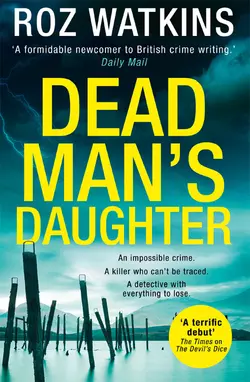

Dead Man’s Daughter

Roz Watkins

‘A formidable newcomer to British crime writing’ Daily Mail‘Outstanding’ Stephen BoothA gripping thriller set in the atmospheric Peak District, perfect for fans of Val McDermid, Broadchurch and Happy Valley***‘She was running towards the gorge. The place the locals call Dead Girl's Drop…’DI Meg Dalton isn’t prepared for her latest case. A ten year old girl is found running through the woods, barefoot and wearing only a blood-soaked nightdress. She has no memory of what happened to her, but her father is found stabbed to death in their nearby house.At first, Meg blames an intruder – but why had the girl's murdered father been so obsessed with the creepy statues in the woods, and with the girl's recent heart transplant?Meg's investigation leads her down a chilling path. The girl has been having nightmares, and seems to remember things that happened to her heart donor. Who was the donor and what happened to them? Could this have anything to do with the murder of the girl's father?Meg is forced to question her deepest beliefs to discover the shocking truth before the killer strikes again…

ROZ WATKINS is the author of the DI Meg Dalton crime series, which is set in the Peak District where Roz lives with her partner and a menagerie of demanding animals.

Her first book, The Devil’s Dice, was shortlisted for the CWA Debut Dagger Award, and has been optioned for TV.

Roz studied engineering at Cambridge University before training in patent law. She was a partner in a firm of patent attorneys in Derby, but this has absolutely nothing to do with there being a dead one in her first novel.

In her spare time, Roz likes to walk in the Peak District, scouting out murder locations.

Copyright (#uabbe8212-4249-5d61-b60d-08502f5d06f6)

An imprint of HarperCollins Publishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

First published in Great Britain by HQ in 2019

Copyright © Roz Watkins 2019

Roz Watkins asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Ebook Edition © April 2019 ISBN: 9780008214661

Praise for Roz Watkins (#ulink_8e52b2ca-f0ad-5587-9334-224efda47480)

‘The Devil’s Dice is a terrific debut by Roz Watkins; it teems with shivery atmosphere and introduces a cop quietly different from most of the women detectives in British crime fiction today.’

The Times Crime Book of the Month

‘A touch of Agatha Christie, a dash of Ann Cleeves’s Vera and a suitably moody setting in the Peaks . . . bring a formidable newcomer to British crime writing.’

Daily Mail

‘A fascinating debut . . . Watkins brilliantly balances superstition and scepticism in this clever first novel.’

Sunday Times

‘A fabulous book. I can’t wait to meet DI Meg Dalton again.’

B A Paris

‘An outstanding debut. The Devil’s Dice had me gripped from the start.’

Stephen Booth

‘Twisty, creepy, funny, and you may shed a tear too. More DI Meg Dalton please!’

Caz Frear

‘A page-turning debut featuring a fabulous lead character.’

Susi Holliday

‘A fascinating debut with a deliciously old school mystery at its heart. I can’t wait to see what Watkins does next!’

Angela Clarke

‘A pacy, twisty read that had me on the edge of my seat . . . what a brilliant debut!’

K.L. Slater

‘Exceptional debut. Beautifully written and observed crime novel, with such well-rounded maturity it was a pleasure to read from start to finish. Glad it is a series so that we all have a lot more to look forward to.’

Amanda Robson

For Rob.

(I still think we could have got away with a talking dog.)

Contents

Cover (#ud710f4f5-d4b7-5784-b48c-4c63f6041c1a)

About the Author (#u3c0e704a-7111-5ee5-b17d-7095858bde63)

Title Page (#u2b01a731-6058-53b5-9193-df4366a35806)

Copyright (#ulink_f706e495-d43e-5182-8dce-2dc3379a51a7)

Praise (#ulink_73ea79ad-088a-5ced-be2e-32611b674af9)

Dedication (#u50e45f4d-2455-5047-ae6a-ec19bc3e38c1)

Prologue (#ulink_a3d9bf08-649f-5f72-a8f1-7062146aaf58)

Chapter 1 (#ulink_bc190dc4-d3d5-5175-aad1-6b43c2ca81bc)

Chapter 2 (#ulink_7c9a5a46-a49e-54c6-a139-d916d9e4ea7d)

Chapter 3 (#ulink_454740eb-365d-540b-b2af-1656a5f3f586)

Chapter 4 (#ulink_e70e0c1a-3436-51a6-9a2d-84f154cf96d5)

Chapter 5 (#ulink_29f80435-0c15-5b2d-912b-9c1830331f65)

Chapter 6 (#ulink_2e119610-0dc5-5b70-9420-51ba278843af)

Chapter 7 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 8 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 9 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 10 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 11 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 12 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 13 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 14 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 15 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 16 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 17 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 18 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 19 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 20 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 21 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 22 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 23 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 24 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 25 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 26 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 27 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 28 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 29 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 30 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 31 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 32 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 33 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 34 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 35 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 36 (#litres_trial_promo)

Acknowledgements (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

Prologue (#ulink_495c5036-5673-50b4-9a5b-7db3e0054ad8)

She lay on her back, hard metal under her, so cold it felt like being punched. The smell of antiseptic scorched her throat. She couldn’t move.

She tried to scream. To tell them not to do it. She was still alive, still conscious, still feeling. It shouldn’t be happening. But no sound came.

The man had a knife. He was approaching with a knife. Silver glinted in the cold light. Why could she still see? This was wrong.

With all her will, she tried to shrink from him. He took a step closer.

Another man stood by. Dressed in green. Calm. They were all calm. How could they be so calm? She must be crying, tears streaming down her face, even if her voice and her legs and her arms wouldn’t work.

Please, please, please don’t. Inside her head she was begging. Please stop. I can feel. I’m still here. I’m still me. No words came out.

The terror filled her; filled the room.

The knife came closer. She couldn’t move. It was happening.

The touch of steel on her skin. Finally a scream.

One of the men placed his hand on her mouth.

The other man pushed towards her heart.

1. (#ulink_0b4c197d-c37c-586f-9a42-e51306452aae)

The woman grabbed my hand and pulled me deeper into the woods. Her voice rasped with panic. ‘She was running towards the gorge. The place the locals call Dead Girl’s Drop.’

That didn’t sound good, particularly given the Derbyshire talent for understatement. I shouted over the wind and the cracking of frozen twigs underfoot. ‘What exactly did you see?’

‘I know what you’re thinking, but I didn’t imagine it.’ Strands of dark hair whipped her face. She must have only been in her forties, but she looked worn, like something that had been washed too many times or left out in the rain. She tugged a similarly faded, speckled greyhound behind her. ‘I was expecting proper police,’ she added.

‘I’m a detective. DI Meg Dalton, remember? We wear plain clothes.’ No matter what I wore, I seemed to exude shabbiness. I was clearly a disappointment to Elaine Grant. I sneaked a glance at my watch. I’d had a phone-call from my mum that I should have been returning.

Elaine tripped on a stump and turned to look accusingly at me, her edges unclear in the flat morning light. ‘Pale like a ghost. The dog saw her too.’

I glanced down at the dog. He panted and drooled a little. I wasn’t sure I’d rely on his testimony, but I couldn’t afford not to check this out. I shivered and pulled my scarf tighter around my neck.

‘Wearing white, you mean? But you saw blood?’

‘It was a nightdress, I think. Just a young girl. Streaking through the trees like she had the devil at her heels. And yes, there was red all over her.’

Branches rattled above us. Something flickered in the corner of my eye – shining pale in the distance. My breath stopped in my throat and I felt a twitch of anxiety. ‘Is there a house in these woods?’ I asked. ‘Approached down a lane?’

Elaine walked a few steps before answering. ‘Yes. Bellhurst House.’

I knew that place. The woman who lived there had kept calling the police, saying she was being watched and followed, but she’d had nothing concrete to report. After the first time, they’d joked that she had an over-active imagination. Possibly a fondness for men in uniform. And we hadn’t taken her seriously.

Elaine touched my arm. ‘Did you see the girl?’

We waited, eyes wide and ears straining. The dog let out a little affronted half-bark, more of a puff of the cheeks. A twig snapped and something white slipped through the trees.

‘That’s her,’ Elaine shouted. ‘Hurry! The gorge is over there. Children have fallen . . . ’

I re-ran in my mind the control room’s leisurely reaction to this call; our previous lacklustre responses to the woman in the house in these woods. A band of worry tightened around my chest. I pictured a little girl crashing over the side of the gorge into the frothing stream below, covered in blood, fleeing something – something we’d been told about but dismissed. Maybe this was the day the much-cried wolf actually showed up.

