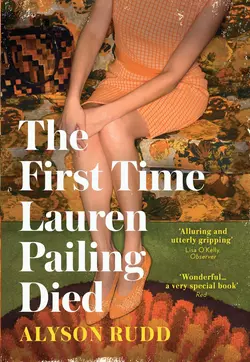

The First Time Lauren Pailing Died

Alyson Rudd

‘STYLISH, ALLURING, UTTERLY GRIPPING’ Observer ‘LIKE NOTHING YOU HAVE EVER READ BEFORE’ Red Lauren Pailing is born in the sixties, and a child of the seventies. She is thirteen years old the first time she dies. Lauren Pailing is a teenager in the eighties, becomes a Londoner in the nineties. And each time she dies, new lives begin for the people who loved her – while Lauren enters a brand new life, too. But in each of Lauren’s lives, a man called Peter Stanning disappears. And, in each of her lives, Lauren sets out to find him. And so it is that every ending is also a beginning. And so it is that, with each new beginning, Peter Stanning inches closer to finally being found… Perfect for fans of Kate Atkinson and Maggie O’Farrell, The First Time Lauren Pailing Died is a book about loss, grief – and how, despite it not always feeling that way, every ending marks the start of something new. ___________ Readers love The First Time Lauren Pailing Died: ‘I’ve never read anything quite like this book’‘A stunning novel that has really stayed with me’‘Loved this book from the first to the last page’‘A very enjoyable, original and moving story’ ‘An unusual and interesting concept’‘Would recommend to anyone that liked The Time Traveler’s Wife’

ALYSON RUDD was born in Liverpool, raised in West Lancashire and educated at the London School of Economics. She is a sports journalist at The Times and lives in south-west London. She has written two works of non-fiction. This is her first novel.

The First Time Lauren Pailing Died

Alyson Rudd

ONE PLACE. MANY STORIES

Copyright (#ulink_c2ef97f5-b65e-5a21-9969-1a56b9cd2add)

An imprint of HarperCollins Publishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

First published in Great Britain by HQ in 2019

Copyright © Alyson Rudd 2019

Alyson Rudd asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Ebook Edition © July 2019 ISBN: 9780008278298

Note to Readers (#u0c0bfb1f-e6a6-55ad-9cd3-adf876c68943)

This ebook contains the following accessibility features which, if supported by your device, can be accessed via your ereader/accessibility settings:

Change of font size and line height

Change of background and font colours

Change of font

Change justification

Text to speech

Page numbers taken from the following print edition: ISBN 9780008278281

Praise for The First Time Lauren Pailing Died (#ulink_994f6a98-f4c7-5b2a-b15a-826c30d7cc7c)

‘Stylish, alluring, utterly gripping. An intricate, elegantly written time-slip tale that keeps you guessing until the last page’

LISA O’KELLY, OBSERVER

‘A stylish time-slip story à la Sliding Doors’

GUARDIAN

‘This stunning novel gives you many stories for the price of one. In dealing with grief, love, and luck – and the unfair way they are distributed – it is both very moving and very clever’

MARK LAWSON

‘Beautiful, extremely moving and expertly done, with a lightness of touch that belies the complexity behind the plotting. I loved it (and I cried several times!)’

HARRIET TYCE

‘So many wonderful and unexpected moments … such a unique voice. A very special book’

SARRA MANNING, Red

For Sam and Conor

Contents

Cover (#ua74612bf-8da0-57e9-90c3-dc21108ddc9e)

About the Author (#ue352436f-d6c6-535e-808a-4065cb97e710)

Title Page (#ubc6246af-bdbc-52ff-b129-f06fee8bb34f)

Copyright (#ulink_447a28d4-946e-53a4-a759-772b224c2397)

Note to Readers

PRAISE (#ulink_8015b0c0-7486-5f51-924e-591acdd6f553)

Dedication (#u977a6063-108d-5d88-94b4-66556fd34730)

PART ONE

LAUREN (#ulink_35e5ddd8-3bad-51e8-810f-00e194e6993d)

PART TWO

LAUREN (#ulink_c0946c39-c3ef-5bbb-b4ef-4f73a5474655)

BOB (#ulink_c6dd6e08-05a9-5864-8b49-073641b25373)

VERA (#ulink_1bf70057-40a7-5431-adc4-352c93a2105e)

LAUREN (#ulink_0c1e767e-e4d0-5463-a02a-5d667f565e21)

BOB (#ulink_f2b72034-e52b-5ef9-b6af-a86bc8c9b5b3)

LAUREN (#ulink_cf1fe2cf-653a-5e69-b72d-79ee421980c5)

VERA (#litres_trial_promo)

BOB (#litres_trial_promo)

LAUREN (#litres_trial_promo)

BOB (#litres_trial_promo)

LAUREN (#litres_trial_promo)

BOB (#litres_trial_promo)

LAUREN (#litres_trial_promo)

BOB (#litres_trial_promo)

VERA (#litres_trial_promo)

LAUREN (#litres_trial_promo)

BOB (#litres_trial_promo)

LAUREN (#litres_trial_promo)

BOB (#litres_trial_promo)

VERA (#litres_trial_promo)

BOB (#litres_trial_promo)

LAUREN (#litres_trial_promo)

BOB (#litres_trial_promo)

VERA (#litres_trial_promo)

LAUREN (#litres_trial_promo)

BOB (#litres_trial_promo)

LAUREN (#litres_trial_promo)

BOB (#litres_trial_promo)

VERA (#litres_trial_promo)

LAUREN (#litres_trial_promo)

BOB (#litres_trial_promo)

LAUREN (#litres_trial_promo)

BOB (#litres_trial_promo)

PART THREE

LAUREN (#litres_trial_promo)

TIM (#litres_trial_promo)

LAUREN (#litres_trial_promo)

BOB (#litres_trial_promo)

LAUREN (#litres_trial_promo)

TIM (#litres_trial_promo)

LAUREN (#litres_trial_promo)

TIM (#litres_trial_promo)

BOB (#litres_trial_promo)

VERA (#litres_trial_promo)

LAUREN (#litres_trial_promo)

VERA (#litres_trial_promo)

LAUREN (#litres_trial_promo)

TIM (#litres_trial_promo)

LAUREN (#litres_trial_promo)

VERA (#litres_trial_promo)

TIM (#litres_trial_promo)

LAUREN (#litres_trial_promo)

TIM (#litres_trial_promo)

LAUREN (#litres_trial_promo)

BOB (#litres_trial_promo)

TIM (#litres_trial_promo)

PETER (#litres_trial_promo)

TIM (#litres_trial_promo)

PETER (#litres_trial_promo)

Acknowledgements (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

Part One (#ulink_8111275f-dabf-5f4a-9977-b8651187c860)

Lauren (#ulink_255a9a07-542c-51c4-b851-7b2da8949fcf)

Lauren Pailing lived in The Willows, a Cheshire cul-de-sac that was shaped like a dessert spoon and as warm and cosseting as any pudding. Every Wednesday morning, sometime between eleven and twenty-past eleven, a big cream van would park at the corner of The Willows and Ashcroft Road. Seconds later, Lennie, who drove the van, would spring out of the driver’s seat, open the double doors at the rear and lower the wooden steps so that the residents of The Willows and Ashcroft Road could climb in and choose their groceries.

The contents of Lennie’s van were unpredictable, so the housewives of The Willows relied on the local mini-market for the bread or biscuits or tinned ham they needed. But when the van arrived, they all made sure to purchase at least one item as a means of ensuring that it was profitable for Lennie to keep them on his route. So it was that Lauren and the other children of the two streets came home from school on Wednesdays to Watch with Mother and a whole array of unnecessary treats: bottles of cream soda, slightly soggy Battenberg cakes and gooey peppermint creams.

To the children of The Willows’ dismay, Lennie took a break over the long summer school holiday – so generally speaking Lauren had to be off school unwell, but not too unwell, in order to jump into his van herself. And this she loved to do. Everything about Lennie enchanted Lauren: the twinkle in his eyes, his creased forehead, his Welsh lilt, the way he added up the bills on a small pad of paper with a too-small pencil. She liked that the van was stocked with as many extravagances as essentials, that the whole operation involved adults behaving like children. It was make-believe shopping; grown-ups pointing at a bag of sherbet dip as if it were a serious transaction.

