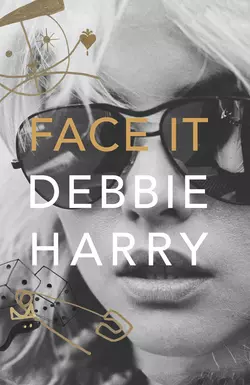

Face It: A Memoir

Debbie Harry

‘I was saying things in songs that female singers didn’t really say back then. I wasn’t submissive or begging him to come back, I was kicking his ass, kicking him out, kicking my own ass too. My Blondie character was an inflatable doll but with a dark, provocative, aggressive side. I was playing it up, yet I was very serious. ’ BRAVE, BEAUTIFUL AND BORN TO BE PUNK DEBBIE HARRY is a musician, actor, activist and the iconic face of New York City cool. As the front-woman of Blondie, she and the band forged a new sound that brought together the worlds of rock, punk, disco, reggae and hip-hop to create some of the most beloved pop songs of all time. As a muse, she collaborated with some of the boldest artists of the past four decades. The scope of Debbie Harry’s impact on our culture has been matched only by her reticence to reveal her rich inner life – until now. In an arresting mix of visceral, soulful storytelling and stunning visuals that includes never-before-seen photographs, bespoke illustrations and fan art installations, Face It upends the standard music memoir while delivering a truly prismatic portrait. With all the grit, grime, and glory recounted in intimate detail, Face It recreates the downtown scene of 1970s New York City, where Blondie played alongside the Ramones, Television, Talking Heads, Iggy Pop and David Bowie. Following her path from glorious commercial success to heroin addiction, the near-death of partner Chris Stein, a heart-wrenching bankruptcy, and Blondie’s break-up as a band to her multifaceted acting career in more than thirty films, a stunning solo career and the triumphant return of her band, and her tireless advocacy for the environment and LGBTQ rights, Face It is a cinematic story of a woman who made her own path, and set the standard for a generation of artists who followed in her footsteps – a memoir as dynamic as its subject.

(#ulink_e9cc98ac-0679-5df4-ad85-9fcbc8c4e74e)

(#ulink_fb7414a6-282b-5ece-9cc7-5352b8c2b8f9)

Brian Aris

Jody Morlock

Copyright (#ulink_924801f4-34ab-5cf0-bb03-502e033c4d62)

HarperCollinsPublishers 1 London Bridge Street London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

First published by HarperCollinsPublishers 2019

FIRST EDITION

© Debbie Harry 2019

Cover layout design by Rob Roth

Cover photograph © Chris Stein; illustration by Jody Morlock

Creative Direction by Rob Roth

A catalogue record of this book is available from the British Library

Debbie Harry asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

HarperCollinsPublishers has made every effort to credit the copyright owners of all material used in this book. If your work has not been credited, please contact us so that we may correctly credit your work in future editions

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the nonexclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins e-books.

Find out about HarperCollins and the environment at www.harpercollins.co.uk/green (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk/green)

Source ISBN: 9780008229429

Ebook Edition © October 2019 ISBN: 9780008229450

Version: 2019-09-27

Dedication (#ulink_58d37cfb-cad6-5d87-ae56-1a3de0ec075c)

DEDICATED TO

THE GIRLS OF THE

UNDERWORLD

Bob Gruen

Courtesy of Debbie Harry’s personal collection

Contents

Cover (#ulink_eb3fb588-5cdb-5dc3-a437-48c5b358946c)

Title Page

Copyright (#ulink_edefab00-70e1-5017-954c-a726d2ef6f3d)

Dedication (#ulink_fdf0269c-8cd8-57f3-8813-a165c8df7d45)

Introduction (#ulink_24f13363-8081-5955-94d1-0cbba0135fa4)

1. Love Child (#ulink_972eadc0-9494-5dcd-aa49-a5abe547319d)

2. Pretty Baby, You Look So Heavenly (#ulink_bfedc918-8e17-5de0-9740-b87bbcdca0cc)

3. Click Click (#ulink_6cf372de-c83d-5dfd-9ab7-c99229a689fc)

House Lights (#ulink_02305353-a492-5550-b70b-4e89b72509fd)

4. Singing to a Silhouette (#ulink_3620367d-ef3a-500a-99b5-475531762db6)

5. Born to Be Punk (#litres_trial_promo)

6. Close Calls (#litres_trial_promo)

Curtain Up (#litres_trial_promo)

7. Liftoff, Payoff (#litres_trial_promo)

8. Mother Cabrini and the Electric Firestorm (#litres_trial_promo)

9. Back Track (#litres_trial_promo)

10. Blame It on Vogue (#litres_trial_promo)

Peekaboo (#litres_trial_promo)

11. Wrestling and Parts Unknown (#litres_trial_promo)

12. The Perfect Taste (#litres_trial_promo)

13. Routines (#litres_trial_promo)

Evidence of Love (#litres_trial_promo)

14. Obsession/Compulsion (#litres_trial_promo)

15. Opposable Thumbs (#litres_trial_promo)

Photo and Art Credits (#litres_trial_promo)

Acknowledgments (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

Introduction (#ulink_d6a2a19a-d6bb-5a34-92a4-df20c65f3cea)

BY CHRIS STEIN

Courtesy of Debbie Harry’s personal collection

I don’t know if I ever related this story to Debbie . . . or anyone for that matter. In 1969 after traveling around, driving twice cross-country, I was staying with my mom at her apartment in Brooklyn. This was a tumultuous year for me. Psychedelics—and my delayed reaction to my father’s death—caused breaks and disassociations in my already fractured psyche.

In the midst of heightened states, I had a dream that stayed with me. The apartment was on Ocean Avenue, a very long urban boulevard. In the dream, in a scene that referenced The Graduate, I was chasing the Ocean Avenue bus as it pulled away from our big old building. I was pursuing the bus—yet inside it simultaneously. Standing in the bus was a blond girl who said, “I’ll see you in the city.” The bus pulled away and I was left alone on the street . . .

By 1977, Debbie and I were traveling extensively with Blondie. Far and away our most exotic stop was Bangkok, Thailand. The city then wasn’t covered with cement and metal but was fairly bucolic, with parks all around and even dirt roads near our upscale hotel. Everything smelled of jasmine and decay.

Debbie developed a touch of “la tourista” and stayed behind one night in the hotel while the guys from the band and I went to the house of some British expatriate whom we’d met in some bar or other. His old Thai maid prepared a banana cake for us into which she had chopped fifty Thai sticks—the seventies equivalent of modern super-strong “kush” or other intense strains of weed. We’d also just come from a long stretch in Australia, where pot was strictly policed and forbidden at the time. We all got well stoned and somehow led each other back to the hotel.

Our room was also very exotic, with decorative rattan elements and two separate cotlike beds equipped with hard cylindrical pillows. Debbie had fallen into a fitful half sleep and eventually I drifted into a foggy blackness. Somewhere toward morning, my unconscious dream self became clearer and began an internal dialogue. “Where are we?” asked this internal voice—whereupon Debbie, still in a half sleep on her cot, said aloud, “We’re in bed, right?” I sat up, suddenly wide awake.

Did I actually speak and produce a response from her even though we both were in semi-asleep states? To this day, all these years later, I am convinced that I only thought the question.

And another story that’s even more subtle and weird and difficult to convey . . . Getting high was just a part of the music and band culture that we came up in. It didn’t seem like anything extraordinary. Everyone at all the clubs drank or got stoned with almost no exception. I wasted a tremendous amount of time and energy dealing with substance abuse and self-medication. It’s impossible to say if what I’d like to see as psychic events were merely induced delusions. Perhaps it’s like any religious faith—you believe what you want to believe. Certainly, consciousness extends beyond oneself, one’s body.

Anyway, Debbie and I were once again in some state of advanced intoxication at a very elaborate party downtown. Small events and views were sharply defined. I remember a spiral staircase and fancy chandeliers. Some fellow showed us his Salvador Dalí Cartier watch—and that fleeting glimpse has stayed with me forever. It was an amazing object, a standard tear-shaped Cartier design but with a bend that mimicked the melting watches in The Persistence of Memory. The crystal face was broken and the owner complained of having to spend thousands of dollars to replace it. To me, though, the cracked glass was a perfect Dadaist commentary on the original. I loved that.

