maddeningly patient voice that due to the number of cars on the road, the average speed of traffic, bottlenecks and likelihood of crashes we wouldn’t be going anywhere. He smiled like a patronising professor, putting me right on the glaring errors of my pathetic dissertation and was totally immune to my increasingly panicked pleas that he leave with me. I couldn’t understand how he could stand there, so resigned to the fate I was certain we would be able to escape. I know he’s always had a fatalistic streak, but this deliberate refusal to move seemed stupid beyond belief. Though I begged and begged, he wouldn’t budge. In the end, I had to give up on him and go it alone. I hated leaving him, but if he was going to be such a stubborn bastard there wasn’t much I could do about it.

I was still sure once I was on the open road. Though it was busy, the traffic kept moving initially, while sunshine, green fields and glittering sea lifted my spirits. Poor Yan I thought, as I raced towards Penzance. Poor Yan. I put the radio on, singing along to Uptown Funk to push my fears away, as I pretended that this was just an ordinary summer’s day and I was heading north to see friends. It worked for a while, but my optimism was short-lived. The road stayed clear for only a few miles. As signs to Penzance began to appear, suddenly cars were coming from every direction. Red brake lights flashed up in front of me. Drivers beeped their horns, yelling obscenities at each other as I found myself at the end of a long queue of traffic and came to a grinding halt. I wound the window down, pushed my seat back, grabbed a sandwich and told myself it was a small setback. It wasn’t time to panic yet. I switched on the radio to hear the tune that has tormented for too many months …

Never Leave Me, Never Leave Me

Believe me when I say to you.

Love me, darling, love me, darling,

Cos I’ll never, ever be leaving you.

Lisa’s first big hit as she transitioned from dreamy ballad singer to techno pop artist, the song that told me that she was gone for good. The song she wrote for the man she said had broken her heart, that she dropped from our set because, she said, she didn’t need to think of him any more. The minute I heard her new version, the version she had released without telling me – same lyrics, same basic melody, but surrounded by a thudding beat and a swirl of technical effects – I knew it was the goodbye she hadn’t got round to saying to my face.

Oh Lisa … It had been weeks since I’d allowed myself to think of her. Having wallowed in a miasma of self-pity for the six months that followed her departure, I had been trying to put her behind me. I’d almost been successful, too. It was only when I caught a news article, or heard her on the radio like this, that the familiar sickness returned, the longing for the woman I could no longer have.

Lisa, Lisa, Lisa … I loved the way her red hair fell in front of her face and she had to flick it aside. I loved her talent and the force of her ambition that drove her to make the most of her gifts. I loved the way she could single me out in a room with a look that said I was hers, she was mine. The whole time we were together, she made everything right. I thought she was all I ever needed, which made her absence, when it came, so unbearable. And even after all these months, hearing her voice was painful. It made me wonder whether she had seen the news, whether she was thinking of me at all. Whether somewhere her stomach was lurching like mine as she realized that I was in danger. I took out my phone. Despite my attempts to eradicate her from my life, I’d not managed to delete her number yet. I’d stopped the late night calls pleading for her return, but I hadn’t quite had the strength to let her go all together. I scrolled through my contacts to find her smiling face, the last picture I took, one day on the beach just before she left. I pressed dial – and then stopped immediately. What was I thinking? There was nothing she could do to help and I shouldn’t ask. Even if she did respond, it would only be out of pity. I don’t need pity now. Actually, thinking about it, pity would be the worst. I put the phone away, relieved to see the car ahead was moving forward. I followed suit. We crawled around the outskirts of Penzance as I raised the clutch, pressed the accelerator, shifted forwards and stopped. Clutch, accelerator, stop, clutch, accelerator, stop, clutch, accelerator, stop. I tried not to think about how long this was taking, but instead that every move forward was taking me out of the danger zone.

Even so, I was beginning to doubt myself, so I was pleased by the distraction of the sight of a young black woman at the junction to the A30. She was standing by her backpack and, although all the cars were going past, she had the confidence of someone who knows they will get picked up soon. I pulled over.

