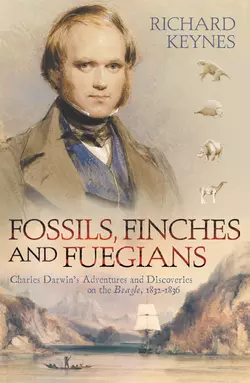

Fossils, Finches and Fuegians: Charles Darwin’s Adventures and Discoveries on the Beagle

Richard Keynes

A narrative account of Darwin’s historic 4-year voyage on the Beagle to South America, Australia and the Pacific in the 1830s that combines the adventure and excitement of Alan Moorehead’s famous (and now out of print) account with an expert assessment of the scientific discoveries of that journey. The author is Charles Darwin’s great-grandson.• In his autobiography, Charles Darwin wrote: ‘The voyage of the Beagle has been by far the most important event in my life and has determined my whole career; yet it depended on so small a circumstance as my uncle offering to drive me 30 miles to Shrewsbury, which few uncles would have done, and on such a trifle as the shape of my nose. I have always felt that I owe to the voyage the first real training or education of my mind. I was led to attend closely to several branches of natural history, and thus my powers of observation were improved, though they were already fairly developed. The investigation of the geology of all the places visited was far more important, as reasoning here comes into play.’No biography of Darwin has yet done justice to what the scientific research actually was that occupied Darwin during the voyage. Keynes shows exactly how Darwin’s geological researches and his observations on natural history sowed the seeds of his revolutionary theory of evolution, and led to the writing of his great works on The Origin of Species and The Descent of Man.

Copyright (#ulink_1d209996-21c4-5573-81dd-6dc13b889eb4)

HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd.

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

First published in Great Britain by HarperCollinsPublishers 2002

Copyright © Richard Keynes 2002

Richard Keynes asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the nonexclusive, nontransferable right to access and read the text of this ebook on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse-engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins ebooks

HarperCollinsPublishers has made every reasonable effort to ensure that any picture content and written content in this ebook has been included or removed in accordance with the contractual and technological constraints in operation at the time of publication

Source ISBN: 9780007101900

Ebook Edition © FEBRUARY 2017 ISBN: 9780007571673

Version: 2017-08-09

Dedication (#ulink_4f487734-1f70-5048-be1c-b8ae24264658)

To my mother

Contents

Cover (#u5e6d78a4-4068-5be7-b551-6b88a79d94fb)

Title Page (#ueba14183-aa64-5f7e-9581-919db15a45e2)

Copyright (#ulink_87ff12c2-3937-5045-a3cb-551f3e2ca8ad)

Dedication (#ulink_47eb6b10-bb23-578d-acc7-f724ae348c90)

List of Maps (#ulink_024c084a-3ab4-5337-a557-01b82e27072f)

Prologue (#ulink_1349cc1e-b869-55fd-b0bd-e4c82801613a)

1 The Man who Walks with Henslow (#ulink_880829b4-cf95-54fc-9a24-6c1d3ca373c9)

2 The Strange Consequences of Stealing a Whale-Boat (#ulink_4249a09b-650b-56f1-bead-a3f150d5cbb3)

3 Preparations for the Voyage (#ulink_d6658098-d633-52cd-a65e-5240f7805c6c)

4 From Plymouth to the Cape Verde Islands (#ulink_ce3a2bea-2ae7-5a3c-ba1e-4e91e7692817)

5 Across the Equator to Bahia (#ulink_5b7b8f27-d455-5929-b094-602ebd65ecb7)

6 Rio de Janeiro (#ulink_fb0cc436-cfd5-5c2e-aee6-31db5e49607f)

7 An Unquiet Trip from Monte Video to Buenos Aires (#ulink_ca637196-759c-5ead-bf3e-7727911c036e)

8 Digging up Fossils in the Cliffs at Bahia Blanca (#ulink_b943086f-a260-5975-8881-915becf345dd)

9 The Return of the Fuegians to Their Homeland (#litres_trial_promo)

10 First Visit to the Falkland Islands (#litres_trial_promo)

11 Collecting Around Maldonado (#litres_trial_promo)

12 A Meeting with General Rosas on the Ride from Patagones to Buenos Aires and Santa Fé (#litres_trial_promo)

13 The Last of Monte Video (#litres_trial_promo)

14 Christmas Day at Port Desire, and on to Port St Julian and Port Famine (#litres_trial_promo)

15 Goodbye to Jemmy Button and Tierra del Fuego (#litres_trial_promo)

16 Second Visit to the Falkland Islands (#litres_trial_promo)

17 Ascent of the Rio Santa Cruz (#litres_trial_promo)

18 Through the Straits of Magellan to Valparaiso (#litres_trial_promo)

19 Valparaiso and Santiago (#litres_trial_promo)

20 Chiloe and the Chonos Archipelago (#litres_trial_promo)

21 The Great Earthquake of 1835 Hits Valdivia and Concepción (#litres_trial_promo)

22 On Horseback from Santiago to Mendoza, and Back Over the Uspallata Pass (#litres_trial_promo)

23 A Last Ride in the Andes, from Valparaiso to Copiapó (#litres_trial_promo)

24 The Wreck of HMS Challenger (#litres_trial_promo)

25 From Copiapó to Lima (#litres_trial_promo)

26 The Galapagos Islands (#litres_trial_promo)

27 Across the Pacific to Tahiti (#litres_trial_promo)

28 New Zealand (#litres_trial_promo)

29 Australia (#litres_trial_promo)

30 Cocos Keeling Islands (#litres_trial_promo)

31 Mauritius, Cape of Good Hope, St Helena and Ascension Island (#litres_trial_promo)

32 A Quick Dash to Bahia and Home to Falmouth (#litres_trial_promo)

33 Harvesting the Evidence (#litres_trial_promo)

34 Farewell to Robert FitzRoy (#litres_trial_promo)

Epilogue (#litres_trial_promo)

Notes (#litres_trial_promo)

Index (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

Other Books By (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

Maps (#ulink_79a76f7f-c92a-552e-a653-ee8c59fa5052)

The Voyage of the Beagle (#ulink_5b1e1451-43b2-50d5-bf59-ffae00a12fb4)

Geological map of part of North Wales (#ulink_b7da42b2-9bf2-56ab-ab44-c4a72aa3051a)

Tierra del Fuego (#ulink_291d9b7f-f86d-50a6-8b2c-86f8774ea622)

Charles’s Eight Principal Inland Expeditions in South America (#litres_trial_promo)

Port San Julian (#litres_trial_promo)

The Straits of Magellan (#litres_trial_promo)

West Coast of Chile (#litres_trial_promo)

The Galapagos Islands (#litres_trial_promo)

North and South Keeling Islands (#litres_trial_promo)

(#ulink_64e01e66-32e7-526c-a424-f8e96cdb99e6)

(#ulink_64e01e66-32e7-526c-a424-f8e96cdb99e6)

Prologue (#ulink_1c5c9889-45d6-5ae8-821f-2889c8731abf)

In the autobiography written by Charles Darwin near the end of his life for the benefit of his children and descendants,

(#litres_trial_promo) he said:

The voyage of the Beagle has been by far the most important event in my life and has determined my whole career; yet it depended on so small a circumstance as my uncle offering to drive me 30 miles to Shrewsbury, which few uncles would have done, and on such a trifle as the shape of my nose. I have always felt that I owe to the voyage the first real training or education of my mind. I was led to attend closely to several branches of natural history, and thus my powers of observation were improved, though they were already fairly developed.

There is no dispute with Darwin’s own estimate of the importance of the voyage of the Beagle in the subsequent development of his scientific career. He himself provided a classical description of the voyage in his Journal of Researches,2 but his biographers other than Janet Browne have not covered his scientific research on the Beagle in much detail, while Alan Moorehead’s Darwin and the Beagle3 was mainly concerned with the affair as the exciting adventure that it undoubtedly was, and gave a distinctly misleading picture of the relations between Darwin and FitzRoy. The purpose of this book is to retell the whole story, starting from the haphazard events in Tierra del Fuego that led Robert FitzRoy to take the Beagle there again, with a ‘well-educated and scientific person’ as companion. Then it is shown how FitzRoy’s scientist had precisely the right talents to make highly effective use of the array of new scientific facts that were presented to him in South America and in the countries visited by the Beagle homeward bound round the far side of the world. And lastly it is explained how Charles Darwin’s findings on the Beagle soon started him on the path that in due course led him to the discovery of the principle of Natural Selection and of the Origin of Species.

