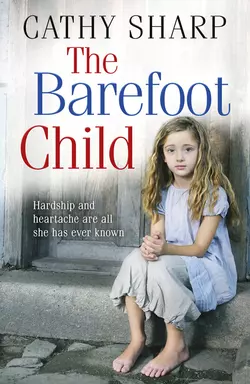

The Barefoot Child

Cathy Sharp

The heart-breaking and compelling new book set in a Victorian workhouse from the author of the The Orphans of Halfpenny Street When Lucy and her brother, Joshua, are orphaned, it falls to Joshua to provide for them both, but he is barely into his teens and in his naivety, falls prey to bad influences and drink. Lucy is desperate to avoid the workhouse, but when Joshua loses their meagre savings they are thrown out onto the street and, in dire poverty, it isn’t long before Lucy finds herself at its gates – almost a fate worse than death. Inside the workhouse, Lucy meets with unkindness and cruelty and she knows she must dig deep within herself if she is to survive, let alone thrive. What Lucy needs is a friend and she is surprised to find one in the most unlikely place…

Copyright (#uf6d309d4-64fc-56fb-a737-0b90c85f94d8)

HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

The News Building

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

First published in Great Britain by HarperCollinsPublishers 2019

Copyright © HarperCollinsPublishers 2019

Cover design by Claire Ward © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2019

Cover photograph © Tanya Gramatikova/Trevillion Images

Cathy Sharp asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008286682

Ebook Edition © May 2019 ISBN: 9780008286699

Version: 2019-03-27

Contents

Cover (#u0a1b980a-825e-5c55-9b10-981064f892b1)

Title Page (#u133331c8-9e4c-55f9-9c1d-50efee863838)

Copyright

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Keep Reading …

About the Author

Also by Cathy Sharp

About the Publisher

CHAPTER 1 (#uf6d309d4-64fc-56fb-a737-0b90c85f94d8)

It was bitterly cold that February morning in the year of Our Lord 1882 and the girl shivered as she shopped in the market, looking for the best bargains to take home for her mother. She’d been given two shillings and for that she must buy a nourishing meal for them all; a meal that would last for several days. Ma had asked Lucy to bring a piece of best mutton and vegetables so that she could make a stew that would be recooked for at least three or four days, ending up as little more than a thin soup, but it was all they could afford.

‘Josh hates mutton stew,’ Lucy had protested. ‘We have it all the time and he says it makes him feel sick.’

‘Please don’t argue with me,’ Lucy’s mother said. ‘My head aches so and I must bake the bread. If you can find another meat as cheap then bring it, but don’t worry me with your brother’s complaints – and Kitty needs new shoes again for her others are falling to pieces.’

It was true, Kitty’s shoes had holes in the toes to allow for growth and Lucy’s sister had been in tears over it the previous day. She’d told her that she must wear them a little longer or go barefooted. Kitty had flounced off to bed, saying she would rather go barefoot than wear them. As usual, these days, Lucy’s mother had blamed her for her sister’s lack of shoes. Lucy knew it was hard for Ma now that Pa was lost, together with all the money he’d invested in his cargo. Life had never been easy but since he was lost, Ma had become bitter and harsh.

Lucy blinked away the foolish tears. She was fifteen, her sixteenth birthday looming in early March, and the burden of looking after her brother and sister had fallen on her shoulders since Ma’s illness the previous winter.

Lucy didn’t mind scrubbing the kitchen floor for her mother before she left for work in the nail factory, nor did she mind preparing her siblings’ tea at night, though she was often so tired she could barely stand. She didn’t even mind that she had to go shopping on her afternoon off, but it hurt that Ma was always sharp with her, always complaining that she was lazy and that she neglected Kitty and Josh when it wasn’t true.

It had never been like this when Pa was alive. Lucy blinked rapidly to keep her tears away. Pa was a big, golden-haired man who seemed to fill the room with his booming voice when he was home from the sea, but he was dead, lost to them all. The sea he’d made his living from had swallowed him up in a big storm and for months they’d known nothing, but then the news had arrived of Storm Diver’s sinking and Lucy had wept bitter tears into her pillow night after night – and her mother had changed from a happy and loving wife to a bitter woman who never smiled.

‘Dreamin’ again?’ Lucy’s thoughts were hastily ended as she found herself confronted by one of the barrow boys who plied their trade in the busy market at the heart of Spitalfields. ‘Dreamin’ of me, I’ll swear – of the day I put me ring on yer finger …’ He was always teasing her, always pretending that he was going to marry her.

Lucy’s cheeks fired as her gaze avoided Eric Boyser’s wicked grin. A thin lanky lad, he wore a rusty black jacket, a threadbare cap, and baggy trousers he kept up with a piece of parcel string. Eric’s jacket was patched and patched again by his widowed mother for whom he worked. Mrs Boyser owned the stalls Eric ran and paid him only a few coins a week – and she didn’t like Lucy’s mother so there was no possibility that she would allow a marriage even if Lucy wanted it, which she didn’t. She was much too young for such things and if she did ever marry she wanted a man like her golden father – not a thin, dark, gangly boy with a long nose who thought it was funny to tease her.

‘I’m not dreamin’ I’m thinkin’,’ Lucy defended herself. ‘I need something to make a good meal that can be reheated for three days – but not mutton. Josh does hate mutton so …’

‘Don’t blame him. I don’t like it much either,’ Eric said. ‘Why not make chicken and vegetable pot in the oven? You can add everythin’ same as a mutton stew and it lasts as long – unless yer eat it all quick ’cos it’s too delicious!’

‘I haven’t got much money,’ Lucy whispered, ashamed. ‘I don’t earn much at the factory and Josh gets less than I do – and Ma’s not been well enough to work since last winter when she had that terrible chill.’

‘Show me,’ Eric demanded and she opened her hand to show him the pennies and sixpences. ‘Two shillings – that’s enough. Todd will have some leftover chicken joints by now and I’ve plenty of veg you can have cheap, lass.’

Lucy curled her fingers over the money. ‘I don’t want charity …’

‘Nay, Lucy, don’t get miffed.’ Eric grinned. ‘Todd alus grumbles as folk don’t want the back and leg joints. He sells the breasts and has to take all the leftover bits for his missus – and his missus Sal won’t use ’em; she wants whole ones to roast so he gives the bits to the stray dogs. He’ll sell you a good big parcel for a bob and you can have sixpence worth of veg from me – last you most of the week, that will.’

Lucy hesitated, nodding shyly, forcing herself not to let pride get in her way. ‘Thank you,’ she said. ‘Chicken would be a lovely change for Josh and Kitty.’

‘I’d do anythin’ fer yer.’ Eric gave her a look that made the colour rush up her pale neck and into her cheeks. ‘Nay, I never wanted to upset yer, lass – but I like yer, see, and one day … well …’ He left the rest unsaid and Lucy warmed to him.

‘Show me where to go,’ she said. ‘I’ll buy the chicken I can afford and come back for the veg.’

‘I’ll come wiv yer, ’cos Todd can be a surly bugger, but he likes me!’ He signalled to one of the other barrow boys to keep an eye on his stall and joined her.

‘Thank you,’ Lucy said, because she hated asking stallholders for their bargains. Some of them just told her to clear off, others made her uncomfortable by hinting that they’d be more than willing to help her if she obliged them – and, understanding what they meant, Lucy always backed away, shaking her head.

She was innocent; and yet, brought up in the rough streets that surrounded the East India Docks, she could not be unaware of the realities of life, of the whores who paraded up and down outside the taverns on a Friday and Saturday night, flaunting their almost naked breasts, hoping to relieve the men of a few shillings from their pay before it all went on drink.

Lucy was a pretty, delicate girl with a pale complexion and fair hair, her eyes more green than blue, and in the summer she got little brown freckles over her nose and cheeks, which she hated. She’d been propositioned more than once when fetching two pennyworth of gin for her mother’s cough of an evening. Mary Soames knew well enough that the gin did nothing for her cough, but it relieved her misery a little and Lucy never refused to do her mother’s bidding, though had Pa been home he would not have approved.

Now, she walked beside Eric to the stall where the big, red-faced butcher was busily chopping up a chicken for a customer. Very few of the women who bought from him could ever afford to buy a whole one for roasting. However, the large boiling fowls that made up the biggest part of his stock were always available and Todd obliged his customers by dividing them into segments. Eric hadn’t quite told Lucy the truth when he said Todd had to take the worst cuts home at the end of the day, because there was always someone willing to pay a few coppers for a parcel of bits and pieces.