‘Want a lift?’

‘Please.’ I climbed out, put her backpack in the boot and opened the front for her.

‘Thanks,’ she said, kicking of her shoes. ‘I wasn’t sure if anyone would stop. Everyone’s a bit …’

‘I always stop for hitchhikers,’ I said. Now I could see her face more clearly, she looked familiar, but I couldn’t place her and I didn’t want to say anything for fear of sounding creepy, ‘I’m James, by the way.’

‘Nikki. You haven’t got anything to drink have you? I’m gasping.’ I handed her some water. ‘How come you’re hitching?’

‘Couldn’t get a train.’ She looked out of the window. ‘Beautiful day, isn’t it?’

‘Yes.’

‘After all that rain. Lovely to have the good weather again.’

‘Yes.’ Clearly she wasn’t keen to talk about our situation. I took her lead. Tried to pretend we were just a couple of people who had just met, travelling together for a while. It was better than giving into the gnawing anxiety that Yan was right, that we wouldn’t get out of here alive. ‘So what do you do then?’

‘Right now? I’m a waitress in a chippy in Penzance.’

That’s where I’d seen her before. ‘I was in there the other week. You probably don’t remember …’ She stared at my face a moment, ‘Yes,’ she says, ‘I do. You wanted a saveloy and we’d run out so you had to wait. The wanker behind you was less patient, and kept shouting at me to hurry up, even though I couldn’t cook them any faster. You told him to shut up, which was nice of you, given how big he was.’

‘I wouldn’t have done it after hours,’ I said, grinning. ‘But 6.00 p.m. in daylight, with loads of people around? I’m very brave in those sort of situations.’

‘Well, anyway, I appreciated it.’ Nikki smiled back, filling me with a sense of joy that I hadn’t felt in a long time. It was crazy considering the fact we had just met, but somehow it seemed as if we’d always known each other.

‘It’s just a summer job,’ she said. ‘I’ve just finished a Masters in French Language and Literature. My parents are in Lagos with my brother and sister, so I offered to look after their house, while I sort out what next. How about you?’

‘I work in an antiques shop in St Ives.’

‘That’s unusual.’

‘For someone my age? I would have thought that a few years back when I was working in the City. But the job bored me, and I wanted to make music. So I jacked it in to come down here to play on the folk scene. The shop was supposed to be a stopgap, but I got hooked on the smell of old furniture and the music thing didn’t work out, and here I am …’

‘That’s cool.’ Phew, unlike Lisa she didn’t think it a dead-end job that made me dull. The conversation flowed for the next hour, enabling us both to pretend we haven’t noticed how long it has taken us to reach our current location. There’s been a white van in front of us for ages, blocking the view, but the road has dipped and now we can see over it to the long line of cars stretched ahead. They are barely moving. I have been driving for three hours and travelled eight miles. At this rate, we have no chance of reaching safety in time.

‘Shit,’ said Nikki. ‘That doesn’t look good.’

‘No.’

She looks away. I have a feeling she might be about to cry and not want me to see. I am close to tears myself. I was so sure Yan was wrong and I was right, but now, as I sit here and weigh up our chances, I have lost that sense of certainty. I switch on the radio to hear the news that every road north is blocked, a fact confirmed by my satnav, which is helpfully stating that the current estimated time of arrival will be eighteen hours. Eighteen hours? That’s three hours too late. We sit, staring at the road ahead, unsure what to do. It seems impossible that we could die tomorrow. We are too young, there is too much we haven’t done. Keeping moving is our only chance of surviving. The hopeful side of me wants to keep moving. Wants to pretend that the satnav is broken, the traffic reports are exaggerated. But I can hear Yan’s voice in my head, ‘You’ll get as far as Falmouth before the wave sweeps you off the face of the earth.’ Despite his tendency to over-dramatize, I’m reluctantly beginning to concede his point …

And it’s terrifying. I am twenty-nine years old. I don’t want to die tomorrow. I should have years ahead of me. Years to achieve all the goals that seem to have eluded me. I had such grand plans when I left my corporate hell hole and moved down here. I was going to record an album, live the life of a simple artist. I’ve managed none of it. I enjoy my job but all I’ve got to show for the last few years is the hours I’ve put in to pay my rent. And when Lisa came into my life, all my ambitions became subsumed by hers. What a waste.

