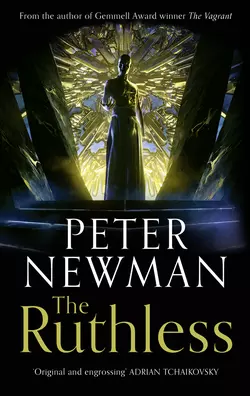

The Ruthless

Peter Newman

Return to a world of crystal armour, savage wilderness, and corrupt dynasties in book two of The Deathless series from Gemmell award-winning author Peter Newman. THE REBELFor years, Vasin Sapphire has been waiting for the perfect opportunity to strike. Now, as other Deathless families come under constant assault from the monsters that roam the Wild, that time has come. THE RUTHLESSIn the floating castle of Rochant Sapphire, loyal subjects await the ceremony to return their ruler to his rightful place. But the child raised to give up his body to Lord Rochant is no ordinary servant. Strange and savage, he will stop at nothing to escape his gilded prison. AND THE RETURNED…Far below, another child yearns to see the human world. Raised by a creature of the Wild, he knows their secrets better than any other. As he enters into the struggle between the Deathless houses, he may be the key to protecting their power or destroying it completely. THE WILD HAS BEGUN TO RISE

Copyright (#ulink_f05e937e-6cda-57d8-a49c-20e78adb5344)

HarperVoyager

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

First published in Great Britain by HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2019

Copyright © Peter Newman 2019

Cover illustration © Chris Tulloch McCabe 2019

Cover design © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2019

Peter Newman asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008229030

Ebook Edition © March 2019 ISBN: 9780008229054

Version: 2019-05-15

Dedication (#ulink_ef9472fe-7f92-5778-9096-781f56ec0d69)

To AndrewFor being there to catch me

Contents

Cover (#u45b91490-ebdf-5ae3-b298-96b3d0ab1d08)

Title page (#u5f816d87-e35a-5203-a8b8-a512f6962a55)

Copyright (#ua7bd154a-0430-55a5-98f6-2bba5d5dd72e)

Dedication (#ub55736bd-9abf-5a54-8182-d0c4014fa9e9)

Prologue (#u6546ed10-e50d-5421-967a-62c6ba9260cb)

Chapter One (#u9eb89a1a-ceb2-587c-a09d-1a0520b0483d)

Chapter Two (#u9713f4b3-893f-5aba-b03b-1ae5e803a9f5)

Chapter Three (#uf64e1725-7b20-5d62-a50f-655c4c9361fb)

Chapter Four (#u4fbff776-34f2-5cf8-b6e5-1e9020d37a63)

Chapter Five (#ub3aba6f4-1d46-558c-8da5-d44d23b3a607)

Chapter Six (#ueeb9832a-a629-5f99-94a1-03477fd37174)

Chapter Seven (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Eight (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Nine (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Ten (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Eleven (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twelve (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Fourteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Fifteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Sixteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Seventeen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Eighteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Nineteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-One (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Two (#litres_trial_promo)

Acknowledgements (#litres_trial_promo)

Also by Peter Newman (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

PROLOGUE (#ulink_62b13ea7-1bc0-574a-85b9-2095cd5f3da9)

She had been elsewhere, between lives, formless and timeless. There was a sense of hanging above angry water, of shapes sliding under the surface, of shadows rising to feed, hungry, yet unable to break through to where she hung. She both feared the shapes and was drawn to them. But when she tried to go down to them, something held her up: unbreakable strands threading around and through her. Where she herself was neither light nor shadow, these strands glowed blue and violet, glimmering like crystal. Together they were a tether connecting her to the world beyond, to a platinum sphere, her anchor. This, she knew.

And so she had watched the shadows swirl and throw themselves against the divide, pressing against it, bending it, but unable to push through. On instinct, she tried to reach out, sure that if she could touch whatever separated them, it would part for her. However, the bands of light that protected her also fixed her in place.

The shadows could not reach her any more than she could reach them, but they could whisper, and the sounds they made walked slow through the non-space, inching their way upwards. Though she had no bones in this place, no flesh, no blood, no limbs, the thing that remained had something of her senses, and she turned towards the whisperers, straining to listen.

Words came, trickling into her consciousness. Secret words, forbidden ones. The kind that excited her. Yes! This was true. Recalling something of her old nature sharpened her resolve. She was a hunter of secrets. She was a hunter of demons.

This time, like the times before, she told herself that she must remember what they said, that she must hold on to what she learned. It was important.

The voices were not as one. Some feared her, some hungered for her, and others made senseless noise that buffeted, making her rock from side to side, like a pendulum of glowing wires, or a hunk of meat on a rope.

But it was not meat that the shadows hungered for. They wanted memories, the very pieces that made up her soul. If they could tear one away, it would leave a space. Tear a second and the space would grow, becoming a burrow in her heart for them to hide inside.

There was a change above her, a tightening of the blue-violet strands, and she knew from experience that she would soon leave this place and become herself again, whoever that was.

The shadows sensed it too, redoubling their efforts, pressing so close that she was able to make out features, teeth and torn edges, ragged holes that allowed glimpses of muscle bunching naked inside.

She could feel a tension now, a pull at her back accompanied by the desire to rise. But a new noise made her resist and hold where she was.

Tucked within the writhing mass of shapes was a smaller, more human one, crushed, crying out, over and over: ‘Pari!’

She knew that name. For it was her own. She knew the voice of the one crying out too. Someone dear, someone she loved. Peering closer, she saw his face bubble up from the darkness, set like a pimple on the back of some great beast.

The features belonged to Arkav, her brother. But that was impossible! Arkav was in a young body, very much alive. He could not be here. Could not be here and there at the same time. Unless some part of him had been lost between lives, bitten from him when he had last hung in this place.

Their gazes met, and he called out again, begging for her help.

She fought to go to him but the strands held her tight, making her feel like a prisoner. This too, was truth. I am a prisoner, she thought, and knew this had long been the case.

Then Arkav’s face was blocked out by the rush of shadows, of hungry mouths and the screeching of something tearing, of the distance between her and the angry dark shrinking in the blink of an eye.

The strands of light grew tight about her, like a fist, and she was rising, as fast as the chasing shadows, then faster, leaving them and her brother behind.

This time, she told herself, I will remember.

CHAPTER ONE (#ulink_a9a318f1-6042-5655-b342-863d756e9c24)

Pari came back to the world slowly. Everything was black, muted, unreal, and her mind felt fuzzy. There were things she needed to remember. Something about her brother? Yes, that was it. The details skipped around the edge of her consciousness, still close enough for her to grasp, but other things were fast taking her attention.

There were straps around her arms, legs, body and head, holding her tightly in place.

There was something in her mouth that held it open, and a textured shape was pressing down on her tongue. Somehow she knew it was a mesh, and that it held a Godpiece, the anchor that kept her soul from drifting free between lives.

At first she’d thought she was in darkness, but someone stood over her blocking the light, close enough that the fabric of their clothes fell across her like a veil, tickling her nose as their hands worked at the strap behind her head. After a few moments it was removed and the obstruction in her mouth slipped free.

The other straps remained in place.

When the figure stepped away from her, a room of stone was revealed, windowless and grey, with pillars, well spaced, that spiralled slowly from the outer wall into the centre where she lay. Cool air brushed her naked skin, and she saw there were seven strangers moving around her, their robes whispering as they walked. The sound tickled a memory in her mind of something important. She had recently heard whispers that carried a hidden meaning. What was it?

Each figure carried a crystal-tipped wand that glowed, providing the only light in the room. Odd bulges moved within their robes, as if stunted limbs grew from their middles. Masked faces watched her, each one divided down the middle, black on the right, white on the left. One of them, she could not be sure which, spoke: ‘One woman is welcome here. Are you that woman?’

Pari worked her mouth as her brain snapped fully awake and put all of the pieces together. It isn’t just a question, no, it’s a test. This is a rebirthing ceremony. My rebirthing ceremony. And not my first – I’ve been here before. Many times. She could feel certainty rising within her and with it, knowledge.

I amDeathless.

The thought rang in her mind, powerful and true. She had died many times but had always come back. So long as her blood remained in the world, be it a son, daughter, grandchild or someone who sprouted from that line; her soul would have a new home to go to.

I am Deathless.

