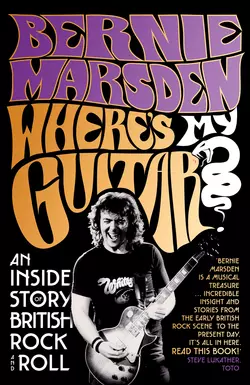

Where’s My Guitar?: An Inside Story of British Rock and Roll

Bernie Marsden

A fascinating insight into the golden-age of 1970s and 80s rock and roll told through the eyes of music legend Bernie Marsden and, most notably, his role in establishing one of the world’s most famous rock bands of all time – Whitesnake. ‘Bernie Marsden is a musical treasure…I don't think people know ALL he has done and just how much he was a part of the early British rock scene to present day. It's all in here. READ THIS BOOK!’ Steve Lukather, Toto Touring with AC/DC. Befriending The Beatles. Writing one of the world’s most iconic rock songs. This is the story of a young boy from a small town who dreamt of one day playing the guitar for a living – and ended up a rock n’ roll legend. It follows Bernie Marsden’s astonishing career in the industry – from tours in Cold War Germany and Franco’s Spain, to meeting and befriending George Harrison and touring Europe with AC/DC. It’s a story of hard graft, of life on the road, of meeting and playing with your heroes, of writing iconic rock songs – most notably the multi-million selling hit ‘Here I Go Again’ – and of being in one of the biggest rock bands of all time. At age 30, Bernie left Whitesnake due to serious conflict with his management, something he explores in this memoir for the very first time. Packed with stories and encounters with the likes of Ringo Starr, Elton John, Cozy Powell, Ozzy Osborne, B. B. King and Jon Lord, this is not just a remarkable look into the highs and lows of being a true music legend, but an intimate account of the revolutionary impact rock and roll music has offered to the world.

(#u8d7235fb-a75f-5c2f-9ea5-df51b3810459)

Copyright (#u8d7235fb-a75f-5c2f-9ea5-df51b3810459)

Dedication (#u8d7235fb-a75f-5c2f-9ea5-df51b3810459)

To Fran,

who always knows where my guitar is.

B x

Contents

1 Cover (#u8911c9a0-ccc3-5601-b95c-1a6a751e59ef)

2 Title Page

3 Copyright

4 Dedication

5 Contents (#u8d7235fb-a75f-5c2f-9ea5-df51b3810459)

6 Praise for Bernie Marsden

7 Introduction

8 Preface

9 1. New York, New York, 1980

10 2. Going to my Home Town

11 3. Look Through Any Window

12 4. Welcome to the Real World

13 5. To the City

14 6. Dance on the Water

15 7. PALS with Deep Pockets

16 8. Whitesnake

17 9. Free Flight

18 10. Come an’ Get It

19 11. Look At Me Now

20 12. Baked Alaska

21 13. Shooting the Breeze

22 14. In the Company of Snakes

23 15. Going Again on my Own

24 Afterword: Guitars and the Sickness They Induce

25 Seminal Moments in my Musical Education

26 Picture Section

27 Acknowledgements

28 About the Author

29 About the Publisher

LandmarksCover (#u8911c9a0-ccc3-5601-b95c-1a6a751e59ef)FrontmatterStart of ContentBackmatter

