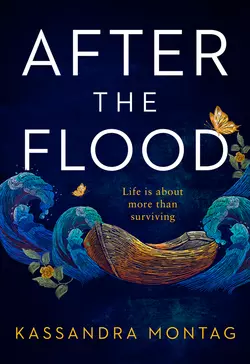

After the Flood

Kassandra montag

An unforgettable, inventive, and riveting epic saga with the literary force and evocative imagination of Station Eleven, Zone One, and The Road, that signals the arrival of an extraordinary new talent.After years of slowly overtaking the continent, starting with the great coastal cities, rising floodwaters have left America an archipelago of mountaintop colonies surrounded by a deep expanse of open water. Civilization as it once was is gone. Bands of pirates roam the waters, in search of goods and women to breed. Some join together to create a new kind of society, while others sail alone, barely surviving.Myra and her precocious and feisty eight-year-old daughter, Pearl, fish from their small boat, the Bird, visiting small hamlets and towns on dry land only to trade for supplies and information. Just before Pearl’s birth, when the monstrous deluge overtook their home in Nebraska, Maya’s oldest daughter, Row, was stolen by her father.For eight years Myra has searched for the girl that she knows, in her bones and her heart, still lives. In a violent confrontation with a stranger, Myra discovers that Row was last seen in a far-off encampment of raiders on the coast of what used to be Greenland. Throwing aside her usual caution, she and Pearl embark on a perilous voyage into the icy northern seas to rescue the girl, now thirteen.On the journey, Myra and Pearl join forces with a larger ship, a band of Americans like them. In a desperate act of deceit and manipulation, Myra convinces the crew to sail north. Though she hides her true motivations, Myra finds herself bonding with her fellow seekers, men, women, and children who hope to build a safe haven together in this dangerous new world.But secrets, lust, and betrayals threaten to capsize their dream, and after their fortunes take a shocking – and blood – turn, Myra can no longer ignore the question of whether saving Row is worth endangering Pearl and her fellow travelers.A compulsively readable novel of dark despair and soaring hope, After the Flood is a magnificent, action-packed, and sometimes frightening odyssey laced with wonder – an affecting and wholly original saga both redemptive and astonishing.

Copyright (#u4cdbe80a-f0ef-54df-82c3-c18f582b06b7)

The Borough Press

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

First published in Great Britain by HarperCollinsPublishers 2019

Copyright © Kassandra Montag 2019

Cover illustration © Shutterstock.com (http://Shutterstock.com)

Cover design by Ellie Game © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2019

Kassandra Montag asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008319557

Ebook Edition © SEPTEMBER 2019 ISBN: 9780008319571

Version: 2019-06-07

Dedication (#u4cdbe80a-f0ef-54df-82c3-c18f582b06b7)

For Andrew

Epigraph (#u4cdbe80a-f0ef-54df-82c3-c18f582b06b7)

Only what is entirely lost demands to be endlessly named: there is a mania to call the lost thing until it returns.

—Günter Grass

Contents

Cover (#u3ad65ae5-d3f6-54c4-b53c-6b49498e1ed0)

Title Page (#udbd1386c-3e36-55fc-a952-2f51fa1408f1)

Copyright

Dedication

Epigraph

Map

Prologue

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Chapter 31

Chapter 32

Chapter 33

Chapter 34

Chapter 35

Chapter 36

Chapter 37

Chapter 38

Chapter 39

Chapter 40

Chapter 41

Chapter 42

Chapter 43

Chapter 44

Chapter 45

Chapter 46

Chapter 47

Chapter 48

Chapter 49

Chapter 50

Chapter 51

Chapter 52

Chapter 53

Chapter 54

Chapter 55

Chapter 56

Chapter 57

Chapter 58

Acknowledgments

About the Author

About the Publisher

Map (#u4cdbe80a-f0ef-54df-82c3-c18f582b06b7)

PROLOGUE (#u4cdbe80a-f0ef-54df-82c3-c18f582b06b7)

CHILDREN THINK WE make them, but we don’t. They exist somewhere else, before us, before time. They come into the world and make us. They make us by breaking us first.

This was what I learned the day everything changed. I stood upstairs folding laundry, my back aching from Pearl’s weight. I held Pearl inside my body, the way a great whale swallows a man into the safety of his belly, waiting to spit him out. She rolled over in ways a fish never would; breathed through my blood, burrowed against bone.

The floodwater around our house stood five feet high, covering roads and lawns, fences and mailboxes. Nebraska had flooded only days before, water coming across the prairie in a single wave, returning the state to the inland sea it once was, the world now an archipelago of mountains and an expanse of water. Moments earlier, when I’d leaned out the open window, my reflection in the floodwater had returned dirty and marred, like I’d been stretched and then ripped into indiscriminate shreds.

I folded a shirt and screams startled me wide eyed. The voice was a blade, slipping metal between my joints. Row, my five-year-old daughter, must have known what was going on because she screamed, “No, no, no! Not without Mommy!”

I dropped the laundry and ran to the window. A small motorboat idled in the water outside our house. My husband, Jacob, swam to the boat, one arm paddling, the other clamping Row against his side as she struggled against him. He tried to hoist her onto the boat, but she elbowed him in the face. A man stood in the boat, leaning over the gunwale to pick her up. Row wore a too-small plaid jacket and jeans. Her pendant necklace swung like a pendulum across her chest as she struggled against Jacob. She thrashed and twisted like a caught fish, sending a spray of water into his face.

I opened the window and yelled, “Jacob, what are you doing?!”

He wouldn’t look at me or respond. Row saw me in the window and screamed for me, her feet kicking at the man who held her under the armpits, lifting her over the side of the boat.

I pounded the wall next to the window and yelled out to them again. Jacob pulled himself over the side of the boat as the man held Row. The panic in my fingertips turned to a buzzing fire. My body shook as I folded myself through the window and leapt into the water below.

My feet hit the ground beneath the water and I rolled to the side, trying to lighten my impact. When I surfaced, I saw Jacob had winced; the pained, tightened expression still on his face. He was now holding Row, who kicked and screamed, “Mommy! Mommy!”

I swam toward the boat, pushing aside debris that littered the water’s surface. A tin can, an old newspaper, a dead cat. The engine roared to life and the boat spun around, spraying me in the face with a wave of water. Jacob held Row back as she reached for me, her tiny arm taut, her fingers scratching the air.

I kept paddling as Row receded into the distance. I could hear her screams even after I could no longer see her small face, her mouth a dark circle, her hair standing on end, blowing in the wind that came off the water.

CHAPTER 1 (#u4cdbe80a-f0ef-54df-82c3-c18f582b06b7)

Seven Years Later

SEAGULLS CIRCLED OVER our boat, which made me think of Row. The way she squawked and waved her arms when she was first trying to walk; the way she stood completely still for almost an hour, watching the sandhill cranes, when I took her to the Platte to see their migration. She always seemed birdlike herself, with her thin bones and nervous, observant eyes, always scanning the horizon, ready to burst into flight.

Our boat was anchored off a rocky coast of what used to be British Columbia, just outside a small cove up ahead, where water filled a small basin between two mountaintops. We still called oceans by their former names, but it was really one giant ocean now, littered with pieces of land like crumbs fallen from the sky.

Dawn had just lightened the horizon and Pearl folded the bedding under the deck cover. She had been born there seven years earlier, during a storm with flashes of lightning white as pain.

I dropped bait in the crab pots and Pearl came out from under the deck cover, a headless snake in one hand, her knife in the other. Several snakes were woven around her wrists like bracelets.

“We’ll need to eat that tonight,” I said.

She sent me a sharp glance. Pearl looked nothing like her sister had, not thin boned or dark haired. Row had taken after me with her dark hair and gray eyes, but Pearl resembled her father with her curly auburn hair and the freckles across her nose. Sometimes I thought she even stood the way he did, solidly and sturdily, both feet planted on the ground, chin up slightly, hair always messed, arms a little back, chest up, as though exposing herself to the world with no fear or apprehension.

I had searched for Row and Jacob for six years. After they were gone, Grandfather and I took to the water on Bird, the boat he’d built, and Pearl was born soon after. Without Grandfather with me that first year, Pearl and I never would have made it. He fished while I fed Pearl, gathered information from everyone we passed, and taught me to sail.

