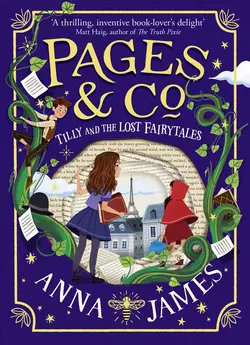

Pages & Co.: Tilly and the Lost Fairy Tales

Anna James

A magical adventure to delight the imagination. The curl-up-on-the-sofa snuggle of a series from a uniquely talented author. Tilly Pages is a bookwanderer; she can travel inside books, and even talk to the characters she meets there. But Tilly’s powers are put to the test when fairytales start leaking book magic and causing havoc... On a wintery visit to Paris, Tilly and her best friend Oskar bravely bookwander into the land of fairytales to find that characters are getting lost, stories are all mixed-up, and mysterious plot holes are opening without warning. Can Tilly work out who, or what, is behind the chaos so everyone gets their happily-ever-after? The second enthralling tale in the bestselling PAGES & CO series.

First published in Great Britain by HarperCollins Children’s Books in 2019

Published in this ebook edition in 2019

HarperCollins Children’s Books is a division of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd,

HarperCollins Publishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

The HarperCollins Children’s Books website address is

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

Text copyright © Anna James 2019

Illustrations copyright © Paola Escobar 2019

Cover design copyright © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2019

Anna James and Paola Escobar assert the moral right to be identified as the author and illustrator of the work respectively.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this ebook onscreen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008229900

Ebook Edition © September 2019 ISBN: 9780008229924

Version: 2019-08-07

For my mum and dad, who have always let me find my own path.

Contents

Cover (#u857759bc-1563-56c8-9fb2-1ad4d8d659ac)

Title Page (#uef322b27-8ef0-57e4-b1b4-cf75c5a513f0)

Copyright (#u2cb41500-6840-5a73-bcde-cc5334aaec3b)

Dedication (#u1da5cc70-e495-5448-b771-25c46511ae8d)

1. A Little Magic (#u50273d64-ffa8-54d5-b3fa-76a16d505477)

2. Fairy Tales are Funny Things (#u4519059a-76f9-503c-9082-2c53ce4d6ba9)

3. Slightly on the Outside (#u28205593-81e7-59ed-adf6-e266f370007a)

4. A Less-Than-Ideal Situation (#uff9c9431-39de-5b6f-99fb-3c017f6ea48e)

5. Something Strange is Afoot (#ube71fc93-8d6f-504a-91c0-b5f95da15201)

6. Riddles and Obfuscation (#ua311b1f9-7305-5502-86cf-215890a3a185)

7. Book Magic (#u8f63bdc7-fec6-562f-b2a3-95aafeed3a0f)

8. What an Adventure (#u180f6c57-3285-56f4-940a-75fced0d9622)

9. Something Wild and Beautiful (#u32a3548b-28e8-5921-8d99-654297defebe)

10. A Deep, Dark Forest (#litres_trial_promo)

11. What’s the Worst That Could Happen? (#litres_trial_promo)

12. Find Your Own Path (#litres_trial_promo)

13. What Great Teeth You Have (#litres_trial_promo)

14. Prince Charming at Your Service (#litres_trial_promo)

15. The Three Bears (#litres_trial_promo)

16. The Crack in the Sky (#litres_trial_promo)

17. I Need to Come Up With a Better Story (#litres_trial_promo)

18. There’s Never Only One Way Home (#litres_trial_promo)

19. Some Truth to Every Story (#litres_trial_promo)

20. It’s the Journey, Not the Destination (#litres_trial_promo)

21. A Book Will Welcome Any Reader (#litres_trial_promo)

22. A Plot Hole (#litres_trial_promo)

23. No One is Too Old For a Bedtime Story (#litres_trial_promo)

24. No Rules for Reading (#litres_trial_promo)

25. Whose Magic is it Anyway? (#litres_trial_promo)

26. Looking in the Wrong Places (#litres_trial_promo)

27. The Meaning of Life (#litres_trial_promo)

28. All Part of the Plan (#litres_trial_promo)

29. Evidence (#litres_trial_promo)

30. An Enemy of British Bookwandering (#litres_trial_promo)

31. The Crux of the Matter (#litres_trial_promo)

Epilogue: Three Months Later (#litres_trial_promo)

Once Upon a Time … (#litres_trial_promo)

French Glossary (#litres_trial_promo)

Acknowledgements (#litres_trial_promo)

Keep Reading … (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

(#ulink_da0c4ffd-0c34-57a0-89c8-c99dd092de43)

ive people proved to be far too many to fit inside a wardrobe.

‘Remind me again why we had to bookwander from in here?’ Tilly asked, face squished uncomfortably close to her grandad’s shoulder.

‘As I rather think you know,’ he replied, ‘we don’t technically have to bookwander from inside a wardrobe – but it adds effect, don’t you think?’ But he sounded decidedly less sure than when he’d first suggested the idea half an hour ago.

‘I mean, if the effect you’re going for is a much closer relationship with each other and our personal hygiene choices, then, yes, it does add effect,’ Oskar said, voice muffled by Grandma’s scarf, which was simultaneously tickling his nose and getting fluff in his mouth every time he spoke.

‘I bet the Pevensies didn’t have to deal with this,’ Tilly said.

‘Yes, but they were emptying straight out the other side of their wardrobe,’ Grandma said. ‘Which does rather give them an advantage.’

‘Yes, yes, okay,’ Grandad admitted. ‘It has become abundantly clear that my attempts at a little poetry and whimsy weren’t entirely thought through.’ He shuffled his way back towards the door and shoved it open. Tilly, her best friend Oskar, her two grandparents and her mother all fell gasping into the cinnamon-scented air of the bookshop.

‘I mean, it isn’t even a wardrobe,’ Oskar complained. ‘It’s a stock cupboard.’

‘Honestly,’ Grandad huffed. ‘I was just trying to add a sense of adventure. Mirror the journey into Narnia, have some fun. Goodness knows we could all do with a generous dollop of fun at the moment. A little magic.’

‘It’s already literally magic,’ Tilly pointed out.

‘I’m wasted on this family, I truly am,’ Grandad said. ‘Shall we try again from out here? We’ve still got an hour or so before we need to go to the Underlibrary for the Inking Ceremony.’

‘Actually, Dad, I think I might pass on this one,’ Tilly’s mum, Bea, said quietly, smoothing down her crumpled clothes. ‘The shop is so busy before Christmas, and I’m sure an extra pair of hands wouldn’t go amiss. You know how it is …’ She tailed off, smiled wanly, and headed out to Pages & Co., the bookshop the Pages family lived in and owned. Tilly sagged a little.

‘She hasn’t bookwandered once since we got back from A Little Princess,’ Tilly said, trying not to sound petulant.

‘I know, sweetheart, but try not to worry,’ Grandad said. ‘I’m sure she’ll get back into it soon enough. It’s no surprise after being trapped inside one story for nearly twelve years. Imagine how frightening that must have been for her.’ As always, when he thought about his daughter being imprisoned inside a tampered-with copy of A Little Princess, a look of distress swept across his face. ‘But we’ve got her back for good,’ he went on. ‘And now that we know Enoch Chalk was the one who trapped her, he won’t be able to get away with anything like that ever again.’

‘If he’s ever found,’ Tilly pointed out.

‘Did Amelia manage to find out anything about the book he escaped from before she was fired?’ Oskar asked.

‘Amelia wasn’t fired,’ Grandad said. ‘She was asked to step back from her position as Head Librarian at the Underlibrary, while the situation is investigated properly.’

‘I mean, that sounds a lot like getting fired to me,’ Oskar said under his breath.

‘And, in answer to your question: no, frustratingly not,’ Grandma said. ‘She barely had any time before the Bookbinders started poisoning the other librarians’ views about her capabilities. They’d been looking for a reason to get rid of her as soon as she was first given the job, and her handling of Chalk was merely an excuse. Those hardliners, with their silly self-important – not to mention self-appointed – name, blustering around pretending they were focused on anything other than their own power and influence.’ Grandad laid a hand on Grandma’s arm and she took a deep breath. ‘Sorry,’ she said. ‘Now is not the time, and here is not the place.’

‘Should I know who the Bookbinders are?’ Oskar said, and Tilly was glad, not for the first time, that he didn’t mind asking about what he didn’t know.

‘They are a nonsense!’ Grandad said. ‘A group of librarians who push for stricter rules and for more control for the Underlibrary over the lives of bookwanderers. They rallied around Chalk – although they must be red-faced now everyone knows he was a renegade Source character. But embarrassment often pushes people several more steps down the path towards hatred, and I worry that their championing of a colleague who proved to be fictional is fuel for their witch hunt for Amelia.’

