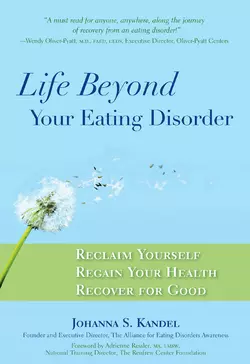

Life Beyond Your Eating Disorder

Johanna Kandel

Do you wish you could be happy with yourself, just the way you are?Get rid of the voice in your head that tells you that you’ll never be good enough? Make peace with food and your body? There is life beyond your eating disorder—and you deserve to enjoy every minute of it. Johanna Kandel, Founder and Executive Director of The Alliance for Eating Disorders Awareness, struggled with her eating disorder for ten years before finally getting help.Now fully recovered, Kandel knows firsthand how difficult the healing process can be. Through her work with The Alliance—leading support groups, speaking nationwide and collaborating with professionals in the field—she’s developed a set of practical tools to address the everyday challenges of recovery.Life Beyond Your Eating Disorder is your ultimate guidebook for the journey back to health, filled with the hope, insight and tools you need to:· Stop self sabotage and sidestep triggers· Quiet the eating-disordered voice· Strengthen the healthy, positive voice· Let go of all-or-nothing thinking· Overcome fear and embrace change· Stay motivated and keep moving forwardComplete with inspiring true stories from others who have won their personal battles with eating disorders, this book provides the help you need to break free from your eating disorder and discover how wonderful life really can be. Johanna S. Kandel founded The Alliance for Eating Disorders Awareness in 2000, a nonprofit organization dedicated to eating disorder prevention that provides essential resources to those struggling with an eating disorder.An active member of The Eating Disorder Coalition and National Eating Disorders Association, Kandel speaks frequently nationwide, and has appeared on NBC Nightly News and The Today Show, among others.

PRAISE FOR LIFE BEYOND YOUR EATING DISORDER

“A truly inspirational read. Johanna’s book is packed with sophisticated but practical advice on how to recover from an eating disorder. Most important, she offers hope to those who are struggling with these lethal illnesses.”

—Craig Johnson, PhD

Director, Laureate Eating Disorders Program, Laureate Psychiatric Hospital Past President, National Eating Disorders Association

“Johanna brings us an inspiring personal account of how her struggles with eating disorders impacted her life. In detailing the trials and tribulations she faced during her journey from illness to health, she forges an alliance with readers who suffer from eating disorders, offering them hope and helping them to become more amenable to seeking treatment.”

—David B. Herzog, MD

Endowed Professor of Psychiatry in the Field of Eating Disorders, Harvard Medical School

Director, Harris Center for Education and Advocacy in Eating Disorders, Massachusetts General Hospital

“Johanna’s warm, conversational tone invites the reader to join her as she openly shares her inner world, and the struggle and triumph of her recovery process. Compassionate, humane and wise, her inspirational story should not be missed. Life Beyond is a must-read for anyone, anywhere, along the journey of recovery from an eating disorder!”

—Wendy Oliver-Pyatt, MD, FAED, CEDS

Executive Director, Oliver-Pyatt Centers

“Finally a refreshing new voice speaks out about full recovery from eating disorders! I am proud to be on the same team as Johanna Kandel. If your life has been touched by an eating disorder in any way, you must read Life Beyond Your Eating Disorder.”

—Jenni Schaefer

Author, Life Without Ed and Goodbye Ed, Hello Me

“Johanna Kandel provides eating disorder sufferers the inspiration to believe in a future beyond recovery. Her exquisite use of metaphors, such as learning to use ‘all the crayons,’ ‘opening the middle drawer’ and the importance of ‘floaties,’ are so vivid that readers instantly understand what actions to take to move them into new spaces. She has indeed choreographed a dance of hope for all who read her book.”

—Susan Kleinman, MA, BC-DMT, NCC

Dance/Movement Therapist, The Renfrew Center of Florida

Past President, American Dance Therapy Association

“Whether you are struggling, in recovery, recovered or helping a family member or friend through this difficult time, this is an amazing resource for you. Johanna’s story gives each of us hope that not only can we recover from these illnesses, but each of us can help someone who may be struggling to find their way back to health and happiness.”

—Allison Kreiger Walsh

President and Founder, Helping Other People Eat (HOPE Inc.)

“Johanna has taken a brave step forward to reveal her journey through an eating disorder and recovery. Not only will her story shed light on this devastating disease, but her tireless work to make sure all people are aware of the effects of disordered eating is truly commendable. Being a recovered bulimic I know there is a light at the end of the tunnel and I salute Johanna for her tenacity to keep the switch on.”

—Kathy Kaehler

Trainer

Author,

Teenage Fitness

Ambassador, the Alliance for Eating Disorders Awareness

“This book is an excellent navigational tool for the journey toward recovery from eating disorders. With fierce enthusiasm, numerous insights and boundless encouragement, Johanna carries the recovery torch high, illuminating pathways so others can find a life beyond their eating disorder.”

—Anita Johnston, PhD

Author, Eating in the Light of the Moon

Life Beyond Your Eating Disorder

Reclaim Yourself Regain your Health Recover for Good

Johanna S. Kandel

Founder and Executive Director, The Alliance for Eating Disorders Awareness

Foreword by Adrienne Ressler, MA, LMSW, National Training Director, The Renfrew Center Foundation

For all the amazing women in Monday Night Support Group.

You are my biggest inspirations.

Quand on veut, on peut. (When you want it, you can do it.)

—ROSALIE BELILTY, MY GRANDMOTHER

(MY HEALTHY VOICE)

Contents

Foreword by Adrienne Ressler, MA, LMSW

Preface: My Mission

Chapter One: Food Fight

Profile in Recovery: Allison’s Story (#ulink_0178613b-508a-596b-b989-51de810bbd5c)

Chapter Two: Give Up the Guilt and Reclaim Your Power

Genetics—At Least Part of the Answer (#ulink_8d917473-3eeb-5390-85d4-d165af742d08)

Make That Information Work for You (#ulink_f4a458cc-5d96-5712-a4b5-e1486ac51bb0)

Nobody’s Perfect—Not Even You (#litres_trial_promo)

Change Doesn’t Come Easy (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Three: Learn to Use All the Crayons in Your Box

How Many Crayons Are in Your Box? (#litres_trial_promo)

Getting Comfortable Takes Practice (#litres_trial_promo)

Put In Your Application for Recovery (#litres_trial_promo)

Sinkies and Floaties—What Pulls You Down and What Gets You Through? (#litres_trial_promo)

Don’t Fall for the Bait and Switch (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Four: Kicking Off the Other Shoe

No, the Sky Isn’t Purple (#litres_trial_promo)

Knocking Down the Wall (#litres_trial_promo)

Don’t Start Out as a Downer (#litres_trial_promo)

And the Real Secret Is (#litres_trial_promo)

Profile in Recovery: Jasmine’s Story (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Five: From Recovering to Recovered—It’s a Process

How Long Can You Be Recovering? (#litres_trial_promo)

Each Moment Is a New Opportunity (#litres_trial_promo)

Why Does It Have to Be So Hard? (#litres_trial_promo)

Nothing Is Written in Indelible Ink (#litres_trial_promo)

Remember—You’re Still You (#litres_trial_promo)

To Build an Army, You Will Need to Recruit Some Soldiers (#litres_trial_promo)

Your Recovery Affects Others, Too (#litres_trial_promo)

Keep Track of Your Mile Markers So You’ll Know When You’ve Arrived (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Six: Beware of Fake Security Blankets

Sometimes a Security Blanket Might Not Be a Blanket at All (#litres_trial_promo)

The Danger of Trading One Addiction for Another (#litres_trial_promo)

Never Put All Your Marbles in One Jar (#litres_trial_promo)

