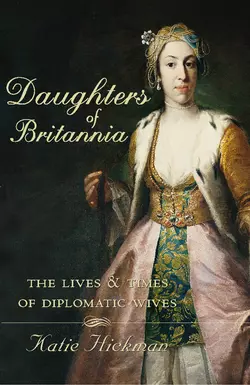

Daughters of Britannia: The Lives and Times of Diplomatic Wives

Katie Hickman

This edition does not include illustrations.An authoritative and entertaining account by one of our most talented writers of the courageous and unusual women who have been the backbone of the British Empire and foreign service.‘English ambassadresses are usually on the dotty side and leaving their embassies drives them completely off their rockers’ – Nancy MitfordFrom the first exploratory expeditions into foreign lands, through the heyday of the British Empire and still today, the foreign service has been shaped and run behind the scenes by the wives of ambassadors and minor civil servants. Accompanying their spouses in the most extraordinary, tough, sometimes terrifying circumstances, they have struggled to bring their civilization with them. Their stories – from ambassadresses downwards – never before told, are a feast of eccentricity, genuine hardship and genuine heroism, and make for a hilarious, compelling and fascinating book.

KATIE HICKMAN

Daughters of Britannia

The Lives and Times of Diplomatic Wives

Dedication (#ulink_b2daad8e-664d-5d18-80ef-3d159cc6c57c)

For Beatrice Hollond,a diamond amongst friends

Contents

Cover (#u4b57d622-9c55-5cd5-ac56-ba12ce00ef92)

Title Page (#uf8bde525-b423-556c-ae0d-769cb04046d7)

Dedication (#u837a75b2-cd95-552d-8b03-9ca12b6957cd)

List of Principal Women (#uaffcb746-2ec1-5212-bc95-fd71b18f603f)

Introduction (#u4bb27370-fcb2-5965-8d87-c4e13464f20e)

Prologue (#ue9f509c4-4d05-5b0f-8827-9cf1e42b8dbc)

1. Getting There (#u8ecfd78a-b379-5776-ab67-de970a2fef4b)

2. The Posting (#ud80429a5-2254-5238-9654-2f3f797feafa)

3. Partners (#ub2bb95cb-7b52-57de-8517-4a1db6e1f220)

4. Private Life (#litres_trial_promo)

5. Embassy Life (#litres_trial_promo)

6. Ambassadresses (#litres_trial_promo)

7. Public Life (#litres_trial_promo)

8. Social Life (#litres_trial_promo)

9. Hardships (#litres_trial_promo)

10. Children (#litres_trial_promo)

11. Dangers (#litres_trial_promo)

12. Rebel Wives (#litres_trial_promo)

13. Contemporary Wives (#litres_trial_promo)

Plates (#litres_trial_promo)

Keep Reading (#litres_trial_promo)

Bibliography (#litres_trial_promo)

Index (#litres_trial_promo)

Acknowledgments (#litres_trial_promo)

List of Illustrations (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

Author’s Note (#litres_trial_promo)

Notes (#litres_trial_promo)

Also by the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

Copyright (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

A List of the Principal Women in the Book and the Primary Places Where They Served (#ulink_b6f96889-264a-5e4f-a8af-ed8a9869e42d)

Introduction (#ulink_7d646217-1ce4-52f7-9dc5-3bd151021578)

‘English ambassadresses are usually on the dotty side, and leaving their embassies nearly drives them completely off their rockers.’ These words, from Nancy Mitford’s classic vignette of embassy life Don’t Tell Alfred, were like a mantra of my youth. As children, my brothers and I used to chant them to my mother, in those days a British ambassadress herself, in her vaguer moments. Not because she was dotty (well, only occasionally) but because we knew, beyond doubt, that all other ambassadresses were.

From an early age, we were used to the tales of former ambassadresses – mad, bad and dangerous to know, they came to form part of our family culture. In New Zealand, my father’s first posting as a young first secretary, there was the delightfully distraite Lady Cumming Bruce. She was far more interested in her painting than in her diplomatic social engagements, which often slipped her mind completely; according to legend, she could regularly be spotted crawling through the residence shrubberies, so as not to be spotted arriving late for her own parties. ‘Dear Mummy and Daddy,’ my mother wrote to my grandparents just a few months after her arrival in Wellington, ‘Lady Cumming Bruce is very vague and difficult to pin down – says she’ll do something and then doesn’t. When Helen

(#ulink_2edeaeae-fd8b-57a1-a24f-d401a86ad39c) went onto their boat to greet them on arrival she suggested to Lady CB that she should perhaps put her hat on before meeting the press. Lady CB opened her hat box inside which instead of a hat, was a child’s chamber pot.’

During the twenty-eight years that my mother spent as a diplomat’s wife, she wrote letters home. Today, at my parents’ house in Wiltshire, in amongst the paper rubbings from the temples at Angkor Wat, the Persian prayer mats and the bowls of shells from the beaches of Connemara – the legacy of a lifetime’s wanderings – there is a carved wooden chest which contains several thousand of them. Once a week with almost religious regularity – sometimes more frequently – these letters were written at first to my grandparents and my aunt, but then later also to myself and my two brothers when we were sent home to boarding school in England. During the last ten years of her travelling life it was not unusual for her to write half a dozen letters a week, recording all the vicissitudes of diplomatic life.

In these days of instant communications, of faxes and e-mails and mobile telephones, it is hard to describe the extraordinarily intense pleasure of what used, in old fashioned parlance, to be called ‘a correspondence’. As a bitterly homesick ten-year-old at boarding school for the first time, I found in my mother’s letters an almost totemic significance. The main stairs of my school house wound down through the middle of the building around a central well; in the hall below was a wooden chest on which the post was always laid out. For some reason only the housemistress and the matron were permitted to use these stairs (the rest of us were confined to the more workaday stone stairs at the back of the house), so the trick was to crane over the banisters and try to spot your letters. From two storeys up it was impossible to read your name but, to a practised eye, the form of a certain handwriting, the shape of a certain envelope, its colour or its thickness, were all clues.

Occasionally my mother would use the official embassy writing paper – thick sheaves of a creamy sky-blue colour, lavishly embossed with the royal crest – but it wasn’t really her style. For most of my school days she used the same big pads of plain white airmail paper, slightly crinkly to the touch, bordered in red and blue, which she bought in industrial quantities from an English stationer’s. Often I would carry her letters around with me in my pocket, unopened, for a whole morning, until I could escape somewhere private in which to savour them. Their fatness, their pleasing weight, their peculiar texture against my fingertips had an almost magical power to soothe. These letters carried news of my family, of course, but perhaps more importantly they described another world, and another way of life. They described another part of myself, in fact, which was as strange to my English friends as the land of the Jabberwock or the Yonghy-Bonghy-Bo.

I kept these letters, and many years later they were to be the inspiration for this book. Although I have quoted them here only occasionally, what they have given me is a strong sense not only of the value of the experiences they describe, but also of their fragility. One of my main aims in writing this book is to preserve them, and others like them, lest, like Lady Winchilsea’s, their stories should drift into oblivion.

The lives of the women described in this book represent a lacuna in history. While the experiences of their menfolk were recorded and preserved for posterity even as far back as the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries,

(#ulink_931e3ce1-44d3-528a-968c-f842b44d553f) what these women saw or felt or did is unknown. Because, with a few rare exceptions, they were not involved in affairs of state, they were quite simply not considered important enough. Because they were women, their experience had no value, and even their presence often went unrecorded. To quote the well-worn feminist joke, the history of diplomacy is very much a ‘his-story’.

Of all the women whose experiences I have drawn upon in this book, Lady Winchilsea, who in 1661 made the long and perilous journey to Constantinople at her husband’s side, is the earliest. I am in no doubt that there were others before her, for the custom of sending resident ambassadors abroad, initiated by the Italians during the Renaissance, had begun to spread through the rest of Europe by the beginning of the sixteenth century,

(#ulink_5413a33f-d006-5025-9486-fa1ab8baa37e) but any records for them are almost impossible to find.

Even when we do have a fleeting glimpse of them (as in the case of the Countess of Winchilsea) their stories are tantalizingly elusive. Did Lady Winchilsea, like one of her more famous successors, Lady Mary Wortley Montagu, ever visit a harem or one of the imperial city’s glorious marble-domed hammams? Did she, like Mary Elgin nearly a century and a half later, go disguised in man’s clothing to watch her husband present his credentials to the Grand Seignior? What of the everyday practicalities of her life? What were the conditions she had to endure aboard ship? Did she have children whom she was forced to leave behind? Perhaps, like her contemporary Ann Fanshawe, she fell pregnant and gave birth thousands of miles from home. If so, did her child survive?