‘A nonsense they may be,’ Grandma said. ‘But they’re bringing an alarming number of librarians over to their ways of thinking. People are worried about how the role of the Underlibrary is evolving, and fear is another thing that pulls people towards hatred.’

‘Aren’t the librarians worried about where Chalk is?’ Oskar said. ‘Isn’t it dangerous for him to be out there somewhere?’

‘I think they’re torn between concern about what he is up to, and wanting to sweep it under the carpet so the other Underlibraries don’t find out.’

‘The other Underlibraries?’ Oskar asked. ‘In other countries, you mean?’

‘Yes,’ Grandad said. ‘There are Underlibraries in most countries, although not all of them have Source Libraries. But I think that’s enough politics for now; we have a long afternoon ahead of us, which will likely be even more draining than an eternal winter ruled over by an evil queen. Let’s have something to eat.’

A lunch of scrambled eggs and sliced avocado on hot buttered bagels passed in tentative silence. Although they initially tried to maintain conversation, Grandma and Grandad were firmly inside their own heads, and a vague sense of impending doom hung over the table. The squeak of knives on plates and the sound of the dishwasher whirring in the background was all that could be heard for some time.

‘Is it really that bad?’ Oskar asked nervously, trying to break the silence. ‘I feel like we’re about to go to a funeral.’

‘Well, it’s certainly a funeral for our dear Amelia’s career,’ Grandad grumped. ‘Not to mention potentially the death of the future of British bookwandering as we know it.’

‘That does sound quite bad, then,’ Oskar said.

‘Come now, Archie,’ Grandma said. ‘Leaving aside our personal sadness for Amelia, this is not quite so dramatic as all of that. Bookwandering will continue, the British Underlibrary will continue. These things come in waves. You know that there was always going to be pushback against Amelia’s approach – those old-fashioned cronies were always angry that someone with more forward-facing ideas got the Librarian job when several of them had been hankering after it. Life will go on as usual, it always does.’

‘Until, of course, it doesn’t,’ Grandad said ominously. Grandma gave him a stern ‘not in front of the children’ look and he harrumphed, pushing his chair back with a squeal. He sullenly dumped his dirty plate by the sink, and turned to leave – before heading back sheepishly and washing it up carefully without making eye contact with anyone.

Once the rest of the lunch things had been cleared away, and everyone had checked for crumbs on their smart clothes, they traipsed out of Pages & Co., leaving Bea in charge for the afternoon.

‘Are you sure you two want to come?’ Grandad checked.

‘Yes,’ Oskar and Tilly chorused, not sure there’d ever be a bookwandering scenario that they would choose to miss out on.

‘I haven’t explicitly checked with the Underlibrary that you’re allowed,’ he said, as if that thought had just occurred to him. ‘But they’re hardly going to turn you away if you’re already there, are they?’ he concluded, more to himself than anyone else.

‘I know it’s sad for Amelia,’ Tilly said. ‘But I do want to see what happens when a new Librarian is chosen.’

‘You said there was a vote?’ Oskar asked.

‘Yes,’ Grandma said. ‘Anyone who wants to put themselves forward for the position can make their case, and then it’s up to the other librarians to choose who they think is most suited for the role.’

‘So you were voted for?’ Tilly asked her grandad.

‘He won over thirteen other candidates!’ Grandma said proudly.

‘How many are there this time?’ Oskar asked.

‘Only three, I believe,’ Grandma said. ‘It would seem the situation with Chalk has rather cooled some people’s ambitions. Who would want to be in charge of that mess? So I believe there’s Ebenezer Okparanta – who’s worked at the Underlibrary since time began as far as I know, and a woman, Catherine Caraway, who’s a bit of a wild card …’

‘And then there’s Melville Underwood,’ Grandad said. ‘He’s an interesting character. Disappeared for decades with his sister, Decima, not long after I started working at the Underlibrary, and no one thought we’d ever see them again. They used to run fairytale tours for bookwanderers, and all sorts can go on in those stories. But he emerged again a couple of weeks ago, completely out of the blue, and without his sister. I’m sure he’ll talk about his triumphant return in his speech, but he’s a bit untested for the job. I’d put money on them electing Ebenezer. He’s the safe bet, and I’m not sure this is the time for surprises.’

(#ulink_0d7f249c-5f79-5eba-a8fb-774fe66e653a)

randad had booked a taxi to King’s Cross, and the sleek black car waiting on the street outside the bookshop did not help with the funereal atmosphere.

‘You said one of the candidates used to run fairytale tours?’ Tilly asked, wondering about the unusual phrase her grandma had used. ‘What does that even mean?’

‘Well, fairy tales are funny things,’ Grandad said. ‘Do you know where they come from? Who wrote them?’

‘The Brothers … something?’ Oskar tried.

‘The Brothers Grimm,’ Tilly said authoritatively. ‘And Hans Christian Andersen. Lots of people.’

‘You’re right – but that’s not the whole story,’ Grandad said. ‘Those people did indeed write many fairy tales down, and put their own spin on them for sure, but they didn’t make up most of the stories themselves – they collected them. Fairy tales and folk tales are born around campfires and kitchen hearths, they’re whispered under blankets and stars. Where they really come from, who had the idea first, which version is the original, it’s almost impossible to trace as we only have what was written down, which is rarely where they started.’

‘And can you think about why that might make them more dangerous?’ Grandma asked.

‘Because …’ Tilly started confidently, but to her frustration couldn’t think of anything. Oskar sat deep in thought.

‘Is it something to do with Source Editions?’ he said. ‘Usually when something is dangerous in bookwandering, it’s to do with that.’

‘Yes, you’re getting warmer,’ Grandma said. ‘Keep going.’

‘If there’s lots of different versions …’ Tilly said.

‘… And we don’t know where they came from …’ Oskar continued.

‘… Then are there even Source Editions at all?’ Tilly finished.

‘Precisely,’ Grandad said. ‘We have Source Editions of many of the different versions of course, that act loosely like Sources, but these stories aren’t rooted in written-down storytelling. They come from oral storytelling, stories that are told out loud and passed down generations and around communities.’

‘And roots are what make things stable,’ Grandma went on. ‘Fairy tales are rooted in air and fire, not paper and ink, so the usual rules don’t apply. Layers of stories bleed or crash into each other and you can end up wandering into an entirely different version of the story with little way of getting out. It’s incredibly dangerous to try and wander from inside one story to another; it’s like trying to find a route on a map but you don’t know where you’re starting from. Not to mention, fables fade in and out of existence; we tell new versions and we lose old ones. So they’re seen as a bit of a risk for bookwandering. Sometimes the Underlibrary would organise group visits led by someone who was a bit more comfortable there, and understood the risks and what to do to stay safe – or try to stay safe.’

‘Have you been inside any fairy tales? Can you take us?’ Tilly asked. Her grandparents exchanged a look and she couldn’t help but wish they weren’t quite so good at communicating without speaking. She wondered if she would ever be a team like that with someone and experimented by glaring at Oskar meaningfully.

‘Are … are you okay?’ he asked nervously. ‘You look like you need to sneeze.’

‘Never mind,’ she said, blushing and turning back to Grandma and Grandad. ‘You didn’t answer my question.’

‘Actually, your grandma is one of the few bookwanderers who does bookwander in fairy tales officially and safely,’ Grandad said, looking at her proudly.

‘How come?’ Oskar said.

‘Well, as you both know, I used to work in the Map Room at the Underlibrary,’ Grandma said. ‘And as well as looking after the plans of real-life bookshops and libraries, it was also part of my job to know as much as I could about the layout of stories themselves. I did a bit of fairytale exploring back in the day, but that project was abandoned after … Well, after a difference of opinion, let’s say.’

Tilly thought about her grandma, who always took everything in her stride, and was intrigued. ‘There’s got to be more to that story?’ she pushed.

‘But it will have to be told another time,’ Grandad said. ‘We’re here.’

(#ulink_695c3fe2-4b69-56ad-9f98-9aa2b980b4c7)

o Tilly’s eyes, the steady stream of people in matching navy-blue cardigans weren’t doing a very good job of being inconspicuous inside the British Library. But despite the co-ordinated clothing and loud whispering, they didn’t seem to be attracting much attention from the regular library users.

‘They’ll assume it’s a tour group,’ Grandad said as they walked through the ‘Staff Only’ door that led inside the King’s Library, a glass-wrapped tower of books in the middle of the main hall. ‘People are good at not noticing things that don’t affect them. How do you think we’ve hidden a magical library here for decades?’

There was a queue to access the seemingly out-of-order lift that carried bookwanderers down from the main library and into the British Underlibrary. Tilly had expected the mood to be sombre, as it had been at Pages & Co., but there was a disconcerting buzz in the air, and lots of excited faces in the crowd.

