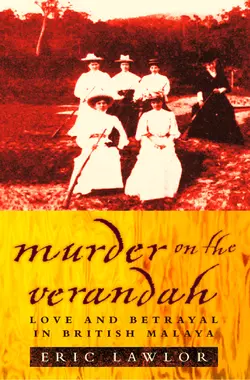

Murder on the Verandah: Love and Betrayal in British Malaya

Eric Lawlor

A Malayan White Mischief.‘On Sunday, 23 April 1911, Ethel Proudlock attended Mass at St Mary’s Church in Kuala Lumpur. She was well-liked at St Mary’s. She helped with jumble sales and had recently joined the choir. After Mass, the vicar’s wife invited her to lunch. But Mrs Proudlock declined. She had sewing to do. Then, taking her leave, she drove home and killed her lover.’In the sensational trial that followed Ethel Proudlock, the Eurasian wife of an Englishman claimed that William Steward, a mine manager, had tried to rape her, but the evidence pointed to a passionate affair, and a murder inspired by jealousy. Found guilty and sentenced to death, she walked free after being pardoned by the Sultan of Selangor, much against the wishes of British officials.The event scandalized polite society, and revealed the suffocating nature of expatriate life in Malaya, where the British ruled with an unhealthy blend of suburban aspiration and gross insensitivity to the native population. Petty, hypocritical and terribly unhappy, the British never counted Malaya as home and spent their time wishing they weren’t there. ‘Cheltenham on the Equator’ was rocked to its foundations by the dark, sordid nature of the trial.In this compelling work of social history Eric Lawlor examines Ethel Proudlock’s case for the first time since the trial, and creates a disturbing portrait of this little-known outpost of Empire.There are qualities of Somerset Maugham (The Letter was based on the Proudlock trial) and Conrad (Heart of Darkness) in Eric Lawlor’s book.

Murder on the Verandah

ERIC LAWLOR

Love and Betrayal in British Malaya

Copyright (#ulink_7c0147ca-502e-5f87-8bc0-49e65ba1d6a9)

Flamingo

An Imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers 1 London Bridge Street, London SE1 9GF

Flamingo is a registered trade mark of

HarperCollins Publishers Limited

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

Published by Flamingo 2000

First published in Great Britain by HarperCollins Publishers 1999

Copyright © Eric Lawlor 1999

The Author asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this ebook on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

HarperCollinsPublishers has made every reasonable effort to ensure that any picture content and written content in this ebook has been included or removed in accordance with the contractual and technological constraints in operation at the time of publication.

Source ISBN: 9780006550655

Ebook Edition © MARCH 2015 ISBN: 9780007525881

Version: 2015-03-26

Dedication (#ulink_1ee8d6bf-f7eb-565c-9fa3-113dd7ec4c3a)

For Gully

Epigraph (#ulink_9633590e-0181-5dd5-9b5d-49542a8a68ef)

‘Coelum non animum mutant qui trans mare currunt’

‘The sky, but not the heart, they change who speed across the sea’

FROM HORACE, TRANSLATED BY H. DARNLEY NAYLOR

Table of Contents

Cover (#u59acb446-a7af-5df3-a3a7-de7e07190aca)

Title Page (#ucfeac10d-516a-53f2-b755-78d8bc908075)

Copyright (#u8ec94258-4e9c-557b-b7f1-681cca427035)

Dedication (#ua8cc897f-70b6-527a-aef1-e6db1e68ffe2)

Epigraph (#u938ec98d-ef98-5f20-813c-0310c26af5ca)

Preface (#u95cffafe-e606-539b-81af-3a91f350b96e)

I TRIALS (#u9dcfdb80-1786-50f2-ac0d-82d1e2e25bb0)

1 ‘Blood, blood. I’ve shot a man’ (#u2e4bffe7-51b1-5d09-a401-953197da449d)

2 To Hang by the Neck Till She Be Dead (#ubedbc149-fb30-546a-89ad-5043bd8d8d10)

3 A Profound Sensation (#u5e073cf1-ee3c-5818-95ca-4ede86f0c167)

4 A Man on a Mission (#u73677a20-28fd-51ff-94bf-ae58b7f73330)

5 The Role of a Lifetime (#litres_trial_promo)

II ETHEL’S WORLD (#litres_trial_promo)

6 Foxtrots and Claret (#litres_trial_promo)

7 ‘Kippers Always in Stock’ (#litres_trial_promo)

8 Miss Aero and the Inimitable Denny (#litres_trial_promo)

9 The Queen in her Garden (#litres_trial_promo)

10 ‘Tragic Wives’ (#litres_trial_promo)

11 Rubber Fever (#litres_trial_promo)

12 The Imp of the Perverse (#litres_trial_promo)

13 A Tory Eden (#litres_trial_promo)

14 Against the Grain (#litres_trial_promo)

III HOME (#litres_trial_promo)

15 The Vanishing (#litres_trial_promo)

Index (#litres_trial_promo)

Acknowledgements (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

PREFACE (#ulink_6c38bf3d-a341-5271-bc86-a3ed84204c82)

On 23 April 1911, Ethel Proudlock, as was her custom on Sundays, attended Evensong at St Mary’s Church in Kuala Lumpur. She was well known at St Mary’s. From time to time she helped with jumble sales and had recently joined the choir. After the service, a friend invited Ethel to join her for dinner, but she declined. Her husband was going out for the evening, she said; it would give her a chance to write some letters. Then, after checking that the hymnals were in order, she walked home and killed her lover.

Claiming self-defence, she told police that William Steward had turned up unexpectedly that evening and tried to rape her. None of this was true. Steward was there because Mrs Proudlock had invited him, and he died – shot five times at point-blank range – after telling her he was ending their affair.

The Proudlock case, the basis of ‘The Letter’, the most famous of Somerset Maugham’s short stories, galvanized British Malaya. Some Britons insisted she was innocent, but the evidence against her was overwhelming and, after a trial lasting nearly a week, Ethel Proudlock was convicted of first-degree murder and sentenced to die. Preparations to hang her were well advanced when the Sultan of Selangor intervened. Citing her youth and the fact that she was a mother, he granted her a pardon. But the trial had unhinged her. Ordered to leave Malaya, Mrs Proudlock, with her husband and three-year-old daughter, returned to England a virtual invalid.

Until she was arrested, there was little to distinguish Ethel Proudlock from other members of the British community. Like them she was middle-class, seemed perfectly conventional and, to all appearances, was happily married. Ethel Proudlock fitted in, her defenders said. She couldn’t possibly be a killer; she was one of them. But the fact remained: Ethel Proudlock had killed. Why?

Some suggested that she might be mad. Mrs Proudlock was dangerously unstable, they said; a person whose violent mood-swings had long been the subject of gossip. Others blamed vindictiveness. Ethel made a bad enemy, according to this view. Offend her even slightly, and she was implacable. A third group – this one made up of Kuala Lumpur’s Chinese and Malays – attributed the killing to arrogance. Ethel was a member of Malay’s ruling caste and, as such, thought she could do as she pleased. When she pulled the trigger that night, she was exercising the prerogatives she believed were hers by virtue of her station.

There is a fourth, more plausible, possibility. When Ethel married, she was a girl of just nineteen whose sheltered background can hardly have prepared her for the pressures and artificialities of colonial life. Might it be the case that those pressures proved too much for her? Answering that question necessarily raises others. What were the British in Malaya really like? How did they comport themselves? Did they enjoy the country? What did they see as their role there? Were they, as some have claimed, a force for good? Or were they opportunists?

Colonial Malaya, often described as ‘Cheltenham on the equator’, has not lacked for study. Its politics have come in for much attention, as have its economics, but about the British themselves we know surprisingly little. The oversight is regrettable. While the society they created was neither as complex as India’s or nearly as grand, it was no less intriguing. No one clung more tenaciously to their ancestral ways than did the British in Malaya; and no one was more convinced of their natural superiority. The institutions they created in that country may well have been unique.

Complicating any effort to take the measure of these people is a controversy set in motion some seventy years ago by Somerset Maugham. Maugham is as much associated with Malaya as Kipling is with the British Raj but, unlike Kipling, who was born in India and spent much of his life there, Maugham visited Malaya only twice: for six months in 1921 and a further four in 1925–26. Yet out of that short acquaintance came his most enduring achievement – a group of short stories bringing Malaya so vividly to life that people named it Maugham Country.