Although we will never know what Lady Winchilsea thought and felt when she arrived in Constantinople in 1661, remarkably, many accounts of the lives and experiences of diplomatic women have survived. Until well into the first half of this century many of them wrote letters home; these letters are often the sole record we have of them. A handful are already well-known names – Mary Wortley Montagu, Vita Sackville-West, Isabel Burton. The vast majority are not. Who was Mrs Vigor, gossiping from St Petersburg in the 1730s about the scandals and intrigues of the imperial court? Or Miss Tully, incarcerated for over a year in the consulate in plague- and famine-torn Tripoli on the eve of the French Revolution? We know almost no personal details about them (not even their Christian names). Nor do we know who their correspondents were, only that their letters were precious enough to someone, as my mother’s were to me, to have been safely kept. A great number of the sources I have used – collections of letters, private journals, or memoirs largely based on them – were never intended for public consumption at all: only a hundred or so copies were sometimes published through private subscription for family and friends. Why did they write these letters? No doubt they longed for news from home; but perhaps they also felt compelled to describe the circumstances of their lives abroad – so exhilarating, so strange, so inexplicable – to their family and friends. In Moscow in 1826 Anne Disbrowe enjoys the festivities which took place at the coronation of Tsar Nicholas I; in Peking, some fifty years later, at the heart of the Forbidden City itself, Mary Fraser takes tea with the legendary Chinese Dowager Empress Tzu Hsi; while at the turn of this century, during her seventeen long years in Chinese Turkistan, Catherine Macartney witnesses not one, but two full eclipses of the sun.

Others have more perilous tales to tell, of famines, plagues, tempests, earthquakes, wars, kidnappings, assassination attempts, and of the illnesses and deaths of their children. Even today – perhaps especially today – the world remains a hostile place for many diplomats. Their families, my own included, have often felt that the real substance of their lives is greatly, and at times almost wilfully, misunderstood. As one wife recently wrote in the BDSA (British Diplomatic Spouses Association) Magazine: ‘All Britons KNOW that diplomatic life is one long whirl of gaiety (they have seen the films and read the books)…’ Although this may be true for a few, most of the women represented here have very different stories to tell. ‘I shall never forget the utter despair into which the sight of my new home plunged me,’ wrote Jane Ewart-Biggs of her arrival as a young wife at her first posting in Algiers. From the outside their house – the central block of the old British hospital – seemed solid enough, but the interior was in a state of total disrepair, the paint flaking from the walls and doors hanging on single hinges. In the entrance hall a huge hole gaped through the ceiling ‘through which pipes and wires hung like intestines’. By the time her husband Christopher came home she was in tears. He, by contrast, was buoyed up by the fascinating day he had spent learning all about his new job. ‘It was then that I realised that the major problems arising from our nomadic life were going to affect me rather than him,’ Jane wrote, ‘and that the same circumstances creating political interest for him would make my life especially difficult.’

(#litres_trial_promo)

Whatever the external circumstances, for the most part these are personal stories told from within. Their sphere is essentially domestic. Whether they are writing from Persia or St Petersburg, these women (mostly wives, but some daughters and sisters, too) describe the concerns of any ordinary Englishwoman: children, dogs, gardens, houses, servants, clothes, food. Politics, except on the occasions when they came into direct conflict with their lives, are only incidentally discussed. What they engage with instead is daily life. For the contemporary reader the women’s subjectivity has a peculiar veritas which is frequently absent from their husbands’ more distanced and perhaps more scholarly approach. What they do, brilliantly, is to describe what life was really like. It is this, more than anything else, which is their particular genius.

Who, today, would want to read Colonel Sheil’s ponderous ethnographic dissertation on Persia in the mid-nineteenth century?

(#ulink_6cbedbad-6b7f-518b-8e9f-28f4d9892d98) The memoir of his wife Mary, however, contained in the same volume, while politically almost entirely uninformative, has a freshness and drama which remains undimmed by time. Mary vividly describes her agonizing 1,000-mile journey with three small children and an invalid husband through the Caucasus Mountains from Tehran to Trebizond on the Black Sea (from whence they were able to sail to England). She recorded with simple stoicism how they waded up to their knees through the freezing snow, eating only dry crusts and sleeping in stables: ‘I learned on this journey that neither children nor invalids know how much fatigue and privation they can endure until they are under compulsion.’

(#litres_trial_promo)

In writing Daughters of Britannia I have drawn on the experiences of more than 100 diplomatic women. Their lives span nearly 350 years of history, and encompass almost every imaginable geographical and cultural variation, from the glittering social whirl enjoyed by Countess Granville in Paris after the Napoleonic Wars, to the privations suffered at the turn of this century by that redoubtable Scotswoman, Catherine Macartney, who in her seventeen years in Kashgar, in Chinese Turkistan, saw only three other European women.

Many of these women lived unique lives. Some saw sights which no other English person, man or woman, had ever seen. And yet, despite their vast differences – in character and taste as much as circumstances – a bond of shared experience unites them; a diplomatic ‘culture’ which was both official and intensely personal. Even though they are separated by nearly 200 years, when the anguished Countess of Elgin writes about her longing for news from home, it could be my own mother writing.

Dearest Mother,

Do not expect this to be an agreeable letter. I am too much disappointed in never hearing from home; the 17th July is the last from you, almost six months!… I can’t imagine why you took it into your heads that we were going home; for I am sure I wrote constantly to tell you that we were at Constantinople, and why you would not believe me I know not. If you knew what I felt when the posts arrive and no letters for me, I am sure you would pity me. I shall write to nobody but you, for I feel I am too cross.

(#litres_trial_promo)

In the Elgins’ day the journey from England to Constantinople was not only long and arduous, it was also hazardous. Messengers were frequently attacked and robbed, and every single precious letter either destroyed or lost. Amazingly, even in the late twentieth century the non-arrival of the bag has been the cause of as much disappointment and pain. Here is my mother to my brother on 23 May 1978: ‘Darling Matthew, Boo hoo! The bag has let us down, and there is gnashing of teeth here, and blood is boiling.’ And to myself, on the same day: ‘Darling Katie, The bloody bag has let us down yet again and we have no letters from any of you. We are so mad we could spit …’

What qualities were needed in a diplomat’s wife? In Mary Elgin’s day nobody would have thought it necessary to enumerate them. Of course, plenty was written on the qualities required in a man. In the sixteenth century, when the idea of sending a resident ambassador abroad was still fairly new, these were frequently listed in treaties and manuals. A man (in Sir Henry Wotton’s famously ambiguous phrase) ‘sent to lie abroad for the good of his country’ was required to have an almost impossibly long list of attributes. He should be not only tall, handsome, well-born and blessed with ‘a sweet voice’ and ‘a well-sounding name’,

(#litres_trial_promo) but also well read in literature, in civil and canon law and all branches of secular knowledge, in mathematics, music geometry and astronomy. He should be able to converse elegantly in the Latin tongue and be a good orator. He should also be of fine and upstanding morals: loyal, brave, temperate, prudent and honest.

An important ambassador’s entourage could include secretaries and ‘intelligencers’, a chaplain, musicians, liverymen, a surgeon, trumpeters, gentlemen of the horse, ‘gentlemen of quality who attended for their own pleasure’, young nephews ‘wanting that polish that comes from a foreign land’, even dancing and fencing masters. But never a wife.

The ideal diplomatic wife was more difficult to describe: ‘Just as the right sort can make all the difference to her husband’s position,’ wrote Marie-Noele Kelly rather forbiddingly in her memoirs, ‘so one who is inefficient, disagreeable, disloyal, or even merely stupid, can be a millstone around his neck.’

(#litres_trial_promo) Although there have been some magnificent millstones – Lady Townley’s infamous ‘indiscretions’ forced her husband to retire from the service – there is no doubt that all the staunchest qualities deemed necessary in men were required in their wives, too. Circumstances have often demanded of them unimaginable courage and reserves of fortitude.

This book is the story of how such women survived. It is the story of many lives lived valiantly far away from family and friends; and of the uniquely demanding diplomatic culture which sustained (and sometimes failed to sustain) these women as they struggled, often in very difficult conditions, to represent their country abroad. Although their role, in the eyes of ‘his-story’, lay very much behind the scenes, I believe that this is precisely why their testimony is so valuable: it was in coping with quite ordinary things, with the daily round of life, that their resilience and resourcefulness found its greatest expression.