‘Aren’t we supposed to be sad?’ Oskar whispered to Tilly.

‘We are,’ Tilly said, ‘because Amelia is our friend, but I guess lots of people are cross with her for keeping what she knew about Chalk a secret.’

‘We are … on the right side, yes?’ Oskar said.

‘Side of what?’ Tilly asked.

‘Whatever this is,’ Oskar said. ‘Because it is clearly something.’ And although Tilly was loath to admit it to herself, she had to accept that Oskar was right. A now-familiar panic rose in Tilly’s chest. The feeling of belonging and acceptance she’d experienced when she first found out she was a bookwanderer had been ripped away when she discovered that she was half-fictional. She was of their world and yet removed from it, and sometimes felt like one of those children she’d read about in novels, who were forced to live inside a plastic bubble because they were sick and couldn’t risk contamination – as though she had to keep parts of herself hidden and protected. And now there were all these complicated Underlibrary politics she couldn’t quite grasp, and there was a tiny voice in the back of her head asking whether everything would be easier if she’d never found out she was a bookwanderer at all. Who wanted to be special anyway? All it seemed to mean was secrets, suspicious looks, and a feeling of always being slightly on the outside.

Despite this, and the strange atmosphere crackling in the Underlibrary, Tilly couldn’t help but feel a sudden rush of wonder at the sight of the beautiful main hall that stretched high above her head, with its turquoise ceiling and sweeping wooden arches. A librarian rushed over to them and shook Grandad’s hand vigorously.

‘Seb!’ Oskar said happily, recognising the librarian who had helped them learn how to bookwander a few months ago.

‘How are you all? Mr Pages, sir, Ms Pages, lovely to see you,’ Seb said. ‘Tilly, Oskar.’ He was speaking incredibly quickly, unable to stop himself being polite, despite clearly having something very important to say. ‘If you wouldn’t mind following me, Amelia’s waiting for you.’ He shepherded the four of them off into an anteroom, keeping an eye on who was watching them go. The room he took them to was lined with bookshelves and warmed by a large fire, and pacing in front of it was Amelia Whisper, the former Head Librarian, her long black hair pinned up into a formal hairstyle that robbed her of some of her usual warmth. Her skin, usually a glowing brown, looked paler and duller than normal. She nodded her head to them as they came in.

‘Thank you for coming,’ she said.

‘Of course, Amelia,’ Grandma said, rushing across the room and trying to wrap her in a hug, which Amelia stopped with a firm hand.

‘Don’t be too kind to me,’ Amelia said. ‘You’ll make me cry, which is not very on brand for me at all. And I need to talk to you about something much more important than me and my feelings. Seb and I are worried about what’s going on here.’

‘Well, we all are,’ Grandad said. ‘Honestly, insisting you stand down, listening to these cliques and their hare-brained ideas.’

‘No, I mean something more than that,’ Amelia said. ‘Yes, I’m heartbroken that the Underlibrary is choosing to replace me, but, well, they’re within their rights to do so.’

‘Just,’ Grandad muttered.

‘But the issue is who they’re replacing me with. Or trying to.’

‘What do you mean?’ Grandma asked.

‘I don’t trust Melville Underwood at all, and I think there’s more to his story than he’s letting on.’

‘Ah, but they won’t go for him, surely,’ Grandad said. ‘He’s just got back from goodness knows where. No one knows anything about him. It’ll be old Ebenezer.’

‘I’m not so sure,’ Amelia said. ‘You haven’t been here over the last week; Melville may have just got back but he’s been darting around the Library whispering in people’s ears and I’m worried about what he’s saying, and what people are open to believing. I don’t think it’s a coincidence that the Bookbinders have stopped grumbling from the sidelines and started to get more organised.’

‘If I could be permitted to chip in,’ Seb said. ‘I am a little concerned about where he has been all this time, as you say, Mr Pages – but others don’t share our reticence. The Bookbinders, as they insist on calling themselves now, are lapping up Melville’s tale because they are happy to gloss over all sorts of irregularities if it means having one of their own in charge. Ideologically, I mean. Better the devil you sort-of-know, and all that. But while he claims that he and his sister were attacked while leading a bookwandering group through a collection of fairy tales, there are no records of this attack happening. If a group of bookwanderers were attacked or lost there should be some note or diary or even personal memory, somewhere in our records. He says he can’t be sure what happened to the rest of the group, or his sister, and no one seems to be pushing him on it. Something smells fishy to me.’

‘But there’s no proof?’ Grandad said slowly.

‘Well, no,’ Seb said. ‘The lack of evidence or proof is just the issue. There’s no way to corroborate his story. We’re a group of librarians and archivists and storytellers; why aren’t we more concerned that there’s no record …?’

‘I do worry that unfounded claims such as these will merely make us look like sore losers, especially today,’ Grandad said slowly. ‘Is there wisdom in waiting and watching for a while, do you think? I must admit, I never warmed to Melville when I crossed paths with him back when we were both young men here.’

‘That’s the other thing,’ Amelia said. ‘He’s still a young man.’

‘Well, that’s nothing of note in itself,’ Grandma said. ‘Ageing works erratically in books as it is, and if he was in fairy tales then even more so.’

‘Yes, but he doesn’t seem to have aged a day,’ Amelia said. ‘He still looks to be in his late twenties.’

‘My dear Amelia, it’s easy to find evidence of what we already believe …’

Amelia brushed Grandad’s reassuring hand off her arm.

‘Don’t you dare patronise me, Archie,’ she said. ‘I am not some conspiracy theorist, I know the Underlibrary of today better than you do. I understand that we are dealing with little more than smoke and whispers and instincts here.’

‘You know what they say about no smoke without fire,’ Seb said sagely.

Amelia ignored him. ‘There is something else happening here,’ she said firmly, ‘and you would be wise to take my warning seriously.’

Grandad nodded, chastened. ‘You’re right,’ he said. ‘I’m sorry, I didn’t mean to … I just, well, Elsie and I both care for you greatly as our friend and colleague and I don’t want to see you get hurt more than necessary.’

‘The hurt is already inflicted,’ Amelia said, steely-eyed. ‘And I can endure it. But I want it to be worth something, and it is time for some answers. Do you know, in recent weeks I have found myself wondering if I was ever really quite cut out for being in charge? Do you think I’d make a good rebel? I’m interested to see if I’ve got it in me.’ There was a definite twinkle in her eye. ‘Now, if only I can convince Seb to start disobeying some rules …’

‘One step at a time,’ Seb said, breaking out in a light sweat at the mere thought.

(#ulink_8eaf59ab-b81a-5d27-bd80-b40cd8a3ed8d)

eb led them back to the main hall. A table and a microphone had been set up on a sturdy platform at one end of the hall, and rows of chairs faced it. On top of the table was an enormous book bound in ruby-red leather beside an old-fashioned ink pot complete with a feathered quill. Librarians had nearly filled up the rows, but Seb ushered Grandad, Grandma, Tilly and Oskar to reserved seats near the front. As they sat down, Tilly couldn’t help but notice the way everyone turned to look at them, undisguised suspicion on many faces. Was it her or her grandparents who were attracting such distrust? Or all of them?

‘Considering our part in the whole Enoch Chalk debacle, I’m surprised we’re up here at the front,’ Grandad whispered.

‘All the better to keep an eye on us, I’m sure,’ Grandma said.

‘You know how it is,’ Seb said. ‘Tradition always wins out, and tradition states that any living former Librarians are guests of honour at Inking Ceremonies. And I imagine that if you don’t bring Chalk up, no one else will. People are happy to let Amelia take the fall for this; it’s easier to blame one person than to think about what’s really happening.’

Tilly was distracted from people’s suspicious glares when she noticed a young man emerge and stand just behind the platform, eyes closed, talking to himself under his breath. He had neat, white-blond hair and was wearing a navy-blue suit, with a librarian cardigan underneath the jacket. He looked very focused and Tilly could only assume it was Melville Underwood, the man that Amelia and Seb were so wary of. Behind him, talking to each other amiably, were a very old man with a silvery beard that curled its way down to his shins, and a middle-aged woman in a wheelchair wearing all black. As Tilly watched, a librarian came up behind Melville, and startled him out of his meditations with a tap to the shoulder. She spoke quietly to him, gesturing at the microphone, and Tilly saw a flash of irritation cross his face, quickly replaced by a polished warm smile. She nudged Grandad.

‘That’s him, isn’t it?’ she asked.

Grandad looked up and nodded. ‘And the man with the beard is Ebenezer, and the woman is Catherine,’ he said, as the three candidates and Amelia came and sat facing the audience. Amelia kept her head held high, her brow furrowed.