The very best part, though, was the smell. To enter the van was to be instantly transported to a new world, one that was permeated with the scent of stale custard creams and old and broken jam tarts. Lauren supposed the van had never been cleaned, for there was not one whiff of disinfectant. It smelled only and seductively of years of cakes. It was so old-fashioned that there were no lamps in the back – so the labels of the packets and the bottles were illuminated only by daylight from the open doors or the light that filtered in through the thin curtain that separated the shelves of food from Lennie’s cabin. This was why Lauren’s favourite time to visit the van was on sunny days: when the tiny food hall would be filled with dust sparkling from its contact with icing and sponge fingers.

It was, for Lauren, safe light. Delightful light. She had been inside the van only four times but always felt completely protected. No Santa’s Grotto would ever compare, no Santa’s Grotto ever smelled as lovely. Above all, thought Lauren, no Santa’s Grotto could resist the temptation to overdo the lighting. In the van, Lauren would stick out her tongue, and Lennie would smile because so many children tried to taste the floating sugar splinters, but Lauren seemed to be tasting the light itself.

The Willows was not unreasonably named, as three of the houses had willow trees near their front doors. The street comprised two rows of small semi-detached houses which fanned out to make room for five detached homes, the grandest of which sat at the apex, as if keeping a patrician eye on them all. The grandest house of all had a tall narrow pane of green and red stained glass depicting tiny sheaves of golden wheat above the front door – just in case anybody was in doubt as to its status – and its front and back gardens were twice the size of the rest. Lauren, along with her parents, Bob and Vera, lived at No. 13, the first of the detached houses on the right.

It ought to have been a place simmering with social tension and envy, but The Willows was nestled in aspirational Cheshire and, as the years rolled by, the residents socialised with ease. Every Christmas morning, the Harpers in the grandest house welcomed them all, even the family at No. 2 with their boisterous twin boys who fought each other from the moment they woke to the moment they fell, exhausted, asleep, for sherry and mince pies. Meanwhile, on sunny days, the children would pile into the centre of the spoon and whizz around on tricycles or roller skates. The summer of 1975, when it rolled around, was dominated not only about speculation on the whereabouts of the murderer Lord Lucan and the rise of unemployment, but also by the Squeezy Bottle War. Empty washing-up liquid bottles were turned into water pistols and many a child would scream as the contents, still soapy, were squirted into their eyes. With the exception of water fights, however, The Willows was a place of utter safety.

One Thursday after school the following summer, Lauren was sat in her bedroom on her sheepskin rug, making a birthday card for her mother and sipping occasionally from a plastic tumbler full of cream soda, each sip evoking the seductively sweet smell of Lennie’s van. She was immensely proud that her rug was white; white like a sheep and not dyed pink like the one in the bedroom of her friend Debbie.

Lauren’s current obsession was to create pictures with complicated skies. She was using the stencil of a crescent moon when, to her right, a thin beam appeared, which to most observers, had they been able to see it at all, would have looked like a sharp shaft of sunlight. Lauren knew better.

She sighed, and tried to ignore it by pressing her nose against her artwork and wondering how paper was manufactured and how so much of it was stored in her father’s big steel desk which sat incongruously in the spare bedroom. She had once covered the desk with stickers of stars and rainbows and was still not sure if her father had been cross, or had pretended to be cross but quietly found it as loving a gesture as she had hoped. Grown-ups, she thought, were always secretive. They were so secretive that it was possible they all saw special sunbeams which, if peered through, granted tiny windows into other worlds, too. Lauren doubted it. But she, on the other hand, had been visited by these peculiar, dangerous sunbeams for as long as she could recall.

Two years ago, when Lauren was six, a steel sunbeam had appeared in the kitchen, and Lauren’s mother had walked straight through it. Lauren had caught her breath, waiting for her mummy to clutch her head and sit down trembling, perhaps even to fall through to another place, but nothing had happened – and so, over time, Lauren came to understand that the curious metal, rod-straight beams belonged to her and only to her. Experience also taught her that it had been a mistake for her to turn to her best friend, Debbie, one day and say, ‘Look at that.’ Debbie had looked and, seeing nothing, had called Lauren Ghostie Girl for an hour or so before forgetting, as six-year-olds tend to do, why she was saying Ghostie Girl at all.

The Christmas after the Ghostie Girl incident, during the school nativity – dressed as an angel and feeling so happy about it that she suspected she might just be capable of flight – Lauren had seen a plethora of beams slice across the heads of the audience. It was as though Baby Jesus were sending the school his approval for their efforts to make his stable cosy with a fanfare of light, and Lauren had turned her head to her fellow angels, expecting to see her own awe mirrored in their eyes – but she saw only glassy tired eyes or vain eyes or look-at-me eyes. No one saw what she saw.

But the unease never lasted long, and the next day, the whole of the next day, was spent choosing, then buying, then decorating the Christmas tree with felt Santas, silk angels, frosted glass icicles – no tacky tinsel – realistic feathery robins and white twinkling lights. Vera, Lauren’s mother, had looked on, feeling inordinately proud that she did not have a child who wanted to throw a dozen plastic snowmen at the tree but could see Yuletide in an aesthetic way.

By seven, Lauren had noted the way adults responded to her sunbeam stories and had learned to avoid mentioning them. She had also noted how her school friends were ignorant of these gleaming gateways, and that to insist they were real was to be met with teasing, laughter or annoyance. Still, it was hard for her to remain silent when sometimes such lovely things happened through the miniature windows.

‘You look nice in a silvery silky dress, Mummy,’ Lauren had said one night when her bedtime story was finished. She’d started to care about clothes, started to notice that her mother dressed a little more elegantly than the mothers of her friends. Fashion was such a grown-up thing and she wanted to show she could make sense of it – that she might only be seven, but she had style – and a light beam on the stairs that morning had revealed her mother smoothing down a magical-looking skirt. Vera did not own a silvery silky dress and she frowned as she closed the book.

‘You mean, darling, that I would look like nice in a silvery silky dress.’

Lauren had been sleepy and off-guard.

‘No, you do look nice, and the dress is more gorgeousy than anything the Bionic Woman wears.’

Vera considered herself to be a devoted, sensible mother but allowed herself to feel occasionally undermined by her daughter’s murmurings. She wondered if Lauren wanted a different sort of mother, a prettier one perhaps or one that constructed more elaborate cakes. Vera wondered if being at home meant her daughter took her for granted. Then, she would wonder if, on the contrarty, Lauren resented her having a Saturday job, or if her daughter was simply lonely.

Vera was occasionally disconcerted by her only child. When Lauren had been much younger, she had watched her tilt her head and squeeze her eyes as if peering through a crack in the wall, a crack that was not there. Quietly, stood to one side, Vera would watch her daughter peer, watch her smile or grimace, watch her sigh, watch her turn away. While Lauren was mesmerised, Vera would vow to take her to the doctor, to speak to Bob, her husband, to investigate what might be happening, but as soon as Lauren turned away and carried on with being a child, Vera scolded herself for worrying and did and said nothing.

Lauren, sitting proudly on her white sheepskin rug, studiously ignoring her sunbeam, was now the wise old age of eight, and had long absorbed the peculiarities of her life in the way that most children can be hugely accommodating of anything; be it abuse, poverty, neglect or boredom. She knew that up close the sunbeam currently piercing her carpeted bedroom floor appeared to be a streak of mirrored glass but that, when viewed closer still, so close she almost touched it, there would be no reflection whatsoever. She also knew, she had known for a long time, not under any circumstances to touch the mysterious ray of light.

For while it looked heavy and solid and glistening, her hand could glide straight through it as if it were indeed a sunbeam. She could even walk through it unimpeded, but to do so was to feel instantly cold with a sharp, nasty headache that lasted for hours and made it impossible for her to do anything but lie down and moan. As this had once prompted her parents to take her to hospital she knew better than to let it happen again.

It was not her headache that had so worried her parents as the fact Lauren had mumbled through her pain about her other mummy. Her parents had stared at each other, perplexed and a little scared. If they, too, saw the beams, then they would surely not have been so frightened.

‘I don’t like my other mummy,’ Lauren had whispered indignantly, her eyes squeezed tight, her hands cold to the touch.

It was true, on that occasion she had not liked her other mummy, but subsequently she had liked her just as much as the regular one. Gradually, Lauren had come to know many mothers, all spied with caution through the prism of the magic glass, just as she had learned to accept the views through her beams, which were usually pretty dull and often almost exactly the same as the scene would be without her magic glass. Only now and again would the view cause her to gasp – such as when she caught sight of her mother, supposedly in the boutique she helped to run on Saturday mornings, sat on Lauren’s own bed throwing Lauren’s own dolls at the wall and spitting with rage.

