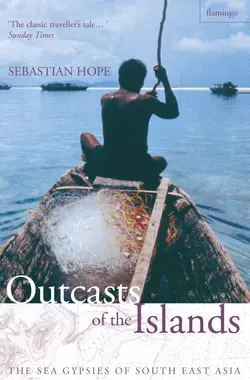

Outcasts of the Islands: The Sea Gypsies of South East Asia

Sebastian Hope

An enchanting tale of travels among South East Asia’s Sea Gypsies, scattered groups of semi-nomadic fisher people who occupy the spaces between the islands.A glance at the map of South East Asia reveals more blue than green, more sea than land. By separating the islands of the Malay Archipelago the sea has created diversity; by joining them together it has enabled trade and laid them open to influences from China, India and the Middle East. All Malays were sailors once – their ancestors reached the islands by boat – and the sea holds a central place in the Malay experience and imagination.The Sea Gypsies who still occupy this realm seem to live still in the hidden world of Conrad’s tales. They form social co-operative groups, each with its own territory, and move between established anchorages within that range, following the changing currents, seasons and fishing opportunities, and are specialists at exploiting the coral reefs. They have an oral tradition which accounts for their origins with myths of floods and tidal waves. Their hunter-gatherer lifestyle and a belief system that is at root a blend of animism, ancestor worship and sympathetic magic are characteristics they share with the early Malay cultures.Sebastian Hope travels and lives with groups of Sea Gypsies in both the east and the west of South East Asia, experiencing their subsistence lifestyle, unchanged for centuries. Travelling to fish and fishing to live, like the Sea Gypsies themselves he relies solely on his skills as a sailor and fisherman to survive.

Copyright (#ulink_704c78d5-c3e7-5738-a82b-b23537afbfc0)

HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

Published by HarperCollinsPublishers 2001

Copyright © Sebastian Hope 2001

Maps © Jillian Luff 2001

The Author asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the nonexclusive, nontransferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse-engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins e-books.

Source ISBN: 9780002571159

Ebook Edition © DECEMBER 2013 ISBN: 9780007441099

Version: 2016-07-19

HarperCollinsPublishers has made every reasonable effort to ensure that any picture content and written content in this ebook has been included or removed in accordance with the contractual and technological constraints in operation at the time of publication.

Dedication (#ulink_aedd55fc-baf0-5af1-9704-ed1ac4279bff)

For Lisa

Contents

Cover (#u5b872e27-74a7-5847-8873-20119c7059fb)

Title Page (#ub9894989-8e64-56f8-a91e-cc64b3e1d07e)

Dedication (#ulink_cb3ee00e-c67d-5317-98b1-043c92102f57)

Maps (#ulink_084b667e-9012-58de-b5c4-edb2d0d00198)

Sarani’s Boat (#ulink_c7973305-5896-54e6-8813-e215f36570c3)

One (#ulink_5e916076-30ff-5720-bac6-105b0097f4f5)

Two (#ulink_44535a03-5da4-568d-b88c-18c05b00ed4f)

Three (#ulink_7a0a6a75-db88-59f9-b9aa-9a3967495a4d)

Four (#litres_trial_promo)

Within the Tides (#litres_trial_promo)

Five (#litres_trial_promo)

Six (#litres_trial_promo)

Seven (#litres_trial_promo)

Eight (#litres_trial_promo)

Nine (#litres_trial_promo)

Keep Reading (#litres_trial_promo)

Index (#litres_trial_promo)

Acknowledgements (#litres_trial_promo)

Copyright (#ulink_be0cf05b-25f1-5b3c-9454-60bbd566e7e6)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

Maps (#ulink_f3e6c535-09f5-59ce-a3ad-ba94caa1b50a)

South East Asia (#uab55d30e-7131-5ba4-b79d-c3c721ef4441)

East Coast of Sabah and the Sulu Archipelago (#uff470cb9-31de-51ee-a73f-54a28b649d53)

West Coast of Thailand and the Mergui Archipelago (Myanmar) (#litres_trial_promo)

Singapore, the Riau-Lingga Archipelago and the East Coast of Sumatra (#litres_trial_promo)

South East Sulawesi (#litres_trial_promo)

SARANI’S BOAT (#ulink_27f33e3b-5d5e-5b36-9d03-8fa3ecf9a16e)

One (#ulink_0385e591-6908-5267-b1bf-f83703c2ae3f)

I know of no place in the world more conducive to introspection than a cheap hotel room in Asia. I had seen inside a score or so by the time I reached the Malaysia Lodge in Armenian Street. It was May and Madras waited for the monsoon. In the hotel’s dormitory, one night during a power cut, I saw Bartholomew’s map of South East Asia for the first time. I was eighteen.

In other hotel rooms I have puzzled over why that moment made such an impression on me. My first response was overwhelmingly aesthetic; can a serious person reasonably assert that his motive for first visiting a region stemmed from how it looked on a map? Compared to the sub-continental lump of India, so solid, so singular, the form of South East Asia was far more exciting – the rump of Indochina, the bird-necked peninsula, the shards of land enclosing a shallow sea, volcanoes strung across the equator on a fugitive arc. It was the islands especially that drew me. From the massive – Sumatra and Borneo and New Guinea – to the tiniest spots of green, I pored over their features by candlelight.

Thirteen years and hundreds of cheap hotel rooms later, in the spring of 1996, I was in the Malay Archipelago for the fourth time, studying my third copy of Bartholomew’s map spread out on a lumpy bed in Semporna. Its significations had changed for me; it had become a document that recorded part of my personal history.

The real discovery I made on my first trip to Indonesia was the language. I struggled with the alien scripts and elusive tones of the mainland, and progressed no further than ‘hello, how much, thank you’. I could ask, ‘where is …?’ in Urdu or Thai, but I would not understand the answer. I had become illiterate once more. Indonesian Malay was a gift in comparison. There are no tones and it uses Roman letters which are pronounced as they are written (apart from ‘c’ = ‘ch’). That was not the end of the good news. There are no tenses. The verbs do not conjugate. The nouns do not decline. There are neither genders nor agreements. Plural nouns, where the context is ambiguous or the number indefinite, are formed by reduplication of the singular. There were signs of more complex grammar lurking in the use of a number of prefixes and suffixes, but for a beginner the rewards are almost instant. Learn the words for ‘what’ (apa), ‘to want’ (mau) and ‘to drink’ (minum), say them one after another – apa mau minum? – and wonder at the unnecessary grammar and syntax English requires to ask the same question, ‘What do you want to drink?’ In six weeks I had learned enough of the language to make me want to learn more. Approximately 250 million people speak Malay.

By the time of my third visit to Indonesia my Malay was competent. I had become very interested in the country’s tribal peoples after a journey to Siberut Island off the west coast of Sumatra. It is an island some seventy miles long and thirty-five miles wide, covered in the main by rainforest. In the company of a trader in scented wood (who spoke no English) I crossed the island from east to west on foot and by dug-out canoe, stopping at the long houses of the Mentawai clans, a tribe of animist hunter-gatherers. I was entranced by their serene self-sufficiency and their harmonious relationship with the jungle.

On this third visit, I tried to repeat the experience in Sulawesi, where I met disappointment and the Wana people, slash-and-burn farmers who are turning a national park into a patch of weeds. I travelled with the park’s sole warden, Iksan, who was as despondent as I. We were glad to leave the Morowali Reserve, returning to Kolonodale the day before ‘Idu’l-Fitri, the Muslim feast at the end of Ramadan. Despite the fact that neither of us was Muslim we were invited to take part in the celebrations, making a tour of the town with a group of men and being invited to eat in every home. By the time we came to the water village, the houses built on stilts out over the shallows, I wondered how I could eat another thing. We were offered tea and cake in a spacious house made of milled timber belonging to a Bajo family.

I had heard of the Bajo people before, a tribe of semi-nomadic boat-dwelling fishermen to be found in the eastern archipelago. Their name even appeared on the map; the principal port of western Flores is called Labuanbajo, ‘Harbour of the Bajo’. It did not surprise me to find members of the group living in a house in Kolonodale – the Indonesian government has long pursued a policy of settling its traditionally itinerant peoples – but the head of the family told me that he had been born on a boat, and that he had relatives who still pursued the Sea Gypsy way of life. To hear that there were people who practised nomadic hunting and gathering on the sea not far from where I was sitting, refusing more cake, excited an instant desire in me to find these people, to travel with them. I started planning my next visit to the islands before I had even left.