The crowd hushed as one, as if responding to an invisible signal, and only the occasional creak of a wooden chair echoed through the hall. A man who looked like he worked in a bank rather than a magical library climbed the steps on to the platform and tapped the microphone hesitantly, causing a shriek of feedback to bounce around the room. The audience grimaced, and the man blushed.

‘That’s Cassius McCray,’ Grandad whispered to Tilly and Oskar. ‘Chief Secretary of the Underlibrary.’

Cassius didn’t apologise, just glared at the microphone as though it was personally trying to undermine him. He cleared his throat.

‘Right,’ he started. ‘Well, we are gathered here today for the Inking Ceremony. This is a slightly unusual situation due to the, uh, circumstances. As you all know, our former colleague Enoch Chalk was revealed to be a, well, a fictional character from a Source Edition. He had been working here undetected for decades, trapping anyone who discovered him in books that he had tampered with. It was a … a less-than-ideal situation. Ms Whisper, our former Head Librarian, had her suspicions about his true nature and decided not to share them with us, her colleagues. We believe that decision makes her, well, unsuitable for that esteemed role, and she has been relieved of her duties. We thank Ms Whisper for her service to the British Underlibrary, and we have offered her another, more suitable, position here should she wish to remain and make amends by helping us discover the whereabouts of Mr Chalk. That investigation is ongoing, and we are confident it will be resolved satisfactorily. We will, of course, keep you updated. As is our duty.’

Throughout this, Amelia kept her chin in the air with no trace of penitence on her face. Tilly felt as though she wanted to applaud her, or run up and hug her, or do anything at all to show her she was on Amelia’s side. And there it was again in her head: the idea of sides, and of having to be on one.

‘Well,’ Cassius continued. ‘This of course means we must elect a new Librarian, and we have had three, uh, yes, three, candidates put themselves forward, and despite their, shall we say, current status, it is in our statutes that anyone who is eligible may speak to us. So, we will hear from all three and there will be the opportunity to put questions to them and then, as is tradition, we will have a private ballot to determine Ms Whisper’s successor. So, uh, shall we start with our dear friend Ebenezer Okparanta …?’ A librarian behind him coughed and Cassius corrected himself. ‘I mean, our colleague Ebenezer Okparanta.’

The old man with the long silvery beard took to the stage, a warm smile on his face.

‘My friends,’ he began. ‘For we are all dear friends here. I stand before you an old man, but one who wishes to unite us all under the principles we hold so dear. We are in a time of confusion and tumult, but it needn’t continue. We care for a magical and important thing here, and we are being distracted from our purpose by in-fighting and egos. We must continue our work to prevent the closure of bookshops and libraries while also working to protect ourselves and our community – two goals which can be achieved in harmony. I believe, at this juncture, my long past here at the Underlibrary and proven dedication to our goals make me the steady hand we need to steer us through this time. I have worked with you all for many years, and I hope that my experience speaks for itself. Thank you, friends.’

‘Any questions?’ Cassius said, and hands sprang up.

‘Ebenezer, what are you going to do about Enoch Chalk?’ a voice said.

‘I shall, of course, be working with Amelia to find out where he has gone, and—’

‘But,’ interrupted the voice, ‘I think, or rather I know, there are others here who believe that librarians should be tested to ensure we are all who we say we are.’

‘Why, no,’ Ebenezer said, sounding surprised. ‘I haven’t heard that. What do we have without trust in each other?’

‘Look where that’s got us,’ another voice said in a stage whisper, and Ebenezer started to look slightly flummoxed.

‘Enoch needs to be dealt with, of course, my friends, but there are bigger things at play,’ he said. ‘The waning of book magic as bookshops and libraries close, the erratic readings we’re getting from fairy tales.’

‘Let’s hear from Melville Underwood!’ a woman cried. ‘He’s been inside the fairy tales after all!’

‘Now, now,’ Cassius said. ‘It’s Catherine’s turn next. Let’s just leave it there with Ebenezer.’

Ebenezer walked off stage a little wobbily, clearly taken aback by the mood in the room, and was replaced by the woman wheeling herself up the ramp on to the stage.

‘That’s Catherine Caraway,’ Grandma whispered.

‘Fellow bookwanderers,’ Catherine said, sounding confident and warm. ‘For too long we have neglected our primary reason for existence and have been mired in bureaucracy. I want to lead an Underlibrary that is focused on bookwandering. What we need to do is contact the Archivists.’ Tilly could hear tutting spread through the room, and even a few derisive laughs. ‘We have abandoned them for too long,’ Catherine went on, her voice building in volume. ‘Why are we so surprised they have forsaken us? Let us give our problems to them to resolve, and get back to our true purpose.’

Tilly glanced at her grandparents and saw that they both looked deeply uncomfortable, as though Catherine had suggested enlisting the Easter Bunny to help.

‘Who would you choose?’ Tilly whispered to Grandma.

‘Leaving aside the obvious fact that Amelia is considerably more suitable than any of them,’ she said quietly, ‘Ebenezer’s heart is in the right place, I am sure, but I worry he doesn’t have the strength to cope with rebel voices here. And goodness knows what Catherine is talking about. She’s showing her naivety …’

‘But couldn’t the Archivists help?’ Tilly said. ‘I thought they were, like, the most important bookwanderers?’

‘Trusting in the Archivists is like relying on a unicorn to come and grant you wishes to solve your problems,’ Grandma replied.

‘Maybe Melville will be better?’ Tilly whispered, stealing another glance at the man who was watching Catherine field increasingly angry questions with a look of sincere polite interest on his face.

‘We shall see,’ Grandma said, and then they were shushed by someone sitting behind them.

Catherine wheeled her chair down from the stage and Cassius took the microphone again, looking very unsettled. Amelia tried – and failed – to keep a slightly smug expression off her face.

‘Right, well,’ Cassius spluttered. ‘Let’s just remember we’re all colleagues, shall we? So, where were we … Yes, well, finally, we have our rather last-minute candidate. A long-lost wanderer has unexpectedly returned to us and has put himself forward, which he is absolutely permitted to do. Some of you who have been here a while will remember our colleagues Melville and Decima Underwood, who were bookwanderers in the field, putting their own lives on the line to explore the limits of our stories in fairy tales. When they vanished without a trace we believed they had made, well, the ultimate sacrifice for their work in some of our most dangerous stories. But … a miracle has occurred, and we are encouraged by the return of Mr Melville Underwood.’

Cassius climbed down from the platform, and Melville Underwood took to the stage. The silence in the room was absolute and Tilly found herself leaning forward, eager to hear what he would say.

‘My friends,’ Melville started. His voice sounded as though it had been dipped in honey. ‘I am so grateful to have found my way back to you. I have endured years balancing on the brink of survival in the fairytale worlds, alone in my grief for my poor sister, Decima. The thought of coming home, to my British Underlibrary family, has sustained me. Although I have come close to the most dangerous elements of bookwandering, my experiences have not diminished my love for it. Indeed, they have, if anything, deepened my respect and awe for the bookwandering magic we are so fortunate to use. But that magic is by no means guaranteed, and I have witnessed first hand, and learned from my esteemed friends here, that there are signs that this precious magic is becoming unpredictable. At this time, we need to band together and protect bookwandering while we still can.’ He looked around the room, assessing how his words were going down, his eyes lingering just a second too long as he noticed Grandma and Grandad.

‘British bookwandering has long been at the heart of the whole global community, and we must keep it this way,’ he continued. ‘Now that the fairytale lands are increasingly unstable, I fear whatever is causing that will spread to our other stories. We must be vigilant! I, as we all should be, am grateful to Amelia for her work leading our community for the last decade, but the time has come for a different approach. We simply cannot allow incidents like the Enoch Chalk disaster to happen. It has threatened the very principles by which we live. I would ask us to unite! Unite in the face of instability and threats to the power and sanctity of our stories – and the British Underlibrary itself. I agree with both of my esteemed colleagues; Ebenezer is right that we must come together, and Catherine raises important points about our core purpose. I am grounded in both these principles, but I hope that my time in the fairytale lands – on the front line of our storytelling – has given me the clarity and purpose needed at this moment in our history. We have such wisdom and experience among our fellow British Underlibrarians. As well as Ebenezer and Catherine, I understand that while I have been away, some of our colleagues have been diligent in their research into the best ways to preserve and protect bookwandering under the ancestral name of the Bookbinders. If I were so fortunate as to be elected, I would be honoured to work alongside them, and you all, to unite us on the most effective and efficient ways of ensuring characters – and bookwanderers – are less likely to go astray!’ He smiled to the crowd, like they were all in on the same joke. ‘Now, I’ll be happy to answer any questions you may have,’ he finished. ‘And I appreciate you will have many.’ A round of polite, appreciative applause rippled across the hall, and Tilly saw a flicker of anxiety run across Amelia’s face.