My only regret is for the lives which, even after more than two years’ searching, have continued to elude me. So it is only in my imagination that I can describe for you what it must have been like for Lady Winchilsea as she sailed into Constantinople, that city of marvels, by her husband’s side that afternoon. Perhaps she, like the ambassador, was dressed in her court robes, still fusty and foul-smelling from their long confinement in a damp sea-trunk. Dolphins were still a common sight in the Bosphorus in those days, and I like to think of her watching them riding the bow-waves in front of the ship as it came into the harbour at last, the fabled city rising before them, its domes and minarets shining in the pink and gold light.

* (#ulink_e598bb9a-df58-50b3-af28-9772db73dd76) Helen Pickard, the wife of the deputy high commissioner.

* (#ulink_02c11946-32c3-5728-b670-72ceaf29008c) Manuscript copies of these documents, often written in the form of relazione (‘A narrative of …’), were considered so valuable that they often commanded large sums, even in their own time.

† (#ulink_edf155ba-002c-577c-b99e-73dd35593ad1) Previously, the role of an ambassador was usually to complete a short-term mission – to declare war or negotiate a treaty. England’s first permanent ambassador, John Shirwood, became resident in Rome in 1479. In 1505 John Stile was sent to Spain by Henry VII, where he became the first resident ambassador to a secular court. By the mid-seventeenth century the idea of permanent missions abroad was no longer a novelty in England, but neither was it a universal practice. During the Restoration (1660–68) the crown sent diplomatic missions to thirty countries, but permanent embassies to only five (France, Spain, Portugal, the United Provinces and the Hanse towns of Hamburg, Bremen and Lübeck). Turkey and Russia were in a special category: ambassadors were sent there in the name of the monarch, but were in fact paid servants of the Turkey Company or British merchants settled in Moscow.

* (#ulink_cc7f4ca4-e4bd-5619-8e13-eb755fa842b4) Colonel Sheil was the British minister in Tehran on the eve of the Crimean War.

Prologue (#ulink_2ee89399-4f0f-577b-8756-d68810a9a5d4)

It was the late afternoon when His Excellency the Earl of Winchilsea, Ambassador Extraordinary from King Charles II to the Grand Seignior Mehmed IV, Sultan of Sultans and God’s Shadow upon Earth, sailed into Constantinople.

To arrive in Constantinople by sea, even today, is to be presented with an extraordinary sight. In 1661 it was one of the wonders of the world. Built on seven hills, and surrounded on three sides by water, it was described by contemporary travellers as not only the biggest and richest, but also the most beautiful city on earth. The unequal heights of the seven hills, each one topped with the gilded dome and minarets of a mosque, made the city seem almost twice as large as it really was. On each hillside, raised one above the other in an apparent symmetry, were palaces, pavilions and mansions, each one set in its own gardens, surrounded by groves of cypress and pine. On the furthermost spit of land, and clearly visible from the sea, was the Seraglio,

(#ulink_052b914f-8c69-5454-99c3-4b2b1968828e) the Sultan’s palace, its turrets and domes reflected in the waters of the Bosphorus.

Few buildings in history have had the sinister beauty of this fabled pleasure dome. No contemporary Christian king, and only a few since, had aspired to anything that equalled it. Built around six great courtyards, and covering as much land as a small town, this city within a city was the focus of all life in Constantinople. The Seraglio was not only the symbol of all power in the great Ottoman empire but also, to the dazzled imagination of foreign travellers, the seat of all pleasures too. For it was here, too, that the Grand Seignior’s harem was incarcerated – several hundred concubines, beautiful slave girls bought from as far away as Venice, Georgia and Circassia and kept, out of sight of other eyes, for the Sultan’s delight alone.

Here, every day, as many as 10,000 people were catered for – including the four corps of guards who protected the Seraglio, the black and white eunuchs, the palace slaves, its pages, treasurers, armourers, grooms, physicians, astrologers and imams, as well as the Sultan and his family. According to one estimate there were 1,000 cooks and scullions working in the palace kitchens which, in addition to staples such as meat and vegetables, produced jams, pickles, sweetmeats and sherbets in quantities ‘beyond possibility of measure’.

(#litres_trial_promo)

Opposite the Seraglio, and close enough to be easily visible from it, rose the graceful shores of Asia, a pleasing prospect of wilderness interspersed with villages and fruit trees. And on the narrow stretch of water in between them sailed the water traffic of the world.

It was three months since the ambassador’s entourage had set sail, and the journey had not been an easy one. On New Year’s Day, just after they had left Smyrna on the last leg of their voyage, a tempest had all but tossed them into oblivion. During the week of the storm their vessel had been cast upon rocks five times, leaving every man on board fearing for his life. It was an escape ‘so miraculous and wonderfull, considering the violence of the storm, the carere and weight of our ship, as ought to make the 8 day of January for ever to be recorded by us to admiration, and anniversary thankfulness for God’s providence and protection,’ wrote one witness.

(#litres_trial_promo)

Now, the ambassador’s storm-battered, leaky little ship – its masts, yards and decks encrusted eerily with white salt from the continual spray of the sea, its flags and ensigns flying, its guns at the ready – sailed across the last stretch of the Sea of Marmara and into the Bosphorus at last. It must have seemed to those on board as if they had reached the very epicentre of the world.

In many ways, of course, they had. Whoever controlled Constantinople controlled not only the great gateway between Europe and Asia, but also one of the greatest water trade routes linking the northern and southern hemispheres. Looking north, the Black Sea gave access through the Volga to southern Russia, and through the Danube to the Balkans and eastern Europe. To the south, the Sea of Marmara led not only to the Aegean, but to the whole of the Mediterranean, North Africa and beyond. In amongst the fishing boats and the caiques, the galleons and perhaps even one of the Sultan’s magnificent gilded barges, sailed innumerable vessels from all four corners of the earth – merchant ships, slave galleys and vast timber rafts cut from the deep forests of southern Russia and floated down the Bosphorus for shipbuilding and fuel.

On the captain’s orders the men lined the rigging, their muskets at the ready. As the ship drew close to the Sultan’s palace, in a suffocating cloud of gunpowder, a salutation of sixty-one guns was fired. A little while later, when the ambassador finally disembarked, it was to a second deafening salute of fifty-one guns. His welcoming committee comprised not only his own servants, English merchants, and other travelling companions brought with them from Smyrna, but also many of the Grand Seignior’s officers who had come to honour him. Their procession was so splendid that multitudes of people flocked from all parts of the city to watch them, and made ‘the business of more wonder and expectation’. ‘As we marched all the streets were crowded with people and the windows with spectators, as being unusual in this countrey to see a Christian Ambassadour attended with so many Turkish officers,’ wrote the ambassador’s secretary. He was so proud of their ‘very grand equipage’ – believing that ‘none of his predecessours, nor yet the Emperour’s Ambassadours, can boast of a more honourable nor a more noble reception’ – that he recorded each element:

1. The Vaivod

(#ulink_a471ef36-7575-54b6-a229-67e24730e4f2) of Gallata and his men

2. The Captain of the Janizaries with his Janizaries

3. The Chouse Bashaw with his Chouses

(#ulink_47fb461d-676c-5265-8be1-c9f232307fb8)

4. The English Trumpeters

5. The English horsemen and Merchants

6. My Lord’s Janizaries

7. The Druggerman

(#ulink_bf97b894-1da9-5477-9583-8e61ccb9bff6)

8. My Lord himself with Pages and Footmen by his side

9. My Lord’s gentlemen

10. The officers and reformadoes of the ship.

(#litres_trial_promo)

From the brief account of the voyage which has come down to us, we know that the Sultan presented the embassy with ten sheep, a hundred loaves of bread, twenty sugar loaves and twenty wax candles. We also know that the ambassador distributed money among the people, and was visited by the messengers of other foreign ambassadors to the Porte. We know that he was given audiences with both the Grand Vizier, and with the Grand Seignior himself.

But we can only speculate about the Countess of Winchilsea’s role in all this. The fact that we know she was there at all seems almost accidental. At the very tail end of the procession, in between ‘my Lord’s gentlemen’ and ‘the officers and reformadoes of the ship’, the ambassador’s secretary has inserted one simple phrase: ‘My Ladies Coach’. With these three small words, my Lady Winchilsea slips into history.

