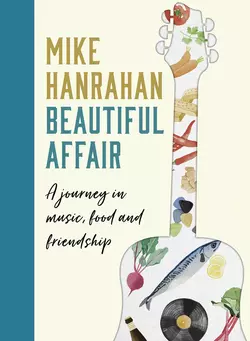

Beautiful Affair

Mike Hanrahan

A Ballymaloe-trained chef, songwriter and musical right-hand-man to the legends of Irish song takes us back stage and into the kitchens of a bohemian, international and surprisingly foodie group of Irish household names, including members of the Dubliners, Sharon Shannon, Stockton’s Wing, The Fureys and De Dannan.Story-led and full of anecdotes, Mike Hanrahan tells the tales behind the music of the 1970s and 80s in Ireland and cooks up the favourite dishes of its most-loved singers.From memories of family recipes on country hearths, to the flimsy vegetarian grub served up in his early folk-club days and communal pressure-cooker stews in a crowded tour bus, Mike shares the excitement and passion that good food and great music bring to the table. After training with Darina Allen at Ballymaloe, he turns his hobby into a second career and works his way up in professional kitchens across the country, collecting stories as he goes.

COPYRIGHT (#ulink_ba0f616e-9a51-5202-ba54-3c2d4f4d92c4)

HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

First published by HarperCollinsPublishers 2019

FIRST EDITION

© Mike Hanrahan 2019

Illustration © Charlotte O’Reilly Smith 2019

Photographs from the author’s personal collection unless otherwise indicated

Cover design © HarperCollinsPublishers 2019

Cover illustrations © Charlotte O’Reilly Smith

A catalogue record of this book is available from the British Library

Mike Hanrahan asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the nonexclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins e-books.

Find out about HarperCollins and the environment at www.harpercollins.co.uk/green (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk/green)

Source ISBN: 9780008333003

Ebook Edition © October 2019 ISBN: 9780008308759

Version 2019-09-10

DEDICATION (#ulink_5654d8cc-1c48-5480-970e-3c40e2cb0356)

To Donna

CONTENTS

COVER (#u06c62c74-068a-5836-9812-c086de189bc9)

TITLE PAGE (#litres_trial_promo)

COPYRIGHT

DEDICATION

CHAPTER 1 FIREFIGHTER (#u50d075ff-4203-5b80-baad-cd702f3a7f67)

CHAPTER 2 DOOLIN (#u5e7d2d94-3eee-527f-b823-5ebf031a88c8)

CHAPTER 3 MAURA O’CONNELL (#u6a4d9c95-ca6e-5069-b2b2-4893d36122a2)

CHAPTER 4 TAKE A CHANCE ON ME (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 5 BAND OF BROTHERS (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 6 FINBAR FUREY (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 7 RONNIE, I HARDLY KNEW YA … (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 8 LEGENDS (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 9 VAGABONDS (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 10 BALLYMALOE COOKERY SCHOOL (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 11 LEARNING CURVE (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 12 PAT SHORTT’S BAR (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 13 ELEANOR SHANLEY (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 14 ARTISAN PARLOUR & GROCER (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 15 ENCORE (#litres_trial_promo)

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS (#litres_trial_promo)

ABOUT THE PUBLISHER (#litres_trial_promo)

CHAPTER 1 (#ulink_d8d74264-c007-5286-9fc8-186bc4e4ff63)

FIREFIGHTER (#ulink_d8d74264-c007-5286-9fc8-186bc4e4ff63)

Farmer John, plough your fields, bring the seed to grain,

Feed the hungry, fill the belly of the traveller as he sails,

A weary heart, a tired soul will try come what may,

Farmer John, plough those fields, help him on his way.

– ‘Firefighter’, What You Know (2002)

THE CROSSING

My parents grew up in the neighbouring farming communities of Barntick and Ballyea in County Clare. As a young couple they chose to start their new life in the burgeoning outskirts of Ennis, which offered opportunities for work and a new rented home in which to raise their young family. In 1957 they moved to the just-built St Michael’s Villas on the edge of Ennis, and there they raised eight children, six boys and two girls: Gerard, Joseph, Kieran, myself, Gabriella, Adrian, John and Jean. I was in the middle; the youngest two were twins. Dad provided and Mother nurtured.

When we were young, our summers were spent secluded on my grandparents’ farm, a few miles from civilisation. We walked to and from the village of Ballylea every Sunday morning, dressed in our finest to attend Mass at the parish church. The farm was our domain, where our friends were the animals and our sustenance came from the very land we roamed.

Come September, we returned to the bustling terraces of Ennis, playing games on the green with the O’Loughlins, the Howards, the Hahessys, the McMahons and the Dinans. By contrast with the farm, it was a noisy playground where you fought to shout your name.

Even as children, our ‘country’ mentality jostled for position on the streets and in our schools, while the country folk saw us only as townies. We were somewhere in the middle, criss-crossing – in language, expression, attitude and mind.

But home life had surety, unity and a purpose, constantly nourished with wonderful music and beautiful food. Music and food have kept me on track at every crossing.

DAN JOE

My grandfather, Daniel Joseph Kelleher, was born in 1898 at No. 2 Victoria Villas, Victoria Cross in Cork City, and was sent to live with his aunt Mary, who lived with her husband Patrick Nagle in Ballyea in County Clare. It was not unusual in those days for large families to send some of their children to live with their aunts or uncles to help alleviate the pressure on food and board at home. Dan Joe grew up in Ballyea and married a local girl, Margaret McTigue. They settled down to raise their family of four boys and one girl, my beautiful mother, Mary Kelleher.

Dan Joe was a gentle man who worked for the local government and spent the rest of his time working the farm with Margaret, raising cattle, pigs, sheep, geese and hens. He wore a dark grey fedora that only left his head when he sat down to eat or attend Sunday Mass. We spent our entire summer school holidays on their farm, a playground of vast open acres of grazing fields, stables, hen houses, tackle room, straw-bedded sheds and a monstrous metal-framed hay barn that would fill to capacity during our stay. At the rear of the milking parlour was a slurry pit which fed the land and gave off the most noxious of smells in the July heat. Manual farm machinery speckled the yard, along with milk churns, water barrels, a couple of dogs and the ever-present Charlie, the wonder horse, our absolute best friend in the whole wide world.

Beyond his work on the farm, Dan Joe loved hurling and Irish music. He stood proud at the back of the Ballyea or the Clarecastle village halls whenever we performed at the variety concerts and always cheered our successes. He loved the sound of the accordion so much he gifted one to my brother Joe, who played it for a few years.

He was quite ill towards the end, and in his final days, a hush surrounded the visit of a local healer, who was called to administer the sap from the bark of a birch tree which was boiled in milk along with a few other secret ingredients. In rural parts of Ireland, doctors were expensive, so most people looked to the local healers and their folk medicine for help. The practitioners were dedicated, and believed in the virtue of their treatments, with very little money exchanging hands, if any at all. Some local communities continue to believe in the power of these natural remedies.

Alas, it was all too late for poor Dan Joe. I was almost twelve, and his was my first funeral, an event that left an indelible mark on my memory.

THE WAKE

I still see that never-ending procession of black suits and shawls as they shuffled their way through the front door into the crowded parlour, passing the mirrored oak sideboard with its fresh flowers and photographs of happier days. Onwards they moved, in around to a smoke-filled kitchen with its glowing fire, down under the narrow staircase to a darkened room that smelled of church candles and lilies and echoed a constant hum of prayer and sorrow. Circling the bed, they blessed themselves as they passed by a very peaceful-looking Dan Joe, dressed in a crisp white shirt and a grey paisley tie. He lay motionless and cold, but free of all the pain that had etched his face in the recent days. Ushered on by my uncle Tom, the latest batch of mourners offered their condolences before rejoining the mêlée, talking, laughing, crying, whispering, drinking and eating from plates of sandwiches and cakes brought in by neighbours and distributed eagerly by all the grandchildren.

Later, as the crowd dwindled, I sat nervously staring at his figure, wondering how it was possible that I would never hear his voice again, never see that smile or feel the warmth of his arms around my shoulders, and my thoughts drifted to poor Charlie and I wondered how he would cope now that his master was silent. He would surely miss him in the morning and every other morning after that, the click of his voice, the gentle tug of the reins and all their little chats during the daily rituals of tacking and farming.

