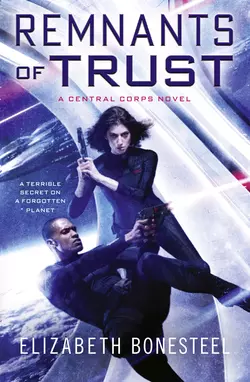

Remnants of Trust

Elizabeth Bonesteel

In this follow-up to the acclaimed military science fiction thriller The Cold Between, a young soldier finds herself caught in the crosshairs of a deadly conspiracy in deep space.In this follow-up to the acclaimed military science fiction thriller The Cold Between, a young soldier finds herself caught in the crosshairs of a deadly conspiracy in deep space.Six weeks ago, Commander Elena Shaw and Captain Greg Foster were court-martialed for their role in an event Central Gov denies ever happened. Yet instead of a dishonorable discharge or time in a military prison, Shaw and Foster and are now back together on Galileo. As punishment, they’ve been assigned to patrol the nearly empty space of the Third Sector.But their mundane mission quickly turns treacherous when the Galileo picks up a distress call: Exeter, a sister ship, is under attack from raiders. A PSI generation ship—the same one that recently broke off negotiations with Foster—is also in the sector and joins in the desperate battle that leaves ninety-seven of Exeter’s crew dead.An investigation of the disaster points to sabotage. And Exeter is only the beginning. When the PSI ship and Galileo suffer their own "accidents," it becomes clear that someone is willing to set off a war in the Third Sector to keep their secrets, and the clues point to the highest echelons of power . . . and deep into Shaw’s past.

REMNANTS OF TRUST

A CENTRAL CORPS NOVEL

Elizabeth Bonesteel

Copyright (#ulink_e9d1af36-27a7-5bbf-a97c-44f07a2cc22f)

HarperVoyager an imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

First published in Great Britain by Voyager 2016

Copyright © Elizabeth Bonesteel 2016

Cover design © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2016

Author photo © Virginia Bonesteel

Elizabeth Bonesteel asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008137830

Ebook Edition © November 2016 ISBN: 9780008137847

Version: 2016-10-21

Dedication (#ulink_e8fd3db9-0308-5ca6-a0ab-cae62b5ea9b3)

For Alex

Contents

Cover (#udaac904a-f1f1-5e1f-842f-d8c015333246)

Title Page (#ud8c519b2-ae10-57cf-a35f-182c611564ba)

Copyright (#u68c1c6f3-115f-5e7c-b573-5d992d4e34e4)

Dedication (#u4be6fd93-bee5-5afb-aed9-53ab5e32daf6)

Prologue (#uc021f7f4-ac1a-5df7-8531-8591e3f3075e)

Part I (#u0eb33ed6-a941-5252-98f4-798483fa2689)

Chapter 1 (#u8c663dc4-7461-5277-9d0d-cff1b654a2e0)

Chapter 2 (#ue103aebb-2684-5d8c-9387-3de8b0587864)

Chapter 3 (#u33175bf6-bf41-543c-bedf-8983c85b2e62)

Chapter 4 (#udbbef75b-4233-56ae-97df-b002ef3291c3)

Chapter 5 (#uc1e373ed-276c-58a5-92d6-2d9407749db2)

Chapter 6 (#ucdeb482b-4c7c-5adb-ae2b-fee5da726f2c)

Chapter 7 (#u6b31fbed-1a2f-55cf-9e24-d479d28548b7)

Chapter 8 (#uc068f6db-7ca6-5628-96f7-f2a5f1812c21)

Chapter 9 (#ucfe2cbd8-149d-5a2f-bbdf-bc4cd81a36ef)

Chapter 10 (#u53db97ad-4be2-5b5d-a607-d1194245c2c9)

Chapter 11 (#u0abb73b6-c102-52c7-a2f2-c1e9e28e3d7d)

Chapter 12 (#ud2236470-aaf8-571b-88e4-31d43be21070)

Chapter 13 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 14 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 15 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 16 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 17 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 18 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 19 (#litres_trial_promo)

Part II (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 20 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 21 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 22 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 23 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 24 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 25 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 26 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 27 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 28 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 29 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 30 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 31 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 32 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 33 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 34 (#litres_trial_promo)

Part III (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 35 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 36 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 37 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 38 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 39 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 40 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 41 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 42 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 43 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 44 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 45 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 46 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 47 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 48 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 49 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 50 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 51 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 52 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 53 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 54 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 55 (#litres_trial_promo)

Epilogue (#litres_trial_promo)

Acknowledgments (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

Also by Elizabeth Bonesteel (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

PROLOGUE (#ulink_5c7225b3-dc48-56d2-b7b3-58dca81b80bf)

T minus 8 years—Canberra

At least, thought Elena, I’ll die in a Corps uniform.

She faced down the gun, looking not into the barrel but into the eyes of the man holding it. Keita had brown eyes, but in the frigid, rainy afternoon of this dying planet they looked jet-black and devoid of light. He had always—for as long as she had known him—looked angry, but she thought she saw something else as he stared at her through the gun’s sight. Not fear, not that. Keita had never been afraid.

He looked lost.

The others were clustered behind him in the meager shelter of a crumbled cement wall. Savin was stoic as always, weight on one foot, but she saw his left hand resting on the grip of his pulse rifle. Jimmy had placed himself between Keita and Niree’s prone figure, the medic shielding his patient. Elena knew his expression without looking. The loud argument, in a shattered alley next to a public square, was risking their exposure. Jimmy would be annoyed with her.

“Get the fuck out of the way, Shaw!” Keita yelled.

She did not move. “Stand down, Ensign,” she said evenly.

“She killed the lieutenant! She set him up! You were there! You saw just like I did!”

Behind her, the girl she was protecting made a small sound, and Elena wanted to tell her to shut up. “She was a prisoner, Keita,” she said. The child had been in chains, used as bait. Keita had seen it, even if they had been too late to keep the lieutenant from being gunned down. “Lieutenant Treharne was trying to save her, and now you want to kill her?”

The gun’s barrel never wavered. “I will blow a hole through you, too, Shaw.”

At that, Jimmy couldn’t keep silent. “Keita—”

“Shut up, Jimmy.”

She and Keita said it in unison, and she almost laughed. But it was time to bring the confrontation to an end. “You’ll have to blow a hole through me, then, because I’m not fucking moving,” she said. “Make up your goddamned mind. We don’t have time for this shit.”

Seconds passed. Elena could hear the girl whimpering behind her, and fought off irritation. What good were tears? Tears wouldn’t make him put the gun down. Elena needed him to stop reacting and start thinking. She knew he could do it. She had seen him do it. She had served with him for six months aboard the CCSS Exeter, and despite his pretension of brainless thuggery, he was far more thoughtful than his usual manner betrayed.

“What about you, Savin?” Keita addressed the other infantry officer. “You with me, or are you going to listen to some fucking songbird?”

The nickname sounded ridiculous in context. But Savin, in his typically taciturn fashion, responded immediately:

“Songbird.”

Keita’s gaze faltered, and for a moment she caught a glimpse of pain in his eyes. Then he lowered his rifle, swore loudly, and stalked off.

The girl behind Elena began to sob openly. Elena ignored her, catching Savin’s eye. “Give him thirty seconds,” she instructed, “then get him back here.” Savin nodded and trotted after his friend. She turned to Jimmy, who had witnessed the entire exchange with growing incredulity. “Can you move her?” she asked.

Jimmy looked down at the fifth surviving member of their landing party. Lieutenant Niree Osai, ranking officer since Treharne’s death, was not unconscious, but she was in shock, blinking absently into the rain, her breathing shallow. Jimmy had used his jacket to wrap the remains of her arm, protecting the torn and ruined flesh from the acidic rainfall, but her color was awful, and she seemed to have no sense of where she was. Part of Elena envied her.

“She’s not stable,” he said. “She’s in shock, her pressure’s in the toilet, and she’s not nearly unconscious enough.”

“You misunderstand me.” She locked eyes with him. “I didn’t say should you move her, I said can you. Do you need help carrying her?”

“Lanie, she’s had her arm torn off. Moving her like this could kill her.”

