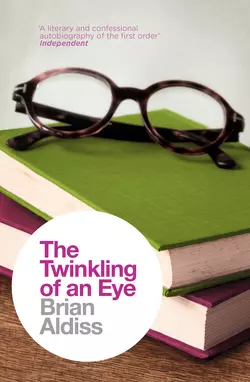

The Twinkling of an Eye

Brian Aldiss

Writer, soldier, bookseller, father: Brian Aldiss has earned many titles in his life. In the Twinkling of an Eye is a candid, vivid and charming look at the stories behind this distinctive writer of fiction.His life as a struggling novelist is unflinchingly laid bare. There are recollections of the beauty and freedoms of Sumatra, the camaraderie of the army and the sobriety of post-war England, bookselling in Oxford, marital breakdown and financial impoverishment. With insight and honesty, Aldiss delves into his role in the new wave of science fiction writing in the 1960s, and his friendships with his contemporaries: Anthony Storr, J. G. Ballard, Kingsley Amis, Doris Lessing, Michael Moorcock and William Boyd.This is Aldiss at his most-versatile, outspoken best.

BRIAN ALDISS

The Twinkling of an Eye

Or

My Life as an Englishman

Copyright (#uf6e7efb3-311b-598a-926c-6a7d2bc97f8f)

HarperVoyager

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpervoyagerbooks.co.uk (http://www.harpervoyagerbooks.co.uk)

This ebook first published in Great Britain by HarperVoyager in 2015

Copyright © Brian Aldiss 2015

Cover layout design © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2015

Cover photographs © Shutterstock.com (glasses on books); Mayang Murni Adnin (wood texture)

Brian Aldiss asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 978-0-00-748258-0

Ebook Edition © July 2015 ISBN: 978-0-00-748259-7

Version: 2015-07-01

Epigraph (#uf6e7efb3-311b-598a-926c-6a7d2bc97f8f)

If we apply to authors themselves for an account of their state, it will appear very little to deserve envy; for they have in all ages been addicted to complaint…Few have left their names to posterity, without some appeal to future candour from the perverseness and malice of their own times. I have, nevertheless, been often inclined to doubt, whether the authors, however querulous, are in reality more miserable than their fellow mortals.

Samuel Johnson:

TheAdventurer, No. 138

It was on 15 November, 1990, in the gloom of winter, as I sat in the car with my wife, a tape of old Jugoslav folk music playing, that I beheld the town where I was born, much changed, and decided to begin the toils that would result in my creature, my book.

The story of my life – to me so individual, yet objectively so commonplace! Myself now subject to decay, I have witnessed the decay of countries, empires, and ideologies; to counter-balance which, I have enjoyed the growth of my own family and survived to see the continuation of my line…

Contents

Cover (#u5c9f29eb-0adf-5d2d-8cfc-3198d5e4a16e)

Title Page (#ue69c0c84-ba18-5bad-97a8-7a7b0d81e32d)

Copyright (#ud5c725c9-ce86-5e91-9224-88a4eb459215)

Epigraph (#ufb9fad05-461f-5966-a25e-3bfeb7f4bb96)

BOOK ONE: Necessitations (#u7a13b5a5-3d3f-5c84-ab42-97f989ec9605)

Chapter 1: The Voyage (#u921c27f9-36ca-54a8-937c-470a45d70705)

Chapter 2: The West Country (#u3553ad82-5c29-5c3b-8633-b48aea86f4f3)

Chapter 3: The School (#u12d3203d-ca84-5ee7-9a1a-1cf2c25e190c)

Chapter 4: The Old Business (#u382946d2-87d3-5dc1-ad17-e4ee3baf5e6c)

Chapter 5: The Small Town (#u538e6e01-896d-56fa-8394-8b56f1584781)

Chapter 6: The Parents (#u688c9873-a86f-53f8-b981-a66d5f786512)

Chapter 7: The Exile (#u8fab37e1-5761-53ca-add0-908994d7bdf4)