‘How is all this possible?’ I thought. Maybe in the morning he might come back to take us all down to the L-field to gather the cows. But the following morning was spent in a crowded church of whispered prayer followed by the short procession to an adjacent graveside where men lowered his coffin deep into the ground. A raw, sudden swell of tears and sadness filled the autumn air as the pebbles hit the wood to finally signal his end.

On an old country lane where the wilderness still reigns

An old man takes a flower in his hand.

How I’ve watched you bloom and fade

and all the beauty you create

I’ll take with me that pleasure as we part.

– ‘We Had It All’, Someone Like You (1994)

NANA KELLEHER

Dan Joe’s wife, Margaret McTigue, came from a reasonably well-to-do local family, but her marriage to Dan Joe was not well regarded and her dowry reflected the disappointment in her choice to marry down. As a young woman she was sent to agricultural college in Tipperary, where, in addition to general agricultural studies, she specialised in butter- and cheese-making. I only learned of her cheese-making ability recently, and it may explain my own fascination with the craft. While a student at Ballymaloe Cookery School, I was hooked from our first cheese demo. The pleasure of working with the curd is sensational and I found it very therapeutic; little did I know then that my Nana Kelleher may have passed on her cheese gene to me. She spent her days churning her butter, making cheese, feeding geese and hens, tending to the livestock and forever cooking or baking in Bastible ovens over a large open fire, which was constantly aglow.

Every autumn, neighbours came to the house to help with the curing of the pig. It was customary to gift the help with cuts of meat as they departed. The wonderful saying, ‘We weren’t all one when you killed the pig,’ was often used and still is in some areas to remind certain houses of an oversight in such times of plenty.

The Feast of St Martin, or Martinmas, is celebrated on 11 November each year and was generally regarded as the date that all pigs be butchered and prepared for the winter. This date is also linked with ancient sacrificial geese and all sorts of darkness. My legend has it that St Martin invented the pig from a piece of beef fat. He gave it to a young girl, telling her to put it under a tub and turn it upside down and await further instruction. Being selfish, the girl split it in two and hid her own piece under a basin. The following day, a sow and twelve piglets appeared where Martin’s morsel had been placed, but as punishment, the girl’s sliver produced mice and rats, which ran off around the house and into the yard. St Martin then created the cat from a mitten, and sent it off to chase the vermin; to this very day cats continue to do his bidding – or so the story goes!

Every ounce of meat from the pig was used. The head was boiled to produce brawn, also known as head cheese, a terrine set in aspic. Sometimes the cheeks and jowls were removed, boiled and eaten as delicacies. Those traditions live on; for my own fiftieth birthday party, I cooked a pig on a spit and my friend and champion Tipperary hurler Nicky English phoned in a frenzy, saying he was delayed in town. ‘Mike, has anyone touched the jowls yet? If not, put my name on them! Make sure no one goes near them, I’m on my way!’ Sure enough, as soon as he arrived, he made a beeline for the pig’s head. He was a very happy camper as he sat back on his chair with a beer and a jowl. Maybe there’s something in them there jowls that’s good for the hurling.

Nana used both a wet and a dry cure. After a few days’ hanging, the pig was jointed and cured with salt; the following day, the moisture extracted by the salt was washed away and another coat of salt applied. This dry-cure process might take three to four days. A wet cure was a simple solution of salt and water in a barrel, left for days. The loin, shoulders, legs and belly were then hung from the rafters and used as required for rashers, bacon and Bastible roasts. Some were placed in the chimney breast for smoking.

The cured bacon hung from the hooks in the main room, protected by two or three strips of flypaper. That paper gave off a very distinctive sweet odour, and its colourful package always conjured up images of America for some reason. Perhaps they were part of a parcel received from rich cousins across the Atlantic.

Nana cooked everything from chickens, stews, bacon and cabbage to vegetables, to breads and cakes on an open fire in a selection of cast-iron Bastible pots that hung from a metal crane. She fried pork chops, homemade puddings and eggs on griddle pans which sat among the burning sods of turf. Hanging from the crane was a great big giant black cast-iron kettle, always full of water, constantly on simmer ready for the tae or the washing-up. Bastible cooking required great skill and experience. There was no thermometer to monitor the heat, and certainly no alarm clocks to signal the end of cooking – it was sheer skill. Her breads and sweet cakes were placed in the ovens, with hot turf spread on to the lid to ensure even heat distribution. There is a beautiful saying – ‘Never let the hearth go cold’ – so at bedtime, a sodden piece of turf was laid, burning slowly through the night to keep the embers warm. In the morning flames returned with the help of a poker and some kindling.

Most of the milk from their herd was transported by horse and cart three mornings a week to the local creamery. Nana always kept one bucket at home, covered with a tea towel. The separated cream became butter, and the rest we drank liberally. As far as we were concerned, the butter was our Nana’s only culinary weak spot. It was salt-free, and we all hated it with a vengeance. What was worse, we weren’t just subjected to it over our summer holidays on the farm; during winter months she would send four pounds of the stuff weekly to our home, and the sight of it on the table brought many sighs and moans, much to my mother’s chagrin.

Nana Kelleher was firm, very strict and fearless around animals. We often saw her chase away foxes or stray cats, but the best was her battles with the tiny field mice who were regular visitors to the cottage, searching for warmth and food. On one occasion a mouse hid in the scullery behind pots and pans. Nana stood there with her hawthorn stick, carefully removing the pots and basins one by one, until finally the mouse was exposed and made a dash for the opened door and his chance at freedom. As he sped past her, the swish of her stick sent him staggering across the farmyard, Nana in hot pursuit. Off he raced across the muddied track and to our delight reached the farmyard wall, where he disappeared into a crevice and off out into the safety of the L-field. Later that night during our bedroom whispers it was agreed that he would now be so scared of Nana he would never return. We all hoped he got home safe to warn his family and other mouse friends to stay well clear of the angry woman with the very big stick.

ANIMAL FARM

The excitement of our first morning of summer holidays at the farm each year is etched in my memory. The sun beaming through the window, the farm already in full flow with the jangle of tackle as Granddad prepared Charlie for the creamery run, Nana swooshing the geese over to the sandpit, hens clucking to the sound of cock-crow and the little calves bellowing at the distant trough.

After a quick wash in the light blue ironstone basin with its pitcher of freezing cold water we moved from the parlour into the heat of the warming fire, to eat a bowl of porridge and some homemade bread with that loathsome butter, thankfully offset by Nana’s beautiful homemade gooseberry jam. We then set off on the first of our many daily adventures. This vast open country playground was ours for the taking, and out there on the L-field, so named for its shape, we were anything our imagination conjured up: hurlers, soldiers, swashbucklers, farmers, truck drivers, Olympic runners, show jumpers, tennis players, Pelé or Pat Taaffe on Arkle chasing down Mill House for the Gold Cup.

Underneath the rows and rows of Scots pines that separated the cottage from the working farmyard was our very own battleground where we separated into little army corps, erected barricades and went to war with bundles of fallen pine cones. Occasionally a stone might be inadvertently introduced, and then the battle turned nasty; all bets were off when the first screams drew Nana from her busy day to scatter us away from the theatre of war, to hide in the hay shed and dream up our next escapade.

Charlie the horse, our best friend ever, was patient, passive, intelligent, hardworking and without doubt the most loved animal in the world. Whether he was resting or cooling in the shade, his ear perked at our calls, drawing him out of the haggard to amble his way to the top gate for a feed of apples and nuts with plenty tender loving care.

In the early morning we gathered the cows for milking. Some of the cows had pet names given to them by Nana and Granddad and each one had a personality of her own. Some were gentle to milk and others just lacerated you with their swishing tails. I am still convinced their massive eyes were laughing at each successful flick of the nape. The young calves were treated to nuts, and petted by all the children, unlike the poor geese who were taunted and riled into a frenzy until they lost their cool, dipped their necks and lunged after us in attack, hissing angrily as we ran screaming back into the safety of the hay shed.

Most of the farm chores were OK, but every now and then you pulled the short straw and had to clean out the filthy henhouses, or shovel the dung from the slurry pit into a wheelbarrow to be spread across a field at the back of the main yard. The worst job was clearing the ‘yallow weeds’, as Granddad called them. Rag weed or Ragwort was, and still is, a scourge on farms and regarded as dangerous to livestock, so every summer it had to be cleared. Fields were cordoned off and a concerted effort was made by the chosen ones to get every last stalk from the ground. A yallow weed day was long and extremely torturous.