Maugham’s portrait of Malaya’s colonials is less than flattering. The planters and officials in his stories are dull and mediocre, ‘eaten up with envy of one another and devoured by spite’. Their wives are even worse: ‘The women, poor things, were obsessed by petty rivalries. They made a circle that was more provincial than any in the smallest town in England … They were sheep.’

Cyril Connolly said of Maugham that he had done something never before achieved: ‘He tells us exactly what the British in the Far East are like.’ The British in Malaya did not agree. They said they’d been betrayed. They had taken Maugham into their homes, introduced him to their friends, made him a guest at their clubs. And for this, he had defamed them. Who are we to believe? This book is an attempt to answer that question.

One thing can be said at the outset: the British changed when they went overseas – a change that was commented on again and again. As one visitor put it: ‘Two Englishmen, one here and one at home, might easily be men of different race, language, and religion so different is their outlook and behaviour.’

In so far as it is useful, I have tried to let these people speak for themselves. This is their story after all and it seems only right that I let them help me tell it. I also draw much on the Malay Mail. With few sources at my disposal, the Mail proved a godsend. Kuala Lumpur’s only daily newspaper during this period, it is remarkable not just for the quality of its writing, but also for its knowledge of those whom it was writing about. Recruited in England, the Mail’s editorial staff did not simply cover the British community, they formed part of it. They belonged to the same clubs, worshipped at the same church, played on the same rugby teams, shared the same beliefs. At a time when the British in KL (as Kuala Lumpur was colloquially known) numbered between seven and eight hundred, the people these journalists wrote about were, in many cases, known to them personally. I owe the Mail a debt of gratitude. Without it, my job would have been very difficult.

Before I begin, a little history. Britain, in the shape of the East India Company, acquired Penang in 1786, Malacca in 1795, and Singapore in 1819. Seven years later, the three territories were amalgamated for administrative purposes. Now called the Straits Settlements, they were ruled from India until 1867 when Penang, Malacca and Singapore became a crown colony and found themselves the responsibility of the Colonial Office.

Now the rest of Malaya beckoned. Uncharacteristically, Britain hesitated – but not out of any high-mindedness. Its reasons were practical: Westminster did not care to become embroiled in Malaya’s Byzantine politics. Besides, as long as London controlled the Straits of Malacca – crucial if it were to protect India and safeguard its trade with China – it had little need of Malaya. For years, investors in the Straits Settlements had complained to Britain that it was failing to protect their interests. They had invested large sums of money in Malaya’s tin mines, they said – money that the interminable political squabbling in that country now placed at risk. Britain ignored them.

Then the money men changed tack. If Britain would not protect them, London was warned, they would find a country that would. (Germany and Russia were mentioned as likely possibilities.) London was all ears now. The last thing it wanted was a rival in a part of the world it considered its own. And so, in 1874, the government reversed its policy, making protectorates of Perak, Selangor, Sungei Ujong (part of Negri Sembilan) and Pahang, four territories that became the Federated Malay States (FMS) in 1896. Thirteen years later, Britain extended its rule again, this time to embrace the four northern states of Kelantan, Trengganu, Kedah and Perlis, long controlled by Siam. When the lone hold-out – Johore – submitted to British rule in 1914, Britain controlled the Malay peninsula as far north as the Siamese border, an area measuring 70,000 square miles. (The five newcomers declined to join the FMS and were known collectively as the Unfederated Malay States.)

In Malaya, the British employed a formula known as indirect rule, recruiting pliant elites – in this case the sultans – who became, in effect, front-men for colonial rule. The fiction put about was that the sultans, Malaya’s traditional rulers, enjoyed considerable discretion, turning to the British only when they needed help. Each state had a Resident – a senior civil servant – who was said to ‘advise’ the sultan. But no one was in any doubt as to what would happen if that advice were ever disregarded. Essentially, the sultans had a choice: they could do as they were told or be replaced by someone who would.

Because the country was never formally annexed, the British in Malaya convinced themselves that their rule owed nothing to force. This was far from being the case. True, force was rarely used, but no one in Malaya ever doubted it remained an option. When, in 1875, Malays assassinated the first Resident of Perak, the British mounted a punitive expedition that left scores of people dead.

Finally, a few words of explanation. During the period 1900 to 1910, my primary focus in this book, there were three ethnic groups in Malaya: Malays, Chinese and Indians. When referring to all three, I use the term ‘Asians’. The term ‘Malaya’ needs explaining as well. When Mrs Proudlock went on trial in 1911, Malaya comprised the Federated States, the Unfederated States and the Straits Settlements. As a single political entity, Malaya did not as yet exist. The term is convenient, however, and, as others have done, I use it here to mean that part of the Malay peninsula under British rule.

The dollar I mention from time to time is the Straits dollar which, during this period, was worth slightly less than half a crown.

I (#ulink_d4b4980d-6c9b-5ec2-81de-698e722ee376)

1 (#ulink_35cad0fd-5f35-5df3-a753-beee9832be45)

‘Blood, blood. I’ve shot a man’ (#ulink_35cad0fd-5f35-5df3-a753-beee9832be45)

When she returned to her bungalow that Sunday evening, Mrs Proudlock changed from the pink dress with black spots she had worn to church to a pale-green, sleeveless tea gown with a revealing neckline. An odd choice, perhaps, for an evening of letter-writing. She chose the garment, she said later, not because it showed her to good effect, but because it was pleasantly cool. Thus arrayed, she checked to see that her daughter was sleeping (she was), fetched a blotter and an ink-stand and set to work on her correspondence.

She and her husband, William, had moved into this bungalow the previous January. Surrounded on three sides by the Klang river, it stood in the grounds of the Victoria Institution (VI), Kuala Lumpur’s premier school. Normally, B. E. Shaw, VI’s headmaster, lived here but, four months earlier, Shaw and his family had gone to England on leave. In his absence, Proudlock had been named acting headmaster, which entitled him to use Shaw’s house until the latter returned in October.

It was an attractive bungalow. Though it no longer exists – it was demolished when the Klang river, prone to flooding, was rerouted in the late 1920s – Richard Sidney, who succeeded Shaw in 1922, described it in British Malaya Today as made of wood and mounted on brick piles ‘which get higher as the ground slopes towards the river – ordinarily some 30 yards distant’. The house had its own tennis court and was fairly large, he went on. It ‘has rooms bounded by wide verandahs’. The verandah on which Mrs Proudlock wrote her letters that evening contained several of her potted plants, but most of the other furnishings belonged to Mrs Shaw: a rectangular table and some chairs arranged on a square of carpet; a long bookshelf below which was a teapoy; and a large rattan chair bearing some of Ethel’s cushions. Light was provided by a single bulb suspended from the ceiling.

The bungalow faced High Street, normally one of Kuala Lumpur’s busiest, but this being a Sunday, it was quiet. What sounds there were were muffled by rain. It had been drizzling much of the day and now, as darkness fell, there was a cloudburst, the rain falling so hard that it obscured the 5-foot-high perimeter hedge that divided the school grounds from the street.

Mrs Proudlock was halfway through her second letter when a rickshaw bearing Steward drew up. Less than half an hour later, he was dead. According to Mrs Proudlock’s version of events, she was not expecting visitors that evening and had been startled by his arrival. Assuming that Steward had come to see her husband, she informed him that Will was having dinner with a colleague who lived on Brickfields Road, a mile and a half away. If Steward wished, she said, he could see him there. When Steward showed himself reluctant to leave, she suggested he sit down. They made small-talk, she said, discussing the rain and its impact on the rising river. For something to say, Mrs Proudlock mentioned religion, asking Steward if he had been to church that evening. He explained that he attended church very rarely. ‘Then you’re like my husband,’ she said, smiling. ‘I’ll show you a book he’s reading.’ She walked to the bookshelf and took down a copy of Leslie Stephen’s An Agnostic’s Apology. She was handing it to Steward when he tried to kiss her. She pushed him away. ‘What are you doing?’ she said. ‘Are you mad?’

Steward answered by grabbing her right wrist and, with his left hand, turned off the light. Frightened now, she tried to break free – and couldn’t. When Steward began to raise her dress, she seized his hand and wrenched it away. ‘He pulled me towards him,’ Mrs Proudlock said. ‘He had one arm around my waist and the other on my left shoulder.’

Steward now tried to force her against the wall and, afraid that she might fall, Mrs Proudlock reached out to steady herself. That is when her hand came in contact with a revolver, belonging to her husband, lying on the table.

