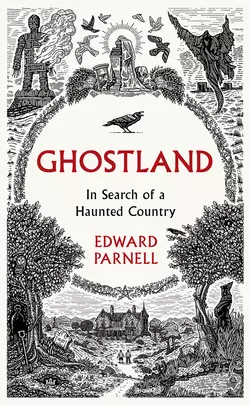

Ghostland: In Search of a Haunted Country

Edward Parnell

‘A uniquely strange and wonderful work of literature’ Philip Hoare ‘An exciting new voice’ Mark Cocker, author of Crow Country In his late thirties, Edward Parnell found himself trapped in the recurring nightmare of a family tragedy. For comfort, he turned to his bookshelves, back to the ghost stories that obsessed him as a boy, and to the writers through the ages who have attempted to confront what comes after death. In Ghostland, Parnell goes in search of the ‘sequestered places’ of the British Isles, our lonely moors, our moss-covered cemeteries, our stark shores and our folkloric woodlands. He explores how these landscapes conjured and shaped a kaleidoscopic spectrum of literature and cinema, from the ghost stories and weird fiction of M. R. James, Arthur Machen and Algernon Blackwood to the children’s fantasy novels of Alan Garner and Susan Cooper; from W. G. Sebald’s The Rings of Saturn and Graham Swift’s Waterland to the archetypal ‘folk horror’ film The Wicker Man… Ghostland is Parnell’s moving exploration of what has haunted our writers and artists – and what is haunting him. It is a unique and elegiac meditation on grief, memory and longing, and of the redemptive power of stories and nature.

(#uf97dc8e2-8fb1-5d72-a832-179bd823c5ec)

Copyright (#uf97dc8e2-8fb1-5d72-a832-179bd823c5ec)

William Collins

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.WilliamCollinsBooks.com (http://www.WilliamCollinsBooks.com)

This eBook first published in Great Britain by William Collins in 2019

Copyright © Edward Parnell 2019

Cover illustrations and chapter initial illustrations are by Richard Wells (www.richardwellsgraphics.com (http://www.richardwellsgraphics.com))

All other images are by the author, or from the author’s own collection. While every effort has been made to trace the owners of copyright material, in some cases this has proved impossible. The publishers would be grateful for any information that would allow any omissions to be rectified in future editions of this book.

Edward Parnell asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

The Emigrants by WG Sebald published by Harvill Press, reprinted by permission of The Random House Group Ltd. © 1996

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008271954

eBook Edition © October 2019 ISBN: 9780008271961

Version: 2019-10-01

Dedication (#uf97dc8e2-8fb1-5d72-a832-179bd823c5ec)

For the ghosts

Epigraph (#uf97dc8e2-8fb1-5d72-a832-179bd823c5ec)

‘And so they are ever returning to us, the dead.’

W. G. Sebald, The Emigrants

Contents

1 Cover (#u25b7f403-8577-57a4-906f-03c1f588a552)

2 Title Page

3 Copyright

4 Dedication

5 Epigraph

6 Contents (#uf97dc8e2-8fb1-5d72-a832-179bd823c5ec)

7 Prologue

8 1 LOST HEART

9 2 DARK WATERS

10 3 WALKING IN THE WOOD

11 4 THE ROARING OF THE FOREST

12 5 MEMENTO MORI

13 6 BORDERLAND

14 7 GOBLIN CITY

15 8 LONELIER THAN RUIN

16 9 WHO IS THIS WHO IS COMING?

17 10 NOT REALLY NOW NOT ANY MORE

18 11 TROUBLE OF THE ROCKS

19 12 ANCIENT SORCERIES

20 Epilogue

21 Selected List of Sources

22 Acknowledgements

23 Index

24 Also by Edward Parnell

25 About the Author

26 About the Publisher

LandmarksCover (#u25b7f403-8577-57a4-906f-03c1f588a552)FrontmatterStart of ContentBackmatter