She did not outrank him. She did not outrank any of them. She had no leg to stand on if she tried to give him an order. She wondered if Keita’s tactic with the rifle would work better for her. “Jimmy, if we’re not off this rock in seventeen and a half minutes, we lose our weather window, and we’re stuck here for thirty-seven hours. You fancy our chances for another thirty-seven hours?”

He knew as well as she did that they couldn’t survive it. Trained infantry or not, they were foreigners on this colony, and the natives who were hunting them knew every side street and abandoned building in the city. Starvation may have driven Canberra’s settlers mad, but it had not rendered them stupid. Keita and Savin had been able to retrieve Niree from them, but over two nights and a day, none of Elena’s team stood a chance.

Jimmy gave her a pleading look, but she did not shift. At last he sighed. “Yeah,” he told her, resigned. “I can carry her.”

“Get her ready, then. We’ll move when Keita gets back.” Jimmy knelt down by Niree, and Elena turned, at last, to the girl whose life she had saved.

She was fourteen, perhaps older. It was difficult to tell, sometimes, on planets where the children were chronically malnourished. She was short and thin and alabaster-pale, jet-black hair plastered to her cheeks by the soaking rain, and she had the sort of apple-cheeked prettiness that rarely bloomed into beauty with adulthood. She had stopped sobbing, but was still hiccupping, and her lips were blue. She stared at Elena with wide, frightened eyes.

“What’s your name?” Elena asked her.

A spark of hope rose in those eyes, and Elena could follow her thinking: perhaps I’ll be rescued after all. “Ruby.”

“Ruby.” Elena nodded. “If you slow us down, or give even the slightest indication that you are conspiring against us, I will shoot you myself. Understood?”

Those innocent eyes widened, and Elena saw tears filling them again. But Ruby nodded, and Elena turned away from her. “Can you fire and carry her at the same time?” she asked Jimmy.

“How many arms do you think I have?”

Just then Savin returned, and marching next to him was Keita, rifle still in his hands, the nose pointed at the ground. He would not meet her eyes, but Savin looked at her and gave her a nod.

“Okay.” She faced the others. “Two groups. Savin, you stay with Jimmy and Niree.” Savin was a dead shot; she wanted him protecting their wounded. “Keita, you’re with me and Ruby. We’re heading back to the ship. We leapfrog each other, providing covering fire.” She looked at them, one after another. “We’re more than a kilometer off, and we’ve got less than sixteen minutes to get there, so nobody stops. For anything. Clear?”

Three nods, including the child. Elena stared at Keita.

“Clear?” she repeated.

His eyes came up, dark and deadly, boring angrily into hers. “Clear.”

Jimmy and Savin went first, Jimmy slinging Niree awkwardly over one shoulder. He was a tall man, but slight—medics did not have to maintain the same fitness levels as the infantry, and with this planet’s Earth-point-two gravity, it was slowing him down. Of course, mechanics didn’t have to maintain infantry fitness levels, either, but she did it anyway, in part to prove to herself that she could, and in part to ensure nobody could accuse her of taking the easy way out.

If she had taken the easy way out, she might not have been a pilot as well as a mechanic. She might have missed this mission altogether. She might have been safe in Exeter’s engine room while her friends were running for their lives.

Better, or worse?

Shaking off the thought, she silently forgave Jimmy his high-gravity stumbles and beckoned to Keita, drawing her own weapon.

They proceeded through the ruined city a few hundred meters at a time, and Elena’s universe contracted into a short routine: watch, aim, wait … then run like hell to the next bit of shelter. The gravity fatigued her with alarming quickness, and she could feel a faint sting developing on her skin from the long exposure to the polluted rain. She felt increasingly conscious of the time as the visibility contracted with the waning afternoon, but she kept moving—silent, methodical—Keita’s footsteps solid and constant next to hers. It crossed her mind that she should not feel so comforted by the presence of a man who had just threatened to kill her, but there was no one else she would have chosen to be at her side in a fight.

It was almost a relief when the colonists started shooting.

She heard the pulse impact and Ruby’s shriek at the same moment. They were still a meter away from the shattered storefront they had chosen as their latest shelter, and the shot blasted a fireball into the ground just before them. As one Elena and Keita dodged around it, their strides lengthening, and they dove into the dirt behind the wrecked building. There was another shot, and for a moment Elena thought they had lost the girl. But an instant later she scrambled in between them, arms over her head, abruptly willing to risk sharing the shelter of the soldier who had wanted her dead.

“Where?” Elena asked.

Keita nodded behind them. “That garage we passed, just after Savin’s spot.”

“Long range?”

He checked his ammunition. “I’ve got three.”

“I’ve got five.”

“You’re a crappy shot with a rifle.”

Fair point.

He took aim and squeezed the trigger. An instant later the roof of the garage blew apart, leaving a corner of the structure on fire. A volley of shots came their way, peppering the ground before their ruined shelter. The colonists were not terrific shots themselves, she reflected, but it was enough—Jimmy would never get Niree through that.

She aimed her own rifle and fired back conventional pulse shots as Keita took aim again. She heard him inhale, then exhale. An instant later the rest of the structure burst into flames. Five seconds, ten: no more fire. Are they waiting? She caught sight of Jimmy and Savin through the smoke and flames, running across the remains of the city block. Savin had placed himself between Jimmy and the garage, and was firing one-handed as they ran past.

She thought they might make it.

Elena kept up her shooting as they ran, although she never saw anyone hidden in the dense rubble of what was left of the city, never knew what she was aiming at. Ruby had grown silent, and the one time Elena looked at her she saw the girl’s eyes had gone dull and cold.

Probably for the best.

At long last, with less than four minutes left, they caught sight of the ship, waiting in what had once been the town square. Four of the colonists swarmed around it, running their hands over it, and Elena swore.

Next to her Keita let out a chuckle. “Anything goes until they touch your baby, right, Songbird?”

Elena aimed at one of the colonists, then dropped the nose of her rifle and shot toward the ground. A chunk of cement erupted a meter in front of him. He started, and as he turned, she risked speaking.

“Get away from that ship or we will kill you!” It wasn’t much of a threat, but there was little else she could do.

The man—boy, woman; she could not tell from this distance what the emaciated figure had been—shot toward her voice. The round exploded the corner of the building they were crouched behind. She swore again, then did what she had heard Keita do: she inhaled, exhaled, and fired.

The figure’s chest burst with a brief flame, and he dropped.

Somewhat startled by having hit her target, Elena aimed at another, but the rest turned and ran, leaving their fallen comrade behind. She kept her rifle pointed at the motionless form, aware of Keita next to her doing the same. After a moment, Jimmy and Savin came around them, running for the ship, and it was clear Elena’s target wasn’t getting up.

She engaged her comm. “Open the door,” she told the shuttle.

The door slid open. She saw Jimmy haul himself inside and begin to lower Niree to the floor. Savin took an instant to stop by the man Elena had shot—the man she had killed—and scoop up his weapon. Then he, too, jumped onto the ship, crouching in the open doorway to provide cover.

She straightened, ready to run; and only then did she notice Keita looking off to one side. He was frowning, his whole body alert. Next to him, Ruby was staring at their ship, her expression dazed and faintly hopeful.

“Keita.”

“Ssh,” he said brusquely. “Can’t you hear it?”

She listened. She heard rain, Ruby’s breathing, her own heartbeat. “Keita, we have to go now.”

He turned to her. His anger was gone, replaced by something urgent and determined. “I need two minutes.”

“We do not have two minutes!”

“Then give me what we do have.”

He stared at her steadily, unwavering. She wondered, if she tried to order him, if he would listen to her. She wondered what she would do if she had to leave without him.

It was not her choice.

“We take off in ninety-six seconds,” she told him.

In a flash he was gone, dashing off into the darkening city. Without looking she clapped her hand around Ruby’s scrawny arm and pulled her forward, running full-tilt for the ship.

She released the girl as soon as they leapt on, heading for the cockpit. “Time.”

“Eighty-four seconds,” the ship told her calmly.

“Lift off at eighty-three and a half.” She met Ruby’s eyes and pointed to the bench along the far wall, where Lieutenant Treharne had been sitting when they arrived … forty-six minutes ago.

Christ.