List of Pagesiii (#ulink_486f6df5-9b88-56da-868c-5776f2480b04)iv (#litres_trial_promo)v (#ulink_3f11faba-e94a-5459-b6ad-11bcf291efe9)ix (#ulink_00ae08ba-5f38-5cee-b69c-6c50aa7279e8)x (#ulink_c35af2e5-6184-524b-a663-0cdb9ff53b50)xi (#ulink_863673df-34f7-5505-88d3-2013ed69a992)xii (#ulink_864ca0a9-00c6-5b8f-a126-73a8391f15e1)xiii (#ulink_c007615b-5d41-52eb-b17c-29850a3910c6)xiv (#ulink_a9d6abe4-8d3f-5d5c-89cf-09806321a4e6)1 (#ulink_4c03df5c-f289-5416-b1e0-0c014c87de29)2 (#ulink_01a5b456-4d37-5ac7-a9d4-74ee04834e95)3 (#ulink_4d703fbc-1da4-5394-b1a7-4f6293e97c77)4 (#ulink_d4d3574a-d553-5333-9c68-5a8b66fab3e2)5 (#ulink_0a7d4582-4079-5fd1-a650-b781ddff2332)6 (#ulink_1a2f61aa-0bab-5e34-8a66-f46de25c582b)7 (#ulink_c88bab39-3373-552a-9210-4270b7cf0fe4)8 (#ulink_50573c43-d9c5-501a-aaf7-3bda7b917e09)9 (#ulink_99cd39ab-8f12-58f4-ba4d-2822538d9c95)10 (#ulink_bf31535d-bfe7-5090-a93d-a8bde1ce828a)11 (#ulink_f2ce19db-8b2b-5c25-a0cf-f5cdc423ddb0)13 (#ulink_5a579eac-4108-5b3d-b14f-fdb2aa02236b)14 (#ulink_d7bab4b6-898f-5c56-8fd7-50e17f13cd6b)15 (#ulink_632e4a1b-d926-59f3-9a88-6c3a9065d9ad)16 (#ulink_63474636-d074-55e3-8712-4786d636d542)17 (#ulink_331ce056-4535-5dba-95ee-d467b4f4a07f)18 (#ulink_babed690-6274-5df7-af7f-7799fc48f890)19 (#ulink_6e50dbd8-59b8-50ec-ab6d-e82ffd29b05e)20 (#ulink_e7004330-c4b3-5fa2-a713-e4e4cc91ebd8)21 (#ulink_095451a6-2d17-568e-9ef9-222a1586aa6c)22 (#ulink_0a14691a-5498-52aa-9b11-bbc7b44d2844)23 (#ulink_05e20062-305f-59d6-a5f1-6de0c60f8333)24 (#ulink_b563d077-6dbf-549d-bc96-31013ca3a8c0)25 (#ulink_35a8954b-692c-514f-b2aa-cf9d05e18e30)26 (#ulink_c796a7f1-0510-56e2-81e2-6f13d76a09ed)27 (#ulink_6326664c-02c0-5b14-88ed-e7522a863831)29 (#ulink_f96ceadd-48b7-5dd8-98da-06f9c51f886b)30 (#ulink_da9b5080-66d7-5799-b437-95addeab3209)31 (#ulink_a34652d3-c274-5e12-9b46-cb42d3200e8a)32 (#ulink_c4dbb948-e545-52b4-a88e-fe0922b707ee)33 (#ulink_7de8f9e0-ffb8-5705-9fb7-df8e439cb358)34 (#ulink_95769e6b-cf8e-50df-8616-5d5bb4e70e05)35 (#ulink_ab1d24b1-b575-5b48-9657-b2b4b0254105)36 (#ulink_4537ab4d-32e1-567d-9b11-8eab3905a907)37 (#ulink_5b8884bc-6626-5b36-bd1b-21f35c51e7ff)38 (#ulink_6f2d5635-2ab5-54ce-8bbd-0b09a522e87e)39 (#ulink_ff30789c-5dd2-5bea-8584-33384d8cbced)40 (#ulink_46eaac65-5186-53cb-970e-2ea8955ab9ef)41 (#ulink_a4dd01d5-cb45-555c-80cc-30b805f6e9e0)43 (#ulink_8ddc02de-9e52-55d4-8c46-1235ee3ca7c3)44 (#ulink_5a15f07f-29fd-5228-abe2-1be74984ddc0)45 (#ulink_2e16962c-1de3-5d2a-8dce-dd62dd2c17f8)46 (#ulink_ff13f3b2-3eb8-586f-a3c3-bcdca76fdf77)47 (#ulink_68aab875-ce7b-5469-8142-5bc6a28685b7)48 (#ulink_c6f276e4-eb49-5582-8422-880c869e6605)49 (#ulink_daac25a3-e648-573b-80f0-feafd9d5fbc2)50 (#ulink_ab90967c-ae9f-5ff1-a821-9a7f3d247e3f)51 (#ulink_8603b2d4-bd3b-5c30-ad41-0480fe501bf9)52 (#ulink_210c55f3-d60f-5038-94d4-2ce258de8d9a)53 (#ulink_cb94ff2c-3c24-5c25-900f-cbf3c57fe72b)54 (#ulink_ae40ff9f-4a90-508a-9154-48b63ab6bcd8)55 (#ulink_5831466c-f040-577e-811b-ef1612dbc20f)56 (#ulink_f9576712-8d1b-54c5-aad5-69ec2f16533b)57 (#ulink_844c3e63-f112-5cd0-9ced-279f1ca1528b)59 (#ulink_0d7301ac-25d5-5880-8011-93cbe2ee2405)60 (#ulink_7d40af4b-e73c-5838-84f9-6178c432b73c)61 (#ulink_962e7a1f-b720-5ad8-8b22-7235f3b2d69f)62 (#ulink_9b4045f7-c860-5360-bb34-764ce198268e)63 (#ulink_182c639d-7847-5d58-baa6-0d0eb2514909)64 (#ulink_ed0ce120-b391-5a8f-a5a0-7be13fe52177)65 (#ulink_0d39a96b-deb5-5c3a-95a1-5c6c899ecd2b)66 (#litres_trial_promo)67 (#litres_trial_promo)68 (#litres_trial_promo)69 (#litres_trial_promo)70 (#litres_trial_promo)71 (#litres_trial_promo)72 (#litres_trial_promo)73 (#litres_trial_promo)74 (#litres_trial_promo)75 (#litres_trial_promo)76 (#litres_trial_promo)77 (#litres_trial_promo)78 (#litres_trial_promo)79 (#litres_trial_promo)81 (#litres_trial_promo)82 (#litres_trial_promo)83 (#litres_trial_promo)84 (#litres_trial_promo)85 (#litres_trial_promo)86 (#litres_trial_promo)87 (#litres_trial_promo)88 (#litres_trial_promo)89 (#litres_trial_promo)90 (#litres_trial_promo)91 (#litres_trial_promo)92 (#litres_trial_promo)93 (#litres_trial_promo)95 (#litres_trial_promo)96 (#litres_trial_promo)97 (#litres_trial_promo)98 (#litres_trial_promo)99 (#litres_trial_promo)100 (#litres_trial_promo)101 (#litres_trial_promo)102 (#litres_trial_promo)103 (#litres_trial_promo)104 (#litres_trial_promo)105 (#litres_trial_promo)106 (#litres_trial_promo)107 (#litres_trial_promo)108 (#litres_trial_promo)109 (#litres_trial_promo)110 (#litres_trial_promo)111 (#litres_trial_promo)112 (#litres_trial_promo)113 (#litres_trial_promo)114 (#litres_trial_promo)115 (#litres_trial_promo)116 (#litres_trial_promo)117 (#litres_trial_promo)118 (#litres_trial_promo)119 (#litres_trial_promo)121 (#litres_trial_promo)122 (#litres_trial_promo)123 (#litres_trial_promo)124 (#litres_trial_promo)125 (#litres_trial_promo)126 (#litres_trial_promo)127 (#litres_trial_promo)128 (#litres_trial_promo)129 (#litres_trial_promo)130 (#litres_trial_promo)131 (#litres_trial_promo)132 (#litres_trial_promo)133 (#litres_trial_promo)134 (#litres_trial_promo)135 (#litres_trial_promo)136 (#litres_trial_promo)137 (#litres_trial_promo)138 (#litres_trial_promo)139 (#litres_trial_promo)140 (#litres_trial_promo)141 (#litres_trial_promo)142 (#litres_trial_promo)143 (#litres_trial_promo)144 (#litres_trial_promo)145 (#litres_trial_promo)146 (#litres_trial_promo)147 (#litres_trial_promo)148 (#litres_trial_promo)149 (#litres_trial_promo)150 (#litres_trial_promo)151 (#litres_trial_promo)152 (#litres_trial_promo)153 (#litres_trial_promo)154 (#litres_trial_promo)155 (#litres_trial_promo)156 (#litres_trial_promo)157 (#litres_trial_promo)159 (#litres_trial_promo)160 (#litres_trial_promo)161 (#litres_trial_promo)162 (#litres_trial_promo)163 (#litres_trial_promo)164 (#litres_trial_promo)165 (#litres_trial_promo)166 (#litres_trial_promo)167 (#litres_trial_promo)168 (#litres_trial_promo)169 (#litres_trial_promo)170 (#litres_trial_promo)171 (#litres_trial_promo)172 (#litres_trial_promo)173 (#litres_trial_promo)174 (#litres_trial_promo)175 (#litres_trial_promo)176 (#litres_trial_promo)177 (#litres_trial_promo)178 (#litres_trial_promo)179 (#litres_trial_promo)180 (#litres_trial_promo)181 (#litres_trial_promo)182 (#litres_trial_promo)183 (#litres_trial_promo)184 (#litres_trial_promo)185 (#litres_trial_promo)186 (#litres_trial_promo)187 (#litres_trial_promo)188 (#litres_trial_promo)189 (#litres_trial_promo)190 (#litres_trial_promo)191 (#litres_trial_promo)192 (#litres_trial_promo)193 (#litres_trial_promo)194 (#litres_trial_promo)195 (#litres_trial_promo)196 (#litres_trial_promo)197 (#litres_trial_promo)198 (#litres_trial_promo)199 (#litres_trial_promo)200 (#litres_trial_promo)201 (#litres_trial_promo)202 (#litres_trial_promo)203 (#litres_trial_promo)204 (#litres_trial_promo)205 (#litres_trial_promo)206 (#litres_trial_promo)207 (#litres_trial_promo)208 (#litres_trial_promo)209 (#litres_trial_promo)210 (#litres_trial_promo)211 (#litres_trial_promo)212 (#litres_trial_promo)213 (#litres_trial_promo)214 (#litres_trial_promo)215 (#litres_trial_promo)216 (#litres_trial_promo)217 (#litres_trial_promo)218 (#litres_trial_promo)219 (#litres_trial_promo)220 (#litres_trial_promo)221 (#litres_trial_promo)223 (#litres_trial_promo)224 (#litres_trial_promo)225 (#litres_trial_promo)226 (#litres_trial_promo)227 (#litres_trial_promo)228 (#litres_trial_promo)229 (#litres_trial_promo)230 (#litres_trial_promo)231 (#litres_trial_promo)232 (#litres_trial_promo)233 (#litres_trial_promo)234 (#litres_trial_promo)235 (#litres_trial_promo)236 (#litres_trial_promo)237 (#litres_trial_promo)238 (#litres_trial_promo)239 (#litres_trial_promo)240 (#litres_trial_promo)241 (#litres_trial_promo)242 (#litres_trial_promo)243 (#litres_trial_promo)244 (#litres_trial_promo)245 (#litres_trial_promo)246 (#litres_trial_promo)247 (#litres_trial_promo)248 (#litres_trial_promo)249 (#litres_trial_promo)250 (#litres_trial_promo)251 (#litres_trial_promo)253 (#litres_trial_promo)254 (#litres_trial_promo)255 (#litres_trial_promo)256 (#litres_trial_promo)257 (#litres_trial_promo)258 (#litres_trial_promo)259 (#litres_trial_promo)260 (#litres_trial_promo)261 (#litres_trial_promo)263 (#litres_trial_promo)264 (#litres_trial_promo)265 (#litres_trial_promo)266 (#litres_trial_promo)267 (#litres_trial_promo)268 (#litres_trial_promo)269 (#litres_trial_promo)270 (#litres_trial_promo)271 (#litres_trial_promo)272 (#litres_trial_promo)273 (#litres_trial_promo)274 (#litres_trial_promo)

Praise for Bernie Marsden (#u8d7235fb-a75f-5c2f-9ea5-df51b3810459)

Pat Cash, tennis champion

‘There wouldn’t be many guitar fans who haven’t heard a Bernie Marsden riff somewhere along the road. That goes for anyone alive in the ’80s and early ’90s, guitar fan or not. My first awareness of Bernie was during the glory years of Whitesnake while I was travelling the world making a career in tennis. Great album after great album, catchy riffs with melodic yet rocking solos. It was post-Whitesnake that I discovered the Marsden voice in its full extent, his most recent blues albums showing those talents. As a Rory Gallagher fan his Bernie Plays Rory album was more than a worthy tribute – a pure joy. No wonder he is applauded throughout the blues and rock world as one of the iconic musicians of his generation.’

Dónal Gallagher, brother of Rory

‘Rory’s admiration for Bernie as both a musician and as a person was huge and I share my late brother’s sentiments. Actions speak louder than words – Bernie was the first guitarist allowed to perform with Rory’s Stratocaster after his passing. In addition to his own great abilities, Bernie carries the torch!’

Steve Lukather, Toto

‘Bernie is part of the legendary wave of British blues-rock players I heard that had it all. His soul, chops and sound resonated with me. He is also a first-class gentleman and when he came to meet me and see me the first time Toto played in London in the very early ’80s he brought Jeff Beck and Gary Moore. Like I wasn’t intimidated enough by him … ha, ha! This started a lifelong friendship. Bernie is one of the best in every way and I am honoured to call him my friend – and he is one badass guitar player!’

Ian Paice, Deep Purple

‘Bernie is one of those rare musicians who can play whatever is required of him. Rock, blues, pop, you name it and he will do it, and do it very well! A talent in itself. But the other string to his bow is his writing. Back in the Whitesnake days it was obvious that without those songs, the band would have found it much harder to break through and enjoy the success it achieved. Those songs started out from Bernie’s imagination. No Bernie – no songs.’

Paul Jones, musician and broadcaster

‘I think the first time I played with Bernie was when he sat in with the Blues Band at a gig in Swindon, and I thought, Wow – this heavy metal guy can really play the blues! As time went on, I discovered that the blues (and soul) have informed all his work. The other thing I admire about Bernie is his humility. I’ve seen it on many occasions – not least the times when he’s contributed to my charity gigs at Cranleigh Arts Centre.’