They say Sabah looks like a dog’s head – an observation that can only be made from a map or from space. Semporna was there on the lower jaw. (The rest of Borneo does not look like the rest of a dog.) My final destination, Mabul Island, was too small to feature.

I met Robert Lo, owner of the Sipadan-Mabul Resort, at the World Travel Market in London. He was there on the ‘Sabah – Borneo’s Paradise’ stand to promote his diving operation, to which he always referred as ‘SMART’. My first researches into South East Asia’s boat-dwellers had shown me that their distribution had been much more widespread than I had imagined and that Sabah was one of the places that might still have a completely maritime population. I asked him about Sea Gypsies, out of curiosity as much as anything, but he said, sure, there were lots that anchored near Mabul. ‘I let them use my island to build their boats, to have their weddings, to take their water. Their chief, Panglima Sarani, he’s a good man. I can introduce you.’ He gave me a Sabah Tourism Promotion Corporation brochure advertising the Regatta Lepa Lepa in Semporna, an event which purported to conserve and celebrate ‘one of the exotic culture’[sic], that of the Bajau Laut. My plans had found their focus.

Naturally I had doubts about how authentic such a pageant might be, and they strengthened hourly from the moment I was handed the STPC press-pack in Kota Kinabalu. I would be wearing neither the ‘one of the exotic culture’ T-shirt, nor the Regatta Lepa Lepa baseball cap. Later, on the drive from Tawau to Semporna, I had cause to disbelieve their promotional map of the state.

It was the sort of cartoon map that is handed out at the entrances to theme parks, portraying an enchanted grove brimming with attractions. There were happy climbers on Mt Kinabalu and happy tribespeople waving from their long house and happy divers at Sipadan. Even the wildlife was happy, charismatic mega-fauna peering out from amongst the florets of a forest that covered the whole state. As the minibus left Tawau, I waited for the jungle to start, but it did not; oil-palm plantations spread as far as Semporna.

The Regatta Lepa Lepa was indeed as contrived a piece of hokum as I have ever seen. Not a single Bajau Laut person took part. The lépa-lépa is their traditional houseboat, and there had been several examples on parade for the beauty contest, but none was owned or lived on by a Bajau Laut family. The winning entry had been commissioned by the STPC from a boat-builder on Bum Bum Island. There was no doubting the skill of the wright, nor the authenticity of the craft’s beautiful form, but using the decorated sail as advertising space for his business detracted somewhat from the overall effect. The other events – various boat races, tugs-of-war and catch-the-duck – left me cold.

Corporal Ujan of the Marine Police called me over to their office. I had had a couple of beers with him on my first night in town. It was good to see a familiar face amongst all the uniforms. Security had been ‘beefed up’ for the Regatta. Semporna had been visited twice by raiders from the Philippines within the last month. Ujan had important news.

‘You know the Pala’u man you were looking for?’ I had been told over dinner in Kota Kinabalu with the director of the Bajau Cultural Association, Said Hinayat, that I should not call the Bajau Laut ‘Pala’u’ as it was insulting. Sensibilities in Semporna were not so delicate. ‘That’s him. That’s Panglima Sarani over there.’ Ujan pointed to a jetty not fifty yards away. ‘He’s the old man sitting down mending his fishing net.’

There were two figures on the jetty working on the net. All the doubts and worries that had accumulated along the way on my journey to this point – questions about whether I would be accepted, could communicate, endure – all would be answered in the next few minutes. I stepped onto the decking. Neither looked up at my approach. They were both old, grizzled, and the one facing me was small and looked frail, until I was close enough to see the sinews standing out on his forearms. I thought he must be Sarani – the other had a broad back and powerful shoulders and seemed younger in his body. They were both wearing sleeveless shirts and blue baggy fisherman’s trousers that fasten at the waist like a sarong.

I spoke his name. The man with his back to me turned. He did not seem surprised to see a white man who addressed him in Malay. I squatted down beside him and looked into his weatherbeaten face, his hair stiff with salt, skin almost as dark as his eyes, his lips stained red with betel-juice. I introduced myself. I explained that I was interested in the Bajau Laut and their life at sea. Corporal Ujan and Robert Lo had both mentioned his name. He was going back to Mabul? In the morning. Could I go with him? The success of my journey depended on the answer and I hesitated to ask the question. Sarani showed no hesitation replying ‘Boleh, can.’ He returned my smile, showing his two remaining blackened teeth. We made a rendezvous at the Marine Police post for the following day. I left him to his work and returned to my cheap hotel room.

Packing is like trying to tell fortunes and I picked over my belongings like a soothsayer reading the fall of prophetic bones. I tried to cast my immediate future, to imagine its situations, its practicalities, and provide for them with objects, but I had not even seen one of their modern boats yet. Said Hinayat had told me much about the Bajau in general and he disabused me of the notion that the Bajau Laut still lived on lépa-lépa, but he could not prepare me for what lay ahead, never having spent any time aboard a Sea Gypsy boat himself.

‘Of course “Sea Gypsy” is a misnomer,’ he had said. ‘They are not a Romany people.’ I pointed out that neither were sea-horses horses, but were so called in the vernacular because they resembled a more familiar land animal. ‘But names are important. We Bajau call ourselves the Sama people. So the Bajau Laut, the Sea Bajau, are properly called Sama Mandelaut. They are the only Sama with the tradition of living on boats.’ The other Bajau, House Bajau and Land Bajau, had never been boat-dwellers, although they had arrived in Sabah by sea from their home islands in the Philippines. Their migration started in the eighteenth century, and continues to this day. The Land Bajau are rice-farmers and were among the earliest migrants. They settled inland around Kota Belud and have become known as the Cowboys of the East because of their horsemanship (so say the STPC brochures). The House Bajau live in stilt villages on the coast and islands. They are fishermen, but do not live on their boats. In recent times they have become cultivators of agar-agar seaweed. Many Bajau Laut, he said, had now settled in houses and were integrating with land-dwelling Bajau groups.

Said could not say how many Sama Mandelaut still followed their traditional way of life. The Bajau Cultural Association had other objectives. He had just come back from Zamboanga in the Philippines, scouting locations for the third biannual Conference on Bajau Affairs. There was talk of a peace deal between President Ramos and Nur Misuari of the Moro National Liberation Front, but Mindanao and the Sulu Archipelago remained dangerous places. As a politician, Said was immensely gratified by the international attention. He had met the American Clifford Sather, the leading anthropologist in the field, at the first conference in Kota Kinabalu. The second had been in Jakarta, attended by experts from Japan, Europe, Australia and America, one of whom estimated that the Sama-speaking population of the Philippines, Malaysia and Indonesia might total thirty million. ‘You know they have a Bajau Studies course at Osaka University?’ Our conversation had been punctuated by the incessant ringing of his mobile phone.

I gave up on the packing and went to meet Ujan for a beer. It was an eerie walk through the tropical darkness to the Marine Police post, the streets deserted. The fearfulness that followed the second raid was acting like a curfew. Semporna is much like any other small Malaysian town; the most impressive building is the mosque and the businesses are Chinese-owned. The gold shop targeted by the robbers was no exception. The newspapers were very careful to call them neither pirates nor Filipinos. They were ‘raiders, thought to be nationals of a neighbouring country’. Ujan had been out on patrol at the time, but he told me the story.

The raiders, ten of them, had come from the sea in three plywood speedboats. They were armed with automatic rifles and grenade launchers. They stormed the centre of town, shouting ‘We’ve come for the police!’ The police had killed two of the gang in the previous raid. They fired off a grenade at the police barracks, which failed to explode. The townsfolk did not try to stop them when they turned their attention to the gold shop. They stole £50,000 in gold and cash, and knocked over the register of the shoe shop next door for good measure. The police arrived as they were making their escape and a fire-fight ensued. Two of the robbers were shot dead and a third was captured. The rest escaped with the loot. Two civilians were wounded in the crossfire – an eleven-year-old boy and the driver of a taxi one of the dead robbers had tried to hijack. The two were being taken to hospital in Tawau, the taxi driver accompanied by his pregnant wife, when the ambulance collided with a landcruiser. It was raining hard. The boy and the pregnant wife were killed outright.