Chapter 8: The Decision (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 9: The Refuge (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 10: The Transcendence (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 11: The Ghost (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 12: The Enchanted Zone (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 13: The Advance (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 14: The Forgotten Army (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 15: The Bomb (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 16: The Renaissance (#litres_trial_promo)

BOOK TWO: Permissibles (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 17: The Funeral (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 18: The Homeless (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 19: The Jugs (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 20: The Sixties (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 21: The Writer (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 22: The Future (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 23: At Large and Leisure (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 24: The Global Dance (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 25: The Sicilian Yacht (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 26: The Wilderness (#litres_trial_promo)

BOOK THREE: Ascent (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 27: The Fog (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 28: The Secret Inscriptions (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 29: The Two Suns (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 30: The Hill (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 31: The Years (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 32: The Black Desert (#litres_trial_promo)

Envoi (#litres_trial_promo)

Picture Section (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

Also by Brian Aldiss (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

BOOK ONE (#uf6e7efb3-311b-598a-926c-6a7d2bc97f8f)

1 (#uf6e7efb3-311b-598a-926c-6a7d2bc97f8f)

The Voyage (#uf6e7efb3-311b-598a-926c-6a7d2bc97f8f)

Our anchor has been plucked out of the sand and gravel of Old England. I shall have no connection with my native soil for three, or it may be four or five years. I own that even with the prospect of interesting and advantageous employment before me it is a solemn thought.

William Golding

Rites of Passage

‘Where the hell are they taking us?’ It was a good question.

No one could answer. The troop train wound its slow way northwards through England. The troops, crowded close in every compartment, set up a clatter as they divested themselves of their FSMOs (Field Service Marching Orders), their rifles, their steel helmets, their kitbags. Then silence fell. Some men read whatever was to hand. Some stared moodily out of the window. In the manner of troops everywhere, most men, when not being ordered about, slept. They had been up before the July dawn and parading by sunrise.

Nobody knew where they were going – ‘not even the driver,’ said one cynic. ‘The driver has sealed orders, regarding his destination, labelled NOT TO BE OPENED TILL ARRIVAL.’

The young soldiers, Scottish, Irish, English and Welsh, were dressed in drab khaki uniform. Although they had been trained not to feel – in the manner of soldiers through the ages – the high spirits of youth showed through: the wakeful ones smoked and joked. Nevertheless, knowledge that they were going abroad to fight induced a certain seriousness. When the round of jokes had died and the stubs of their Players and Woodbines had been stamped out, they seized on the opportunity to put their booted feet up. It would be a long journey.

Reveille had sounded in Britannia Barracks at four thirty. By the time it was light, platoons of newly trained soldiers were marching down to Norwich Thorpe Station. The ring of their steel-tipped boots echoed in empty streets. They piled into the waiting train, goaded on like cattle by their sergeants.

When the train pulled out of the station, wartime security ensured that it was for a rendezvous unknown. Also unknown to the men, impervious even to their imaginations, was how the operation in which they were involved was mirrored by another more sinister operation, taking place even then on the mainland of Europe. In the dawn light of many European cities, cattle trucks standing in railway sidings were being filled with Jews, men, women and children. Shrouded in secrecy, German cattle trains were pulling out towards destinations with names then unknown to the outside world, Auschwitz, Belsen, Treblinka, Sobibor.

Some time during that long English day, the troop train drew into Lime Street station in Liverpool. More troops were crammed aboard. The train continued its sluggish journey northwards, crossing into Scotland. Towards the end of the afternoon, it wound through the poor suburbs and peeling tenements of Glasgow, crawled at walking pace as if exhausted by its journey.

Here citizens turned out to wave and cheer and toss buns and ciggies to the troops. Improvised banners hung from slum windows, saying GOOD LUCK LADS and similar encouragements. Women waved Union Jacks. Bright of eye, the troops jostled at the train windows, waving back. No one on that train would ever forget those warm Scottish hearts.

At Greenock docks, security gates opened, to close behind the train. The train halted with a whistle of expiring steam. With a great bustle and kicking of everything in sight, the men about to leave Britain de-trained. Sergeants gave their traditional cries of ‘Get fell in!’ The troops stood in ranks, rifle on one shoulder, kitbag on the other, now isolated from civilian life.