* (#ulink_5d151688-295c-5852-bfc0-13df9ed42028) The Topkapi Palace.

* (#ulink_ec70e588-41cf-58b3-9da0-17fd5820f472)Voyvoda, or Governor of Gallata.

† (#ulink_80897f08-9c17-56ae-828b-0d9a7c7a9990)The chief guard and his guards.

‡ (#ulink_b4465cb3-b1e8-58d8-91a0-e6c5954a4816)Dragomen, or interpreters.

1 Getting There (#ulink_f14de7ae-0688-55d1-b719-8f961754da8e)

Sometime at the beginning of April 1915 a lonely Kirghiz herdsman wandering with his flocks in the bleak mountain hinterland between Russian and Chinese Turkistan would have beheld a bizarre sight: a purposeful-looking Englishwoman in a solar topi, a parasol clasped firmly in one hand, striding towards the very top of the 12,000-foot Terek Dawan pass.

Ella Sykes, sister of the newly appointed British consul to Kashgar, was dressed in a travelling costume which she had invented herself to cope with the rigours of the journey. Over a riding habit made of the stoutest English tweed was a leather coat. On her legs she wore a pair of thick woollen puttees, while her hands were protected by fur-lined gloves. On her head she wore a pith helmet swathed in a gauze veil, and beneath it, protecting her eyes from the terrible glare of the sun in that thin mountain air, a pair of blue glass goggles. If the herdsman had been able to see beneath this strange mixture of arctic and tropical attire, he would have seen that her cheeks and lips were swollen, her skin so badly sunburnt that it was peeling from her face in large painful patches. But her eyes, behind those incongruous goggles, sparkled with a very English combination of humour and good sense. ‘Such slight drawbacks’, she would later record, ‘matter little to the true traveller who has succumbed to the lure of the Open Road, and to the glamour of the Back of Beyond.’

(#litres_trial_promo)

The glamour described by Ella Sykes is not of the kind usually associated with diplomatic life. This mysterious existence invariably brings to mind a vague impression of luxury – of diamonds and champagne, of vast palaces illuminated by crystal chandeliers, of ambassador’s receptions of the Ferrero Rocher chocolates advertisement variety. While it is relatively easy to conjure with these fantastical images (for on the whole this is what they are) it is much more difficult to imagine the reality behind them. To contemplate Ella Sykes on her journey across the Terek Dawan pass

(#ulink_82e3104a-6dc2-5f8f-8fb0-bc5302d6766b) is to invite a number of questions. Who were these diplomatic women, and what were their lives really like? Where did they travel to, and under what circumstances? And, most important of all, how did they get there in the first place?

In 1915 an expedition to Kashgar, in Chinese Turkistan, was one of the most difficult journeys on earth. Following the outbreak of the First World War, the normal route for the first leg of the journey – across central Europe and down to the Caspian Sea – had become too dangerous, and so Ella and her brother Percy travelled to Petrograd (St Petersburg) on a vastly extended route via Norway, Sweden and Finland. From Petrograd they went south and east to Tashkent, the capital of Russian Turkistan, on a train which lumbered its way through a slowly burgeoning spring. At stations frothing with pink and white blossom, children offered them huge bunches of mauve iris, and the samovar ladies changed from their drab winter woollens into flowered cotton dresses and head-kerchiefs.

For all these picturesque scenes, even this early stage of the journey was not easy: the train had no restaurant car, and the beleaguered passengers found it almost impossible to find food. At each halt, of which luckily there were three or four a day, they would all leap off the train and rush to buy what they could at the buffets on the railway platforms, gulping down scalding bowls of cabbage soup or borsch in the few minutes that the train was stationary. The further east they travelled, the more meagre the food supplies became, until all they could procure was a kind of gritty Russian biscuit. Without the soup packets they had brought with them, Ella noted with some sang-froid, they would have half starved.

From Tashkent Percy and Ella took another train to Andijan, the end of the line, and from here they travelled on to Osh by victoria.

(#ulink_c139fd2c-6690-5d0a-bc5a-1da74739410f) Here they found that Jafar Bai, the chuprassi (principal servant) from the Kashgar consulate, had come to meet them. Under his careful ministrations they embarked on the final stage of their journey, the 260-mile trek across the mountains.

At first they met a surprising number of people en route: merchants with caravans laden with bales of cotton; Kashgaris with strings of camels on their way to seek work in Osh or Andijan during the summer months: ‘Some walked barefoot, others in long leather riding boots or felt leggings, and all had leather caps edged with fur.’ The long padded coats they wore were often scarlet, ‘faded to delicious tints’, and they played mandolins or native drums as they went. On one occasion they met a party of Chinese, an official and a rich merchant, each with his retinue, also bound for Kashgar.

The ladies of the party travelled in four mat-covered palanquins, each drawn by two ponies, one leading and one behind [Ella wrote], and I pitied them having to descend these steep places in such swaying conveyances. They were attended by a crowd of servants in short black coats, tight trousers and black caps with hanging lappets lined with fur, the leaders being old men clad in brocades and wearing velvet shoes and quaint straw hats.

At night Ella and her brother stayed in rest-houses, which in Russia usually consisted of a couple of small rooms, with bedsteads, a table and some stools. Sometimes these rooms looked out onto a courtyard where their ponies were tied for the night, but often there was no shelter for either the animals or their drivers. Over the border in China these rooms became more rudimentary still, lit only by a hole in the roof. The walls were of crumbling mud, the ceilings unplastered, their beams the haunt of scorpions and tarantulas. Up in the mountains, of course, there were no lodgings of any kind. The Sykeses slept in akhois, the beehive-shaped felt tents of Kirghiz tribesmen, their interiors marvellously canopied and lined with embroidered cloths. In the remotest places of all they slept in their own tents.

According to Ella’s account, these nights spent in the mountains were attended by a curious mixture of the rugged and the grandiose. Wherever they stopped, Jafar Bai would instantly make camp, setting up not only their camp-beds, but also tables to write and eat at, and comfortable chairs to sit on. While he heated the water for their folding baths, another servant prepared the food. After the gritty Russian biscuits and packet soups, a typical breakfast – steaming coffee and eggs, fresh bread and butter with jam – must have seemed like a banquet. The Russian jam, delicious as it was, had its drawbacks. In a state of ever-accelerating fermentation, the pots had a habit of exploding like bombs, causing havoc inside Jafar Bai’s well-ordered tiffin basket.

The routine was one which the Sykeses were to adopt for all their travels in Turkistan: ‘The rule was to rise at 5 a.m., if not earlier,’ Ella wrote, describing a typical morning in camp,

and I would hastily dress and then emerge from my tent to lay my pith-hat, putties, gloves and stick beside the breakfast table spread in the open. Diving back into my tent I would put the last touches to the packing of holdall and dressing-case, Jafar Bai and his colleague Humayun being busy meanwhile in tying up my bedstead and bedding in felts. While the tents were being struck we ate our breakfast in the sharp morning air, adjusted our putties, applied face-cream to keep our skins from cracking in the intense dryness of the atmosphere, and then would watch our ponies, yaks or camels as the case might be, being loaded up.

(#litres_trial_promo)

Most days they would walk for an hour or so before they took to their mounts. Ella usually rode sidesaddle, but on these long journeys she found it less tiring to alternate with ‘a native saddle’, onto which she had strapped a cushion. Her astride habit, she noted, did for either mode. They would march for five hours before taking lunch and a long rest in the middle of the day, wherever possible by water, or at least in the shade of a tree. Then, when the worst of the midday heat was over, they would ride for another three or four hours into camp (the baggage animals usually travelling ahead of them) ‘to revel in afternoon tea and warm baths’. This was Ella’s favourite time of the day, not least because she could brush out her hair, which she had only hastily pinned up in the morning, and which by now was usually so thick with dust that she could barely get her comb through it.

At high altitude – sometimes they were as high as 14,000 feet – she suffered from the extremes of temperature. During the day, beneath a merciless sun, in spite of her pith hat and sun-umbrella, she often felt as if she was being slowly roasted alive, while the nights were sometimes so cold that she was forced to wear every single garment she had with her, with a fur coat on top. ‘My feet were slipped into my big felt boots lined with lamb’s wool,

(#ulink_ba3a27e3-31e9-5d92-83e3-2f7668e1917e) and a woollen cap on my head completed the costume in which I sat at our dinner table.’ Thus prepared, she felt perfectly ready, she wrote, ‘to meet whatever might befall’.