Another Way of Looking at It: Diversification of Assets (#litres_trial_promo)

Let Go of the Old to Grab Hold of the New You (#litres_trial_promo)

Profile in Recovery: Jamie’s Story (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Seven: Getting to the Heart of the Artichoke

Are You Willing? (#litres_trial_promo)

Try Out New and Better Tools (#litres_trial_promo)

Start with the Outer Leaves (#litres_trial_promo)

Getting to the Core (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Eight: Laila, Rosie, the Incredible Hulk and Other Powerful Healthy Voices

Name Your Voice (#litres_trial_promo)

Change Your Focus to Change Your Mind (#litres_trial_promo)

Sometimes It’s Hard to Do It Alone (#litres_trial_promo)

Becoming Self-Considerate: Let Your Healthy Voice Take Care of You (#litres_trial_promo)

Profile in Recovery: Molly’s Story (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Nine: Talking Back to Ignorance

People Aren’t Mean; They’re Just Ignorant (#litres_trial_promo)

We Live in a World Full of Ignorant Messages (#litres_trial_promo)

Sometimes They’re Just Worried or Trying to Help (#litres_trial_promo)

Listen with Your Healthy Ears (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Ten: Bridezilla Meets Brideorexia and Other Triggering Occasions

The Madness Begins (#litres_trial_promo)

Going for the Gown (#litres_trial_promo)

Messages from the Bridal Industry and Others (#litres_trial_promo)

Bridezilla or Brideorexia? (#litres_trial_promo)

Stay Focused and Just Say No (#litres_trial_promo)

Whatever the Occasion, Keep Your Eye on the Prize (#litres_trial_promo)

Afterword: re(Define) (Real)ity

I Define What’s Real (#litres_trial_promo)

Recovery Means Steering Your Own Course (#litres_trial_promo)

Me 101 (#litres_trial_promo)

Accept the Gift That Is Offered (#litres_trial_promo)

What I Wish for You (#litres_trial_promo)

Getting Help

Acknowledgments

About the Alliance for Eating Disorders Awareness

About the Author

Foreword

JOHANNA KANDEL BEGINS THE PREFACE of this wonderful book with a disclaimer, saying what she is not—not a psychiatrist, therapist, nutritionist or doctor of any kind. She does say that she is a recovered individual who knows the physical and emotional journey of those who struggle with an eating disorder. But, oh, Johanna is so much more than that, as those of you reading this will certainly realize by the last chapter. She is a visionary, an activist, a healer, a teacher, an organizer, a warrior, a negotiator, a mediator, an author and an optimist. She is an inspiration to all whose lives she has touched, but never has she wanted to be a role model to be admired, copied or looked up to. This book provides many tales of recovery to help readers understand that there are many paths to healing, each as unique as the traveler herself. The message reinforced here is that there is no room for competition or perfection in recovery—no glory in being the fastest, the best, the thinnest or the most popular. Recovery is a process and the right process is the one that works best for you.

I have been involved in the field of eating disorders for almost thirty years, specifically in the area of body-image treatment and training. I met Johanna when she was nineteen years old and a volunteer working at the International Association of Eating Disorders Professionals (IAEDP) Conference. Just as Johanna has changed and grown since that time, so has the field of eating disorders itself. We now know more than we ever did before about the complexity of eating disorders: their connection to other psychiatric disorders, the gender-biased risk factors, the role of the brain, genetics and one’s temperament as variables, the connection between body shame and the culture, and the importance and effectiveness of complementary treatment modalities such as art therapy, dance/movement therapy, spirituality and yoga. Research has given us more information and more tools. We need to always keep the belief alive that recovery is possible, that no recovery is “perfect” and no one should ever give up. It may be useful to know that the word recover comes from the Latin and means “to bring back to normal position or condition.” Therefore, the person we discover during recovery is not someone new, but someone we have once been, a person whole and integrated. Recovery needs to be viewed as a continuous process that allows for the development of a greater sense of oneself, not a definite end of symptoms.

Years ago I came across the following passage in the book On Death and Dying by Elisabeth Kübler-Ross. I share it here because I associate it so closely with the struggle involved in freeing oneself from the grasp of the eating disorder:

It is not the end of the physical body that should worry us. Rather, our concern must be to live while we’re alive—to release our inner selves from the spiritual death that comes with living behind a façade designed to conform to external definitions of who and what we are.

Like a vampire who takes the very lifeblood from the innocents who fall under his spell, so, too, the eating disorder takes the very life spirit of those who relentlessly pursue the seductive belief that their true selves do not measure up to societal expectations and substitute a “perfect” self in order to be acceptable. Recovery involves a reclaiming of one’s true self, giving up the eating disorder identity, making peace with one’s body, shifting away from negative self-talk, relinquishing a victim mentality and staying optimistic despite setbacks and difficult times. As Dan Millman, author of Way of the Peaceful Warrior, said, “You don’t have to control your thoughts; you just have to stop letting them control you.”

Life Beyond Your Eating Disorder is a true recovery guide for individuals at any stage of eating disorder treatment or recovery. It is also excellent for families and friends to better understand how to provide support while maintaining their own lives. The book provides a candid, comprehensive look at the ups and downs of recovery and offers tips, resources, hands-on tools and strategies for breaking free from the distortions and beliefs that make up the world of the eating-disordered individual. The book is exceptional, as is its author.

Adrienne Ressler, MA, LMSW

National Training Director for the Renfrew Center Foundation

President, International Association of Eating Disorders Professionals (IAEDP)

Preface

MY MISSION

I learned this, at least, by my experiment; that if one advances confidently in the direction of his dreams, and endeavors to live the life which he has imagined, he will meet with a success unexpected in common hours.

—WALDEN, HENRY DAVID THOREAU

I’M NOT A PSYCHIATRIST; I’m not a psychologist or a therapist or a nutritionist or a doctor of any kind. But I have been an anorexic, an exercise bulimic and a binge eater, and if either you or someone you love is struggling with an eating disorder, I can honestly say that I know what you’re going through—maybe not the day-to-day details, but certainly the physical and emotional landscape of your struggle.

Perhaps one of the most important and startling things I learned both during my ten-year battle with an eating disorder and during my recovery is just how much ignorance, misinformation, fear and stigma are still attached to eating disorders even in the midst of the so-called information age. The entire time I was struggling and during my recovery process, I never knew anyone who had successfully recovered from an eating disorder. Truthfully, I didn’t know if recovery was even possible. All I knew was that I was sick and tired of being sick and tired, so I decided to seek help.

As I began my own journey to recovery, I vowed to myself that if I were given a second chance at life, I would do everything in my power to dispel some of that darkness and bring eating disorders awareness and information into the light. I strongly believe that no one should have to struggle with or recover from an eating disorder alone.

No one should have to struggle with or recover from an eating disorder alone.

Eighteen years ago, when I first began to develop my eating disorder, I had no idea how many people had the same terrible disease. I honestly believed I was one of the very few. But here are the facts: according to the Eating Disorders Coalition, today, in the United States alone, approximately 10 million women and 1 million men are struggling with anorexia or bulimia, and 25 million people are battling binge eating disorder. Eating disorders do not discriminate; they affect men and women, young and old, and people of all economic levels. You need to know that anorexia nervosa has the highest mortality rate—estimated to be up to 20 percent—of any psychiatric illness. And only one in ten people with an eating disorder receives any kind of treatment. Those figures make me sad and are, quite simply, unacceptable.

