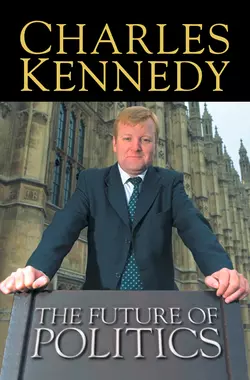

The Future of Politics

Charles Kennedy

The former leader of the Liberal Democrats sets out his personal beliefs and political vision to create a new political language and a new brand of politics.Politics and government are in danger of going out of business unless politicians adopt a fresh and innovative approach. In The Future of Politics Charles Kennedy sets out his views on the problems and the solutions.Until now politicians have been far too slow to react to the challenges created by the forces of globalization, technology, market liberalization, social division, environmental threats, voter disengagement, issues surrounding individual liberty and devolution. They are still tied to the old models of nation states and parliamentary sovereignty.Only if liberalization, decentralization and deregulation are promoted can our political system adapt. Kennedy also argues that government should promote greater redistribution of wealth within society, though not simply through the ‘tax and spend’ mechanism.In The Future of Politics Charles Kennedy has created a new political language and a new form of address which provide radical solutions to the unprecedented problems of our society and the world today.

THE FUTURE OF

POLITICS

Charles Kennedy

DEDICATION (#ulink_2a6b4fa2-856f-51b3-8e61-873b99ccf7d8)

For my parents,

Ian and Mary Kennedy

CONTENTS

Cover (#u2d03b87d-e4ac-5381-a27f-45ec99e503ab)

Title Page (#u0c5dc300-1619-562e-8e65-2921331c9ae7)

Dedication (#u133c1951-fed1-57f3-96c8-86bb1546dfc9)

Preface to the Paperback Edition

Introduction

WHY AREN’T THE VOTERS VOTING?

Chapter One

FREEDOM FROM POVERTY: THE FORGOTTEN NATION

Chapter Two FREEDOM TO BREATHE: THE GREEN FUTURE

Chapter Three FREEDOM FROM GOVERNMENT: PEOPLE AND THE STATE

Chapter Four FREEDOM TO INNOVATE: SCIENCE AND DEMOCRACY

Chapter Five FREEDOM TO GOVERN: THE GREAT DEVOLUTION DEBATE

Chapter Six FREEDOM WITHOUT BORDERS: BRITAIN, EUROPE AND THE CHALLENGE OF GLOBALIZATION

Conclusion A SENSE OF IDEALISM

Notes

Index

Acknowledgements

About the Author

Copyright

About the Publisher

PREFACE TO THE PAPERBACK EDITION (#ubda244cd-74f8-545f-bd90-be56612eba03)

This preface is being written at home in Scotland over the Christmas and New Year holiday period, 2000–2001. At the time of writing my thoughts and political preoccupations are very much focused upon what lies ahead during the next twelve months for British politics in general, and the Liberal Democrats in particular. By the time this paperback edition appears we will more than likely have been through a general election – or be in the middle of the campaign.

Politics and politicians have taken a further beating over the last year. In particular, as the hardback edition of this book went to press in the summer of 2000, something remarkable happened in British politics: direct action, in the form of the fuel blockades, came to the towns and villages of Britain. I refer, of course, to the fuel crisis.

It was remarkable for several reasons. First, such action, organized by individuals rather than trade unions, is rare in Britain. In some Western countries, particularly France, taking to the streets is a much-used part of the political process – and it has achieved its aims on many occasions. Indeed, only a fortnight earlier, the French authorities capitulated in the face of domestic protests over fuel – perhaps sending a message across the Channel. Usually, the British have done things more gradually, believing ultimately that all problems will, at least to some degree, be resolved by a general election.

The second remarkable feature of the fuel protests was the issue itself. There has been rumbling discontent over fuel prices for many years, but except in a small number of constituencies (my own included) it had never been a major election issue – and certainly was not one of the main reasons for the Conservatives’ electoral eclipse in 1997, despite all that they had done to increase fuel taxes.

However, surely by far the most notable feature of the fuel protest was what it said about the state of politics itself. From all the diverse voices of the fuel protestors, one message came through loud and clear: the public want honesty on tax, and they are not getting it. If fuel taxes are necessary to protect the environment, people want politicians to say so – they do not want to be told, as they were by a government insulting their intelligence by seeking to shift the goalposts, that fuel taxes have now become necessary to pay for public services. Shifting the goalposts was exactly what Labour did. All parties had supported the principle that fuel taxes had an environmental objective when Norman Lamont introduced the fuel duty escalator (an automatic annual increase in fuel duty above the rate of inflation) in 1993. Indeed, Gordon Brown’s 1998 Budget was big on the link between fuel duties and the environment. He said then that, ‘only with the use of an escalator can emission levels be reduced by 2010 towards our environmental commitments’. He also spoke of the government’s ‘duty to take a long-term and consistent view of the environmental impact of emissions’.

(#litres_trial_promo) But by September 2000, Gordon Brown was telling the nation that ‘the existing fuel revenues are not being wasted but are paying for what the public wants and needs – now paying for rising investment in hospitals and schools’.

(#litres_trial_promo) The subsequent opinion polls over that summer told their own story. The Conservatives’ standing increased at the expense of Labour, as the Opposition inevitably does when the government faces a crisis. But the Liberal Democrats did better in the polls too – and our message was not a knee-jerk pledge to cut taxes, but a simple, restated pledge to be transparent as to the specific purposes of tax revenues.

Following on from the fuel crisis, came the floods – the other side of the story where climate change is concerned. During the flooding it became rapidly apparent that politicians are not talking nearly enough about the big issues, such as climate change, and that these will make a massive difference to the way that we all live our lives in the decades to come. Unless they start to do so, politics will never reconnect with the people it is losing – and politics will have no future.

This book is about the future, but it is also about me and it is about us – the British. It is one person’s reflections on the United Kingdom, and that person’s reflections upon himself. What makes this Kennedy fellow tick? What makes him angry, what makes him sad? What fires his passion? By the way, does he possess passion? Why is he a Liberal Democrat, and who are these Liberal Democrats anyway?

The story begins in the West Highlands of Scotland in November 1959 and I cannot tell you where it might yet end. My first visit to London was not until the age of seventeen; my third visit was as a newly elected Member of Parliament in 1983. A friend put me up, in those first few crazy weeks, in his spare bedroom in Hammersmith. I didn’t know how you got to Hammersmith from Heathrow airport. I had no idea where Hammersmith stood geographically in relation to Westminster. It was a fast learning curve.

It was not until August 1999, when I was elected as Liberal Democrat leader by the party’s members, that I experieced again anything remotely comparable. The party leadership transforms your life almost out of all recognition, but for the better. You learn every day of the week, and you are never really off duty, but you experience a profound sense of duty in the process.

This book is part of that process. It is about attitudes and aspirations, hopes and fears. It is also about ambition. I am extremely ambitious for the Liberal Democrats, for two solid reasons. First, I believe that we are more correct in our diagnosis as to the nature of the problems of the body politic – and how they can be cured – than are the other parties; second, I am convinced that we will secure the opportunity to put these beliefs into governmental action.

Back to the West Highlands. If you had told me, when I was growing up, that one day not only would there be a Scottish parliament, but that it would involve the Liberal tradition at ministerial level, then I think I would have been ever so slightly sceptical. It has happened. My friend, Jim Wallace, now presides over the system of justice in Scotland.

Due to the initial illness and then tragic, premature demise of Donald Dewar, Jim has also exercised full First Ministerial authority on two separate occasions.