List of Pagesiii (#ulink_b94472c6-b776-5fa8-9b46-8a1fc362d21a)iv (#ulink_7543946e-28b3-5986-806a-f153709b6f72)v (#ulink_fe76a6e5-aa9b-570c-b13b-8220173bdc5f)vii (#ulink_845c74f0-9d0d-55ab-ad7c-5d492104a39d)1 (#ulink_d4587aa5-031c-5241-bbff-e291673b923b)2 (#ulink_3edfef3c-2c85-54cf-ac8c-32610ef77a0e)3 (#ulink_2e0c55a6-d82f-5a59-9f8d-1872604f2bf1)4 (#ulink_c2c322c7-4dbe-5977-ae36-98f37fd48d6c)5 (#ulink_b4023747-155f-5ac8-a663-8d15ccf37791)6 (#ulink_1aab2bfa-4e7f-5528-a221-4fe4340175c4)7 (#ulink_86090d9c-2ffd-53c2-8d5d-939d184d6d03)8 (#ulink_17d3fb42-7bb4-5391-8b60-f6f4d3b6a8c4)9 (#ulink_35c32f40-d0f4-5421-92d9-c6160c92bfa5)10 (#ulink_8fbb571b-6996-5d4b-87a8-fc0923e7061b)11 (#ulink_3f0fff18-bece-5091-a8fd-4d012e5e6c57)12 (#ulink_4f7e2e5a-2959-58af-87c6-9dcae2d652d3)13 (#ulink_e29371fd-ae6b-5a77-b163-f68fb365f7bd)14 (#ulink_c21e420a-8bdc-5bf8-bc16-6c07741c9def)15 (#ulink_c0c6ed04-ad15-564e-97c2-5d797a031b4e)16 (#ulink_af45ed94-824f-592b-8169-b6e7df688904)17 (#ulink_dae00f5d-ec4e-5697-93c7-df2766256724)18 (#ulink_3e6ad431-d222-5024-a849-b3c626f4dafa)19 (#ulink_e04849d8-3b1f-5deb-8be4-a0c1c3af44e4)20 (#ulink_272f8e5c-159c-5e97-9878-b019a97ee44d)21 (#ulink_272f8e5c-159c-5e97-9878-b019a97ee44d)22 (#ulink_ccbc99ae-05e5-52bb-8e35-6db89117128b)23 (#ulink_750ffc79-11f7-58ea-8dc8-f29e577b907b)24 (#ulink_7ac63468-8b6a-58ac-93ce-16b881ff80c5)25 (#ulink_7ac63468-8b6a-58ac-93ce-16b881ff80c5)26 (#ulink_8b7992d1-5048-5e03-a00a-4306241ccf51)27 (#ulink_285ece3b-d54e-5457-929b-e261347358c0)28 (#ulink_32d2c6ed-b610-5c1b-a456-47e85f6ecb13)29 (#ulink_8a58019b-ad05-5d8e-b905-b3bb13eb98c2)30 (#ulink_f6923c4c-08e4-5331-9c3c-1216f9a80626)31 (#ulink_c3eadd6e-0eee-57bf-b5c8-7a63afddfa9b)32 (#ulink_cdce6fa3-0c0e-5081-98aa-8a8de0bcab56)33 (#ulink_cdce6fa3-0c0e-5081-98aa-8a8de0bcab56)34 (#ulink_c1f1e419-9d53-5321-8de3-e03599cf6f6d)35 (#ulink_5d9ef466-822a-5a40-ad03-59c565c5d410)37 (#ulink_12d5dd8f-779f-56da-b747-b353e4358e20)38 (#ulink_c89ff7f9-00de-5604-9235-4b76d45c006e)39 (#ulink_b86b1f58-d8df-57b0-85a6-c010861ff504)40 (#ulink_f7f6ff51-27bf-53ed-90fc-f824c75c9d80)41 (#ulink_cf7e011c-998e-5b6b-b79f-f22c4145ae12)42 (#ulink_b10bee9e-316b-58fa-9c39-0e088fed1811)43 (#ulink_cb118044-fc57-5c69-83e6-74ab16034740)44 (#ulink_ceddb7c4-e46f-5199-a54d-2b0478d899fa)45 (#ulink_ceddb7c4-e46f-5199-a54d-2b0478d899fa)46 (#ulink_50e6b09d-32ad-5071-a0c2-7269fcc3983b)47 (#ulink_98012912-5adc-5f3c-b287-4aca9b488c3f)48 (#ulink_d726dbfd-ee49-53be-bf1b-d90e27e6bdbb)49 (#ulink_d8cac0b4-71de-5d69-9afb-634157d3c8c8)50 (#ulink_bd59bdc5-115d-5c3e-a002-a0cdb2d585c5)51 (#ulink_2e413c8e-bffc-51c0-81e5-473089a1a585)52 (#ulink_c15e09aa-290b-59ba-b404-b980a8617f06)53 (#ulink_a9a626ff-eaec-539c-a1ed-415c3932494d)54 (#ulink_88dc6412-b6a9-58fa-b322-c0b54af932b7)55 (#ulink_ed7398e9-f4dc-51db-a219-f0eb242dcee6)56 (#ulink_9ec43a07-a46b-57fc-8bbe-b49380174992)57 (#ulink_fadab555-cc1a-5ead-9d81-36792a25c0c5)58 (#ulink_d3298942-06ba-5d40-85ee-d80bc543752d)59 (#ulink_e155532a-be21-5f4a-a94c-85499fdef196)60 (#ulink_0912d317-d3e8-52c0-9c8f-c0158d477a75)61 (#ulink_0e453e40-8426-5ae3-8d72-1853db144dcf)62 (#ulink_ab10f4b0-a2fc-5654-b4ad-57984b4cc0f2)63 (#ulink_fcf4cc8e-cd1b-5ce6-93f5-a0ce91b99518)64 (#ulink_6c95a1d9-f787-58a7-9afe-f9674fddf0ce)65 (#ulink_6b896c8f-9757-512e-9f57-5f9d413e56e4)66 (#ulink_22bf9c6a-deb0-56d5-a670-f83aa981371b)67 (#ulink_108b98cd-4166-5832-a463-bfe5c505b5d3)68 (#ulink_0db7d737-c297-5531-8b80-3e82717ac1e3)69 (#ulink_6e8b978c-8062-5aa3-9029-971a88b1e0bc)70 (#ulink_31426634-0801-5e04-8912-41f1bc2cab24)71 (#ulink_83d725aa-1a93-555c-b40e-149ec07c0608)72 (#ulink_12278898-6c0b-5a24-bd27-7ac6346bc042)73 (#ulink_8579e493-1a59-5d7d-8657-2043c7f1ee44)74 (#ulink_79232ce5-57c8-560a-a720-19622bf062ba)75 (#ulink_c8929a8f-768d-5bf9-8bb8-00f6707fc5d2)76 (#ulink_63bb61d8-141b-563f-b50a-67b3401ba74e)77 (#ulink_8d6e26d5-2518-5954-b74a-974e73ffabd7)78 (#ulink_7882f688-9538-5756-80f8-f899cba47c8d)79 (#ulink_e382647a-69c5-58a8-a928-7271ba25e1ea)80 (#ulink_708d2d73-3923-5d20-887d-a5e5d41e7c9f)81 (#ulink_a001aa39-4592-58ac-a60f-dcec19fd8a71)82 (#ulink_1ccd555b-8f42-5fe7-855e-cfc6f7ac2da0)83 (#ulink_e5390ec1-50aa-5436-a331-281afb885c09)84 (#ulink_0b4aaa53-5f50-5e80-b337-9261e8bdff9e)85 (#ulink_97bd68d4-e8b4-5f25-982c-38d2ea7fefd7)86 (#ulink_61ccaf04-9f73-593f-9998-213a81261f8c)87 (#ulink_2e1e7cb7-d6e3-51ff-b064-4f25c4694361)88 (#ulink_2efcde95-2d36-5fb3-ab71-4f2a468248d1)89 (#ulink_7eb3286f-afc1-5dc4-804d-c3a618d008f5)90 (#ulink_07fc2b90-651b-58f7-88d7-c320f504ef46)91 (#ulink_5e8f2c49-54b5-594a-9af7-0864a218239b)92 (#ulink_5e8f2c49-54b5-594a-9af7-0864a218239b)93 (#ulink_8c7ca949-57ed-5dcb-83ea-bff6179713d1)94 (#ulink_f18be28d-ff12-513f-b0c5-e8ce3aadcdd8)95 (#ulink_3481c6ea-50c6-52d6-8976-9cf5d680239c)96 (#ulink_2160a87b-f432-56a0-af23-456478286414)97 (#ulink_0fb52623-63e8-5484-93fc-4bfadef6d6b9)98 (#ulink_a4939bbd-7dd0-51b1-8fb7-78b135636dac)99 (#ulink_6d16144a-f485-5eee-b28e-b6f0b157ffd0)100 (#ulink_26db8185-3ba6-555b-ad85-b67d73018587)101 (#ulink_2a0935be-12e9-5576-a63f-ba306bd91064)102 (#ulink_cde29a7c-8c3f-5d3c-a19c-3516db0b86ad)103 (#ulink_4d5c4a96-d645-5228-b754-0a3c035e6d58)104 (#ulink_71c690ba-9c39-5e7b-aa1d-9ced5a8639f4)105 (#ulink_006ab9a3-8808-53d7-a32f-68a29fb064b5)106 (#ulink_c31e46c0-6bed-510c-a6db-03457af72274)107 (#ulink_af0e5e8c-827c-5e79-931c-bfeac47d9bd8)108 (#ulink_5b500305-278f-5ab2-83fd-160fe60eed9c)109 (#ulink_df95347e-2e7f-59b0-a4b3-bc37ad25780a)110 (#ulink_29ec6b6c-11c9-551d-8fcc-89bd422e3236)111 (#ulink_8918d582-661e-5a04-a9fc-8ca482e41ebb)112 (#ulink_8918d582-661e-5a04-a9fc-8ca482e41ebb)113 (#ulink_425423d2-fd3d-5eb3-bb69-c7ab5f1f9b9a)114 (#ulink_0dbe5cf8-5ebb-5acd-bfca-94ae1cae354c)115 (#litres_trial_promo)116 (#litres_trial_promo)117 (#litres_trial_promo)118 (#litres_trial_promo)119 (#litres_trial_promo)120 (#litres_trial_promo)121 (#litres_trial_promo)122 (#litres_trial_promo)123 (#litres_trial_promo)124 (#litres_trial_promo)125 (#litres_trial_promo)126 (#litres_trial_promo)127 (#litres_trial_promo)128 (#litres_trial_promo)129 (#litres_trial_promo)130 (#litres_trial_promo)131 (#litres_trial_promo)132 (#litres_trial_promo)133 (#litres_trial_promo)134 (#litres_trial_promo)135 (#litres_trial_promo)136 (#litres_trial_promo)137 (#litres_trial_promo)138 (#litres_trial_promo)139 (#litres_trial_promo)140 (#litres_trial_promo)141 (#litres_trial_promo)142 (#litres_trial_promo)143 (#litres_trial_promo)144 (#litres_trial_promo)145 (#litres_trial_promo)146 (#litres_trial_promo)147 (#litres_trial_promo)148 (#litres_trial_promo)149 (#litres_trial_promo)150 (#litres_trial_promo)151 (#litres_trial_promo)152 (#litres_trial_promo)153 (#litres_trial_promo)154 (#litres_trial_promo)155 (#litres_trial_promo)156 (#litres_trial_promo)157 (#litres_trial_promo)158 (#litres_trial_promo)159 (#litres_trial_promo)160 (#litres_trial_promo)161 (#litres_trial_promo)162 (#litres_trial_promo)163 (#litres_trial_promo)164 (#litres_trial_promo)165 (#litres_trial_promo)166 (#litres_trial_promo)167 (#litres_trial_promo)168 (#litres_trial_promo)169 (#litres_trial_promo)170 (#litres_trial_promo)171 (#litres_trial_promo)172 (#litres_trial_promo)173 (#litres_trial_promo)174 (#litres_trial_promo)175 (#litres_trial_promo)176 (#litres_trial_promo)177 (#litres_trial_promo)178 (#litres_trial_promo)179 (#litres_trial_promo)181 (#litres_trial_promo)182 (#litres_trial_promo)183 (#litres_trial_promo)184 (#litres_trial_promo)185 (#litres_trial_promo)186 (#litres_trial_promo)187 (#litres_trial_promo)188 (#litres_trial_promo)189 (#litres_trial_promo)190 (#litres_trial_promo)191 (#litres_trial_promo)192 (#litres_trial_promo)193 (#litres_trial_promo)194 (#litres_trial_promo)195 (#litres_trial_promo)196 (#litres_trial_promo)197 (#litres_trial_promo)198 (#litres_trial_promo)199 (#litres_trial_promo)200 (#litres_trial_promo)201 (#litres_trial_promo)202 (#litres_trial_promo)203 (#litres_trial_promo)204 (#litres_trial_promo)205 (#litres_trial_promo)207 (#litres_trial_promo)208 (#litres_trial_promo)209 (#litres_trial_promo)210 (#litres_trial_promo)211 (#litres_trial_promo)212 (#litres_trial_promo)213 (#litres_trial_promo)214 (#litres_trial_promo)215 (#litres_trial_promo)216 (#litres_trial_promo)217 (#litres_trial_promo)218 (#litres_trial_promo)219 (#litres_trial_promo)220 (#litres_trial_promo)221 (#litres_trial_promo)222 (#litres_trial_promo)223 (#litres_trial_promo)224 (#litres_trial_promo)225 (#litres_trial_promo)226 (#litres_trial_promo)227 (#litres_trial_promo)228 (#litres_trial_promo)229 (#litres_trial_promo)230 (#litres_trial_promo)231 (#litres_trial_promo)232 (#litres_trial_promo)233 (#litres_trial_promo)234 (#litres_trial_promo)235 (#litres_trial_promo)236 (#litres_trial_promo)237 (#litres_trial_promo)238 (#litres_trial_promo)239 (#litres_trial_promo)240 (#litres_trial_promo)241 (#litres_trial_promo)242 (#litres_trial_promo)243 (#litres_trial_promo)244 (#litres_trial_promo)245 (#litres_trial_promo)246 (#litres_trial_promo)247 (#litres_trial_promo)248 (#litres_trial_promo)249 (#litres_trial_promo)250 (#litres_trial_promo)251 (#litres_trial_promo)252 (#litres_trial_promo)253 (#litres_trial_promo)254 (#litres_trial_promo)255 (#litres_trial_promo)256 (#litres_trial_promo)257 (#litres_trial_promo)258 (#litres_trial_promo)259 (#litres_trial_promo)260 (#litres_trial_promo)261 (#litres_trial_promo)262 (#litres_trial_promo)263 (#litres_trial_promo)264 (#litres_trial_promo)265 (#litres_trial_promo)266 (#litres_trial_promo)267 (#litres_trial_promo)268 (#litres_trial_promo)269 (#litres_trial_promo)270 (#litres_trial_promo)271 (#litres_trial_promo)272 (#litres_trial_promo)273 (#litres_trial_promo)274 (#litres_trial_promo)275 (#litres_trial_promo)276 (#litres_trial_promo)277 (#litres_trial_promo)278 (#litres_trial_promo)279 (#litres_trial_promo)281 (#litres_trial_promo)282 (#litres_trial_promo)283 (#litres_trial_promo)284 (#litres_trial_promo)285 (#litres_trial_promo)286 (#litres_trial_promo)287 (#litres_trial_promo)288 (#litres_trial_promo)289 (#litres_trial_promo)290 (#litres_trial_promo)291 (#litres_trial_promo)292 (#litres_trial_promo)293 (#litres_trial_promo)294 (#litres_trial_promo)295 (#litres_trial_promo)296 (#litres_trial_promo)297 (#litres_trial_promo)298 (#litres_trial_promo)299 (#litres_trial_promo)300 (#litres_trial_promo)301 (#litres_trial_promo)302 (#litres_trial_promo)303 (#litres_trial_promo)304 (#litres_trial_promo)305 (#litres_trial_promo)306 (#litres_trial_promo)307 (#litres_trial_promo)309 (#litres_trial_promo)310 (#litres_trial_promo)311 (#litres_trial_promo)312 (#litres_trial_promo)313 (#litres_trial_promo)314 (#litres_trial_promo)315 (#litres_trial_promo)316 (#litres_trial_promo)317 (#litres_trial_promo)318 (#litres_trial_promo)319 (#litres_trial_promo)320 (#litres_trial_promo)321 (#litres_trial_promo)322 (#litres_trial_promo)323 (#litres_trial_promo)324 (#litres_trial_promo)325 (#litres_trial_promo)326 (#litres_trial_promo)327 (#litres_trial_promo)328 (#litres_trial_promo)329 (#litres_trial_promo)330 (#litres_trial_promo)331 (#litres_trial_promo)332 (#litres_trial_promo)333 (#litres_trial_promo)334 (#litres_trial_promo)335 (#litres_trial_promo)336 (#litres_trial_promo)337 (#litres_trial_promo)338 (#litres_trial_promo)339 (#litres_trial_promo)340 (#litres_trial_promo)341 (#litres_trial_promo)342 (#litres_trial_promo)343 (#litres_trial_promo)344 (#litres_trial_promo)345 (#litres_trial_promo)346 (#litres_trial_promo)347 (#litres_trial_promo)348 (#litres_trial_promo)349 (#litres_trial_promo)350 (#litres_trial_promo)351 (#litres_trial_promo)352 (#litres_trial_promo)353 (#litres_trial_promo)354 (#litres_trial_promo)355 (#litres_trial_promo)356 (#litres_trial_promo)357 (#litres_trial_promo)358 (#litres_trial_promo)359 (#litres_trial_promo)360 (#litres_trial_promo)361 (#litres_trial_promo)362 (#litres_trial_promo)363 (#litres_trial_promo)364 (#litres_trial_promo)365 (#litres_trial_promo)366 (#litres_trial_promo)367 (#litres_trial_promo)368 (#litres_trial_promo)369 (#litres_trial_promo)370 (#litres_trial_promo)371 (#litres_trial_promo)372 (#litres_trial_promo)373 (#litres_trial_promo)374 (#litres_trial_promo)375 (#litres_trial_promo)376 (#litres_trial_promo)377 (#litres_trial_promo)378 (#litres_trial_promo)379 (#litres_trial_promo)380 (#litres_trial_promo)381 (#litres_trial_promo)382 (#litres_trial_promo)383 (#litres_trial_promo)385 (#litres_trial_promo)386 (#litres_trial_promo)387 (#litres_trial_promo)388 (#litres_trial_promo)389 (#litres_trial_promo)390 (#litres_trial_promo)391 (#litres_trial_promo)392 (#litres_trial_promo)393 (#litres_trial_promo)394 (#litres_trial_promo)395 (#litres_trial_promo)396 (#litres_trial_promo)397 (#litres_trial_promo)398 (#litres_trial_promo)399 (#litres_trial_promo)400 (#litres_trial_promo)401 (#litres_trial_promo)402 (#litres_trial_promo)403 (#litres_trial_promo)404 (#litres_trial_promo)405 (#litres_trial_promo)406 (#litres_trial_promo)407 (#litres_trial_promo)408 (#litres_trial_promo)409 (#litres_trial_promo)410 (#litres_trial_promo)411 (#litres_trial_promo)412 (#litres_trial_promo)413 (#litres_trial_promo)414 (#litres_trial_promo)415 (#litres_trial_promo)416 (#litres_trial_promo)417 (#litres_trial_promo)418 (#litres_trial_promo)419 (#litres_trial_promo)420 (#litres_trial_promo)421 (#litres_trial_promo)422 (#litres_trial_promo)423 (#litres_trial_promo)424 (#litres_trial_promo)425 (#litres_trial_promo)426 (#litres_trial_promo)427 (#litres_trial_promo)428 (#litres_trial_promo)429 (#litres_trial_promo)430 (#litres_trial_promo)431 (#litres_trial_promo)433 (#litres_trial_promo)434 (#litres_trial_promo)435 (#litres_trial_promo)436 (#litres_trial_promo)437 (#litres_trial_promo)438 (#litres_trial_promo)439 (#litres_trial_promo)440 (#litres_trial_promo)441 (#litres_trial_promo)442 (#litres_trial_promo)443 (#litres_trial_promo)444 (#litres_trial_promo)445 (#litres_trial_promo)446 (#litres_trial_promo)447 (#litres_trial_promo)448 (#litres_trial_promo)451 (#litres_trial_promo)452 (#litres_trial_promo)453 (#litres_trial_promo)455 (#litres_trial_promo)456 (#litres_trial_promo)457 (#litres_trial_promo)458 (#litres_trial_promo)459 (#litres_trial_promo)460 (#litres_trial_promo)461 (#litres_trial_promo)462 (#litres_trial_promo)463 (#litres_trial_promo)464 (#litres_trial_promo)465 (#litres_trial_promo)466 (#litres_trial_promo)467 (#litres_trial_promo)ii (#litres_trial_promo)