The event—whatever it was—was very crowded. I remember being on a balcony when we were approached by an older man in a very fancy suit. He had a slight accent, maybe Creole. He introduced himself as Tiger. And that’s it for my specific memories, except for the extravagant sense of connection that Debbie and I felt with this guy. It was as if we had known him forever—a person we’d known in past lives. Do I believe in that stuff? Maybe. I don’t recall how much Debbie and I discussed this meeting afterward, but it was enough to compare notes and similar reactions.

Pretty early on—maybe 1975—Debbie found this person, Ethel Myers, who was a clairvoyant, a psychic. She’d likely come as a recommendation, but we might have simply found her through an ad in the Village Voice or Soho News. She worked out of an amazing ground-floor apartment that was on a side street uptown, right around the Beacon Theatre. Ethel’s environment was beautiful. It probably looked the same as it had when her building was built near the turn of the century. Her sitting area was an atrium that was like a greenhouse taken up with furniture. Decorative plants and herbs hung all around. Yellowing books about ectoplasm and tarot lay on dusty end tables. The whole place was well worn and reminded me of the apartment in Rosemary’s Baby when Mia Farrow and Cassavetes are first shown it.

We sat down with Ethel and she encouraged us to use a cassette machine we’d brought to record the session. She didn’t have any idea of who we were but proceeded to do a great cold reading. She told Debbie that she saw her on a stage and that Debbie would be fulfilled and travel a great deal. At one point she said that a man, presumably my father, was watching and that this man sarcastically said of me, “I wouldn’t touch him with a ten-foot pole.” I derive a lot of my sense of humor from my father—and the “ten-foot pole” bit was something he actually said all the time. Was she just in touch with the vernacular of the fifties that the old man used or was it more?

Debbie still has the cassette in her archives but I remember us listening to it years after and Ethel’s voice being very faint, as if it had somehow faded in the way of a ghost deteriorating over time.

Just now I called Debbie to ask what, if any, of this she remembered. She said, “You know, Chris, it was different back then, there was a lot more acid in the air.”

We still have a connection.

CHRIS STEIN

New York City, June 2018

Courtesy of Debbie Harry’s personal collection

1 (#ulink_8765aa1f-6222-5af1-a789-a831021cacb7)

Love Child (#ulink_8765aa1f-6222-5af1-a789-a831021cacb7)

Childhood and family photos, courtesy of the Harry family

Sean Pryor

They must have met around 1930, in high school, I figure. Childhood sweethearts. She was a middle-class girl, Scots-Irish, and he was a farm boy, French, living somewhere around Neptune and Lakewood, New Jersey. Her family was musical. She and her sisters would play together, all day long. The sisters sang while she played on a battered old piano. His family was artistic too and musical as well. However, his mom was in a psych ward, for depression—or some kind of recurring nervous condition. Unseen, but a powerful presence. It sounds contrived to me but it is what I have been told by the adoption agency.

Her mom ruled that he was the wrong kind for her daughter. She nixed the relationship and their love was axed. To further kill any contact, they banished her to music school and from there, she supposedly began touring concert halls in Europe and North America.

Many years go by. He’s married now, with lots of children. He works at a fuel company, repairing oil burners. One day, he heads out on a service call and boom, there she is. She’s leaning against the door frame, hair down, and she’s looking at him with that look. It’s her heater that’s broken . . . Well, that’s quite a picture, isn’t it, but I feel certain they were happy to see each other.

All those years, maybe they never stopped loving each other. Well, it must have been a wonderful reunion. She gets pregnant. He finally tells her that he’s married with kids. She’s pissed and heartbroken and she ends it, but she wants to keep the baby. She bears it all the way and at Miami-Dade hospital on Sunday, July 1, 1945, little Angela Trimble forced her way into the world.

She and the baby made their way back to New Jersey, where her mother was dying of breast cancer. She nursed them both. But her mom persuaded her to put Angela up for adoption. And so, she did. She gave her Angela away. Six months later, her mother was dead and her baby daughter was living with a childless couple also from New Jersey. Richard and Cathy Harry, from Paterson, had met socially after high school. Angela’s new parents, also known as Caggie and Dick, gave her a new name: Deborah.

And that’s it. I am a love child.

They claim it’s unusual to have memories of your earliest moments, but I have tons. My first memory is at the three-month mark. Same day that my mother and father got me from the adoption agency. They decided on a little jaunt to celebrate at a small resort with a petting zoo. I remember being carried around and I have a very strong visual memory of gigantic creatures looming at me out of the pasture. I told my mother the recollection once and she was shocked. “My God, that was the day we got you, you can’t remember that.” It was just ducks and geese and a goat, she said, maybe a pony. But at three months, I didn’t have much to filter with. Well, I’d already lived with two different mothers, in two different houses, under two different names. Thinking about it now, I was probably in an extreme state of panic. The world was not a safe place and I should keep my eyes wide open.

For the first five years of my life we lived in a little house on Cedar Avenue in Hawthorne, New Jersey, by Goffle Brook Park. The park ran the whole length of the little town. When they’d cleared the land to build the park they built these temporary migrant worker houses—think two little railroad flats with no heating except for a potbelly stove. We had the migrant workers’ boss’s house, which by then had its own heating system and sat on the edge of the park’s big wooded area.

These days, kids are organized into activities. But I would be told, “Go out and play,” and I would go. I really didn’t have many playmates there, so some days I would play with my mind. I was a dreamy kind of kid. But I was also a tomboy. Dad hung a swing and a trapeze on the big maple tree in the yard and I’d play on them, pretending to be in the circus. Or I’d play with a few sticks, dig a hole, poke at an anthill, make something, or roller-skate.

Oak place.

Childhood and family photos, courtesy of the Harry family

What I really liked most was to fool around in the woods. To me it was magical, a real-life enchanted forest. My parents were always warning, “Don’t go in the woods, you don’t know who’s in there or what might happen,” like they do in fairy tales. And fairy tales—all the great, terrifying stories by the Brothers Grimm—were a big part of my growing up.

I have to admit, there were some scary folk skulking around in those bushes, probably migrants. They were genuine hobos who rode through on the train and would hunker down in the woods. They’d maybe get some work from the parks department cutting grass or something, then jump back on the train and keep on going. There were foxes and raccoons, sometimes snakes, and a little stream with tributaries and frogs and toads.

Along the brooks where nobody went, the abandoned shacks had crumbled to their foundations. I used to clomp around there, in the swampy, old, overgrown, moldy piles of brick that stuck up out of the ground. I would sit there forever and daydream. I’d get that real creepy kid feeling that you get. Squatting on my haunches in the underbrush, I would have fantasies about running away with a wild Indian and eating sumac berries. My dad would wag his finger at me and say, “Stay out of the sumac, it’s poison,” and I would chew that incredibly bitter-sour sumac right up, thinking, dramatically, I’m going to die! I was so lucky to have all that kind of creepy kid stuff—a huge fantasy life that has led me to be a creative thinker—along with TV and sex offenders.

I had a dog named Pal. Some kind of terrier, brownish red, completely scruffy, with wiry hair, floppy ears, whiskers and a beard, and the most disgusting body. He was my dad’s dog really, but he was very independent. And wild—a real male dog that hadn’t been fixed. Pal was a stud. He would wander off and slink back after being gone for a week, completely exhausted from all these flings he’d had.

There were also hundreds of rats infesting the woods. As the town became less rural and more populated, the rats started swarming into the yards and gnawing through the garbage. So, the local powers put poison in areas of the park. Such a suburban-mentality thing—and let’s face it, they were poisoning everything back then. Well, Pal ate the poison. He was so sick that my dad had to put him down. That was just awful.

But really, it was the sweetest place to grow up: real American small-town living. It was back before they had strip malls, thank God. All it had was a little main street and a cinema where it cost a quarter to go to the Saturday matinee. All the kids would go. I loved the movies. There was still a lot of farmland then—rolling hills for grazing, small farms that grew produce, everything fresh and cheap. But finally the small farms faded away. And in their place housing developments sprang up.