As I began to recover and find my strength, I kept the promise I had made to myself all those years ago, and in late 2000 I founded the Alliance for Eating Disorders Awareness in my hometown of West Palm Beach, Florida. The Alliance is a nonprofit organization whose mission is to prevent eating disorders and promote positive body image by advancing education and increasing awareness. To this end we do community outreach through talks at schools, we provide educational programs about eating disorders to therapists and other health-care professionals, we lead support groups for people in recovery and we do whatever we can to convince government officials that eating disorders ought to be a health-care priority. For specific information about the Alliance, see page 215. I believe we are fulfilling that mission with each person we are able to reach and inform that he or she is not alone and that recovery is possible.

I know how difficult the recovery process can be, but I want you to know that it is possible to get better—and it’s definitely worth it! We all trip and fall along the way. But recovery is not about the trips and falls; it is about what happens after you pick yourself up. It’s about getting back on your feet, dusting yourself off and moving forward, because that is how we learn. Realistically, neither life nor recovery is ever going to be a fairy tale, but we do have the power to create our own version of a real happily-ever-after.

It is possible to get better—and it’s definitely worth it!

Give yourself permission to imagine your life beyond your eating disorder. You will get to be present in every moment; you will get to feel; you will get to laugh. You deserve the freedom to live every aspect of your life.

Eating disorders can be very strong—mine spent years telling me all the things I couldn’t, shouldn’t or wasn’t good enough to do. That negative voice isn’t going to go away overnight, but there are many tools available to you as you recover to make that voice smaller and softer, and you need to gather and use every one you possibly can. This book is one of the tools you can use to free yourself from your eating disorder once and for all. As you read it, I hope the voice you hear in your head will be healthy, supportive and powerful enough to drown out whatever doubts you may still have about your ability to recover. I’ve gathered the tools that I offer here through many years of working with eating disorder practitioners, in support groups, walking next to people on their journeys to recovery and by becoming aware of what has helped others. And I hope that these tools will be as useful to you as they have been to me and to so many others. I’m sure some tools will be more useful to you than others, and that’s okay. I wouldn’t expect it to be any other way. The idea is simply to be willing to try, and if one thing doesn’t work, try something else. Just don’t stop trying.

We have the power to create our own version of happily-ever-after.

As you read on, you will come upon the stories of many different people from many different walks of life who have recovered from eating disorders, and you will come to see that they have followed many different paths. And just as there is no right or wrong way to recover, there is no right or wrong way to use this book. You might read it from cover to cover, or you might choose to read a few chapters and ponder them for a while. You might even decide not to begin at the beginning but to pick a chapter that looks interesting and read that first. Whatever works for you is the right way.

Lao Tzu, the sixth-century BC Chinese philosopher and father of Taoism, said, “A journey of a thousand miles begins with a single step.” Taking that first step toward recovery is really hard, and I admire you so much for taking this first step. You have come so far just by picking up this book. I know that together we can keep moving forward so that you, too, are able to create a new reality for yourself.

Chapter One

FOOD FIGHT

Dedicate yourself to the good you deserve and desire for yourself. Give yourself peace of mind. You deserve to be happy. You deserve delight.

—MARK VICTOR HANSEN, AUTHOR OF CHICKEN SOUP FOR THE SOUL

MY STORY HAS BEEN TOLD MANY TIMES. The specifics of my particular journey may be different from yours or someone else’s, but the basic story line remains the same. Since you’ve so graciously allowed me to walk beside you on your journey to recovery from your eating disorder, I think it only fair that I tell you something about my own experiences along that path. I don’t expect that your experiences will be exactly the same as mine, but I’m sure that at least some of what I describe will be familiar to you. And, really, the point is that whether or not you follow precisely in my footsteps, you, too, can and will arrive at a place where your eating disorder is no longer the first thing you think about the moment you wake up in the morning, the last thing you think about before you go to sleep and what you think about almost every moment in between. My hope is that this book will help to make your journey a bit easier as you travel your own path.

Let’s begin at the beginning. I was born and raised in West Palm Beach, Florida, but both my parents were raised in France. My father was a Holocaust survivor. When he was just four years old, his father was sent to Auschwitz. My father and his mother, my grandmother, were then separated from one another and went into hiding with different families in different places. Separated from both his parents for five years, my father missed out on much of the nurturing and early education he would otherwise have had during this critical time in his development. His father died in the concentration camp, but he and his mother were reunited after the war. Once he had completed his schooling, my father came to the United States to start a new life, returning to France once a year to visit his mother. It was on one of those visits that he met my mother, who had been born in Algeria and moved to France when she was eight years old. She was one of seven children in a family of a very poor and humble background; on many nights my maternal grandmother went to bed wondering whether she would be able to feed her children the next day.

You will arrive at a place where your eating disorder is no longer the thing you think about the moment you wake up in the morning, before you go to sleep and every moment in between.

As a result of their own upbringings, both my parents were intent on giving me every opportunity to soar in every aspect of my life, but they also had very high expectations of me. While my mother was the nurturer, very affectionate and simply wanting me to excel at whatever I did, my dad was very much the perfectionist. He expected me to become a doctor, at the very least, or perhaps even a nuclear physicist. Because I was an only child, all their hopes, dreams and expectations were invested in me. Today I understand that if they pushed me, it was because of the potential they saw in me, but at the time their expectations translated in my mind to a belief that I just wasn’t good enough to live up to the standards they—and my dad in particular—had set for me. But I tried. I always did as I was told, never gave them a hard time and put a lot of pressure on myself to do whatever I could to make them proud.

As a little girl I was extremely pigeon-toed, so my parents thought it would be a great idea to enroll me in ballet class to improve my grace and posture and help straighten out my feet. Much to their dismay, from the moment I got into that class, all I wanted was to become a ballerina. My mother continued to be supportive, but my father told me only recently that he had never expected me to become a dancer and had, in fact, been somewhat horrified by my announcement. Nevertheless, I started to dance at a local ballet academy and my training became very intense very quickly. By the time I was seven, I was already on a professional track. My parents had also enrolled me in various other classes, including gymnastics and piano, but my one true love remained ballet, and by the age of ten I was dancing four to five nights a week.

The summer before seventh grade, when I was twelve, I attended ballet camp in Chautauqua, New York, where I studied under a very well-known ballerina. I remember her saying that as dancers we needed to be “light as a feather” and the most beautiful ballerinas we could possibly be. Although she was undoubtedly talking about technique as much as weight, I immediately internalized the message that if I wanted to achieve my dream, I would have to be thin. If my dad had high expectations of me, mine for myself were even higher. Having internalized his message, it was no longer his voice but mine inside my head telling me that if I was going to do something—whatever it was—I needed to do it perfectly.

When I returned from camp at the end of the summer, I entered a new school for the performing and visual arts that had just been established. I had academic classes in the morning and dance classes in the afternoon. Then, when school was over, my mother picked me up and drove me and my friends to the dance academy of the local professional ballet company, where I was also taking classes. That fall the artistic director and the ballet mistress of the company came to our class and told us that they would be holding auditions and choosing a number of students to appear in that season’s production of The Nutcracker. They said that they were giving us this heads-up because they hoped that we’d work on our technique and also lose a bit of weight before the auditions took place. I wanted to be chosen so badly that if they’d told me to go upstairs and jump off the roof to get the part, I would have done it. But beyond simply wanting the part, I was already, even then, the quintessential people pleaser. Because of my father’s high expectations of me, as well as those I placed on myself, I simply didn’t believe, however well I did, that I was good enough. As a consequence, I believed that if I did enough to please other people, they would like me, and I also believed that if other people liked me, I would find it easier to like myself. Therefore, my incentive to lose that weight was twofold: to get the part and also to please the ballet mistress and artistic director of the company.

If I wanted to achieve my dream, I would have to be thin. If I was going to do something—whatever it was—I needed to do it perfectly.

