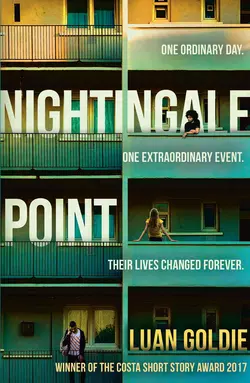

Nightingale Point

Luan Goldie

** THE DEBUT NOVEL FROM THE WINNER OF THE COSTA SHORT STORY AWARD **One ordinary day. One extraordinary event. Their lives changed forever.On an ordinary Saturday morning in 1996, the residents of Nightingale Point wake up to their normal lives and worries.Mary has a secret life that no one knows about, not even Malachi and Tristan, the brothers she vowed to look after.Malachi had to grow up too quickly. Between looking after Tristan and nursing a broken heart, he feels older than his twenty-one years.Tristan wishes Malachi would stop pining for Pamela. No wonder he's falling in with the wrong crowd, without Malachi to keep him straight.Elvis is trying hard to remember to the instructions his care worker gave him, but sometimes he gets confused and forgets things.Pamela wants to run back to Malachi but her overprotective father has locked her in and there's no way out.It's a day like any other, until something extraordinary happens. When the sun sets, Nightingale Point is irrevocably changed and somehow, through the darkness, the residents must find a way back to lightness, and back to each other.

LUAN GOLDIE is a primary school teacher, and formerly a business journalist. She has written several short stories and is the winner of the Costa Short Story Award 2017 for her short story ‘Two Steak Bakes and Two Chelsea Buns’. She was also shortlisted for the London Short Story Prize in 2018 and the Grazia/Orange First Chapter competition in 2012, and was chosen to take part in the Almasi League, an Arts Council-funded mentorship programme for emerging writers of colour. Nightingale Point is her debut novel.

Nightingale Point

Luan Goldie

ONE PLACE. MANY STORIES

Copyright (#ulink_3efc00a2-06e3-5605-9956-8295c6b6d3c8)

An imprint of HarperCollins Publishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

First published in Great Britain by HQ in 2019

Copyright © Luan Goldie 2019

Alyson Rudd asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Ebook Edition © July 2019 ISBN: 9780008314460

Note to Readers (#ubd41a0c9-1819-55b1-82c1-f2985e4bc529)

This ebook contains the following accessibility features which, if supported by your device, can be accessed via your ereader/accessibility settings:

Change of font size and line height

Change of background and font colours

Change of font

Change justification

Text to speech

Page numbers taken from the following print edition: ISBN 9780008314484

For Patrick

Contents

Cover (#u120d0596-211d-5201-af87-17ae0290b976)

About the Author (#ub8d3e6db-95ac-5b2c-bcd6-f83a3f794bec)

Title Page (#udfb4a90d-f8d9-57c0-b98b-89b5adbb094e)

Copyright (#ulink_795d8fe2-81f3-523c-b346-24c0a34b6e26)

Note to Readers

Dedication (#u9dd6da2e-193b-51d4-8eb6-669b67e946fa)

SATURDAY, 4 MAY 1996 (#ulink_ac0fd861-6259-5c1d-9280-0c744b951ea8)

CHAPTER ONE: Elvis (#ulink_b23bc850-a19b-5978-a2c3-c86b2bb8b042)

CHAPTER TWO: Mary (#ulink_5f60ccef-effc-5597-a786-9b2361066fc6)

CHAPTER THREE: Pamela (#ulink_31b00a79-2377-512f-89c2-993dbd3deab8)

CHAPTER FOUR: Tristan (#ulink_6fdcd4b1-9a50-540b-817b-91e0b3dc91db)

CHAPTER FIVE: Mary (#ulink_7a9e81e5-9319-5d66-90c0-81e554283935)

CHAPTER SIX: Pamela (#ulink_3f6c2683-b49a-5584-bed9-aec92d5ed8f5)

CHAPTER SEVEN: Malachi (#ulink_e3ef7457-e0b5-5ed1-9cc0-5ed8644b3b28)

CHAPTER EIGHT: Elvis (#ulink_ad149b40-e91c-5174-b41d-40a8df11ec51)

CHAPTER NINE: Tristan (#ulink_e24e2bae-6b96-5086-bcc7-7ef7cdc9a380)

CHAPTER TEN: Mary (#ulink_05505fb1-7a95-5bd8-96fc-ccbbca5577ca)

CHAPTER ELEVEN: Elvis (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER TWELVE: Pamela (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER THIRTEEN: Tristan (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER FOURTEEN: Malachi (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER FIFTEEN: Elvis (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER SIXTEEN: Mary (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER SEVENTEEN: Tristan (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER EIGHTEEN: Elvis (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER NINETEEN: Pamela (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER TWENTY: Elvis (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER TWENTY-ONE: Mary (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER TWENTY-TWO: Malachi (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER TWENTY-THREE: Mary (#litres_trial_promo)

AFTER (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER TWENTY-FOUR: Elvis (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER TWENTY-FIVE: Mary (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER TWENTY-SIX: Malachi (#litres_trial_promo)

TEN DAYS LATER (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER TWENTY-SEVEN: Tristan (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER TWENTY-EIGHT: Mary (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER TWENTY-NINE: Malachi (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER THIRTY: Tristan (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER THIRTY-ONE: Malachi (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER THIRTY-TWO: Elvis (#litres_trial_promo)

ONE MONTH LATER (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER THIRTY-THREE: Mary (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER THIRTY-FOUR: Tristan (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER THIRTY-FIVE: Mary (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER THIRTY-SIX: Malachi (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER THIRTY-SEVEN: Elvis (#litres_trial_promo)

THREE MONTHS LATER (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER THIRTY-EIGHT: Malachi (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER THIRTY-NINE: Tristan (#litres_trial_promo)

SIX MONTHS LATER (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER FORTY: Malachi (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER FORTY-ONE: Mary (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER FORTY-TWO: Elvis (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER FORTY-THREE: Tristan (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER FORTY-FOUR: Mary (#litres_trial_promo)

FIVE YEARS LATER (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER FORTY-FIVE: Jay (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER FORTY-SIX: Mary (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER FORTY-SEVEN: Malachi (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER FORTY-EIGHT: Tristan (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER FORTY-NINE: Elvis (#litres_trial_promo)

AUTHOR’S NOTE (#litres_trial_promo)

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS (#litres_trial_promo)

ABOUT THE PUBLISHER (#litres_trial_promo)

Saturday, 4 May 1996 (#ulink_fb1a1b40-2b96-54bd-838e-c569b00c1365)

The evacuation began this morning. No sooner had the bins been collected than the hundreds of residents from the three blocks that make up Morpeth Estate began streaming away in their droves.

Bob the caretaker sat in his cubbyhole on the ground floor, telling anyone who would listen that ‘it’s only a heatwave if it goes on ten days’. But no one listened, instead they asked when the intercom was getting fixed, if he knew the lifts were out and what he was planning on doing about the woman on the third floor who kept sticking a chair out on the landing. Moan, moan, moan.

Bob stubs out his cigarette and looks up at the grey face of Nightingale Point, smiling at the way the sun illuminates each balcony, every single one a little personal gallery, showcasing lines of washing, surplus furniture, bikes, scooters, and pushchairs. Towards the top a balcony glints with CDs held by pieces of string; a few of the residents have started doing it and Bob doesn’t have a clue why. He must ask someone.

Mary is amazed at how well it works. Who would believe that hanging a few CDs on the balcony stops pigeons from shitting on your washing? She had seen the tip on GMTV and immediately rushed to the flat next door to ask Tristan for any old discs. His music was no good anyway, all that gangbanging West Coast, East Coast stuff.

Mary wraps a towel around her hair. Her husband could show up any minute and the least she can do for him, after being apart for over a year, is not smell of fried fish. She switches on the TV, but the picture bounces and fuzzes. She doesn’t even try to understand technology these days, but heads next door to get Malachi.

Malachi sits behind a pile of overdue library books and tries to think of a thesis statement for his Design and the Environment essay that is due next Friday, but instead he thinks about Pamela. If only he could talk to her, explain, apologise, grab her by the hand and run away. No, it’s over. He has to stop this.

Distraction, he needs a distraction.

On cue, Tristan walks over with The Sun and opens it to Emma, 22, from Bournemouth.

‘Your type?’ he asks, grinning.

But Malachi’s not in the mood to see Bournemouth Emma, or talk to Tristan, or write a thesis. He only wants Pamela.