‘What do yer want then, little toad?’ Todd asked Eric but the insult was more a caress, because the two were good friends.

‘My friend Lucy wants chicken she can make into pot meals for her family,’ Eric said and gave him a wink. ‘What ’ave yer got fer a bob?’

Todd stared at Lucy for a long moment and then nodded. ‘I’ve got half a dozen backbones ’ere, lass, three thighs, four drumsticks and half a dozen wings. My missus won’t use ’em and I’ll be packin’ up in ten minutes. I reckon yer can ’ave the lot.’

‘Thank you!’ Lucy smiled. ‘Are you sure I can have all that for one shillin’?’

‘Aye, lass, yer can,’ the butcher said. ‘There be some giblets an’ all; they make good tasty gravy or soup and I’ll chuck them in fer nothin’.’

Lucy wondered at his generosity, but the offer was so tempting that she couldn’t refuse, because with the shilling left to her she could buy a small heel of cheese, eggs as well as veg from Eric. Josh did so love cheese, though it was a treat he didn’t often get.

‘You’re very kind, sir,’ she said but the big man shook his head.

‘I reckon you be Matthew Soames’ girl,’ he told her. ‘I remembers him – a good man what did me more than one favour. You come to me every week you fancy chicken and I’ll save me bits fer yer.’

Lucy thanked him, took her parcel wrapped in newspaper, and walked away with Eric, who’d left his stall to the care of one of the other barrow boys. Neither of them noticed the man staring at her from across the road, a gentleman, by his appearance, but with a sour, angry expression that made him look ugly. Lucy paused to buy a small segment of cheese and four eggs from the stall next to Eric’s and by the time she turned back to him, he had a large packet of veg ready for her. He took her sixpence and grinned.

‘I hope Josh enjoys his dinner,’ Eric said. ‘I’m always ’ere, Lucy, lass. If yer ever need ’elp, you come to me.’ The look in his eyes made her blush, but she knew he meant no harm.

Lucy turned for home, her large rush basket heavy over her arm. She had a long walk ahead and it was bitterly cold, but there was a warm glow inside her as she thought of what she could make with her purchases. In her hurry to get home, she did not notice that she was followed. One of her neighbours met her and walked the rest of the way with her. Neither saw the scowling face of the man who turned away, thwarted of his prey.

‘Where did you get all this lot?’ Lucy mother asked as she unpacked her basket, revealing the onions, a stick of aromatic celery, carrots, parsnips, a turnip, a large winter cabbage and three oranges that were in Eric’s parcel. ‘I told you to spend no more than two shillin’s. I need the rest of your wages for the rent or the landlord will put us out on the street.’

‘I spent what you told me,’ Lucy replied, flinching as she received a slap on her ear. She pressed a hand to her ear, looking at Mary indignantly. ‘What was that for, Ma?’

‘You’re lyin’ to me or you’ve been doin’ somethin’ you shouldn’t,’ her mother said harshly. Her thin face was pale and her mouth was pursed in a bitter line. ‘I’ve told you not to ask for charity.’

‘I didn’t!’ Lucy protested, though she knew the butcher had been generous, partly because of her father and partly because Eric had told him she was his friend. ‘The butcher couldn’t sell these bits and he was packin’ up; they wouldn’t keep until Monday.’

‘I’m ill, not a fool,’ her mother said. ‘There’s plenty would buy these leg joints from him – but if he was packin’ up mebbe …’ She frowned. ‘That still doesn’t explain all these veg – and them oranges! It must have cost a shillin’ at least.’

Lucy knew Eric had been too generous, but he liked her and he’d wanted to show it; however, she couldn’t tell her mother that, because she would immediately think that Lucy had let him touch her. Lucy knew it happened. She’d seen it often enough, a giggling girl and her chap in the shadows, and her mother was bound to think the worst, because she’d lectured Lucy about the dangers of letting men touch her, from the day she was ten.

‘I swear I didn’t do anything you wouldn’t like.’ Lucy crossed her fingers behind her back. ‘I swear it on Pa’s memory.’

Her mother’s eyes snapped at her angrily but she said nothing, just turned to take the bread she’d baked from the cupboard in the corner. It was a handsome mahogany piece and Lucy had noticed their neighbour look covetously at it when he’d first seen it. Lucy’s father had brought it home from one of his voyages abroad and she thought it must be worth a few pounds, but Ma would never sell it. They managed to pay the rent for their cottage and live on the money that she and Josh earned, though it was little enough, and none of them had had new clothes or shoes since Pa was lost.

‘You can start on the casserole,’ Mary Soames said, intimating that the discussion was over. ‘We’ll all have a piece of bread toasted with cheese when Josh gets back. It’s a treat and I haven’t tasted cheese in months!’

Lucy turned away with a sigh. She’d hoped to make Josh cheese and pickles in bread for three days out of that cheese, and now it would be gone in one go. It wasn’t fair, because Josh had to work so hard and he brought every penny home. He didn’t like the penny dripping that Lucy bought from the butcher in Commercial Road, so often took just bread for his midday meal. Most men and boys spent at least half their wages on themselves, often on drink. Josh wasn’t old enough to go drinking after work and that cheese was meant to be his treat, but Lucy couldn’t defy her mother. Tears stung her eyes; she understood her mother was ill, but she longed for a warm smile or a loving touch.

‘I won’t wear them anymore,’ Kitty cried throwing the offending shoes at her sister later that evening. ‘They make blisters on my heels and they let water in!’

Lucy saw the shoes were beyond repair. ‘I can’t afford to buy you a pair this week, Kitty,’ she said. ‘Will you not wear them until I have saved enough?’

‘Why should I?’ Kitty demanded, her mouth wobbling. ‘Pa would never have let me wear them knowing they hurt my feet.’

Lucy knew her father would have sold something of his own to buy new shoes for his daughter. Lucy wracked her brain, but there was nothing she owned of any value. There was nothing she could do but sell her Sunday shoes to buy her sister a decent pair of boots. It would leave Lucy with just her working boots, which were stout and well-protected, with iron studs in the soles and heels, but she had saved her pennies for months to buy her Sunday shoes – yet she had no alternative for her mother said it was up to her as the wage earner to provide shoes for Kitty.

Lucy took her shoes to the market in the fifteen minutes she was given for her lunch break the next day. She looked at the shoes on offer and saw a pair in red leather that were just Kitty’s size and red was Kitty’s favourite colour.

‘How much for those?’ she asked, pointing to the red shoes.

‘They’re fine shoes for a young lass,’ the man said eyeing her eagerly. ‘Hardly worn, they be, miss – and cheap at seven shillings the pair.’

Lucy held her breath because it was so much money and she wasn’t sure he would give her as much for her own shoes. Yet perhaps he would hold them for her and Lucy could pay a few pennies a week until she had enough.

Taking her own Sunday shoes from under her shawl, she showed them to the stallholder. ‘What will you give me for these?’ she asked. She had bought them six months earlier for five shillings from another stall and had had them repaired once.

‘Three and sixpence,’ the man said. ‘It’s a fair price. I doubt you’ll get more.’

‘I wanted to exchange them for the red ones – for my sister …’

He laughed mockingly. ‘Think I’m a fool do yer – clear orf and don’t bother me until you can pay!’

Lucy turned away, feeling the despair wash over her. Why did life have to be so hard?

‘Wait up!’ the man called after her and Lucy hesitated, turning back in dread for she feared what he might say. ‘I’ll take them shoes and the boots on yer feet – and you can have the shoes for another sixpence …’

About to shake her head, Lucy remembered that there was a spare pair of her father’s working boots in the cupboard under the stairs. They would be miles too big for her, but she could stuff the toes with newspaper and they would do. She would not be the only girl at the factory to wear her father’s old boots.

She bent down and unlaced her boots, handed them, her best shoes and the last sixpence from her purse, and took the red shoes, wrapping them in her shawl as she walked away. The cobbles were hard beneath her feet and small stones pricked at her, making her wince. She began to run home, knowing that she must find her father’s boots before she could return to work, because it would be too dangerous on the floor of the nail factory with bare feet.

‘Oh Lucy!’ Kitty swooped on her and kissed her when Lucy returned from work that night. ‘My shoes are lovely. They fit me perfectly, with a little room to grow in the toes.’

‘Good, I’m glad.’ Lucy sat down wearily. Her own feet hurt, because her toes had pressed against the newspaper all day and it was harder to work in the heavy boots that had once been her father’s. They were stout and protected Lucy’s feet from the discarded and broken metal on the floor of the nail factory, but the paper chaffed and her big toe was bloody under the nail. She would need to wear a pair of Pa’s old socks over her own in future to protect her feet.

