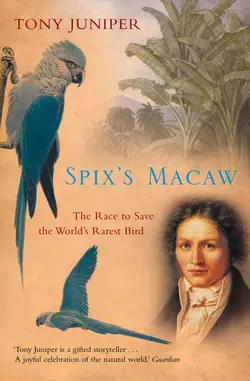

Spix’s Macaw: The Race to Save the World’s Rarest Bird

Tony Juniper

An environmental parable for our times – the story of a beautiful blue bird meeting its nemesis at the end of the 20th-century.In December 1897 the Reverend F. G. Dutton lamented that ‘there are so many calls on a parson’s purse, that he cannot always treat himself to expensive parrots.’ He was hoping to purchase a Spix’s Macaw, a rare and beautiful parrot found in a remote area of Brazil. Today, the parson’s search would be in vain. By the turn of the millennium only one survivor, a lone male, existed in the wild.Spix’s Macaw tells the hearbreaking story of a unique band of brilliant blue birds – who talk, fall in love, and grieve – struggling against the forces of extinction and their own desirability. By the second half of the 20th-century the birds became gram for gram more valuable than heroin; so valuable that they drew up to $40,000 on the black markets. When, in 1990, only one was found to be living in the wild, an emergency international rescue operation was launched and an amnesty declared, allowing private collectors to come forward with their illegal birds, possible mates for the last wild Spix.In a breathtaking display of stoicism and endurance, the loneliest bird in the world had lived without a mate for fourteen years, had outwitted predators and second-guessed the poachers. But would he take to a new companion? Spix’s Macaws are like humans – they can’t be forced to love. With exquisite detail, this book tells the dramatic story of the rescue operation, and of the humans whose selfishness and greed brought a beautiful species to the brink of extinction. The long, lonely flight of the last Spix’s Macaw is both a love story and an environmental parable for our times.

SPIX’S MACAW

THE RACE TO SAVE THE WORLD’S RAREST BIRD

Tony Juniper

Copyright (#ulink_d0a0800c-64d5-5e06-ab0b-221362fb7563)

Fourth Estate

A Division of HarperCollinsPublishers 1 London Bridge Street London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

First published in Great Britain in 2002 by Fourth Estate

This edition first published in 2003

Copyright © Tony Juniper 2002 and 2003

The right of Tony Juniper to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the nonexclusive, nontransferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins e-books.

Source ISBN: 9781841156514

Ebook Edition © FEBRUARY 2016 ISBN 9780007391776

Version: 2016-01-12

HarperCollinsPublishers has made every reasonable effort to ensure that any picture content and written content in this ebook has been included or removed in accordance with the contractual and technological constraints in operation at the time of publication.

Dedication (#ulink_9c770464-2d40-5141-ba9b-04f6b7084e1b)

For my Mother and Father

Contents

Cover (#u79971a1d-8d5f-52f9-a82d-318aabfd90c7)

Title Page (#u76838994-099f-5c97-b992-bcec46b6c881)

Copyright (#u82cd627d-8089-5f70-94ba-4ae6ac96cec5)

Dedication (#u890db6f3-7ab7-5f7e-9147-a1b88bb3ebf3)

Map (#u2d7ec255-6a40-5a90-bc72-68bfba838f76)

Chapter 1 (#u1c2b2d02-399c-5d24-8339-21f72eba6a5b)The Real Macaw (#u1c2b2d02-399c-5d24-8339-21f72eba6a5b)

Chapter 2 (#ue016a357-a117-5d2c-b417-81440aabc368)The First Spix (#ue016a357-a117-5d2c-b417-81440aabc368)

Chapter 3 (#ufd596f19-5db1-5226-bcfb-5925210236ef)Parrot Fashion (#ufd596f19-5db1-5226-bcfb-5925210236ef)

Chapter 4 (#uc2fbb75c-6598-5736-b849-6aea191780ea)The Four Blues (#uc2fbb75c-6598-5736-b849-6aea191780ea)

Chapter 5 (#litres_trial_promo)What Are You Looking For at the End of the World? (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 6 (#litres_trial_promo)The Legions of the Doomed (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 7 (#litres_trial_promo)Private Arks (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 8 (#litres_trial_promo)The Rarest Bird in the World (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 9 (#litres_trial_promo)Uncharted Territory (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 10 (#litres_trial_promo)Betrayal (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 11 (#litres_trial_promo)An Extinction Foretold? (#litres_trial_promo)

Epilogue (#litres_trial_promo)

Index (#litres_trial_promo)

Acknowledgements (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

Notes (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

Map (#ulink_ae8a3de8-367b-564a-a340-3a6d28ad3766)

1 The Real Macaw (#ulink_7a6529e7-7334-5694-8929-36c4f068b896)

The blue parrot came to rest on a bare sun-bleached branch that stuck out from the bushy crown of a craggy old caraiba tree. The magnificent old plant, some 25 metres tall, was one in a long ribbon of trees that fringed a winding creek. The parrot had chosen a high branch, a natural vantage point. From his lofty position, the bird scanned the flat thorny cactus scrub that lay around in all directions. He climbed to a branch slightly lower down, using his feet and beak, checking behind and above for airborne predators. When hawks were hunting, a second of relaxation could cost him his life. Once the parrot was satisfied it was safe, he cried out, quite a harsh call, but thin with a trilling quality. He received a distant reply, and then another.

Moments later, from around a bend in the creek, two parrots appeared, flying fast and strong above the treetops. They followed the line of the green-fringed channel, their long tails flexed and strained against the air, their flowing blue plumes acting as a rudder to steer a course towards the huge tree. They spread their tails, rotated their wings backwards and fluttered to rest next to the bird already perched there. The thin branches swayed as they took the parrots’ weight. The birds’ scaly grey feet gripped tightly as the branches rocked gently back and forth. The parrots fluffed out their body and flight feathers and waggled their tails to ensure that their plumage lay correctly. This ritual ensured they would be ready for instant flight should they need to leave in a hurry. Finally, every feather in place, they settled down on the caraiba tree.

The trio were the adult male parrot who had first made the call, and a pair of young adults. More chatter followed, then the birds indulged in friendly fencing with their hooked black bills. Their sharp yellowish eyes regarded one another carefully, their dark pupils dilating. Then once more scanning the surrounding land, the first bird began to climb down the caraiba tree. Beneath it was a pool of muddy water.

As the first bird went lower, his companions nervously followed, very quiet now, anxious not to attract unwelcome attention. Going to the ground to drink was dangerous. It was a necessary daily chore, but they didn’t like it. Not only were hawks still a threat but snakes and other predators could catch them down there. There had recently been a population explosion among the local wild cats, and the parrots needed extra caution. They tilted their heads to get a better view of the ground, paying particular attention to the bushy cover at the edge of the creek.

They stopped once more and again checked for danger, then fluttered one by one the last five metres to the moist sandy ground of the creek bed. As they landed and cast shadows over the margins of the pool, tadpoles scattered into the murky brown water at the centre. Whether the larvae of the frogs would progress to a terrestrial existence depended on more rain. This pool would evaporate soon under the hot tropical sun.

The parrots drank deep and fast. Taking their fill in seconds, they immediately flew back up to the bare top of the tree. They called once more, and then took off again down the creek calling loudly. Two kilometres upstream they stopped to perch in another of the tall trees. They knew that they would find food here. It was late in the day and dusk would soon fall but a meal of the caraiba’s seeds would see them through the night.

When the baking sunshine of the day was extinguished a suffocating cloak of warmth rose from the parched earth. It was time to roost. Two of the birds, the pair, would spend the night in a hollow in one of the tall trees. They regularly slept there and felt safe. Their companion, the single male bird, perched atop a tall spiny cactus.