(#litres_trial_promo) Jim’s staple diet these days is red boxes, decision making, trying to get public policy more right than wrong. He is a Liberal Democrat making a serious difference to people’s lives; in December 2000 he became a Privy Councillor and was named ‘Scottish Politician of the Year’ by the Herald. In Opposition at Westminster you make sounds and faces; in the Scottish coalition, Liberal Democrats are taking decisions.

Leadership in contemporary politics has become too much about lecturing and not nearly enough about listening. Some politicians are prone to rant and rave, but Jim and myself have never been from that stable. We need more people of Jim’s sort in public positions. And we need much more liberal democracy in public life. I am determined to help secure such an outcome.

Mine has been a distinctly curious political lineage, all things considered. I joined the Labour Party, at home in Fort William, aged fifteen. As I describe later, that entanglement didn’t last very long. I soon found the dogmatic class war that many Labour activists were fighting thoroughly unpalatable. At the University of Glasgow I was sympathetic to the Liberals but joined the SDP, for which Roy Jenkins can be fairly and squarely blamed.

Out of the unhappy state of British politics in the late seventies, came Roy Jenkins’ famous 1979 Dimbleby Lecture, ‘Home Thoughts from Abroad’. Every so often in life, you hear someone articulate your own thoughts – and they do so with an elegance and eloquence which make you wish you had been able to say it yourself. Roy Jenkins’ Dimbleby lecture had that effect on me. He brought sharply into focus the unease that I, as an open-minded, pro-European, moderate-thinking Scot, felt about the choices that Labour and the Conservatives were offering the British people.

Roy offered a vision of the type of political party I wanted to join. He spoke of the need for a party of the radical centre to bring about constitutional and electoral reform at the heart of our political life, to end the failures of the two-party system. The new political system that resulted would allow parties to co-operate where they shared ideas. The new party that Jenkins saw leading these changes would also devolve power, while advancing new policy agendas for women, the third world and the environment. He spoke too of the need to establish ‘the innovating stimulus of the free market economy’ without the ‘brutality of its untrammelled distribution of rewards or its indifference to unemployment’.

The Dimbleby Lecture was a rallying cry for those who wished politics to move beyond the class war that it had become, and it struck many chords. It was a vision of a radical, decentralist and internationalist party, combining the best of the progressive Liberal and social democratic traditions. It was a vision of the party that the Liberal Democrats have become. From the first, I was clear that I wanted to be part of this new force in British politics. So when the SDP was launched in 1981, I was an early member. A blink or two later and I landed up as the youngest MP in the country, having defeated a Conservative minister in the process in Ross, Cromarty and Skye. There followed a lot of listening and, I hope, learning.

There is a popular, recurrent misunderstanding about the Liberal Democrat neck of the woods in politics. Many people – journalists and the wider public alike – seem to think that operating within the confines of the SDP, an SDP-Liberal Alliance, and the Liberal Democrats today, is somehow less demanding than being Labour or Conservative. Believe you me, it’s not. It is every bit as demanding and, to a certain extent, even more so.

You have to fight for every column inch. You get two questions on a Wednesday afternoon at Prime Minister’s Question Time – when the leader of the Opposition can rely on six. Contrary to popular opinion, the job of leader does not carry a salary. No complaint there. You occupy a certain space in the unwritten constitution of the land – from State occasions to the Privy Council – but somehow you are not quite part of the in-crowd. It is all very curious.

Since 1983 my world of politics has changed out of all recognition, and not just due to the party’s achievement and progress over nearly two decades – the landscape of politics itself has altered. The key issues that set the tone for much of the twentieth century – socialism v. capitalism, public v. private ownership – are now no longer debated. Today the issues are quite different – professionalism v. the market, interdependence v. nationalism, community responsibility v. self-interest.

There is also the issue of women’s rights and role in society, which is rightly coming far more to the fore of the political agenda. It should be a core issue for all in politics Despite the advances that women have made since receiving the vote, many still do not have equal life chances to men. A disproportionate number of women still suffers conditions of poverty in the UK. For women in work, the problems of part-time employment make a particular impact; and although women comprise 44 per cent of the workforce, the proportion of women in managerial and administrative roles is still only 32 per cent. Politicians are gradually recognizing these inequalities and deliverying policies which meet women’s needs and support their aspirations.

We are also all coming to terms with post-devolution party politics. As a Scot I am acutely conscious of that fact; so is Prime Minister Blair, who has admitted his mistake in interfering in the politics of the Welsh Labour Party over the election between Rhodri Morgan and Alun Michael.

(#litres_trial_promo) We even have the irony of the Conservative and Unionist Party leader seeming to welcome the fact that a combination of devolution and a degree of proportional representation has brought life back to the political corpse which his party had become in Scotland and Wales. Altered images indeed.

On the key issues of today, Liberal Democrats are in a better position than the other parties to set the agenda. We start off by trusting people. In 1865, Gladstone defined Liberalism as ‘a principle of trust in the people only qualified by prudence’, contrasting it with the Conservatives’ ‘mistrust of the people, only qualified by fear’. And I am always struck by Vernon Bogdanor’s characterization of the nineteenth-century Conservative Party as pessimistic, fearful of democratic change, and inclined to rely on central rather than local government for political solutions. Little has changed in the modern Conservative Party. We are also different because we are strong defenders of the spirit of public service: we value the expertise of professionals, and want to fund them so that they can do their jobs effectively, particularly in health and education. We want to promote social justice through health and education. We alone, apart from the Green Party, stress the environment as a fundamental part of politics. We are an internationalist party, comfortable with playing a constructive role in Europe, but ready to reform it, and look beyond European frontiers. We recognize that women and ethnic minorities still face enormous barriers to involvement in public life. We are willing to champion the needs of sometimes unpopular minorities – essential at a time when the Conservative Party is willing to exploit the debate on asylum seekers for party ends. And above all, we tie these concerns together with a commitment to the liberty of the individual, a cause that the other parties cannot lead – Labour has a strong authoritarian streak, while the Conservatives tend to equate liberty with rampant market forces.

This is the territory upon which the Liberal Democrats now operate. Society seems to be defined by near-instantaneous flitting images; as a consequence we have to be fleet of foot politically. Our past weakness, support too evenly spread in every conceivable sense, is today a source of potential strength. We must be sharp, but, emphatically, we must not be concentrated only in some parts of the country.

Now exactly what, I hear you say, does he mean by that? Allow me to explain. There is no point in this or any other political party existing or campaigning without a common purpose and a collective attitude. The Liberal Democrats have that – and it is frequently infuriating. It questions, it ridicules, it gives the awkward squad an honorary degree for their troubles. The party dislikes top-down policies. And it puts people like me in their place. Frequently.

However, it is part of the spirit of the age. People do not trust their politicians much; there is a collective dubiousness out there which is a legitimate cause for concern. Certainty has given way to uncertainty, the council estate – where the residents tended to vote en bloc one way because they all worked at the same local factory – has changed out of recognition. That local factory, or coalmine, or steelworks, or shipyard, probably no longer exists. And the council estate these days is full of families who have bought their own homes and whose children send mail down the phone line.

But has the political establishment changed accordingly? Not really. We carry on, pretty much upon the same tram-lines, affecting modernization yet not, somehow, giving real vent to it. The nineteenth-century building that houses parliament all too often contains the remnants of nineteenth-century habits. We are failing citizens as much as we are failing ourselves. And yet, away from Westminster, 2000 showed that all is not lost.

Things have got better since May 1997. In particular, the government has spread more power throughout Britain through devolution than any Conservative government would have ever contemplated. And in that time we have had clear signs of how disastrous a William Hague-led Conservative government would be: slashing taxes for the sake of it, retreating from Europe, and still pretending that there can be improvements in health and education without paying for them.