‘Lucy, what’s for supper?’ her brother asked. ‘I’m hungry.’

‘It’s on the stove,’ Lucy’s mother said and looked at Lucy’s feet, shaking her head. ‘Where did you get those, Lucy?’

‘They were under the stairs,’ Lucy told her and wriggled her toes as she took them off. She would rather be barefooted than wear them except when she had to and as soon as she could she would buy some boots that fit her properly, but it would take her months to save for them.

‘Lucy – did you sell your boots to buy my shoes?’ Kitty’s eyes widened in surprise and she looked a little ashamed.

‘And my Sunday shoes,’ Lucy said. ‘Make sure you take care of those, for it will be a long time before I can buy new again …’

‘Oh, Lucy,’ her mother said and shook her head, ‘why did you not ask me? I have a spare pair of boots in my cupboard. You might have sold those instead.’

Lucy said nothing for she knew that had she asked her mother would have refused. ‘Pa’s old boots will do for work,’ she said. ‘I shall save up until I can buy some new ones.’

‘Well, I think you are very foolish,’ her mother said. ‘Return to the stall tomorrow and see if he will change your boots for your father’s.’

Lucy nodded, acknowledging the sense of her mother’s words. She would pop back to the stall in her lunch break again and ask if he would exchange them for her.

Lucy stared at the stallholder in dismay. He had sold her working boots almost as soon as she’d left the stall the previous day, he said.

‘I’d buy those boots,’ he told her pointing to her father’s boots. ‘I’ll give you five shillings for them – if there’s anythin’ on the stall you want.’

Lucy looked but there was nothing to fit her save her Sunday best shoes, which were now priced at seven shillings and beyond her.

‘I’ll leave it for now, thank you,’ she said, ‘but when I’ve saved a bit I’ll come back and exchange my boots for something that fits me better.’

Turning away in disappointment, Lucy knew her boots hardly showed beneath her long skirts, but they felt uncomfortable and she would rather be barefooted, but if she injured herself at the factory her family would starve. For the moment she would just have to put up with the discomfort and take them off when she got home.

‘Here, have these instead,’ Lucy’s mother said, handing Lucy a pair of her own boots; they were scuffed and worn but almost fitted Lucy. ‘They are still too big for you but better than your father’s old boots.’

‘The stallholder said he would give me five shillings for Pa’s boots,’ Lucy said and saw her mother’s eyes light up.

‘Then wear mine, sell your father’s boots – and give me the money.’

Lucy hesitated. Her mother’s boots were almost worn through at the soles, but if she stuffed layers of paper into them they would last for a while and fit better. If she could keep the money for Pa’s boots she could have them repaired – but she could not refuse to give her mother the five shillings.

‘Thank you,’ she said. ‘That was a kind thought, Ma.’

‘You shame me going about in a man’s boots,’ her mother said harshly. ‘Besides, I could do with that five shillings …’

Lucy turned away biting her lip. She’d thought her mother’s concern was for her but it was merely for appearances.

CHAPTER 2 (#uf6d309d4-64fc-56fb-a737-0b90c85f94d8)

‘Well, Hetty, shall you like it here?’ Arthur Stoneham asked of the woman he’d appointed as the new mistress of his house for destitute women and children. The cook he’d brought from the workhouse when it was first opened had surprised everyone by finding herself a husband and leaving and Ruth had taken over the cooking, relieved to hand the book-keeping to another. ‘Your rooms are perhaps a little spartan but I daresay you can make them more comfortable?’

‘I’m sure I shall be comfortable.’ Hetty Worsley smiled at the attractive and charismatic man, who had spent hours persuading her to take on this job. ‘My rooms are easy to transform, Mr Stoneham – but you’ve set me a much larger task.’

‘All it needs is kindness mixed with firmness and common sense, which you have in abundance,’ Arthur insisted. ‘And no formality – I’ve always been Arthur to you, Hetty.’

‘But that was when I held you in my arms and let you rant out your grief,’ Hetty said, reminding him of the days when she’d been a whore and he’d sought comfort from her because of his tearing grief over the woman he’d loved and lost. ‘If I am to be mistress here, I must show respect.’

‘I’ve always thought you one of the finest women I know. What fate made you once is of no importance. You changed your life to one of respectability, and it was your kindness to me – and your wisdom – that made me ask you to take on this post. These women and children have been sorely mistreated by life, Hetty.’ Arthur sighed. ‘I had hoped that you might take over the workhouse in Whitechapel and I fought for it, but to no avail. The woman the guardians chose is no doubt respectable, but I doubt she has any kindness in her. She will rule with a rod of iron and her husband is a careful man and, I fear, under her thumb. I do what I can to ease the life of the inmates there – but here I am determined that they shall be treated decently.’

‘You have shown trust in me by bringing me here and I shall do all I can to earn it.’ Hetty smiled. At three and thirty she was past the first flush of beauty and youth, but there was a sensual warmth about her smile and her figure was still as trim as when she had given Arthur the love and trust he’d needed to regain his self-respect all those years ago. ‘What exactly do you want to provide here, Mr Stoneham?’

‘Firstly, their basic needs of clean beds and clothes and good food. The children need to be taught at least the beginning of arithmetic and writing, so often denied them by the workhouse because the guardians believe they need only know how to sign their name and learn how to work. Some of the women may wish to find honest employment once they have a home – and my friend, Miss Katharine Ross, has offered to give any who wish for it, instruction in needlework. She may also assist you in educating the children.’

The look in his eyes told Hetty that Katharine Ross was special to him, and she was glad of it, because she better than anyone knew the remorse and regret that lived inside him.

‘I am partial to good cooking myself,’ Hetty told him firmly. ‘You can rely on me to make sure that our people are fed properly.’

‘Then, I think I can safely leave you to settle in,’ Arthur said. ‘Good luck, Hetty – and I hope you won’t hate me for taking you from your comfortable home.’

‘It was not as comfortable as you suppose,’ Hetty said, her voice reflecting humour. ‘When the school I worked at closed, I took a post as a housekeeper and my employer imagined that, as his housekeeper, I should also warm his bed, which I declined.’

‘And how is your daughter?’ Arthur asked, preparing to take his leave. He was smoothing his gloves between the fingers and did not see the sudden wary look in her eyes. ‘I trust she thrives at that expensive school you sent her to?’

‘Oh, yes, Sylvia does very well,’ Hetty told him and smiled as he turned to her. ‘She is intelligent, and I think she will go on to achieve something worthwhile – perhaps become a teacher or a nurse like Miss Nightingale.’

‘If your daughter is as beautiful as her mother, she will marry well,’ Arthur said but Hetty shook her head.

‘Sylvia shall not be dependent on any man, Arthur. I want her to be independent and earn her own living in a way that gives her respect.’

‘You do not want her to marry?’

‘Perhaps, if she could marry the right sort of man – but how likely is it that she will?’

‘When the time is right, I could help her to mix in the right circles …’

‘The daughter of a whore and an unknown father?’ Hetty’s eyes flashed a challenge at him. ‘I do not think that would wash well with your high society friends, Arthur.’

‘I have other friends. I would help you and your daughter achieve whatever you asked, Hetty – but I know well you will not ask.’

‘I’ve won my independence, Arthur,’ Hetty said. ‘It was hard won and I would not give it up for any man – even you.’ That last was a lie, but she would never permit him to see her true feelings, because his heart belonged to another.

Arthur laughed and took his leave of her. Hetty smothered her sigh and went through to the bedroom where three trunks had been deposited. Arthur would never learn the truth of Sylvia’s birth from her, or that she herself was entitled to hold her head high as the daughter of a gentleman. Hetty had never asked for favours since a man of high birth had spat in her face and told her to find her own way in the world. Disgraced, alone, and with only a few shillings to her name, Hetty had chosen the only way she knew of surviving – but she was determined that her daughter would have a better life.

Sylvia had been given a good education and she would grow up to be respectable; and if she married, it would be to a working man who respected and loved her.

Hetty knew that Arthur Stoneham had once wronged a woman, but he had been young and careless and, afterwards, he’d tried to repair the damage but it had been too late – and for that he’d never forgiven himself. The man who had wronged Hetty was cruel and took pleasure in her downfall, but with Arthur’s help she had won back her freedom and her self-respect. For that she loved him, though he did not know it and never would. She smiled a little wryly as she began to unpack her things. It was a huge task that she’d taken on to please Arthur Stoneham and she only hoped that she would manage it well.