The town was in transition, but I was too young to know what “transition” meant or have an overview or even care. We were part of the bedroom community, because my father didn’t work in the town; he commuted to New York. Which wasn’t that far away, but God, at the time it seemed so far away. It was magical. It was another kind of enchanted forest, teeming with people and noise and tall buildings instead of trees. Very different.

My dad went there to work, but I went there for fun. Once a year, my maternal grandmother would take me to the city to buy me a winter coat at Best & Co., a famous, conservative, old-style department store. Afterward we’d go to Schrafft’s on Fifty-Third Street and Fifth Avenue. This old-fashioned restaurant was almost like a British tearoom, where well-dressed old ladies sat primly sipping from china cups. Very proper—and a refuge from the city bustle.

At Christmastime my family would go to see the tree in Rockefeller Center. We’d watch the skaters at the skating rink and look at the department store windows. We weren’t sophisticated city-goers, coming to see a show on Broadway; we were suburbanites. If we did go to a show it would be at Radio City Music Hall, although we did go to the ballet a couple of times. That’s probably what fostered my dream of being a ballerina—which didn’t last. But what did last was how excited and intrigued I was about performance and the whole thing of being onstage. Though I loved the movies, my reaction to those live shows was physical—very sensual. I had the same reaction to New York City and its smells and sights and sounds.

One of my favorite things as a kid was heading down to Paterson, where both my grandmothers lived. My father liked to take the back roads, winding through all the little streets in the slum areas. And much of Paterson was very old and neglected at that time, pre-gentrification, full of migrant workers who’d come to find jobs in the factories and the silk-weaving mills. Paterson had earned the title “Silk City.” The Great Falls of the Passaic River drove the turbines that drove the looms. Those falls had stared me in the face throughout my childhood, thanks to the Paterson Morning Call. On its masthead at the top of its front page sat a pen-and-ink drawing of the billowing waters.

Dad would always drive real slow down River Street, because it teemed with people and activity. There were gypsies who lived in the storefronts; there were black people who’d come up from the South. They dressed in brilliant clothing and wrapped their hair in do-rags. For a little girl from a white-on-white, middle-to-lower-middle-class burb, this was an eyeful. Wonderful. I would be hanging out the window, crazed with curiosity, and my mother would be snapping, “Get back in the car! You’re going to get your head chopped off!” She’d have rather not driven down River Street, but my dad was one of those people who like to have their secret way. Yay for Dad!

I find it mysterious now, how little was ever revealed, within our family, about my father’s side. Nobody talked about them, what they did, or how they came to be in Paterson. I remember, when I was much older, quizzing my dad about what his grandfather did for a living. He said he was a shoemaker or maybe a shoe repairman from Morristown, New Jersey. I guess he was too low-class for anyone in the family, my father included, to want to be associated with him. Which was kind of tragic, I thought. But my father would remark on how very fortunate his father had been to keep his job all through the Great Depression, selling shoes on Broadway in Paterson. They’d had money coming in when so many, many people were unemployed.

My mother’s family’s Silk City was far more elitist. Her father had had his own seat on the stock exchange before the crash and owned a bank in Ridgewood, New Jersey. So they must have been quite wealthy at some point. When my mother was a child, they would sail to Europe and visit all the capitals on a grand tour, as they used to call it. And she and her siblings all had college educations.

Granny was a Victorian lady, elegant, with aspirations of being a grande dame. My mother was her youngest child. She’d had her rather late in life, which was a cause for arched eyebrows and whispered innuendo within her politely scandalized circle. So when I knew her, she was already quite old. She had long white hair that reached to her waist. Every day Tilly, her Dutch maid, laced her into a pink, full-length corset. I loved Tilly. She had worked for Granny from the time she emigrated to America—first as my mother’s nanny and then as Granny’s cleaner, cook, and gardener. She lived in the house on Carol Street in a beautiful little attic room whose windows opened to the sky. Across the hall, in the storage part of the attic, there were dusty trunks full of curious stuff. I spent many a wonderful hour poking and rummaging through the frayed gowns and yellowed paper and torn photos and dusty books and strange spoons and faded lace and dried flowers and empty perfume bottles and old dolls with china heads. Then finally, breaking into my reverie, a worried call from below. I would close the door softly and slip away. Until next time.

My dad’s first real job after graduating high school was with Wright Aeronautical, the airplane manufacturer, during World War II. His next was with Alkan Silk Woven Labels, who had a mill in Paterson. When I was a little girl and he had to visit the plant, he would take me along with him. I took the tour of the mill many times, but I never once heard what the tour guide said because the looms were so fierce and loud.

The looms really did loom. They were the size of our house, holding thousands and thousands of colored threads in suspension while the shuttles at the bottom zoomed back and forth. At the confluence of all the threads, ribbons would appear and curl out, yard upon yard of silk clothing labels. My father would take these to New York and, like his father before him, play his own small part on the furthest peripheries of the fashion world.

As for me, I loved fashion for as long as I can remember. We didn’t have much money when I was growing up and a lot of my clothes were hand-me-downs. On rainy days when I couldn’t go out I would open up my mother’s wooden blanket chest. The chest was stuffed with clothes she’d picked up from friends or that had been discarded. I would dress up and trot around in shoes and gowns and whatever else I could lay my grubby little hands on.

Television, oh, television. Glowing, ghostly seven-inch screen, round as a fishbowl. Set in a massive box of a thing that would’ve dwarfed a doghouse. Maddening electronic hum. Reception through this bent antenna. Some days good, some days rotten—when the signal flickered and skipped and scratched and rolled.

There wasn’t a whole lot to watch, but I watched it. On Saturday mornings at five A.M. I would be sitting on the floor, eyes glued to the test pattern, black and white and gray, mesmerized, waiting for the cartoons to start. Then came wrestling and I watched that too, thumping the floor and groaning, my anxiety levels soaring at this biblical battle of good vs. evil. My mom would holler and threaten to throw the goddamned thing out if I was going to get that worked up. But wasn’t that the point of it, getting all goddamned worked up?

I was an early and true devotee of the magic box. I even loved watching the picture reduce to a small white dot, then vanish, when you turned the set off.

When baseball season started, Mom would lock me out of the house. My mother, oddly, was a rabid baseball fan, and I mean rabid. She adored the Brooklyn Dodgers. They used to go to Ebbets Field in Brooklyn and watch the games when I was small. So I was always frustrated that I’d be locked outside for a baseball game. But I was a pest, I suppose—with a big mouth to boot.

My mother also liked opera, which she listened to on the radio when it wasn’t baseball season. As far as listening to music, we didn’t have much of a record collection though—a couple of comedy albums and Bing Crosby singing Christmas carols. My favorite was the compilation album I Like Jazz!, with Billie Holiday and Fats Waller and all these different bands. When Judy Garland launched into “Swanee,” I would burst into sobs every time . . .

I had a little radio too, a cute brown Bakelite Emerson that you had to plug in, with a light on the top and a funny old dial with art deco numbers like a sunburst behind it. I would glue my ear to the tiny speaker, listening to crooners and the big band singers and whatever music was popular at the time. Blues and jazz and rock were yet to come . . .

On summer evenings, a drum-and-bugle corps would practice in the parade ground just beyond the woods. These men, the Caballeros, would gather after work. They were just starting out and couldn’t afford uniforms, so they wore big navy-surplus bell-bottoms, white shirts, and Spanish bolero hats. They only knew how to play one song, which was “Valencia.” They would march back and forth all evening and sometimes they would dance, and you could hear the music drifting up from out of the woods. My room was up in the eaves of the house with little dormer windows, and I would sit on the floor with the windows open and listen. My mother would say, “If I hear that song one more time, I’m gonna scream!” But it was brass and snare and loud and I loved it.

There were so few distractions then, before I started school, and I had so much time for daydreaming. I remember having psychic experiences as a little girl too. I heard a voice from the fireplace talking to me, telling me some kind of mathematical information, I think, but I have no idea what it meant. I would have all sorts of fantasies. I fantasized about being captured and tied up and then rescued by—no, I didn’t want to be saved by the hero, I wanted to be tied up and I wanted the bad guy to fall madly in love with me.