‘I think I must have fired twice then,’ she said. Terror had made her mind go blank, she explained, and she couldn’t be more precise. ‘The next thing I remember I was stumbling. I think it was on the steps [of the verandah], but I’m not sure.’

The shots, striking Steward in the neck and chest, were heard by the rickshaw puller whom Steward had told to wait on High Street. Thinking that help might be needed, the puller was approaching the house, he later told the police, when the door burst open and Steward stumbled down the steps and lurched in his direction. Steward was clutching his chest. Fearing for his own life, the puller fled and had made it as far as the street when three more shots rang out. Glancing back, he saw Ethel Proudlock, gun in hand and still wearing her pale-green tea-gown, standing over Steward’s body.

Mrs Proudlock, who claimed to be in a state of shock, said she did not recall following Steward out of the house, nor did she recall shooting him three times in the head while he lay, clinging to life, on the rain-soaked ground. She said it was several minutes before she came to her senses. That was when she called to her cook, who was resting in his room, and ordered him to fetch her husband.

When Proudlock, accompanied by Goodman Ambler, a teaching colleague and the man with whom he had just had dinner, arrived fifteen minutes later, his wife staggered towards him, moaning: ‘Blood, blood. I’ve shot a man.’

‘Whom?’ he demanded.

‘Mr Steward,’ she said.

‘Where is he?’

‘He ran, he ran.’

Mrs Proudlock, her husband would later testify, was incoherent, her dress bore bloodstains, and her hair was in disarray.

When the police arrived, they found Steward, wearing a white suit, brown boots and a mackintosh, lying on his face in a pool of blood. The body was still warm, the Malay Mail reported next day, ‘and the frightful injuries were a testimony to the terrible execution of the Webley revolver … lying some distance away’. According to one police official, there was fresh blood on the Webley’s barrel, and Steward’s watch was still ticking.

The body was removed to the European Hospital in an ambulance cart. Horse-drawn and equipped with rubber tyres – in 1911, still something of a novelty – the cart would have been a tight squeeze for Steward. Just a few months earlier, the Mail had denounced it as absurdly inadequate. It was so short, the paper said, that to accommodate taller patients the back door had to be left open. As if being murdered was not enough, Steward suffered the added indignity of travelling to hospital with his feet protruding.

* * *

Next day the Mail reported that the decapitated body of a Tamil had been found near the Convent of the Holy Infant Jesus and that a Chinese man had drowned himself after stabbing his wife. The paper’s English readers were unlikely to have paid either item much attention. The talking point that Monday, as it would be for weeks to come, was the story on page 5. Under the headline ‘Kuala Lumpur Tragedy; Former Mine Manager Shot Dead; A Distressing Story’, it began: ‘We regret to record a tragedy which created a profound sensation in Kuala Lumpur when the news became generally known this morning.’

Also that Monday, Mrs Proudlock, accompanied by her husband and still thought to be a woman who had killed to protect her honour, made a court appearance lasting all of three minutes. No evidence was presented, the court expressing the wish that she be spared as much embarrassment as possible. The proceedings ended with her being formally charged with causing William Steward’s death – a legal necessity since she herself admitted to killing him. Despite the gravity of the charge, the court took the unusual step of refusing to remand her in custody – no doubt also to spare her feelings – and Mrs Proudlock was released on the payment of two sureties to the amount of $1,000 provided by her father, Robert Charter. A further hearing was fixed for 1st May.

Steward’s funeral at 5.30 that Monday afternoon was a forlorn affair. An obituary in the Mail lauded him as an energetic miner and, more important in British eyes, an enthusiastic rugby player. But neither his energy nor his enthusiasm seem to have gained him much. A mere fifteen people attended his burial in the Venning Road cemetery, a short distance from Kuala Lumpur’s new railway station.

Until a year or two earlier, much ceremony had attended the burial of Britons. At the European Hospital, the coffin was placed on a hand bier and, under escort, was drawn to the cemetery by a detail of splendid-looking Sikh policemen. But in 1909, the police department, for reasons of economy, had ended the practice. Now the bier was drawn by the cemetery’s Javanese gardeners. A bit of a come-down, this; and not everyone was pleased. ‘In common with many other people,’ the Mail complained, ‘we feel the time has come when it should no longer be necessary to call upon Javanese gardeners or anyone else of an alien race or creed to draw the body of a deceased European along public roads to its last resting place.’

Steward’s funeral service was performed by the Revd P. Grahame, a man new to Kuala Lumpur and new as well to presiding over the burials of murder victims. One can imagine his difficulty when recording the event that night in St Mary’s register. Under the heading ‘Cause of Death’, Grahame settled finally for the words ‘bullet wounds’. Surrounded as they are by a long list of deaths due to more conventional causes – malaria, dysentery, convulsions and beri-beri – the words when I saw them in 1996 made my blood run cold.

Steward was a shy man and, beyond turning out for a rugby match once in a while, socialized little. He visited the Selangor Club from time to time and, while there, would sometimes share a drink with William Proudlock. He liked Proudlock as much as he had liked anyone, but for all that, he did not have many friends. In 1911, men in Kuala Lumpur spent a lot of time in one another’s company, partly because there were not many British women, and partly because, most having been to public schools, they enjoyed other men. Steward seems to have been different. For one thing, most of these men drank a lot; Steward was fairly abstentious. For another, in company, he was ill-at-ease. The bluster and heartiness in the Selangor Club’s Long Bar would not have been to his taste. Once in a while, Proudlock prevailed upon him to attend one of his musical ‘at homes’ but, as hard as he tried, he never succeeded in getting Steward to sing. While the others belted out ‘The Road to Mandalay’, Steward would sit silently and stare at his shoes.

No one seemed to know much about Steward. He was understood to have been living with a Chinese woman – true, it turned out; he was believed to be forty years old – false: he was closer to thirty-four; and he was thought to have come from somewhere in the British Midlands. In fact, he came from Whitehaven in Cumberland, where he had a mother and a sister with whom he corresponded several times a month. He also helped to support them and regularly sent them money – an income on which they had come to depend and would now greatly miss.

Instead of socializing, Steward seems to have immersed himself in his work. He was respected both as a mining engineer and as someone who did not call attention to himself. This makes his death especially ironic. A person who avoided the public gaze, he would have found the attention hugely embarrassing.

Salak South, the mine he ran until late 1910, prospered under his management. For the month of April that year, the mine produced 122 pikuls of dry ore, an excellent result for a place of its size. (A pikul is the equivalent of 133⅓ pounds.) The machinery – it was Steward’s job to keep it running – worked 594 hours and 35 minutes that month: virtually round the clock.

Kuala Lumpur was a small place then, and Salak South, though just five miles from the Proudlock bungalow, was considered remote. It received few visitors, in part because it was hard to reach and also because it was said to be unlucky. George Cumming, an early backer, invested a fortune in Salak South and lost every penny. People said the place was cursed, and there must have been times when Steward thought so, too. In 1909, production came to a standstill when the Klang river overflowed, flooding the mine and destroying a lot of expensive equipment. Then, just six months before his own death, one of his colleagues died. It happened quite without warning. ‘Mr D. Issacson returned to his bungalow at Salak South about 4 in the afternoon’, the Mail reported, ‘and sat down in a chair from which he never rose, death taking place about 5.30.’ The apparently healthy Issacson had suffered a heart attack. Salak South also claimed the lives of numerous labourers. Equipment was primitive. Methods were rudimentary. The great danger, at this mine as at many others, was cave-ins. They could happen in a moment, burying workers who, all too often, died of asphyxiation before frantic colleagues could dig them out.

When Steward and Proudlock chatted in the Selangor Club in December 1910 – the last time they would talk – the miner was looking for work. ‘The mine has gone phut,’ he said, meaning that the ore had run out. ‘I think I have got another post, but I am not sure yet.’ In January it was confirmed. Steward was now in the employ of F. W. Barker and Co., a firm of consulting engineers based in Singapore. Though he retained his house not far from the mine, Steward now took to the road, trouble-shooting for some of the largest mines and rubber estates in Selangor. It was a relief to be out of Salak South, he said. All that talk of a jinx had begun to prey on him.