In Ella Sykes’s day a woman, diplomatic or not, was really not supposed to take with quite such aplomb to the challenges of ‘the back of beyond’. It was not just her physical but her mental frailty, too, which was the impediment. If women themselves were in any doubt about this, then useful handbooks such as Tropical Trials, published in 1883, were on hand to tell them so.

Many and varied are the difficulties which beset a woman when she first exchanges her European home and its surroundings for the vicissitudes of life in the tropics [warned its author, Major S. Leigh Hunt]. The sudden and complete upset of old-world life, and the disturbance of long existing association, produces, in many women, a state of mental chaos, that utterly incapacitates them for making due and proper preparations for the contemplated journey.

(#litres_trial_promo)

Not only the preparations, but the departure itself, according to the major, were likely to reduce a woman to a state of near imbecility, coming as she did in moral fibre somewhere between ‘the dusky African’ and ‘the heathen Chinee’. When embarking on a sea voyage, farewells with well-wishers of a woman’s own sex were best done on shore, he advised, while ‘a cool-headed male relation or friend’ was the best person to accompany the swooning female on board.

In real life, of course, women were made of much sterner stuff, but nevertheless departures were often very painful. ‘The parting with my people was unexpectedly terrible,’ wrote Mary Fraser on the eve of her first diplomatic posting to China in 1874. ‘Till the moment came I had not realised what it was to mean, this going away for five years from everything that was my very own.’ Revived by a glass of champagne, thoughtfully provided by her husband Hugh, she soon pulled herself together, however, and ‘by the time the sun went down’, she would remember, ‘on a sea all crimson and gold, my thoughts were already flying forward to all the many strange and beautiful things I was so soon to see.’

(#litres_trial_promo)

This poignant mixture of excitement and regret is probably superseded by only one other concern. Thirty years after Ella Sykes travelled to Chinese Turkistan, Diana Shipton was told by her husband Eric that he had been offered the post of consul-general in Kashgar. ‘Mentally,’ she wrote, ‘I began immediately to pack and to plan.’

(#litres_trial_promo)

The notion of travelling light has always been an alien one to diplomatic wives. ‘We are like a company of strolling players,’ wrote Harriet Granville, only half jokingly, en route to Brussels in 1824. Over the centuries many others must have felt exactly the same. When Lady Mary Wortley Montagu, whose husband Edward was appointed ambassador to Constantinople, arrived in Turkey in 1717, the Sultan lent their entourage thirty covered wagons and five coaches in which to carry their effects. Mary Waddington, who travelled to Russia in 1883, did so with a staff of thirty-four, including a valet and two maids, a master of ceremonies, two cooks, two garçons de cuisine, three coachmen and a detective. ‘Four enormous footmen’ completed the team, Mary recorded with gentle irony, ‘and one ordinary sized one for everyday use’.

(#litres_trial_promo) Even as recently as 1934, when Marie-Noele Kelly arrived by P & O in Cairo, she was accompanied by three European servants, three children, and fourteen tons of luggage.

(#ulink_c8a897a1-07fb-5450-836d-e3bdeb55c1f5) The prize, however, must surely go to Lady Carlisle who, when her husband made his public entry into Moscow in 1663, accompanied him in her own carriage trimmed with crimson velvet, followed by no fewer than 200 sledges loaded with baggage.

When Elizabeth Blanckley’s family travelled to Algiers, where her father was to take up his post as consul, they chanced upon Nelson and his fleet in the middle of the Mediterranean. ‘Good God, it must be Mr Blanckley,’

(#ulink_f08332a6-40e0-50ff-8538-c9398cf34c8a) Nelson is reputed to have exclaimed when he saw their little boat, all decked out ‘in gala appearance’ with flags of different nations. ‘How, my dear Sir, could you in such weather trust yourself in such a nutshell?… But I will not say one word more, until you tell me what I shall send Mrs Blanckley for her supper.’

My father assured him that she was amply provided for [recalled Elizabeth Blanckley in her memoirs] and enumerated all the live stock we had on board, and among other things, a pair of English coach-horses which, to our no trifling inconvenience, he had embarked, and stowed on board. Nelson laughed heartily at the enumeration of all my father’s retinue, exclaiming, ‘A perfect Noah’s ark, my dear sir! – A perfect Noah’s ark.’

(#litres_trial_promo)

Even the most determinedly rugged travellers, such as Isabel and Richard Burton, whose highly idiosyncratic approach to diplomatic life broke almost every other rule, travelled with prodigious quantities of luggage. On Isabel’s first journey to Santos in Brazil, where Richard was appointed consul, she took fifty-nine trunks with her, and a pair of iron bedsteads. It is hard to imagine anyone further from Major Leigh Hunt’s fanciful picture of the swooning and feather-brained female abroad than Isabel Burton. This was the woman who, when she learnt that she was to be Richard Burton’s wife, sought out a celebrated fencer in London and demanded that he teach her. ‘“What for?” he asked, bewildered by the sight of Isabel, her crinoline tucked up, lunging and riposting with savage concentration. “So that I can defend Richard when he is attacked,” was the reply.’

(#litres_trial_promo) Carrying out the order issued by her husband when he was finally dismissed from his posting in Damascus – the famous telegram bade her simply ‘PAY, PACK AND FOLLOW’ – was really a life’s work in itself. Although Richard was little short of god-like in Isabel’s eyes, when it came to the practicalities of their lives, she knew very well who was in control. ‘Husbands,’ she wrote, ‘… though they never see the petit détail going on … like to keep up the pleasant illusion that it is all done by magic.’

(#litres_trial_promo)

One wonders who was responsible for overseeing the household of Sir William and Lady Trumbull when they travelled to Paris in 1685. The vast body of correspondence describing Sir William’s embassy gives us almost no information about his wife other than that she had ‘agreeable conversation’ and once enjoyed ‘a little pot of baked meat’ sent to her by the wife of the Archbishop of York. We do know, however, the exact contents of her luggage. The Trumbull household consisted of forty people, including Lady Trumbull and her niece Deborah.

Besides a coach, a chaise, and 20 horses, there were 2 trunks full of plate, 9 boxes full of copper and pewter vessels, 50 boxes with pictures, mirrors, beds, tapestries, linen, cloth for liveries, and kitchen utensils, 7 or 8 dozen chairs and arm chairs, 20 boxes of tea, coffee, chocolate, wine, ale and other provisions; 4 large and 3 small cabinets, 6 trunks and 6 boxes with Sir William and Lady Trumbull’s apparel, and 40 boxes, trunks, bales, valises, portmanteaux, containing belongings of Sir William’s suite.

(#litres_trial_promo)

Handbooks for travellers, particularly in the late nineteenth century when the empire was at its height, were often aimed at readers who were going abroad, as diplomats were, to live for some time. They enumerated at length not only what to take for a two- or three-year sojourn, but also exactly how to take it. Major Leigh Hunt, perhaps because of his military background (Madras army), was very particular on the subject.

First there were the different types of trunk available. These include a ‘State Cabin Trunk’, made from wood with an iron bottom, for hot, dry climates; a ‘Dress Basket’, made of wicker, for damp climates; and a ‘Ladies Wicker Overland Trunk’, for overland travel (it was shallow, and could easily be stowed beneath the seat in a railway carriage). Then, of course, there was the ubiquitous travelling bath. One’s china, he advised, ‘should be packed, by a regular packer, in barrels’. Sewing machines were to go in a special wooden case; saddles in a special tin-lined case; paint brushes, he warned, should have their own properly closed boxes ‘or the hairs will be nibbled by insects’. Even a lady’s kid gloves, well-aired and then wrapped in several folds of white tissue paper, should be stored in special stoppered glass bottles.