I broke into a limping run, cursing my bad ankle and my bad judgement for not passing this to someone else. I couldn’t take on anything new this week.

The dog ran alongside me, seeming to enjoy the chase. I glanced over my shoulder. If the girl had been running from someone, where were they?

I arrived at a fence. A sign. Private property. Dangerous drops.

Elaine came puffing up behind me.

I was already half over the fence, barbed wired snagging my crotch. ‘Did you see anyone else?’

‘I’m not sure . . . I don’t think so.’ She stood with arms on knees, panting. She wasn’t in good shape. ‘I can’t climb over that fence,’ she said. ‘I have a bad knee.’

‘You wait here.’ I set off towards where I’d seen the flash of white. The dog followed me, pulling his lead from Elaine’s hand and performing a spectacular jump over the fence.

The light was brighter ahead where the trees must have thinned out towards the gorge. I could hear the river rushing over rocks far below. My eyes flicked side to side. There was something to my left. Visible through the winter branches. ‘Hello,’ I shouted. ‘Are you alright?’ I moved a step closer. A figure in white. I hurried towards her. She was uncannily still.

I blinked. It was a statue, carved in pale stone. Settled into the ground, as if it had been there for centuries. A child, crying, stone tears frozen on grey cheeks. I swore under my breath, but felt my heart rate returning to normal.

Was that something else? It was hard to see in the dappled light.

A glimpse of pale cotton, the flash of an arm, a white figure shooting away. I followed. There in front of me another statue. Whereas the first child had been weeping, this one was screaming, mouth wide below terrified eyes. I shuddered.

I ran towards the noise of the river, imagining a child’s body, smashed to pieces by stone and current. I didn’t need a dead girl on my conscience. Not another one. I’d been good recently – not checking my ceilings for hanging sisters or hoarding sleeping pills. I wanted to keep it that way.

‘Hello,’ I shouted again. ‘Is there anyone there?’

A face nudged out from behind a tree which grew at the edge of the gorge.

It was a girl of about eight or nine. She was wearing only a white nightdress. Her face was bleached with fear and cold, her hair blonde. The paleness of her clothes, skin, and hair made the deep red stains even more shocking.

I took a step towards the girl. She shuffled back, but stayed facing me, the drop falling away behind her. She must have been freezing. I tried to soften my body to make myself look safe.

The dog was panting dramatically next to me, after his run. He took a couple of slow steps forward. I was about to call him back, but the girl seemed to relax a little.

The dog’s whole body wagged. The girl reached and touched him. I held my breath.

The girl shot me a suspicious look. ‘I like dogs.’ Her voice was rough as if she’d been shouting. ‘Not allowed dogs . . . Make me ill . . . ’

‘Are you running from someone?’ I had to get her away from the edge, but I didn’t want to risk moving closer. ‘I’m with the police. I can help you.’

She stared at me with huge owl eyes, too close to the drop behind.

Heart thumping, I said, ‘Shall we take him home for his breakfast?’ The dog’s tail wagged. ‘Is that okay?’

She shifted forward a little and touched the dog softly on the head. A stone splashed into the water below. ‘He needs a drink,’ she whispered.

Elaine had been right. The girl’s nightdress was smeared with blood. A lot of blood.

‘Okay,’ I said. ‘Let’s take him back for a drink and some breakfast. Shall we do that?’

The girl nodded and stepped away from the edge. I picked up the end of the lead and handed it to her, hoping the dog would be keen to get home. I wanted the girl inside and warmed up before she got hypothermia or frostbite, but I sensed I couldn’t rush it.

I walked slowly away from the gorge, and the dog followed, leading the girl. Her feet were bare, one of her toes bleeding.

‘What’s your name?’ I asked.

I thought she wasn’t going to answer. She shuffled along, looking down.

‘Abbie,’ she said, finally.

‘I’m Meg. Were you running from someone?’ I shot another look into the trees.

She whispered, ‘My dad . . . ’

‘Were you running from your dad?’

No answer.

I tried to remember the substance of the calls we’d had from the woman in the house in the woods. Someone following her. Nothing definite. Nothing anyone else had seen.

‘Are you hurt? Is it okay if I have a look?’

She nodded. I crouched and carefully checked for any wounds. She seemed unharmed, apart from the toe, but there were needle marks on her arms. I was used to seeing them on drug addicts, not on a young girl.

‘I have to get injected,’ Abbie said.

I wondered what was the matter with her. My panic about her welfare ratcheted up a notch. I grabbed my radio and called for paramedics and back-up.

‘There’s a stream,’ Abbie said. ‘He needs a drink.’ The dog was still panting hard.

‘No, Abbie. Let’s – ’

She veered off to the right, surprisingly fast.

‘Oh, Jesus,’ I muttered.

Abbie pulled the dog towards the pale statues, darting over the bone-numbing ground. I chased after her.

There were four statues in total, arranged around the edge of a clearing. They were children of about Abbie’s age or a little younger, two weeping and two screaming, glistening white in the winter light. I ran between them, spooked by them and somehow feeling it was disrespectful to race through their apparent torment, but Abbie was getting away from me.

I saw her ahead, stepping into a stream so cold there were icy patches on the banks. ‘No, Abbie, come this way!’ I ran to catch up, wincing at the sight of her skinny legs plunging into the glacial water.

She called over her shoulder. ‘He can drink better at this next bit.’ She clutched the dog-lead as if it were the only thing in the world. I was panicking about her feet, about hypothermia, about what the hell had happened to her, and who might still be in the woods with us. But she was determined to get the dog a drink. And I sensed if I did the wrong thing, she’d bolt.

‘Abbie, let me carry you to the drinking place, okay? Your feet must be really sore and cold. We’ll get him a quick drink, then head back and get warmed up.’

She looked at her feet, then up at me. Worried eyes, blood on her face. She nodded, and shifted towards me.

I reached for her, but she lurched sideways and fell, crashing into the freezing water. She screamed.

Heart pounding, I reached and scooped her up. She was drenched and shivering, teeth clacking together. I pulled her inside my coat, feeling the shock of the water soaking into my clothes. I took off my scarf and wound it loosely around her neck.

I stumbled through the mud, filling my boots with foetid bog water, and finally saw a larger stream ahead, flowing all bright and clear. The dog immersed his face in it, gulped for a few moments, and looked up to show he was done.

‘Right, let’s go.’ I shifted Abbie further up onto my hip and limped back in the direction we’d come, trousers dragging down, feet squelching in leaden boots. The dog pulled ahead, shifting me off-balance even more. Through the boggy bit again, past the cold gaze of the statues, and at last to the fence where Elaine was waiting.

‘Oh, thank goodness!’ Elaine said. ‘She’s alright.’

I gasped for breath. ‘Could you go on ahead and put your heating on high? It could take a while for the paramedics to get here. We might need to warm her up in your house. She’s frozen.’

‘Shall I run a bath? Not too hot. Like for a baby.’

‘No, it’s okay. Just the heating.’

‘Like for my baby.’ Her eyes seemed to go cloudy. ‘My poor baby.’

I touched her lightly on the arm. ‘I’ll bring the girl back. Just put the heating on high and get some blankets or fleeces or whatever you have, to wrap round her.’

Elaine nodded and helped me lift Abbie over the fence, before heading off at a frustratingly slow walk.

I picked Abbie up again. ‘Not far now,’ I said, as much to myself as her. ‘We’ll get you inside and warmed up.’

‘Thank you,’ she said in a tiny voice. ‘Thank you for letting me get a drink for the dog.’

Her ribs moved in and out, too fast. That could be the start of hypothermia. I clasped her to me, enveloping her in my jacket and pulling the scarf more snuggly around her neck.

My feet were throbbing, so I dreaded to think what hers felt like. ‘Where do you live, Abbie?’ I said.

‘In the woods.’ She held on to me with skinny arms, trusting in a way which brought a lump to my throat. She rested her head against my shoulder. Her voice was so quiet I could barely hear. ‘I’m tired. . . Will you make sure I’m okay?’

I swallowed, thinking of all that blood. I could smell it in her hair. ‘Yes,’ I whispered into the top of her head, ignoring all the reasons I couldn’t make any promises. ‘I’ll make sure you’re okay.’

*

We eventually arrived at the edge of the woods, and crossed the road to reach Elaine’s cottage. I hammered on the door and it flew straight open. I wrenched off my muddy boots and sodden socks, followed Elaine through to a faded living room, and lowered Abbie onto the sofa.