I was still small and prepubescent. I had no idea how to lose weight, but I was determined to do it. At that time, in 1990, fat-free was all the rage, so I decided that the thing to do would be to cut as much fat as possible out of my diet. I remember telling my mother that I was going on a healthy-food diet and would be eating fruits, vegetables and lean meats. (You know, this is something I must have read somewhere—probably in one of those magazines that teach you five ways to lose weight without really trying. Certainly, as a twelve-year-old, it wasn’t anything I had come up with all by myself!) My mother, of course, thought that would be great. What parent wouldn’t be happy to hear that her child wanted to eat lots of fruits and vegetables? I bought a fat-and calorie-counter book and began to look up the content of absolutely everything I ate.

They hoped that we’d work on our technique and also lose a bit of weight before the auditions took place.

I don’t actually know if I lost any weight on my “healthy” diet, but I auditioned, and out of the fifteen girls in my class I was the only one not chosen for a part. The people from the ballet company took me aside and told me that the reason I hadn’t been cast was not that I wasn’t good enough, but rather that I looked so young. I was, in fact, one of the smallest and youngest in my class, but despite what they said, I believed they really meant that I was too fat and they were just trying to be kind. At that point I made a pact with myself: no matter what it took, I was going to get a part the following year.

I became very strict and rigid with my diet. I started to exercise even more, and I did lose some weight. People noticed very quickly, and they were telling me how good I looked, which made me feel great. But it also convinced me that I must have been really big. If not, after all, why would they be making such a big deal over the weight I’d lost?

Despite what they said, I believed they really meant that I was too fat.

Some time near the end of my seventh-grade year, our health teacher showed a made-for-television movie about a young gymnast who was battling an eating disorder. I think that most of my classmates watched the girl in that movie and thought, What is she doing? That’s terrible! But I looked at it and thought, Hey, I can do that for a while. I’ll just get down to my goal weight and then I’ll stop. I still thought losing weight was all about control, and since I was losing weight, I felt as if I were in control. Once I’d started, I just couldn’t stop. My eating disorder took control of me. In retrospect, the danger of those movies (and we’ve all seen them) is that they provide anyone who’s predisposed to developing an eating disorder with step-by-step instructions for how to do it really well.

Have you ever had a really bad stomach flu and had people tell you afterward how great you look because you’ve lost a few pounds? You might want to say, “Are you nuts? I was sick as a dog.” But you might also get the idea that if you stuck with a restrictive diet awhile longer, you’d look even better. That was more or less how it went for me. I cut back more and more on my food intake, and the response I got from other people was, “Wow, Johanna, I wish I had your willpower. You can just sit there with a piece of cake in front of you and not eat it.” Meanwhile, I was dying on the inside. People seem to think that anyone with an eating disorder simply isn’t hungry or is indifferent to food, but that’s the furthest thing from the truth. I thought about food all the time. My life revolved around what I was or wasn’t eating, how much I was exercising and all the negative thoughts that constantly played like an endless tape loop in my head: I’m not good enough. I’m not smart enough. I’m not thin enough. Nobody’s going to like me. Every day I was able to fight off the hunger, I felt I’d won—even though the only person I was at war with was myself.

I was dying on the inside. My life revolved around what I was or wasn’t eating, how much I was exercising and all the negative thoughts that played like an endless tape loop in my head.

By the time I entered ninth grade, however, I stopped getting positive feedback for losing weight. The remarks of my teachers and classmates began to change. People started to ask me if I was all right. And to tell me that I looked really tired. I was already exhibiting various symptoms of anorexia—the paleness, the circles under my eyes, the sunken cheeks, the tiredness. I was tired all the time, but I still had the mental strength to get up, go to school, dance eight hours every day and maintain straight As. I was truly running on empty, but for the first time in my life I felt that I was really good at something; my eating disorder was rewarding my perfectionism. Even though it was the furthest thing from the truth, I believed that I was in complete control. In addition, because so much of my limited energy was focused on my eating disorder, I didn’t have any energy left to think about anything else. I was emotionally numb, and I liked that because I no longer had to worry about whether or not I was good enough for my parents, for the world or for me.

Every day I was able to fight off the hunger, I felt I’d won—even though the only person I was at war with was myself.

Tenth grade was probably the height of my anorexia. I’d re-auditioned for several parts in The Nutcracker and gotten every role I tried out for, but now even my ballet instructor was very worried and started to express her concern about my weight. I still remember the day she took me aside and told me I’d lost too much weight. I felt so anxious and so guilty that I went home and had my first binge episode. I just wanted that feeling of anxiety to go away, and bingeing allowed me to stuff down the uncertainty and apprehension, at least for the moment. But almost immediately after, I would again be overwhelmed with guilt. Still, the anorexia continued throughout my junior and senior years of high school. I even passed out a few times—luckily never while I was driving.

I believed that I was in complete control.

Everything came to a head one evening in my senior year, when I had flown to New York to audition for a ballet company. When I got back home, still wearing my ballet tights under my jeans, I went into the bathroom to change. I’d always been very careful not to let people see my body, because I was so ashamed and uncomfortable in my own skin. When I looked in the mirror what I saw, although I didn’t realize it at the time, was a distorted image of myself. If you’ve ever looked in one of those fun-house mirrors that makes you look extremely distorted, you’ll know what I saw when I looked at my reflection. The only difference is that when you’re in the fun house, it’s the mirror that’s doing the distorting, but for me it was what my brain thought it saw. I wore layers of baggy clothes and always made sure to change in the bathroom with the door closed. On this particular evening, however, the door was apparently not completely shut, and just as I was taking off my dance clothes with my back to the door my mother happened to walk around the corner and glimpse for the first time in almost six years what I had been so careful to hide. When she saw me, she started to cry. She began shaking me and screaming, “What are you doing? You’re killing yourself!”

I no longer had to worry about whether or not I was good enough for my parents, for the world or for me.

Whenever I tell my story, people want to know, “What about your parents? Didn’t they notice anything?” I admit that I sometimes wondered that myself; however, by that time I was driving myself to ballet class, and if my mother ever did see me in performance, I was on a stage, wearing a tutu and tights, with makeup on and my hair in a ballet bun. In other words, I was no longer Johanna. And the truth is that many people did know what was going on. I know now that several of my teachers had noticed my weight loss and expressed their concern to one another. And my best friends admitted later that they had been very worried but had been afraid to confront me because they thought I’d be angry and that would be the end of our friendship. In fact, while everyone knew I had a problem, no one quite knew what to do about it.

I’d always been very careful not to let people see my body, because I was so ashamed and uncomfortable in my own skin.

In addition, I’d become extremely manipulative and careful about keeping my secret from my parents, because I knew they were the only ones who could force me into treatment—and the last thing I wanted to do was let go of the eating disorder. It was my best friend and yet my worst enemy; it was what I knew and what I could count on. It was safe and, although very dangerous, very comfortable. I knew what it was like to have an eating disorder; I didn’t know what it was like to recover—and what is known always feels safer than what is unknown. If there was a message on our answering machine from a friend’s parent, I erased it before they got home. If my guidance counselor asked what I’d eaten that day, I’d come up with a whole list I could rattle off so convincingly that I sometimes got angry with myself for eating things I actually hadn’t eaten. The truth was that my parents didn’t really have any reason to think there was anything wrong. My mother had come from a family where every bite of food was cherished, and she’d been very thin as a young woman, so the idea that I would purposely starve myself was a completely foreign notion to her. In addition, I was dancing six to eight hours a day, so it would stand to reason that I was thin, and whenever I ate with my parents I managed to manipulate my food and make it appear as if I were eating. For people who don’t have an eating disorder, all this may be hard to imagine, but if you have or have had an eating disorder, I’m sure you know exactly what I’m talking about. Those of us with eating disorders become experts at keeping our secrets.

When my mother saw me, she started to cry. She began shaking me and screaming, “What are you doing? You’re killing yourself!”