Prologue (#uf97dc8e2-8fb1-5d72-a832-179bd823c5ec)

Always the ghosts.

Reaching into the past concealed behind the glow-in-the-dark cardboard apparitions that decorated my childhood bedroom, the fascination was there from the start: on a family holiday to Wales, aged four, asking the tour guide in Caernarfon Castle whether we might see the place’s spectral lady; a few years later, obsessing over Borley Rectory – the ‘most haunted house in the world’ – which called out to me from my spine-creased Usborne Guide to the Supernatural World; or, at the Halloween party I begged my mother to let me have (long before such events were a commonplace British occurrence), dressing up as Dracula, my friends as the Wolfman and various grinning ghouls.

The writer M. R. James once wrote: ‘For the ghost story a slight haze of distance is desirable. “Thirty years ago,” “Not long before the war,” are very proper openings.’

And if I think back through three decades of self-obfuscation, a host of recollections give confirmation.

With me, always the ghosts.

Yet even with hindsight no disquiet comes to me from these memories; they are reassuring, I can find shelter within them. Only later were we to become a phantom family – a host of lives lived, then unlived. The disquiet comes when I realise there’s no one left to help me reconcile the real and the half-remembered.

So, I must do it myself.

I must attempt to explore that sense so many before me have felt. The shadows they too have glimpsed among the fields, hills and trees of this haunted land.

To lay to rest the ghosts of my own sequestered past.

Chapter 1

LOST HEART (#uf97dc8e2-8fb1-5d72-a832-179bd823c5ec)

It was, as far as I can ascertain, on Christmas Eve of the year 1994 that a young man drew up before the door of his childhood home, in the heart of Lincolnshire. He looked about him with the keenest curiosity during the short interval that elapsed between the fumbling of his keys and the opening of the front door. Inside, he began to study the four programmes available on his television set, pausing before a presentation that caught his eye. The time was five minutes before one o’clock, he realised. Christmas Day itself …

This, more or less, was how I first became acquainted with the work of M. R. James, my favourite – and arguably Britain’s finest – writer of ghost stories. I was home for the holidays during my third year at university and had been into town to celebrate the festivities. A little the worse for drink, I was alone in the living room, as my brother Chris – nearly six years my senior – was still out with friends. In the morning the two of us would open our presents together before spending the rest of the day at my aunt and uncle’s. In an attempt to compensate for the house’s emptiness and our parents’ absence, we’d started a tradition of labelling our gifts to each other as if from various half-remembered figures from our past: obscure family acquaintances, disliked former teachers, or people who we had given nicknames to – like Porkpie, the middle-aged man in the pork-pie hat who was a constant fixture in the pub we frequented, boring anyone who’d listen about the supermarket where he worked.

Not ready for sleep, I lay on the sofa and flicked through the TV channels. On BBC Two a grainy drama from the seventies was beginning. What I’d chanced upon was an episode of the classic ‘A Ghost Story for Christmas’ strand: Lawrence Gordon Clark’s adaptation of M. R. James’s supernatural tale ‘Lost Hearts’.