‘I was thinking,’ says Nikki softly, ‘that woman on Facebook might be right …’

‘The one at Dowetha Cove?’

‘I saw the post while I was standing there. I didn’t want to believe her, but I’ve seen the station, and …’

‘My friend Yan is already there.’

Ahead of us, the white van moves forward but it is belching smoke and is forced to pull over to the side of the road. As we pass, I see the driver standing looking grimly at the steaming, overheated engine. I think about offering a lift, but almost immediately we come to a halt again. I look at the map, my watch, the tachometer. I look at the queue of traffic ahead that’s going nowhere. It is hot in the car and the sandwiches are getting stale. I gaze at the blue sky and the glowing yellow sun. At this time of day the sea will still be warm and I wouldn’t mind a swim. I think if I spend another hour in this car, I am likely to go mad. Nikki looks at me and nods, even though I haven’t said anything.

The road ahead is blocked, but the south road isn’t much better. Despite Nikki’s news about the station, it seems as if some still think there might be trains and are travelling in the opposite direction. Either way, we aren’t getting anywhere in a hurry. Weighing up the odds, I come to a decision. If it’s a choice between sitting here for hours waiting for the inevitable, or sitting on the beach … I rev the engine, indicate, turn out of the traffic queue, point the car in the opposite direction, and take the road south.

Nikki (#u6801ab08-7652-56dc-8acf-7838d25b6a40)

The sun streaming through the curtains wakes me, but it takes a while for me to come to my senses. I feel hot, my body sluggish. What time is it? I only turned over for a quick doze at nine, thinking the street noises would wake me, but I’d forgotten I switched rooms last night after being freaked out by noises in the graveyard. The back bedroom is much quieter and so I have slept on undisturbed. Shit, it’s nearly one o’clock. I’ll have to get a move on if I am going to make my train.

As I draw the curtains I remember I promised Mum and Dad that I would mow the lawn. They’ll be pretty pissed when they get back – they’re so proud of their English country garden, it makes them feel like true Brits. They’ll be mad as hell when they see the tangle of brambles smothering their rose bushes and the grass almost as high, but I couldn’t help it. I’ve been doing lates all week and just haven’t had the energy. I will scribble them a note and hopefully they’ll ask my brother, Ifechi or Ginika, my sister to do it and will be over it by the time I’m back.

I take my scarf off, rub my hair with pomegranate oil and comb it through, tying it in a pony-tail to keep it off my neck. I’m hot and sticky and still smell of chip fat. There’s no time to shower; instead, I have a quick wash, moisturize and hope the coconut oil masks the smell. I throw on blue shorts and a lilac T-shirt, stuff clothes and beauty products in my bag and rush downstairs. I’m hungry, but there’s no time to eat either, so I grab an apple and a packet of crisps. I’ll just have to hope the train’s buffet is well stocked.

I am out of the house and down the alley in no time. There is no one much about; they’re probably all at the beach. I speed right at the corner, then left. It is only as I’m approaching the Longboat Inn that I notice something is wrong. The road ahead is jammed with cars in both directions and the station is densely packed with people, all the way through the car park round to the harbour. The queue spills out into the road and stretches back alongside the railway tracks down to the pub. What is going on? I fight my way through the crowd and join the end of the line. My train is in the station, but I can see it is already full; I doubt I’ll even get on the next one. I find a place behind two middle-aged white men. One is hunched, with a worried expression on his face, the other rocks back and forwards besides him. I take off my backpack and place it on the ground.