Tristan sulks back out to the balcony to read his newspaper cover to cover, just as any fifteen-year-old, with a keen interest in current affairs, would. After this he will continue with his mission to help Malachi get over Pamela, and the only way to do it is to get under someone else. Tristan once heard some sixth-former girls describe his brother as ‘dark and brooding’, which apparently doesn’t just mean that he’s black and grumpy, women actually find him attractive. So it shouldn’t be that hard to get him laid.

There’s a smashing sound from the foot of the block and Tristan looks over the balcony.

The jar of chocolate spread has smashed everywhere and Lina doesn’t have a clue how to clean up such a thing, so she walks off and hopes no one saw her.

Inside the cool, tiled ground floor of Nightingale Point, the caretaker shakes his head at the mess. ‘Don’t worry, dear, I’ll get that cleaned up. Don’t you worry a bit.’

‘Thanks,’ Lina says. A small blessing in the sea of shit that is her day so far. She hits the call button for the lift but nothing. ‘Please tell me they’re working?’

The caretaker cups his ear at her. ‘What’s that, dear?’

‘The lifts,’ she says.

He fills his travel kettle and shrugs. ‘I’ve logged a call but it’s bank holiday, innit.’

Lina pushes on the heavy door to the stairwell and sighs as she looks at the first of ten flights of stairs. ‘By the way,’ she calls back at the caretaker, ‘I think there’s kids on the roof again.’

Pamela loves being on the roof, for the solitude, for the freedom, and for the small possibility that she might spot, walking across the field below, Malachi. She has to see him today and they have to talk. Today’s the day; it has to be.

At the foot of the block the caretaker tips a kettle of water over a dark splodge on the floor and gets his mop out. Just another mess to clean up at Nightingale Point.

CHAPTER ONE (#ulink_55305665-6bc3-501f-a956-dcd3dd43acf8)

Chapter One ,Elvis (#ulink_55305665-6bc3-501f-a956-dcd3dd43acf8)

Elvis hates to leave his flat, as it is so full of perfect things. Like the sparkly grey lino in the bathroom, the television, and the laminated pictures tacked up everywhere reminding him how to lock the door securely and use the grill.

‘Elvis?’ Lina calls. ‘You want curried chicken or steak and kidney?’

Elvis does not answer; he is too busy hiding behind the sliding door that separates the kitchen and living room, watching Lina unpack the Weetabix, bread and strawberry jam. She unscrews the jar and puts one of her fingers inside, which is a bad thing to do because of germs, but Elvis understands because strawberry jam can be so tasty.

This is the nineteenth day of Lina being Elvis’s nurse. He knows this as he marked her first day on the calendar with a big smiley face. There are fourteen smiley faces on the calendar and five sad faces because this is when Lina was late.

She puts the jar of jam in the cupboard and returns to the shopping bags, taking out a net of oranges. Elvis hates oranges; they are sticky and smelly. He had asked for tomatoes but Lina said that tomatoes are an ingredient not a snack and that oranges are full of the kind of vitamins Elvis needed to make his brain work better and stop him from being a pest.

Lina’s face disappears behind a cupboard door and Elvis watches as her pink coloured nails rap on the outside. He likes Lina’s shiny pink nails, especially when her hair is pink too.

‘Elllviiiis?’ she sings.

He puts a big hand over his mouth to muffle the laughter, but then sees Lina has removed the red tin from the shopping bag – the curried chicken pie. He gasps as he realises he wants steak and kidney.

‘Bloody hell!’ She jumps and raises the tinned pie above her head, as if ready to throw it. ‘What the hell you doing? You spying on me?’

‘No, no, no.’

‘Elvis, why are you wearing a sweatshirt? It’s too hot for that.’ She slams the tin down on the counter.

‘Steak and kidney pie,’ he tells her. ‘I want steak and kidney pie. It’s the blue tin.’

‘Yeah, all right, all right.’

‘Can I have two?’ he tries, knowing his food has been limited. He is unsure why.

‘No, Elvis, that’s greedy. Now go. Get changed. You’re sweating.’

‘Get changed into what?’ he asks.

‘A T-shirt, Elvis. It’s bloody baking out; go put on a T-shirt.’

Elvis goes through to his bedroom and removes his sweatshirt. He stands for a moment and looks over his round belly in the mirror, moisture glistening among the curly ginger hairs that cover his whole front. When he takes off his glasses his reflection looks watery, like one of his dreams. He then pulls on his favourite new T-shirt, which is bright blue and has a picture of the King on it. It also has the words The King in gold swirly writing. He smiles at himself before going to the living room to sit on his new squashy sofa.

Elvis listens carefully to the steps Lina takes to make the pie: the flick of the ignition, the slam of a pot on the gas ring. Then, the sound he likes best, the click of her pearly plastic nails on the worktops. He loves all the flavours the tinned pies come in and he likes the curried chicken pie most days, but today he really does want steak and kidney.

‘Right, master, your pie is on the boil,’ Lina says as she walks into the living room. ‘Nice,’ she says, acknowledging his T-shirt.

‘Are we going to the bank holiday fair?’ He had seen posters for it Sellotaped up on bus shelters and in the windows of off-licences: Wilson and Sons Fairground on the Heath, 3–6 May. Helter Skelter, Dodgems, Ghost Train! He really wants to go.

‘Yeah, maybe when it cools down a bit.’ Lina flops on the sofa next to him and picks up the phone. ‘Go.’ She waves him away. ‘Why you sitting so close to me? I am entitled to a break.’

But Elvis is comfy on the sofa and he has already sorted the stickers from his Merlin’s Premier League sticker book and watered his tomato plants on the windowsills. He has already carefully used his razor to remove the wispy orange hairs from his face as George, his care worker, had taught him, and rubbed the coconut suntan lotion into his skin as he knows to do on hot days. This morning Elvis has already done everything he was meant to and now he wants to eat his steak and kidney pie and go to the fair.

Lina has his new special phone in her hand. Elvis loves his phone; it is his favourite thing in his new living room, after the television. The phone is so special that you can only make a call when you put money inside and you can only get the money out with a special key that George looks after. Beside the phone sits a laminated sheet with all the numbers Elvis will ever need: a little drawing of a policeman – 999; a photograph of Elvis’s mum wearing the purple hat she reserves for church and having her photograph taken – 018 566 1641; and a photograph of George behind his desk – 018 522 7573. Elvis is trying to learn all the numbers by heart but sometimes when he tries, he gets distracted by the fantastic noise the laminated sheet makes if you wave it in the air fast. Next to the phone is a ceramic dish shaped like a boat that says Margate on it. The dish is kept filled with change for when Elvis needs to make a call.

He watches carefully as Lina feeds the phone with his change and starts to dial, her lovely pink nails hitting the dial pad: 018 557.

‘Go and sit somewhere else,’ she snaps.

But there is nowhere else to sit apart from the perfect squashy sofa, so Elvis goes into the kitchen where he can watch and listen to Lina from behind the door. In secret.

‘Hi … I’m at work. Elvis is driving me nuts today,’ she says into the phone. ‘He keeps bloody staring at me … Yeah I know … Tell me about it … Ha ha. Yeah, true true …’ She slides off her plimsolls and pulls the coffee table closer, putting her little feet up on it. ‘But you know what my mum’s like, always busting my arse over something: look after your baby, wash the dishes, get more shifts. I thought the whole point of having a baby was that you didn’t have to go work no more … Exactly … Especially on a day like this. Bloody roasting out.’

Even from behind the door Elvis can see that the nails on Lina’s toes are the same colour as those on her fingers, but shorter. The colour looks like the insides of the seashells Elvis collected at Margate last summer. He likes Lina’s toes; this is the first time he has ever seen Lina’s toes. He likes them but knows he is not allowed to touch them.

‘Can I have a biscuit?’ Elvis asks as he comes out from behind the door, now peckish and unable to wait for the pie to boil.

‘Hang on. What?’ Lina rests the phone under her chin like one of the office girls at the Waterside Centre, the place where Elvis used to live before he was clever enough to live by himself in Nightingale Point.

‘Can I have a biscuit?’ he asks again.

‘I’m on the phone, leave me in peace.’ She tuts then returns to her call. ‘But look, yeah, I’m coming to the fair later. Soon as I’m done with the dumb giant here I’ll be down … I’ll get it; pay me later.’ Lina slides the rest of the money from the ceramic boat into her pocket.

Elvis pictures the laminated sheet of Golden Rules that hangs in his bedroom. Rule Number One: Do not let strangers into your flat. Rule Number Two: Do not let anybody touch your private swimming costume parts. Rule Number Three: Do not let anyone take your things. Lina is breaking one of the Golden Rules. Elvis must call George and report her immediately.