The result of the Romsey by-election on 4 May 2000, coupled to our exceptional 28 per cent share of the vote at that day’s local elections, demonstrates that the British people realize what is involved. In particular, it is clear that people are not taken in by Mr Hague’s populist, saloon-bar rhetoric on asylum seekers. After the last election, people said the Conservative Party could sink no lower. But William Hague’s behaviour did sink lower, and he got his just deserts from the people of Hampshire.

Nobody should underestimate the significance of that result. The Conservatives, while in opposition, have only twice before in the last hundred years lost an incumbent seat to the Liberal tradition at a parliamentary by-election. The first was in Londonderry in 1913, remarkably, given that the Liberals were in government. The second was the 1965 triumph in the Scottish Borders of a young man called David Steel.

There are, surely, two big implications which flow from the upheaval in Hampshire. First, there is no genuine, far less gut, enthusiasm out there for the William Hague Conservative Party. His narrow, jingoistic approach has next to no broad, public appeal. The Romsey result cannot be dismissed as the usual ‘mid-term protest against a Conservative government’. There is no Tory government to protest against. On the evidence of Romsey, the Conservative Party is less popular than it was when it met its nemesis on 1 May 1997, and after the next general election there will still be no Conservative government to protest against. Since Romsey, moderate support for the Conservative Party has continued to fall away, and I was delighted to welcome Bill Newton-Dunn, the Conservative MEP, into the Liberal Democrat fold in November 2000.

Second, people have clearly learnt one of the major lessons of the 1997 general election: that it is vital to look at the local situation when casting your vote. People are no longer being guided simply by national trends or old loyalties when voting. They are looking at how they can best deploy their ballot with the maximum effect. In Romsey that meant that Labour voters made their vote really count – some for reasons of disillusion, others because they see an alternative Liberal Democrat opposition which they find more attractive to the administration of the day. It is now clear that the 1997 experience is being repeated, and voters are regularly prepared to use their votes with lethal intent where it can matter. I have this year chastised the BBC, for example, over their tendency to speak in terms of ‘the two main political parties’. Apart from ignoring the disparate and distinct political systems at work within Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland, it also overlooks electoral reality where the Liberal Democrats are concerned. In truth, as in Romsey, across large swathes of the country, we now have varied patterns of two-party contests – involving all three UK political parties.

I want things to get still better, and they can. In his Dimbleby Lecture, Roy Jenkins mapped out an approach to our political process which has been more than vindicated by events. Quite simply, he was correct. If, as a country, we had listened to and acted upon his prognosis, then a lot of subsequent history would have been different.

Which brings me to today. I believe that the individual is now king, the consumer is in charge. It is right to opt for interests of the individual and the community rather than those of the state. Ask Tony Benn or Tony Blair what they think instinctively about the structure of society, and their answers will tend to centre on the jobs people do and how much they earn. Ask most Conservative politicians and you will find that the Thatcherite mantra of ‘no such thing as society’ still dominates William Hague’s party. Ask a Liberal Democrat and they will respond in terms that stress the relation of individuals to their communities.

It is an altogether different approach to life which needs to be understood clearly. We are in politics to promote the liberty of the individual – the best life chances for all, whoever or wherever they are. That is the core value at the heart of this book, at the heart of my politics and at the heart of the party I lead.

INTRODUCTION: WHY AREN’T THE VOTERS VOTING? (#ubda244cd-74f8-545f-bd90-be56612eba03)

‘I’m not political’ is a phrase I used to hear a great deal. Even in the ferment of Glasgow University in the seventies I was occasionally pulled up sharp when fellow students told me that their interests didn’t extend to what I saw as the ‘big issues’ of the day: nationalization, inflation, trade union power, unemployment and Scottish devolution.

Of course, now that I am an MP, dwelling for the large part in a world populated by fellow Members, journalists, party stalwarts and others intimately involved with the theory and practice of politics, I don’t hear it so often, but I’m fully aware that ‘out there’ in the real world, being ‘political’ does not always mean caring about how the country is run and trying to do something about it. It means something quite different, for instance, rigidly holding a set of outdated principles, having faith in and being involved in a process that for many people has no currency, and it means sleaze. To be ‘political’ is akin to admitting that you are a trainspotter or a collector of antique beermats – a crank, and not always a harmless one.

It’s not just ‘political people’ who suffer as a result of this perception. For a large percentage of British people, the whole political process is deeply boring. It’s obscure, it’s impenetrable and, most importantly, it doesn’t matter if you understand it or not, because – so the logic goes – it doesn’t make any difference. Twenty years ago, it was still possible to find pubs where signs above the bar said ‘No politics or religion’, presumably because they were the two subjects most likely to cause a fight. Nowadays, you never see it, because either people don’t discuss politics at all, or, if they do, it’s conducted with such apathy that the chief danger is that the participants will fall asleep.

I was chatting with an acquaintance recently. I asked him if he’d seen the satirist and impersonator Rory Bremner on TV last night. He shook his head. ‘He does too many politicians,’ he complained, ‘so I ended up watching the snooker.’ I am not, I hope, out of touch. But it had never occurred to me that some people might find his show uninteresting precisely because a large part of its content is political satire. In essence my acquaintance was saying that politics is a turn-off, something that makes you want to change channels.

I don’t blame people for having these opinions. There are many aspects of British politics I dislike. Westminster politics, structured around the two-party system for so long, often looks personal, petty and adversarial. Even with the advent of the so-called ‘Blair Babes’, Parliament often seems like an exclusive gentlemen’s club. I do not believe in dismantling tradition indiscriminately, but much of the day-to-day ritual and protocol at the Palace of Westminster contributes to people’s sense that what goes on there is distant from, if not irrelevant to, their lives.

(#litres_trial_promo)

Members of Parliament often suffer similar feelings about their place of work. I remember vividly that when the Berlin Wall collapsed in November 1990, my colleague in the Commons Russell Johnston (formerly MP for Inverness, Nairn and Lochaber), suggested suspending the scheduled business, in order to hold an emergency debate on the titanic developments in Germany and their historic implications. This was ruled impossible, even though the bulk of MPs would have agreed and the Speaker was sympathetic. So the scheduled business went ahead, with run-of-the-mill turnout in the House. It was much the same following the release of Nelson Mandela. Both events filled me with optimism, but the sheer inertia and inflexibility of our own parliamentary system left me feeling gloomy afterwards. It seemed to me very poignant that, while Europeans were breaking down frontiers, the British Parliament was burying its head further in the mud of tradition.

I also view Prime Minister’s Question Time with a measure of distaste. Before I became Liberal Democrat leader I rarely took part in it. I sat through many sessions during my time as a rank-and-file MP, but I never found it a particularly useful political device. Many aspiring party leaders seek to make their mark by launching jibes at the Prime Minister of the day, but tempting though it sometimes was, with characters like Margaret Thatcher and John Major at the dispatch box, that was never for me – it would be possible to count the number of questions I asked on the fingers of one hand. I usually find Prime Minister’s Question Time an irrelevant piece of theatre – a tale of sound and fury, as the quotation goes, signifying nothing.

The problem is that, all too often, the weekly rant at the dispatch box is all the public sees of Westminster politics. William Hague is good at soundbites in the House of Commons: ‘Frost on Sunday, panic on Monday, U-turn on Tuesday and waffle on Wednesday’ was his summary of Tony Blair’s baffling comments on NHS reform in January 2000. Later, outside the Chamber, our Prime Minister commented that William Hague might be good at one-liners, but lacked anything constructive to say. No surprise then, that after being exposed to such tit-for-tat exchanges, the voting public finds parliamentary politics a turn-off.

The televising of Parliament has, unfortunately, done little to reverse this problem, as surveys show.