An image came to her of a castle – her castle – floating high above the forests and rivers of the Wild. And within the castle, faces; of her hunters and servants, guards and Story-singers, Cutter-crafters and attendants. Not just one set but legions of them, getting older, being replaced.

She had ruled over them for generations. The sky-born who shared her castle, and the road-born below, scattered in scores of settlements, all hugging the Godroad, all facing the Wild.

I am a Deathless of House Tanzanite. And she knew that there were others in the house, all with their own castles and peoples and sprawling bloodlines. And she knew that House Tanzanite was one of seven, and that they were all united in a duty to hunt the demons of the Wild and stand guard over humanity. But that did not mean they got on, nor agreed on all things. Pari grimaced as she recalled just how true that was.

The robed people surrounding her were the Bringers of Endless Order. They had pulled her soul from wherever it had gone between lives and put it into a new body. Now they were testing to see if they had been successful. Whether they had truly hooked a human soul or had brought something else into the world.

She flexed her fingers and toes to see if she had a full complement, and that they would move to her will. To her relief, the digits obeyed. Sometimes a vessel sustained injuries, and sometimes the rebirth was not a complete success. Pari had heard stories of Deathless that only had partial control of their bodies, where the soul was misaligned, allowing a demon to slip into the cracks, gaining power over a hand, an elbow, or worse, the jaw.

The Bringers watched her closely. It occurred to her that she still hadn’t answered their question.

‘I am Lady,’ she began, then stopped. The voice that issued from her throat was unfamiliar. High, girlish.

Seven masked faces leaned closer at her hesitation, no doubt searching for signs of possession. If she made a mistake, innocent or otherwise, they would assume the worst, declare her abomination, and end her.

She cleared her throat. ‘I am Lady Pari Tanzanite.’

‘Lady Pari Tanzanite is welcome,’ replied one of the Bringers. ‘If you are she.’

‘If,’ hissed the others.

‘If you are she,’ continued the first Bringer, ‘you will prove your humanity. Look at yourself and tell us what you are.’

Her body was more petite than her usual preferences, however there was some tone to the muscles, suggesting a reasonable level of fitness. Golden tattoos glittered against her sky-born skin, one for each significant death she had experienced. The nature of the tattoos and their frequency were decided by the High Lord of House Tanzanite at the end of Pari’s lifecycles. This was unfortunate as Pari’s relationship with High Lord Tanzanite was cordial at best.

She did not need to look to know that there was gold ink on her shoulder, just as she knew there were gold spots on the pads of her fingers and a single mark on her lower lip. She looked anyway. It was not above the Bringers to place false marks to confuse, or her High Lord to have added a new one to make a statement about Pari’s previous life.

But there was nothing obvious. If there were any new tattoos, they were tucked somewhere out of sight.

‘I feel the marks on my fingers and remember my first life, where I had touched a lie and refused to let it go, even though it burned me.’

The Bringers did not react, watching her with a searing intensity.

‘I see the mark on my shoulder and remember my fourth life –’ she frowned ‘– and the poor fortune that ended it.’

Again, the Bringers remained quiet, though she suspected they had shared some look at her expense.

‘I feel the mark on my lip and remember my fifth life, and the power of an expressive face.’ Which was a polite way of saying that when she needed to, she could pout people to death. It was still up for debate whether High Lord Tanzanite thought this was a good thing.

‘What is the name of your high lord?’ asked one of the Bringers.

‘What is the name of your Deathless brother?’ asked another.

‘Priyamvada is the name of my High Lord. My Deathless brother is Arkav.’

In her first life she’d had another brother who had lived a normal, single life. To her horror she found his name evaded her.

‘What is wrong with him?’ asked the Bringers together.

Pari’s full body shiver was constrained by the straps. ‘Pardon?’

Only a single Bringer repeated the question: ‘What is wrong with him?’

She sighed to herself. Here is the test.

Arkav had not been himself for several lifecycles now. Her once flamboyant, confident sibling had become prone to dark moods and bouts of misery. More than once, he had cut himself. She had done her best to hide the full extent of this, as had her house, but the Bringers had secret ways. They knew things. It was more than possible they had discovered her secrets.

It was also possible that this was a trick question, designed to get her to bluff. There was no way to know for sure.

A third possibility occurred to her. At a rebirth ceremony, the only ones allowed inside were the vessel, the Bringers of Endless Order, and the Crystal High Lord of the Deathless being reborn; in this case Priyamvada Tanzanite. The last she had heard, her brother had been taken into the High Lord’s care. Perhaps the question about Arkav was being asked for the High Lord’s benefit. Perhaps Priyamvada was lurking behind one of the many pillars, observing.

It did not matter. If Pari failed the test, her brother was doomed. And besides, Pari had grown rather fond of herself over her lives. ‘Nothing is wrong with Arkav,’ she replied, enjoying the way the Bringers leant back in surprise before adding: ‘that I cannot fix.’

There was a pause and then the Bringers stepped forward as one, the gemslight from their wands dazzling. She tensed in preparation, even though there was nothing she could do to defend herself. When they stepped away, the straps had gone from her chest and limbs.

‘Lady Pari Tanzanite is welcome,’ said a Bringer.

‘Welcome,’ echoed the others.

One by one, they left, pausing to nod to her as they did so. She caught a glimpse of peridot eyes within one of the masks, too bright, and was sure she knew them. It was assumed that the Bringers never left their sanctum, save to perform rituals, but masked as they were, no one knew their identities, they could walk freely across the land and never be recognized. They could have lived among the Deathless in secret all these years and no one would know.

Pari had never liked the Bringers. They held too much power for her liking. Their incredibly sinister appearance doesn’t help either. Just what are they hiding under those robes? She suspected the answer would be unpleasant, but that only piqued her curiosity.

When the last of them departed the chamber was plunged into darkness. She sat up on the slab and stretched, relishing the ease of movement. Her last body had lived to a ripe old age, and she had not been kind to it. To sit up, simply to think something and do it was such a joy! She swung down from the slab and, seized by the urge, jumped up and down several times.

Navigating from memory, she felt her way around the circular chamber, past the inner pillars, to the outer ones, until she found the wall. From there it was a simple matter to follow its gentle curve. As she walked, the stone was cold underfoot, but the chill did not reach her joints.

A voice from nearby sapped the happiness from her. Female, deep, cold: ‘Lady Pari.’

Pari dropped to her knees. ‘High Lord Priyamvada, you honour me.’

There was a pause, and Pari felt the rebuttal before she heard it. ‘No.’

Well, she thought, at least I won’t harbour any illusions of false affection.

‘Your boast to the Bringers. You stand by it?’

‘Of course,’ replied Pari. To lie to the Bringers of Endless Order was a crime. They both knew it. My High Lord just wants to make it clear that I’m in her trap.

‘Good. House Tanzanite needs its Deathless in good order, and it has missed Lord Arkav’s full attention.’

‘I would see him.’

‘He waits for you with Lord Taraka.’

‘Lord Taraka? Is there business?’

‘Yes. Prepare for it.’

‘At once.’

Priyamvada had been ancient when Pari first became Deathless and was by far the oldest of their house. She used her words sparingly, and never went anywhere on a whim. Pari’s instincts told her that something else was going on. Her nature led her to ask what it was.

‘While we are alone,’ answered Priyamvada, ‘know that this is Arkav’s last chance. He must add to his legacy or lose it entirely.’

Pari nodded, the gesture lost in the dark. ‘I understand.’ There would be many others vying for the chance to become Deathless. If Arkav was cast out, his Godpiece would soon find a new home.

‘Know too, that if he goes, you will follow.’

‘Forgive me, High Lord, but that I do not understand.’

‘Really? You have left me no choice. Either you will see that Lord Arkav is fit to serve the house, or you have defiled this sacred chamber with your lies.’ She heard the sound of the High Lord moving away. ‘I am fond of your brother. It would be a great sadness to lose him.’

‘Yes,’ agreed Pari.

The great stone door groaned as it opened, spilling light into the chamber. She caught a glimpse of Priyamvada’s silhouette shaking its head, and then she was alone.

There were three exits from all Rebirthing Chambers. One for the Bringers, a second for the Deathless, and a third for abominations. This last one was set into the floor at the far end of the chamber, and led to a sudden drop from the bottom of her floating castle all the way down to the chasm below.

She had used the third once before, in the castle of Lord Rochant Sapphire, and sworn never to again. Even so, it was with great reluctance that she stepped through the second door. She had a feeling that whatever was coming would be far from pleasant.