Lina picks up the laminated sheet of phone numbers and uses it to fan herself. It makes her pink fringe flap up and down, and Elvis wants to watch it but he also knows that he must report her rule break. George once told him that if he could not get to the house phone and it was an emergency, he could go outside to the phone box to make a call. The phone box, on the other side of the little field in front of the estate, is the second emergency phone. Elvis must now go there. He leaves the living room and slips on his sandals at the door. Jesus sandals, Lina calls them, but Elvis does not think Jesus would have worn such stylish footwear in the olden days. He opens the front door gently, quietly enough that Lina will not hear. Then, and only because he knows he is allowed to leave the flat to use the second phone for when he cannot use the first phone, Elvis steps out of flat thirty-seven and heads into the hallway of the tenth floor.

CHAPTER TWO (#ulink_d0fe831f-ff2c-57f5-9336-14b07fc21f5b)

Chapter Two ,Mary (#ulink_d0fe831f-ff2c-57f5-9336-14b07fc21f5b)

Ever since Mary woke up she has been feeling uneasy. And as the mother of two, grandmother of four, nurse of thirty-three years and wife to a fame-chasing husband, Mary knows what uneasy feels like. Her elbow has been twitching and she can’t shake the feeling that something is wrong. Something is coming.

She opens the pink plastic banana clip and allows her long greying hair to fall about her shoulders. Everything is cooked and cooling but she now needs something else to occupy her mind, to stop herself from worrying.

She covers the last plate – vegetable spring rolls – and stands within the tiny space of bulging cupboards and greasy appliances as she looks for a place to lay them. The worktops are already loaded with plates of food; each one gives off a different fried smell from under sweating pieces of kitchen roll.

‘Ah, too small, too small,’ she mutters. But no one could accuse Mary of failing to make the best use of her space. In each corner of the lino two-litre bottles of Coke are stacked like bowling pins; on tops of cupboards tins upon tins are stashed, heading slowly towards their expiry date; and on a small shelf above the fridge sits no less than seven boxes of brightly branded breakfast cereals. She buys them for her grandbabies. Though after a long shift on the ward she loves nothing more than to peel off her tights and eat two bowls of Frosties while lying on the sofa listening to The Hour of Inspiration on Filipino radio. Mary shuffles around some things, swears to finally get rid of the dusty sandwich maker and to stop buying five-kilo bags of long grain rice.

Her elbow. Twitch twitch twitch.

‘Stupid old woman,’ she mumbles. She knows she is being ridiculous, worrying too much about everything and nothing. She makes a mental list of her worries and tries to remember what the doctor on The Oprah Winfrey Show said to do with them.

‘You think of a worry, you cross the street,’ she says as she pictures the studio audience of determined, applauding, crying American women.

Mary thinks of each worry: talk that teenagers are gathering in the swing park at night to watch dogs fight; the cockroaches that continuously plague her kitchen; the smell of gas that sometimes lingers on the ninth floor; the woman from the top floor who was robbed of her shopping money last week as she got in the lift. It’s a long list.

‘Cross the street, cross the street.’ Mary waves her arms as she imagines each worry float off behind her. But then larger worries, those that are more likely to happen, these are things she can’t dismiss as easily, namely the imminent arrival of her estranged husband, David. Fifteen months he had been gone and then a call from Manila Aquino Airport two days ago: ‘My love, I am coming home, but I am on standby. You know what these airlines are like: locals back of the queue.’ She has heard this from him before, claims of him booking a ticket, being at the airport, getting on the next flight. Even once a call to say he had been diverted to Birmingham and would arrive the next day. She had wrung her fingers with anxiety for almost a week until he finally landed on her doorstep – their doorstep – with an excuse she now struggles to remember. For David, there is always some excuse, some distraction, some offer of money he can’t turn down. Whenever he is due to return home the world is full of people desperate for a poor Johnny Cash tribute act. Or maybe he is with one of his many floozies. Mary has never gotten over her own brother’s accusation that David had ‘a floozy waiting at the side of each stage’.

‘Cross the street,’ she says more weakly as she pictures David’s travel-weary face, greasy rise of hair and fake Louis Vuitton suitcase. ‘Cross the street.’ She cringes as she imagines David pulling her in for an obligatory married couple kiss. ‘Cross the street.’

‘Talking to yourself again, Mary?’ Malachi waves a hand as he enters the kitchen.

She felt bad for pulling him away from his studies, but also pleased for an excuse to check in on him and his younger brother Tristan. When had she turned into such a meddling old woman?

‘I’ve fixed the TV,’ Malachi says.

Mary takes the two small steps needed to cross the kitchen and throws her arms around his middle.

‘It wasn’t even broken.’ He shakes free from her arms and wipes the small beads of sweat on his dark brown skin. ‘Your aerial was unplugged. Tell the kids to stop playing behind the TV.’

Mary nods, knowing she will never tell her grandbabies any such thing – those perfect little girls would have to throw the TV out of the window before she dare aim a cross word at them. Each time they come to stay they leave her exhausted, and the small flat trashed, yet she can’t wait till they come again.

‘Why don’t you open a window in here? It’s twenty-four degrees already.’ Malachi leans over the sink and pushes on the condensation-streaked glass. It screeches loudly as it gives way, allowing the heat from outside to do battle with the steam from Mary’s cooking.

‘I have the vent on, see.’ She indicates the tiny, spinning, dust-covered fan. ‘You look tired,’ she says gently, keen not to nag the boy. ‘Too much study, study, study.’

He looks up at the window and undoes the top button on his shirt. Mary does not like the way he has taken to wearing collarless shirts; she watches MTV sometimes, and knows this is not a fashion among young people. She notices too, as he goes under the sink, that his trousers – muted green cotton with a sharp crease down the middle – are for a much older man.

‘What you looking for?’ she asks as he rummages around her collection of multi-buy discount cleaning products, fifty pack of sponges and long abandoned, but not yet disposed of, cutlery holders and soap dishes.

‘You need to oil your window.’ He twists the nozzle on a rusty can of WD-40.

‘Don’t worry about my window.’

He stops and looks down at her. His almond-shaped eyes search for something.

‘What?’ She touches her face, wondering if a stray Rice Krispie is stuck on her cheek.

‘You’re saying I look tired. You all right? You look a bit … frazzled.’

‘I worked forty-eight hours already this week – what do you expect me to look like? Imelda Marcos?’

Malachi blesses her with one of his rare smiles and then positions his knees into the two small free spots on the worktop. He seems more sullen than usual.

‘Are you okay?’ Mary asks as he squirts the window frame.

‘Yep. I’m always okay. Just hot and this smog, it plays havoc with my asthma.’ He jumps down and stares blankly across the kitchen.

Mary knows he’s still hung up on the blonde girl from upstairs. ‘Well, I’m glad you’re not still sad about whatshername.’

‘I have a hundred other things to think about,’ he snaps.

She was the first girl of Malachi’s Mary had ever met. He even brought her over for dinner once, one wet afternoon where they sat, with plates on their laps, eating chicken bistek.

‘Some things are not meant to be. I could see it from the start,’ Mary lies, for all she saw that afternoon was Malachi buzzing around the girl like she was the best thing since they started slicing bread. ‘I always know when couples don’t match. I even said it about Charles and Diana, but did anyone listen to me?’

‘I really don’t want to talk about this.’

Mary throws her arms up. ‘Me neither. Goodbye, Blondie. Plenty more pussy in the cattery.’

He wipes his face to hide his embarrassment and she’s pleased to see the tiniest of smiles emerge on his sad face.

‘Why’d you make so much food?’ he asks.

‘I told you, I need to work every day next week so I’m stockpiling. Like a squirrel.’ She wraps an old washed out ice-cream tub with cling film and hands it to him. ‘This is for your tutor.’ She had been sending food parcels to anyone related to Malachi’s education since his first semester of university. Anything to boost the boy’s chances. ‘The rest is for your freezer.’

‘Thanks. I appreciate it.’

‘And I appreciate if you put on some weight. What is this?’ She pinches the flesh of his side.

‘Ow.’

‘Heroin chic!’ she announces. ‘I saw it on GMTV. Teenagers with bodies like this.’ Mary holds up her pinkie finger. ‘No woman wants that, Malachi. You need to eat properly.’

She had looked in Malachi’s and Tristan’s fridge a few days ago and saw nothing but a loaf of value bread and jar of lemon curd. The freezer was even worse: a half empty box of fish fingers and two frosty bottles of Hooch, which Tristan explained were ‘for the ladies’. If their nan knew they were eating so poorly under Mary’s watch there would be murder.

‘Freezer, you hear me? Tell your brother he can’t eat, eat, eat all in one sitting. And why has he got zigzags shaved in his hair? Does he think he’s a pop star or something?’

‘You know what he’s like. He’s a little wild.’

‘He can’t afford to be wild.’ Mary tries to put the word in air quotes but uses eight fingers and makes a baby waving motion. ‘Too many riffraffs around here going wild like this.’ She makes a stabbing gesture and tries to look menacing, but her only reference point is West Side Story and she makes a dance of it.