“Sit down, buckle up, and be still,” she commanded. Ruby did as she was told, and Elena thought her quick obedience had probably helped her survive this far. She stepped over to Jimmy, who had strapped Niree down onto another bench and was applying the ship’s med scanner. “Will she make it?” she asked.

He looked at her, his expression unreadable. “We didn’t do her any favors, hauling her out like that.” At her look, he acquiesced. “Yes, I think so.”

“Strap in for takeoff, then.”

She heard the engines igniting and checked the time. Twenty-eight seconds—he wasn’t going to make it. They would come back for him, of course, for what it was worth, but not even Dmitri Keita was going to survive a day and a half in this place.

Climbing into the pilot’s seat, she did a perfunctory preflight check. She keyed in the course home, compensating for the rapidly contracting weather pattern.

“Flight in this weather is not recommended,” the ship told her. “Heavy turbulence is likely.”

I know, I know … “Hang on,” she called to the others. “This won’t be comfortable.”

At seven seconds, she heard feet outside the door and saw Savin tense. But then Keita was on board, drenched and covered in mud, something dark and wet clutched against his chest. “Go!” he shouted at her.

She was ready for him. She jerked the controls, and the ship jolted off the ground with three seconds to spare.

Normally Elena was a careful pilot. The infantry liked to fly with her. When there was turbulence, she would engage the artificial gravity just enough to temper the disruption of the atmosphere.

Today was definitely not normal.

She shot them straight up, as fast as they would go, allowing the planet’s gravity to press down on them. She stared into the atmosphere, peering at the darkening clouds, looking for the fastest path out of the weather.

Through her concentration she heard a sound behind her, and she wondered if Keita’s bundle was a cat.

Her viewscreen began to glow red, and her attention was dragged back to the task of flying. Great, she thought, the planet’s particulate atmosphere is ripping into our hull. Elena whispered a quiet apology to the ship, thinking herself ahead twenty minutes, picturing herself home on Exeter, standing in the shuttle bay while her chief berated her for the state of her vessel. She would be days repairing it.

“Inversion in five,” she told them, and counted down the seconds.

Moments later the artificial gravity engaged, abruptly reorienting them. She heard retching behind her; that was likely the girl. Elena usually took pride in gentle inversions, but today it had seemed slightly less important.

The night opened up before her, dark and pure and scattered with stars, and the glow of heat faded as the vacuum of space cooled their exterior. She sat back and closed her eyes. They were alive.

Most of them.

That sound again. She frowned. It wasn’t Ruby—she could hear the girl alternating between retching and sobbing, Jimmy offering her quiet words of comfort. She turned around. Savin, still relaxed, was watching over Niree as Jimmy rubbed Ruby’s back and held a bucket before her.

Keita sat in the corner, looking down at a bundle of muddy, sodden rags in his arms. She heard the sound again, and then a quiet response from him.

Is he singing?

She got to her feet and walked the length of the ship to stand over him. In his arms, wrapped in what looked like old shirts, was a baby. Elena knew little of such things, but she guessed it was no more than a few hours old. It was wide-awake, but it was not crying. Instead, it was studying Keita with enormous, somber purple eyes, that odd color some babies were born with. Every few moments it opened its mouth to make that small sound, a mew of greeting or protest; and Keita responded each time, rocking the infant gently.

“Jimmy should look at it,” she said.

“Her.” Keita’s eyes never left the infant’s. “And she’s fine.”

She stood for a moment, watching the incongruous scene, then retreated, making her way back to the pilot’s seat. She would have to comm Exeter, let them know Treharne was dead and that they had rescued only two of the colonists. In a day and a half a larger crew would go down, more heavily armed, properly prepared after the report she would give them.

She wondered how many colonists would be left.

She closed her eyes, remembered aiming her rifle, her futile warning. On that planet, killing would have been a mercy. He had been emaciated, close to death, or at least close to the point where his companions would pull him apart to keep themselves alive a little longer. He had been trying to kill them, too; but really, she had done him a favor.

She saw the flame bloom in his chest, saw him drop.

Elena opened her eyes, sat up straight, and opened a channel to make her report.

PART I (#ulink_fcf6cc44-8774-5dc4-8224-153ee74cd750)

CHAPTER 1 (#ulink_b22bf026-8088-5f76-9fa7-e47c520ec17a)

Orunmila

Guanyin was always amazed by how well puppies could sleep.

Samedi had slid into the narrow space between her pregnant belly and the wall, his body twisted like soft pastry, and was snoring blissfully into her ear as she stared at the ceiling. When he had first dozed off she had tried blowing on his nose. The first two times he had twitched, but the third time he was oblivious. She could almost certainly get out of bed without disturbing him, but she needed him as an excuse. If she sat up she would feel obligated to stand, and if she stood, she would feel obligated to talk to Cali about the warship Central Corps had just dropped in their backyard.

Cali would expect her to have worked it out, to have a plan of action. She had always looked to Guanyin for direction, even when they were children. Cali was three years older, but she had always been more comfortable as Guanyin’s foot soldier than as her mentor. Guanyin knew many in her crew expected her to choose Cali as her second-in-command, and certainly she could trust Cali with her life. But for a first officer, Guanyin needed an adviser, someone who could help challenge her thinking. That was not Cali.

That was Chanyu, the ship’s former captain, but he had retired. They had left him on Prokofiev’s third moon, waiting for a shuttle to the Fifth Sector. She could probably find him if she needed to, but she knew what he would say. “You must find your own way, Guanyin. Orunmila is yours now. She lives or dies under your command. And remember, dear girl, she wouldn’t be yours if they didn’t believe in you. All you need to do is be worthy of them.” Chanyu had raised her, and she loved him like a father, but she never could stand it when he spouted that sort of useless rubbish.

Guanyin was twenty-nine years old, pregnant with her sixth child, and captain of a starship that was home to 812 people. She had no second-in-command and no advisers, and it was down to her to figure out how to respond to a deployment buildup from the largest, best-armed government in the galaxy.

“It’s only one ship,” Yunru had remarked over dinner with their children. “It may not mean what you think it means.” Which had occurred to her, of course. The CCSS Galileo was small for a Central starship, half the size of Exeter, the ship Orunmila most often dealt with. But unlike the equally small science ship CCSS Cassia, Galileo was unambiguously a warship. Central was not entirely inept at diplomacy, but they always felt the need to back it up with weapons. Galileo was spectacularly well equipped to do just that.

Not that she couldn’t understand why Central would feel the need to build up their weaponry in the Third Sector. Numerous multiyear crop failures had led to an increase in intersystem squabbles and civil wars, and the Syndicate tribes, finding larger markets for contraband, were becoming bolder and more aggressive. But when Galileo had appeared a few weeks ago, contacting supply chains and shipping companies as if she had been in the Third Sector for years, Guanyin had found their polite diplomatic greeting entirely inadequate.

It had taken Guanyin very little research to remind herself where she had heard the ship’s name before. Galileo had been credited last year with preventing an all-out war in the Fifth Sector. No less than Valeria Solomonoff herself, the Fifth Sector’s most venerable PSI captain, had signed a treaty with Central through Galileo. Galileo’s captain, a man called Greg Foster, was widely considered to be an accomplished diplomat.

Guanyin disliked diplomats. She always found they were too good at lying for her taste. So when Greg Foster had contacted her, ostensibly to introduce his ship, she had been cold, unfriendly, and more than a little blunt.

“You waste your time with me, Captain Foster,” she had told him. “It is the Syndicates attacking your ships, not us.”

The last six months had seen a marked increase in Syndicate raider activity, and for the first time in decades they had included Central Corps starships in their targets. PSI, who had dealt with raiders for centuries, was the obvious place for Central to turn when formulating their own strategies for dealing with guerrilla attacks. A request for help Guanyin might have understood, the sort of short-term alliance PSI and the Corps had formed repeatedly over the centuries. She did not understand this amorphous buildup of Central’s power, and it bothered her.

What is Central planning?

The baby rolled and kicked, and Samedi woke up, his wolfish face next to hers. She reached up a hand and rubbed him reassuringly between the ears. “Do you suppose they are trying to trick us, little one?” she asked. “Or do they fear something specific, and don’t want to tell us what it is?”

Samedi gazed at her with his contented, worshipful eyes, and sneezed in her face.