‘What’s up?’

‘Eh?’ The worried man is about to respond, when the other one, starts saying and over again, ‘The wave, the wave, the wave,’ as he rocks. My neighbour turns to him in soothing tones, ‘It’s OK, Paul. We’re getting on the train and we’ll be fine.’

‘Will we, Peter? Will we, will we?’

‘Of course. Why don’t you get your DS out and play a bit of Pokemon?’ Paul acquiesces. He pulls the DS from his pocket. It has an instant calming effect; he sits down on a suitcase and is soon absorbed in his game. The worried-looking man turns back to me. ‘My brother. Gets a bit anxious. He’s autistic, you see. What did you say?’

‘What’s happening?’

‘Haven’t you seen the news?’ I shake my head. He shows me the headlines on his phone. A volcano collapse, a megatsunami, and the whole of Cornwall under water. I can’t take it in. It explains the crowds, but it just doesn’t seem possible looking at the calm, sparkling sea. I scroll through my phone to find the story is everywhere. My inbox is full of messages. Nikki it’s Stef, are you OK? Niks it’s Max, ring me. Nikkidarling it’s Mum, where are you? Even my little sister Ginika has texted, though I note wryly Ifechi hasn’t bothered. There are too many to respond to, and I don’t know what to say anyway. But I reply to Mum telling her I’m waiting for a train, and send Ginika a message to say I’m having an adventure. After that I sink to the ground, my legs shaking. If only I hadn’t been so tired last night. If only I’d stuck to my original plan and travelled through the night after work. I’d be with Alice in Manchester, glad of my lucky escape. That last-minute decision to have a lie-in has come at quite a cost.

‘Are you all right?’ Peter says as the train pulls out of the station. I’d have hoped it might mean the queue would move forward but it doesn’t shift.

‘What do you think?’

‘Sorry, stupid question. But it’s too early to panic. It’s only an hour and a half to Plymouth. They’re bound to lay on extra trains, aren’t they?’

He’s being kind and I can see he is trying to reassure himself as much as anything; but I’m not so sure. They have struggled with staffing on this line lately, and what if there isn’t enough rolling stock? I have too many questions, and I am so hungry and thirsty I can’t think. I open the pack of crisps, wishing I had brought a drink. I daren’t go into the shop in case I lose my place. The sun is hot and I feel dizzy. I close my eyes. There is something of the heat, the stink of petrol, the beeping horns that reminds my first trip to Lagos when I was eight. I was such a pampered child! What a fuss I’d made about everything, the crowded streets, the dust, the lack of amenities in my grandparents’ house. It was a wonder, Dad would say in later years, that they hadn’t packed me on the first flight home.

The sound of an engine makes me open my eyes as a sleek red train comes into view. The crowd cheers as it arrives at the station until they spot the number of carriages. Only six! They should be laying on twice that many. There are shouts from the passengers on the platform who rush forward as the railway guards try and keep control. Gradually the train fills and the queue moves forward. By the time it is ready to depart, we have moved a few hundred yards further up. It’s not far, but it is progress. I eat the apple slowly. With any luck, I’ll be away by six. The train leaves. Hopefully the next one will be along soon. But nothing comes and there is no information when I check the website. I try to calm my nerves by listening to Rihanna, try to imagine this is all over and I’m out of the danger zone heading to Manchester. It works for a while, but then I sense the mood of the crowd change. I take off my headphones and catch the tail end of an announcement over the tannoy. I cannot make out the words, but ahead of us there are angry murmurs that quickly become shouts. The rumour passes along the line until it reaches us. Trains are needed for evacuation of the northern coasts. There will be no trains from Penzance after five.