Warren Haynes, the Allman Brothers Band

‘I first met Bernie in 1991 when the Allman Brothers came to Europe. There was a benefit at the Hard Rock in London and a bunch of us went and wound up jamming. I heard Bernie play and not only did he play great but he had the best sounding rig of anyone on stage. When it came time for us to play I asked him if I could play through his gear, saying something like, “You’ve got the only good-sounding rig on stage.” He laughed and obliged. We became instant friends and have played together numerous times since. I really love his economy of notes and the fact that the most important thing to him is to get a good sound first (which he seems to be able to do with any setup) and then take it from there.’

Zak Starkey, The Who

‘If I had never met Bernie Marsden I would never have spent three years sitting on his garden furniture in the back of a transit crying with laughter and playing the real blues all over the UK, Europe, Northampton and JBs Dudley.

There is Whitesnake, yes, but let’s not forget Bernie’s great pop sensibility in his work with Mickie Most in the ’70s. Bernie is a dear friend for life who never actually paid me but taught me so much about playing with empathy, sincerity, emotion, and fucking huge balls that I owe him at least forty quid.

We bonded over Freddie King, who I was lucky enough to see play once. Bernie has Freddie King’s shoes and he’s getting ready to dust his broom in the palace of the king. A perfect hideaway to stumble into while steppin’ out, walkin’ by himself and … sorry I digress as usual – here I go again.’

Elkie Brooks, singer

‘Having always been a huge fan of blues music and its various transitions throughout the years, there is nothing better than to hear it played with style and integrity. Bernie Marsden has both in abundance.

We did not work together until 2002 when I was appearing at the Maryport Blues Festival, Cumbria. Bernie was on the bill with his own band that night and I asked him if he would like to get up and do a few numbers with my band later. It was a special night and the atmosphere in the marquee was electric. Bernie added his own dynamic to our sound and it was a great gig. A few years later I called up Bernie and asked if he would possibly come on the road with us for a few months … so off we went! He was such a marvellous addition and a real pleasure to play with.

Among the stunning array of songs Bernie has written, I really fell in love with “A Place in my Heart”. A real testament to a true talent.’

Bob Harris, broadcaster

‘We first met in 1970, just before I joined Radio 1. I was a DJ at the Country Club, a very cool north London rock venue where Bernie appeared with Skinny Cat. Even now I can remember Bernie’s playing – “just like a ringing a bell”, as Chuck Berry would say. He was a fabulously expressive, economical guitarist. At a time when speed seemed to be of the essence, Bernie’s style was relatively understated but beautifully constructed, already demonstrating his intuitive knowledge of what spaces to fill and how much space to leave. It’s a rare gift.

Since then, as we know, he has enjoyed massive success as a player, writer, Hollywood film score composer and a member of one of the biggest bands in the world but despite all the head-turning fame, he has always kept his feet on the ground.

Recently, Bernie joined me in my home studio to play an acoustic session for my TeamRock show, Bob Harris Rocks, a full-circle moment. He has deep respect for and amazing knowledge of the players who helped influence his style and who laid the foundations of so much of the music we’ve loved and supported these past forty-six years.

It feels good to have known Bernie all this time and to have shared many great moments. They all really mean a lot. I have massive respect for him as a superb musician but even more than that, I cherish him as a friend.’

Jack Bruce, Cream

‘When I saw Bernie leaving Abbey Road Studios as I arrived, I said to him, “Turn around, man, you’re playing on my new album!” This was the best move I ever made. Bernie’s delicacy of touch hides the great power of his playing. He has that amazing quality of making every note sound like the only possible note that could be played – and that’s before you consider the depth of his sound. He is simply fantastic.’

BB King

Email from Juergen Hoelzle of FRS Radio Stuttgart: ‘In 1996 I had the pleasure of interviewing BB King for my radio show. We talked of many things, I don’t need to give you a breakdown. Well, except one thing, which it has occurred to me that you might not be even aware of. Near the end I asked, “Can white men feel and sing the blues?”

His answer surprised more than a few people and the room was buzzing when he said, “Most of them don’t ’cos they do not have the soul for it, sure they can play the blues, but that’s not the point. You have to feel the blues, you must go deep into the blues, open your mind and soul. In my opinion there are only a handful of white musicians in the world who can play the Blues like they should be played: Eric Clapton, Jeff Beck, Peter Green, Jonny Lang, John Mayall, and don’t forget that Whitesnake guy, Bernie Marsden, he got it too. It is not because of their technique, it’s also not their bluesy voices, it’s just simple, they have the blues and that’s it.’

Introduction (#u8d7235fb-a75f-5c2f-9ea5-df51b3810459)

I first met Bernie Marsden in Musicland Studios in Munich when Paice Ashton Lord (PAL) had come to town to make their debut album, Malice in Wonderland. I’d popped in to say hello. Bernie was the singer and guitarist with PAL. I found him welcoming, charming and personable. Who could have known that within a few years we’d be making Whitesnake a band to be reckoned with worldwide?

The second time I saw him was in London. PAL had folded and Bernie quite boldly suggested himself for the band I was putting together after Deep Purple. He immediately established himself by playing and singing great, and bringing his excellent sense of derisive humour to the mix, which was a huge part of early Whitesnake.

Bernie, Micky and I wrote the songs that created Whitesnake’s sonic identity and helped to make the band a household name. The vocal blend of the three of us worked refreshingly well and our choruses inspired the creation of the Almighty Whitesnake Choir – ah, sweet memories.

Bernie was truly an invaluable band-mate, friend, musician and co-composer of many of my favourite Whitesnake songs, particularly ‘Walking in the Shadow of the Blues’ and ‘Here I Go Again’, probably our most recognised and successful song. It has served us and continues to serve us very well, hasn’t it, ol’ son?

’Tis a biggie, for sure …

I am so happy we are back in each other’s good books and get to jam together whenever I have the pleasure of performing in our home country.

Happy trails, ol’ chap.

David Coverdale, Lake Tahoe, 2019

Preface (#u8d7235fb-a75f-5c2f-9ea5-df51b3810459)

Over nearly fifty years on the road as a professional musician in different cities, countries and continents, I have often thought about Brian Davies.

Brian was a couple of years above me at secondary school in the Sixties in Buckingham, my home town just north-west of London. He was always friendly to me and was an all-round good guy. I remember him being a particularly good athlete: good at running, long jump and javelin. His girlfriend at the time was Diane Jones, someone who I secretly worshipped from my lowly position in the younger classes. I played football with him at school and later for Buckingham Town Juniors. I was a decent enough player but I always thought that he was a very good footballer.

As far as I could see, Brian Davies had it all. We got along well without being close friends. He left school two years before I did, but we still saw each other at football games and sometimes at the pub when I might have been playing the guitar. My playing had always fascinated Brian.

The last time I saw Brian was in 1970 at the corner of Buckingham’s West Street and School Lane, where we had a short chat. He said he was no longer with Diane Jones and that he hadn’t been able to play football much of late. I told him that I still wanted to be a professional musician; Brian and I had often talked about our dreams. I thought he looked a little grey. Under his arm he carried an old-fashioned glass medicine bottle full of a lurid green liquid. I told him not to drink too much of it: whatever was inside looked as though it might kill him. I could not have been more wrong about that – he had actually been prescribed it to treat a cancer, Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Brian passed away later that same year. I was deeply shocked. He was so young, just 21, and I was only 19. Brian had always encouraged me to be a professional musician. He championed my ability and said that I shouldn’t ever give up. I still think about Brian Davies a lot.

At every milestone I have reached, a little piece of Brian has been there with me. Whether it was stepping off the plane for the first time in Japan, getting the phone call to say ‘Here I Go Again’ had reached US No. 1, or receiving my honorary degree from the University of Buckingham, I’ve always thought of him.

1.

New York, New York, 1980 (#u8d7235fb-a75f-5c2f-9ea5-df51b3810459)

On 9 October 1980, the Whitesnake tour bus driver drove over the Brooklyn Bridge and into Manhattan. My mind was racing and I was full of excitement although I tried to appear cool. At last I was in New York City.

David Coverdale walked up the bus, smiling, and shook my hand. He knew what it meant to me. He had been the one to shake my hand the first time I landed in the USA, in San Francisco. He had felt the same the first time he came here, with Deep Purple. I stared at the skyscrapers. It seemed as though there were so many. I couldn’t wait to see Times Square, the Brill Building, Radio City, and Carnegie Hall.

My thoughts drifted to the shows I had done at school concerts, carnivals, wedding receptions, pubs and birthday parties, and in village halls. I felt a huge sense of nostalgia. I looked around the bus, taking in the musicians I was playing with: Jon Lord, Ian Paice, Neil Murray, Micky Moody, and David Coverdale, all now in the same band as me.

Madison Square Garden – here I come.

This had been a huge goal for me since my teenage years, when I listened to live boxing on my portable radio from MSG. I explored the venue by myself when we arrived. I felt like a kid. I wanted to find those boxing dressing rooms and be able to stand in the very spots Joe Louis, Rocky Marciano, Joe Frazier, Muhammad Ali and the Raging Bull himself, Jake La Motta, prepared for the biggest fights of their lives. Marilyn Monroe sang ‘Happy Birthday’ to JFK here, and the likes of the Jackson 5, Stevie Wonder and Alice Cooper had performed there.

Whitesnake would open for Jethro Tull that night in front of some 15,000 people as part of our US tour. I had been frustrated many times in previous years by tours in the US being cancelled for various reasons but now all of that was unimportant. It had taken less than eight years to go from my local town hall to Madison Square Garden. No time at all really.