There’s a fearful symmetry to this, I’ve come to learn, because this particular film was first shown on BBC One a little before midnight on Christmas Day 1973, less than a fortnight after I was born. Had I already witnessed it before as a crying baby – perhaps my mother had happened at that very point to switch on the TV set to try and calm my tears? If she had, I doubt she would have found much respite, because the BBC version is a frightening piece of work; I was to find this out some twenty-one years later, when the ghost of a razor-nailed boy and his dark-eyed companion appeared on the screen in front of me.

Through the white gate at the back of the graveyard the ground changes abruptly, the approach from the rectory with its aged, ivy-clad trees replaced by a squat jumble of shrubs and sedge, punctuated by paths that run aimlessly to the water. The ‘lake’, as it is called, seems out of place in the west Suffolk countryside, reminding me of one of the shallow, ephemeral coastal lagoons you find in the Camargue. Lifeless trunks point upwards from its greyness like rigor-mortised fingers. The division between land and water is tenuous; there are no banks as such, just a dirty shoreline of mud over which the waves lap, adding to the feature’s temporary feel. This is not a giant puddle left behind by a flood, or some deliberately drowned world, but a spring-fed mere that has given its name to the neighbouring village.

Livermere Lake. ‘The lake where rushes grow’, from the Old English laefor-mere. I’ve known about this place for a long time too: since my brother saw a vagrant black-winged pratincole here in 1993, a rare hawk-like wading bird. I couldn’t join him to see it, which, as a keen birdwatcher, riled me for years (until I finally caught up with one myself on the Norfolk coast) and lent the location an enduring mystique in my head. Only later did I become aware of the connection between Great Livermere and M. R. James.

Montague Rhodes James – known to his close friends as Monty – was born in Goodnestone, a small Kent village midway between Canterbury and Deal where his father was then curate, in August 1862. After three years the family moved to Livermere, six miles from Bury St Edmunds, when Herbert James took up the rectorship of St Peter’s Church, whose gravestones I passed between on my way to the mere. This section is Broad Water, with the narrow tree-lined southern arm, Ampton Water, snaking off somewhere behind me, obscured by a screen of trees. The rain slants sparsely down as I scan the surface and shore: there are no rare waders today, though a typically noisy pair of black-and-white oystercatchers flies past, splitting the silence with their piping.

Across the water stands a second church, the now-ruined St Peter and St Paul of Little Livermere, derelict since the first half of the twentieth century. The tower, according to James in his 1930 work Suffolk and Norfolk: A Perambulation of the Two Counties with Notices of their History and their Ancient Buildings, was heightened so as to be seen from Livermere Hall, itself long gone, demolished as superfluous in 1923. Its owner, Jane Anne Broke, was a relative by marriage of Herbert James, which was how he came to be offered the role of attending to the spiritual needs of the village – a serendipitous move in terms of its influence on young Monty’s future ghost stories. Stately homes and their surrounding parkland appear in a number of those tales, reflecting James’s upbringing as the son of a well-connected rector and the privileged circles in which he was to circulate during his later career as provost of both Cambridge’s King’s College and Eton’s famous public school.*

In ‘Lost Hearts’, the young protagonist Stephen Elliott stands at his open window listening to the strange noises coming from across the mere: ‘They might be the notes of owls or water-birds, yet they did not quite resemble either.’ The lake is rich with bird life, and it’s easy to picture the youthful James kept awake by their sounds – distorted by the space between mere and rectory – as he lay in his bedroom searching for sleep. Monty, however, appeared fond of his childhood home – various surviving fragments of juvenilia extol the virtues, and to an extent the eeriness, of the local landscape. In the undated poem ‘Sounds of the Wood’ he begins:

From off the mere, above the oaks, the hern

Come sailing, and the rook fly cawing home.

The scene in front of me is little changed from that the young James took pleasure in over a century ago. Sure enough, a heron is present this afternoon (‘hern’ is an archaic form of the word), roosting in the alders beside Ampton Water. A striking adult bird, its blue-grey plumage is broken up by its black-feathered shoulder and the thick stripe that extends above its eye.

I walk back towards the church of James’s father. A small deer – a muntjac, I presume – peers at me from through the sedges, sliding beneath the cover of a sallow before I can get a proper look. In the churchyard I wander among the headstones, one ghosted with the faint outline of a cherubic face, another with a lichen-covered skeleton. The commonest surname I find is Mothersole, the name James bestowed upon the witch from his story ‘The Ash Tree’. The horrifying Mrs Mothersole goes on to enact a spidery revenge on the descendants of Sir Matthew Fell, the man responsible for her hanging, delivering a chilling rebuke as she stands on the gallows awaiting her fate: ‘There will be guests at the Hall.’ ‘The Ash Tree’ is set in Suffolk, and a mere features in the grounds of the fictitious Castringham Hall; it’s not unreasonable to suppose that the now-vanished house across the park from James’s childhood home might have been the model for the story’s location.

Alongside the grave of Charles and Ann Mothersole I find the remains of a blackbird, dead a week or so and becoming one with the surrounding soil and oak leaves. Banding its leg is an identification ring from the Natural History Museum. Later, I learn the bird’s melancholy fate: ringed in Great Livermere as a fledgling the previous spring, barely moving from its place of birth.

Towards the back of the churchyard, beyond a dark rectangle of yews (which bring to mind the whispering grove from James’s story ‘The Rose Garden’), stands a spindly cross. This might be the memorial to his mother and father that James had erected. I look for the word ‘PAX’, which is meant to be inscribed on it, but can only make out the letters IHS at its apex: Jesus, saviour of mankind. The stone is crusted with pale-green moss, obscuring the writing on its base. I start to flake off the material with my fingernail in an attempt to expose further clues. There is an inscription, though it’s not easy to read – and something about the act of uncovering it feels wrong, like the sort of foolish feat an inquisitive scholar in one of James’s stories would do and later come to regret.

I decide to leave it a mystery.

Returning to where I parked my car by the front gate of the churchyard, I peer over a wall, through the rhododendrons on the other side, at a cream-coloured building. It’s James’s childhood home – a square, solid-looking place rising to three storeys, with plenty of rooms for the young James to have lost himself in on the occasions he was here and not away at Temple Grove prep school, on the outskirts of London between Mortlake and Richmond Park. This was followed by Eton, where in 1882, and already writing his own ghost stories (as well as indulging in more serious sixth-form study, including a love of the classics, ancient manuscripts and the architecture of churches), he passed his scholarship exam for King’s College, Cambridge.

I contemplate the chances of being allowed to take a closer look at the rectory, restyled as the new Livermere Hall and used as accommodation for expensive game-shooting trips, but decide that rocking up unannounced is unlikely to gain me a warm welcome and an offer of the full guided tour (I tried the same earlier, without success, at the farm neighbouring the derelict church of Little Livermere). Besides, the daylight is waning and the rain now falling more keenly. As I drive from the village, past the dark earth of countless ploughed-open fields, the final words of James’s last published story, ‘A Vignette’, resonate:

Are there here and there sequestered places which some curious creatures still frequent, whom once on a time anybody could see and speak to as they went about on their daily occasions, whereas now only at rare intervals in a series of years does one cross their paths and become aware of them?†

‘Lost Hearts’ was probably the second of James’s published ghost stories to be written (after ‘Canon Alberic’s Scrap-book’), finished at some time between summer 1892 and autumn of the following year. It appeared in print in the Pall Mall Magazine in December 1895, then in Ghost Stories of an Antiquary, his first collection of supernatural tales, in 1904.

By this point, James had been made a dean (of King’s) and, from 1893, the director of Cambridge’s Fitzwilliam Museum. In addition to an expert command of Latin, Greek and French, he also had a familiarity with German and Italian – and even a modicum of Hebrew and Danish. These formidable linguistic skills served him admirably: he was a noted scholar of the medieval, and of esoteric branches of study such as biblical apocrypha – the sorts of subjects the lone middle-aged protagonists of his stories specialise in. Now in his early forties – though always, perhaps, appearing a little older than his years – James was a tall, well-built man with dark hair (parted to the right) and rounded spectacles. His features were soft, apart from a strong, square jaw. He spoke quietly, often chuckling, often drawing on his curved tobacco pipe.

Photo (M. R. James) Hulton Archive/Stringer via Getty Images

I knock and enter the opaque-paned door to the Founder’s Library of the Fitzwilliam. Inside the architecture appears largely unchanged since James’s time, when the room acted as his office. Built in 1848, it houses ten thousand fine volumes in carved oak bookcases that stretch more than twenty feet up to the white, geometrically patterned ceiling. An imposing marble-surrounded fireplace dominates the room. It’s a place of work and study where today the museum’s manuscript department is based – something James would approve of, I’m sure. A young woman at a table is leafing through an oversized illuminated book of musical scores, the only sound apart from the occasional swish of turning pages being the background hum of a dehumidifier. It is a soporific, comforting space that sends me back to another time, another world – and it’s easy on this darkening winter’s afternoon to imagine the director at his desk, squinting through his glasses in the pooled light at one of the antiquated tomes that line the vast shelves.‡

James himself appeared rather indifferent to ‘Lost Hearts’, writing to his friend James McBryde in March 1904 that ‘I don’t much care about it.’ The same was not true of Monty’s feelings for the man who was to become the illustrator of his first collection of ghost stories, his affection rising from the page as he later described McBryde in glowing terms: ‘no one who, even when he supposed himself out of spirits, brought so much enjoyment into an expedition. A smile will never be far off when his friends speak of him …’

Photo by the author, reproduction by permission of the Syndics of The Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge

James McBryde was a decade younger than MRJ – the three initials were how James usually signed his own name, and how he was referred to by many acquaintances – arriving at King’s College, Cambridge from Shrewsbury in 1893 to study medicine (‘Natural Sciences’ as it was then known). The dashing McBryde came to be a close companion to James, joining him on summer cycling trips, including those to Denmark and Sweden that provided the setting for the stories ‘Number 13’ and ‘Count Magnus’. After completing his medical studies in tribute to the wishes of his late father (though caring little for the subject), McBryde took up a place at the Slade School in 1903 to commence his formal artistic training – a calling for which it is clear he had a considerable talent. Early in the following year, however, he became seriously ill with appendicitis, and a second attack followed in March.