His mother had built kayaks like her ancestors, and he remembered watching her shape the wood like a rib cage, holding people the way a mother held a child within her, sheltering them to shore. His father was a fisher, so Grandfather had spent his childhood on the Alaskan coastal seas. During the Hundred Year Flood, Grandfather had migrated inland with thousands of others, finally settling in Nebraska, where he worked as a carpenter for years. But he always missed the sea.

Grandfather searched for Jacob and Row when I didn’t have the heart to. Some days, I followed languidly behind him, tending to Pearl. At each village, he’d check the boats in the harbor for any sign of them. He’d show photographs of them at every saloon and trading post. On the open sea he’d ask every fisher we passed if they’d seen Row and Jacob.

But Grandfather had died when Pearl was still a baby, and suddenly the enormous task swelled up before me. Desperation clung to me like a second skin. In those early days, I would strap Pearl to my chest with an old scarf, wrapping her snugly against me. And I’d follow the same route he had taken: scouting the harbor, asking the locals, showing photographs to people. For a while it gave me vigor; something to do beyond survival, something that meant more to me than reeling in another fish to our small boat. Something that gave me hope and promised wholeness.

A year ago, Pearl and I had landed in a small village tucked in the northern Rockies. The storefronts were broken down, the roads dusty and littered with trash. It was one of the more crowded villages I’d been to. People hurried up and down the main road, which was filled with stalls and merchants. We passed one stall heavy-laden with scavenged goods that had been carried up the mountain before the flood. Milk cartons filled with gasoline and kerosene, jewelry to be melted and made into something else, a wheelbarrow, canned food, fishing poles, and bins of clothing.

The stall next to it sold items that had been made or found after the flood: plants and seeds, clay pots, candles, a wood bucket, bottles of alcohol from the local distillery, knives made by a blacksmith. They also sold packets of herbs with sprawling advertisements: WHITE WILLOW BARK FOR FEVER! ALOE VERA FOR BURNS!

Some goods had the corroded appearance of having been underwater. Merchants paid people to dive into old houses for items that hadn’t yet been scavenged before the floods and hadn’t rotted since. A screwdriver with a glaze of rust, a pillow stained yellow and heavy with mold.

The stall across from these held only small bottles of expired medications and boxes of ammunition. A woman with a machine gun guarded each side of the stall.

I had packed all the fish I’d caught in a satchel slung over my shoulder, and I hung on to the strap as we walked up the main road toward the trading post. I held Pearl’s hand with my other hand. Her red hair was so dry it was beginning to break off at the scalp. And her skin was scaly and light brown, not from sun, but from the early stages of scurvy. I needed to trade for fruit for her and better fishing supplies for me.

At the trading post I emptied my fish on the counter and the shopkeeper and I bartered. The shopkeeper was a stout woman with black hair and no bottom teeth. We went back and forth, settling on my seven fish for an orange, thread, fishing wire, and flatbread. After I packed my goods in my bag I laid out the photos of Row before the shopkeeper, asking if she’d seen her.

The woman paused, staring at the photo. Then she slowly shook her head.

“Are you sure?” I asked, convinced her pause meant she’d seen Row.

“No girl looks like this here,” the woman announced in a thick accent, and turned back to packaging my fish.

Pearl and I made our way down the main road toward the harbor. I’d check the ships, I told myself. This village was so crowded, Row could be here and the shopkeeper could have never seen her. Pearl and I walked hand in hand, pulling away from the merchants as they reached out to us from their stalls, their voices trailing behind us, “Fresh lemons! Chicken eggs! Plywood half off!”

Up ahead of me, I saw a girl with long dark hair, wearing a blue dress.

I stopped in my tracks and stared. The blue dress was Row’s: it had the same paisley pattern, a ruffle at the hem, and bell sleeves. The world flattened, the air gone suddenly thin. A man at my elbow was nagging me to buy his bread, but his voice came as though from a distance. A giddy lightness filled me as I watched the girl.

I rushed toward her, running down the path, knocking over a cart of fruit, pulling Pearl behind me. The ocean at the bottom of the harbor looked crystal blue, suddenly clean-looking and fresh.

I grabbed the girl’s shoulder and spun her around. “Row!” I said, ready to see her face again and pull her into my arms.

A different face glared at me.

“Don’t touch me,” the girl muttered, jerking her shoulder from my grasp.

“I’m so sorry,” I said, stepping back.

The girl scurried away from me, glancing over her shoulder at me anxiously.

I stood in the bustling road, dust swirling around me. Pearl turned her head toward my hip and coughed.

It’s someone else, I told myself, trying to adjust to this new reality. Disappointment crowded me but I pushed it back. You’ll still find her. It’s okay, you’ll find her, I chanted to myself.

Someone shoved me hard, ripping my satchel from my shoulder. Pearl fell to the ground and I stumbled to the side, catching myself against a stall with scavenged tires.

“Hey!” I yelled at the woman, now darting down the main road and behind a booth with bolts of fabric. I ran after her, leaping over a small cart filled with baby chicks, dodging an elderly man with a cane.

I ran and spun in circles, looking for the woman. People moved past me as though nothing had happened, the swirl of bodies and voices making me nauseous. I kept looking for what felt like ages, the sunlight dimming around me, casting long shadows on the ground. I ran and spun until I nearly collapsed, stopping close to where it had happened. I looked up the road at Pearl, who stood where she’d fallen, next to the stall with tires.

She didn’t see me between the people and stalls, and her eyes moved anxiously over the crowd, her chin quivering, holding her arm like it’d been hurt in the fall. This whole time she’d been waiting, looking abandoned, hoping I’d return. The fruit in my satchel that I’d gotten for her had been the one thing I was proud of that day. The one thing I could cling to as evidence that I was doing okay by her.

Watching her, I felt gutted and finished. If I’d been more alert, not so distracted, the thief never would have ripped it from my shoulder so easily. I used to be so guarded and aware. Now I was worn down with grief, my hope for finding Row more madness than optimism.

Slowly it dawned on me: the reason the blue dress was so familiar, the reason it had grabbed my gut like a hook. Yes, Row had that same dress, but it wasn’t one Jacob had packed and taken with them when he took her from me. Because I found that dress in her bedroom dresser after she was gone and I slept with it for days afterward, burying my face in her smell, worrying the fabric between my fingers. It had stayed in my memory because it had been left behind, not because she could be somewhere out there wearing it. Besides, I realized, she would be much older now, too large for that dress. She had grown. I knew this, but she remained frozen in my mind as a five-year-old with large eyes and a high-pitched giggle. Even if I ran across her, would I recognize her immediately as my own?

It was too much, I decided. The constant drain of disappointment every time I reached a trading post and found no answers, no signs of her. If Pearl and I were going to make it in this world, I needed to focus on only us. To shut everything and everyone else out.

So we’d stopped looking for Row and Jacob. Pearl sometimes asked me why we’d stopped and I told her the truth: I couldn’t anymore. I felt they were somehow still alive, yet I couldn’t understand why I hadn’t been able to hear about them in the small communities that were left, tucked high in the mountainsides, surrounded by water.

Now we were drifting, spending our days with no destination. Each day was the same, spooling into the next like a river running into the ocean. Every night I lay awake, listening to Pearl breathe, the steady rhythm of her body. I knew she was my anchor. Every day I feared a raider ship would target us, or fish wouldn’t fill our nets and we’d starve. Nightmares engulfed me and my hand would shoot out for Pearl in the night, rattling both of us awake. All these fears lined up with a little hope wedged in the cracks in between.

I closed the crab pots and dropped them over the side, letting them sink sixty feet. As I surveyed the coast, an odd, fearful feeling, a tiny bubble of alarm, rose in me. The shore was marshland, filled with dark grass and shrubs, and trees grew a little farther back from the shore, crowding up the mountainside. Trees now grew above the old tree line, mostly saplings of poplar, willow, and maple. A small bay lay around the shore’s bend, where traders sometimes anchored or raiders lay in wait. I should have taken the time to scope out the bay and make sure the island was deserted. There was never any quick escape on land the way there was on water. I steeled myself to it; we needed to look for water on land. We wouldn’t last another day otherwise.