Malachi puts a hand under a piece of kitchen roll and drags out a bamboo skewer of prawns. Mary slaps him.

‘Did you hear me say help yourself? Does this look like the Pizza Hut buffet to you?’

‘You just told me I need to eat.’

‘Not prawn. Too early for prawn.’ She turns her back to him as she rewraps the skewers. His eyes burn her; she must explain her snappy mood. ‘I need to leave my spare keys with you in case David gets in early. He’s on standby for a flight so could be here tonight, tomorrow or next week. Oh God.’ The reality of him arriving hits her again. It sends her elbow into overdrive.

‘David?’

‘Yes, David, my husband. Remember him?’ There’s a hysterical edge to her voice. She puts a hand on her forehead to save herself as Oprah has taught her. ‘I don’t even want to talk about it.’

‘I didn’t know David was coming back.’

‘No. But we didn’t know Jesus was coming back either.’

Mary takes her nurse fob watch from her pocket – a present from David on one of his rare jaunts back home. An obscure-looking Virgin Mary with oversized arms ticks around the clock, hung on a thick, gold link chain. Well, it was gold once, now it’s more silver, the shine, like everything else to do with David, rubbed away by the sweat and grime of real life. Quarter to twelve.

‘Mary?’ Malachi waves his arms to get her attention. ‘Hand me these keys then. I need to get back home.’

Mary nods as she looks in the junk drawer, rifling through papers, wires and replacement batteries for the smoke alarm until she finds the spare keys. Tristan had once attached a plastic marijuana leaf to them thinking it was funny. Mary had given him a lecture about the dangers of drugs but never bothered to remove the key ring.

She fusses with the catch on the watch as she pins it to her uniform, swearing to get it fixed. ‘You want some tea before you go?’ she asks Malachi.

He spins the keys around a long finger. ‘No, thanks. Too hot.’

‘You call this hot? It’s thirty-five degrees in Manila today.’ She lifts the kettle and gives it a shake before she flicks the switch.

‘Right,’ Malachi says. ‘I better get back to my books.’

He sulks off and she rolls her eyes at his constant grumpiness. But as she hears the front door close she stops cold. The twitch becomes a scratch. Something is wrong, for her feelings never are. Today, something horrible will happen.

CHAPTER THREE (#ulink_1e184b71-c8fe-5e7d-b394-477536d7899e)

Chapter Three ,Pamela (#ulink_1e184b71-c8fe-5e7d-b394-477536d7899e)

There is not a stitch of breeze on the roof of Nightingale Point. Today, up here is just as suffocating as being in the flat with Dad. Pamela places her new running shoes on the ground and holds onto the metal railing; her long rope of blonde hair falls forward and dangles over the edge. The sunrays hit the nape of her neck and she feels her skin, so dangerously pale and thin, begin to burn. She shifts her body into the shade of the vast grey water tanks and imagines the water as it rolls between them and into the maze of pipes around the block’s fifty-six flats. Pamela loves the roof. Since she returned to London a few days ago it’s become the only space Dad does not watch over her. Sometimes she wishes she was back in Portishead with her mum, just for the freedom from his eyes. But in a way being there was worse, because it meant Malachi was over a hundred miles away rather than two floors. At least here there is a chance she will see him, run into him in the lift, or bump into him in the stairwell.

Blood runs into her face as she leans further over the railings. Her head feels heavy. She wonders, not for the first time, how it would feel to fall from this spot, to flail past all fourteen floors and land at the bottom among the cars and bins. It would probably feel like running the 200 metres. Air hitting your face and taking your hair, your lungs shocked into working harder than you ever knew they could. Pink and yellow splodges dance in front of her eyes as she lifts her head. It’s coming up to noon, only halfway through another monotonous, never-ending day.

She assumes it’s other teenagers that repeatedly bust the locks on the door that leads up to the roof. They leave their crushed cans of Special Brew and ketchup-smeared fish and chip papers across the floor as evidence that they are having a life. She often fantasizes about coming up here at night, catching them in the throes of their late-night parties, tasting beer and throwing fag butts among the pigeon shit with them. If only Dad would let her out of the flat past 6 p.m. No chance.

The sky appears endless. Unnaturally blue today, almost unworldly, not a blemish on it apart from the single white smear of a plane.

Does she need to run back? Has it already been twenty minutes? She doesn’t care. What does time matter if you’re all alone? What difference does any of it make if you’re about to throw yourself from the top of a tower block? She takes three deep breaths but knows that she doesn’t have the confidence to do it. But the thought alone makes her feel like she has some edge on Dad, something that she can do without his permission.

In front of the estate people are living their lives: a child runs, the drunks drink, some girls sunbathe in pink bras and denim shorts, and a lone large figure in billowing purple crosses the grass at speed. Pamela tries to picture who the bodies are, how they would feel if they witnessed a girl fall from the building, their faces upon discovering her body bashed at the bottom. They would be traumatised, she thinks, for a while at least, and then her death would become another estate anecdote. The tale of the broken-hearted teenager with the strict dad. It would become just another story to get passed around the swing park and across balconies, along with tales of who is screwing who and which flat plays host to the biggest number of squatters.

Pamela wishes she could go for a run. She needs to clear her head. Surely Dad will let her out.

‘Please, one hour out,’ she rehearses. It sounds so feeble out loud, so knowing of a negative answer.

Her running shoes swing by her sides as she pads across the greyness in her socks. She steps over the glossy ripped pages of a magazine; a girl in a peephole leather catsuit stares back at her. The door bounces against its splintered frame as Pamela enters the building. Her world starts to shrink. With each step down to the eleventh floor the brightness of the unending blue sky disappears and the stairwell begins to close in on her. The concrete walls suck the air away until there is only the suffocating stink of other people’s lives.

‘Do you think it will be okay if I went out today? Maybe. Perhaps.’ Her voice echoes eerily; she feels even more alone. ‘I’m thinking of going out today.’ This time with more confidence. But what’s the point? He will say no. He will never trust her again.

She opens the door onto the puke-coloured hallway and the shouts and music of her neighbours. Outside flat forty-one she stops and rests her head on the security gate, takes a few breaths and then pulls it open. She looks down at the letterbox and for a moment feels like she has a choice. She could still go back to the roof. But, as always, the choice is taken away from her as the lock clicks from within and the front door swings open.

Dad fills the doorway; a fag hangs from the corner of his mouth. ‘You’re pushing your luck, girl.’ Patches of psoriasis flame red on his expressionless face. He’s put back on the same sweat-stained yellow T-shirt and army combat trousers from yesterday.

‘I was getting some air.’ She pushes past him into the dim, smoky living room.

He follows her, sits on the sofa and pulls his black boots on. ‘Air?’ He methodically ties up each of the long mustard laces. The woven burgundy throw falls from the back of the sofa to reveal the holes and poverty beneath it. ‘We got a balcony for that. I don’t wanna start locking the gate, Pamela, but if you’re gonna be running off every opportunity—’

‘I didn’t run off. It’s a nice day. I was on the roof.’

‘Well, I’ve heard that before. You can’t blame me for not trusting you.’

She rearranges the throw and stands back. She only wants an hour outside, just enough time to clear her head. So much can change in that time; like the day she first met Malachi. Dad had given her an hour then too, explained how grateful she should be for it. ‘More than enough time to go round the field and straight back home.’ She grabbed that time, and even though he was watching her from the window, she felt free as she ran loops around the frosty field.

The drunks, immune to the freezing temperatures of the morning, watched from their bench as she ran past them several times that hour. ‘You should be running this way, blondie,’ one called, while shaping his hands in a V towards his crotch on her last lap. They all laughed and she ran faster. She could always go faster and with time ticking she needed to get home before Dad came out for her. She cut onto the grass, slipped and fell awkwardly. It hurt straight away. Her ponytail caught the side of her face as she turned to check if the drunks were still laughing at her, but they hadn’t even noticed her fall. The dew began to seep through her leggings and she tried to stand, but buckled immediately with the pain.

‘Hey,’ someone called. ‘You okay?’ A tall man came running towards her and put out a gloved hand. ‘You really went down hard there.’

‘Yeah.’

‘Here, let me help you.’

As he helped her to a bench she tried to concentrate on the hole in his glove to stop herself from blushing.

‘You really do run out here in all weathers, don’t you?’ he asked.

‘Sorry?’

‘I live up in Nightingale Point. I always see you out here.’

He had seen her before. How had she never seen him? She tried not to stare, or lean into his arms too much.

Tristan Roberts came over too. He was from her school, one of those loud, obnoxious boys everyone seemed to know.

‘Oh, shit, did you break your leg?’

‘No, she ain’t broken her leg. This is my brother.’

They looked nothing alike.