Cali heard her roll out of bed, and came in from the sitting room to lean against the bathroom doorframe as Guanyin washed her face. “He’s too young to be in bed with you,” Cali said.

“When he’s old enough he’ll be too big.”

“You slept with Shuja when he weighed more than you did.”

“Shuja never weighed that much.” Actually, Cali was right: Shuja had topped out at sixty kilos before he had started dropping weight due to illness and old age. Guanyin only broke fifty-five when she was pregnant. But she had been pregnant for half of Shuja’s adult life, and she had grown used to having a dog curled up next to her expanding stomach. “Samedi will learn.”

Cali crossed her arms and glowered.

“Your face will freeze that way, you know.”

Not that it would matter if it did, of course. Cali was beautiful, and she knew it, breaking hearts without thinking much about it. Guanyin, who never doubted her own place in Cali’s heart, yelled at her sometimes, but it made no difference, and she supposed Cali would have to grow out of it on her own. But Guanyin knew one of the reasons she had reacted to Captain Foster the way she had was because he reminded her of Cali, right down to the polite condescension.

Guanyin turned away from the sink. “Can I ask you something?”

Cali pushed herself off the doorframe as Guanyin walked past and asked Orunmila for some music. Guanyin settled back onto the bed next to the patient puppy, wide-awake now and wagging his entire body, trying and failing to resist licking her face. “No, love,” she said sternly, and he backed off onto his haunches, waiting for her to change her mind.

Cali pulled up a chair and sat next to the bed. “Is this about the Corps captain?”

“He talked to me like you do, sometimes. Like I’m helpless, or too young to understand. He seemed to think I would find him persuasive and comforting, just because he has a nice smile, never mind the volume of weapons his ship is carrying into our territory.”

At that, Cali grinned. “Did you swear at him?”

It was Guanyin’s turn to glower. “Why do you do it? When you know I understand all this better than you do. Why do you treat me like a child?”

Cali shrugged and looked away. “Because I love you, I suppose, and I don’t like that things are hard for you. I want to do it for you, even when I can’t.”

That was a surprisingly introspective observation for Cali. “Captain Foster doesn’t love me.”

“Maybe you remind him of someone else.”

“Maybe he thinks, because I’m new, I’m a fool.” She shook her head. “I don’t understand. He dealt with Valeria Solomonoff in the Fifth Sector. You really think she let him get away with shit like this?”

“Maybe she doesn’t like him, either.”

“I spoke to her. She trusts him. She said, and I quote, ‘He is fighting what we are fighting.’ You know what she didn’t say?”

“I wasn’t there, Guanyin.”

“She didn’t say ‘He is a good soldier.’ So why is he talking to me as if there is nothing going on?”

Cali leaned forward, elbows on her knees. “You know, Guanyin, you could ask him. I mean, instead of trying to analyze what Solomonoff really meant, or poking at my character flaws.”

She sighed, gently tugging Samedi’s soft ears. “I was rude to him.”

“They’re rude to us all the time, and they’ve still told one of their captains to kiss your ass.” Cali shrugged. “They want something. Find out what it is. Maybe we can get something in return.”

Admittedly, that was not terrible advice. “What could they possibly want from us?”

At her words, Samedi launched himself at her again, and she had to close her eyes against his silky-soft tongue. “Hopefully puppies,” Cali said dryly, and Guanyin laughed.

The comm on her wall chimed, and Aida spoke without waiting for acknowledgment. “I’m sorry to interrupt, Captain Shiang,” he said, “but we’re receiving a distress call.”

She could hear it in his voice: tension and fear. She sat up, her hand resting on Samedi’s head. “Acknowledge and reroute,” she told him, knowing he would have started the process already. “Who is it?”

“It’s a Central starship, ma’am,” he said. “Captain—it’s Exeter.”

She met Cali’s eyes. They had not seen Exeter in more than six months—since before Chanyu’s retirement—but they had run countless missions with her for a decade. She had thought to wonder, just that morning, why Central had not had Exeter arrange for her to meet Galileo’s captain, instead of expecting her to accept the goodwill of a stranger. She wondered if Captain Çelik was still at Exeter’s helm.

She wondered if he was all right.

“What are they up against?” She swung her feet to the floor and stood, all her fatigue washed away by adrenaline.

“Syndicate ships, Captain. They’re reporting twenty-seven.”

Twenty-seven raiders. Against a Central starship. “How close are we?”

“Two minutes, eight seconds, ma’am.”

“Get all weapons online,” she told him. “Orunmila, call battle stations ship-wide.”

The lights shifted to blue, and the quiet, repeating alarm came over the ship’s public comm system. Cali fell into step behind her as she rushed out of her quarters into the hallway.

Raiders were often reckless—and occasionally suicidal—but attacking Central was a recent tactic. There had been three attacks over the last six months, always the usual smash-and-grab, and only one had been at all successful. So many raiders against a single starship … the Syndicates were never so bold. An attack so aggressive was insanity. Even if they scored against Exeter, who was well armed in her own right, Central could not let the attack stand. This battle, whatever the cause, was only the start, and the Syndicates had to know that.

She thought again of Galileo’s abrupt appearance, and wondered how much Central had known in advance.

CHAPTER 2 (#ulink_ad1b2807-c060-52f4-bcc6-24bc01f6ca2e)

Galileo

Took on parts at Lakota, Greg Foster wrote. Four days’ travel en route to Shixin. Fucked up the latest negotiations with PSI.

No. It was not the sort of report he would be allowed to file.

He swept a finger through the offending paragraph to delete it and stared, frustrated, at the nearly empty document. Realistically, writing the report should have taken no more than half an hour—less if he wrote in generalities—but he was fairly certain insufficient detail would cause Admiral Herrod to bounce the report right back with orders to do it over. Even with a proper level of information, though, he would need to take some care with his word choice. Allowing his frustration to bleed through onto the page would not help his shaky standing with the Admiralty.

Looking back on his conversation with the PSI captain, he couldn’t blame her for being suspicious. Galileo was hardly a stealth ship—even before the blowup last year, Greg’s ship and her crew had kept a fairly high profile in the squabble-ridden Fourth Sector. And their first foray into the Fifth Sector had involved a set of incidents that had almost provoked all-out war between Central and the PSI ships in that region. He had known Galileo’s precipitous deployment to the Third Sector, done without so much as a polite forewarning for the non-Corps ships in the area, was likely to be misinterpreted. What he hadn’t quite understood was how little his experiences in the Fifth Sector would matter here.

Shiang Guanyin, captain of the PSI ship Orunmila, had viewed Galileo’s arrival with hair-trigger paranoia, and he could not blame her. But even so, he had been surprised to find himself so far unable to open any kind of dialogue with her at all.

“Thank you for the introduction,” she had said, her Standard enunciated carefully. “Should we find ourselves requiring anything at all from you or your government, we will let you know.” And she had terminated the comm.

He did not have to review his diplomatic training to recognize she felt insulted, and by more than Galileo’s presence. Clearly something in how he had presented himself had put her off.

He had considered more than once just telling her the truth: that Galileo’s presence had nothing to do with PSI, or even the resource issues in the Third Sector. Central was indeed spread too thin, the supply chains delivering raw materials for construction having been constrained for years; but Galileo had been reassigned for an entirely different reason. He could tell Captain Shiang, he supposed, that he was only there so his superiors could make sure he remembered who called the shots. But he did not think that would inspire confidence in either him or Central Gov.

Although it would certainly torpedo what’s left of my career.

Weary of his mind running in circles, he rubbed his eyes with a thumb and forefinger and let his attention drift to the window. There were no stars for him to contemplate, just the silver-blue brightness of the FTL field moderated by Galileo’s polarizers. They would be in the field another three hours before they stopped to recharge, and another five days before finally reaching their supply pickup. If he finished this damn report, he could enjoy some peace and quiet for a change. The last six months had been, in some ways, the most eventful of his fourteen-year career.

There was the court-martial and its outcome, of course, about which he was still not sure what to think. What had happened the year before had been too public for the Admiralty to cover up, and they had struggled to come up with charges that reflected the seriousness of the events but didn’t alienate a public that seemed inclined to see both Greg and Elena as heroes. In the end they were charged with insubordination and destruction of government property, although the public record of the trial was coy about exactly what that property had been.