Pearl followed my eyes as I gazed at the coast.

“This looks like the same coast with those people,” Pearl said, needling me.

She’d been going on for days about raiders we saw robbing a boat in the distance. We’d sailed away, and I was weary, heart heavy, as the wind pulled us out of sight. Pearl was upset we hadn’t tried to help them, and I tried to remind her it was important we keep to ourselves. But under my rationalizations, I feared that my heart had shrunk as the water rose around me—panic filling me as water covered the earth—panic pushing out anything else, whittling my heart to a hard, small shape I couldn’t recognize.

“How were we going to attack an entire raider ship?” I asked. “No one survives that.”

“You didn’t even try. You don’t even care!”

I shook my head at her. “I care more than you know. There isn’t always room to care more.” I’ve been all used up, I wanted to say. Maybe it was good I hadn’t found Row. Maybe I didn’t want to know what I’d do to be with her again.

Pearl didn’t respond, so I said, “Everyone is on their own now.”

“I don’t like you,” she said, sitting down with her back to me.

“You don’t have to,” I snapped. I squeezed my eyes shut and pinched the bone between my eyebrows.

I sat down next to her, but she kept her face turned from me.

“Did you have your dreams again last night?” I tried to keep my voice kind and soft, but an edge still crept in.

She nodded, squeezing the blood from the snake’s tail down to the hole where its head had been.

“I’m not going to let that happen to us. We’re staying together. Always,” I said. I stroked her hair back from her face and a shadow of a smile crossed her lips.

I stood up and checked the cistern. Almost empty. Water all around but none to drink. My head ached from dehydration and the edges of my vision were beginning to blur. Most days, it was humid; it rained almost every other day, but we were in a dry spell. We’d need to find mountain streams and boil water. I filled Pearl’s water skin with the last of the fresh water and handed it to her.

She stopped playing with her headless snake and weighed the water in her hand. “You gave me all the water,” she said.

“I already drank some,” I lied.

Pearl stared at me, seeing right through me. There was never any hiding from her, not like I could hide from myself.

I fastened my knife in my belt and Pearl and I swam to shore with our buckets for clam digging. I was worried it would be too wet for clams, and we both stumbled along the marsh until we found a drier spot to the south, where the sun fell warm and steady. Little holes peppered the mud plain. We began digging with driftwood, but after a few minutes Pearl tossed her driftwood to the side.

“We won’t find anything,” she complained.

“Fine,” I snapped. My limbs were heavy with fatigue. “Then go up the mountainside and see if you can find a stream. Look for willows.”

“I know what to look for.” She spun on her heel and awkwardly tried to run up the mountainside. The poor thing was still trying to account for the motion of the sea, and she set her feet down too firmly, swaying from side to side.

I kept digging, pulling the mud in piles around me. I hit a shell and tossed the clam in my bucket. Above the wind and waves, I thought I heard voices coming from around the bend in the mountain. I sat back on my heels, alert, listening. A tension settled along my spine and I strained to hear, but there was nothing. I always thought I sensed things on land that weren’t there—hearing a song where there was no music, seeing Grandfather when he was already dead. As though being on land returned me to the past and all the things the past had carried.

I leaned forward and dug my hands into the mud. Tossed another shell into my bucket with a clink. I’d just found another clam when a small, sharp scream pierced the air. I froze, looking up, scanning the landscape for Pearl.

CHAPTER 2 (#u4cdbe80a-f0ef-54df-82c3-c18f582b06b7)

SEVERAL YARDS UP the mountainside, in front of shrubs and a steep rock face, a wiry man held Pearl, her back against his front, a knife at her throat. Pearl was still, her eyes quiet and dark, her arms at her sides, not able to reach the knife at her ankle.

The man had a desperate, off-kilter look on his face. I stood up slowly, my heart pounding in my ears.

“Come with me,” he called out. He had a strange accent I couldn’t place, clipped and heavy on the consonants.

“Okay,” I said, my hands up to show I wasn’t going to try anything, walking toward them.

When I reached them he said, “You move and she goes.”

I nodded.

“I’ve got a ship,” he said. “You’ll work it. Drop your knife on the ground.”

Panic rose up in me as I unfastened my knife and tossed it toward him. He sheathed it at his waist and grinned at me. Holes showed where teeth should be. His skin was tanned to a red brown and his hair grew in sandy patches. A tattoo of a tiger spread across his shoulder. Raiders tattooed their members, often with an animal, though I couldn’t remember which crew used the tiger.

“Don’tcha worry. I’ll care for ya. It’s up thataway.”

I followed the man and Pearl along the side of the mountain, winding our way toward the cove. Rough grass scratched my ankles and I stumbled over a few rocks. The man lowered the knife from Pearl’s neck but kept his hand on her shoulder. I wanted to reach forward and snatch her out of his grasp, but his knife would be at her throat again before I pulled her away. Quick flashes of how things could go ran through my mind—him deciding he only wanted one of us or there being too many people to fight once we reached his ship.

The man started chatting about his people’s colony up north. I wanted him to shut up so I could think straight. A canteen hung from the man’s shoulder and swung back and forth at his hip. I could hear liquid sloshing inside and my thirst rose above even my fear as my parched mouth ached for water, my fingers itching to reach it and unscrew the cap.

“It’s important we have new nations now. Important for …” The man cast his hand out in front of him, as if he could pluck a word from the air. “Organizing.” The man nodded, clearly pleased. “That’s how it was always done, back in the beginning, when we were still in caves. People aren’t organized, we’d all be snuffed out.”

There were other tribes who were trying to make new nations by sailing from land to land, setting up military bases on islands and ports, attacking others and making colonies. Most of them began as a ship that took over other ships, and eventually they began trying to take over communities on land.

The man looked over his shoulder at me and I nodded dumbly, wide eyed, deferential. We were half a mile from our boat. As we approached the bend along the mountainside, the ground dropped away at our side and we walked along a steep rock face. I thought about grabbing Pearl and leaping from the cliff to the water and swimming to our boat, but it was too far in this choppy water. And I couldn’t know if we’d have a clean fall into the water or if there were rocks below.

The man had shifted to talking about his people’s breeding ships. Women were expected to produce a child every year or so, to grow the raider crews. They waited until a girl bled before they moved her to a breeding ship. Until then, she was held captive in a colony.

I’d passed breeding ships when I was fishing, recognized them by their flag of a red circle on white. A flag that warned boats not to approach. Since illness spread so quickly on land, the raiders reasoned the babies would be safer on ships, which they often were. Except when a contagion broke out on a ship and almost everyone died, leaving a ghost ship, unmoored until it crashed against a mountain and drifted to the bottom of the sea.

“I know what you’re thinking,” the man continued. “But the Lost Abbots—we, we do things the right way. Can’t build a nation without people, without taxes, without having people to enforce those taxes. That’s what gives us the chance to organize.

“This yer girl?” the man asked me.

I startled and shook my head. “Found her on a coast a few years back.” He wouldn’t be so keen on separating us if he didn’t think we were family.

The man nodded. “Sure. Sure. They come in handy.”

The wind changed as we began to make our way around the mountain, and voices from the cove now reached us, a clamoring of people working on a ship.

“You look like a girl I know, back at one of our colonies,” the man said to me.

I was barely listening. If I lunged forward, I could reach his right arm, pull it behind his back, and reach for my knife in his sheath.

He reached out and touched Pearl’s hair. My stomach clenched. A gold chain with a pendant hung from his wrist. The pendant was dark snakewood, with the engraving of a crane on it. Row’s necklace. The necklace Grandfather had carved for her the summer we’d gone to see the cranes. It was colorless except the drop of red paint he’d placed between the crane’s eyes and beak.

I stopped walking. “Where’d you get that?” I asked. Blood surged in my ears and my body thrummed like a hummingbird’s wings.

He looked down at his wrist. “That girl. One I was telling you about. Such a sweet girl. I’m surprised she’s made it this long. Doesn’t seem to have it in her …” He gestured with his knife toward the cove. “Don’t have all day.”

I lunged at him and swiped his right leg with my foot. He tripped and I smashed my elbow down on his chest, knocking the air from him. I stomped on the hand holding the knife, grabbed it, and held it to his chest.

“Where is she?” I asked, my voice all breath, barely above a whisper.

