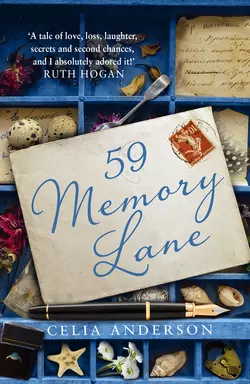

59 Memory Lane

Celia Anderson

‘A wonderfully warm and original story full of engaging characters. 59 Memory Lane is a tale of love, loss, laughter, secrets and second chances, and I absolutely adored it!’ – Ruth Hogan, bestselling author of The Keeper of Lost ThingsMay Rosevere has reached the grand old age of one-hundred-and-ten, thanks to a slice of toast with butter every morning, a glass (or two) of sherry in the evening, and the wonders of the Cornish sea breeze – or so she tells everyone.But May has a secret. One that no one has ever discovered, not even her late husband Charles.A treasure trove of long-forgotten letters, just waiting to reveal their secrets, and frosty neighbour Julia are change everything…

Copyright (#u5c696aef-bbf8-5483-b853-bbe19d0e2f17)

Published by HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

First published in Great Britain by HarperCollins 2019

Copyright © Celia Anderson 2019

Cover design by Claire Ward © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2019

Cover photographs © Jane Morley/Trevillion Images (main image), Ebru Sidar/Trevillion Images (envelope); Johnny Ring Photography and Shutterstock.com (http://Shutterstock.com) (additional images)

Celia Anderson asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008305413

Ebook Edition © May 2019 ISBN: 9780008305420

Version: 2019-03-11

Dedication (#u5c696aef-bbf8-5483-b853-bbe19d0e2f17)

For Ray, my memory maker

Epigraph (#u5c696aef-bbf8-5483-b853-bbe19d0e2f17)

O thrilling sweet, my joy, when life was free

And all the paths led on from hawthorn-time

Across the carolling meadows into June.

‘Memory’ – Siegfried Sassoon

Love is knowing that even when you are alone, you will never be lonely again. And great happiness of life is the conviction that we are loved. Loved for ourselves. And even loved in spite of ourselves.

Les Misérables – Victor Hugo

Contents

Cover (#u761654e9-854a-512a-8632-61ddea916f78)

Title Page (#ubeaf0e89-48b3-5b2a-9c2d-17a15a98c85e)

Copyright

Dedication

Epigraph

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Chapter Nineteen

Chapter Twenty

Chapter Twenty-One

Chapter Twenty-Two

Chapter Twenty-Three

Chapter Twenty-Four

Chapter Twenty-Five

Chapter Twenty-Six

Chapter Twenty-Seven

Chapter Twenty-Eight

Chapter Twenty-Nine

Chapter Thirty

Chapter Thirty-One

Chapter Thirty-Two

Chapter Thirty-Three

Chapter Thirty-Four

Chapter Thirty-Five

Chapter Thirty-Six

Chapter Thirty-Seven

Chapter Thirty-Eight

Chapter Thirty-Nine

Chapter Forty

Chapter Forty-One

Chapter Forty-Two

Chapter Forty-Three

Chapter Forty-Four

Chapter Forty-Five

Chapter Forty-Six

Book Club Questions

A Q&A with Celia Anderson

Recipe: Spicy Fish Pie

Acknowledgements

About the Author

About the Publisher

Chapter One (#u5c696aef-bbf8-5483-b853-bbe19d0e2f17)

May Rosevere sits on the sun-warmed decking, watching the tide creep in. She does this most days if it’s convenient, but the trouble with tide times is that they will keep on changing. If it’s cold, May wraps herself in an ancient baby shawl to sit in her swing seat. The memories have faded from the wool, and the baby who wore it must be thirty by now, but it still makes her feel cosseted. She doesn’t need the shawl today. Summer is in the air and the garden around her granite cottage is looking green and lush.

A man with a neat grey beard wanders along the beach. Tristram, thinks May, waving her handkerchief. He doesn’t see her – his hat is pulled down over his ears and he’s too busy throwing a bright red ball into the sea to look up towards May’s place. The man’s black Labrador looks at him in disgust and ignores the ball. His smaller, biscuit-coloured dog isn’t any more enthusiastic, too busy digging in the sand. The sound of Tristram’s booming laugh carries through the still air and he plods on towards the stone jetty that marks the western edge of Pengelly Cove. May reaches for the diary she keeps by her side, turns to the page for 1 June and makes a note. That ball will probably be washed up later. It must have a whole lot of good memories buried inside it. Then reality hits, as it does several times a day. Her beach-combing days are over. Even if she happens to see it float in, she can’t get to it.

It’s only a couple of hundred yards from May’s back porch to the tideline, but the beach might as well be on the moon. Being a hundred and ten years old tends to limit your orbit. May’s shoulders slump. This is a crisis. For weeks she’s been feeling less and less lively, and she knows the reason why. Her memory supplies have completely dried up.

May looks down at the elderly cat curled up by her feet. ‘Well, Fossil, I’m just going to have to come up with a plan,’ she tells him.

The cat blinks its yellow eyes and says nothing. May doesn’t really expect a reply. Although she has certain abilities, talking to animals isn’t one of them.

‘I need a new source of memories,’ she continues. Fossil yawns, and sticks out the tip of his tongue. ‘There’s no need to be rude,’ May says. ‘This is serious. If I don’t find a way to … acquire more of my treasures, I’m stuffed, as Andy would say.’

Andy is May’s neighbour. His terraced house abuts her new home. May’s solid granite single-storey cottage at 59 Memory Lane was built to last. It was a tea shop up until last year and in its time has been extended to have five rooms plus a bathroom and a long conservatory with a stunning view of the bay. It’s too big for May really, but it’s private, and suits her well. There are any number of basking places for the days when it’s warm enough to sun-worship, a lawn around the house where the wooden benches and tables used to stand, and even a small car park that goes right up to the sea wall.

May rents the parking spaces out to a few selected villagers. She doesn’t need the money – the sale of her house up on The Level has left her very comfortably off – but she likes the comings and goings and the friendly chit-chat when people drop off their cars at the end of the day. Loneliness has rather taken her by surprise since she moved, and the car park activity is a welcome distraction. Living alone has its benefits but she sometimes tires of talking to the cat. When she lived in the heart of the village, May knew everything that was going on, and kept a close eye on her neighbours’ affairs by dint of popping in and out of their houses on a variety of pretexts and by getting involved in the social life of the local Methodist Church. You don’t have to believe in God to make salmon sandwiches and dispense weak tea.

May’s new home has weathered well, and looks as though it’s been there for ever, the newer sections blending in seamlessly, with ivy and wisteria covering the joins and close-growing shrubs hugging the walls. There is yellow lichen on the roof tiles and the door is painted almost the same colour. She has huge earthenware pots of succulents either side of the front step that take no looking after, and a quirky blue and yellow ceramic sign that spells out the name of the cottage in swirly letters – Shangri-La.

Andy gardens for May whenever he has time, and does a few hours’ routine office work for a local garden centre when his landscaping business allows or the weather is awful. His six-year-old daughter, Tamsin, lives next door with him. May stirs, and groans slightly as she hears the pounding of small footsteps approaching on the wooden floor of the deck.

‘Hello, May,’ says Tamsin in a loud stage whisper. ‘Have you finished your nap?’

‘I wasn’t asleep.’ May lets her glasses slide to the end of her nose so that she can peer at the child. She looks angelic. Dark curls frame a round, rosy-cheeked face and her eyes are huge and brown with long lashes. Anyone might think butter wouldn’t melt in her mouth, as May’s mum used to say. They’d be wrong.

Tamsin reaches the garden chair and slips her arm through May’s, head butting her shoulder. ‘I’ve done with school,’ she says.

‘For today,’ answers May, trying to look stern.

‘For ever and ever. It sucks,’ says Tamsin.

‘That’s not a very nice thing for a little girl to say.’

‘What, that school sucks, you mean? Summer says it.’

She sits down on the boards and leans against May’s legs. The pressure is comforting at first, but is soon painful. May grits her dentures. ‘Summer says quite a lot of things that you shouldn’t copy, it seems to me. Anyway, you can’t just stop going to school, Tam. You’ve only done a year so far. It goes on for a lot longer than that, as a rule.’

‘Dad can’t make me go,’ says the little girl, sticking out her bottom lip. Tamsin’s eyes are even darker than Andy’s, and she’s inherited the shaggy curls from him too. May knows there’s a regular morning battle to get a ponytail in place. She’s heard the screams. Tamsin’s already ditched her scrunchy for the day and her blue cardigan with the crest has disappeared as well, probably under a bush somewhere.