Sa-at hunched down within the branches, making himself as small as possible. He did not want the people below to see him because he knew they would be scared and run away.

It was rare to see Gatherers from Sagan this far off the path. There were eight of them, doing their best to fill their heavy bags with berries, nuts and yellow funghi. They always travelled in groups and they always moved quickly, nervous faces darting, jumping to every sound. Unlike Sa-at they wore thick clothing and heavy gloves to protect themselves from scrapes and cuts. Even in the daytime it only took the slightest scent of blood to wake the things of the Wild.

The dense canopy hid the suns from sight but by the glow of the leaves, he could tell it was moving from afternoon to evening, and that Vexation, the stronger of the red suns, was dominant.

‘Come on,’ said one. ‘We should be getting back.’

‘Just a bit further,’ said another.

‘We got a good haul,’ said the first. ‘Why risk it?’

‘See this?’ One of the hooded figures pointed to something on the floor and Sa-at leaned out from his hiding place for a better view. Branches shifted under his stomach to support his weight, the leaves stretching to form a veil between him and the group below. Sa-at had made many pacts with the nearby trees. He fed them whispers and little pieces of his kills, and in return they sheltered him.

Not every part of the forest was his ally, in fact many of the trees hated him, but even they tended to leave him alone.

Sa-at did not know why.

From his new position, he could see a little better but the thing the group were looking at still eluded him.

‘It’s a creeper,’ continued the speaker. ‘If we follow it, it’ll take us right to the mother plant and we can bleed it for Tack.’

There was a brief debate which Sa-at observed with interest. Because of its rarity, Tack was extremely valuable. Usually, the hunters were the only ones that dared go deep enough to find it.

‘Think of it!’ said the one leading the argument. ‘One haul would keep us all for a year. We could repair the fences, or we could buy a tame Dogkin to pull our barrow. Or …’

The opposition’s point was simple. They could get lost if they went deeper. They could die, or worse.

One of the group had a habit of waving a hand as she talked, making little circular motions like a whirling leaf when it fell to the ground. Another clasped their hands in front of them, as if they had just caught a baby Flykin and wanted to shake it to death. They spoke too fast for him to follow all of the words, but he could see that some were worried and some were greedy, and that the majority wanted to press on. He also enjoyed copying their gestures.

When the Gatherers had moved away, Sa-at sprung from the branches, flinging out his arms so that his coat of feathers flew out behind him. For the few seconds it took to land, his face was split by a joyous grin, then he rolled across the floor to come to a stop where the group had chewed up the ground with their heavy boots.

The creeper vine sat there like a bulbous tongue stretching from the dark of the trees. He stayed in a crouch, folding his arms behind his back as he inspected it. The skin of the creeper was pale, suggesting it had not yet fed. It had not inflated either, laying flat and lumpy where it should be firm and round.

As he pondered this, a Birdkin flew down to join him. At least, it looked like a Birdkin. Its body was only slightly smaller than his head, and covered in feathers of the same black as those that made Sa-at’s coat. He knew it was also a demon, and that this made people afraid.

Sa-at did not know why.

‘Crowflies!’ he said.

‘Sa-aat!’ it screeched back.

He pointed at the creeper with his nose. ‘Wrong?’ he asked.

The Birdkin hopped closer and turned its head, regarding the creeper with one of its glistening compound eyes. It twitched one way, then the other, then opened its ivory beak.

Sa-at reached out a hand. His little finger was missing, and sometimes the old wound became itchy. When that happened, or when he wanted to be close to Crowflies, he pressed the scarred knuckle into the Birdkin’s beak.

Crowflies’ neck jerked, as if it were about to vomit, and then he felt the proboscis stir from inside, peeking out to prick his skin.

A flurry of images brushed Sa-at’s mind – a vision of the world as Crowflies saw it, a fractured mosaic. The colours he saw were strange, the reds brighter, the greens darker, and shadows no longer matched the things that made them.

The Gatherers’ footprints stood stark amid the dirt, and among the human ones Sa-at was now shown others that had been there recently, a succession of small round holes, as if someone had poked their fingertips into the dirt again and again.

Spiderkin? wondered Sa-at.

Crowflies gave a twitchy nod. They had dragged the creeper here as a lure. No doubt there was more than just the plant waiting for the Gatherers.

Sa-at made a cage with his fingers. A trap?

Another nod from the Birdkin.

The people with the funny hands will be eaten?

And another.

Sa-at pulled a face. He didn’t like the idea of the people being eaten. He saw Spiderkin all the time but he rarely got to see people. He wanted to see more of them. Maybe there was a way to stop the Spiderkin’s trap …

As soon as he’d had the thought, Crowflies stiffened, unhappy.

‘But,’ protested Sa-at, ‘they’ll die.’

Crowflies gave a shrug of its wings.

He pulled his hand free, sucking the end of it as he stood up.

‘Sa-aat!’

He was being warned not to go.

‘I’m going.’

‘Sa-aat!’

He paused for a moment. Crowflies was his friend, his only real friend in the Wild. The Birdkin had brought him food and drink until he was old enough to hunt. It nursed his injuries, watched his back, taught him. Everywhere Sa-at went, Crowflies was there like a winged shadow. Deep down, he knew it was trying to protect him.

But then he thought of the Spiderkin wrapping the Gatherers in bladesilk. In a week or so he would come by this part of the forest again, and find eight skeletons stripped of everything save the hands and feet.

If he waited another week, the hands and feet would be gone.

The maimed skeletons would hang for a few more after that, and then vanish. Sometimes, much later, he’d see a fragment of bone attached to one of the trees like a trophy, and be certain that he’d seen it before.

His stomach turned a few times and then he started running.

Behind him he heard several squawks and felt the feelings behind them.

‘Sa-aat!’ (Annoyed.)

‘Sa-aat!’ (Go if you want, I’m staying here.)

‘Sa-aat!’ (Exasperated.)

A little smile tugged at the corner of his mouth as he skipped between a tangly mass of bushes. Despite it all, Crowflies would come. It always comes.

The trees gathered closer in this part of the Wild, shutting out the day. Great strands of web ran taught between them. Where it rubbed against the branches, deep grooves were made, red fungus sprouting from it like raw skin. Fat shapes sat within the canopy, their legs bunched together to conceal their true size. Sa-at knew the signs and quickly guessed at their number.

The Gatherers did not.

A couple of them made a token effort to keep watch, though they had no light to penetrate the gloom, and were of little use. The others were clustered around a green trunk, as wide as a broad-shouldered man, with pale yellow veins running like marble across its surface. Several creeper vines were coiled at its base.

As he got closer, a nervousness began to grow within Sa-at. He felt something he did not have a name for – a desire to impress. He skidded to a stop and paused. He had very rarely seen people and had never spoken to one before.

One had spoken to him however, when he was tiny, a man called Devdan. Sa-at learned many words from him. He had been kind for a time, and then he had stopped being kind. Sa-at remembered the man’s hands on his throat, and then the threat of fire and sharp things. He had been tiny but the memory was vivid in his mind, like a body preserved in amber. These people seemed kind too, would they try and hurt him as well?

‘I see something!’ said one of the Gatherers, and they all turned towards him. They carried simple weapons, knives and long poles of wood. One carried a sling, that they proceeded to load.

Sa-at had never seen a sling before and was briefly distracted by the excitement of something new. The promise of the unknown made the hairs on the back of his neck tingle.

‘What is it?’ said a voice from the back.

‘Looks like a person.’

‘Ain’t no people here but us.’

‘Said we shouldn’t have come!’

‘Is it a demon?’

Sa-at tried to think of something to say but the excitement and nerves had made him too fizzy, so instead he took a careful step forward.

As one, the group stepped back.

‘Don’t look it in the eye!’

‘Don’t let it touch you!’

Behind them all, moving smooth and slow, the first of the Spiderkin slid down until it was level with the Gatherers’ heads. Upside down, its legs opened like bony petals, tensing to strike.

Sa-at finally found his voice. ‘Run.’

‘Did it say something?’ asked a Gatherer.

‘Don’t listen to it!’ said another. ‘Don’t let it get close!’

A second Spiderkin slipped down next to the first, a third and fourth close behind. These were the scouts, the fast ones. Their job was to slow down the food for their queen.

‘Run!’ he repeated.

‘Don’t listen!’