“Mom—” Pearl said.

“Turn away,” I said. “Where is she?” I pushed the knife farther between his ribs, the tip digging into skin and membrane. He gritted his teeth, sweat gathering at his temples.

“Valley,” he panted. “The Valley.” His eyes darted toward the cove.

“And her father?”

Confusion furrowed the man’s brow. “She had no father with her. Must be dead.”

“When was this? When did you see her?”

The man squeezed his eyes shut. “I dunno. A month ago? We came here straight after.”

“Is she still there?”

“Still there when I left. Not old enough yet—” He winced and tried to catch his breath.

He almost said not old enough for the breeding ship yet.

“Did you hurt her?”

Even now, a pleased look crossed his face, a sheen over his eyes. “She didn’t complain much,” he said.

I drove the knife straight in, the hilt to his skin, and pulled it up to gut him like a fish.

CHAPTER 3 (#u4cdbe80a-f0ef-54df-82c3-c18f582b06b7)

PEARL AND I stole the man’s canteen and shoved his body over the side of the cliff. As we ran back to the boat I kept thinking of his crew in the cove, wondering how soon they would start searching for him. There was enough wind, I thought, to push us south quickly. Once Bird got behind another mountain it’d be hard to track us.

When we got back to the boat I raised the anchor, Pearl adjusted the sails, and we surged forward, the coast behind us growing smaller, but I still couldn’t breathe steadily. I hid from Pearl under the deck shelter, my whole body shaking, not unlike how the man’s body shook when he died. I’d been in fights before, tense moments with weapons out, but I hadn’t killed. Killing that man was like stepping through a door to another world. It felt like a place I’d already been to but had forgotten, hadn’t wanted to remember. It didn’t make me feel powerful; it made me feel more alone.

We sailed south for three days until we reached Apple Falls, a small trading port nestled on a mountain that had been in British Columbia. The water in the canteen lasted us only a day, but late on the second day it rained a small bit, just enough that we weren’t ill with thirst by the time we reached Apple Falls. I dropped the anchor over the side and glanced at Pearl. She stood at the bow, staring at Apple Falls.

“I didn’t want you to see that,” I said to Pearl, watching her closely. Pearl hadn’t spoken to me much since.

Pearl shrugged.

“He was going to hurt us. You don’t think I should have done it? You think he was a good person?” I asked.

“I just didn’t like it. I didn’t like any of it,” she said, her voice small. She paused, as if thinking, then said, “Desperate people.” She looked at me a little too intently. I always said to her, when she asked me why people were cruel, that desperate people did desperate things.

“Yes,” I said.

“Will we try to find her now?”

“Yes,” I said, the word out of my mouth before I knew I’d already decided it. A response beyond reason. Just the image in my mind of Row in danger and me moving toward her, with no choice, only one direction to move, the way rain falls from the sky and does not return to the heavens.

Though I was surprised to realize this, Pearl showed no shock. She merely looked at me and said, “Will Row like me?”

I walked to her, squatted, and wrapped my arms around her. Her hair smelled like brine and ginger and I buried my face in it, her body as tender and vulnerable as the night I birthed her.

“I’m sure of it,” I said.

“Are we going to be okay?” Pearl asked.

“We’re going to be fine.”

“You said everyone is alone. I don’t want to be alone,” Pearl said.

My chest tightened and I pulled her close to me again. “You won’t ever be alone,” I promised. I kissed the top of her head. “We better count these,” I said, gesturing to the buckets of fish laid out on the deck.

Row is alone out there, I kept thinking, weighing each dead fish in my palm, one part of me asking how much it was worth, the other part imagining her alone on some coast. Did Jacob die? Did he abandon her? My hands shook with cold rage at this thought. He abandons people; that’s what he does.

But he wouldn’t do that to her, I argued with myself, feeling myself being pulled back into the hatred that had kept me awake at night for years after he left. I’d been blinded by love and now, I knew, I was blinded by hate. I had to focus. To remember Row and forget him.

The last three days we’d sailed, a part of me thought of Row incessantly. I had the sense that my entire body was plotting how to reach her, while my consciousness focused on tightening the rope at the block or reeling in fishing line, the small daily tasks that grounded me. There was both a low thrum of panic and shock at discovering she was alive, and a strange animal tranquility as I moved about the boat as if it were simply another day. It was what I’d dreamed of and hoped for and also what I’d feared. Because her being alive meant I had to go after her, had to risk everything. What kind of mother abandons her child in her hour of need? And yet, wouldn’t taking Pearl on this journey be a kind of abandonment of her? An abandonment of the peaceful life we’d fought to build together?

Pearl and I loaded the salmon and halibut into four baskets. We had gutted and smoked the salmon already on our boat, but the halibut was fresh from this morning, which could give us bargaining power.

Apple Falls was aptly named—apple trees had been planted in a clearing between the peaks of two mountains. Thieves were shot by the guards of the orchard, who had watchtowers on each mountain. I was hoping we’d be able to trade for at least half a basket of apples, plus some grain and seed. At our last trading post we had only three baskets of fish and could barely trade for the rope, oil, and flour we needed. We needed to trade for some vegetable seeds so I could grow a few more vegetables on board. Right now we only had a half-dead tomato plant. Beatrice, my old friend at Apple Falls, would give me a better deal for my fish than at any other port.

Water rippled against the mountainside and the bank rose in a steep incline up the mountain, with a small peat ledge for a dock. A wooden boardwalk, half submerged, had been cobbled together over the years.

We docked our boat and paid the harbor fees with a crate of metal scraps I had found while hunting the shallows. Bird was one of the smallest boats in the harbor, but it was sturdily built. Grandfather had designed the boat to be simple and easy to maneuver. One square mast, a rudder, a punting pole, and oars on each side. A deck cover made from old rugs and plastic tarp where we slept at night. He’d made it from the trees in our yard back in Nebraska at the beginning of the Six Year Flood, when we knew that fleeing was our only chance to survive.

Water had already covered the coasts around the world by the time I was born. Many countries had been cut to half their size. Migrants fled inland, and suddenly Nebraska became a bustling, crowded place. But no one knew the worst was yet to come—the great flood that lasted six years, water rising higher than anyone could imagine, whole countries becoming seafloors, each city a new Atlantis.

Before the Six Year Flood, earthquakes erupted and tsunamis struck constantly. The ground itself seemed heavy with energy. I’d hold out my hand and feel the heat in the air like the pulse of an invisible animal. On the radio we heard rumors that the seafloor had split, water from within the earth seeping into the ocean. But we never knew for certain what happened, only that the water rose around us as if to swallow us up in a watery grave.

People called the years the coasts disappeared the Hundred Year Flood. The Hundred Year Flood didn’t last exactly a hundred years, because no one knew for sure exactly when it began. Unlike a war it had no call to arms, no date by which we could remember its beginning. But it lasted close to a hundred years, a little longer than a person’s lifetime, because my grandfather always said that when his mother was born New Orleans existed and when she died it did not.

What followed the Hundred Year Flood was a series of migrations and riots over resources. My mother would tell me stories of how the great cities fell, when electricity and the Internet faltered on and off. People would show up on doorsteps at homes in Indiana, Iowa, Colorado, clinging to their belongings, wide eyed and weary, asking to be let in.

Near the end of the Hundred Year Flood, the government moved inland, but its reach was limited. I was seventeen when I heard over the radio that the president had been assassinated. But then a month later, a migrant passing through said he’d fled to the Rockies. And then later, we heard a military coup had taken over a session of Congress and members of the government had fled after that. Communication was breaking down by that point, the whole world reduced to a rumor, and I stopped listening.

I was nineteen when the Six Year Flood began and had just met Jacob. I remember standing next to him watching footage of the White House flood, only the flag on the roof visible above the water, each wave soaking the flag until it lay sagging against the pole. I imagined the interior of the White House, so many faces staring out of its paintings, water trickling down hallways into all its chambers, sometimes loud and sometimes quiet.

The last time my mother and I watched television together it was the second year of the Six Year Flood and I was pregnant with Row. We saw footage of a man lying on an inflatable raft, balancing a whiskey bottle on his tummy, grinning up at the sky, as he floated past a skyscraper, trash swirling around him. There were as many ways to react as people, she always said.