Noisily, Lauren devoured the last few drops of cream soda, put down her stencil and crawled from her sheepskin rug to the base of the beam, which had appeared at a forty-degree angle and refused to be ignored any longer. She aligned her eyes and slowly inched forward so that the shimmering stopped and the view began. Peering through, she saw the same bedroom in the same home she was sitting in. Taped to the wall was a child’s painting of the sun shining down on rows and rows of pink and purple flowers. Lauren made a small scoffing sound and looked away to the wall in her own room, upon which was taped a much cleverer child’s painting of a full moon hanging over a wild sea out of which darted flying fish with smiling faces.

It seemed that, like so many of the sunbeam views, this one was boring and fairly pointless so, carefully, and with a sigh, Lauren set to work again on her card, making today’s crescent moon yellow but the stars silver, humming, ‘Happy birthday, dear Mummy, happy birthday to you,’ and not wondering at all who had painted the simple sun and the garish pink and purple flowers.

Nothing made Lauren happier than creating pictures for her parents. She was a perfectionist. Many a crayoned red-roofed house, colourful garden and smiling cat had been binned before she deemed it worthy of handing over. It mattered to her that, when her parents gushed their delight, the picture was deserving of such rapture. It was not about competition – after all she had Bob and Vera’s undivided attention – but being an only child conferred a deep sense of responsibility. If she was all they had, then she had better be good. She had better concentrate on the job at hand, and not become distracted by strange other worlds.

Vera was delighted with her daughter’s card, and she hugged her tightly. Lauren hugged her back.

‘You’re the best of all my mummies,’ she said, forgetting her own rules in her haste to say the most loving thing she could on her mother’s special day.

Vera stiffened but carried on hugging.

‘Well, cherub,’ she said, ‘I’m afraid I’m the only mummy you’ve got.’

Lauren sighed contentedly and Vera relaxed. She reminded herself that she had had an imaginary friend called Tuppence when she was four. Lauren was, at eight, a bit old for such things, but Vera could tell her daughter was creative and with creativity came, perhaps, an overexcitable imagination.

It was such a lovely, long hug. Bob walked in and chuckled and said he had booked a surprise Sunday lunch for the three of them. This turned out to be not a silver-service affair, but cold chicken, tongue, ham salad and homemade coleslaw at No. 17 where Lauren’s friend Debbie lived with her parents, Julian and Karen Millington, her bright pink sheepskin rug, and her brother, Simon. But Vera was amused by the conspiracy and the fact that Bob both shaved beforehand and cleaned the sink properly after having done so. She knew she would have to wear the long white silk scarf Bob had bought for her and that meant she could not wear the wraparound dress she had bought from her boutique with her fifteen per cent discount the previous day. She stood in front of the mirror before they left for lunch, Lauren by her side.

‘Long scarves go only with long trousers,’ she told her daughter, and Lauren gazed admiringly at her mother’s self-assuredness, her smooth, blemish-free skin, her elegant neck, her tiny wrists. When she dressed her Sindy Doll she would think how much more elegant her own mother was compared to the doll, or the other mothers of The Willows and especially when compared to the other mothers inside the sunbeams.

It always thrilled Lauren to notice the differences between her and Debbie’s homes. From the outside, they were almost identical, bar the fact that No. 13 had a green garage door and No. 17 had a white one. Inside, though, they felt unrelated. Vera was very partial to glass partitions and bold wallpaper such as the orange-and-brown paperchain pattern in the living room. Debbie’s parents preferred solid walls and had placed textured magnolia on them.

As a giant trifle was hauled onto Debbie’s dining table, a metal sunbeam appeared in front of the sideboard. No one but Lauren noticed it. She was used to this by now, used to being different. She sometimes felt pestered by the magic silver string, as though a smelly boy were pulling at her ponytail. She also was beginning to recognise that the nagging cracks of light lingered longer if not given attention. But it would not be so easy, she thought, to give this particular beam attention while in a packed dining room in someone else’s home.

She ate her trifle with one eye on the beam, which was noticed by Karen.

‘Have you spotted our wedding photo, Lauren?’ she asked.

Lauren stopped eating mid-mouthful, wondering if it was rude to look at another family’s photographs, then realised this would give her a reason to peer closer at the sideboard.

‘Can I look?’ she said, and sprang out of her chair. Fortunately, no one paid too much attention to the way Lauren cocked her head to one side and stooped oddly.

‘I was so slim back then,’ Karen twittered self-consciously. Karen liked Bob and Vera but Vera had arrived in platform clogs worn under maroon flared trousers, looking, to Karen, like some sort of film star, and she had had to tug at her own hair in order to clear her head and remind herself that it was Vera’s birthday and she had every right to look a million dollars.

Lauren stared into the metallic gap. Through it, she could see Karen sitting in a chair, her eyes closed, her cheeks hollow, her lips pursed. She was bony and brittle like a twig. It made Lauren feel sad. There was never a soundtrack to the visions, but Lauren could sense a weighty silence, a room enveloped with pain.

‘Pass the photo here, love,’ Karen said, keen to make sure Vera had a good look at how petite she had been on her wedding day.

Lauren had to loop her arm under the beam and lean back a little to ensure she did not touch it. Watching her, the quiet bored Simon decided his sister’s friend was, like all girls, uncoordinated and a bit stupid.

Eventually the long hot summer of 1976 ended, school restarted and Lauren was placed in charge of the art and stationery cupboard in the corner of her classroom. This was dressed up as an honour but it really meant that the teacher could avoid having to tidy up. Nevertheless, Lauren took her role very seriously. She loved the trays of string, of glue, of poster paint, of crayons, the stacks of thick coloured paper, the pencils and pencil sharpeners, the hole punches. It was her domain and she even sort of liked how for a few seconds, as the strip light flickered into life, it could be pitch-black in there. It was a small windowless space that smelled of plasticine and turps and, oddly, of forgotten fruit gums, and not once had a rod of light appeared. And yet.

Deep into her cupboard duty one afternoon Lauren heard a scuffling outside her door. It sounded to her like mice so she turned sharply and noticed a luminescence clinging to the cupboard’s keyhole. She bent down and peered through the gap and saw her classmates rushing to sit down as the teacher, beaming, lowered the stylus of the portable record player. This could mean only one thing. The record player was used to play just one record and one record only, ‘A Windmill in Old Amsterdam’. This was how birthdays were marked in her school and the children would sing with gusto as the birthday boy or girl was more or less ignored. ‘I saw a mouse!’ they would shriek along with the scratchy old vinyl record.

Lauren felt left out. How could they? she thought. The Windmill song was taken very seriously. The teacher would wait for the children’s full attention and only when there was an expectant silence would she ease the stylus onto the record. For the first time in her stationery cupboard Lauren felt lonely and left out. She would have to act in haste not to miss the opening refrain so she firmly and a little indignantly pushed the handle and stepped into the room singing, ‘A mouse lived in a windmill—’ and then she stopped short. No child was at their desk, the portable record player was still on the shelf.

‘Anything the matter, Lauren?’ asked the teacher as a few children giggled.

‘Was there…? Were you all going to sing?’ she said in a whisper.

The teacher shook her head distractedly. Gavin was handing out sweets again, an eight-year-old version of a spiv on market day. Lauren stepped back into the cupboard and the door clicked shut.

‘Well, I declare,’ she hummed to herself defiantly. She had, after all, always known strangeness and was an adaptable soul. ‘Going clip-clippety-clop on the stair,’ she mouthed as she found a spare drawer for the plastic beads that had spilled on the floor every time the class had an arts and crafts afternoon.

As she sat down for the glass of orange squash the teacher handed out to the children at two o’clock every day a lattice of metallic beams dangled from the ceiling and Lauren took a deep breath to mask a gasp at its majesty. This, she felt, was an apology for the Windmill debacle, and it might have been the first spiritual moment of her life except for the fact that Tracy Campbell saw her gazing at the ceiling and began screaming that there was spider in their midst about to drop into her beaker.

Lauren saw no spider, and wondered briefly if Tracy saw spiders the way she saw metal sunbeams. But she soon worked out that where her classmates had imagination, she had something more tangible. Something that could not be shared, that was more dangerous than the wildest of daydreams and so much more compelling.