One of the robbers had nearly been caught some days later when he tried to steal a fisherman’s canoe. The fisherman was shot in the neck, and his attacker fled. Ujan doubted if they would be caught now. They would have reached the safety either of the ‘Black Areas’ of Darvel Bay (islands like Timbun Mata and Mataking), or else returned to the territorial waters of another country.

Ujan tried to reassure me about the safety of the seas around Mabul and Sipadan. They were patrolled regularly by the Marine Police and the Navy, not least because Indonesia had laid claim to Sipadan. I would be especially safe with Sarani. The Panglima was a respected man, he said, known for his magic powers. ‘It is true: no blade can eat his body, no bullet can enter.’ He too was unable to tell me what to expect. ‘You have arranged to meet him at the post? Then he will be there for sure. He does not make janji Melayu, Malay promises. He is good-hearted.’ And when the following day Sarani did not appear, Ujan’s only comment was ‘Janji Melayu.’

His colleague Corporal Mustafa did not hold out much hope. ‘The market is awake by seven o’clock and the tide was high at eight. If they were staying to buy something, they would have gone to the shop when it opened and left with the tide. They do not like to stay in Semporna because they cannot fish. I think they have gone.’ It was midday. I had been ready since half past seven, but maybe I had not been early enough. Maybe Sarani had changed his mind. Our meeting had seemed too good to be true. I went to look for him in the water market, in the confusion of peoples and languages and products supported above the shallows near the mosque on ironwood piles. I did not find him. The ebbing tide uncovered a beach whose sand was black with effluent. Plastic bags churned in the breaking wavelets. Under the noonday sun, the stench was almost unbearable. The loudspeaker of the mosque jolted into life for the call to prayers.

The television was on when I got back to the Marine Police post, and they had just seen me on it. I had been lurking at the back of the crowd in a news report on the Regatta. Now the sound had been turned down on a sunset shot of the Ka’aba at Mecca; Malay subtitles translating the Arabic prayers ran across the bottom of the screen. Officers sat around and smoked in the afternoon heat. The radio crackled with communications from a boat on patrol. A bald lieutenant arrived on a moped and was surprised to see me standing to attention with the other ranks. Mustafa explained.

‘So you want to stay with the Pala’u? Really? Can you stand it? You can eat cassava? You can stand lice?’ He scratched his shiny pate. I did not have a chance to answer. Sarani appeared in the doorway, looking about nervously. The lieutenant hailed him with mock deference, ‘O, Panglima! Your white son here thought you had gone back to the Philippines.’ Sarani came in once he saw he was amongst friends, but his grey brows remained knitted with puzzlement. He had been stopped that morning in the market by the Field Force. They had wanted to see his identity card, but all he had been able to show them were some letters from local officials. He produced them from his shirt pocket, three typewritten sheets each encapsulated in a plastic bag. He passed them to the lieutenant.

The inefficacy of the documents and the great store Sarani set by them caused the lieutenant some amusement. Sarani could not read them for himself. ‘They say you are a chief. They say you are good-hearted. They say you have been at Mabul a long time.’

‘Since the coconuts were this high.’ Sarani raised a thick hand to the level of his nose.

‘How old are you, O Panglima?’

‘I do not know.’

The lieutenant leant back in his chair. His tone changed to one of concern. ‘Panglima, they do not say you are a Malaysian national. I have told you before you should register your boats with us. Then the Navy will not stop you at sea, and in the market you can show the Field Force the document. Your white son here can paint the numbers on your boat.’

Sarani was putting away his precious letters, and he turned as though noticing me for the first time. ‘Ready?’ he said. ‘The boat is here.’ The change from harmless old man to ship’s captain was instantaneous. We walked out through the back room to the jetty and there, dwarfed by a battleship-grey patrol launch, was Sarani’s boat, wooden and weathered.

It was about thirty-five feet long, its beam six feet, the stern low in the water, the bow steep. The exhaust from the diesel marine had left a black smudge down the white gunwale. An olive-brown tarpaulin had been made into a tented awning amidships. Faces peeped round the edge. The open deck at the bow and the stern was scattered with market goods, a sack of salt, plastic jerrycans, slabs of cassava flour, a tall bunch of plantains, new sarongs. A rusted anchor with a roughly shaped stick as a crossbar sat amongst the purchases. Clothes dried on the tarp. It was not a prepossessing sight.

As I passed my bags down to a young man in jeans on the bow, Sarani stood on the bow rope to pull the boat closer, and ushered me on board, pointing to a space that had been cleared for me under the tarpaulin. The young man walked along the edge of the gunwale outside the awning and reappeared in the stern to drop down into the engine well and start to crank the motor. He wound the flywheel as fast as it would go before flipping the ignition, and the engine coughed into life, blowing sooty smoke rings from the end of the exhaust pipe. Unsilenced, it was deafening, and I couldn’t hear what Ujan and Mus were saying as I looked up at them on the jetty waving goodbye. Sarani cast off.

I was glad for the racket the engine made; it precluded conversation. I did not want to talk, only to observe, as I was being observed. I could feel the eyes of everyone under the tarpaulin were on me, the mother and her three young children, the older woman who was rolling herself a cigarette, Sarani’s white-haired companion from the day before. He touched my arm to gain my attention and mimed smoking one of my cigarettes, before settling down to the reality. I let them get on with scrutinising me and tried not to appear alarming – smiling at the children seemed only to make them cry.

Out in the channel, the sun was fierce. We passed the stilted suburbs of Semporna, single plank walkways their pavements, the open water between buildings their streets. Pump-boats putt-putted in and out of the maze, small two-stroke in-board engines making them sound like mopeds, their riders sitting at the stern with one arm hooked over the plywood side working the paddle that acted as the boat’s rudder. Their flat plywood bottoms bounced across the wake of a trawler coming into port, nets furled around the davits. Less than a mile away was the coast of Bum Bum, with villages dotted amongst the coconut plantations, clusters of rusting roofs surmounted by the shining tin dome of a mosque. The channel turned and broadened, habitation becoming more sparse, and ahead was open sea. Flying fish fled our bow wash.

As we cleared Bum Bum’s southern point, the stilt village that had appeared to be attached to land turned out to be freestanding, planted on pilings over a shallow reef, the houses connected to each other, but to nowhere else. Behind was another island, Omadal, inhabited, and a Bajau Laut anchorage. I scanned the horizon off the port bow where I thought Mabul should be, and I made out a low regular shape looking like the cap of a mushroom, the sides curving down and in on themselves, the top flat – the characteristic shape of a coconut plantation. Sarani moved over to where I sat.

‘That’s Pulau Mabul,’ he shouted, pointing to the shape. We were still travelling south-south-west along the coast, and Mabul was due south, which left me wondering about our course.

‘We are not going that way?’ I pointed straight out towards it.

‘Cannot. There’s coral, you see?’ I had not been looking properly, but now I could see a line of grey rocks that broke the water, the palisade of the Creach Reef running uninterrupted from Bum Bum to the group of three islands we were approaching. ‘Only at the top of the tide can we go that way.’ He looked round at an estuary that bit into the mainland. The river brought brown water and forest leaves out into the channel. The mudflats were uncovered between the mangroves and the water line, and as we passed, a view into the inlet opened up, its banks covered in nipa palm; behind, were hills rising to one thousand feet and the westering sun. Sarani pointed to the flats where egrets stalked. ‘The tide is still coming in. We must go around these islands to reach the deep water.’ He pulled a dirty Tupperware box from under the gunwale, his betel-chewing kit. He peeled off the husk, mottled orange and black, divided the nut and wrapped a portion with some powdered lime in a leaf. He stuffed the package into a metal cylinder which fitted over a wooden baton and mashed the nut and leaf and lime into a paste with what looked like an old chisel bit. He pushed the cylinder down and the baton, acting as a plunger, presented a plug of pan to Sarani’s reddened lips. He packed away the paraphernalia, and went back to scanning the sea, spitting pensively over the side. It is a complicated business, using a masticatory when you haven’t got any teeth.

Manampilik, the last of the three islands, was little more than a steep ridge with a rocky shore. Coconut palms clung to the lower slopes, the higher left to scrub. The sea was glassy in its shelter. There was a swirl at the surface. ‘Turtle,’ said Sarani, and as I looked for it to show again, a fish as thin as an eel, a long-tom, broke from the water ahead of the bow and skipped like a stone once, twice, three, four times, each leap carrying it ten feet. The run ended only after another ten feet of tail-walking. I had never seen anything like it. Sarani laughed at my surprise and said, ‘They taste good.’