‘Why don’t you like school? Has something happened today? You were fine yesterday when you came round.’ May often keeps an eye on Tamsin until Andy comes home, if he’s not expecting to be long. She’s never been keen on children but this one is different. This one has a mind of her own.

‘It’s just boys,’ says Tamsin. ‘Why do we have to have boys?’

‘Well …’

‘They’re stinky, and they push in front of us when we line up.’

‘Hmm. But some girls push too, and boys often grow up to be grand men like your dad and Tristram, don’t they?’

‘S’pose so.’

The cat stands up, stretches, and makes his way over to Tamsin. His black fur is slightly dusty due to his habit of rolling in the flowerbeds. Tamsin looks at him doubtfully.

‘Dad said I mustn’t touch Fossil any more,’ she says.

‘Did he? When was that?’

‘Yesterday. I kept sneezing, and he said it was either hay fever or cats. Like my mum used to get, he said. But I love Fossil. He doesn’t even smell that bad today, does he? Not like boys do.’

May thinks Tamsin might be going to cry. Tears are May’s least favourite thing. An idea strikes her as she sees a red dot appear on the shoreline. ‘Would you do a little job for me, my bird?’ she says, in what she hopes is a winning tone.

Tamsin frowns even harder. ‘What do I get?’

‘Get? You don’t get anything. Young people are supposed to help older ones. Don’t they teach you anything at school?’

Tamsin shrugs.

‘Would you just pop down to the beach and pick up that ball over there?’

‘But it’ll be all wet and slimy. Why do you want a ball, May? You haven’t got a dog and Fossil doesn’t play with stuff any more.’

‘Well … I …’ May tries to think of a plausible answer but her mind has gone blank. There’s no easy way to say that the reason she’s managed to live to a hundred and ten is that she has been appropriating her neighbours’ memories for years. She’s always told herself it’s a form of borrowing, but that’s not true, because once she’s got them, she’s never quite worked out how to give them back.

Now that she’s living at the bottom of Memory Lane and can’t visit people in the village any more, May has no way of collecting their treasured objects so that she can do what she terms her thought harvesting. But she couldn’t stay in that rambling old family house once her legs started to get creaky. She was lucky to be able to keep it going for so long. Leaving Seagulls was hard, but this cottage is so much easier to live in, apart from the sad lack of new memory sources. The vibrations from her collecting missions have fed her mentally for a long time now, but she’s bled them all dry.

Tamsin prods May gently, still waiting for an answer. She’s right, in a way. A soggy toy won’t do much good. But at least it’ll have something inside it – some scrap of love and dog-type warmth buried in its depths. And May is desperate.

‘Just for me, poppet, please?’ she says, putting her head on one side and smiling in what she hopes is a sweet old lady way.

Tamsin shrugs again then potters off down the path, over the last of the cobblestones and onto the shingle at the top of the beach. When she reaches the sand, she slips off her shoes and socks and begins to twirl and bounce towards the lapping waves. Her solid little body is transformed when she dances, making her almost fairy-like. May watches. The child knows the beach completely and she wouldn’t stray far from sight anyway. There’s no need to worry, even if May was the worrying kind. She never has been until now. But unless she can find a new bank of memories, May won’t reach the fabulous age of one hundred and eleven. It’s been her dream to reach that milestone ever since childhood. All those lovely ones in a row, like a strong gate: 111. Her father, gazing at a particularly wonderful sunset over the bay, once exclaimed, ‘If I live until I’m a hundred and eleven I’ll never see anything as splendid as that sight.’ Why that number? May thought, but the idea stuck, like a lucky charm.

After a few minutes, Tamsin hops back into the garden and drops the ball on May’s knee.

‘It’s yucky,’ she says, pulling a face. ‘Told you it would be. Have you got any cake?’

May gestures towards the open kitchen door, and as Tamsin skips away (does that child ever walk anywhere?) she conquers her revulsion and clutches the ball tightly to her chest. But even squeezing it hard with both hands and her eyes tight shut doesn’t release more than a tiny buzz of memory, and that seems to be mainly a dog’s woolly thoughts about his dinner.

It’s no good. I’m done for, thinks May, throwing the ball as hard as she can towards the shrubbery.

‘May, why did you go and do that? I fetched it specially.’ Tamsin appears with a large plate containing four slabs of angel cake and a bag of Maltesers.

‘You were right, dear. It was very slimy,’ says May, sadly.

Tamsin looks up as she hears the click of the latch on the front gate next door. ‘Dad’s home,’ she says. ‘I’ll go and get him to make us a nice hot drink, shall I?’

She’s back in five minutes or so, followed by a long, lean man with a serious expression. May wishes he’d smile more, but she supposes he’s had a lot to make him melancholy since his wife died. Andy is an out-in-all-weathers kind of person, pure Cornish from head to toe. Tanned and healthy-looking, he’s wearing faded denim shorts, heavy boots and a checked shirt with the sleeves rolled up – his usual gardener’s uniform. He’s very grubby. May looks at his well-muscled legs and forearms approvingly. Even at one hundred and ten she can still appreciate a vision like this.

Andy puts a mug down next to May and hands Tamsin a glass of warm blackcurrant juice.

‘Oh, bless you, love. Aren’t you having one with us?’

‘No time. Tam needs to get ready for a birthday party. It starts in half an hour but she looks as if she needs a good wash first.’

Tamsin moans to herself and slurps her drink, spilling some of it down her front, then lies down again next to May, adding some soil to the stains on her school skirt.

‘Where have you been today?’ May asks. ‘You look as if you’ve been working hard.’

‘Just across the road at number sixty, trying to get Julia’s place straight,’ he says. ‘It’s gone wild since Don died.’

‘It was bound to, really. Julia doesn’t like gardening, does she? Probably hasn’t got the right clothes,’ May sniffs. She has no time for Julia Lovell, even though she’s known her for many years and often shared the church kitchen with her when they were drafted in to cater for village events. Keeps herself to herself, that one, May thinks. Pretty much everybody knows what it’s like to lose somebody but we don’t all turn reclusive, do we? Drama queen. And why does she always have to be so dressed up? Her hair can’t be natural. There’s not a single grey hair amongst all that black. And straight as a die. Never bothers with curlers. Well, I suppose there’s not enough of it to curl.

‘Maybe not. I used to go round every few weeks and give Don a hand when he got past doing the rough digging and so on,’ says Andy, ‘but she hasn’t felt like bothering with it lately.’

‘No. She wouldn’t.’

‘What have you got against the poor woman? She always asks after you.’

‘Oh, you don’t want to hear me harping on about old grudges. Water under the bridge. I just wish she wouldn’t pretend to like me, that’s all.’

‘I don’t think Julia’s got anything against you, May.’

‘Ha! Why does she give me those frosty looks then?’

‘You’re imagining it.’

‘Whatever,’ says May. She’s learned that one from Tamsin and it comes in handy.

Andy laughs. ‘Anyway, you’ll never guess what Julia’s found today.’

May looks at her neighbour without much interest and raises her eyebrows. He carries on. ‘When she was clearing out Don’s den …’

‘His old shed, you mean?’

‘Well, yes, OK – his shed … she found a massive sack of letters.’

Tamsin rolls over onto her back and stares at her dad. ‘Why did the man over the road have a sack of lettuce?’ she mumbles, through the last of the cake.

‘Don’t talk with your mouth full, sweetheart,’ Andy says, ‘and I said letters.’

‘Oh.’ Tamsin doesn’t much care for things you have to read so she crawls under a nearby bush to make a hide-out, but May is all ears.

‘Letters to whom?’ she says. No need to let the grammar slip.

‘Not to whom, more like from whom. He hoarded every single thing his family in the Midlands ever wrote to the two of them. They’re incredible. Julia showed me a few.’

May digests this information in silence. Her heart is fluttering now. She hopes she isn’t going to have some sort of seizure and pop her clogs just when hope is at hand.

‘May? What’s the matter? You look a bit wobbly today,’ Andy says.

May stares out to sea, as the tide turns and the gulls wheel and cry. A sackful of memories, there for the taking. But however is she going to get her hands on them?

Chapter Two (#u5c696aef-bbf8-5483-b853-bbe19d0e2f17)

… so the opal ring’s definitely missing. I don’t know what to do, Don. Mother’s blaming each of us in turn and we’ve turned the house upside down looking for it. Nothing.

Putting down the letter in her hand for a moment, Julia gazes out of the window, past the trailing clematis that climbs over the remains of an oak tree, and the wisteria taking over the shed roof, trailing its feathery lilac fronds so low every summer that Don had to stoop under it every time he retreated there.