He did not understand why they were still standing there. The new Spiderkin flexed open as well, the little mouths tucked in their bellies oozing with drool. They were ready. He did not understand why it was so difficult to communicate with these people. Crowflies always understood what he said and all the meanings underneath.

With arms spread wide, Sa-at let out a wild cry and ran towards the group, desperate to get them to move.

The Gatherers cried out in alarm and the Spiderkin paused to assess the new threat. The sling spun round three times and a stone whizzed past Sa-at’s shoulder. He kept running.

The Gatherers fell over themselves trying to retreat, stumbling directly into the Spiderkin.

There was a flurry of legs and screams as the Gatherers tried to flee. They had finally realized the danger, but instead of running back towards the lighter area of the forest (which would have taken them past Sa-at), they ran away from everything, moving randomly off into the dark.

Seven vanished into the forest, but one was grappled by a Spiderkin, his legs kicking wildly as it began to ascend.

Sa-at used his momentum to leap, grabbing the Gatherer’s boot as it thudded into his chest. They swung, spinning on the end of the strand, the Gatherer dangling from the Spiderkin’s legs, Sa-at dangling from the Gatherer’s. Their arc took them into the path of other strands, tying all four together, and sending the other three Spiderkin into a frenzy.

The Gatherer shrugged off his satchel, getting partially free. A last leg was hooked under his shoulder however, and he fought desperately to unhook it. A droplet of saliva fell past them to the floor. That meant the Spiderkin’s mouth armour had pulled back. All the Gatherer had to do was punch it there and he’d be let go.

‘Hit it now!’ urged Sa-at.

However the Gatherer was too busy screaming to notice.

As they swung towards a tree, Sa-at kicked off from it, spinning them faster. If the Gatherer had been caught by one of the big ones it wouldn’t have mattered, they would both have been taken to the lair. However their combined weight and motion was too much for it to hold, and the Spiderkin let go with a hiss.

The next thing Sa-at knew he was on the floor. Before his thoughts could catch up, he was on his feet. The Gatherer was doing the same.

‘Run!’ Sa-at urged.

This time, there was no hesitation. The Gatherer did as he was told.

‘No,’ Sa-at called after him. ‘Not that way!’

But the Gatherer was too busy screaming to listen.

After a moment’s frustration, Sa-at followed him, leaving the Spiderkin to stab at each other as they untangled themselves.

CHAPTER TWO (#ulink_2b50b24e-7808-5ff5-9bcd-650e23920403)

The Gatherers had run blind, stumbling between the trees in a haphazard fashion. Each was guided, by twisting paths and prodding branches, until they had all been brought back together. Then, gradually, the Wild had funnelled them deeper into its heart, to places that even Sa-at avoided when the suns went down.

When the first of them stopped to double over and pant, the others followed suit.

Sa-at watched them from a distance, curious to see what they would do next. Crowflies had caught him up during the pursuit and had settled itself on a nearby branch.

Each member of the group gave their name to prove they had survived the encounter, and each time the rest of the them would smile and reach over to touch the arm of the one who had spoken. Sa-at liked that. He wondered what it would be like to be smiled at in that way. As the last one announced themselves and was welcomed, he copied their smiles from his hiding place and reached out a hand in their direction. None saw, save for Crowflies, who did not care to comment.

‘Sa-at is here too,’ he whispered, and then, so as not to feel lonely, he touched his own arm.

‘I think we’re not far from …’ gasped one of the Gatherers. ‘Or maybe we’re near … I think … no. I don’t know where we are.’

‘We need to get home.’

The others were quick to agree but none of them were sure which way home was. Another discussion started, quickly turning into an argument. Sa-at listened with interest, eagerly devouring the new words. He was particularly intrigued to know that some of the Gatherers had more than one name.

That woman likes to turn her hands and speak.

Her name is Hil.

Hil’s other name is ‘Great Idiot’.

The man who clasps his hands is Rin.

Rin’s other name is ‘Dogkin’s Cock’.

At one point it looked as if the group was going to split up, with one half going with Hil and the other with Rin. However, when Hil claimed to recognize a mossy chunk of rock, they stopped arguing. And when she said they were not far away from a path she knew, Rin told her to take the lead.

She’s wrong, thought Sa-at. They’re going the wrong way again.

Crowflies pointed at the group with a wing and made a derogatory noise.

‘You don’t like them?’

He received one of Crowflies’ looks, where the Birdkin slowly tilted its head to one side as if Sa-at had said something ridiculous.

He watched thousands of tiny reflections of himself shrug in the Birdkin’s eyes. ‘They’re funny. I don’t want them to die.’

That earned him another look.

The Gatherers were too tired to set off immediately. They agreed to take a short rest as it would be the last they could dare on the journey home.

Sa-at pulled himself up onto a thick branch and settled next to Crowflies. What would be the best way to help these people? He tucked his arms in and let his chin rest on his knees. This was a problem that would require thought. He knew they were afraid of him. Perhaps he could chase them out of the forest. However, it would be difficult to herd them over a long distance. And what if they scattered or decided to fight?

While he pondered the problem, he listened to the Gatherers’ chatter.

‘Did you get the Tack, Rin?’

‘Right here.’

There was a cheer, followed by a question, tentative: ‘You’re going to share it with us, right?’

‘Depends on whether you called me Dogkin’s Cock or not!’

They all laughed at that. Sa-at was not sure why.

‘Rin?’ asked another. Sa-at realized it was the one he’d saved.

‘Yeah?’

‘I lost me bag back there. I got nothing.’

‘Don’t worry, Tal. Important thing is you’re alive.’ There was a chorus of agreement. ‘You and yours won’t starve neither. We’ll all share a bit of our take.’ Rin looked round at the rest of the group. ‘Won’t we?’

There was a second round of agreement, though Sa-at thought it was less enthusiastic than before. ‘You checked yourself again yet, Tal? Still no blood?’

Tal raised an arm and examined his armpit. ‘Don’t think so. It’s sore though.’ He pushed his finger through a new hole in his jacket and, after wiggling it around, showed it to Rin with relief. ‘No blood!’

‘No blood,’ Rin confirmed, and a sigh of relief passed round the group.

‘We better go,’ interrupted Hil. ‘Vexation’s the only strong sun in the sky today, and it isn’t going to wait for us.’

An idea popped into Sa-at’s mind as the Gatherers stood up and put away their rations. He kissed the leaf of the nearest tree, leaving a little of his spit behind, and scrambled up the trunk. It did not fight him, though it did not help him either.

Crowflies watched, bemused, as he heaved his way into the upper reaches of the tree. As soon as he arrived, he grabbed a branch and pulled it towards him, creating a breach in the canopy.

A shaft of Vexation’s light, richly red, punched through.

‘Look there!’ called one of the Gatherers.

They rushed to the gap and Sa-at held himself still, hoping not to be noticed. ‘It’s worse than I thought,’ said Hil. ‘By the angle of sunslight, I’d say we only got a few hours. We’re further off than I thought too.’ She blew out a long breath through her lips.

‘Think we can make it?’ asked Rin.

‘Be tight.’

Rin nodded. ‘Will be if you take the wrong way again, you great idiot.’

There was a warmth to the words that took away their sting. Instead of getting cross, Hil squeezed his arm, changed direction and started walking.

The group followed her on the ground, and Sa-at followed them in the trees, walking the tangled pathway of branches. Whenever Hil seemed to be going off course, he pushed the leaves aside to let Vexation’s light guide them.

For hours they trudged. Fear kept them at a good pace, and soon, Sa-at was struggling to get ahead of them. But keep ahead he did, until they reached a part of the Wild where the trees thinned a little and his help was no longer needed. He watched them from a high branch. Though most wore similar clothes, he could easily tell them apart. As each one passed by he gave a little wave. None of them saw.

Fortune’s Eye and Wrath’s Tear had already set, and Vexation was low in the sky. Hil looked up – straight past Sa-at – took a quick bearing, and hurried on. Nobody said anything. They could all feel the change in the air. Soon, night would fall and the Wild would stir in earnest. Grim-faced and determined, the Gatherers kept going, all of their attention on the floor at their feet. The forest had not started to move yet, but it was only a matter of time.

Perhaps that was why they did not notice that only six of the group were still following Hil. Sa-at noticed. He had been counting them as they went. He turned on his perch, scanning the nearby area for any signs of the eighth Gatherer.