Useful items of personal apparel include ‘several full-sized silk gossamer veils to wear with your topee’ and ‘a most liberal supply of tulle, net, lace, ruffles, frillings, white and coloured collars and cuffs, artificial flowers and ribbons’. Furthermore ‘pretty little wool wraps to throw over the head, and an opera cloak, are requisites which should not be overlooked’. Among essential household items the major lists mosquito curtains, punkahs, umbrellas and goggles; when travelling by sea, a lounge chair; drawing materials, wool and silks for ‘fancy work’; a water filter, lamps, a knife-cleaning machine; and no fewer than half a dozen pairs of lace curtains. Other recommended sundries include:

a refrigerator

a mincing machine

a coffee mill

a few squares of linoleum

cement for mending china and glass

Keatings insect powder

one or two pretty washstand wall-protectors

a comb and brush tray

bats, net and balls for lawn tennis

one or two table games

a small chest of tools including a glue pot

a small box of garden seeds

a small garden syringe

chess and backgammon

a few packs of playing cards

a Tiffin basket

Tropical Trials was, thankfully, by no means the only handbook of its kind to which a woman planning a life abroad could turn. Flora Annie Steel’s celebrated book The Complete Indian Housekeeper and Cook, first printed in 1888, was so popular in its day that it ran to ten editions. Although it was dedicated ‘To the English girls to whom fate may assign the task of being house-mothers in Our Eastern Empire’, its sound good sense and truly prodigious range of recondite advice – from how to deal with snake bite (‘if the snake is known to be deadly, amputate the finger or toe at the next joint …’) to how to cure ‘bumble foot’ in chickens – made it just as useful to diplomatic women living outside the empire.

Unlike the major, Annie Steel had no time at all for fripperies.

(#ulink_4b1bf608-1d2a-5f6f-a0cb-5586f79988fc) ‘As to clothing, a woman who wishes to live up to the climate must dress down to it,’ was her sensible advice. Frills, furbelows, ribbons and laces were quite unnecessary, she believed. None the less, the clothing which even she considered essential would have taken up an enormous amount of trunk space. ‘Never, even in the wilds, exist without one civilized evening and morning dress,’ she urged, and listed:

6 warm nightgowns

6 nightgowns (silk or thin wool) for hot weather

2 winter morning dresses

2 winter afternoon dresses

2 winter tennis dresses

evening dresses

6 summer tea gowns

(#ulink_6f1b25f9-5574-5239-94c2-5a3ca1922054)

4 summer tennis gowns

2 summer afternoon gowns

1 riding habit, with light jacket

1 Ulster

(#ulink_6a20e519-5b79-5788-8244-f6224bd5eac7)

1 Handsome wrap

1 umbrella

2 sunshades

1 evening wrap

1 Mackintosh

2 prs walking shoes

2 prs walking boots

2 prs tennis shoes

evening shoes

4 prs of house shoes

2 prs strong house shoes

(#litres_trial_promo)

On the actual journey, however, circumstances were often rather more frugal than these preparations suggest. When Diana Shipton travelled to Kashgar it was so cold in the mountains that she and her husband put on every garment they possessed and did not take them off again for three weeks. On one of her journeys in Brazil Isabel Burton once went for three months without changing her clothes at all. Sometimes, though, such spartan conditions were imposed more by accident than by design. When Angela Caccia, her husband David and their newborn son were posted to Bolivia in 1963 they made the journey by sea, taking with them an enormous supply of consumer goods, from tomato ketchup to soap powder. This luggage came with them as far as Barcelona, where it was lost, leaving them to face the six-week ocean voyage with little more than the clothes they were wearing. For the baby they did have clothes, but no food; ‘David had 75 ties; I had 9 hats, and between us we had 240 stiff white paper envelopes.’

However, the journey itself was so entrancing that the Caccias soon forgot these inconveniences. Their route took them through the Panama Canal and then down the Pacific coast of South America to the Chilean port of Antofagasta, from where they took a train across the Atacama and up into the Andes. Angela was spellbound by the beauty of the desert, despite the fact that the air was so thin and dry that their lips cracked and their hands hissed if they rubbed them together as if they would ignite. The light was so intense, she recorded, that they wore dark glasses even inside their carriage with the curtains drawn.

(#litres_trial_promo)

Very few diplomatic women were as experienced, or as naturally adept at travelling as Ella Sykes – or certainly not at first. The journey to a posting was often a woman’s first taste of travelling abroad, and it left an indelible impression on her – although not always the same sense of wonderment experienced by Angela Caccia. Reading back over my mother’s very first letters, written during the six-week sea voyage out to New Zealand in 1959, I find, to my surprise (for I have always known her as the most practised of travellers), a note of apprehension in her tone.

I suppose quite shortly we shall really be at sea [she writes from her cabin aboard the S.S. Athenic]. Atlantic rollers may begin, instead of the millpond the Channel has been up to now. We have been sailing in dense fog all day. It is a queer sensation to have thick mist swirling around with visibility about the length of the boat, the foghorn sounding every few minutes and bright sun shining down from above. We seem to be travelling at a snail’s pace.

It is also a surprise to be reminded that even then such a voyage was still considered a special undertaking. My parents arrived at the London docks to find themselves inundated with well-wishers.

We were taken straight to our cabin and found a large box of flowers from Auntie Olive, also from Betty and Riki, and telegrams from Hilary and Tony, J’s mother, Auntie Jo and Jack, Sylvia Gardener, and Richard Hickman. After the ship sailed at eight o’clock last night I found Mummy’s wonderful boxes of Harrod’s fudge and chocolates, and Hilary’s [my mother’s sister] stockings. Thank you so much both of you. It was all the nicer getting them then, after we had left the dock and were feeling a bit deflated. Thank you Mummy and Daddy also for the beautiful earrings, which J produced after dinner … I wonder if you realised how much I wanted something just like them?

There was no such send off for Isabel Burton when she took to the seas on her first posting in 1865. In her hotel room in Lisbon, where she stayed en route to Brazil, she was greeted by three-inch cockroaches. Although she could not know it then, it was only a taste of what was to come. ‘I suppose you think you look very pretty standing on that chair and howling at those innocent creatures,’ was Richard’s characteristically caustic response. Isabel reflected for a while, realized that he was right, and started bashing them instead with her shoe. In two hours, she recorded, she had a bag of ninety-seven.

For some women, the journey was the only enjoyable part of diplomatic life. The writer Vita Sackville-West loathed almost every aspect of it (the word ‘hostess’, she used to say, made her shiver), but her first impressions of Persia, recorded when she travelled there to join her husband, Harold Nicolson, in 1926, echoes the experience of many of these peripatetic wives. On crossing the border she wrote:

I discovered then that not one of the various intelligent people I had spoken with in England had been able to tell me anything about Persia at all, the truth being, I suppose, that different persons observe different things, and attribute to them a different degree of importance. Such a diversity of information I should not have resented; but here I was obliged to recognise that they had told me simply nothing. No one, for instance, had mentioned the beauty of the country, though they had dwelt at length, and with much exaggeration, on the discomforts of the way.

The land once roamed by the armies of Alexander and Darius had, to Vita’s romantic imagination, a kind of historical glamour that its contemporary inhabitants never quite equalled. It was ‘a savage, desolating country’, but one that filled her with extraordinary elation. ‘I had never seen anything that pleased me so well as these Persian uplands, with their enormous views, clear light, and rocky grandeur. This was, in detail, in actuality, the region labelled “Persia” on the maps.’ With the warm body of her dog pressed against her, and the pungent smell of sheepskin in her nostrils, Vita sat beside her chauffeur in the front seat of the motor car with her eyes fixed in rapt attention on the unfolding horizon. ‘This question of horizon,’ she wrote musingly later, ‘how important it is; how it alters the shape of the mind; how it expresses, essentially, one’s ultimate sense of a country! That is what can never be told in words: the exact size, proportion, contour; the new standard to which the mind must adjust itself.’

(#litres_trial_promo)

On that journey, she believed, Persia had in some way entered her very soul. ‘Now I shall not tell you about Persia, and nothing of its space, colour and beauty, which you must take for granted – ’ she wrote to Virginia Woolf on her arrival in Tehran in March 1926, ‘but please do take it for granted, because it has become part of me, – grafted on to me, leaving me permanently enriched.’ But the exact quality of this enrichment even she found hard to put her finger on. ‘But all this, as you say, gives no idea at all. How is it that one can never communicate? Only imaginary things can be communicated, like ideas, or the world of a novel; but not real experience … I should like to see you faced with the task of communicating Persia.’

(#litres_trial_promo)

Such difficulties, however, were as nothing compared to the difficulties and hardships often involved in the actual travelling itself. When Mary Fraser set off from Venice to make the journey to Peking in 1874 she was unprepared for the rigours of her first diplomatic journey, even though, having lived in Italy and America, she was relatively well travelled for a young woman. At first all was well, even though she could not help noticing the strange smell on board their boat: ‘the abominable, acrid, all-pervading smell of the opium cargo it was carrying’. By the time they reached Hong Kong, however, they had other worries: the worst typhoon in fifty years had all but destroyed the little island.