In any case, that evening in the bathroom, my mother couldn’t help seeing what I’d been hiding, and all I could do was to keep reassuring her that everything was okay, I was in control and I knew what I was doing. Still, she insisted that I see a doctor, and she went with me. To my amazement, when I got on the scale he looked at my weight and said, “You’re really thin, but you’re okay.” Then he looked at my mother and said, “Just give her some of your good French cooking.” This was 1996. Anorexia and bulimia were no longer secrets. They were listed in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders; people knew about the death of Karen Carpenter; Tracey Gold had gone public about her battle with an eating disorder; and the seminal movie about anorexia, The Best Little Girl in the World, had aired on network television more than ten years before. But then, as now, there were many health-care providers who hadn’t been properly educated about how to diagnose or treat eating disorders. And, of course, when a parent hears from a doctor whom she trusts that her child is okay, her inclination is to be relieved and accept the diagnosis.

So I’d dodged that bullet, at least for the moment. But about a month later my mother noticed that I wasn’t getting any better. I still looked exhausted, with dark circles under my eyes, and I was still losing weight. At that point my mother realized that the problem was more serious than my simply being a little thin. She took me to another doctor, who was educated enough about eating disorders to diagnose my anorexia. When I saw the word anorexia on my chart for the first time, I freaked out. I was terrified that my disorder would be taken away from me. And, most of all, that they would make me gain weight! Although on one level I didn’t want to live with my eating disorder, on another level I was petrified of living without it. It was the only aspect of my life that I believed to be in my control, and there was no way I was willing to give that up.

If my guidance counselor asked what I’d eaten that day, I’d come up with a whole list I could rattle off so convincingly that I sometimes got angry with myself for eating things I actually hadn’t eaten.

I was put through a battery of tests that showed I had very low blood pressure, a very low heart rate, reduced kidney function and full-blown osteoporosis. You’d think hearing all that would have scared me into recovery, but no, it didn’t. Then the doctor asked when I’d had my last period, and I just cracked up. He asked me why I was laughing, and I responded, “Oh, N/A!” “N/A? What does that mean?” “It means ‘not applicable.’ I’ve never gotten a period.” “And you’re seventeen and a half?” “Yes, but it’s okay. I’m a ballet dancer. We don’t get those.” “But you’ve never gotten your period? That’s not good. That’s contributing to your bone loss and a lot of other things, too.” My body was being starved, and we all need to eat. We need fuel, and my body was getting that fuel wherever it could—internally, from my bones, from my body fat and from my muscles.

The doctor looked at my mother and said, “Just give her some of your good French cooking.”

The doctor then told me that I’d probably have fertility issues in the future, and my response to that was “Good. I don’t want to get fat, anyway.” Sad as that may sound, I simply had no sense of the danger to my health. I couldn’t see past the present moment. In that moment all I wanted to do was dance, and I knew that I needed to be thin to dance. Honestly, it was the only reason I was living at that time.

On one level I didn’t want to live with my eating disorder; on another level I was petrified of living without it.

Even though the doctor knew enough to diagnose me, he still didn’t know how to treat me. His approach was to give me hormones and steroids to bring on my period and stimulate my appetite. Basically, he was going to fix me with medication. I was still restricting my food intake, but because of all the medications I was taking, I gained weight. In a matter of three months I doubled my body weight! Please note, I’m purposely not giving you numbers here, because I would never want my number to become a goal weight for anyone else. If you’re struggling with an eating disorder, I can guess that you focus on numbers—the number of calories, fat, carbohydrates and proteins in foods you eat; the number you see on the scale; and the number you believe would be perfect. I also need to say right now—because I know that if you’re reading this, you’re probably thinking, That’s it, no treatment for me! No one is going to make me gain that much weight!—that it is extremely unlikely something like that would happen today.

The diet gave me back my sense of control. My anorexia and the exercise bulimia came back with a vengeance.

For me, however, the doctor was giving me all those medications at a time when I felt completely helpless. Up to that point I had always felt as if I were in control, but now, no matter what I did, the drugs were causing me to gain weight. I was incredibly anxious and depressed, and I felt as if everything I’d worked so hard to attain, including my ability to dance, was slipping through my fingers like grains of sand. I was starving, and I figured that since I couldn’t control my weight anyway, I might as well just eat and use the food to numb all those negative feelings. That was when the bulimia started. I never used self-induced vomiting, but I would binge and then purge with laxatives and compulsively overexercise.

At that point, I was about to graduate high school, and this was the time when I should have been auditioning to join a ballet company, but by that point I was too big to be a ballet dancer. Instead, I determined to use the next year to get myself back in shape and back on track. I stayed home and continued to dance at the academy where I’d been studying. By then I was in the most advanced group, so my classmates and I were often invited to take company class and sometimes also given roles in their productions.

Now I didn’t know who I was. My only remaining sense of identity came from my eating disorder. I had, in essence, become my eating disorder.

At the same time, without telling my primary care physician, I also went to see a doctor who was a metabolic specialist and who already knew my history. I remember her asking me what I wanted more than anything in life. I said it was to dance, and she told me that she’d help me make my dream come true. Her way of doing that was to put me on a totally insane plan that involved my taking about thirty supplements a day (to date I still don’t know what was in them) and going on a refined Atkins-type diet. Although I knew it wasn’t healthy and was the last thing that I should have been doing, it gave me back my sense of control, and, in fact, I did start to lose weight.

As I began to regain a (misguided) sense of confidence, I auditioned and was offered an apprenticeship with a ballet company in Orlando. By then I’d achieved what the metabolic doctor considered to be my goal weight, so she took me off most of the supplements I’d been taking. I was supposed to be maintaining my weight, but once I was on my own again, I began to restrict even the meal plan she’d given me and I stopped taking the medications that had been prescribed by my primary care physician. My anorexia and the exercise bulimia, which had never really gone away, came back with a vengeance, and I fell back into my disordered eating really hard and really quickly. About six weeks later my mother came up to Orlando to see me perform, and, of course, she noticed how much weight I had lost.

If I were given a second chance in this journey called life, I would help others battle eating disorders so they wouldn’t travel down the same path I did.

By then I was nineteen years old and really, as the saying goes, sick and tired of being sick and tired. Both my parents and my doctors had speculated that if they took ballet out of the equation, my eating disorder might just go away, and I actually thought so, too. After all, I really believed that the whole thing had started because I wanted to lose weight in order to be a more beautiful dancer. And I even remembered that when I was in high school, I’d look at the kids who were music students and think, Wow, if I were a musician instead of a dancer, I could eat anything I want. I don’t believe it anymore, but at the time the idea that my dancing had caused my eating disorder seemed pretty logical to me.

I resigned from the company and thought that my eating disorder would go away immediately. Boy, was I wrong. In truth, dancing was the only thing that had been keeping me alive. Aside from my eating disorder, it felt like my only identity. Now I didn’t know who I was. My only remaining sense of identity came from my eating disorder. I had, in essence, become my eating disorder.

I was alone in Orlando with nothing to do, and I was floundering. I’d never intended to go to college, and I’d never considered what I might do with my life if I wasn’t dancing. I started to binge more and more, because I thought that was the only way I had to relieve the pain I felt. If you’ve binged yourself, you know that it has nothing to do with enjoying the taste of the food you’re eating. Actually, in the moment, you don’t taste anything at all. It’s all about stuffing down (or numbing) and running away from any kind of feeling or sensation. After I binged, I felt awful and guilty about what I had just done. When I was restricting, I felt good about myself because I felt that I was in control. When I binged, I felt an enormous loss of control.

I called my parents and, for the first time, admitted to them that I really needed and wanted help.