We rounded the southern edge of the Creach Reef and passed in deep water between Manampilik and a fourth island, confusingly called Pulau Tiga, ‘Third Island’, a tiny islet, no more than a sand bar, yet covered with stilt houses. It seemed the most unlikely place to site a village, on a strip of sand that looked as though it would wash away in a big sea, with nowhere to grow anything, no fresh water. Was there even any land left at high tide?

‘Oh yes, there is still land,’ said Sarani, ‘you see, they have trees.’ And there were two forlorn papaya plants, whose sparse crown of leaves on a long stem poked up between the roofs, growing in the middle of the village. There was a volleyball net strung between them. It was a surreal touch on a surreal island, a sand bank in the middle of nowhere that quadrupled in size twice a day. Sarani had family connections here. One of his sons had married a girl from the Bajau Laut group whose boats I could see anchored on the southern side of the island. It was my first glimpse of a Bajau Laut community, and it thrilled me.

We turned east-south-east, away from the mainland, and the horizon became immense. The water was indigo, marbled with wind lanes, and moved with a slow rhythm from the south, from the vastness of the Celebes Sea. I could see the tops of the trees on Sipadan to the south-east, the ragged outline of its tiny patch of rain forest, and due east, the peak of Si Amil. Danawan, separated from Si Amil by a narrow strait, and Ligitan, the last island in the group, remained hidden below the horizon. Sailing east from Ligitan there is nothing but water for the next five hundred miles.

We slowed as we approached Mabul’s fringing reef and picked our way through the coral heads, Sarani sitting in the bow on the look-out for snags. The evening sun threw a warm light over the stilt village on the southern shore and long shadows in the grove of palms behind. The shouts of children playing came out across the water. Pump-boats and brightly painted jongkong were returning with the day’s catch, being dragged up the beach between the houses. We made for a long barrack-like building – the school – and nearby a fence ran back into the palms, marking the end of the village, and the beginning of the Sipadan-Mabul Resort. The stilt houses connected to the beach by duck boards were replaced by sun-chairs and thatched umbrellas. The resort’s liveried jongkong and speedboats, all bearing the ‘SMART’ logo of a turtle kitted out in scuba gear, were pulled up on the raked sand. Set back amongst the palms were bungalows with verandas and air-conditioning units. It was a different country.

Sarani expected me to get off here and stay in the resort. He had not completely understood what I wanted to do, and now that I was on the boat I certainly did not want to get off it. ‘You cannot stay on the boat tonight,’ he was adamant, ‘but we will come back for you in the morning. Maybe you can stay in the village.’ We motored around to the other side of the island where the houses were poorer, more ramshackle, and dwarfed by an orderly group of wooden buildings at the end of a long jetty – another resort, the Sipadan Water Village. We nosed back in over the reef, and towards a house whose seaward wall had a doorway where sat an old man with a grizzled crew cut, shirtless, watching our progress. Sarani hailed him, as we cut our engine and glided in, the bow poking into the woven palm-leaf wall. It was agreed. My bags were passed into the house, and Sarani signalled for me to follow them. I clambered in.

‘Until tomorrow?’ I said.

‘Until tomorrow, early.’ I watched him pole the boat around and out towards the deeper water, the sun setting behind the hills on the mainland. I was not completely sure if I would see him again. Meanwhile, for the second time that day, I found myself landed in a strange world where I was the strangest thing in it, feared by the children and stared at by the adults, talked about in a language I did not understand. I sat with my luggage on the other side of the seaward door from the old man. His family hemmed us in, their curious faces catching the last of the light from the western sky. Shadows grew from the back of the hut’s single room. Fishing lines, nets, clothes hung from the palm-thatch walls, baskets from the rafters. Woven pandanus mats and pillows lined one side. I looked around while they looked at me. I looked out at the strands of painted clouds above the silhouette of the mainland, the sea turning grey in the twilight, lights coming on in the resort. Noises of the village relaxing in the dusk, the smoke of cooking fires came from the landward. Wavelets broke on the beach. A breeze rustled in the thatch eaves and set the palm trees soughing. ‘It’s very beautiful,’ I said to the old man in Malay.

‘Jayari cannot speak Malay,’ said Padili, his youngest son, ‘but he can speak English.’ I repeated myself and Jayari followed my gesture at the horizon with his eyes, still uncomprehending. He saw only what he had seen every day of his life, the sea that supported him and his family, the sea that kept them poor. And not a hundred yards away was the Sipadan Water Village, a faux primitif mimicry of the stilt village where he sat, mocking his poverty with its milled boards and varnish, charging per person per night more than his family’s income for a month. The white man thought this view beautiful? I felt ashamed, and added by way of explanation, ‘We do not have this in my country.’

‘Therefore,’ said Jayari, ‘from what country are you coming?’ I was as much surprised by his tone as by a conjunction straight off the bat. He spoke loudly and was so emphatic in his use of English as to be almost threatening. ‘Therefore’ turned out to be his favourite word and he was pinning me down with questions. He held an interrogative grimace after each, and the slight tremble that moved his old body made him look as though he would explode with rage. His mild ‘Ah, yes,’ once I had given an answer, and the occasional grin that betrayed no hint of a tooth, showed his true character. I told him I wanted to stay with Sarani, and he asked: ‘Therefore, what is your purpose in this roaming around on the sea?’

He assumed I would spend the night at the resort, and even started telling Padili to help me with my bags. He was surprised when I stopped him. ‘But you are rich, and there are many people from your country there.’ I told him I had not come so far to meet people from my own country. ‘Therefore, where will you sleep this night? In which village? Please, do not go to the other side. There are many Suluk people there. Therefore, you will sleep here.’ Padili was sent out for Coca-Cola and an oil lamp was lit. Jayari told me that they, and most of the other people on this side of the island, had left the Philippines three years previously to escape Suluk violence. ‘We want to keep our lives, therefore we came here. They attack us with guns. Please do not trust Suluk people. We cannot do these things. We are good Muslims. If we commit bad things, therefore bad things happen to us. How can they commit such things to human beings? Please do not trust Suluk people.’ His head shook as he stared at me, the corners of his eyes clogged with rheum. The households on his side of the island were mostly Bajau. The village on the other side had been there ten years and was a mixture of Suluk and Bajau, with the balance of power tilted towards the Suluk. Robert Lo’s resort took up the whole of the eastern third. Almost everyone on the island, resort-workers included, was an illegal immigrant.

Food was brought, rice and fried fish, and a jug of well-water. I had been wondering what I would do about drinking water and here was the answer. Jayari said he had learnt English from an American teacher at the Notre Dame school in Bongao during the pre-war days of the Philippine Commonwealth. He remembered Mister Henry with fondness, and his home island that he would not see again. ‘Of course we want to go back, but we want to live, therefore we stay here. Please do not trust Suluk people.’

The sleeping mats were being spread for the night. Beside me, with a mat to itself, was a shallow tray, wooden and filled with what looked like ash. Jayari explained they were the ‘remains’ of his grandfathers, carried with him out of Bongao. Every Bajau house had such a place; the seat of Mbo’. I was intrigued by the duality of their belief, Islam and ancestor worship running side by side, but having declared himself a good Muslim Jayari did not want to talk about it.

He was much more interested in the possibility that I was in possession of cough medicine. His cough kept him awake at night. It made his legs weak and he could not go very far before he became breathless and dizzy. He could only smoke one packet of cigarettes a day, and that was upsetting him. ‘Therefore you will give me medicine.’ He had smoked at least five cigarettes while we were talking, flicking the ash through the gaps between the floorboards. I had tried one. They were menthol, but the mint did little to conceal just how strong and rough the tobacco was. The brand was called ‘Fate’, the packet green with a white rectangle front and back on which was written FATE in black letters below a single black feather. I asked how many he usually smoked. ‘Two packets,’ he said, at which his wife laughed and said, ‘Three.’ She had settled on a pillow by Jayari’s leg, but had given no previous sign of understanding our English conversation. ‘They are very strong,’ I said. ‘Can you smoke another brand?’ The younger men smoked Champion menthols, milder, made in Hong Kong and smuggled from the Philippines. ‘I cannot smoke another one, another one makes me cough. I cannot be happy. Therefore, if you pity me, you will give me medicine.’ I only had the remains of the strip of Disprin I had bought for a hangover in Singapore. He looked at them suspiciously, but squirrelled them away in the wooden box where he kept his smokes.