What possessed Don to keep all these letters, and what in heaven’s name is she meant to do with them now he’s gone? If she hadn’t finally made herself go into his den she’d have still been in blissful ignorance of the contents of the wooden chest.

She remembers the day he rediscovered the disgusting old chest. She was mystified as to why anyone would want to keep such a thing.

‘You do know that piece of junk’s riddled with woodworm?’ she said, as he dragged it across the yard from the garage. ‘I was going to put it out ready for Andy to take to the tip, or to sling on his next bonfire.’

‘Not infested any more, love,’ Don said, straightening up and rubbing his back. ‘Didn’t you see me out here yesterday with that can of stuff I found in the cupboard under the stairs? I’ve zapped the little devils. Those worms are history!’ He laughed joyfully and patted the oak chest as if it were a faithful dog.

‘But what are you going to do with it?’ Julia asked. ‘It smells disgusting.’ She wrinkled her nose at the eye-watering chemical fumes still coming from the wood.

‘It’ll cancel out the stink of my pipe tobacco then. I’m having a sort out in the den. The drawers in my desk are stuffed. I can’t even open them properly. This’ll be perfect to store everything in.’

‘Wouldn’t it be better to throw something away?’ Julia knew she was wasting her breath as she said this. Don didn’t believe in getting rid of anything unless he had absolutely no choice.

Julia’s eyes prickle again as she conjures up the smile he gave her as he struggled on towards the shed with his prize. The oak chest left deep scuff marks on the path. She can still see them if she looks closely. As he heaved it through the door, he cheered and gave her a victory salute.

If only she’d taken a photograph of that moment. Such a charmer, was that man, but somehow so innocent with it. Their granddaughter, Emily, has the same wide blue eyes and twinkly smile.

With a pang, Julia wishes Emily were here, and not working abroad. New York is much too far away. These thoughts of Don are unbearably sad to cope with on her own. How is she going to get through the rest of her days without him?

Sighing, Julia forces herself to pick up the letter again. Don kept every bit of correspondence they ever received, it seems, and never bothered to sort them into any kind of order. This one is from the younger of his two sisters, Elsie. Like most of the family, Elsie adored the Cornish village where Don and Julia made their home, and visited it regularly. Ever since Julia married Don back in the spring of 1959, when he was fresh from the air force and so handsome he could have had his pick of any girl around, her summers were spoken for. She spent them changing beds, washing sheets, planning menus and thinking up suggestions for trips so the guests might take themselves off to give her a few hours of the solitude that she craved.

She didn’t mind the visitors coming. Well, not much. Don was so hospitable she’d have felt mean to say she needed a break. Anyway, in those days they had their old caravan down the coast to escape to when the season was over. And boy, they certainly enjoyed being alone again. Julia blushes at the memories. She reads on, rubbing her tired eyes as Elsie’s voice speaks to her down the years.

Anyway, other than the crisis with the ring, my most important news is that I’ve managed to change my holiday week, and so has Kathryn. Will can’t come with us this time but he sends his love. He’s been a bit peaky lately, moping around like a dog that’s lost its bone. I wish he’d get himself a girlfriend. Mother thinks he’s just waiting for the right one to come along.

Never in a month of Sundays, thinks Julia. Don’s younger brother, Will, wasn’t remotely interested in finding a girl, and now he’s a retired priest in the wilds of County Kerry. The baby of the family, Will has an ethereal charm, but a large part of his charisma is his fun-loving impulsiveness. Moping around sounds unlike him, although he sometimes was annoyingly moody. Julia casts her mind back. The ancient ink, almost invisible in places, brings that summer vividly to mind.

Elsie and Kathryn tottered off the train as dawn broke, crumpled and sticky but wildly excited at the thought of their week in Cornwall. Julia, heavily pregnant with Felix, plastered on her best welcoming smile. Oh God, here we go again, she thought. Sometimes she felt like the owner of a rather cramped B&B instead of a woman with a new and very large extended family who all loved the seaside. The big double bed had only just been changed after her mother- and father-in-law’s visit. It was good that Don’s sisters never minded sharing a bed – it meant less laundry, and they’d only be in and out of each other’s rooms half the night if not. They never seemed to stop talking, those two. The whole family was the same. What did they find to say? Julia wonders. Did they never just simply run out of words?

She rereads the last line. What was it that was bothering Will that time? Julia vaguely remembers the youngest of the family being paler than usual on his next visit, but nothing was ever said. To be fair, Julia’s thoughts were preoccupied with her own exhaustion and how she was going to cope with a newborn when she’d never even changed a nappy before. Will was almost fragile in looks – a beautiful blond boy, with high cheekbones and such narrow hips that he always had to wear braces to stop his trousers ending up around his ankles. Kathryn and Elsie were much tougher cookies.

She drops the letter and picks up another one. Elsie again, rattling on from earlier the same year, that January so long ago. Julia just began to suspect she was having a baby around then. She was twenty-six by that time, but so ridiculously naïve that she had to ask her neighbour to reassure her that the signs she noticed weren’t the beginnings of some horrible disease. She longed for her mother, or some other homely body to run to, but her parents had decided to settle in India after her father’s retirement from the army. Don had just started his new job, and they scraped together enough cash for the deposit on 60 Memory Lane. It was a shabby place – borderline derelict in parts – but they fell in love with it. The pregnancy wasn’t expected. Neither of them had much idea about family planning.

Elsie’s letter is starting to put together a picture in Julia’s mind. She reads on.

Well, you’ll be pleased to hear that Mother has finally come around to your way of thinking, and her precious opal engagement ring is going to be passed to Julia. I expect you’re right and I hope it brings her luck, as it has for Mother and Grandma, or so they insist. I’d have loved to have it, of course I would, and so would Kathryn, but with two sisters, I guess there had to be a fair way. Even Will has had his eye on it but I don’t know who he’s planning to give it to! Still no girl on the scene.

Reading about that ring has stirred up feelings she would rather have left buried. Don, usually the least cynical of men, was very suspicious about its disappearance, just when it was about to be delivered to him for his new wife.

Ruffled, Julia shakes herself and flexes stiff shoulders. She’s been sitting still too long. It’s time for a cup of tea and maybe a piece of the fruitcake she’s made from her mother’s favourite recipe. She doesn’t bake much nowadays because she has to go by instinct. She’s had to ever since the old cookery book, handwritten and full of the neat, sloping writing Julia loved, disappeared a couple of years ago. She’s searched high and low but it’s never turned up. Good job she’s still got her marbles at eighty-five, and can remember a handful of the best recipes, although the sticky lemon cake has never turned out quite the same without the book to guide her.

The door knocker clatters, followed almost immediately by the bell ringing. Julia mutters under her breath, words her mother definitely wouldn’t have approved of. She gets to her feet and makes her way to the front door, still grumbling. It’s no good pretending she isn’t at home. The trademark knock and ring tells her that the woman out there won’t give up easily.

‘Hello, Julia,’ says Ida, as Julia opens the door. ‘I hope I’m not interrupting your tea?’

Julia forces her mouth into something resembling a smile. Ida Carnell, standing sturdily on the step, has an in-built radar for the moment when the kettle is going to be switched on and the cake tin’s about to appear.

‘No, of course not, Ida,’ she says. ‘Come in and join me for a cuppa.’

‘Oh, well, so long as I’m not being a bother.’

Ida follows Julia to the kitchen, talking all the way. Really, thinks Julia wearily, this woman is almost as bad as Elsie and Kathryn in their heyday. Granted, Ida’s a pillar of the local Methodist Church and has got a heart of … well, if not pure gold, something fairly close, but does she ever shut up?

‘… and so I didn’t think you’d mind me calling on you. It’s very important. I’ve got a favour to ask. It’s about my new plan.’

Oh, no. The last time Ida had a plan, Julia had been roped into making scones for a hundred and fifty people. Not another fund-raising tea … oh, please not? But Ida is still talking.

‘Have you heard of the Adopt-a-Granny scheme? A lot of local churches are trialling it, since we had a memo from Age UK reminding us how many old people are lonely and housebound.’

A cold feeling creeps up Julia’s spine. She’s got a hunch she won’t like this, whatever it is.

‘No? I thought you might have seen my article in the parish magazine? Anyway, I’ve made a list.’ Ida gets out a large ring-bound notepad and a pen. ‘Can I put you down for May?’

‘Why? What happened in May? It’s June already; I think last month passed me by.’

‘No, I didn’t mean that. Your neighbour, May. At number fifty-nine? Shangri-La? I’m really worried about her.’