We stayed at the famous Navarro Hotel, a magnificent gothic building overlooking Central Park. Its residents included film stars, poets, musicians, singers and artists and Jacqueline Susann wrote Valley of the Dolls there in the 1940s. Musical guests included Jimi Hendrix, the Kinks, the Rolling Stones, the Grateful Dead and Jim Morrison. I shared an elevator with actor James Caan when I arrived. Sonny Corleone and me in a lift! I tried to be the cool Englishman as Mr Caan smiled, ‘Nice socks.’ I had completely forgotten that I was holding a spare pair lent by Mick Moody. ‘Take care with those socks,’ said James Caan as he got out.

Whitesnake had no creative management whatsoever but had managed to get to America. That was testament to how together we were at the time. We were ready and it was our time to go global. I was back on the bus and heading for Madison Square Garden in no time. The gig was over far too fast. Jethro Tull’s audience liked us a lot, although we were practically unknown in America. Jon Lord and Ian Paice received the biggest recognition as Deep Purple still meant something to the fans.

Time to break America – that was the plan. But plans don’t always work out, do they? Let’s go back to the start.

2.

Going to my Home Town (#litres_trial_promo)

I was born on 7 May 1951 in Westfields estate in Buckingham, an extremely quiet town of between 2,000–3,000 souls. My mum and dad were working-class parents and, boy, did they work hard. When I was four we moved to a brand-new council house in Overn Avenue. This was a triumph – my parents had earned their new house, and they loved it. It was my castle.

Buckingham had old-fashioned shops, rather than supermarkets – butchers, greengrocers, a wool shop, a saddler, two gentlemen’s outfitters and a very good toyshop. Walter Tyrell, the fruit-and-vegetable man, delivered to our estate twice a week, his overloaded cart drawn by one of his small ponies. Brook’s Dairies delivered milk and orange juice daily, also by horsepower.

My Victorian-built primary school was in Well Street. I got on well with the teachers, except deputy head W. T. Benson. I don’t know why he took such a dislike to me. When I was seven he ridiculed me in front of the class for a spelling mistake. All he did was make me realise that I rather enjoyed being the centre of attention – a sign of things to come!

I failed my eleven-plus and went to the secondary modern. I never did go to university, but in 2015 the University of Buckingham honoured me with a master’s degree for services to music and Buckingham! I accepted with a great deal of pride. My dad was there with my wife, Fran, and daughters Charlotte and Olivia. I wish that my mum could have seen it, but she passed away the previous year. I did find it ironic to be mingling with brilliant academics who had years of hard study under their belts when I had received only a very average education myself. Some of my teachers had also taught my mother some thirty years earlier. Imagine that! How could they possibly relate to my generation?

I was twelve when President Kennedy was shot in November 1963. I remember being scared by my mum’s reaction. ‘There will definitely be a war if the Russians did it.’ I went to the pictures that night, but I couldn’t take my mind off JFK and impending doom. I had butterflies in my stomach the whole time. Young people in that cold war period lived in constant fear of the Russians and another world war. But the USSR was innocent, this time, and therefore not going to bomb us off the planet.

Beatles records had started hitting the charts that year – they cheered America up, and they cheered the world up. In my head, it was the Beatles who beat the Russians – I was convinced of that fact. They also ended the reign of the artists I had grown up with in my household – middle-of-the-road stars like Joe Loss, Jess Conrad, David Whitfield, Pearl Carr and Teddy Johnson and Perry Como. Meanwhile, Lonnie Donegan, Joe Brown, Cliff Richard and the Shadows survived and managed to stay with the new army. I had become a fan of a few of them: Joe Brown, Cliff Richard and Marty Wilde. They seemed splendid. Their shiny guitars fascinated me. I watched them on Ready Steady Go!, Juke Box Jury, and Thank Your Lucky Stars.

My cousin Sylvia Chalmers was a huge fan of Elvis, but she was older than me. Merseybeat was the happening thing and all I could think about was guitars. But now came the hard bit for an almost-teen. Just how do I learn to play the guitar?

There were no musicians in either side of my family. The first person I ever saw playing the guitar in the flesh was Roger Williamson from Northampton. He played ‘Apache’ by the Shadows at my cousin Jean’s wedding reception in 1961 and I think he had a gleaming red Fender Stratocaster. I didn’t really know how to judge but I thought he played really well. He played ‘Shakin’ All Over’ by Johnny Kidd and the Pirates, a seminal song with the guitar riff of the period. Guitarists today still rate it. London session guitarist Joe Moretti plays those brilliant parts on a white Fender Telecaster.

I was fortunate at a ridiculously young age to have seen acts at Buckingham Town Hall and in the surrounding towns. There was always the potential for danger, with fights breaking out during sets, but I used to sneak in the back of the town hall and climb into an old lighting box to watch the bands on Friday nights, usually fibbing to my folks that I was visiting my grandparents. I saw Screaming Lord Sutch and the Savages – at a time when there was with the real possibility that Ritchie Blackmore was playing guitar – Joe Brown and the Bruvvers, maybe Neil Christian and the Crusaders with Jimmy Page on guitar, Freddy ‘Fingers’ Lee, Mike Sarne and Bert Weedon. I was bitten by the excitement, alone up there, with the hall full to bursting.

I was in Steeple Claydon hall one Saturday night in 1964 to see the Primitives, and I thought they were fabulous. I got as close to the stage as I could. I had never seen men with such long hair – I was more than impressed. They made two singles for Pye Records and Jimmy Page played on both of them, I’m told. They came from Oxford but their home could have been Jupiter as far as I was concerned. I had seen them on the TV, and now I was a few feet away from them. I was captivated.

I used to see a guitarist from nearby Winslow when I was 14. Nipper – his real name was Gerald Rogers – had quite a reputation and often played weddings. His group was the Originals – Les Castle, Snowy Jeffs, Nipper and either Keith Fenables or Maurice Cracknell singing. Nipper played guitar. One night at the Verney Arms I heard them do Muddy Waters’s ‘Hoochie Coochie Man’. It was a revelation to hear local guys play this, and play it well.

My cousin Keith Aston had somehow got a guitar but I was under strict instructions not to touch it. I did, of course. I found it a hugely pleasurable experience, just holding it and touching the neck. I didn’t really understand the feeling, it just felt right. I had to have my very own guitar and I bugged my folks until they caved in. Finally I had a very old and very used acoustic Spanish guitar. It wasn’t particularly good, I knew that even then, cheap and hard to play, especially for a beginner. It was almost impossible to hold one or two notes down, let alone a chord. I persevered until my fingers bled, skin coming off the tips. My hand ached beyond description and became such a painful claw that Mum asked me why my fingers were such a mess. She was genuinely concerned. I practised every single day for months on end and, gradually, the pain subsided, although the worn-out instrument remained extremely difficult to play. This was how I learnt my craft, and what a miracle that I, and countless others all over the country, were prepared to go through this pain barrier.

I astonished my folks one evening when I was able to play along with the theme tunes from Coronation Street and Dixon of Dock Green. They were both very enthusiastic but I told them that, even though I had improved, the guitar was holding me back. I thought my heavy hint was a bit of a long shot but to my delight they agreed. Thank you, TV theme writers!

I saved every penny from my paper round, and had been saving all my birthday and Christmas money for a couple of years. I had enough money for a deposit! Dad said he would help me out as much as he could. ‘How do we get an electric guitar?’ he said. I knew exactly where. I had been there before.

3.

Look Through Any Window (#litres_trial_promo)

When I was 13 I spent a few days in at my aunt Doreen’s house in Hampstead, London. I was allowed to make a bus trip on my own after promising I would see the town but not get off the bus.

I boarded the no. 24 from Hampstead to Pimlico, a round trip of about three hours. It remains a great way to see central London. I sat in the prime seat – front, upstairs – and went to Camden Town, Marylebone Road, Gower Street, Trafalgar Square into Whitehall. Sitting there all alone I saw Nelson’s Column, the Houses of Parliament, Big Ben, Westminster Abbey and more, all sights I had only seen in pictures or TV. It was very exciting.

On the return leg I glanced up at 114 Charing Cross Road, the Selmer Music Store – the UK’s sole importer of American guitars. It was a life-changing moment. I had promised not to leave the bus, but what could I do? I had seen Selmer’s window, full of Fender, Gibson, and Epiphone guitars. It was fate. If I had been sitting on the left-hand side of that bus, I would never have noticed. I was down those bus stairs and off the footplate without thinking.

There were bass guitars, amplifiers, and custom-coloured Strats that I’d only ever seen in catalogues. The archtop Gibsons in the store were almost two hundred pounds, an unreal amount of money. One side of the store stocked brass instruments with the famous Selmer badge on them, all very well but of no interest to me, really, the guitars had me totally spellbound. Selmer’s was a magic kingdom. The Beatles had been in this very store, as had the Hollies and the Applejacks.

I spent over two hours in the shop but it took me an hour before I actually plucked up the courage to touch one. The assistants were very nice and I took a Fender Stratocaster down from the wall and dared to ask how much it was. The answer was 140 guineas, the equivalent of around £165. This was an incredible amount of money. That very same model today would be worth £30,000 or more.