The final verdict—splitting hairs over specific charges, making them appear to be something between naively innocent and subversively guilty—had turned out to be strangely toothless. He and Elena had been taken off the promotion lists—her for a year, him for two—and they had each been assigned their own personal admiral with whom they were required to file monthly mission reports for the next half year. The most concrete changes were Galileo’s reassignment from her usual Fourth Sector patrol to the Third Sector, and the deployment of a dozen recent Academy graduates who probably shouldn’t have made it past their first year.

Which meant that, yes, they had been sent a message. Just not one that made sense to Greg. Anyone who thought subtle insults would alter either his or her conviction that they had done exactly the right thing was unfamiliar with both of them to the point of absurdity.

But it was more than his professional life that had changed. For the first time in thirteen years—since he had deployed at the arrogant, self-assured age of twenty-four—he was unmarried and unattached, and he had not considered the impact that would have on his day-to-day life. There had always been people who saw his marriage as a challenge rather than a deterrent, but its absence had brought him a whole new population of admirers that he had no idea how to properly deflect. His usual techniques were not as effective on this crowd, and he often found himself caught flat-footed while trying to let someone down kindly. Having a wife had provided a buffer between him and the natural impulses of a crew that spent months in close quarters. He had been working to include himself more in their day-to-day lives, and many of them seemed happy to welcome him in without limits.

Jessica Lockwood, his newly minted second-in-command, had tried to explain it to him. “They’re just happy for you, sir,” she had told him, as if that explained everything. Jessica always put him in mind of his sister: practical and irrepressible, indulgent with what she perceived to be his shortcomings. Jessica would never come right out and tell him he was an emotional idiot, but he was pretty sure she thought it frequently.

And then there were the people who expressed sympathy about his divorce—which he found equally puzzling. He did not doubt their intentions, but he did not understand how they could so thoroughly misread how he felt. Even Jessica tiptoed around the subject of Caroline, as if his ex-wife were a land mine or a raw nerve. In truth, he almost never thought of her, all the pain and resentment of their fourteen-year marriage having vanished for him even before the dissolution was finalized. Most days he felt light, more buoyant than he had felt since he was a child, and nobody seemed to notice.

Well, almost nobody.

Resigning himself to the impulse, he engaged his comm in text mode. “You up?” he asked.

A brief pause, and the word Yes appeared in the air half a meter before his eyes.

“You done yet?”

No.

He shouldn’t ask. He had no business asking. Things between them had not yet healed. “You want to come finish here?”

A longer pause this time. Then: Do you have tea?

“I will by the time you get here.”

She rang the door chime when she arrived. This was a regression—for years she had walked into his office unannounced, confident of her welcome. But showing up at all … that was progress. Glacial and frustrating, but progress.

He had Galileo open the door, and his chief of engineering walked in. Elena Shaw, his closest friend before he had blown it all up, still the person he trusted above anyone else. He had thought, for years, that what he felt for her was complicated, designed to trip him up when he least expected it. For a time, he had thought her presence was a curse. It was only recently, when faced with losing her, that he had recognized what he felt for her was simple. What was complicated was coping with it.

Oblivious to his ruminating, she dropped into the chair across from him and wrapped her fingers around the mug of hot tea. “So how far did you get?” she asked.

She was watching him with those eyes of hers, sharp and perceptive and bright with intelligence. Also dark and beautiful and so easy to get lost in. She was not pretty the way many of the women on his ship were pretty: her features were too uneven, the balance thrown off by her huge eyes and substantial nose. But there was an elegance about her, the way she moved, the way she spoke, as if she were some creature of earth and fire, liquid and molten. He often thought he could spend the rest of his days quite happily doing nothing but watching her.

In fact, he had said this to his father when he had visited last month. The older man had shaken his head, and said it was a damn good thing Greg had gotten divorced.

More proof he knows me better than I thought he did.

“Through last week,” he replied to Elena’s question.

She rolled her eyes, leaning back and lifting the mug close to her face. “I’m three weeks behind,” she confessed. “I have too much work to do for this shit.”

“It’s not about the report. It’s about reminding us who’s the boss.”

She knew that, of course. They had discussed the outcome at the time, and both understood the court-martial could have ended quite differently. The Admiralty would have been well within its rights to throw them out of the service entirely—saving the sector be damned. They hadn’t, and the one conclusion he and Elena had come up with was that the Admiralty simply couldn’t agree on what to do with them. “Some of them wanted to give you a medal,” Admiral Herrod had told Greg shortly after the trial’s conclusion. “Some of them wanted to separate the two of you.” At that the old man had frowned, and for a moment Greg had the impression that the typically circumspect admiral was speaking entirely off the record. “Whatever else you do, Foster—don’t let them separate you. And watch your back.”

It was a precaution Greg had already thought about, but hearing Herrod suggest it, when he couldn’t be sure where the man’s loyalties lay, left Greg feeling even more uncertain and unsafe.

When he had repeated Herrod’s words to Elena, she had only said, “Where does he think we would go?”

She was watching him now through the steam from her tea. “You should have Jessie do it for you,” she told him.

“She doesn’t write like me.”

“You think Herrod gives a damn?”

“Why don’t you ask her to do yours?”

She gave him a mock glare. “You promoted her over me, remember?”

“Okay, then get Galileo to do it.”

“Which is not a terrible idea,” she agreed, “apart from the fact that Galileo wouldn’t write like me at all.”

“So we can’t get around this,” he concluded, resigned.

She set the mug down on the desk. “Thirty minutes, no talking, we knock these out and we’re done with it.”

“And promise ourselves not to leave it to the last minute next month.”

She grinned. “That too.”

They both fell silent, and Greg returned to figuring out how to describe his discussions with PSI. He wrote and erased the section of his report four times, aware he was attracting Elena’s attention. At last he leaned back, frustrated. “I don’t know how to say this,” he said.

“What have you got?”

“I just deleted it.” At her look, he added, “I can’t just tell him ‘I said this, and she said that.’ I know Herrod. He’s not going to give me any leeway, not in an official document. The man doesn’t like me.”

“It’s not personal. The man is doing a job, just like you are.” When he said nothing, she extended a hand toward his document. “Let me try.”

“You don’t write like me, either.”

“So wordsmith it when I’m done.”

He let her tug the document to her side of the desk, watching her set her own aside. She read his last paragraph and frowned, then wrote rapidly for a moment. When she was finished, she pushed the document back over to him.

He read. “This is a lie.”

“It is not.”

“Negotiations are not ‘ongoing.’ I’m trying to figure out how I could possibly respond to her without sounding like an asshole.”

“The most important thing about diplomacy,” Elena said, “is not the goal. It’s establishing communication. You’ve done that.” He glared, and she shook her head. “How can you be such a good diplomat, and so lousy at managing your own chain of command?”

“I’m not a good diplomat. That’s the problem.” But he reread her words. They were not bad. He reached in and reordered a phrase—she had nailed his voice pretty well. If you use this, he reminded himself, you can be finished. “Herrod will peg this for bullshit.”

“Of course he will.” She had turned back to her own work. “He’s a bright person. But you’ll have made the effort to spin it, and that’s what he wants.” She made a few notes, then sat back. “There.”

“You wrote up three weeks already?”

She shrugged. “I’m a mechanic. My life is much less interesting than yours.”

“Plus Admiral Waris likes you.”

Elena’s supervisor, Ilona Waris, had been a mechanics teacher when Elena was at Central’s military academy on Earth, and Elena’s aptitude had rapidly secured her place as the teacher’s favorite. Waris had kept track of Elena’s career, occasionally offering unsolicited advice, but Greg had always had the sense that Elena found the woman overbearing. Elena had no ambition—she would not even have been chief if Galileo’s old chief hadn’t been killed—but she had enough political savvy to keep from completely rebuffing Waris’s sporadic attempts to keep in touch.

Elena had paused, and was looking at him, her expression troubled. “She voted to acquit us,” she said.

“Is that bad?”

“She said … how did she put it? ‘Your careers shouldn’t be hamstrung over one bad call in the field.’ ”

Bad call. He could tell from her expression she disagreed with the term as much as he did. “You think she’s on the other side?”