‘Thank you, friends,’ Melville said graciously.

Grandad raised his hand.

‘Tell me, Melville. Why are you the right person to lead now?’ he said. ‘When you have not been with us for so many years? Could you not stay, and learn, and observe, and look to take the helm in the future?’ Grandad’s voice was ice-cold, despite the politeness of his words.

‘Well, Archibald,’ Melville said, smiling at Grandad, ‘I believe that I can offer much to the Underlibrary, as I have just set out. But there is one other thing, something that I had not planned to mention, as it should not have any bearing on the election here today. But as you have forced my hand, Archibald, and in answer to your excellent question, let me share something with you now. I come to you not just armed with information about how we can save our beloved fairy tales, but also with incontrovertible evidence as to the whereabouts of Enoch Chalk.’

(#ulink_7b7f80a3-6707-5232-b108-8ce833ce386b)

here was a second of absolute silence, before the room erupted into chaos. People were gesturing wildly and shouting over each other. Melville simply surveyed the crowd with a look of complete calm on his face. Tilly felt cold all over and saw Grandma and Grandad exchange ominous looks.

‘Now, see here,’ Cassius spluttered into the microphone. ‘That’s quite a thing to claim, Melville. What do you know? You are obliged to share it with us, you must see that!’

‘Of course,’ Melville said, quietening the crowd with one hand raised. ‘I did not want to sway the feelings of my colleagues at this delicate point, that is the only reason I did not mention it before. But I am eager to share what I have learned with you all. While on my travels searching for a way back from the fairytale lands, I happened across several characters complaining of a man being discourteous, and poking around, asking questions. I attempted to find him myself, assuming he was a bookwanderer and seeking a way home.’

‘What proof do you have?’ a voice from the back called.

‘Will you permit me a moment?’ Melville asked Cassius, who nodded helplessly as Melville slipped off stage and returned a few moments later with a cardboard box in his hand. The tension in the air was electric as he set the box down on the desk.

‘Will this suffice as proof?’ And with one hand he pulled out a grey bowler hat that was unmistakably Enoch Chalk’s.

A brief pause hung in the air, and then the majority of the audience started applauding loudly. Amelia raised an eyebrow at Grandad.

‘Isn’t that a good thing?’ Tilly whispered to Grandma, confused. ‘I thought we wanted to find Chalk. Doesn’t that prove Mr Underwood is on our side?’

‘Perhaps,’ Grandma said. ‘But perhaps not. I don’t trust Melville, but I do trust Amelia’s instincts. There are many questions unanswered – how would Melville know Chalk was a threat in the first place? And we – of course – want Chalk found and dealt with, and we may align with Melville on other things too. Who knows. The one thing I am sure of is that something strange is afoot.’

Cassius was back on stage, trying to calm everyone down again.

‘I think … I think the only thing we can do now is vote,’ he said. ‘We will invite you up a row at a time to cast your ballot, so please return to your chairs until you’re called, and well, we shall go from there. Current employees of the Underlibrary only,’ he said, looking directly at Grandad, who rolled his eyes. There was a lot of hushed conversation as, row by row, nearly fifty librarians filed up to the front, marked a piece of paper, and posted it through a large wooden casket, all under Cassius’s flustered glare. Once everyone had voted, Cassius and another librarian carried the ballot box out of the hall. Half an hour later, Cassius returned, looking slightly pale.

‘We have counted and verified – more than once – the votes, and I am, well, I am happy, yes, to announce that the next Librarian of the British Underlibrary will be Melville Underwood.’

There was thunderous applause as the name was announced, although as Tilly craned her neck, she could see small pockets of librarians who weren’t clapping at all. But the mood was undeniably in Melville’s favour, and he approached the stage once more, still clutching Chalk’s hat in his hand.

‘I look forward to working for you,’ he said, bowing his head reverently as the applause washed over him. Once it had died down a little, Cassius approached, and Melville took off his suit jacket, and rolled up his cardigan and shirt sleeves. A librarian had opened the book, and smoothed the pages down reverently.

‘So he just signs his name now and he’s the Head Librarian?’ Tilly asked.

‘There’s a little more commitment than that required,’ Grandad said. ‘You guys aren’t squeamish, right?’

‘Nope,’ Oskar said, craning to make sure he had a good view. Cassius stepped forward and looked at Melville, who gave a firm nod and held out his hand for the quill.

‘The ink of the Underlibrary represents our stories, which are now part of you,’ Cassius said formally. He took Melville’s wrist and held his fingers over the ink pot before quickly and firmly pricking his finger with the quill, and letting a drop of blood fall into the ink below. Tilly was watching Melville’s face, and he swallowed but didn’t make a sound. ‘And by giving a drop of your blood, you are now part of the Underlibrary,’ Cassius continued, handing Melville the quill, which he dipped into the ink before signing the great book on the table. ‘With this Inking Ceremony, the lifeblood of both you and the Underlibrary are one and the same.’ Cassius shook Melville’s other hand, and Melville’s face broke into a wide, warm smile. He pulled Cassius into a one-sided embrace, breaking the solemn mood of the moment.

‘Was that it?’ Oskar said, sounding a little disappointed.

‘Did Amelia have to do that?’ Tilly asked Grandma.

‘Why, yes,’ she said. ‘And your grandad too, of course.’ Grandad smiled and held up the ring finger on his right hand, where a tiny, faded black dot was visible.

‘Isn’t that dangerous?’ Tilly asked. ‘Won’t you get, like, ink-poisoned or something by it?’

‘Oh no,’ Grandma said. ‘It’s just like getting a tiny tattoo, really.’

‘And I seem to be doing all right so far,’ Grandad said, smiling and absent-mindedly rubbing the pad of his finger where the tiny mark was. ‘Now, let’s get out of here before we have to make any awkward small talk. I could use a cup of tea.’

‘Not so fast,’ a voice cut in. They turned to see Cassius standing by their seats. ‘Melville would like to have a word. With all of you.’

(#ulink_3c96ad1b-1c54-5c6d-88d6-3e98c72a18e0)

he group followed Cassius back into the room where they had been talking before the ceremony. The fire had been stoked into a roaring blaze and the room was stiflingly hot. Seb, who was sticking to them like toffee, followed silently and closed the door behind them. The only person who still looked fresh and comfortable was Melville Underwood, who was sitting in a leather armchair right in front of the fire, a neat plaster wrapped round the tip of his finger. The charming man who had spoken at the Inking Ceremony had evaporated and his face was stern as he observed them.

‘Good to see you again, Melville,’ Grandad said in the voice he used when he meant precisely the opposite of the words coming out his mouth. ‘How on earth have you got Chalk’s hat? You claim a moment of heroism, yet surely when you met him you had no idea who he was? There’s no need for secrets at this stage. We’re all on the same side, right?’

‘I have a few orders of business to get through,’ Melville said, ignoring Grandad. ‘Firstly, while you have been invited here as a courtesy to your previous role, Archibald, you and your family are no longer welcome at the British Underlibrary except in cases of extreme bookwandering emergencies or at my personal invitation.’

‘You can’t do that!’ Oskar said, outraged. ‘Can you?’

‘Who are you?’ Melville said as if he had just noticed Oskar.

‘I’m Oskar, obviously, and you should know who I am because I helped rescue Tilly’s mum last year and find out the truth about Chalk.’

‘Ah, you were the other child who allowed him to escape through your meddling,’ Melville said coldly. ‘Of course there is no need to worry about that any more. We will be bringing him to justice shortly.’

‘So where is he?’ Tilly asked.

‘That is none of your concern,’ Melville said dismissively. ‘Why two children have already become so involved in this issue is beyond me. Your inability to see the big picture, let alone put it before your own personal vendettas and childish desire for adventure, is what’s got us here, with this dangerous man on the loose.’

‘Good grief, Underwood,’ Grandad said. ‘You know it’s not their fault – beneath all your posturing, you can’t get away from the fact that without Tilly and Oskar none of us would have realised that Chalk was an escaped Source character. Now, will you tell us why you have the man’s hat? This is no time for riddles and obfuscation.’

‘That’s the second time in mere hours that I’ve had to repeat myself to you. You must try and be a better listener, Archibald,’ Melville responded icily. ‘As I said, I was aided by characters in the fairytale land. As I searched for a way out I had heard rumours about a man asking questions, and I assumed he was an errant bookwanderer. I hoped I would be able to wander back to the real world with him. But when I found him, he was instantly combative and refused to talk to me, just muttered on and on about some nonsense I couldn’t understand. Once I’d realised he wasn’t in his right mind, I distracted him and slipped a book out from his pocket to ensure my escape route. Naturally I attempted to bring him with me but he resisted, and ran away, leaving only his hat on the ground. I picked it up in the hopes of identifying him when I’d found my way home. And once back in the Underlibrary, I was quickly able to work out who I had encountered. It also put his mutterings about a child who had ruined his plans into context.’