(#litres_trial_promo) There is even evidence to suggest that, far from making the process more open to public scrutiny, televising has led to changes in parliamentary behaviour which have, in turn, made the process seem even less relevant to the general public. In 1992, I drew attention to the fact that the number of bogus points of order seemed to have rocketed at exactly the point when TV coverage began. Some Honourable Members clearly found the temptations of appearing on the small screen more important than efficient scrutiny of the executive.

In terms of parliamentary coverage, the weekly session of Prime Minister’s Questions is TV’s finest hour, but, as I have mentioned, it is all too often little more than the swapping of insults. Predictably, the news networks tend to edit out the calmer moments and overlook the plentiful evidence of inter-party accord and co-operation, because it is not as exciting as a good row. The result is that the viewing public sees MPs as a highly undignified, hugely self-indulgent collective of ego trippers.

The structure of the House of Commons perpetuates this points-scoring ethos – the two facing sides of the Commons engender the sense that one half of the country is ranged against the other half. I would like to see the existing furniture scrapped and replaced with a horseshoe seating arrangement. Most European Parliaments have gone for this model, as have the Scottish Parliament, the Welsh and Northern Ireland Assemblies and the US Congress. People may say that cosmetic changes make no difference, but I disagree entirely. If the image you send out to voters through the media is of no relevance, why does Tony Blair spend so much money on his platoon of spin-doctors and image consultants? A rebuilt House of Commons would, in my view, achieve more than an army of Alastair Campbells. It would send out the message that politics is not a rugby game anymore, but a process of co-operation, hard work and winning arguments.

In spite of technological advances, the conduct of politics and its key events has changed little. Party conferences are still centred on an audience, a platform and a series of long speeches, culminating in forty minutes of rhetoric from the leader, but there is no law stating that every conference has to be like that. It is revealing to reflect that by far the largest proportion of party conference media coverage these days is generated on the fringe, in the studios and’, doubtless, within the bars and the restaurants. The former Conservative MP Matthew Parris, now a respected political commentator, has said that the best way to keep a secret in Parliament is to make a speech about it in the House of Commons. That view finds a ready echo at the party conference: if you really want to know what is going on, then probably the last place to look is inside the conference hall itself. It could be different. The Internet offers great opportunities for people everywhere to ask questions, debate issues and even vote – but instead we only have a virtual tour of Downing Street. It is more common for TV soap stars to go on-line than politicians – in my view, it should be a regular segment of every politician’s working life, as well as forming a key part of annual conferences.

Some key events in our recent history have served to harden public attitudes to Parliament and politics. The Maastricht Treaty was a classic example and typifies the problem – it proved a fascinating and instructive experience for my party and myself, but the public’s view of the affair was radically different. In particular, it showed how damaging the adversarial system of politics that we have in Britain is. Too many people, both politicians and commentators, expect you to oppose whatever the merits of the case, and anything short of complete opposition from an opposition party is liable to be misunderstood. It is worth analysing the episode in some detail.

It is all too easy now to forget the depth of political depression which engulfed the centre-left following John Major’s 1992 general election victory. Many of us had expected, prior to the election, that we would be taking our places in a balanced Parliament, in which no party had overall control. The prospect of working in a coalition, almost certainly Kinnock – Ashdown led, was an intriguing one. The prospect of real progress on fair votes for Westminster seemed near at last, but the Conservatives were returned in the face of an economic recession: if the non-Conservative forces failed to triumph against such a backdrop, then what chance was there of ever replacing the Conservatives in office?

John Major’s personal position initially appeared unassailable. One photograph captured his and the media’s assessment of the post-election Conservative invincibility. Attending a cricket match, he closed his eyes and turned his face skywards to bask in the sunlight. It was a telling image, which just added to my feelings of deep gloom.

Around this time, I had personal conversations with Robin Cook (at that point the Labour leadership campaign manager for John Smith) and later with Tony Blair and Peter Mandelson. The former occurred over a Chinese meal in a Pimlico restaurant – and since we found ourselves occupying a table immediately adjacent to the Conservative Education Secretary, Gillian Shephard, I cannot claim that the rendezvous was at all clandestine! It was clear that Smith’s election was a foregone conclusion, and equally clear that he was emphatically in favour of devolution. I also knew that Robin had a sympathetic ear as regards proportional representation. For these reasons, we agreed to stay in touch, not least where a shared agenda on constitutional reform was concerned.

Tony Blair was anxious to be less public and eventually our trio broke bread at Derry Irvine’s London residence. I knew Tony reasonably well, and we had recently appeared alongside each other in media debates during the campaign and afterwards on Channel Four News, which ran an inevitable ‘Losers’ Lament’ segment on the Friday after the Tories’ election victory. Although I have, throughout my career, had various Labour luminaries (including Mo Mowlam) urging me publicly to cross the floor and join their camp, this was not the purpose of the meeting with Tony and Peter. Their principal interest was in the potential for dialogue with Paddy Ashdown, but neither felt sufficiently familiar yet with his direction and policies. His post-election speech in Chard, in his constituency, tackling the future direction of the Liberal Democrats and our relationship with other parties, had caught their attention. I provided a positive thumbnail sketch and encouraged further contact.

So, purely informally, centre-left ruminations were taking place as some of us wondered aloud whether we had any prospect of a meaningful political career. I doubt many of us anticipated the scale of the political earthquake that was just around the corner. The source of the earthquake was equally surprising – a small nation famous for its bacon, but otherwise rarely in the British, far less the international, public eye.

On 2 June 1992, the state of Denmark suddenly became the focus of worldwide attention, when its citizens voted ‘no’ in their referendum to approve the Maastricht Treaty. The treaty essentially provided the framework for greater economic unity between all the European nations and changed the European Economic Community to the European Union. Denmark’s ‘no’ was, in a sense, a ‘no’ to the notion of Europe.

I was standing at the Members’ Entrance of the Commons, awaiting a mid-evening taxi, when a journalist from the Independent broke the news that there was something rotten in the state of Denmark. The next morning, I awoke to an unusually uncertain Douglas Hurd on Radio Four’s Today programme, insisting that the Second Reading of the Bill, giving effect to Maastricht ratification, would proceed as planned. Paddy Ashdown phoned me and said he agreed. Nevertheless, we were all overtaken by the rapidity of events – by mid-morning, government whips had decreed that the Bill would be pulled. It taught me the folly of parking one’s political principles: while the government sat inert, Eurosceptics on both sides of the House were able to gather momentum.

Britain suffers the consequences to this day, in terms of its compromised position within Europe. While neighbouring states move towards closer union, and their citizens benefit from the greater stability and increased trade that this provides, Britain remains on the outside.

This profound tactical and strategic miscalculation propelled both John Major and John Smith into a parliamentary stand-off that was deeply injurious to themselves and their respective parties. If ever there was a case of the straitjacket of Westminster partisan politics triumphing over the greater good, then this was it.

It is worth standing back and reviewing the scenario at that point. A free vote over Maastricht ratification would, prior to the Danish ‘no’ vote, have commanded something like a four-fifths Commons majority in the division lobbies. Parliament was so essentially pro-European that there would have been practically no obstacle to us accepting the terms of Maastricht fully. Seasoned Tory Eurosceptics such as Teddy Taylor, Jonathan Aitken and Nicholas Budgen had become christened ‘The Night Watchmen’ for their readiness to keep the House sitting into the wee, small hours as they grilled ministers over the detail of harmonization measures. Long-standing Labour critics, including Peter Shore, Denzil Davies and Austin Mitchell, were characterized as ‘the usual suspects’.