It eventually dawned that my aunt and uncle would be wondering where the hell I was as I’d been gone for three hours longer than expected – oops. I apologised, told them where I had been and promised not to do it again.

The next day I was on the twenty-four again, this time getting off at Cambridge Circus. I walked up Charing Cross Road and to my delight I discovered many more guitar shops – Macari’s, Pan Music. I returned to Selmer’s where I heard a famous band were also browsing – could it be John, Paul, or George, or maybe Tony Hicks or Graham Nash? No, it was just the Bachelors, brothers Con and Dec Cluskey buying new Gibson acoustics. The Bachelors were one of my mum’s favourites.

It wasn’t until later visits that I met the Merseybeats, also Chris Curtis, the drummer with the Searchers. I had taken a guitar from the wall, totally out of my price range, of course, and was playing it quietly. Curtis said I was a very good player and invited me to his flat in Chelsea. I accepted his invitation – he was a pop star, after all, and had a chauffeur-driven car. I still don’t believe it, but I got in the car with a man I had just met. With hindsight, that could have been a terrible scenario.

He said that he would cook at the flat. Jon Lord later told me that he was probably elsewhere in the flat at the time – Jon was ten years older than me and was just then starting the project with Chris that would later become Deep Purple. As it turned out, there were only Cornflakes in Chelsea and so that was the meal. I did feel a little strange, eating cereal with Mr Curtis, and wondering why I was there. I should also say that Chris was very nice to me, and nothing whatsoever questionable happened. Maybe he had in mind that I could have been the guitarist for Roundabout, but I was only a young teenager. Jon would later pull my leg about that day, especially at breakfast in a hotel on the road where there were Cornflakes around.

I got to know Denmark Street’s shops well and when my dad asked me where we could get an electric guitar, I was ready. Dad was the guarantor for the hire purchase agreement. Selmer had a special offer on the Colorama 2 by the German company Hofner, whose guitars were very popular, reasonably priced and good quality. It was the one for me. The monthly repayments were quite high, but I really didn’t care: and I had my first electric guitar!

I held the green plastic case tightly as we went home. I thought the guitar was beautiful. It was finished in a cream colour, had twin pickups and a tremolo arm. I took it everywhere – my mum often said that I was chained to it. I couldn’t believe how much easier it was to play than my Spanish acoustic. There was just one more thing …

‘You never said anything about a bloody amplifier!’ said my dad.

I pleaded with him and we acquired a five-watt Dallas amp from Butler’s furniture shop in Buckingham. I practised daily and our next-door neighbour, Tom Tranter, who worked nights, soon had his own name for my setup. He called it ‘That bloody electric thing.’

I quickly improved at the guitar while my grades at school plummeted (although I did get a B-plus for music). The art teacher said in his year report, ‘I have never known such an idle and yet so charming boy.’ I rather liked that.

The first real group I was in was the Jokers: I must have been about 14. They were already an established act with Eric Jeffs on bass, Stan Church on drums, Dave Brock (not the future Hawkwind leader!) as the vocalist and second guitarist, and Steve Rooney the lead guitarist. Eric played bass guitar left-handed, à la McCartney – but strung normally and played upside down.

In the practice room at the youth club I immediately realised the underpowered Dallas was useless in this company. I knew I needed a bigger amp but I didn’t have any money, and asking Dad was out of the question. Guitarist Steve owned a six-input amplifier with a massive thirty watts of power which I used via Dave. Steve found me – a young upstart – playing all the guitar licks he knew plus quite a few that he didn’t and, worse still, playing them through his massive amp. Having both of us in the band was never going to work. The upstart 14-year-old was already shining brighter than Steve and he left the band – and took the big amp with him. Dave Brock had a lovely, blue Watkins Dominator amp which he lent me. I wish I still had it, a very collectable amplifier.

Steve later told me he left the band because he wanted to spend more time with his girlfriend. I was amazed. Even at 14, I couldn’t understand why anybody would want to spend time with a girl instead of being the guitarist in the Jokers.

I was very keen, practising all the time, learning Chuck Berry riffs and Bo Diddley songs, and I settled in very quickly. We had a major upset when drummer Stan Church left after a member of his family was jailed for the manslaughter of a local girl. The case even made national TV. I was very young and quite frankly confused. I didn’t understand why this had to have such an impact on my band – was having the name Church the reason?

Roger Hollis replaced Stan as our drummer. He lived near me in Overn Avenue, and was an early heavy metal drummer: he really did hit them hard. We practised every Tuesday and Thursday evening, when the sound of the judo lessons in the upper room was louder than the band. Amps were soon to become a lot louder – thank you, Jim Marshall.

We had another setback when there was a robbery and all of the Jokers’ equipment was stolen. The story made front page of the Buckingham Advertiser and they sent a photographer who asked us to look appropriately sad. I felt a bit of a fraud as the only equipment I owned was safely back at home: I would never, ever leave my guitar behind.

The Jokers ran out of steam and I came across the Originals, whose guitarist Nipper Rogers had been such an inspiration to me. On one Sunday afternoon I was playing acoustic guitar in the garden of the King’s Head. Originals’ singer Keith ‘Diver’ Fenables heard me playing, asked who I was, and then disappeared. He had gone to tell drummer Les Castle about this new kid playing the guitar. He casually asked me if I could play any of their songs and I said yes, I could.

‘Good,’ he smiled back at me. ‘Be here at seven tonight.’

It dawned on me that I had just signed myself up to a gig. Nipper Rogers’ job took him away from the area and the Originals couldn’t do any gigs – until this particular Sunday! I was petrified: not only had I only played their songs in my bedroom, but Nipper was streets ahead of me as a guitar player My mouth had said that I could do it and so now I would play in a pub packed with punters.

I arrived at the King’s Head at about six, very nervous, and a little panicked because I didn’t have an amplifier. Les Castle was setting up his drum kit and had a big smile.

‘Well, you are young, my boy,’ he said, pointing to Nipper’s Burns Orbit 3 amplifier. ‘Use that.’ Les, Keith and I played in a corner of the main bar without a bass player. I kept my head down to avoid making any eye contact with the audience. I was pleased not to hear any booing after the first few songs. Les Castle gave me another smile.

‘Fabulous, my boy, carry on like that!’

We played ‘I Can Tell’, ‘Shakin’ All Over’, ‘Green Green Grass of Home’, ‘Twist and Shout’, ‘Kansas City’, ‘Look Through Any Window’ and ‘Hoochie Coochie Man’. By this time Keith Fenables was also smiling.

Half an hour later it sank in – I was playing with the Originals. I dreaded to think how it sounded, but after a few songs I felt brave enough to glance at the crowd. They were looking happy and a little shell-shocked. Who the hell was this wonder kid? Where was Nipper, the one-and-only, local Hank Marvin? The audience got louder as the night went on, and everyone had a bloody good time. At the end of the night, Keith introduced me to the crowd: ‘Let’s hear it for the new kid on the cuh-tah, ladeez an’ genelmen!’

Keith was deliriously happy. Never again would Nipper Rogers dictate to the Originals: here was a readymade and impressionable new player they could call on, unencumbered by girlfriend or job. The position of my hero Nipper as the top dog was gone after one Sunday night in the King’s Head. I was the new kid in town. Nipper never once called me out for taking his gig. Not only that but he was the single influence among all the great guitarists who made me believe I could pick up a guitar. Thanks, Nipper.

The bonus that night was that I got paid! Thirty shillings, a pound note, a 10-bob note and a baguette sandwich to take home. I could sense things were about to change – this was a turning point for the very young BM. I was hired for the regular Sunday night Originals gigs and the Hofner Colorama paid for itself many times over. I practised hard, improving the guitar parts on the songs and gaining in confidence. All my earnings were put aside at home for a Fender Strat and amp, and my mum found the savings one afternoon. There must have been the best part of a hundred pounds, a hell of a wad for a teenager. She and Dad sat me down to ask where I’d got the money from. It was only fairly recently that my dad admitted they thought I might have been a robber. They never expected I was paid to play. My dad’s face lit up although dear old Mum seemed a little sceptical. I soon acquired my own Burns Orbit amplifier.

We played most weekends, mainly in pubs, working men’s clubs and at wedding receptions and I got my first taste of fame. I loved it. I became quite a draw at the King’s Head, a local guitar hero. People treated me slightly differently – most were positive, although a few were jealous and some were unable to accept that this young kid could play the guitar at all. Women who were years older than me loved to hang out with the band, regardless of their marital status. Some weekends I was invited to a female fan’s house for a drink. I got to know a lot of them and I must have been very different to their husbands who had to be at work the next morning, mainly because I had to be back at school.

By the time I was 15, I was in my room so much, playing guitar, that I had become a bit of a loner at school. I did have a few good mates: Richard Bernert, Steve Wheeler, Derek Knee and Mick Hodgkinson, but even then it was the common love of music that connected us. I’d often go to Richard’s and mime to the Small Faces’ first album he played at maximum volume in the living room. I was Steve Marriott, of course, and Richard was Kenney Jones knocking the crap out of a cake tin and cushions with a knife and fork.