Melville looked at Tilly. ‘Which brings me to the next item on my agenda. I have become increasingly concerned about the effects that children have on the security of bookwandering. The exploits of your granddaughter – and her friend – do nothing to change my mind. I plan to limit bookwandering for under-eighteens until they can learn discipline, not to mention learn the history and traditions of our great institution.’

‘You can’t stop us bookwandering!’ Tilly said in horror.

‘That’s barbaric,’ Grandma said. ‘Why would you want to cut children off from the magic and wonder of bookwandering?’

‘Because they do not have enough respect for the rules, and because bookwandering is about more than magic and wonder,’ he said, managing to imbue those words with pure disdain.

‘Anyway, regardless of your shoddy logic, it’s not possible to stop someone bookwandering,’ Grandad said. ‘As you well know.’

‘We may not be able to stifle someone’s natural ability,’ Melville said calmly. ‘But we can certainly bind the books here at the Underlibrary and restrict access.’

‘But a book doesn’t know how old a reader or wanderer is,’ Grandad said. ‘There’s no way of putting an age limit on it.’

‘You’re right,’ Melville said. ‘So I imagine we shall have to bind the books for everyone and require people to file written permission to access them for bookwandering purposes. That’s a neat solution, don’t you think? We can ensure people are only bookwandering with valid reasons, not merely for a jaunt, or to cause mischief. Or indeed to seduce a fictional character.’ He raised an eyebrow.

‘How dare you make such crass implications about my daughter?’ Grandma said, and Tilly felt her hands squeeze involuntarily into fists, her fingernails pushing painfully into her palms.

‘That’s not fair!’ Tilly burst out. ‘That’s not what happened at all!’

‘I suggest you control yourself,’ Melville said. ‘Your outburst only supports my position.’

‘Do you know, you sound an awful lot like Enoch Chalk?’ Grandma said coldly, and Melville let annoyance cross his face for a moment.

‘I can assure you that I am the very opposite,’ Melville said. ‘Not that I have to justify myself to you. As you saw just minutes ago, the librarians are on my side. And one more thing. For the meantime, I think it’s probably wise to introduce a period of stamping, so we can keep track of everyone’s whereabouts.’

‘But that’s a gross invasion of privacy,’ Grandma said, and Tilly felt cold all over at the memory of Chalk stamping her without her knowledge so he could try to find out who her parents were.

‘Anyway, no one will agree,’ Grandad said. ‘Everyone will opt out.’

‘On the contrary, it’s already been agreed. It’s now mandatory to opt in.’

‘Mandatory opt-in?’ Grandad snorted. ‘A complete oxymoron. You can’t just change the meanings of words at your own will.’

‘On the contrary,’ Melville said. ‘Words can mean much more, or less, than they seem, and we can put them to such creative uses. The majority of our librarians understand, or are being made to understand, that stamping is for the best at this time of uncertainty. After all, if you’re not going anywhere you’re not supposed to, you shouldn’t have any concerns, should you? It would look awfully suspicious if you didn’t want your fellow bookwanderers to know where you were going. And before you get on your high horse, remember stamping only traces which books you’re travelling inside. No one will be watching your every move in your day-to-day life, or anything sinister like that. Come now, we’re librarians after all. Seb will take you to be registered. Thank you for your co-operation. It’s an exciting time for British bookwandering. You are honoured to be witnessing it.’

‘Hang on—’ Oskar started to say, but Melville interrupted him.

‘That’s all for now. Thank you for your time.’

‘You won’t get away with this,’ Grandad said to Melville.

‘And yet, I seem to be doing just that,’ Melville said, not looking up.

(#ulink_dd47dff1-13fb-58e5-9482-94c8ce71f7d1)

s soon as the door was closed behind them Grandad went to speak, but Seb glared at him and put a finger to his own lips.

‘Wait until we’re somewhere private,’ he whispered urgently, and so they walked in a silent line into another office, this one much more sparsely decorated than the last.

‘I refuse to be stamped!’ Grandad said, as soon as the door was closed. ‘It’s an obvious and egregious infringement of my rights as a person and a bookwanderer. The Underlibrary has no legal right to do anything to us.’

‘No, of course not,’ Seb said. ‘But it does have powers over bookwandering, and it is within its rights – if on dubious ethical grounds – to say, for example, that only stamped bookwanderers are permitted to wander within books under the jurisdiction of the British Underlibrary. You know a stamp isn’t permanent – Tilly isn’t still stamped from when Chalk was following her.’ Tilly shuddered at the memory.

‘Come on, Seb, you don’t need to do this,’ Grandma said.

‘I would never even think of it,’ Seb said, affronted. ‘But it’s not me that’s doing it. I only found out this was the plan during the Inking Ceremony when my friend Willow warned me. Amelia thinks that I should ingratiate myself with Melville, so I can report back. But I don’t think he’s convinced of my allegiance yet, and he’s sending along someone else to do the stamping so I can’t sneak you out. The only thing that I can think of is to—’ At that moment the door banged open and a petite woman walked in.

‘I’ll take over from here, Sebastian,’ she said formally.

‘Of course, Angelica,’ he said. ‘I’ll just take Tilly and Oskar next door.’

‘Why?’ she said, frowning.

‘Didn’t Mr Underwood tell you? Because of his new guidelines for child bookwanderers, they’re being stamped by Willow a few doors down, so there’s a separate record for under-eighteens. Surely … Melville told you, didn’t he? How embarrassing if I’ve spilled the beans before I was supposed to.’

‘Of course not,’ Angelica said, blustering. ‘I knew that – I was just checking you did. I’m actually rather in the inner circle nowadays,’ she said, smiling smugly.

‘Yes, yes,’ Seb said, ushering Tilly and Oskar out of the door. ‘Well done, very important I’m sure. I’ll take them in. How long do you need?’

‘Only ten minutes or so,’ she said.

‘What about Grandma and Grandad?’ Tilly hissed at him, as Seb shoved her and Oskar into an empty room.

‘I am sure they will think of something,’ he said. ‘If it came down to it, I’m sure they would prefer to make sure you don’t get stamped. They’re more than capable of fending for themselves.’

‘Can Underwood check if we’ve been stamped, though?’ Oskar asked Seb nervously.

‘Well, he can check the record, yes,’ Seb said. ‘And I will duly be writing your names down so they appear to be there. And if he checks the stamp to see where you’ve been then it won’t show any record of bookwandering.’

‘How does he check?’ Oskar asked.

‘The stamps are linked to what ends up looking a lot like a diary,’ Seb explained. ‘Where you’ve bookwandered will be recorded in a list showing when and where you went. Yours will stay blank because you’re not actually being stamped – but he’ll assume that he has frightened you into submission. Showing that he does not know you very well, I might add.’

‘Couldn’t you do that for my grandparents as well?’ Tilly said.

‘I think Melville would be more suspicious if they were showing as not bookwandering at all. There’s no chance he would think he could scare Archie and Elsie.’

And despite how worried she felt, Tilly couldn’t help but feel a little proud.

‘So what is it that Angelica is actually going to do to them?’ Oskar said. ‘Tilly didn’t realise when she’d been stamped, so it’s obviously not, like, a big ink stamp … Is it?’

‘No, not quite so literal,’ Seb said, smiling despite the situation. ‘Chalk must have secretly stamped Tilly that first time he visited Pages & Co. To put a library stamp on someone you just need to get a little bit of book magic to stick to them, and then you can trace that magic trail. As Melville said, it doesn’t tell anyone where you are in real life, it simply creates a sort of diary, or map of the books you’ve wandered into. It’s not harmful, but Melville’s plan to use so much book magic is deeply concerning. This magic is woven into the structure of stories, but extracting it is a violent thing. You have to break a story a little bit, cause a rupture, and then you can siphon off some of that book’s magic. In the Underlibrary our main source, when and if we need it, is from books that are out of print or that have a major error in them and can’t be sold or loaned. We buy them up and pulp them, and can distil a little bit of book magic from them. Our method may not extract such potent magic but it doesn’t endanger stories in the same way. Remember, books are just the holders of stories, not the thing itself. And so, if someone wants to be traced – say if they are going into a dangerous book – they can wear a little bit of book magic in a locket, or simply dab a bit on to their body. It looks a lot like ink. In fact, as you saw at the Ceremony earlier, the ink used there has book magic in it to bind the Librarians to the Underlibrary and vice versa.’

‘How long does it last?’ Oskar asked.

‘If you put book magic directly on your skin, it lasts a few months at most,’ Seb said. ‘And that’s the other reason we don’t need to worry too much about your grandparents. They just need to be careful for a bit, while we work out a proper plan.’