I had not moved from the spot where I first sat down. I needed to stretch my legs. Jayari sent Padili with me to the shore. Night had fallen. The moon had yet to rise. It was probably not the best moment to negotiate the walkway to the beach for the first time. The crossing involved a nice balancing act on rough planks that merely rested on wonky pilings and bent considerably under my weight. What looked deceptively like handrails in the darkness were in fact wobbly racks for hanging nets and clothes and fish. And now that I was halfway, someone was coming in the other direction. We shimmied past each other somehow. It was with relief that I reached the land, although I scuffed my foot against a lump in the sand, and nearly stumbled.

After a day of being scrutinised and interrogated I wanted to be on my own, and walked off down the beach beyond the last stilt hut. I found a log on which to sit and listen to the palms, stargazing and wondering, therefore, what was my purpose in this roaming around on the sea? Sarani would be here in the morning. He would take me fishing as my father had done when I was a boy, and I had a sudden access to memories of summer holidays in the west of Ireland, a time before the disappointments of growing up, the smells of hay and camomile and burning turf, fishing for mackerel with handlines.

Fishing had been an important part of my father’s Devon childhood, and he had passed his father’s love of it on to me. I caught my first fish aged three. Some of my most worry-free hours have been spent on the river bank. Fishing is a stoic teacher and maybe that was why I had sought out a people who fish as a way of life, to learn what it had taught them.

Two (#ulink_75b6cb85-4f3a-5996-acf6-cfcb877ea9e8)

It was still dark when Sarani called. I came awake instantly. ‘Come,’ he said. I started scrabbling around with my luggage. ‘No, come, look.’

Two boats were moored outside the seaward door, Sarani’s and another, from which a crowd of faces watched me as I climbed down onto its bow. The ceremony began.

A young woman stepped forward, a bright print sarong tied off under her armpits, her shoulders bare. She had the listless air of one who has just woken. She squatted on top of a wooden rice mortar, and an old man wearing a strip of blue cloth around his head and thick spectacles held on with string poured water over her from a coconut shell. He mumbled words that were not meant to be heard. An old woman smoothed down the girl’s long black hair with her hands, the strokes progressing none too gently down to her shoulders, sweeping down each arm, muttering all the while. A young man came forward and was treated to a more perfunctory bath. They each put on dry sarongs and settled down to eat with the others from a large bowl containing a mound of cassava decorated with plantains. Their engine chugged into life, they pushed off from Sarani’s boat, and they were gone, the eastern sky lit as though by orange footlights.

‘They are going to pull up their nets,’ said Sarani in answer to my question, but he was more elusive about what the ceremony meant. For him it did not have a meaning; for him, everything about the ceremony, its form, its purpose, was self-evident. ‘It is Mbo’.’

The sun was already fierce as Sarani poled the boat out to the edge of Mabul’s reef. The tide had started to go out, and we had to get to Kapalai while there was still enough water for us to cross over its fringing reef. It used to be an island, Sarani said, smaller than Mabul and waterless, covered in scrub, but then the house-dwellers of Pulau Tiga cleared it, as they had Mabul some years before that, to plant coconut palms. It washed away quickly, the palm roots unable to hold the sandy soil against the lapping of the sea at high tide, let alone against a storm. All that was left of the island was a sand bar, covered at high tide, but even from Mabul you could see the straight black line of the new jetty that was being built over the reef. As we drew closer it became apparent just how big the structure was, three hundred feet of walkway high off the water, made of top quality milled timber. Obviously it had nothing to do with the Bajau, and Sarani confirmed that one of the resorts was building it, but why they needed such a major platform at Kapalai he did not know.

The sand bar was showing and we steered for the other side from the jetty where a small fleet of boats grew from specks on the horizon. I could count twelve as we skirted the edge of the reef to find a passage through the coral heads. The boats lay in a skein parallel to each other, bows pointing into the wind, and as we came up past them from the stern I caught glimpses of the life of the afterdeck. We throttled back as we passed the lead boat, dropped the anchor, killed the engine and became part of the floating community. It felt unnerving no longer to have a destination. My journeying was at an end and I had arrived in the middle of other people’s lives. I turned away from the lure of the horizon, from the point of the bow that seemed still to forge ahead as it rose and fell on the light waves. I surveyed the flotilla ranged about us like cygnets behind their parent and above the soft noises of the empty sea came the sounds people make when they are at home. We had stopped, we had arrived, but we had not really gone anywhere. We were still on the boat, but the act of stopping, of taking our place in the group, had changed its nature. For the first time, powerfully, I saw Sarani’s boat as more than a vehicle; it was a vessel and I ducked down into the shade of the awning, into the life it contained.

‘This is Arjan,’ said Sarani, and the naked boy, hearing his name, shrank further behind his father’s shoulder. He had a cheap string of shells from the market around his neck and a snotty nose. He must have been two years old. ‘And that is Sumping Lasa.’ The little girl in a dirty patterned green dress, three maybe, with straggling hair, scratching her head. She looked at me suspiciously from a safe distance, her mouth slightly open. Minehanga, Sarani’s young wife, sat nursing their youngest child, a daughter called Mangsi Raya. She had large, strong features and a sharp voice that would carry far across the water. Her jet black hair was twisted into a knot high on her head. She put the kettle on to boil over a kerosene burner, still in its cardboard box, whose lid flaps she used as a windbreak. Mangsi Raya held on to the teat with both hands as her mother bent forward. She had thin light brown curls and a pale skin that had yet to be burned by the sun. She had been born on this boat, on these loose boards, under this tarpaulin.

We were hailed from the boat directly astern and Sarani slackened off the bow rope until our stern was alongside its prow. It belonged to Pilar, Sarani’s youngest son by his first wife. Pilar had a dug-out to return, and his wife, Bartadia, had our breakfast in a basin, strips of plantain, battered and fried. She wore a sarong piled on her head and a face mask of green paste to protect her skin from the sun. She was pretty nonetheless, and her eye-teeth, like Pilar’s, were capped with gold. Their eighteen-month-old son, Bingin, burst into tears the moment he saw me and hid his face in the folds of his mother’s track-suit top. Mother and son stayed up on the bow while Pilar climbed down nimbly, tied off the dug-out’s painter and threw Arjan, his half-brother, who was already clamouring for the food, high into the air. He went up screaming and came down laughing, reaching for the basin as it passed over his head. He plonked himself down on the deck hard by the rim and tucked in with both hands. He burnt his fingers.

Sarani answered their questions about me as we sat on the stern eating – of the other adults only Pilar spoke any Malay – referring to me occasionally for confirmation. ‘You do come from Italy, don’t you?’ Arjan spoke a language all his own as he waved his food around, and threw some over the side, but he understood when Sarani sent him off for his Tupperware betel box, running up to the bow and rattling the loose planking. Sarani prepared a plug and climbed down into the dug-out to sort out the net that lay in its bottom. Minehanga put the rest of the plantain into another bowl and passed it down to him. He wedged it into the bow with his betel box, spat red juice and said, ‘You want to come fishing?’

I had been in dug-outs before, though not on the sea. They are tricky craft at the best of times, and the best of times are when you are safely in and sitting down, with your weight low and a paddle in your hands. The getting in and the getting out are the interesting bits, and getting into this dug-out had the potential to be very interesting indeed. I had not fallen out of one before, but there is always a first time. My audience, which had grown from the occupants of our two boats to include everyone on the sterns of the other boats nearby, waited expectantly. This dug-out was old and leaky, but it looked big enough and broad enough in the beam to take us both. Its sides had weathered to the point where the soft wood in the grain was rotting away, leaving the surface corrugated. Cracks were caulked with coconut fibre, strips of flip-flop rubber and plastic bags. There was seaweed growing on the inside, a fine green algae, watered by a tidal pool that never drained completely. A baby crab the colour of coral sand tried to hide under the net. Sarani was perched nonchalantly above the bow, squatting on his heels, one foot up on either side of the dug-out. I doubted my embarkation would show as much poise. Sarani turned the canoe so that I could step down into the middle from where I sat on the stern of the boat. I kept my balance long enough to sit down in the puddle, which brought a laugh. Sarani told me to move down over the net, to the plank seat in the stern. I was not too proud to crawl.