Steward was a man who feared complications. He was methodical and thorough, a man who believed in keeping the record straight. Where details were concerned, he was almost fastidious. In October 1910, he wrote to the Mail alerting it to an error it had made: ‘In your issue of 28th inst., you publish the managing director’s report of the Sungei Raia tin mines and mention that the ground ran 15 catties per yard. Surely this is a mistake and probably should read 1.5 catties per yard. I merely point this out in defence of the management there as they might not see your paper. Yours, etc. W. Steward.’ It was a small matter, but none the less revealing, for this was a man to whom small things were important.

Aside from that letter, the Mail mentions him only rarely. Steward did not attend the annual ball to mark the King’s birthday, and he was never a guest at fashionable weddings, regarding such events as frivolous. He played rugby when work permitted – as much for the exercise as for any enjoyment, one suspects – and, once in a while, got in some tennis. In 1909, he entered a tennis tournament the Selangor Club had organized, but was knocked out in the first round. Rugby was another matter. Steward made a fierce opponent. Malaya had numerous rugby teams and, at one time or another, he seems to have played for most of them. His play was unrelenting, shaped, no doubt, by the great football games of Cumberland legend. Hugh Walpole described one in Rogue Herries (1930): ‘The goals were distant nearly half a mile the one from the other. There were few rules, if any; all cunning and trickery were at advantage, but brute force was the greatest power of all. There were fifty players a side to start with, although before the game ended there was nearly a hundred a side … So that now there was a grand and noble sight, this central mass of heaving men, detached groups of fighters, and the spectators shouting, roaring, the dogs barking as though they were mad.’

A picture of Steward shows him standing on a flight of steps leading to a house – his own, perhaps, in Salak South – and looking a little discomfited. Perhaps the camera has unnerved him. A tall, big-framed man, he is bald and wearing a collar and tie. William Steward, it would appear, liked formality. His right hand rests on his right hip – an attitude that in anyone else would suggest nonchalance but which here makes him look awkward. Knowing how shy he was, it is surprising that he posed for a picture at all, unless he intended to send it to his mother. He’d have done anything for her, even if it meant embarrassing himself.

He was serious, even grave, and threw himself into his work. Perhaps he saw it as redemptive. While it is impossible to say why he came to Malaya – whether to advance the country’s interests or his own – he was none the less a caring man, a man who provided for his widowed mother, a man aware of the duty he bore to others.

2 (#ulink_3ce7b09d-02d0-5183-af40-763480912ff3)

To Hang by the Neck Till She Be Dead (#ulink_3ce7b09d-02d0-5183-af40-763480912ff3)

The British in Malaya were still in a state of shock when Mrs Proudlock, still enjoying her freedom, appeared at a magistrate’s inquiry on 1st May. ‘The painful sensation which the [shooting] occasioned from one end of the country to the other has hardly diminished since the discovery of Mr Steward’s body,’ the Mail reported. By then, opinion had begun to change, many taking the view that Ethel was almost certainly guilty. When, looking considerably younger than her twentythree years, this ‘pretty, blonde-haired woman’ took her place at the bar, the room fell silent. One of their own – and female at that – standing in the dock! It proved too much for the magistrate who, his chivalry fired, sent for a chair and told the defendant that she might, if she wished, seat herself near the bench.

He was not the only one in court that day concerned for her comfort. Her lawyer, E. A. S. Wagner, also had her sensitivities in mind when he complained that most of those in the public gallery were Malays and Chinese – what the Mail called ‘the native element’.

‘There are a lot of persons in the court who have no business here,’ Wagner said, ‘and I think this would tend to affect the prisoner.’

As a person who knew the law, Wagner surely would have known that seeing justice done was everyone’s business. Clearly, the presence of non-Europeans made him uncomfortable for another reason: the realization that the trial of Ethel Proudlock had the potential to compromise British prestige. (Wagner was, incidentally, a curious choice to defend Mrs Proudlock. An able lawyer, he and Steward were friends, having often played rugby together. He also seems to have known that his client was guilty. When Somerset Maugham visited Malaya in 1921, it was Wagner who told him of the Proudlock case, even suggesting he write a story about it.)

The police wanted the public excluded, too, but for a different reason. The case involved ‘a certain amount of indecency’, the magistrate was told. The court was being warned that the evidence to be presented was likely to prove embarrassing, not just to Mrs Proudlock, but to the British generally, and the fewer ears it reached the better for all concerned.

Mr Hereford, the lawyer representing the police, opened the proceedings by summarizing ‘the facts in so far as we have been able to ascertain them’. On the night of 23 April, William Steward, he told the court, was dining with two friends in the Empire Hotel when, hearing the clock in the Secretariat building strike nine, he rose suddenly and asked to be excused. He had, he said, an appointment. Then, leaving the hotel in some haste, he flagged down a rickshaw and went directly to the home of the accused.

Besides Mrs Proudlock, the only person in the house when he got there was a cook. Her husband had gone out to dine, and both the ayah (nanny) and the ‘boy’ had the evening off. The cook said he was smoking opium in his room when he heard a man shout, ‘Hey! Hey!’ This was followed by gunshots, but he took little notice until he heard Mrs Proudlock, from somewhere in the garden and sounding much distressed, telling him to fetch her husband.

When Mr Proudlock returned, he found his wife ‘in a very agitated state’ and speaking in ‘a most unintelligible manner’. She told him that Steward had molested her and made improper proposals. There was gunpowder on her right hand, Hereford continued. ‘There is no question that it was she who shot the deceased.’

Hereford then challenged Ethel’s claim that Steward’s visit was unexpected: ‘The deceased stated that he had an appointment. This showed that he must have been aware that he would find the accused in the house by herself… It is difficult to see how he could have known this unless the accused had told him. At some point, there was some communication between them.’

He also challenged her claim that Steward had tried to rape her. When the police found Steward, he was fully dressed, and his trousers – what the Mail called ‘his nether garments’ – were buttoned. ‘The medical evidence did not show any accomplishment of violation.’ Nor was there evidence of a struggle. A teapoy had been overturned but, aside from that, nothing else had been disturbed.

‘This,’ he added ominously, ‘makes her story not very easy to believe.’

Continuing his attack on Mrs Proudlock’s probity, Hereford now turned to the matter of her attire. Though she was dining by herself, the accused wore an evening dress which, he had been told, ‘is cut very low’. According to her husband, Mrs Proudlock always dressed like this in the evenings, even when she dined alone. But Hereford was sceptical. Allowing that this was not beyond the realm of possibility, it was, he said, ‘a question which has to be considered as to whether it does not point to the expectation of a visit from the deceased’.

The evidence had begun to look damning and when the court rose that day, the magistrate, no longer feeling chivalrous, refused to grant an application for bail. For the first time since the shooting, Mrs Proudlock was deprived of her liberty and removed to Pudu gaol, a mile from the courtroom. But old habits die hard. To spare her the indignity of riding to prison in a police van, Detective-Inspector Wyatt drove her there himself in his private car.

It must have been an uncomfortable drive for both of them. What could they possibly have found to say to one another? Wyatt, in charge of the police investigation, could hardly have offered his sympathy. Like many in KL, he did not doubt she was a killer, but there were other obligations on him – obligations of gallantry and the respect due to one’s own. A solidarity existed between them – and would do so until such time as the court found her guilty.

Pudu gaol would be Mrs Proudlock’s home for the next two-and-a-half months. The prison, completed just six years earlier, covered an area of 7 acres and could accommodate as many as 600 prisoners. Separate from the main building was the female wing which comprised six cells, each containing a plank bed and a wooden pillow. When not locked up, women prisoners were allowed to congregate in a common room where they could knit or even do a little sewing. For their refreshment, the prison provided a pail of weak tea.

In September 1909, the Mail had run a long story about Pudu gaol, a story that Mrs Proudlock is almost certain to have read. As well as a daily rice ration, the Mail reported, each prisoner received meat or eggs and two kinds of vegetables. Meals were served twice a day – one at 10.15; the other at 4 – and porridge was provided in the early morning. Meals were taken in two large, open-sided sheds to the right of the prison proper. ‘All is scrupulously clean and neat,’ the story went on. ‘There is not a speck of dirt anywhere … In the cooking area, there is a marked absence of the somewhat unsavory smells which so often hover over Oriental culinary preparations.’

The regime as reported does not sound especially harsh but, that said, Mrs Proudlock cannot have found it very pleasant. Separated from her husband and her young daughter, she was alone, incarcerated, and facing an uncertain future. As she contemplated that plank bed and wooden pillow, one can imagine her terror.