This included my father, who was the one to teach me what the floods meant. The blinking on and off of communication was familiar to me, the crowds of people at soup kitchens normal. But when I was six I came home early from school with a headache. The garden shed door was open and through the opening I saw only his torso and legs. I stepped closer, looked up, and saw his face. He’d hung himself from a rafter with a rope.

I remember screaming and backing away. Every cell in me was a small shard of glass; even breathing hurt. I ran inside and looked for my mother, but she wasn’t home from work. Cell towers were down that month, so I sat on the front stoop and waited for my mother to come home. I tried to think of how to tell her but words kept wincing away from me, my mind recoiling from reality. Many days, I still feel like that child on the stoop, waiting and waiting, my mind empty as a bowl scooped clean.

After my mother had gotten home, we found a mostly empty bag of groceries on the table with a note from my father: “The shelves were bare. Sorry.”

I thought when I had my own children I’d understand him more, understand the despair he felt. But I didn’t. I hated him even more.

PEARL TUGGED ON my hand, pointing to a cart of apples sitting just past the dock.

I nodded. “We should be able to get a couple,” I said.

The village was a clamoring, crowded throng of people and Pearl stuck close to me. We slung the baskets of fish on two long poles so we could carry them on our shoulders and we started up the long winding path between the two mountains.

I felt relief at being on land again. But as the crowd closed around me, I felt a new kind of panic, different from anything I felt when I was alone on the waves. An out-of-control sensation. Being the foreigner, the one who had to relearn the ever-changing rules of each trading post.

Pearl wasn’t ambivalent like I was, hovering between relief and panic. She hated being on land, the only benefit being that she could hunt snakes. Even as a baby she hated being on land, refusing to fall asleep when we camped on the shores at night. Sometimes she got nauseous on land and went out for a swim to calm her nerves while we were at a port.

The land was filled with stumps of cut trees and a thick ground cover of grasses and shrubs. People seemed to be crawling over one another on the path, an old man bumping into two young men carrying a canoe, a woman pushing her children in front of her. Everyone’s clothes were dirty and torn and the smell of so many people living close together made me dizzy. Most people I saw in ports were older than Pearl, and Apple Falls was no different. Infant mortality was high again. People would talk on the streets about our possible extinction, about the measures needed to rebuild.

Someone knocked one of Pearl’s baskets to the ground and I cursed them and quickly scooped up the fish. We passed the main trading post and saloon and cut across the outdoor market, smells of cabbage and fresh-cut fruit lingering in the air. Shacks littered the outskirts of town as we traveled farther up the path, toward Beatrice’s tent. The shacks were cobbled together with wood planks or metal scraps or stones stacked together like bricks. In the dirt yard of one shack, a small boy sat cleaning fish, a collar around his neck, attached to a leash that was tied around a metal pole.

The boy looked back at me. Small bruises bloomed like dark flowers on his back. A woman came and stood in the doorway of the shack, arms crossed over her chest, staring back at me. I looked away and hurried on.

Beatrice’s tent stood on the southern edge of the mountain, hidden by a few redwoods. Beatrice had told me she guarded her trees against thieves with her shotgun, sometimes awakening at night to the sound of an ax on wood. But she only had four shotgun shells left, she had confided in me.

Pearl and I squatted and slid the poles from our shoulders. “Beatrice?” I called out.

It was silent for a moment and I worried it was no longer her tent, that she was gone.

“Beatrice?”

She poked her head through the tent opening and smiled. She still wore her long gray hair in a braid down her back and her face had deeper creases, a sun-etched rough texture.

She sprang forward and grabbed Pearl in a hug. “I was wondering when I’d see you again,” she said. Her eyes darted between Pearl and me, taking us in. I knew she feared there’d come a day when we didn’t return to trade, just as I feared there’d come a day when I’d come to trade and her tent would be taken over by someone else, her name a mere memory.

She hugged me and then pulled me back by my shoulders and eyed me. “What?” she asked. “Something’s different.”

“I know where she is, Beatrice. And I need your help.”

CHAPTER 4 (#u4cdbe80a-f0ef-54df-82c3-c18f582b06b7)

BEATRICE’S TENT WAS the most comfortable place I’d been in the past seven years, since Grandfather and I took to the water. An oriental rug lay over the grass floor, a coffee table sat in the middle of the tent, and off to the side several quilts were piled on top of a cot. Baskets and buckets of odds and ends—twine, coils of rope, apples, empty plastic bottles—were scattered around the periphery of the tent.

Beatrice scurried around her tent like a beetle, wiry and nimble. She wore a long gray tunic, loose pants, and sandals. “Trade first, talk later.” She set a tin cup of water in my hands.

“So what do you have?” she asked. She peered into our baskets. “Just fish? Myra.”

“Not just salmon,” I said. “There are some halibut. Nice big ones. You’ll get a big fillet off this one.” I pointed to the largest halibut that I had positioned on top of a basket.

“No driftwood, no metal, no fur—”

“Where am I supposed to get fur?”

“You said your boat was fifteen feet long. You could keep a goat or two. It’d be good for milk, and later fur.”

“Livestock at sea is a nightmare. They never live long. Not long enough to breed, so it’s hardly worth it,” I said. But I let her scold me because I knew she needed to. A maternal itch, the pleasure of scolding and soothing.

Beatrice bent down and sorted through the fish. “You could tan leather on a ship easily. All that sun.”

We finally agreed to trade all my fish for a second tomato plant, a few meters of cotton, a new knife, and two small bags of wheat germ. It was a better trade than I expected and only possible because Beatrice was overly generous with Pearl and me. She and my grandfather had become friends years before, and after he passed away, Beatrice became more and more generous with her trades. It made me feel both guilty and grateful. Though I was known in many of the trading posts as a reliable fisher, Pearl and I still barely scraped by with our trades.

Beatrice gestured to the coffee table and Pearl and I sat on the ground while Beatrice stepped outside to light a fire and get started on supper. We ate salmon I had brought, with boiled potatoes and cabbage and apples. As soon as Pearl was finished eating she curled up in a corner of the tent and fell asleep, leaving Beatrice and me to talk quietly as the night grew darker.

Beatrice poured me a cup of tea, something minty and herbal, with leaves floating on the surface. I got the impression she was gathering her strength.

“So where is she?” Beatrice asked finally.

“A place called the Valley. Have you heard of it?”

Beatrice nodded. “I’ve only traded with people from there once. It’s a small settlement—maybe a few hundred people. People who make it there don’t normally make it back. Too isolated. Rough seas.” She gave me a long look.

“Where is it?”

“How’d you get this information? Can you trust it?” she asked.

“I found out from a raider with the Lost Abbots. I don’t think he was lying. He’d already told me most of the information before …”

I paused, suddenly uncomfortable. A flicker of understanding crossed over Beatrice’s face.

“Was he your first?”

I nodded. “He captured Pearl and me.”

“Those fighting lessons have paid off,” she said, though she sounded more sad than satisfied. Grandfather taught me to sail and fish, but Beatrice had taught me to fight. After Grandfather passed away, Beatrice and I would practice under the trees around her tent, a few paces apart, me mimicking the motions of her hands and feet. Her father had taught her to fight with knives back during the early migrations and she wasn’t gentle with me during our lessons, tripping me up with a heel, yanking my arm behind my back until it nearly snapped.

The tea steamed before me and I warmed my hand around the cup. I felt my body try to steady me with stillness, but a cascade still fell within me, as if inwardly I were scattering to pieces.

“Can you help me?” I asked. “Do you have maps?” I knew she had maps—she could charge wood and land for the maps she had, which was also why she had to sleep with a shotgun at night. I’d never heard of the Valley, but I hadn’t heard of many places.

When Beatrice didn’t say anything, I said, “You don’t want me to go.”

“Have you learned to navigate?” she asked.

Since I couldn’t navigate, I only sailed between trading posts along the Pacific coast, which I knew well from sailing with Grandfather.

“Beatrice, she’s in danger,” I said. “If the Lost Abbots are there, the Valley is a colony now. Do you know how old she is? Almost thirteen. They’ll be transitioning her to a breeding ship any day now.”

“Surely Jacob is protecting her. He may pay extra taxes to keep her off the ship.”

