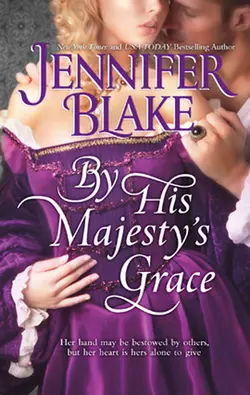

By His Majesty′s Grace

Jennifer Blake

The Three Graces of Graydon are wellborn sisters bearing an ominous curse: any man betrothed to them without love is doomed to die.Much to her chagrin, Lady Isabel Milton has been given to Earl Rand Braesford–a reward from the Tudor king for his loyalty to the throne. The lusty nobleman quickly claims his husbandly rights, an experience Isabel scarcely hoped to enjoy so much. But youth and strength may not save Braesford from his bride's infamous curse…Accused of a heinous crime with implications that reach all the way to King Henry himself, Braesford is imprisoned in the Tower, and Isabel is offered her salvation–but for a price. She has the power to seal his fate, have him sent to the executioner and be freed from her marriage bonds. Yet the more Isabel learns of Rand, the less convinced she is of his guilt, and she commits to discover the truth about the enigmatic husband she never expected to love.

Praise for

JENNIFER BLAKE

“Each of her carefully researched novels evokes a long-ago time so beautifully that you are swept into every detail of her memorable story.”

—RT Book Reviews

“Blake…has rightly earned the admiration and respect of her readers. They know there is a world of enjoyment waiting within the pages of her books.”

—A Romance Review

“Beguiling, sexy heroes… Well done, Ms. Blake!”

—The Romance Reader’s Connection

“Jennifer Blake is a beloved writer of romance—the pride and care she takes in her creations shines through.”

—Romance Reviews Today

“Guarded Heart is a boundlessly exciting and adventuresome tale…surely to be one of the best historical romances I will read this year.”

—Romance Junkies

“Blake’s anticipated return to historical romance proves to be well worth the wait.”

—A Romance Review on Challenge to Honor

By His Majesty’s Grace

Jennifer Blake

www.mirabooks.co.uk (http://www.mirabooks.co.uk)

To Bertrice Small and Roberta Gellis.

Many thanks, ladies,

for prodding me to write this story, for fun and

friendship at the 2008 Romantic Times convention

in Pittsburgh and, especially, for the warm welcome

into your medieval world.

Contents

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Author’s Note

Acknowledgments

1

August 1486

England

B raesford was finally sighted in late afternoon. It stood before them on its hill, a walled keep centered by a pele tower of massive proportions that loomed against the gray north sky. Rooks wheeled and called above the turret, soaring about its corbelled and battlemented walkway. A pennon topped it to show the master was in residence. That sturdy fabric of blue and white fluttered and snapped in the brisk wind as if trying to take flight.

Isabel Milton would have taken flight herself were it not so cowardly.

A trumpet sounded, indicating their permission to enter. Isabel shivered despite the late-summer warmth. Drawing a deep breath, she kicked her palfrey to a slow walk behind her stepbrother, the Earl of Graydon, and his friend Viscount Henley. Their mounted party approached Braesford’s thick stone walls with their ragged skirt of huts and small shops, clip-clopping over the dry moat, beneath the portcullis and through the gateway that gave onto a barmkin where the people of the countryside could be protected in time of trouble. Chickens flapped out of their way and a sow and her five pig-lets ran squealing in high dudgeon. Hounds flowed in a black-and-tan river down the stone steps of the open turret stairway just ahead. They surrounded the arriving party, barking, growling and sniffing around the horses’ fetlocks. Lining the way to the turret entrance was an honor guard of men-at-arms, though no host stood ready to receive them.

Isabel, waiting for aid to dismount, stared up at the great central manse attached to the pele tower. This portion was newly built of brick, three stories in height with corner medallions and inset niches holding terra-cotta figures of militant archangels. The ground floor was apparently a service area from which servants emerged to receive the baggage of the arriving party. The great hall, the heart of the structure, was undoubtedly on the second floor with the ladies’ solar directly above it, there where mullioned windows reflected the turbulent sky.

What manner of man commanded this fortress, which rose in such rugged yet prosperous splendor? What combination of arrogance and audacity led him to think she, daughter of a nobleman and an heiress in her own right, should wed a mere farmer, no matter how wide his lands or impregnable his home? What rare influence had he with the king that Henry Tudor had commanded it?

A shadow loomed inside the Roman arch of the turret doorway. The broad shape of a man appeared. He stepped out onto the cobblestones. Every eye in the bailey turned to fasten upon him.

Isabel came erect in her saddle as alarm banished her weariness from the long journey. She had been misled, she saw with tight dread in her chest, perhaps through ignorance but more likely from malice. Graydon was fond of such jests.

The master of Braesford was no mere farmer.

He was, instead, a warrior.

Randall Braesford was imposing in his height, with broad shoulders made wider by the cut of his doublet. The strong musculature of his flanks and legs was closely defined by dark gray hose and high boots of the same color. His hair was black, glinting in the pale sunlight with the iridescence of a raven’s feathered helmet, and worn evenly cropped just above his shoulders. His eyes were the dark silver-gray of tempered steel; his features, though well cast, were made somber by the firm set of his mouth under a straight Roman nose. Garbed in the refined colors of black, white and gray, he had not the faintest hint of court dandy about him, no trace of damask or embroidery, no wide-brimmed headgear set with plumes. His hat was simple, of gray wool with an upturned brim cut in crenellations like a castle wall. From the belt at his lean waist hung his knife for use at table, a fine damascene blade marked by a hilt and scabbard with tracings of silver over its black enamel.

It was no wonder he was a close companion to the king, she thought in fuming ire. They were two of a kind, Henry VII and Sir Rand Braesford. Though one was fair and the other dark, both were grave of feature and mien, forbidding in their strength and obvious determination to bend fortune to their will and their pleasure.

At her side, Viscount Henley, a veritable giant of a man on the downside of forty, with sandy hair and the battered countenance of those who made a pastime of war and jousting, swung down from his courser. He turned toward Isabel as if to assist her dismount.

“Stay,” Rand Braesford called in the firm command of those accustomed to being obeyed. He advanced upon her, his stride unhurried, his gaze keen. “The privilege is mine, I believe.”

An odd paralysis gripped Isabel while a hollow sensation invaded her midsection. She could not look away from Braesford’s dark eyes, not even when he paused beside her. They were so very black, with shimmering depths that beckoned yet defended against penetration. Anything could be hidden there, anything at all.

“My lady?”

The low rumble of his voice had a vibrant undertone that seemed to echo inside her. It was as intimate and as possessive as his mode of address. My lady. Not milady, but my lady.

His lady. And why not? Soon she would be his indeed.

Aware, abruptly, that she was staring, she veiled her gaze with her lashes, unhooked her knee from her pommel and turned more fully toward him. He reached for her waist with hard hands, lifting her from the saddle as she leaned to rest her gloved hands on his broad shoulders. He braced with his feet set, drawing her against him so she slid slowly down his long length until the skirt of her riding gown was drawn up and crushed between them and her booted toes barely touched the ground.

Her breath caught in her chest. Her future husband had no softness about him anywhere. His body was so unyielding from his chest to his knees that it was more like steel armor than living flesh. The sensation was particularly evident in the area below his waist. She jerked a little in his grasp, her eyes wide and fingers clenched on his shoulders, as she recognized that heated firmness against the softness of her lower belly.

He cared not at all that she knew, or so it seemed. His appraisal was intent behind the thick screen of his lashes, which seemed to permit her the same right of inspection. His eyes, she saw, carried a gleam in their depths like honed and polished silver, and thick brows made dark slashes above them. Lines radiated from the corners, perhaps from laughter but more likely from staring out over far distances. His jaw was square and his chin centered by a shallow cleft. The firm yet well-molded contours of his mouth hinted at a sensual nature held steadfastly in check.

“Well, Braesford,” her stepbrother said with the rasp of annoyance in his voice.