The essential guilt will always lie with John Major – it was his government’s decision to postpone the Bill – but the late John Smith, much as I liked and admired him, has to shoulder his fair share of the blame as well. A combination of bad and short-term judgement on matters European would prove to be an exothermic elixir. As Roy Jenkins remarked to me at the time, Smith was ‘doing a Harold Wilson’ – ducking and weaving to appease both the modern elements of his party who were pro-Maastricht and the diehard Eurosceptics. He made certain that the debate centred disproportionately around the Social Chapter, the one element of Maastricht that every Labour Member agreed with, regardless of their feelings about the wider question of Europe. He was thus able to maintain an impression of party unity, without making any substantial steps towards ratification. His approach would, in fact, have prevented the treaty from being ratified, had my own party not voted with the Conservatives.

Postponing the Bill immediately elevated a decision made in Denmark into a meltdown in the so-called Mother of Parliaments. The (mainly) Tory Eurosceptics could hardly believe their unexpected good luck. They gained a foothold which they are still exploiting to this day.

John Major, meanwhile, fashioned a fumbling way forward and succeeded in throwing away what should have been an inbuilt parliamentary majority on this issue – a majority which was instinctively pro-Maastricht – and instead let loose Eurosceptical forces which were, ultimately, to destroy his premiership.

In the middle – literally and politically – were the Liberal Democrats. Rather than lament the past, I believe it is more helpful to analyse where we went wrong. We had said in our manifesto that we were pro-Maastricht and wanted to see its swift ratification. We did not back down from that position, even when things started to get worse, as they surely did. John Major, having blinked, then blinked twice. After postponing the Second Reading debate and vote, he then came up with a most curious constitutional device – a ‘paving motion’, so-called because it paved the way, by giving parliamentary legitimacy to further consideration of Maastricht. The Liberal Democrats had to vote for it on the basis of their conviction that Maastricht was right, along with the majority of Conservatives, but it was a marriage made in hell. And it was just a taste of things to come.

John Smith contrived successfully to portray this rather meaningless paving motion as somehow tantamount to a no confidence vote in the government – on the grounds that if Major was defeated, in part by a backbench revolt, it was a sure sign that no-one wanted him as leader. Labour’s Machiavellian skill in this was more than matched by Tory ineptitude, as several Cabinet Ministers announced via the airwaves the need for a show of confidence in Major and his administration. Which was, predictably, not the best way to inspire confidence.

This placed the Liberal Democrats generally, and myself as European spokesman in particular, in a position of acute difficulty. I felt the paving motion was no more than a device to cloak the real issue, and described it as such in my weekly Scotsman newspaper column. This was seized upon by my Labour opposite number, George Robertson, and by the SNP Leader, Alex Salmond. However, we were determined to act out of principle and support the spirit of Maastricht.

The more the Tories worried over being able to carry the vote, the more they had to stress the ‘confidence-in-John-Major’ angle, as a means of reining in their Eurosceptic recalcitrants. But the more they stressed this, the more difficult it became for Liberal Democrats to vote for it. We wanted Maastricht but, needless to say, we didn’t want a Tory government, so it stuck in the craw to be portrayed as saying, effectively, that we had confidence in it.

It was a tense and unhappy time, made worse by the fact that pro-Europeans in all three parties were finding themselves artificially divided as a result of Conservative maladroitness and Labour skullduggery. I defended our pitch along the media trail, but became increasingly unhappy that our consistent and principled approach was being sullied by association.

The Mirror’s excited Political Editor, one Alastair Campbell, used a radio discussion with me to put forward the patently absurd notion that somehow a defeat on the paving motion could unleash forces that might precipitate a general election. This was sheer wishful thinking and I wasted no time in debunking the idea. The worst thing was that, while the other parties hijacked the issue for their own ends, the public completely lost sight of the issue that had sparked the whole affair. The principles of Maastricht – of greater European unity – became completely obscured. I was bombarded with letters begging me not to vote with the Tories.

With a bad taste in our mouths, our votes were cast with the government and secured them a tight majority on the night. There was great bitterness at the outcome, particularly from the Labour camp. Some Labour MPs behaved shamefully on the floor of the House, delivering highly personalized abuse in our direction, while one, a long-standing, normally friendly acquaintance, refused even to acknowledge me as we passed each other in the Central Lobby. This was jaundiced politics at its worst.

So it was, under these distinctly inauspicious circumstances, that the tortuous process of activating the Maastricht Treaty began. It was an experience that taught me some hard lessons about politics in general, and Westminster-style politics in particular. Because the government had a majority of only twenty, and could not rely on its backbench rebels – some of whom seemed to make a career out of dissenting – they depended on our support to secure majorities in key divisions. So we were key players, and at the time, particularly at 3 in the morning, that was far from easy. As with most hard times, the benefits have only become visible in retrospect. The Liberal Democrats entered, and ultimately emerged from, this sequence of events with their integrity intact and, I believe, their reputation enhanced. This was due, in no small way, to the political acumen of our leader, Paddy Ashdown.

Paddy got a central judgement absolutely correct from the outset: we would give our support on key votes based on the issue at stake – and not in return for favours in other areas. But we will never forget the widespread apprehension and distaste with which we found ourselves presented as propping up a deeply unpopular government on a near-nightly basis, for months on end. We gained from that experience, and the fact that the party remained unified was down to strong leadership from the top. As a result, the image of the party gained coherence and credibility. A useful by-product was that it put us in the news, and kept us there.

There were considerable behind-the-scenes dealings with the Tory government throughout this period. Archy Kirkwood, our Chief Whip, Russell Johnston and myself were in constant touch with Richard Ryder, then Conservative Chief Whip, about likely voting intentions. On particularly key issues, Paddy Ashdown and Douglas Hurd became involved, but procedural glitches meant that nonetheless the bulk of the Maastricht business ended up being debated on the floor of the House, rather than dealt with swiftly in the Committee Rooms, which meant very late nights and frayed tempers.

What disappointed me then, and continues to do so to this day, was the damage that the Maastricht affair did to the popular conception of European unity, and the wider public image of politics. At first, the risk was that the public would respond to the scaremongering, and view Maastricht as some scourge from abroad that threatened the Union Jack and could potentially topple the government. The letters in my postbag demonstrated the extent to which people understood the debate in precisely those terms.

Then, as the debate dragged on – and drag it did, from May 1992 to July 1993 – people stopped viewing Maastricht as a demon and simply lost interest in the many good things that it offered the nation. It was a classic example of the way adversarial politics and intra-party chicanery serve to increase public uninterest in the political process.

This increased – albeit limited – exposure to the workings of a government proved very instructive for me. It certainly confirmed in my opinion the importance of cross-party co-operation, even though, self-evidently, after such a prolonged period of untrammelled power, the Conservatives were unprepared for such a close relationship. I think they found having to deal with the Liberal Democrats a vaguely demeaning experience. We, on the other hand, learned to take an entirely pragmatic approach. If it was something we wanted, like Maastricht, then we could and would co-operate to get it. This was a vital lesson for us.

But while Liberal Democrats learnt lessons, democracy suffered. The Conservative attitude at that time was rather akin to the Labour attitude over the Welsh Assembly in the early months of 2000, when Labour in London was determined to keep Alun Michael in charge. Co-operation sometimes seems to be a dirty word in British politics, which often resembles a game of rugby: opposing teams fighting to be the single victor. This is apparent in the half-hearted response I have received each time I have called upon Tony Blair and William Hague to join me in establishing a tripartite approach to drugs and pensions. Until and unless the Conservative Party comes to terms with a more pluralistic conduct of politics, it will wait a long time before being readmitted to the mainstream. Until Labour does so less half-heartedly, it will miss opportunities. Unless British politics can accommodate itself to inter-party co-operation, the public will continue to view issues in the way they came to view Maastricht.