“The raider said she had no father with her,” I said.

Beatrice looked at Pearl, curled into a ball, sleeping on her side, her face serene. One of her snakes lifted its head from the pocket of her trousers and slid over her leg.

“And Pearl? What of her?” Beatrice asked. “What if you go on this journey only to lose her, too?”

I stood up and stepped out of the tent. The night had grown cold. I sank my face in my hands and wanted to wail, but I bit my lips together and squeezed my eyes so hard they hurt.

Beatrice came out and set her hand on my shoulder.

“If I don’t try—” I started. The sound of bats’ wings beat the air above us as they cut across the moon in fluttering black shapes. “She’s alone, Beatrice. This is my one chance to save her. Once they get her on a breeding ship, I won’t find her again.”

What I didn’t tell her was that I couldn’t be my father. Couldn’t leave her on a stoop somewhere when she needed me.

“I know,” she said. “I know. Come back inside.”

I hadn’t come to Beatrice only because she would help me, but because she was the only person who could understand. Who knew my whole story, going all the way back to the beginning. No other living person besides Beatrice knew how I met Jacob when I was nineteen and didn’t even know the Six Year Flood had begun. He was a migrant from Connecticut, and on the day I met him I was drying apple slices in the sunlight on our front porch. It was over a hundred degrees every day that summer, so we dried fruit on the porch and canned the rest that we harvested. I’d cut twenty apples into thin slices, lining them on every floorboard along the porch, before stepping inside to check the preserves over the fire. In the mornings I worked for a farmer to the east, but in the afternoons I was home, helping my mother around the house. She worked as a nurse only occasionally by that point, doing home visits or treating people in makeshift clinics, trading her care and knowledge for food.

When I came back out a row of the apple slices was gone and a man stood frozen, bent over the porch, one hand on a slice, the other hand holding open a bag that hung from his shoulder.

He turned and ran and I dashed across the porch after him. Sweat trickled down my back and my lungs burned, but I caught up to him and tackled him, both of us sprawling across the neighbor’s lawn. I wrestled the bag from him and he almost didn’t resist, his arms up to protect his face.

“I thought you’d be fast, but you’re even faster,” he said, panting.

“Get away from me,” I muttered, standing up.

“Can’t I have my bag back?”

“No,” I said, turning on my heel.

Jacob sighed and looked to the side with a mildly dejected look. I had the feeling he was accustomed to defeat and stomached it quite well. Later that night I wondered why I’d chased a stranger and not been more afraid, when usually I took pains to avoid strangers and feared an attack. Somehow, I realized, I’d known he wouldn’t hurt me.

He slept in a neighbor’s abandoned shed that night and waved to me in the morning. While I was weeding the front garden he watched me. I liked him watching me, liked the slow burn it gave me.

A few days later, he brought a beaver he’d trapped at the nearby river and laid it at my feet.

“Fair?” he asked.

I nodded. After that he’d sit and talk to me while I worked and I grew to like the rhythm of his stories, the curious way they always ended, with a note of exasperation mixed with delight.

Catastrophe drove us together. I don’t know that we would have fallen in love without that perfect mix of boredom and terror, terror that bordered on excitement and quickly became erotic. His mouth on my neck, my skin already moist with sweat, the ground wet beneath us, the heat in the air making rain every few hours, the sun drying it away. My heart already beating faster than it should, nerves calmed only by enflaming them more.

The only photo we got at our wedding came from an instant-print camera my mother borrowed from a former patient. We were standing in the sunlight on our front porch, my belly already round with Row, squinting so much you couldn’t see our eyes. And that’s how I remember those days: the heat and light. The heat never left, but the sunlight dimmed so quickly during each storm that you felt you stood in a room where some god kept turning a light on and off.

Beatrice ushered me back into the tent. She walked over to her desk, wedged between the cot and a shelf of pots. She rummaged through some papers and took out a rolled map that she spread out across the table in front of me. I knew the map wouldn’t be completely accurate; no accurate maps existed yet, but some sailors had attempted to chart the major landmasses that now existed above water.

Beatrice pointed to a landmass in the upper middle of the map. “This was Greenland. The Valley is in this southeast corner.” Beatrice pointed to a small hollow surrounded by cliffs and sea on both sides. “Icebergs” was written across the seas surrounding the small land mass. No wonder I hadn’t been able to find Row after years of looking; I hadn’t wanted to consider she could be so far away.

“It’s protected by the elements and raiders because of these cliffs, so I’m surprised the Lost Abbots made it a colony. Traders from the Valley said it was safer than other land because it’s so isolated. But it’s hard to get to. This”—she pointed to the Labrador Sea—“is Raider’s Aisle.”

I’d heard of Raider’s Aisle. A stormy section of dark seas where raiders lurked, often taking advantage of damaged ships or lost sailors to plunder their goods. When I passed through ports I’d barely listened to the tales, always assuming I’d never have to go near it.

“The Lily Black keep several of their ships in Raider’s Aisle,” Beatrice said. “News is they’re moving a few more ships up north.”

The Lily Black was the largest raider crew, with a fleet of at least twelve ships, maybe more. Ships made from old tankers fitted with new sails or small boats rowed by slaves. A rabbit tattoo marked their necks, and trading posts buzzed with rumors of other communities they’d attacked and the taxes they’d extracted from their colonies, working the civilians almost to death.

“And,” Beatrice went on, “you’ll have to deal with the Lost Abbots.”

“But if the Valley is already a colony, the Lost Abbots will only have left a few men behind to guard it. I can get Row out and we can leave—sail somewhere else before they return.”

Beatrice raised her eyebrows. “You think you can take them alone?”

I rubbed my temple. “Maybe I can sneak in and out.”

“How do you plan to get there?” she asked.

I dropped my forehead into my palm, my elbow resting on the table, the steam from the tea warming my face. “I’ll pay you for the map,” I said, so tired my body ached for the ground.

She rolled her eyes and pushed it toward me. “You don’t have the boat for this journey. You don’t have the resources. And what if she’s not still there?” Beatrice asked.

“I have some credit in Harjo I can use for wood to build a new boat. I’ll try to learn navigation—I’ll trade for the tools.”

“A new boat will cost a fortune. You’ll go into debt. And a crew?”

I shook my head. “We’ll sail it ourselves.”

Beatrice sighed and shook her head. “Myra.”

Pearl stirred in her sleep. Beatrice and I glanced at her and each other. Beatrice’s eyes were tender and sad, and when she reached out and grasped my hand, the veins in her hands were as bright blue as the sea.

CHAPTER 5 (#u4cdbe80a-f0ef-54df-82c3-c18f582b06b7)

THE NEXT MORNING Beatrice and I sat in the grass outside her tent, making lures with thread she’d scavenged in an abandoned shack up the mountainside. I knotted the bright red thread around a hook, listening to Beatrice tell me about how things were before the old coasts disappeared. Born in San Francisco, she was a child when it flooded and her family fled inland. Sometimes when she talked, I could tell she was trying hard to remember how things were when she was young, before all the migrations started, but that she couldn’t really. Her stories felt like stories about a place that never really existed.

The neighbors to her right, who lived in a one-room sod house dug out from the side of the mountain, were bickering, their voices rising and railing against one another. Beatrice told me about the Lost Abbots and how they began. They were a Latin American tribe, mostly people from the Caribbean and Central and South America. They began as many raider tribes began: as a private military group employed by governments during the Six Year Flood, when civil wars continued to destroy countries. After all known countries fell, they developed into a kind of sailing settlement, a tribe trying to build a new nation.

“Just last week, Pearl and I saw a small boat taken over by raiders north of here,” I said. “It was a fishing family. I heard their screams and—” I squinted hard at my lure and bit the thread to cut it. “We sailed away.” I had felt a heaviness in my gut when I placed my hand on the tiller, turning us south, away from their screams. I felt hemmed in and trapped on the open sea, left with few choices.

“I didn’t feel bad,” I confessed to Beatrice. “I mean, I did. But not as much as I used to.” I wanted to go on and say: It’s like I’ve gone dull inside. Every surface of me is hardened and rubbed raw. Nothing left to feel.

At first Beatrice didn’t respond. Then she said, “Some say raiders will control the seas in coming years.”