‘So, my friend,’ Toby Rattan said as he met Arthur that evening in the exclusive gentleman’s club they frequented. ‘Is it all settled – is Hetty installed as the mistress of your refuge?’

‘Yes, and I think she is happy enough,’ Arthur said. ‘I shall send her a few things she might like to furnish her rooms with; Hetty Worsley is a woman of sense and she will make it her home for the foreseeable future.’

‘You do not think she will end her days there?’

‘I very much doubt it – nor would I ask it of her,’ Arthur said. ‘I hope she will find content in marriage one day, but first she may make the lives of others happier.’

In recent months Toby had taken more interest in such affairs, though he’d given up in disgust at the intransigent guardians of the workhouse, who had installed a harsh-looking woman and her husband to run the workhouse in Whitechapel.

‘And as for that block of ice they installed at the workhouse …’ Toby’s voice trailed off in revulsion. ‘She has not an ounce of humanity in her.’

‘I think in some ways she may prove worse than Joan Simpkins – though I do not accuse her of the vile crime of selling children into whorehouses.’

‘Then she will suit your fellow guardians, Arthur, for they are a harsh lot, despite their good works. Some of them probably think you are too lenient towards the poor, for you give and expect nothing in return.’

‘Yes, I dare say,’ Arthur said wryly and twisted his delicate wineglass, watching the way the glass spiralled up the stem. ‘A good vintage, this claret, Toby. I had some of it last Christmas from your father. How is he these days?’

‘A little better again, I think. His chest was bad with the bronchitis this last winter, as you know, but I think he makes progress now. I certainly pray for it.’

‘Yes, I imagine you do,’ Arthur acknowledged. Toby and Arthur’s friendship went back years, since their schooldays, and they had remained friends even through the years of Arthur’s wilderness, when he had lost himself in drink to forget the wrong he’d done a gentle girl, Sarah, the girl he ought to have married had he not been too young and arrogant to see it; Sarah, who had borne his child. He’d paid for his arrogance with regret after she’d died and now suffered from uncertainty over what to do about the young girl that he believed to be his daughter by Sarah.

He’d rescued Eliza Jones from the fate that Joan Simpkins had planned for her – well, Eliza had, in fact, rescued herself from an evil man by her own ingenuity, escaping to the protection of a young gipsy boy with whom she’d formed a friendship, but with the shadow of murder hanging over her. It had been Arthur’s duty and pleasure to find her and tell her that she had merely stunned the man who had sought to defile her, and that he had been arrested for his vile crimes.

Eliza had allowed him to take her back to Miss Edith, the apothecary with whom she lived now. She was learning that profession and helping Miss Edith, who was unfortunately ill much of the time. Now sure that Eliza was his daughter, Arthur felt unable to claim her. She was doing well, despite her unfortunate beginnings in the workhouse, and seemed happy in her new life, though he seldom visited. Arthur longed to give Eliza gifts of pretty clothes and trinkets of value, but knew he must not, for it would be misunderstood.

‘Well, are you planning to attend?’

Arthur’s thoughts had strayed and he suddenly became aware that Toby was addressing him. ‘Forgive me; my mind was elsewhere.’

‘I was asking if you intended to accompany me tomorrow evening, to the lecture about the situation in the Transvaal and where the end of the Boer War leaves us as a nation.’

‘Ah, yes, I remember you had an interest in that business. Your father has some financial concern out there, I think?’

‘He bought shares in some land, which was to be used by the railway – but now he thinks British interest is lost to the Boers and his investment will be sunk.’

‘I daresay,’ Arthur said. ‘It was, in any event, a risky investment for your father, Toby. Look what has happened here – they said the railway would be a blessing but with all the fatal accidents we’ve had since they were built I sometimes wonder if we should have done better to stick to horses.’ The coming of the railways had changed the face of England, destroying with their noise and the bustle of the traffic they brought, the tranquillity of sleepy country towns that had existed for centuries. ‘Would it really be feasible in Africa with all its problems?’

‘I think it may be the only way to conquer its vastness.’

‘Yes, perhaps …’

‘Queen Victoria herself approves of the train as a form of transport. Besides, the railways will be a big help to the poor in time.’ Toby was insistent. ‘My father is certain of it. It enables men to seek work further afield and thus alleviate some of the hardships when work is scarce in the country or the mines, which has often resulted in starvation in the past – and food can be brought fresher to London. That must be of benefit even to you.’ His eyes twinkled with good humour.

‘And what of the overcrowding it brings to towns, the noisome slums created by the sheer force of people who have nowhere to live?’

‘We must simply build more homes and do away with the rookeries of these slums,’ Toby said. ‘Come now, you must see some benefits?’

‘Food is fresher brought in by train, I admit. Yet I still prefer to travel by horseback,’ Arthur said thoughtfully. ‘I like to be in control and not at the mercy of some drunken fool of a train driver as I heard was the cause of one recent accident on the railway.’

Toby could not argue with that. ‘As it happens, I have heard of a pair of greys I believe you might like; shall we take a look together?’

‘Yes, why not?’ Arthur raised his glass. ‘It would be amusing – and goodness knows we need something to cheer us all up.’

‘Speaking of which, have you seen Miss Katharine recently?’ Toby asked with an air of studied innocence. ‘I understand she intends to have herself appointed as one of the governors of your workhouse.’

‘It is not my workhouse, God forbid,’ Arthur said and frowned. ‘If it were, I should make changes instantly and not have to argue for months over something fundamental, like a new water closet for the women.’ Only a few years earlier cholera had been rife in the crowded towns, but a new system of fresh water, piped daily, had improved the health of many. Arthur had personally paid for new pipes at the workhouse in Whitechapel. He nodded thoughtfully now. ‘I understand Katharine is taking a keen interest in such things these days, but I have not encouraged it. Her aunt wishes her to marry advantageously – in fact, I rather think she has her eye on you as a suitable husband for her niece, Toby.’

‘Well, her aunt may look at me,’ Toby countered mischievously, ‘but I believe Miss Katharine is more inclined to glance your way, Arthur!’

His friend did not answer. He’d asked Katharine to marry him some months earlier and she had intimated that she might, but had told him he must court her to win her aunt’s approval. He had since accepted invitations to dine and to social evenings that bored him stiff, but although Katharine teased him and flirted with him, she had not yet given him any reason to believe that she was ready to be proposed to a second time. She was disappointed that, as yet, despite engaging agents, he had found no trace of her sister, Marianne, and seemed to blame Arthur – yet she had always known it was unlikely her sister could be found after nearly thirteen years.

‘I think Katharine’s aunt has taken a dislike to me.’

‘Ridiculous,’ Toby retorted. ‘I don’t know what murky secrets lie in your past, but I do know that you have atoned for them many times, my friend. If you care for Katharine, you should tell her – before it’s too late. I must warn you, Sir Roger Beamish is very interested and I think her aunt is pushing Katharine his way.’

‘Beamish is a cad and worse!’ Arthur exclaimed, indignant that a man he thought beneath regard was pursuing the woman he desired above all others. ‘That brute is not worthy of her. I have not spoken to him since I caught him cheating at the card table.’

‘Then do something about it.’ Toby finished his wine and stood. ‘I am for my bed – do you care to share a cab with me or shall we walk?’

‘It’s a fine night, let us walk,’ Arthur said and took up his walking cane, which had a fine silver knob and was also a sword stick, used more than once against rogues who had tried to rob him. ‘We’ll come to no harm …’ He brandished his stick and Toby laughed, for he, like Arthur, was ready for an adventure if one should come their way.

Arthur was aware that the contrast between his exclusive club and the dining room of the workhouse he visited the following morning could not have been more marked and he took a keen interest in all that he saw, listening to Master Docherty’s anxiety concerning the roof above the long dining hall intently.

‘I fear the roof has been patched so many times that one big storm might bring it down,’ the workhouse master told Arthur. ‘And I do not believe that the present budget will stretch to a new roof, sir.’

‘Nor I,’ Arthur replied. ‘Leave it with me, Docherty, and I shall request some advice regarding the cost.’ It would not be easy to convince the governors that more money was needed for the upkeep of the workhouse, and Arthur was aware that much of the cost of a new roof would fall on him. However, to leave it much longer would be to risk it giving way in the first storm.

The men had already eaten their meal and left to get on with the work they did here at the workhouse. Several of them recognised Arthur and tipped their heads to him, though a few had looked at him resentfully. Now the women and girls were coming in to take their places at the long tables. Once, the inmates had all been served together but the new mistress preferred that the women and girls eat separately but he noticed that some whispering went on as the two groups passed at the door.