My interest in South America was first aroused in 1951, when I had the good fortune to be invited by Professor Carlos Chagas Filho to be Visiting Reader that summer at the Instituto de Biofisica in Rio de Janeiro. My ignorance about Brazil was profound, but I did know that Professor Chagas had a good supply of electric eels at his laboratory. Moreover, Alan Hodgkin, leader of our group working at the Physiological Laboratory in Cambridge on the mechanism of conduction of the nervous impulse, had just developed an important new technique for recording electrical activity in living cells that I could usefully apply to investigate the properties of what Charles Darwin had described as the ‘wondrous’ organs

(#litres_trial_promo) in certain fishes that generated their powerful electrical discharges, though he had been puzzled about the manner of their evolution. So I spent two and a half happy months in Rio that summer, successfully unravelling the mystery of how the additive discharge of the electric organ was achieved.

(#litres_trial_promo) The job complete, and having accumulated a pocketful of cruzeiros in payment for my efforts, I then took the recently established direct flight in a Braniff DC-6 from Rio to Lima over the Mato Grosso and the Andes, and made the first of many journeys to Peru, briefly calling on fellow physiologists in Chile and Argentina on the way home, and getting back to Cambridge for the Michaelmas term at the beginning of October.

In August 1968 I had been visiting a Chilean colleague at Viña del Mar, near Valparaiso, for discussions on a joint study of the biophysics and physiology of giant nerve fibres, and was flying home via Buenos Aires. Here the British Council representative, knowing me to be a member of the Darwin family, asked me whether I had seen the Darwin collection belonging to Dr Armando Braun Menendez. I had not previously taken any particular interest in the voyage of the Beagle, but fortunately the Argentinian professor who was showing me round knew Dr Braun Menendez, and took me to call on him. His impressive collection of papers and books was concerned with the exploration of the southern seas, and the Darwin item consisted of two little portfolios of pencil drawings and watercolours made on board the Beagle by Conrad Martens, of whom I knew vaguely as the second of the ship’s official artists. I opened one of the portfolios to find the picture labelled by Martens as ‘Slinging the monkey. Port Desire – Decr 25, 1833’, which portrayed the ship’s crew engaged on the Royal Navy’s traditional celebration of Christmas Day, with the Beagle and Adventure anchored in the background. The picture bore the initials ‘RF’ at the top right-hand corner, though the Beagle’s Captain, Robert FitzRoy, evidently did not approve of every detail, because Martens had written below: ‘Note. Mainmast of the Beagle a little farther aft – Miz. Mast to rake more’. This graphic document, and others in the portfolios, opened an exciting new window for me on to the voyage of the Beagle, and launched me on an entirely new and rewarding field of part-time study.

On my return home, I consulted Nora Barlow, my godmother and mentor, and like my mother a granddaughter of Charles Darwin. Through her pioneer editions of Charles Darwin’s Diary of the Voyage of H.M.S. “Beagle” (1933), Charles Darwin and the Voyage of the Beagle (1945), Darwin’s Autobiography (1958), his Ornithological Notes (1963), and Darwin and Henslow: The Growth of an Idea. Letters 1831–1860 (1967), Nora Barlow was the true founder of what is often known nowadays as the Darwin Industry. Her wisdom and kindness had no bounds, and my debt to her is immense.

With Lady Barlow’s encouragement, I set about assembling a catalogue of all the extant drawings and paintings made by Conrad Martens during his initial journey from England to Montevideo, where on 3 August 1833 he joined the Beagle as a replacement for the ship’s first official artist, Augustus Earle, who had been taken ill. Then I listed the drawings and paintings that he made in Patagonia, Tierra del Fuego, the Falkland Islands, the Straits of Magellan, Chiloe and around Valparaiso, until in December 1834, there being no longer any space for him on the Beagle, he set sail for Australia. Here he established himself in Sydney as the leading artist of the period, and at the same time continued to paint developments of his Beagle drawings in watercolour, some of which he sold to Darwin, and others to Robert FitzRoy to be engraved as illustrations for the published accounts of the voyage. Selections from this material were reproduced in the first book that I edited, The Beagle Record (1979), to illustrate some of the places and people actually seen by Darwin and FitzRoy in South America. For the most immediate written records, I drew upon the vivid accounts in letters from Darwin to his sisters and to his mentor in Cambridge, Professor John Stevens Henslow, and also in what he himself called his ‘commonplace journal’, but which will be referred to here as the ‘Beagle Diary’ to distinguish it from his subsequently published Journal of Researches. In addition I made use of FitzRoy’s published account,

(#litres_trial_promo) his few surviving diaries, and some of his letters.

Fifty years after its publication, Nora Barlow’s edition of The Beagle Diary had long since gone out of print. Darwin’s splendid description of his daily life on the Beagle and ashore, sent home at intervals to his family in Shrewsbury, is one of the major classics of scientific exploration. My next task was therefore to produce a new version revised according to modern standards of transcription, with Nora Barlow’s very rare errors put right, and a new introduction and footnotes. This was published in 1988, and has recently been reprinted in paperback.

(#litres_trial_promo)

Two substantial Darwin manuscripts still remained unpublished at the Cambridge University Library, namely the Zoology Notes

(#litres_trial_promo) and the Geology Notes

(#litres_trial_promo),

(#litres_trial_promo) made on the Beagle. Apart from a brief account of some observations made in Edinburgh in 1827,

(#litres_trial_promo) these were his first scientific writings, containing a detailed record of all that he observed and collected during the four-and-three-quarter years of the voyage. Their importance is that here, and in his letters to Henslow,

(#litres_trial_promo) it is possible to trace the first beginnings of Darwin’s thinking about the evolution not only of the animal kingdom but also of the face of the earth.

After retiring in 1986 from administration and teaching in Cambridge, I had more time at my disposal, so in addition to visiting the marine laboratory at Roscoff in Brittany every autumn for continuation of some experimental work, I embarked on a transcription

(#litres_trial_promo) of Darwin’s Zoology Notes and Specimen Lists. They comprise some hundreds of quarto pages of notes, with descriptions of 1500 specimens preserved in Spirits of Wine, and some 3500 not in Spirits. In order to identify the insects and marine invertebrates collected by Darwin, I needed a great deal of help from experts on their taxonomy, but the vertebrates had mostly been covered in the five parts of The Zoology of the Voyage of H.M.S. Beagle published in 1839–1843.

(#litres_trial_promo) Completion of the task has kept me busy for about ten years, but it has now at last been finished. The Geology Notes have not as yet been transcribed and published, occupying as they do around four times as many pages as the Zoology Notes. However, articles by Secord,

(#litres_trial_promo) Herbert

(#litres_trial_promo) and Rhodes

(#litres_trial_promo) have discussed them helpfully, as has Janet Browne’s account of the voyage.

(#litres_trial_promo) Moreover, photocopies of the MSS are available at the Cambridge University Library for study by anyone well practised at reading Darwin’s reasonably legible handwriting.

If any of my readers feel that they would like to become better acquainted with one of their forebears, I can recommend the course that I adopted thanks to that chance introduction in Buenos Aires in 1968. When you have transcribed several hundred thousand words of his writings, concerned with places a few of which you have seen for yourself not too greatly changed 160 years later, you may once in a while almost feel that you are talking to him. But it helps to be lucky enough to have a forebear who was as friendly to all men, and as constructively critical and honest about his own ideas, as Charles Darwin always was.

Richard Darwin KeynesCambridge, July 2001

CHAPTER 1 (#ulink_acf9e19a-7edc-5ba8-b5d0-c471033e8bef)

The Man who Walks with Henslow (#ulink_acf9e19a-7edc-5ba8-b5d0-c471033e8bef)

Charles Robert Darwin was born at The Mount, Shrewsbury, on 12 February 1809, the second son and fifth child of Dr Robert Waring Darwin.

His genetic make-up in the male line was strongly scientific, although his father combined a position as one of the leading physicians in the Midlands not with science, but with acting widely as a private financial adviser to the gentry of the region. Charles would later have high praise for his father’s powers of observation, and for his sympathy with his patients, but considered that his mind was not truly scientific. Robert’s wealth was nevertheless as valuable an inheritance for his son as a gene for science, not only paying for Charles’s board and lodging on the Beagle when he sailed as an unofficial scientist and companion to the Captain, but also enabling him to pursue a scientific career single-mindedly for the rest of his life, without ever having to earn his living.