There! He saw that one of the group had stopped further back, like a lone reed swaying in the breeze.

He slipped silently from the tree and circled round so that he could approach from behind. Their breathing sounded laboured and they were making unhappy noises with each exhalation, as if in discomfort.

Sa-at was just trying to decide whether to risk talking to them when they fell over.

He watched them for a few moments, and when it was clear that the Gatherer wasn’t going to move, he crouched down nearby and rolled them onto their back.

It was Tal, the one he’d helped before. There were no obvious injuries, no reason why he had stopped. Maybe he’s tired? Sa-at sniffed. Something didn’t smell right. Another sniff and he had located the source. He lifted Tal’s arm so he could get his hand into the man’s armpit. The stink of fear-sweat made him wrinkle his nose. Did all people smell this bad? His own armpits made a smell sometimes but it was nothing like this. In fact, Sa-at quite enjoyed smelling himself at the end of the day.

He found the hole in Tal’s jacket and worked it wide until he could get his hands in for a feel. In the middle of Tal’s armpit, he found a stud of scar tissue, about the size of his middle finger, which was also the same size as the tip of a Spiderkin’s leg. Tal groaned when he pressed it.

On the other side of the scar tissue would be a tiny strand of web. Attached to the web would be an egg, floating inside Tal’s body. When night fell, the egg would hatch and the baby Spiderkin would call to its queen to collect it. Sa-at ran a hand through his hair. He did not want Tal to die.

With a flutter of wings, Crowflies landed next to him and pushed his hands aside with its beak for a closer look.

‘Can you get it out?’

Sa-at held his breath while Crowflies inspected the entry point. After a few moments, it nodded.

‘Will you?’

Crowflies looked from Sa-at to Tal and back again as it considered the question. Eventually it hopped over and tapped Tal’s thumb with its beak.

‘No. He needs his thumb.’

Sa-at watched the beak hover, then tap an index finger.

‘No.’

This time the beak came to rest on Tal’s eyelid.

‘No!’ Sa-at tugged at Tal’s earlobe. ‘This bit?’

Crowflies shook its head.

‘What about both of them?’

There was a pause, then Crowflies nodded. It worked its head into the hole in Tal’s jacket, paused, then stabbed into his armpit. Sa-at saw the Birdkin’s throat swell as its proboscis thrust out.

Tal called out in pain and tried to twist away but Sa-at held him down while Crowflies worked.

The red-tinged sky faded to grey and then Crowflies pulled back, something trapped and wriggling within its beak. The Birdkin regarded the thing’s tiny legs with interest. There was a crunch and a small but audible pop, and the wriggling stopped. Crowflies tipped its head up and swallowed.

‘Did you stop the blood?’ asked Sa-at.

Crowflies gave him a look.

‘Thank you.’

He turned away while Crowflies took its due, only turning back when the wounds were pinched closed. Both earlobes were gone, snipped away so smoothly it was as if they were never there. Tal was groaning and muttering to himself, though his eyes were only half-open. It seemed as if his body were awake but his mind still lurked in some dream. He allowed Sa-at to pull him up and lead him stumbling the way the group had gone.

It was fully dark when they reached Sagan.

There was a space where there were no trees and the ground was scorched black by old fire, abandoned land that bridged the gap between the edge of the Wild and the fences and fields where Sagan began. Lights burned orange along the tops of the fences, and as Sa-at pushed Tal towards them, he heard people shouting.

‘Over here! I see Tal! I see Tal!’

More of the lights began to move, until they had picked Sa-at from the darkness. He squinted his eyes against the sudden glare and waved. Tal raised his hands over his face and groaned.

‘He’s in pain! And what’s that feathered thing next to him?’

Sa-at tried to think of something to say but, again, the words would not come.

Others were speaking though. ‘Something has him!’

‘Don’t let it take Tal!’

There was movement at the fence, though Sa-at couldn’t make out what it was. He wanted to say his name the way the Gatherers had back in the Wild. That he was Sa-at and he was safe. And then they would smile at him and touch his arm. He wanted it so badly but he could not find the words. It was as if all the breath for speaking had fled his body.

So instead he smiled and gave Tal a gentle push towards Sagan. The young man managed several awkward steps before tripping and falling over.

‘It’s killed Tal!’ shrieked a voice.

‘Get it!’ shouted another.

A stone landed in the dust by Sa-at’s feet. Then another. He held up his hands in surprise and felt something sharp smack into his palm. It stung and he cried out.

‘Good shot, Rin! Keep at it.’

He took a step back as another stone hit his shoulder. That stung too, and his eyes pricked with tears.

Fear overcame shock, making him turn and run. The stones and shouts followed him, back across the barren ground and into the dark of the Wild.

Satyendra strolled across the courtyard, slowing as he reached the centre. On cloudy days this was his favourite place in the castle. An open space as far from the oppressive walls and the hated crystals as it was possible to be.

It would be even better if there was nobody else here.

He was good with people, but they brought out the worst in him, and he often wished he had been born elsewhere. A quiet settlement on the edge of a Godroad, or one of the watchtowers on the border where he’d only have the landscape for company. Within the confines of Lord Rochant Sapphire’s floating castle, privacy was hard to come by.

Some of the apprentice hunters were playing ‘snare the demon’, a game in which one person was the titular demon and had to get from one side of the courtyard to the other. The other players were the hunters, and their job was to grab the demon. If three hunters got hold of the demon at once, they won.

When they saw Satyendra they called out to him, begging that he join them. It had always been like this. As the Honoured Vessel for Lord Rochant Sapphire’s next life, he was special, elevated above the others. Everyone wanted to sit next to him at mealtimes or pair up with him while training. He was an auspicious being, a lucky charm, and they loved him for it.

Almost as much as he loathed them in return.

Apparently, he had impressed even as a baby. He was born under the same alignment of the suns as the Sapphire High Lord, Yadavendra, and had impressed the man so much, that he had been gifted with a name of equal status and length as the other high lords. Clearly, Yadavendra had low standards. As best Satyendra could tell, he had been honoured for not crying. His mother always went on about how quiet and brave he was as a baby. How ridiculous. They praised me because I did nothing. That’s no achievement. Perhaps they’re hoping I’ll be just as quiet at the end, when I’m sacrificed for the good of the house.

And with the next proper alignment of the suns only a day away, the end seemed far too close for comfort. He had to find a way to postpone.

One of the apprentices moved into his path. Though he’d known them all for years, in his head he referred to them by feature rather than name. This apprentice was called Pik, but he had dubbed them Nose, for obvious reasons. ‘Want to play, Satyendra?’

He buried his irritation deep, and put on a mask of reluctance. ‘I’d love to but Story-singer Ban is expecting me.’

‘Just one game, please.’

‘Please!’ echoed the other apprentices.

‘I don’t know. He won’t like it if I’m late. Lord Rochant was known for his punctuality.’

His primary duty as an Honoured Vessel was to be like a mirror to Lord Rochant in thought and deed in order to enable an easy rebirth. It was implicitly understood that everyone in the castle was supposed to assist him in this, and for years Satyendra had been using it to his advantage.

As he expected, the apprentice hunters backed off, disappointment plain on their faces, and, for a delicious moment, their shared sadness washed over him, like the scent of cooking from another room, making his mouth water. A secret part of him stirred, and demanded to be fed.

I should move on, he thought. Ban hates it when I’m late, and if I play, I’ll need to win.

There was a terrible pressure in being Lord Rochant’s Honoured Vessel. For it seemed Rochant had been hatefully good at everything: flying, tactics, lawmaking, diplomacy, hunting, art. His legacy was like a shadow that dwarfed Satyendra’s achievements. How was he supposed to match somebody with lifetimes of experience? Somebody known for their wisdom. Who never lost.

It was impossible. Better to sidestep the issue of the game entirely and go to his lesson.

He walked on a few paces, pretending reluctance, before stopping. It was too late. He wanted to feed. Needed to. He would play and win and make them sad. Then he would drink it in. The plan had already formed, any flaws hidden by an irresistible need. His back was to them now and he could not help but lick his lips in anticipation.

‘Could I play the demon?’ he asked.

‘Of course,’ they replied, a little eagerness returning to their eyes.

He made a show of thinking it over. ‘I suppose I could stay for one game, but it would have to be quick.’

The apprentices rushed to their starting positions, spreading out across the courtyard, while Satyendra walked to the far wall.

‘Ready?’ they asked.