A week after her eleventh birthday Lauren was sat in a chair at the optician’s.

Her parents had seen her squinting as she stood before the newly installed bookshelf in the living room. They had also seen her, head cocked in the kitchen, seemingly struggling to make sense of a cereal packet on the table.

‘I don’t squint,’ she said sullenly.

The optician knew an easy sale could be made. The parents were very suggestible to something corrective being necessary, desirable even. But, after a thorough examination, he had to accept that there really was absolutely nothing wrong with this girl’s vision. What’s more, something about the child unnerved him. It was as if she could see through him, see him for what he really was – which was lonely, and obsessed with his receding hairline.

‘She’s fine,’ he said brightly, and Vera shook her head.

‘Well, that’s good news, I suppose,’ she said as Lauren rolled her eyes. She felt spied upon. She had tried to be surreptitious when peering through the shimmering rods, but clearly her parents had sneaked up on her. She would have to be even more careful. She did not live in a world where it was acceptable to see things that other people did not see although she was sure there was a world somewhere where it would have been just fine. In fact, the more beams she looked through, the more it seemed to Lauren that there were endless variations of life; that her glimpses were not big revelations but tiny clues. She was only ever peeking, not properly looking, at what might have been. Or what could be. Or what also is.

By now, she had stopped telling her mother about her other mothers. Gradually she had noticed the stiffening, the frowning, the flushing it induced in Vera and the last thing she wanted was for her mother to be unhappy. Vera, Bob and Lauren enjoyed a contained and contented life. There was no need to spoil it. But Lauren was maturing and starting to wonder what the point was of her visions. Was this to be her life, always ducking under the beams, always needing to see into them?

By the time she was twelve, the beams had begun to gang up on her. Now and again she would walk into a room and be faced with a wall of metallic slices. There could be fifty or sixty of them blocking her path. It was impossible for her to duck or jump or squirm past them. These were the only occasions when she felt intimidated by the visions. It was like finding her bedroom window fitted with iron bars or being trapped in a public toilet cubicle. Fortunately, it did not happen very often and so far it had not caused a stir but she did worry that one day it would. That the headmaster of her new secondary school would ask her into his office and she would be unable to step through his door. Or that the beams would multiply to the extent that they formed a wall of steel, trapping her so that she could not even see what was ahead, only what else might be around her.

Otherwise, school was just fine. Lauren had forged a reputation for being artistic and creative. Little did she realise that the vast majority of secondary schools would have had no time at all for her clever cartoons and bold montages, that most teachers would have told her to spend less time with tissue paper and more time on her spelling tests. It was a school that almost treasured its pupils and that made it, almost, a wondrous place to be. There were sports days, plays, concerts, film clubs and art exhibitions on a seemingly endless reel. No one wanted to leave. Its sixth form was full to bursting. It was a very happy place. Or at least it was happy in Lauren’s day-to-day version.

She knew by now that she was seeing alternatives, through her glittering rods, to what was really there, and once in the corridor between lessons she had peered, making sure not to squint too heavily, and seen a bleak school corridor with no artwork and a runt of a boy being spat upon by larger, older children. There was not time for her to dwell on his features, but she tried to burn the image in her mind so she could recognise him if he was somewhere in her real school. But if he was there then he was not in her class and she never passed him in the playground.

It made her thankful that she lived in a kinder place. It made her smile at the staff, make eye contact with the dinner ladies and share her crisps with her friends. This in turn made her liked and popular, which helped to fill the void left by the fact that she could not share her visions with anyone. Nonetheless, it could be lonely, and she thought of her Aunt Suki, who lived by herself, and wondered if, when she grew up, she would have to live by herself too, watching television alone and never joining in the laughter or tears of anyone else. When a beam appeared that night as she brushed her teeth, Lauren muttered a prayer to no one in particular that, when she peeped through, she might see in it her Aunt Suki laughing with friends at a sophisticated party brimming with handsome men, but all she saw was the bathroom she was already in – albeit a version that had a sink with a large brown stain.

By the summer of 1981, Lauren was approaching thirteen and beginning to feel the first stirrings of teenage claustrophobia. Her home was so quiet, so full of routine. Not even the Royal Wedding was enough to spice it up although it was nice that she, Vera, Karen and Debbie were able to watch it – all the girls cooing together while Bob and Julian went crown green bowling with Debbie’s grandfather. A whole week could pass without a visit from Aunt Suki, without even the visit of a neighbour; so the visit of sunbeams, no matter how many, was a welcome diversion, even the ones where there was a young boy being cuddled by her mother which made her feel a spurt of jealousy. There were days when just bringing her father a mug of tea as he pottered about in his messy garage was a highlight of the weekend. Usually she disliked it when her parents chatted about politics but it was different when it was just her and her dad in the garage. Bob was mesmerised by Margaret Thatcher and Lauren deduced that he admired her, feared her and was baffled by her.

‘How do you reckon she and the Queen get on?’ he would ask his daughter, and they would engage in a role play that invariable ended with Bob mimicking the Prime Minister and saying something silly such as, ‘Where there are biscuits, may we bring tea?’ and the two of them would giggle helplessly.

‘One day I’ll sift the rubbish from the necessary,’ he would say as he rummaged in yet another cheap plastic box for a spanner or a rusty pair of secateurs, and Lauren would look at the oil stains and the cobwebs and say, ‘Of course you will, Dad,’ and they would laugh conspiratorially, then walk together into the kitchen where Vera might be mashing eggs with butter, mayonnaise and cress for sandwiches – the clearest indicator of all that the three of them were ‘going for a drive’.

It amused Lauren greatly that, during these drives, her parents derived so much joy from pretending that they did not know where they would end up even though she knew that they discussed in detail their next outing to make sure that they saw every stately home or went on every country walk at the time when it would be at its most beautiful. Lauren could appreciate the beauty of Lyme Park’s architecture and the rhododendrons that lined the still waters of the local quarry but, all the same, she was bored of tagging along, no matter how tasty the sandwiches or how good a mood her parents were in.

It was not normal, she grunted inwardly, that an invitation to a treasure-hunt lunch at Easter at the home of Peter Stanning, her father’s boss, should have been such a highlight in her life. But there had been plenty of other teenagers around her age there, and also a decadent sort of freedom to it all, with the youngsters permitted to roam as they pleased. Lauren had liked Dominique, a girl home from boarding school, who carried a camera around her neck and took photographs of tree stumps and discarded bikes. Dominique was the daughter of who Mrs Stanning referred to as ‘dear old friends’ and it struck Lauren that this was evidence of a class divide. The Pailing family did not have any ‘dear old friends’ whatsoever. They just had people who they ‘used to know quite well’, like the family who had lived near Lauren’s primary school before moving to Leighton Buzzard.

‘They have eleven bicycles in this shed but thirteen bike wheels,’ Dominique had said to Lauren as they stood before one of the many Stanning outhouses, and Lauren had fervently wished she was capable of noticing such details. Later that evening, she told Dominique that she too was an artist, that she did not have a camera but liked to draw and to paint, and Dominique had replied that she, Lauren, possessed the greater gift. Yes, Lauren, thought, I really like Dominique. But then she disappeared off to boarding school and Peter Stanning did not hint that his wife would be hosting any more such gatherings. Lauren recalled how Mrs Stanning had been a distant sort of hostess, as if she had something much more important to be seeing to, while her husband had been friendly and attentive and had spent ten minutes looking for some Savlon cream to rub into Dominique’s elbow when she scratched it while making space for her camera lens through a lattice of wild and thorny roses. Peter Stanning had looked Dominique in the eye and said, as if speaking grown-up to grown-up, that she should pursue her dream in photography.

In the absence of parties, Lauren increasingly gravitated towards the house across the cul-de-sac spoon where there was noise and the odd raised voice, the squabbling of siblings and the laughter of parents who liked a midweek nip of booze.

She always knocked, but no one ever physically answered the door. Instead Debbie or one of her parents would call out for her to come in, and sure enough the back door was always unlocked. Debbie had begun to sequester herself in the dining room on the basis that her brother had the largest bedroom and it was an insult to expect Lauren to perch next to her on her small bed. They would sit, instead, on uncomfortable dining chairs, trying to feel sophisticated as they leafed through magazines bursting with shoulder-padded women, and swapped gossip or pretended to complete homework as they sipped at too-hot Pot Noodles. Above them could be heard the heavy beat of Simon’s music and muffled lyrics which made Debbie groan and pout.