During his friend’s recuperation, James welcomed the idea that McBryde should illustrate some of his stories for the book that was to become Ghost Stories of an Antiquary – stories James had previously read out on Christmas Eve, by the light of a single candle, to the assembled King’s choristers and his fellow academics and acquaintances of the Chitchat Society. In carrying on a loose tradition popularised by Charles Dickens, the Cambridge don became the unwitting new keeper of the seasonal, supernatural flame. In folklore, ghosts had long been linked with Christmas Eve – a night, like Halloween, in which the boundary between this world and the Otherworld, the realm of the spirits, is said to be thinned. And though the festive telling of ghostly stories clearly took place before Dickens – dark winter nights lend themselves to it – the Victorian writer had brought the practice into the mainstream through A Christmas Carol and the tales he published in his own weekly magazine, Household Words.

Perhaps the most effective of these is ‘No. 1 Branch Line: The Signalman’. It too was produced specially for Christmas, as was the 1976 BBC version directed by Lawrence Gordon Clark, the first of the ‘Ghost Story for Christmas’ films not to have been adapted from one of James’s stories. The Signalman features a superb performance from Denholm Elliott, whose terrifying vision of his future may well be the most frightening sequence in the entire strand. The story features three supernaturally foretold railway accidents, and it seems no coincidence that it was written the year after Dickens was himself an unwilling participant in such an event.

Illustrated London News, 1865 (Wikimedia Commons)

On 9 June 1865, returning from France through Kent en route to Charing Cross, the train he was travelling in came to a low viaduct at Staplehurst that was in the process of being repaired. Several carriages plunged off the tracks, killing ten people and injuring fifty, although the structure stood only around ten feet above the muddy stream below; at the moment of derailment Dickens was reading through the manuscript of Our Mutual Friend. As the writer and his mistress, the actress Ellen Ternan, were at the front of the vehicle in first class, they got off relatively lightly. However, Ternan suffered physical injuries that incapacitated her for weeks, while Dickens, who helped to comfort other passengers, was traumatised, and nervous of train travel thereafter. And, in an odd twist, his own death (resulting from a stroke) was to coincide with the fifth anniversary of the accident.

James McBryde completed only four drawings for Ghost Stories of an Antiquary. He died in early June 1904, five days after having his appendix operated on. James’s book was published at the end of that year, with his friend’s illustrations embellishing ‘Canon Alberic’s Scrap-book’ and ‘Oh, Whistle, and I’ll Come to You, My Lad’. In his preface James paid tribute to its illustrator: ‘Those who knew the artist will understand how much I wished to give a permanent form even to a fragment of his work.’ Despite his Victorian, repressed reluctance to display his emotions, Monty was devastated by the death of McBryde, picking rose, honeysuckle and lilac blooms from the Fellows’ Garden at King’s, and taking them with him on the train to the funeral in Lancashire.§ He cast them into his friend’s grave after the other mourners had departed.

Original illustrations by James McBryde (1874–1904) from the first edition of Ghost Stories of an Antiquary by M. R. James

James’s sexuality has long been the subject of speculation – he was a lifelong bachelor, and surrounded himself with close, often younger, male friends. Those searching for Freudian clues about his personal life might point to the lack of female protagonists in his stories, or note that when women do appear they regularly take the role of the fiend, like Mrs Mothersole in ‘The Ash Tree’. The academic Darryl Jones refers to the ‘mouth, with teeth, and with hair about it’ inside which Mr Dunning in ‘Casting the Runes’ unsuspectingly places his hand, in the nook beneath his pillow, as a ‘vagina dentata – a nightmare image of the monstrous-feminine’. A similar horror could be ascribed to the mouldy well-cavity and the guardian-thing it harbours (‘more or less like leather, dampish it was’) in ‘The Treasure of Abbot Thomas’.

Both of these examples may indeed, possibly, point to a fear of (or at least unfamiliarity with) women, and therefore may be indicative of James’s clandestine fears or desires. Undoubtedly, having spent his life in all-male academia, he was far more comfortable in the company of men. This stretched to an enjoyment of the rough wrestling-games of ‘ragging’ and ‘animal grab’ that he played at Eton and continued to engage in while at King’s – at the meetings of the TAF (‘Twice a Fortnight’) society, or at college Christmas Eve parties. James’s friend Cyril Alington, later the headmaster of Eton (while James was its provost), provides surprising evidence contradicting the image of James as a stilted academic who we might expect to shun such physical contact; he recalled another friend, St Clair Donaldson – the future bishop of Salisbury – rolling on the floor during one of these games ‘with Monty James’s long fingers grasping at his vitals’.

James’s tactile nature is reflected in his stories, in which the protagonists often experience the touch or feel of something that causes them revulsion, or, in the case of Stephen in ‘Lost Hearts’, wake to find his nightgown has been shredded in the darkness by the raking fingers of the ghost-boy Giovanni. However, it would be presumptuous to assume that these horrors result from some subconscious psychosexual terror experienced by James – they may have been chosen simply for their unpleasantness, or for their resemblance to the medieval visions of Hell garishly on display in the paintings of Hieronymus Bosch and Pieter Bruegel the Elder, and also prevalent in the manuscripts of that period and the biblical apocrypha of which James was such a keen scholar.

Detail from Dulle Griet by Pieter Bruegel the Elder (Wikimedia Commons)

Because it strikes me that an unexpected toothed mouth appearing beneath a pillow would be equally terrifying to any sleeper, regardless of whether they were a man or a woman, gay or straight.

Gordon Carey, a former King’s chorister and Cambridge student who was one of James’s closest later friends, told his son long after James’s death that he supposed Monty was ‘what would now be called a non-practising homosexual’.¶ However, a definitive answer to the question of the writer’s sexuality – something that is ultimately irrelevant in relation to our enjoyment of his stories – seems likely to remain unknowable.

The reticence about ‘Lost Hearts’ that MRJ voiced to James McBryde perhaps hints at the atypical nature of the tale. In some ways it’s grubbier and nastier than most of his stories – which might explain James’s apparent disdain for it.** One of its main characters is a child – and children rarely feature in his work. Before the action begins, the real devil of the piece, Mr Abney, has already lured two adolescents to his grand house, removing their still-beating hearts with a knife while they lie drugged before him, then eating the organs accompanied by a glass of fine port. He plans to confer the same grim fate upon his young orphaned cousin Stephen Elliott in a ritual attempt to attain special powers for himself: invisibility, the ability to take on other forms, and the capacity for flight.

I disagree with James’s own lukewarm opinion of ‘Lost Hearts’. The story is viscerally effective in exploring the loss of childhood innocence (and of the boundaries people will cross to achieve their aims), though I think the adaptation I happened upon on that distant Christmas Eve is in some ways the more frightening of the two versions: certainly the gypsy girl Phoebe and the Italian boy Giovanni make petrifying on-screen apparitions with their greyish-blue skin, yellowed teeth, weirdly hypnotic swaying, and those extraordinary claw-like fingers. The maniacal movement of Mr Abney – he’s usually filmed with the camera tracking him, or circling Stephen in the way a big cat circles its prey – was inspired by Robert Wiener’s fêted work of German Expressionism, The Cabinet of Dr Caligari. And, in the appearance of the two ghost children, I see echoes of another silent German classic, F. W. Murnau’s Nosferatu, in which Max Schreck’s depiction of the spindly-fingered vampire, Count Orlok, remains one of the most iconic images of the supernatural committed to celluloid.

Yet, above all in the small-screen version, it was the ghost-boy’s hurdy-gurdy music that I found most unsettling. The film had no budget for an orchestral score, with scratchy vinyl 78s from the BBC archives providing the unforgettable aural chills; the adaptation makes no attempt, however, to replicate the ‘hungry and desolate cries’ of the dreadful pair of ghosts, a savage detail in James’s original.

Ullstein bild Dtl./Contributor via Getty Images

‘Lost Hearts’ has its setting at Aswarby Hall in Lincolnshire – when James was writing still a real, extant country pile just south of Sleaford, twenty miles to the north-west of the Fenland market town of Spalding where I grew up (and where I first came across the story in the early hours of that Christmas morning). I cannot visit the hall, as it was demolished in 1951, the result of damage and neglect while under requisition during the Second World War; the parkland that is described so beautifully in the story, however, remains. The adaptation was filmed in twelve days, with Harrington Hall in the Lincolnshire Wolds taking the place of Aswarby. Another location in the far north of the county, the Pelham Mausoleum at Brocklesby Park, was used for one of its most atmospheric scenes – when Stephen visits the temple in the grounds with its haunting, painted glass ceiling of cherubs. The mausoleum, based on that of the Temples of Vesta at Rome and Tivoli, was built between 1786 and 1794 by the First Baron Yarborough as a memorial to his late 33-year-old wife Sophia.