However, his grandfathers, Dr Erasmus Darwin of Lichfield and Josiah Wedgwood I the potter, who built a model factory at Etruria near Stoke-on-Trent, were two of the leading scientists and technologists of their time. Both Fellows of the Royal Society, they were also founding members of the Lunar Society of Birmingham, which played the principal intellectual part in the establishment of the Industrial Revolution in England. Erasmus Darwin

(#litres_trial_promo) was primarily a practising physician, but his prodigious energies overflowed in many other directions, as a poet, an inventor of mechanical devices of various kinds, a pioneer in meteorology and in the description of photosynthesis, and not least as author of an immense medical treatise entitled Zoonomia,* and of a fine poem, The Temple of Nature, in which as we shall see he made an important contribution to his grandson’s Theory of Evolution. Josiah Wedgwood I made radical improvements in the handling of china clay, founded a famous pottery, and developed a canal system for the transport of his products. The chemists of Europe came to him for their glassware and retorts, and in due course his son Josiah Wedgwood II provided his nephews Erasmus and Charles with fireproof china dishes manufactured at the pottery, and an industrial thermometer for their private laboratory.

Charles recorded that at a very early age he had a passion for collecting ‘all sorts of things, shells, seals, franks, coins, and minerals … which leads a man to be a systematic naturalist, a virtuoso or a miser’. Throughout his life he also exercised a scientifically useful taste for making careful lists, whether of his various collections, of the game that he had killed, of books that he had read or intended to read, of the pros and cons of marriage, or of his household accounts.

During his formal education at Shrewsbury School, where like his elder brother Erasmus he boarded for some years, he was taught mainly classics, ancient geography and history, and a little mathematics, but there was no place for science in the curriculum. However, their grandfathers’ strong interest in chemistry managed to break through in both boys, first in Erasmus and then in Charles, and together they set up in an outhouse at home what they grandly called their ‘Laboratory’. Here they could pursue a hobby fashionable at the time in the upper classes for investigating the composition of various domestic materials, sometimes after purification of their constituents by crystallisation, though they were seldom able to extract sufficient funds from their father to provide any really sophisticated chemical apparatus. For a while the application of elementary crystallography to his collection of rocks and stones was one of Charles’s favourite occupations.

In 1822 Erasmus left school, and was sent to study at Cambridge, where he wrote a helpful series of letters to Charles with detailed instructions for further experiments. This encouraged Charles to examine the effect on different substances of heating them over an open flame, sometimes with a blow-pipe at the gaslight in his bedroom at school, earning him the nickname of ‘Gas’ and the strong disapproval of the headmaster. Over this period, Charles delighted in devising simple instruments for performance of his tests, and under the tuition of Erasmus served a useful initial apprenticeship in the art of scientific experimentation.

Robert Darwin now decided that Erasmus should proceed from Cambridge to Edinburgh University as he had done himself in order to take an M.B. degree, and that Charles should leave school at the age of sixteen and accompany his brother to Edinburgh in October 1825 with the same object. The plan did not quite work out, for although Erasmus did eventually pass the Cambridge M.B. exam in 1828, his poor health led to his retirement to London as a gentleman of leisure, and he never practised. Charles, on the other hand, having signed up for the traditional courses on anatomy, surgery, the practice of physic, and materia medica, the remedial substances used in medicine, which his father and grandfather had taken in their day, soon found that many of the lectures were now sadly out of date, and that conditions in the dissecting room and on two occasions in the operating room were so highly distasteful that he felt unable to continue on the course. It was not until the end of his second year that he was at last able to confess to his father his determination to abandon medicine as a career, but in the meantime Edinburgh provided other avenues to fill his time that assisted materially in his development as a scientist.

During his first year at Edinburgh, Charles took regular walks with Erasmus on the shores of the Firth of Forth, where he made his first acquaintance with some of the marine animals that later occupied him so intensively on the Beagle. At the same time he maintained his interest in ornithology, and arranged to have lessons on stuffing birds from a ‘blackamoor’ who had been taught taxidermy by the naturalist Charles Waterton. He and Erasmus also revived their knowledge of chemistry and related areas of geology by attending the stimulating lectures and demonstrations given by Thomas Charles Hope, Professor of Chemistry in the university from 1799 to 1843.

In 1826, Erasmus had remained at home, and Charles was left to fend for himself. He attended Robert Jameson’s popular series of extracurricular lectures covering meteorology, hydrography, mineralogy, geology, botany and zoology, but said many years later that ‘they were incredibly dull. The sole effect they produced on me was the determination never as long as I lived to read a book on Geology or in any way to study the science.’ Although it was true that Jameson’s style of lecturing did not inspire his audience, Charles’s copy of Jameson’s Manual of Mineralogy is heavily annotated, and provided him with a valuable source of practical information for his subsequent geological studies. He also benefited from exposure to the critical clash between Hope’s Huttonian views and Jameson’s preference for the Wernerian doctrine,

(#litres_trial_promo) soon coming down firmly on Hope’s side. In any case, any temporary prejudice that Charles may have had against geology did not last long, and in due course was banished by Professors Henslow and Sedgwick after his arrival at Cambridge.

In November, Charles became a member of the Plinian Society, named after Pliny the Elder, author of a famous account of the natural history of ancient Rome, at which a small group of undergraduates would meet informally for discussions of natural history or sometimes to go on collecting expeditions, but from participation in which the university professors were traditionally banned. He was also taken as a guest from time to time to the august Wernerian Society, whose membership was restricted to graduates, and whose proceedings were published in a series of learned memoirs. At a meeting of the Wernerian Society on 16 December 1826, he listened attentively to a paper on the buzzard in which the great American ornithologist and artist John James Audubon, who had recently arrived in Edinburgh to find an engraver for the first ten plates of his Birds of America, exploded the currently fashionable view of the extraordinary power of smelling possessed by vultures. When nine years later Charles was making observations in Chile on the behaviour of condors, he was happy to find himself in agreement with Audubon’s conclusions.

The senior member of the Plinian Society was at that time Robert Grant, then aged thirty-three and a mere lecturer on invertebrate animals at an extramural anatomy school, who had graduated as a doctor in 1814, travelled extensively on the Continent, and studied in Paris with the zoologist and anatomist Georges Cuvier (1769–1832). Soon Charles was taken by Grant to collect a variety of animals along the shores in the neighbourhood of Leith, and to go out with fishermen on the waters of the Firth of Forth. On these trips he was sometimes accompanied by another medical student, John Coldstream, who later advised him helpfully about fishing nets. Grant also taught Charles how to dissect specimens under sea water with the aid of a crude single-lens microscope, and gave him a valuable training in marine biology, with an emphasis on the importance of developmental studies on invertebrates, which was taken up with enthusiasm by a pupil who all too quickly outshone his master.

Among Grant’s favourite subjects for research were the not very glamorous ‘moss animals’ of genus Flustra that encrusted the tidal rocks in bunches like a miniature seaweed, and which consisted of large numbers of microscopic polyps whose precise relationship with one another was unclear. There had long been controversy as to whether they should be classified as animals or plants, and the Swedish botanist and founder of the system of binomial nomenclature of species Carl Linnaeus (1707–78) had christened them Zoophyta, an intermediate form. By the beginning of the nineteenth century it had been widely but not yet universally accepted that these organisms were indeed sedentary aquatic animals, which formed colonies often containing millions of individual polyps or zooids with specialised functions. In 1830 the phylum

(#litres_trial_promo) to which they belonged was termed Polyzoa by J. Vaughan Thompson, and nowadays the animals are classified as Bryozoa.

Charles set to work on the reproductive particles of Flustra and other marine animals, and to his great excitement confirmed Grant’s observation that the eggs of Flustra were coated with fine cilia, hairlike vibrating organs whose coordinated movements endowed the ova with some degree of motility. He also noted that the ‘sea peppercorns’ often found attached to old shells were not as previously assumed buttons of seaweed, but were the eggs of the marine leech Pontobdella muricata. This he duly reported in his first scientific paper, presented in a talk to the Plinian Society on 27 March 1827; but he had been seriously put out when three days earlier Grant read a long memoir to the Wernerian Society that included his pupil’s findings without any proper acknowledgement of their source. What had happened was later described by Charles’s daughter Henrietta:

When he was at Edinburgh he found out that the spermatozoa [ova] of things that grow on seaweed move. He rushed instantly to Prof. Grant who was working on the same subject to tell him, thinking, he wd be delighted with so curious a fact. But was confounded on being told that it was very unfair of him to work at Prof. G’s subject and in fact that he shd take it ill if my Father published it. This made a deep impression on my father and he has always expressed the strongest contempt for all such little feelings – unworthy of searchers after truth.