And I would fantasize about being a star. One sun-drenched afternoon in the kitchen, I sat with my aunt Helen as she sipped at her coffee. I could feel the warm light playing on my hair. She paused with the cup at her lips and gave me an appraising stare. “Hon, you look like a movie star!” I was thrilled. Movie star. Oh, yes!

When I was four years old, my mom and dad came to my room and told me a bedtime story. It was about a family who chose their child, just like, they said, they had chosen me.

Sometimes I’ll catch my face in a mirror and think, that’s the exact same expression my mother or father used to have. Even though we looked nothing like each other and came from different gene pools. I guess it’s imprinted somehow, through intimacy, through shared experience over time—which I never had with my birth parents. I’ve no idea what my birth parents look like. I tried, many years later, when I was an adult, to track them down. I found out a few things, but we never met.

The story my parents told me about how I was adopted made it sound like I was someone special. Still, I think that being separated from my birth mother after three months and put into another home environment put a real inexplicable core of fear in me.

Fortunately, I wasn’t tossed into God knows what—I’ve had a very, very lucky life. But it was a chemical response, I think, that I can rationalize now and deal with: everybody was trying to do the best they could for me. But I don’t think I was ever truly comfortable. I felt different; I was always trying to fit in.

And there was a time, there was a time when I was always, always afraid.

2 (#ulink_3c2dac46-c13e-59e2-a4a5-a27ea71fd9c8)

Pretty Baby, You Look So Heavenly (#ulink_3c2dac46-c13e-59e2-a4a5-a27ea71fd9c8)

Childhood and family photos, courtesy of the Harry family

One visit, when I was a baby, my doctor gave me a lingering look. And then he turned in his white coat, grinned at my parents, and said, “Watch out for that one, she has bedroom eyes.”

My mother’s friends kept urging her to send my photo to Gerber, the baby food company, because I was a shoo-in, with my “bedroom eyes,” to be picked as a Gerber baby. My mother said no, she wasn’t going to exploit her little girl. She wanted to protect me, I suppose. But even as a little girl, I always attracted sexual attention.

Jump-cut to 1978 and the release of Louis Malle’s Pretty Baby. After seeing the movie, I wrote “Pretty Baby” for the Blondie album Parallel Lines. Malle’s star was the twelve-year-old Brooke Shields, who played a kid living in a whorehouse. Nudes scenes abounded. The movie created a firestorm of controversy regarding child pornography at the time. I met Brooke that year. She had been in front of the camera since she was eleven months old, when her mother got her a commercial for Ivory Soap. At age ten, with her mother’s consent, she posed naked and oiled up in a bathtub for the Playboy Press publication Sugar and Spice.

One time, when I was around eight years old, I was put in charge of Nancy, a little girl of four or five, whom my mother was watching for the afternoon for her friend Lucille. I was to walk Nancy over to the municipal pool, which was about two blocks from my house, and my mother was going to join us there. I guided Nancy down the busy thoroughfare that bordered the end of the town, holding her little hand for safety. It was a seriously hot day, the bright hard sun bouncing up off the sidewalk at us. We turned a corner and were about to pass this parked car, with its passenger window rolled all the way down. From inside came this voice: “Hey, little girl, do you know where such-and-such is?” A messy-looking, rather nondescript older man, with washed-out and faded hair . . . He had a map over his lap, or maybe it was a newspaper. He was asking all kinds of questions and directions, and his one hand was moving around underneath the paper. Then the paper slid off and out popped his penis. He had been playing with it. I felt like a fly on the edge of a spiderweb. This wave of panic flushed through my body . . .

I freaked and fled to the pool, dragging Nancy along, her tiny feet trying to keep up. I rushed up to my teacher, Miss Fahey, who was at the entrance, making sure that everyone had their pool pass. I was really upset, but I just couldn’t tell her about this creep showing me his penis. I said, “Miss Fahey, please watch Nancy, I have to go home,” and I ran back. My mother was beside herself. She called the police. They came screeching up to the house and my mother and I rode around town in the back of the squad car, trying to spot the pervert. I was so small, I couldn’t see over the back of the seat. I just sat there as we rode around and around, peering over the seat as best I could, my heart pounding and pounding.

Well, that was an awakening. My first indecent exposer, although my mother said there were others. Once, we were stalked at the Central Park Zoo by a man in a trench coat who kept flapping it open. Because of their frequency, over time, these kinds of incidents started to feel almost normal.

For as long as I can remember I always had boyfriends. My first kiss was given to me by Billy Hart. How sweet to be initiated by a boy with such a name. I was stunned, alarmed, angry, pleased, excited, and enlightened. Maybe I didn’t realize all of this at the time and I probably couldn’t have put it into words; nevertheless, I was confused and conflicted. I ran home to tell my mother what had happened. She gave me a mysterious smile and said it was because he liked me. Well, up to that point I had liked Billy too, but now I was embarrassed and got all shy around him. We were very young, maybe five or six years old.

And then there was Blair. Blair lived up the street and our mothers were friends, so he and I sometimes played together. This one time, we went up to my room and we ended up sitting cross-legged on the floor, Indian style, facing each other and taking a good look at each other’s “things.” This was innocent too. I was about seven and he was maybe eight and we were curious. I’ve always been curious. Well, Blair and I must have been quiet for too long because our mothers came in and we got caught. They were more embarrassed than angry, being longtime friends, but Blair and I were never encouraged to play with each other again.

My parents held to traditional family values. They stayed married for sixty years, holding on through all the ups and downs, and they ran a tight ship at home. We went to the Episcopalian church every Sunday and my family was very much involved in all the church activities and its social life. Which may have been why I was in the Girl Scouts and was definitely why I was in the church choir. Fortunately, I really enjoyed singing, so much so that I won a silver cross when I was eight for “perfect attendance.”

I guess it’s not really until you approach your teens that you get all these doubts and questions about religion. I must have been twelve when we stopped going to church. My father had had a big falling-out with the rector or the minister. Anyway, by that time I was in high school and probably much too busy to go to choir practice.

I hated the whole process of arriving at a new school. It wasn’t the school itself. It was just a little local school, fifteen or twenty kids in each grade, and I wasn’t afraid of studying; I’d learned the alphabet before kindergarten. First, for some reason, I would get incredibly anxious about being late. Maybe I needed approval that badly. However, my bigger problem was separation—being separated from my parents. Abandonment. It was traumatic. I would be a nervous wreck. My legs would turn to jelly and I struggled to climb the stairs. I guess somewhere in my subconscious, a scene was playing on a loop of a parent leaving me somewhere and never coming back. That feeling never really went away. To this day, when the band separates at the airport and we all go our different ways, I still get that gut reaction. Separation. I hate parting with people and I hate goodbyes.

Things were changing at home. At the age of six and a half, I had a baby sister. Martha was not adopted; my mother gave birth to her after a really rough pregnancy. Around five years before she adopted me, my mom had had another baby girl, Carolyn, premature I think, who died of pneumonia. There was a boy too, whom she miscarried. Then a drug came along that helped her go to term. Martha was premature, but she survived. My father said her head was smaller than the palm of his hand.

You might have thought that the arrival of another pretty baby in my house—and one that actually came from my mom—might have triggered my insecurity and abandonment fears. Well, at first I was probably a little disturbed by not being the complete focus of all my mother’s attention, but more than anything else I loved my sister. I was always very protective of her because she was so much younger than me. My father called me his beauty and my sister his good luck, because when she was born his fortunes changed.

Sean Pryor

Childhood and family photos, courtesy of the Harry family

I scared my parents one morning. It was probably the weekend and they were sleeping in a little bit. Martha had woken up and was crying for her bottle. So, I slipped down to the kitchen and heated up the bottle, which I had watched my mother do so many times, and I brought it upstairs and gave it to her. My parents freaked when they discovered what I was up to, convinced that I was scalding her. But there Martha was, happily chomping down on that nipple . . . So, I found myself with a new job, which became my morning contribution to all the many routines in our Hawthorne home.

Hawthorne was the center of my universe then. We never left. I didn’t understand about finances as a young child and I didn’t grasp that there wasn’t much money and my parents were trying to save up to buy a house. All I knew was that I had a powerful yearning to travel. I was so curious and restless all the time. I loved it when we would all pile into the car and drive to the beach on our vacations, which almost always meant visiting family.