The tall trees that bordered the seasonally flooded creeks formed a rare green oasis. The rest of the woodland, if you could call it woodland, was mostly low and composed of tangled thickets of spindly thorn bushes and cacti. There were baked open areas where little at all grew. It was a melancholy landscape, especially in the heat of the dry season when the stillness and quiet gave a paradoxically wintry feeling. In all directions its vastness rolled in endless undulations towards an ever-receding horizon. Located in the interior of north-eastern Brazil, these dry thorny woodlands, the ‘caatinga’, occupied an immense area, some 800,000 square kilometres in all – considerably larger than the US state of Texas or about three times the size of the island of Great Britain. Amid sharp rocks, viciously spined cacti, the lance-like thorns of the bushes and brutal unrelenting heat, this peculiar place felt lonely, an isolated and forgotten corner of the world.

Drought turned the forest into a desolate and brittle chaos. Animals could hide in the shade, but the plants could not. Adapted to the desiccating climate, the plants eked out the precious water in whatever way they could. Some had thick waxy leaves, others potato-like tuber roots or fine hairs to scavenge moisture from the air. Most trees and shrubs were deciduous and even those said to be evergreen lost their leaves in the worst droughts. And when the droughts dragged on, as they frequently did, there was death. Creatures that succumbed didn’t rot; the dry heat drained their body fluids and mummified them. Sheep and goats killed by lack of food and water lay like specimens preserved for museum display.

The energy in the winds was small and the airstreams that came brought little rain. It was a harsh place and had become known as the backlands: a forgotten country scorned by the outside world as a desolate wasteland fit only for goats and sheep.

In the good years, dark clouds spawned violent thunderstorms that brought relief from the unforgiving drought. As the lifeless desert was for a short time banished, the caatinga became a brief paradise of green dotted with white, yellow and red flowers. When the first rains fell, it was as if the drops of moisture were hitting the face of a red-hot iron. Flashed back into vapour, the first specks of water could not penetrate the earth. If the rain continued to fall, the baked red soil would first become darkly stained, damp and then moistened. Tiny rivulets formed, then streams and finally substantial bodies of water accumulated in the creeks.

What little rain there was fell in a four- or five-month period, generally from about November to April. Most of the year, even in ‘wet’ years, it did not rain at all. But because the creeks that drained the land during the brief annual deluges retained some of the moisture in their deep fine soils, ribbons of tall green trees grew there – little streaks of green in the great dry wilderness.

In this uncompromising environment, the blue parrots had made their home. Tested and honed by the punishing climate, their bodies and instincts had been moulded into the alert exotic blue creatures that flew there now. Perhaps, like many other animals found in these tough lands, they had first evolved in kinder and wetter conditions but now found themselves driven by thousands of years of climatic change to the precious few areas of moister habitat within the caatinga. The tree-lined creek was one such place.

Exquisite blue creatures some 60 centimetres long, darker above, slightly more turquoise below, their heads were paler and greyer and at a distance sometimes appeared almost white. Depending on the angle and intensity of light, the birds sometimes showed a greenish cast. When they fluffed out their head feathers, they took on a different appearance and looked almost reptilian, an impression enhanced by their intense bare faces. Their outward resemblance to small dinosaurs reinforced the impression that these curious birds were descended from a remote past.

At first light next day the trio of blue parrots collected together once more at the top of the huge bare-branched tree and resumed their daily routine. Their first port of call was a fruiting faveleira tree down the creek towards the main river. As the parrots approached their destination and breakfast, they were greeted by a screeching flock of Blue-winged Macaws, a type of small macaw known locally as maracanas. These birds were already feeding in the dense green foliage of the fruit tree’s crown. Despite their bright green plumage, their striking white faces and red and blue patches, to an observer on the ground or even an aerial predator they were almost invisible.

These smaller and mainly green macaws shared the creekside woods with their larger blue cousins. Relations between them were generally quite amicable, unless one of the smaller macaws sat on one of the favourite perches of the bigger ones. If they trespassed in this way, they would be angrily driven off. Although there were several other species of parrot living in the creek, the little maracanas were the only other kinds of macaw. They were also the only other birds the bigger blue species deigned to have any social contact with.

Amid the chattering and bickering of the busy maracanas, a distant growl registered in the blue birds’ finely tuned senses. The sound grew closer. It was a rare sound in this remote place – the sound of a vehicle. The blue parrots knew that the approaching sound often meant trouble. On top of the hawks, wild cats and snakes, the three blue macaws had come to know a still more deadly predator. And that lethal hunter was on the prowl again now. This predator stalked his prey by both night and day. This predator never gave up: if one method of capture failed, he tried a new one. He took babies from their nests and even stole eggs.

The birds fled upstream once more until they arrived at a tall caraiba tree with dense foliage covering the branches in its crown. They had already eaten well and felt able to rest. As the dazzling sun grew hotter, the parrots melted into the shadows, to doze, preen and chatter. They disappeared into the dappled light and shade cast by the long waxy leaves of the caraiba tree. Just as they relaxed, the birds were shocked to full alertness by a startling shrill screeching sound. It was the scream of a distressed parrot, a panic-laden cry made by a wounded bird facing a predator. The macaws’ curiosity was aroused. They were compelled to respond to the call.

They fluttered to an opening in the caraiba’s dense canopy to gain a better view of the creek. Finding no line of sight to the source of the sound they cautiously flew towards it. The noise was coming from some distance away on a bend in the creek. The three birds approached. As they drew nearer they could see on the ground a struggling parrot. It appeared unable to move from its place on the creek bed even though it was violently writhing. The single blue macaw approached while the pair remained at a distance. His natural caution overtaken, the parrot descended to a low perch closer to the bird struggling on the ground.

As he settled, two men burst forth and ran towards him. They crashed over dry sticks and leaves that lay on the sandy bed of the creek. Terrified, the macaw took to his wings, but he couldn’t fly. The spot where he had perched was covered in bird lime, a glue substance used to trap birds. It had trapped him.

Seconds later he was inside a nylon net. The men snapped the branch he was involuntarily gripping and wound the mesh around it, trapping him. The bird’s sharp hooked beak tore at the net but it wouldn’t give. Seconds later the blue macaw, still inside the net and glued to the perch, was caged in a wire mesh-fronted crate. He lay panting on the floor covered in glue, tangled in the net where he had no choice but to grip the branch to which he was stuck. He called out, but there was no answer; his companions were already far away. It was the end of April 1987.

The trapper and his assistant sat on the huge fallen trunk of a dead caraiba tree and smiled. Dressed in modern city clothes they had arrived in a four-wheel-drive vehicle, a rare sight in this poor area where local transport was more often by horse or mule. They smoked cigarettes and talked for a while. Then they rose to their feet and approached the crate. One of the men put on thick leather gloves while his assistant opened the door. The gloved man picked up the bird, still inside the net, while his companion cut away the nylon with a penknife. The parrot’s feet were prised from the broken branch and a scrap of cloth cleaned some of the glue from its feet. The blue bird, paralysed with fear, was put back into the crate and door once more wired fast.

The gloved man stood back and regarded his prize with obvious pleasure. The sight of the caged blue parrot took his thoughts back to when he was a boy of eleven. A neighbour had asked him to look after some young parrots he was rearing. Soon after the neighbour had had to leave the area and told the boy he could keep the birds. When they were ready for sale he put them in a cart and took them round the streets in his town and found that they sold very well. The boy got some more parrots and as time went by became more knowledgeable and serious about his surprisingly lucrative vocation. By the time he was seventeen he had bought himself a second-hand car; quite an achievement in this part of the world. He marvelled at his good fortune – the birds had helped him escape the grinding poverty suffered by the poor rural people in the caatinga. He was lucky enough to have a small house in town that he shared with his wife and three young children. He only came to the country for more parrots.

As the years went by, his reputation as a parrot dealer grew, first in Brazil and then internationally. If you wanted to buy a Brazilian macaw, he was your man. He had first caught some of the special blue caatinga macaws in the early 1980s when he took a couple of babies from their nest. He traded the azure bundles of fluff for a car; this time it was brand new. Since then he had not looked back. It was easy money; better still it was big money. Capturing another of these special blue parrots was a real achievement. The heavily built trapper had notched up yet another of the special blue prizes.