(#litres_trial_promo)

At around the same time, as Charles recalled long afterwards, he had a significant conversation with Grant:

He one day, when we were walking together, burst forth in high admiration of Lamarck and his views on evolution. I listened in silent astonishment, and as far as I can judge, without any effect on my mind. I had previously read the Zoonomia of my grandfather, in which similar views are maintained, but without producing any effect on me. Nevertheless it is probable that the hearing rather early in life such views maintained and praised may have favoured my upholding them under a different form in my Origin of Species. At this time I admired greatly the Zoonomia; but on reading it a second time after an interval of ten or fifteen years, I was much disappointed, the proportion of speculation being so large to the facts given.

(#litres_trial_promo)

When in 1793 Jean Baptiste Pierre Antoine de Monet de Lamarck was appointed as Professor of the ‘inferior animals’ in Paris, he earned good marks for renaming them in a less uncomplimentary fashion as ‘invertebrates’, i.e. animals without backbones. He also came up with new and valid reasons for believing in the evolution of new species. But he then spoiled his case by endowing all animals with a special power to interact directly with their environment and acquire ever greater complexity or perfection, supposing for example that the length of a giraffe’s neck was the result of the animal constantly reaching up for food, or that the length of an anteater’s nose and loss of its teeth resulted from perpetual sniffing into anthills, and was inherited over many generations. In the absence of any good evidence for such an inheritance of acquired characteristics, the term ‘Lamarckian’ soon had pejorative connotations. The occasion to which Charles referred was possibly the first when Grant revealed his extreme views on transmutation in invertebrates, and metamorphoses in extinct fossils. At the end of 1827 Grant became the first Professor of Zoology and Comparative Anatomy at University College London,

(#litres_trial_promo) and his strongly Lamarckian approach was more widely disseminated. He held this post until his retirement in 1874, and though he was reported by Charles’s friend Frederick William Hope in 1834 to be ‘working away at the Mollusca & Infusoria publishing at a great rate’, in 1867 he was still teaching a defunct 1830s zoology in a frayed swallow-tail coat. Charles later noted that ‘he did nothing more in science – a fact which has always been inexplicable to me’. Grant’s excessively radical attitude, coupled with the disillusionment stemming from their falling out that March, may help to explain why their subsequent relations were never close, and there is no suggestion that Charles was ever subjected to the intimate approaches from Grant that may eventually have led to the nervous breakdown suffered by another of his students, John Coldstream.

Robert Darwin was far from pleased with Charles for giving up medicine, and told him angrily, and as Charles thought somewhat unjustly, ‘You care for nothing but shooting, dogs and rat-catching and you will be a disgrace to yourself and all your family.’

(#litres_trial_promo) After careful consideration, Robert decided that the only alternative for which there were several precedents in the Darwin and Wedgwood families would be for Charles to go up to Cambridge to take an ordinary Arts degree as the first step towards becoming an Anglican clergyman. In order to fulfil in due course the requirements for entry into the university, he had to brush up the Latin and Greek that he was supposed to have learnt at school, and a private tutor was therefore engaged for the last eight months of 1827. The period was not a very happy one for Charles, though he managed to escape to Uncle Josiah Wedgwood’s house at Maer Hall in Staffordshire, seven miles from Stoke-on-Trent, for at least the start of the shooting season, and made his first and only visit to France to collect his youngest Wedgwood cousins from Paris. But he did not record whether he also fitted in a visit to Cuvier’s famous Musée d’Histoire Naturelle.

Charles duly matriculated at Christ’s College, Cambridge, in January 1828. Here he quickly fell in with a new circle of young men from his own background and sharing his own tastes, one of whom described him at the time as ‘rather thick set in physical frame & of the most placid, unpretending & amiable nature’. Some years later, Charles advised his eldest son William at school:

You will surely find that the greatest pleasure in life is in being beloved; & this depends almost more on pleasant manners, than on being kind with grave & gruff manners. You are almost always kind & only want the more easily acquired external appearance. Depend upon it, that the only way to acquire pleasant manners is to try to please everybody you come near, your school-fellows, servants & everyone. Do, my own dear Boy, sometimes think over this, for you have plenty of sense & observation.

(#litres_trial_promo)

Charles’s own amiability and good relations with the rest of the world at every level were always among his most outstanding characteristics, and he had a true genius for friendship.

His new acquaintances included a number of schoolmates from Shrewsbury, and his cousin Hensleigh Wedgwood from Staffordshire, who had earlier seen a lot of Charles’s brother Erasmus in Cambridge. By far his closest friend to begin with was a cousin from the other side of the family, William Darwin Fox, the only son of Robert Darwin’s cousin Samuel Fox, who was then in his third year at Christ’s and due to become a parson in Cheshire. William Darwin Fox’s abiding passion, just as Charles’s had been in his childhood, was for the collection of exotic natural history specimens that filled every cubic inch of his rooms. He took great pleasure in shooting and riding, and kept two dogs named Fan and Sappho at Christ’s, about whose exploits, matching that of Charles’s Mr Dash at Shrewsbury, they had a regular correspondence. Fox encouraged Charles to take an interest in both art and music, and together they visited print shops and the Fitzwilliam Museum, and attended concerts of choral works in college chapels. Charles later joined a musical set headed by another good friend, John Maurice Herbert.

(#litres_trial_promo) They went regularly to King’s College chapel to hear the anthem sung, and occasionally Charles hired the choristers to perform in his rooms. But as Herbert soon discovered, and as he himself freely admitted, Charles’s pleasure in listening was not in fact accompanied by a good musical ear. The interests of the group were wide-ranging, and extended at one time to the formation of the ‘Glutton’ or ‘Gourmet’ Club at which they dined when not eating in hall, and consumed a range of animals that did not usually appear on the menu. The club was finally brought to an end by an attempt to eat an old brown owl whose flavour was considered by all to have been ‘indescribable’. One wonders what the club would have made of some of the weird dishes later consumed in an experimental spirit by Charles on the Beagle.

The principal and most time-consuming occupation to which Charles was introduced by Fox was collecting and learning to identify beetles. Charles recalled later:

No pursuit at Cambridge was followed with nearly so much eagerness or gave me so much pleasure as collecting beetles. It was the mere passion for collecting, for I did not dissect them and rarely compared their characters with published descriptions, but got them named anyhow. I will give a proof of my zeal: one day, on tearing off some old bark, I saw two rare beetles and seized one in each hand; then I saw a third and new kind, which I could not bear to lose, so that I popped the one which I held in my right hand into my mouth. Alas it ejected some intensely acrid fluid, which burnt my tongue so that I was forced to spit the beetle out, which was lost, as well as the third one. I was very successful in collecting and invented two new methods; I employed a labourer to scrape during the winter, moss off old trees and place [it] in a large bag, and likewise to collect the rubbish at the bottom of the barges in which reeds are brought from the fens, and thus I got some very rare species. No poet ever felt more delight at seeing his first poem published than I did at seeing in Stephen’s Illustrations of British Insects the magic words, “captured by Charles Darwin, Esq.”

(#litres_trial_promo)

Public interest in natural history was at that time about to expand hugely, but few people pursued the new hobby with the passion, practical competence and competitiveness displayed by Fox and Charles. After breakfasting together daily, they scoured the fields and ditches closest to them at the ‘backs’ of the colleges, and the countryside further to the south of Cambridge, often accompanied by a bagman to carry their heavier equipment and their captures. When this man had learnt just what they were after, he would also collect for them when they were otherwise occupied. Returning to Charles’s rooms they would go through his reference books, from Lamarck to Stephens, to identify any rarities they had secured, and pin them out on a board for all to admire. On one such occasion after Charles had, after a ‘famous chace’ in the Fens, caught an especially rare beetle, he was pleased when Leonard Jenyns, vicar of Swaffham Bulbeck, and one of his principal collecting rivals in Cambridge, quickly came round to inspect it. Some years later, it was Jenyns who identified the fishes brought back by Charles in the Beagle.