‘The Cure. Again,’ She would sneer.

As the months passed, Lauren spent more and more time at Debbie’s. She quietly considered The Cure to be intriguing. She inwardly relished the chaos and the fact that sometimes the music would be so loud that the furniture would actually bounce. Furniture never bounced in her house. At Debbie’s, if you wanted to open a tin of hot dogs and heat one up you could do so without anyone telling you it would spoil your appetite. If the terrible twins from No. 2 rang the front door bell, they would not be ignored, as they were in Lauren’s house, but chased down the road and even sometimes called back and asked if they wanted to watch the football on the telly, whereupon they would turn into identical pink-cheeked curly-haired cherubs, dunking their Jacob’s Club biscuits into beakers of milk, glued to the progress of Liverpool in the European Cup.

And should Simon make an appearance in the dining room, Debbie would throw a coaster at him while Lauren would wonder what the music was that had now replaced The Cure in his affections and whether when he smiled at her it was in sarcasm or friendliness.

‘You’re tagging along with us to Cornwall this year, then?’ Simon said one evening as he threw a coaster back towards his sister.

Lauren opened her mouth but could think of nothing to say.

‘Hey, Cornwall’s not that amazing,’ Simon said and walked out.

Lauren and Debbie faced each other, their eyes gleaming.

‘Did my mum speak to your mum?’ Debbie said.

‘I’ll find out,’ Lauren said, feeling as if she were the last to know about the most exciting invitation she had ever received, and she skipped home across the cul-de-sac after giving Debbie a hug, the first hug they had shared feeling like sisters.

‘Were you ever going to tell me?’ Lauren said as she burst through into the kitchen.

‘Of course I was, sweetheart, I was just thinking it through, that’s all. I think perhaps you’re a bit young to be away for a fortnight.’

This was an understatement. In fact, Vera’s instinctive response, when sat at the kitchen table nursing a cup of tea opposite Karen, who was busily dunking her biscuit and burbling about the beauty of the Cornish coastline, had been to laugh it off as a wild and ridiculous suggestion. Vera was as much fun as any thirteen-year-old could ask their mum to be but deep down she was panicked that Lauren was all she had. And, since she was thirty-six, Lauren was likely to remain all she had.

‘It’s not America, Mum,’ Lauren said pleadingly. ‘Can I phone Granny? You do know she thinks I should be busier in the holidays and this will make me much busier.’

Vera had no retort that made any sense. Beryl, her mother, was right. Lauren should be out and about with friends who had siblings. Vera wanted to tag along on the holiday, but Bob was bogged down at the office and would have been wounded had she left him to his own devices every evening for a fortnight. All the same, two whole weeks without Lauren would be torture.

‘She’ll be fine, she’ll have fun,’ Bob said, coming into the room and giving his wife a tight hug.

Allowing her only child to leave for a fortnight made Vera want to burst into tears, but eventually she had taken a deep breath and given her consent. She threw herself into packing a large suitcase with the attentiveness a trip to the Niger Delta would have deserved. Lauren stared at the plethora of ointments and plasters and double quantities of sanitary towels and instead of griping as a teenager might have been expected to, she shouldered the ridiculousness. It was her burden as an only child to indulge such behaviour. Only when on the road with her friend did Lauren make a joke about the fussiness of her mother. Only when she had waved Lauren off did Vera succumb to a couple of heaving sobs of love and self-pity.

Debbie’s family had rented a huge house not far from St Ives. They were joined by Karen’s sister and Karen’s sister’s best friend and her son Brian, who was a gangly twelve-year-old who stuck tightly to Simon as if girls carried infectious diseases. Slowly, they all relaxed and Lauren marvelled at the noise and laughter and the cheating at cards and the arguments over draughts. Other families popped by. Karen’s sister even went on a date. It was all silly and riotous enough for it not to matter when it rained. The adults wandered around in a perpetual state of tipsiness, clutching glasses of wine or beer as Phil Collins played on a perpetual loop in the background. It was hypnotically loud and busy. They all ate when they felt like it and the nightly barbecue lasted for three hours, so that Lauren regularly lost count of how many sausages she had eaten.

On the second evening, Simon was placed in charge of flaming some fatty steaks. As Lauren settled into a canvas chair with a plastic glass of lemonade a thin glistening steel rod appeared in front of her nose. She sharply pulled back her head, fearful of touching it, of the holiday being cut short by the nasty headache such a collision would provoke, and then gingerly leaned forward to spy upon another world. She expected to see simply more sausages and perhaps a new face or two, so unremarkable had been most of her recent peeks through the glass. Instead she saw Simon, wearing a faded red T-shirt that suited him better than the black one he was really wearing, squirting lighter fluid onto the hot charcoal that caused a flame to angrily reach up and slap his face, and setting fire to his clothes.

Lauren closed her eyes as her heartbeat quickened. She breathed in deeply and opened her eyes. The beam was gone and so was Simon but then he emerged, really re-emerged, walking from the shed to the patio, a small can with a spout in his hands. He had changed out of his black T-shirt and was wearing a faded red one.

Lauren was both transfixed and horrified. She wanted to shout to him to stop but lacked the courage to do so. Simon paused and held the can close to his face as he read the label.

‘Dangerous stuff,’ he said to his father, who grabbed the can from his hands.

‘Too right,’ he said.

Lauren exhaled and spent the rest of the evening in such high spirits that Lucy, Karen’s sister, kept asking what she was really drinking.

Breakfast was Frosties or slabs of white bread from the freezer toasted to never the acceptable colour. Lauren noted that Simon would tip back his head and let the dry cereal fall from the packet into his mouth and then take a gulp of milk while winking at her. At least she thought he was winking at her. It might have simply been that it was impossible to eat breakfast in such a fashion while keeping both eyes open.

This was life, she thought. She was growing up. She had experienced a short burst of homesickness on the first night that had been interrupted by a glistening beam piercing the end of her camp bed. Through it she had seen a toddler sucking at a bottle of milk, its eyes wide, its toes curling around the ears of a small white teddy bear, and the vision had instantly cured her of her loneliness. I’m not their baby, she thought indignantly, and they had better get used to it.

Eleven days into the holiday an old Jeep appeared in the driveway driven by a man Lauren had not seen before, but Debbie and Simon and gangly Brian piled in and so she did too. There were no seats for the youngsters; they just sat on the back and clung on facing the way they had come. The lanes, banked by thick hedgerows, became increasingly narrow. Lauren could hear her mother wailing about how dangerous it all was and made a mental note not to mention this particular outing when she got home. Debbie started singing Kim Wilde’s ‘Kids in America’ and they all joined in, even Brian, because they were in a Jeep and felt they could be in California, and because it was easy to sing a song by Kim Wilde because Kim Wilde couldn’t sing all that well herself.

Then the driver veered sharply round a bend and braked as a tractor approached and Lauren was thrown out of the back of the Jeep and onto the road. And the singing stopped.

Lauren felt like a small hard rubber ball bouncing down some stairs. She felt her neck snap, painlessly, like the wishbone of the Christmas turkey. She felt warm blood trickling across her chin. She felt the world spin, the colours of the beautiful early evening dim into sludge brown, then grey, then black.

She opened her eyes slowly, not out of pain or the fear of pain, but out of a curious sort of trepidation.

She knew without thinking, without calculating, the way that she knew her name and she knew that ice was cold, that she had died.

Part Two (#ulink_943f1857-70c6-556f-bfaf-49ad91be79bc)

Lauren (#ulink_34a5f841-957b-588f-8cb3-457e53419a29)

Whereas other little girls in The Willows might have clasped their hands together and prayed to God or to Jesus or grandparents in Heaven or a pet in the afterlife, Lauren had formulated her own religion. It had never been taught to her at Brownies or Sunday School or in assembly. She had not heard it mentioned on television or in the conversations grown-ups had over cups of tea or gin and tonics.

Lauren had always had her sunbeams and they had always shown her windows to other places. She was sure that everyone had these other worlds but that, for some reason, no one else could see them. What was the point of it all, she couldn’t be sure, but her beams suggested to her that instead of dying, she could shift.

Shifting was, she thought, more sensible than Heaven. More convenient than Heaven. More realistic than Heaven. Nicer than Heaven. Her Grandad Alfie had confirmed it.