All kinds of blue macaw were in big demand and the trapper had caught the parrot to fulfil an order placed by a foreign bird collector. The obsession of the men who would own a blue macaw, if they could get one, was such that any bird caught could easily be sold. This one was no exception; it would now travel via a series of dealers working as part of the criminal underworld of the international illegal bird trade.

Unlike some common parrots, this one was not destined for a run-of-the-mill pet keeper. A member of the world’s bird-collecting elite would have this one. There were plenty of people who would happily part with a fortune for such a parrot and he would be sold to one of the real connoisseurs, a collector who would fully appreciate the rarity and value of such a trophy. All kinds of blue macaw fetched excellent prices but these caatinga macaws were different. This bird was like a Rembrandt or a Picasso, one of the finer things that only the really wealthy could afford. Unlike a painting by a great master, however, this bird was a temporary treasure only. One day he would die, his value would be gone and another would be demanded to replace him. No matter how many were caught, there was relentless demand for more.

As the long hot dry season passed, the traumatic memory of the trapping faded, but the surviving pair of blue parrots remained very nervous. Any people near the creek sent them into fast flight. The normal activities of the sparse local population, the odd ranch hand passing by on horseback, or people from one of the isolated houses nearby collecting leafy branches for their goats and sheep to eat, created panic. The birds took no chances even with these casual visitors. They would take flight up the creek until they had travelled what they regarded as a safe distance.

The pair of blue parrots nested in a particular hole that had been used by their kind for generations. High up in one of the big trees, it had been formed by the fall of a huge branch some five decades before. Almost every year since then a pair of the blue parrots had laid their eggs in that same favourite refuge. The hollow was dry and the nesting area was some distance down into the tree from the exit to the outside world. It was just right, the ideal place to rear babies. But such a location was valuable and the blue macaws didn’t have an exclusive claim.

Most of the best tree holes in the creek were accounted for in some way. The woodpeckers, black vultures, the other parrots, like the maracanas, and even snakes liked to use tree cavities as well. Lately, bees introduced from Africa had also moved into the creek. Swarms of these insects were especially dangerous when they wanted to take possession of a tree hole. They had killed parrots, stung them to death, so as to take over a prime site.

With the arrival of the wet season, the birds spent more time around the nest hollow, both to defend it from unwanted squatters and to prepare themselves for breeding. A couple of weeks later, in mid-December, the female bird stayed inside during the day. She had laid three white eggs; they rested in the bottom of the hollow where she would now devote most of her time to maintaining the correct temperature and humidity for the tiny embryos to grow and then hatch.

One night, when the two parrots were asleep with their eggs in the nest hole, the drone of a vehicle was heard once more in the creek. The birds would not venture out; owls were a real danger after dark. They sat tight even when they heard scraping sounds on the outside of the tree. They heard whispering human voices by the hole and huddled silently. But when they felt a presence come inside, they fled. The female made her move for the entrance first. In the darkness all she could see was the gloomy disc of the pre-dawn sky. She made for it, climbing the inside of the tree trunk, a familiar enough task in the day but in the near-total darkness unnatural and frightening. As she made her exit, and spread her wings for flight, she became constrained. She was in a net. Something powerful, hard and unyielding grasped her body. As she struggled to free herself from her captor, her mate struggled past and fluttered free of the hollow. He found his wings and took off down the creek into the darkness as fast as he could.

In the nest the three eggs lay smashed. The two trappers had reached inside for young birds in the hope that they could take baby macaws too; they would fetch an even better price than the sleek adult bird. They were too early for that, however, and their clumsy groping in the dark broke the fragile white shells and spilled the contents into the base of the hollow. The blood-streaked yolks slowly congealed in the wood shavings at the bottom of the nest chamber. Disappointed not to find chicks, the trappers were pleased that they at least had caught one of the adult macaws before someone else did. It was Christmas Eve 1987. The capture of the blue parrot would certainly brighten the trappers’ festivities.

The macaw soon found herself in a crate ready for loading into the back of the four-wheel-drive vehicle. It was now daylight and the men prepared for departure along the long dusty track that led back the main tarmac road. Just before leaving, they saw a man approaching on foot. He approached and then stopped to ask what they were doing.

The stranger seemed harmless enough, certainly not a policeman, so the trappers boasted about the valuable creature they had taken that morning. The man asked to see it. The chief trapper opened the rear door of the jeep and pulled an old blanket to one side revealing the blue bird in its crate. It recoiled at the sudden bright light and shrank back into the shadows. The man was impressed, he asked if he might take a photo of the gorgeous blue creature. After the trapper had shrugged his consent, the man took a Polaroid camera from his green bag, carefully composed his picture and pressed the shutter. He waited a few moments then peeled back the paper backing from the print to reveal the image of the caged parrot.

He did not know it, but the image that was gradually appearing on the Polaroid as it dried in the warm morning air was of the last wild female of the blue caatinga parrots. After her capture, only her partner remained. He was the last Spix.

2 The First Spix (#ulink_decdaa00-8a51-5de0-a263-ebda4c0ea6d7)

On 3 June 1817, Dr Johan Baptist Ritter von Spix and his travelling companion and fellow scientist Dr Carl Friedrich Philip von Martius set sail for the Atlantic Ocean from Gibraltar. They had arrived in the bustling port some weeks previously from Trieste in the Adriatic. Along with fifty other vessels of various sizes their ship had waited for the right weather conditions for their voyage to South America. This day brought the easterly winds necessary to propel them from the Mediterranean Sea on the 6,000-kilometre voyage to the southern hemisphere and their destination, Rio de Janeiro, the capital of the Portuguese colony of Brazil.

The son of a Bavarian doctor, Spix was born in 1781. Awarded his PhD at the age of only nineteen, his early academic career included studies in theology, medicine and the natural sciences. He qualified as a medical doctor in 1806. In 1808 he was awarded a scholarship by King Maximilian Joseph of Bavaria to study zoology in Paris, at the time the world’s leading natural sciences centre. Here the young Bavarian mixed with the leading biologists and naturalists of the time, including the French biologist Jean-Baptiste Lamarck, the intellectual giant who proposed a mechanism of evolution that would challenge (unsuccessfully as it turned out) the theory of natural selection developed some decades later by Charles Darwin.

In Paris, Spix’s abilities as a scientist grew; in October 1810 the King once again acknowledged his growing reputation, this time with an appointment in the Bavarian Royal Academy of Sciences where he was charged with the care and study of the natural history exhibits. Martius was a gifted academic too. Thirteen years younger than Spix, his interests were mainly botanical, especially palms.

The two scientists found themselves aboard one of two Brazil-bound ships as members of an expedition mounted in the name of the Emperor Francis I of Austria, whose daughter was to marry the son of John VI of Portugal. King John had been forced to live in Brazil following the invasion of his homeland in 1807 by Napoleon Bonaparte of France. The Austrian Emperor had invited a group of Viennese scientists to join the royal party that was to travel to Brazil. Maximilian had agreed that two members of the Bavarian Academy of Sciences should go with them.

Spix was to concentrate his effort on animals, the local people and geological recording, including the collection of fossils. Martius was to devote his energies to botanical investigation, including soil types and the study of how plants spread to new lands. The King was a bird collector in his own right and hoped that the two men would bring him novel and unique prizes from their expedition in the New World. ‘After everything possible was got ready, and the books, instruments, medicine chest, and other travelling equipage sent off direct to Trieste, we set out from Munich on 6 February 1817, for Vienna.’ At Trieste they joined the ships, two naval frigates, the Augusta and the Austria. Both were substantial vessels equipped with forty-four guns and a crew of 240 sailors.

On 29 June they crossed the equator and on 13 July Cabo Frio was sighted, ‘and soon after the noble entrance of the bay of Rio de Janeiro’.

(#litres_trial_promo) The arrival in South America made a big impression on the travellers.

Towards noon, approaching nearer and nearer to the enchanting prospect, we came up to those colossal rock portals and at length passed between them into a great amphitheatre, in which the mirror of the water appeared like a tranquil inland lake, and scattered flowery islands, bounded in the background by a woody chain of mountains, rose like a paradise full of luxuriance and magnificence … at length the capital of the infant kingdom, illuminated by the evening sun, lay extended before us.