Arthur watched as the women quietly took their places, voices low and respectful. He watched the women serving the meal and noticed one elderly woman in particular. She wore a grey puritan bonnet, a grey wool dress and a white apron, much as the other women, but there was something about her that was different. As Arthur watched, seeing the hands, misshapen and gnarled with age, she lifted her head and looked at him – and then very deliberately winked before returning to her task of ladling out stew into the enamelled plates.

‘That woman is a little old to be working, isn’t she?’ Arthur murmured to the warden beside him.

Master Docherty looked at her and frowned. ‘That’s old Moll,’ he said. ‘She is old, but stronger than you’d think. I imagine she’s had a hard life, though I know little of her. She turned up a few weeks ago and said she’d decided to come in because she was ready.’

Arthur nodded. That wink had told him that Moll had more spirit than most of the inmates. If she was ‘ready’, then she had quite probably decided that she would come here to die. Many of the older folk did that once the struggle for life outside became too hard.

‘Take care of her,’ he said to Master Docherty. ‘It won’t hurt her to do light work if she’s up to it – but give her a few extra perks, please, and I will reimburse you for them.’

‘Certainly, sir,’ the master said and nodded. ‘I rather think Moll enjoys her beer. An extra ration at night now and then won’t hurt.’

‘No, indeed,’ Arthur said and smiled. ‘Well, Master Docherty, I shall see what can be done about your roof. I congratulate you on the cleanliness of the place. It is a vast improvement on what it was.’

‘That is down to my wife,’ the master said, looking pleased. ‘Mistress Docherty is a good woman and will be sorry to have missed you, sir, but she was called out to visit an elderly couple. They cannot manage now he is too old to work but they are reluctant to come in.’

Arthur nodded. There was a stigma about the workhouse and few would willingly come in, unless they had good reason like Moll, who, he was almost sure, had come here to die in a bed rather than on the streets.

Arthur took his leave. Some young lads were sweeping the yard as he crossed it and one of them grinned, doffed his cap and bowed. ‘Do yer need someone to ’old yer ’orses, sir?’

‘I’m walking today,’ Arthur said and smiled. Taking a shilling from his pocket, he tossed it to the boy. ‘Come to me when you’re fifteen and I’ll see what I can do …’

‘Jem Carter’s me name, sir!’

Arthur smiled as the lad caught the shilling and called out his thanks. Some it was easy to please, for others there was little he could do …

CHAPTER 3 (#uf6d309d4-64fc-56fb-a737-0b90c85f94d8)

It was spring, now, and the weather was beginning to get warmer. Her mother was dead and Lucy felt the weight of sorrow heavy on her shoulders. A few weeks before she died, her mother had called Lucy into the bedroom and told her that her time was short.

‘I’ve done my best by you since your father died, but have little to leave you,’ she’d said tonelessly. ‘My sister would have you, but she is a harsh woman and I think you would find it unbearable to live in her house. I have written to your father’s only relative, Mr Stoneham, care of his lawyer, telling him that I am dying, but he has not replied. You must care for your brother and sister – for I can do nothing more.’

Lucy had wept bitter tears in her own room but knew she must be strong. She was now sixteen but earned only a few shillings each week and knew that it would be hard to manage without her mother’s guiding hand. Ma had mentioned the name of their father’s rich relative but Lucy expected nothing from him for she knew that her mother had refused his help after Pa died, because of her pride. Mr Stoneham’s lawyer had offered financial help but Ma had refused it and nothing more had been heard from Mr Stoneham. Now Lucy had Ma to bury and did not know how she would manage it.

Unless she could find five pounds, they would bury Ma in a pauper’s grave. The vicar had been to visit and asked what hymns she wanted sung in church and he’d told her that it would cost six pounds for the burial if they wanted a good oak coffin. All they had in the world was the eighteen shillings in Ma’s purse and two shillings Josh had left in his pay packet that week. As a lowly apprentice at the factory, he received only three shillings and sixpence a week.

‘Where are we goin’ ter get five pounds?’ Josh asked anxiously. Kitty was whimpering, crying for her mother. Lucy had given her bread and jam and it was all over her face.

Lucy picked up a flannel, wet it and wiped her sister’s face. ‘Crying won’t bring Ma back,’ she reproved and received a resentful look from Kitty, who at eight years old, and the baby of the family, had been her mother’s favourite.

‘I want Ma!’

‘So do I, but she’s dead,’ Josh said. ‘Stop that row, Kitty. We have to talk about what we’re goin’ ter do next.’

Lucy’s eyes went to the corner cupboard. Ma had loved it and she loved it too, but it was one of the few things of value they owned. ‘I suppose we could sell the cupboard,’ she said half-heartedly. ‘And we could sell Ma’s weddin’ ring or her gold pin that Pa gave her …’

‘Not the weddin’ ring,’ Josh said. ‘The pin and the cupboard and her clothes – you could sell her shoes at that stall …’

‘Josh!’ Lucy was distressed. ‘Must we sell Ma’s things when she’s hardly cold?’

‘Do you want Ma buried in a pauper’s grave?’

‘No, I don’t,’ Lucy said and tears trickled down her cheeks. ‘I can’t bear it, Josh! Why did it have to happen?’

He shrugged and looked miserable. ‘There’s Dad’s writing box in the tallboy,’ he said thoughtfully. ‘It may be worth more than the cupboard.’

‘We can’t sell Dad’s box whatever happens,’ Lucy said. ‘Supposing he comes back and asks for it?’

‘He’s dead,’ Josh said, and he was angry. ‘The box is mine as head of this family now he’s gone – and if I decide we’ll sell it, we will.’

Lucy supposed he was right. Men usually inherited everything and he was nearly a man, even though nearly two years younger than Lucy.

‘Where do we sell whatever we need to sell?’

‘There’s Ruskin’s stall on the market for the clothes and I’ll ask around for the furniture,’ Josh said and ignored Lucy’s reproachful look. ‘Ma isn’t goin’ to want her clothes, Lucy. We should let the things we like least go first – because we’ll need to sell a bit at a time or they’ll cheat us.’

‘What do you mean? Why should we sell more than we need for the funeral?’

‘Because they won’t let us stay here,’ Josh said. ‘We haven’t always paid the rent on time since Pa went – and now there are just us three the landlord will want us to leave.’

‘Where shall we go?’ Lucy had not thought she would have to leave their home and for the moment she was stunned, leaving her brother to make the decisions.

‘I’ll find us somewhere,’ he said, assuming the mantle he’d taken for himself. ‘But we have to sell some bits of furniture, because we shall only be able to afford a room – so the tallboy and the parlour furniture go first and then we’ll see.’

Lucy looked at the set of his face and knew he was hating this as much as her, but it had to be done. They must sell the things Ma had been so proud of and keep only small bits and pieces they could easily take with them. Besides, it looked as if they would have to sell most of what they had to cover the cost of the coffin and burial in hallowed ground …

Lucy counted the coins in her purse. She had five half-crowns, six shillings and several sixpences and pennies. It was all they had left in the world after paying their debts and the rent owed for the cottage they were leaving that day.

Lucy hadn’t seen the room Josh had found for them yet, but she guessed, from the look in her brother’s eyes, that it was not what they’d been used to. He’d loaded most of what they still owned on a barrow he’d borrowed and taken it on ahead. They’d managed to keep their mattresses, their father’s box, Ma’s sewing box, the corner cupboard and a few blankets, some crockery and their own clothes and trinkets. Their clothes were in three leather bags, which had belonged to their parents, and that was all they had left in the world.

Lucy was loath to sell her mother’s few bits of jewellery and she wore Ma’s wedding ring around her neck on a ribbon which was sewn together so it could not come untied and be lost. The little gold pin with a cabochon ruby was pinned inside Lucy’s frock, but that was all they had left. A gold cross and chain and a silver brooch had been sold, as well as a gold stock pin that belonged to their father. It had been Josh’s by right but he’d preferred to keep their father’s writing box.

Josh had taken some of their money to pay the new landlord. Because they were young, Mr Snodgrass had asked for a month’s rent in advance and Josh had paid him.

‘You can’t blame him,’ Josh said when they’d discussed it. ‘Why should he trust us?’

Lucy wondered if they could trust the landlord, but she didn’t challenge Josh, because he’d searched for the room and was proud that he’d found them somewhere to go. He was two years her junior but considered himself the man of the family. Mr Pottersby next door had hinted that they should go to the workhouse.