‘Yes,’ he replied, then, as they started to run towards him, added: ‘No. Which demon am I going to be?’

The apprentices stopped, confused. One of them said, ‘What?’

‘I need to know which demon I am.’

Though the game did not normally require the demon to be named, all of the apprentice hunters had grown up being taught about the inhabitants of the Wild. Suggestions came thick and fast:

‘Be one of the Red Brothers.’

‘Be a Watcher!’

‘Be a Kindly Father!’

‘Be the Stranger!’

‘Be Murderkind!’

Satyendra shook his head. ‘No, I’m going to be the Scuttling Corpseman.’

‘But, the Corpseman is dead,’ replied Nose. ‘Lord Vasin killed it.’

‘No he didn’t, he cut off its arm, and anyway, this is a game so I can be who I want. Be careful though,’ he warned, ‘the Corpseman kills any hunter it catches alone.’

While they were digesting that, he started running down the left side of the courtyard, and with a whoop, they came after him.

Most of the apprentices were full grown, with adult frames that hadn’t yet filled out, and faces that still contained an echo of childhood. At seventeen, Satyendra was not the fastest nor the strongest of them. He was small like his mother, but he had her steel, and one other advantage. For Satyendra was different. Not just because of his status but because of something deep inside him, something fundamental. He didn’t understand why or how, but he knew, in a way that he never articulated, that something inside of him was twisted.

As far as he could tell, the majority of people in the castle did not lie. It did not even occur to them. For Satyendra, deception was a part of everyday life. Every pleasantry was a lie. Every smile. Every kind word. It was a daily necessity to keep his secret. A lifetime of practice had made him the best deceiver in the castle.

And so, in the game, he lied. As he approached the first pair of apprentices, his body told them he was going left, and when he went right instead, they were wrong footed. He used the same trick on the second set. The third set were expecting a feint, they watched his eyes instead of his body.

They might as well scream their plans at me, so bright is it on their faces.

He told them with his body that he was going left, but hinted with his eyes that he was going right.

They believed his eyes, and he sailed past them.

Too easy!

He was halfway across the courtyard when he heard his mother’s voice from one of the upper windows. He was being called. Pretending not to hear, he put his head down and ran for the finish.

Chunk, one of the older apprentices came charging up behind him. Satyendra tried to weave to throw her off, but she was so much bigger and so much faster that it didn’t matter.

All he had to do was keep going a little further. The wall grew larger in his vision. Under the clouds, the sapphires set in the stones seemed dull and dark.

Just a few more steps!

The more it looked as if he was going to win, the more he could feel the frustration of the other apprentices, like a dam about to break. He wanted the sadness underneath, he needed it.

As his pumping arms swung out behind him, he felt a hand close on his wrist.

‘Got you!’

No!

Chunk pulled him backwards, away from the wall. His fingers had come tantalizingly close, another inch or two and he would have won. They skidded together, both working hard not to fall or get their legs tangled.

Satyendra could feel his momentum being stolen and it enraged him. He had to win!

‘I’ve got him!’ she called.

He twisted to get free but her grip stayed firm. When he tried to drag her towards the wall she simply leaned back and he was unable to shift her weight. The other apprentices were running over. If any two of them got their hands on him then he would lose the game. Their frustration had vanished, their sadness become like a memory of mist. His hunger clawed at him.

His mother’s voice called again, louder this time.

Neither of them paid the Honoured Mother any attention. Chunk grinned at him and he grinned back.

He was still smiling as he pressed his foot against the side of her knee and pushed. Braced as her leg was, it was easy for him to pop out the joint.

Her smile vanished into a scream.

The mix of surprise and pain was heady, and Satyendra drank it in. Their suffering like a physical thing, nourishing. Around him, everything came into sharper focus. He felt more alert, more alive. It was as if he’d been in a desert and forgotten how sweet water could taste. A part of him knew that this was going to make trouble down the road but when the rush was on him it was hard to care.

Her grip on his wrist was still strong, the shock making her squeeze even tighter. It didn’t matter. His strength grew as hers waned, and he broke free easily and took the last step to the wall.

While the apprentices were gathering around Chunk he touched his fingers to the cool stone. ‘I win!’ he declared.

When he turned back the others were staring at him. Most were dumbfounded but three were advancing with violent intent.

They look angry, he thought. Angry enough to forget the rules. Perhaps they were going to actually strike him this time. Let them try! He thought, I can do anything! Though bolstered by another’s pain, he knew that the odds were not in his favour. Behind his bold smile, a worm of sanity crept in, telling him he should apologize or beg, anything to stop the incoming beating. His fear smothered the rush, and the closer they got, the more he wished that he had not put himself in the corner of the courtyard.

His mother’s voice cut across the scene, half speaking Satyendra’s name, half singing it, stretching out the sound into several long notes. The apprentices froze in place immediately as the word seemed to bounce from the walls. Even the sapphires laced throughout the structure began to hum softly, setting Satyendra’s teeth on edge.

He hastily took his hand from the stone. ‘I am here.’

His mother seemed to glide towards them, her icy expression capped off with a delicate frown of displeasure. ‘What is the meaning of this?’

Satyendra assumed a respectful pose. ‘We were playing hunt the demon. The other apprentices didn’t like that I won.’

‘He only won because he cheated!’ exclaimed Nose, pointing at Chunk who was still groaning on the floor. ‘Honoured Mother Chandni, look what he did.’

‘Did you hurt her, Satyendra?’

‘Yes.’

Chandni shook her head. ‘The hunters will be most displeased to hear that.’

‘No they won’t.’

Her expression grew colder still. ‘What did you say?’

‘I said they won’t be displeased to hear what I did. If anything, they’ll be displeased with—’ Satyendra struggled to recall Chunk’s real name and resorted to gesturing instead, ‘the way the other apprentices behaved.’

She made a point of looking at all of the surprised and outraged faces before turning back to Satyendra and folding her arms. ‘Explain.’

‘Of course, mother.’ He looked at Nose. ‘What did I say before we started?’

‘That you were supposed to be having a lesson.’

Chandni nodded to herself. ‘You knew you were late and yet you still agreed to play. That makes it worse.’

Satyendra narrowed his eyes at Nose. The boy was such a dung head. ‘After that. After you’d begged me to play and I’d agreed to one,’ he glanced at his mother, ‘very quick game.’

‘Um, you asked which demon you should be.’

‘Yes, and after that?’

‘You …’ Nose looked up and stared hard at the clouds as if he could make out the suns twirling behind them. ‘You said you wanted to be the Scuttling Corpseman.’

‘And what does the Corpseman do?’

‘Oh! You said it kills any hunter it catches alone.’

‘Exactly. As Lord Rochant says, only a foolish hunter engages a demon alone. That’s why in the game it takes three of them together to tag the demon and win. If we had been in the Wild for true, she –’ he pointed at Chunk ‘– would be dead or taken. She failed once because she thought to take me alone. She failed twice when she let her guard down, and she failed a third time when she allowed me to look into her eyes.’

The other apprentices nodded at that, and some space opened between them and Chunk.

‘And the rest of you,’ continued Satyendra, ‘all failed for not keeping up with her. You should have anticipated her charge and supported it. You let the demon win. When Lord Rochant returns through me, he will expect better than this. We must be ready for that day, mustn’t we, Mother?’

‘Yes. We must strive to be worthy of our Deathless Lord.’ They all hung their heads, though a few still looked angry. ‘And you, Honoured Vessel Satyendra, need to get to your lesson at once, we’ve wasted enough time here.’

‘Might I help my friend first? She is in pain and you have often told me that I need to learn the line between perfection and cruelty.’ Chandni stared hard at him, and Satyendra kept his face innocent and dutiful. ‘I try only to be as firm and fair as Lord Rochant would be.’

‘Very well.’

‘Thank you.’

As his mother returned to the castle, Satyendra crouched next to Chunk. ‘I’m sorry about hurting you before and I hope you can understand it wasn’t personal.’ He looked into her eyes, watching the way his lie slipped into her ear and down to her heart as easily as sweetwine.

‘But you smiled at me,’ replied Chunk, sniffing up some of the teary snot threatening to spill over her top lip. ‘You tricked me!’

‘Yes, which is just what the demons of the Wild would do; trick you into letting down your guard. You know the rules: Don’t let the demon get close, don’t meet its eyes, don’t listen to its voice.’