‘You want me to adopt May? As my granny?’

Ida laughs. ‘Not exactly. She’s only about twenty years older than you, isn’t she?’

‘Twenty-five, actually,’ snaps Julia. This is ridiculous. Is the woman insane? Why would Julia need a granny? And if she did, how could May ever be a likely candidate for the job?

‘Well, age is only a number, as they say, and I know Andy’s been worried that May can’t get out of the house now. Julia, the thing that really bothered me – well, it doesn’t sound much when you say it out loud, I suppose – it’s just that when I came down to fetch my car yesterday, she was just staring out to sea.’

‘Ida, lots of people like looking at the sea. I do myself. It’s very relaxing watching the waves. That doesn’t mean she needs adopting.’

Ida frowns. ‘I knew it was going to sound silly. I don’t use my car all that often but the other day when I called to get it to go to Truro she was doing exactly the same thing. Sitting on the decking just … staring … with such a sad look on her face.’

‘I still don’t think—’

‘And then as soon as she saw me both times, she started to chat about the weather, as if she’d been dying for somebody to talk to. May’s never been one for small talk. You know that as well as I do.’

‘But …’

Ida holds up a hand. ‘Yes, yes, I know you two have got history, as they say. An even better reason for you to get together over a nice cup of tea and let bygones be bygones.’

‘You think so?’

‘I do wish you wouldn’t purse your lips like that, Julia. You remind me of my mother, and she could be quite terrifying at times. It’s for a good cause. The scheme’s going well so far.’

‘Is it really?’

‘Oh, yes. You’d be surprised how many people in the village need a bit of company, but will they ask? No, they won’t. Too proud, or something … So, the story so far is that Vera from the shop’s adopted that nice old lady from Tamerisk Avenue. You know – Marigold – the one with the mobility scooter and the smelly Pekinese that rides in the basket?’

‘But Marigold’s got six children and any number of grandchildren.’

‘And when was the last time you saw any of them in the village? They only turn up when they want to cadge money off her. She barely sees a soul from one week to the next.’

‘I don’t think—’

‘And George and Cliff have really come up trumps. They’ve taken two for me. Joyce Chippendale, the retired teacher who’s registered blind, and the old boy from the last fisherman’s cottage on the harbour?’

‘Old boy? You surely don’t mean Tom King? He’s younger than me. He must only be in his late seventies.’

‘Well, yes, but he doesn’t get out much since he retired. Being a psychiatrist all those years took all his time up so he hasn’t really got any hobbies, and he looks as if he could do with a square meal. George is going to bring them both over for lunch or dinner at their restaurant a couple of times a week.’

‘How kind.’ Julia shivers. She knows this cannot end well.

‘I want to get other villages involved if this takes off. It’s a huge problem, Julia.’

‘What is?’

‘Loneliness, dear. But listen to me being tactless; I don’t need to tell you that, do I?’

Julia gives Ida one of her special looks, the kind she used to use to quell unruly Sunday school children years ago. ‘And what’s that supposed to mean?’

‘Well, with you losing Don, and everything. You must be lonely nowadays … with your family so far away …’ Ida’s voice trails off as she finally senses Julia’s icy disapproval.

‘Missing somebody isn’t the same thing as being lonely, Ida,’ says Julia, making a valiant attempt not to punch the interfering old busybody. Violence isn’t her thing, but she’s never felt more like doing somebody a damage. The cheek of the woman! Ida’s only about sixty and she’s still got a perfectly healthy husband, even if he is a bit dull. Who is Ida to make judgements about Julia’s needs?

Ida falls silent for a moment and then rallies. ‘Yes, you’re probably right. No offence meant, and none taken, I hope?’

‘Perish the thought.’

‘Oh, good. I’m going to ask Tristram to join the scheme next. If George and Cliff are doing it, he’ll not be able to resist. The two main fish eateries round here – Cockleshell Bay and Tris’s Shellfish Shack – both giving away meals for charity? It’s a great story. I’ll get the local paper onto it as soon as it’s really up and running. But first I’m going to call a meeting for us all.’

Julia waits, holding her breath. Sure enough, here comes the blow.

‘So, anyway, I thought Andy could bring May over tomorrow? About tea time?’

The words ‘Resistance is useless’ spring to mind. Whatever Julia says, Ida will steamroller over her. She squares her shoulders. No, she mustn’t be browbeaten. Ida can’t make her invite May over to visit, can she? It’s Julia’s house and she just won’t allow it.

‘I can’t have visitors at the moment,’ she says. ‘It’s completely out of the question. I’m sorry, but you’ll have to find someone else.’

Ida leans forward and looks into Julia’s eyes earnestly. Her chins are quivering with emotion. ‘But, Julia, don’t you think it’s our duty to do what we can for one another?’

‘Well, yes, but—’

‘That’s settled then. I’ll go and see May as soon as I leave here and let her know. She’ll be thrilled to bits, I’m sure. Tomorrow it is!’

Julia opens her mouth to argue again and then decides it’s pointless.

‘Are you rushing off to see May immediately?’ she asks.

‘Not when you’ve gone to the trouble of putting the kettle on for me. And isn’t that your famous fruitcake I see there? May will enjoy a slice of that tomorrow, too.’

‘If she comes.’

‘But why wouldn’t she? I’m sure May will be delighted to get out of the house and have a lovely chat with you.’

Julia says nothing. There are one or two excellent reasons why May might avoid visiting 60 Memory Lane, but she’s not about to share them with Ida.

Chapter Three (#u5c696aef-bbf8-5483-b853-bbe19d0e2f17)

Across the road half an hour later, May glares at Ida as her visitor takes the last chocolate biscuit from the plate that Tamsin fetched from the larder. Andy has taken his daughter home now – he escaped as soon as he made the two ladies a fresh pot of tea.

‘I really shouldn’t,’ says Ida, munching happily, ‘because I’ve just started going to that slimming group in the village hall and it was all going so well until I had to eat some of your lovely neighbour’s fruitcake.’

‘Lovely neighbour? Which one’s that then?’

‘Now, now. You know very well who I mean. Julia sends her love.’

‘Really?’ May frowns. It doesn’t sound likely. Sending love to May wouldn’t be on that one’s priority list. After the incident with the missing soup spoons, they’ve never been more than civil. The very cheek of the woman, insinuating that May had pinched a whole bunch of tatty cutlery. She’d had enough trouble pocketing the sugar tongs. Of course, the real damage was done while Charles was still alive. Julia never liked May’s husband. Not many people did, come to think of it.

Ida’s eyes are shining with goodwill. She’s always had this annoying habit of thinking everyone should be fond of each other just because they live in the same village, thinks May. Most of them do get on, but May prefers to choose her friends for herself.

‘Yes, of course she sent her love – why wouldn’t she? Julia speaks very highly of you.’

‘She does?’

‘Not only that, but she’s asked me to see if you’d like to pop over there for a visit tomorrow.’

‘Are you pulling my leg, Ida? Why would Julia suddenly want me to go and see her? We haven’t spoken a word to each other since Don’s funeral, and that was only in passing. Anyway, I don’t get out of the house on my own these days. I’d end up flat on my face on the cobblestones.’

Ida smiles. There’s something of the shark about her when she’s got an idea in her head. ‘That won’t be a problem. I’m sure Andy will take you across the road when he finishes work.’

‘But—’

‘Now, there’s no need to worry. He’s working in my own garden tomorrow, as luck would have it, so I can make sure he gets home in good time. Julia’s expecting you at half-past five. And if you’re lucky, she might show you some of her treasure trove. I’ve never seen so many old letters in my life.’

May is silent. Of course! Why hadn’t she thought of this before? She should have snapped Ida’s hand off straight away. Those letters. All the memories just waiting for her. Can it be that her prayers have been answered? She’s never been sure about God, but it doesn’t hurt to hedge your bets, and she always likes to send up a few requests while she’s listening to the Sunday morning hymns on the radio.

Some of the words to the hymns are quite poetic, and she sings along with gusto. Her favourite is the wedding one. She likes the lines:

Grant them the joy which brightens earthly sorrow,

Grant them the peace which calms all earthly strife.

It paints such a lovely picture of marriage. Hers wasn’t at all like that, especially after May found Charles in bed in the middle of the morning with the baker’s delivery boy, if you could call a strapping nineteen-year-old a boy, but there’s no need to be cynical about the institution in general.

She rustles up a big smile for Ida. ‘Well, it sounds as if you’ve got it all sewn up,’ she says. ‘But I still can’t see why Julia would choose to invite me over? In truth, Andy told me he was anxious because she wasn’t seeing anyone at the moment. She’s turned into a bit of a hermit.’