I have gained something of a reputation for myself over the years as a radio broadcaster, perhaps most noticeably in my Today programme broadcasts with Austin Mitchell, the Labour MP and the Conservative, Julian Critchley. The ‘Mitch, Critch and Titch’ trio may have been popular with the listeners, but I found that, even within my own party, it attracted some hostility, largely because people disapproved of the idea that MPs of different leanings could get on and have a laugh, even allowing their own parties to be mocked by the others. But have a laugh we do; whenever I am in Yorkshire or Shropshire, I visit Austin and Julian, and think nothing of it. Many people seem to feel that any suggestion of amity trivializes politics, but I feel quite the opposite, preferring to recount the words of Winston Churchill, who upon returning to office in 1951 said: ‘Now perhaps there may be a lull in our party strife which will enable us to understand more what is good in our opponents.’ All the while politics is conducted in hushed, reverential tones, all the while it takes itself so seriously, and perpetuates intense and entrenched rivalry, then the nation will find it trivial.

The tribal model of politics does not even reflect the way people vote. In the eighties, my party had an unchallenged record for coming second in elections across the board: local, national and European. We did so because there was always a bloc of voters who would support the Labour or Conservative candidate regardless of the issues under discussion, but breakdowns of modern voting patterns show that people vote for a range of candidates and parties at different electoral levels. The old sectarian loyalties are breaking down and being replaced by a concern for issues. That is one reason why Ken Livingstone drew such wide and varied support when he stood independently of his party in the elections for London Mayor. A 1999 survey found that nearly two thirds of people polled had ‘not very much’ or ‘no interest at all’ in local politics and over one third felt the same about politics in general. Only 3 per cent of the country were members of a political party – lower than the figure for membership of the National Trust or the RSPB!

The voting public may be more discerning – and I welcome that – but it is becoming an increasingly rare breed. Disenchantment with politics is a national characteristic, but it affects certain groups more severely than others. It is particularly a problem among young people. A 1998 MORI survey of eighteen-year-olds revealed that four in ten young people are not registered to vote – five times as many as in the general population. The reported turnout of eighteen to twenty-four-year-olds in the 1997 general election was some 13 per cent lower than that for the electorate as a whole. It was also lower than in the 1972 election, so the trend is worsening. According to Vernon Bogdanor, Professor of Government at Oxford University, only 12 per cent of eighteen to twenty-four-year-olds say that they will consistently vote in local elections, and 52 per cent say they will never do so.

(#litres_trial_promo)

The low level of enthusiasm for voting is a reflection of the critically low interest in political matters as a whole. Half of eighteen to twenty-four-year-olds surveyed by MORI in 1999 reported that they were not interested in politics. Over 80 per cent claimed to know little or nothing about Parliament, and 30 per cent said they had never heard of proportional representation! As someone who has visited many schools and colleges across the country, I can say without reservation that today’s young people are just as energetic and curious as my own generation, if not more so, but the truth is that their interests are focused increasingly away from politics and onto other things. We politicians have clearly played a part in that process.

As someone who has attended nearly every Brit Award ceremony since entering Westminster, I find it telling that politicians are hardly ever invited any more to present one of the awards. It used to be a common occurrence, but they simply do not have that sort of status among the young nowadays. If MPs stand too close to a pop star, they are more likely to get a bucket of water thrown over them, as happened to John Prescott a couple of years back. I felt a great deal of sympathy for John on that occasion, but I thought the episode was a telling symbol of popular disenchantment.

Given that young people nowadays are less likely than before to be interested in politics, to be knowledgeable about the political system, or to have formed an attachment to a particular party, what does this say about their attitudes towards the whole democratic process? Surely their low levels of political interest and knowledge translate into mistrust, cynicism and apathy?

The figures support this contention. A MORI survey of sixteen to twenty-four-year-olds ranked politicians and journalists bottom on the list of people they could trust. The same survey asked youngsters whether they thought various schemes (such as polling booths in shopping centres and Internet voting) might encourage them to vote. The answer was an overwhelming no. Such is the level of disillusionment among the young – they are not abstaining because voting is inconvenient. They are abstaining because they quite plainly cannot see the point.

This attitude translates into a wider sense of alienation from nation and community as a whole. Over one third of those polled said they did not feel strongly attached to their community; a fifth said they felt the same about their country; and two thirds reported feeling little or no attachment to Europe. Over a third said they knew little or nothing about their responsibilities as a citizen. Politicians should be frightened by what these figures are saying: there is a whole stratum of young people who don’t vote, know nothing about politics and don’t feel that they belong anywhere.

Disillusionment is not solely a feature of adolescence, at least not in terms of politics. Youths who can’t see the point in voting grow into non-voting adults. As a result, Britain’s turnout record leaves a lot to be desired. The public seems to have least interest in European elections. For example, in 1979, 1984 and 1989, around one third of the electorate voted. In 1999 it was even worse – less than a quarter, making Britons the most reluctant voters in the EU.

Analysts have not undertaken any serious study of non-voting in European elections. It is generally assumed that the remoteness of the European Parliament and antipathy towards the EC/EU accounts for the low levels of participation. The unwieldy size of European constituencies also makes it very difficult for the parties – who are used to campaigning in Westminster constituencies – to work effectively on the ground in order to get voters out of their front doors and down to the polling booths.

Far more worrying is the body of statistics which shows that there is similar public apathy when it comes to electing our own governments. Turnout for the 1997 general election was 71.4 per cent, the lowest figure since 1945. Despite the unpopularity of John Major’s government, over one quarter of voters stayed at home. We are not the most apathetic country in Europe, but our turnout figures compare unfavourably with those of Spain, Sweden, Greece and Italy. If we add New Zealand, Australia and the USA to the equation, then Britain has the fourteenth poorest voting figures out of twenty nations.

This is a nationwide problem. The electoral roll doesn’t help, as there is a time lag in setting up the electoral register, which makes voting difficult for people who move around. The situation was also exacerbated by the hugely unpopular Poll Tax in the eighties, as large numbers of people took themselves off the electoral register in order to avoid paying the tax, but this predates the Poll Tax: the trend of turnouts in general elections has been downwards since a post-war high of 84 per cent in 1950.

Some elements of British society seem to be more disengaged than others. We have already seen that the young vote in disproportionately small numbers. There is also a huge variation in turnout figures when we compare different constituencies, which often ties in with levels of social deprivation, particularly with levels of unemployment. In 1997, turnout ranged from 81.1 per cent (Wirral South) to 51.6 per cent (Liverpool Riverside). In May 1997, the unemployment rate in Wirral South was 5.1 per cent, while Liverpool Riverside had a rate of 19 per cent unemployment, the third worst figure in England. In short, the poorest sections of society, those with, arguably, the most pressing reasons to make their voices heard and bring about change, are the most disillusioned with the political process and the least likely to vote.

Some of these concerns are far from new. I recently came across a fascinating book on the Chicago Mayoral election of 1923. Then, out of an electorate of 1.4 million, only 723,000 voted – a turnout of slightly under 52 per cent. Non-Voting: Causes and Methods of Control,

(#litres_trial_promo) looks at some familiar problems, including the public views that ‘voting changes little’ and that ‘politicians can’t be trusted’. In the twenties, though, much of the blame for poor turnout seemed to be blamed on the cowardice, laziness, ignorance or stupidity of voters.

Today, we are far more likely to look at the failings of politicians rather than voters. This is, in my view, entirely correct. We created the disillusionment, and we have to find a way to solve it. I don’t pretend it is an easy job. As the book on the Chicago 1923 election said, ‘The disillusioned voter, who believes that one vote counts for nothing, presents a difficult problem of political control. The ignorant citizen can be informed, the indifferent citizen can be stirred out of his lethargy, but the sophisticated cynic of democracy cannot be moved so easily.’