‘Get some blankets around her,’ I said. ‘I’ll be back.’ I dashed barefoot over the road to my car, grabbed some evidence bags, and slipped my feet into the spare trainers I’d shoved in there in a fit of sensibleness. My toes felt as if they’d been dipped in ice, rubbed with a cheese-grater, and held in front of a blow-torch.

Back at the house, Elaine had swaddled Abbie in a couple of towels and about five fleecy blankets that looked like they could be the dog’s. I decided it was best not to smell them.

‘Do you have anything she could wear?’ I asked. ‘So we can get that wet nightdress off her?’

Elaine hesitated. ‘I still have . . . ’

Abbie looked up from her nest of fleeces and mumbled, ‘Where’s the dog?’

Elaine called him, and Abbie stroked the top of his head gently, her eyelids drooping, while Elaine went to fetch some clothes.

The room was clean and tidy but had a museum feel, as if it had been abandoned years ago and not touched since. Something caught my eye beside the window behind the sofa. A collection of dolls, sitting in rows on a set of shelves. I’d never been a fan of dolls and had dismembered those I’d been given as a child, in the name of scientific and medical research. And there was something odd about these. I took a step towards them and looked more closely.

A floorboard creaked. I jumped and spun round. Elaine stood in the doorway, holding up some soft blue pyjamas. ‘These?’ They must have belonged to a child a little older than Abbie.

I nodded, walked over and took the pyjamas, then sat on the sofa next to Abbie. I opened my mouth to thank Elaine and ask if she had a child of her own, but I glanced first at her face. It was flat, as if her muscles had been paralysed. I closed my mouth again.

I persuaded Abbie to let me take off the sopping-wet, blood-soaked nightdress and replace it with the pyjamas. Her teeth chattered, and she clutched my scarf. I put the nightdress in an evidence bag.

‘My sister Carrie knitted that for me.’ I was better at saying her name now. ‘When I was very young. It’s the longest scarf I’ve ever seen.’

Abbie touched the scarf against her cheek, closed her eyes and sank back into the sofa.

I looked up at Elaine. ‘Do you know if she lives at Bellhurst House? She said she lived in the woods, but she’s pretty confused.’

Elaine stared blankly at me. ‘Yes, I suppose she must. They own the land that goes down to the gorge.’

A pitter-patter of my heart. The guilt that was so familiar. Again I tried to remember what the woman from Bellhurst House had reported. Someone in the woods, someone looking into their windows, someone following her. She hadn’t lived alone; I remembered that. There was definitely a husband, possibly children.

‘Is that your house, Abbie? Bellhurst House?’

She nodded.

‘A car went down there,’ Elaine said. ‘In the night. I couldn’t sleep. Down the lane. I didn’t think much of it at the time. But now I’m wondering . . . ’

‘What time?’

‘I’m not sure exactly. About three or four, I think.’

‘Okay,’ I said. ‘Police are on their way to the house. What colour was the car?’

‘I couldn’t see – it was too dark.’

I turned to Abbie. ‘Do you remember anything about what happened?’ I said. ‘Where the blood came from?’

She leant close to the dog and wrapped her arms around him. He gave me a long-suffering look. Abbie spoke softly into his ear, so I could barely make out the words. ‘Everyone always dies. Jess. And Dad . . . ’

I looked at her blood-stained hair. ‘Who’s Jess?’

‘My sister.’

I imagined her sister and her father bleeding to death in those dark woods, surrounded by statues of terrified children. ‘Where are your sister and your dad, Abbie?’

No answer. She closed her eyes and flopped sideways towards me.

I caught sight of the dolls again.

It felt as if someone had lightly touched the back of my neck with a cold hand.

It was the eyes.

In some of the dolls, the whole eye was white – no iris or pupil. In others, the iris was high, so you just saw the edge of it as if the eyes had rolled up inside the doll’s head.

I turned away, feeling Abbie’s soft weight against me.

2. (#ulink_39264996-170b-593b-82d2-b1791b965a5e)

I skidded my car to a halt on an icy, stone-flagged courtyard in front of the pillared entrance of Bellhurst House. Back-up hadn’t yet arrived and the place was deserted. I’d left Abbie with a PC at Elaine’s, but my stomach was knotted with concern for her relatives. They could be lying inside, gasping for breath, blood pouring from their wounds. I jumped from the car.

The house was Victorian Gothic, in the style of a small lunatic asylum. The kind of place where you’d find inexplicable cold corners and notice the cats avoiding certain rooms. It had two spiky-roofed, bay-windowed halves, flanking a tower topped with a witches’ cap roof.

I bashed a brass lion-head knocker against the oak door. No answer, but when I shoved the door, it opened into a narrow hallway. A stained-glass window splashed colours onto the carpet. I stopped a moment and listened, aware that I shouldn’t go in alone.

I stepped into the hall. ‘Police! Is anyone there?’

Nothing. The house was so silent, it hurt my ears.

I checked downstairs. There was evidence of a break-in – a forced window and glass crunching underfoot in a utility room – but I didn’t stop to investigate.

The stairs were narrow and all slightly different heights, making it hard not to trip. They led onto a landing which smelt of library books and damp coins. I crossed the creaky-boarded floor and poked my head into the first bedroom. It must have been Abbie’s room, or possibly her sister’s – decorated in the pink and purple that some little girls seemed to insist on, to the horror of feminist mothers. I gave it a quick glance – no blood – and retreated onto the landing. Another door opened into a larger room.

I froze. A man lay sprawled on his back on a double bed. Blood had sprayed onto the white wall beside him – a jagged line of crimson blobs with tails trailing below. More blood smeared the white duvet, the sheets, and the cream carpet by the bed. It was fresh and vivid, its coppery smell filling my nostrils.

I rushed over and checked his pulse, but I knew he was dead. I felt a wave of despair for Abbie – so strong my knees went weak. Was this her father?

I could never get used to these moments. The visceral shock of someone being dead. The knowledge that his family would have to live forever with this. Abbie would always be the girl whose father was murdered. Possibly the girl who saw her father murdered. This would be with her for the rest of her life.

I took a moment to look at the man’s face. To think of him as a person, before he became a job, a problem to be solved, a puzzle to be pored over.

I let myself feel the sadness, then took a deep breath and forced myself into robotic mode.

I scanned the walls. The blood was arterial – you could see the tell-tale pattern produced by the pumping of his heart. I glanced at the man’s throat. The carotid had been slit. He lay on his white sheets surrounded by the spectacular crimson display, his head jerked back into the pillow.

I flicked my gaze around the room. A window was open. Drawers had been pulled out and upended, leaving T-shirts and underwear littering the floor. A photo by the bedside showed a couple grinning at the camera, blue sea behind them. It was this man. I pictured little Abbie, wrapped in fleeces, hugging the dog, blood smeared on her face. The room shifted as if I was on a boat. Had she seen this done to her father?

And where was the sister? And what about the mother?

I needed to get out. Get the scene secured. My mind was full of all the things I had to do – gripped by that familiar desperation to get this right. To get it right for the relatives. For little Abbie.

I carefully left the bedroom and checked the rest of the house, pushing each door with tight fingers, praying I wouldn’t find a dead sister or mother.

I didn’t. The house was empty. I called in what I’d found, spoke to the crime scene manager and media officer, and walked back out to my car.

I jumped. Tyres kicked up gravel. A silver four-wheel drive hurtled along the driveway and skidded sideways onto the paved area, almost hitting my car. A woman leapt out and ran towards me. She looked familiar. The woman from the photo by the bed, minus the sunniness. ‘What’s going on?’ she shouted. ‘Where’s Abbie? What have you done with her?’

I took a step towards her, trying to block her from going into the house. ‘Abbie’s fine. Wait a minute.’

She pushed past me.

I reached for her arm. ‘You can’t go – ’

She pulled away. ‘Where’s Abbie?’

‘Stop! You can’t go inside.’ I shot round her and blocked her path with my body. ‘Abbie’s fine. She’s not in there.’

She tried to shove past me, so hard I was forced to push her away. She caught her heel on a flagstone and fell backwards, landing with a thud. I reached down to her, but she jumped up without my help.

I saw her arm draw back and then my eye exploded. I collapsed onto the icy ground.

*

I opened my eyes. Wow, that hurt. Of course they all chose that moment to arrive. The pathologist, a herd of SOCOs, half of Derbyshire’s uniformed PCs, and DS Craig Cooper – the nastiest cop in town. I heaved myself up as quickly as possible and tried to look like someone who hadn’t been punched in the face.

Craig jumped out of his car. ‘Christ, what happened?’

I gestured into the house. ‘Victim’s wife’s in there. Get her out.’

I touched the skin above my cheekbone. There were types of people you expected to thump you, and she hadn’t been one of them. I’d allowed her through, and now she’d have messed up the scene.