‘Kitty is not yet nine and should be in care of the wardens,’ he’d said to her. ‘You and young Josh can work, but what’s she to do all day? You won’t be able to afford to send her to school. Be sensible, lass, and put her in the workhouse. They’ll take care of her until she’s old enough to work – and then you can fetch her home.’

‘I’ll never let my sister go to the spike,’ Lucy told him proudly. ‘My father would want us all to be together.’

‘You’re a good lass.’ Mr Pottersby shook his head sadly. ‘The wife would take the little one in but we can’t afford to keep her …’

‘You’ve been good to us, sir,’ Lucy admitted, because his wife had sometimes brought her mother hot food in the middle of the day, when Lucy was working and could not look after her. ‘But Kitty wants to be with us.’

‘Well, I’ll wish you luck, Lucy,’ her neighbour said. ‘And if you want to sell that cupboard of yourn, I’d give yer thirty shillings fer it.’

Lucy had already been offered three pounds and refused it, so she shook her head and smiled. ‘Thank you, but we shall keep it to store our bread and cheese in. I’ll remember your offer if I need it, Mr Pottersby.’

‘Well, orf you go then – and give me your key. The landlord says I’m to keep it until the new tenant comes this afternoon.’

Lucy turned back to look at her home, tears hovering. She’d been happy there as a small girl when Pa was home from the sea, and now she was leaving it all behind to go to a place she was certain she would not like half as well …

The room was in one of a row of terraced houses in a dirty, narrow lane that didn’t even have a name, and the whole house stank of urine and stale, boiled cabbage. The windows were grimy, the dull grey lace curtains in holes, and the flooring was nothing but bare boards.

Kitty started crying as soon as she got inside and Lucy felt like joining in. Even with the peg rugs they’d brought from home and their mattresses and bits and pieces, it looked awful.

‘Oh, Josh – there isn’t even a table or a chair,’ Lucy said. ‘I thought there would be something.’

‘The room I saw and paid for was better,’ Josh said and looked as if he too wanted to weep. ‘It had a carpet on part of the floor, a bed and a table with chairs, and a chest of drawers – but when we arrived today, the landlord said someone else paid him more for it and this was all he had left for us. He said take it or leave it.’

‘Did he give you some of your money back?’ Lucy asked and saw the answer in his eyes. Josh had been cheated and made to look a fool and now he was angry and hurt, but there was nothing he could do. Having seen the landlord on her way in, Lucy would never have trusted him with their precious money, but it would only humiliate Josh to say so. He’d thought he was making a home for them and now he felt shamed.

‘I’ll look for somewhere better,’ Josh promised and Lucy forced herself to smile at him.

‘We’ll both look,’ she said. ‘I know it isn’t easy, especially when we both have to work …’ She hesitated, then, ‘What are we goin’ to do with Kitty when we’re at work?’

‘She’ll have to stay here,’ Josh said, then made a groaning sound. ‘I know it isn’t fit – but it’d cost money to send her to school, because she’ll have to pay for her dinner – and her clothes aren’t good enough.’

Lucy frowned. ‘Is there a charity school in this area?’ If she could take her sister to a school and leave her for the day she would feel much easier. Kitty was sensible most of the time – she’d attended a local school and she’d helped look after their mother in the last days of her life. Yet she was only eight years old and they could hardly leave her in this dreadful place all day, especially if their cheating landlord was around.

‘I think there’s a church school,’ Josh said. ‘They might take her – it would cost a penny or two a week for her food but not much.’

‘It’s Sunday tomorrow. I’ll go and ask after the service.’ Lucy sighed. She’d been working as she talked and now the room looked a little better. ‘We’re goin’ to move as soon as we can, Josh. And I’m goin’ to ask that awful man for some of our money back before we move.’

‘I already did,’ Josh said. ‘We’ve been cheated, Lucy, and there’s nothing we can do – but I’ll know better next time.’

Lucy nodded. She’d let him handle the move, because he’d wanted to, but in future she would make sure she knew what he was doing. It was hard enough to earn the few shillings they were paid each week and they could not afford to waste it.

‘Can you get a fire goin’ in the grate?’ she asked her brother. ‘I want to heat some soup for our tea. We’ll need to buy bread, in future, and it isn’t easy to cook anything here except in a saucepan.’

‘There’s a pie shop on the corner,’ Josh said and bent to start building the fire with the paper, wood and coal they’d brought with them. ‘I could bring us something home at night when I come from work.’

‘Yes …’ Lucy realised they would have to change the way they lived. She’d managed to buy food cheaply on the market, but unless she had somewhere to cook properly they would have to buy hot food from a shop or one of the stalls on the street corners, and that was bound to cost more. ‘Yes, we can do that sometimes, but I can toast bread over the fire, Josh – and a little soup is much cheaper.’

Josh looked angry. ‘I didn’t do very well, did I? You’d better look after the money in future.’ He took some copper coins from his pocket and slammed them down on top of the corner cupboard. ‘I’ll be back later …’

‘Where are you goin’?’ Lucy asked but he was gone, shutting the door with a bang.

‘I want to go home!’ Kitty started whining and crying. ‘I’m cold and I’m hungry …’

‘I’ll make you some toast and soup as soon as I’ve got the fire burning properly,’ Lucy said and used the cheap brass Vesta case that had been her mother’s to strike a match and light the paper Josh had stuffed into the grate. It caught immediately and she layered wood on it, then a few pieces of the coal Josh had brought on the barrow.

In future Josh would have to bring a bag home on his way from work and he needed to make a small barrow for himself, because the larger one he’d borrowed had already gone back to its owner.

Lucy’s eyes stung with tears as she prepared their meal. Life had never been easy but it was going to be a lot worse now …

Lucy spoke to the Reverend Mr Joseph the next day, after morning service. She explained their predicament and he immediately told her that Kitty would be welcome in his school. There would be a payment of one penny a day for five days a week, which covered the cost of hot soup and bread for lunch and a cup of milk; it was very reasonable and just within her means. Lucy thanked him and he nodded, giving her a sorrowful look.

‘It is hard to lose one’s parents, especially for such a young girl as you, my dear,’ he said. ‘I expect your brother has taken charge of the family, as he should being the man of the family, but you will have the care of your little sister – and she will be quite safe in my charge.’

Clearly, he believed that her brother was older, the protector of his family. Lucy said nothing to make him change his mind, because she knew that if people thought they were not fit to have charge of their own lives they would be forced into the workhouse.

Lucy thanked him and turned away, holding Kitty by the hand. It was a cool morning, the sun overcast by dark clouds, and the drab streets seemed unusually empty, only an old man bending to pluck something from the filth in the gutter and a ginger cat licking itself on a windowsill. As she walked home, Lucy thought about the new dress she would make for her sister; she’d kept a couple of Ma’s best dresses, which had been made of good material, for when Pa was alive money had not been so tight, and she could cut them up for Kitty so that she looked decent for school. Pa had been the third son of a country parson, and made his way in the world as a sea captain until the storm had taken his life and cargo. As she turned, Lucy almost bumped into a young girl. She had beautiful pale-blonde hair and looked to be a similar age to her own.

‘Forgive me,’ Lucy apologised. ‘I wasn’t lookin’ where I was goin’.’

‘Nor was I,’ the other girl said and laughed. ‘My name is Eliza Jones – and I work for Miss Edith Richards as her assistant. She’s an apothecary and I’m taking the Reverend Mr Joseph a cure for his rheumatism – but you mustn’t tell him I told you.’

Lucy smiled, assuring her she would not. ‘I’m Lucy – I’ve just been arranging for my sister Kitty to start school with Mr Joseph tomorrow,’ Lucy said and pushed her sister forward. ‘Say hello to Eliza.’

Kitty hung her head and mumbled something, but Eliza smiled and bent down to look at her. ‘You are a lucky girl to be able to learn your letters, Kitty. I never learned until I went to live with Miss Edith and I should’ve liked to learn when I was your age.’

‘I want to go home,’ Kitty said and a tear trickled down her cheek. ‘I want Ma …’

‘Ma died,’ Lucy said and looked at the other girl apologetically. ‘Kitty is only eight and doesn’t understand what it means when someone dies.’

‘Your mother has gone to Heaven,’ Eliza said and smiled at the younger girl. ‘I hope you enjoy school, Kitty. I must go – it was nice to meet you, Lucy. Perhaps we’ll meet again.’