‘I know, and it’s been a worry to us all. She hasn’t been to the morning service for months. She’s taken Don’s death very hard. They were true soul mates, weren’t they?’

May presses her lips together. She’s always hated that expression. As if souls could talk. If that was the case, there’d be a lot fewer arguments and misunderstandings in the world. Her own husband wasn’t so much of a soul mate as a pain in the backside, especially in the later days, when he had dark suspicions about his health issues. If only he’d had the sense to see the doctor. After Charles died she began to appreciate his finer points again, but while he was with her the temptation to smother him was sometimes almost irresistible, the awkward sod. Pedantic, waspish and far too fond of flower arranging.

Ida’s peering around the room now. Nosy old bat. ‘You’ve got some lovely ornaments and pictures,’ she says. ‘It’s hard to imagine how anything can be around so long and yet still be so perfect.’

‘Like me,’ says May, with a cackle.

Ida smiles. ‘You’re absolutely right. Everyone always says how young you look, May. How do you do it? What’s your secret? Do you use some sort of fancy face cream?’

‘You must be joking,’ says May. ‘I wouldn’t spend good money on that muck. No, my looks are down to a small daily dose of port and brandy, plenty of heathy food and clean living, that’s all.’

May has trotted this mantra out so often that she might almost believe it if she didn’t know the truth. When she first realised that it was possible to pick up vibrations from certain objects, or whatever she liked to call the effect that she got, May was young enough to think that all children got a sparkly feeling of wellbeing when they touched things that had an interesting past. It took quite a while to match her magical moments to the treasures she sometimes managed to collect by trawling the local jumble sales and junk shops with her mother.

Pocket money didn’t go far when you were an avid collector, but her father seemed to understand her needs better than her mother, and if he took her out shopping he would indulge her by slipping a bit of extra cash into her pocket at vital moments. And when May realised how many people in the village had memories hidden away in their possessions, the harvesting really began to move into gear. A special, secret sort of magic, that’s what it is, and it needs to stay that way.

She remembers the first time she was overcome by the feeling that she must have something precious that didn’t belong to her, even though, at ten years old, she knew very well it was wrong. May’s mother took her to their nearest neighbour’s house for tea, and while the two ladies were busy in the kitchen May spied a tiny enamelled box with a tightly fitting lid. She picked it up and cradled it in the palm of her hand. Patterned with purple violets, the box seemed to hum to itself, as if it had secrets that only May could hear.

May prised off the lid with a fingernail, all the while listening in case the grown-ups came back. Inside was a curl of hair, soft and blond. May held her breath and put her finger into the middle of the hair. The warmth and energy that flowed from it was so dramatic that she withdrew her hand with a gasp. After a moment, she tried again, preparing herself this time. Bliss. Glancing over her shoulder, May slid the curl into her pocket, then closed the lid and returned the box just as her mother reappeared carrying a plate of fairy cakes.

Since that day, there have been many other chances to find what she needs, but May has had to be careful. Now and again she’s come very close to being caught.

Unaware of the unsettling thoughts racing through May’s mind, Ida checks her watch and gets to her feet, accidentally treading on Fossil, who hisses his disapproval and runs for the cat flap. ‘Whoops! Sorry, cat. So that’s settled then. Andy can fetch you as soon as he’s finished at mine. I’m very excited about this new scheme, May. It’s going to benefit so many people. Poor Julia is so lost nowadays, and you’ll get a lot out of it, too.’

‘Oh, yes, I do hope so,’ says May.

A tiny bubble of excitement shivers inside her. She’d better take her largest handbag when she goes across the road tomorrow.

Chapter Four (#u5c696aef-bbf8-5483-b853-bbe19d0e2f17)

Andy calls for May the next afternoon on the dot of half-past five. She is wearing her best dress, which is cornflower-blue, and a pair of low-heeled court shoes in honour of the occasion. She’s not about to let Julia think she’s gone to seed while she’s been stuck in the house. The dress is sprigged with tiny buttercups and daisies. It makes May think of the rolling meadow behind her old home up the hill. She sighs. Oh, well, no point in looking over her shoulder – a beach on your doorstep is worth a dozen grassy fields and woods, after all. You couldn’t see the sea properly from the big house even though it was high up on The Level because the trees in between blocked the view.

Andy gives an impressive wolf whistle when he sees her. ‘Blimey, May. You still scrub up well. You don’t look a day over seventy.’

She bats him with her handbag and turns to the hall mirror to tidy her already immaculate hair. She’s always been glad that when the rich auburn of her hair eventually began to fade, it turned a beautiful snowy white. May misses being a foxy redhead sometimes, but her hairdresser thinks she’s very glamorous and calls every Monday to wash and set May’s curls in the usual bouffant waves. No blow-drying for May – she sticks to her faithful sponge rollers. A hefty squirt of hairspray and she’s ready for the week. The style hasn’t changed for years – why should it?

‘Pass me my lipstick, please, Andy. It’s on the side there. And the perfume. You can’t go wrong with Je Reviens, I always say. Thank you. Don’t want to let the side down, do I?’

He laughs, and offers May his arm as they head out of the door and down the uneven steps. She holds on tightly to Andy as they go over the cobbles, wobbling on the unfamiliar heels, and breathes a sigh of relief when they’re safely on the other side of the narrow lane. The breeze is fresher today, and May can see several small boats bobbing around near the harbour over to the right of the beach. There’s a strong smell of salt and seaweed in the air, and her heart lifts. It’s good to be outside and going somewhere for a change. The garden’s all well and good, but May misses being in the thick of things.

‘Come on then, May,’ says Andy. ‘We’d better not keep Julia waiting any longer. I usually go around the back and let myself in, but we’ll do it the proper way today as this is a special occasion.’

May rolls her eyes but makes no comment. Julia opens the door almost before they’ve rung the bell.

‘Hello, May. It’s good to see you,’ she says, but her smile doesn’t reach her eyes, and May isn’t fooled.

Andy helps May inside and Julia pushes a high-backed chair forward so that May can lower herself to a sitting position using the chair’s arms to support her. As May glances up, cursing herself for this new sign of weakness, she sees a look of pity on Julia’s carefully made-up face. May seethes inside but puts on her best party expression. There’s a lot to play for here.

Julia’s wearing an elegant grey shift dress, beautifully cut but rather grim, with a single string of pearls to finish the look. Well, her neighbour’s gone to the trouble of smartening herself up as usual, thinks May, but her blood boils at the realisation that Julia is feeling sorry for her. She’s filled with an even stronger resolve to get hold of at least one of Julia’s letters today. If she can soak up even a few memories, she’ll begin to feel better again. It’s been too long.

‘I’ll get going then, girls,’ says Andy. ‘Tamsin’s at Rainbows up at the church hall and I need to pick her up soon and get her home for tea. See you later.’

‘Bye, love,’ says May, taking the opportunity to look round the room as her neighbour sees him out. There are a few heaps of letters on the table. She must have interrupted Julia in her sorting. Good.

‘So, a cup of tea, May? I’ve made some scones for us,’ says Julia, coming back in. It’s a spacious, light room, with a dining table at one end and French windows opening onto a view of the other end of the cove. May can’t see this part of the world from her windows, and it’s a refreshing change to look out towards Tristram’s long, low bungalow and restaurant on the headland. It’s a while since she’s had the chance to eat at The Shellfish Shack.

Tristram’s an old friend and an attentive host, and the food there is sublime. May wonders how much a return trip in a taxi would be. It doesn’t seem long since she was able to walk there from her old home. But as soon as she gets hold of some new memories, her energy will come flooding back. There’s no time to lose. The alternative doesn’t bear thinking about.

Julia pushes the letters out of the way to make room on the table for their afternoon tea before she bustles off to the kitchen. ‘Jam and cream on your scone, May?’ she calls.

‘Yes, please. Jam first, obviously. Is it your own?’

‘Oh, yes. The last of the blackberry jelly from last year. Don loved it.’

There’s a silence as May remembers Don’s boyish glee whenever he was offered anything sweet to eat. Julia isn’t clattering around the kitchen any more, although May can hear the kettle boiling. Maybe she’s blubbing in there. May wonders if she should go in and offer some sort of comfort but she’s never been very good at hugging and so forth, and anyway, Julia would probably dig her in the ribs or poke her in the eye if she attempted anything like that. While she’s trying to decide what to do, Julia comes back in with a loaded tray. Her eyes are a bit pink but there’s no sign of tears. May heaves a sigh of relief.