He had some social calls to make. We toured the busy afterdecks of our neighbours’ boats. At one we handed over the plantains and received a baler in return, a cut-off plastic motor-oil bottle that I was given to use. At another we filled our bowl with cassava damper. At all the curious were told I was from Italy. We turned away from the fleet and poled our way slowly over the sandy shallows, still under a fathom of water, towards the reef. The wind dropped away as though before a storm and ahead lay calm water and the three hottest hours of the day.

A silence enveloped us, complete apart from the pole dipping into water, trailing a bright arc over the surface, dipping again. As I looked over the side of the dug-out, through the green-tinted, vitreous translucence, a shoal of anchovies turned in unison away from Sarani’s pole, invisible until the moment the sun caught their silver sides and they broke from the water in a sudden effervescence. ‘Ikan bilis,’ said Sarani, ‘delicious, dried then fried.’ A small ray flew away over the sand between the coral heads, and he started up with a hunter’s reactions, though he had no spear. He stood on the bow and watched for where it would settle, but it did not stop within sight. He scanned the shallows for a long time. I had noticed how his bearing changed the moment he stepped off the land, where he seemed at a loss, walking with bent legs and wearing a half-puzzled, half-fearful expression. Now we were in his element, on the sea, where his actions had the grace of instinct. Standing in the bow, his feet seemed to rest on the horizon itself.

‘We will go over there, sana, and put down the net,’ and we resumed our lugubrious progress. The tranquillity seeped into my body, the heat, the rhythm of the pole moving us forward in spurts, each thrust like a slow pulse, the water in the dug-out washing back and forth, rushing towards Sarani as he pushed on the pole and the bow dipped, flowing back between strokes. I timed my baling to coincide with the flood at my feet. The crab went over the side. I felt like a young boy given a simple task vital to the enterprise, given a stake in it.

Sarani talked. ‘That’s Si Amil. You can’t see Danawan, but it’s only as far away from Si Amil as we are from the boat now. When we came from Bongao we stayed at Danawan for a time. We were three boats, three motor. We had not used lépa-lépa for a long time already, although I was born on one and I have built more than ten in my life. Pilar was still small, but his older brother Sabung Lani was already married and had his own boat. There were many Bajau Laut there already, and many House Bajau in the village. There used to be many fish too, but then people started using fish-bombs.’ (The phrase main bom, ‘playing bombs’, like main futbol or main badminton.) ‘Suluk people. Bajau Laut people only use nets and spears. We are frightened to use bombs. They’re dangerous and illegal. Now there are no big fish left at Danawan. We were the first to come to Mabul, and then other boats, and then the people in the village and now kurang ikan, few fish’ (kurang can also mean ‘not enough’). ‘We will put the net down here.’

Sarani found the end of the net, a monofilament gill net about four feet deep, and snagged it on a coral head using his pole. Propelling the boat with one hand, he teased out the mesh with the other. ‘It’s going to rain,’ he said, and pointed with the pole to the dark clouds rolling off the hills of the distant mainland.

‘My first wife was still alive when we came to Danawan. We already had seven children, well, eight, but one died in the Philippines when still a child. Take the net off that snag, can you? She is buried in Labuan Haji, on Bum Bum. She had family there. When Pilar got married I could have stayed with him, but a young couple should have their own boat. So I built another boat and got married myself. Why not? I was still strong, for pulling up nets, for playing love, main cinta.’ I watched the muscles working across his shoulders, baked dark chocolate, his sturdy body and powerful limbs. He was still strong, his fingers thick and worn, his feet broad, their soles bleached by salt water. ‘It is unusual for someone already old to marry a young woman, but I knew Minehanga’s father and he said yes, though only if she said yes. I paid a higher bride price, about sixteen hundred ringgit (£400), some cash, some in goods – rice, salt, cloth, tobacco. What is the bride price in your country? You don’t have one?’ and when I explained the old custom of the dowry he let out a long ‘oi’ in surprise. ‘Good, if you’re a boy. This boy getting married tonight, his family have paid one thousand ringgit, twelve hundred maybe, to the father of the bride. Here, it’s good to have daughters.’ He paid out the last of the net. A lump of polystyrene went over the side to act as a marker. We drifted away from it as Sarani prepared another plug of betel. We turned and backtracked slowly along the length of the net some ten yards away from its line of floats and Sarani rattled the pole underneath the coral heads to frighten fish towards it. Shapes of fish shot away from the stick, and sometimes their flight was stopped abruptly by a wall of monofilament. We turned again at the anchored end, turned towards the mainland. The clouds were over the sea and the patterns of the rain showed on its surface. ‘It’s going to rain, soon,’ said Sarani as he put on a pair of goggles, made of wooden frames and window glass, and slipped over the side.

He started to swim back along the net, his face under water, pulling the dug-out behind him. He ducked down, the white soles of his feet kicking at the surface. His head came up, as smooth as an otter. He clutched a fish in his hands which he threw into the boat, followed by another. A pair of goatfish flipped around at my feet. They raised and lowered spiny dorsal fins. The large scales of their flanks were nacreous below a black lateral line, a black dot near the tail, and above were shaded yellow. I watched them dying and remembered the colours of mackerel fresh-caught, the moment of regret, and as the goatfish weakened, a colour the shade of pomegranates seeped over them as though their scales were blotting paper. The sky ahead was purple now, but we were still in sunshine, lighting the turquoise shallows, turning the emerging sands of Kapalai into a bar of pale gold. The colours were so intense, the crimson fish against wet wood, Sarani’s brown back in the turquoise water. A wrasse landed in the boat, bright blue spots, ringed with black, on a chocolate brown field, a triggerfish, back half yellow, front half black, that seemed to talk, toktoktok tok. More blushing goatfish, as the first two faded to grey, even the black markings only just visible, as though their normal coloration had been sustained only by an act of will. A polka-dot grouper and a parrotfish, lime green with purple trim. ‘Kurang ikan,’ said Sarani and he climbed back into the boat. We pulled up the net in the rain.

The wind had brought us the sound of it, white noise hissing across the sea. The light became livid, the colours dead. Kapalai disappeared, drenched behind a curtain of rain which we watched sweep on towards us across the shallows, seemingly solid. In its midst the wind was chill and the noise ended conversation. Water ran from my head in streams. The surface of the sea seemed to pop with pearls, the drops rebounding. And then it had passed and we could not see Sipadan any more. Sarani unsnagged the end of the net and began to propel us towards a deeper part of the reef; the hull of the canoe was beginning to catch on the larger coral heads.

‘There are lots of fish at Sipadan, big fish, turtles, but we do not go there any more. It is not allowed, not since the resorts came. No one can fish there. We cannot go close. Do the tourists take the fish when they are diving? They are also not allowed? Hmm. They only look? Why? You do not have these things in your country? What is it like then?’ and I told him about cold, coral-less seas, rocky coasts and kelp forests, islands that have no palm trees and see snow in the winter. ‘Ice from the clouds? And the girls must pay for the boys? What a strange place.’ Sarani paid out the net again.

As soon as the storm had passed I could see a small flotilla of pump-boats streaming across the open sea from the direction of Bum Bum. They grouped at the far edge of the reef, six of them, two figures in each boat, and spread themselves out around the drop-off. I thought nothing more of them, fishermen. The net was down and Sarani was back in the water looking for shellfish. Cone shells – dolen – came over the side, lambis shells, kahanga, that look like one half of a Venus fly-trap, a pink-slitted hollow with five delicate tusks curving out from its lip. They landed higgledy-piggledy, but after a while the pile began to move as the molluscs tried to right themselves. A long, red-brown claw emerged from the slit, and a pale olive mantle flecked with white unfurled over the smooth inner surfaces. Horns poked out. The claw slipped round the edge of the shell and hooked powerfully, looking for a purchase. Those that were the right way up were dragging themselves along the bottom of the boat, mingling with the dying fish. Sarani collected sea-urchins too, téhé-téhé, not the vicious black ones with eight-inch spines whose tips break off in a wound, but ones no more prickly than a hedgehog, with feelers between the short spines that attached themselves to the palm of my hand. The bottom of the dug-out was beginning to look like an aquarium. Sarani found a large clam and set about opening it on the spot. He smashed an opening with the blunt edge of his parang, cut the muscle holding the halves of the shell closed, and quartered the contents. ‘Kima,’ he said. ‘It’s delicious, if you have some lemon juice, some chilli, some vinegar, some garlic, some Aji No Moto.’ (Sarani used the local brand name for monosodium glutamate.) It was better without, tougher than an oyster, and as salt as the sea.