A sensation, not to be described, overcome us all at the moment when the anchor struck the ground at another continent; and the thunder of the cannon, accompanied with military music hailed the desired goal of the happily accomplished voyage.

The travellers decided to spend some time initially in the relative cool and comfort of the south east of the country, first in Rio de Janeiro and then in São Paulo and Curitiba. Spix and Martius explained, ‘it seemed most expedient to journey first to the southern Captaincy of S. Paulo, mainly to acclimatise ourselves gradually to the hot conditions we would encounter during our travels and acquaint ourselves with this more temperate southern zone. From the Captaincy of S. Paulo we planned to travel through the interior of Minas Gerais to the S. Francisco River and Goyaz, before continuing either down the Tocantins to Pará or across the interior to Bahia and the coast, where we would arrange transport of our collections to Europe before penetrating the interior of the Captaincies of Piauhy and Maranhão to arrive finally at Pará, the goal of our desires.’

To a twenty-first-century traveller, such an itinerary would be demanding enough, entailing a journey of thousands of kilometres, mainly on rough tracks and by river. Although the Bavarians enjoyed the small luxury of letters of recommendation from the Portuguese – Brazilian Government that would help smooth their path with colonial administrators, they could carry only basic equipment, much of which was for scientific purposes rather than their personal comfort. They had incomplete maps, primitive medical supplies and could rely only on mule trails and rivers to cover the vast distances that lay ahead of them. In those times, natural history exploration was a hazardous business. Disease, attack from native people or wild animals, climbing and firearms accidents, starvation and even the use of dangerous chemicals for scientific purposes, like arsenic, all took their toll on the early naturalists.

Despite the dangers, it was with great enthusiasm and apparently little thought for their impending discomfort that on 9 December 1817 Spix and Martius set out from the coast for the interior of Brazil. Although misgivings about their venture were expressed by Brazilian friends, the Bavarians happily set off with a team that included a guide hired in Rio de Janeiro, a mule man, a drover, a ‘newly bought Negro slave’ and eight mules, two for riding and six more for their bags and equipment.

They met several early setbacks. In addition to being assailed by a huge variety of fleas, ticks, flies, mosquitoes and other biting and disease-carrying insects, the scientists’ guide decided to go his own way. He left one night, when everyone was asleep, never to be seen again. He had taken most of their valuables. Spix and Martius were forced to recruit new help and to replace stolen equipment before they resumed their journey through the recently colonised landscape.

The countryside was sparsely settled but in some places the clearance of the native vegetation was already well under way. They wrote that ‘From Ytú we advanced N.W. by the side of beautiful thick woods, and enjoyed a delightful view of the valley of the Tieté, which is now entirely cleared of the forests, and planted with sugar cane, beans, maize and so on.’ It was in this area that their slave decided to follow the earlier example of the guide and make an unscheduled departure himself.

According to Spix and Martius the slave ‘did not know how to appreciate our kind treatment of him, and embraced the first favourable opportunity to abscond’. He was, however, brought back to them next day by professional runaway slave hunters the men had engaged locally. The naturalists wrote ‘we followed the advice of our host, treating him, according to the custom of this place, very kindly … giving him a full glass of brandy.’

In addition to the departure of their staff, flooded roads, swollen streams and cold mist dogged their progress. But despite the difficult conditions the two scientists earnestly persisted with their scientific work. ‘If in the evening we at length met with an open shed, or dilapidated hut, we had to spend the greater part of the night in drying our wet clothes, in taking our collections out of the chests and again exposing them to the air.’ On drier days they would spend twilight and hours after dark ‘writing notes in the journals, in preparing, drying and packing our collections’. Despite the hardships, they recalled how ‘This simple mode of life had its peculiar charms.’

To early Portuguese visitors, Brazil was known as the land of parrots. Spix and Martius came across plenty of them as well. In August 1818, in the region of Januária in Minas Gerais in the upper reaches of the river São Francisco, the Bavarian travellers happened upon what were almost certainly Hyacinth Macaws in a ‘magnificent forest of buriti palms’. The large cobalt-blue birds circled over the travellers in pairs with their croaking calls echoing in the still and peaceful surroundings. A few days later, Martius and Spix briefly split up. Martius set off into the dry semi-arid forests that fringe the river São Francisco. Here he found forests of indaja palms, which, because of the much drier conditions, were the first palm groves that they had found ‘where we dared to roam around with dry feet and safe from giant snakes and alligators’.

Martius observed with fascination how the local Hyacinth Macaws greedily ate the palm fruits. ‘The large nuts of these palms with their very fine rich oil make them the favourite trees of the large blue macaws which often flew off in pairs above us. As beautiful as this bird’s plumage is, its hoarse penetrating call assaults even the most insensitive of ears and if it had been known in ancient times, would have been regarded an ominous bird of deepest foreboding.’

For the Hyacinth Macaw, the arrival of the Europeans was indeed a compelling omen of ill fortune. Martius’s party themselves captured some of the birds. He later remarked, ‘the small menagerie of these quarrelsome birds, which we took with us chained to the roof of a few mule loading platforms, played a special role in that their continuous noise, which could be heard from afar, indicated the location of the caravan, which we usually left far behind in our forays to investigate the region.’

Martius and Spix most likely knew about the Hyacinth Macaw before they arrived in Brazil. That species had by then been described to science by a British ornithologist, Dr John Latham. He had spent years cataloguing museum collections, including the birds collected during Cook’s eighteenth-century voyages in the Pacific. In 1790 he was the first to grant a scientific name to the giant blue parrots. But the two Bavarians were the first to note the relationship between these magnificent blue birds and different kinds of palms, upon the fruits of which they dined.

By November Spix and Martius reached the coast of eastern Brazil and the town of Salvador in Bahia. The grinding travel schedule had taken its toll, so they rested there until mid-February 1819 to recover their strength. They then set out north through the harsh drought-prone north east of Brazil. They suffered extreme hardships, notably lack of water, and often travelled in uninhabited country. By May they had reached the banks of the river São Francisco at Juàzeiro.

Along the north and south shores of the great river they found the thorny caatinga woodlands. This dry country stretched in all directions to the horizon and beyond. It was sparsely settled and mainly used for sheep and cattle pasture. In this strange dry land Spix spent some time collecting birds.

Among other things, it was here that he shot a magnificent long-tailed blue parrot for their collection. The bird was taken from some curious woodlands found along the side of creeks seen in that part of the caatinga. The specimen of the parrot was tagged and brief notes were made about it. Spix recorded that ‘it lives in flocks, although very rare, near Juàzeiro in the region bordering the São Francisco, [and is] notable for its thin voice.’ Spix didn’t realise that he had just taken the very first specimen of a bird that would one day symbolise how human greed and ignorance were wiping countless life forms from the record of creation.

From Juàzeiro the pair travelled through the parched woodlands north along the river Caninde to Oeiras in Piauí, close to the modern city of Floriano. Martius wrote ‘The caatingas mostly consisted of sparse bushes and in the lowland areas, where there was much more water, the carnauva palms formed stately forests, the sight of which was as strange as it was delightful. Blue macaws, which live in the dense tops of these palms, flew up screeching above us.’ It seemed that the travellers had happened on more Hyacinth Macaws or perhaps their rarer and smaller cousins, Lear’s Macaws – one of the ‘four blues’ exhibited in Berlin in 1900 (see chapter 4).

By the end of 1819 Spix and Martius had worked their way inland about 3,000 kilometres further west, mainly by river, penetrating deep inside the seemingly limitless rainforests of the Amazon basin. From here they split up and travelled further into the vast interior of South America. They finally arrived nearly 3,000 kilometres further downstream at the port of Belém in Pará at the mouth of Amazon on 16 April 1820. Their collection of specimens and live animals was loaded aboard the Nova Amazonia and they set sail for Lisbon. They travelled through Spain and France to arrive back in Munich on 10 December 1820, nearly four years after they had left.