‘We carry on,’ Grandad Alfie had whispered to her when she was eight or nine and had asked him if he would still be able to see her when he died.

‘Where?’ she had whispered back.

‘Somewhere nicer, or at least somewhere where we aren’t dead,’ he had laughed throatily but Lauren had not laughed along. She had simply nodded seriously and he had stopped laughing and nodded too.

When Grandad Alfie had died, she had known he had not been ready to actually die. He was sprightly and funny and liked to beat younger men at cards. He had carried on regardless, she was sure of it. He had carried on oblivious to the silent tears of Granny Beryl, the misery of Vera and the sad hymns in the church.

That had not been her grandad’s time and this was most certainly not Lauren’s time. She was thirteen. She could not die. She opened her eyes. She was in a hospital bed and she was sore. She could not move her head, it was being held in place by a plastic contraption and it made her feel claustrophobic.

Her mother’s face loomed into view. Vera was both relieved and panic-stricken. Vera looked different somehow beyond the frown of desperation, the fear of what her daughter’s injuries might mean. Lauren forgot about the pain and mounting unease and stared and stared at her mother’s face. Though it was not what she was expecting, she recognised the face. She had seen it pouting sadly through the magic glass.

‘Hello, Other Mummy,’ she whispered through cracked lips before sinking back into unconsciousness.

The next waking was an emotional affair. Vera stroked her daughter’s cheek trying to disguise how hurt she felt that Lauren seemed, ever so slightly, to flinch. Lauren sneaked a glance at her mother’s forehead. It was dirty. How ridiculous. Had she tried to apply her eyebrow pencil while driving?

‘You’ve got… stuff… on your face, Mum,’ Lauren said.

‘Oh,’ Vera said, disappointed, adding with false brightness, ‘I’ll go to the bathroom mirror.’

Vera returned having rubbed off the faint traces of rouge she had applied simply to disguise her anxious pallor so as not to worry her daughter but Lauren had slipped back to sleep. Vera waited until her daughter stirred once more.

It hurt to move but her right arm was unharmed, not even bruised, so Lauren gingerly lifted her hand to her mouth and licked her forefinger.

‘Lean closer, Mum,’ she said and gently rubbed at her mother’s forehead. This time it was Vera’s turn to flinch. She had never liked her mole to be touched.

Lauren frowned. The small but annoying mark on her mother’s face was not flat but raised and rubbery and solid and not at all like a smudge of eyebrow pencil or an errant piece of melted chocolate. She squinted at Vera suspiciously and then at her own right hand. There was silence, while Vera realised that the spot her daughter was trying to rub away had always been there.

‘What a funny thing to forget about, darling,’ Vera said, again with forced brightness.

‘I didn’t forget,’ Lauren said angrily but she was bereft more than angry and she wondered why she felt as if her mother were dead when there she sat, on the bed, breathing and talking and being so obviously loving.

Through her recuperation her parents, and her mother in particular, had been attentive and doting but Lauren had become frustrated by Bob and Vera’s lack of a sense of fun. Before her holiday to Cornwall, Lauren had hated Benny Hill, but loved how her father had giggled like a schoolboy in front of the television. Mr Hill had now vanished from their lives, and so had the giggles.

‘Have they stopped making…’ Lauren started to ask, but discovered she suddenly could not remember the comedian’s name. She closed her eyes and tried to picture his face but she could not even do that. The harder she tried the more distant he became and within the hour she had forgotten that such a man had ever existed.

Lauren had fractured her skull, broken ribs, snapped her arm and splintered her right kneecap. It had been sore, then boring, then sore again. It was Bonfire Night before Lauren felt able to walk outside. The Harpers in the grand house were holding what the invitation they had pushed through the letterbox called their ‘annual firework party’. They had never held one before, but Lauren allowed this detail to pass without letting it annoy her. The Harpers had spent a lot of money on the display and the cul-de-sac residents cooed accordingly. Lauren, though, was more intrigued and impressed by the Harpers’ stained-glass window which seemed both familiar and not. It was decadently large, and depicted a white dove against an expensive azure-blue sky.

Her father worked slightly longer hours than she recalled him working before the accident, and her mother did not go to work in the boutique on Saturdays. Lauren wondered why she thought she would work there, so little interest did Vera seem to have in clothes. Her mother was altogether just a little bit less outgoing since the accident in Cornwall. It must have knocked her confidence, Lauren thought. Her skirts were slightly longer, her jumpers less jazzy, but she was just as tender and loving and smelled the same. Yes, she smelled exactly the same.

Gradually, Lauren forgot that she must have shifted to somewhere else. So many things felt off-kilter but they were small things and the doctors all said she might have lapses in memory. She did not push the point, she did not tell them that there were no gaps in her past; that her past felt skewed. She did not want these tiny electric shocks of surprise; she wanted to feel she belonged, and so she willed it that her other mummy was simply her only mummy, Dad was Dad, and Debbie was Debbie.

Lauren clung to sameness. It brought her disproportionate joy when she found a small black lacquer box at the back of her wardrobe and knew what she would find inside. She had had a six-month spell of collecting buttons in primary school, and she smiled at how tacky they looked compared to how magical she had thought them four years earlier.

If only the same were true of the garage, which was lined with long splinter-free wooden shelves, upon which were stacked neat wooden boxes bearing brightly coloured labels indicating items such as ‘torches and matches’ or ‘anti-freeze’. She stood, watching Bob proudly fishing out a nail from a box of nails that were all the same size, and wondered why she pitied him. She brought him a mug of tea one cold Saturday morning and he was grateful and he smiled and told her how lucky he was not to have a stroppy and thoughtless daughter, but then there was a silence and she walked away feeling less warm inside than she had expected to.

Debbie’s mother Karen was changed in other ways – ways that everyone, not just Lauren, could see. It was the guilt she felt over the accident in the Jeep. For weeks she was unable to be in the same room as Lauren without bursting into tears, and Vera, who had originally been tempted to freeze her out of their lives, was melted by her neighbour’s remorse and they became closer friends than they had been before.

The next summer, the curtains were tightly drawn against the sun so that Bob and Vera and Lauren could watch the tennis from Wimbledon, cheering on John McEnroe and rooting for the bespectacled but pretty Jocelyn Evert, and through a tiny gap popped a concentrated shaft of sunlight fizzing with dust. Lauren felt a bolt of indigestion. It was like the unannounced visit of a long-forgotten friend.

It took the crack in the curtain to make Lauren remember that she used to see a different sort of sunbeam, magical thick ropes of metal that were both fascinating and cruel. She sighed at the shock of the sunbeam and let it go. She could not even remember if the beams had exhausted her, entranced her or worried her. In the weeks that followed, she had dreams about the few occasions on which multiple beams had appeared, blocking her path as if angry with her, but the dreams ebbed into different dreams about vapour trails and knitting and a sports day tug-of-war. She stopped noticing the mole on her mother’s forehead and started noticing the boy playing the lead in the sixth-form production of West Side Story.

Before long, Lauren was able to walk, limping still, past No. 2 without giving any thought to who lived there. The fact that it was a house bereft of any twin boys stopped registering with her. She had accepted, and then forgotten, that the twins had not moved away. They had never lived there. The twins, in this world, had not been born and, perhaps because they had never existed, Lauren was able to absorb their absence as easily as anyone can accept that they left their keys to the left or the right of the table lamp. There was no significance. They were not even a memory, they were the wisp of smoke from the corner of a distant dream.

Mr and Mrs Cork, who did live at No. 2, were on the quiet side, but after an initial moment of uncertainty Lauren accepted that she had known them all her life. They smiled at their neighbours and wrote thank-you notelets to everyone who gave them a gift to mark the arrival of Jonathan, their first child, whose birth had been either ‘difficult’ or ‘botched’ depending on who you spoke to. Jonny would grow to become the mascot of The Willows, the child welcomed into every home because everyone felt a little bit sorry for him but also a little bit amused by his sunny stupidity. And not a day passed that Mr Cork did not wonder what sort of son would have been his first-born child had a different midwife been on duty that night.

Lauren liked to listen to her parents chatting to each other. She yearned to be older, to be free to do anything at any time of her choosing, to be able to talk about politics and money and know what it meant. She noticed that although her father left the house at twenty-past eight every day and arrived back home just after six thirty in the evening, it was the details of her mother’s day which filled the conversations. She wondered if her father was involved in very secretive work or perhaps had a role that was too complicated for casual conversation. Or perhaps his work was so very dull that Vera’s trip to the hairdresser’s was a more enriching topic of conversation.