One year—I must have been eleven or twelve—we went on vacation to Cape Cod. We were staying in a rooming house with my aunt Alma and uncle Tom, my dad’s brother. My cousin Jane was a year older than me and we had lots of laughs, giggling and playing together. One particular day, while our parents were downstairs, we sat in front of the mirror fixing our hair, as we loved to do. But this time, we called down and said we were going for a walk. As soon as we were far enough away, we took out our stolen pile of lipstick and eye makeup and carefully transformed ourselves into these hot-looking babes. We probably looked like two nubile characters from The Rocky Horror Picture Show. We stopped at a stand to buy some lobster rolls, then strolled on down the street, admiring our reflections in the shop windows. But we weren’t the only ones admiring ourselves: these two men approached us and started to come on to us. They were way, way older than us. Both in their late thirties, we would discover. Pretending to have no idea that we were actually preteens, they invited us out that night and said they’d meet us at our place. Of course, we were not going to tell them our address, but we played along and said we’d come back and meet them somewhere else.

That night, our faces scrubbed clean, we were in bed playing cards and wearing our baby-doll pajamas when there was a knock on the door. It must have been eleven o’clock. Without our noticing, the two guys had followed us home and they were there to pick us up. I think by then our parents had enjoyed a few cocktails and they just thought it was hilarious. So, they threw open the bedroom door and there we were, children. It turned out that we didn’t get into too much trouble. It also turned out that one of our suitors was a very famous drummer, Buddy Rich. I later discovered that, besides being a close friend of Sinatra’s, Buddy had been married at the time to a showgirl named Marie Allison. They remained together until his death from a brain tumor at age sixty-nine, in 1987. Shortly after his visit, a large envelope arrived in the family mailbox. Inside was an autographed, eight-by-ten black-and-white glossy of my Buddy, who was once hailed as “the greatest drummer who ever drew breath.”

Interestingly, Buddy Rich returned as a presence in my life decades later, when some of my close colleagues in the British rock scene—like Phil Collins, John Bonham, Roger Taylor, and Bill Ward—would count Buddy as their greatest influence . . . My life has so often circled back on itself in these intricately obscure ways.

There was a whole lot going on that year, now that I look back on it. It was the year I made my stage debut. It was a sixth-grade school production of Cinderella’s Wedding. They didn’t give me the part of Cinderella, but I was the soloist who sang at her wedding to the prince. The song I sang was “I Love You Truly,” a big ballad featured in the movie It’s a Wonderful Life. When I came onstage I had the worst stage fright—all those eyes staring at me, kids, teachers, parents; my mom and dad were there with my sister, Martha. But I pulled it together. I just wasn’t a natural performer or a big personality. I think I had a big personality inside, but I didn’t have one on the outside; I was very shy. Whenever the teacher would come up to me and say, “You were so good!” my misfit mind added an unspoken, “Not really, have you lost your mind?”

My experience with ballet wasn’t really much better. Like a lot of little girls, I wanted to be a ballerina. I’d been exposed to Margot Fonteyn and other wonderful dancers by my mother, who’d had a cultured childhood and wanted me to have some of that experience. But in ballet class I always felt very self-conscious because I was convinced I was too fat, which I wasn’t at all. I had an athletic body. But I wasn’t birdlike and delicate like all the little girls who looked so cute and perfect and like each other in their little tutus. I felt that I fucked the whole thing up by being so chubby and standing out.

The biggest thing that happened that year was that my family finally bought that little house and we moved. Our new neighborhood was not much different from our old one and it was not very far away. But it was in another school district, which meant that I had to switch schools. It was not easy being the new kid in sixth grade. I didn’t know anybody there, apart from two girls I knew from Girl Scouts. I had no friends. Even more startling, Lincoln School had a whole different curriculum, which was much more focused on academics than my old school, so I had a lot of work to do to catch up. But there was a silver lining to this very dark cloud, I told myself. Which was: no more Robert.

Martha and me.

Childhood and family photos, courtesy of the Harry family

Sean Pryor

Robert was a new boy at my old school and he was a different kind of kid, kind of wild and dressed in clothes that were usually too big for him. His clothes were very messy. His hair was messy too. Even the features on his face were messy. He also had a problem with wetting his pants. His sister Jean, on the other hand, was a model of perfection with pretty, curly hair; she was nicely dressed and brainy, maybe top of her class. Robert’s grades were so low they couldn’t be measured. He was the class freak. Mostly he was avoided or made fun of.

Perhaps because I was less cruel to him than the other kids, Robert became fixated on me. He started following me home. Sometimes he would leave me little presents. This went on and on. But since we were in a different house and I didn’t go to that school anymore, I thought I would be free from his hauntings. I wasn’t. We had been in the new house for just a few days and I was standing at the front door. My sister, Martha, asked me a question about Robert and I just let rip. I said exactly what I felt about his unwanted attentions. I did not know that Robert was outside, hiding behind a tree. He heard everything. I will never forget the look of astonishment and pain on that boy’s face as he slipped away. I felt awful. I never saw him again, but from what I heard he remained a social catastrophe and in high school he hung out with another outcast. They would go hunting. A few years later, when they were fooling around with guns in Robert’s basement, his friend shot him dead and this was ruled an accidental shooting, kids playing with guns.

Summers were for wandering in the sun, my mind running free. The days so muggy it felt like being swaddled in a hot compress. I swam and did all those summer things and I read a lot—everything I could get my greedy little hands on. Literature was my great escape and my expedition into other worlds. I hungered to learn about everything and everywhere that was beyond Hawthorne. And there were family outings to see my grandparents and aunts and uncles. Just the usual kid stuff, all of it a blur now, except for that deep, sinking sensation of dread in my stomach at the thought of going back to school.

Hawthorne High was my third school. I can’t say I liked it any better than the others. It made me nervous, but I did like the sense of freedom and independence that came along with going to high school, where you’re treated a little more like an adult. My parents made it pretty clear that they wanted me to be an achiever. And if they hadn’t pushed me in this way, I think I might have just wandered off into dreamland. I was still trying to discover who I was, but I knew even then that I wanted to be some kind of artist or bohemian.

My mother used to make fun of artists. She would put on a WASP-y accent, make one wrist go limp, and exclaim, “Oh, you are such an artiste.” That made me even more nervous and annoyed, and there’s nothing worse than an angry and pissed-off teenager. Now, my life was not awful; it was blessed. My parents heaped so much love on me. But I felt like I had a split personality with half of the split missing, submerged, unexpressed, unreachable, and hidden.

I didn’t make trouble at high school and my grades, although not straight A’s, were good. I actually liked the classes where we were given literature to read, and I got good at geometry, because it was like figuring out a puzzle. One of the first things I noticed about high school was how much more grown-up the girls were, particularly their clothes. I immediately became extremely conscious of my clothes, which were either too dull, too constricting, or both. My mother dressed me like a little preppy girl, clean-cut American, with clunky shoes. What I wanted to wear was tight black pants and a big loose shirt or a back-to-front sweater, like the beatniks, or something tough looking and ballsy. Or at least something jazzier, with bright colors or a fringe. But when my mom took me shopping she would go straight for a white blouse with a round collar and a navy-blue skirt. Basically, when it came to clothing choices, my mother and I were always poles apart.

As I got older, life looked up. I started making my own clothes. I would fool with things, some of them hand-me-downs, tearing the sleeves off of one piece and sewing them onto another. I remember showing this one concoction to perhaps my first friend, Melanie, who remarked, “It looks like a dead dog.” I have no idea where that dead dog went.

But for the longest time, I held on to one of those dresses I inherited from my mother’s friends’ daughters. I see it clearly now: this pink cotton summer dress with its full skirt and its great movement. Later, my father would take me to Tudor Square, one of his clients in the garment industry. And I remember getting a couple of brightly colored, really cool tweedy plaid outfits that I kept for a long time.