“Graydon,” the master of the manse said over his shoulder in acknowledgment. “I bid you welcome to Braesford Hall. And would do so with more ceremony if not so impatient to greet my bride.”

The words were pleasant enough, but carried an unmistakable note of irony. Did Braesford refer, most daringly, to his appreciation for her as a woman? Did he mean he was otherwise barely pleased to make her acquaintance, or was it something more between the two men?

This knight and her stepbrother had known each other during the Lancastrian invasion of the previous summer that had ended at Bosworth Field. Braesford had earned his spurs there, becoming Sir Randall Braesford. It was he who had found the golden circlet lost by the usurper, Richard III, and handed it to Lord Stanley so Henry Tudor might be crowned on the battlefield. Graydon, by contrast, had come away from Bosworth with nothing except the new king’s displeasure ringing in his ears for his delay in bringing up his men. Braesford no doubt knew that her stepbrother had waited until he was sure where victory would fall before lending support to Henry’s cause.

Graydon, in keeping with his dead father before him, preferred always to be on the winning side. Right was of little importance.

“A brave man, you are, to lay hands on my sister. I’d think you’d want her shriven first.”

Isabel stiffened at the suggestion. Her future husband did not spare her stepbrother so much as a glance. “Why would I do that?” he asked.

“The curse, Braesford. The curse of the Three Graces of Graydon.”

“I have no fear of curses.” Rand Braesford’s eyes lighted with silvery amusement as he smiled into hers. “It will be done with, betimes, when we are duly wed and bedded.”

“So that’s the way of it, is it?” Graydon gave a coarse laugh. “Tonight, I make no doubt, as soon as you have the contract in hand.”

“The sooner, the better,” Braesford agreed with deliberation. Setting Isabel on her feet, he placed her hand upon his arm and turned to lead her into the manse.

It was a moment before she could force her limbs to move. She walked with her head high and features impassive, leaving behind the winks and quiet guffaws of the Graydon and Braesford men-at-arms with the disdain they merited. Inside, her mind was in shivering chaos. She had thought to have more time, had expected a few days of rest before she need submit to a husband. In a week, or possibly two, reprieve could easily appear. It was years since any man had dared brave the curse of the Three Graces, so long that she had come to depend on its protection. Why should Braesford be the one to defeat it?

He meant to prove it false by a swift home strike. It was possible he would succeed.

Turning to look back, Isabel instinctively sought the familiar face of her serving woman, Gwynne. One of her stepbrother’s men-at-arms had helped her from her mule and she was now directing the unloading of their baggage. That Gwynne had heard the exchange along with everyone else seemed clear from the concern in her wise old eyes that followed her and her future husband. An instant of communication passed between them, not an unusual thing as the woman had been her mother’s body servant and had helped bring her and her sisters into the world. Bolstered by Gwynne’s silent support, Isabel faced forward again.

The curse was a fabrication if Braesford but knew it, a thin defense created from superstition, coincidence and daring. It had been Isabel’s inspiration, begun in hope of some small protection for her two younger sisters that she had helped rear after their mother died. To guard them in all ways had been her most fierce purpose since the three of them had been left with a brutish, uncaring stepfather. She had feared Cate and Marguerite, so lovely and tenderly nubile, would be bedded immediately at fourteen, the age of legal marriage following betrothals made in their cradles. By fate and God’s mercy, the three of them had, between them, escaped from ten or twelve such marital arrangements without being joined in formal wedlock or losing their maidenheads. Disease, accident and the fortunes of internecine warfare had taken the lives of their prospective grooms one by one. A malignant fate surely had them in its keeping—or so Isabel had suggested to all who would listen.

Mere whispers of it had served well enough for three or four years.

Then Leon, King Henry’s handsome Master of Revels, who had traveled with him from France the year before, had taken up the tale out of mischief not unmixed with kindness. Well, and for the challenge of seeing how many credulous English nobles he could persuade to believe it. Dear Gwynne had helped it along among the serving wenches and menservants at Westminster Palace. The supposed curse had become akin to holy writ, a universally believed truth that death or disaster must overcome any man who attempted a loveless union with any one of the Three Graces of Graydon—as Leon had styled them in token of the classical Roman fervor sweeping the court just now.

It had been a most convenient tale, regardless of the notoriety attached to it. As the eldest of the Graces, Isabel had been grateful for its protection. She had enjoyed the freedom it allowed, the endless days of peace with no one to order her except a stepbrother who was seldom at home. To be stripped of it through such an obvious misalliance as the one before her would be near unbearable. Yet how was she to prevent it?

The arm beneath the slashed sleeve of her future husband was as hard as the stone of his keep walls. Her fingers trembled a little on the dark wool that covered it, and she gripped tighter in the effort to still them. Did this man have none of the superstitious fear that ran rampant through those who prayed most mightily before every altar in the kingdom? Or was it only that he, like Henry VII, had known the Master of Revels in France?

Braesford glanced down at her with the lift of an inquiring brow. “You are cold, Lady Isabel?”

“Merely weary,” she said through stiff lips, “though the wind was somewhat chill for summer, especially during the last few leagues.”

“I apologize, but you will grow used to our rough weather in time,” he replied with grave courtesy.

“Possibly.”

“You think, mayhap, to escape it.” He led her into the tower, keeping his back to the curving wall as they mounted the narrow, winding treads so she might retain the support of his arm.

“I would not say that, but neither do I look forward to a long life spent at Braesford.”

“I trust you may change your mind before the night is done.”

She gave him a swift upward glance, searching the dark implacability of his eyes. He really meant to bed her before the evening was over. It was his right under canon law that recognized an official betrothal to be as binding as vows before a priest. Her heart stumbled in her chest before continuing with a more frantic beat. There must be some escape, though she could not think what it might be.

The staircase emerged in the great hall, a cavernous room with dark stone walls hung with banners and studded by stag horns. A dais lay at one end with musicians’ gallery above it, and trestle tables were spaced in a double row down its length. The mellow fragrance of fresh rushes mixed with lavender and cedar hung in the air from the newly laid carpet of them that softened the stone floor. Overlaying these was the wafting scent of wood smoke from the fire that burned low on the hearth of the huge fireplace against one wall, taking the dampness from the air. As they entered, menservants were already laying linen cloths for the company.

“You will wish to retire to your chamber before the feasting begins,” Braesford said as he surveyed the progress in the hall through narrowed eyes, then glanced back at the male company crowding in behind them. “I’ll see you to it.”

Dismay moved over Isabel. Surely he did not intend to join her there now? “You have far more important duties, I’m sure,” she said in some haste. “My serving woman and I can find our way.”

“No duty could ever be more important.”

Humor gleamed in the depths of his eyes, like light sliding along a burnished sword blade, though it was hidden as he inclined his head. Did he dare laugh at her and her fears?

In that moment, she was reminded of an evening at court some months ago, just after the announcement that Henry had agreed to marry Elizabeth of York. Isabel, like most unwed heiresses over the country, had been ordered to attend, though against Graydon’s wishes. There had been a great feast with dancing and disguising afterward. She had been dancing, moving through the figures of a ronde with a light heart and lighter feet, when a prickling awareness slid along her nerves. Glancing about, she noticed a gentleman leaning in the entrance to an antechamber. He had seemed set apart from the general merriment, grim of feature and dress, oddly vigilant. Yet a flash of silver appreciation had shone in his eyes for the space of a heartbeat. Then he had turned and vanished into the tunnellike gloom behind him.

That man, she realized now, had been Braesford. She had heard whispers of him about Henry’s court, a mysterious figure without family connections who came and went with no let or hindrance. He had endured Henry’s uncertain exile in Brittany and his later detainment in France, so they said, and was honored for that reason. Others whispered that he was a favorite of the new king’s lady mother, Margaret Beaufort, and had sometimes traveled between her and her son on missions that culminated in Henry’s invasion. No one could speak with accuracy of him, however, for the newly made knight remained aloof from the court and its gossip, occupying some obscure room in the bowels of whatever palace or castle Henry dwelled in at the moment. The only thing certain was that he had the king’s ear and his absolute trust. That was until he disappeared into the north of England, to the manse known as Braesford, which had been gifted to him for his services to the crown.