The other side meant Shadow Ops, an organization within Central’s official government that wielded far more power than most people knew. S-O had been knee-deep in the events that had ended with their trial. Not that they could prove any of it, of course. All of the physical evidence was gone, and S-O’s public face was one of benign, largely ineffective bureaucracy. But they both knew differently, and he knew she was aware of the implications of Admiral Waris’s statement. Acquittal would have meant Central could have sent them off anywhere, unsupervised. They could have been separated, isolated from each other, alone with their suspicions and without resources to pursue them. Or they could have vanished without a trace, just a couple of random, unrelated accidents, and no one would even have asked the question.

“I think,” Elena told him, “that presuming on an old acquaintance would be incalculably foolish. So I will be a boring mechanic in my reports, and she can check off a box, and she and I can smile at each other with our fingers crossed behind our backs.”

Trust was the biggest casualty of the events of the last year. Elena, despite her years of experience in the Corps, used to trust her superiors to be in the right, at least as far as their intentions were concerned. The loss was a small one, he suspected, but it was a loss all the same, on the heels of far too many others. “Elena,” he began, “you know I—”

A high tone sounded, and the wall readout flashed red. He stood, but across from him Elena was already moving, sweeping away both of their documents with a wave of her hand and pulling up a tactical view of Galileo. Out the window the field dimmed and dissipated into stars, and they hung still for a moment as the ship changed their flight plan. Then the stars blurred and they were in the field again, and if he had not heard the alarm he would have thought nothing had changed.

A priority Central distress call.

All ships in the vicinity, help us.

“Status,” he said tersely. Above his desk, his ship rendered a reconstructed tactical display of a starship similar in design to Galileo, only three times the size: a great sprawling eagle rather than a sparrow. The CCSS Exeter. He stole a glance at Elena, who was staring at the display, her jaw set. In addition to being the Corps ship that had patrolled the Third Sector the longest, Exeter had been Elena’s first deployment. She still knew people who served there.

Emily Broadmoor, Greg’s chief of security and infantry commander, entered the room as Galileo gave status. “CCSS Exeter reports being under attack by twenty-seven Syndicate raiders. Current readings count twenty.”

Twenty-seven. He could not recall ever hearing of a Syndicate tribe so large.

“Additional status is available,” Galileo added helpfully.

Jessica came in, trailed by Greg’s medical and comms officers. He caught her eye. “Give us what you’ve got,” he told his ship, as Jessica moved to stand beside him.

The display animated with twenty-seven small ships, replaying the status relayed by Exeter’s sensors. The small ships spiraled in eerie unison, blasting somewhat futilely at Exeter’s solid hull. Exeter was firing back with external weapons, but her response was sluggish, and the raiders looped and dashed and avoided more shots than they took. As they all watched, one raider split from the others, heading abruptly toward Exeter’s belly. Exeter shot at the small fighter, a single gun, over and over again. She missed each time.

The little ship pitched and yawed like a drunken soldier, and for a moment Greg hoped against hope that it would miss Exeter entirely. But as they watched, it sped up and lurched into Exeter’s side.

Greg’s office was lit by the playback of the massive blast, and when it faded there was a flaming crescent carved out of Exeter’s side, debris flying out of the gap. One-third of the starship had vanished. That the ship had survived to send a distress call was a minor miracle.

Greg’s fists clenched involuntarily as they watched the remainder of the reenactment. He knew it was already over, but he found himself waiting for the battle to go differently, for their gunner’s aim to improve, for some impossible sign that Exeter would recover. Instead, a single raider flew, unmolested, into Exeter’s wrecked side and attached itself like a limpet to the open wound. The remaining raiders kept circling the starship, drawing Exeter’s meager fire. Five of the tiny ships flamed out in the path of the starship’s crippled weapons. Someone with some skill had found their way to the targeting controls.

Or maybe, Greg reflected, thinking of the futile shots before the impact, they were just luckier than they had been before.

A moment later the reconstruction looped back to the beginning, and Greg dismissed it. “Audio?” he prompted.

A voice began to speak, garbled by digital artifacting. “Mayday, Mayday, Mayday,” a deep voice said. Greg recognized Captain Çelik. “We are under attack. Syndicate raiders. We’re down to one gun, no shuttles. All ships in the area, please respond. Emergency. All ships—”

The voice broke off.

Christ.

The Syndicates had never moved so boldly against Central. There were skirmishes, sure—over the past year, there had been a handful of swipes taken at Corps starships, but nothing remotely this aggressive. Their goal had always been theft and escape, not engagement.

What the hell could have prompted this?

But the why of it was secondary for now. “ETA?”

“Three minutes, fifty-eight seconds.”

Too long. “Has anyone else acknowledged the Mayday?”

“The PSI ship Orunmila will arrive in one minute and seven seconds.”

With Orunmila’s help, Exeter might stand a chance. Thank God, he thought, for spiky, suspicious PSI captains. He looked up. “I want two ships on deck for a boarding party. Two platoons, armored. That limpet likely means they were boarded. And Bob, I want a full medical team in with the infantry.” Surely there would be survivors. Surely there would be some hope to salvage out of all of this. “Mr. Mosqueda, I want all comms in and out monitored, and I want to know what they heard before they got hit. Chief,” he told Elena, “you’re on weapons, and watch out for jammers. I don’t know why Exeter couldn’t defend themselves, but if those bastards try that same trick with us, blow them apart. Commander Lockwood, you’re with me. I want this over fast, everyone. We’re not losing anyone else.”

He watched them disperse, all efficiency and purpose, and tried not to imagine the crew of Exeter, not three minutes earlier, doing exactly the same thing.

CHAPTER 3 (#ulink_83cb8751-4082-5fe2-ba06-a5c42f50160b)

Elena ran down the hall, thinking back to the last time she had been in a firefight. The battle had been on a much smaller scale, but the odds had been overwhelmingly against her, and the outcome had been far less certain. Strange how little she remembered of the actual shooting. Most of her memories were of her companion: levelheaded, experienced, strong, and good-humored, even in the face of what had seemed like certain death. He had stood with her, unwavering, despite the fact that she had brought him all of his trouble, that he had known her only a day. Here, diving into a fight to save what was left of Exeter, she thought of how invulnerable she had felt when she was with him, how she could fight anything. She let the memory flood her bloodstream, leaving her cool and determined. You’ve done this before. You can do this again.

She entered engineering, her eyes sweeping over her crew. They were already at their stations, subdued but composed, even the new kids who were dumped on Greg before they left Earth. She tried to remember how many battle drills she had done with them. She tried to remember if battle drills had helped her at all the first time she had been shot at. She didn’t think so. Real-world battle had little to do with drills, and everything to do with who you were underneath.

She would have spared them this early test if she could.

Ted Shimada, her second, was waiting to take her aside, pulling her away from the others before she could reach the main weapons console. “What do you think we’re facing here?” he asked, his voice low enough to keep the others from overhearing.

She studied his expression. Ted’s reputation as a clown was not entirely undeserved, but she had known him for more than ten years, and she knew his clowning masked a sharp and observant mind. He was one of a short list of people whose judgment she trusted absolutely, and the only one—with the possible exception of Greg—whom she would trust to look after her engines. He would have noticed the same anomalies in the replay of Exeter’s hit that she had.

“Your paycheck and mine says the bomber was a drone,” she replied, “although whoever was remoting the thing didn’t know what they were doing. Most of the others are drones, too, but based on the flight pattern I’m guessing those are autopilot.” That would give Galileo a tactical advantage; autopilots in drones that size were almost always less imaginative than human operators.

“Especially with most of those Syndicate bastards too cowardly to risk their own skins hitting a Corps starship.” His jaw worked, and he looked away from her for a moment. “Shit, Lanie.”

“Later, Ted.” She put her hand on his arm, just for a moment. “Let’s get them out of this first.”

Easy enough to say.

She turned to the weapons console, taking in the bank of green indicators. She could see, in her mind, over and over, the replay of Exeter’s destruction. There might be survivors—if the ship’s environmentals had survived to seal in the atmosphere—but there would be many, many dead. And she would know their names.

Not now.

She heard the engine’s harmonic change as the field generator began to spin down, and then Greg’s voice over ship-wide comms: “All hands, enemy engaged.”

They dropped into normal space.