I had heard this before, but I didn’t like hearing it from Beatrice, who was never one to deal in conspiracies and doomsday speculation. She went on to tell me news from a trading post to the south, how governments were trying to form to protect and distribute resources. How civil wars were breaking out over laws and resources.

Beatrice told me about how some new governments accepted help from raiders and willingly became colonies, controlled by raider captains. The raiders offered protection and gave extra resources to the burgeoning community—food, supplies the raiders had stolen or scavenged, animals they’d hunted or trapped. But the community was bound to pay back any help offered with interest. Extra grain from the new mill. The best vegetables from the gardens. Sometimes the community had to send a few of its own people to work as guards on breeding ships and colonies. The raiders’ ships circled between their colonies, picking up what they needed; their guards enforced rules while they were gone.

My conversations with Beatrice followed the same rhythm each time. She urged me to move onto land and I urged her to move onto water. But not this time.

Beatrice began telling me a story about something that had happened to her neighbors the previous week. She told me how in the middle of the day shouts and yelling had erupted, coming from the sod dugout. Two men stood outside the dugout, shouting and pointing at a girl who stood between her mother and father. The girl looked about nine or ten years old. One of the men stepped forward and grabbed the girl, holding her arms behind her back as she tried to run toward her mother.

The father charged forward toward his daughter, but the other man punched him in the stomach. The father doubled and the man kicked him to the ground.

“Please,” the father pleaded. “Please—I’ll pay up. I’ll pay.”

The man stomped on the father’s chest with the heel of his boot and the father curled in pain and rolled to his side, his hand shaking and stirring up small clouds of dust.

The girl screamed for her father and mother, her arms held taut and long behind her as she tried to run toward them. The man who’d stomped on her father smacked her hard across the face, wound rope around her wrists, and knotted them. The other man lifted her body over his shoulder and turned around.

She didn’t scream again, but Beatrice could hear her soft cries as the men carried her away.

An hour later the village had begun to swarm with people again, footsteps echoing on the dirt paths, bright children’s voices calling to one another. Beatrice’s neighbor across the road leaned out the open window of her shack to hang a dish towel on a peg. Everything had moved on as though a child hadn’t just been taken from her parents.

Beatrice shook her head. “It was probably a private affair. Maybe a private debt being collected and no one wanted to interfere. They don’t have control here—but still.”

Both of our hands had gone still, the hooks glinting in the sunlight in our laps. Beatrice cast about for words.

“Still, I worry,” she said. “A resistance is being organized here. You could join us. Help us.”

“I don’t join groups and I don’t care about resistance. I’m not staying on land, waiting for someone to take her,” I said, nodding at Pearl, who had caught a snake and was dropping it into one of our baskets. Pearl came and sat next to us, eyes on the grass, another snake still in her hands.

“They built a library, you know,” Beatrice said softly, with pain in her voice.

“Who?” I asked.

“Lost Abbots. At one of their bases in the Andes—Argali. They even put windows in. And shelves. Books salvaged from before and new ones being transcribed. People travel for miles to see it. Some friends told me they built it to show their commitment to the future. To culture.”

Beatrice’s mouth tightened. Before the floods, she’d been a teacher. I knew how important learning and books were to her. How much it had pained her when her school closed and her students scattered across the country. I knew also of her lover who had been killed on his fishing boat three years before by a raiding tribe. She had been scared of the water even before that, and she cloaked this fear as a love for land.

“Little bit of good in everything,” Beatrice said.

I thought of the raider on the coast talking about new nations and the need to organize people. I’d heard that argument before in saloons and trading posts. That the raiders’ wealth could rebuild society faster. Forcing people to go without would get us back to where we were sooner.

I described what a library looked like to Pearl. “Do you want to go to a place like that?” I asked her.

“Why would I?” she asked, trying to wrap the snake around her wrist as he resisted her.

“You could learn,” I said.

She frowned, trying to imagine a library. “In there?”

I came up against this again and again with Pearl. She didn’t even want what I so sorely missed, had no conception of it to desire it.

It wasn’t just the loss of a thing that was a burden but the loss even of desiring it. We should at least get to keep our desire, I thought. Or maybe it’s how she was born. Maybe she couldn’t want something like that after being born in a world like this.

Beatrice didn’t say anything more, and after we finished making lures I went into her tent to pack. I packed our grain in a linen sack, tucking it in the bottom of a bucket. I set the tomato plant in a basket and tucked a blanket around it, a gift from Beatrice. I thought of Row, imagined her wrists cinched together with rope, her cries silenced or ignored. I shuddered.

Beatrice handed me the rolled-up map. “I don’t even have a compass to give you.”

“You’ve given me more than I hoped for,” I said.

“One more thing.” Beatrice pulled a photo from her pocket and placed it in my hand. It was a photo of Jacob and Row, taken a year before she’d screamed my name in that boat as it sped away. Grandfather and I gave it to Beatrice so she could ask traders in Apple Falls if they’d been seen. In the photo Jacob’s auburn hair had a gold sheen from the sunlight. His cleft chin and crooked nose, caused by a childhood schoolyard fight, made his face look angular. Row looked delicate with her small sloping shoulders and shining gray-blue eyes. They were my eyes, almond shaped, hooded. Eyes that looked like the color of the sea. She had a scar, shaped like the blade of a scythe, curving over an eyebrow and across a temple. When she was two she had fallen and cut her face on a metal toolbox.

I rubbed Row’s face with my thumb. I wondered if Jacob had built them a house at the Valley. That’s what he always said he wanted to do for me, years ago. Jacob worked as a carpenter like Grandfather. They began building our boat together, but after a while it was only Grandfather working on the boat. I had listened to their yelling and arguing for weeks and then suddenly it was quiet. That was two months before Jacob left with Row.

Beatrice reached out and tucked a strand of hair behind my ear and wrapped her arms around me. “Come back,” she whispered in my ear, the phrase she whispered in my ear each time I visited. I could feel in how her embrace lingered that she didn’t think I would.

CHAPTER 6 (#ulink_bd3e4709-255b-5713-9db4-b68707c34b88)

PEARL AND I set sail to the south, following the broken coast. It was rumored there was more wood for building boats down south in Harjo, a trading post in the Sierra Nevada Mountains. I’d use my credit at Harjo for wood and trade my fishing skills for help in building a bigger boat. My little boat would never handle the tumultuous seas in the north. But even if I could build a bigger boat, would I be able to navigate and sail it? Desperate people could always be found to join a ship’s crew, but I couldn’t stand the thought of traveling with other people, people I might not be able to trust.

I strung a line through a hook and knotted it and did it again for another pole. Pearl and I would fish over the side of the boat later in the evening, maybe even try some slow trolling for salmon. Pearl sat next to me, organizing the tackle and bait, dividing the hooks by size and dropping them in separate compartments.

“Who’s in this photo?” Pearl asked, pointing to the photo of Row and Jacob sitting on top of a basket filled with rope.

“A family friend,” I said. Years ago, when she’d asked about her father, I told her he had died before she was born.

“Why’d you ask that man about my father?”

“What man?” I asked.

“The one you killed.”

My hands froze over the bucket of bait. “I was testing him,” I said. “Seeing if he was lying.”

The sky to the east darkened and clouds tumbled toward us. Miles away a haze of rain clouded the horizon. The wind picked up, filling our sail and tilting the boat. I jumped up to adjust the sail. It was midafternoon and the day had begun clear, with an easy, straight wind, and I thought we’d be able to sail south for miles without making adjustments.

At the mast I started reefing the sails so we’d bleed wind. Around the coast to the west, waves rose several feet, the crashing white water swirling under the dark sky. We’d faced squalls before, been tossed in the wind, almost capsized. But this one was driving straight west, pushing us away from the coast. A rag on deck whipped up into the air, almost smacking me as it flew past and disappeared.

The storm approached like the roar of a train, slowly getting louder and louder until I knew we’d be shaking inside of it. Pearl climbed over the deck cover and stood by me. I could tell she was resisting the urge to throw her arms around me. “It’s getting bad,” she said, a tremor in her voice. Nothing else scared Pearl like storms; she was a sailor afraid of the sea. Afraid, she’d told me before, of shipwreck. Of having no harbor.