THE MEITHEAL: THE GATHERING

The animals lived well on the farm, with a diet supplemented by the hay that we saved during the long summer months and stored in the barn which stood beyond the pine-tree battle line. The meadow was located a few miles away in an area called ‘the Slob’, which was, to all intents and purposes, a very large allotment shared by many local farmers. In early summer the community gathered with their scythes and methodically made their way through the meadows, cutting the tall grass. At intervals during those long working days, tools were downed and the ‘tae’ was served, with sandwiches, scones, tarts and ‘curnie’ cakes, or spotted dick as it was also called. My mother used to add a pinch of ginger, nutmeg or allspice to her cakes, which gave the bread a great colour and a sharper taste. Each house had its own version.

The bottle of tea was wrapped in old newspapers or tea towels to retain the heat. On occasion, a different, magic bottle that no one ever seemed to mention was passed around among some of the elders.

Weeks later when the grass was dry, a team again assembled to rake the hay into little bundles, and then into small cocks, or ‘trams’ as we used to call them. They stood about eight feet high and were secured by a hemp rope also known as a sugán, which was weighted down on either side with large rocks. Sometimes a sheet of plastic was secured at the top of the tram to prevent the rain seeping through. The hay was then slowly transported by horse and float back to the barn. The float, an exceptionally well-designed piece of farmyard machinery, was a flat rectangular platform trailer with two front-mounted rope winches controlled by three-foot wooden levers. The float tilted to the ground, ropes were tied around the tram, and winched from the field on to the platform. The weight of the hay then levelled the float, and once secured, off we went to deliver to the waiting crew at the hay shed. Along the road we might stop and chat to the neighbours, including the likes of ‘Great Weather’, who always greeted us with ‘Great weather, Dan Joe!’ come rain or shine, or ‘Winkers Kelly’, who never failed to hurl abuse: ‘Ya useless townies, ya!’ – always answered with ‘Go wan, ya big four eyes!’

The final trip of each week included a stop at Curry’s pub, where Granddad drank his bottle of stout and treated his lucky little helpers to fizzy orange and crisps. On the odd occasion we might stop at our cousin’s at McTigue’s post office, which meant a pack of Stevie Silvermints or a bar of chocolate. Those of us left behind in the haggard had to listen to the gloating and wait another day.

One morning the quiet of the farm was interrupted by the distant sound of an engine that grew louder and louder with each second. ‘That’s Pa Joe McMahon and his buck rake,’ my dad announced. ‘It’s over at Spellissy’s now, I’d say. Won’t be too long.’

Within a minute the roar of the tractor engine arrived, carrying a tram of hay on six large, pointed steel prongs. It dropped the load and was gone up the dirt road and out of sight in no time. ‘I suppose this will speed up the gather,’ Dad said with a hint of sadness in his voice. What had been weeks of drawing hay now took a matter of days. I remember a definite sense of sadness, though. The halcyon days were gone: no more trips to the meadow, no more float, no Winkers Kelly, or chewing the dry blade of grass as the world passed, and no more Stevie Silvermints after a long week’s work. It was progress for sure, but the buck rake also delivered the end of a certain magic that morning.

MICKY HANRAHAN

My other grandfather, Micky Hanrahan, was a jovial man. His family came from Fedamore in West Limerick and moved to Barntick in Clarecastle, a few miles from Ennis. He married Aggie from Labasheeda in West Clare, and they lived in a beautiful cottage on the top of the hill by New Hall Lake. The small farm was built on the edge of a rocky cliff with little growth, but it was a haven for their goats, sheep and a few head of cattle that roamed freely to forage the hazel or berry bushes. I always saw him as a reluctant farmer, as I somehow never really associated him with the land. He worked at the local pipe factory and left much of the farming to Aggie and his young family. Oddly enough I never really saw my own dad as a farmer either, although I have a vivid memory of looking on in dread and fear as he stood on top of a large reek of hay catching fork-loads from down below. Goats wandered freely around their farm amid the constant cackle of turkeys, and at the back of the cottage was an old West Clare Railway carriage which housed lots of chickens.

Once a week they travelled to Ennis to shop at Mick O’Dea’s grocery and pub. From the street you entered a shop stocked with everything from the humble spud to packs of washing powder and everything in between. A door then led you to a small bar with a high counter usually housing a row of creamy pints. It was the most beautiful bar in the world, not for its decor, which was very retro, but for its clientele, its history and most of all the friendly atmosphere. Micky usually had a few in there while Aggie filled the messages box with the help of the shopkeepers in their brown coats, who later delivered to the cottage.

The O’Deas are practically cousins to us, such was the closeness of the two clans. I went to school with young Mick O’Dea, who followed his passion for art and is now a member of the Royal Hibernian Academy and has served as its president for a number of years. His work is exhibited internationally and he is regarded as one of our greatest portrait painters. Some of his work adorned the walls of the pub when his older brother John ran it after their dad retired. Sadly, John also retired, and with him went much of the pub’s character and charm. Christmas week at O’Dea’s was particularly wonderful, as the townies returned from all over the world to reconnect for the festive season. A small transistor radio sat on the shelf in between various trinkets and was only switched on for news or late-night specialist roots music shows. In the adjacent room, once the family sitting room, the TV transmitted sports and The Late Late Show to a select club of locals seated in front of a constant burning fire.

The grocery business was very important to my grandfather’s generation. All the essentials were there: tea, butter, biscuits, cornflakes, cleaning supplies, all packed into large apple boxes and delivered on the day of purchase. O’Dea’s supplied many families with their weekly shop, but it was also a place of social gathering. There was a bond of trust and friendship within its community. As the years passed supermarkets forced many of these beautiful quaint shops to close, but in the case of O’Dea’s groceries, it was another harbinger of modernity, the health and safety officer, who finally closed the door for ever. A rarely used meat slicer on the counter drew her attention, and she instructed John that if he was to be selling fresh food, he’d have to add structural changes, which included a sink with hot and cold running water. John explained that he sold very little food, and was simply looking after a few of his older customers who had been coming for years; it wouldn’t be worth his while putting the extra money in for such a small return. When she insisted, John sighed and said, ‘Mam, there’s a terrible siege going on over there in Sarajevo, and I hear there’s hardly any food getting in at all. Yet I bet you the price of the sink that they sell more cold meat in downtown Sarajevo of a Saturday morning than I would here in a month of Sundays.’ Unfortunately, his pleas fell on deaf ears and within weeks the few groceries were replaced with bottles and cans of beer as the pub engulfed what was left of the grocer’s counter. Years of public service came to an abrupt end. Five generations of my family frequented O’Dea’s pub, either sipping porter, drinking orange or buying supplies, while others preferred their mugs of tea with a little chat upstairs in Mrs O’Dea’s kitchen.

AGGIE HANRAHAN

My father’s mother, Aggie, was formidable, the matriarch who ruled the house. In fairness, someone had to, as Micky was very easy-going and prone to stray onto the missing list. She ran the household with absolute authority, and cooked and baked the most delicious breads, cakes and scones. I still smell the griddle cake as she lifted it from the oven onto the table next to the butter dish and a pot of her homemade jam.

Aggie baked with sour milk purchased from a neighbour down the road. These days sour milk is not recommended and has been replaced with the conventional commercial product buttermilk. Since pasteurisation, souring your own milk is now a thing of the past. My mother usually left the bottle of milk out in the air to sour naturally before baking.

Aggie’s griddle bread

Makes one loaf

A little butter or oil, for greasing

350g plain white flour

A pinch of salt

1 tsp baking powder

1½ tbsp sugar

1 egg, beaten with 2 tbsp melted cooled butter

1½ tbsp melted butter

300ml buttermilk (you may not use it all)

Butter and homemade jam, to serve

1 Grease a griddle pan or heavy frying pan with a little butter or oil.

2 Sieve the flour, salt and baking powder into a bowl. Add the sugar. Whisk the ingredients further to add more air.

3 Add the egg, butter and most of the buttermilk. Gently bring together. If it’s too dry, add more milk, but we don’t want a very wet dough. Do not knead, as that will take the air from the mix. Shape to the size of the griddle pan, and ensure the dough is about 5cm thick.