When I first heard the noise I thought it was thunder, but the sound was too percussive, too short. The sun had come out again and the clouds were white and broken. ‘Main bom,’ Sarani explained, pointing to a pump-boat far behind us. The boat closest to us had its engine going, cruising over the seaward drop-off where, in theory, the big fish lay. It would slow at intervals so that the man in the front could put his head over the side. He signalled them on until they were far in front of us. Against the glare of the sea I saw a figure stand and pitch a speck out in a lazy arc over the water. The figure sat down. A beat, and then the water near the boat shivered and rose in a spout twenty feet high. The boom came last. ‘You see? Playing bombs.’ Sarani could not tell me exactly what a fish-bomb was, but he knew the effects of one well enough. ‘All the fish die, the young fish, the small fish that the big fish eat, all the coral, all the animals that the small fish eat, dead. You see? Kurang ikan. We are hungry. Before, this canoe would have been half full already. We cannot stop them. If we fight them, they come to our boats and throw bombs inside. I have seen this happen in the Philippines. Kami rugi, we are the losers.’ He pounded a betel nut with feeling.

Four of the goatfish were prepared for cooking, Minehanga cutting them roughly into lumps with a parang, while Sarani deftly gutted the rest of the catch, splitting the head and cutting in by the backbone, opening the fish out like a butterfly’s wings. These went into a bowl to salt before being laid out on the deck to dry. Minehanga had boiled the fish. There was no lemon juice, no garlic, no vinegar, no chilli, no Aji No Moto, not even any salt in the water, just plain boiled fish. It was served with more cassava damper, made from a tuber that is almost pure starch and produces a flour that turns into a glutinous pancake when baked in a dry wok. The cassava was hard work and I wondered how Sarani managed to get through it with only gums. The fish was boiled to smithereens. Sarani at least had no trouble with that; nor did Mangsi Raya, but then she already had double his tooth count. The bones went over the side. The bowls and our hands were washed in the sea. The rim of my glass of tea tasted of salt. Sarani stretched out under the awning, chewing betel, resting on a pillow. In the heat of the afternoon only the children were active. Even the fish-bomb detonations became infrequent. We were afloat again and the boat stirred with the water, its motion acting on me as quickly as a drug. Planks of wood had never been so comfortable. I fell asleep thinking about the pillow … and lice …

I was more wakeful after the wedding. We had returned to Mabul in the evening to join in the celebration of the village nuptial. The music continued under the palms long after we had returned to the boat, past the setting of the moon, and complemented the rhythms as it rode at anchor with its bow to the wind. The waves clunked under the hull. The boards creaked as the bow rose. The loose glass mantle of the oil-lamp clinked. It was soothing, until the elements of the polyphony began to change. The creak lengthened and multiplied. I could no longer hear the oil-lamp clinking over the noise of the flapping tarpaulin. Pots rattled. A glass tankard toppled over and rolled back and forth, the handle stopping it after a half-turn either way. The wind was cold and it had come around.

No one else was awake. Mangsi, cradled in a sarong hanging from the roof-tree, was still as a plumb line. The others seemed to be attached to the deck with Velcro. The wind promised rain. Sarani stirred in response and came forward nimbly on his hands and knees. He knelt in the bow, braced against the gunwale, and began to pole the bow round into the wind. Unbidden, I seemed to know what to do. I stumbled forward to the anchor rope and began to pull. I knew when to stop so that Sarani could go aft to cast off the stern line. I pulled us up to the anchor as he came forward again, and then hauled it onto the gunwale while Sarani, standing now, punted the boat out to deeper water. He nodded and I let it go. He stowed the pole, and took the rope, setting the anchor and tying off the line over the projecting bow and an iron spike driven into the stem. The sky was dark with clouds. The first drops of rain felt sharp and cold on my back. We turned our attention to the waterproof sheet that rolled down to close off the forward opening, tying the corners to lumps of coral that doubled as net weights. It was raining hard by the time we slipped round the sides of the sheet and under cover of the tarpaulin. The rest of the family were still asleep.

The two of us sat in silence, drenched, and watched for leaks in our shelter. The wind flapped under the sides of the tarpaulin and blew in gouts of rain. Sarani tied them down. We moved all the soft furnishings away from their usual stowage along the gunwales, bundles of clothes, pillows, a plastic shopping basket full of knick-knacks and hair oil. Minehanga woke up and moved the children, though they stayed fast asleep. Sarani dried himself off with a sarong which he then wrapped around himself. He reached for his betel box. We waited grimly for the storm to pass. ‘I’m going to build a roof,’ he said.

The rain died away, though the wind remained strong. As I lay down on the damp boards I could hear the wedding organ start up again. I had to admire their stamina. Sarani spat out the betel dregs and moved aft to the bilge pump, a contraption of grey plastic waste piping that projected above the deck with a ram made from shaped flip-flop rubber attached to a stick. He set up a steady counterpoint to the music until the bilge sucked dry and he settled down to sleep again. We had gone through the whole procedure almost without comment. We had worked together for the boat, satisfied its demands with promptness; a dragging anchor is not a piece of guttering blown down in the night that can be left until the weekend. What did the people ashore know of a rough night at sea? The wind in the palms, the thatch rustling, a child moving closer for warmth. The newlyweds, asleep now maybe, would know as soon as a baby came what it is to tend a boat through the night. Sarani, who had been born on a lépa-lépa and had spent no more than a handful of nights ashore in his long life, took rest when he could in a home that needed pumping out four times a day, propping up on a falling tide, battening against weather.

The kettle was on, and Minehanga was breastfeeding. Sumping Lasa had taken over the sarong cradle and was using it as a swing. Arjan was running around on the afterdeck looking for things to throw overboard. Life did not stop because we were underway and by the time we reached Kapalai Minehanga had dealt with a tantrum from Sumping Lasa who had been pushed out of the swing by Arjan, a puddle on the planks courtesy of Mangsi Raya, and the attentions of the hungry boy as she peeled plantains for breakfast. Sarani stood in the stern, one foot on the tiller, scanning the lightening horizon.

We arrived at Kapalai as other Bajau boats were returning from pulling up their nets, Pilar’s amongst them. He anchored close in behind us and began to sort out the pile of net on the bow, paying it out again, to wash it in the shallow water. While Minehanga made up a batter for the plantain Pilar transferred his catch of blue-spotted ray into the dug-out behind our boat, some still lashing the air with barbed tails, and set about gutting them. The tails went first and were flicked over the side of the canoe. I made a mental note to watch where I walked at low tide. The eyes and gills were removed like an apple core. The ray were hung out to dry on a pole. Pilar broke off to eat breakfast with the rest of us.

The sun was already hot and its strength was redoubled by the glare from the water. I retreated to the shade of the awning, only too aware after a night on the boards of the sunburn I had suffered the previous day. I could not go fishing. I watched from the boat as Sarani poled away in the dug-out over the bright shallows until his figure, standing in the bow of the canoe, became a silhouette at the edge of the reef against the empty eastern horizon.

The fleet had reassembled around us and in this social hour of the morning canoes plied between the boats, paying calls, returning a borrowed bowl, bringing food, others heading for the fishing grounds on the falling tide, collecting a pole or a paddle or a parang. We had our fair share of curious visitors. I listened without understanding to the lilting cadences of the language that seemed at odds with Minehanga’s sharp voice, listening for something that sounded familiar. I wondered how the two of us would get on without a common language. She spoke no Malay; I would have to learn Sama. This was my first time alone with her and I had no idea what she thought about my presence in her home. As helpless as one of her children and with a smaller Sama vocabulary than even Arjan, I had invaded her nest like an outsized cuckoo chick, an uninvited mouth to feed. She talked loudly and slowly at me, showing her buck teeth, and I felt like a Spanish waiter being mauled by a British tourist. I struggled to pick out something that I understood. Melikan was a word that had come up again and again in her conversations with the visitors. Now she was saying it and pointing at me. Half of it sounded familiar; ikan is the Malay word for ‘fish’. Was I expected to go fishing as well? It began to dawn on me that Melikan referred to what I was rather than what I was supposed to do, that it was a corruption of ‘American’ and meant ‘Westerner’ in general. And so I was named. She would say ‘Melikan,’ and point to a sarong near where I sat and I would pass it, or ‘Melikan,’ miming striking a match and I would proffer my lighter. We rubbed along.