Throughout their extensive travels Spix and Martius made careful observations and notes on the wildlife they encountered. They were also careful to note details of the local economy in the places they visited, especially mining and agriculture, and in so doing they painted a picture for those who would follow of investment, trading and other commercial opportunities. It is no coincidence that the greatest concentration of German industry anywhere in the world today is still in the Brazilian super metropolis of São Paulo. Certainly this fact is linked to the historical relationships between the two countries and the commercially significant information provided by early travellers. Thus commenced centuries of encroachment into the world’s biologically richest and remotest places – a process that continues today, only now hugely accelerated and more often with the aid of remote sensing from spacecraft than with the assistance of mules.

Spix and Martius recorded their travels in three substantial volumes published in 1823, 1828 and 1831 in which they dedicated their great scientific achievements to their royal patron. ‘Attachment to Your Majesty and to the sciences was the Guardian Genius that guided us amidst the danger and fatigues of so extensive a journey, through a part of the world so imperfectly known, and brought us back in safety, from that remote hemisphere to our native land,’ they wrote. But only the first volume was a joint venture. Martius completed volumes two and three alone following the death of Spix in 1826. He was forty-six and had never really recovered from extremely poor health that resulted from the privations and sickness he experienced in Brazil. Martius went on to write a classic work on palms that he completed in 1850. He died in 1868.

Not only was the account of what they saw of great importance; their collection made a substantial contribution to the Natural History Museum of Munich. They brought back specimens from 85 species of mammals, 350 species of birds, 116 species of fish, 2,700 insects and 6,500 botanical specimens. They also managed to bring live animals back, including some parrots and monkeys. Many of their specimens were from species of animals and plants new to science.

Among the treasures brought home to Bavaria was the blue parrot shot by Spix near to Juàzeiro in the north of Bahia, not far from the river São Francisco. Since it was blue with a long tail, it seems that Spix believed he had taken a Hyacinth Macaw.

It was customary by this time for all species to be assigned a two-part name, mainly in the then international scientific language of Latin – but also Greek – following the classification system proposed during the eighteenth century by the Swedish naturalist Carl von Linné, better known as Linnaeus. The idea was to avoid the confusion often created by the use of several different colloquial names by adopting a common international system. The first part of the name denoted the genus, that is the group of closely related creatures or plants to which the specimen belonged. The second half of the title was to identify the particular species.

Whether he knew about Latham’s name for the blue parrot or simply used the name in ignorance (this occurred quite commonly in the early years of natural history classification), Spix confusingly called the little blue caatinga macaw Arara hyacinthinus in his volume called Avium Brasiliensium Species Novae published in 1824–5. He also had specimens of the larger, and similarly blue, Hyacinth Macaws that he proposed be renamed Anodorhyncho Maximiliani. ‘Anodorhyncho’ was a new name proposed by Spix to denote the genus of large blue macaws to which it belonged, and ‘Maximiliani’ was in honour of the King who had sponsored his explorations in South America.

The confusion that Spix evidently experienced in naming his blue parrots was quite understandable. Unlike modern naturalists, Spix was not able to rely on a glossy field book that succinctly set out with accurate colour pictures, maps and clear descriptions what birds he might encounter on his travels through the interior of Brazil. Even now, at the start of the twenty-first century, there is still no handy field and identification guide for Brazilian birds, although Helmut Sick’s 1993 Birds in Brazil provides a comprehensive overview of birds occurring in the country. It is worth noting that many dozens of guides are available for European birds, a portion of the globe with far fewer endangered species.

With no manual to rely on, it was not a straightforward business for Spix to recognise new species, let alone ones that had already been collected by other museums or expeditions. For a start, any naturalist seeking to catalogue a vast and diverse country like Brazil, even for a relatively obvious and distinctive group of animals like birds (even large blue parrots), would need a basic understanding of what had already been collected and what typical geographical variations might be expected over different species’ sometimes vast ranges. Such knowledge in early nineteenth-century Bavaria was, as elsewhere, extremely scarce.

It was not until 1832, six years after Spix’s death, that the magnitude of his error became apparent. The blue parrot he had collected in the caatinga, and so carefully transported all the way back to Munich, was utterly unique, unlike anything else ever catalogued: Spix had found a new species. It later emerged that not only was it a species new to science, it was a representative of a whole ‘new’ genus.

Spix’s mistake was noticed first by another Bavarian naturalist, his assistant Johann Wagler. Wagler, a Professor of Zoology at the University of Munich, realised that the bird collected by Spix was smaller than the birds previously described as Hyacinth Macaws and was a different colour too. It had a greyish head, black bare skin on its face, instead of the yellow patches seen in the Hyacinth, and it had a smaller and more delicate bill than the bigger Hyacinth Macaw and its relatives.

In his Monograph of Parrots published in 1832, Wagler paid tribute to the bird’s collector in the naming of a ‘new’ species after him; Sittace Spixii, he called it – a name basically meaning ‘Spix’s Parrot’. Wagler, like Spix, completed his bird book just in time. That same year, Wagler was involved in a shooting accident. He peppered his arm with small shot while out collecting birds. He contracted blood poisoning, amputation was fatally delayed and he died in the summer, aged thirty-two.

Following Wagler’s realisation that a species new to science had been found, the French naturalist Prince Charles Bonaparte proposed in the 1850s that it be placed in a new genus called Cyanopsittaca. Bonaparte, the son of Napoleon Bonaparte’s brother Lucien, was a passionate ornithologist who had a special interest in parrots. Since this bird was unlike the other blue macaws in several important respects, Bonaparte believed that a whole new genus of parrots was warranted. He took the Greek word for blue, Kyanos, and the Latin for parrot, Psittacus, to denote a new genus literally meaning ‘blue parrot’.

In the 1860s in a monograph of parrots compiled by the German ornithologist Otto Finsch there is an everyday German name that translated means ‘Spix’s Blue Macaw’. Finsch wrote that the small blue macaw was easy to distinguish from the Hyacinth Macaw because of its smaller size and more bare skin on its face and around its eyes. He concluded that it was ‘An exceedingly rare species and found in few museums. Discovered by Spix on the river São Francisco at Juàzeiro’. Significantly, he wrote that, ‘Other travellers do not mention it at all.’

Three decades later, the Italian zoologist Count Tommaso Salvadori compiled the Catalogue of the Parrots in the Collection of the British Museum. Salvadori completed his two-year task in 1891. He retained Spix’s bird in a genus called Cyanopsittacus. The fact that no other birds quite like it had been discovered meant that it remained in the genus on its own, thereby signalling that it was quite unique with characteristics seen in no other bird.

The second half of its scientific name was spixii. From now on, the bird collected in 1819 by the river São Francisco would be known in its scientific Latin form as Cyanopsittacus – or more commonly today Cyanopsitta spixii, and in English as Spix’s Macaw.

The fact that the species was now officially recorded was, however, to prove a mixed blessing. It intrigued not only scientists, but also conservationists and collectors, the former seeking to save the species, the latter to own and possess the most sought-after of all birds. But the blue caatinga parrots were to prove an elusive quarry for all concerned.

Astonishingly, Spix’s Macaw effectively disappeared from the eyes of naturalists and travellers, and was not observed in the wild for eighty-four years after Spix had first encountered one. The fact that Spix’s Macaw was a rare bird was not lost on the early cataloguers and naturalists. Indeed, no European recorded one alive in the wild again until the start of the twentieth century when Othmar Reiser saw Spix’s Macaws during an expedition of the Austrian Academy of Sciences to north-eastern Brazil in June 1903.

He wrote, ‘As I knew that Spix had discovered this rare and beautiful parrot in the area of the river São Francisco near Juàzeiro, I made sure to keep an eye out for it in the area described. Unfortunately without success. Any enquiries made to the local people were also negative.’ Finally, at the lake at Parnaguá in the state of Piauí, more than 400 kilometres to the west of Juàzeiro, Reiser and his companions were rewarded with two sightings of the elusive blue bird. They reported one sighting of three birds and another of a pair. ‘They arrive apparently from a long distance and the thirsty birds at first perch, calling, on the tops of the trees on the beach to survey the surrounding area as a precaution. After flapping their wings for a few times they fly down to the ground with ease and drink slowly and long from pools or the water at the bank.’