Was it possible, Isabel wondered in some perplexity, that her presence at Braesford, her betrothal to such a nonentity, sprang from that brief exchange of glances? It seemed unlikely, yet she had been given scant reason for it otherwise.

Not that there need be anything personal in the arrangement. Since coming to the throne, Henry had claimed her as his ward, given that her father and mother were dead, that she was unwed and heir to a considerable fortune. Graydon had raved and cursed, for he considered the right to manage her estate and its income to be his, though they shared not a drop of blood in common. Still, her stepbrother had been forced to bow to the will of the king. If Henry wanted to reward one of his followers with her hand and her property, including its munificent yearly income, that was his right. Certainly, she had no say in the matter.

Rand led Isabel Milton of Graydon from the great hall into a side vestibule and up the wide staircase mounted against its back wall. At the top, he turned to the left and opened a door leading into the solar that fronted the manor house. Glancing around, he felt the shift of pride in his chest. Everything was ready for his bride, though it had been a near thing. He had harried the workman with threats and not a few oaths to get the chamber finished in time. Yet he could not think Henry’s queen had a finer retreat.

The windows, with their thick, stacked circles of glass, gave ample light for the sewing, embroidery or reading of Isabel and her ladies. The cushioned benches beneath them were an invitation to contemplation or to observe what was taking place in the court below. The scenes of classical gods and goddesses painted on the plastered walls were enlivened with mischievous cherubim, while carpets overlaid the rushes here and there in a manner he had heard of from the Far East. Instead of a brazier, there was a fireplace in this room just as in the hall below. Settles of finely carved oak were drawn up on either side, their backs tall enough to catch the radiating heat with bench seats softened by embroidered cushions. A small fire burned against the advancing coolness of the evening, flickering beneath the massive mantelpiece carved with his chosen symbol of a raven and underlined by his motto in Latin: Interritusaum, Undaunted. Beyond it was the bed, resting on a dais fitted into the corner. As he was not a small man, this was of goodly size, and hung with sumptuous embroidered bed curtains, piled with feather-stuffed mattresses and pillows.

“Your solar, Lady Isabel,” he said simply.

“So I see.”

Rand had not expected transports of joy, but felt some word of appreciation might have been extended after all his preparations for her comfort. His disappointment was glancing, however, as he noted how she avoided looking at the bed. A faint tremor shook the hand that lay upon his arm, and she released him at once, drawing away a short distance.

She was wary of him, Rand thought. It could not be helped. He was not a superstitious man, put little credence in curses, prophecies and other such foretelling, yet neither did he leave things to chance. It was important that he take and hold Lady Isabel. He would do what was necessary to be sure of her and make his amends later.

And if holding her promised to be far more a pleasure than a duty, that was his secret.

“You will need to quench your thirst, I expect,” he said gravely. “I will send wine and bread to sustain you until the feasting.”

“That’s very kind. Thank you,” she said, speaking over her shoulder as she turned her back on him, moving farther away. “You may leave me now.”

Her tone was that of a princess dismissing a lackey. It grated, but he refused to take offense. No doubt she feared his attack at any moment, not that she lacked cause. It happened often enough with these alliances of great fortune, wherein to bed the lady was to take her virginity and her wealth in the same act. He thought briefly of living up to her expectations, of sweeping her into his arms and tossing her on the bed before joining her there. The surge of heat in the lower part of his body was a fine indication of what his more base self thought of the idea.

He could not do it. For one thing, being closeted with her for any length of time would expose her to more of the ribald, lip-smacking comment she had endured already. For another, forcing her was not a precedent he wanted to set for their life together.

Let her have her pride, then. She was in his power whether she accepted it or not. There would be time enough and more to see that she understood that fact.

“I regret that you were embarrassed just now,” he said abruptly.

“Embarrassed?” She turned to give him a quick glance from under her lashes. “Why should I be?”

“What may take place between us is not a matter for rough talk. I would not have you think I view it that way.”

Color as tender and fresh as a wild rose invaded her features. “Certainly not.”

“It’s only that there is bound to be speculation, considering the misfortune met with by your previous suitors.”

Between them lay the knowledge that he made the fifth in a line that had begun when she was in her cradle. The first was to a baron her father’s age who had expired of the colic. Afterward, the honor had descended to his son, a youth of less than six years who did not survive the childhood scourge of measles. A match had been arranged then with James, Marquess Trowbridge, a battle-scarred veteran of almost fifty. Trowbridge had been killed in a fall while hunting when Isabel was nine, after which she was pledged, at age eleven, to Lord Kneesall, merely seventeen years her senior and afflicted with a harelip. When he was executed after choosing the wrong side in the quarrel between Plantagenet factions, the betrothals halted.

This was in part, Rand knew, because the lady carried a reputation for being one of the accursed Three Graces of Graydon, sisters who could only be joined in wedlock to men who loved them. A more pertinent reason was the constant warfare of the past years which made selecting a groom problematical, given that the man chosen could be hale and hearty one day and headless the next.

The lady began to remove her gloves with meticulous attention to the loosening of each finger. Rand watched the unveiling of her pale hands with a drawing sensation in his lower body, his thoughts running rampant concerning other portions of her body that would soon be revealed to him. It was an effort to attend as she finally made reply.

“You can hardly be blamed for the vulgarity of others. My stepbrother, like his father before him, takes pleasure in his lack of refinement. Being accustomed to Graydon’s ways, I am unlikely to blush for yours.”

“Yet you flushed just now.”

She kept her gaze on what she was doing, carefully inching the leather off her little finger. “Not for the subject of the jest, but rather at having it raised between us.”

“So I am at fault,” he said evenly.

“There is no fault that I see.”

Her fairness touched him with an inexplicable tenderness, as did her courage and even her unconscious pride. She was a jewel there in that perfect chamber he had created for her, the final bright and shining addition. Her eyes were the soft green of new spring leaves, alive with watchful intelligence. Her lips were the rich, dark pink of the crusader’s rose that climbed the courtyard wall. Her mantle was a mere dust protector of russet linen, and her riding gown beneath it of moss-green summer wool. She had thrown back the cloak’s hood to reveal a small, flat cap of crimson wool embroidered with fern fronds, attached to which was a light veil that covered her hair so completely not the finest tendril of it could be seen. Rand’s hands itched, suddenly, to strip away that concealment, to strip her bare in truth, so he might see in full the prize he had been given.

“You relieve my mind,” he said, his voice harsh in his throat. “If the bedding others mentioned is in advance of the wedding, I trust you will understand the cause. The best way I know to dispel a curse is to disprove it.”

Her chin lifted another notch, though her lashes shielded her expression. “You will at least allow me to remove my cloak first?”

The vision his mind produced, of taking her in a welter of skirts and with her stocking-clad legs clamped around him, did such things to him that he was glad for the unfashionable length of his doublet. It would be so easy to manage since it was doubtful she wore braies of any description under her clothing, unless to prevent saddle soreness during her long ride. Moreover, her challenge sounded as if she might resent the necessity he claimed but would not fight him. That was promising, and fully as much as he had any right to expect.

She stripped away the glove she had loosened, but stopped with a gasp as her hand slid free of the soft leather. The color receded from her face and a white line appeared around her mouth.

Rand stepped forward with a frown, reaching to take her wrist in his hard fingers. “My lady, you are injured.”

A small sound somewhere between a gasp and a laugh rasped in her throat as both of them stared down at her little finger, which was bent at an odd angle between the first and second knuckle. “No…only a little.”

“It’s broken, obviously. Why was it not set?”

“There was no need,” she said, tugging on her arm in the attempt to free it from his grasp. “It’s nothing.”

Her skin was so fine, so soft under his calloused fingertips, that he was distracted for an instant, intrigued also by the too-fast flutter of her pulse under his thumb. “I can’t agree,” he answered. “It will heal in the shape it has taken.”