‘Okay,’ Tilly said, feeling a little calmer. ‘You know, when people talked about book magic, I didn’t realise they were talking about a physical thing.’

‘Same,’ Oskar said. ‘I thought it was all, like, ooooh, the magic of books! Reading is important! You know, like teachers say.’

‘Oh no,’ Seb said. ‘I mean, what teachers say is of course true, but our book magic is what runs through all stories and powers them. Did you hear what Melville said about fairy tales? They’re so unstable because they’re running on pure book magic that’s not contained in Source Editions and printed books. It’s ancient book magic – even Librarians don’t really understand how it works.’

‘But, Seb, hang on,’ Tilly started. ‘What did Melville mean when he talked about binding all the books? Does that use book magic too?’

‘Well, as Mr Underwood said, it’s not possible to take someone’s bookwandering abilities away from them – they’re a part of you. But you can stop people from accessing certain books. If a Source Edition of a book is “bound” then no one can wander inside any of the versions of it. It controls where people can wander. There was a group of bookwanderers back in the early nineteenth century who thought that bookwandering should be limited to only certain types of people – rich like them, mainly. Now there are some Librarians here who have taken their name, the “Bookbinders”, and are spouting nonsense about control being a good thing.’

‘But why?’ Tilly asked. ‘What’s in it for them?’

‘Power, mainly,’ Seb said. ‘If you control something it gives you power over the people who want it – or need it. People like the Bookbinders hate the idea of something being shared out and enjoyed. They think they deserve to have it all to themselves. And so it has always been.’

‘But just because something has always been that way doesn’t make it right,’ Tilly said.

‘Of course not,’ Seb said. ‘But it does make it difficult to change. It doesn’t mean we shouldn’t try, though.’

‘Seb,’ Tilly said. ‘Do you think Melville really has found Chalk?’

‘It would seem so,’ Seb said. ‘And that’s a good thing, even if we don’t agree with anything else he’s doing. Bookwandering is complicated; it’s not as easy as people who aren’t for us being against us.’

‘I think it’s clear he is definitely against us,’ Oskar said. ‘Not sure that’s too complicated.’

‘But that doesn’t mean we don’t want some things in common,’ Seb said. ‘Such as finding Chalk. It’s in no one’s interest for Chalk to roam around stories, especially fairy tales. So let’s focus our energies on stopping Melville’s bigger bookbinding plans, and let him deal with Chalk.’

At that moment, they heard a door being slammed shut, and they poked their heads out of the room to see three very angry, flustered-looking people glaring at each other in the corridor.

‘I’m just doing my job, Mr Pages,’ Angelica was saying. ‘I didn’t make this decision. And now I’m leaving. Take it up with Mr Underwood if you’re unhappy.’

‘Have you considered maybe thinking for yourself for one moment?’ Grandad said crossly. ‘You don’t have to do everything you’re told.’

‘The thing is,’ Grandma said, clearly making a conscious effort to remain calm, ‘it’s important to think about what you’re being asked to do, and whether you think it’s right.’

‘This isn’t something I want to lose my job over,’ Angelica said. ‘Isn’t the whole point of the senior librarians to worry about this sort of thing for us, so we don’t have to?’

‘No!’

Grandad exploded.

‘Their purpose is to protect bookwandering! Not to be blustering, idiotic tyrants!’

He noticed the others, peering through the door behind him. ‘Finally! Tilly, Oskar, let’s go. I do not want to stay one more moment in an institution which has become the very antithesis of what it was set up to do!’ He took Tilly and Oskar by the shoulder and steered them out of the door, Grandma and Seb following.

‘To the Map Room, yes?’ Grandad said. ‘We need to get back to Pages & Co. as quickly as possible.’

‘Do you think that’s wise?’ Seb said nervously.

‘I could not care less at this point,’ Grandad replied. ‘Could you please tell Amelia to get in touch with us as soon as she is able to extricate herself from this place?’

‘Yes, of course,’ Seb said. ‘And don’t worry about Tilly and Oskar,’ he added. ‘I didn’t stamp them.’

Grandad softened. ‘Thank you, Seb,’ he said. ‘I should never have doubted you. Please come and see us with Amelia if you can. There is a lot to talk about.’

(#ulink_326ce693-743e-5715-8c53-48c11d869f0d)

alf an hour later they were sitting round the kitchen table drinking very strong cups of tea, with out-of-character two spoons of sugar, or usually-reserved-for-special-occasions fizzy drinks.

‘I’m still not sure I understand how we can travel from the Map Room home,’ Tilly said. ‘Is it book magic too? And can we get to the Underlibrary the same way?’

‘Ah,’ Grandad said, a little sheepishly. ‘Well, yes and no. It’s not exactly an approved transport method. And Pages & Co. shouldn’t technically still be on the network.’

‘When you’re the Librarian,’ Grandma explained, ‘you get a few favours from some of our fictional friends. One of those is that a character who specialises in magical doors and portals, say a charismatic lion or similar, will come and create one in the Underlibrary Map Room that opens in the Librarian’s home bookshop or library – just in case of emergencies. It’s supposed to be closed when a new Librarian takes over, so we don’t have magic portals criss-crossing the country. Not to mention it’s generally frowned on to bring magical characters into the real world. But Amelia turned a blind eye when she took over, and I think we can assume that she won’t be letting Melville know that the Pages & Co. portal still exists.’

‘In case you need to get back in without him noticing?’ Oskar asked.

‘Precisely,’ Grandad said.

‘Although let’s hope it doesn’t come to that,’ Grandma said. ‘We need to understand a lot more about what exactly is going on before we start sneaking around.’

‘So … What do we do first?’ Tilly asked.

‘Well, you two are doing exactly what you were always going to do.’ Grandma smiled. ‘You’re going to Paris tomorrow morning to visit Oskar’s dad for Christmas!’

‘But what about Melville and the stamping and the bookbinding? And banning children from bookwandering! Can’t I help?’ Tilly persisted.

‘While you’re away we will speak to Amelia and Seb properly,’ Grandma replied. ‘In hindsight, it perhaps wasn’t such a good idea for you both to come today but thankfully Seb has diverted any immediate problems – not that this is permission for you to bookwander anywhere dangerous of course.’

‘And don’t worry about us,’ said Grandad. ‘The stamping is an ethical problem, not a practical one. It will wear off soon and it’s not like we had any illicit bookwandering trips planned. The thing we need to focus on is stopping them binding books, and you can leave that with us. We’ll talk to some librarians about the Bookbinders. And, of course, leave Chalk to Melville.’

‘Is there really nothing we can do to help?’ Oskar asked.

‘Not right now,’ Grandad said.

‘Not even any research, or reading, or anything?’ Tilly persisted.

‘You can help by having a wonderful time in Paris meeting Oskar’s dad,’ Grandad said firmly. ‘Leave this one with us. And now, dinner!’

Half an hour later Grandad set down a big bowl full of spaghetti cooked with tomatoes and prawns. Grandma added hot buttery garlic bread and a rocket salad as Bea came and joined them from the just-closed bookshop. The table bore the marks and memories of years of the Pages family; the underside was still covered with the remnants of Tilly’s attempt to turn it into a spaceship when she was younger, sticking coloured paper buttons on with superglue. The surface had several red wine stains, a collection of pale circles where hot drinks had been put down without coasters, and copious scratches on the legs from Alice the cat. It held centre stage in the area that functioned as a dining room, a study and a private family space away from the bookshop. It was rare for the table not to be covered with piles of books, half-done homework, lukewarm cups of tea, or unopened post.

‘So, Oskar,’ Grandma said, sitting down. ‘How long is it since you’ve been to Paris?’ Oskar was busy trying to sneak a corner of garlic bread into his mouth, before realising quite how hot it was.

‘I haven’t been since the summer holidays,’ Oskar said, trying to suck cool air into his mouth as he replied. ‘With Mamie being poorly over half-term, and school and stuff … You know how busy everything gets. And Dad hardly gets any holiday so he can’t come here very often either.’

‘It’s very kind of your dad to invite Tilly as well,’ Bea said, twirling her fork around her pasta without ever raising it to her mouth. ‘What did you say his job was?’

‘He runs an art gallery with my stepmum,’ Oskar said. ‘They’re super busy all the time. I think it was Mum’s idea for us to go, probably.’

‘They do know I’m coming, though, right?’ Tilly said, alarmed.

‘Yes, of course,’ Grandma reassured her. ‘We’ve spoken to him several times on the phone to sort out train tickets and what you need to take – they’re really looking forward to meeting you. And you’ll get to meet Oskar’s grandmother too, as she’s staying with them – maybe you’ll even see some of her illustrations!’

‘There’s one of her paintings up in my dad’s place,’ Oskar confirmed. ‘It’s super creepy and cool.’