4 Cook on a medium heat for 10 minutes.

5 Flip and cook for another 10 minutes.

6 Cut into wedges, and serve with butter and homemade raspberry jam.

Nana kept between fourteen and twenty goats in an old outhouse shed. Once a year they were herded west along the road to meet their puck, then returned to the farm and were encouraged to roam freely throughout the crag, where they feasted on nuts and roughage. They were never allowed too much time on grass, as it added far too much fat to their bodies. Kid meat was regular Easter fare in Clare, long before we turned to lamb, and the preparation of the feast varied from house to house. The meat certainly needed slow cooking, and some added juicy seasonal berries in with the roast for extra flavour, constantly basting. Others braised the meat in a broth of vegetables. The family drank the goat’s milk, and my uncle Chris says that excess goat’s milk might inadvertently find its way into the churn of cow’s milk before it was sent to the creamery. No waste was allowed, and no one said a word. Some families made yogurt, or their own version of soft cheese. One of Ireland’s best goat’s cheeses, St Tola, is made on a family farm in Inagh in County Clare run by Siobhán Ni Ghairbhith and her team, who produce a variety of stunning hard and soft cheeses.

Aggie reared her goats for the Easter celebrations, but her pride and joy were the Bronze turkeys, with each member of the family receiving one every Christmas. Some did better out of it than others, though – once she posted a turkey over to her son Tony in Birmingham, but somewhere along the line the parcel was held up and arrived two weeks after the Christmas celebrations. By all accounts the scene when it was opened was not for the faint-hearted, and left an indelible mark on the poor children present.

Aggie’s kitchen was the hub of Hanrahan life. The half door was constantly open for all to call and say hello. She always sat by the range while Micky sat at the table with his tiny transistor radio waiting for the latest result from Leopardstown. It was a great room for chat, food, music and gossip, and over the years a lot went on in that small confined space around the kitchen table with its ever-present pot of hot tea.

MOTHER

She’s an angel, my angel, she moves me, she sees the child in me

Won’t abandon me, my angel

– ‘Angel’, Someone Like You (1994)

My mother was taken from school in her very early teens and sent to work at Fawl’s on O’Connell Street in Ennis. Fawl’s was a pub, shop and tea importer also known as the Railway Bar. Large tea chests arrived from Dublin and the tea was bagged for sale. When we were babies our playpen was one of those tea chests. Dad fixed a bicycle tyre round the top for safety and all was going well for a couple of years until my brother Kieran worked out a way to topple the chest and crawl to freedom. In the evenings after the long journey home, my mother helped with household chores and tended to the needs of her four brothers. I have difficulty understanding why her parents chose that path for her, cutting short her education at such a young age, but she never discussed it much with any of us, and explained it away as being a different time. She never really spoke much at all about her childhood, but her photographs always show a smiling, beautiful young girl. She met my father when they were both young, fell in love and spent the rest of their lives falling deeper and deeper into that love.

My mother and I share a great passion for food and for many years we exchanged various tips over the phone or on my short visits home. I never left home without a plate of her luscious scrambled eggs and toast to set me on my early-morning journey back to Dublin. She was a brilliant cook and baker. After years of trying, I finally managed to record some of her baking recipes.

‘Right, Mum, are you ready to give up those recipes?’

‘I suppose so.’

‘So, Mother, your bread recipe – that brown one we all loved so much …’ I switched on the Dictaphone. She eyed it suspiciously.

‘I’m not talking into that yoke, Mike.’ I quickly found a pen and opened my copy book. I was very excited; my mother was about to give up the family’s secret recipes.

‘Well, for the brown, I get a fist or two of plain flour; a fist of the brown flour; a fist of bran; pinch of salt; a good pinch of baking soda – not too much, because that sometimes turns it a bit yellow although it never stopped ye all from eating it. I suppose it’s all really down to practice. After a while you get to know the ingredients and the feel of the mix, y’know. Oh yes – I sometimes add a little bit of sugar. Sometimes I might add raisins, or currants, although I never liked using the currants for some reason … I preferred using the larger raisins. And sometimes a pinch of ginger, or allspice. And sure, it really came down to what I had in the cupboard. That’s it.’

‘What was wrong with the currants?’

She dipped her head, grimaced and eyed me over her spectacle rims, ‘Sure I was eating most of them, Mike.’ She continued.

‘Well, then you need to mix them all with margarine or butter, half a pound or thereabouts, but I preferred the margarine, and then add an egg. Maybe not a full egg, it’s hard to know, Mike, you just have to judge it. After that I added some sour milk to bring it all together – not too wet, but it can’t be dry either.’

‘What happened if you had no sour milk?’

‘Well … if I had no sour milk, I would add a drop of vinegar to the good milk and that would sour it over about ten minutes. Did I mention not to use a full egg?’

‘Why did you bake the bread in a frying pan?’

‘Well, it was an old frying pan, and your father knocked off the handle for me as I thought it would make a good baking tray. It did – I used the same one for years and years. I’d butter the pan, put the paper at the bottom, pour the bread mix in and draw a sign of the cross on top with the knife and into the oven for about an hour or thereabouts. I’d turn the bread out then and leave it on top of the range, covered with a damp towel until we were ready to eat it. And that’s it, Mike. Very simple. And shur, ye loved it. Or at least that’s what ye told me, anyway.’

It was beautiful – not so sure about the simplicity of the recipe, though.

She went on to talk about her stews, casseroles, her mother’s cheese and that horrible homemade butter – she admonished me once again for my description of the butter. I had a beautiful afternoon with Mum, even though the baking lesson lasted minutes, but it was good to talk food with her. I could not wait to get back to my own kitchen to try out the recipes for myself and translate those fists into grams …

MY MUM’S RECIPES

After much trial and error, I managed to translate Mum’s measurements. I’m thinking a fist of flour is about 150g. So, we can take it from there.

Mum’s brown bread mix

Makes one loaf

300g coarse wholemeal flour

300g plain white flour

2 tsp bicarbonate of soda

1 tsp salt

2 tsp brown sugar

100g soft margarine or butter

1 egg

450ml buttermilk

Butter, to grease

1 Preheat the oven to 200°C/180°C fan/gas 6.

2 Sieve the white flour, bicarbonate of soda, salt and sugar into a bowl containing the brown flour, and mix gently.

3 Rub in the margarine or butter with your thumb and forefinger to crumb stage.

4 Beat the egg into the milk. Make a well in the dry mixture and pour in the milk. Bring it all together. It should be a wet mixture.

5 Butter an old frying pan (if you have one) or a 1lb loaf tin and pour in the mix.

6 With a knife cut across and down the centre of the loaf, and bake in the oven for 1 hour.

7 Remove the bread from the oven, turn it in the pan, then cover with a damp tea towel for one hour before serving.

My mother’s spot of dick

Makes one loaf

Mum sometimes omitted the treacle and used a mix of brown and white flour. She preferred the large golden raisins. This recipe is open to any fruit, but the harder dried fruits will benefit from a little soaking before use.

Butter, to grease

500g plain white flour

2 tsp baking powder

A pinch of nutmeg

1 tsp salt

200g coarse brown flour

100g soft margarine

1 tbsp treacle (optional)

1 egg, beaten

400ml buttermilk

150g raisins or sultanas

1 Preheat the oven to 160ºC/140ºC fan/gas 3.

2 Butter a heavy oven-safe skillet or loaf tin and line it with baking parchment.

3 Sieve the white flour, baking powder, nutmeg and salt into a bowl. Add the brown flour and mix gently.

4 Rub in the soft margarine to crumb stage.

5 Add the treacle, if using, and mix with a spatula or wooden spoon.

6 Add the egg, buttermilk and dried fruit. Mix gently and transfer to the prepared skillet or tin.

7 Bake for 1 hour, then remove from the tin, turn it upside down on a wire rack and cover with a damp cloth.

MUM AND HER ORANGE BIRTHDAY CAKE

January is when the Seville oranges come in, with many households creating their own distinct marmalades. My aunt Peggy’s won hands down in our family, and she often added some lime to her marmalade. For many years my mum celebrated her birthday on 5 January, until the year she got her first passport for a once-in-a-lifetime trip to America to celebrate my brother Kieran’s marriage to Mayo woman Pat Baines. Up to that point she had never needed her birth certificate, so when it arrived in the post, she was shocked to discover that she was in fact born on 6 January. I think we had two celebrations that year, and we’re all still a little confused when the date comes around.