Two more trains. That means only two more trains. Everyone is making the same calculation and suddenly the patience of the queue is exhausted. People rush forward from every angle, jumping in the road between cars to get ahead of their neighbours. Everyone is yelling and ahead of me I can see a couple of fights breaking out. Peter pulls his brother to one side, clearly intending to wait it out, but I can’t see any point in staying here. I jump to my feet, pushing against the throng surging forward, fighting my way down the road until, at last, I am clear. Now what? Hitch a lift? It seems the only option left. I walk up to the junction for the A30. The road ahead is filled with traffic. My heart sinks; this looks as bad as the trains. The cars are moving slowly, but none seems inclined to stop. I check my phone; I’m thirsty. I really wish I’d brought a drink with me. To distract myself, I scroll through Facebook, looking for some signs of hope that people are getting out. But all I find is a post that is being shared widely. A woman called Poppy inviting people down to Dowetha Cove because she thinks we can’t get away. It seems defeatist, but then, looking at the road ahead, maybe she has a point.

This is ridiculous. I can’t believe escape isn’t possible, that someone won’t stop for me. Right on cue a car pulls up and the driver sticks out his head. He is older than me; I notice dark wavy hair, kind eyes. Not another beautiful white boy. I swore off them after Patrick. But then he smiles at me and, despite myself, I smile right back.

‘I’m James,’ he says as I slip into the passenger seat.

‘Nikki.’ I kick off my shoes and somehow, white boy or not, I feel immediately at ease. He offers water when I ask and is interested in me and interesting to listen to. If I don’t think too much, I can continue to pretend this is just an ordinary summer afternoon. That I have just met a man who might be worth a bit of time and effort. I’ve always been quite good at telling stories, and this one is a reassuring one. I am happy, I am safe. Good times lie ahead.

Handsome white boy is as good as I am at keeping it light and the hour passes swiftly, particularly once I discover he was the one to send a prize arsehole packing the other week. Even so I can’t help noticing we’re not moving as fast as we’d like. Every time there is a break in the conversation, I try not to glance at my phone which is full of news of bad traffic. I try not to think about how slowly we are travelling or how long it will take us to get anywhere. It is when we reach the top of the hill that I cannot stop pretending. The traffic is almost stationary for miles ahead. The radio and James’s satnav confirm it. We cannot get out.

I turn away from him. Despite our instant camaraderie, I don’t feel able to show him my feelings yet. I gaze out of the window again at the sea, the beautiful, calm, perilous sea. The sea that will kill us tomorrow. How can that be possible? All my plans, my dreams of living in Paris, of working as an interpreter for the UN, gone in a flash. And my family. What can I say to my parents? To Ifechi and Ginika? Being a teenager is hard enough. How can I do this to them? I think again about that post on Facebook, the thought that if there’s no escape, spending time with others, having fun, might be better than sitting in a hot car going nowhere.

It turns out that James knows about the woman on the beach too; his friend Yan is already there. The thought hangs in the air that we might turn back and join them but we don’t say anything, and when the van in front pulls off, James drives on as if we are going to continue. But shortly after he stops. We look at each other, though we don’t say a word we both know what the other is thinking. James indicates right and turns the car around to join the last stragglers driving to Penzance in search of a train. As we pass the cars driving north, I can see the astonishment on the passengers’ faces. I’m astonished, too, but the die is cast. I was dead before I even woke up this morning. This is the only option left to me now and I am going to take it.

Harry (#u6801ab08-7652-56dc-8acf-7838d25b6a40)

Harry Edwards. Survivor.

That’s me.

Always have been, always will be.

There’s no fucking way a stupid volcano is going to stop me now.