(#litres_trial_promo)

Reiser tried to approach but found the birds nervous and not tolerant of people. His attempts to shoot the macaws in order to obtain a specimen failed. ‘So it was that the parrot species most desired by us was the only one to be observed, but not collected’, he wrote. The only other encounter with Spix’s Macaw noted during this expedition was a captive bird shown to the party in the town of Remanso. Reiser tried to buy it, but lamented that it was not for sale.

But other Spix’s Macaws were for sale. Despite the lack of scientific observations by naturalists working in the field, the blue parrots were certainly leaving Brazil for a life in captivity overseas.

In 1878, the Zoological Society of London at Regent’s Park had obtained a live bird for its collection from Paris. It died and so the zoo set out to get hold of a replacement. In November 1894, a second bird was procured for the Society by Walter Rothschild: that one lasted until 1900. A third was held at the London Zoo from June 1901 but expired after just a year. These individuals were among a steady trickle that by the late nineteenth century were being exported to meet a growing demand for live rare parrots. In common with other rare species, when these birds died they were often included in museum collections. Following the demise of the first Zoological Society specimen, its skin was preserved and placed in the collection held by the British (now Natural History) Museum at Tring in Hertfordshire. The second London bird’s skin is now kept in the American Museum of Natural History in New York. And it wasn’t only the large zoological institutions like London that were interested in owning them. In late Victorian England, as in other parts of the world, aviculture was growing in popularity, and private bird collectors certainly knew of the Spix’s Macaw as a rare and desirable addition to a parrot fancier’s aviaries.

In the December 1897 issue of Avicultural Magazine, a journal for serious bird keepers, the Honourable and Reverend F. G. Dutton from Bibury in Gloucestershire wrote, ‘Have any of our members kept a Spix? I have seen only two – one that our zoo acquired some years ago from the Jardin d’Acclimatation [in Paris], and one bought by Mr Rothschild … They were both ill tempered: but as the first had a broken wing, it had probably been caught old. I was greatly tempted by the offer of one from Mr Cross the other day, but there are so many calls on a parson’s purse, that he cannot always treat himself to expensive parrots. I ought to have been keeper at the parrot-house in the zoo.’ Although he does not mention a price, it is clear that even in the late nineteenth century Spix’s Macaws were the preserve of the more discerning and wealthier bird collectors.

After Dutton had published his request for details on any Spix’s Macaws kept in Britain at that time, a Mr Henry Fulljames of Elmbourne Road in Balham, London, came forward. The Reverend soon paid Fulljames a visit at his house to view his parrot collection. Dutton wrote, ‘Lastly, the most interesting bird was the Spix’s Macaw … It was very tame and gentle, but not, as regards plumage, in the best of condition. I never can see a bird in rough plumage without longing to get it right. And so it has been arranged between Mr Fulljames and myself that I should have the Spix at Bibury, and try what a little outdoor life might do for it.’ Although Dutton had hatched an apparently foolproof plan to have a Spix’s Macaw for free, at least temporarily, Henry Fulljames’s housekeeper put an end to the scheme. She was very reluctant to lose sight of the Spix’s and the bird stayed where it was.

The Reverend persevered, however, and by September 1900 he had acquired a Spix’s Macaw of his own. ‘My Spix, which is really more a conure than a macaw, will not look at sop of any sort,’ he wrote, ‘except sponge cake given from one’s fingers, only drinks plain water and lives mainly on sunflower seed. It has hemp, millet, canary and peanuts but I do not think it eats much of any of them. It barks the branches of the tree where it is loose, and may eat the bark. It would very likely be all the better if it would eat bread and milk, as it might then produce some flight feathers, which it never yet has had.’ He later wrote that his Spix’s Macaw, which lived in his study, was learning to talk.

The Reverend Dutton was not the only one to wonder if Spix’s Macaw might not be closer to the conures than the other macaws. Conures are slender parrots with long tails. They are confined to the Americas and are mainly included in two genera: Aratinga and Pyrrhura. Several writers repeated Dutton’s conjecture, but given the many macaw-like characteristics of Cyanopsitta it is safer to assume that it is a macaw.

By the early twentieth century, Spix’s Macaws were well known among bird keepers, at least from books. In Butler’s 1909 Foreign Birds for Cage and Aviary, the author refers to the earlier published claims that Spix’s Macaws are bad-tempered birds. ‘As all bird keepers know well,’ Butler wrote, ‘it is impossible to be certain of the character of any species from the study of one or two examples only. Even in the case of birds which are generally ill tempered and malicious, amiable individuals may occasionally be met with. Moreover circumstances may alter cases, and a Parrot chained by the leg to a stand may be excused for being more morose than one in a roomy cage.’ Butler, in common with previous commentators, remarked that Spix’s Macaws were extremely rare.

Another famous aviculturist in the early part of the twentieth century was the Marquis of Tavistock. In his book on Parrots and Parrot-like Birds in Aviculture published in the 1920s, he remarked that, ‘This rather attractive little blue macaw was formerly extremely rare, but a few have been brought over during recent years. It is not noisy, is easily tamed and sometimes makes a fair talker. There seems to be little information as to its ability to stand cold or as to its behaviour in mixed company, but it is probably neither delicate nor spiteful … In the living bird the feathers of the head and neck stand out in a curious fashion, giving a peculiar and distinctive appearance.’

While birds occasionally turned up in collections, attempts to find Spix’s Macaws in the wild were repeatedly frustrated. In 1927, Ernst Kaempfer had been in the field with his wife collecting birds in eastern Brazil for two years. Although the Kaempfers had managed to ship some 3,500 bird specimens back to the American Museum of Natural History in New York City, the Spix’s Macaw still eluded them.

Following a search on the north shore of the river São Francisco near to Juàzeiro, Kaempfer wrote that

The region is one of the ugliest we have seen on the whole trip. No forest or anything alike; the vegetation is a low underbrush and open camp where grass only grows. The river is very large here forming on both shores large strips of swamp; the latter ones without any particular bird life besides small Ardeidae [heron family] and common rails. Owing to the character of the country the collection we could make was small only. All questions about Cyanopsitta Spixii that Spix discovered here a hundred years ago were fruitless, nobody knew anything about such a parrot.

The only Spix’s Macaw that Kaempfer was able to track down was a captive one that he saw at Juàzeiro railway station, another bird taken locally from the wild and about to embark by train on the first leg of a journey to lead a life in distant and obscure captivity.

In the early twentieth century, the only certainty surrounding Spix’s Macaw was its scarcity. As Carl Hellmayr, an Austrian naturalist studying the birds of South America with the Field Museum of Natural History in Chicago, put it in 1929: it is ‘one of the great rarities among South American parrots’. Indeed, during the entire first half of the century, the only other possible record of the species in the wild, apart from Reiser’s in 1903, was a vague mention from Piauí before 1938.

(#litres_trial_promo) This report, from the extreme south of the dry and remote state, was in an area of deciduous woodlands that comprises a transition zone between the arid caatinga and the more lush savannas of central Brazil.

The species was not heard from again in the wild until the 1970s. Various collectors and zoos however owned Spix’s Macaws. Living birds were exported from Brazil to a wide variety of final destinations. Several went to the United States, where one was for example kept in the Chicago Zoo from 1928 for nearly twenty years. Others finished up in the UK, where several private collectors and zoos, such as Paignton in Devon and Mossley Hill in Liverpool, kept them. In all, there were up to seven in the UK in the 1930s. At least one was kept in Ulster during the late 1960s; a recording of this bird’s call is in the British Library of Wildlife Sounds. Spix’s Macaws were also kept in The Netherlands at Rotterdam Zoo and in Germany. One spent some time at the Vienna Zoo during the 1920s, while at least a pair had been imported to Portugal from Paraguay.