I suited up in the shadow of the house. My ankle was throbbing. I’d injured it as a child and it hadn’t healed well. A big lump of callus stuck out and restricted movement, making me walk with a slight limp and minimising my chances of ever looking like a glamorous TV detective. I must have bashed it when I’d fallen.

Craig appeared, leading the wife by the arm. Her hair and clothes were smeared red, and she was hunched over, letting out gulping sobs. Craig gave a little shake of his head and rolled his eyes to the sky.

The woman pulled herself free of Craig and stood breathing heavily and seeming to get control of herself. She raised her head. ‘Where’s Abbie? Where’s my little girl?’

‘She’s with police at a neighbour’s. She’s fine.’

The woman sniffed loudly and took a couple more open-mouthed breaths. ‘I told the police someone was stalking us. I told you but nobody believed me. Oh God . . . ’ She folded forwards again and held her stomach.

‘We’ll need to ask you about that,’ I said gently, ignoring the implied criticism. ‘But I have to get a few things started. Then I’ll take you to Abbie.’

She leant against one of the pillars by the door.

‘Was anyone else in the house?’ I asked. ‘Abbie mentioned her sister.’

‘There’s no one else.’ The woman swallowed and seemed to shrink into herself. ‘Jess died. Years ago.’

I opened my mouth to say something, but nothing emerged. Craig took the woman’s arm and led her away.

I made sure inner and outer cordons were in place, and went back in for a careful look around.

The hallway led into a utility room that had an old-house smell of mould and mushrooms. Its window had been smashed, the catch released, and the sash shoved upwards, making a space big enough for someone to climb in. The house still had its original wooden windows, making it an easy target. One thing for hideous PVC double glazing – it did make breaking in a little harder, and prints showed up so much better on plastic than on wood.

The kitchen was terracotta-tiled and rustic, with a central butcher’s block fit for dismembering large animals. The room was tidy but lived in, the fridge adorned with magnetic letters and a rather competent drawing of a dog’s head. A calendar on the wall showed school trips and ballet lessons. I glanced at today’s date – Rachel back from Mum’s. They were so terribly sad, the calendars of dead people, full of assumptions of an ordinary life continued.

One of a collection of impressive chef’s knives was missing from a knife block on the countertop. If they were in order, it was the largest. I looked at the others – all throat-slittingly sharp.

There was no evidence of an intruder in the living room. The TV and a laptop were still there, and the normal clutter of a family. A sketch pad and pencils, a thriller involving submarines, a pile of tedious-looking paperwork, a pair of nasty trainers.

A small study next door had been substantially trashed. All the drawers in an antique-style desk had been emptied, leaving piles of papers strewn over the floor. I scanned the piles, not knowing what I was looking for, wondering what they’d been looking for. Trying to sense the murderer’s presence in the room amongst the mess they’d made.

I scrutinised the bookshelves. More man-thrillers, reference books, and a little cluster of self-help, including a book called You Become What You Believe, which seemed tragically ironic in the circumstances. A card was propped on a low shelf of a bookcase, a picture of a kitten on its front. I lifted it with a gloved hand and looked inside. Thank you for getting in touch. We appreciated it. We don’t know who you are and we can’t tell you who we are, but it is of comfort to us that something good has come out of this terrible tragedy. I stuck it in a bag.

I noticed a door in the corner. It was hard to picture the layout of this peculiar house. I walked over and pushed it, and found myself in a bright room with a bay window overlooking a garden. Green-tinted light flooded in. The walls were lined with benches, on which drawings lay scattered. I stepped over to look at them. A charcoal heart on cream paper, snakes’ heads projecting from it, the muscle of the heart melding seamlessly into the snakes’ necks, an optical illusion making the muscle seem to twitch. Another heart shown split in two, blood oozing from its red centre. A third with a single eye which stared out at me and seemed to follow me as I walked along by the bench. I felt goose pimples on my arms, and made a note to get the whole lot bagged up.

Upstairs, nothing was obviously wrong in the pink room. No blood that I could see. Just a normal kid’s room – another sketch book, pony pictures on the walls, a globe on a painted desk, a mauve duvet hanging over the side of the bed, a fluffy elephant on the floor. My eyes were drawn to a sparkling amethyst geode on the bedside table, its purple crystalline innards shining from inside a dark egg of stone. I’d loved crystals and minerals too when I was a child.

The air in the main bedroom had a metallic sweetness that touched the back of my throat. The pathologist had arrived. Mary Oliver. We’d bonded over a few corpses since I’d come to the Derbyshire force six months previously – we shared an interest in obscure medical conditions and a guilty Child Genius addiction.

A glimpse of bone shone through the dark slash in the man’s neck, reminding me of abattoir photographs from animal rights groups. ‘So, he was killed by cutting his throat?’ I said.

‘Almost certainly. The PM will confirm.’

‘Is the carotid severed?’

‘Yep, cut right through with an inward stabbing motion. Two stabs, by the look of it. That’s why we’ve got some nice spatter.’

‘Would someone need a knowledge of anatomy or would random stabbing do it?’

‘Random stabbing could do it, although you’d have to be lucky with the location of the knife.’ She paused and looked at me. ‘Or unlucky, depending on your point of view.’

‘Time of death?’

‘Can’t be accurate on that yet, as you know.’

‘But . . . ’

‘His underarms are cool. From his temperature and the lividity, I’d suggest somewhere between 2 a.m. and 5 a.m. He’s not been moved post mortem. This is all provisional, as you know.’

‘Okay. And he doesn’t seem to have struggled?’

‘I’d say he was fast asleep and he never regained consciousness. Unpleasant business.’

Something had to be pretty gruesome for Mary to say it was unpleasant. Her bar was high. ‘So, it’s a premeditated attack then? Is that what we’re saying?’

‘There are no defence injuries that I can see at the moment. It’s not your typical interrupted-burglar or domestic scenario. Shame the wife got in and messed up the scene though.’

‘I know.’ I reminded myself I’d done my best to stop her, at some personal cost. Guilt was my specialist subject, which I could perform to Olympic level. ‘The child had blood on her as well, so I suppose she must have come in and seen this.’ I imagined briefly how Abbie must have felt. I’d been about the same age when I’d found my sister hanging from her bedroom ceiling. I hoped Abbie wouldn’t still be having flashbacks in her mid-thirties. ‘She’s not saying much.’

Mary frowned at me. ‘Have you found a weapon?’

‘No. What are we looking for?’

‘An extremely sharp knife with a pointed end.’

‘Something was missing from a knife block in the kitchen.’

‘Could a woman have done it?’

I hadn’t heard Craig creeping up behind me. He was quiet, given what a lump he was. I stood back a little to let him see into the room.

‘What Craig wants to know,’ I said, ‘is whether someone with limited upper body strength could have done this.’

‘Don’t get all uppity,’ Craig said. ‘Women do have limited upper body strength.’

‘Assumptions like that get us into trouble,’ I said. ‘You need to arm-wrestle my friend Hannah. I suppose at least you’re not assuming a man did it.’

‘Au contraire,’ Craig said, having recently returned from some winter sun. ‘It’s probably the bloke’s wife.’

That probably said more about Craig’s relationship with his wife than it did about the murder, but I decided to keep that insight to myself.

‘You wouldn’t need a great amount of strength,’ Mary said. ‘Because it was done with an inward stabbing rather than a slicing motion. A feeble little woman could definitely have done it.’ She smiled at me to show her solidarity.

I nodded a thank you at Mary, and stood for a moment taking in the room. Something was odd. The chaos of pulled-out drawers and strewn clothes was muted. I couldn’t imagine an intruder storming through.

An en-suite bathroom led off the bedroom. From the droplets of water in the cubicle and on the floor, it looked as if someone had taken a shower within the previous few hours.

Back on the landing, I noticed something on the windowsill, almost hidden behind the curtain. At first I thought it was a vase, but then realised it was a carving in pale wood. I walked over and looked more closely. It was a miniature version of one of the stone statues I’d seen in the clearing – a child screaming. The terrible face was the same, making the hairs on my arms stand on end. But there was one difference. This one was naked, and where the heart should have been, the wood had been gouged out, leaving a hollow in the child’s chest.

3. (#ulink_22397284-85e3-58dc-95f8-9355a275e4e2)

Back outside, I found Craig standing on the paved area staring upwards. His breath puffed dragon-like into the air. ‘It looks like a house for freaks.’

Good old Craig. Always ready to empathise with the victim. But he did have a point. I loved these kinds of houses, but wasn’t sure I’d want to live in this one, even without a corpse in the bedroom. Not in the middle of the woods, isolated from any other human life. I looked up at the central tower poking into the heavy morning sky. ‘You can imagine catching sight of dead children’s faces in those top windows,’ I said, forgetting for a moment that it was Craig.

‘You’re not going to have one of your funny turns, are you?’