So, where do we start? Is it enough to target the young and the poor, or do we need a broader, nationwide approach to restore people’s faith in the political process? One thing is certain – until we have won people’s trust back there is no way we can claim to live in a democracy. Democracy isn’t just about everyone having the potential to change the way society works. Democracy is about a state where precisely that happens, because people are confident that their opinions matter and that they can make a difference. In a country where over a quarter of citizens don’t exercise their right to choose the new government, and where the poorest have the least inclination to improve their lot, there can be little progress, only marginal improvement.

Politicians, for the most part, are not stupid. They have long been wise to the issue of public disaffection. What has baffled them is the solution. Previously, the tactic of all politicians across Parliament, has simply been to ‘try harder’. Knock on every door, so the logic goes, appear in every newspaper and on every television programme, telling people how important it is for them to get out and vote, and you can make a change.

In this age of all-pervasive media, it is clear that this tactic is not working. It is not because people aren’t aware of the key political issues of the day, or that they are ignorant about who the key politicians are, or what they stand for.

The problem is that we are working the wrong way round. This is the crisis facing politics: people aren’t interested in voting, because they see it as a lip-service to true democracy. Individuals, families, communities, villages, towns and regions still have scant authority, and while so much power is disproportionately centred around a distant government and a single capital, it is no surprise if people are unconvinced that their vote matters. People won’t turn out to vote for a new Prime Minister until they also have a chance to wield real power in their own backyards. Respect for government will only come about once people govern themselves.

And that’s where the solution must lie. The challenge is to build a truly civic Britain, where power has been devolved to the local and regional level, and where we are playing a full role in Europe. Where people no longer expect change to come slowly and inefficiently from Westminster, but have power within their own communities and exercise it themselves. Where the can-do culture tears down the walls built by decades of disillusionment and cynicism. Until politicians stop governing on behalf of the nation and start to govern with it, politics in Britain will remain what it is today – a sheer irrelevance for larger and larger numbers of people – and the consequences for the nation will be disastrous. It will be, in a sense, a final victory for Thatcherism. We will be a nation that prefers to lock the doors, rather than see what’s happening in the street outside.

It may seem inappropriate to speak of Thatcherism ten years after the end of the Iron Lady’s reign, but eighteen years of Tory rule wrought lasting damage upon the fabric of our society, and rather than repair it, Labour has sometimes been too willing to appease the middle classes at the expense of the poor. This is not new in politics – for forty years, J. K. Galbraith has been warning of the political dangers of the affluent disregarding the poor. Without doubt, the current government is a vast improvement on the previous one, but it is dangerous that Labour has not done more to create an environment that is sympathetic to the poor. In political life it means that we face nothing short of an emergency, but to those who already feel disheartened enough to stop reading, I want to point out that crises merely provide us with an opportunity to take action. The remedy is in our hands.

We can only make the most of the future if we are clear about what we want to achieve. My aim in politics is to advance and protect the liberty of the individual, because I believe that this is the only way to achieve true democracy. That, in turn, means ensuring that all people have the maximum life chances and the maximum opportunities to make the most of their natural abilities, whatever their circumstances. How can we speak of ‘democracy’ otherwise? Rule by the people (which is the precise definition of the word) does not mean that small privileged elites exercise their power over the rest. It means that everyone has an equal capacity to exercise power, and equal liberty to govern themselves.

In this book, I shall be using the word ‘liberty’ a great deal, along with its more popular counterpart, ‘freedom’. For me, politics is the machinery by which freedom is made possible. Freedom to breathe, in a safe and clean environment. Freedom from government, by devolving power to the communities, nations and regions of Britain. Freedom to innovate, and to trade with other nations. Freedom to develop one’s talents to the full, and to raise a family in security. None of these freedoms have any validity if the people enjoying them are not also free from poverty. This, and government’s responsibility to bring it about, is my starting point.

Chapter One (#ulink_2a6b4fa2-856f-51b3-8e61-873b99ccf7d8)

FREEDOM FROM POVERTY: THE FORGOTTEN NATION (#ulink_2a6b4fa2-856f-51b3-8e61-873b99ccf7d8)

‘True individual freedom cannot exist without economic security and independence. People who are hungry and out of a job are the stuff of which dictatorships are made.’

FRANKLIN D. ROOSEVELT, 1944

In my eighteen years as an MP, I have come to learn that the most effective politicians are those acting out of a very personal sense of injustice. I am often accused of being too rational, too reasonable, of rarely showing temper. This might be the case, but that does not mean I am not motivated by very clear and firmly held convictions, beliefs I have held since I entered the House at the age of twenty-three.

By then, I had witnessed the turmoil of the three-day week and the power cuts, and I was determined that people and government should never again be held to ransom in this way. I had also seen the disparity in incomes between some of the poorer families of my home town and the better-off workers who had migrated from the central belt of Scotland to work in the Corpach pulp and paper mill, which gave me a heightened awareness of inequality and its negative effects.

This crystallized when, as a teenager, I participated in the finals of the Scottish Schools Debating Tournament. For the first time, I came across people who were of my own age but from vastly different backgrounds. The disparity in outlook and aspiration between pupils from tough inner-city Glasgow comprehensives and those from fee-paying schools in Dundee and Edinburgh seemed remarkable to me. The wealthier participants were visibly more confident and outspoken, and carried themselves with self-assurance. I did not come from an impoverished background, but this was nevertheless the first time I had ever stayed in an hotel. I was awed by the experience, and this set me apart from other youngsters who treated the place as if it were an extension of their homes.

There was no difference in intelligence or eloquence – we were all gathered there because of our debating skills. But when you asked these teenagers what they wanted to do in later life, it became clear that those from poorer backgrounds expected less, and received it. They talked about ‘a job’, ‘a house’, whereas their more affluent counterparts had a very clear sense of what ‘profession’ they wanted and where they were going to live.

The experience was an eye-opener. It was, if you like, the beginnings of my sense of injustice. It gave me a determination to tackle the deep divisions within our society, which remains unabated to this day. Labour was once regarded as the party of social justice. The party believed in providing for the poorest, and that unarguable viewpoint was the party’s keynote, for many decades. It is safe to say that prior to the 1997 general election, few voters or even card-carrying members could have told you much about Labour’s foreign policy, or its attitude to European trade. They voted Labour and they contributed to its coffers because of its stand on social issues.

This does not mean that Britain should return to Old Labour policies. The dogma of class war, nationalization and tax-and-spend for the sake of it made a major contribution to many of the problems that Britain faces today. I want no part of any New Old Labour plan, yet in throwing out the worst of its past, New Labour has forgotten many of the people it should still be serving. As Mr Blair’s close ally, John Monks put it recently, New Labour seems to be treating some of its most loyal voters like ‘embarrassing elderly relatives’ at a family party.

(#litres_trial_promo) It was poignant that, on the night of the first vote to cut benefits in the new 1997 Parliament, Labour ministers supped champagne at Number 10 with a host of celebrities. Of course, had the politicians in question opted for tomato juice and an early night, the problems of Britain’s poor and dispossessed would not have vanished, but as a symbol of New Labour’s concerns, the juxtaposition was as symbolic as it was crass.

In an age where favourable media coverage and a carefully managed public image are lamentably as vital to a government as its policies, it was inevitable that we would see the Blairs hobnobbing with the Gallagher brothers and playing host to the stars of Cool Britannia. They can scarcely be reproached for that. Far more insidious is the growing body of evidence that suggests New Labour’s chief concern lies in courting the approval, and the votes, of Middle England, and that, simultaneously, it has lost interest in the poorest sections of society.