The TV production of Lost Hearts ranged widely over my home county, moving south to shoot the unvarying agricultural vistas I was so familiar with; I would have recognised the landscape of the ominous opening scene, as Stephen’s carriage emerges from the morning haze of a long Fenland drove, passing vast fields where the ghost children wait.†† This premature appearance of the two grey-skinned horrors is one of the film’s weaknesses, for it raises too many questions about their motivation, and their foreshadowed knowledge of future events; in this way, at least, I think James’s original, where the spirits are portrayed as forces of vengeful hunger, works better. But the hurdy-gurdy music of the film, the wonderful visuals of its ghosts, coupled with Joseph O’Conor’s predatory Mr Abney – and of course the circumstances in which I first encountered it – means that the adaptation retains pre-eminence for me.

It has an added layer of poignancy, I now discover: the child actor Simon Gipps-Kent, who conveys Stephen’s likeability and wide-eyed terror with such effectiveness, died fourteen years after the film was made from a morphine overdose, aged twenty-eight.

From the dreaming spires, I head north-west through the drizzle and darkness, edging my way the last few miles along puddle-filled minor roads. Then, through an attractive village, an open gate and a gravel driveway, until the sturdy walls of one of the oldest continually inhabited houses in the country loom above me. It’s not quite the opening of Lucy M. Boston’s The Children of Green Knowe, in which the main character comes to his great-grandmother’s – a place modelled on this building, Hemingford Grey Manor – in the middle of a flood of near-biblical proportions. But in terms of atmosphere it comes close, evoking the scene where Toseland reaches the house by boat – one of the most magical arrivals in children’s literature:

Illustration (‘Watery Arrival’) by Peter Boston from The Children of Green Knowe, reproduced here by kind permission of Diana Boston

They rowed round two corners in the road and then in at a big white gate. Toseland waved the lantern about and saw trees and bushes standing in the water, and presently the boat was rocked by quite a strong current and the reflection of the lantern streamed away in elastic jigsaw shapes and made gold rings round the tree trunks. At last they came to a still pool reaching to the steps of the house, and the keel of the boat grated on gravel.

Published in 1954, The Children of Green Knowe is another book I encountered through its BBC adaptation, which aired in four half-hour teatime episodes from late November 1986. As it was my second year at grammar school I was perhaps a little too old to be watching it – certainly the cooler boys in my class wouldn’t have admitted to doing so. However, I definitely wasn’t the only one, with my friend James gaining the nickname Tolly due to his perceived likeness to the central character (Tolly is the familiar form of Toseland). The name stuck for a while, and as I view the series again now the face of the young actor, Alec Christie, who played the main role, has become inseparable in my memory from that of my classmate.

The Children of Green Knowe is the first of six children’s novels set around the eponymous twelfth-century house of its title. Born in 1892, Lucy Boston did not start writing the series until she was in her sixties; by then she had been living in Hemingford Grey, twelve miles from Cambridge, since 1937, having purchased the riverside manor after the failure of her marriage. The house (and its topiary-strewn garden) features at the heart of all of the books, with the spirits of its former inhabitants offering a usually reassuring presence.‡‡

The Children of Green Knowe commences with seven-year-old Tolly travelling, like so many characters in bygone children’s fiction, alone by train. (John Masefield’s The Box of Delights, filmed two years before by the BBC – and also avidly watched by my younger self – is another.) Tolly, however, breaks one of the apparent rules of this kind of story by not being an orphan – his parents are in Burma and he’s been summoned from boarding school for Christmas by his great-grandmother, Mrs Oldknow, whom he has never met. The wise, elderly lady seems a version of what Lucy Boston herself was to become – she spent the rest of her days in the manor, where she passed away, aged ninety-seven, in 1990.

Tolly is entranced by the house and his ancient relative’s tales of the past, which seem to come alive in the manifestations of the three benign ancestral Oldknow children, Toby, Linnet and Alexander. Victims of the Great Plague of 1665, they appear to him, alongside various tamed spectral animals and birds, when the whim suits, and Tolly pieces together their lost existences from the fragments they reveal about themselves. More prosaically, the young Toseland might be reconstructing the children’s lives in his head from the stories his great-grandmother tells him and the family artefacts she shows him. In any case, The Children of Green Knowe is a magical piece of writing about imagination and what it is to be a child.

It’s also a book that captures the weather in an almost touchable way – from its opening flood to the dramatic later blizzard, both of which were drawn from Lucy Boston’s memories of the devastating winter of 1947. Harsh heavy snowfalls were followed, that March, by the worst flooding ever recorded along Britain’s east coast, affecting a hundred thousand homes and turning the Fens into an inland sea. It was a transformation which Boston describes in her recollections of Hemingford, Memory in a House:

It was like trying to shovel away the sky. The flakes were huge, purposeful and giddy, fantastic to watch when we sat inside. They descended on the garden, and through their rising and falling play one could glimpse the steady disappearance of all known features. The frozen moat was filled up level with its banks, the big yews were glittering pyramids rising from the ground; drifts changed all contours.

I’m shown around the manor by Diana Boston – the wife of Lucy’s late son Peter, who etched the Green Knowe books’ striking white-on-black scraperboard illustrations and line drawings. The atmosphere of the place hits me the instant I enter. Diana’s enthusiasm for the house and its story is palpable. She gets me to don a pair of linen gloves, so I can handle the numerous intricate, but now fragile, quilts that Lucy Boston also worked on; these home-made treasures feature at the core of the second novel in the series, The Chimneys of Green Knowe. I have to admit my ignorance at this point, as Diana has assumed my fandom extends to every detail of the stories. At the time of my visit I have read only the opening title and have somewhat vague, thirty-year-old memories of its action.

She seems a little disappointed in me.

I do, however, vividly remember Toby’s carved wooden mouse, which Diana takes down from a high shelf and places in my hands – I run my thumb over the comforting smoothness of its dark wood, surprised by its weight. It is exactly like its illustration in the book (executed more than sixty years ago by Diana’s husband), and happens to be the very artefact used in the television adaptation.

We head to the first floor’s imposing music room. Here, during the Second World War, Lucy held evening recitals for airmen from the nearby base – but because she was an eccentric outsider and fluent in German, many of the locals had suspicions that she was spying for the enemy, rather than doing her morale-boosting bit for the war effort. The men sat on cushions in the church-like alcoves as the industrial-sized trumpet of the gramophone crackled out its sound. Diana puts a record beneath its needle now, to demonstrate: the effect on the room is transformative, almost placing me among the milling throng of blue-suited young men to whom this steadfast, ancient house must have seemed such a place of sanctuary compared to the uncertainty of their own impermanent prospects.

We climb the narrow staircase that leads to the attic. The room at the top is dominated by a black-maned wooden rocking horse, conjuring for me the opening credits of the television series in which the camera circles the horse in close-up while the woodwinds, violins and harp of the main theme swirl in accompaniment.§§ This is the bedroom in which Tolly sleeps, and is a near facsimile of the one described in the text. As the two of us stand there and Diana recounts details of the furniture, something odd happens. A hardback novel with no dust jacket seems to propel itself, with considerable energy, onto the floorboards from the low, built-in bookcase on the wall behind the horse. Her little brown terrier, who has been following us on the tour, saunters across and sniffs it.

‘What was that?’ I ask.

‘These sorts of thing happen here sometimes,’ Diana says, picking up the book and replacing it.¶¶

I’m not someone who claims to have any predisposition to such things, and I have little experience of similar incidents, but the happening is not a frightening one and seems in keeping with the location. I suppose my rational explanation would be that our footfalls caused a vibration that dislodged the already unbalanced book, but even so the force of its flight was unsettling. The cynic in me wonders for a moment whether Diana has an elaborate mechanism to activate such a trick that she uses on all wide-eyed visitors – but I know this isn’t actually the case. Indeed, Lucy Boston comments in her memoir:

Meanwhile the house continued its own mysterious life and from time to time sent feelers out from its darker corners, such as slight poltergeistic displacements, footsteps up the wooden stairs, wandering lights, voices, etc., but so much immediate and dramatic human life filled the place that irrational trifles did not get much attention.

Later, in the music room, we sit as Robert Lloyd Parry, a Cambridge actor and M. R. James devotee with a more than slight resemblance to Monty, reads two of the scholar’s ghostly tales by candlelight to a now-assembled audience.*** I am transfixed by MRJ’s words (and Lloyd Parry’s performance), though a growing sense of weariness seems to have taken hold of me for some reason – the effect of all the Manor’s encroaching history, perhaps? I feel a little like Tolly midway through The Children of Green Knowe, after his great-grandmother reveals to him that the house’s three elusive young visitors are long dead:

He must have known of course that the children could not have lived so many centuries without growing old, but he had never thought about it. To him they were so real, so near, they were his own family that he needed more than anything on earth. He felt the world had come to an end.

Afterwards, I traverse the monotony of the moon-risen Fens in near silence, not wanting the radio to interrupt the drumming of the rain and the hypnotic drone of my car’s engine. As I pass a stand of willows that lines a deep dyke, a winter moth – the hardiest of our lepidoptera – flutters skywards, luminous in my headlights.

Another lost heart.

* (#ulink_86090d9c-2ffd-53c2-8d5d-939d184d6d03) There are, perhaps, wider sociological factors as to why grand houses and their surroundings feature so prevalently in the stories of James (and other writers) – historically, ghosts have seemed largely a concern of the two extremes of British society, with belief in them concentrated among the upper and working classes. Roger Clarke’s A Natural History of Ghosts makes a neat case for these polarities: ‘Your middle-class sceptic would say that toffs like ghosts because it is a symptom of their decadence, the plebeians because they are ill-educated.’