‘Yes, I’d like that.’ Lucy took her sister by the hand. She’d liked the look of Eliza Jones and wished she might have got to know her better, but Eliza was busy and Lucy had a lot to do when she got back to their room. Even though it was such a poor place, it had to be kept tidy and she wanted to speak to the landlord if she could. There must be a kitchen in the house and she ought to have the use of it sometimes – just as she’d learned they all shared the toilet in the back yard. Otherwise, how was she to wash their clothes? If she took them to a laundry the charge would be more than her slender purse could afford.

A surge of disgust went through her as she remembered taking their chamber pot to the closet in the yard that morning. It had stunk worse than anything she’d ever smelled before, making the vomit rush up her throat as she’d emptied their pot into the nauseous pool of sewage. How long was it since anyone had paid the night-soil man to come and clear the waste away? Lucy’s mind moved on to something even more troubling. It had been very late when her brother had come home the previous evening. She’d been waiting up for him, worried, because he’d never been home that late, and when he’d eventually come in at past one in the morning, it was obvious that he’d been drinking.

‘Oh, Josh,’ she’d said to him. ‘What have you done? I thought you had no money?’

‘I didn’t sh-pend any …’ he said and started giggling. ‘My f-friends treat … shed me …’ He hiccupped and grinned at her foolishly. ‘Don’t look at me like that … you’re not my …’ He’d turned away hurriedly and been sick on the floor. The smell had been awful and it had taken Lucy two trips to the tap in the back yard to fetch enough water to wash the stink away.

Josh had apologised before falling on to his mattress and immediately started to snore. Lucy wasn’t sure if he was really asleep, but she hadn’t remonstrated with him. What could she do? She wasn’t his mother and she didn’t have the right to order him around. His recent rise in wages meant he earned almost as much as she did, and he’d always brought every penny home.

Lucy stuck her chin out defiantly. She and Josh had decided that they could manage on their own. They certainly did not want to live in the country with their mother’s sister; Ma hadn’t liked her and so she must be awful. The only other alternative was the workhouse, and Lucy had heard bad things about the one in Farthing Lane. People crossed themselves as they hurried by and Mr Pottersby said he’d rather die than go there. Lucy was determined that neither she nor her brother or sister was ever going to set foot there and she pitied the poor devils who had no choice.

‘I really cannot see why you wish to inspect the kitchens,’ Mistress Docherty said when Arthur made the request that morning. ‘I assure you everything is done in accordance with workhouse rules.’

‘Oh, I am certain that you follow them to the letter, ma’am,’ Arthur replied with a smile that eased her frown. He was a handsome man and not many women could resist that smile; despite her resistance, she softened towards him. ‘I just wish to make sure that your employees are doing as you bid them – I am sure you would not wish your inmates to be cheated of their rights?’

‘Indeed not, sir,’ Mistress Docherty replied, pursing her thin lips. She was a thin woman with a straight back, pale face and dark hair that she wore scraped back in a knot. Her black button boots shone and her black dress was neat, a lace collar fastened at the throat with a cameo brooch. ‘I am looking for a trained cook, but it is not easy to find one who will work for the wages I can offer. One of the inmates does the cooking at the moment, and others help. Her meals are adequate but perhaps might be better.’

‘It is not easy to find cooks of the right quality,’ Arthur agreed.

The mistress of the workhouse insisted on accompanying him to the kitchens, which was slightly annoying as he preferred to talk to the inmates alone so they might talk freely.

A stew was being prepared in the kitchen. It was a long room with low ceilings and dark beams from which hooks were suspended so that pans and skillets could be hung close to the black range where the meal was slowly cooking. The newly whitewashed walls gave it an appearance of cleanliness and the tiled floor had been scrubbed recently. The smell of the stew was quite enticing, and Arthur asked if he might taste the broth. Given a spoon, he dipped it in the liquid and then sipped. It contained more meat than in the past and he nodded his satisfaction at Sadie, the old woman who presided over three others. He noticed that one of them was Moll; she sat by the pot and gave it an occasional stir. As he watched, she tasted it and then, when Sadie’s back was turned, she put in a pinch of salt and winked at Arthur. He smiled back, because he liked the elderly woman’s spirit.

‘Tasty,’ he said when Sadie looked at him for approval. She scowled at him, clearly not responding to his charm. ‘What else are you giving the inmates this evening, Cook? I fear I do not know your name …’

‘She is Sadie, almost our oldest inmate; Moll now claims that status …’ Mistress Docherty said.

‘I should be sittin’ in comfort by the fire,’ Sadie grumbled. ‘Not expected to do all the cookin’ at my age.’

Arthur saw the indignant look her helpers gave her and guessed that Sadie did little but oversee the preparations. ‘So just the stew, then.’ He frowned and looked at the mistress for confirmation but Sadie answered.

‘Bread, stew and a mug of beer is what they get,’ Sadie muttered rudely. ‘What do yer expect – a plate of best rare beef?’

‘I wondered if perhaps there was some cheese to accompany the bread.’

‘Not from the rations I’m given.’ Sadie looked at the mistress, clearly shifting any blame.

‘Cheese is sometimes given to the men after the midday meal,’ Mistress Docherty informed him. ‘I do not believe it aids the digestion at night and may give nightmares, so I do not allow it.’

‘Perhaps apple pie or a steamed pudding might be substituted?’ Arthur suggested, but Sadie’s scowl deepened.

‘Not without another cook,’ she muttered. ‘I’m too old to be bothered with makin’ pastry at night – ’cept for her and the master’s supper.’ Sadie looked at the mistress resentfully and sniffed. ‘All these new ways …’

‘I am sure you do your best,’ Arthur said. ‘Perhaps another woman with some skill in pastry making might be set to work here.’

His suggestion fell on unwilling ears. Mistress Docherty was at pains to explain that she had been unable to find a woman capable of cooking good plain food among the inmates who worked for their keep and a bed; it would cost money to bring in outside help and Mistress Docherty complained that her budget would not allow for it.

Arthur said that he would see what could be done. Overall, he was satisfied that Mistress Docherty at least made sure both the workhouse and its inmates were as clean as possible. There was no sign of the lice that most men, women and children carried when they entered for the first time, and he had no real complaints. It was much as he’d expected. Mistress Docherty was efficient and honest but she lacked the compassion of the woman he had wished to bring here. He was vaguely unhappy with his visit, because despite all his efforts he could see little improvement in the lives of the inmates. He’d hoped for a much better atmosphere amongst the inmates after the recent changes, however, his was but one voice on the Board of Guardians and he could not object to Mistress Docherty’s regime.

He was thoughtful as he left. He had done his duty and now intended to enjoy a short break in the country at a friend’s estate. The business of more money for the workhouse kitchen could be attended to after the long weekend.

Perhaps he was wrong, perhaps the mistress was kinder than he thought and concerned herself for her inmates’ welfare more than he suspected …

‘So what is your name?’ the mistress asked of Lil when she presented herself at the workhouse door next morning. Lil was heavily pregnant, barefoot, and needed somewhere to stay for the birth of her child. ‘My name is Mistress Docherty and I shall try to make your stay here as comfortable as possible – though you must understand that your situation marks you as a fallen woman and you will sleep in a dormitory with others of your kind. I cannot have you contaminating my respectable women and girls.’

‘I’m Lil, missus,’ she said, her cheeks pink, ‘and this is me second. The first died when I was ’ere last time – or so the missus told me then.’

‘Well, we must hope for a happier outcome this time, Lil,’ Mistress Docherty said but did not smile. Lil was unsure whether to trust her. ‘As you know, we expect our inmates to work while they are here. However, in your condition we shall not ask too much of you until after the birth – perhaps you could help out in the kitchen? We are in need of a light hand with the pastry, I know. The work there is not hard and I’m sure the other women will look after you.’ Her words were fair enough but there was no warmth or kindness in them and Lil shivered. She’d come to this place because she was close to starving; there were few men who would pay for her services while she was pregnant and without the workhouse, she and her baby would probably die.

The mistress handed Lil a parcel of clothes, which although they were the workhouse uniform worn by all the pregnant women inmates, were better than the rags she was wearing, and a pair of much-worn shoes. Lil knew the clothes marked her out as being a fallen woman and it shamed her to wear them, but she had no choice. When she’d heard that Mistress Simpkins had been sent to prison, Lil had thought things might be better here, but this woman obviously intended to stick to the harsh rules by which all such institutions were run.

‘Do I go to the bath house first, missus?’

‘I’ll take you there myself – and then you can find your own way to the kitchens, I think.’