On the stand the next day, William Proudlock told the court that, on 23 April, he and his wife took a nap after lunch, rose at 4, had tea on the verandah and then put in some target practice, using a revolver she had given him just five days earlier as a birthday present. At 5.25, he had handed the gun to Ethel and told her to put it ‘in a safe place’. Both of them then left for church, after which they briefly visited the Selangor Club and went home, where he changed clothes and left for his dinner appointment.

Asked if he and his wife were on good terms, Proudlock said, ‘Oh, yes.’

Had he ever had occasion to complain about her moral conduct?

‘No,’ he said.

What about her conduct in respect to other men: did he ever have cause to complain about that?

‘Never.’

Asked why his wife had given him a gun for his birthday, he said that their home in Brickfields Road – the one now occupied by Goodman Ambler – had been broken into the previous August, and they had talked several times since about buying a revolver.

On the day before the shooting, he said, his wife had run into Steward at the Selangor Club and had been forced to talk to him when, passing his chair, he had looked up at her and said hello. In the course of a short conversation, his wife had remarked on how long it was since Steward had been to see them and mentioned that she and her husband had moved to another house. When Steward asked where, she felt she had no choice but to tell him.

Proudlock said he had known Steward for almost two years and considered him a friend. ‘He’s always behaved as a gentleman towards my wife.’

Summoned home the night Steward died, he found his wife ‘in a state of disorder’. Her face was very white, and she was sobbing violently. ‘I saw at once that there had been a struggle of some description.’ The next day, he saw bruises on her shoulders and on her legs. (The prosecution claimed that these were self-inflicted. A doctor who examined Ethel on Sunday night had found no bruising at all.)

Goodman Ambler, described by Proudlock as ‘a great personal friend’, then took the stand, testifying that after dinner that Sunday evening he and Proudlock chatted and smoked, and then Will had played the piano, only stopping when the cook arrived.

Mrs Proudlock, when Ambler saw her, looked ‘very wild and excited’. Trembling violently, she then became hysterical and almost collapsed. Ambler remembered noticing that her dress was torn below the knee and near the waist. He and Proudlock helped her into the house where Ambler wrapped her in a shawl and her husband gave her a glass of sherry. Lying on a settee, ‘she kept half-rising and looking about her very wildly’. When Ambler tried to soothe her, she became angry and told him to shut up. Proudlock took his wife’s hand and said, ‘Tell us about it, Kiddie.’

As Mrs Proudlock described it, Ambler said, Steward got up when she went to get the book and kissed her saying, ‘You’re a lovely girl. I love you.’

‘She sternly remonstrated with him,’ Ambler continued, ‘and then shouted for the servants.’

Mrs Proudlock told him that after shooting Steward once, she then shot again. Steward ran from the verandah, and she followed. She remembered stumbling on the steps. And then her mind went blank. When she recovered herself, she was back in the house.

Steward, she said, had lifted her dress and ‘tried to spoil me’.

Asked to characterize Mrs Proudlock, Ambler described her as a quiet woman who took pride in her home. ‘She and her husband never quarrelled.’

Tan Ng Tee, the rickshaw puller, said he saw Mrs Proudlock – the ‘mem’ – follow Steward down the steps and stand over his prone body: ‘The man made a noise, “Ah.” Then he was quiet.’

Tan asked Ethel what had happened to Steward. ‘I asked twice,’ he said. ‘I got no answer. I ran away fast. When I neared the gate, I heard shots: pok, pok, pok. I was frightened. I kept on running.’

Near the body, the police discovered prints which later were found to match Mrs Proudlock’s shoes: black pumps with raised heels and two large buckles.

James McEwen, a friend of Steward’s, testified to seeing him in the Selangor Club that Sunday. He also saw the Proudlocks. He described Mrs Proudlock as wearing a black ‘picture’ hat. Asked if he had seen Steward and Mrs Proudlock exchange signals, McEwen said that he had not.

On Day 3 of the proceedings, Will Proudlock asked to take the stand again. He wished, he said, to amend his earlier statement that his wife wore an evening gown when she dined alone. He had meant to say that she wore an evening gown when the two of them – he and she – dined alone. It was a clarification that did nothing to help Ethel’s case; if anything, it reinforced suspicions that she had donned this garment only because she expected company.

In the event it hardly mattered. Dismissing Ethel’s claim that she had acted in self-defence, the magistrate closed the inquiry by reading the charge against her: ‘That on or about April 23, 1911, in Kuala Lumpur in Selangor, you did commit murder by causing the death by shooting of one William Crozier Steward and thereby committed an offence punishable under section 302 of the penal code.’ She was ordered to stand trial at the next assizes.

Mrs Proudlock cried and trembled as the charge was read, and it was some time before she could compose herself. Then, with some difficulty, she struggled from the dock and, her face stained with tears, left the court on her husband’s arm.

Mrs Proudlock would languish in Pudu gaol for almost six weeks before Kuala Lumpur next saw her. On 11 June she appeared in the Supreme Court where her trial opened before Mr Justice Sercombe Smith. Ethel was dressed in white and wore a hat whose veil concealed much of her face. According to the Mail, ‘she looked very pale as she took her place in the dock’. The public gallery was almost empty.

It is a little ironic that Mrs Proudlock, an aspiring thespian, had recently appeared to good reviews in an amateur production of Gilbert and Sullivan’s Trial by Jury, but would now enjoy no such privilege herself. Jury trials had been abolished in Malaya some years earlier, in large part because the pool of jurors, being confined to Britons – the only group thought capable of reaching judicious decisions – was necessarily small. Another reason for abolition had to do with a distrust of lawyers, most of whom were considered cynical and tendentious and all too likely to play on jurors’ emotions. Instead of trial by jury, Malaya employed the assessor system – later a source of much controversy. Under this arrangement, the defendant faced a triumvirate comprising a judge and two assistants. The judge interpreted the law, and the assistants, members of the public who in most cases had no legal training at all, assessed the evidence ‘in the cold light of reason’. And then all three voted, verdicts being determined by a simple majority.

During the six weeks since Ethel had last been seen in public, rumours had been circulating that she and Steward were lovers. This was mere conjecture, Sercombe Smith reminded his assessors that first morning. Steward had attended the musical ‘at homes’ Will Proudlock liked to organize and, like many others, sometimes ran into the Proudlocks at the Selangor Club. This in no way proved, he said, that Steward and Mrs Proudlock had been intimately involved.

Mrs Proudlock, Sercombe Smith went on, said she killed Steward in self-defence: ‘I was protecting my person as I am entitled to do.’ But had Steward really tried to rape her? That, too, had still to be proved, and the assessors’ decision in the matter would determine the case’s outcome.

The first to take the stand was the defendant’s husband who told the court that his marriage was a happy one. Ethel ‘was always very attentive and affectionate’. She had been nineteen when he married her in 1907. Her health had been bad, he said, and they left for England within hours of the wedding. On the journey home, she was attended several times by the ship’s doctor. Since her return to KL in November 1908, her health had been poor. ‘She’s always been very nervous and easily frightened.’

G. C. McGregor, one of Ethel’s doctors, then described her medical history in some detail – information which the Mail chose not to publish for reasons of propriety. (The details that follow were taken from a transcript of the trial sent to the Colonial Office.) Ethel had numerous problems, McGregor said: profuse leucorrhoea (an abnormal vaginal discharge), excessive and irregular menstruation, relaxed genitalia, a collapsed uterus and a tender ovary. There was more: the lips of her vulva were malformed, and her vagina contained large quantities of pus. McGregor had urged her to have an operation, but Mrs Proudlock, as he put it, ‘kept putting off the evil day’. Ethel, he finished, was a delicate girl who did not possess the strength of a normal person. When Steward confronted her, she became hysterical and had fired those shots, not to kill him, but to rid herself of an impending calamity.

Dr Edward MacIntyre, an assistant surgeon assigned to KL’s General Hospital and the man who examined Mrs Proudlock on the night of the murder, was asked if her eyes looked dazed. ‘Dazed’ didn’t seem the right word, he said; as he remembered them, they looked intelligent. He did not get the impression that the accused had just experienced a severe mental shock.

JUDGE: It has been stated that the accused struggled her hardest. In your opinion was the condition of the accused compatible with her having struggled her hardest?

MACINTYRE: No.

JUDGE: Compatible with any kind of struggle?

MACINTYRE: Yes.