She had expected to see Exeter, to be facing its destroyed underbelly, burned and twisted metal over the exposed bones of the ship’s structure. Instead, she saw a massive, unfamiliar flat bulkhead scattered with lines of windows, and a swarm of those Syndicate drones firing into the dark hull. She glanced over at the generated tactical view to find they had emerged on top of another ship, larger and bulkier than Galileo, its graceful, hybrid lines identifying it as the PSI ship Orunmila. She beamed a silent thank you to its captain. If Orunmila had not been so close, she was not sure they would have found anything left of Exeter at all.

“Launch shuttles,” Greg was saying. “Emily, draw those snipers off the PSI ship. Galileo, head to Exeter’s other side.”

Galileo moved upward until she cleared Orunmila, then sped opposite the PSI ship to Exeter. Elena watched Galileo’s troop shuttles appear on the tactical readout. Exeter was still fighting, albeit with only one weapons bank—automatic defenses, or did they have crew left to man her remaining guns?—but the bulk of the raiders were focused on Orunmila. Elena frowned. “Why aren’t they protecting the boarding ship?” she asked.

And then she saw it.

Their flyby allowed her an unobstructed view of the raider that had attached itself, leech-like, to Exeter’s charred hull, and she swore when she saw where it was clamped. “They’re over Exeter’s generator battery,” she said grimly, her comm open so Greg would hear as well. Galileo couldn’t shoot at the raider, because taking out that ship would take out the generator, triggering an explosion that would then take out Exeter, Galileo, and Orunmila—not to mention irradiate the travel corridor for weeks.

“I see it, Chief,” Greg said. “Anything from Exeter at all?”

“Their comms are all dead.” But they were still firing that single gun, and making more shots than they missed. She didn’t think their traumatized automated system would be making such accurate shots. Surely there were still people inside, alive, fighting. People who could handle invaders on foot.

Then again, maybe it was only wishful thinking.

Elena saw half a dozen drones peel off Orunmila to follow Emily’s shuttles as they docked on Exeter’s intact side. Ted tracked and shot two of them, and Orunmila three; the shuttles handled the last one, maneuvering themselves against Exeter’s dark hull. “Stay on them, Ted,” Elena said, but Ted was ahead of her, taking out every drone that angled for an attack. One of the raiders caught the wing of one of the shuttles as it docked; she winced, but the shuttle fired in return, and the drone disintegrated in a silent flare.

Who’s hurt? Who’s hurt? Who’s hurt? But there was no time for that now. “Galileo, what’s the status of the limpet?”

“Engines are on standby,” Galileo said. “Internal atmosphere and gravity normal. Field generator running two-thirds above recommended levels.”

She switched her comm to the captain. “Greg, bring us around by that attached ship.”

“We can’t fire on her,” Ted warned.

“Not until she detaches,” Elena agreed. “But when she does, she’s going to rabbit. She’s half spun up already.”

His eyes widened. “A ship that small? She’ll pull herself to pieces.”

“And save us the trouble,” she said grimly. “She’ll need to pull away from Exeter to build the field without the whole thing going up.”

“Not a suicide mission, then.”

“When have raiders had the nerve for suicide?”

He threw her a nervous grin, and hovered over the tactical readout. “Galileo, target that ship. As soon as she’s minimum safe distance from Exeter, take her out.”

“Minimum safe distance is undetermined,” Galileo said calmly. “Calculation depends on unknowns.”

Galileo meant cargo, and possibly fuel levels, not to mention potential booby traps. “Manual targeting, then,” Elena instructed, meeting Ted’s eyes. “Watch that ship. Watch how it flies. If we assume they want to survive, they won’t take a risk. There’ll be a tell.”

She hoped she was right.

“The limpet is powering up,” Galileo said helpfully.

“Ted,” Elena began, “keep your—”

Before she could finish, all of the remaining drones turned in unison toward Galileo, and, like a flock of southbound birds, began flying with determined speed directly toward the ship’s midsection.

She swore and fired, Ted next to her doing the same thing, but there were too many of them. Galileo’s weapons caught drones, over and over: twelve, eleven, ten … but they were firing too slowly, and her mind’s eye saw Exeter: one second whole and intact, the next second flaming scrap. All those people dead, and here she was now with her own people, just the same …

… and the great, alien shape of Orunmila rose between Galileo and the oncoming raiders, so fast that fully five of them immolated themselves against her hull. Elena trusted the PSI ship’s pilot to do her job, and kept firing, her eyes flicking among the remaining raiders, watching them flame into nothing one by one.

“The limpet has detached,” Galileo said.

Four raiders.

Three …

Two …

One.

“Status of that ship!” she shouted.

“FTL field is powering up. Entrance in three seconds.”

It was too close. The risk of discharge against Exeter’s remaining power sources was huge. So much for no risk, she thought, furious with her mistake. They would not be in a position to take a solid shot anyway; if they caught the ship as the field was enfolding it, they might all get pulled to pieces.

Galileo spoke again. “Orunmila is targeting the raider.”

Blindly, Elena opened a channel to the PSI ship. “Orunmila, you can’t fire on that ship! Exeter’s generator battery is on that side, and the field—”

But it was too late.

Elena watched, helpless, her eyes leaving the tactical readout to look out the window. She saw the small bright projectile speed toward the escaping raider as the raider began to glow that familiar blue-white, the sharp edge of the developing field becoming defined around it. Maybe it would escape, and Orunmila’s shot would go wide, dispersing itself harmlessly into the vacuum.

I don’t think this is going to be that kind of a day.

The shot connected, and Elena held her breath … for nothing. The field folded cleanly around the Syndicate ship, and it vanished.

An unfamiliar voice came over Elena’s comm. “Galileo, this is Orunmila.” The woman’s voice was warm and melodic, her accent subtle, all soft consonants and low vowels. “We fired a tracker. Our apologies for alarming you.”

Suddenly Elena could breathe again. “Our apologies for doubting you,” she replied. “And thank you.”

“And you, Galileo.” The connection dropped, and it was only in the silence that Elena wondered if that musical-voiced woman had been Greg’s irritable Captain Shiang.

Elena flew Greg, Jessica, and three computational experts in a shuttle designed to carry four. Ordinarily Jessica would have made an acidic joke about the close quarters, but Elena’s usually irrepressible friend was silent, her normally sharp green eyes watching absently out the window as they approached Exeter’s carcass.

Which is what it is, Elena kept telling herself. Despite the oxygen and gravity still intact in pockets. Despite the fires still sputtering out from the shattered systems that still had a power source. A full third of the ship’s structure was gone; the rest of her could have been in perfect shape, and Central still would not have elected to repair her. Exeter was fifteen years old, near the end of her expected life span; but even a newer ship would have been decommissioned and listed as scrap. Despite their reliance on technology and science, the Corps was not without its institutionalized superstitions, and nobody would ever knowingly serve on a ship that had lost a battle like this one. Exeter, just that morning humming and perfect and home to four hundred people, was as dead as if there were nothing left of her at all.

Elena had been bitterly unhappy during her deployment on Exeter. Her escape to Galileo had felt like fleeing a prison. But she had friends who had stayed behind, had thrived, had loved the place as their home, just as she loved Galileo.

She fixed her eyes on the schematic of Exeter that the shuttle had superimposed over the front window, looking for an open docking conduit. She avoided the urge to look over at Greg. She knew he was worried about her, but he would never say anything in front of the others. He knew all about her experiences on Exeter—well, almost all—and he understood the curious attachment that came with one’s first deployment. He would know she was upset, too, know she wanted to run through the ship and find out how many of her friends had died. He would also know she would not indulge the wish, that she would do her duty to the best of her ability. And he would count on her to tell him if she couldn’t cope, even knowing what the admission would mean to her.

She was recognizing more and more often lately how well he knew her, despite all the ways he did not know her at all. A year ago, before she had learned she knew nothing of him at all, the thought would have been comforting.

Greg commed Commander Broadmoor shortly before they docked. “Where are we?” he said.

“We’ve got thirty-seven survivors so far,” the security chief told him. “No raiders yet. There are dead spaces between us and Control that we’ll need to physically bridge. And the core is silent, which means we’re stuck on external comms. The faster we can get past that, the easier it’ll be to sweep the ship. Do you have Lock—uh, Commander Lockwood with you? We could use her expertise.”