Sumping Lasa was still scared of me. I only had to look at her and smile to send her running to her mother’s side. Mangsi Raya cried the moment she was more than a yard away from Minehanga. Arjan was more bold. He would run up to me, shout and run away chuckling, making the boards jump in his wake. Minehanga told him to stop, but he did not and on his next sortie he bumped into Sumping Lasa. She landed hard on her backside and started to cry. Arjan got a cuff round the ear and joined in. After the first few gusts of tears Sumping Lasa got up and went over to Minehanga for attention. She stood next to her mother, her hands cupped behind her ears, her mouth open wide and silent as her convulsed face began to redden. The silence was agonising, her face a mask of pure grief. It went on. Her mouth opened wider. And then the full force of the tantrum struck. She let out an awesome bellow, almost as long as the silence, followed by another and another. She had her mother’s voice. When it became obvious that Minehanga was not interested, she started hitting Mangsi Raya, who was startled by the surprise attack and began to cry as well. Whereupon Sumping Lasa got a clip round the head and doubled her efforts. Mangsi Raya stopped crying the moment the nipple touched her lips. Arjan knew he had won and dried his eyes. He started running up and down the boat again, his upper lip glistening with snot, taking care to avoid Sumping Lasa as she drifted around in a blur of tears, slapping my foot each time he passed. Sumping Lasa started drumming on the boards with both feet, running on the spot until she fell over. In the midst of the mayhem I caught Minehanga’s eye and we smiled.

‘Kurang ikan,’ was all Sarani had to say about his fishing, ‘but today there is no one playing bombs. Maybe they thought the wind would be strong, like last night. You were scared, no?’ He laughed at the memory. ‘It is not the season for strong wind. In this season, the wind comes from there’ – he pointed north – ‘and in the other season it comes from there’ – the south – ‘and that is when there are strong winds. Normally in this season we stay on the other side of Mabul and on this side of Kapalai.’ I was keen to find out their range, to find out just what sort of a ride I could expect. ‘We fish here and at Mabul. Then there is one reef past Mabul, Padalai, just a reef, no island. We go there sometimes. There is one more reef towards Danawan, called Puasan. The Bajau Laut from Danawan also fish there. After that? The season of the south wind comes in two months more [dua bulan, literally ‘two moons’]. We stay here for a time after that, maybe one moon, and then we go to the islands near Sandakan to catch shark. When the season changes we come back here.’ It seemed extraordinary to me that Sarani could tell me exactly how his year was spent, exactly when the south wind would come, and yet not be able to say how old he was. I asked him how old Arjan was, thinking he would be able to remember how many times he had been to Sandakan since his birth, but he did not know that either. It was almost as though there was some taboo surrounding age that prevented him from saying if he knew, or maybe from even reckoning age at all. I could not understand it. Living so close to the Equator and its perpetual equinox means that the length of days and nights does not vary much year round. The words ‘summer’ and ‘winter’ do not have a useful meaning. But the Bajau Laut live in a world full of other time signals, just as regular, just as significant. There are two tides a day, a full moon every twenty-eighth night, and a change in the prevailing wind every six months. These events are so central to the pattern of their life that it seemed inconceivable to me they would not tally them.

But then why bother counting? When the tide falls you prop up the boat. When the moon is full you go fishing at night. When the wind changes you move your anchorage. You do not have to plan beyond the next tide and the next visit to the well; there is no need to lay in store for winter, as there is no winter. There is no need to know how old you are. When you are big enough you learn to swim and paddle a canoe. When you are strong enough you help with the fishing and the housework. When you reach puberty you work and wear clothes. When the bride price has been raised you are married. While your strength lasts you are parent and provider. When your strength fails you do what you can to help. These are the only markers of time that make any sense, the events of a personal history, and there is no need to count them as they happen only once. I would ask Sarani when things happened and he would say, ‘I was already wearing shorts,’ or ‘Before my first wife died,’ or ‘While I was still strong,’ or ‘When the coconut palms were so high,’ or ‘Before Kapalai was washed away.’ These were the singular events against which his time was measured.

The heat had gone out of the afternoon and Minehanga had been busy while we were talking. She had cooked up the dolen Sarani had gathered – the téhé-téhé had been given away. A steaming dish was brought out to the bow, the motive claw of each mollusc projecting now that it had been boiled, and forming a dainty handle by which to pull it from the conical shell. They tasted like whelks. ‘Kahanga are better, but we save them for market.’ The empties went back into the water, waiting for squatters; eventually the dead shells would rise up and walk away on the legs of hermit crabs.

Pilar came back from the reef and began to sort out his deepwater net. We went with him when he set out to the south-east to lay it off the Ligitan Reef. We talked more after a supper of boiled fish, sitting out on the foredeck in the darkness before the moon rose. The boat bobbed in the light breeze. Arjan came out to join us, sitting in the crook of his father’s legs and banging on the Tupperware betel box. Minehanga was singing Mangsi to sleep, a lullaby sung in her raucous voice above the soft noises of water and air, but it was strangely soothing in the glow of the oil lamp.

Across the dark sea the lights of the Water Village showed where Mabul lay and reminded Sarani of something that had been puzzling him.

‘Many tourists go there. Woi, many.’ I agreed. ‘I have seen many white people there, men and women, husbands and wives. But I have not seen children. How can this be? Do they not have children? Do they not sleep together?’

‘Of course there are children, but they do not always go with their parents.’

‘They leave their children behind? How can they do that? I could not do that. Arjan would just cry and cry.’ He thought awhile. ‘They have many children? As many as we do?’

‘Sometimes, but usually two, maybe three.’

‘So few? I had seven with my first wife and now three more. It’s a problem for me. I am old, and I have three young children. If they live, I don’t want to have any more. Minehanga doesn’t want to have any more. It is very difficult. I am still strong for playing love. How can they have so few?’

‘Ada obat, there is medicine.’ Obat is a general word in Malay, and takes in herbal preparations and traditional cures as well as what a doctor would dispense. It can also include magic. His expression brightened.

‘Obat kampung? Village medicine?’

‘No, there is a pill.’

‘A friend told me this, but I did not believe him. And I can drink this pill?’ He was eager to join the fertility revolution however late in the game.

‘No, it is for the woman.’

‘Oh, I see. Can I find this pill in Semporna?’

I tried to picture Minehanga with a blister pack in her hand, popping a pill through the silver foil, remembering to do it every day, and could not.

‘It is not just one pill.’ I replied. ‘It is one pill every day and if you forget one day maybe it does not work. Maybe it is not good for Minehanga. But there is also medicine for the man.’

‘Oh? I drink this one?’

How to explain a condom? I did not even have the requisite vocabulary for the body parts involved. I improvised and came up with a gloss along the lines of a rubber sock that stopped the white water from going into the body of the woman. There was pointing involved, hand signals. Sarani got the message.

‘Do you have any of this medicine? Can I find it in Semporna?’

I found myself wondering how sexual relations were conducted in a communal living space, amongst sleeping children and relations, and the answer was: quietly. The boat rocking anyway, the planks creaking, who would notice?

Throughout our conversations Sarani appended the phrase ‘if they live’ to every mention of children. I could imagine infant mortality being high in this environment, but the way he said it was like touching wood, as though to expect them to survive were to be presumptuous. Maybe this was the thinking behind the casual attitude adults adopted towards children, paying them surprisingly little attention, trying not to become too fond of them in case they did not live.

The breeze died away. There were stars down to the edges of the sky, and the waxing moon rose massive on the horizon. In the calm, sounds came clearly from the other boats. Pilar was pumping out the bilge, the handle squeaking. The light from a hurricane lamp brightened to a glare in the stern of another boat where figures moved, lit from the waist down. The lamp was passed down into a dug-out and strapped to the bow. It moved slowly out over the reef. Other canoes followed.