They sit and eat their scones in silence for a few moments. ‘You haven’t lost your touch, dear,’ says May, reaching for a paper napkin to wipe away the last crumbs.

‘I haven’t made much cake of any sort since … well, you know. It’s no fun baking for yourself, is it?’

‘Haven’t you had your family over to see you, then?’ May doesn’t really need to ask this as she knows Felix and Emily haven’t visited lately. She’s more than aware of any comings and goings around her new neighbours’ houses. There’s nothing else to do these days but people-watch, so she’s sure Julia’s son and granddaughter haven’t been near the place since Don’s funeral last November.

Julia sits up straighter. She drinks her tea and seems to be searching for the right words. ‘They’re very busy,’ she says, ‘and of course Emily’s still working in New York, so she doesn’t get over here very often. Her mother has settled somewhere beyond Munich, out in the sticks, you know. She was always banging on about going back to her homeland, so Emily has to put visiting Gabriella at the top of her list when she gets time off. They booked tickets for me to fly over to Germany for Christmas but I had to cry off at the last moment … sadly.’

‘What a shame.’ May heard this news from Andy at the time and remembers that Julia was ill, although Andy wasn’t convinced that a slight chill should have made her miss all the festivities. May suspects that Julia’s feelings about family Christmases are as lukewarm as her own.

‘And Felix?’ May probes. She’s been wondering if the old feud is still simmering. Felix’s wife managed to cause quite a rift between her husband and his parents, before she upped and left with the owner of a Bavarian Biergarten, and even the mention of Gabriella’s name has put a chill in the air.

Julia shrugs. ‘He’s still based in Boston but he travels all over the world. Business is booming, as they say. I expect he’ll be here soon. It’s my birthday at the end of next month.’

Julia’s eyes fill with tears and May’s heart sinks. She remembers the loneliness of birthdays after Charles died. He wasn’t very good at presents and fuss, but at least he always took her out for a decent pub lunch at the Eel and Lobster on the green. Charles loved a nice plate of scampi and chips, and May always went for a home-made pasty with heaps of buttery mashed potato. It’s well over fifty years since May’s husband went voyaging and didn’t come back. There were whispers of suicide amongst the villagers but the official view was accidental death, due to the storm that suddenly whipped up. Eventually, the remains of Charles’s boat were found near to the harbour and his body was washed up on the next tide after that.

Charles was much too experienced a sailor to make such an obvious error of judgement; everyone who knew him must have been aware of that fact. He was many things, but reckless wasn’t one of them. Although May was surprised at the verdict, she held her tongue. It was easier that way.

May let the dust settle after the inquest and kept a low profile for a while. Life without Charles seemed strange, but soon became the norm. They didn’t marry until they were in their forties, soon after May’s parents died. At the time May felt unusually lost, cut adrift from her comfortable routine, and moving Charles in seemed like a logical step for them both. They had been together for only eleven years when the tragedy happened so May’s used to being alone now, but she can see that Julia has got a long way to go before she reaches that sort of self-sufficiency.

‘Come on, don’t cry,’ says May, patting Julia’s hand awkwardly. ‘You had a good life with Don. Nothing lasts for ever in this world.’ Or does it? she thinks. Maybe if I can get more memories, it might.

Julia is looking at May with deep loathing now and she realises she’s said the wrong thing.

‘That’s not the point,’ Julia mutters.

‘Well, it is really, dear,’ says May, pulling a face and reaching for her teacup, ‘but with hindsight I can see why today might not be a good day to say it.’

Julia’s mouth twitches, and then she laughs long and hard – a great guffaw that’s most unlike her. ‘Oh, May – you’re a real one-off,’ she says, wiping her eyes.

The sudden connection between them doesn’t last for more than a few seconds but after that, the time passes quickly. They talk about their neighbours’ foibles and the arguments at the stark grey Methodist Church about the new minister’s penchant for long sermons and soppy new hymns, and it’s not until Andy knocks on the back door to announce his arrival that May realises she hasn’t even tried to smuggle a letter into her handbag.

Julia goes to the kitchen to meet Andy, and May stands up, swaying slightly. If she leans over, she can reach the pile on the table. She holds onto her chair back with one hand and takes an envelope at random, slipping it into her handbag. It feels like a good one – quite thick, and there’s a buzz just from holding it. Her heart flutters. She thinks about taking a second letter but the voices are coming closer. She zips up her bag just in time, as Julia and Andy come in, followed by Tamsin, still wearing her Rainbow uniform.

‘All talked out, ladies?’ Andy asks. ‘Ready for the off, May? Tamsin needs her bath; they’ve been clay modelling tonight, and she’s a bit grimy. And she’s wearing most of her tea. It was spaghetti. I think I overdid the sauce.’

‘I don’t need a bath. Clay doesn’t smell bad,’ says Tamsin, but Julia takes her by the shoulders gently and guides her in front of a long mirror. Tamsin giggles. She has a streak of clay all down one cheek and a lump of it buried in her curls, plus a hefty blob of tomato mush on her chin and around her mouth.

‘You’ll need your hair washing tonight, my pet,’ says Julia, and Andy throws her an agonised look. May’s heard the noise from the bathroom on shampoo nights. It’s even worse than the ponytail protests.

May is ready now. She doesn’t meet Julia’s gaze as she leaves the room. The brief burst of warmth between the two of them has dissipated, and the tantalising letter is tucked snugly inside May’s bag. She can’t wait to tap into its memories.

It doesn’t take long for Andy to get May home and settled in her favourite chair, with Fossil rubbing around her ankles.

‘Shall I make you a sandwich?’ Tamsin says. It’s her latest skill. She can only do ham or jam so far but she’s building up to cheese. It’s the cutting that’s tricky. ‘I’m getting better at the buttering bit now,’ she adds hopefully. ‘There’s not so many holes.’

‘No, you get back home and get into bed when you’ve had that bath. I’m full of Julia’s scones, thanks.’

May hears them go, with Fossil following just in case there’s any fish going spare at Andy’s. Her bag is on her knee before they’ve even had time to cross the gap and go through the gate between Shangri-La and their terraced house. She fumbles for the letter, fingers made clumsy by urgency. As she pulls the faded blue sheets from their envelope, the familiar buzzing begins and she sighs with relief. It’s happening. She hasn’t lost the knack of tapping into the precious memories.

For a little while, it’s enough just to hold the pages in her hand and feel a warmth spreading through her body. It builds slowly: a tingling, effervescent shimmer of hope, cascading into ripples of delight. May wriggles blissfully. This is what she’s been missing so desperately. On one level, she’s still in her cosy living room hearing the cry of the gulls and the faint sound of Tamsin pushing the cat back in through the flap in the kitchen door and telling him it’s nearly bedtime. On the other hand, she’s floating above the room, high on a wave of wellbeing and happiness.

It’s the lifeblood, flowing into her veins. The power to stay young, or at least to slow the march of time. One hundred and eleven is surely going to be possible now. Eventually, May feels the intensity of the memories ebbing, and reaches for her glasses as Fossil jumps up to settle on her lap. Pulling out the closely written sheets, she sees Kathryn’s name on the final page.

As she begins to read, cascades of tiny bubbles dance through her narrow frame and she has to stop every few sentences to catch her breath.

We’ve just had a newspaper cutting from our Nottingham family telling us of Pauline’s engagement! Quick work, what? I bet her engagement ring isn’t as good as Mother’s. Opals take some beating, especially three such beautiful stones – and the tiny diamonds around them are so pretty too. If only we could find it. Mother’s heartbroken. She’s started behaving very oddly, accusing each one of us in turn of hiding it. As if we would. We all know how much she wants Julia to have the ring. Will’s very upset about it all. Has he written to you lately? That boy gets more and more secretive the older he gets, it seems to me.

May leans back in her chair. After months of memory-deprivation this is almost too much.

She recalls the large, noisy family and their visits very well. Charles was quite chummy with Don’s relatives for a while. He used to take them out in his boat.

It’s time to put the letter away for the night, even though the mystery of the ring is intriguing. Perhaps there will be more clues in the later ones. May’s sure Julia has never had a ring like the one Kathryn describes.

May is lost in echoes of the past now, and thinking of Kathryn puts her in mind of another girl from long ago, with the same name but spelled differently. She reaches over to fetch a dusty book from a low shelf, and sniffs the musty fragrance happily as the pages fall open at her favourite entry.

May’s old school friend Catherine was what they used to call ‘a card’. She loved making up silly rhymes, usually about their teachers, leaving them around for people to find at the most inopportune moments. Catherine really came into her own during a fad for collecting autographs that swept the girls’ grammar school. These weren’t in the modern trend of finding famous people to write in your autograph book, but merely a way of proving how many friends you had by letting them fill the pages with trite, jokey and sometimes rather rude messages.