The whole world might have heard the news and panicked, but the minute I found out, I started thinking, as I always do in a crisis.. While everyone else was running scared, I started planning ways to escape. Even though I had a hunch this was a hoax, I wasn’t taking any chances. Watching the pundits on the telly with their charts and CGI images declaring the end to be nigh, I couldn’t help remembering how the same serious people told us Trump would never win and Brexit would never happen. Tonight, when that volcano doesn’t collapse, I’m convinced they’ll all look very stupid. But it’s better to be safe than sorry, isn’t it? So, I weighed up the options and came up with the perfect answer. The road was the obvious choice, but also the stupid one. With so many holidaymakers trying to get along the same narrow route, I knew it would get clogged in no time. And the railway wouldn’t be much better. I knew this was a situation that required an intelligent solution and I found one. I bought myself a boat. I discovered a bloke online who has a holiday cottage in Penzance and a motor cruiser in the harbour. Now Shelley and I are heading into town while all the sheeple are travelling in the opposite direction. I felt smug at first, seeing them all going nowhere fast, knowing we had our way out, but I should have factored all the idiots going into Penzance to try the train. We’ve been stuck in traffic for an hour now, a delay we could do without. I’m trying not to let it bother me. We’re still moving faster than the cars going in the opposite direction, and once we’re on the water there’ll be no stopping us. But I could do without the sun pounding through the front windows; even with the side ones down, the Maserati is hot and sticky. The only thing I have against this car is the lack of air conditioning.

‘Are you sure it’s going to be OK?’ Shelley says for the third time as we crawl past the supermarket by the roundabout.

‘Of course it is. I said I’d sort it and I’ve sorted it. And you know the best part, babe?’

‘What?’

‘We’ve got ourselves a brand-new boat. When all the fuss has died down we can moor it down somewhere on the south coast and spend weekends out on the water. You’d like that, wouldn’t you?’

‘That would be lovely.’ Shelley’s voice doesn’t have quite as much enthusiasm as it should have, doesn’t have quite as much faith in me as I’d like. She used to always trust my judgement, but lately she’s been questioning my decisions a lot more. Perhaps it’s inevitable, now we’re living together. But I could do without it right now. Right now it would be nice if she showed a little faith. After all, I’m doing this as much for her as for me.

The road towards the harbour is even more jam-packed than the A30, cars are stuck in both directions, horns beeping, drivers shouting. I look at my watch. Two thirty. I said to the bloke in London we’d be here by two. I text him to say we’re nearly there. The cars ahead are maybe going nowhere, but it’s not far.

‘Come on, we’re walking.’ I pull up in a lay-by.

‘I’ve got my heels on.’

‘It’s less than a mile. Grab your bags.’ I take out my suitcase from the boot and pull up the handle. Shelley has brought two huge holdalls which she places on each shoulder, like ballast balloons. She follows obediently as I make for the harbour. The journey is more complicated than I had anticipated. The road is crowded with people waiting for the train or trying to get to the harbour and it is a struggle to make our way through. Cars beep incessantly and, as we approach the car park, we can see a closely packed throng reaching all the way to the quayside and along to the main docks. The crowd is thinner on our side of the road, but it’s still an effort to push our way against the tide of people heading for the station. The mood is unpleasant; there are shouts and scuffles and across the way I can see a couple of big blokes sizing up for a fight. I want to get to the boat as soon as possible, but every few minutes I’m stopped by Shelley wailing for me to slow down, pleading for help with her bags

‘I did suggest one bag only,’ I say when she catches up.

‘I need them both.’

I want to suggest that she dumps one but she has a face that suggests tears are imminent and an argument will only slow us down. There’s nothing for it but to take one of hers and keep moving forward. It is hard work, harder as we arrive at the quay, where we are pressed in on every side, with some people heading in the direction of the station, others towards the harbour in the hope that the one ferry will return and rescue them. I push a path through the wall of bodies, conscious that all it would take would be for one trip and we’d be trampled on. At last we make it through to the quayside where I sit down in the wall to catch my breath. Shelley throws her bag down with relief, and then gazes past me towards the quayside. ‘Is there enough water?’

I turn round. The tide is going out. Already the mooring chains are half exposed to show their green seaweed and barnacle coverings. The waves lap against an edge of dirty brown sand which is filled with small wading birds searching for food. It should be just about deep enough to depart but then I realize something else. There isn’t a single yacht or speedboat left. Not one. All that remains are a few battered rowing boats that wouldn’t make it further than the harbour wall. Where is my boat? Where is my fucking boat? Even though the evidence is in front of me, I still can’t accept it. I walk over to mooring nineteen where Bob the fisherman was supposed to meet me. There is nobody there, and the mooring chain leads nowhere.