Inspector Farrant, who searched Steward’s house in Salak South, said he found clothes belonging to a European female and a European child in Steward’s bedroom. It is not known if these belonged to Mrs Proudlock and her young daughter; the prosecution did not pursue the subject. The only letters in the house, Farrant said, were from the dead man’s mother and sister in Whitehaven.

While Farrant was searching the house, the court was told, a Chinese woman, presumably Steward’s lover, asked the policeman if he knew of Steward’s whereabouts. When told that he’d been murdered, she burst into tears. With the exception of members of his family, this woman may have been the only person to weep for Steward, the only person who actually cared about him. In the eyes of Ethel’s dwindling supporters, Steward’s association with a Chinese woman proved beyond all doubt the extent of his degeneracy. A moral man, a man of any character, didn’t do such things. If Steward was capable of sleeping with a Chinese, he was capable of anything. For such a person, raping a white woman was a very small step.

Recalled to the stand, Proudlock had to fight back tears when asked to describe his wife’s demeanour after she had retired that evening: ‘During the night, I saw her muttering something in what I thought was her sleep. I got out of bed. I put on the lights, and she was on her back with her eyes staring up. I said, “What is it, Kiddie?” She made no reply and turned over.’

‘What was the object of her putting on the gown?’ the judge wanted to know. ‘To look beautiful?’

‘No. To be cool.’

There were even fewer people in the public gallery when the case resumed next morning, but after lunch the court was full. The day was unusually hot, and a supporter had provided Mrs Proudlock with a paper fan.

For the trial’s fourth day, Mrs Proudlock, who was something of a clothes-horse, wore a white straw hat trimmed with brown ribbon. Whereas earlier she had seemed dazed and had taken little interest in the proceedings, she now chatted with her counsel before the judge arrived and then talked at length with her husband.

First to take the stand was Albert Reginald Mace, who had shared a house with Steward until March 1910.

JUDGE: He was not an immoral person?

MACE: No.

JUDGE: He was quite a moral man?

MACE: Yes.

Mace said he had never seen Steward intoxicated; he was a temperate man. The most he had ever seen him drink was two stengahs (whisky and soda) a day.

For the first time since the trial began, Mrs Proudlock now took the stand in her own defence. Speaking in a weak voice, she said she had known Steward for two years, during which time he had dined at her home on many occasions.

A day later, she seemed more in charge of herself, answering questions in a voice that no longer wavered. When she rose to fetch The Agnostic’s Apology, she told the court, Steward grabbed her and said, ‘Never mind the book. You look bonnie. I love you.’

Mrs Proudlock now broke down and, hiding her face in her hands, ‘wept bitterly’. She said it had been her intention to fire over Steward’s head. (Later she would say she didn’t know the gun was loaded.) She had not wanted to hurt Steward; her intention was only to frighten him.

‘Do you remember’, she was asked by Hastings Rhodes, the public prosecutor, ‘standing over the body of Mr Steward some seconds before firing?’

‘No.’

‘I suggest you fired three shots into Mr Steward’s body while he lay on the ground. You must have stood over the body anything from three to ten seconds before making up your mind to fire.’

Mrs Proudlock said she had no memory of standing anywhere. After firing that first shot on the verandah, she became oblivious.

Asked by Rhodes if she had visited Salak South when her husband was in Hong Kong for three weeks in 1909, she said she had not.

‘Do you remember spending a night at Salak South and having breakfast there in the morning?’

‘No.’

She did admit, however, that during her husband’s absence, Steward once visited her. But on that occasion, she said, there were several other people present. And, she added, the evening had been miserable. She denied that she and Steward had spent part of that evening alone together in a car. She said she and her guests had gone for a drive in the Lake Gardens, but she had been in one car and Steward in another.

The suggestion that she and Steward had been lovers seems to have upset Mrs Proudlock far more than the altogether more serious charge that she had killed him. Speaking through her counsel, she told the judge she would much rather be convicted of capital murder than leave the court bearing the taint of adultery.

Sercombe Smith, who during this trial seems to have thought of little but Mrs Proudlock’s low-cut gown, now intervened to ask if she were wearing ‘any underthing’ the night Steward died.

Mrs Proudlock answered that she was wearing a chemise and stockings.

‘Was it your custom to do so?’

‘Yes, whenever I wore an evening tea gown.’

Then she wasn’t wearing drawers?

‘It is my habit not to wear drawers when I wear a frock with thick lining.’

On 15 June, Dr McGregor took the stand again and testified that when he examined Mrs Proudlock on 24 April, her expression had been one of restrained terror. When he asked her how she felt, she said, ‘This is a horrible incident, and it’s not yet finished. It seems as if someone is gripping my brain. If it does not stop, I shall go mad.’

The last person to give evidence was Thomas Cooper, the doctor who performed Steward’s post-mortem. He found ‘no signs of recent sexual connection’, he said; ‘there were smegma on Steward’s prepuce, but no spermatozoa on the body.’ Cooper then undermined his value as a witness by claiming that, to rape a woman, a man would first have to render her unconscious. ‘Even though a man may overpower a woman and put her on the ground and be within an inch of accomplishing his purpose, the slightest movements of a woman’s buttocks would prevent his purpose being carried out.’

Summing up for the defence, J. G. T. Pooley described the Proudlocks as living ‘on the most harmonious terms’. The prosecutor, he said, claimed that Steward’s visit had been arranged. But where was the proof? It was possible, he conceded, that when Steward arrived at the bungalow that night, ‘some little smile’ on Mrs Proudlock’s part may have led him to believe ‘he was being graciously received’. It was not unknown, he added, for men to make this kind of mistake.

Killing Steward was the least of her intentions, he said. She wished only to be rid of him. An emotional, hysterical woman, she became mad with terror and lost all sense of what she was doing. The person in the dock was but a young girl, he went on. A young girl with a baby face. Did she look like someone who would commit a deliberate, atrocious murder? Of course not. Such a thing was impossible to imagine for the very good reason that she had absolutely no motive. When she fired, she had no idea what she was doing. Steward’s attack on her modesty had deprived her of judgement and reason.

‘I submit to you, gentlemen,’ Pooley went on, ‘that in this country where there are few white ladies and many men,’ there are times when a woman must act to protect herself. ‘And I ask you to say that a man who made such an attack on a virtuous woman is a brute, a beast; nay lower than a beast. He is a snake, and I ask you to say that one should no more hesitate to kill such a noxious animal than one should a snake. I ask you in the name of all that is manly, all that is straightforward, if you believe the deceased did commit that abominable outrage on the accused to say she was justified in brushing it away, crushing and absolutely extinguishing it.’

It was a good speech, though not good enough to convince the judge. At 4.47 on 16 June, Sercombe Smith, having finished reviewing the evidence, turned to his assessors, P. F. Wise and R. C. M. Kindersley.

‘Mr Wise,’ he asked, his voice barely audible in the packed courtroom, ‘have you considered your verdict on the charge of murder?’

Wise answered that he had. ‘My verdict says she is guilty.’

The judge now addressed Kindersley. ‘Mr Kindersley, have you considered your verdict on the charge of murder?’

KINDERSLEY: My verdict says she is guilty.

JUDGE: I concur.

Sercombe Smith turned to the prisoner and asked if there was any reason why she should not be sentenced to death. According to the Mail, Mrs Proudlock had become ashy white in countenance and stared blankly in front of her. With one hand, she gripped the rail of the dock and in the other held a bottle of smelling salts. She did not answer.’

It was now noticed that William Proudlock was not in court, and Robert Charter, Ethel’s father, left the room to look for him. When the two returned a minute later, Mr Proudlock, ‘in a state of great distress’, walked to the edge of the dock.

Addressing Ethel, the judge now proceeded. ‘I understand you have nothing to say.’

She nodded her head and then said no.

The court registrar called for silence while the sentence was being passed.

‘The court then became very silent,’ the Mail reported. Donning the black cap and ‘speaking in an emotional voice, the judge passed the terrible sentence: “I sentence accused to hang by the neck till she be dead.” Accused continued to stare wildly in front of her and seemed unable to realize that her death sentence had been passed. On seeing her husband standing by her, the accused burst into tears. Her husband supported her and, for a few seconds, the court witnessed a painful scene. The husband, leaning over the rail of the dock, kissed his wife several times and spoke consolingly to her. But to no avail. She broke down completely, and her sobs could be heard all over the court. Many remained to witness the pathetic scene.’