I pretended I hadn’t heard. He knew I’d had time off with stress in my last job in Manchester, a fact which I found excruciating. But I was senior to him. He wasn’t supposed to talk to me like that. I just wasn’t sure how to stop him without resorting to being a total dick. If I ever had to work closely with him, I’d be forced to take up Zen Buddhism or go to anger management classes. I sucked in a breath of bitterly cold, pine-saturated air and thought about fluffy kittens and not at all about smacking Craig’s smug face.

‘They brought the kid back,’ he said. ‘She’s in the van with her mum and the paramedics. Victim’s name’s Philip Thornton. His wife’s Rachel Thornton. Wife claims she was with her mother last night, left there at nine this morning to come here. Put petrol in the car in Matlock, and we’ve confirmed that with the petrol station. When did he die?’

‘Mary thinks between two and five.’

‘How come you were on the floor? Did you fall over?’

I didn’t answer. Decided not to mention the punch. It would give Craig far too much pleasure. ‘I think she’s the woman who’s been phoning about a stalker,’ I said.

Craig let out a sigh of theatrical weariness. ‘Bloody fantastic. So it’ll be our fault the poor bastard’s had his throat slit.’

*

I climbed into the paramedic’s van. Abbie looked tiny, sitting on a robust green chair, quietly rocking to and fro, her legs pulled to her chest. She was still holding on to my sister’s scarf. Her mother sat by her, but there was a space between them, a physical distance that seemed matched by something else – something about the way the woman didn’t quite look at her daughter, the way she angled herself away from her a tiny bit.

I couldn’t take on this case – I’d have to pass it on to another DI or DCI – but early information was vital, so I needed to talk to the wife. In the horror of the immediate aftermath, the relatives often handed you the answers, fresh and steaming on a plate.

The van smelt of bleach and misery. I had a flash of memory. When I’d found my sister, I’d curled up like Abbie was now, trying to make myself so small I’d disappear. I wanted to put my arms around Abbie and make it all go away. But of course nothing would make it go away.

‘Mrs Thornton,’ I said. ‘I’m sorry. You’ve had a terrible shock.’

She looked up and gave me a blank stare. ‘It’s Rachel.’ There was a deadness in her eyes as if they’d seen too much.

I sat on the seat next to her. All the earlier agitation seemed to have gone, and she looked flat and resigned.

‘I’m DI Meg Dalton,’ I said. ‘I need to ask you a few questions. I know it’s hard but the sooner we get onto it, the better.’

Rachel shifted away from me slightly, but still kept a little distance between herself and Abbie. ‘I told you someone was following me.’ She sniffed and wiped her face with a tissue.

Abbie leant her head against the side of the van, eyes closed, red-smeared blonde hair spilling over the back of her seat. I wanted to get her cleaned up and warmed up and generally looked after. But I’d been told that sensitive kid-people were on their way to handle this, and to make sure we didn’t lose any evidence in the process.

Rachel ran blood-stained fingers through her own dark hair. Mascara seemed to bruise her cheeks.

‘Can we talk outside?’ I said.

She nodded. We left Abbie in the van, being looked after by the paramedics, and walked along a path leading away from the house and into the woods.

The ground was so cold I could feel it through the thin soles of my trainers, and the air was icy and seemed more solid than usual. I remembered Abbie’s feet stepping through the freezing stream and hoped the paramedics had made sure she was okay.

‘So, tell me about this person who was following you.’

Rachel breathed in shakily, and swallowed. ‘No one took it seriously. I told your people but they didn’t care.’

‘Do you know who it was?’

We walked slowly, Rachel shuffling as if her feet were numb. ‘I never saw them properly. I only caught glimpses and sensed someone looking at me when I went outside or walked in the woods.’ She sniffed and wiped her face. ‘Once I even thought someone was following us when we went out in the car.’

‘Can you remember what type of car they were in?’

She shook her head. ‘Sorry.’

‘It’s okay. You’re doing really well.’

She ground to a standstill and looked down at her feet. ‘How am I supposed to cope? I don’t know how I’m supposed to get through this.’

There was no answer to that. A woman in her forties, with a young child, her husband gone. I didn’t know how she was supposed to cope.

‘There’s a bench,’ I said. ‘If you’re not too cold. Shall we sit a moment?’

‘I’m not cold. I don’t feel anything. I could walk into a frozen lake and I’d feel nothing.’

We walked to the bench, which was in the clearing with the statues I’d seen earlier.

‘Do the woods belong to you?’ I asked. ‘And the statues?’

She glanced at them and let out her breath. Nodded slowly. ‘Horrible things.’

‘Are they old?’

‘Victorian, I think.’

A plaque was attached to the nearest statue’s base. I leant forward to read it. For the weak and the poor who died for the strong and the rich. How depressing.

I glanced at Rachel. She was shaky but seemed to be coping. ‘Just a few more questions. Is that okay?’

‘I suppose so.’ She stared ahead, as still as one of the statues. ‘I don’t think it’s sunk in.’

‘Thank you. We can go back to Abbie in a moment. But do you remember when you first noticed you were being followed?’ I was careful not to say, When you thought you were being followed, or anything that implied she might have been mistaken.

‘A few months ago. I wondered if it was something to do with Phil’s job. He’s a social worker, and sometimes the parents of the kids can get nasty. But Phil didn’t think it was that.’

I twisted to sit sideways on the bench, so I could look at her. ‘Who did he think it was?’

She paused and her eyes went glassy. When she spoke, her throat sounded tight. ‘I don’t think he even believed me. He thought I was imagining it. Ironically.’ She twisted her mouth into an almost-smile, and fiddled with her wedding ring, rotating it on her finger. ‘But he’s been odd recently. He disappeared a few times and didn’t tell me where he was going. And he’s been a bit secretive.’ She sat up straighter, and some life came back into her, as if thinking about her husband’s strange behaviour was dulling her pain. She took a deep breath and turned to look at me. ‘I do love him though. I really love him.’

‘Okay,’ I said. ‘Thanks. And I need to know where you were this morning.’

She fished a tissue from her pocket and blew her nose loudly. ‘That other detective already asked me. I stayed at Mum’s. It had been arranged for ages. Phil and Abbie came home and I stayed on a couple more days to help Mum with sorting out some stuff. Wills and things.’

It was one of the most painful things about these investigations. This woman was sitting next to me on a freezing bench with her life splintering apart. Although I could only sense the jagged edges of it, I knew her pain. And yet a part of me was assessing her. Wondering if she could have done it. If she was the one who’d plunged that knife into her husband’s neck. ‘So, you were at your mother’s last night, but you came home this morning?’

‘Yes. When I’m away, Phil and I always talk in the morning. And he didn’t answer, and he wasn’t responding to texts. So, well, I wasn’t exactly panicking because he and Abbie are both on these sleeping pills and he can sleep late, but I had a bad feeling. So I came back. And then when I got back, I found you and . . . ’

I waited but she didn’t carry on.

‘Where does your mother live?’

‘A couple of miles past Matlock. Not far.’

‘And did you drive straight from your mother’s to your house this morning?’

She hesitated. ‘I got petrol in Matlock. You can check that.’

That suspicious part of me felt something. Something deep inside that my boss would dismiss as a hunch, but that I knew was based on years of experience and observation. Something my subconscious mind had translated into a twitching in my stomach. Her responses weren’t quite right.

‘So, when you saw me, had you come straight from your mother’s, apart from getting petrol?’

She touched her throat. ‘I told you that. It took a while though, with the traffic. Do you think Abbie was there when . . . She’s really sleepy. She doesn’t remember. She’s on these pills for her night terrors. But she must have . . . what? Seen the killer? Or wandered through to our room and found Phil . . . ’

‘How old’s Abbie?’

‘Ten. She’s small for her age.’

I waited a moment, feeling the cold air in my nostrils. The wind whispered through the trees, and I could hear the river in the distance. ‘What pills is she on?’

‘Sleeping pills. I can show you.’

A ten-year-old on pills. I knew in the US the drug companies had achieved the holy grail of pills for all – old or young, sick or well. But in this country, sleeping pills for a kid was unusual.

‘And . . . why did you realise something was badly wrong?’ I said. ‘When you saw my car, I mean. You seemed very upset and worried.’

Rachel turned her body away from me and spoke as if to someone sitting on her opposite side. ‘I just knew.’ She blew her nose again.

All the birdsong and rustling of the trees and the rushing river seemed far away. The woods were quiet around us, as if muted by the presence of the stone girls.

‘What’s the story behind the statues?’ I asked.

‘Oh, I don’t know. Some ancient folk tale or something. Phil was obsessed with them but he always denied it.’

‘I noticed a carving on your landing, similar to one of them.’