‘Ain’t you cold?’ Tristan pulled the drawstrings on his hoodie tighter. ‘Running round out here? That’s long.’

She could see Dad coming across the field now, his face red from fatigue and panic.

‘I’m fine, really. Thanks. I need to get home.’ She tried to rise but the pain shot through and she winced. He grabbed her again; the pain was almost worth it.

‘Get off her. Pam.’ Dad was closer. ‘Pam, Pam.’ He pushed past Tristan and put his hands either side of her face. ‘I knew I should have been watching you. What happened?’

‘She’s all right, man, she just tripped, innit,’ Tristan said.

‘Who are you? Why are you two even near my girl?’

‘Dad, stop it. Tristan goes to my school.’

Tristan looked confused. He obviously didn’t recognise her. It confirmed she had no presence at her new school; she was nobody.

‘I’m Malachi. We live in the same block. We were making sure she was all right. That’s all.’

‘Well, she’s fine ’cause I’m here now, ain’t I?’ Dad snapped. ‘Come on. Let’s get you home.’ His grip on her arm was tighter than it needed to be. She could see Malachi noticed it too.

‘This looks bad, Pam. Don’t think you’ll be running again for a while.’ Dad looked relieved, happy because injuries meant she had no reason to go out.

Even now, with the injury long healed, he still won’t let her out, but then he has other reasons for wanting to keep her inside the flat these days. She pulls the curtains open and the room brightens, but even the sun’s glare is not enough to chase the perpetual gloom out.

Dad inspects his roll-up for life before roughly squeezing it onto a saucer. It’s from her nan’s set, cream with tiny brown corgis around the edge, once used for special occasions but now reduced to holding ash.

‘I’m going to the bookies,’ he says. ‘Will be back for dinner. We’ll heat up that corned beef.’

‘They’re fighting again,’ she says.

‘Who?’

‘Next door. Can’t you hear them?’

They stop for a moment to listen to the searing soap opera from flat forty-two that plays itself out so regularly. It sounds particularly theatrical today. What is the woman shrieking about this time? She always seems to be arguing with her teenage daughter over something. Pamela longs for that kind of relationship, one so freely volatile that you could scream and shout at a parent, rather than stand there and soak up their disappointment.

‘They been at it all morning,’ he huffs. ‘Their voices go right through me.’

Pamela tries to block out the domestic so she can focus on Dad, her own situation. She tries to assess his mood by the way he clears his throat and collects his wallet. She wonders at her chances of success and waits to pick her moment.

He looks straight at her. ‘Why you dragging those about?’ He nods towards the pair of pink and lilac trainers in her hands.

The tip of her ponytail tastes chemically; he always buys the cheapest shampoo.

‘I won’t go anywhere other than around the field. I promise.’

‘You’ve only been home a few days. You expect me to let you start running wild again?’ He holds his anger in so well, but she can see it behind his eyes, ready to pop like glass. ‘No chance. You’re staying in.’

‘You know it rained the whole month I was at Mum’s. I haven’t been out running in ages.’

He shakes his head again.

‘I want to go round the field a few times. It’s the middle of the day,’ she tries. ‘You can watch me from here.’

‘Told you. I’m going out.’ His keys jangle as he taps his pockets and walks away, her chances dissipating.

‘What about swimming? Can I go to the pool?’

He laughs. ‘Yeah, right, the pool. Why? You arranged to meet someone there, have you?’

‘No. Dad, please.’ She follows him into the hallway, not content to let it end there. She knows she’s already in trouble anyway. ‘So you expect me to stay in all day listening to that?’

The walls leak more cries from the quarrelling neighbours.

He checks the handle on his bedroom door: locked. ‘You can use the phone. Call one of your mates for a chat.’

‘I don’t want to chat. I want to go out. I want to run.’

He stops by the front door and gently takes her plait in one of his hands. ‘No.’ So calm. So fixed. ‘I don’t trust you out the flat. In fact, I don’t even know if I trust you to be alone in the flat.’ He lets the long plait fall and kisses her on the head.

‘What do you mean?’

‘Well, how can I be sure that the minute I go out your little boyfriend won’t come running up?’

‘Because I don’t have a boyfriend anymore. Remember?’

He holds her gaze but what can he say? He knows he ruined it for her; he ruined everything.

‘Dad?’

He turns to face her, keys now in his hands as he opens the front door. ‘Yeah? Come on, Pam, what you wanting now?’

I hate you. ‘Nothing.’

The door closes and she listens for the Chubb lock, but hears no footsteps. He’s still outside; maybe he will change his mind and give her permission to start living again. But then, seconds later, there is the distinct clank of the security gate and the crunch of it being locked: the confirmation that she will spend today locked inside her home. Trapped.

CHAPTER FOUR (#ulink_53004b07-ff22-5f9f-8abd-807260a9789a)

Chapter Four ,Tristan (#ulink_53004b07-ff22-5f9f-8abd-807260a9789a)

Tristan had already picked the clothes from the floor, stacked the videotapes and lined up his and Malachi’s trainers by the front door. He now sits on the window ledge, his place of choice, observing the world nine floors below him. He is wearing white shorts today, white T-shirt, white socks, white trainers, and a large cubic zirconia stud in his left ear. It’s a good look. He feels pristine. He wonders if he should hoover but decides against it, as nothing will make the carpet, so full of cigarette burns and bleach stains, look any better.

Malachi walks in and slumps himself back into the Malachi-shaped dent on the sofa.

‘So what’s wrong with Mary’s TV?’ Tristan asks his brother.

‘Nothing. One of her grandkids must have unplugged the aerial.’

Tristan laughs, once again glad that Mary never asked him to fix stuff around her flat. It’s one of the perks of having a brother like Malachi, who is not only the clever one, the tall one and the ‘traditionally handsome’ one, but also the one that can ‘fix stuff’.

‘Did she make you watch Ricki Lake with her?’ Tristan laughs. ‘Girlfriend, you need to get a new man, get a man with a job,’ he mimics in an American accent.

Malachi shakes his head and pulls a pile of books onto his lap.

‘Mal, you all right?’

‘I’m always all right.’ He holds his book in front of his face.

‘You’re proper squinting. You need glasses, man, stop denying it. Specs will complete this whole student look you’ve gone for.’

Malachi puts the book down and pulls some keys from his pocket. ‘Mary’s spare keys,’ he says as they slide across the table into a pile of papers. ‘Tris, if you drop out that window I can’t save you.’

‘You don’t always need to save me,’ Tristan snaps. ‘I’m almost sixteen – old enough to vote and go to war.’

‘You need to be eighteen to vote.’

‘Whatever. Don’t need my big brother saving me.’

Malachi always thinks he needs to play the hero, but looking at his outfit today he’s the one that needs saving. Where did he even buy a pair of green trousers? No wonder he can’t keep a girl.

Malachi starts writing a shopping list, like Nan used to, except Nan wouldn’t have subjected them to pasta five nights out of seven.

‘What?’ Malachi looks up from his list of cheap meals. ‘Why’d you keep staring at me?’

‘Nothing. Was thinking, we should go West End, man. Get some new clothes for summer and that.’

‘New clothes? Cool, right after I figure out how to stretch my last money over our meals for the week.’

‘You were a lot more generous with the old purse strings when you were getting some action.’ Tristan is fed up of Malachi’s sulking. It’s been going on for ages now. All over some girl. She wasn’t even that fit. Proper Plain Jane. No need to get so upset over her. Tristan would never let a girl mess up his head the way Pamela messed up Malachi’s.

He starts tapping a beat on the window and runs through his latest lyrics. ‘It’s Saturday, I’m out to play. Girls get ready ’cause I’m gonna pay, pay your way, so you can stay, in my bed, but I ain’t gonna stay. Yes. You like that one, Mal? I was born to do this, man.’

But there’s no applause from the one-man audience on the sofa, only another huff.

‘Pay your way, so you can stay, in my bed, we do it hard all day. So what you saying, Mal?’

Malachi raises his eyebrow. ‘Keep working on it.’

‘Ha. You coming out later?’ Tristan asks hopefully.

‘No.’

‘How comes?’

‘Busy.’

‘Ah, don’t give me that, it’s bank holiday weekend.’ He picks up one of Malachi’s plastic-wrapped library books. ‘The History of the Urban Environment. Hmm, looks like a riveting read. But I’m sure it can wait. Come on, come out with me.’

‘No.’

‘You seriously telling me you can’t take one day off from studying? Your brain gonna get stretch marks if you carry on like this.’ How long is Malachi planning on hiding out behind his books? It’s getting ridiculous. ‘You gotta get back to normal sometime. Whole estate’s gonna be at this fair up at the Heath. Plenty girls, Mal, plenty girls. Gonna keep me busy. Don’t expect me home early. Don’t expect me home at all. You can have the place to yourself, bring someone over if you want. Get a little study relief.’ He pumps his hips.