‘Yes, missus. I’ve been in ’ere afore …’

‘I am aware of that,’ Mistress Docherty snapped as she led the way to the bath house, where she unlocked the cupboard outside and gave Lil a bar of soap, a flannel and towel. ‘Those are your own to keep while you’re here – you should sew in a label with your mark so they do not get lost. If you come to my office later today, I’ll give you some labels.’

‘Thass new.’ Lil looked at her speculatively. ‘Do I give ’em back when I leave ’ere?’

‘You may be able to keep them; it depends on your good behaviour in the meantime. The guardians are trying to make life better for our inmates, but you must not take advantage. Stealing is still punishable and you would lose privileges for breaking our rules – but if you keep faith with us, we shall do our best for you. God forgives those who truly repent.’

‘Yer ain’t bad, missus,’ Lil said and grinned, showing gaps in her teeth. ‘No one ain’t ever looked out fer me. Me old man was at me afore I was ten – and me ma died when I were eleven, not that she ever done much but ’it me. I’ve ’ad to get on by meself – and it ain’t bin easy.’

‘I don’t expect it was, Lil,’ Mistress Docherty said looking down her long nose. No respectable woman wanted a whore in her home, and without a reference it was impossible to find a job as a servant in a decent house. ‘I am here if you want to talk – and when you’re ready to leave I’ll help you find a proper job, if you wish.’

‘Who would employ me?’ Lil asked. ‘I ain’t never done nuthin’ but skivvy or lie on me back – and I know which is easiest!’

Mistress Docherty pursed her lips in disapproval. ‘I could help you find respectable work, but it is hard work and would be entirely your choice. I am not here to judge you, only to help.’

Lil entered the bath house. The baths were made of zinc, several of them in a row and divided by a curtain, and they had to be filled from the large vat of hot water with a bucket. She discovered that drains had been installed since her last visit, which made it easier to empty the used water and clean the bath after use. Lil wondered what else had changed here, but had little expectation that things would have improved very much.

The strict rules meant that all inmates must wear the clothing issued, and they must do the work allocated to them, which could be hard. Everyone had to work, but they were all entitled to a hot meal in the evenings and a good breakfast of porridge or bread, with a break for a slice of bread and cheese midday, more than Lil had been used to of late. Water, a mild beer, and occasionally milk for the children, was served with the evening meal. Lil had heard from others that the inmates did not go hungry these days and so they did their work willingly and the workhouse earned money from some piecework that was sent in.

Lil had been told that the women were all granted the privilege of attending church every Sunday if they wished, and the children were given school lessons twice a week, learning to read and to write their names rather than making a mark, which was certainly not the case in every workhouse. Most guardians thought that girls needed only to learn how to do housework, sew, cook and, perhaps, weave if their fingers were nimble. Lil knew that since Mistress Simpkins had been sent away, the girls and some of the women, too, were being taught needlework and how to keep house and cook; the boys were learning carpentry, boot making and tailoring as well as how to repair buildings. All of these innovations had begun since the new regime. Lil had heard that most of the reforms had been decided between the new master and someone called Mr Arthur Stoneham. Mr Stoneham had suggested that the boys learn new trades when he’d discovered one of the older men living in the workhouse was a cobbler and another a tailor.

‘It seems only sensible to make use of inmates who have these skills, does it not?’ he’d asked the master of the workhouse and he’d grudgingly agreed, because Arthur Stoneham was the chairman of the Board and these days not many disagreed with him openly, though each reform had been hard fought for.

Dressed in her hated uniform, Lil made her way across the courtyard to the kitchens, clutching her belongings. She’d been allocated a room with one other unmarried pregnant woman, who also wore the badge of shame, and would take her damp towel there when she was ready, but she was hungry and she was hoping that Ruth and Cook would give her something to eat. However, when she reached the kitchen she discovered that the women who had been kind to her on previous visits to the workhouse were no longer there.

‘Went orf months ago, they did,’ Sadie muttered giving Lil a look filled with spite. ‘I’m in charge ’ere now and no one gets no favours, see. Put yer things under the table, get an apron on and start peeling them spuds and carrots. I’ve got three ’elpers and one of ’em is sick in the infirmary – so you’ll have to look sharp about it.’

Lil wasn’t feeling well and she would have liked a glass of ale and a bit of bread and cheese, as well as a chance to put her feet up, but she knew she’d surrendered her freedom by coming here. Those who said the spike was much better than being on the streets had it wrong, in Lil’s opinion; some of the bad things might have been stopped, but life was as harsh in here as it had always been.

‘I hope you do not mind my calling on you,’ Katharine Ross said as she was admitted into the neat parlour at the refuge for fallen women. ‘When Mr Stoneham told me you had taken over, I wanted to make myself known to you. Mr Stoneham may have told you that I have charitable interests in common with him?’

‘Yes, he has, Miss Ross,’ Hetty said and smiled at the fashionable young woman wearing a rather frivolous hat. ‘Please sit down. You are very welcome here.’

‘Please, call me Katharine.’ Katharine Ross looked pleased. ‘I do want us to be friends, Hetty – may I call you that?’ Hetty agreed and her visitor nodded. ‘You will be doing such good work here.’

‘I am glad to be of help where I can – though it was not the job Mr Stoneham intended, I think?’

‘No …’ Katharine frowned. ‘He very much wanted you to take over the workhouse in Farthing Lane, but another was chosen despite his arguments.’ She shook her head. ‘The way that awful Simpkins woman treated some of these children!’

‘He was so angry …’

‘Oh yes, I know how concerned Arthur was for those children,’ Katharine agreed. ‘Had it not been for his intervention, some of them would have been lost forever.’

‘Yes, indeed,’ Hetty agreed. ‘Thankfully, he was in time to stop them.’

Katharine nodded. ‘Mr Stoneham is a truly good and charitable man – do you not agree, Hetty?’

‘Yes, he is,’ Hetty agreed, ‘though he would not like to hear us say so for he does not think it.’

‘He may not think it – but we know, do we not?’

They smiled at each other in perfect agreement, and then Katharine said, ‘I have come to arrange when it will be convenient to commence the sewing lessons?’

‘I think two afternoons a week would suit us, if that is agreeable?’

Katharine said that it was and soon after took her leave.

Hetty was thoughtful after her guest had gone. Her love for Arthur was unselfish and she liked the young woman he had given his heart to. She hoped that they would find happiness together for both had suffered loss and unhappiness in the past.

Arthur flicked through the pile of post in his study. It had accumulated while he was out of town and most of it was unimportant. He could not be bothered to go through the pile himself and thought that he ought to have a private secretary to do such things for him. His butler normally placed those he thought important on top and Arthur answered his letters when he considered it necessary.

He shrugged, turning away with a frown on his face. In no mood for social events, he ignored what were most likely invitations to a ball or other frivolous affairs. His lawyer attended to anything of importance and Benson would have ensured a missive from him wasn’t missed. He would seek out his friend Toby and then visit Hetty at the refuge and see if she was settled in …

CHAPTER 4 (#uf6d309d4-64fc-56fb-a737-0b90c85f94d8)

‘What are yer doin’ in ’ere?’ the fat woman demanded as Lucy put her pot of chicken and vegetables into the black range oven, which had a dull, used look and needed a good brush and polish. ‘You ain’t entitled to use the oven – there’s too many of us need to use it already.’

‘Mr Snodgrass says I can, as long as I provide my own fuel, and I’ve brought a bucket of coke with me,’ Lucy said and lifted her head defiantly. The woman smelled of sweat and unwashed clothes. ‘He says we all have the use of everythin’ – the kitchen and the tap in the yard and the toilet. He’s goin’ ter have the night soil cleared and we all have to pay another two shillings next month on the rent.’

‘And who asked you to interfere?’ the woman said. ‘I’m Jessie Foster and I’ve bin ’ere longer than anyone – and your room should’ve been mine when the last lot left. So why don’t you get yer stuff and go while yer can? I’ll make yer sorry if yer poke yer nose in my business!’

‘I’ve put my pot in the oven, and if there’s no room for yours you will have to wait until someone takes theirs out,’ Lucy said.

‘You little …!’ The woman raised her fist in threat.

‘Leave ’er alone, Jessie,’ the other woman who was in the kitchen said. ‘She’s got to cook sometimes, ain’t she? And I’m takin’ mine out now so you’ll have room fer yourn.’ She winked at Lucy. ‘About time someone made ole Snodgrass call out the night-soil man – that yard stinks to ’igh ’eaven.’

Jessie stormed off.

‘It’s too expensive to buy hot food from the pie shop every night,’ Lucy said apologetically. ‘I have to cook somewhere.’