‘You see. Phil did that. I sometimes thought he only bought the house because of the statues. It’s such a money pit, I don’t know why else he came here. But he always clammed up if I asked him about them, apart from one time when he was drunk . . . ’

‘What did he say then?’

‘I couldn’t get much sense out of him. But something about doing penance, I think.’

My ears twitched. ‘Penance? What did he mean by that?’

‘He wouldn’t say. But it seemed to have something to do with these.’ She nodded towards the stone children.

Penance. That was a hot word. When anyone wanted to do penance, there was always a chance someone else wanted revenge. I wondered about the story behind the statues. ‘So, any more ideas why you were so worried when you arrived at the house this morning?’

She hesitated. ‘I don’t know. Because no one answered the phone earlier I suppose. I’m always worried about Abbie’s health. I’m sure he probably does know what he’s doing, but I always wonder if Phil gets her medication right when I’m not around.’

‘What medical problem does Abbie have?’

Rachel rubbed her nose. There was something sticky in the air between us. Something she wasn’t saying. She didn’t seem numb and shocked any more – there was a new sharpness about her. She huddled into her coat as if suddenly aware of the cold. ‘You never think about your heart, do you, until it goes wrong? And then you think about it all the time.’

‘Does Abbie have a heart problem?’

‘Yes. It’s in Phil’s family.’

‘So, did Abbie have a sister?’

‘Jess. She died four years ago. She was only six. Not of the heart problem though. An accident.’

‘I’m sorry. Were they twins?’

Rachel shook her head. ‘Abbie’s Phil’s daughter and Jess was mine. I adopted Abbie after Phil’s ex-wife died.’

I turned to Rachel and looked at her dead eyes; weighed up whether to say anything; decided I should. ‘I lost my older sister when I was ten. She was fifteen.’

Some of the tension left her body. Maybe I shouldn’t have mentioned my sister. It wasn’t exactly in the manual of recommended interviewing techniques. But Rachel Thornton was a person too, and I found if you shared with people, they often had a strong urge to share back. Sometimes they’d even share that they’d killed someone. Most murderers didn’t intend to kill – it was something that happened in a loose moment that slipped away from them, when they were so furious they weren’t really noticing what they were doing. Often it was a relief to explain and justify.

Besides, my story was public now. Google my name and there it was. Poor me. Found my sister hanging from a beam, and I was only ten. Everyone knew. After I’d kept it to myself all those years. I felt like someone who’d fallen asleep drunk and woken up with no clothes on.

We sat together on the freezing bench, touched by our own individual horrors.

I hoped she might say more but she didn’t, and I decided not to push it for now. We’d need to get her in for a formal statement anyway.

‘Is Abbie’s heart okay?’ I asked.

‘She had a transplant last year.’

‘That’s why you can’t let her have pets?’

‘That’s right. She has a suppressed immune system.’

I pictured the needle marks on Abbie’s arms. Remembered her hugging the dog, then wrapped in his blankets and Carrie’s scarf, after nearly freezing to death. Not ideal.

‘Is she okay though?’

‘Yes, of course.’

‘Was there a problem with the transplant? Is that what your husband’s artwork’s about?’

‘Of course not. This has nothing to do with Abbie’s heart.’

I turned to look at Rachel’s face.

‘Do you mean your husband’s death?’ I asked. ‘Why would it have anything to do with Abbie’s heart?’

She blinked a couple of times and shook her head. ‘It wouldn’t. I didn’t mean anything. Abbie’s heart’s fine.’

4. (#ulink_6b2ebd64-4b06-501f-822a-4b62a25e370c)

‘I can’t take on a big case,’ I said. ‘I spoke to the victim’s wife at the scene, but I’ll have to hand it over to someone else. It’s really bad timing for me.’

DS Jai Sanghera leant against the window in my room and hitched one leg up onto the sill in a bizarre yoga-style move. ‘Have you told Richard why you’re off next week?’

I took a step towards the door and lowered my voice. ‘He wants to see me now. I can’t tell him. I said I was spending time with family and catching up on some DIY and stuff.’

‘If you don’t take it on, he’ll ship someone else in. DI Dickhead from Nottingham.’

My stomach tightened at the thought of Abbie being grilled in one of our dispiriting interview rooms. ‘Maybe he’ll bring that woman in? She’s alright.’

Jai shook his head. ‘She’s tied up on a big case already. Human trafficking. No chance.’

I’d told Abbie I’d make sure she was okay. But I couldn’t let my family down. I swallowed. ‘I can’t delay my time off. You don’t know what it’s like.’

‘I know what it’s like to lose a grandparent. Tell him you can’t take the case. We’ll cope with Dickhead.’

*

It was only Monday afternoon, but I felt as if I’d had a full week at work. And I still hadn’t called Mum back. I shoved open the door to DCI Richard Atkins’ lair.

‘Ah, Meg.’ Richard’s customary greeting, whether he was bollocking or praising. ‘Sit down.’ He indicated his spare chair, famous for its ability to engulf the unwary. I suspected it housed the putrefied remains of previous DIs.

I stayed standing. ‘I can’t take on this case. I’ve got time off next week.’

Richard looked at me over piles of papers and the tiny cacti he used as paperweights. He rearranged them each morning and I was always looking for meaning in the arrangements, as if he was sending messages about his mood or the state of the world. He cracked his fingers. ‘You let the victim’s daughter fall into freezing water,’ he said. ‘You mustn’t be so careless. She could have been seriously hurt, and the evidence on her nightdress is compromised. What on earth were you thinking?’

‘It was an accident. She wanted to get the dog a drink, and – ’

‘The dog? You mustn’t let your love of animals affect your actions.’

I opened my mouth, so stunned by the unfairness of this that I didn’t know what to say.

Richard had put on weight, and was getting the look of a bulbous-nosed drinker. Did he know he was becoming a walking cliché? Eating unhealthily and turning to the bottle because his God-bothering wife had left him and was no longer providing healthy, vegetable-laden meals?

‘I’m very disappointed,’ Richard said. ‘And what’s this about the victim’s wife reporting a stalker and us ignoring it?’

‘We didn’t exactly ignore it, but she didn’t give us much to go on. And her phone calls stopped about six weeks ago. She hasn’t been in touch recently.’

‘It’s the last thing we need. Stalking’s hot at the moment. Pray to God it wasn’t the stalker that did for him.’

This was modern policing. It wasn’t so much the brutal throat-slitting that was tragic as the fact that we might get blamed. ‘If we’re asking any favours from deities,’ I said, ‘maybe pray we catch whoever did it and that no one else gets hurt.’

‘Yes, yes, of course. But the press’ll act like we went in with a lynch mob of Derbyshire detectives and cut his damn throat ourselves.’ Richard rubbed the slack skin on his neck. ‘And you shouldn’t have gone in without back-up.’

‘I know, but – ’

‘You could have been killed.’

‘I had to check – ’

‘You need to stick to procedure, Meg. No more doing your own thing. Especially when we’re already on the back foot with this bloody stalker fiasco.’

‘But someone could have been bleeding to – ’

‘There’s no excuse for putting yourself at risk.’

Christ, was he ever going to let me finish a sentence? I’d noticed that more senior people just talked over him, so they both ended up banging on at the same time, gradually increasing the volume until one of them gave up. I didn’t have the energy.

‘And I know your last murder case ended in a relatively good outcome. But, as we’ve discussed, you can’t behave like that again. What if you’d been seriously injured? Or killed?’

‘I know. It would have looked bad, wouldn’t it? But I was suspended, so it wouldn’t have been your fault if I’d drowned in a cave or plunged to my death in an old windmill.’

‘I’m not sure that’s how the press would have seen it.’

‘Good to know it’s my welfare you’re concerned about.’

Had he even heard me say I couldn’t take on this case?

‘You have to stick to the rules,’ Richard said. ‘Follow the evidence. This new case is a good opportunity. Show you can be a team player and do things properly.’

Clearly not.

‘I’m off from next Wednesday,’ I said. ‘It’s best I don’t take on this one.’

‘You’re not going away, are you? So you can delay your holiday if necessary.’

‘I don’t think I can do that.’

Richard narrowed his eyes. He knew how important work was to me, almost to the point of it being pathological. Why in God’s name had I not planned a convincing lie about a trip to Africa to save sick lions, or treatment for an obscure and terrifying gynaecological condition? I could feel my pulse quickening at the possibility that he’d work it out.

‘I’m trying to be fair here, Meg, but I’m a little confused. We could get Dickinson over from Nottingham, but I’m not sure about your level of commitment to the job if – ’

‘I’ll do it,’ I blurted. ‘I’ll delay my time off if necessary.’

‘Good. And I’d like you to work with Craig.’

‘Craig?’ I said weakly. ‘But . . . ’ I stopped. There was nothing I could say.