“Take the gear under the deck cover,” I told her, the wind catching my words and flattening them. “And bolt it down.”

I tried to ease the tension of the sail’s rigging, loosening the sheet, but the block was rusty and kept catching. When I finally got it loose, the wind picked up, knocking me backward against the mast, the rope flying through the block, sending the halyard soaring in the wind. I held on to the mast as Bird leaned left, waves rising and water spraying across the deck.

“Stay under!” I shouted to Pearl, but my words were lost in the wind. I climbed across the side of the deck cover, running toward the stern, but I slipped and slid into the gunwale. I scrambled to my feet and began tightening the rope holding the rudder, winding it around the spool, turning the rudder so we’d sail into the wind.

Thunder roared, so loud I felt it in my spine, my brain vibrating in my skull. Lightning flashed and a wave crashed over Bird, and I grabbed the tiller to steady myself. I dropped to my hands and knees, scrambled toward the deck cover, and ducked inside as another wave hit us, foaming overboard.

I wrapped myself around Pearl, tucking her under me, clutching her with one arm and holding on to a metal bar drilled into the deck with my other hand. Bird rocked violently, water pouring under the deck cover, our bodies jostling like shaken beads in a jar. I prayed the hull wouldn’t break.

Pearl curled in a tight ball and I could feel her heart beating like a hummingbird’s wings against my arm. The wind was blowing straight west, pushing us out of coastal waters and deeper into the Pacific. If we were pushed any farther offshore, I didn’t know how we’d make it back to a trading post.

Some dark feeling washed over me that felt like rage or fear or grief, something all sharp corners in my gut, like I’d swallowed glass. Row and Pearl rippled through my mind like shadows. The same question kept rising in me: To save one child, would I have to sacrifice another?

THE DAY MY mother died I had been at the upstairs window, four months pregnant with Pearl, hand on my belly, thinking of preeclampsia, placenta abruption, a breech baby, all the things I’d thought about when I was pregnant with Row. But now, with no hospitals, not even makeshift ones run out of abandoned buildings, they seemed like certain death. I knew my mother would help me deliver Pearl like she’d helped with Row, but I was still more nervous about this birth.

We had lost Internet and electricity for good the month before and we watched the horizon daily, fearing the water would arrive before Grandfather finished the boat.

In the block behind our house, a neighbor’s front yard held an apple tree. Mother had to stretch to pick them, a basket hooked over her arm, her hair shining in the sunlight. The yellow and orange leaves and red apples looked so bright, almost foreign, as though I already was thinking of them as lost things, things I’d rarely see again.

Behind her I saw a gray wall building, rising upward toward the sky. I was perplexed at first, my mind too shocked to comply, even though this was what we’d been waiting for. The water wasn’t supposed to be here yet. We were supposed to have another month or two. That’s what everyone on the streets had been saying. All the neighbors, all the people pushing grocery carts full of belongings as they migrated west toward the Rockies.

I didn’t understand how it was so quiet, but then I realized we were in the middle of a roar, a deafening crashing, the collision of uprooted trees, upended sheds, lifted cars. It was as if I couldn’t hear or feel anything, all I could do was watch that wave, the water mesmerizing me, obliterating my other senses.

I think I screamed. Hands pressed on glass. Grandfather, Jacob, and Row ran upstairs to see where the commotion came from. We stood together at the window, frozen in shock, waiting for it to come. The water rose as if the earth wanted vengeance, the water creeping across the plains like a single warrior. Row climbed into my arms and I held her as I had when she was a toddler, her head on my shoulder, her legs wrapped around my waist.

Mother looked up at the water and dropped the basket of apples. She ran toward our house, crossing the street, passing a house and almost reaching our backyard when the wave crashed around her. The wave dipped over her, its white spray falling around her.

I couldn’t see her anymore and the water thundered around our house. We held our breath as the water rose around the house, climbing up the siding, breaking the windows and flowing inside. It filled up the house like a silo full of corn. The house shuddered and shook and I was certain it’d splinter into pieces, that our hands would be ripped from one another. The water rose, climbing each stair toward the attic.

I looked back out the window, praying I’d see my mother reappear, surface for a breath of air. After the water settled, the surface was still and my mother did not come up to break it.

The water settled a few feet below our upstairs window. We waded and swam through the water for weeks afterward but could never find her body. We later found out the dam had broken half a mile from our house. Everyone had said it would hold.

After Mother was gone I kept wanting to tell her about how things were changing, in me and around me, Pearl’s first kicks, the water covering all the prairie as far as the eye could see. I’d turn to speak to her and be reminded she was gone. This is how people go crazy, I thought.

It was only a month later that Jacob would take Row. Only Grandfather and I were left in that house, sitting in the attic, that empty room the length of our house, as the boat slowly filled it.

A month after Jacob left we took the attic wall out with a sledgehammer and pushed the boat out of the house and onto the water. The boat was fifteen feet long, five feet wide, and looked like a large canoe with a small deck cover at the back and a single sail in the middle. We loaded the boat with supplies we’d been hoarding for the past year—bottles of water, cans of food, medical supplies, bags of extra clothing and shoes.

We sailed west, toward the Rocky Mountains. At first, the air was thin and felt hard to breathe, as if my lungs kept clutching for something more. Three months later I awoke with birthing pains. The wind was so strong it rocked the boat like a cradle and I rolled back and forth under the deck cover, gritting my teeth, clutching the blankets around my body, crying in the lulls between contractions.

When Pearl came she was glistening and pale and silent. Her skin looked like water. As if she’d risen out of the depths to meet me. I held her to my chest and rubbed her cheek with my thumb and she broke into a wail.

A few hours later, when the sun rose and she was suckling at my breast, I heard gulls above us. Holding Pearl at my breast was both like and unlike when I held Row at my breast. I tried to hold the feeling of both of them in myself but couldn’t; one kept sliding away and replacing the other. Deep down, I had known that one couldn’t replace the other, though I now discovered I had been hoping Pearl could replace Row. I placed my nose on Pearl’s forehead, smelling her newness, her freshness. I mourned the loss of it, the loss I felt before it happened.

In Grandfather’s last days he began speaking nonsense more and more. Sometimes talking to the air, addressing people he’d known in the past. Sometimes speaking in a dream language that I would have found beautiful if I wasn’t so tired.

“Now, you tell my girl that a feather can hold a house,” Grandfather said. I wasn’t sure if by “my girl” he meant my mother, myself, Row, or Pearl. He’d call all of us “his girls.”

“Who do you want me to tell?”

“Rowena.”

“She isn’t here.”

“Yes, she is, yes she is.”

This irritated me. Most of the people he spoke to were dead. “Row isn’t dead,” I said.

Grandfather turned to me, shock on his face, his eyes wide and innocent. “Of course not,” he said. “She’s around the corner.”

A week later Grandfather died sometime in the night. I had just finished nursing Pearl and had laid her in a small wooden box Grandfather had made for her. I crawled over to where Grandfather slept, my fingers outstretched to shake him awake. When I touched him, he was cold. His skin not yet ashen, only slightly pale, the blood having settled. He otherwise looked the same as he always did when he slept: eyes closed, mouth slightly agape.

I leaned back on my heels, staring at him. That he could pass with so little ceremony stunned me. I had never expected sleep to take him, of all things. Pearl whimpered and I crawled back to her.

We were alone, I kept thinking. I had no one left I could trust, except this baby that depended on me for everything. Panic pressed around me. I looked at the anchor lying a few feet away. I’d heard of people leaping from their boats tied to their anchors. But this wasn’t a possibility for me. It was as impossible as the water receding from the land and people standing up again where they’d fallen. Instead I took Pearl in my arms and climbed out from under the tarp into the morning sun.

I would carry him with me; he would still guide me. Grandfather was the person who taught me how to live; I wouldn’t fail him now. I wouldn’t fail Pearl, I told myself.

When I think of those days, of losing the people I’ve loved, I think of how my loneliness deepened, like being lowered into a well, water rising around me as I clawed at the stone walls, reaching for sunlight. How you get used to being at the bottom of a well. How you wouldn’t recognize a rope if it was thrown down to you.

CHAPTER 7 (#ulink_ce85e1cf-af16-5d7b-84d0-e2159f7c9773)