Up until seven months ago, Jessica had reported to Emily Broadmoor, and the security chief still sometimes forgot to address her with her new rank. Elena had been worried, in the beginning, that Emily would resent Jessica’s being promoted over her, but as it turned out Commander Broadmoor was pleased. “Amazing hacker,” she had confided to Elena, “but as a subordinate? What a pain in the ass.”

Elena docked the shuttle, and one by one they lowered themselves into what remained of the CCSS Exeter. The corridor was dark apart from the dim light coming from the shuttle, and she pulled a loop of emergency lights from her toolkit, pressing the glowing blue strip to the wall. Here the corridor was untouched, the wall and floors undamaged, the only evidence of injury the stillness and the dark. She could hear the hiss of the environmentals, but none of the mechanical hum of the engines. Which made sense, she realized belatedly: the engines were gone. The environmentals were likely running on batteries, and she struggled to remember how big a bank Exeter carried. “The systems won’t last more than twelve hours,” she told Greg, doing the math in her head. “We need to pull some emergency packs over from Galileo.”

He commed back to their ship as Emily came around the corner, a dozen infantry flanking her. She gave them a crisp salute, and turned immediately to Jessica. “Think you can get us talking, Commander?” she asked.

Elena and Greg left the technical people to their work and moved to the infantry. These were combat soldiers: broad, well-muscled, and well-armed, and Elena hoped they would be superfluous. Greg picked off half of them and put them under Elena’s command. “I need you to get down to engineering,” he told them, “or what’s left of it. Chief, see what you can find there, if there’s anything we can postmortem. And I want to know what that limpet left behind at the entry point. The quicker we can identify the tribe, the quicker we can shut the bastards down.” He met her eyes then, for the first time since they had been sitting in his office idly writing reports. Ten minutes ago? Five? “You stay on the line, Chief. Understand?” He didn’t wait for her answer, but turned to frown at the infantry. “All of you. Thirty seconds goes by without someone telling me what’s going on, I’m assuming an emergency situation and we go after you, weapons hot.”

Nods all around. Elena stepped into the group, feeling oddly slight despite being taller than four of them. She knew what worried Greg: Exeter had almost certainly been boarded. And without knowing why the raiders had come, they had to assume something—or someone—had been left behind.

CHAPTER 4 (#ulink_92f7bd57-ce08-50a3-b8c6-e3b3c374490f)

Exeter

Guanyin had never been on a Central ship before. Captain Çelik had offered once, when she was just twenty-one and in the early stages of her training with Chanyu. She had desperately wanted to go, but Chanyu had politely vetoed the idea, and Çelik had not asked again. Now, wandering Exeter’s dark, unfamiliar corridors, she wished she had pushed the point, had seen what this lifeless, colorless structure had looked like when it was functional. She might have been able to lead the mission without feeling like she was walking through a tomb.

She had eight of her security people with her, including Cali, who was following a resentful three steps behind. Cali had expended a fair amount of energy trying to convince Guanyin to stay behind, beginning with stating her value as the ship’s captain, and eventually resorting to referring to her pregnancy. But that was not what had made Guanyin shut her down. When the appeal to Guanyin’s maternal instincts had failed, Cali had gone for politics.

“You step on a Corps starship, you’re sending a message,” she had said, in front of the assembled landing team. “You’re implying alliance. Commitment. Never mind Captain Çelik—have you thought about what their command chain is going to think?”

This, she thought, is why you will never be anyone’s first officer, Cali. But even as the rational thought was running through her head, she lost her temper completely. “Who are you to tell me I should leave them to their own devices?” she had snapped. Aida’s head had come up when she said it, and she realized he had never really seen her temper before. A learning experience for him, then. “They are in trouble, and like any other ship in trouble we will help them. And we, Lieutenant, means me.”

Cali had backed down. She had, in fact, said nothing at all to Guanyin since then. Guanyin wanted to shake her for her silliness. Protectiveness was one thing, but Guanyin was the ship’s captain. If Cali had a problem with an order, the place to bring it up was not in front of the whole crew.

She had spoken briefly to Captain Foster before they arrived. All of his glib self-assurance was gone, replaced by a quiet levelheadedness that she liked much better. She had offered Aida’s help in getting Exeter’s internal comms systems linked into the external network, and Foster had accepted without qualification. They were headed toward the bow of the ship to deliver Aida to the comms center, dependent on the schematic Captain Foster had sent over, which he had told her would likely be out of date. That should not have surprised her—Orunmila was being constantly reconfigured; no map but their own dynamically generated schematic would be accurate more than a few weeks—but she had not, she realized, thought of Corps ships as similarly living, changing habitats.

They came around a corner, and Guanyin caught the sound of distant voices. Instantly she halted the group, and snuffed out the lights; for a moment the absolute darkness blinded her, and then she caught a weak glimmer of light far ahead. She turned her own light on, very low, and began creeping forward again; Cali, cured of her snit in the face of her duty, moved in front of her, hugging the wall as she crept forward on quiet feet. Guanyin gripped her handgun—a lethal but short-range model her arms officer had suggested as useful for avoiding unintended hull breaches—and strained to make out words.

She recognized first that they were speaking Standard. Not entirely a guarantee of safety, but most of the raiders she had run across spoke their own dialects, cobbled together from a half-dozen local languages or more, and communicated in Standard or PSI dialects roughly and with thick accents. On impulse, she commed Captain Foster. “Captain, do you have anyone aft of Control?”

“Not yet, Captain. We’ve got vacuum between here and there. What have you got?”

She was quiet again, listening. “Possible survivors, I believe. I will let you know.” She cut the comm, and nodded to Cali.

They all stopped, and Cali shouted, “Drop your weapons and stand down!”

A flurry of footsteps, the sound of weapons powering up, a series of shouts and murmurs. And then one voice, over the rest: “That’s a PSI dialect, you shitheads. Stand the fuck down.”

Guanyin placed the voice almost immediately. “It’s all right,” she told Cali and Aida. “They’re Exeter.” And striding in front of her friend, she rounded the corner.

There were eight of them, all standing on their own two feet, she noted with relief. Despite the stand-down order every one of them still had their hands on the bodies of long pulse rifles—no concerns about hull breaches here. As an afterthought she holstered her own weapon. None of them were in environmental suits, and instinctively she reached up and tugged her hood off. Instantly she was hit with the odor of burning electricals and ozone, combined with the pungent odor of human sweat. Just like home, she thought, and approached the tall man at the head of the group.

“Commander Keita, I believe,” she said, and held out her hand. “I am Captain Shiang Guanyin, of Orunmila.”

She did not think he would remember her. She had met him briefly, two years ago, shortly after he had been promoted, during one of the supply missions they had performed with Exeter. He looked older than she remembered, but otherwise she was struck by the same things: his wide, thick-necked build that made him seem even taller than he was, the chiseled, almost cruel handsomeness of his square, dark-skinned face, the strange softness of his brown eyes that made her think of an artist more than a soldier. She recalled his smile, which had moderated his features considerably; he had been quick-witted, she remembered, friendly and professional in a way that had put even Chanyu at ease. She had liked him immediately, and she felt an unexpected wave of relief at seeing his face.

He took her hand, and a shadowy version of that smile passed over his lips. “Good to see you, Captain. And thank you for stepping into the battle when you did. Without you, we’d have been dust before Galileo arrived.”

“I am grateful we were close,” she said sincerely. Beside her, Cali was radiating disapproval. “This is Lieutenant Annenkov, in charge of my security, and Mr. Aida, my comms officer. We are trying to rendezvous with Captain Foster in the bow of the ship.” She cast her eye over the rubble beyond his people. “It might be faster for us to go back to the shuttle and fly to the other side.”

Keita’s lips tightened, making him look grim again. “Captain Çelik is on the other side of that,” he explained. “He was heading from Control down to engineering—or what’s left of it—to find out what the fuck was going on with our guns, and we took a hit.”

All of her relief vanished. “What do you need?”

“Beyond shifting all this debris? Structural support, I think,” he said. “There’s no vacuum on the other side, but this whole section got hit hard. We can’t be sure we won’t be pulling the whole ceiling down by digging out.”