Take the slogan ‘education, education, education’: Tony Blair claims that equal access to a free and high quality education is paramount in dismantling the boundaries between rich and poor. I do not disagree, but if we assume the role of auditor for a moment, and look at two very different regions of England, we immediately see significant disparities. In Cornwall, 14.9 per cent of pupils are eligible for school meals, yet since May 1997 its schools have received only £308 per pupil through the system of competitive bidding, under which Local Education Authorities and schools have to apply to central government for funds. Rutland, by contrast, is one of Britain’s richest counties, with only 6.4 per cent of pupils eligible for school meals, yet it receives £1,006 per pupil. These figures suggest that the more disadvantaged areas of the UK are doing relatively badly when it comes to education funding, while the more comfortable, vocal and consequently more powerful regions grow even stronger. When the young people of Cornwall and Rutland compete in tomorrow’s job market such disparities will inevitably have knock-on effects.

A similar trend seems to be at work when we look at unemployment figures. Since Labour came into power, the biggest drops in unemployment have been felt by the most affluent constituencies. Conversely, between the years 1996 and 1999, the constituencies where unemployment fell the least were among the poorest. Constituency unemployment figures are not the most representative way of examining poverty as a whole, but these figures suggest that affluent communities have benefited more than poorer ones under New Labour. The two constituencies with the biggest improvement were in the most affluent region of the UK, the south-east, and the two seeing the least improvement were in Lancashire, in the second poorest region.

(#litres_trial_promo)

The government has over-trumpeted its successes in reducing unemployment. The National Institute of Social and Economic Research has concluded that of the 191,000 young people who have passed into jobs under the auspices of the New Deal since its launch in April 1998, 115,000 would probably have found work anyway, due to the strength and growth of the economy. The New Deal was Labour’s attack on unemployment, giving eighteen to twenty-four-year-olds who had been jobless for more than six months the opportunity to receive ‘in-job’ training, and offering employers incentives to give such people temporary work and training. After a four-month gateway period in which work is sought, there are various further options, including subsidized employment on short-time education and training. It marked a bold attempt to undermine the benefits culture and replace it with a work culture, but there is no point doing that when there is not enough work to go around.

In practice, the New Deal has turned out to be nothing more than a repackaging of the old Youth Training Scheme. Employers have benefited from a cheap source of temporary labour and cash sweeteners for using it, but in more than a fifth of cases, there were no real jobs for trainees to go to after the period had ended. Sixty per cent of the starters to the full-time education and training option had left by September 1999. Of the 191,000 ‘placed’ in work, at least 50,000 were back on benefits within three months of completing the scheme. The National Centre for Social Research has shown that only a quarter of New Deal leavers were continuously in employment for six months after completion of the scheme. Such figures indicate that little is being done to erode the benefits culture.

As with the boom in the eighties, there are plenty of social groups who have not benefited at all from the recent economic upturn. An estimated 1 million children live with parents who are both out of work. Labour’s policy has been to provide incentives for parents to take work, even if it is low-paid, but it is facing an uphill struggle. The British Household Panel Survey showed that between 1991 and 1997 only a quarter of couples with children who were out of work in any given year were able to find work a year later. The figure for lone parents was even more depressing – one in ten.

But there are large numbers of parents who do mini-jobs – that is, they work fewer than sixteen hours a week, which is the limit beyond which people cannot claim Income Support. The Institute for Social and Economic Research found that the more hours people put into these jobs, the more likely they were to secure a job offering more than sixteen hours work a week in the following year. It follows that government ought to be encouraging these small part-time jobs as a route into more full-time employment and out of poverty, but we still have a punitive benefits system, the principles of which have not altered for decades. People have to declare every change in their part-time earnings – even though many such jobs are ad hoc. People can also only earn between £5 and £15, depending on their circumstances, before money is deducted from their benefit. All this discourages people from taking any job that is less than full time, regardless of the opportunities it may lead to later.

In its failure to think flexibly it is no worse than previous governments, but no better either. Labour appears prepared to understand work only in terms of the traditional model of nine to five, five days a week, and benefits in terms of a weekly sum of money. And because it has stuck by this rigid perspective, people are losing out. For example, under the present system, unemployed people receive a weekly sum of money and, on top of that, a few entitlements, such as free eye check-ups and prescriptions. As soon as they stop receiving weekly benefit, the other benefits cease as well, meaning that even though they are working, they may be worse off than when they were entirely dependent upon benefits. Instead, people working a few hours a week, and all people on low incomes, should retain a range of entitlements, such as subsidized transport, free prescriptions and milk, so that they have incentives to enter and then remain within the world of work.

In 1996, Tony Blair said, ‘If the Labour government has not raised the standards of the poorest by the end of its time in office, it will have failed.’ Mr Blair made the pursuit of equality a key feature of his agenda – I do not argue with the depth and sincerity of his conviction – but the fact remains that, back in 1996, this was a subject of immediate contemporary concern. New Labour were characteristically astute in capturing the mood of the nation. It is still an important issue in the nation’s eyes, but it would be even more so if the government made a crusade of the issue.

It is easy to see why it was such a public preoccupation. In 1992, an estimated 13.7 million people were living on breadline benefit or on half the average wage. This amounted to one quarter of the population of Britain. UNICEF warned that Britain’s children were the worst off in Europe. By 1994, 4.2 million – roughly one third – of the children in Britain belonged to families living below the poverty line. Meanwhile, the gap between rich and poor had widened. By 1994, the wealthiest 5.5 million people in GB (i.e. the richest 10 per cent) were an average £650 better off for every thousand pounds they had earned in 1979. But the poorest ten per cent were worse off. For every £1,000 they had had in 1979, they now had £860.

(#litres_trial_promo)

Unfortunately, it takes more than three budgets and a New Deal to reverse major trends like these, and undo the damage already caused – benefit cuts were almost the hunting cry of the Tory party in the 1980s. The most vulnerable sections of the nation are still suffering them under Labour. Anyone who receives invalidity benefit and has a modest private pension (£85 a week or more) will lose benefit at a rate of 50p in the pound. Severe disablement allowance has also been abolished, placing many severely handicapped people below the poverty line. The state pension was 20 per cent of the average income in the early eighties. It has now fallen to 15 per cent and is still falling. The government’s answer was to make a derisory change which amounts to 75p a week for the average single pensioner. Meanwhile, a study by the University of Kent has shown that half those over eighty are surviving on less than £80 a week. Pensioners, distressed at their treatment under the present government, are among the most regular and vocal contributors to my daily postbag.

We can also see how little things have improved for the poor when we examine public health. Areas such as Glasgow, Newcastle-upon-Tyne and Liverpool have premature death rates more than twice those in affluent southern counties like Buckinghamshire and Berkshire. Within London, poor boroughs such as Woolwich have premature death rates twice as high as wealthy boroughs like Kensington and Chelsea, as well as disproportionately high rates of asthma, eczema, heart disease and depression.

The urban poor face unique sets of problems which Labour is doing little to address or even understand. A 1999 University of Glasgow study pointed out that Britain’s twenty major cities have been hardest hit by unemployment. The decline of manufacturing industries has led to huge numbers of male manual workers being put out of their traditional employment. The report indicated that the cities had lost nearly a quarter of their 1981 stock of full-time male jobs by 1996 – equivalent to over 500,000 jobs – and these people are not going on to find work elsewhere. The service industry, it is often said, is expanding, but it is, according to the study, doing so least in our cities. The decline in skilled manual jobs has, on the whole, resulted in downward movement for most urban men into unskilled, lower-paid jobs, or into unemployment, casual work and the black economy.

(#litres_trial_promo) The upshot is that there is a massive jobs gap in our cities – that is, large numbers of men able to work, and no jobs for them to go to.

Labour’s current policies are directed towards equipping the urban unemployed with more skills and motivating them to find work. All this is totally missing the point. In the words of the study’s authors: ‘national economic and social policies need to give greater emphasis to expanding labour demand in the cities’. Of course, training and motivation are vital – but they are pointless when there are no jobs for people to go into.