‘What a treat,’ Grandma said, trying to coax some enthusiasm out of Tilly.

‘It’s going to be strange not being at Pages & Co. just before Christmas,’ was all Tilly said.

‘But what an adventure!’ Grandad said. ‘Being in Paris at Christmastime!’

‘We’ll miss you a lot, though, won’t we, Bea?’ Grandma said, nudging her daughter.

‘I can barely remember what Christmas is like,’ Bea said, almost to herself. ‘It will be curious having a tree and turkey and all of that again.’

‘Didn’t you have Christmas in A Little Princess?’ Oskar asked.

‘Well, I assume we must have,’ Bea said slowly. ‘But I find it hard to remember anything specific about being there at all, really. It’s like trying to remember a dream. I just can’t seem to picture any of it.’ And she went back to toying with her wine glass.

Tilly had hoped that her mum would settle back into normal life more each day, following her rescue from A Little Princess. But the opposite seemed to be true. Bea spent more and more time by herself, and could be found lost in her own daydreams for much of the day. Pushing her glass to one side, Bea shook her head, and smiled – properly – at Tilly.

‘But you’ll only be gone for a couple of days, and you’ll be back in plenty of time for Christmas. Now, who’s for coffee?’ Bea moved her nearly full bowl away from her and stood up, mussing Tilly’s hair as she went to put the kettle on. Tilly tried to shove away her worries about her mother into a room right at the very back of her brain – along with her worries about what was going on at the Underlibrary. She wedged a chair under the door handle for good measure, to keep them locked in tight.

(#ulink_0f2b2f89-f974-5ca2-a083-f7f837f4a029)

here was something special about Pages & Co. first thing in the morning, especially if you were the only one in the shop. There was an air of expectation and endless possibility stacked neatly along the tidy shelves, adventure tucked between dust jackets. Tilly sat cross-legged on the emerald-green velvet sofa by the fireplace, and watched the snow fall outside. The shop was still chilly, and Tilly’s hands were wrapped round a hot cup of a home-made concoction that Grandma called mulled Ribena. She sipped carefully as the snowflakes danced and settled on the glass.

‘I sometimes imagine they are tiny dancing snow sprites,’ a familiar voice said, and Tilly turned to see Anne Shirley, the heroine of one of Tilly’s favourite books, sitting at the other end of the sofa staring out of the window in wonder.

‘Oh!’ Tilly said abruptly, looking at her. ‘Anne … Do you know that your hair is green?’

Anne turned and looked at her mournfully.

‘I have had such a terrible time of it. You would scarcely believe it could all happen to one person,’ she said dejectedly. ‘Truly the fates are against me. I thought I was dyeing it a beautiful, elegant raven black, but the man I bought the dye from at the doorstep has cruelly taken advantage of my vanity and, well, look. I have been washing it furiously for three days straight now and no change. My life in the most glittering of social circles has ended before it had a chance to even begin. It is one thing to go to a dance as a redhead, but quite another to make an entrance with green hair, especially in a town so ravenous for gossip as Avonlea. Just imagine what Rachel Lynde would say if she saw me!’ She flopped her head dramatically on to the back of the sofa and let out a groan of woe. ‘I am far too embarrassed to leave Green Gables – I will only permit dear Diana to visit as she is able to behave in the sombre manner that befits the situation – and so it’s a pleasant surprise to find myself here. Were you thinking of me?’

‘I suppose I must have been in some way, for you to arrive,’ Tilly said. ‘And do you know, short hair is very fashionable here? You could always cut it.’

‘Oh, I don’t think so,’ Anne said solemnly. ‘Why, the only thing worse than green hair would be short green hair. And if it comes to that I think I shall have to withdraw from polite society entirely.’

‘Well, fingers crossed it doesn’t come to that,’ Tilly said weakly, knowing – from having reread Anne of Green Gables just the other week – that it was destined to turn out exactly like that. Anne rested her green head on Tilly’s shoulder and sighed.

‘Winter is the most magical time of year, isn’t it?’

‘You say that about every season,’ Tilly said affectionately.

‘Perhaps,’ Anne said. ‘But the important thing is that I mean it fiercely in the moment. I do sometimes find that I mean things wholly and entirely when I say them only to discover that the next day, or the next season, my opinions have changed. Marilla says this makes no matter, and that falsehoods dressed up as enthusiasm are still falsehoods, but I think that if you mean something sincerely when you say it then it is the truth, whatever happens next, and that enthusiasm is a very good reason for almost anything – especially winter.’

‘I wonder what winter in Paris will be like,’ Tilly mused.

‘You’re going to Paris?’ Anne said, sitting bolt upright. ‘Why how perfectly romantic! When are you going?’

‘Very soon,’ Tilly said. ‘Our train leaves St Pancras station just before lunchtime, I think. Although I’m not sure it’s a good time to be going …’

‘Whyever not?’ Anne asked. ‘I should have thought that there was no such thing as a bad time to go to Paris!’

‘Well, a lot has been going on here,’ Tilly said. ‘And I don’t really know where I fit into it all. Grandma and Grandad say they’re going to fix everything while we’re away but I don’t really see how they will be able to do that, and Amelia – our friend – has lost her job, and no one seems worried about what Chalk is up to. And I just don’t know what anything means, and it feels strange to just pop over to Paris for a holiday when everyone seems so stressed and my mum is still so sad.’

‘She’s still sad?’ Anne asked gently.

‘Yes,’ Tilly said. ‘And she basically stays here all the time. She hasn’t gone into any stories since we said goodbye to my dad, and she won’t even talk to me about it either. It’s like we’re strangers.’

‘Well, it must be ever so peculiar to go from having a newborn daughter one day and then, suddenly, the next time you see her, she’s eleven and a whole proper person with her own dreams and memories and desires,’ Anne said. ‘It’s one of those ideas that sounds like it might be quite romantic if you read it in a book but when it happens to one of your bosom friends, you can’t help but worry it’s a little confusing and tragic.’

‘I mean, I’m not sure I’d go quite as far as tragic,’ Tilly said, bristling. ‘At least she’s back now. You shouldn’t feel sorry for me.’

‘I don’t at all,’ Anne said earnestly. ‘How could I feel sorry for someone who lives in a bookshop and has two grandparents, and one whole mother to love her, and is going to Paris in the snow! Why I would never trade Green Gables for anything, but I would not be so sad to have your lot in life.’

‘I suppose so,’ Tilly said, trying to feel as lucky as she knew she was, really.

The sound of the kitchen door banging made her jump, and she looked up to see Grandma heading her way.

‘Are you all right, love?’ she asked, sitting next to Tilly on the sofa, a book under one arm.

‘Anne’s just gone,’ Tilly said. ‘We were just chatting. And she had green hair.’

‘Ah, the green hair incident. I wish I could have seen it. It’s good to have friends you can talk things through with, you know,’ Grandma said. ‘I’m glad you have Anne, and Oskar. He takes in more than I think you sometimes realise. It will be lovely for you both to visit Paris and his family. Now, I wanted to share something with you before you go.’

Grandma placed the book she was carrying gently on her lap. ‘I thought you might like to have a look at this – it’s my book of fairy tales back from when I was working in the Underlibrary – it’s where I used to start from when I was mapping them.’

The book was very old and battered, with slips of paper marking certain yellowed pages and a few corners turned down. Tilly carefully opened the front cover and saw an intricately decorated contents page of familiar stories.

‘France is in some ways the home of fairy tales, certainly those in the Western tradition that are most familiar to us. Many of them were first written down in France, even if they originated elsewhere,’ Grandma explained. ‘It’s too dangerous to bookwander there at the moment, but if you’re keen, maybe we could go together once everything’s settled down?’

‘Yes, please,’ Tilly said, as she turned through the pages. ‘You said … You said there was a difference of opinion and that’s why you stopped working in fairy tales?’

‘Well, yes,’ Grandma said, a little hesitantly. ‘When I was the Cartographer I worked with another librarian, who used to be a close friend, and our job was to try and create a map of how fairy tales fitted together, and to research why the usual rules don’t apply there. We wandered together many times, exploring the stories and the fairytale lands. It really is a fascinating place. But once we started to get somewhere with our research, the next stage was to use what we’d learned to make fairy tales safer for bookwanderers, and to share our maps. However, my friend got what I can only describe as cold feet about the whole project. Through our time inside the stories, she decided that we shouldn’t be trying to make them safer, and their danger was what made them special. She believed that we were trying to impose order on something wild and beautiful. And to be honest, I agree with her to a certain point, but she started seeing conspiracy theories everywhere and ended up being forced to … Well, she ended up leaving the Underlibrary.’

‘Why does nobody seem to be able to agree on how bookwandering should work?’ Tilly asked.