The P & O agent who came to meet their boat, ‘ashy pale and still trembling in every limb’, described how the storm had literally ripped apart the island in less than two hours. All shipping vessels had been wrecked, half the buildings ruined and not a single tree had been left standing in the Botanical Gardens. Worse than all this, though, was the fate of Hong Kong’s coolies and their families who had been living in sampans in the harbour – an estimated 10,000 had been drowned. By the time the Frasers arrived the water in the harbour was awash with the floating bodies of men, women and children. As she disembarked, Mary accidentally stepped on one of them and thereafter, ‘I could not be left alone for a moment without feeling faint and sick.’ In the tropical heat the corpses were already beginning to putrefy. Pestilence was all around and the atmosphere, she recalled with horror, ‘was that of a vast charnel house’.

The Frasers then travelled on to Shanghai without incident, and Mary recovered her composure enough to enjoy the rest of the journey, even the final stretch up the Pei-Ho river, although at first she surveyed the preparations with dismay. For the five-day river journey they had a fleet of five boats, each with five boatmen. Three of these carried their luggage; one was a kitchen and store room; while the fifth was fitted up snugly as a sleeping room and dining room. At night the boatmen pulled up the boards on the deck of their boat and, packed ‘like sardines in a tin’, they fitted the boards back tightly over themselves and slept peacefully. On the Frasers’ boat there was a little deck at the front with two chairs and ‘a tiny caboose sunk aft’, where a mattress could be laid on the floor at night. By day it was replaced by a table. ‘In the morning,’ Mary recalled, ‘poor Hugh used to hurry into his clothes, and go on shore for a walk, while I attempted to make my toilet, in all but darkness, with the help of one tin basin, muddy river water, and a hand glass.’

Although, unlike her husband, she was quite unused to these primitive travelling arrangements – ‘the Frasers’, she once commented, ‘are all Spartans’ – Mary was quick to learn a certain diplomatic stoicism. For most of the five days they spent on the Pei-Ho their servant, Chien-Tai, cooked ‘with marvellous success’ amidst her trousseau trunks in the kitchen boat and ‘not a course that we would have had on shore was omitted’; but on one terrible occasion, amidst torrential rain, the boats became separated and they had nothing to eat for a whole day. The two of them passed the day gloomily in the blacked-out caboose, lighted only by two meagre candles.

(#litres_trial_promo)

On her journey to Constantinople in 1716 Lady Mary Wortley Montagu, together with her husband and infant son, faced still greater hardships. On the mountain roads between Bohemia and Saxony she was so frightened by the sheer precipices that when she finally arrived in Dresden she could not compose herself to write at all. Their journey was all the more dangerous because they travelled at night, with only the moon to light their way.

In many places the road is so narrow that I could not discern an inch of space between the wheels and the precipice [she wrote to her sister Lady Mar]. Yet I was so good a wife not to wake Mr Wortley, who was fast asleep by my side, to make him share in my fears, since the danger was unavoidable, till I perceived, by the bright light of the moon, our postilions nodding on horseback while the horses were on a full gallop, and I thought it very convenient to call out to desire them to look where they were going.

As they travelled further south the danger of mountain precipices was replaced by another less dramatic but no less real peril: the weather. From Vienna Lady Mary wrote again to her sister on the eve of their journey through Hungary. It was January, and the entire country was so frozen by ‘excessive cold and deep snows’ that her courage almost failed her. ‘The ladies of my acquaintance have so much goodness for me, they cry whenever they see me since I have determined to undertake this journey; and, indeed, I am not very easy when I reflect on what I am going to suffer.’ Lady Mary’s usually sanguine tone begins to waver a little at this point; but when no less a person than Prince Eugene of Savoy, the Austrian general, advises her against the journey she begins to sound genuinely frightened.

Almost everybody I see frights me with some new difficulty. Prince Eugene has been so good as to say all the things he could to persuade me to stay till the Danube is thawed, that I may have the convenience of going by water, assuring me that the houses in Hungary are such as are no defence against the weather, and that I shall be obliged to travel three or four days between Buda and Essek without finding any house at all, through desert plains covered with snow, where the cold is so violent many have been killed by it. I own these terrors have made a very deep impression on my mind, because I believe he tells me things truly as they are, and nobody can be better informed of them.

She ends her letter, ‘Adieu, my dear sister. If I survive my journey, you shall hear from me again.’ And then, in an uncharacteristically maternal aside: ‘I can say with great truth, in the words of Moneses, I have long learnt to hold myself as nothing, but when I think of the fatigue my poor infant must suffer, I have all a mother’s fondness in my eyes, and all her tender passions in my heart.’

As it turned out, Lady Mary’s fears were not realized and the Wortley Montagus survived their journey. Although the snows were deep, they were favoured with unusually fine weather, and with their carriages fixed upon ‘traineaus’ (‘by far the most agreeable manner of travelling post’) they made swift progress. What they saw on the frozen Hungarian plains, however, shocked even their robust eighteenth-century sensibilities. Lady Mary recorded her impressions of the fields of Karlowitz, where Prince Eugene had won his last great victory over the Turks, in a letter to her friend, the poet Alexander Pope:

The marks of that glorious bloody day are yet recent, the field being strewed with the skulls and carcasses of unburied men, horses and camels. I could not look without horror on such numbers of mangled human bodies, and reflect on the injustice of war that makes murder not only necessary but meritorious. Nothing seems to me a plainer proof of the irrationality of mankind, whatever fine claims we pretend to reason, than the rage with which they contest for a small spot of ground, when such vast parts of fruitful earth lie quite uninhabited.

(#litres_trial_promo)

But, as Lady Mary had found, the ‘tender passions’ provoked by the additional stress of travelling with small children were often difficult to bear. Catherine Macartney, yet another diplomatic wife to find herself posted to the wilds of Chinese Turkistan, describes the extraordinary precautions which she took to ensure the safety of her small son. Eric, her eldest child, was born in 1903 when the family was in Edinburgh on home leave, and was only five months old when they set off back to Kashgar. ‘It seemed a pretty risky thing to take so small a traveller on a journey like the one before us,’ Catherine wrote. Nonetheless, knowing what was ahead of them, she did all she could, almost from the day Eric was born, to prepare him for the journey. To harden him up she took him out in all weathers, and only ever gave him cold food (once they were in the Tien Shan Mountains she knew that it would be impossible to heat up bottles of milk). Eric apparently throve on it. Catherine described their travelling routine:

When we were in the mountains, his bottles for the day were prepared before starting the march, and carefully packed in a bag to be slung over a man’s back. As they needed no heating, he could be fed when the time came for his meals, and just wherever we happened to be. And the poor little chap had his meals in some funny places – cowsheds, in the shelter of a large rock, or anywhere where we could get out of the wind.

At night he slept in a large perambulator which they had carried along especially for the purpose. According to Catherine, ‘He stood the journey better than any of us.’

Five years later, in 1908, when the family went home on leave again, they were not so lucky. Eric was now five, his sister Sylvia two and a half. Flooding rivers had blocked the usual route through Osh, and instead the Macartneys decided to trek north over the Tien Shan, and then through the Russian province of Semiretchia, from whence they could reach the railway at Aris, just to the north of Tashkent. Catherine recorded it all in her diary. Despite her misgivings about travelling in the summer heats, she was overwhelmed by the beauty of the lakes and flower-filled meadows they passed through. The two children, who rode on pack ponies in front of two of the consulate servants, seemed to enjoy it too. It is not long, however, before a more anxious tone begins to colour her entries: ‘Thursday, July 23rd. We have beaten the record today and have done four stages, reaching Aulie-ata at about four o’clock this afternoon. Poor little Eric has been so ill all day with fever; but the travelling has not seemed to worry him much, for he has slept the most of the time in spite of the jolting. Our road has been across the grassy steppes and the dust was not so bad.’

The next day, to her relief, Eric was much better, and she was able to hope that it was just ‘a passing feverish attack’. Two days later it was clear that it was something much worse.

Sunday, July 26th. Today’s march has been done with the greatest difficulty, for the children have both been very unwell and can take no food whatever. They have not seemed themselves for some days, and today they have been downright ill. To make matters worse, I suddenly had an attack of fever come on, which decided us to stop at the end of our second stage at Beli-Voda. Eric and I had to go to bed, or rather to lie down on hard wooden sofas, and it was pitiable to see poor little Sylvia. She was so ill and miserable and yet wanted to run about the whole time, and seemed as though she could not rest. There was little peace for anyone, for we could only have the tiny inner room that was reserved for ladies, to ourselves. The whole afternoon travellers were arriving and having tea in the next room, talking and laughing and making a distracting noise. Happily we had the place to ourselves for the night. I am much better this evening, but the children seem to be getting steadily worse and we are becoming anxious about them.