Music also played a background role in a job I did with Derek and Richard. We worked for a local chicken farmer, feeding thousands of chickens, collecting eggs, and cleaning out the cages. It was pretty well-paid for the time. The henhouse was an inferno of squawking, but we had a very loud radio pumping out Radio Caroline or Radio London from an eight-inch Fane speaker. The first time I ever heard the Stones’ ‘Jumpin’ Jack Flash’ was on Radio Caroline. The opening line really grabbed my attention.

Pirate radio was so important. I got to hear fantastic records one after another, and maximum volume in the henhouse made them sound so much better. The radio reception was unpredictable: some days our area was good, but I was likely to lose the guitar solo just when I was ready to learn it!

I didn’t want to leave school at 15, so I stayed for another year, not knowing what I wanted to do in terms of a ‘proper’ job. The only clear path I had in my mind was something involving guitar. And, boy, was I playing a lot of it by the time I reached my final year …

At the start of the year there was mass excitement because of the arrival of a new 22-year-old French teacher, Elizabeth Rees. She was a great-looking girl, about five foot three, long, black hair, glasses on the end of her nose, short skirt and high-heeled shoes. I think she could tell she was near enough every schoolboy’s fantasy. She stopped me in the corridor to ask why I had opted to take history instead of French. As she smiled at me I asked myself the same question. She said that she would make sure I worked hard and I went to the school office and promptly dumped history. I never did learn much French, but she did teach me one hell of a lot about life.

Elizabeth had heard me playing with the Originals and said she was astonished by my playing and I would be famous one day. This was a revelation – she was the only forward-thinker in the school, heading for the Seventies with the same attitude as all the kids who were stumbling towards that decade of change.

Despite my passion for the guitar, music had never been a favourite lesson. I didn’t know or care what a stave was – tiny black squiggles on five straight lines did not seem like music – but I enjoyed the playing side. I remember one lesson I was playing to some girls when music teacher Mrs Gwen Clark arrived. I put the guitar down.

‘Don’t put that thing away just yet,’ she said with a hint of sarcasm. She passed me a handwritten sheet music. ‘So, can you play that?’

I looked at the paper – black squiggles on a stave. I couldn’t decipher it. She was making a point about my sight-reading ability.

‘Now listen and learn,’ she said. She played the first notes on the piano. I recognised the tune, the theme from Z Cars on TV. The girls in my class looked on. I picked up the guitar and played the Z Cars melody almost instantly, Mrs Clark was looking a little vexed. I then played the guitar intro to Chuck Berry’s ‘Johnny B. Goode’.

‘So, can you play that?’ I asked her. There were more than a few giggles. Mrs Clark was furious and, to contain her embarrassment, she left the room. I laughed, but she should have taken pleasure in seeing one of her own students playing this way, as an untrained natural. I am still irritated by the way that people with obvious talents were disregarded. If I had listened to my teachers I would never have left Buckingham, and never have tried to make it as a guitarist. It makes me wonder how many potential writers, musicians and artists there were in those dingy, soulless schoolrooms during the Sixties who were ridiculed for having such dreams.

I needed a practical music education. Enter my cousin John Keeley, three years older than me, who visited from Liverpool. He sang and played harmonica in a band, which impressed me a lot. I told him that I could play the guitar, which didn’t impress him, but he did listen to me playing along with recordings by Gerry and the Pacemakers and the Searchers, before instructing me to throw the records away. He told me to get LPs by Howling Wolf, Sonny Boy Williamson, Muddy Waters and Buddy Guy – but I did refuse to give up the Beatles. John had seen Williamson at the Cavern with the Yardbirds, and allowed me to keep my live Yardbirds LP featuring the young Eric Clapton. The blues hit me like a hurricane.

I became obsessed with all things Eric Clapton. I even bought Tuf town shoes because I read he wore them – I read any Clapton magazine article and I paid close attention to his influences. I soaked them all up – I was a musical sponge. If Clapton mentioned a player in an interview, I went straight down to the local shop to order that record. Some were so obscure, some on American labels with strange names: Chess, Federal, Sue and Pye International with the red-and-yellow labels. Artists such as Freddy King, Otis Rush, T. Bone Walker, and more. I slowed down the records to 16 rpm on the radiogram, making it a little easier to learn the guitar parts.

It wasn’t always straightforward to find this music. A folk guitarist first suggested I should listen to BB King. The folk player had a really good fingerstyle and liked the way I played, saying it was a very different approach. I was lucky to get a UK Ember label 45-record by mail order of ‘Rock Me Baby’, BB King’s great song. When that Ember record arrived, that was really it. I later found King’s UK Stateside releases, the European versions of the early BluesWay/ABC. Live at the Regal is the one liked by most guitarists, but for me it was Blues is King. Both were recorded in Chicago in the mid-1960s with a small band, and BB is on great form vocally and his guitar playing still motivates and inspires me.

If asked today, I might most often say that the music of The Beatles was the source of my musical career. But, if I am really honest, the blues music went on to inspire and motivate me most of my life. I had already been aware of Big Bill Broonzy, his name fascinated me, but I never really knew what blues music was. But, once I had heard the Yardbirds and John Mayall I was looking for their source material. I searched for BB King, Leadbelly, Big Bill, Brownie McGhee and Sonny Terry, which led me to Freddy and Albert King. I was given a Louisiana Red album when I was about 14 called Low Down Back Porch Blues. I liked it a lot, although I didn’t really understand what it was about.

At around that same age, I saw Lightnin’ Hopkins, Sister Rosetta Tharpe and Muddy Waters on TV. I was mesmerised. There is some quite phenomenal footage from 1964 of Rosetta Tharpe tearing it up with a white Gibson SG Custom at a railway station platform in Cheshire. It sounds crazy but it is a fact. Try and find it! This was the music I wanted to play. I bought a 45 of Howlin’ Wolf, ‘Smokestack Lightning’, which featured a fantastic guitar player on B-side ‘Goin’ Down Slow’– this was Hubert Sumlin. Hubert played with both of the great Chicago blues players, Muddy Waters and Howlin’ Wolf.

I was soaking up all this music. Gone were all my records of UK artists, even The Beatles and The Hollies were at the back of the pack when it came to the bluesmen. ‘Boogie Chillen’ by Hooker fascinated me, and still does. The guitar part is so weird, but I loved it and tried to play it. I didn’t know about capos or tunings then, but I loved the sound. I found that I could reproduce some of Sonny Boy’s harmonica parts on the guitar. That inspired me a lot. Just a tiny fraction of this music was developing my own style and, even though I was fully aware that Eric Clapton and Peter Green had already got it down, I did persevere.

When Cream themselves played Aylesbury in February 1967 there was nothing that would stop me seeing them. My pal Alan Clarke and I hitchhiked to a venue which was heaving with the largest number of people I had ever seen in one space. And then Cream were there: Jack Bruce, Ginger Baker, and ‘God’ himself, Clapton. Their Marshall amps towered on the small stage, Eric playing his Gibson SG Standard and I heard the ‘woman tone’ in person. I watched in a kind of dream state as they opened with ‘N. S. U.’, and played ‘Sleepy Time Time’, ‘Sweet Wine’, ‘Born Under a Bad Sign’, ‘Cat’s Squirrel’, and a devastating ‘I’m So Glad’. They were magnificent.

I was jolted into the real world in a surprising way. I felt a sharp prod in my back, and turned around to see Elizabeth Rees, the new French teacher. She was in a very good mood, looking really good, and had a definite twinkle in her eye. She straight away said she would take us back to Buckingham after the show. She was with a friend, a nasty little piece of work named Drew, who taught history. How pissed off Drew must have been to take us back on his date. Alan and I were just grateful not to walk back the sixteen miles.

Outside Buckingham town hall I thanked Drew for the lift, he eyed me with some contempt, and I got out of the car. To my surprise – and Drew’s shock – Elizabeth also said ‘Thanks’ and ‘Goodnight’ to him. Man, he must have been livid. Alan walked back home while Liz invited me back for a coffee at her flat in Well Street, a minute’s walk away.

I was still filled with the excitement of the Cream gig, until it slowly dawned on me that I was alone with my French teacher in her flat. She was calm and chatty, and we discussed the show and our musical interests: all very grown-up stuff. Liz had liked that I played ‘Hoochie Coochie Man’ at the pub. She went to her bedroom and came back with an album to play on her Dansette record player. It was The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan. I had never bothered with acoustic music, unless played by black musicians. The only folk music I was aware of was by the likes of Wally Whyton and the King Brothers on the radio show Family Favourites. Bob Dylan was so radical. I was quite stunned.

‘Listen to his words,’ she said. I still listen to them today.

She told me I could be like my heroes and that if I practised, worked hard and, above all, dedicated myself to being a musician I could make it a career. She pointed that neither Bob Dylan nor Eric Clapton had ever seen the inside of a university, and that the old USA blues players that I worshipped were lucky to get any schooling at all. I really listened to her. Academically, I was way behind, but in learning about life I was taking a huge step forward.

I spent a lot of time at school with Liz Rees, and rumours were rampant, particularly as my French was not improving. Liz was a bohemian free spirit, just the person a young lad of fifteen years of age should stay away from. I was infatuated, of course: she did exactly as she pleased and didn’t give a damn about authority.