When in June 1828 Fox went down from Cambridge, Charles felt himself ‘dying by inches, from not having any body to talk to about insects’. During the next three years, before the departure of the Beagle, he and Fox exchanged frequent letters, mainly concerned with entomology. They corresponded regularly during the voyage, and continued to keep closely in touch on family matters until Fox’s death in 1880. On sending Fox a copy of The Descent of Man in 1870, in which he had finally faced up to bringing Man into the picture, Charles added: ‘It is very delightful to me to hear that you, my very old friend, like my other books.’

In the summer of 1828 Charles and a number of friends went to Barmouth on the coast of Wales as a reading party that was intended to brush up their mathematics, but in the event became more concerned with entomology. Even the unfortunate Herbert, who was severely lame thanks to a deformed foot, was dragged to the tops of the hills in search of beetles, though Charles made up for it by helping to carry him down. The enthusiasm and thoroughness with which Charles pursued his beetles had already become a legend among his contemporaries.

At the beginning of the Michaelmas term, Charles moved into the rooms at Christ’s in which he lived for the next three years. A former occupant of the set had been the eighteenth-century theologian William Paley (1743–1805). Perhaps his influence still lingered there, for although Charles devoted very little of his time to theology, he said afterwards that he had greatly appreciated the clarity of Paley’s language and the strength of his logic, and regarded his books on Evidences of Christianity and Moral Philosophy as the only part of the academic course which had helped to educate his mind. However, he now had plenty else to do, for he kept a horse in Cambridge for riding, and having persuaded his father and sisters to provide the funds for a powerful double-barrelled gun with percussion caps, could practise aiming it at a lighted candle in his rooms. His beetles were never neglected, and towards the end of his period in Cambridge he took up once more the study of the inner workings of living cells by microscopy that he had begun in Edinburgh with Robert Grant. This was made possible by a gift from a generous and initially anonymous donor, who later turned out to be Herbert, of the latest compound microscope designed by Henry Coddington, a mathematics tutor at Trinity.

Unquestionably the most important event in Charles’s life while he was at Cambridge was his friendship with the Revd Professor John Stevens Henslow, of whom he had been told by his brother Erasmus, and to one of whose Friday evening soirées for scientifically inclined undergraduates and dons he was taken by Fox in 1828. Henslow had first been Professor of Mineralogy in Cambridge for five years, and then became Professor of Botany from 1827 to 1861. He and Adam Sedgwick, the Revd Professor of Geology and Senior Proctor in the University, had founded the Cambridge Philosophical Society in 1819. Together with William Whewell, polymath and later Master of Trinity, Charles Babbage, the designer of calculating engines, and George Peacock, mathematician and Professor of Astronomy, Sedgwick and Henslow were the leading figures in the development of scientific research and teaching in the university during the first half of the nineteenth century. Henslow’s wide-ranging lectures on botany, covering every aspect of the chemistry and biology of plants as well as the essential minimum of their taxonomic classification by Linnaeus, were attended annually by sixty or seventy undergraduates and several professors. The courses included field excursions, sometimes on foot or else in stagecoaches or on a barge drifting down the river to Ely, punctuated by talks on the variety of plants, insects, shells and fossils that had been collected. In the late spring there was always a trip to Gamlingay heath, twenty miles to the west of Cambridge, where rare plants and animals were to be found, and which ended with a convivial social gathering at a country inn. Charles signed up for these activities in 1829, 1830 and 1831. With at least some of Sedgwick’s lectures that he also attended in 1831, they constituted the only formal instruction in science that he received at Cambridge.

Speaking of the last two terms at the university after he had passed his Bachelor of Arts examination in January 1831, tenth in the list of candidates who did not seek honours, Charles wrote of Henslow in his Autobiography:

I took long walks with him on most days, so that I was called by some of the dons ‘the man who walks with Henslow’; and in the evening I was very often asked to join his family dinner. His knowledge was great in botany, entomology, chemistry, mineralogy, and geology. His strongest taste was to draw conclusions from long-continued minute observations. His judgement was excellent, and his whole mind well-balanced; but I do not suppose that anyone would say that he possessed much original genius.

It is true that by modern standards Charles would not be regarded as having had an orthodox or adequate scientific training. But by the standards of 1831, and remembering the contacts with Grant and the lectures that he had attended in Edinburgh, he was by then as well educated in natural history as any student in the country. And although he had not passed any exams in the subject, he had greatly impressed some of the most eminent scientists in Cambridge with his practical ability as a collector, and with the high quality and purposefulness of his enquiring mind. ‘What a fellow that Darwin is for asking questions,’ said Henslow.

At around the same time Charles read two books that ‘stirred up in me a burning zeal to add even the most humble contribution to the noble structure of Natural Science’. One was the classical account by the German naturalist, geophysicist, meteorologist and geographer Alexander von Humboldt (1769–1859) about his travels through the Brazilian rain forest to the Andes and beyond with the botanist Aimé Bonpland (1773–1858).

(#litres_trial_promo) The second was the recent book by the astronomer and physicist John Herschel (1792–1871) on the study of natural science.

(#litres_trial_promo) Charles insisted on inflicting long readings from Humboldt on his friends, and worked out plans for an expedition to the Canary Islands in July to inspect the volcanic cone of the Pico de Teide on Tenerife, whose summit had been closely inspected by Humboldt in 1799 on his way out to South America. Some of the requirements of his plan were tiresome to meet, such as taking ‘intensely stupid’ lessons in Spanish, though he was not to know how useful they would prove to have been when later on he was riding with gauchos across the pampas in Patagonia. A number of prospective participants were enlisted, but on enquiring about the sailing of passenger vessels to the Canaries, Charles found that his planning was already too late, for the boats were scheduled for departures only in June. The trip would therefore have to be postponed to 1832.

It was pointed out by Henslow that such an enterprise would require a basic knowledge of geology. He therefore advised Charles on the purchase in London of the instrument for the measurement of the inclination of rock beds known as a clinometer, and showed him how to use it. Soon Charles could boast from Shrewsbury that ‘I put all the tables in my bedroom at every conceivable angle & direction. I will venture to say I have measured them as accurately as any Geologist going could do.’

(#litres_trial_promo)

Most significantly of all for Charles’s training as a geologist, Henslow prevailed on Adam Sedgwick to take Charles with him for part of his usual field excursion during the summer vacation. Sedgwick was renowned as a field geologist, skilled at the recognition of regional patterns of strata from details that were strictly local, and in August he was planning to visit North Wales in continuation of a project to describe all the rocks in Great Britain below the Old Red Sandstone.

(#litres_trial_promo) The first nights of the trip were spent by Sedgwick with the Darwins at Shrewsbury, where he made a great impression, especially on Charles’s sister Susan, often teased by the accusation that ‘anything in coat and trousers from eight years to eighty was fair game to Susan’. Charles had been practising his geology in the neighbourhood, and later related the story of the important scientific lesson that he learnt on that occasion:

Whilst examining an old gravel-pit near Shrewsbury a labourer told me that he had found in it a large worn tropical Volute shell, such as may be seen on the chimney-pieces of cottages; and as he would not sell the shell I was convinced that he had really found it in the pit. I told Sedgwick of the fact, and he at once said (no doubt truly) that it must have been thrown away by someone into the pit; but then added, if really embedded there it would be the greatest misfortune to geology, as it would overthrow all that we know about the superficial deposits of the midland counties. These gravel-beds belonged in fact to the glacial period, and in after years I found in them broken arctic shells. But I was then utterly astonished at Sedgwick not being delighted at so wonderful a fact as a tropical shell being found near the surface in the middle of England. Nothing before had ever made me thoroughly realise, though I had read various scientific books, that science consists in grouping facts so that general laws or conclusions may be drawn from them.

(#litres_trial_promo)

Sedgwick had of course appreciated that the shell could not possibly be a genuine find in such a place. His scepticism taught Charles a valuable lesson, and brought home to him the importance of assembling plenty of mutually compatible observations to support any new scientific theory. Thereafter he would keep his mouth tightly shut until sufficient evidence had been accumulated.