“That isn’t your concern.” She twisted her wrist back and forth, though she breathed quickly through parted lips and her eyes darkened with pain.

“Anything that touches upon my future wife is my concern.”

“Why, pray? Because you expect perfection?”

She meant to anger him so he would abandon her. It was clear she knew him not at all. “Because I hold myself responsible for your well-being from this day forward. Because I protect those close to me. Also, because I would know how best to serve you.”

“You will serve me to a nicety by leaving me in peace.”

She meant that literally, Rand thought. As granting that particular wish was impossible, he ignored the plea. “How did it happen? A fall? Were you thrown from your palfrey?”

“I was stupid, nothing more.”

“Were you indeed? I would not have thought it your habit.”

She refused to be drawn, pressing her lips together as if to withhold any explanation. The conviction came upon him that the injury might have been inflicted as a punishment. Or it might have been in the nature of persuasion, perhaps to cement her agreement to a match she considered beneath her.

He released her with an abrupt, openhanded movement. An instant later, he felt a constriction around his heart as she cradled her fingers with her other hand, pressing them to her midriff.

“I will send the local herb woman to you,” he said in gruff tones. “She is good with injuries.”

“So is the serving woman I brought with me. We will manage, I thank you.”

“You are quite certain?”

“Indeed.” The lady lifted her chin as she met his gaze. She let go of her mistreated hand and, with her good one, tucked the glove she had removed into the girdle of leather netting she wore across her hip bones.

He swung toward the door, setting his hand on the iron latch. “I will send your woman to you, then—along with your baggage and water for bathing. We dine in the hall at sundown.”

“As it pleases you,” she answered.

It didn’t please him, not at all. He would have liked to stay, lounging on the settle or bed while he watched her maid tend her. It would not do, not yet. He sketched a stiff bow. “Until later.”

Rand made his escape then, and didn’t stop until he was halfway down the stairway to the hall. His footsteps slowed, came to a halt there in that rare solitude. He turned and put his back to the wall, leaning his head against the cool stone. He would not go back. He would not. Yet how long the hours would be before the feasting was done and it was time for him and his betrothed to seek their bed.

How was he to bear sitting beside her, sharing a cup and plate, feeding her tidbits from the serving platters or their joint trencher, drinking where her lips had touched. Yes, and breathing her delicate female scent, feeling through linen and fine summer wool the slightest brush of her arm against his, the gentle entrapment of her skirts spreading across his booted ankles?

Ale, he needed a beaker of it. He required a veritable butt of ale immediately. Oh, but not, pray God, so much as to dull his senses. Not so much that he would disgust his bride with his stench. Certainly not enough to unman him.

Maybe ale was not what he needed, after all.

He could go for a long ride, except that he had no wish to be too tired for a proper wedding night. He could walk the battlements, letting the wind blow the heat from his blood while staring out over the valley, though he had done that far too often this day while waiting for his lady. He could descend to the kitchen to order some new delicacy to tempt her, though he had commanded enough and more of those already.

He could entertain his male guests, and hope it wasn’t necessary to stop their crude comments with a well-placed fist. And, just possibly, he could learn something from Isabel’s stepbrother that might tell him how strenuously she had objected to this marriage, and what had been done to her to assure her agreement.

What he would do with any knowledge gained was something he would decide when he had it.

2

I sabel emerged from the solar at the tolling of the Angelus bell. Her spirits were considerably improved after a warm bath to remove the dirt of travel, also the donning of a clean shift beneath a fine new gown of scarlet wool, the color of courage, with embroidery stiffening its hem and edging the slashed sleeves tied up at intervals with knots of ribbon. Sitting before the coals in the fireplace while Gwynne brushed her hair dry and put it up again under cap and veil had also given her time to reflect.

She had avoided being bedded at once by Braesford, though she could hardly believe it. Had he changed his mind, perhaps, or had the possibility never been anything more than Graydon’s low humor? She hardly knew, yet it was all she could do to contain her giddy relief. Pray God, her good fortune would continue.

It was not that she feared the intimacy of the marriage bed. She expected little joy from it, true, but that was a different matter. No, it was marriage in its entirety she desired to avoid. Too many of her friends had been married in their cradles, given to much older husbands at thirteen or fourteen, brought to childbed at fifteen or sixteen and mothers to three or four children by her own age of twenty-three. That was if they were not dead from the rigors of childbirth. Her own mother’s first marriage had been similar, though happy enough, possibly because Isabel’s father, Lord Craigsmoor, had spent much time away at court.

The second marriage of her mother’s had not fared so well. The sixth earl of Graydon had been brutal and domineering, a man who treated everyone around him with the same contempt he showed those attached to his lands. His word was law and he would brook no discussion, no disobedience in any form from his wife, his stepdaughters or his son and heir from a previous marriage. Many nights, Isabel and her two younger sisters had huddled together in their bed, listening while he beat their mother for daring to question his household rulings, spending too much coin on charity or denying him access to her bed. They had watched her turn from a smiling, animated woman into a pale and cowed shadow of herself, watched her miscarry from her beatings or deliver stillborn infants. It had been no great surprise when she failed to rally from one such birth. The saving wonder had been that the monster who was her husband had been killed in a hunting accident not long afterward.

No, Isabel wanted no husband.

Yet to defy Braesford would avail her nothing and might anger him to the point of violence, as it did her stepbrother, who had been formed in his father’s image. Her only weapons, if she was to escape what the night had in store, were patience and her God-given wits. What manner of good they might do her, she could not guess. The pain of her broken finger was a flimsy excuse at best. More, Braesford seemed all too likely to press for how she had come by it. To admit her stubborn refusal to agree to the marriage was the cause could not endear her to him. She might claim the onset of her monthly courses but had no certainty that would deter him. A vow of celibacy would give him pause, though only long enough to reason that she would not have been sent to him had it been binding.

No, there had to be something else, something so immediate and vital it could not be ignored. Now, she thought with conscious irony, would be a fine time for the curse of the Three Graces of Graydon to make its power felt.

In truth, she feared nothing would stop Braesford from possessing her. So many women must have prayed for escape from these entrapments, most to no avail. It was fated that those of her station should become the pawns of kings, moved at the royal will from one man to another, and all their tears and pleas changed that not a whit. The most Isabel could do was to make herself agreeable during the feasting while watching and waiting for a miracle. And if it did not occur, she must endure whatever happened in the bed of the master of Braesford with all the dignity she could command.

To retrace the way to the great hall was not difficult. She had only to follow the low rumble of male voices and smell of tallow candles, smoke from kitchen fires and the aroma of warm food. She had sent Gwynne ahead to see to the table arrangement made for her in what appeared to be primarily a male household. Female servants abounded, of course, but there seemed to be no woman serving as chatelaine—no mother, sister or wife of a trusted friend. Nor, if Gwynne was correct, was there a jade accustomed to warming the master’s bed and giving herself airs of authority, though Isabel was not entirely sure that was the blessing her serving woman claimed. A man used to bedding a mistress might not have such rampant need of a wife.

As she neared the head of the stairwell, a shadow moved in the far end of the dark corridor. The shape grew as it neared the flaring torch that marked the stairwell, taking on the form of her stepbrother. He had just emerged from the garderobe, or stone-lined latrine, that was let into the thickness of the end wall. Square built and heavy with a lumbering gait, he had a large head covered to the eyebrows with a thatch of rust-brown hair, a beard tinted orange-red and watery blue eyes. As he walked, he adjusted his codpiece between the parti-colored green-and-red legs of his hose, prolonging the operation beyond what was necessary when he caught sight of her. The odor of ale that preceded him was ample proof of how he had spent the time since their arrival. His lips were wet, and curled at one corner as he caught sight of her.

Tightness gripped her chest, but she refused to be distressed or deterred. “Well met, Graydon,” she said softly as he came closer. “I hoped to speak to you in private. You were quite right, the master of Braesford doesn’t intend to wait for our vows, but to try me like a common cowherd making certain his chosen bride is fertile.”

“What of it?”

“I would be more comfortable having the blessing of the priest first.”