Malachi rubs his eyes and groans. ‘Tris, stop going on.’

‘Calm down, bruv. I’m talking about girls in general. I wasn’t gonna bring up Blondie.’

‘You just did,’ he snaps. ‘You and Mary are doing my head in with this.’

‘What?’

‘You’re both telling me to move on, yet you’re bringing her up every minute. Why can’t you both drop it?’

‘’Cause everyone’s fed up with you sulking about Pamela. Time to get over it. It’s time for a next girl. It’s time, bruv, I’m telling you. That’s why you need to come fair. You need to watch me in action.’ He stands up and performs his lyrics just as he would on stage. ‘Me settle down? You’re having a laugh. A pocket full of Durex, girl meet me in the car park.’

Malachi throws his books on the table. ‘Don’t you have somewhere to go?’

‘Nah, not yet. I’m tryna cheer your long face up. I even put up that hotness for you.’ Tristan nods over to the wall. Earlier he had taped up an A3 poster of Lil’ Kim lying spread-eagle across an animal fur rug. Now that’s the kind of girl worth having a broken heart over, not some skinny little blonde from the flats.

Tristan pushes the window open further, in need of air after working himself up with all his talent. Now relaxed, he takes his Rizla from his pocket and what’s left of his weed.

‘Quickest way to get over one girl is to move on to a next.’

‘Outside with that.’ Malachi jabs a thumb towards the front door.

‘You serious? The window’s wide open. You can’t smell it if I sit here,’ Tristan says, demonstrating how carefully he will blow smoke out of the window.

‘I don’t care. Take it out.’

‘Just ’cause you ain’t smoking no more. Why should I have to go out?’

‘Out.’ Malachi repeats as he begins flicking through his books.

‘Whatever.’ Tristan rubs his brother’s head roughly as he passes the sofa on his way out of the flat. Surely one of the benefits of having a twenty-one year old as your guardian should be that you can openly smoke a bit of weed at home. But no such luck with Malachi and that stick up his arse. Still, Tristan doesn’t mind getting out, jogging down to his much-loved spot, between the sixth and fifth floor, where he selects the middle step.

‘I’m more than a thug, girl get to know me, king of the block, T.H.U.G.’

He likes the echo of his voice in the stairwell and imagines how it would sound on a real microphone. He pictures himself in a recording booth, one headphone on, one headphone off, like the rappers in the videos, all his boys drinking in the studio, some girls dancing about.

‘Gimme a kiss, I’ll light up a spliff, take you to Oxford Street, buy you nice shit. Nah, don’t sound right.’ He looks again at his stingy stash. ‘Hard times, hard times,’ he mumbles.

Then he hears something, someone coming down the stairs. It stops. He cranes his neck to look up and down. Nothing. But there’s someone breathing. It feels like he’s being watched, maybe by one of those crazy girls from the youth club. He had stopped going after he got involved with one too many of them. Some even know where he lives; they’re probably stalking him. Though he wouldn’t mind being stalked by the girl with the red weave – she looked like the kind of trouble he could enjoy.

Again, the shuffle of feet, heavy, though, not like a girl. Footsteps. He looks up and down but can’t see anyone. He’s being paranoid, but it pays to be paranoid living around here. Last week some woman got her handbag nicked as she was getting out of the lift.

‘I’ll give that ghetto ghetto love, weed and sex, and some crazy drugs.’

‘No smoking in the stairwell.’

Tristan is startled. His papers flutter to the floor.

‘What the fuck?’ he shouts.

A man stands at the top of the stairs. He looks down at Tristan. He is tall and chubby, and has crazy bright ginger hair.

‘No smoking in the stairwell,’ he commands.

‘You what? You spying on me?’

‘No smoking in the stairwell,’ the man repeats, and his face breaks out into high red blotches. ‘It’s a rule. You cannot break the rules of Nightingale Point.’

‘Fuck off. Go. Go past.’

But the man stands there, straight-faced. ‘No smoking in the stairwell.’

There is definitely something off about him; he’s wearing a T-shirt with a picture of Elvis Presley on it, for a start.

‘Rule breaker. Rule breaker,’ the man chants.

Tristan pounces up the stairs and grabs the idiot by the sleeve of his T-shirt. The man is bigger than Tristan but unsteady on his feet and he topples down easily with a tug. He lets out a small cry as he falls, then grabs the bannister and pulls himself back to his feet.

‘Stop looking at me!’ Tristan shouts. ‘Move. Go before I chuck you down the next five flights.’

The man bends over to pick up his glasses. His grey shorts are too big for him and he gives Tristan an eyeful of his white fleshly arse cheeks before he runs off down the stairs.

‘Fucking retard.’ Tristan picks up his papers and returns to making the spliff. He empties his tobacco in and sprinkles the little weed he has left on the top. But he’s pissed off now. He has nowhere peaceful to call his own, except for this place in the stairwell, and now some dumb fucker wants to talk to him about rules and try to kill his vibe.

Tristan lights up and waits a few moments to enjoy his first puff. It takes him a while to chill out again but finally he relaxes into his familiar routine, lounging back on the step and listening to the muffled sounds of the block.

‘Oh, look who it’s not.’ Mary’s voice echoes from above.

‘Fuck,’ he mutters and rubs the spliff against the steps. ‘Didn’t hear you, Mary. Boy, you’re so silent. Like a ninja.’

‘What you doing, sunshine?’ Her little plimsolled feet patter down the steps till she reaches him. ‘I was looking for you yesterday. Malachi tells me you’re not going kiddie club anymore.’

‘What?’ He laughs and fans the air between them. ‘Youth club? Nah, nah. I’m too old for that, man.’

‘Don’t man me. What is this?’ She pulls the spliff from behind his ear and he awaits the lecture. Mary’s got a lecture for everything these days. It’s almost like when Nan left last summer she handed Mary some kind of oracle of lectures, one for every minor deviance.

‘It’s Saturday. I’m allowed a little relief from life.’

‘Why not go and relieve yourself with a book?’ Mary rolls her head around like the African American women she’s always watching on TV. She leans towards him and sniffs his T-shirt till he moves away self-consciously.

‘What you doing? I’m clean. You know me, fresh like daisies.’

‘You stink like drugs.’

He laughs. ‘Oh my days. Leave me alone. It’s bank holiday weekend.’

‘You don’t work. Every day is bank holiday weekend for you. This is no good, Tristan.’ She holds the spliff in her hands. ‘If you smoke too much wacky backy you’ll get voices in your head.’

‘Is that a fact? Is that what the NHS is training you nurses to tell people nowadays?’

It’s obvious how hard she’s trying to hold a look of disappointment in her creased face, so he hits her with his biggest smile. ‘Come on, Mary, marijuana is a natural product. It’s grows alongside roses and shit.’

‘Don’t shit me.’

Her lips soften into a smile as Tristan laughs. She reaches up and puts the white roll-up back behind his ear. Such a pushover.

‘You come with me,’ she demands.

‘What?’

‘Walk me to the bus stop.’

He groans, knowing this will be Mary’s time to grill him on school, smoking, girls and anything else that needs to be filled in for her regular report back to Nan.

‘I can’t walk you, Mary. I’m busy. Meeting friends and going fair later, innit.’

‘You don’t have a choice. Come.’

She takes him by the arm and they walk down the stairs in silence. The ground floor is filled with the smell of the caretaker’s lunch – egg salad – and the sound of football on his radio.

‘Why you wearing so much white?’ Mary asks as they emerge into the heat and light of day.

‘’Cause it makes me look like an angel.’

‘Angel, ha. That earring makes you look like George Michael.’

‘Boy, you’re giving me a hard time.’

She snorts then let’s go of his arm as something hard and metallic falls to the ground in front of them. It’s her nurse’s fob watch.

Tristan picks it up and hands it back. ‘It’s broke. Why you still dragging this about? It looks so old.’

‘Because it is old.’

‘Get a new one. Get a digital.’

‘I don’t need new anything,’ she snaps while trying to re-pin it. ‘David gave it to me.’

A woman in hot pants and a bright red halter top, covering very little, walks past. She’s too old for both Tristan and her choice of outfit. Just his type.

‘It’s hot out here,’ he calls in an attempt to get her attention.

Mary grabs his arm again and pulls him away from the woman. ‘This temperature would be like winter in Manila. It is thirty-five degrees there. Where you going today?’

‘Told you. There’s a funfair over on the Heath.’

She stops and grabs her elbows in that nervous way she often does. ‘I hate funfairs. There’s always trouble at funfairs. Always someone getting robbed or getting their head broken on a ride.’

‘Yeah, that’s why I don’t get involved with rides. Those gypsies don’t do health and safety checks. I’m going to check a few gal and that.’