For one of her birthdays, I made a three-tier orange cake, complete with orange butter icing and strips of sweetened orange zest scattered over the top. I insisted on icing it at home in Dublin before a three-hour journey to Clare. I placed the cake in a tall, sturdy-looking box, wedged into the back seat of the car with my bag and a denim jacket. When I arrived in Ennis I glanced over my shoulder to see the cake box keeled over, and melted icing drifting slowly like lava onto the seat and all over my lovely denim jacket. Mercifully, my sister Jean arrived with the repair kit and we somehow managed to rebuild and camouflage the damage just in time.

Flourless orange cake

Makes one 26cm cake

200g caster sugar

100g brown sugar

6 medium free-range eggs

2 oranges, boiled for 1 hour until soft (save the cooking water, quarter and remove pips, do not peel!)

250g ground almonds

1½ tsp baking powder

For the syrup:

150g caster sugar

Reserved cooking water (see above)

1 Preheat the oven to 170°C/150°C fan/gas 3.

2 Put the sugars and eggs into a food processor, or use a bowl with a hand-held blender, and slowly blitz to a smooth paste.

3 Add the orange pieces and blitz.

4 Add the almonds and baking powder, and blitz again.

5 Pour into a 26cm cake tin lined with baking parchment and bake for 1 hour and 20 minutes. Check with a skewer to ensure it’s cooked in the middle (the skewer will come out clean).

6 Meanwhile make the syrup. Stir to dissolve the caster sugar in the cooking water and boil for approximately 20 minutes.

7 Pour the syrup over the cooling cake while still in the tin. Allow to soak in and cool before turning it out onto a plate.

For a cake with more moisture:

Zest and juice a third orange and add to the cooking water with the 150g of sugar. Boil for 20 minutes or so, until you have a syrup, and drizzle this on top sparingly (save some of the boiled zest for decoration). Simply dry the zest on kitchen paper and sprinkle on top once the cake has cooled.

THE SCULLERY AND THE STAGE

Our kitchen, the scullery, was a tiny room barely ten by eight feet that housed a sink, table top and stock cupboards. All hot food was cooked on the range in the living room. After a few years Mum somehow added a hob into that tiny spot. Historically, the scullery was a room in the depths of the great mansions that was used for washing dishes and the landlord’s dirty clothes. My mum somehow managed to feed a small nation from that room. A curtain divided the scullery from a living room, the hub of many Hanrahan activities. There we drank early-morning milky egg whips, and ate breakfast, lunch and tea around a large adjustable table. Saturday dining was flexible but Sunday was the full show, a roast followed by a dessert of homemade jelly with ripple ice cream or Mum’s delicious trifle.

In the evenings after tea, a light meal, we had a group huddle around the Philips valve radio, which soon gave way to the Bush television. That room also hosted the All-Star Hanrahan Family Revue, a concert performance for visiting relatives and friends, with each of us lined up for curtain call to perform our party piece. We all played an instrument or danced, so every available space in the house was taken for practice for our many musical endeavours. Mam and Dad were very much associated with Comhaltas Ceoltóirí Éireann, an organisation founded in the 1950s to preserve Irish culture and music. They attended local meetings and assisted at all local fleadhs, with my mother and her friends making hundreds of sandwiches, and Dad along with his mates preparing and cleaning halls and rooms for performance or competition. I sang and played tin whistle with my brothers Joe, Kieran, Ger and a couple of other neighbours in the St Michael’s Céilí Band, performing at charity and village variety concerts. My sisters Gay and Jean along with other neighbours provided the dancing spectacle. Once a week we had music lessons with the great Frank Custy at the national school in Toonagh, where I won my first and only Fleadh Cheoil medal for singing the ballad ‘Kevin Barry’. I must have been only eleven or twelve. One summer, the carnival came to town and we all entered the talent contest. One by one they went to the podium, belting out reels, jigs and hornpipes at a very high standard. I went up and blurted out a rickety version of ‘Lily the Pink’ and took the crown – well, a shilling, but it was as good as any crown to me. My very talented brothers and friends were not at all amused.

PRAY FOR US

The living room was also a central room of prayer under the watchful eyes of the Sacred Heart, the child of Prague, the mother of Perpetual Succour and the Lord himself staring down from his crucifix. Every night we knelt to recite the longest Rosary in the history of the Catholic Church, with Hail Mary, Holy Mary, Hail Mary, Holy Mary, followed by the Glory Be into a litany of add-ons that included Prayers for the Faithful, blessings for the departed, those suffering sickness or hospitalised, relatives starting new jobs, sitting exams or heading off to foreign shores. We counted down the various mysteries on our fingers, keeping our eyes tightly shut to avoid any sibling contact for fear of the giggles and Dad’s severe reprimand. The Angelus bells were respected twice a day, everything stopped as we recited a special Angelus prayer, and we always did the First Friday, a devotion that required you to attend Mass and receive Communion on nine consecutive First Fridays of the month. Miss one, and you had to start it all over again. Rewards included a ticket to eternal life, a peaceful home, comfort in affliction, mercy and a guarantee of grace, glory and sanctity in death. It was a heavenly-brownie-point feast day. I served as an altar boy for the Franciscan Friary and the Poor Clares, an enclosed monastery of beautifully serene, pious and, frankly, adorable nuns. They lived their lives behind mesh walls tending their little farm and they showered us with their love, smiles and, after every Christmas and Easter midnight Mass, with sweets and chocolate. My favourite religious service was evening benediction with its Latin prayers, beautiful hymns and the swinging of the thurible with its sweet scent of incense and charcoal.

PORK CHOPS AND A CUPPA

Beneath the Sacred Heart of Jesus was our Stanley range, which was constantly on the go to produce the most amazing stews, roasts and Mum’s famous pork chops. I loved her pork chops. After a slow pan-fry, she added sliced onions and a cup of leaf tea and allowed them to simmer for a while. It was a recipe passed down from her own mother, who maintained that it added flavour, keeping the pork moist while creating its own very distinct gravy. It was succulent, tasty and legendary. I always thought it was a family dish, and when I suggested Mum’s method recently in reply to a recipe query on Twitter, the reaction was overwhelming. Turns out there’s an ancient tradition of tea-brining, with a definite historic link to Ireland and Scotland.

DAD

Firefighter won’t you come and take my pain away,

Firefighter bring me water, dampen down the flame.

– ‘Firefighter’, What You Know (2002)

My dad, Jackie Hanrahan, was a powerful influence on my life, his great strengths being his solid character, great sense of humour and unyielding commitment to his wife and family. My parents shared a very deep love that certainly bound us all together as a family. I have often wondered how they remained intact through all the difficulties and pressures of raising eight children. I cannot recall ever hearing my mother and father argue or show disrespect to each other. If they did, it occurred in the dead of night, far away from our young eyes and ears.

He worked for the Clare County Council, initially in the supply stores and then as manager of the Ennis swimming pool, which was a great addition to the town and to our lives. We practically grew up in the water and came to be known to some as ‘the Cousteaus’. Our instructor was Dad’s great friend Tom Finnegan, who was the size of four very large men. To pass through the grades in water safety, you had to rescue him from the deep end of the pool. As you approached, he splashed, reached out his long arm, grabbed your tiny head in his hand and held you firmly underwater for seconds, raised you aloft and pronounced ‘Failed!’ before sending you back for another attempt. This went on until he was convinced that you had conquered the fear of approach, could swim round him and grab him from behind. He was a superb teacher who helped many of us to become very capable swimmers.

My father smoked a lot but never drank. At sixteen he was caught drinking at a neighbour’s house party and a horrible uncle force-fed him beer slops until his face turned green. Some uncle! Dad never drank again, although in his last few months he confided that he sometimes regretted not going for a few pints with his family.

Dad was a home bird, and especially loved the garden, and most of all his shed. His shed housed everything imaginable for DIY, and was a great source of peace and fulfilment for him. One year, he made nine Christmas stables, one for each of the family, with hazel sticks collected from the crag at the back of our house. He painstakingly cut hundreds of sticks to size, fixed them side by side to form three walls, made a roof and thatched it. Each stable measured two feet by one foot with straw scattered on a flat sheeted floor, peopled with a set of religious figurines. A coloured bulb was pushed through the back wall with a lead and plug hidden from view. They were works of incredible patience, and without doubt the most beautiful Christmas gift I have ever received – and I a very lapsed Catholic.