“When will you learn, dear sister, that your comfort doesn’t matter? The cowherd is to be your husband. Best get used to it, and to the bedding.”

“Isn’t it insulting enough that I must be thrown away on a nobody? You could speak to him, insist he wait as a gesture of respect.”

“Oh, aye, if it was worth running afoul of one who has the king’s ear. You’ll do as you’re bid, and there’s an end to it. Unless you’d like another finger with a crook in it?”

He grabbed for her hand as he spoke, bending her little finger backward. Burning pain surged through her like the thrust of a sword. Her knees gave way. She went to the stone floor in front of him in a pool of scarlet wool, a cry stifled in her throat.

“You hear me?” he demanded, bending over her.

“Yes.” She stopped to draw a hissing breath. “I only…”

“You will spread your legs and do your duty. You will be honey-mead sweet, no matter what he asks of you. You will obey me, or by God’s blood I’ll take a stick to your—”

“I believe not!”

That objection, delivered in tones of slicing contempt, came from a stairwell nearby. A dark shadow rose over the walls as a tall figure mounted the last two stair steps from the hall below. An instant later, Graydon let go of her hand with a growled curse. He fell to his knees beside her. Behind him stood Rand Braesford, holding her stepbrother’s wrist twisted behind his back, pressed up between his shoulder blades.

“Are you all right, my lady?” her groom inquired in tight concern.

“Yes, yes, I think so,” she whispered without looking up at him, her gaze on his dark shadow that was cast across her, surrounding her on the floor where she knelt.

Braesford turned his attention to the man he held so effortlessly in his hard grasp. “You will extend your apology to my lady.”

“Be damned to you and to her—” Graydon halted with a grunt of pain as his arm was thrust higher.

“At once, if you value your sword arm.”

“By all that’s holy, Braesford! I was only doing your work for you.”

“Not mine, not ever. The apology?”

Graydon’s features contorted in a grimace that was half sneer, half groveling terror as his shoulder creaked under the pressure Braesford exerted. He breathed heavily through set and yellowed teeth. “I regret the injury,” he ground out finally. “Aye, that I do.”

Rand Braesford gave him a shove that sent him sprawling. Her stepbrother scuttled backward on his haunches until he struck the wall. He pushed to his feet, panting, his face purple with rage and chagrin.

Isabel’s future husband ignored him. He leaned to offer his aid in helping her to her feet. She lifted her eyes to his, searching their dark gray depths. The concern she saw there was like balm upon an old wound. Affected by it against her will, she reached out slowly to him with her good hand. He enclosed her wrist in the hard, warm strength of his grasp and drew her up until she stood beside him. He steadied her with a hand at her waist until she gained her balance. Then he let her go and stepped back.

For a stunned instant, she felt bereft without that support. She looked away, glancing toward where Graydon stood.

He was no longer there. Fuming and cursing under his breath, he retreated down the stairs, his footsteps stamping out his enraged withdrawal.

“Come,” Braesford said, guiding her back toward her solar with a brief touch at her back, “let me have a look at that finger.”

She went with him. What else was she to do? Her will seemed oddly in abeyance. Her finger hurt with a fierce ache that radiated up her arm to her shoulder, making her feel a little ill and none too steady on her feet. More than that, she had no wish to face Graydon just now. He would blame her for the humiliation at Braesford’s hand, and who knew what he might do to assuage his injured conceit.

Braesford’s features were grim as he closed the two of them into the solar again. Turning from the door, he gestured toward a stool set near the dying fire. She moved to drop down upon it and he followed behind her, dragging an iron candle stand closer before going to one knee in front of her. His gaze met hers for a long instant. Then he reached to take her injured hand in his and place it carefully, palm up, on his bent knee.

An odd sensation, like a small explosion of sparks from a fallen fire log, ran along her nerves to her shoulder and down her back. She shivered and her hand trembled in his hold, but she declined to acknowledge it. She concentrated, instead, on his features so close to her. Twin lines grooved the space between his thick brows as he frowned, while the black fringe of his lashes concealed his expression. A small scar lay across one cheekbone, and the roots of his beard showed as a blue-black shadow beneath his close-shaved skin. An odd breathlessness afflicted her, and she inhaled deep and slow to banish it.

He did not look up, but studied her little finger, following the angle of the break with a careful, questing touch, finding the place where the bone had snapped. He added his thumb, spanning the injured member between it and his forefinger. Gripping her wrist in his free hand, he caught the slender, misshapen digit in a grip of ruthless power and gave it a smooth, hard pull.

She cried out, keeling forward in such abrupt weakness that her forehead came to rest on his wide shoulder. Sickness crowded her throat and she swallowed hard upon it, breathing in rapid pants. Against her hair, she heard him whisper something she could not understand, heard him murmur her name.

“Forgive me, I beg,” he said a little louder, though his tone was quiet and a little gruff. “I would not have hurt you for a king’s ransom. It was necessary, or else your poor finger would always have been crooked.”

She shifted, moved back a space to stare down at their joined hands. Slowly, he unfurled his grasp. Her little finger no longer had a bend in it. It was straight again.

“You…” she began, then stopped, unable to think what she meant to say.

“I am the worst kind of devil, I know, but it seemed a shame that such slender, aristocratic fingers should appear imperfect.”

She would not deny it, was even grateful in a way. What she could not forgive was the lack of warning. Yes, and lack of choice. She had been offered so little of late.

He did not wait for her comment but turned to survey the rushes that covered the floor behind him. Selecting one, he broke its stem into two equal lengths with a few quick snaps. He fitted these on either side of her finger, and then reached without ceremony to slip free the knotted silk ribbon which held her slashed sleeve together above her left elbow. Shaking out the shining length, he wrapped it quickly around his makeshift splint.

Isabel stared at his bent head as he worked, her gaze moving from the wide expanse of his shoulders to the bronze skin at the nape of his neck where the waving darkness of his hair fell forward away from it, from his well-formed fingers that worked so competently at his task to the concentration on his features. His face was gilded by candlelight, his sun-darkened skin tinted with copper and bronze, the bones sculpted with tints of gold while the shadows cast upon his cheekbones by his lashes were deep black in contrast.

A strange, heated awareness rose inside her, the piercing recognition of her response to his touch, his inherent strength, his sheer masculine presence. They were so very alone here in the solar with the gathering darkness pressing against the thick window glass and only a single branch of guttering candles for light. She had few defenses against whatever he might decide to do to her in the next several minutes, and no expectation of consideration at his hands.

Husband, he was her husband already under canon law, with all the privileges that entailed. Would he be tender in his possession? Or would he be brutish, taking her with all the ceremony of a stag mounting a hind? Her stomach muscles clenched as molten reaction moved lower in her body. A shudder, uncontrollable in its force, spiraled through her.

Braesford glanced up as that tremor extended to the fingers he held. “Did I hurt you?”

“No, no,” she said, her voice compressed in her tight throat. “I just… I should thank you for coming to my aid. It was fortunate you arrived when you did.”

“Fortune had no part in it,” he answered, returning his gaze to the small, flat knot he was tying in the ribbon. “I was coming to escort you to the hall.”

“Were you?” Her wonder faded quickly. “I suppose you felt we should make our entrance together.”

“I thought you might prefer not to face the company alone. As there will be no other lady present, no chatelaine to make you comfortable, then…” He lifted a square shoulder.

“It was a kind thought.” She paused, went on after a moment, “Though it does seem odd to be the only female of rank.”

“I have no family,” he said, a harsh note entering his voice. “I am the bastard son of a serving maid who died when I was born. My father was master of Braesford, but acknowledged me only to the extent of having me educated for the position of his steward. That was before his several estates, including Braesford, were confiscated when he was attainted as a traitor.”

Isabel tipped her head to one side in curiosity. “Traitor to which king, if I may ask?”

“To Edward IV. My father was loyal to old King Henry VI, and died with two of my half brothers, two out of his three legal heirs, while trying to restore him to the throne.”

“You followed in his footsteps, being for Lancaster?” She should know these things, but had barely listened to anything said about her groom after the distress of being told she must wed.