‘But …’

‘But nothing. The Wild is unforgiving. Our people rely on the Deathless and their hunters to keep them safe. We have to be perfect or we fail. You have to be perfect.’

‘You’re right,’ she sniffed.

‘I am. And I forgive you.’

He felt her twinge of indignation, tasting the moment it fluttered into suppressed anger and shame, all of her feelings served to him on a platter of background pain. It was so good his mouth began to water.

What is wrong with me? Why am I like this?

He put his hands on either side of her knee. ‘This is going to hurt,’ and suns save me I am going to enjoy it, ‘Brace yourself.’

‘Okay,’ she replied.

‘One. Two. Three!’ He gripped harder, feeling her tense in discomfort, drawing out her anticipation for a shade longer than necessary, then popped the joint back into position. Chunk screamed, and Satyendra dropped his head forward, letting his long hair curtain off the rapturous smile.

His blood sang with her pain, his skin rippled with it, the hollow lethargy that usually dogged him replaced with energy and happiness, boundless.

So good!

Under pretence of checking it had gone in properly, he manipulated Chunk’s swollen knee with his fingers. Shivering with the pain elicited from each prod.

Out of the corner of his eye, he noticed Nose was staring. As he looked up the boy jerked his head away too late, too abruptly, to seem casual. Did he see me? Really see me? Does he suspect?

‘That should be fine now,’ he said to Chunk.

‘Thank you, Satyendra.’

‘You’re welcome,’ he replied, standing up with reluctance. There was more to milk here but he dared not risk it. ‘Hopefully they’ll have your back next time.’

Aware that he was already late, he said his goodbyes quickly and jogged off to his lesson with the Story-singer. Running felt good. He needed to work off some of the rush before sitting with Ban. The old Story-singer wasn’t the strongest willed in the castle, but he was no fool either.

As soon as his back was turned to the apprentices, Nose had stared openly, not realizing that his suspicious reflection could be seen in the crystals around the archway.

You see me, Nose, thought Satyendra as he passed through the arch. But I see you. Maybe you’re not such a dung head after all. When I’m done with you, maybe you’ll wish you were.

CHAPTER THREE (#ulink_21a4acb3-5c76-58f5-9a93-ef4aeb91c976)

A bath was waiting for Pari when she reached her chamber, as were servants. The former topped with petals, the latter armed with brushes. A swift and thorough cleaning followed, while Pari tried to collect her thoughts. Always after a rebirth came the horrible feeling of having forgotten something, and this one was no different.

As the servants towelled her dry, Pari considered her body anew. She had asked to be given her granddaughter, Rashana, as a vessel. A perfect match both physically and in temperament, Rashana would have led to an easy rebirth. However, as punishment for going to the Sapphire lands in secret and without permission, she had been given Priti instead, her great granddaughter. Shorter, sweeter, obedient to a fault. The type of girl that would not know an original thought if it struck her in the face.

If the vessel’s body was like a jug, then Pari’s soul was the water. And if the jug did not have room for certain of Pari’s qualities, then they would spill over the edge and be lost.

However, unlike a jug, a vessel could be reshaped, and Pari had seen to it that one of her people visited Priti in secret to complete her education. In the years while she was between lives, he had been working quietly to encourage rebellious thoughts. His name was Varg, and unlike most of the servants, he was not known to the High Lord or any of the main staff. At least, he should not be. She’d had him go in disguise under a false name just to be safe.

Given the ease of her rebirth, she could only assume that Varg had done well. The calluses on her hands suggested her great granddaughter had enjoyed some clandestine climbing, as well as knife work, and she could only guess at the other terrible things he had taught her.

It’s a start, she thought. Though my arms look like they could use some more work.

She would have liked to be a few inches taller too. Such things shouldn’t matter, but they did. She made a mental note to have the platforms on her shoes adjusted accordingly.

Silk was wrapped around her, tight on the arms and legs. Over this was draped a violet gown with loose sleeves and high shoulders that curled to points. A layer of gem-studded jewellery was added to that, and her face was painted; gold around the eyes and mouth, subtler tones elsewhere, smoothing the lines on her face and the youth of her skin, obscuring the age of the body to let the Deathless soul shine through.

A woman sang for permission to enter and Pari gave it. She was dressed in the uniform of a majordomo, tanzanite studs flashing at her throat. Her arrival automatically dismissed the other servants, who hurried away as she bowed deeply. ‘Welcome back, my lady.’

Pari looked at her full face blankly. ‘And you are?’

The woman laughed in delight, sounding briefly like a common child from the settlements below. Pari looked closer, noting that the woman’s skin was made up, that beneath it she was pale for a sky-born. She had clearly spent many years in the castle but had not started life there.

‘Wait,’ she added. ‘I know you … Don’t tell me.’ A number of names skipped through her mind. ‘It can’t be? Ami? Is it you?’

The woman clapped her hands. ‘Yes, my lady.’

They embraced, carefully so as not to upset Pari’s outfit. ‘My dear Ami, it is a delight to see you again. Look how you’ve grown! You were a slip of a girl the last I saw you.’

‘The cook and I are the best of friends,’ she replied with a smile.

‘It is always wise to be on the cook’s good side. I take it you’ve come to enjoy our food.’

‘Oh yes. So much better than what I had before. The Sapphire don’t know what they’re missing!’

‘Spoken like a true Tanzanite.’

Ami lifted her chin. ‘Thank you, my lady.’

‘Inform the High Lord that I will be with her shortly. And send Sho to me, I need to know what I’ve missed.’

‘I …’ Ami’s face folded in sadness. ‘Forgive me, my lady, but Sho is no longer with us. I have taken on his duties in accordance with your wishes.’

Pari looked again at Ami’s uniform, taking it in truly this time. So strange to see someone else in it. She had had many majordomos over her lifecycles, but for the last three, they had all been Sho or Sho’s mother. ‘Of course you have, I remember now. Tell me, did he die well?’

‘Oh yes. He was surrounded by family. They sang him on his way at the end, and we all took part. Even the crystals in the castle joined in.’

Pari closed her eyes, imagining what it must have been like. Tanzanite crystals grew throughout her castle, most of them clustered at its base but some wound through the upper floors and laced the walls. It was their power that kept her castle in the sky, and her people had long ago learned to sing and play music that resonated. It was seen as a good omen when the crystal sang back. ‘I wish I could have been here.’

‘Sho wished this too. He has left you some final words.’

‘Where did Sho get his hands on a message crystal?’

‘I don’t know, my lady.’

Pari smiled. ‘He always was a crafty one. Bring it to—no, it had better wait until after the meeting. Do I look ready to face High Lord Tanzanite? Be honest.’

‘Yes, my lady.’

Pari nodded, feeling the statement to be true. In the Unbroken Age, it was said that there were those that could read the soul inside the body and know another’s intent even before they did. Pari had spent lifetimes trying to master the art, with limited success. She had developed instincts, senses for what another person might feel or do, but they were vague, and often hard to interpret.

‘How long have I been between lives?’

‘Sixteen years, my lady.’

‘Sixteen! I was told it would be fifteen years at most.’

‘Lord Taraka said there were complications with your vessel that had to be smoothed out.’

‘Ah.’ I wonder if that was the fault of my meddling or something else. ‘Is Varg here?’

‘Yes, my lady. He is camped with the courtyard traders to keep out of Lord Taraka’s sight. I know he is eager to speak with you.’

‘I’m sure he is. But he will have to wait. Is there anything else I should know before I meet with the other lords?’

Ami frowned as she considered the question. Clearly there were a lot of things and Ami was struggling to filter them. She’s still too easy to read, thought Pari, adding it to her list of things to attend to.

‘Never mind, Ami. If it isn’t on fire then I will deal with it after the High Lord. Have the others arrived yet?’

‘They are all waiting for you.’

Pari pursed her lips. She was tired from the rebirth but the High Lord was forcing her to attend before she had fully recovered. It was a low tactic. ‘Was this gathering overseen by Lord Taraka, by any chance?’

‘Yes, my lady. How did you guess?’

‘Bitter experience.’

Ami wisely made no comment, instead summoning servants to collect the back of Pari’s gown. It was time to face her peers.

The gentle flow of conversation ended as Pari entered the room. Ordinarily, she would have greeted the other Deathless Lords as they arrived, and granted them permission to enter. Ordinarily, it would be she, the Lady Pari, sitting in the chair opposite the door rather than her High Lord. However, on the day of a rebirthing ceremony, the usual laws were put aside.