An entire period of their lives had come to an end. A more challenging one was about to begin.

Towering above the parade, moored to the quayside in the quiet waters of the Clyde, was the troopship Otranto, 21,500 tons. Prior to the war, the Otranto had belonged to Canadian Pacific Steamships, when it was accustomed to making the journey between Vancouver and Hong Kong. Seagulls screamed about its funnels. Orders were shouted. Loaded down with kit, the men climbed the gangplank, forced by its steepness to cling to a worn wooden rail. One by one, they stepped into the open maw of the ship, to be dispersed among its many decks.

So alien was this experience to most men that some were immediately seasick, although the ship lay without motion at its moorings.

Among the thousands forced to climb that gangplank was a lad not then nineteen. He entered the threadbare floating world with some excitement, being at that period of life where everything is novel, and what is novel is welcome. He was in misapprehension about many things; but many of those things, such as his emotional nature, he was able to set to one side under the greater urgencies of war. With energy and resource, he set about finding himself the best possible position on his allotted mess deck, in the depths of the ship.

He also pursued a line of conduct developed long before at school, that of making light of circumstances by joking with his fellows.

When he left home at the end of his embarkation leave, this young man promised his mother, Dot, that he would write home regularly. This promise he kept over the next four years.

Owing to Dot’s dedication, the letter I wrote home after boarding the Otranto, complete with its inked illustration, was preserved. It shows me in ebullient mood.

Now as I write it’s nearly sunset, with the sun flaming over the waters. Although we have moved away from the port, we’re anchored in sight of land – our land … I’m writing on a raft on the Boat Deck and a chap with a ukelele is leading community singing. (They’re just singing ‘Lili Marlene’: ‘Orders came for sailing Somewhere over there …’)

I don’t actually know how I feel. It’s difficult to describe. Everything has a dreamlike quality, we don’t quite believe it … But I’m trying to record all I see, and store everything that happens in my imagination. It’s certainly going to be interesting!

A new life’s ahead but, boy oh boy, we’re ready for it. Please try and don’t worry. As yet I’m enjoying myself – and it’s broadening my mind …

Some phrases in the letter, such as ‘broadening the mind’, were family catch phrases, jokes.

Wartime security decreed that we should never reveal where we were. Troop movements could provide useful information to the enemy. In everything – as in family life – there was secrecy. And England was a kind of family in those years. A companion poster to the ones saying ‘Careless Talk Costs Lives’ admonished more gently: ‘Be Like Dad – Keep Mum’.

The Otranto had been christened The Empress of Canada at its launching in 1922. Came the war and its feminine name had been ripped from it. Refitting on a large scale had taken place. It had been painted a North Atlantic grey from stem to stern. Just as those climbing up its gangplank had suffered the severest haircut of their lives, so the old ship had been shorn of its luxury trimmings. Except, that is, in the officers’ quarters.

Under cover of dark, the troopship slipped away down the Clyde, past the Isle of Arran and the pendulous Mull of Kintyre, round the sleeping north coast of Northern Ireland, to where the shallows of the continental shelf gave way to deeper waters – still the haunt of Germany’s U-boats at that period.

Dawn came. Ships, naval and merchant, were gathering, and spent the day manoeuvering into formation. Towards sunset we began to move. The cold grey ships slid into the cold night. Possibly twenty-eight ships all told, forming the last of the big wartime convoys. The strong heartbeat of the Otranto’s engines was never to leave us over the weeks to come.

No smoking allowed on deck. The glow of a cigarette could be seen seven miles away.

Only the captain knew our destination. North America? The Middle East? Not, with luck, not India! India meant Burma. Our progress southwards consisted of a series of long zigzags, to west, to east: a manoeuvre against an enemy who still patrolled Atlantic waters. Yet by July 1944, the tides of war were turning in the Allies’ favour. No more was the Mediterranean Mussolini’s mare nostrum. Malta had survived more bombs than fell on London, Rommel had been defeated in North Africa. Our convoy was to be the first one not forced to sail by the longest route, travelling round the Cape of Good Hope, calling in at Durban for shore leave.