“Edward cut off my father’s head and set it on Tower Bridge. Was I to love him for it? Besides, he was a usurper, a regent who grew too fond of power after serving in his uncle’s place when he became a saintly madman.”

Her own dead father had sworn fealty to the white rose of York, but Isabel held the symbol in no great affection. Edward IV had stolen the crown from his pious and doddering uncle, Henry VI, and murdered him to prevent him from regaining it. He’d also executed his own brother, Clarence, for treason in order to keep it. When Edward died, his younger brother, the Duke of Gloucester, had declared Edward’s young sons and daughters illegitimate and taken the crown for himself as Richard III. Rumor said he had ordered the two boys murdered to prevent any effort to restore them to the succession. Mayhap it was true; certainly they had disappeared. Now Henry Tudor had defeated and killed Richard III at Bosworth Field, becoming King Henry VII by might as much as right. He had also married Elizabeth of York, eldest daughter of Edward IV, thus uniting the red rose of Lancaster with the white rose of York, ending decades of fighting.

So much blood and death, and for what? For the right to receive the homage of other men? For the power to take what they wanted and kill whom they pleased?

“And the present Henry is wholly deserving of the crown he has gained?” she inquired.

“Careful, my lady,” Braesford said softly. “Newly made kings are more sensitive to treasonous comments than those accustomed to the weight of the crown.”

“You won’t denounce me, I think, for that would mean the end of a marriage greatly to your advantage. Besides, I would not speak so before any other.”

He met her gaze for long seconds, his own darkly appraising before he inclined his head. “I value the confidence.”

“Of course you do,” she said in short rejoinder. Few men bothered to listen to women in her experience, much less attend to what they said.

“I assure you it is so. Only bear in mind that in some places the very stones have ears.” He went on with barely a pause. “In any case, Henry VII is the last of his blood, the last heir to the rightful king, being descended on his mother’s side from John of Gaunt, grandfather to Henry VI. With all other contenders executed, dead in battle or presumed murdered, he has as much right to the crown as any, and far more than most.”

“Descended from an illegitimate child of John of Gaunt,” she pointed out.

His smile turned crooked, lighting the gray of his eyes. “Spoken like a true Yorkist. Yet the baseborn can be made legitimate by royal decree, as were the children of John of Gaunt by Katherine Swynford, not to mention Henry’s new consort, Edward IV’s daughter, Elizabeth. And as with the meek, they sometimes inherit the earth.”

“Do you speak of Henry,” she said after an instant of frowning consideration, “or mean to say that you inherited your father’s estates, as he was once master at Braesford?”

“I was awarded them, rather, for services rendered to Henry VII. Though I promise you I earned every hectare and hamlet.”

“Awarded a bride, as well,” she said with some asperity.

Rand tipped his head. “That, too, by God’s favor, as well as Henry’s.”

The former owner of Braesford, if she remembered aright, was named McConnell. Being baseborn, Rand had taken the name of the estate as his surname, identifying himself with the land rather than with his father. It was a significant act, perhaps an indication of the man. “I was told the reward was, most likely, for finding the golden circlet lost by Richard in a thornbush at Bosworth. Well, and for having the presence of mind to hand it to Lord Stanley with the recommendation that he crown Henry on the field.”

“Don’t, please, allow the king’s mother to hear you say so.” A wry smile came and went across his face. “She believes it was her husband’s idea.”

Henry’s mother, Lady Margaret, was married to Lord Stanley, Earl of Derby, as everyone knew. Though she had set up her household at Westminster Palace with her son, living apart from her husband by mutual consent, she was yet protective of Stanley’s good name.

“It was the reason, nonetheless?” Isabel persisted.

“Such things come, now and then, from the gratitude of kings.”

His voice was satirical, his features grim, almost forbidding. He was not stupid by any means, so well knew the fickle nature of royals who could take away as easily as they gave.

Yet receiving the ripe plum of a fine estate that had once belonged to a traitor was not unusual. The late bloodletting, named by some troubadour as the War of the Roses, had gone on so long, its factions had shifted and changed so often with the rise and fall of those calling themselves king, that titles and estates had changed hands many times over. A man sitting at the king’s table today, lauded as a lord and dressed in ermine-lined velvet, could have an appointment with headsman or hangman tomorrow. Few so favored died in their beds.

She noted, of a sudden, that Braesford seemed to be avoiding her gaze, almost ill at ease as he smoothed a thumb over the rush stems of her splint as if checking for roughness. Disquiet rose inside her as she wondered if he had overheard what she’d said of him moments ago. Clearing her throat, she spoke with some discomfiture. “If it chances you were near enough to overhear what passed between me and my stepbrother just now—”

He stopped her with a slicing gesture. “It doesn’t matter. You were quite right. I am nobody.”

“You were knighted by Henry on the battlefield,” she replied with self-conscious fairness as heat rose to her hairline. “That stands for something.”

“So it does. Regardless, I will always be a nobody to men like your brother who were born to their honors.”

“My stepbrother,” she murmured in correction.

“Your true father, your mother’s first husband, was an earl, as well. You, therefore, share this birthright of nobility.” He glanced up suddenly, his eyes as hard as polished armor. “You will always be Lady Isabel, no matter what manner of man you marry.”

“For what good it may do me. But the lands you have been given will provide sufficient income to maintain a place at court, one from which you may gain more honors.”

He shook his head so firmly that the candlelight slid across the polished ebony strands of his hair in blue and yellow gleams. “I will always be the mere steward of this estate in some sense, a farmer at heart with little use for Henry’s court and its intrigues. I want only to live in this manse above its green valley. Abide with me here, and I swear that you and your aristocratic fingers will be forever safe from injury, including that from your husband.”

It was a promise well calculated to ease the fear in her heart. And so it might have if Isabel had dared trust in it. She did not, as she knew full well that oaths given to women were never so well honored as those sworn between men.

Removing her fingers from his grasp, she got to her feet. “I will be glad of your escort below, for now.”

If he was disappointed, he did not show it. He rose to his feet with lithe strength and offered his arm. Together, they descended to the wedding feast.

The hall blazed with light from wicks set afloat in large, flat bowls perched upon tripods. The double line of trestle tables led toward the low wooden dais that held the high table with its huge saltcellar. The alcove behind it was wainscoted with whitewashed wood and painted with allegorical scenes in the tall reaches above the paneling. A pair of chests set with silver plate flanked the great stone fireplace that soared upward. Above them hung bright-colored banners, swaying gently in the rising heat.

The men-at-arms that lounged on the benches drawn up to the tables numbered thirty at most. It was not a large force; that brought by Isabel’s stepbrother for protection on the journey northward was half again as large. Between the two complements, however, the room seemed overfull of men in linen, wool and velvet.

Their voices made a bass rumble that ceased abruptly as Braesford appeared with her on his arm. With a mighty scraping and rustling, they came to their feet, standing at attention. Silence stretched, broken only by a cough or low growl from one of the dogs that lay among the rushes beneath the trestles, as the two of them made their way to the high table.

Isabel flushed a little under such concentrated regard. Glancing along the ranked men, she caught open speculation on the features of one or two. They believed dalliance in the privacy of her solar had delayed her arrival, particularly after Graydon’s comments in the courtyard. It made no difference what they might think, of course, yet she despised the thought of the images sure to be passing through their heads.

Braesford seated her, then released the company to their own benches with a gesture. The meal began at once as servants came forward to fill beakers, lay trenchers from great baskets of the bread slabs and ladle onto these a savory concoction of sweetmeats flavored with spices, chopped vegetables and cubed bread soaked in broth.

Isabel put out her hand toward the wine goblet that sat between her place and that of her future husband, but immediately drew it back. Sharing a place with one of her younger sisters, as she usually did, it was her right as eldest to drink first or offer the wine, as she chose. Now that she shared Braesford’s table setting, this was his privilege.

He noticed her movement, as he seemed to notice most things. With a brief, not ungraceful gesture of one hand, he made her free of the goblet. She took it up, sipped gingerly.