I remember waking up at two o’clock one morning and realizing that I had no sense of who or what I was. My parents had been urging me to go back to school, and I decided to enroll in a psychology course at the local community college, thinking that I might gain some insight into what was going on in my own mind. It was while I was taking that course that I made another decision: if I were given a second chance in this journey called life, I would help others battle eating disorders so they wouldn’t travel down the same path I did. Since all I knew besides ballet was my eating disorder, I determined that I would become a therapist specializing in eating disorders. After sticking my toe into academic waters, I went back to college full-time, entering the University of Central Florida in January 1998 and, in true perfectionist style, starting to follow an absolutely ridiculous, stressful schedule. (I actually graduated college in two and a half years…which is definitely not a healthy thing to do.)

I really had nothing in my life to focus on except school, and being focused on school became another way to numb my feelings. So that was where I transferred my obsession, taking more than the required number of classes. Given that I was in a cycle of restricting during the day and then, when classes were over, going back to my apartment and bingeing, my career choice was at the time somewhat ironic and, in retrospect, unrealistic. By that point I was wearing plus-size clothing, and to say that I was not a healthy girl (mind, body and spirit) would be the understatement of the century. But I knew that if and when I got better, this was what I wanted to do with my life.

In pursuit of my newfound career objective, I called a few local practitioners who specialized in eating disorders and asked whether I could become an intern or shadow them in their practice. They all told me that because of confidentiality issues, they couldn’t allow me to do that, but one of them also told me about the International Association of Eating Disorders Professionals (IAEDP), an eating disorders organization that had just relocated to Orlando and was looking for volunteers. I called the executive director, Dr. Marie Shafe, who asked me to come in for an interview. She turned out to be one of the most amazing and inspiring people I’ve ever met in my life, and she urged me to volunteer. Before long, I progressed from volunteering to a paid position. I started to help out in the office, working on the newsletter and working alongside the director as her assistant. By that time it was the year 2000. I was in college, applying to graduate schools and working when I realized I was actually falling apart at the seams. I was realistic enough to know, after taking so many psychology courses, that I couldn’t go to graduate school and learn to help other people until I’d helped myself. I called my parents, told them that I was putting graduate school on hold and, for the first time, admitted to them that I really needed and wanted help. I’d also confided in Dr. Shafe, and she helped me get into an outpatient treatment program.

Over the years I’d been to see many different therapists on several occasions, but until then I’d always told the therapist exactly what I knew he or she wanted to hear, and that was it. I simply wasn’t ready to hear what the therapist had to say to me. I wasn’t ready and willing to see a life without my eating disorder. I’d go to a nutritionist, take the meal plan I was given and throw it in the nearest trash can before I even got home. In other words, I manipulated everyone and sabotaged myself in order to maintain my eating disorder, which felt safe to me. The thought of giving up the eating disorder and going into an unknown place was much more frightening than maintaining the familiar, miserable as it was, and suffering the consequences.

I was still thinking in black-and-white, all or nothing. I was going to do recovery the same way I’d approached anorexia, wholly and completely. I slipped, as we all do, and boy, did I ever beat myself up.

But this was different. Now I had a nutritionist, a therapist and an entire treatment team, and I was truly ready to take back my life and get better. For the first time in my life I began to understand the feelings that underlay my eating disorder: why I hated myself so much, why I felt so undeserving, why I felt that everything had to be perfect. At first it was very scary to feel again after avoiding those feelings for so long. I didn’t like it one bit, but once I began to understand that I didn’t need to be perfect, that recovery wasn’t going to be perfect, I started to breathe again. It wasn’t easy, and I could not have done it if I hadn’t already come to the realization that I wanted to get better and was ready to do whatever was necessary for me to get healthy. Up to that point, I honestly hadn’t been willing; I just didn’t want to. No one—including me—could love me enough for me to be encouraged to get better. I’d devoted ten years of my life to my eating disorder, and now, for the first time, I wanted to live, laugh and feel good about myself again. I even wanted to go on a date. At the time, I hated my body so much that I was literally avoiding any kind of contact at all with the opposite sex. Instead of checking out the guys, I spent my time sizing up other women and comparing them to myself—and, not surprising, I was always the one who came up short. I felt as if someone had taken away my soul, and now I wanted it back.

Never once in my entire life had I awakened in the morning, looked out the window in sunny West Palm Beach and said, “Today I’m going to become an anorexic.”

I started to get better, but things didn’t immediately become all better. In fact, my recovery process was far from easy, predictable or perfect. That was yet another hugely important realization for me. Initially, I was still thinking in black-and-white, all or nothing. I was going to do recovery the same way I’d approached anorexia, wholly and completely. I’d decided to get better and, therefore, I would be completely better immediately. I would be the Queen of Recovery—at least that was what I thought. Of course, it didn’t happen that way; it simply isn’t possible. I slipped, as we all do, and binged—and boy, did I ever beat myself up afterward. As was typical for me, I used my slipup as an excuse to keep telling myself that obviously I wasn’t good enough to do even recovery correctly.

Slowly, however, my journey to recovery was progressing and I was gradually getting healthier, which meant that I was also seeing things more clearly—at least some of the time. Part of that clarity involved coming to the realization that I wasn’t going to be able to counsel people with eating disorders in a one-on-one therapeutic environment while I was still recovering myself. That relationship would simply be too intense and triggering for me, and I didn’t think I’d be able to maintain the proper therapeutic distance. In my heart, I knew I wanted to speak publicly about eating disorders because, as I was struggling with my own recovery, I really didn’t have anywhere or anyone to go to for support. It was completely up to me to hold myself accountable and go to my treatment sessions. I had a wonderful family and wonderful friends, but none of them really knew how to provide the support I so desperately needed. How could they have known? I was living by myself in Orlando, I didn’t confide in them, and therefore they had no idea what I was really going through.

There were several times when I could have easily lost my battle with my eating disorder, but I hadn’t.

I didn’t want anyone else to have to walk that path alone. I didn’t want them to think that they couldn’t get better. I wanted to walk beside them when they were going through the same thing I had so that they would know they were not alone. During the entire time I was in treatment, I had never known a single person who got better. I was white-knuckling it the entire way, and I wanted to make it different for others. I loved the work I was doing at IAEDP, but I wanted to get out there and bring education and awareness to boys and girls who were the “me” I’d been in seventh grade. I wanted to tell them that I knew what they were thinking—that they thought they were in control, that they could just lose some weight and then stop. I’d walked through that door, so I knew that once it slammed shut behind them, they’d have no way to get out. Never once in my entire life had I awakened in the morning, looked out the window in sunny West Palm Beach and said, “Today I’m going to become an anorexic.” I wanted them to know that, and I wanted them to understand that if they walked through the same door I had, it might be the same for them.

During that first year of recovering, I remember talking to a friend on the telephone and laughing out loud. My friend started to cry and told me that she couldn’t remember the last time she’d actually heard me laugh.

Once I’d made the decision to focus on helping other people through education and advocacy, there was another phone call to my parents. I told them I’d decided not to go to graduate school, after all. Instead I was going to start my own nonprofit organization. I was starting to feel healthy; I knew I could do it, and I wanted to give back because I’d been given a second chance. There were several times when I could have easily lost my battle with my eating disorder, but I hadn’t. Now I couldn’t take my recovery for granted; I wanted to share what I’d seen and what I’d learned. I realize now that my parents had been assuming that as soon as I got better, I’d be going back to school. Needless to say, they were a bit shocked. My mother was supportive, but my father was very apprehensive. He really wanted me to follow the traditional educational route, the one he had always wanted and planned for me. In the end, however, they agreed to support me for a year—which at the age of twenty-one seemed like a lifetime to me.

I filed the incorporation papers for a nonprofit organization in October 2000, moved back home in December 2000 and in January 2001 opened the Alliance for Eating Disorders Awareness. I called all my friends, my family, all the people I knew from treatment and various therapists, and I asked them all to tell me: If they were the parent of a child with an eating disorder, or if they had a client with an eating disorder who needed support, what kind of organization and what kind of information would they want to have available to them?