† (#ulink_8434d13e-114e-588f-a358-0b309f7e87cf) Written in 1935 and printed posthumously in 1936, ‘A Vignette’ is the only one of James’s works to reference Livermere and his childhood home directly. The apparently autobiographical tale tells of a malevolent, haunting face glimpsed through an opening in the rectory’s wall.

‡ (#ulink_c21e420a-8bdc-5bf8-bc16-6c07741c9def) It’s tempting to think the room inspired ‘The Tractate Middoth’. But the primary setting of James’s story (published in 1911) is Cambridge University’s old library – today the library of Gonville & Caius.

§ (#ulink_3e6ad431-d222-5024-a849-b3c626f4dafa) That same month McBryde’s wife Gwendolen gave birth to a daughter, Jane, with James taking up the role of her guardian; he wrote his sole children’s book, the Narnia-esque The Five Jars for her, and remained in close contact with the pair for the rest of his life.

¶ (#ulink_607093d4-2916-5e74-a1bd-1e2860ff724e) It must be remembered that the Labouchere Amendment of 1885 had added a new layer of homophobic persecution to British society, criminalising ‘gross indecency’ between men, as Oscar Wilde would discover to his cost; it was not until 1967 that these laws were partially repealed, and only in 2004 (in England and Wales) that they were fully abolished.

** (#ulink_ccbc99ae-05e5-52bb-8e35-6db89117128b) In his 1929 essay ‘Some Remarks on Ghost Stories’ James comments: ‘Reticence conduces to effect, blatancy ruins it, and there is much blatancy in a lot of recent stories.’

†† (#ulink_8b7992d1-5048-5e03-a00a-4306241ccf51) Although he spent so many of his seventy-three years on the fringe of the Fens, James’s stories, with the exception of the ‘The Fenstanton Witch’ (which was unpublished in his lifetime), are not explicitly set in this flat farmland world. For an excellent example of a truly Fens-located tale, R. H. Malden’s ‘Between Sunset and Moonrise’ is difficult to top. Malden was a fellow Kingsman and an acquaintance of James; his single collection of supernatural stories, Nine Ghosts, was brought out by MRJ’s publisher Edward Arnold during the Second World War. Its dustjacket made the grand claim: ‘Dr James has found his successor.’

‡‡ (#ulink_4f682ce8-543a-5a00-9cda-5cf297609147) Except in the fifth of the series, An Enemy at Green Knowe, which gives us the malingering trace of Dr Vogel, an ominous seventeenth-century alchemist not unlike Mr Abney from ‘Lost Hearts’.

§§ (#ulink_cdce6fa3-0c0e-5081-98aa-8a8de0bcab56) The adaptation of The Children of Green Knowe wasn’t actually shot at Hemingford Grey Manor, but at the moated Crow’s Hall, near Debenham in Suffolk. Although the production team borrowed Hemingford’s rocking horse, they ended up using a near-identical one with a blonde, not dark, mane.

¶¶ (#ulink_10ad20c4-31a8-5df4-bf9b-10d5f2acc9f1) When I later examine the solid-feeling shelves, I find they contain first editions of Alan Garner’s Red Shift and The Owl Service – two more important books from my childhood in which the past parallels the present. Neither, however, was the volume that flew out into the room; its identity must remain a mystery, as in the excitement I forgot to check.

*** (#ulink_c1f1e419-9d53-5321-8de3-e03599cf6f6d) Lloyd Parry provides the introduction to Lucy Boston’s posthumously published collection of stories written in the 1930s, Curfew & Other Eerie Tales; the title piece is particularly effective, along with the menacing water tower of ‘Pollution’.

Chapter 2

DARK WATERS (#uf97dc8e2-8fb1-5d72-a832-179bd823c5ec)

Something of a dread feeling starts to rise inside me as I cross the Great Ouse, a mud-edged monument to river engineering that in 1981 became home for a few days to a disorientated immature walrus that was eventually repatriated by air to Greenland. At the roundabout a few hundred yards past the bridge, close to where King’s Lynn’s now-demolished sugar beet and Campbell’s Soup factories once formed distinctive waymarkers, I turn my car onto the A17. I’m slipping back in time, back to my childhood, though time itself has seemed to slow as the traffic is moving at a slug’s pace, the line of cars in front of me having their progress curtailed by an inevitable tractor. Elsewhere, such hold-ups at least allow drivers space to appreciate their surroundings, but here, on a soot-grey day, there’s little to savour, just endless brown fields that merge into the horizon, broken up by occasional mean stands of poplars or ugly, asbestos-roofed agricultural buildings.

It’s an artificial, man-made landscape, reclaimed in part from the sea. We learnt about it at school, about Cornelius Vermuyden and the Dutch-led drainage of the seventeenth century, and of the earlier history of this ague-ridden backwater: the watery world where in 1216 King John is said to have lost his royal treasure on an ill-fated crossing of one of the estuaries of the Wash, having a few days before in King’s Lynn contracted the dysentery that would shortly kill him; or of the Anglo-Saxon rebel Hereward the Wake who led Fenland resistance to the newly arrived Normans, but was more familiar through having lent his name to the Peterborough-based radio station my classmates and I would listen to – in particular hoping they’d read out the name of our school on a snowbound day and that it wouldn’t be opening, a rare mythic event that actually came to pass on two occasions. Mostly though, the story of the area’s past is vague in my mind, like the inconstant lie of the land in the days prior to pumping stations. Even my own connections with the region seem increasingly tenuous, liable to be leached away by one of the local rivers: the Great Ouse, the Nene, the Welland. Or the River Glen, which my grandfather – a real-life incarnation of a character from Graham Swift’s Waterland – lived alongside.

Waterland was published in 1983 and was shortlisted for the Booker Prize in the same year. It is a novel about the forces inherent in human nature that tear people and families apart, how past events haunt the present. But, above all, for me it’s a book about the unnerving flat landscape of my youth. Though I must qualify this, because it would be wrong to regard the Fens as forming a solid, distinctive whole; the country of my childhood had its own boundaries based upon the places we’d visit regularly as a family, stretching a varying number of miles in each direction from our house, but outside of which the more removed outposts of flatness seemed alien and otherworldly. One such locality that we occasionally passed through was the tiny cluster of residences that formed the village of Twenty. In 1982 it acquired a new black-lettered sign that sat below its official name – ‘Twinned with the Moon’ it read; soon afterwards some local joker spray-painted the retort ‘No Atmosphere’ beneath.

In my reading of the novel, Waterland has its setting among the ‘Black Fens’ beyond Wisbech, a town which is itself reworked by Swift into Gildsey, with the real Elgood’s brewery standing in for the book’s fictional Atkinson’s. Despite being only a forty-minute drive from my home, Wisbech was an unacquainted place, less familiar to me than the geographically more distant London, which most years we would make a pilgrimage to on the train. Wisbech was merely somewhere we skirted on visits to Welney, where my mother took us to watch the winter gatherings of wild swans that sought refuge on the dark fields – terrain only slightly more hospitable than their native Iceland and Siberia.

Thomas Bewick, the eighteenth-century illustrator and author of the landmark History of British Birds, whose surname is commemorated by those squat-necked Arctic swans we would watch feeding on potatoes on the floodlit washes, also features tangentially in M. R. James’s story ‘Casting the Runes’. A victim of the story’s black-magic curse is sent in the post one of Bewick’s woodcuts that ‘shows a moonlit road and a man walking along it, followed by an awful demon creature’. If he has not concocted his own work by Bewick, James is most likely referring to the same tailpiece vignette that so disturbs the young Jane Eyre in Charlotte Brontë’s novel – a tiny extraneous illustration tucked into the blank space at the end of the 1804 ornithological tome’s chapter on the black-throated diver.* According to Brontë’s heroine, Bewick’s terrifying etching depicts a ‘fiend pinning down the thief’s pack’. And though there’s nothing that necessarily identifies the man as a law-breaker, the act of carting a heavy bag down a dark country lane does seem suspicious; the attached medieval-looking winged devil that’s doing its best to pry open the contents of the sack does little to assuage our suspicions that the bearer has been up to no good and is getting his hellish comeuppance.

The narrator of Waterland, Tom Crick, is a history teacher who is being encouraged to take early retirement due to budgetary restraints at his school. ‘We’re cutting back on history,’ his headmaster drily informs him, though ultimately it’s the mental breakdown of his wife that speeds the process along. A precocious boy in his class questions the point of learning about what has gone before: ‘What matters,’ Price declares, ‘is the here and now. Not the past.’ So, in order to demonstrate how history does still result in consequences for the here and now, Tom Crick begins to tell them of his own eddying past, the history of the watery landscape of the ‘fairy-tale place’ of his youth.

Waterland swirls between earlier days and the present, between the personal family dramas of the Crick and Atkinson families, and of the shifting silts of greater events such as the Napoleonic or First World Wars, whose eventual settling has a future effect on the imprecise borderlands of the far-off Fens. And, in a nod to Melville’s Moby-Dick, there is even an eight-page digression into the slippery natural history of the European eel, a species my grandfather, a keen angler, was well acquainted with.