The wine was new, raw and barely watered, so went down with difficulty past the tightness in her throat. That first taste was enough to let her know she could not face food. The smell of it, along with wood smoke, hot oil from the lamps and warm male bodies in stale linen, brought back her earlier illness. It would be enough, she hoped, to merely pretend to eat. The last thing she wanted was to appear to spurn Braesford’s hospitality. Meanwhile, manners and common sense dictated that she converse with her future husband, to establish some semblance of rapport that might yet serve her in avoiding intimacy this night.

She could think of nothing to say. Soon enough the feasting would be over, and what then? What then?

“My lady?”

Braesford was offering her a succulent piece of roast pork, taken from the large, golden-brown trencher set on a silver salver between them. She glanced at it on the razor-sharp tip of his knife, met his dark eyes an instant, then looked away again. “I…couldn’t. I thank you, sir, but no.”

“A little crust, then, to go with the wine.” Taking the meat from the knifepoint himself with a flash of white teeth, he carved off a piece of their trencher and held it out to her.

She took the bread, nibbled at it and sipped more wine. Even as she lifted the goblet to her lips, however, she realized she was monopolizing it when it must be shared between them. Wiping the rim hurriedly with the edge of the tablecloth draped over her lap for that purpose, she pushed the goblet toward him.

“Your finger pains you,” he said, his gaze on what she was doing. “I’m sorry. There is a woman in the village, as I told you before, a healer who can make an infusion of willow bark, which might be useful. I’ll send for her at once.”

“Please don’t concern yourself.” She lowered her lashes. “A night of rest will be sufficient, I’m sure.”

“Will it, now? And I imagine two nights, or even three or four, would be better.”

“Indeed, yes,” she began eagerly, but halted as she looked up to catch the silver shading of irony in his eyes, the tightening at the corner of his firmly molded mouth.

“Indeed,” he repeated, putting out his hand for the wine goblet, rotating it in a slow turn and drinking from where she had sipped. “Did you never notice that the things you dread are seldom as bad as feared once they are behind you?”

“No,” she said with precision.

“It’s so, I promise. No doubt the reflection will prove a solace in the morning.”

He reached to take her good wrist, removing the bread slice she had been toying with and dropping a light kiss on her knuckles before popping the crust into his mouth. She sat quite still, feeling the warm, tingling imprint of his lips on her hand, shivering a little as it vibrated through her, watching in peculiar wonder the movement of his jaw muscle as he chewed and swallowed.

“God’s blood, Braesford,” Graydon called from his place near the dais with Viscount Henley next to him. “’Tis a habit you caught in France, I don’t doubt, kissing a lady’s hand. An Englishman can think of more interesting places to put his mouth to work.”

Henley, being somewhat less coarse than her stepbrother, coughed and ducked his head rather than joining in the scattered guffaws. His face turned scarlet, regardless, in reaction to the lewd suggestion.

“But not, I think, at table,” Braesford answered Graydon, before his tone hardened and he speared Henley and the rest of the company with a look, “and not while thinking of my lady.”

Quiet descended, free even of the thump of ale beakers hitting the trestles. In it, the nervous uncertainty in Graydon’s snort was plainly heard. Isabel felt suddenly sorry for her stepbrother, reprimanded twice by Braesford in the space of an hour. Though she had endured countless variations on his lewd wedding humor during the past days, had longed fervently for someone to shut his mouth for him, she could not enjoy his discomfiture.

“Aye, no disrespect intended,” Graydon muttered. Henley rumbled a similar answer, as did half a dozen others along the boards.

Braesford drank a mouthful of wine and set down the goblet. “I trust not. Her honor is mine now, therefore must be protected by my sword.”

“Oh, aye, as it should be,” her stepbrother agreed. “Pious Henry would have it no other way, seeing as he gave her to you.”

“And I value his gifts above diamonds, plan always to hold them firmly in my grasp.”

Her future husband turned his head to meet her gaze as he spoke. What Isabel saw there made her draw a sharp breath. Then she reached for the wine goblet he still held, taking it from him in her two hands before draining it to the dregs.

The meal continued with all manner of dishes, requiring three removes of the cloths covering the tables as they became too soiled for use. Beyond the usual pottages flavored with spices, they were served meat pies, vegetables dressed with vinegar and simmered in sauces, oysters served in various ways, great platters of roast piglet, snipe, lark tongues and even a swan roasted, then clad again in its feathers. The master of Braesford had gone to great lengths to gather such victuals for his bride and honored guests, but Isabel refused to be impressed, just as she ignored the trio of musicians who played from the gallery above her, the dancers who twirled around the tables, the jugglers and mimes who made the men laugh. She was used to such things at court for one thing, but also knew well that ample feasting and merriment often had more to do with status than the appeasement of anyone’s hunger or the need to be entertained.

It was some time later that the melodious salute of a trumpet sounded above the clatter and merriment. The signal indicated someone of importance approaching Braesford’s outer gate.

The tune played by lute and harp trailed into silence. Voices stilled. Everyone turned toward the entrance doors. The commander of Braesford’s men-at-arms rose from a nearby table. He nodded at a half-dozen men and left the hall in their company.

“You are expecting visitors?” Isabel asked in quiet tones as she leaned toward her future husband.

“By no means, but don’t be distressed. It can be nothing of import.”

He suspected a neighboring landowner and his men on local business, mayhap, or else a latecomer to the feast. Still, she knew as well as he did that it could also be a command to join the king’s army, to ride out to control some uprising or defend a border. Only a mounted troop or king’s herald would have triggered the trumpet salute of warning.

They had not long to wait. The clatter of hooves on the stones of the inner court and the jingling of tack came faintly to where they sat. Booted feet sounded upon the tower stairs. Serving men threw open the doors, allowing a cadre of soldiers under the king’s red-dragon banner to march inside. They tramped down the open area between the trestles until they reached the high table. The order to halt rang out and their commanding officer stepped forward, saluting with a mailed arm and gloved fist.

Braesford came to his feet with a frown between his dark brows. “Welcome, William, as always, though I thought you settled at Westminster. What brings you this far north?”

“The order of the king.” The man addressed as William pulled a paper from the pouch at his side and passed it across the width of the high table to Braesford.

Isabel recognized the newcomer as William McConnell, a man she had seen about the court. Turning over his name, studying his features and something of his manner, she felt the stir of presentiment. He was similar in size and feature to Rand, though McConnell’s hair was more badger brown than black, the jut of his nose less bold and his eyes brown rather than gray. Recalling, abruptly, some whispered comment heard more than a year ago, she realized this was Braesford’s remaining half brother, the third of three, he who had once thought to inherit the hall where she sat until it was forfeited after their father was executed.

“What is it?” Braesford asked, accepting the roll of parchment, unfurling it so the great seal of the king appeared, impressed into wax as red as blood.

“An unpleasant errand, in all truth.” McConnell directed his gaze somewhere above the high table, upon his family banners that hung there.

“Aye, and that would be?”

His half brother cleared his throat with a rasp, speaking in a voice that reached into the most distant corners of the room. “Randall of Braesford, you are charged with the crime of murder in the death of the child born these two months past to Mademoiselle Juliette d’Amboise. By command of His Royal Majesty, King Henry VII, you are directed to leave within the hour for London, in company with your affianced wife, Lady Isabel of Graydon. There, you will appear before the King’s Court on the charge lodged against you.”

Murder. The heinous murder of a child. Isabel sat unmoving, so mired in disbelief she could hardly take in the implications of the charge.

Even so, three things were blindingly obvious to her.

There would be no night spent in the bed of the master of Braesford, not if she was to leave with him at once for London.

There might never be a wedding if he was convicted of the murder.

The curse of the Three Graces of Graydon had not failed.

3

F ury ran like acid through Rand’s veins. It striped his thought processes to such a sharp and raw edge that he was able to order the packing of supplies for his men and his guests, to direct the continued operations for the manse and the coming harvest, all while mentally cursing his king who was also his friend. Or who had once been his friend, in the days of their exile.