Mary reaches up and takes hold of one of his cheeks. ‘Eh, sunshine, put a sock on it. Don’t want any babies running around here.’

‘Oh my days, you’re tryna embarrass me. As if I would have a baby with any of these mad estate girls.’

They both turn to face the car park where a few boys cycle about in circles, shouting at each other. Tristan hadn’t even noticed them coming round. Behind them, on the wall, sit three older boys: Ben Munday, who has been able to grow a full beard since he was thirteen, and two others, who wear red bandanas around their heads like rap superstars. Tristan still owes Ben Munday twenty quid. Shit.

‘You know them ragamuffins?’ Mary asks.

He shrugs. ‘Nope. Not really.’

‘But they’re looking at you.’ She scratches at her left elbow and inspects it, as if she has been bitten by something.

Tristan really doesn’t have twenty quid right now, his own cash depleted weeks ago, and Malachi is being tighter than usual with the student grants and carer benefits that keep them both ticking over. He considers asking Mary but something about the way she frowns and fidgets tells him she’s not in the most giving of moods.

‘Tristan Roberts,’ Ben Munday calls.

Mary widens her eyes. ‘You don’t know them? Liar. They look like crack dealers, like Bloods and Crisps.’

He laughs so hard he needs to use her little shoulder to support himself, ‘It’s Bloods and Crips. Where you getting this stuff from?’

‘Don’t make fun of me.’ She shakes him off. ‘I see it on Oprah. I know all about gangbanging.’

‘Please, never say gangbanging again. And stop being so judgey. They’re kids from my school.’ Though they both know the wall boys are long past school age.

‘Eh, Tristan?’ Ben Munday calls again.

This time Tristan knows there’s no escape. ‘I better go check them out, all right?’ He nods at her as he walks off slowly, already thinking of how to downplay knowing a ‘gang’ when his nan next asks him about it. ‘And Mary, get rid of that nasty old watch.’

CHAPTER FIVE (#ulink_58664019-fc5b-5f8b-8890-12d7140e8640)

Chapter Five ,Mary (#ulink_58664019-fc5b-5f8b-8890-12d7140e8640)

She watches Tristan walk over to the ragamuffins that line the wall. He touches fists with each of them, and Mary catches a glimpse of the big Cheshire cat smile that makes him so endearing. She doesn’t want to think anything bad of Tristan, who deserves a million chances to get it right, but he’s smoking too much marijuana and surrounding himself with too many bad influences.

When Mary promised the boys’ nan she would keep a close eye on them, she thought it would be an easy job. She had known them since they were babies and, despite their chaotic upbringing, they were mostly good boys. But Tristan worries her at the moment. It’s no longer as easy as telling him to stay off the streets and he stays off the streets. She can’t fool herself: she has no real control over him. It’s like what you see on Oprah. Boy listens to rap music telling him to go shoot a policeman. Next day boy goes and shoots a policeman. She worries about him. All the time she worries about him.

Again it comes: twitch, twitch, twitch. She pushes her short blunt nails into her bony elbow in an effort to stop the tic.

Right now, there is a worry bigger and more urgent than Tristan. Mary’s husband, David, will descend on her any day and she is sure her guilt will shine through like a firefly in a jar. She will slip up somehow, maybe smell differently or perhaps refer to something only a woman in love would know. He will watch her and he will realise: his wife is an adulteress. When he came last, just over a year ago, she had started seeing Harris Jones outside of their nurse and patient relationship. Nothing more than long walks around the Jewish graveyard behind his house. A place safe from the prying eyes of others, somewhere they could be together to look at the bluebells and put the world to rights. An innocent friendship. But now, now things were so different.

‘Hot enough for you?’ the big ginger man who lives in her block asks as he stands outside the phone box, his glasses sitting lopsided across his babyish face. He is new to the area, one of those care-in-the-community patients. He runs his hands down the front of his T-shirt; it has a print of a young Elvis Presley on it, all hair and curled lip. When Mary first met David he was working as an Elvis impersonator at The Manila Peninsula Hotel. Mary hates Elvis. She smiles politely at the man as she spots the number 53 pulling into the bus stop.

She flashes her bus pass and rubs her arms discreetly against her polyester white uniform. The door closes behind her and traps in the heat and smells of the passengers. Mary thinks of how she is breaking the vows she took all those years ago in the local church with the baskets of sun-bleached plastic flowers and the priest with the lisp. She falls into that awkward middle seat at the back of the bus and feels the woman to her right tighten her grip on a battered library book so their arms don’t touch. Mary can just about make out the title: Broken Homes Make Broken Children. An omen? It’s like the world is conspiring to tell her something about her own wrongness, her dishonesty. But broken children? Her twins were hardly children anymore, thirty-five this year, and with careers and families of their own. Mary can’t imagine John’s or Julia’s life being affected by her having an affair or finally divorcing David. Divorce. As the word enters her mind the scratch becomes a searing itch and she tries to distract herself. She pulls a tissue from her bag and dabs her clammy face; the sun catches her wedding ring and it glints sadly, as if to mock her failure as a wife.

The bus picks up speed and a welcome breeze flows through the narrow windows. The woman with the cursed book gives Mary a sideways glance, their eyes meet and she adjusts herself to face out of the window. No one wants to deal with a crying nurse on public transport. As the bus nears Vanbrugh Close, Mary stands and presses the bell. She squeezes herself past the other sweaty passengers, towards the exit, ready to get off and face her second life. The doors hiss open and she steps into the full force of the sun. Immediately, her state of guilt gives way to something like joy, for although her affair is sordid and secret it is also satisfying, and her heart thumps with schoolgirl excitement at the prospect of seeing him again.

The walk towards the close of bungalows fills her with a feeling she remembers first having when she was nineteen and on the cusp of marrying David. A feeling she enjoys but knows she should not have in relation to a man other than her husband. Pop music plays from a stereo; a father and teenage daughter wash down a car together. They both glance up and smile at her. They look like a television advert: perfect and happy. On the other side of the road an elderly lady in a straw hat and pink gardening gloves picks at a blooming brood of hydrangeas. Vanbrugh Close is a world away from Nightingale Point and its smelly stairwell, blinking strip lights and cockroaches. And as Mary turns into the small neat drive of Harris’s home, she realises the life she has created with this man is a world away from herself, from the woman she has grown to be: the mother of two, grandmother of four, nurse of thirty-three years and wife to a fame-chasing husband.

CHAPTER SIX (#ulink_b61acfbb-7b41-5345-bac0-7f76f7e44af9)

Chapter Six ,Pamela (#ulink_b61acfbb-7b41-5345-bac0-7f76f7e44af9)

She lies on the sofa listening to the neighbours’ argument as it sinks through the wall. The mother–daughter screaming matches have become an almost weekly occurrence, both of them going back and forth at each other in their matching catty voices. Pamela closes her eyes and imagines what it would feel like to scream and shout at Dad the way the girl next door does with her mum. Pamela could never; she would be too scared to say all the things she really thinks about him. She jumps at the sound of a door slamming in the neighbours’ flat, the sound that usually signals the end of the row. And now there’s nothing to distract her. She stretches each leg out above her head. She misses running so much. How long will this go on for?

On the train back from Portishead Dad had told her not to expect to return to London and fall back into her normal routines, but she never expected this, for him to actually lock her in the flat, to put a complete ban on her going out. There was only ever a slim chance of him letting her take up running again, but it was him that pushed her to start swimming after her injury, so why rule that out as well? There’s no way he could have found out how little she actually swam.

‘I’ve circled the ladies-only sessions for you,’ he had said as he handed her the pool timetable. He even went out and bought her a costume.

She knew she wasn’t going to like swimming as soon as she got into the cold changing rooms. Most of the locks on the cubicles were broken and women of all shapes and sizes roamed about naked. Pamela looked the other way as old ladies stood with their swimming costumes half hanging down, applying deodorant and chatting to friends. There were used cotton buds left on the wooden slat bench, the floor dusty with talc. Quickly, she changed into the overly modest costume and made her way out to the pool, her eyes already stinging from the chlorine.

As she waded through the water her fingers caught long strands of black hair. She couldn’t get a rhythm going, the pool was too small and crowded, and she found herself gripping the scaly tiles at the far end, waiting for someone to complete a lap so she could have a turn. There was no freedom, no clearing of the mind and no possibility of losing herself in the monotony of the movement. It was the opposite of everything she loved about running.

She flipped her collar up while she stood under the awning outside, watching the bus home pull away. If she ran she could be home in fifteen minutes, but there was no rush to get back there, to sit in the dreary living room alone.

Two people came towards her with their hoods up. One went through the sliding doors but the other one stopped.

‘Hey.’ It was Malachi. He removed his hood and wiped the rain from his face.