She tried not to be hurt that of the six other Deathless that made House Tanzanite only three had bothered to attend her.

‘Lady Pari, welcome back to the realm of life.’ High Lord Priyamvada had stood, and the other two immortals followed a beat after. As was her preference, the High Lord had taken a tall body with an ample frame, the bright gold-violet of her gown a broad block of colour. It made Pari feel as if she was looking at a fortress rather than a person. Priyamvada’s high hat became a turret, and her full-lipped mouth a spout for dropping acid on any foolish enough to get too close.

Armoured in paint, that face gave nothing away. A golden tattoo sat like a star on her forehead, commemorating an old death wound gained long before the rest of the house had their first birth.

‘Thank you for holding my walls and my lands while I was gone,’ Pari replied. ‘Thank you for watching my people and keeping the Wild from their doors.’

Priyamvada gave a slight nod, and sat, allowing everyone else to do the same.

Once Pari’s gown had been properly arranged, the servants bowed and slipped away. She tried to catch Arkav’s eye but he was staring at the floor, his mind elsewhere. Despite the skilled work of his tailors she could see he’d lost weight, sharpening his features in a way she did not like.

Why does he ignore me? It’s as if none of us were here.

Lord Taraka indicated a desire to speak. His body had thickened during her absence, and he too was doing his best to compensate for living in a shorter vessel than his previous lifecycles. The many crystals around his neck tinkled delicately as he moved, before settling again on his bare chest. He was sometimes known as The Holder of Whispers, a literal title as well as a metaphorical one, for each crystal captured any words spoken nearby, and Taraka could make them speak at a touch. It was his job to keep a permanent record of oaths, agreements and indiscretions, to be dug up at the worst possible time. He also did a good line in secrets, holding dirt on everyone in the house save Priyamvada herself.

After he had received a nod from the High Lord, he began. ‘Allow me to add my personal welcome to that of the High Lord, Lady Pari. Your new body suits you well.’

‘You are too kind, my dear Taraka.’ One day, I’m going to enjoy making you suffer. She gave him her best smile to better disguise her thoughts.

‘Though I have brought Lord Arkav here so that he could witness your auspicious return, I regret to inform you that he cannot stay.’

She glanced at Arkav but he remained oblivious. ‘May I ask why?’

‘We are sending him to the Sapphire lands to carry out an investigation.’

‘With what authority do we investigate another house?’

It was Taraka’s turn to smile. ‘Some laws are universal, superseding even a High Lord’s right to govern. When High Lord Yadavendra of the Sapphire destroyed his sister’s Godpiece, he broke a sacred rule and weakened his house, and all of us, forever.’

The major houses, Tanzanite, Sapphire, Jet and Spinel, each held seven Godpieces, while the minor ones, Ruby, Opal and Peridot, held three. Thirty-seven Deathless in all, spread out like a net to protect as much of the land as possible. Yadavendra’s action had reduced that number to thirty-six and left a gap that could never be filled.

‘Has there been a trial yet?’

‘The Council of High Lords has requested Yadavendra’s presence on several occasions, but he has not come. At first he sent representatives, then messengers, and now, silence.

‘For a time, we have been content to wait. House Sapphire was given a generous period to deal with its own affairs but that is drawing to a close. I understand Lord Rochant Sapphire’s rebirth is imminent. If his return does not lead to them taking action themselves, it will be upon us to act, lest more Godpieces be lost.’

‘Forgive me, but the Sapphire High Lord’s crime happened during my last lifecycle. How could we have stood by so long?’

‘It is not our way to rush into things.’ She winced, knowing that he was making a comment about her recent conduct. ‘There was much grief within the Sapphire, we had to let it run its course. We had hoped that Yadavendra would do the right thing, given time to reflect.’ Taraka sighed. ‘He has not.’

‘There’s rushing into another house’s business,’ said Pari, ‘and then there’s procrastinating, and quite frankly we should have—’

Priyamvada’s eyebrows twitched as if contemplating a frown and Pari took a breath. ‘Apologies. The rebirthing has sapped my manners. I meant to say that I find it hard to believe so little has been done.’

‘We could not commit to anything until the other houses had also taken a stance,’ replied Taraka. ‘For that we needed all of the other High Lords to discuss the matter internally, to debate, to question. You know how these things drag on. Yadavnedra’s stance is unprecedented. To counter it, we needed to be of one mind. That accord has taken time. Understand, Lady Pari, that you were not the only one awaiting rebirth in this period. And there have been other concerns. The Wild stirs on the Ruby borders, worse than we’ve seen in a long time. One of their Deathless has been sent between lives, and their High Lord labours under a severe injury.’

‘Sent? Wounded? You mean by things of the Wild?’

‘I’d have thought that went without saying. In her wisdom, our High Lord has ordered the remainder of our Deathless and their hunters to aid the people of House Ruby.’

So that is why the rest of the house did not come to welcome me. ‘The threat must be bad indeed to send so many.’

‘It is. Which is why we cannot afford to have the Sapphire implode on us. Lord Arkav is going to see how things stand there and, if necessary, demand that High Lord Yadavendra return with him to face trial before the council.’

‘But you can’t!’ Taraka put a hand to his mouth in a gesture of surprise, and the High Lord’s eyes flicked to Pari. Even Arkav looked in her direction, though he seemed unfocused still. ‘Yadavendra was willing to exile his own sister. He allowed his people, his innocent people, to be taken by the Wild. There’s no telling what he’ll do to Arkav.’

Taraka laughed as if she’d said something funny. ‘He wouldn’t dare. To harm a Tanzanite would be an act of war. In any case, even if Yadavendra did his worst, we would simply bring Lord Arkav back again. There’s nothing to worry about.’

But Pari knew better. She had seen first hand that there were ways to hurt a Deathless, leaving the kind of scars that followed you from one life to another. She thought of Lord Rochant Sapphire, bound, broken, and alone.

Priyamvada fixed her with a look. ‘Lord Taraka misspeaks, though he is right on one count: Lord Arkav has nothing to worry about, Lady Pari, because you will be with him.’

This is her plan. Either Arkav will bring back High Lord Sapphire, or our sacrifice will be a rallying cry for the other houses, and she’ll be able to replace me with a new, more pliable Deathless. How convenient.

There was an awkward silence that nobody else dared to break. Eventually Priyamvada stood. ‘We will leave you and your brother to catch up, Lady Pari.’ She glanced at Arkav. ‘I don’t need to tell you how important this is.’

‘No.’

‘May the suns illuminate your path.’ And with that, Priyamvada walked out, Taraka following behind like a chastized Dogkin.

She smiled broadly at him as he passed, savouring the way his face puckered like the arsehole of some ancient goat. When the sound of their footsteps had faded away, Pari turned back to Arkav. His silence was like a knife in the guts. She’d known that the brother of old was long gone, his calm and confident nature lost to sullen moods and wild displays of anger, but that was preferable to the absent figure that now sat in front of her.

‘Dear Arkav, what has become of you?’

When he didn’t reply she collected her gown as best she could and moved round to him, lifting his chin with her finger. ‘Arkav?’

He blinked at her, but there was little reaction in his face.

She opened her arms to him. ‘Arkav, it’s Pari. I’ve come back for you.’

Something stirred within him, as if only his body had been awake before. ‘Pari?’

She felt her eyes itch with tears as she nodded. ‘Yes.’

‘Pari!’ he exclaimed as she pulled him close. ‘You’re so far away.’

‘Not any more. I’m right here.’

His arms tightened around her and his voice trembled like a child’s. ‘I was afraid. You disappeared and then when I tried to find you the servants lied.’ His voice became steel, ‘They lied!’ Then childlike again, ‘I went to Priyamvada and she took me and held me in a room and wouldn’t let me go, and then you died and it was so long that I wished I was dead too.’

‘Why would you wish that?’

‘So we could be together. I don’t trust the others.’

Pari gave him a squeeze. ‘Nor do I.’

‘I’m so tired.’

‘Yes.’

‘Can we sleep now?’

‘Yes. Everything is going to be better.’

He drew back from her so that he could look into her eyes. For a moment he seemed just like his old self, as if the Arkav she’d come to know was a cloak and he’d cast it away. ‘Do you promise, sister? I don’t want to be this way any more.’

‘I promise.’