‘I’m not telling you you’ve only got six months to live, Meg. I’m asking you to work with a perfectly competent sergeant.’

‘Actually, Richard – ’

‘Right. Let’s do the briefing.’

*

The incident room felt hot and muggy, like somewhere you could catch malaria, despite the fact it looked ready to snow outside. A trace of ill-person’s sweat hung in the air, and cops coughed aggressively over one other. But the excitement of dealing with a murder fizzed through the air alongside the winter bugs. I shoved aside my worries about time off and family, and allowed myself to be swept along.

‘Are they Jackson Pollocks?’ Jai nodded towards a collection of blood-spatter photographs.

I frowned, pretending to disapprove of him.

Richard strode in, took off his jacket, and chucked it at a chair. It missed and fell on the floor. I nearly reached down for it, but realised there were precisely three men nearer to it than me. Why should I dash to pick the damn thing up? Especially given the way he’d just spoken to me. I noticed DC Fiona Redfern twitching too. But neither of us moved.

Jai retrieved the jacket.

‘Thank you, Jai.’ Richard shifted aside to let me into the hot spot. ‘It’s a long way down for me these days.’

I took a deep breath of the dubious air and stepped forward. ‘Right. The victim is Philip Thornton. Forty-eight-year-old male. Stabbed in the early hours. He was in the house with his ten-year-old daughter. Wife was apparently at her mother’s.’

Jai yawned inappropriately.

‘Am I boring you?’ I said.

Craig leered. ‘He’s been up late with his new girlfriend.’

I didn’t know Jai had a girlfriend. I looked at his open face. Would he not have told me? They were all staring at me. I realised I should say something corpse-related. I spoke too loudly. ‘The victim’s carotid artery was cut with a very sharp knife. As far as we can tell, he was asleep and didn’t put up any fight.’

‘So, whoever did it went in with the intention of killing him?’ Jai said.

‘Looks like it. There was evidence of an intruder in the house.’ I pictured the upturned drawers in the study and bedroom – remembered my feeling that something wasn’t quite right. ‘Possibly.’

‘We got into his phone. Very interesting.’ Our allocated digital media person, Emily, was the antithesis of every stereotype about sad geeks. As well as obviously being female, she glistened with Hollywood shine – all advert-white teeth and smooth-skinned perfection. Every time I saw her, I did a double-take, especially when she was surrounded by her dowdy colleagues, like a dahlia amongst dandelions.

‘Go on, Emily,’ I said.

‘There were missed phone calls and texts between 4.15 a.m. and 4.30 a.m. from a contact called Work. A mobile phone which we’re tracing.’

Emily clicked something and a list appeared on a screen behind us.

Call History:

4.15 a.m. – Work.

4.16 a.m. – Work

4.18 a.m. – Work

4.20 a.m. – Text from ‘Work’: ‘Phil, I need to talk.’

4.22 a.m. – Text from ‘Work’: ‘Why are you ignoring me? I know Rachel is away. I have to talk to you.’

4.30 a.m. – Work

4.33 a.m. – Work

4.40 a.m. – Work

‘Did he reply to any of this?’ I asked.

‘Nope. Not at all,’ Emily said. ‘I’ll leave you to it. I’m off to find out who Work really is.’ She walked off, leaving the room feeling drab in her absence.

I turned away from the screen. ‘The victim’s wife thought he’d been secretive recently. Which obviously ties in with the calls and texts. And the woman who reported the child in the woods said she saw a car driving up the lane to the house. In the night. The lane doesn’t go anywhere else. It’s possible this Work person could have gone to try and meet Phil.’

‘It fits the provisional time of death,’ Jai said.

The energy in the room bubbled up at the prospect of a good early lead. ‘The wife’s also been in touch previously about a stalker,’ I said. ‘And unfortunately – ’

‘We in our wisdom ignored her.’

Richard was starting to piss me off. He was obviously riled about me having the audacity to want time off.

I folded my arms and pivoted away from Richard. ‘We need to look at the details, obviously. But we didn’t have a lot to go on.’

‘We’ll get the blame for this,’ Craig said. ‘We need to cover our arses.’

‘Mainly we need to find whoever killed him,’ I said.

Richard coughed. ‘Quite so, Meg. And also cover our arses.’

I glanced at the texts shining guiltily from the screen. ‘If it was someone he was having an affair with, they could have faked the intruder. There was something not quite right about that. And we should look at the woman who found the girl in the woods. It’s a bit convenient that she saw the car in the middle of the night. And she seemed to know who the girl was. Plus, I had a feeling she might have known the victim too.’

They all nodded sagely except Richard, who scowled at me. ‘A feeling,’ he said. ‘You need more than that.’

I ignored him and carried on. ‘And, oh I don’t know, it’s probably not relevant, but . . . ’ As soon as that came out of my mouth, I knew it wasn’t confident enough. Not Alpha enough.

Richard jumped on me. ‘Why are you telling us then?’

I felt sweat prickling under my armpits. Maybe it wasn’t just about Richard’s wife leaving. Maybe he was going through the male menopause. I’d read somewhere that men’s moods were more cyclic than women’s, contrary to received (male) wisdom.

I raised my voice. ‘Okay, I think it might be relevant. There was something strange going on in that family.’

‘Other than the bloke having his carotid slashed?’ Richard said. ‘What do you mean by that?’

‘His artwork. Her reaction to it.’

Jai gave me a puzzled look. Craig rolled his eyes and said, ‘We’ve got an absolute corker of a lead with those phone calls and texts and – ’

‘I saw the photos of that artwork,’ Fiona said. ‘It’s creepy. Hearts doing weird things. Do you think he was on drugs when he did it? It’s not normal.’

Craig wouldn’t like being interrupted by Fiona. He was tapping his fingers on his knee – that meant he was about to get snide or aggressive. He’d have a dig now.

‘Poor bastard’s had his throat slit,’ he said. ‘And you ladies are all over the fact he did a bit of screwed-up art in his spare time.’ There it was.

I pretended Craig didn’t exist. I even managed to do something weird with the focus of my eyes, so I was staring directly through him at the coughing IT guy behind. ‘The victim’s daughter had a heart transplant last summer. There was a card I think might have been from the family of the donor. But the art suggests all’s not well. And the way the wife talked – it made me think there was something wrong.’

‘When you hear hoofbeats,’ Richard said. ‘Think horses, not zebras.’

‘Huh?’ Jai said.

‘Look at the most likely explanations,’ Richard said. ‘It’s not hard to understand.’

‘It could have been the wife. If she found out her husband was having an affair.’ Fiona was clearly not interested in the zebras, and was of the opinion that an affair was good grounds for throat-slitting.

‘And she was desperate to get back inside the house,’ I said. ‘I think she may have messed up the scene deliberately. And someone had been in the shower.’

‘But her story adds up,’ Craig said. ‘She was at a petrol station in Matlock at nine in the morning.’

‘She could have come to the house earlier and then gone back to Matlock. We need to check. There are no immediate neighbours, and there are ways to the house that avoid CCTV altogether, but we can look at the camera on the main road.’ I raised an eyebrow at Richard. ‘And the spouse is always a horse, don’t you agree?’

‘Didn’t the little girl see anything?’ Fiona asked.

‘She was on sleeping pills for night terrors she’s been having. We haven’t been able to get much sense out of her. It looks like she must have woken up, wandered through to her parents’ room, found her father, tried to wake him and got blood all over her, and then run out into the woods.’

‘How horrendous,’ Fiona said.

‘She’s a lovely kid too.’ I felt that weight again. The responsibility to solve this, for Abbie. ‘You know this area well, don’t you, Fiona?’

Craig butted in. ‘Her gran does. She’s on our Blue Rinse Task Force.’

I smiled at Fiona. ‘Do you know about a folk story associated with that house? There are some statues of children in the woods.’

‘Really, Meg.’ Richard wafted his arm as if he was standing over a decomposing rat. ‘What does this have to do with the investigation?’

‘His wife said the victim was obsessed with the statues, and something about wanting to do penance. It might be relevant. He’d replicated one of them out of wood, except with its heart ripped out.’

The door bashed open and Emily walked in and stood as if under stage lighting. ‘Got the trace on that mobile phone,’ she said. ‘It’s a colleague of Phil Thornton’s. Karen Jenkins.’

5. (#ulink_f85a1f85-6659-560e-9ab4-d8b2efccf4dd)

Karen Jenkins shuffled into the interview room, bashed her leg on the drab grey desk, and apologised to it. I smiled. It was the sort of depressingly British thing I’d do.

Craig sorted out the recording apparatus and took her through the formal bits and pieces. Jai was watching from an observation room. It was still only the afternoon of the first day and we had a solid lead. I prayed we could get this one cleared up fast so I could avoid my lie to Richard being exposed. There was no way I could delay my time off, whatever I’d said to him.