When I was a kid, he helped my brother Kieran and friend Vinny McMahon to build a wooden table soccer game. As kids we often called to Carmel Healey’s games room in town, and as Kieran had become quite the champion, he had taken the notion to build his own for home practice. Dad built the wooden stadium from a sheet of plywood, measured to perfection, with two goalkeepers and twenty outfielders all made from half-inch heavy black tubing, fixed firmly to wooden rods fed through holes perfectly measured on the table walls. Two goal mouths completed the scene. A box of table tennis balls gave the neighbourhood many great days of entertainment, and the very enterprising Kieran and Vinnie made a small fortune by charging everyone a penny a game.

I spent a lot of time in the garden with Dad, growing spuds, cabbages, carrots, rhubarb, lettuce and spring onions, forever planning for the following year. I read a gardening magazine piece on how to grow the perfect carrot by sifting all pebbles from the ground to allow the carrot free passage to grow to perfection, so I suggested it to Dad. I knew by the ‘Oh holy God’ look on his face what he really thought, but he replied, ‘Whatever you think yourself, away with you a stór (a beautiful Clare term of endearment). I’ll get the screed, and you can start sifting away.’

I dug the appointed plot and painstakingly sifted about a square metre area free of all pebbles and rocks. I was exhausted, but I think Dad was even more exhausted looking at me. However, my efforts were rewarded with perfectly straight carrots – which tasted exactly the same as regular ones. I think I missed the rugged shape of the old carrots, so the following year we reverted to the traditional method, stones and all. I have come to really appreciate and understand his attitude, and what stayed with me from my life with him was his constant encouragement to follow an idea or a dream. He never saw any harm in attempting the impossible, even if it meant spending needless hours and hours sifting pebbles from a patch of ground. It was all about making the effort and doing your best.

At twelve I started playing my brother Ger’s nylon-strung guitar. A young Franciscan priest, Pat Coogan, had recently arrived in Ennis and was playing soccer with our local team, St Michael’s FC. He played guitar and gave me my first lesson. One day, I sat down on my bed and heard a crack: I’d shattered my guitar. To the day he died, Dad was convinced that I did it on purpose to get myself a better instrument. I denied it at the time, but in hindsight he may have been right because I’d had my eye on an Egmond steel-string guitar in Tierney’s music shop. I eventually bought the guitar, along with my first Leonard Cohen album and book of songs. I was besotted with Cohen and started teaching myself his guitar technique from a system included in the songbook. Every day after that I flew through homework to get to my bedroom to sing his songs. After about six songs, Dad would shout up, ‘Have you learned that song yet, Mikie?’ Yeah, Dad, thanks … You just don’t understand.

Despite the monotony, his encouragement never waned, and I even heard him reassure a mother distraught to hear that her son wanted to become a professional musician: ‘Sure, Mary, as long as he has a guitar on his back, he won’t go hungry.’

STRAUSS AND THE TULLA CÉILÍ BAND

When we were very young Dad bought a Philips record player and the most curious, eclectic collection of records imaginable. There was Strauss with the shimmering strings of ‘The Blue Danube’, the Tulla Céilí Band, the Dubliners with ‘Waxie’s Dargle’, Larry Cunningham, Donal Donnelly, Tom Jones, Doris Day, the Kilfenora Céilí Band and the Beatles. Our first record player was a turquoise blue, portable foldaway that looked like a suitcase. It had a turntable, a three-way speed switch for singles, albums and old 78s, two buttons, one for on/off and the other for volume, but that little box created the most incredible sounds that filled the entire house. I can still hear ‘Take me back to the Black Hills, the Black Hills of Dakota’ from Doris Day, with my mum’s beautiful soft voice singing along. Later, Dad bought a very fancy console-style stereo all in one, with radio, turntable, storage racks and speakers encased in a beautiful mahogany cabinet. Our record players were hardly ever silent and our record collection grew every week.

THE SUMMER JOBS

As soon as we reached our teenage years, we found gainful part-time employment at various shops in the town. I worked at Morgan McInerney’s hardware store in the market square, which sold everything from teapots to bags of cement. I was entitled to a staff discount, so all birthday and Christmas gifts carried a hardware theme. Mum’s were usually kitchen gadgets: a four-egg poaching pan complete with lid; a fancy cheese grater; a tomato slicer that required extra-special skills to avoid slicing fingers; and Dad’s favourite kitchen mate, the potato chipper, which he used every Saturday for our eagerly anticipated special treat. He loved that chipper, and we devoured each and every equally-sized chip it cut, the smell rising from the sizzling basket of Mazola oil, chips drained and sprinkled with salt, soaked in malt vinegar and served up with a good dollop of ketchup. Now that’s a food memory that’s hard to beat – unless you add a soft-fried egg.

Going to work at an early age was good for us, and my mum was delighted with the extra few bob. We worked all summer, Christmas, Easter and every Saturday during school terms. My brothers Joe and Adrian also worked at the hardware store, and Ger and Kieran worked in a shoe shop, which made runners the thing for Christmas morning. My poor sisters Gay and Jean were confined to barracks-cleaning and sweeping the homestead.

Work was not at all taxing as I recall. I spent much of my time tidying the many stores of cement, timber, paint and plumbing pipes. On Saturdays I had to polish and shine the proprietor Jack Daly’s silver Jaguar, and to this day I still want to own my own Jag. The rest of the day was spent serving behind the counter, or running errands for the staff, which took me to various locations around the town. One day I was taken by Mr Daly to see Joe Leyden, who had called in sick. Joe was a simple man who did odd jobs around the shop and spent the rest of his days sitting at the Daniel O’Connell monument in the middle of the town, watching the world go by. As we entered his house on Parnell Street a darkness like no other engulfed us. Mr Daly threw open the curtains and as my eyes readjusted, I reeled at the sight: hundreds of old newspapers piled high on an earthen cottage floor, a table in the corner with books, empty bottles, teacups and a vase of faded flowers. The kitchen was full of unwashed dishes and yet more newspapers and magazines. An open door led us to a bedroom where Joe lay moaning in pain. He was later moved to hospital and recovered to live another day.

Years later that visit was the inspiration for ‘Indians and Aliens’, a song about a very misunderstood young man who read accounts of the Trail of Tears march of American-Indian tribespeople across rough terrain that left many dead along the way, and of the massacre of the Lakota at Wounded Knee by the US Army. In a rage, he returned to his schoolhouse, a metaphor for those who instilled in him a deep-seated prejudice against the Indian nations. He burned it to the ground, and society, rather than seek to understand his troubled mind, shunned him and forced him into an institution. Joe, like the character in the song, was very misunderstood, and bore the brunt of many jibes from locals, young and old. I often wondered what went on in his mind as he sat on the monument looking down on the town. Many of us can relate to a degree; I was also that boy burning down the schoolhouse by the river. Mine had controlled my world through religious doctrine and fervour.

He was a simple man who loved Star Wars and John Wayne,

Lived in a little house, a little down and out, but that was his way.

Nightmared on Geronimo and the Empires of Doom

All alone in a little town, all he ever knew

Was Indians and aliens, Indians and aliens, coming for me and you.

– ‘Indians and Aliens’, What You Know (2002)

ARE YOU RIGHT THERE, MICHAEL, ARE YOU RIGHT?

On Sundays we jumped on an early bus to seaside Lahinch, which lies between Ennistymon and the majestic Cliffs of Moher. These days its ferocious waves attract thousands of surfers who want to test their skills on tough Atlantic breakers all year long. When we were kids, the great attractions were an amusement park of chair-o-planes, high swings, bumper cars, carousels and an outdoor swimming pool with a diving board that reached way up into the sky. The beach stretched for miles, and we crept through myriad sand dunes to spy on kissing couples. We ate boiled periwinkles and dried sea grass served in little chip bags from the vendors on the promenade, or instead settled on burgers and ice creams at the entertainment and games centre across the street.