Sedgwick’s aim was to follow the line of contact along the Vale of Clwyd between the Carboniferous Limestone cliffs and the Old Red Sandstone, shown in the geological map with ribbons crossing the Vale at several points, starting at Llangollen and finishing at Great Ormes Head on the coast.

(#litres_trial_promo) At a quarry near Ruthin they found a possible outcrop of the Old Red, and north of Henllan there was red sand and earth, but Sedgwick was not sure that this established with certainty the nature of the underlying strata. Charles was therefore dispatched on a traverse of his own from St Asaph to Abergele via Betwys-yn-Rhos, crossing a substantial band of Old Red shown on the map. Finding in some places a few loose stones and some reddish soil, he noted: ‘It was in such points as these where the strata have been much disturbed, that I observed the greatest number of bits of Sandstone, but in no place could I find it in situ.’

(#litres_trial_promo) Near Abergele the soil was indeed ‘very red’, but this he attributed ‘entirely to the very ferruginous [rich in iron] seams in the rock itself, & not to the supposed sandstone beneath it’. That evening he told Sedgwick that there was no true Old Red to be seen, and to the end of his life could remember how pleased his teacher had been with this new evidence that the Vale of Clwyd did not have a complex structure as had been supposed, but was a simple trough-like syncline

(#litres_trial_promo) resulting from a stretching of the strata. Although his experience of geology in the field was thus limited to just one week, Charles had sat at the feet of a master, and had solved his first problem with conspicuous success.

(#ulink_9f9f8405-2066-5fb0-8f19-7caade431fa8)

Geological map of part of North Wales, redrawn by Secord

(#litres_trial_promo) after Greenough,

(#litres_trial_promo) with Charles’s route from Llangollen to Penmaenmawr as a dotted line. In the second edition of Greenough’s map, published in 1839, the Old Red Sandstone had disappeared.

Among other sites of geological interest in the Vale were the famous caves in the limestone cliffs at Plas-yn-Cefn, above the River Elwy. Here the owner had excavated vertebrate fossils in the largest cave that included the tooth of a rhinoceros, and there were other bones in the mud. Charles’s imagination was fired by the prospect of making similar discoveries from past worlds in his projected trip to the Canaries, though his hopes were not in fact realised until his arrival in 1832 at the cliffs of Punta Alta in Patagonia. After a week, Charles and Sedgwick separated at Capel Curig in the neighbourhood of Bethesda, and Charles strode on across the central mountains of Wales, steering by map and compass, to join some Cambridge friends at Barmouth.

Reaching home at Shrewsbury on 29 August 1831 after two weeks of shooting with his Uncle Jos at Maer, ‘for at that time I should have thought myself mad to give up the first days of partridge shooting for geology or any other science’, Charles found the fateful letter from Henslow proposing that he should sail on the Beagle. The clock must next be turned back to explain its origin.

CHAPTER 2 (#ulink_bbe7a153-23ba-5ec1-9110-d4d832eac649)

The Strange Consequences of Stealing a Whale-Boat (#ulink_bbe7a153-23ba-5ec1-9110-d4d832eac649)

On 25 September 1513 the Spanish explorer Vasco Núñez de Balboa crossed the narrow isthmus joining the two halves of the American continent to discover on the far side the Mar del Sur, later named the Pacific Ocean. The town of Panama was built on the Pacific shore, and became the base for a rapid expansion by the Spaniards. While Hernán Cortés was conquering the Aztec empire in Mexico, Francisco Pizarro was overcoming the Incas in Peru. During the next three hundred years prosperous Spanish colonies were established in the western and southernmost parts of South America, while in the east the Portuguese took over a large area in Brazil.

The English were jealous of their success, but for a long time could only benefit from it by robbery, following the example of Sir Francis Drake when he returned from his circumnavigation in 1580 with a rich cargo of treasures stolen from the Spanish colonies at Queen Elizabeth’s behest. In 1806 Buenos Aires was attacked by a British force, which was successfully repelled, giving the Argentinians the confidence to join the other Spanish colonies in breaking away from Spain. By 1820 they were all independent countries, though not always at peace with one another.

The Hydrographic Office of the Royal Navy, founded in 1795, was initially responsible for looking after the Admiralty’s collection of navigational charts, and of the ‘Remark Books’ about foreign shores and harbours that all naval captains were required to keep. In 1817 the second Hydrographer, Captain Hurd, was empowered to recruit some surveyors of his own, and had soon built up a programme of a dozen Admiralty surveys in home waters and abroad. Trade was quickly building up with the new governments of South America, and there was a need both for a British naval presence in South American waters, and for accurate charts of the coastline to assist shipping. Hence it came about that:

In 1825, the Lords Commissioners of the Admiralty directed two ships to be prepared for a Survey of the Southern Coasts of South America; and in May of the following year the ADVENTURE and the BEAGLE were lying in Plymouth Sound, ready to carry the orders of their Lordships into execution. These vessels were well provided with every necessary, and every comfort, which the liberality and kindness of the Admiralty, Navy Board, and officers of the Dock-yards, could cause to be furnished.

(#litres_trial_promo)

HMS Adventure was a ‘roomy’ ship of 330 tons, without guns, under the command of Captain Phillip Parker King. HMS Beagle was a smaller vessel of 235 tons, rigged as a barque carrying six guns, and commanded by Captain Pringle Stokes. On 19 November 1826, Adventure and Beagle sailed south from Monte Video, and until April 1827 carried out surveys in the south of Patagonia and in Tierra del Fuego, around the Straits of Magellan. In June 1827 they arrived back at Rio de Janeiro. Six months later, now accompanied by a schooner named Adelaide to assist in the surveys – for whose purchase Captain King had prudently obtained Admiralty approval in advance, unlike Captain FitzRoy when in 1833 he bought the second and smaller Adventure – they sailed south again. In January 1828 the Adventure was anchored for the winter at Port Famine. Captain Stokes was ordered in the Beagle ‘to proceed to survey the western coasts, between the Strait of Magalhaens and latitude 47° south, or as much of those dangerous and exposed shores as he could examine’, and to return to Port Famine (Puerto Hambre) by the end of July. Captain King allotted himself a more comfortable task in the Adelaide, charting the southern parts of the Strait relatively close at hand, and collecting birds and plants.

When at the appointed time the Beagle returned to Port Famine with her difficult assignment conscientiously completed, Captain Stokes was found to be in a state of acute depression thanks to the extreme privations and hardships that he and his crew had suffered from very severe weather, both stormy and wet, when working in the Gulf of Peñas. On 1 August 1828 he tried unsuccessfully to shoot himself, and although the surgeons thought for a while that he might recover, he died in great pain on 12 August. He was interred at the Adventure’s burial ground, the so-called English Cemetery two miles from Port Famine. (The tablet erected to his memory has since been moved to the Museo Saleciano in the modern town of Punta Arenas, some forty miles away along the Straits of Magellan.)

The Adventure and the Beagle, temporarily commanded by her First Lieutenant, William Skyring, sailed back to Rio de Janeiro in October for repairs and replenishment of their stores. Here Admiral Otway, Commander-in-Chief of the South American Station, appointed his young Flag Lieutenant, Robert FitzRoy,

(#litres_trial_promo) to take over command of the Beagle in succession to Captain Pringle Stokes. His choice was successful, and FitzRoy had soon overcome the handicap of restoring the morale of a demoralised ship’s company well enough to continue the charting of one of the world’s most inhospitable coasts.

During 1829 the Adventure, Beagle and Adelaide conducted independent surveys at various points between Tierra del Fuego and Chiloe, coming together at Valparaiso in November. On 19 November the Beagle departed to survey more of the southern coasts of Tierra del Fuego before rejoining the Adventure at Rio de Janeiro for the final return to England. Working among the Camden and Stewart Islands to the south of the mouth of the Cockburn Channel, FitzRoy found tiresome anomalies in his compass bearings, and wrote in his journal for 24 January 1830:

There may be metal in many of the Fuegian mountains, and I much regret that no person in the vessel was skilled in mineralogy, or at all acquainted with geology. It is a pity that so good an opportunity of ascertaining the nature of the rocks and earths of these regions should have been almost lost. I could not avoid often thinking of the talent and experience required for such scientific researches, of which we were wholly destitute; and inwardly resolving, that if ever I left England again on a similar expedition, I would endeavour to carry out a person qualified to examine the land; while the officers and myself would attend to hydrography.