By the time I was fourteen, I was dyeing my hair. I wanted to be platinum blond. On our old black-and-white television and at the theater where they screened Technicolor movies, there was something about platinum hair that was so luminescent and exciting. In my time, Marilyn Monroe was the biggest platinum blonde on the silver screen. She was so charismatic and the aura she cast was enormous. I identified with her strongly in ways I couldn’t easily articulate. As I grew up, the more I stood out physically in my family, the more I was drawn to people that I felt I related to in some significant way. With Marilyn, I sensed a vulnerability and a particular kind of femaleness that I felt we shared. Marilyn struck me as someone who needed so much love. That was long before I discovered that Marilyn had been a foster child.

My mother colored her hair, so there was always peroxide in the bathroom. On my first attempt I didn’t get the mix right, so I ended up bright orange. I must have had at least a dozen different colors after that. I was also experimenting with makeup. I went through a beauty mark phase; I’d show up at school, my face looking like one of those connect-the-dots puzzles. My skills improved, but I still enjoyed experimenting.

At fourteen I was a majorette. I’d dress up in the tasseled boots, the tall hat, and the skirt that didn’t cover much at all, and I would march and twirl a baton. I was better at marching than baton twirling. I would always drop the baton, which meant I had to bend and pick it up, and which obviously added something extra to the performance.

I also joined a sorority, because that was what you were supposed to do, and it was the cool thing to do. These high school sororities and fraternities were curious groups—a sociologist or anthropologist would have a field day with them, I am sure. Each group had a strong identity and each was very competitive. But there were plenty of pluses too. When you’re a high school girl looking for an identity, a sorority gives you somewhere to belong. The girls ranged in age from freshmen to seniors and all called each other sister, so there was a lot of affection and camaraderie. The younger ones just needed to survive being pushed around on initiation night by their “sisters.”

Later on I quit. I don’t remember exactly how it went down, but I had some friends that they didn’t think were appropriate. I was offended by their telling me who I could and couldn’t have as friends and I left.

Though I wasn’t a troublemaker, I sometimes got detention—not for anything really bad, just cutting school. I’d go to Stewart’s Drive-In for a root beer and never come back. The worst thing about detention was having to sit there and write one stupid sentence over and over, thousands of times. I noticed that this one girl, K, would initial every page at the top with “JMJ.” When I asked why she did that, a little surprised at my ignorance, she let me know in no uncertain terms that the letters stood for “Jesus, Mary, and Joseph.”

K had been kicked out of Catholic school. So sitting next to her was the best thing about detention. She was a big, tough, gum-chewing Irish girl with sandy red hair and pimply teenage skin. She was always in detention for fighting. She had been labeled the town pump, the blow job queen, whether she deserved it or not. In small towns like ours, you could end up being caught forever in cruel traps. Small towns’ stigmata. However, K and I became friends. I was always interested in anyone who was so out front like that. I was fascinated by their danger. I wanted to be dangerous too but still wanted to protect myself. So I wasn’t dangerous—yet.

There was another friend whose mother was a nurse. One day she said she was going to Florida for a vacation. I said, “Gee, you’re so lucky!” I was dying to get out of this town and the idea of going to Florida for a vacation was very exotic—especially since I was born in Florida and had never been there since. But she actually went to Puerto Rico for an abortion. When she came back I looked at her and said, “My God, you don’t have a tan.” She just glared at me. I didn’t know that she had gotten knocked up. No one said anything.

I had a lot of boyfriends, usually one at a time, because that was the way it was done in this kind of small, uptight little town where reputations were made and lost in seconds. I would see one boy for a month or two and then I would see someone else. I really loved sex. I think I might have been oversexed, but I didn’t have a problem with that; I felt it was totally natural. But in my town in those days, sexual energy was very repressed, or at least clandestine. The expectation for a girl was that you would date, get engaged, remain a virgin, marry, and have children. The idea of being tied to that kind of traditional suburban life terrified me.

Some nights I would get a ride with a girlfriend and we would go to Totowa borough next to Paterson where my grandparents lived. Totowa had a notorious reputation back then and its main street was sometimes referred to as “Cunt Mile.” It was the thoroughfare where a lot of kids hung out. All the girls would walk around looking as hot and trashy as possible and the guys cruised the street looking at the girls. I would find a guy I liked and make out with him. They had great dances up there too. The town I came from was all white kids, but at these dances there was a really integrated crowd. And the music was just great because they played a lot of hot black music and everyone danced their ass off. I loved dancing. Still do.

For a while now, I had taken to going to New York; the bus fare was less than a dollar then. My favorite place to wander was Greenwich Village. I’d get in around ten in the morning, when all the bohemians and beatniks were still sleeping and everything was closed. I would just walk around, not looking for anything in particular, looking for everything really, and ingesting and digesting it all. Art, music, theater, poetry, and the sense that everything was up for grabs, you just had to see what fit. I was desperate to live in New York and be an artist. I could not wait for high school to end.

Well, finally it did end, in the summer of ’63. They held the graduation ceremony outside on the football field in the back of the high school. It was boiling hot that day, ridiculously hot, and I was melting in my cap and gown. I guess I felt off balance all through high school, so it seemed appropriate for the graduation ceremony to end this way.

Family. Christmas.

Childhood and family photos, courtesy of the Harry family

So, this is where I pack my suitcase, wave goodbye to the folks, get on the bus, and watch through the window as New Jersey fades into the distance and the New York City skyscape looms? Well, actually no. I went to a junior college.

Centenary College in Hackettstown, New Jersey, was a women’s Methodist school run by some very old Southern ladies. Essentially, it was a finishing program to groom you for a respectable married life. I once referred to it as a “reform school for debutantes” and that’s really what it was to me—only I was no debutante and I did not want reforming. My reformation would be much, much different.

It was always planned that I would go to school. I told my parents that I wanted to go to an art school, preferably the Rhode Island School of Design—but it was a four-year program and it was beyond the budget. So, going to a two-year college was a compromise with my family, and that meant Centenary.

I wasn’t sure at all that I wanted to go to college. I just wanted to get out in the world and be an artist. I think my mother wanted me to go there because she felt that, since I was so shy, I wouldn’t do well anywhere else, and if I got homesick, it was only an hour and a half from home. So, in the fall I left for Hackettstown. I moved into a dorm, where I shared a room the first year with a girl named Jan and later with Karen—when they switched with each other. The second year, I roomed with a very smart, sweet girl named Carol Boblitz.

Now, the college did have a few good professors. Dr. Terry Smith taught American literature, which I absolutely loved—I loved Mark Twain and Emily Dickinson. And I liked the art teachers, Nicholas Orsini and his wife, Claudia. I was doing some painting and drawing while I was there. It wasn’t the kind of school where you had to work too hard. You could take very easy courses if you wanted and you would still be going to all the social events at other colleges, which was basically a dating service.

In my second year I went out with a guy called Kenny Winarick. His grandfather built the enormous Concord Resort Hotel in the Borscht Belt in the Catskills. They had first-rate entertainment—Judy Garland, Barbra Streisand—and lots of Jewish families would go. One day Kenny asked me, “Do you want to go to the mountains?” which is what they called the Catskills, but I was so naive I thought we were going hiking. He took me to this magnificent hotel, where everyone was dressed to the nines and I was in funky jeans and trying to be cool.

After we had gone out for a while, Kenny brought me to visit his mother at her place in New York. As I stood gazing out from the terrace of her wonderful apartment, my dreams of big-city living took further flight. It was just right. Just perfectly right. The spacious rooms weren’t overdecorated or too, too proper. A real environment where real people lived. People who loved being New Yorkers. Her prewar apartment building was named the Eldorado, at 300 Central Park West.

At the time, this mythological reference meant practically nothing to me, except that it was beautiful and exciting and something out of my wildest dreams. It was too soon for me to be drawing parallels between my own quest for an identity and the conquistadors’ quest for their fabled city of gold. But looking back, it was an ideal parallel to my entering the allure of New York through the gilded portals of the Eldorado. It was my personal sixties happening, as I joined the growing band of latter-day conquistadors searching for special treasure in the new city of beckoning promise.

All this sounds quite serious. And in a way it was. I was intense and determined but also floating in an often-turbulent sea of mixed emotions. I don’t think I was bipolar or depressed or schizophrenic or any such thing. I think I was normal enough, but in a time of expanded consciousness we were looking at the world in new and different ways.