We sailed into the Mediterranean, through the narrow mouth guarded by the Rock of Gibraltar. Part of our destroyer escort left us, turning back into the prison-hued Atlantic. Suddenly, the sea was blue, sea birds cried, the great rock sang to port. Northern Europe had sunk below the horizon. My sails filled with excitement. The world looked wonderful, basking in balmy air. At sunset, a great warm breath was exhaled from the African coast, the very aroma of all that was exotic: perfume, camel dung, armpits of Oued-Nails, apricots, limes, other unknown fruits, frangipani, and the entrails of Arab towns.

Five thousand men were packed aboard the Otranto. On each deck, men, crowded like slaves on the Middle Passage, ate their food at mess tables, lived and slept there. So cramped were our quarters that half the men slept overhead in hammocks, while below them slept the other half, flat on the deck on palliasses.

The Otranto had five or possibly six decks above the water line: Sun Deck, Promenade Deck, Boat Deck, where the officers were quartered, A Deck, B Deck and C Deck. The detachment I was with was down on H Deck, the lowest deck in the ship, Damnation Deck, Doolally Deck, Dead Duck Deck, five decks below the water line, carved out of the very keel. To escape to the Boat Deck, the highest deck on which Other Ranks were allowed, entailed a long climb upward, through other crowded decks. Had a torpedo struck us, no one of H Deck would have stood a hope in hell of survival. We knew it.

But underlying the crowded discomfort of the ship, and the tedium of life aboard, went excitement at a first encounter with a hitherto inaccessible world, danger, and the quest for a drinkable mug of tea.

As soon as we were in warmer waters, I slept up on deck. It was permitted, yet few men took advantage of it. Over the rail lived the unceasing sea, heaving as if in the throes of giving birth, often phosphorescent with great sheets of wavering life, murmuring to itself in a green marine dream.

Our only enemies were the matelots. The sailors, hating soldiers, cleansed the decks at dawn every morning and hosed any sleepers with icy jets of sea water. We woke early to avoid them, both sides cursing the other. To return to H Deck was like trying to breathe stale sponge cake.

Of all the troops aboard ship, I seemed almost alone in enjoying the voyage. In the warrens of the ship, looped about with grey pipes of every bore, coiling along the bulkheads or snaking overhead, it was easy to imagine we were on a giant spaceship, heading for unknown planets. It was an enthralling fantasy.

So, in a sense, we were. We passed Malta and Pantelleria. Our first harbour was Port Said, at the head of the Suez Canal.

We passed slowly through the canal, pursued on either side by twin humps of wake. Heaving to in the Great Bitter Lake, we waited while a troopship passed us, heading north, homeward bound for England. Those aboard called mockingly across to us, ‘Get your knees brown!’ We moved at snail’s pace into the Red Sea and a zone of intense heat, where mirages trembled on either desolate bank.

Improvised shower cubicles spurted salt water while we assaulted our bodies with salt-water soap. Emergency urinals – little more than raised troughs – had been clamped on to the Boat Deck. To their notice, NOTHING TO BE THROWN DOWN THESE LATRINES, a wag had prefixed the words IT IS.

By this time, we knew there could be but one destination for us. Burma.

We disembarked on Bombay docks in September 1944. Looking back at the grey walls of the ship, I realised that it had become a kind of womb after thirty days afloat; in the end, we had grown so dependent upon it that we were reluctant to leave.

‘Bags of bull, lads!’

Ever obedient to the sergeant, our platoon got fell in and marched to Bombay’s ArabianNights-cum-Keble-College railway station.

At the cavernous station we had an hour’s wait for our train. An hour to look, to stare, even to speak! The brightness of everything, the nervous energy of the stringy brown men, selling and begging. Here a thousand worlds seemed to be contained, with fascinations inexhaustible.