Lauren watched him closely. Was he bored? Vera always asked him how he was when he returned home and he would give an economical reply, exhale and then, brightly, ask what had been happening at home. It was one of the puzzles of adult interaction but just as Lauren thought she was close to solving it, everything changed.

Bob arrived home later than normal one December evening, his shirt rumpled, his hair ruffled. Peter Stanning, his boss, had gone missing. Lauren had, for no reason she could fathom, looked at her advent calendar while she digested this exciting but troubling news. Just two windows were open. She felt she had, right there and then, started a countdown; that Peter Stanning had to be found by Christmas Day.

The police had interviewed all the staff at Bob’s office, the rumours had grown more intense and more upsetting by the hour, and suddenly all they spoke about at home was Bob’s work, Bob’s day, Bob’s world. As they decorated the Christmas tree, her mother winding cheap tinsel around the branches in what was, to Lauren’s mind, an annoyingly gaudy manner, she thought about the tree in the Stannings’ house. If your father was missing did you even want a Christmas tree?

Bob became the celebrity of The Willows simply because he was the only person in the cul-de-sac who knew Peter Stanning. Bob was an accountant. Peter was an accountant. Such dramas did not usually unfold in the world of spreadsheets and tax breaks but there was no disputing the fact. Peter had gone missing. Peter had two sons, Peter had a wife who liked horses and growing strawberries, Peter had a sharp brain and a weakness for slapstick comedy. Bob was slightly worried that he could not be sure if he liked Peter all that much or even knew him properly but it felt right to speak of what a great boss he was. Great chap, very smart, very reliable.

There was so much chit-chat about the missing Peter Stanning that Bob felt reality begin to slip. Christmas Day came and went and still he was not found. The anecdote about the sandwiches Peter forgot and left in a drawer to rot and to stink; was that his story or one he was regurgitating? Bob thought he could smell the rotting chicken as he related the tale but this was Miranda the receptionist’s reminiscence, not his, wasn’t it?

Lauren turned it all into her school project. She produced a cartoon strip that began with Bob and Peter staring at a large graph on a wall, then incorporated the first visit of the police and then the imagined home life of the distraught Stannings. She painted a parcel wrapped in gold-and-red Christmas paper with a gift tag that read, ‘for Dad, Merry Christmas.’ She had to blink away tears as she wrote the message in a delicate but not trembling hand. She hoped he would be found in time for the start of the new school year so that her storyboard could be completed with a happy ending but Peter Stanning remained missing.

For her fifteenth birthday Debbie took Lauren and her other, less important friends to the cinema to see Merry Christmas, Mr Lawrence because they thought it sounded mature. Lauren had bought Debbie a pair of cream leg warmers which the others fawned over as if they were all suddenly living in 1944 and Debbie had been given silk stockings. Julian paid for them all to have a Chinese banquet at the upmarket Mr Yee where Debbie declared her love for David Bowie complete. In the window of Mr Yee’s there was a poster asking for information about Bob’s boss.

The New Year’s Eve of 1983 was a quiet affair. Peter Stanning was still missing in the spring of 1984. Debbie was still Lauren’s closest friend and Lauren was impatient to be grown up, to be in love, to be free of the pain in her knee. Since the incident in Cornwall she had been keen to turn the pages on her life rather than dwell in the moment. Only when drawing or sketching or painting did she slow down, enjoy the task at hand, concentrate on the present.

Sixth Form was, really, Dance Form. Led by Debbie, the girls would attend any disco going to be Madonna or Chaka Khan. Lauren, longing to feel love or be loved, wondered if, had she been able to wear heels after her accident, she would have had better luck with boys. She was buoyed enormously to discover that the female students at the art schools she visited all wore pumps or flat boots or trainers and that they looked sexy and cool and desirable. She wondered if her art project, Peter Stanning is Missing, was cool too, or a sixth-form assignment to be binned.

Lauren leaving home was hard for Vera when it came. Bob, too, was emotional. He ran his finger along the tiny windowsill of Lauren’s small halls of residence room and inspected it for dust. Vera sniffed the air not knowing if she was expecting to smell drugs or a blocked drain or Cup-a-Soup. Lauren was impatient to explore but paused to hug them both, to promise to phone the next day, to love them forever.

In the car on the way home Vera and Bob agreed they had raised the sweetest, most talented of daughters and inwardly they both wondered if they loved her too dearly and whether life in The Willows would be too quiet, too dependent on knowing the date of her next trip home. Right now, a sibling for Lauren would have helped enormously. None had come though, thought Vera, none had ever come, and she let the tears, large dramatic tears, plop onto her lap as Bob, blinking, concentrated on the road ahead. He switched on the radio for distraction and although there was emotional discussion about the Hungerford massacre that had taken place a few weeks earlier, an incident which had been of political and human interest and therefore one both he and Vera could discuss with equal insight, he could hear only a jumble of meaningless and boring words.

‘I just, I just… love her too much,’ Vera said out loud and Bob took one hand off the steering wheel to squeeze his wife’s arm.

It could be worse, he thought to himself. Peter Stanning, for example, was still missing and the house-to-house enquiries had long dried up. And the Jeep, the bloody Cornwall Jeep, well, that could have been an unthinkable thing.

Bob (#ulink_76575a59-a72c-5b61-932d-7f04e6f949aa)

Back in Lauren’s first life, it would be her birthday soon. Bob could not find the words to describe how much he was dreading it. His daughter had already had one dead birthday, six weeks after Cornwall, but it been just another grotesque day among many. Now that Vera had stopped drinking and started caring about the house and the garden and cooking and even the boutique, this birthday could be a setback. He was scared to mention it, scared not to mention it.

He was so grateful to Peter Stanning. He had been stoically kind to them, especially when they began to feel isolated. It had been agony in The Willows. What had felt cloistered was now confining but it was impossible to contemplate leaving Lauren’s room behind for another child to inhabit. And they lived opposite Karen and Julian who had not lost either of their children. Debbie was damaged emotionally but neither Debbie nor her brother had suffered more than bumps and bruises when the Jeep had braked.

The resentment and grief from one side of the spoon mingled poisonously with the guilt and indignation from the other. Ten months passed and then a ‘For Sale’ sign was put up in front of No. 17. Eventually, the removal van arrived and Debbie with her pink sheepskin rug left for a new home, a new school and the hope of new friends who would not fall out of the back of a Jeep.

The rage that had been directed towards Karen and Julian altered its trajectory and Vera began to blame herself. She stopped eating properly and began to drink heavily. Peter Stanning limply handed over another pot of jam as Vera poured him a Scotch which he barely touched. Bob tried to talk about the office. He was back at work but leaving early to keep an eye on his wife.

‘Tell me about your kids,’ Vera had slurred at the petrified Peter.

‘They, um, they’re great kids, Vera, thanks.’

‘And would you let them go off in the back of a crappy old truck?’

‘No, Vera, I wouldn’t but I would let them go on holiday without me and the wife. Anyone would have done that.’

Vera glowered. It left Peter speechless. Bob cleared his throat. Peter stood up to leave as Vera scratched at the table top with an old butter knife.

‘I didn’t want her to go but I let her go,’ she said, the mother’s guilt seeping from her lips, her eyes. ‘What if I had put my foot down? She’d be here now. Sat here, right here.’

Vera stared at an empty chair and then put down the knife and slowly pushed her glass to one side.

‘I’ve drunk enough. I’m sorry, Peter. You’re a good man.’

‘Don’t be sorry,’ Peter mumbled and there followed a strained, normal conversation about the weather and the deliciousness of Peter’s wife’s fruit preserves.

Vera stood and smiled politely and walked with him to the front door. Peter did not know her well but it seemed to him that Bob should be more worried about this suddenly calm, reserved Vera than the angry one who blamed herself.

‘Any time you like tomorrow, Bob,’ Peter said.

‘You should go in early tomorrow,’ Vera said a week later. ‘I’ll have a lie-in and potter in the garden and fix us some dinner and I’ll be fine.’