(#litres_trial_promo)

A week later it was reported to FitzRoy that the ship’s five-oared whale-boat, manned by Mr Murray, the Master, and a small crew, had been stolen during the night by the Fuegians near Cape Desolation, ‘now doubly deserving of its name’. The bad news was brought to the Beagle by two of the sailors, paddling a basket-like canoe that they had thrown together for the purpose, and whose curious structure was commemorated in the names given both to the small island on which Cape Desolation was located, and to the first of the Fuegians taken hostage by FitzRoy.

(#litres_trial_promo)

On the Beagle’s map of the Strait of Magalhaens (sic),

(#litres_trial_promo) Basket Isle was inserted near the western end of Tierra del Fuego, with Thieves Sound to the north, and Whale Boat Sound to the east. In a modern map the area lies on the coast of Tierra del Fuego due south of Punta Arenas. FitzRoy responded to the theft with a campaign to capture hostages for return of the whale-boat, but the move failed, largely because the Fuegians showed no interest in exchanging their booty for their comrades, who remained quite happily on the ship. So he was left with the young girl Fuegia Basket, ‘as broad as she was high’, and the men York Minster, taken in Christmas Sound near the cliff of that name, and Boat Memory captured later nearby. He soon began to appreciate the practical difficulties that would arise in returning them immediately to their own peoples, and to consider the possibility of taking them back to England for a period of education before they were repatriated.

While a replacement for the whale-boat was being built at Doris Cove, situated on an island beside Adventurer Passage, Mr Murray was dispatched in the ship’s cutter to explore the waters to the north and east of Nassau Bay. Not far to the north, but a long way to the east, he sailed through a channel little more than a third of a mile wide which became known as the Murray Narrow, and which ‘led him into a straight channel, averaging about two miles or more in width, and extending nearly east and west as far as the eye could reach’. He had discovered the Beagle Channel, whose precise orientation on the map would provide grounds for legal dispute long afterwards in arguments between Argentina and Chile over territorial rights in the Antarctic. The new country was thickly populated, and on 11 May 1830, when the Beagle herself was in the Murray Narrow, some canoes full of natives anxious for barter were encountered. FitzRoy wrote: ‘I told one of the boys in a canoe to come into our boat, and gave the man who was with him a large shining mother-of-pearl button.’

(#litres_trial_promo) Jemmy Button, as the boat’s crew called him, quickly settled down in his new surroundings, and there were now four Fuegians in FitzRoy’s little group.

(#litres_trial_promo)

At the end of June the Beagle sailed back to the Rio Plata. While in Monte Video, FitzRoy tried to have the Fuegians vaccinated against smallpox, whose ravages were all too often fatal to unprotected natives, but the vaccination did not take. At the beginning of August the Beagle rejoined the Adventure in Rio de Janeiro, and together they made a ‘most tedious’ passage to Plymouth, where they anchored on 14 October.

(#ulink_3665d9eb-b1d5-5777-9868-8fa68808145f)

FitzRoy’s first thought was for the Fuegians. Landing after dark, they were taken to lodgings where next day they were vaccinated for the second time. With the Beagle’s coxswain James Bennett to look after them, they were then transferred to a farmhouse in the country near Plymstock, where they could enjoy the fresh air and hopefully avoid infection by other virus diseases, without attracting public attention. Meanwhile the Beagle was stripped and cleared out, and on 27 October her pendant was hauled down.

During the voyage home, FitzRoy had addressed through Captain King to John Barrow,

(#litres_trial_promo) Second Secretary of the Admiralty, a long account of the manner in which he had taken the four Fuegians on board the Beagle,38 and of his proposal to return them to their country after they had received some education. Mr Barrow’s response, although it was negatively worded and predictably lacking in enthusiasm, said that their Lordships would not interfere with FitzRoy’s benevolent intentions towards the Fuegians, would afford him facilities towards their maintenance and education, and would give them a passage home again. Their Lordships’ promise was duly kept when early in November Boat Memory was taken ill with smallpox, and instructions were at once given for the Fuegians to be admitted to the Royal Naval Hospital at Plymouth for vaccination and treatment. Unhappily Boat Memory, who was FitzRoy’s favourite among them, could not be saved, but the other three were successfully re-vaccinated. Fuegia Basket was in addition taken home by the doctor in charge of them in order to be exposed to measles with his own children. She duly had a favourable attack and quickly recovered with a strengthened immune system.

Through contacts with the Church Missionary Society, the Fuegians were next taken to Walthamstow just outside London for schooling in charge of the Revd William Wilson, and remained in his care until October 1831, still with James Bennett to keep an eye on them. Fuegia Basket and Jemmy Button were very receptive pupils, but the older man York Minster was not. He would reluctantly assist with practical activities like gardening, but firmly refused to learn to read. He also took what seemed to be an unhealthy interest in the ten-year-old Fuegia, following her everywhere, keeping her well away from other men, and treating her as if she was his personal possession. At this time there was no suggestion that anything sexual took place between them, though on board the Beagle later on she was deemed to be officially engaged to York in order to avoid embarrassment, and back in Tierra del Fuego she did become his wife. During that summer the Fuegians were taken to St James’s Palace at King William IV’s request, and Queen Adelaide honoured Fuegia Basket by placing one of her own bonnets on the girl’s head and a ring on her finger, and gave her some money to buy clothes for returning home.

FitzRoy had been led by Captain King to suppose that the Adventure and Beagle’s surveys in South America would need to be continued by some other ship, giving him an opportunity to restore the Fuegians to their native land. But having in March 1831 completed his official obligations with respect to the Beagle’s 1826–1830 cruise, for which he was officially commended, FitzRoy discovered that the Admiralty’s plans had for no stated reason been altered, and that their Lordships no longer intended to complete the survey. Feeling that he could not trust anyone but himself to return the Fuegians to the precise places from which they had been taken, he obtained twelve months’ leave of absence from the Navy. In June he made at his own expense an agreement with the owner of a small merchant ship to take him with five companions, the Fuegians, and a number of goats to Tierra del Fuego, where he proposed to stock some of the islands with goats and deposit his protégée and protégés. This agreement did not, however, have to be put into effect, for FitzRoy happened one day to mention his problem to one of his aristocratic and politically influential uncles, the fourth Duke of Grafton, and the former Foreign Secretary Lord Castlereagh’s half-brother Lord Londonderry. After some effective wire-pulling at the Admiralty, their Lordships were persuaded to appoint FitzRoy to command the Beagle once again for a second surveying cruise.

The greatest of hydrographers, Captain Francis Beaufort, who had taken charge of the Hydrographic Office in 1829, embraced with enthusiasm the opportunity of filling in some of the many blank spaces in the existing maps of the coast of Argentina and Tierra del Fuego, and extending the naval charts to cover not only Argentina and the Falkland Islands, but also more of the coasts of Chile and Peru as far north as Ecuador. FitzRoy would also be entrusted with the task of carrying a chain of meridian distances, which measured the difference in longitude between an established location and a new one, all the way round the world by sailing back across the Pacific. The Beagle was therefore instructed to return via the Galapagos Islands, Tahiti, New Zealand, Australia – calling at Port Jackson observatory in Sydney, Hobart, and King George Sound – the Cocos Keeling Islands, Mauritius, the Cape of Good Hope, St Helena, Ascension, and so home. Beaufort’s long Memorandum to FitzRoy,

(#litres_trial_promo) carefully explaining this plan, included a note forbidding senior officers whom he might encounter to take from him any of his instruments or chronometers; instructions for sedulous observations of the eclipses of Jupiter’s third and fourth satellites; and advice on the best way of handling natives. Lastly, the Beagle was the first ship in the Navy to be issued with Beaufort’s list of the Figures, still in popular use today, to denote the force of the wind, based at the lower end on the speeds at which a man-of-war with all sails set would be driven, and at the upper end on what set of sails could just be carried safely at full chase. A second list of letters was drawn up to describe the state of the weather, but this has now fallen out of use.

The Beaufort Scale

While the Beagle was being extensively refitted at Devonport in preparation for her long voyage, FitzRoy, remembering his resolution to recruit a geologist should he pay another visit to Tierra del Fuego,

(#litres_trial_promo) set about finding ‘some well-educated and scientific person who would willingly share such accommodations as I had to offer, in order to profit by the opportunity of visiting distant countries yet little known’.