When May passed Catherine her own precious leather-bound book, she hoped that the other girl wouldn’t write anything that her parents shouldn’t see. She was relieved to read a poem that was more thoughtful than Catherine’s usual doggerel and reminded her of her father’s words about living to the ripe old age of one hundred and eleven when he’d gazed at that beautiful sunset so long ago. Coincidence? May has never believed in them. This was surely a sign. The poem was entitled ‘My Years With You’, and read:

The Bible always tells us

That in the eyes of men,

The time that we might hope for

Is three score years and ten.

But when I view our friendship

Those years seem far too few,

And I will always hanker

To spend more time with you.

So let us aim for five score

Plus ten before we’re done.

And when we reach that milestone

We’ll add another one.

May was enormously flattered to read this, but came back down to earth with a bang when she found out that Catherine had written the same ditty in at least half the class’s books. Even so, the thought of living to the grand old age of one hundred and eleven strongly appealed to May, and over the years the magical number has become her Holy Grail. She’s so nearly there now.

More letters are needed, and quickly. Julia’s got so many she’ll hardly miss a few, will she? And May’s need is so much greater than Julia’s. Her birthday is on the horizon – only three months away – and she has to get there. She simply has to.

Chapter Five (#u5c696aef-bbf8-5483-b853-bbe19d0e2f17)

The next day at around noon, Julia looks out of the kitchen window and sees Andy perched on an upturned crate eating his lunchtime sandwiches. He’s been weeding the rows of broad beans and courgettes he planted in the spring. It’s Saturday, so Tamsin is with him, sitting cross-legged on the grass with a lunch box open in front of her.

Tamsin waves as Julia approaches them with a loaded tray, carefully avoiding the ruts in the path.

‘Have you got my tea things, Aunty Jules?’ she asks, jumping up.

‘Absolutely. I wouldn’t forget you, my love,’ says Julia. She puts the tray down on a nearby garden table in the shade of the oak tree and spreads out the contents – a brown teapot with a multi-coloured knitted cosy, Andy’s oversize mug, a blue and white jug of milk, a tin of biscuits and last of all a miniature tea set for Tamsin.

‘Thank you,’ says the little girl, eyes sparkling. ‘Tea is my best drink ever.’

‘You told me Vimto was your favourite this morning,’ says Andy, ‘and yesterday you said you’d never again drink anything but strawberry milkshake.’

‘Yes, but tea’s my favouritest favourite,’ says Tamsin, then begins humming to herself as she rearranges the teacups more to her liking. Julia remembers her son taking the same pleasure in the tiny cups and saucers, milk jug and teapot with their blue Cornish stripes. His own daughter, in turn, loved them as much as Felix had. Julia sighs. She misses Emily more than she misses her son. Felix isn’t an easy person to get on with – he’s often a bit too fond of the sound of his own voice – but Emily is a delight.

Julia presses her lips together to stop them wobbling. Now’s not the time to get all emotional over a few little teacups. Perhaps she should write and ask Emily to visit at a specific time rather than hoping she’ll make the decision herself? The fear of seeming pathetic catches at Julia’s heart, but she so wants to see her granddaughter.

‘You sad today then?’ asks Tamsin, busy adding milk and a sugar lump to her tea.

Andy frowns at his daughter, but Julia takes a deep breath and smiles. ‘Not especially, sweetheart, it’s just that I’ve been reading these old letters and thinking about the old days.’

‘Oldays, oldays, oldie oldie oldays,’ sings Tamsin to herself as she hands Julia one of the little cups brimming with sweet, milky liquid. Julia takes it, braces herself, and knocks it back in one.

‘Careful. You’ll get the burps,’ warns Tamsin, ‘Daddy gets the burps sometimes. And sometimes he—’

‘Anything interesting in the letters you’ve sorted so far, Julia?’ Andy says hastily, helping himself to a couple of digestives.

‘I … er …’

‘Oh, sorry, I didn’t mean to pry. They’re probably full of personal stuff.’

Julia rubs her eyes to ease the gritty lack-of-sleep feeling that’s built up in them over the months since Don’s death. ‘No, I wasn’t being cagey, it’s just that for a minute I couldn’t remember which one I was reading last. I’m sure it was from Don’s younger sister. She was talking about …’

There’s a friendly sort of silence as Julia racks her brain to think of the gist of that letter. She’s been sorting the letters into decades and is drawn to the fifties and sixties for many reasons. Her own recollections of that time keep mixing themselves up with Don’s family’s news. But as hard as she tries, she just can’t remember what the main point of the letter was. Something about a ring …

‘I’ll just pop inside and fetch the one I was reading last to show you,’ she says.

Five minutes later, Julia’s back outside, and Andy looks up from retying Tamsin’s shoelaces. ‘What’s up?’ he asks, taking in her flushed cheeks.

‘I can’t find the letter I was telling you about.’

Andy laughs. ‘Well, I’m not surprised. Talk about needle in a haystack – there must be hundreds of them.’

‘Yes, but it was only yesterday, and I remember putting it on top of the pile. It isn’t there now.’

‘I’m always losing things,’ says Tamsin helpfully. ‘I lost my best spider last week. I left it in a jam jar in the kitchen, and when I went back, it had gone away.’

Andy doesn’t meet his daughter’s clear gaze and changes the subject quickly. ‘How did you get on with May? You haven’t said much about the visit.’

‘It was fine,’ says Julia absently. ‘She’s coming over every Friday, if you can bring her.’

‘Course I will. Did you find plenty to talk about?’

‘Hmm? Oh … yes … it was quite painless.’

‘Does May give you a pain then?’ asks Tamsin. ‘She doesn’t make me have a pain. I love May. Don’t you love May?’

‘You bet she does, sweetheart,’ says Andy, still watching Julia’s face. ‘We all do. Why are you so anxious, Julia? Did you two argue or something?’

‘Oh, no, it’s not that. I’m just bothered that I can’t put my hands on that envelope.’

‘Who did you say it was from?’

‘I didn’t, but it was from … one of Don’s sisters, I think.’ She bites her lip.

‘Which one? There were two, weren’t there?’

Julia doesn’t answer.

Tamsin waits for a moment and then counts on her fingers as she recites the names. Sisters fascinate her. She has asked Andy for one of her own several times but he says it’s a bit difficult when there isn’t a mummy around. ‘Kathryn and Elsie,’ she says, in a singsong voice. ‘And then there were the three boys. Uncle Don told me about them.’

‘I thought there were only two brothers, Julia?’

‘No, there was—’

Tamsin butts in. ‘There was Will. He was the littlest, and then another little boy called Peter but he went to live in heaven when he was a baby. I bet he knows my mum, doesn’t he, Dad? She probably cuddles him when she’s missing me.’

Julia and Andy are silent, and Tamsin, bored, wanders off to dig a hole in the newly turned soil near the greenhouse. Sometimes she gets to make mud pies in this garden if she asks nicely. Andy turns to Julia again.

‘Is reading about all these times in the past getting a bit too much for you, do you think?’ he says. ‘Only you seem distracted, somehow. Maybe you should put them away for a little while? Have a break. Write to Emily, or something. See if she fancies a visit.’

‘What are you getting at? I’m not going gaga. I don’t need a break.’

‘No, I wasn’t saying—’

‘You think I’m losing my marbles, don’t you? Well, it’s possible. It happened to my mother at about this age.’

There are tears in Julia’s eyes as she marches back into the house, and she wipes them away with the back of her hand, slamming the kitchen door behind her. Andy frowns. Now he’s done it. Why did he have to be so tactless?

His mind returns to their conversation over and over throughout the day, and by evening he’s decided to take action. If Julia won’t get in touch with her granddaughter, he’ll do it himself. Emily gave him her email address and phone number after the funeral, just in case he needed her for anything to do with Julia, and now he does. This is serious.

Andy has seen Emily off and on over the years when she’s visited Pengelly and sometimes actually plucked up the courage to talk to her, but she always seemed rather aloof, even when she joined the rest of the local gang on the beach for impromptu barbecues and illicit cider binges. Her gothic phase was quite scary but she’s left that far behind her now.

It was a chilly day when they said the final goodbye to Don. Emily was wrapped up warmly in a soft black coat so long it almost swept the floor, and she’d added a cherry-red cashmere scarf and lipstick to match. He remembers her telling him that her grandfather posted the scarf the winter before, when Emily wasn’t able to get to Cornwall in time for Christmas. Don was always good at presents. Emily’s hair was out of sight for most of the day, tucked up inside a fur hat. She looked like a Russian princess, Andy recalls, pale and delicate, but stunning.