THE BALLROOM OF ROMANCE

At weekends my dad collected tickets at the local dance hall, Paddy Con’s, later the Jet Club. The hall now operates as Madden’s furniture shop, and Michele Madden and her daughters protect the history and heritage of the building with pride and dedication. Its balconies, stage and heavily sprung hardwood floor are still intact. The memories come flooding back every time I stroll from balcony to floor, feigning an avid interest in some nest of tables or chaise longue on display. As I climb the stairs to the stage, I inhale a welcome breath of nostalgia – but I never feel alone, as I’m well aware that some of Madden’s other customers are doing the very same, soaking up the energy that lingers from this once vibrant ballroom of romance. I often helped Dad sweep the floors, stack chairs or clear out the dressing rooms, and constantly badgered him to bring me along to meet the bands as they arrived for the evening show. I remember meeting Butch Moore the year after he represented Ireland at the Eurovision Song Contest singing ‘Walking the Streets in the Rain’. I met all the stars of the day, Larry Cunningham, Brendan Bowyer, Dickie Rock, Margo, the Clipper Carlton, Gerry and the High-Lows, the Drifters, the Miami, the Cadets, the Premier Aces and my favourite of all, the Cotton Mill Boys. Of all the people I saw perform there, fiddler Sean McGuire stands apart. I still remember his breathtaking versions of ‘Hungarian Gypsy Rhapsody’ and ‘The Mason’s Apron’. I met him many times in later years and realised a dream when we shared a stage and a few tunes at the Ulster Hall in Belfast.

reproduced with kind permission of the Clare Champion

All I ever wanted was to be up there on that high stage. Whenever I call in to check out the latest furniture deals, I close my eyes and see a crowded hall, a sparkling mirror-ball casting its glitter across a pulsating dance floor. I can still feel that sinking sensation when a beautiful girl refuses or ignores your invitation to dance, or worse, when your pal beats you to the chase. As a young teenager I would play that hall on many occasions in a rock band called Effigy, and those nights at Paddy Cons ignited a flame within me that still burns.

THE GARDEN OF ROSES

As a twelve-year-old I harboured ideas of a religious vocation, choosing the Order of St John of God following a visit by a brother to our school on a recruitment mission. Three of us were taken to a seminary in Celbridge, County Kildare, for a trial retreat. It was my first time being so far away from home, and I felt isolated in that seminary. Even though there were lots of people moving around, sports fields surrounded by beautiful tree-lined avenues, large dormitories, lovely food, altars and lots of prayers, I still felt alone.

On my return, my mother and I discussed the visit and she insisted that I really think about what I wanted to do. ‘Mike, I hope you’re not doing this for me or your father, because that would not be right. If you don’t want to go, then please tell me, and that will be the end of it.’ When I told her I wanted to stay at home she said, ‘Good, that’s that, then.’

We never spoke about it again until many years later when she confided she was thrilled with my decision, as she dreaded the prospect of me living away from home at such an early age. Crucially, though, she reiterated that she would have supported me either way. Mum and Dad often pointed out possible obstacles but never ever put one in our way.

As a young teen I was a true believer, and very dedicated to the Catholic Church. I spent a lot of time as an altar boy in the local Friary. It was a beautiful place and most of the Franciscans were wonderful people. We had many visiting priests and brothers who came to spend time at the centre, and when I was about fourteen, maybe fifteen, a regular visiting Franciscan brother came to our house to ask my mother for permission to take me to Galway for a weekend retreat. He sat with my mother and grandmother drinking tea, talking God and Church and praising my work at the Friary. He blessed them both and followed me out to the hallway, closing the door behind him. In the privacy of the hallway he enquired about my girlfriends, their names and which one I liked best. He began poking and feeling around my genital area, asking me if I liked it. I felt trapped, and was extremely uncomfortable. I didn’t know what to do. He continued until I managed to get to the front door. I begged him to leave me alone. As he pushed past, I noticed a lot of dandruff on the collar of his brown robe. That’s how I still remember him today. I felt ashamed, and almost dirty. I made up some excuse for turning down the trip to Galway, and I left it there in that hallway for years and years and tried not to think about it. Years later, I was walking down Abbey Street in Dublin when I spotted him coming towards me. I panicked, and hid in a doorway. As he walked by, all I noticed was the dandruff. It was still there. I wanted to scream at him, but I had no voice. I was still scared, or perhaps ashamed. I was twenty-one years of age. I never saw him again.

We all knew that certain priests in the parish were ‘dodgy’ – many altar boys relayed stories of hands slipping into their trousers. Some of us eleven- or twelve-year-olds were once brought into the office one by one by a Franciscan priest, who said he was to show us some ‘personal hygiene’ habits. He said our parents had requested it, but that we were bound to silence, as they were far too embarrassed to broach the subject further. Best keep it to ourselves. Yes, Father. Among ourselves we knew there was something wrong. We had our names for them, and we tried to steer clear of their advances and warn the younger boys, but the overriding reality was that we had a dedication to a church that controlled every aspect of our lives – and that’s where their power lay.

I have never forgotten those instances of abuse, and unfortunately to this day I still harbour a deep sense of personal responsibility for allowing them to have occurred in the first place. I have had to wrestle with that guilt every time it finds its way to the surface. I certainly felt betrayed. Thankfully, I do not own that shame any more. Healing is powerful in that regard.

In 2001 I felt compelled to write and record a song called ‘Garden of Roses’ after all the harrowing accounts of cases of child abuse by religious orders, including one particular cleric close to home. Deep down I knew I had to speak to Mum about the song’s imminent release, and if I could, talk about my own experience. Words will never truly describe that profound moment between a mother and her son. We talked and cried a little but together crossed over into a very special place of understanding. I felt such a deep sense of relief because I knew she understood my hurt, and I in turn empathised with her own very personal pain.

In the garden of roses where you came by,

Beautiful roses, the eyes of a child

In your secret desire you cut it all down.

Now the petals lay scattered on tainted ground

In the garden of roses, beautiful roses.

Hot Press founder Jackie Hayden called me after hearing the song; he wanted permission to include it in his book In Their Own Words, a compilation of personal stories from abuse victims in the Wexford region to support the Wexford Rape Crisis Centre. I was invited to perform at a few very powerful and moving healing services where the song found its true home. The song continued to make an impression with listeners as the revelations kept coming, as it was included in a 2011 book, The Rose and the Thorn by Audrey Healy and Don Mullan. In the autumn of 2018, I was invited to perform the song once again, but this time at a day of remembrance for Ireland’s lost children at the site of the mother-and-baby home in Tuam in County Galway. It seems we have come some way from those terrible days of darkness. I certainly hope so. May the healing continue.

Now your temple has fallen, the walls cave in.

We witness the sanctum in their evil sin.

But a river once frozen deep in the mind

Flows on like a river should in the eyes of a child

In the garden of roses, those beautiful roses.

– ‘Garden of Roses’, What You Know (2002)

FAREWELL TO DAD

My dad died before the avalanche of abuse stories arrived, and I know he would have been shocked to the core. He was a very religious man, and like many of his generation lived by church rules and served without question. I have no doubt that I could have spoken openly to him about writing ‘Garden of Roses’. He would have listened and offered comfort, of that I am certain. His death in June 2000 had a profound effect on my life and my songwriting. Two years later I released the album What You Know. The title of the album is an expression he used for almost everything that he could not instantly put a name to. If he wanted you to get a paintbrush from the shed he might say, ‘Mikie, will you get the what-you-know from the shed, I want to finish that bit of painting. It’s in the box beside the what-you-know, the screwdrivers.’ You had to be on his wavelength, but we usually were.

A songwriter friend of mine once wrote of his dad’s passing, ‘The greatest man I never knew lived down the hall.’ It was such a sad song. I am glad to say I knew mine very well and we shared many great times together. When he was diagnosed with cancer, he was given nine weeks to live. Such was his strength and determination he lasted almost two years and faced it with great courage. Thankfully, I never had a slate to clean with him so we carried on as normal and tried our best to make the journey comfortable. His funeral was one of the biggest Ennis has ever seen, a testament to his wonderful personality and selfless generosity. He sits on my shoulder for every gig and I love to talk about him. He never got to see me in chef whites but I have absolutely no doubt it would have pleased him and he may have turned to Mum and said, ‘Sure, Mary, once he has a frying pan in his hand, he won’t go hungry.’