Something had to give and, halfway through my fifth year, it did. I was called for a meeting with headmaster Gerald Banks. I expected a loud barrage of abuse, but he was very cool and professional. Mr Banks was a good man, and I now see how he turned out to be more of an influence than I realised. Miss Rees was not mentioned by name, but we both knew what the talk was about. He was astute enough to realise and could see that I was a very grown-up fifteen-year-old. I knew what I wanted and I think he knew I would get it. I had no fears about the future, exam results were of no real interest to me and I certainly didn’t give a toss about other people’s perception of my relationships.

As the summer of 1967 approached it was obvious that my French exams were never going to happen. Liz even rang me at my home telling me to stay away from the oral examination, given that I couldn’t really speak a word of French.

There were rumours that Liz been asked to leave at the end of the year or that she might have been sacked. I think she would have resigned long before they could have fired her. I went to her flat to be greeted by a bloke of about 22. She introduced me to him, he was in a band from Birmingham called the Ugly’s. She had met him at a gig that weekend. Liz Rees was with a man, I was mortified, but didn’t really know why. Now I know, of course, that I was jealous. She was spending time with him and not me. She could sense my distress, smiled and put her arm around me. He made us all some coffee.

After a few days sulking, I went to see her again but her housemate Eileen Marner told me that she was gone for good. I must have looked terrible because Eileen was extra nice and told me I needed to get over her. Liz had been my guru and I as a young boy I was totally smitten. Her outlook on the importance of enjoying life and take-it-while-you-can attitude struck a chord deep within me. She said that I could do it. She was right, wasn’t she? Thanks, Liz, wherever you may be.

I did glimpse her briefly once more, years later. It was the early summer of 1974 and I was on my way to play with Wild Turkey at the Marquee Club. I waited for a tube, dressed in my four-inch, wooden-heeled platform boots – black-and-white stars and stripes all over the leather – orange-and-yellow loon pants with twelve-inch flared hems, a psychedelic tie-dye shirt, accessorised with long necklaces, rings and my hair long and very curly. I also had a long, off-white Afghan coat – well, it was 1974. I spotted an attractive woman in her thirties, reading a book. She smiled back at me and as the train pulled out, she mouthed, ‘Bernard?’ Liz! But she was gone, and I have never seen or heard anything of her since. I thought again about those long discussions we had – not for the last time.

After that brief summer of love, the guitar always came first. I was dumped by girls many times, but I never gave it a second thought. In any case, I struggled with girls my own age, having discovered older women. A lot of the venues the Originals played had female managers who would ask the guys to ‘send that young one that plays the guitar for the cash’. The band would giggle as I would often be met by a buxom, mid-thirties stunner in seamed stockings, black underwear and high heels. The rest of the Originals would be waiting for my reaction.

I vividly remember a lunchtime bowling alley gig in Bedford; the manager was a miserable old sod of about 40, but his more than attractive wife was the lady with the money. She was a wonderful tease, running her hands along her legs, smiling at me, saying how young I was to play so well, flattering me and watching my reaction. Giggling and flirting outrageously, she gave me a sexy look and put the two ten-pound notes in her very considerable cleavage. She added that if I could retrieve the cash without using my hands she would add another five-pound note. I played along, burying my head in her bosom and using my teeth to get the notes. I was young, naive and, of course, enjoyed the whole thing very much. She told me she was bored in Bedford since moving from London where she had been an exotic dancer, whatever that meant.

‘Check these out,’ she said. ‘I was a bit of a catch when I was younger.’

She passed me a few photos of her naked or wearing very little. I was shocked, really, holding full-frontal pics with the very lady in them standing next to me. Her husband arrived at that point. He grabbed the pics from my hands, threw them in the corner and told me to fuck off. She laughed and gave me a cheeky wave. I had the gig money though, safely in the back pocket of my Levi’s. The band asked whether I’d gotten the £25. The extra fiver had been a ruse.

4.

Welcome to the Real World (#litres_trial_promo)

I finally left school in 1967, without any qualifications, but also without any misgivings. I did feel a little sorry for myself though and found myself kicking my heels around the town. School done, Liz Rees gone – I supposed I’d have to go to work, then.

To my folks’ relief I found a job, at a ladies’ hairdressing salon in Bletchley, about ten miles from Buckingham. I commuted on my scooter, on which I had painted bright coloured flowers – 1967 was, after all, the year of the hippie and of having flowers in your hair (or painted on your Vespa). My treasured Hofner guitar was similarly adorned. What a sight I must have been, a long-haired kid zooming down the A421 Buckingham to Bletchley road every morning. I got a lot of stick for it but all I cared about was making enough money to buy a Fender Strat and eventually, in my dream of dreams, using that Strat to earn me enough money to buy a white MGA sports car.

The reality of my first proper job soon hit home. Adam of York was in Brooklands Road and the owner was a small bald man, certainly not Adam, but maybe he had come from York. His wife was a first-class battleaxe, a Margaret Thatcher lookalike who called her husband ‘Mr Derek’, and I disliked her from the start, though she was fascinating. She was prim, very self-assured and loudly northern, but affected a posh speaking voice, accented by her heavy Lancashire twang: ‘Madam’s ’air lewks loovly – very classy ’air,’ she would say. ‘That’ll be two-poun’ ten, please, lady.’

‘Mrs Derek’ seemed incredibly old but was probably only forty. She was a tyrant and treated all the staff like shit. She obviously believed that she owned people if she paid their wages. I heard ‘I pay the wages around ’ere!’ many times. I should thank the sad old bird, really, because she cemented my desire to be my own boss.

I washed around fifty heads a week. My hands were in and out of hot and cold water every day, sores and splits began to appear and they even bled. I applied tins of Atrixo cream, but the pain was still excruciating. The final straw for me came with Mrs Derek’s point-blank refusal to let me watch Chelsea and Spurs in the FA cup final of 1967. This was the only live football game of the year. I snuck out of the salon at three in the afternoon and watched a bit of it in a local TV shop, before moving next door, to the Jim Marshall music shop but my northern ogre knew where to find me.

‘Get back to work, you little sod!’ she screamed from the doorway, her face contorted.

I was making three pounds and a few shillings a week from this waste of time. It had been my folks who, understandably, thought I should have a real job. But I hated it so much. I returned to the salon one last time. ‘Just stick your job Mr Derek, and your awful wife. I’ve got a gig to go to,’ I said, feeling rather good about myself.

Mrs Derek was furious because she had wanted to sack me first. What a sight she was – eyes bulging, tongue out, spitting out words and looking at Mr Derek for support. He gave none. The older girls laughed, loving the fact that the old bag was getting it from the youngest and lowliest employee.

I walked out, never to return. My folks took it well but were keen to see me employed somewhere. It was not to be with the Originals. I had been feeling very stuck with them, sucked into music I didn’t really want to play. I was a lot younger and had younger ideas. Time to find another band but, as it turned out, they found me.

The Daystroms were the biggest local group in the area, even touring outside Buckingham with their own vehicle – a Ford Thames van. I’d heard a lot about them. They took their name from a Swedish company that produced home kits to make amplifiers. Mac Stevens was their bassist and Tony Saunders was on drums. Singer Dougie Eggleton called the shots and, most importantly, owned the van and PA system. Dougie had seen me with the Originals and decided I would be better off in the Daystroms. I didn’t argue – I wanted to be in the biggest group in the area.

Lead guitarist Alan Rogers was Nipper’s cousin. He was a cool guy; tall, slim and, I noticed, he had very long fingers. I thought this was essential for a guitarist – I looked at my own fingers and inwardly frowned. But even with longer fingers it became obvious in those early rehearsals that ‘the kid’ was already some way ahead of Alan as a lead guitarist.

The group practised in the drivers’ room at Buckingham’s milk factory. It was small, stank of smoke, and was not at all suited for the job but it was free and I loved it. I didn’t love the material much. Even at this very early stage I knew I couldn’t play ‘Silence is Golden’ by the Tremeloes for very long. I was still super-keen to be playing, though, and endeavoured to learn all the rhythm parts. I also knew most of the lead guitar parts, and Alan Rogers was very aware of this as he struggled to play them.

My first performance with the Daystroms was at Whitchurch youth club. Alan Rogers didn’t show up and Dougie Eggleton was panicking. ‘Bernard, you will have to play lead and rhythm guitar, I know you can do it.’

I knew that I could do it, too, and even if I was a little over-confident everything went well. Afterwards, in the dressing room, Dougie announced that I was to take over on lead. Nobody uttered a word in protest, and I breathed the rarefied air of the lead guitarist.

Over summer we changed our name to the more modern-sounding the Clockwork Mousetrap, and the Ford van became a kaleidoscope of colour. On stage we played ‘San Francisco’ by Scott McKenzie, ‘Massachusetts’ by the Bee Gees and still bloody ‘Silence is Golden’. Despite my reservations about the material, I played a lot of shows, including my first bookings at any distance. We travelled to Northampton, Bedford, Aylesbury and even into Cambridgeshire. It wasn’t exactly a world tour, but for a 16-year-old it was an amazing experience. I was at the annual Buckingham Carnival parade, playing with the band on the back of a lorry. We also played the town hall that night.