Spix’s Macaws were also supplied to collectors in Brazil itself and at least one was successful in breeding them. During the 1950s a parrot collector called Alvaro Carvalhães obtained one from a local merchant and managed to borrow another from a friend. They fortunately formed a breeding pair – by no means a foregone conclusion with fickle parrots – and after several breeding attempts young were reared. Carvalhães built up a breeding stock of four pairs that between them produced twenty hatchlings. One of these later finished up in the Naples Zoo. The rest remained in Brazil where they were split up with another breeder, Carvalhães’s friend and neighbour, Ulisses Moreira. The birds began to die one by one as time passed, but the final blow that finished off Moreira’s macaws was a batch of sunflower seeds contaminated with agricultural pesticides. This killed most of the parrots in the collection, including his Spix’s Macaws.

Although there was evidently a continuing flow of wild-caught Spix’s Macaws during the 1970s to meet international demand in bird-collecting circles, the openness with which collectors declared the ownership of such rare creatures sharply declined in the late 1960s. At that point, the trade in such birds was attracting the attention of agencies and governments who were increasingly concerned about the impact of trapping and trade on rare species.

Brazil banned the export of its native wildlife in 1967

(#litres_trial_promo) and the Spix’s Macaw became further prohibited in international trade under the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES) in 1975.

(#litres_trial_promo) With effect from 1 July that year, all international commercial trade in Spix’s Macaws between countries that had ratified the Convention was illegal, except in cases where the birds were involved in official captive-breeding programmes, or were being transferred for approved educational or scientific purposes.

This new legal protection didn’t stop the trade, however; it simply forced it underground. To the extent that the trafficking was increasingly secret, the volume of commerce and the final destinations for birds being captured was unknown to anyone but a few dealers, trappers and rare parrot collectors. Despite the increasingly clandestine exploitation of wild Spix’s Macaws and a near-total absence of details about its impact, it was becoming ever more clear that the species must be in danger of extinction in the wild. The blue parrot first collected by Spix would come to symbolise a bitter irony: people’s obsessive fascination with parrots was paradoxically wiping them out.

3 Parrot Fashion (#ulink_ce1dc24c-4f2d-58d3-8092-0674a50c82d6)

Parrots are surprisingly like people and can bring out both the best and worst in humans. From love and loyalty to greed and jealousy, the human qualities of parrots can provoke the most basic of our human responses in their keepers. Perhaps that is why for centuries parrots have been our closest and most cherished avian companions.

There are hundreds of kinds of parrot. The smallest are the tiny pygmy parrots of New Guinea that weigh in at just 10 grams – about the size of a wren or kinglet. These minuscule parrots creep like delicate animated jewellery along the trunks and branches of trees in the dense, dark rainforests of New Guinea. The heaviest parrot, the rotund nocturnal Kakapo (Strigops habroptilis) of New Zealand, grows up to 300 times larger. These great flightless parrots, camouflaged so they resemble a huge ball of moss, can weigh up to 3 kilos.

(#litres_trial_promo)

Some parrots are stocky with short tails, others elegant with long flowing plumes. The smaller slender ones with long tails are often known as parakeets (the budgerigar, Melopsittacus undulata, is one), while it is the stouter birds that most people would generally recognise as ‘parrots’. The mainly white ones with prominent crests are called cockatoos and the large gaudy South American ones with long tails macaws. Despite this remarkable diversity, all of them are instantly recognisable, even to lay people, as members of the same biological family. The unique hooked bill, and feet, with two toes facing forwards and two backwards, identify them straight away.

Where the parrots came from is a baffling biological question. Many different ancestries have been suggested, including distant relationships with birds as diverse as pigeons, hawks and toucans. Even with modern genetic techniques it has not been possible to unravel the ancestral relationships between parrots and other modern birds. What is known, however, is that parrot-like birds have been around for a very long time.

The oldest parrot is known from a fossil found by a Mr S. Vincent in 1978 at Walton-on-the-Naze in Essex, England. The tiny fragile clues that these diminutive birds ever existed were painstakingly investigated by scientists who identified the species as ‘new’: they named the creature Pulchrapollia gracilis. ‘Pulchrapollia’ translates literally as ‘beautiful Polly’, and ‘gracilis’ means slender.

This ancient parrot was small and delicate – not much larger than a modern-day budgie. Its remains were found in Early Eocene London Clay deposits dated at about 55.4 million years old. More remarkable than even this great antiquity is the suggestion that parrots might have been around even earlier. A fossil bird found in the Lance Formation in Wyoming in the USA might be a parrot too. If it is, it would demonstrate the presence of such birds in the Late Cretaceous, more than 65 million years ago, thereby confirming that parrots coexisted with the animals they are ultimately descended from: the dinosaurs. Awesome antiquity indeed.

(#litres_trial_promo) To place this ancestry in perspective, the earliest modern humans (Homo sapiens) are believed to have appeared only about 200,000 years ago.

Across the aeons of biological time since the first parrots appeared, the group has evolved into one of the world’s largest bird families. Of the 350 or so species of parrot known today, some are widespread, others confined to tiny areas. In either case, most species are found in the warm tropical latitudes. Some do, however, brave freezing temperatures in high mountains in the tropics, for example the high Andes, or extend into cooler temperate areas, such as New Zealand and southern South America. The Austral Conure (Enicognathus ferrugineus) for example toughs out a living in the raw cool climate of Tierra del Fuego, while the Antipodes Parakeet (Cyanoramphus unicolor) occupies the windswept outpost of Antipodes Island and neighbouring rugged islets in the Pacific well to the south of New Zealand. The Andean Parakeet (Bolborhynchus orbygnesius) has been recorded on the high montane grasslands at over 6,000 metres in the high Andes.

The majority of the world’s parrot species are found today in South America, Australia and New Guinea. The single country with most species is Brazil: over seventy different kinds are known from there. In mainland Asia from Indochina to Pakistan and in Africa there are remarkably few. This uneven distribution appears to be linked to the break-up of the ancient supercontinent of Gondwanaland.

(#litres_trial_promo) Whether people have as yet documented the existence of all the living parrots is an open question. Three species of parrot new to science have been found since the late 1980s.

(#litres_trial_promo) All are from South America and amazingly have waited until the Space Age to be noticed, let alone studied.

Though we still know little of these birds’ place in nature, parrots have become uniquely familiar to humans and have been closely associated with people for centuries. The oldest document in the literature of the Indian subcontinent is the Rigveda, or Veda of the Stanzas, of about 1,400 BC. This ancient work, written in Sanskrit, remarks on the great fidelity of parrots and records how in the mythology of that time they were symbols of the moon.

The Ancient Greeks were also well aware of parrots. The historian and physician Ctesias travelled widely in the East in around 400 BC. As well as holding the great distinction of producing the first published account of unicorns, he also brought news to Europe of curious human-like birds kept by the natives in the lands he visited. Aristotle wrote some 100 years later about a parrot, but he may not have seen it himself because he described it, presumably on the strength of its hooked bill, as a kind of hawk.

During his conquests of the fourth century BC the Macedonian general Alexander the Great marched through Afghanistan to the Indus valley in modern-day Pakistan. There his men acquired parrots that were later brought home with their other spoils of war. Alexander was probably the first person to bring live parrots to Europe. They were medium-sized green parakeets marked with black on the face and with maroon patches on the wings. They had long tails and a shrill cry. They are today known as Alexandrine Parakeets (Psittacula eupatria).

After Alexander’s conquests, the expansion of trade between the Greek city states and the Orient ensured that Europeans would soon become more familiar with parrots. In the second century BC the earliest known picture of a parrot was produced in a mosaic at the ancient Greek city of Pergamum.

The Greek historian Diodorus Siculus wrote in 50 BC about parrots he had seen in Syria. Since no parrot is native to that country today, they were most likely imported; probably from Africa. In AD 50 Pliny described parrots that he said were discovered by explorers sent to Egypt. Although these birds are not known to occur naturally in Egypt now, they might have been imported from the savannas beyond the desert, or it might have been that the desert was less extensive than it is today. Other accounts of the same birds gave their origin as India. Since there is only one parrot in the world that has a natural distribution that embraces both Africa and India it is very likely that these birds were Ring-necked Parakeets (Psittacula krameri). This species is one of the most widespread, adaptable and common parrots in the world today, and has a long history of living with people.