Take away the sad and lonely, all the trouble that surrounds him,

Firefighter won’t you come …

CHAPTER 2 (#ulink_19434bc6-45e6-5764-987b-4ad7d3f25dec)

DOOLIN (#ulink_19434bc6-45e6-5764-987b-4ad7d3f25dec)

See all the doors swing open,

Your life’s unfolding before your very eyes,

Such a strange affair,

Walk in around, come into the sound,

Forget you’re down, feel the air, beautiful affair.

– ‘Beautiful Affair’, Light in the Western Sky (1982)

McGANN’S PUB, DOOLIN, 2018

I’m sitting on an old bench in McGann’s pub on the rugged north-west coast of County Clare. The walls of old faded photographs come to life, evoking powerful memories of a bygone era. I feel this swell of emotion, exalted and suddenly aware of the significance of these amazing colourful characters who taught me so much all those years ago. Doolin, my gateway from innocence, where the petals of youth opened wide to drink in their first rays of glorious sunshine.

Doolin sits on the edge of the Burren, that mystical landscape of limestone rock and rugged terrain where creative energy finds comfort and a true home. They say that Tolkien was inspired to write The Lord of the Rings after spending time here; Dylan Thomas married a local woman and lived in Doolin for a time; George Bernard Shaw and J. M. Synge often wrote of its beauty. In the early 1970s a new generation of free spirits arrived in Doolin from faraway places, and though some passed on through, many remained and integrated to develop a very special community. Today that community thrives and continues to provide a haven for travellers, lovers, dreamers, musicians, poets and singers. It feels so good to be back again, and it feels like I’m home.

TOMMY McGANN

In 1976 Tommy and Tony McGann returned from America and bought a run-down pub in a very quiet and neglected area of Doolin about a mile east of the action on Fisher Street, where Micho Russell held court at O’Connor’s pub, singing and playing the whistle, entertaining fans and visitors from all over Europe. The pub had been owned by two Americans who had run out of money, forcing the bank to take over, and within a couple of years the building had fallen into disrepair. Their father, Bernie McGann, sold a little plot of his land in Kilmaley to finance his sons’ venture. Neither had any previous experience in the pub trade, which resulted in much trial and even more error in the early days. Although Tommy’s management skills were almost non-existent at that time, he found a way through, with a charm that came to define him and set him apart throughout his short life.

In that same year as they took up the pub, my secondary schooling came to an end at Rice College on the banks of the river Fergus, not far away in Ennis. I was a reluctant student to say the least; I had no interest in school apart from history and economics, the latter receiving most of my academic attention. The enigmatic Jody Burns, with his appearance and antics of a nutty professor, was a gifted teacher who managed to corner my full attention on matters of supply and demand. I duly received an A in my Leaving Certificate examination in economics, which was a great shock to many – but not to Jody Burns. He was very proud of my achievement but expressed great disappointment on hearing that I would not be going on to study economics in college. These days third-level education is a natural progression for so many students, but back in the 70s the order of the day for the majority of us school-leavers was to secure a ‘grand pensionable job’, settle down, buy a house and raise a family.

Little did I know while sitting those last exams that as soon as the school books hit the waters of the river Fergus, I’d be in a car on my way up to Doolin to play music with my brother Kieran and first cousin Paul Roche, right here in this very room where I sit today in McGann’s. During that first summer of freedom I shook off the shackles of a sheltered Catholic upbringing. I made many new friends, discovered love, expression and songwriting. I recognised early on that the fish and lamprey eels of the Fergus would benefit much more from my books than I ever did, while I concentrated my further education on the life and music of North Clare and beyond.

MY FIRST KITCHEN JOB

Up to the mid-40s transatlantic flights – mainly seaplanes – had to stop to refuel at Foynes in West Limerick on their way to continental Europe. During the Second World War Foynes became the busiest airport in the world. Shannon Airport was then established in 1945 as Ireland’s first international airport, and within a few years it became the world’s first duty-free airport, operating as a gateway between North America and Europe, as most aircraft still required refuelling for long-haul flights.

In that summer of ’76 I got a job as a kitchen porter in the airport’s ‘free-flow’ restaurant, doing my best to get to Doolin for our Tuesday and Thursday night sessions and up again on Friday evening for a weekend of music and craic. The job was supposed to be a stepping stone either to a culinary career or to a more secure position in the airport or surrounding industrial hub. The busy kitchen served passengers, flights, all airport staff and stocked all duty-free restaurants. Most of my day was spent either on wash-up or working the conveyor belt, which delivered mounds of dirty dishes and cutlery to the sinks. Life as a kitchen porter was non-stop grief, thanks in particular to an ogre of a chef who barked and bellowed orders through an early-morning fug of stale alcohol. Stockpots and skillet missiles whizzed past my right ear to rattle against the sides of the stainless-steel basin before sinking into an angry, greasy ocean of bobbing and weaving pots and pans. The two of us manning the station were not allowed to speak a word, but we soon developed early warning signals for any incoming, including the main man himself, who would storm over with a badly washed pot, reload and fire it back at us again with bonus expletives. By the end of lunch, his anger grew as his hangover craved its afternoon cure. His venomous eyes have stayed with me, but it was a lesson to me to learn my surroundings inside out.

My next-door neighbour and childhood friend Ken Shaughnessy also worked in that kitchen as a commis chef. He went on to culinary college and became an executive head chef for an international hotel chain in Germany. On the very rare occasions we meet, we toast many schnapps to our wonderful childhood, that kitchen and good old Cerberus. Perhaps he was the making of us after all, as our love of food survived and neither of us have ever tolerated kitchen bullies, no matter how important they consider themselves. I will never understand how aggressive chefs get away with humiliating people in their place of work.

I moved quickly from the kitchen to the duty-free mail-order department, packing and posting Waterford crystal, Belleek china, shillelaghs and leprechauns to exotic-sounding destinations like Pine Ridge, Vermont, Wyoming, Montana and Biloxi. I finally left Shannon to work with my friend TV Honan at a newly opened drop-in centre for teenagers in the old refurbished National School in Ennis. It was the first of its kind in Ireland, the brainchild of Sean Sexton, a very proactive, clued-in priest. We called it the Green Door after a short story by American writer O. Henry, a tale of romance, adventure and fate as we search for a door to opportunity. I often think that the story somehow reflected my decision to break free from that grand pensionable position to search for my own green door. With an unyielding determination to find a way to the music I convinced Mum and Dad by telling them my wages at the Green Door were higher than at Shannon, when in fact they were a lot lower, but I figured I could make up the loss from sessions and gigs.

ROOM WITH SEA VIEW

On my weekend visits to Doolin I slept behind the pub in a caravan and in tents beside the beautiful Aille River, or found a sleeping space in the upstairs restaurant. Come the morning there was the usual scurry to clear the beds and clean up last night’s fun to get ready for early lunch. One summer a group of German tourists found their way into a disused, dilapidated, roofless house at the entrance to Doolin pier, cleared it out, filled it with straw and hay and pinned a sign at the front entrance:

Doolin Hilton Hotel

All welcome

Please keep tidy

After closing time, we had some memorable nights at that waterfront Hilton. Everyone checked in, signed the guest book, played music, sang songs and listened to stories from all around the world. We heard about Aboriginal dream time, the Northern Lights, American Indians, Nordic folk tales and magical Dutch fairy stories, while smoking reefers and drinking beers on beds of straw beneath a blanket of sparkling stars. All strangers who entered left as friends. I fell in love there with Bebke Smits, a free-spirited young woman from Boxtel in the Brabant district of southern Holland. Bebke sang Dutch folk songs, wrote and recited deep and weird poetry, danced very freely and was extremely comfortable in her hippie skin. She introduced me to vegetarian food, and gave me my first Herman Hesse novel, Narcissus and Goldmund, a book I return to time and again. It’s a poignant tale about young Goldmund, who develops a friendship with a slightly older and more committed monk, Narcissus, at a monastery somewhere in Germany. Goldmund strays into the woods one night, where he meets a beautiful young woman who seduces him. The confused novice seeks counsel from the older Narcissus, who encourages him to leave the monastery and embrace life beyond the walls rather than remain in search of salvation. On the journey that follows, Goldmund becomes a talented carver but refuses to join the carving guild, preferring to continue unbound on his road to understanding. He meets and loves many other women along the way, and survives the Black Death and all its ugliness. Eventually he returns to his friend Narcissus, where in the monastery the artist and philosopher speak freely about their lives in a beautifully written story.