I built a musical reputation yet, to a fair few, I seemed like a ‘right little big ’ead’, with an ego. But I was simply growing in confidence because I knew I could play. Most of the criticism came from people who would so have loved to be able to play the guitar. Bitterness is a horrible trait.

We played just about every local village hall twice – or more. We also had more prestigious bookings, like the officers’ clubs of Upper Heyford and Croughton US air bases. The crowd reacted differently to UK audiences. Maybe seeing a band playing American songs reminded them of home, thousands of miles away, as did the drinks and homemade snacks that I had never heard of before: cold Budweiser beers, Hershey bars, and the infamous product of one Mr Jack Daniel. I looked forward to the interval, when I could listen to their great soul records, including Wilson Pickett, Eddie Floyd, Otis Redding, Aretha Franklin, James Brown, and Marvin Gaye. I was soon hooked on soul. After the break I’d have to get up and play ‘Silence is Golden’. I really wasn’t impressed.

One GI became a huge factor in my subsequent career. He was a black officer at Heyford and a guitarist, who had seen me struggling with a few parts. He approached me one Friday night during a break. He had a rich, southern accent, somewhere like Alabama. We had been playing our average versions of Stax material, probably ‘Soothe Me’ or ‘Hold On I’m Coming’ and he asked if he could play my guitar. He was good – very good. To my shame I only remember his first name, Bobby, but I’ve never forgotten his help.

He showed me the correct way to play the great rhythm guitar parts and brought his own Fender to the club. Between sets he taught me to play all sorts while the others were usually having a drink. Bobby explained in great detail where and how to shape chords and told me about fret positions. He kicked me into advanced playing by really emphasising the importance of rhythm guitar when I had previously been of the mind that lead guitar was of prime importance. Bobby spoke about ‘the feel’, over and over again. He told me that ‘the feel’ should be the very first and the very last thing I think about when learning a song. That tiny but monumental piece of advice stayed with me throughout my career.

We enjoyed our weekend partnership for some three months, during which time he even gave me records from Stax, Motown, Atlantic, and King and then he told me at one Friday night gig that he was leaving the air force and I was devastated. He had been the first real guitarist who actively nurtured my ability. He had turned me around and the advice he gave me formed the bedrock of the way I played from then on, the way I would write songs and, most of all, it ensured I would never do anything other than play the guitar for a living. He was a game-changer. He even joked that I would become famous one day because of his help. Well, what can I say? Thank you, Bobby. Wherever you may be.

I made a return to the Cream gig venue, but this time it was to be me on the stage. When the Clockwork Mousetrap played the Assembly Rooms in Aylesbury, I made sure that I stood as close to the spot where ‘God’ played and I went into my own zone. I still do that today at certain gigs – nothing really changes. On the stage in white paint in capital letters was a warning: ‘NO AMPLIFIERS IN FRONT OF THIS LINE’. I smiled to myself that night. I was sure that Clapton’s Marshall amps went well over that line.

About half an hour before the show Dougie had produced some grey, flared trousers and horrendous pink, polo-neck acrylic sweaters for each member of the band. I looked at him in disbelief and refused point-blank. The other members of the band began to get dressed and Dougie looked at me. What none of them understood was that I didn’t really care. If I wasn’t in that band I would surely be in another. I won the showdown, of course. What could he do? To fire me would mean cancelling the next few weeks’ gigs. My outfit stayed in its plastic bag although, with the others dutifully kitted out, the Clockwork Mousetrap looked like a very bad acid trip under the questionable stage lights. I would always have a problem with stage clothes. I have never really been interested in image, perhaps to my detriment but all I ever wanted was my next pair of Levi’s, a T-shirt or maybe a denim shirt and a leather Levi’s jacket. Rory Gallagher was always going to be my sartorial role model.

I was stonewalled by the band on the way home but the power of the lead guitarist had been established, and I used that little trick for some time, if not for long with the Clockwork Mousetrap. We parted company shortly after the ‘pink sweater affair’, but Dougie, Mac, Tony and, especially, Alan should be credited: they moved me forward a lot. I think they knew the time had come: I was on a totally different wavelength, with a whole new musical world emerging.

It was a guitar player from Seattle, America, who provided the real reason for me deciding to leave the band. I suspect Jimi Hendrix broke up many other bands as well. I saw the unknown guitarist on Top of the Pops performing ‘Hey Joe’. I had never seen anything like him – I suppose Presley accomplished the same thing for the previous generation. Jimi did outrageous things with the guitar, such as playing with his teeth. I was mesmerised – what a sound he created. No pink sweaters on this boy.

I knew I had to form a three-piece: guitar, bass and drums. Everyone I knew was reacting to the Jimi Hendrix Experience and Cream. I was getting tired of being ‘the kid’ and I wanted to be respected as a guitarist. This was a big dream for a 16-year-old from rural Buckingham. I formed the James Watt Compassion (I have no idea why I called it that), with Paul Sandman on bass and Charlie Hill on drums. We settled on tracks by the Bluesbreakers, Cream, and Hendrix, playing them exactly the same as the records – or so we thought. As the other two were both from Bletchley and none of us had a vehicle, we rehearsed over the phone, which was not great preparation for shows. We believed we were the business, but we were just about average, and it was the material that carried us through. We lasted less than six months but I knew it wasn’t working and the others agreed. At the final show Paul’s girlfriend chinned me for encouraging him to leave his previous band. Good girl.

The audience that night also included two members of the best young group in the area, the Hydra Bronx B Band from Brackley. They were there to offer me a new job, not knowing that I was just out of a band. Ian Dysyllas and Ray Knott said I could have the use of a Marshall 50 amp and speaker. A bribe, yes, and I took it with both hands. They even had their own rehearsal room at Ian’s house in nearby Turweston, packed with amps, guitars, microphones and a drum kit. They also had a coffee machine, which was all new to me.

They were more of a soul than a blues band and they did play some great stuff: ‘Hold On I’m Coming’ and ‘Soothe Me’ by Sam and Dave, ‘Sweet Soul Music’ by Arthur Conley and the brilliant ‘Soul Finger’ by Bar-Kays. The crowds loved their Motown.

Ian ‘Dizzy’ Dysyllas played drums and Ray Knott was on organ. Then there was Tom Kemp on bass, Ian Smart and Cyril Southam on saxophones and the dynamic Chris Adams on vocals. I replaced Graham Smart as guitarist. The band wondered if fans would still come out in force with the change but we won them over from the start. Ian and Ray could hardly stop smiling after the first show. We went back to Turweston and got pretty drunk on cheap Justina wine. For the first time I was playing the music I wanted to. The discipline in the band was very good for me, and Dizzy was organised in running rehearsals and making proper musical arrangements. It highlighted my rapidly improving playing.

The band slimmed down to Ray, Dizzy, Chris and me, playing proper rhythm and blues. There were more changes. I suggested to Ray, ‘Why don’t you play bass guitar? You are so rubbish on that organ.’ Tact has never been my strong point. We drove to London the following weekend and swapped the Vox organ for a vintage Fender Precision bass. Ray still plays bass today. Now going under the name the Skinny Cat Blues Band – I was a fan of Black Cat Bones with Paul Kossoff and Simon Kirke so I think that’s were the cat came in – we set about building on the Hydra Bronx crowd. I was really enjoying myself. The Daystroms had never had a musical direction, but Skinny Cat did.

I thrived on watching other talented people play. I always tried to emulate them even if I often failed. The Skinny Cat guys picked up on this almost immediately and I gained their respect. Guitarists who were years older than me started to come to Skinny Cat gigs, while we would open for other local bands and promptly steal all their fans. That is how it was in those days.

Banbury will always hold a place in my heart, as it was the first area away from home to adopt me, as a musician, openly taking to my talent. I had gone to a new blues club there and asked to play a song during the interval, as I thought I was better than the featured band’s guitarist. Unbelievably, they agreed and the player in question, Ron Prew, even had the decency to loan me his treasured Gretsch guitar. The promoter somewhat reluctantly introduced me, I sat on a stool with this alien guitar, and played Eric Clapton’s version of the Robert Johnson song ‘Rambling on My Mind’. The audience, players and fans alike, knew the track backwards. Most only dreamed of playing the solo, but I could – note for bluesy note. For good measure I threw in a couple of extra lead breaks of my own. I was rewarded with an edgy silence and so, wincing mentally, simply said, ‘Thank you for listening.’ The place erupted with applause. A few days later Skinny Cat was booked into the venue which more usually featured pro bands such as Chicken Shack, Jellybread, Duster Bennett, and the Aynsley Dunbar Retaliation. We were in good company.

We continued to play the venue with our following increasing all the time, although Chris Adams left the band as Ray, Ian, and myself were so tight. Yours truly became the singer, but then ‘Dizzy’ left to get married. The Skinny Cat line-up of eight was now down to bassist Ray Knott and me. Mick Bullard, the drummer with another local band, was given the job. He was used to learning songs from records but we were having none of that. Ray and I wanted to jam and find our own groove, to see where it would lead us. Mick agreed to join us even though we had no money coming in and he had to leave a band whose wages contributed toward his young family. The three of us cut the name down to just Skinny Cat to avoid being pigeonholed by the ‘Blues’ and in September 1969 I went into the studio, with the group, to record for the first time.