I read the novel aged sixteen, a year or two after my brother had first turned its pages. It’s testament to the book’s power that my father, who usually distracted himself with the crime novels of Ed McBain or the thrillers of Frederick Forsyth (who he recalled meeting when they both worked in King’s Lynn at the end of the 1950s), and my grandfather – more comfortable with the westerns of Louis L’Amour – both seemed to take to it. For me, I think (and probably for them too), Waterland’s initial magic came from its setting; although its events largely occurred in a time well before I was born and in a skewed version of a place some twenty miles distant, it was still a landscape I felt I knew – and a landscape I’d never seen depicted in fiction before.

The key attraction, however, was that the Cricks were lock-keepers. Because Grandad had been one too, looking after the antiquated sluices at the confluence of the Welland and the Glen, and at the terminus of the Vernatt’s Drain. In common with the Cricks of the novel, Nan and Grandad lived in a riverside cottage that came with the job. It too was a fairy-tale dwelling of sorts, located in a place whose own name was something of a misnomer: Surfleet Reservoir (though Seas End on maps), the latter word referring to the ultimately failed eighteenth-century plan to divert river water into an artificial lake to aid the drainage of local farmland. My grandparents’ post-war brick bungalow, a veritable palace among the nearby wooden holiday chalets and ramshackle fishermen’s huts that lined the Glen, was where my mother spent her teenage years before she left to marry my father beneath the leaning steeple of the main village’s church, moving six miles upriver to the house where I grew up. ‘The Res’ (as locals still refer to it) was an odd enclave populated by weekenders who moored their boats on the seaward side of the sluice – a deep tidal channel fringed by tall reeds – from where they would head out for a spot of sea fishing, or others who preferred to spend the summer sitting outside their chalets chatting to their neighbours while their children played in the river. By all accounts the place had a distinct sense of community back then, and even today has a different feel to the rest of the uniform, arable-dominated area – bringing to mind some timeless Dutch canal-side idyll.

My grandparents departed this watery haven on Grandad’s retirement, moving to a ground-floor 1970s council flat in nearby Spalding fitted with wide doorways, a high-seated toilet, and red pull-cords that would summon the local old people’s warden in an emergency. The freedom of the lock-side home I cannot remember the inside of (I would have been two when they left it) was exchanged for more practical – but more humdrum – disabled-friendly accommodation that could better cope with Nan’s ongoing, crippling physical deterioration from rheumatoid arthritis.† As her condition worsened she developed a complete reliance on my grandfather who, in a strange role reversal for a man born in 1909, became her chief carer and cook, lugging her into her wheelchair to transport her to the bathroom and bedroom. Occasionally, the pair of them would argue with a causticity that now, I think, was borne out of Grandad’s frustrated inability to improve the situation. But, at other times, there was a tenderness in the way he gently pipetted artificial tears into her desert-dry eyes.

I follow the familiar route that hugs the river and leads away from my home town – I can still recall every curve even after all this time. This was the way I would ask my parents to come if we were returning from Peterborough of an evening, in the hope I’d spot an owl sitting on one of the fence posts strung along the bottom of Deeping High Bank. Sometimes Mum would pick me up from school and drive Grandad and me at dusk over the undulating road, while we watched through the windows for the silent-winged birds. In my formative years I claimed a kind of ownership of the place, mistakenly believing it was named ‘Deeping Our Bank’ – for the hours we spent here, it might as well have been.

On the face of it there’s not much to get excited about: the first stretch skirts a grass-covered strip to the left and wide fields of crops to the right, while a barbed-wire fence borders the roadside ditch. Today it’s empty, but over the years various birds of interest alighted here before us: a pair of stonechats, neat little passerines, usually took up winter residence; once, a russet-barred sparrowhawk gripped a bloodied linnet in his talons; and in spring, Pinocchio-billed snipe crouched on the wooden posts in full view, their cryptic brown plumage offering no camouflage against the green of the backdrop. But the highlight was the ghost-lit barn owls that fluttered ethereally in our headlights, or materialised, seemingly from nowhere, in the late afternoon sunshine.

Always you wanted owls.

Past where the road jinks to the left and twists up the bank, bringing the river into view, is a pale-bricked barn that looked out of place, like some Spanish mission picked up and transposed to the middle of this flatness. Just beyond, tucked behind the bank, is a pond. We rarely saw anything on it – except once, when Mum braved treacherous snow on one of the fabled occasions when school was closed to drive the two of us along the track. The river was frozen solid, but not the pit: a redhead female smew, a small, toothed diving duck from the continent, had found the last ice-free stretch in the vicinity.

That day sits in my memory like one of my favourite childhood books, Susan Cooper’s The Dark is Rising – the second (and arguably best) in the five-title series of the same name. The 1973 children’s novel followed eight years after the Cornwall-set Over Sea, Under Stone and, in truth, feels very different and aimed at an older audience (Cooper had not originally planned on it being part of a series). It dispenses with the child leads from the opening book (though they feature again later), retaining only the wizard Merriman – King Arthur’s Merlin. What we do get in The Dark is Rising, however, is the arrival of eleven-year-old Will Stanton, soon to discover that he’s the last of the Old Ones, on the side of the Light and tasked with keeping the forces of Dark at bay in a Manichaean struggle. It is a book I loved when I first read it (I would have been a similar age to its central character), especially its depiction of the longed-for snowy Christmas that renders its time-shifting Thames Valley setting into a magical, albeit malevolent, wilderness. It’s a remarkable evocation of the wintry English countryside (reminiscent of the snow in The Children of Green Knowe), particularly when you learn that Cooper left England for Massachusetts in 1963 with her American husband, writing all but the first of the sequence in either New England or the couple’s house in the British Virgin Islands:

The strange white world lay stroked by silence. No birds sang. The garden was no longer there, in this forested land. Nor were the outbuildings nor the old crumbling walls. There lay only a narrow clearing round the house now, hummocked with unbroken snowdrifts, before the trees began, with a narrow path leading away.

The scene reminds me of an earlier remembrance – the first time I saw proper deep snow, which had fallen on our garden overnight, anaesthetising the land and deadening all sound. Dad and I placed sticks in the snow-hills that the wind had sculpted, marking each one with a makeshift wooden trig point that reminded me of the mountains I longed to climb on the holidays we took, far removed from those flatlands.

The river is choppy, its banks a dirty green – there’s not a hint of snow in the sky – but I’m surprised by the new areas of wildlife habitat that have been cut alongside the water since the last time I was here: miniature inlets and scrapes, and a fledgling reedbed that would have been perfect back then for me to scan. In this same spot we watched transfixed on a correspondingly biting afternoon as a bare-chested man bobbed beside the river’s metal-reinforced far bank, a few strokes behind a paddling cow that he was trying to coax back onto dry land. My father knew him, he was a local farmer.

At the aptly named Crowland, a parliament of rooks is feeding amid a ploughed beet crop. I slow as I pass the town’s Civil War-ruined abbey, commemorated in a gothic sonnet by the ‘peasant poet’ John Clare, whose village of Helpston is only nine miles away, and whose wife spent her dying days in my home town:

We gaze on wrecks of ornamented stones,

On tombs whose sculptures half erased appear,

On rank weeds, battening over human bones,

Till even one’s very shadow seems to fear.

I stop in the heart of the nothingness, pulling onto the head of a dirt drove that branches off at a right angle to the main route’s undulating, cracked tarmac. It’s a bleak place, the very same stretch of road where, as teenagers, my friends and I would switch off our headlights while motoring at speed, briefly plunging ourselves into blindness. We were young and rash, fortunate not to suffer the classic Fenlander’s end and find ourselves drowning in two foolish feet of lonely water at the bottom of one of the ubiquitous steep-sided dykes that line those routes. A patch of ice at the wrong moment could have created a local tragedy and transformed us into a carload of ghouls.

If we had perished that way, perhaps one of us might have been fated to a curious, brief half-life like the main character Mary Henry, a church organist, in Carnival of Souls. At the start of the dreamlike, low-budget black-and-white 1962 movie she washes up on a sand bar more than three hours after the car she was a passenger in has plunged into the Kansas River, killing her two companions. She moves from the scene of the tragedy to Utah, where she finds herself stalked by a mysterious figure – ‘the Man’, played by the film’s director Herk Harvey – and a cast of undead dancers at the abandoned Saltair bathing pavilion that looms out of the Great Salt Lake’s fluctuating dried-out flatness, a landscape not unlike the Fens. The film’s eerie discordant organ music has a similarly hypnotic effect on Mary as the hurdy-gurdy of Lost Hearts does on Stephen. And, indeed, as both soundtracks seem to have on me.

‘It was though – as though for a time I didn’t exist. No place in the world,’ Mary says, after a fugue-like episode where she cannot hear external sounds or interact with her fellow townsfolk, before the song of a bird brings her back into the now. The young drowned organist, cast in the role of an awkward outsider, has been allowed to live out a brief window of her lost youth: events not actualised that should never have come to pass. Her limbo is a fleeting foretaste of what could have been.

Like my family’s own future among these formless fields.

Fear and paranoia were staples of growing up during the late 1970s and early 1980s. Made in 1973, the year I was born, Lonely Water is a public information film I vividly remember seeing at the cinema as a boy, before whatever main feature I’d been brought to see.‡ In recent years it has acquired a deserved cult reputation for its dark, warning content. Watching it now you’d think there was little danger that any child who saw Lonely Water would set foot on a riverbank or the shoreline of a reservoir ever again. Yet I did still go fishing with only a friend for company, and we often did end up messing about near the water, which makes we wonder whether the film’s message was lost on their target audience. Perhaps the known risk added an illicit thrill we found impossible to resist?