Afterwards, when they gathered at the local pub with all the available villagers for Don’s send-off drinks, hefty sandwiches and chunks of pork pie, Andy watched breathlessly as Emily pulled off her hat, and corkscrews of golden hair tumbled down her back. It was cross between a shampoo commercial and a Pre-Raphaelite painting come to life.

Andy needed a large whisky to take his mind off the sight. But later, when he tried to talk to Emily, she was so sad that he had not the heart to tell her how lovely she looked. And anyway, he hasn’t been interested in serious relationships with women since Allie died. You couldn’t really count Candice, could you?

He opens his laptop and starts a new email before the unsettling thoughts have a chance to get a grip.

‘Hi Emily,’ he writes. ‘I’m just dropping you a line to say …’

What is he actually going to tell her? Your grandma’s acting strangely? I’m worried she’s not even beginning to deal with Don’s death? She hardly ever leaves the house? He tries again.

… to say that Julia isn’t acting quite like herself, and I wondered if you could give me a call, or I could phone you for a bit of a team talk? I’m really concerned about her state of mind, and the way she’s forgetting things that have only just happened. I know it’s hard for her being alone in the house after all those years with your grandpa, and grief can affect people in different ways, but I’m afraid it’s more serious than just missing him and feeling sad. I won’t tell her I’ve written to you – don’t want her to think I’m interfering.

Love, Andy

He frowns at the screen, deletes ‘Love’ and adds ‘Regards’, then changes it to ‘Best wishes’, and presses Send. At least he’ll have tried. Whether she gets back to him is another matter. Flying around the world doing glitzy book deals and hobnobbing with top authors must be very time-consuming. Writing to a mere gardener will be way down her list of priorities. She probably won’t even bother to reply.

Chapter Six (#ulink_4ce1c3d3-7c75-5e0d-9c47-ed94670dc182)

‘Well, of course I’m OK, darling,’ Julia says. ‘Why wouldn’t I be? I miss Gramps – I’m bound to, aren’t I? But I’m keeping very busy sorting his things.’

Emily imagines her grandmother, short dark hair as smooth and neat as ever, sitting next to the telephone table with her elegant legs up on a footstool, dressed in one of her daytime outfits – a print frock, maybe, or a soft sweater with a knee-length skirt. She can hear Radio Three playing in the background. It’s the sort of tinkling piano concerto that Gramps hated. He’d have switched it over to something more upbeat.

‘So what have you been doing with yourself? Are you getting out and about much?’

There’s a pause. ‘There’s a lot to do at home at the moment. And I’ve got to tell you about the letters, Em.’

Emily listens, fascinated, as Julia fills her in on the chest full of family treasures.

‘You’re kidding? Family memories going right back to the fifties? How cool is that?’

‘I know! But it’s not just that. I’ve found another couple of letters this morning, ones I’d not read before, or I can’t remember having seen them, anyway. I’m getting the strangest hints here and there about something that’s been missing for a very long time and has never been found, as far as I’m aware.’

‘Really? What is it?’

‘A rather unusual opal ring. I remember Don telling me about it. He wanted me to have it when we got engaged but I think his sisters or maybe his brother had other ideas. It belonged to their mother, and then it was lost just before she was going to give it to me.’

‘Wow. Was the ring valuable?’

‘Yes. But also hugely important to the family. It was supposed to bring luck to the wearer. Three perfect opals in an antique setting with little diamonds. I read somewhere that opals are meant to enhance memory and decrease confusion.’

‘Really? I don’t think a few stones could do that, do you?’

There’s a short silence. Emily can hear her grandmother breathing rather heavily. Is she crying? ‘Gran? Are you OK?’

Julia heaves a huge sigh. ‘Yes, dear, I’m fine. I so wish I’d got the ring now, though. I could certainly do with it. I’m sure I’d cope better if it was on my finger. It’d give me strength, I know it would. Opals are so pretty. They catch the light, and almost seem to glow.’

‘It sounds beautiful. So can I read the letters?’

‘Oh, I don’t think I dare risk any of them to the postal system. They’re too precious.’

‘No, you mustn’t. That’d be mad. Shall I come and see you? I’m way overdue a visit.’

‘Emily! That would be lovely! When can you come?’

The sheer excitement in her grandmother’s voice adds to the heap of guilt Emily’s been carrying around for the last few weeks. She knows she should have been back to Pengelly long before this, but there’s been Max to think about. And having Max on the brain has taken up way too much of her time lately.

‘I’ll talk to my boss. I’m owed quite a bit of annual leave but I’ve been too busy to take it this year. I can probably be with you by next weekend, hopefully on Sunday? Only a week to wait. Is that OK? I’ve got some meetings I can’t get out of in the next few days, but after that it should be fine.’

‘So long as I’m not putting you out.’

There’s a slight chill in Julia’s voice, and Emily feels her shoulders slump. She could have phrased it better, but work’s so full on at the moment and it’s not going to be easy to get away at short notice.

‘It’s no problem, honestly, Gran. I can’t wait to see you. Will you make a lemon drizzle cake?’

Another silence. Then Julia clears her throat. ‘How about chocolate fudge, for a change?’

‘Mmm, that sounds yummy. You know I love anything you bake. Right, well, I’ll get going and make the arrangements then. Love you.’

‘You too, darling. See you soon!’

Emily’s heart twists at the joy in her grandmother’s voice as they end the call. She gets up from the huge sofa where she’s been lying in her usual position: flat on her back with her legs up on one of its arms, her head on a heap of cushions at the other end. This is a rare day off for her, and she’s still in her dressing gown. It’s a black and gold silk kimono that Max bought her back from a trip to Japan. Emily had been so touched at the time until she’d found out accidentally through his secretary that he’d bought his wife exactly the same one in blue and green.

She reaches for her laptop and makes short work of booking a flight to Heathrow and then sorting out car hire. It’ll be best to present Colin, her boss, with a ready-made plan to stall any arguments. He owes her several favours, after all, with the extra hours she’s been putting in lately. Then she texts Max to tell him of her trip. He’s working on his latest crime novel at his family home in Cape Cod this week. Emily knows hopping on a plane or heading out in his top-of-the-range sports car at a moment’s notice won’t bother him. But will he want to see her enough to make the effort?

Max cares about her – she’s sure of that – but the trouble is he doesn’t care enough. They met at the glittering publishing party when his latest mind-blowing psychological thriller was launched. Emily wasn’t looking for a relationship, preferring to be a free agent and keep men at arm’s length as much as possible, but Max has seriously tempted her to change her mind, for a little while at least.

She remembers the impact of seeing Max for the first time. It really was the old cliché about eyes meeting across a crowded room. She spotted the man in the shabby cord jacket and jeans as soon as she came in after talking to the caterers, but he was deep in conversation with his agent, Ned, a bumptious character whom Emily usually tries to avoid. As she picked up a glass, he turned and looked straight at her. He murmured something to Ned and leaned in to hear the reply. Then he patted the other man on the back and strolled across to stand in front of Emily, one hand in his pocket, the other holding a flute of prosecco.

In her high-heeled silver sandals, Emily was exactly the same height as Max. His green eyes fixed on her blue ones, and she felt her stomach flip and her heart start to pound.

‘Ned tells me you’re the lady responsible for this affair,’ he said. ‘How come we haven’t met before?’ He sounded like a smoker, which was one of Emily’s pet hates, and his hair was receding – another black mark in her book. But his smouldering eyes more than made up for these deficiencies.

Emily was at that moment very glad she’d bothered to put on the new crimson dress that clung to her curves. It was a bit too short with these heels but it showed off her well-toned arms and shoulders. She had even been to a very swanky hairdresser’s that afternoon in honour of the occasion, and her hair was artfully tousled, her blond curls just how she liked them but didn’t manage to achieve very often. In the morning she’d look like a haystack, but for now … yes, she was feeling pretty good.

‘I’m fairly new to this branch,’ she said. ‘I came over from the London office three months ago.’

‘Their loss. I’m very pleased you did. What time can we leave?’

‘I’m sorry? Aren’t you enjoying the party? It’s taken me ages to organise.’

Emily heard the plaintive note in her voice and cursed herself for sounding needy, but Max just laughed. ‘It’s great, but there’s one problem.’

‘Is there? I thought I’d covered everything. The canapés will be coming round soon, and there’s proper champagne for the toast …’

‘Stop panicking, honey. The problem is that there are too many people. Two is the ideal number. You …’ he touched the tip of her nose, ‘… and me.’