(#litres_trial_promo) He began by consulting the most appropriate person at the Admiralty, Francis Beaufort, who being closely in touch with the scientific reformers at Cambridge and in the Royal Society was keen to modernise and bring more science into the Hydrographic Office, and was immediately sympathetic. Beaufort accordingly wrote to his mathematical friend George Peacock at Trinity College, Cambridge, telling him of the opening for ‘a savant’ on a surveying ship. Early in August, Peacock passed the news on to Henslow, although he had not perfectly interpreted the situation in speaking of a vacancy specifically for a naturalist, and in later correspondence placed greater emphasis on FitzRoy’s need for a companionable and gentlemanly scientist:

My dear Henslow

Captain Fitz Roy is going out to survey the southern coast of Terra del Fuego, & afterwards to visit many of the South Sea Islands & to return by the Indian Archipelago: the vessel is fitted out expressly for scientific purposes, combined with the survey: it will furnish therefore a rare opportunity for a naturalist & it would be a great misfortune that it should be lost:

An offer has been made to me to recommend a proper person to go out as a naturalist with this expedition; he will be treated with every consideration; the Captain is a young man of very pleasing manners (a nephew of the Duke of Grafton), of great zeal in his profession & who is very highly spoken of; if Leonard Jenyns could go, what treasures he might bring home with him, as the ship would be placed at his disposal, whenever his enquiries made it necessary or desirable; in the absence of so accomplished a naturalist, is there any person whom you could strongly recommend: he must be such a person as would do credit to our recommendation.

Do think on this subject: it would be a serious loss to the cause of natural science, if this fine opportunity was lost.

The ship sails about the end of Sept

.

Poor Ramsay!

(#litres_trial_promo) what a loss to us all & particularly to you.

Believe me / My dear Henslow / Most truly yours /

George Peacock

7 Suffolk Street / Pall Mall East

My dear Henslow

I wrote this letter on Saturday, but I was too late for the post. What a glorious opportunity this would be for forming collections for our museums: do write to me immediately & take care that the opportunity is not lost.

Believe me / My dear Henslow / Most truly yours /

Geo Peacock

7 Suffolk St. / Monday

(#litres_trial_promo)

As has already been seen, Leonard Jenyns was another clerical naturalist, brother-in-law of Henslow and vicar of Swaffham Bulbeck near Cambridge. After a day’s consideration of the offer, Jenyns decided regretfully that he could not leave his parish. Henslow therefore turned to Charles Darwin as the obvious alternative choice, and on 24 August wrote:

My dear Darwin, Before I enter upon the immediate business of this letter, let us condole together upon the loss of our inestimable friend poor Ramsay of whose death you have undoubtedly heard long before this. I will not now dwell upon this painful subject as I shall hope to see you shortly fully expecting that you will eagerly catch at the offer which is likely to be made you of a trip to Terra del Fuego & home by the East Indies. I have been asked by Peacock who will read & forward this to you from London to recommend him a naturalist as companion to Capt Fitzroy employed by Government to survey the S. extremity of America. I have stated that I consider you to be the best qualified person I know of who is likely to undertake such a situation. I state this not on the supposition of y

being a finished Naturalist, but as amply qualified for collecting, observing, & noting anything worthy to be noted in Natural History. Peacock has the appointment at his disposal & if he can not find a man willing to take the office, the opportunity will probably be lost. Capt. F wants a man (I understand) more as a companion than a mere collector & would not take any one however good a Naturalist who was not recommended to him likewise as a gentleman. Particulars of salary &c I know nothing. The Voyage is to last 2 y

& if you take plenty of Books with you, any thing you please may be done – You will have ample opportunities at command – In short I suppose there never was a finer chance for a man of zeal & spirit. Capt. F is a young man. What I wish you to do is instantly to come to Town & consult with Peacock (at N

7 Suffolk Street Pall Mall East or else at the University Club) & learn further particulars. Don’t put on any modest doubts or fears about your disqualifications for I assure you I think you are the very man they are in search of – so conceive yourself to be tapped on the Shoulder by your Bum-Bailiff

(#litres_trial_promo) & affect

friend /J.S. Henslow

(#litres_trial_promo)

This letter was reinforced in similar terms two days later by another from Peacock. Although both Peacock and Henslow said in their letters that FitzRoy was looking for a naturalist, it is evident that at some point in FitzRoy’s original conversation with Beaufort a geologist had been mentioned, for Henslow’s candidate for the post was described by FitzRoy himself as ‘Mr. Charles Darwin, grandson of Dr. Darwin the poet, a young man of promising ability, extremely fond of geology, and indeed all branches of natural history.’

(#litres_trial_promo) That FitzRoy thought he was primarily getting a geologist would be consistent with his gift to Charles on their departure from Plymouth of the first volume of Charles Lyell’s Principles of Geology. Moreover in his first report to the Royal Geographical Society on the Beagle’s return to England in 1836 he said that ‘Mr Charles Darwin will make known the results of his five years’ voluntary seclusion and disinterested exertions in the cause of science. Geology has been his principal pursuit.’

CHAPTER 3 (#ulink_f26215fe-a8fe-501e-a52e-2d90745a24a4)

Preparations for the Voyage (#ulink_f26215fe-a8fe-501e-a52e-2d90745a24a4)

Charles arrived back in Shrewsbury on Monday, 29 August from his trip in North Wales with Sedgwick, and was given Peacock’s and Henslow’s letters by his sisters. His immediate and joyful reaction was to accept, but finding next morning that his father was strongly opposed to the scheme, he wrote sorrowfully to Henslow:

M

Peacock’s letter arrived on Saturday, & I received it late yesterday evening. As far as my own mind is concerned, I should think, certainly most gladly have accepted the opportunity, which you so kindly have offered me. But my Father, although he does not decidedly refuse me, gives such strong advice against going, that I should not be comfortable if I did not follow it. My Fathers objections are these: the unfitting me to settle down as a clergyman; my little habit of seafaring; the shortness of the time & the chance of my not suiting Captain Fitzroy. It is certainly a very serious objection, the very short time for all my preparations, as not only body but mind wants making up for such an undertaking. But if it had not been for my father, I would have taken all risks … Even if I was to go, my Father disliking would take away all energy, & I should want a good stock of that. Again I must thank you; it adds a little to the heavy, but pleasant load of gratitude which I owe to you.

(#litres_trial_promo)

A letter in similar terms that he also wrote to Peacock has not survived.

All was not lost, however, for Robert had recognised the considerable compliment that had been paid to his son by the two eminent academics in Cambridge, and tempered his disapproval by telling Charles, ‘If you can find any man of common sense who advises you to go, I will give my consent.’ He well knew who that man might be, and wrote to Josiah Wedgwood II on 30 August: ‘Charles will tell you of the offer he has had made to him of going for a voyage of discovery for 2 years. – I strongly object to it on various grounds, but I will not detail my reasons that he may have your unbiassed opinion on the subject, & if you feel differently from me I shall wish him to follow your advice.’

(#litres_trial_promo)

Charles himself rode straight over to Maer, where he found his uncle and cousins full of enthusiasm for his embarking on the voyage, and by the evening all were urging him to reopen the case with his father. On 31 August, with Uncle Josiah at his elbow, he wrote an extremely apologetic note to his father, ending on a separate piece of paper with the list of objections to be answered:

I am afraid I am going to make you yet again very uncomfortable. I think you will excuse me once again stating my opinions on the offer of the Voyage. My excuse and reason is the different way all the Wedgwoods view the subject from what you & my sisters do … But pray do not consider that I am so bent on going, that I would for one single moment hesitate if you thought that after a short period, you should continue uncomfortable.

1 Disreputable to my character as a Clergyman hereafter

2 A wild scheme

3 That they must have offered to many others before me, the place of Naturalist

4 And from its not being accepted there must be some serious objection to the vessel or expedition

5 That I should never settle down to a steady life hereafter

6 That my accomodations [sic] would be most uncomfortable

7 That you should consider it as again changing my profession

8 That it would be a useless undertaking

(#litres_trial_promo)

Enclosed with this letter was one from Josiah to Robert:

My dear Doctor I feel the responsibility of your application to me on the offer that has been made to Charles as being weighty, but as you have desired Charles to consult me I cannot refuse to give the result of such consideration as I have been able to give it. Charles has put down what he conceives to be your principal objections & I think the best course I can take will be to state what occurs to me upon each of them.