Karen was in her mid to late forties, and reminded me of one of those hairy dogs whose eyes you never see. She cleared her throat a couple of times and licked her lips. Glanced at me and quickly looked away. ‘Sorry. I’m not used to being questioned by the police.’ She gave a high-pitched laugh. ‘Can I make notes in my pad? It calms me.’

‘Yes, of course.’ I leaned back in my deeply uncomfortable chair.

She shook her head so her hair covered her eyes almost completely. ‘Right. Yes. No. I can’t believe it. Can’t believe it happened.’ She picked up her pen and tapped it against her pad, but didn’t write anything.

I chatted nonsense for a while to relax her and calibrate – noticing what she did with her hands and face when she was talking about the weather and the traffic.

Once I’d got the feel of her, I asked casually, ‘Were you close to Phil Thornton?’

She swallowed and looked down, much stiller than before. ‘We were colleagues. Not close as such.’

‘His wife was concerned someone might have been following him. Do you know anything about that?’

She hesitated. I could see her breathing. Raised voices drifted in from in a nearby room. ‘No. Sorry,’ she said.

‘Anything worrying him that you were aware of?’

‘Nothing that would get him killed,’ she said, more abruptly. ‘He was worried about Abbie. And about his wife, I think. She’s a bit odd.’ She made a few swoopy doodles on her pad.

There was a smell in the air, familiar but wrong in this context. I looked up sharply and scrutinised her. Had she been drinking?

‘When was the last time you went to Phil’s house?’

Her eyes widened a fraction. ‘I don’t know. Ages ago.’

‘What was the occasion?’

‘You should be looking at his wife, not me,’ Karen said. ‘He was worried about his wife.’

‘The occasion you went to his house?’

‘They had me and my husband round. I can check the dates and get back to you.’

I glanced at the wedding ring on her hand. ‘Look, you need to be totally honest with me. Nobody’s judging you. But what kind of relationship did you have with Phil?’

‘We were close. Nothing ever happened.’ Jagged lines on the pad, deeper now, solid fingers gripping the pen, her body tense and so different to when she’d been chatting earlier.

‘Karen, I don’t care if you were having an affair, but you need to tell me the truth.’

Her voice shook, as if she was about to cry. ‘We were friends.’

I waited a moment, but she said no more.

‘Have you ever watched those TV murder mysteries where the victim’s friend is always forging Dutch masters or stealing prize orchids or something like that?’ I asked. ‘So they lie to the police, and you’re screaming at the telly saying, “Just tell them about the sodding orchids” because it never turns out well. Have you watched any of those?’

She nodded and licked her lips again, looking on the verge of tears, the skin beneath her eyes beginning to puff up.

‘Where were you on Sunday night?’ I asked.

‘Me? I was at home. You don’t think I did it? I would never . . . ’ She was crying now, gulping and wiping her hand over her nose.

Craig dived in. ‘You see, we have these texts and phone calls on Phil’s phone.’

Karen jumped and looked at him, as if she’d forgotten he was there. ‘I don’t know what you’re talking about. You think I . . . Oh my God.’

‘You went there, didn’t you,’ Craig said. ‘To his house.’

Karen flipped her gaze from me to Craig, and to me again, and shoved herself back in her chair as if wanting to put distance between us. She moved her foot in anxious circles over the dismal grey carpet.

‘You’ve nothing to worry about if you tell us the truth,’ I said. Which wasn’t strictly true.

‘No. I wasn’t there. I phoned him, that’s all. You need to look at Rachel.’ She hunched over her notepad and drew more swoops, then dropped her pen onto the desk. ‘She’s had mental health problems. Who knows what she’d do?’

‘What problems has she had?’ I settled in my chair, as if there was all the time in the world.

‘She had a psychotic episode. She could be dangerous.’

‘What exactly happened?’

‘You know Jess died? Rachel’s daughter?’

‘Yes. Four years ago.’

‘Well, that was . . . ’ Karen picked her pen up again and fiddled with the end of it. ‘Anyway, Rachel had a psychotic episode afterwards.’

‘What were you going to say about Jess? You cut yourself short.’

She shook her head. ‘No, I didn’t. I don’t know the full details.’

‘Of how Jess died, you mean?’

‘Yes. Phil didn’t like to talk about it.’

‘Just tell me what you know.’

Karen wriggled in her seat. ‘She fell out of a window. In that weird house. Not long after Rachel and Jess moved in.’

‘From a window?’ I was momentarily pitched off course. Why had I thought about dead children at the top window? Maybe I’d seen a news report and then forgotten it.

‘The attic window. The girls weren’t supposed to go up there.’ Karen grabbed her pen and doodled again. Jagged lines this time, like the start of a migraine. There was something she didn’t want to say. Something around Jess’s death. ‘It’s a weird house. Out in the middle of the woods. I remember when he bought it. He got obsessed with it. Had to have it.’

‘Did you know why?’

She relaxed a little with that question. ‘It seemed to be something to do with those weird statues in the woods. He was into art so maybe he liked the idea of owning them. I mean, I suppose they are cool in a creepy sort of way. But he was in a strange state at that time – I think he was in shock about his ex-wife dying.’

‘His ex-wife as in Abbie’s mother?’

‘Yes. She died not long after they separated.’

‘How did she die?’

‘Laura? In a car crash.’

I pondered the statistically improbable amount of death in this family, and made a note to do a check on the car crash, as well as the daughter’s death.

‘Rachel got really overprotective about Abbie,’ Karen said. ‘She adores Abbie, Phil said. As much as if she was her own daughter. And she kept thinking Abbie was ill all the time, even when she wasn’t, because she’d been diagnosed with Phil’s heart condition.’

‘Phil and Abbie had the same condition?’

‘Yes. Phil had a heart transplant a few years ago. I think he had to go abroad for it, actually, to China or somewhere. He’s fine now, but he has to take medication for the rest of his life. So of course they knew all the issues about waiting lists and how Abbie could die before a suitable heart came up. She got the symptoms younger, obviously. Phil was lucky in a way that it didn’t come on till later in life.’

‘Okay,’ I said. ‘So, Rachel didn’t cope very well with Abbie’s condition?’

‘No, I suppose having already lost a child . . . ’

‘I don’t see the relevance of this,’ Craig said.

Karen reddened. ‘I just thought I should tell you Rachel has some strange beliefs. She could be going psychotic again.’

I gave Craig a Shut up look. At this stage anything could be relevant and I didn’t want to close Karen down. There’d be time to push her later if we got more evidence against her. ‘What beliefs does she have?’

‘It was because Abbie was having night terrors. She was screaming that her dad was trying to kill her or something.’

I glanced at Craig. He was very still, staring at Karen.

‘Did you say Abbie was dreaming that her father was trying to kill her?’ I said.

‘That’s what Phil told me. He was really upset about it. Obviously. He would never lay a finger on Abbie, so it was awful.’

‘It must have been. And he shared all this with you?’

Karen reddened. ‘Only because it was so weird and upsetting. Rachel thought some bizarre stuff about Abbie.’

‘What did she think?’

This seemed to be getting us off track and was probably a distraction, but I thought we might as well hear her out.

Karen pushed her hair off her face. ‘Rachel got it into her head that Abbie was remembering what had happened to her heart donor.’

I looked up sharply from my notes. ‘What do you mean?’

Craig stopped fiddling with his pen.

‘She thought Abbie was having nightmares because she remembered what had happened to the girl she got her heart from. Rachel had this theory that the donor child had been abused or even killed by her father.’

Nobody said anything for a moment. The room seemed to shrink a little. ‘Rachel Thornton thought that was why Abbie was having nightmares?’ I said. ‘Because of her new heart?’

‘Yes. She thought Abbie’s dreams were from the donor child’s memories. From her death, in fact. That’s why she thought Abbie was scared of Phil. She thought Abbie was confusing him in her sleep with the donor child’s father.’

This was one of the stranger things I’d heard.

‘Thank you,’ I said. ‘You’re right to tell us anything you think could possibly be relevant.’

‘I think you’re trying to distract us,’ Craig said. ‘There’s no way a kid could remember something that happened to a different child.’

‘I didn’t say Abbie remembered,’ Karen said. ‘I said that was what Rachel thought.’

‘Thank you, Karen,’ I said. ‘It could be relevant, so thank you for telling us.’

She smiled and said almost under her breath, ‘I just thought it was weird.’

I left it a moment and then said, ‘We still need to know if you were having a relationship with Phil.’

She shook her head. ‘My husband mustn’t know . . . ’

‘There’s no reason your husband need find out.’

‘The children. He’d . . . He mustn’t know.’ She put the pen down. Her hand was shaking.