The following day the two children were so ill that the Macartneys got up at dawn and made haste to the town of Chimkent, where they were told there was a doctor. The doctor advised them to stop travelling at once and, to Catherine’s relief, found rooms for them in an inn near his house.

It is delightfully cool and restful here, after the hot dusty roads [she wrote in a snatched moment] and a few days’ rest will, I hope, set us all up. The first thing we did was to give the children a warm bath, put them into clean clothes and get them to bed. They looked so utterly dirty and wretched when we arrived that I felt I must cry; and they were asleep as soon as they got between clean sheets … a sleep of exhaustion. Both of them have lost weight in the last few days.

It was the last entry she was to make for many weeks.

On 23 August Catherine finally resumed her journal.

Our two or three days here have lengthened into nearly a month, and a time of awful anxiety it has been. The children, instead of recovering in a few days, developed dysentery, and to add to our troubles Nurse took it too. For three weeks it was a fight for Eric’s life and several times we thought we would lose him. Sylvia, though bad enough, was not as desperately ill as Eric … My husband and I did all the nursing and during that time we neither of us had a single night’s rest, just snatching a few minutes sleep at odd times.

In spite of their rudimentary lodgings – two rooms so small that there was only space for the children’s and the nurse’s beds – they were comforted by the extraordinary kindness of the local people. The Russian doctor visited them sometimes as many as three or four times a day. And there were others, too, ‘who, simply hearing that we were strangers and in trouble, were most helpful in sending us goat’s milk, cake, fruit, and delicacies. It is when one is in such straits as we were that one discovers how many kind people there are in the world. But I never imagined that anyone could receive so much sympathy and practical help from perfect strangers as we did during that anxious month.’

(#litres_trial_promo)

The Macartneys had been on the road for more than 800 miles before they finally arrived, exhausted, in Aris. From here they were able to pick up the Tashkent – Moscow train, and travelled onwards, first to Moscow, and then to Berlin via Warsaw. Although Eric suffered several relapses during that time, the family arrived safely in Edinburgh, three long and painful months after they had set out.

Like Mary Wortley Montagu with her traineaus, and Mary Fraser with her fleet of Chinese river boats, diplomatic women over the centuries have been obliged to take what transport they could find. Yet another Mary – Mary Waddington, who travelled to Russia to the Tsar’s coronation in 1883 – had several luxuriously appointed private railway carriages at her disposal, but a diplomatic wife was just as likely to find herself transporting her family by camel, yak, horse, palanquin, coolie’s chair, house-boat, cattle-truck, tukt,

(#ulink_67befa61-8218-5933-8469-9992f619f3b3) sleigh or tarantass

(#ulink_ace948aa-01a8-59cd-9155-fcab2b3cfda5) as by more conventional methods.

Travelling to the most far-flung diplomatic posts has remained a logistical problem well into the present century. One diplomatic wife recalls her journey to Persia in 1930, with her husband and English nurse, her children Rachel, aged two, and Michael, aged nine months, and seventy pieces of luggage. The quickest route in those days was by train, through Russia, although it still took two weeks. There were no disposable nappies in those days, so the baby’s washed napkins had to be hung out on rails in the corridor to dry, and when it came to crossing the Caspian Sea both her husband and the nurse were so sick she had no one to help her at all. ‘I can still see my poor husband with Rachel on his lap, being sick, and she, infuriatingly cheerful, saying, “What’s Daddy doing that for?”’

In 1964 Ann Hibbert’s husband Reg was sent to Ulan Bator, the capital of Mongolia, to open the British embassy; she later flew out there on her own under very strange circumstances. It was at the height of the Cold War, and sometime in the middle of the night they came down to refuel on the Soviet – Mongolian border. Although Anne was allowed off the plane, the Russians went to some lengths to stop her from talking to the other passengers. ‘I was told that I was not to go with the others,’ she remembers. ‘I was separated from them, and taken into a room by myself and the stewardess, very kindly, said, “I have to lock you in. Would you like the key on the inside or the outside?” I said, “On the inside, if you don’t mind.” So I was locked up, while the plane was refuelled.’

Single women travelling on their own, even respectable married ones, have always been faced with special complications, as Sheila Whitney found when she went to China in 1966.

Ray said, ‘You need a rest, come out on the boat,’ which I did and it took me four and a half weeks – the slow boat to China. I didn’t particularly enjoy it because I was a woman on my own, and in 1966 if you were a woman on your own, and one man asks you to dance more than twice you were a scarlet woman. I went and sat on the Captain’s table and there was a young chap there, and he was engaged to somebody, so I said, ‘Oh well, we’re in the same boat. You’re being faithful to your fiancée, and I’m being faithful to my husband, perhaps we can, you know …’ I didn’t invite him to dance or anything. But, no, they all had to be in bed by half past ten. On the journey before they’d all been in trouble, apparently, and so they all had to be in bed by half past ten at night. All the ship’s officers. Anyway, that was that. I was sharing a cabin with a young eighteen-year-old girl, who was there with her parents, and I used to go out with her parents, because if I did anything else I was labelled. It was ghastly. I can’t tell you how ghastly it was. But it was very funny, too. So I didn’t have such a gay time as I thought I was going to have. You know, I was looking forward to it.

At the turn of the century a similar regard for propriety governed long sea voyages, although, if Lady Susan Townley is to be believed, the rules were slightly less strict then than they were in the 1960s.

(#ulink_ebfa5aa9-6f61-553e-939d-bb57ed74b93b) On her journey to Peking from Rome in 1900 she noted the popularity of parlour games, especially musical chairs, during which a convenient lurch of the ship could always be blamed when a ‘not unwilling Fräulein’ fell into the lap of a smart officer. ‘These fortunate incidents, resulted in several engagements before the end of the journey,’ she noted wryly. ‘No wonder the game was popular.’

(#litres_trial_promo)

A woman’s sex contributed to her difficulties on a voyage in many different ways. She was encumbered not only morally (especially if she was obliged to travel alone) by notions of ‘respectability’, but also physically, by the clothes she wore. Until the latter part of this century women’s fashions were a serious handicap on anything but the shortest and most straightforward of journeys. Even an exceptional traveller such as Ella Sykes, who relished the harshness of the road, must privately have cursed the inconvenience of her cumbersome long skirts.

Recalling her long diplomatic career, which began just after the war in 1948, Maureen Tweedy claims that she knew, even as a child, that she had been born into a man’s world. She was ‘only a girl’, and restricted, apart from her sex, by layers of underclothing. ‘Children today cannot imagine how my generation were restricted. Woollen combinations, a liberty bodice on which drawers, goffered and beribboned, were buttoned, a flannel petticoat with feather-stitched hem, and finally a white cambric one, flounced and also beribboned.’

(#litres_trial_promo)

For grown women, matters became even worse. The extensive clothing list suggested by the highly practical Flora Annie Steel was as nothing compared to the extraordinary number of garments which went underneath:

6 calico combinations

6 silk or wool combinations

6 calico or clackingette slip bodices

6 trimmed muslin bodices

12 pairs tan stockings

12 pairs Lisle thread stockings

6 strong white petticoats

6 trimmed petticoats

2 warm petticoats

4 flannel petticoats

36 pocket handkerchiefs

4 pairs of stays

4 fine calico trimmed combinations for evening

(#litres_trial_promo)

Any woman following Flora Annie Steel’s advice to the letter would therefore have made her journey with a total of seventy-four different items of underwear (not including the pocket handkerchiefs).

Mary Sheil would have been similarly restricted in 1849, when she made the three-and-a-half-month journey to Persia via Poland and Russian Turkistan. The introduction of the crinoline was still seven years off, but there were stays, combinations and yards of cumbersome petticoats to hamper her. A typical day-time outfit of the period, even for travelling, would have included long lace-trimmed drawers, a tightly laced bone corset supporting the bust with gussets, and a bodice or camisole over the top. In addition to these a woman would have worn a total of five different petticoats: two muslin petticoats, a starched white petticoat with three stiffly starched flounces, followed by a petticoat wadded to the knees and stiffened on the upper part with whalebone, followed by a plain flannel petticoat. Over these went her travelling dress.