Then there was also the psychedelic experience. Kenny’s mother, Gladys, was a psychoanalyst. She had a strength and curiosity and vitality that I absolutely loved. Her kids had an assurance and sense of humor about themselves that was way ahead of most of the people back home. Simply put, it was sophistication. As an analyst, Gladys was in on the latest lectures and symposiums and talks related to her field. So, she got an invitation for a session with Timothy Leary. She couldn’t go to this one, so Kenny and I went in her place. I think Leary may still have been teaching at Harvard or was about to be fired—and Alan Watts was there too. Leary’s book The Psychedelic Experience: A Manual Based on the Tibetan Book of the Dead had recently been published and I guess the idea behind these simulated “experiences” was to further legitimize their passion for LSD and its therapeutic potential.

The day came for our “trip” and we went to one of the most beautiful town houses I’d ever seen. It was on the Upper East Side of Manhattan, between Madison and Fifth Avenues. A truly elegant building with a carved entry and wrought iron railings with a barred doorway. We were led to a ground-floor room, where a small circle of people were sitting on the carpet. Leary was explaining the chakras and the stages of the experiment and encouraged us to relax and go with it. There were no drugs, no drinks, no food, only suggestions and directions about what this LSD trip could be like. In fact, it was based on a spiritual journey through different states of consciousness, known as the bardo.

At this time, Leary’s ideas were breathtakingly new and he had gotten some really dicey press about his teachings and drug use. We sat in the circle with the others and listened to Timothy chanting and speaking, guiding us through what might have been a mind expansion—if we could let ourselves go with it. Well, Kenny and I both were curious and wanted to learn something, so we hung in with the lecture. It went on forever and I was hoping there would be a snack at some point, but no such luck. We sat there for hours while Professor Leary and Alan Watts spoke about these levels of the mind. Finally we were all asked to interview each other.

There were all kinds of people there that day, not just hipsters or students. All kinds of businessmen and women; doctors, local and foreign; some nicely dressed uptown types; a few art-world people from the neighborhood; and analysts, of course. There was one man who made me nervous because he just radiated resistance. He held himself apart as if simply observing. He wore a white business shirt and dark gray trousers. He was balding and clean-cut. Of course, I was put opposite him for the interviews—the “getting to know you” part of the afternoon. I was uptight, not nice at all, and starving by then. So, I had it in for this poor man from the get-go and quizzed him in a way that he wasn’t expecting. It turned out he was there in some official capacity from either the CIA or the FBI. Which came as a jolt to Leary . . .

Kenny’s father was interesting too. He had a company called Dura-Gloss that made nail polish. A brand that my mother used. I used to love the little bottles it came in. It seemed a bit synchronistic that I should be seeing this guy. My mother must have thought so too, because she was putting the screws on Kenny to get serious. I thought he was great, but I wanted to experience what the world was and find out who I was before settling down. I think he did too. He went on to get his master’s degree and in a way I did too, eventually.

Me, I graduated with an associate of arts degree. I found a job in New York, but I couldn’t live there, I had no money, so I commuted back and forth, which I hated. I spent hours looking for an apartment in the city, but I couldn’t find anything remotely affordable. I guess I was moaning about it to my boss Maria Keffore at work. Maria, who was a very pretty Ukrainian woman, said, “Oh, you don’t have to worry. Come see my apartment. The rent is only seventy dollars a month.” OH MY GOD, how can it be so cheap, I thought, what must it be like? Well, it was fantastic. It was on the Lower East Side, which was a Ukrainian and Italian neighborhood at that time, and under rent control.

With Maria’s help I found an apartment with four rooms for just $67 on St. Mark’s Place. That first night in my new home, lying on the bed listening to the sounds of the street floating through my window, I felt like I was finally, twenty years into my life, in the place where my next life would begin.

They used to say I looked European.

Childhood and family photos, courtesy of the Harry family

Sean Pryor

3 (#ulink_2f782194-896d-5580-aa5a-5891e835dded)

Click Click (#ulink_2f782194-896d-5580-aa5a-5891e835dded)

Dennis McGuire

I hated my looks as a kid but couldn’t stop staring. Maybe there were one or two pictures that I liked, but that’s all. For me, capturing those looks on film was a horrible experience. Eventually the peeping, secretive, naughty aspect of it made being photographed all right, but voyeurism was not part of my vocabulary as yet. How could I know then that this face would help make Blondie into a highly recognizable rock band?

Does a photograph steal your soul? Were the aboriginal people right? Are photographs part of some mystical image bank, a type of visual Akashic record? A source of forensic evidence to examine the hidden, darker secrets of our souls, perhaps? Now, I can tell you that I’ve had my picture taken thousands of times. That’s a lot of theft and a lot of forensics. Sometimes I read things into those pictures that no one else seems to see. Just a tiny glimpse of my soul maybe, a passing reflection on a piece of glass . . . If you were me, by now you might be wondering if you had any soul left at all. Well, I had one of those Kirlian photographs taken once at a new age fair—and there supposedly was my soul, my aura, staring back at me. Yes, maybe there is still some of my soul to go around.

I was working in an almost soulless place: a wholesale housewares market at 225 Fifth Avenue, a huge building full of everything you can think of that had to do with housewares. My job was selling candles and mugs to buyers from the boutiques and department stores. This had not been part of the dream. I started thinking that since I was pretty—well, my high school yearbook had named me Best-Looking Girl—maybe I could get some modeling work. I’d met two photographers, Paul Weller and Steve Schlesinger, who did catalog work and paperback book covers, and I decided I would make a portfolio. My modeling book had shots running from hairstyles to yogic poses in a black leotard. What was I thinking? What kind of jobs could I possibly get with these weird photographs? Answer: one and done.

Then I saw a blind ad in the New York Times looking for a secretary. It turned out to be for the British Broadcasting Corporation. This was my first link to what would become a long, lovely relationship with Great Britain. They gave me the job on the strength of the sensational letter that my uncle helped me write. Once they had me, they realized that I wasn’t very good at what I was supposed to do, but they kept me anyway and I grew into the job. I learned to operate a telex machine. I also met some interesting people—Alistair Cooke, Malcolm Muggeridge, Susannah York—who came into the office/studio for radio interviews.

Plus, I met Muhammad Ali. Well, not exactly met him. “Cassius Clay is coming in to do a TV interview,” they said, so I snuck around the corner and wow, I saw this big, beautiful man walk into the TV studio and close the door. It was a soundproofed room with a small window way up high, so I decided, being athletic, that I was going to grab the windowsill and pull myself up and watch the taping. But, as I pulled myself up, my feet kicked the wall with a thud. In a flash, Ali’s head whipped round and he stared right at me. He nailed me and I was transfixed. He’d responded with the animal instinct and lightning reflexes of the supreme champion he was . . . I quickly dropped down to the floor, shocked and excited by the primal exchange. I could have gotten into trouble, particularly if they had already started to record, but fortunately no one else in the room had even noticed.

The offices for the BBC New York were in the International Building at Rockefeller Center, directly across from the monumental St. Patrick’s Cathedral. When I was working at the BBC, I believe Fifth Avenue was a two-way street, and the traffic was immense. A block south of the cathedral was Saks Fifth Avenue. In front of the International Building was and still is the enormous bronze statue of Atlas holding up the world. Behind it is Rockefeller Plaza, where the skating rink and the big Christmas tree are located during the holidays. During the summer the rink becomes an outdoor café. Directly behind the rink is the NBC building, with the Warner Bros. offices nearby too.

Strolling past the store windows and through the canyons of buildings was always interesting, and I made it a point to go over to visit one of my favorite characters, “Moondog.” This tall, bearded old man with his horned Viking helmet was a vision. He stood on the corner of Sixth Avenue and Fifty-Third in his long reddish cape holding his spearlike pole, selling booklets of his poetry. Moondog now has his own Wikipedia page, but back then few people who walked past him knew who the fuck he was. Most people steered clear of or didn’t even notice him—just another crazy “weirdo” to avoid or blank out.

Some thought he was an eccentric, blind, homeless man, but he was much more. Moondog was also a musician. He had an apartment uptown but kept his image and his privacy closely guarded. He designed instruments and also recorded, and he became adored by most New Yorkers. A beloved fixture, a true New York character who sometimes recited his poems to the businessmen and tourists hurrying past him. He was freaky but he was fondly called the Viking guy—even if no one knew about all his artistic achievements.