Based on the information I received from friends, family and therapists, I decided that education was the place to start. I believed that sharing my story and promoting positive self-esteem were the way to go. To do that, I would go into schools, start talking to kids and tell them what I had found out during my struggles with my eating disorder. My first presentation was at a local private school in April 2001, and I was terrified. In my excitement about starting the organization, I’d forgotten that I’d failed speech class in college because I was afraid to speak in public. Put me on a stage to dance before an audience of thousands and I was fine, but public speaking was something else. Nevertheless, I prepared my talk, got up before a sea of high school students and shared my story. In the end, it was the best feeling I’d ever had in my entire life. I’d found my path and I knew it.

Now I can truly say I am recovered—recovery is definitely possible.

It’s now been nine years of an unbelievable journey. I remember the first time, during that first year of recovering, when I was talking to a friend on the telephone and laughing out loud. My friend started to cry and told me that she couldn’t remember the last time she’d actually heard me laugh. What an amazing day that was! I realized that, indeed, I could laugh again. And laughing feels really good!

If you’ve come this far with me, you’ve already gotten to the point where you are at least considering recovery. You’ve taken the first baby steps, and you’re probably scared. As much as we all want to get better, it’s frightening to give up something we know so well. When I was bingeing and restricting, I always knew exactly what to expect. I knew that if I did A, then B would happen. When I began my recovery, I had no idea what would happen, and for years I continued to tell people that I was recovering because I was still afraid to give up my eating disorder entirely. But now I can truly say I am recovered, and that recovery is definitely possible. Your path to health won’t be perfect or simple or straight any more than anyone else’s. In fact, it will be one of the hardest things you’ll ever have to do. But I can provide you with the tools I’ve acquired over many years to help you persevere through the highs and lows of recovery. Some of my tools will also become yours; others may not work for you. And you’ll probably be adding tools of your own. That’s the beauty of the recovery process: it is unique to each individual. There is no right or wrong way to recover.

Your path to health won’t be perfect or simple or straight. In fact, it will be one of the hardest things you’ll ever have to do. But I can help you persevere through the highs and lows.

There will surely be slipups, but it won’t always be so serious, either. We’re even going to have some good laughs along the way. And the one thing I can assure you is that recovery is more than worth it—it is without a doubt the best thing I’ve ever done for myself!

PROFILE IN RECOVERY: Allison’s Story

I first read Allison’s story in the newspaper the morning after she won the title of Miss Florida. I was immediately struck by how eloquently she spoke about her battle with bulimia: trying to live up to unrealistic standards, living life after her recovery and her passion for using her voice to create awareness and change. She used the platform her Miss Florida title provided to educate others and bring attention to how serious and widespread the problem of eating disorders really is. When her reign was over, she continued her outreach by creating her own nonprofit organization and traveling around the state speaking to students. I am deeply grateful that Allison has continued to use her voice throughout the years and that she now lives the life she imagined…eating-disorder free.

Ten years ago, my battle with bulimia was in full swing. My days were consumed by an illness I never expected or wanted in my life. When people think about eating disorders, they often think that they are a choice, but that simply isn’t true. Eating disorders are not choices; they are mental illnesses, and they are also the leading cause of death among all mental diseases.

Eating disorders are not choices; they are mental illnesses.

In order for you to completely understand why my eating disorder began, I think it is important for you to understand a little bit about my past. I grew up in a very competitive home. My mom was a former national champion baton twirler, and by the time I was five, I was well on my way to pursuing the same goal. From the very beginning, I was a complete perfectionist and put a lot of pressure on myself. From pushing myself in the gym to expecting straight As on my report card, I didn’t want to settle for anything less than the best.

One point I want to stress to you is that I didn’t wake up one day and decide I wanted to be a bulimic. I vividly remember when my eating disorder started. I’d had a bad day at the gym and was really upset. For some reason I got so worked up that I actually threw up. It just happened; but in that moment something was triggered in my mind that eventually led to a life consumed by an eating disorder and some very serious side effects.

I didn’t wake up one day and decide I wanted to be a bulimic.

For three years my eating disorder was my secret, but by the time I was a junior in high school, I physically could not deal with it anymore. I went to my parents for help, but they didn’t really know what to do. I became very angry with them for not being able to help me or give me what I needed, and at that point anorexia also came into the mix. By the time I started my senior year, my symptoms were very visible. I was extremely weak, I had lost half the hair on my head, I had broken blood vessels in my eyes, I had done damage to my esophagus from the bingeing and purging, I couldn’t digest food properly even if I wanted to, and I was at a dangerously low weight. By November, I knew I couldn’t live that way any longer. I went to my parents once again and at that point they took me to our family doctor, who diagnosed my eating disorder and told us that I would need to work with an outpatient treatment team. Together we found a psychologist, a psychiatrist and a nutritionist who would help me start to heal.

A major turning point in my recovery occurred when I left for the University of Florida the following fall. This was my opportunity to start my life over, but it also could have triggered my eating disorder again. I decided the best thing to do would be to surround myself with people who could help keep me strong and to get involved in groups that helped to prevent eating disorders. I volunteered at the student health-care center and started to tell my story. Interestingly, speaking out in public also helped me to help myself. I realized that by being open and honest about what I had been through, I was helping others who were either suffering or knew someone who was.

I realized that by being open and honest about what I had been through, I was helping others who were either suffering or knew someone who was.

At that point, I decided to start HOPE, Helping Other People Eat, which is now a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization that works for the prevention and awareness of eating disorders.

I also wanted to give back to those organizations and groups that had helped me during my struggle. The National Eating Disorders Association provided a wealth of information not only for me but for my parents. Currently, my involvement with NEDA ranges from being a yearly NEDAwareness Week coordinator to serving as the inaugural chairwoman of the National Junior Board. I also lobby for insurance parity with the Eating Disorders Coalition on Capitol Hill and with the NEDA STAR Program in Florida, and I am an active supporter of the Alliance for Eating Disorders Awareness.

In 2006 I won the title of Miss Florida and went on to compete in the Miss America pageant. During my reign as Miss Florida, I traveled the state, educating all age groups about eating disorders. Over the last few years, I have spoken to more than forty thousand people about these illnesses and have made a commitment to continue speaking and reaching out for the rest of my life.

I truly believe that we go through things for a reason. Knowing how terrible it was for me to suffer from an eating disorder, I now live my life every day trying to prevent others from traveling down that path and helping those who are suffering to find the help they need.

Chapter Two

GIVE UP THE GUILT—AND RECLAIM YOUR POWER

And the day came when the risk to remain tight in a bud was more painful than the risk it took to blossom.

—ANAÏS NIN

IF YOU’RE ANYTHING LIKE ME—and the many, many people I’ve met giving presentations and in my support groups—you may have spent a lot of time beating yourself up and wondering how you could ever have allowed this to happen.

I honestly thought there was a perfect weight that would make me a perfect person.

In my case, there were fifteen young dancers in my class when we were told to lose weight. The others just lost a few pounds and then went on about their lives, while for me the need to lose just continued and continued and continued. Each time I got close to my weight goal, I raised the bar and moved the goal line back. I honestly thought there was a perfect weight that would make me a perfect person. And each time I reached a lower weight, I really believed that when I reached that next new lower number I’d be satisfied. I just chased that rabbit—the illusive, perfect me—down the rabbit hole and found myself in a totally strange world, one in which I actually didn’t have any control even though I had convinced myself that I was in complete control. And then, when I tried to climb out, it was like walking through a hall of mirrors; I couldn’t find the exit no matter how hard I tried.