‘Was it definitely here?’ says Shelley. ‘Not round the corner?’

‘Don’t be stupid, Shells. This is where they keep the private boats. The docks are for commercial vessels’

‘Perhaps he moved it.’

‘Shit,’ I say. ‘Shit, shit, shit, shit, shit.’ A seagull flies overhead, depositing it’s droppings on my shoulder as it passes. Shelley laughs.

‘It’s not funny!’ I’m furious, but she cannot stop giggling, until I shout at her, ‘Shut the fuck up, will you?’

‘It was just the timing.’ She gets a tissue out of her bag and removes the worst of the gloopy mess off my T-shirt. It leaves behind a white smeary stain. I ring the owner, no answer. I send him a text. No answer. Then another, which finally gets a response. Sorry – boat’s been sold. Bob waited till two thirty but had to leave; he sold it to someone else. Hope you can find another.

What about my refund, arsehole? I text back, but he doesn’t reply. Fucker probably thinks I’m done for, and he might as well pocket my £500. He doesn’t know what’s coming for him. When I get back to London, as I definitely will, I’ll take him to the cleaners. No one gets the better of Harry Edwards, no one.

‘What are we going to do?’ Oh, Shelley. Why are you so young? You’re beautiful and sweet but not much good in a crisis. ‘Give me a moment to think.’ I look around the harbour. There are thousands of people between here and the station, still thinking they might get a space on a train, or a ferry. I can’t see it myself, there are too many of us. There is no point hanging about here.

‘What are we going to do?’ wails Shelley again.

‘Ssh, I’m thinking.’

I check the news. The roads are as clogged as I thought they would be. There’s also no point attempting to travel north. Clearly not worth taking a risk on the internet again, but surely not every boat will have gone? Surely, in some little cove somewhere, someone keeps a boat for their occasional trips to Cornwall. Some lucky bastard who decided not to come down this weekend will have left us a means of escape that’s just waiting for us to collect it. All we have to do is explore the bays between here and St Ives. Surely there will be something for us somewhere …?

‘We’ll look for another one,’ I say.

‘Where?’

‘In a mooring somewhere. Come on, Shells.’

‘Alison’s just texted, asking if we’re OK.’

Alison is Shelley’s big sister. She’s not my biggest fan, nor I, hers. She thinks I’m not good enough for Shells; it will give me great pleasure to remind her in future that without me her sister would have drowned.. ‘Tell her we’re fine, we’ve got a plan,’ I say. Thinking of sisters, I am reminded of mine. Should I text Val, let her know what’s going on? Don’t be stupid Harry. She doesn’t even know we’re here. Why worry her? Best to let her know when we’re safe out the other side, when I can brag about my brilliant survival skills.

We force our way back through the swell of people, a deeply unpleasant experience. Sweaty bodies push against us, the smell of panic and fear. I can feel Shelley stumbling in my wake, but I can’t hold her in this crowd, we both have to make our way through, until, eventually, we pass the station and are back on the road again.

It takes nearly an hour to reach the car, place our bags back in the boot and set off again. We crawl back along the way we’ve walked, but once we’re past the quay the road is clear and I’m back in control. We’re not like the hopeless hordes in Penzance, heading nowhere. We’ve got a plan and it’s a good one.

We start at Mousehole, but it’s just like Penzance. A handful of rowing boats are left in the quay. I consider whether it’s worth trying one of them, but they just don’t look seaworthy enough and I’m definitely not a strong enough rower. I look at the lifeboat station, but that too is gone; according to Twitter they’ve taken a load of people up north to safety. Shame we didn’t get here sooner. Still, I refuse to be deterred. There’s plenty of places along the coast; I’m sure we’ll find something. It’s just a matter of persistence, that’s all. We climb back into the car and drive on.