What in God’s sweet heaven was Henry about with this charge of murder of an innocent? Mademoiselle Juliette d’Amboise’s newborn babe, a small mite with Juliette’s full-lipped mouth and Henry’s pale blue eyes, had been in rosy health when Rand last saw her. He had stood sentinel on the keep wall as little Madeleine, as Juliette had named her, left Braesford Hall with her mother. Henry himself had sent an armed troop to see his mistress to a place of quiet seclusion, so must know full well the baby had not been harmed.

Henry was a secretive man, and who could blame him? When only four years old, he had been taken from his mother and placed in the custody of a sympathizer of the Duke of York. Being fostered in a family not his own was common for the scion of a noble house, as it was thought to promote independence and allow instruction in the art of war without any weakening favoritism, but this was the house of the enemy. Henry had escaped that imprisonment when his doddering cousin, Henry VI, briefly regained the throne from the Yorkists under Edward IV, but was forced to ride for his life when the aging king was murdered. He, with his uncle, Jasper Tudor, barely reached the coast and took ship for France ahead of Edward’s forces—who would certainly have killed him, as well.

Blown off course, Henry and Jasper landed in Brittany, where their fate hung in the balance as the Duke of Brittany made up his mind whether more political advantage could be gained from keeping them as his nominal guests or turning them over to their enemies. For the next fourteen years, that cat-and-mouse game had played itself out, with Louis XI of France sometimes taking part in it before his death. Henry had been heard to say that he had been either hunted or in captivity for most of his life. Was it any wonder that he had grown as devious as those who surrounded him?

Understanding could not persuade Rand to overlook the unwarranted interference in his nuptials and his life. He railed against it, cursing the timing and implied threat. He suspected Henry had changed his mind about giving him Lady Isabel. It was always possible the king had discovered a more worthy husband for her, one who would bring greater advantage to the crown.

It was damnable. More than that, Rand objected strenuously to being hung so the lady might be free. He meant to guard against convenient accidents that could remove him, as well; he had insisted that his own men-at-arms must join the king’s men, and Graydon’s, on this ride to London.

Now he sat his gray destrier, Shadow, in brooding silence. Flanked on one side by his squire, David, a blond and blue-eyed young valiant, and on the other by his own restless soldiery, he watched Lady Isabel emerge from the tower into the court. She appeared pale but resolute in the flare of torchlight, with the hood of her cloak drawn forward, half concealing her face. She was gloved, Rand saw, but the leather was cut away from the injured finger of her left hand.

His splint still held it in place. It gave him an odd satisfaction to see it.

She had not wanted to be wed, had been coerced in the most brutal fashion to accept the match, forced to ride north to Braesford for the marriage. He might have known. She was the daughter of an earl, after all. Why should she be wed to a bastard knight? It was a disparagement to her high birth under the rights granted to nobles by the Magna Carta. She should have been allowed to refuse, might have done so if not for her stepbrother’s threats.

A nobody, she had named him.

She had it aright; still, Rand seethed as he recalled that pronouncement in her clear, carrying voice. He was more of a personage now than he had been born to expect, had earned land and honors by his own hard effort. He would have more yet. And when it was gained, he would lay it at her feet and demand her apology, her recognition of his worth and her surrender.

Ah, no.

He would be lucky if he came out of this business with his life. Whatever he was to have of the lady, it must be soon. Otherwise, he might have nothing of her at all.

A horseshoe struck stone as William McConnell, his half brother, reined in close beside him. “A worthy bride,” he drawled as he followed Rand’s hot gaze. “You almost managed to have her, too.”

“You could have allowed departure in the morning, so I might have come to know her better.”

“In the biblical fashion, therefore completely? A great pity, that lack of opportunity, but I have my orders.”

“And you don’t object to carrying them out.”

Implicit between them was the knowledge that William had coveted Isabel for himself. He had sighed after her the winter before while cursing his lack of favor with Henry that might have earned him her hand and her fortune. Well understood, too, was the bitterness he harbored for the fact that his patrimony had fallen to Rand. The fortunes of war had dispossessed the legitimate son and rewarded the illegitimate, however, and nothing except another wrenching turn of fate could change matters back again.

“Would you object in my place?” William asked, the words layered with bitterness.

“Probably not,” Rand said, “but neither do I honor you for it. More, I have a warning for you. You’d best have a care if you think to profit from this business. For one thing, Henry is more likely to keep Braesford and its rents for himself than return them to you. For another, I will answer to the king for what occurred with Mademoiselle d’Amboise but don’t mean to hang. When this is done, I will discover who put about the foul story of child murder. They will then answer to me.”

“I would expect no less,” McConnell said with a shrug of one mailed shoulder.

“So long as we understand each other.”

McConnell swept up his fist, thumping it against his heart. Then he moved off. Rand watched him for long moments before he finally turned back to observe his bride as she mounted her palfrey at the block. He could have aided her, but did not trust himself to touch her in public, not in his present mood.

This was not, after all, the kind of mounting he had envisioned for this hour. Someone had seen to it he was disappointed in his desires. He looked away, his mouth set in a hard line as he considered, yet again, who that might be. Yes, and why.

They rode hard through the night, clattering along the dark lanes with only a fitful moon to show the way, choking on their own dust. No one called out or questioned their passage. They swept through villages and outlying farms where dogs barked and shutters were flung wide as householders leaned out to see who was abroad. Noting the king’s banner at the cavalcade’s head, the suddenly incurious banged their shutters closed again.

Dawn came, and still they kept the hard pace. Rand turned in his saddle to look back, seeking out Lady Isabel’s form near where her serving woman bumped along on her mule. His bride rode with her face set and her cloak rippling along the side of her mount, but her seat in her sidesaddle was not nearly as erect as when they set out. Facing forward again, Rand spurred to join the captain of his guard. He spoke a quiet suggestion.

At the next town, where they stopped to change horses, a narrow-bodied litter slung between mules was procured. Rand thought at first that his lady would decline being carried rather than riding, refuse the luxury of its feather-stuffed cushioning, also its hemp curtains, which shut out the sun’s bright rays. Good sense won out over pride, however, and she finally disappeared inside.

Traveling with the litter slowed them down, but was still better than being held up should the lady fall ill from exhaustion. She had just made this wearisome journey, after all, only to turn around and retrace the route.

It was late afternoon when Rand dropped back to walk his horse alongside the litter. Keeping his voice to a conversational tone, he said, “Lady Isabel, would you care for marzipan?”

She was doubtless either famished or bored to distraction, for she pushed back the side curtains at once. Supporting herself on one elbow, she asked, “Have you any?”

She appeared almost sybaritic among the litter’s cushions, with the lacings of her bodice loosened for ease and her golden hair escaping the confines of her veil. The sudden tightness in his groin was so intense it was an instant before he bethought himself and leaned to pass over the small drawstring bag filled with the confection that he had taken from his saddlebag. Watching with a rueful smile as she instantly drew it open and took out a piece that was dyed pink and green, it was a moment before he could speak again.

“Are you content in there?”

“Exceedingly. If the idea of the litter was yours, I thank you for it.”

“To see to your comfort is little enough. I am to blame for this sudden change of plans, after all.”

She swallowed the piece of marzipan, avoiding his gaze as she looked into the bag for another. “It seems a curious business. You are accused of a terrible act, yet allowed to ride as free as you please. I thought to see you in chains.”

“You might have, except I gave my pledge not to attempt to escape but to abide by the king’s will. William was good enough to accept it.”

“How convenient.”

“You don’t ask if I’m guilty.”

“Would you tell me if you were? If you are only going to protest your innocence, then where is the point?”

It was difficult to fault her logic, though it would have been pleasant if she had appeared to care one way or the other. That was apparently too much to expect. And if he did not look directly at her for any length of time, he discovered, he could attend to what she was saying instead of how she affected him.

“What if I’m not?” he asked after a moment.

“Then it will be shown, and all will be as before, yes?”

His every hope depended on it, and every future plan. “As you say.”

She looked up at that, as if something in his voice had snared her attention. “You doubt the king’s justice?”