In a state of near-collapse, Mrs Proudlock, clinging fast to her husband’s arm and supported by several friends, had virtually to be carried from the courtroom. This time, Detective-Inspector Wyatt was not on hand to drive her back to prison. The proprieties had ceased to apply. Ethel Proudlock was a convicted killer.

3 (#ulink_ad306c1d-b3f5-52b7-b663-4efdc694f7cb)

A Profound Sensation (#ulink_ad306c1d-b3f5-52b7-b663-4efdc694f7cb)

The Proudlock case transfixed Malaya. ‘In the history of the FMS,’ said a Mail editorial, ‘the case is without a parallel … It is not exaggerating … to say that news of the death sentence passed upon the accused woman came as a great shock throughout Selangor and further afield.’

To understand the trial’s impact, it is necessary to bear in mind that, in 1911, there were only 700 Britons in Kuala Lumpur and a little over 1,200 in the entire FMS. This was a relatively small group whose members, bound by culture and language and social background, took an obsessive, almost familial interest in one another. No matter how trivial, everything they did was considered news. In the Mail, items such as, ‘Mr P. C. Russell has taken to a motorbicycle’, and ‘We regret to learn that Mrs Noel Walker is laid up with rheumatic gout’, were daily fare. Banal fare, perhaps, but then British Malaya was a banal place. Nothing much happened there. The British were ever complaining that the country was dull. Ethel Proudlock changed all that. One of their own had been convicted of murder. Not only was the victim English – which introduced an element of fratricide – but the perpetrator was a woman. Ethel Proudlock had violated two taboos – three if you counted her infidelity. The British in Malaya were understandably stunned.

What worried them particularly was the impact this would have on their standing, not just locally as the standard-bearers of civilization, but in England, where many people saw them as sybarites, a charge that deeply offended them. In their own estimation, they were models of rectitude: conscientious, enterprising, industrious – everything one would expect of a group whose job it was to build an empire. At great risk to themselves, they believed, they had come to Malaya to bring civilization to a backward people And did those at Home (in the Mail, ‘Home’ was always capitalized) thank them for it? Quite the contrary; they were defamed and vilified.

Few in England knew anything about Malaya. They were ignorant of the heat, the insects, the monotony, the risks to life and limb. They couldn’t even find it on the map. Letters were for ever turning up in the FMS capital addressed to Kuala Lumpur, India; Kuala Lumpur, China; Kuala Lumpur, Tibet; even – and this is my favourite – Kuala Lumpur, Asia Minor. ‘This diversity, of course, has its charm,’ the Mail remarked in 1910, ‘but it’s not particularly gratifying to those who think that the FMS should, owing to their increasing importance, be brought geographically to an anchor.’

They had been brought to an anchor now. Word of the Proudlock trial quickly spread beyond Malaya. It became a topic of conversation not just in India and Australia, Canada and New Zealand, but in the British capital itself. ‘Several London newspapers which arrived … last night’, the Mail reported with some embarrassment, ‘publish fairly long reports of the Kuala Lumpur tragedy. One paper devotes nearly a column to the affair under the heading, Sensational Case in British Colony.’ (Another gratuitous offence, this: the Straits Settlements were a colony; the Federated Malay States were a protectorate.) People were finally talking about Malaya, but what they were saying did not redound to its credit.

Small though the British community was, Steward’s murder polarized it. Some saw the trial as a travesty and claimed that a gross injustice had been done. A decent woman had defended her honour and, instead of being celebrated for her courage, now found herself under sentence of death. It was unconscionable, these people said, none more passionately than ‘Irishman’.

In a letter to the Mail, ‘Irishman’ described Mrs Proudlock as a modest, quiet and unassuming woman, devoted to her husband and her daughter. ‘I put it to the community at large,’ he wrote, ‘is not a woman justified in defending her honour which, to many, is dearer than their lives? Or are we to consider our wives and daughters so little above the brute creation that a defence of their honour is unjustified by the laws of the land we live in.’ Having had his say, he felt compelled to explain himself: ‘I append the nom de plume Irishman … because although we are impulsive and demonstrative as a race, in no country in the world is the honour of women held in higher reverence.’

There were other testimonials. ‘Having known Ethel Proudlock intimately for the past 11 years,’ ‘FMS’ wrote, ‘I feel it is due her to say that, in all those years, I have found her to be sincere, truthful, modest and chaste in conversation.’ Another letter a day later applauded her bravery: ‘The death sentence is little likely to prevent the English woman doing her duty in a similar emergency, I trust. Thank God that there are many of them of Mrs Proudlock’s pluck.’

Modest? Chaste? Death before dishonour? Even in 1911, there were parts of the world where much of this would have sounded dated. British Malaya, though, was not one of them. Though Victoria had died a decade earlier, Kuala Lumpur was still very much a Victorian enclave. Many of its inhabitants had come to the FMS in the 1890s and, by 1911, the values and attitudes they’d taken with them, instead of withering had, if anything, grown more vigorous. An example of this is the view they took of women.

One of the most popular books in the Kuala Lumpur Book Club – facetiously known as the Dump of Secondhand Books – was John Ruskin’s Sesame and Lilies. The volume contained what may be Ruskin’s most famous lecture, ‘Of Queen’s Gardens’. The lecture – a key Victorian document and hugely influential – defined the ideal woman as a creature both sweet and passive, obedient and gentle, pliant and self-deprecating. The title refers to Ruskin’s view that a home run by a woman conscious of her responsibilities is more than just a dwelling place; it becomes a place of enchantment, a garden graced by a queen.

In 1911 in Malaya, women were still expected to conform to the Ruskin paradigm: a person who didn’t seek to realize herself, but was content to be her husband’s instrument – his subject, even. Always aware of the duty she bore him, she ministered to his needs and deferred to his better judgement. If called upon to do so, she was ready ‘to suffer and be still’ – the words Sarah Stickney Ellis used in 1845 to describe a woman’s highest duty. But a life of self-renunciation was not enough; she had also to be pure. Purity was a woman’s greatest asset. Take it away and she promptly became a brute. It was a woman’s job to civilize men, to raise them up. (Here, her task was analogous to that of Malaya’s empire-builders.) She had to be ‘the angel in the home’, a moral touchstone to whom others turned for guidance. It was on this account that the so-called fallen woman inspired such horror. A woman who strayed from the path of virtue didn’t just jeopardize her own life, she jeopardized the lives of those who most depended on her: her husband, whose shame now made him the object of scorn; and her offspring, who would ever bear the taint of their mother’s sin.

Mrs Proudlock, if she did not own one herself, would certainly have been familiar with a print that hung in many Malayan homes: Augustus Egg’s Past and Present No. 1. It depicts a man, slumped in a chair and deep in shock, clutching in his left hand a letter apprising him of his wife’s adultery. His wife, meanwhile, has collapsed at his feet – the collapse as much moral as physical – while his two small daughters, motherless now and little understanding the tragedy that has overtaken them, innocently build a house of cards.

Concupiscence in a wife was considered monstrous, not least because it threatened the social and moral order. During sex, men liked to believe, a woman gritted her teeth and tried valiantly to think of higher things: her garden, perhaps, or her needlepoint. An adulteress was worse than a whore who, very often, could blame her degradation on poverty. A middle-class woman had no such excuse. She was a person of means, even if, in most cases, those means belonged to her husband.

In British Malaya, as in other parts of the empire, the erring woman was an object of such revulsion that even murder inspired less horror. During the trial, the British were not nearly as concerned that Mrs Proudlock had killed a man as they were that she might have broken her marriage vows. Ethel knew this as well as anyone which is why, speaking through her lawyer, she told the court that as much as her life meant to her, her reputation mattered more. It is also why the Mail expressed such satisfaction when Sercombe Smith gave the allegations of adultery short shrift. ‘The insinuations made against the moral character of Mrs. Proudlock were very serious,’ said the paper, ‘and we will be supported by everyone when we express our pleasure at their withdrawal and the manner in which [the judge] laid emphasis on the fact that she was completely cleared of any such imputation.’

While ‘Irishman’ and others like him continued to proclaim Ethel Proudlock’s innocence, while petitions circulated and defence funds were set up, while cables were sent to the British king, and people demanded a return to the jury system, there were those who believed that the condemned woman had got her just desserts.

Rumours abounded. It was whispered that Ethel had been in love with Steward for over a year and had been seen more than once hurrying to his home in Salak South; that she despised her husband and longed to be rid of him; that she and Steward had meant to elope.