I just chased that rabbit—the illusive, perfect me—down the rabbit hole and found myself in a totally strange world, one in which I actually didn’t have any control.

Even when I was in recovery, I still kept thinking that I should have been stronger, that I should never have let this happen. I should never have allowed myself to slide down into that hole. Why, why, why did it happen to me?

Genetics—At Least Part of the Answer

One of the most exciting and enlightening moments of my life came when I learned that research indicates there is a genetic component to eating disorders. Some people are born more vulnerable than others to developing an eating disorder, and various researchers have linked the problem to the disruption of serotonin levels in the brain. Serotonin is a neurotransmitter, a brain chemical whose functions include the regulation of both mood and appetite. Some researchers have theorized that increased serotonin levels may leave people in a perpetual state of anxiety, leading them to gain some sense of control by restricting food intake. Low serotonin levels, on the other hand, could lead to bingeing on foods high in carbohydrates, which would temporarily raise serotonin levels and elevate mood.

In a strange way it was extremely liberating for me to read the following statement made by Dr. Thomas R. Insel, director of the National Institute of Mental Health, in an October 5, 2006, letter to the chief executive officer of the National Eating Disorders Association:

Research tells us that anorexia nervosa is a brain disease with severe metabolic effects on the entire body. While the symptoms are behavioral, this illness has a biological core, with genetic components, changes in brain activity, and neural pathways currently under study.

While you might think it would be disturbing for me to learn that anorexia was a brain disease, it was actually validating to know that there was a biological explanation for my problem. And Dr. Insel didn’t leave me feeling powerless, because he went on to say that “most women with anorexia recover, usually following intensive psychological and medical care.” So, it is truly not your fault that you have an eating disorder. Even better, it is possible to recover—and you shouldn’t be expected to cure it all on your own.

Simply telling someone with an eating disorder to “just get over it and sit down and eat” is never going to work. What are you supposed to say to that? “Oh yeah, you’re right. For all those years I was struggling with anorexia the real problem was that I just forgot to eat, but now that you’ve reminded me I’ll remember. Thanks!” No! Initially, I’d actually thought it would be that easy. I thought I could just sit down, eat a meal and not restrict, binge or act out. But, of course, it wasn’t easy. It isn’t, and it’s not supposed to be. But now I have a valid, scientific explanation not only for why I’d developed an eating disorder but also for why recovery wasn’t so easy.

It is truly not your fault that you have an eating disorder. It is possible to recover—and you shouldn’t be expected to cure it all on your own.

Walter Kaye, MD, of the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, working with an international group of doctors, has collected information from more than six hundred families in which two or more members had an eating disorder. In an article titled “Genetics Research: Why Is It Important to the Field of Eating Disorders?” Craig Johnson, PhD, director of the Eating Disorders Program at Laureate Psychiatric Clinic and Hospital in Tulsa, Oklahoma, states that these results may be nothing short of a breakthrough. They suggest that both anorexia and bulimia “are as heritable as other psychiatric illnesses such as schizophrenia, depression, anxiety and obsessive-compulsive disorders.” And other clinical studies have also supported this evidence. One, conducted at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, reviewed information from more than thirty-one thousand people in the Swedish Twin Registry and determined that genetics is responsible for 56 percent of a person’s risk of developing an eating disorder—with environmental factors determining the rest.

As with almost all diseases and conditions, genetics may predispose us to being more susceptible, but our environment and lifestyle choices either increase or decrease our chances of actually getting the disease. According to Dr. Kaye, “We think genes load the gun by creating behavioral susceptibility, such as perfectionism or the drive for thinness. Environment then pulls the trigger” (Journal of the American Medical Association, Vol. 290, No. 11, Sept. 17, 2003). The problem, of course, is that if we know, for example, that we’re predisposed to developing high blood pressure, we can avoid eating salty foods. But we can’t remove ourselves from the world, and the world we live in is filled with messages and images that hold up thinness as a measure of perfection. All we can do is try to nurture our children’s self-esteem and help them to develop a healthy body image.

As I thought about Dr. Kaye’s words, I realized that when I started down my path to anorexia and bulimia, all I wanted to do was better myself, and I was in an environment that encouraged me to lose weight and be thin. I truly believed that if I lost weight I’d be a better dancer, and that was the most important thing in my life, the only thing I really cared about. So, not only my own perfectionism but also the environment in which I’d immersed myself were working together to put me at risk for developing an eating disorder.

When I ask members of my support groups whether there’s anyone else in their family with an eating disorder, I see a lot of people shaking their heads no. And then I ask, “Well, what about your aunt Suzy or uncle Bob, who will only eat particular foods, has peculiar eating habits or is exercising all the time?” and all of a sudden their eyes light up and hands go into the air.

Looking back on it now, I can see that not only eating disorders but also alcoholism, depression and anxiety run in my family. I remember being a little girl and visiting an aunt, my father’s sister, who worked for a large clothing store in Paris. She was petite and thin, and I recall her telling me that her secret to being skinny was to eat just one fast-food fish fillet sandwich a day. At the time, I didn’t think, Okay, I’m going to do that, but it did reinforce the idea that weight was an issue and that thinness was something to work for. And now, of course, I know that my aunt must have had some kind of eating disorder—or disordered eating—herself.

In addition to what I observed in my father’s family, my mother’s sisters have also struggled with poor body image and have always been extremely conscious of everything they ate. So, in fact, there were eating and body image issues on both sides of my family. For me, the genetic gun was definitely loaded and just waiting for the environmental circumstances that would pull the trigger. I really didn’t roll out of bed one morning and decide to be anorexic! And it’s important for your recovery to understand that neither did you.

Make That Information Work for You

So, now you know you probably have a genetic predisposition that contributed to your developing an eating disorder. Does that mean you should just sit back and use it as an excuse to keep on destroying your health and your life? Absolutely not!

Eating disorders don’t develop overnight, and getting better doesn’t happen overnight, either. Everyone slips and falls. But eventually those trips and falls become less and less frequent, and recovery becomes a reality.

Giving up the guilt is entirely different from giving yourself an excuse. Now that you know your eating disorder has biological/psychological/social roots, you can use that information to release any lingering feelings of guilt you might have and direct your energy toward doing what it’s going to take to recover. You just need to be aware that recovery isn’t going to be simple, because the problem itself is complex. There is no one single factor that caused your eating disorder, and there won’t be one single strategy that leads to recovery. I remember the mother of an amazing young woman in one of my groups saying that she simply couldn’t understand why her daughter still wasn’t getting better; she had taken her to see a psychiatrist, a psychologist, a nutritionist and a physician who specialized in treating eating disorders. To the mother’s mind, since she was doing all the right things, her daughter should have been showing drastic improvement. I said to that worried mom what I say to everyone in my support groups: eating disorders don’t develop overnight, and getting better doesn’t happen overnight, either. Everyone slips and falls and gets up, then maybe even trips and falls again. But eventually those trips and falls become less and less frequent, and recovery then becomes a reality. It takes time, and it’s a journey that doesn’t follow a straight path.

Конец ознакомительного фрагмента.

Текст предоставлен ООО «ЛитРес».

Прочитайте эту книгу целиком, купив полную легальную версию (https://www.litres.ru/johanna-kandel/life-beyond-your-eating-disorder-42515757/) на ЛитРес.

Безопасно оплатить книгу можно банковской картой Visa, MasterCard, Maestro, со счета мобильного телефона, с платежного терминала, в салоне МТС или Связной, через PayPal, WebMoney, Яндекс.Деньги, QIWI Кошелек, бонусными картами или другим удобным Вам способом.

Johanna Kandel

Тип: электронная книга

Жанр: Современная зарубежная литература

Язык: на английском языке

Издательство: HarperCollins

Дата публикации: 16.04.2024

Отзывы: Пока нет Добавить отзыв