Ring-necked Parakeets were, for example, prized in Ancient Rome where they were kept as pets. So valuable did they become that they were often sold for more than the price of a human slave. Demand was intense, so a brisk trade built up with birds brought into Europe in large numbers. They were kept in ornate cages made from silver and decorated with ivory and tortoiseshell. Noblemen carried the birds through the streets of Rome as a colourful accessory. The statesman and philosopher Marcus Cato wrote, ‘Oh, wretched Rome! What times are these that women should feed dogs upon their laps and men should carry parrots on their hands.’ Some parrots, however, found a less fortunate fate in Rome. During the rule of Emperor Heliogabalus from 222 to 205 BC they became a table delicacy. Not only that but they were fed to his lions too, along with peacocks.

With the decline of Rome and its excesses, parrot keeping faded in Europe. A few Ring-necked Parakeets made it back with Crusaders and merchants during the Middle Ages and Marco Polo came across cockatoos in India, although they are not native to the Subcontinent and presumably had made their way there on the trade routes from further east. Today the most westerly distributed naturally occurring cockatoos are found in islands in the Moluccan Sea and in the Philippines. French sailors also found African Grey Parrots (Psittacus erithacus) in the Canary Islands. They had been imported there from West Africa. These parrots were found to be excellent talkers and by the middle of the fifteenth century a steady flow of birds to the islands had been established from Portuguese trading posts along the African coast.

Popular, colourful and in short supply, parrots once again became expensive status symbols. During the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries – the great age of exploration – the fact that parrots were fashionable, in big demand and valuable meant that sailors travelling to new lands in tropical latitudes were on the look-out for them.

When Columbus returned to Seville in 1493 from his first expedition to the Caribbean, the parrots he brought back were displayed at his ceremonial reception. He had obtained the birds from natives who had tamed them. A pair was presented to his royal patron, Queen Isabella of Castile. These parrots were probably the species of bird from the genus Amazona that remains native to Cuba and the Bahamas today, the Cuban Amazon or Cuban Parrot (Amazona leucocephala).

As the Conquistadors pressed their explorations throughout the islands and deeper into the mainlands of Central and South America, they found the practice of taming and keeping parrots was commonplace among the local populations. There is every reason to believe that the indigenous peoples of the tropics have kept parrots for thousands of years, and certainly for a lot longer than Europeans, a practice that many tribal societies continue to this day. Forest dwelling peoples with an intimate knowledge of their surroundings took the colourful birds to the heart of their culture where they became prized and revered possessions. Small-scale collecting by indigenous people for local trade was, however, very different from the approach of the Europeans. The foreigners had wholeheartedly embarked on their globalisation adventure and wanted volume supplies for the mass markets back home.

The parrots and the forest people were to have a lot in common. One was to face biological oblivion, the other cultural genocide. There is a story from 1509 in which the tame parrots belonging to local villages raised the alarm about an impending attack. Perched in the trees and on huts around a village, the birds screamed and shouted at the approach of Spanish soldiers, thereby enabling the local population to escape from their assailants into the forest. But the alliance of birds and ‘Stone Age’ humans was no match for muskets and axes. They did not resist the might of the colonial powers for long. The birds and the forests were soon victims of an unprecedented age of plunder.

In the 1500s the plumage of brightly coloured birds became fashionable for personal ornamentation. Taxes levied on the Indian populations recently subjugated by European armies were partly paid in macaw feathers. The long plumes of these birds were naturally collectable, desirable, exotic and beautiful. European consumers wanted them and would pay handsomely. Feathers were one thing, whole birds quite another. As the voyages of novelty-hungry explorers penetrated more and more remote localities, so the variety of parrots brought home increased. In 1501, Portuguese sailors brought the first macaws back to Europe from Brazil. The birds were known to the local people as ‘macauba’ and were probably Scarlet Macaws (Ara macao). Such birds were to become among the most desirable of all parrots to cage and own. Later on, a blue one would also enter the trade. That creature, the Spix’s Macaw, would become the most valuable of all.

In 1505 parrots were imported to England. They were an instant success and became fashionable accessories, at least for the better off. In addition to his six wives, Henry VIII kept one (an African Grey) at Hampton Court. A portrait of William Brooke, 10th Baron Cobham, with his family painted in the middle 1500s hangs at Longleat House in Wiltshire, England. It portrays a family dressed in typical Tudor clothes seated around a meal table. A parrot stands among the dishes of food. It looks like some species of amazon but is not any bird we know today.

Being vegetarian and able to thrive on a diet of seeds and fruits,

(#litres_trial_promo) parrots could endure the long sea voyages that would kill most insectivorous birds. The trade became more regular and grew increasingly lucrative as the birds’ popularity soared. The establishment of Portuguese and Dutch colonies in Asia would soon ensure a supply of birds from the East too.

Mass-produced metal cages meant that the birds became more widespread in captivity as the ever-expanding supply of wild parrots brought down prices. When zoological gardens were opened in European cities during the nineteenth century, the cheeky, colourful parrots were an instant hit with the public. London Zoo was the first scientific zoological garden in the modern world. It was founded in 1828 and opened its gates on the fringes of the green expanse of Regent’s Park as a means to fund the scientific work of the London Zoological Society. Parrots were a big draw; so a special building, the Parrot House, was opened.

The red-brick Parrot House at the Zoo today is an essential part of the gardens’ character and stands as a monument to the popularity of parrots during Britain’s imperial age. Many of the parrots that have passed through there are among the rarest, most beautiful and coveted creatures in the world. Spix’s Macaws were fleetingly among them, but in an age when the fragility of our world was undreamt of, little or no thought would have been spared for the precariousness of these birds’ existence.

In those times, the complete disappearance of entire species through collecting must have seemed a most unlikely prospect. During this colonial age in which collecting was obsessive, the accumulation of animals would not have seemed very different from amassing, cataloguing and displaying inanimate objects. Today we know better. While our forebears took precautions to safeguard paintings, statues and other works of art for posterity, they could not fully understand the implications of hoarding these precious living creatures.

Even though the individual feathered treasures could not be preserved indefinitely, the rise of zoological gardens contributed to the growing familiarity and popularity of parrots to the point where such birds gradually took on symbolic values. Parrots came to stand for exotic places, tropical forests, colour and intelligence. These aspects of the birds’ appeal was in turn ruthlessly exploited by advertising and marketing executives.

The earliest example of parrots being used for sales purposes was in ancient India where high-class prostitutes carried a parrot on their wrists in order to advertise their profession. In the age of the mass media these birds have reached vast audiences to sell a wide array of products. One television advertisement had an amazon parrot playing the role of a talkative companion to a pirate. This was to sell rumflavoured chocolate.

Other parrots appeared in promotions for fruit drinks and tropical holidays, while a major British food retailer in 2001 adopted the ‘Blue Parrot Café’ brand for a range of children’s foods, featuring a blue macaw chosen for its friendliness and intelligence, and the sharp eyes it would need to select the very best ingredients. Gaudy Scarlet Macaws are the symbol of a Central American airline based in El Salvador: the fact that such birds are now extinct in that country has not deterred the marketing people. For obvious reasons, parrots have also repeatedly featured in promotions for telecommunications and copier products. This promotional use of parrots further elevated their popular familiarity. Inadvertently, it also further stimulated demand for the birds as pets.

Today, a large majority of the world’s different species of parrot are held somewhere in captivity. One estimate is that between 50 and 60 million of them are kept worldwide. Hundreds of parrot, parakeet, cockatoo and macaw clubs and societies exist for enthusiasts. They have hundreds of thousands of members drawn from the many millions who keep parrots of some sort.

The most widespread parrot in captivity today is the humble budgie. These pretty little green parakeets were first brought back from Australia in 1840 by John Gould, and since then have been effectively domesticated. The word budgerigar appears to be derived from the name given to the bird by Australia’s Aboriginal people. Budgies are probably the commonest pets after dogs and cats and have been bred in captivity for hundreds of generations into a variety of colour variants, including white, blue and yellow.