‘Hi.’ She wanted to smile back but instead looked around cautiously in case Dad appeared from somewhere.

‘How’s your leg?’

‘Fine. Well, no, it’s sprained, so I’m giving it a bit of a break from running.’

The sliding doors kept opening and closing until Tristan stepped out from them. ‘Mal, we’re not allowed in.’

‘What?’

‘Oh, it’s a women-only swim session,’ Pamela said.

Tristan stood between the two of them. ‘What kind of sexist nonsense is that? I bet they don’t run men-only sessions, do they?’

Malachi rolled his eyes.

‘Let’s go gym instead?’ Tristan said.

‘I told you, you’re too young for it.’

‘Come on, swimming never gave anybody a six-pack. Ain’t that right, Blondie?’ He nudged her side.

‘Maybe you should take up running?’ she suggested, still looking at Malachi.

‘I’d like that.’ Malachi smiled and held her gaze.

Tristan laughed. ‘Yeah, running is a great choice of sport for a chronic asthmatic.’

‘Tristan, I’m going to meet you back home, all right?’

‘For real?’ Tristan looked at Pamela like he wanted to laugh. But of course, it didn’t make sense that someone like Malachi, who was tall and perfect, would want to spend time with a girl like Pamela, who was plain and invisible.

Malachi dug in a pocket and pulled out a crumpled fiver. ‘Here, go cinema or something. I’ll see you later.’

Tristan kissed his teeth as he took the note. ‘All right, see you back home. Laters, Blondie.’ He threw up his hood and sulked off into the rain.

They stood and faced the road, the rain coming down heavier now.

She wanted to wait for him to speak first, but couldn’t hold it in. ‘You know it’s too wet to run, right?’

He looked at her. He had amazing eyes. ‘I know. And you’ve been swimming already. You hungry?’

She shook her head. She didn’t have money to eat out anywhere.

‘What about a drink then? There’s a greasy spoon over there, it does good milkshakes. I’ll race you.’

It was awkward as they ran to the café together, as if they both knew straight away there was something more happening. The smell of burnt onions hit her as they stepped inside. They sat opposite each other in metal chairs and he picked up the laminated menu and held it closely to his face, studying it for way too long. Frowning, his forehead wrinkling, he looked so serious, so utterly different from every other boy she came across at school.

‘How old are you?’ She felt embarrassed straight after asking it.

‘Twenty-one.’ He put the menu down and folded his arms. ‘Twenty-one going on sixty.’

She smiled at him. ‘I know the feeling.’

He looked at her for a beat too long.

‘I’m almost seventeen. I’m the oldest in my year group at school,’ she said, trying to justify their age gap. ‘Seventeen in September. If I was born one day earlier I would already be in college.’ She paused. ‘You and Tristan don’t look very much alike.’

‘No. We’re not alike in lots of ways.’

‘Do you have the same dad?’ she asked.

‘What kind of question is that?’

The milkshakes came and she felt she had blown it, asked a stupid question and revealed herself to be a stupid schoolgirl after all.

‘I’m sorry, I didn’t mean to be nosy.’

‘He’s my brother. That’s all there is to it.’

She nodded and mixed the milkshake with the end of the straw.

‘Tristan said he’s never seen you at school before.’

‘No one sees me at school. No one sees me anywhere.’

‘I see you.’ Malachi smiled.

As they came out of the café, back into the real world, Pamela felt cautious again. ‘Do you mind if we walk back separately?’ she asked.

‘But we’re going to the same place.’

‘You met my dad – he’s quite strict about who I hang out with. He doesn’t really let me see boys.’

The word ‘see’ almost implied that she thought they had started a relationship.

‘I understand.’

How could this work? Could she really see him again? She wanted to. But there were lots of things she wanted to do but wasn’t allowed.

‘I don’t really have time to, you know … do stuff outside of school and sport. My timetable is quite packed.’

He straightened up and rubbed his face.

School and sport, that’s all her life was. Surely she could take the risk of having something else going on?

‘My dad wants me to go swimming every Tuesday and Thursday between six and eight. But I hate swimming.’

‘So what are you saying?’

‘That I’m free every Tuesday and Thursday between six and eight.’

He nodded. ‘Got it.’

They separated as they reached the field in front of the estate. He sat on a bench and she walked off, trying her best not to keep looking back at him. She pulled her hair in front of her face, smelling its mix of chlorine and fried food, and knew she would never set foot in the pool again.

Pamela paces the flat like the caged animal she is, stopping each time to look at the front door. She misses Malachi so much. She doesn’t want to chase him, but he needs to know the truth. That she didn’t want things to end the way they did and hopes they can work out a way to still be together. But first, there’s something else she needs to tell him.

What can she do? She doesn’t want to talk over the phone; he’s always awkward on the phone. Half the time his phone is cut off anyway. But what choice does she have?

She picks up the phone and dials.

Thank God, it rings.

CHAPTER SEVEN (#ulink_6d27704b-ee1d-5ad9-aac6-c7020584b7a2)

Chapter Seven ,Malachi (#ulink_6d27704b-ee1d-5ad9-aac6-c7020584b7a2)

Malachi pulls his books back onto his lap and tries again. He’s behind on his reading and hasn’t even made a start on the essay. There’s no way they will let him have an extension on the deadline again. The tutor won’t understand that he’s behind because he has a broken heart. It’s pathetic.

His eyes hurt and so does his head. Maybe Tristan’s right about the eyesight thing. He can’t concentrate. He sifts through the morning’s post. Junk mail and another bill. Where does all the money go anyway? He’s only just managed to clear the rent arrears and get the phone put back on. The electric bill looks steeper than usual this time, probably because of Tristan’s habit of running the hoover every day and putting on a wash for one or two T-shirts. Their mum never taught them anything about keeping home. They were learning as they went; they didn’t have a choice.

Malachi allows his head to fall back onto the beaten sofa, the plush long gone from previous owners, and puts his hands over his face. There’s got to be an easier way to get by than this.

‘Get it together,’ he says to himself. He wonders if there’s anything he can do to get some cash in. Well, there are things: someone had talked about selling knock-off TVs, and he’d also heard rumblings about single men with British passports being paid for taking part in bogus marriages. But both these things seem to come with a lot of risk. And Malachi has a lot to lose if things go wrong.

There’s no other option; it’s time to call Nan. The last thing he wants to do is stress her, or make her feel like she’s made a bad decision leaving him in charge here, but what choice does he have? He needs to watch the money more closely this month. He wishes he never bought that pair of pink and lilac running shoes for Pamela – they were so expensive. But her old ones were almost worn through and she seemed serious about taking up running again once she recovered from her injury. He wonders if she’s allowed out to run in Portishead. She’s probably not allowed to do anything there. Anyway, after what happened between them Pamela probably threw the trainers off the roof. She must hate him after what he did, how he denied her. It hurts to imagine her feeling this way; it’s so far from how she was at the start, back when she was completely into him. He misses those early days with her, when her dad worked long hours and she had freedom. Back when being in this flat, in his bedroom, felt like they were a million miles off the estate and away from all their problems. They would lie in bed and allow themselves to believe it would all work out, that her dad would relax and let go of whatever his prejudice against Malachi was.

He wishes he could stop thinking about her, stop using his memories of them together as a place to escape to. But how can he? When everything here and now is so challenging, so dull and so lifeless without her? He wants her back, back here in the flat with him, talking to him and making him laugh. He can’t stop thinking about those wintery afternoons; he can’t stop imagining he is there again.

‘It’s so cold. What time does your heating come on?’ Pamela had asked as she came back into the bedroom.

‘It doesn’t.’ He didn’t want to weigh her down with money problems, to soil their time together by talking about a situation he felt was drowning him.

She jumped back in the bed next to him and shivered. ‘Your brother’s home. He didn’t seem too pleased to see me here. Asked if I had permission from my dad to have a sleepover.’

Idiot. Malachi laughed. ‘He’s a wind-up. Ignore him.’

‘He doesn’t like me.’

Malachi was never quite able to work out what his brother’s problem with Pamela was. Especially as Tristan was always going on about Malachi having a girl and now he had one.

‘I try with Tristan. I really do. But he openly yawns every time I speak to him,’ she said. ‘He does it on purpose.’

Malachi stifled a laugh. It did sound like the kind of thing Tristan would do. ‘He’s not used to someone other than himself getting attention, that’s all.’ Malachi put his arm around her and twisted a lock of her hair around his finger.

‘You’re not scared of my dad, are you?’ she asked suddenly.

‘It depends. What did he do to your last boyfriend?’

‘I told you, I’ve not had boyfriends.’ She moved away from him then, as far as the single bed would allow, and he braced himself to hear bad news. ‘But when I first moved to London one of the youth coaches from running club called my house to ask me out.’

‘And?’