And then there were the more sinister types: the silent men in black selling small newspapers or booklets. They were serious, intense, kind of scary, which made them all the more intriguing, of course. They called themselves “the Process”—short for the Process Church of the Final Judgment—and were scary but compelling in their intensity. Never alone, they stood in groups on the midtown corners in their quasimilitary black uniforms.

Scientology wasn’t so well-known at the time, but cults, communes, and radical religious movements would come and go all the time. I wasn’t aware completely of Scientology or the Process Church, but I respected the commitment it took for these guys to stand and deliver in midtown to a straight bunch of bros. They roamed around downtown as well, among much more sympathetic audiences in the West and East Village.

It was a business, it was a religion, it was a cult; maybe it still is but I don’t think they call it the Process anymore.

I had come to the city to be an artist, but I wasn’t painting much, if at all. In many ways I was really still a tourist, just experiencing the place, having adventures, and meeting people. I experimented with everything imaginable, attempting to figure out who I was as an artist—or if I even was one. I sought out everything New York had to offer, everything underground and forbidden and everything aboveground, and threw myself into it. I wasn’t always smart about it, admittedly, but I learned a lot and came out the other side and kept on trying.

Drawn to music more and more, I didn’t have to go far to hear it. The Balloon Farm, later called the Electric Circus, was on my street, St. Mark’s Place, between Second and Third. The old building the shows were held in had some serious history: from mob hangout, to Ukrainian nursing home, to Polish community hall, to the Dom restaurant. The whole neighborhood was Italian, Polish, and Ukrainian. Every morning, on my way to work, I would see the women in babushkas with their buckets of water and brooms, washing the sidewalks clean of whatever went on the night before. A ritual carryover from the old country.

Trying to keep time at the Mudd Club.

Allan Tannenbaum

One evening, as I walked past the Balloon Farm, the Velvet Underground was playing, so I went inside and into this brilliant explosion of color and light. It was so wild and beautiful, with a set designed by Andy Warhol, who was also doing the lights. The Velvets were fantastic. John Cale brilliant, with his droning, screeching electric viola; proto-punk Lou Reed with his hypercool, drawling delivery and sneering sexuality; Gerard Malanga, gyrating around with his whip and leathers; and the deep-voiced Nico, this haunting, mysterious Nordic goddess . . .

Another time, I saw Janis Joplin play at the Anderson Theater. I loved the physicality and the sensuality of her performance—how her whole body was in the song, how she would grab the bottle of Southern Comfort on the piano and take a huge slug and belt out her lines with crazed Texan soul. I’d never seen anything like her onstage. Nico had a very different approach to performing; she just stood there, still as a statue, as she sang her somber songs—much like the famed jazz singer Keely Smith, with the same stillness but a different kind of music.

I would go see musicals and underground theater. I bought Backstage magazine and I’d take notes on all the auditions and then join the endless lines of hopefuls who, along with me, never got past first base. There was also a strong jazz scene on the Lower East Side with haunts like the Dom, the renowned Five Spot Cafe, and Slugs’. At Slugs’, in particular, you’d get to hear luminaries like Sun Ra, Sonny Rollins, Albert Ayler, and Ornette Coleman—and find yourself at a table next to Salvador Dalí. I met a few of the musicians. I remember showing up and sitting in on a couple of loose, “happening”-like gatherings, the Uni Trio and the Tri-Angels—free, abstract music where I sang a bit or chanted and banged some percussion instrument or other. That was the same thing we did in the First National Uniphrenic Church and Bank. The leader was a guy from New Jersey named Charlie Simon who later christened himself Charlie Nothing. He made sculptures out of cars that he called “dingulators” that you could play like guitars. He also wrote a book called The Adventures of Dickless Traci, a detective novel with a weird sense of humor, but that was later. He was multidimensional in music, art, and literature—a free spirit who was more beat than hippie. And he made me curious. I liked the curiosity because I was curious myself. If any other guy had come along and played me a track from a Tibetan temple with men giggling and growling in the background, I would have liked him too.

The sixties were the age of happenings. It was also the time of a great New York loft scene where so many of these wonderful parties and happenings took place. The lofts down below Canal Street and in Soho were former manufacturing spaces and most were illegal living, but they were very cheap, $75 or $100 a month, so all the artists rented these enormous two-thousand-square-foot spaces. That’s where we played our anti-music music. Charlie played saxophone. Sujan Souri, a jolly, Buddha-bellied Indian man who was a philosophy student, tapped away on the tablas, and Fusai, a countrywoman to Yoko Ono, sort of sang in a very high voice. I don’t know if I banged sticks together or screamed; probably both. Our drummer, Tox Drohar, was wanted for something somewhere—and I surmised he was hiding out, which forced him to change his name and disappear. And then he left to go live with his girlfriend in a little shack in the Smoky Mountains on the great Cherokee reservation.

My boss at the BBC told me I had two weeks’ vacation. I wasn’t allowed to choose the dates and they gave me two weeks in August. It was the hottest, most awful time of summer. Phil Orenstein was an artist working in plastic who made inflatable pillows, furniture, and bags with silk-screened paintings on them. He needed help assembling the straps on some of the bags. So, there I was, in this little plastics factory, tying knots and cutting the ends off with a hot knife. But the fumes from the plastic in that heat were unbelievable. I was seeing spots. I think I lost a piece of my mind from doing it.

But I had those two weeks off, so Charlie Nothing and I decided to take my saved-up $300 and go visit Tox and his very, very pregnant girlfriend, Doris, in Cherokee, North Carolina. We drove down and stayed there for a week and managed to spend my $300. I went back to the BBC covered in mosquito bites, still seeing spots from the plastic fumes and too much pot. But it was a fair exchange: the Smoky Mountains were magnificent and I would have never gone to Cherokee on my own and sat around in rocking chairs with old-timer Indians as they chewed tobacco and spat juice into paint cans.

In 1967, the First National Uniphrenic Church and Bank released an album, The Psychedelic Saxophone of Charlie Nothing, on John Fahey’s record label Takoma. But I had left by then. I also quit the BBC, which I felt was too time consuming. I got a job at Jeff Glick and Ben Schawinski’s Head Shop on East Ninth Street—the first-ever head shop in New York City. Pipes, posters, bongs, black-light bulbs, tie-dyed T-shirts, incense, the usual stuff, only then it was unusual. Right next door was a peculiar storefront with filthy windows plastered with button cards yellowed from age. The crone who had the store lived in the back. Wrapped in her shawl, she looked like an image from a fairy tale. Veselka, which translates to “rainbow,” is a no-frills, twenty-four-hour-a-day Ukrainian eatery next door. When the old woman eventually died they incorporated her store, enlarging their restaurant. The Head Shop was just around the corner from my apartment on St. Mark’s place, so no commute, and it was fun. All the downtown people, the uptown people—in fact, everyone—came in there and it was a really good scene. The Head Shop was an ideal place to meet people who were looking to break some rules.

Ben’s father was a Bauhaus painter and Ben was a sculptor, furniture designer, and builder, easygoing, very cute, and a ladies’ man. We had started going out and we were pretty interested in each other. Eventually he met these guys from California who had a commune, in Laguna Beach I think. He made all these plans to move out there and be with these people and he wanted me to go with him. I really liked him, but I couldn’t drop everything and blindly follow him. I was still working on music and I was really upset that he wanted me to just throw everything away and go with him. For a while I didn’t know if I had made a mistake or not. Well, a few years later he ended up coming back. He’d had this very fancy Volkswagen bus that he had fitted out beautifully—but as soon as he got out there the van sadly got lost in a mudslide.

One day two handsome, long-haired leather boys strode into my domain—two rebels without a cause. These pierced puppies pressed up against the counter, asking to buy rolling papers and flirting like crazy. I liked the older one, whose name I can’t remember now because he was sweet natured, on the shy side, easy to talk to. The other one, the intense one, just stood staring at me, adding the occasional quip, trying to be funny. That one’s name was Joey Skaggs. Joey came back to the shop a few days later without his friend. It was Valentine’s Day and he had come to see the girl with the heart-shaped lips.