Bob was relieved. He felt torn between doing the right thing at home and the right thing at work, and work was so much easier to bear than the quietness of their home. After Peter left, Vera cooked him one of her mild fruity curries, the first she had prepared since the accident and they watched the BBC news still reporting on the fall-out of how Labour, led by Michael Foot, were humiliated in the 1983 General Election, by a Tory party that had to Bob’s surprise elected Margaret Thatcher as its leader. Vera did not say how little any of it mattered and even nodded at the political analysis on offer. It felt like the start of something, a life worth living perhaps and he was sure he had Peter’s gentle interventions to thank for that.

But it was Lauren’s birthday soon and so, as they sat on the sofa in front of the TV, he plucked up some courage.

‘Love, I’ll take the day off next Tuesday. Maybe we can go and see Suki or drive somewhere quiet and go for a long walk. Whatever you want, love.’

There was silence and then Vera turned and kissed him on the cheek.

‘Thank you,’ she said but she did not think ahead to the long walk, she thought back. Back to that moment when, alone in the house, with Bob at work and her daughter on her first holiday without her, Vera had pouted into the mirror. Her complexion was youthful, her skin smooth and unblemished. She had a mole close to the top of her left shoulder and she often wondered how she would feel if that mole had ended up on her chin or her cheek or her forehead. One of her teachers at school had a strange sort of wart on the tip of her nose and Vera had thought it ridiculous that it had never been removed.

She was young enough yet for another baby, she had thought. She was feeling upbeat about life, about miracles. Bob was planning to leave work as promptly as possible so they could walk to The Plough together and find a table outside. It had been a shimmering day of unbroken sunshine, the pub would be packed even on a Wednesday. Afterwards they could try for a baby, she thought as she applied Tweed perfume to her wrists and neck. She had walked past Lauren’s bedroom and wondered if the weather was as lovely in St Ives for her. She resisted the temptation to sit on her daughter’s bed and absorb the scent of her, of her clothes, of her craft box. She’ll be home soon enough, she had thought to herself teasingly, and then the phone rang.

Karen began speaking in a slow, strangulated voice and then grew increasingly hysterical. Julian, who had been loitering guiltily outside the door, took over but by now Vera was deaf. It was panic deafness. She really could not hear a word after Karen mentioned a terrible accident.

Oh Vera, there’s been a terrible accident.

Vera’s throat became tight, she could feel it tighten now, and she had replaced the receiver without saying goodbye. She stood, paralysed, forgetting to breathe. There was a rap on the door and a voice through the letterbox.

‘It’s me, Monica Harper. Open the door and I’ll take care of everything, my dear.’

Vera inched slowly, not sure how to make her legs move, towards the voice of the poshest of her neighbours, who it seemed had been contacted by Julian.

Vera did not know Monica that well at all, only really seeing her at her annual Christmas party, but it transpired that she was calm and efficient and gentle and somehow bundled Vera and Bob onto a train, with overnight bags, to be met by Julian, whose eyes were so cloudy, guilty, hurt and red that both Vera and Bob knew instantly that their daughter was dead.

Everything, in fact, was dead. The friendship with Karen and Julian died. The innocence of Debbie died. Poor Debbie had stretched out to catch hold of Lauren but managed only to scratch her best friend’s arm. She would burst into tears in the middle of supper or the middle of class. She became the girl to be avoided.

Some people were kind, others avoided them. Bob’s boss, Peter Stanning, not only gave Bob unlimited time off, but frequently drove round after work with fruit and his wife’s homemade strawberry jam. Vera would stand at the upstairs windows glaring as the children of The Willows scampered and shrieked, threw balls and fell off scooters. Only Monica Harper would look up and smile at her and offer Vera a glimpse of life beyond bereavement.

Someone organised the funeral. It was not Bob and it was not Vera. Debbie cried the loudest and had to be ushered out of the church before the last hymn had been sung. Teachers said nice things about Lauren’s art and Aunt Suki said nice things about Lauren’s sweet nature.

Wreaths of flowers were knee-deep in places and the smell of them was pungent and cruel. The Harpers hosted the compulsory post-funeral gathering and even Vera could tell they did it faultlessly.

‘Without you…’ she said to Monica.

‘I know,’ Monica said, and kissed her on her forehead. Vera knew it was supposed to have been a healing kiss but the memory of it felt more like she was being given permission to leave behind the pain.

The day before Lauren’s second dead birthday Vera waited for Bob to leave and then began rummaging in the cupboard under the sink in the big bathroom. She had squirrelled away a stash of sleeping pills and paracetamol tablets and needed to get going fast.

She had been saving them ever since that first terrible day and the ring of the phone. It had been more important than eating, the hoarding of the pills. Monica’s kiss, the Stanning jam and the pills. They were all she had.

Vera had a jug of water to hand and a bottle of whisky. She had planned to swig them while stood at the sink but decided it might be easier to do it at her dressing table. She would be closer, then, to the bed. She counted in Laurens.

One Lauren and swallow. Two Lauren and swallow. Three Lauren and swallow.

When the room began to spin, she lay down with her pre-prepared ice-cold face towel to place on her forehead so she would not vomit and therefore survive. She carried on counting, carried on breathing and then, ever so slowly, stopped.

Bob was slightly later home than usual, wanting to leave everything squeakily efficient at work so he could concentrate on keeping Vera afloat the next day. It was breezy and orange and yellow leaves swirled in the bowels of The Willows as he placed his key in the door. It was quiet and he could not detect any signs of food being prepared. He shouted her name, climbed the stairs and as he reached the landing he smelled the whisky fumes. He paused, he couldn’t blame her. He badly wanted a drink too. He tapped lightly on the bedroom door before opening it.

He did not panic upon surveying the scene. Part of him was instantly envious. His wife had escaped the torment. He was not sufficiently calm, though, to take her pulse. He was loath to leave her to go downstairs to the phone so he opened the bedroom window. The curly-haired twins were throwing conkers at each other.

‘Hey!’ he shouted. They looked up. He asked them to knock on the Harpers’ door. They looked at each other quizzically before running off towards their own house. Exasperated, Bob ran down to the phone, made a call he later had no memory of making, left the front door open, then ran back to Vera.

Her face cloth had slipped onto the pillow leaving it wet as if soaked in her tears. He placed his head on her stomach, hoping she would reach down and run her fingers through his hair. When the ambulance crew arrived Vera’s blouse was damp too, and Bob, for the first time since his daughter died, was unable to stop sobbing.

Vera (#ulink_6dc3efb3-4bb2-5585-9a24-acdc961d6461)

Vera awoke in a panic. She had dreamed she had taken pills and it had been so vivid. She clutched at her flabby stomach but she felt fine, just disorientated. Bob walked in holding their baby.

‘I’m glad you were able to nap, love,’ he said, ‘but she needs a feed.’

Vera wriggled herself upright against the pillows. It was the most beautiful thing in the world to feed little Hope, and the most emotionally cruel. Hope had been conceived in a frenzy of desperate, angry, escapist lovemaking after the death of Lauren. She had promised herself she would kill herself if she could not have another child and she had doubted it would happen, but it had. The sibling had come along. She was too late to be a real sibling. But she was real.

She looked like Lauren but not too much for constant tears. Hope made everyone happy. Vera and Bob had asked Karen and Julian to be godparents and they had cried and cried and cried about it for days afterwards. Debbie ran endless, unnecessary errands for Vera. Aunt Suki had moved in for a fortnight to ease the load, which meant she made lots of tea and toast and answered the phone and the door and reluctantly pegged out washing.

‘Oh, Bob, I’m so grateful and so angry all at the same time,’ Vera said, ‘and I’m worried Hope will know, she will be scarred or withdrawn or frightened of me or something.’

‘Nah,’ said Bob, smiling. ‘She’s the most loved child in Cheshire and we’ll tell her about her big sister in the right way, of course we will.’

Hope needed to be loved. Her name had the ring of optimism but was drenched in tragedy. Her full name was Hope Lauren Pailing.

Hope’s christening was in the same church as…

That was how they all spoke of it. ‘It’s in the same church as…’ There was no need nor desire to finish the sentence. The service was intimate, and conducted at pace, as if those present were pushing against a great weight and they could only hold their arms aloft for so long to avoid being crushed.

There were more guests back at the house, where Vera was complimented on how slender she looked in her new dress. She even summoned a little twirl for Debbie, who was particularly entranced by the crêpe fabric that fell Hollywood style to reach the floor and the way ribbons of silvery silk were woven through it.

‘You look so lovely in your silvery silky dress,’ Debbie told Vera, in a low voice to avoid making her own mother jealous and she wondered why, when she said so, Vera had blinked rapidly.