It was also claimed that she had had not just one affair, but several – and some of those concurrently. In one of the more sensational versions of what supposedly transpired that night, it wasn’t Ethel who killed Steward, but a second suitor who, dropping by on a whim, took it amiss that another was making free with the object of his affections.

The source of this story was an Indian nightwatchman who, minutes after hearing the shots, claimed to have seen a fully-dressed Englishman swim across the Klang river, then in flood and swarming with crocodiles. Since Ethel now had a corpse on her hands, fleeing like that was hardly gallant, but because the killer was a favourite of hers – the story gets more and more outlandish – she sacrificed herself to save him, telling the police it was she who pulled the trigger.

In another version, no less bizarre, William Proudlock was the killer. Having learned that his wife had taken a lover, he set a trap for Steward that Sunday, waiting in the hedge until the miner turned up and then dispatching him. Why, then, did Mrs Proudlock stand trial? Because, this story goes, her husband threatened to expose her: unless she admitted to the crime, he would reveal her to the world as an adulteress.

So many theories. For most, the temptation to speculate was irresistible. Even Mabel Marsh succumbed. According to Marsh, the normally sensible headmistress at KL’s Methodist Girls’ School, it was William Proudlock who had tired of Ethel, not the other way around, and it was he who wanted a divorce. But how? The lady was above reproach. So Will recruited Steward and a plan was hatched: Steward would go to the bungalow, seduce Ethel, and Will would ‘discover’ them in flagrante. But the fates willed otherwise, and when Will got home, after being delayed by all that rain, Steward was already cold.

In a letter to the Mail, one man dismissed these stories as mean-spirited and vicious and accused his countrymen of lacking chivalry. ‘How men can attack a defenceless woman in her darkest hour of overwhelming grief is a mystery,’ he wrote. ‘Surely such conduct is altogether inconsistent with the conduct of a man and that of a gentleman.’

As the controversy grew, even Sercombe Smith came in for criticism. The charges became so virulent in some cases that the Mail had to tell its readers to desist. While it sympathized with Mrs Proudlock, the paper said, ‘we decline to associate ourselves with the hysterical outbursts which have followed the judicial decision … Correspondence has already appeared in our columns touching upon the case, and the opinions of our readers will receive publicity within limits. But for those who have gone to all kinds of adjectival extremes in the attempt to splutter forth their wrath against the judge and assessors, it may be added that their effusions will find the oblivion of the waste-paper basket.’

The attack was now taken up by Capital, a paper published in Calcutta. Describing the trial as ‘a powerful and fearful failure of justice’, Capital said it evoked the worst excesses of Bardell vs. Pickwick. ‘The verdict is ridiculous,’ it went on. ‘If, as the prosecution endeavoured to prove, the man was lured to the house with the intention that he should be shot out of revenge, jealousy or pique, no mercy should be shown. If, on the other hand, the unfortunate woman shot the wretch in defence of her honour, who will dare to say she was wrong? It comes to this: that in the FMS a woman who defends her honour must look for no mercy from a British judge and assessors.’

Sercombe Smith, it said, was a buffoon who had prostituted his office ‘and defiled the ermine which British judges are supposed to wear’. Capital then proposed some rough justice of its own. It was time to apply lynch law, it suggested. Tar and feather the man. And when that was done, string him up.

All this was profoundly gratifying to the Proudlock camp. The authorities, though, were not amused. When the Times of Malaya, a paper published in Ipoh, reprinted the Capital article, the government denounced it as defamatory and went to law. The editor of the Times, having badly underestimated official sensitivities, now tried to make amends. He issued an apology in which he described the article as ‘abominable and scurrilous’. The government was not appeased, however, and, on 31 July, a court ordered the editor to pay a fine of $350.

Horace Bleackley, author of A Tour in Southern Asia, now added to the furore by suggesting that assaults like the one Ethel supposedly endured were not uncommon. Malaya, he said, was full of men like Steward, whom he characterized as one of the many satyrs ‘infecting’ those colonies where men outnumber women. This was considered a low blow, not least because Bleackley made these charges in a letter to London’s Daily Mail. The community was outraged: one of its own had betrayed it. The Malay Mail thought so, too. ‘We are not aware’, the paper said in an editorial, ‘that less respect and consideration are shown for European ladies in communities in Selangor than in an ordinary London suburban community. We may go further than that and say that quite the contrary is the case. We have the idea that nowhere at Home are women more honoured and esteemed than here, and there are no signs that the position held by them for so long is likely to change.’

It did not change. Writing as late as 1932, George Bilainkin, who edited Penang’s Straits Echo, complained that women were still being treated as if they were royals. ‘In the tropics,’ he wrote, ‘the simplest looking woman keeps every man on his mettle, for the plainest woman is a goddess.’ As Bilainkin described it, this made for extravagant behaviour. ‘Men are everywhere,’ he went on, ‘paying them idiotic compliments, running almost to greet them, jumping up as soon as they show signs of rising – spreading a smile as wide as a cat’s at a woman’s sign of willingness to dance.’

The authorities in Malaya had badly underestimated the impact of the Proudlock case. Could they have known the uproar it would cause and the divisions it would engender, it is unlikely that Ethel would ever have been tried. When the death sentence was handed down, there were complaints that the judge had been over-zealous; that he had failed to understand the intentions of those in power.

Mrs Proudlock had become a major embarrassment. Though she had her enemies, few wished to see her die on the gallows, and so it was decided to seek clemency for her. Just hours after the verdict was read, William Proudlock cabled the Secretary of State for the Colonies in London and appealed for a royal pardon in consideration of George V’s approaching coronation.

Others were busy, too. Her lawyers lodged an appeal, claiming that no motive had been established; the prosecution had unfairly painted Mrs Proudlock as a libertine; and it had not been proved that a person suffering a deep mental shock is accountable for her actions.

Also making the rounds were several petitions seeking a reprieve and addressed to the Sultan of Selangor. ‘The European petition has been signed by over 200 persons, and the Indian petition by about 500,’ the Mail reported. ‘A petition is also being prepared for signatures among the leading members of the Chinese community.’

A cablegram was dispatched to Her Majesty the Queen in Buckingham Palace. ‘We undersigned European women in Kuala Lumpur’, it read, ‘implore pardon at this coronation time for Ethel Proudlock, aged 23, wife and mother, sentenced to death for shooting.’ The cost of the cablegram, the Mail reported with some pride, ‘was almost $150’.

In Great Shelford, Cambridgeshire, Will Proudlock’s seventy-two-year-old father weighed in as well, writing to the Foreign Office to seek the help of Sir Edward Grey. In a letter dated 16 June, this former millwright told Grey that he had once worked on his estate and appealed to him to save ‘my poor daughter-in-law from the horrible fate awaiting her’. In poor health now – his sight was failing – Proudlock referred to Steward’s death as ‘this crushing calamity which has come upon me in my old age’. Ethel had not murdered anyone, he said; all she had done was defend herself ‘from being outraged by a brute’. Proudlock told Grey that he had once been a coal miner and had ‘started work in the pit as trap-door keeper at the age of eight years’. The letter ended: ‘I am, Sir, in dire distress, yours obediently, William Proudlock.’

On 26 June, the younger Proudlock received a reply from the Colonial Office informing him that if he sought leniency for his wife, he had best appeal to the Sultan of Selangor: ‘I am directed to inform you that… the exercise of the prerogative of mercy is a matter for the discretion of the local government with which His Majesty the King does not desire to interfere.’

Newspapers in England, making much of what they saw as constitutional anomalies, claimed to be shocked that an ‘Oriental potentate’ would have it in his power to determine Mrs Proudlock’s fate. But since even Lord Northcliffe must have known that this, like all the sultan’s other powers, was circumscribed, the ‘shock’ was largely bogus. Besides, this ‘potentate’ had a good heart. Richard Winstedt, who wrote the first Malay–English dictionary, described him as ‘a mild gentleman of refined manners and instincts’ whose hobbies ‘were religion, cookery and wood-carving’. (According to Winstedt, who was recovering from malaria when Steward died, the nurses looking after him in a Malayan hospital had no sympathy for Ethel. She had disgraced her sex, they said, and, in their estimation, hanging was too good for her. That changed, though, when the verdict was handed down. Then they went around the wards pleading with their patients to press to have her pardoned.)