Our train slunk into its designated platform and we climbed aboard, humping our kit. A whistle blew. We had three hundred miles to go, to Mhow, in Central Provinces.

I described it in a letter home.

We travelled third class on the train. What coaches! – Wooden, ramshackle, a square box for a compartment, ten feet by ten feet, and the seats made for a race that slept on nails. No window glass, no spitting allowed. Eight bells sound, the natives scream, the train gives a compulsive jerk forward …

Night swooped down. We smeared anti-mosquito cream on hands and face, and rolled down our sleeves. The winged wildlife of the place soared in and cavorted round the light. From the darkness came hoarse croaks of bullfrogs and the high-speed Morse of crickets.

A considerable portion of the native population sleeps on the stations. They burn herbs which smell strange and musky – whether pleasant or foul you can’t quite decide.

We fell asleep uncomfortably, one way or another. When I awoke it was dawn and the sun, donning rouge and roses, climbed back to heaven. Allah be praised! We wiped the mozzy ointment off.

The train clattered through rocky ravines, tree-covered land, wide plains. Strange trees, tropical birds. Parrots and monkeys we saw in the wilder parts. Round the villages cluster padi fields, maize, and what-have-you. The beasts of burden are humpbacked cows, oxen, and sturdy black water buffalo, which wallow in mud holes when they get the chance.

The further we travelled into the interior, the greyer grew the rags and clothing of the people, and the fouler and more frequent became the beggars. We saw old vultures, hawks, and lizards a foot long. Goats roamed the stations. All these attractions palled as we became dirtier, hungrier, and more tired.

It poured with rain, steady beating rain, a reminder that the monsoon was not yet over. We put up the shutters. Night fell, and still it rained.

It rained when we reached Mhow station. Hauling our kit – kitbags, mosquito nets, blankets, big packs, respirators, rifles – we crossed the station to where lorries awaited us. We bumped over to the cantonment …

The rain stopped and the night smelt good. In the dim lighting our quarters seemed like a palace: paved floors, lofty ceilings, white paint. By morning light it looks more like a barn!

It’s all very fascinating. Tomorrow I hope to look over the village, which seems quite large. We shall spend a month here.

In short, everything’s fine, mighty fine.

The train journey to Mhow was the first of many journeys, since the train was such a feature of Indian travel at the time. However long, however arduous the journeys, the spectacle of India itself mitigated the tedium.

Mhow, the village, is best remembered in its picture-postcard aspect, when strident day suddenly marries velvet night and the flying foxes, waking in the tall acacias, take flight for distant fig trees. Summer lightning flickers all round, flirting with the horizon, nervy, noiseless. Then kerosene lamps on stalls lick their yellow tongues, making the bazaars enigmatic. Weird music crackles from radios, and a whole new mystery envelops the world.

In Mhow was a Signals training centre, designed to toughen us up after the voyage, in preparation for more arduous times in Burma. Oh, the wriggling and conniving, the malingering, which went on among men who wished to avoid action in Burma at all costs – including, presumably, a cost to their self-esteem. You see clever soldiers who have found a rock to cling to – barnacles with a job in the quartermaster’s stores or service as an orderly in the hospital. Others, perhaps, become base wallahs and box wallahs in New Delhi, to serve out a safe and boring war, until it is time to return home with a Long Service medal and nothing to report. Anything, rather than be involved with the shooting war further east. My own attitude was that the dice should be allowed to fall where they would. This time was an awakening for me, as no doubt for many others. Such personal matters were never discussed. But I had left behind, not only England, but an inadequate earlier self, as the times demanded.

Much in the Army was startling, not least the chorus of complaint that rose on every side about everything. Many older men had been wrenched from jobs or marriage. They resented a violent disruption to their lives; whereas for me the East was life, life at last.

For me, novelty overrode any discomfort. The pre-dawn runs, the petty restrictions, the training, the shouting, caused me little pain: I had survived ten years in boarding schools under rather worse conditions. For this at least the public-school system could take credit: it accustomed one to hardship and injustice.

The war for many provided a kind of release from personal problems. The question bothering humanity, or an intellectual fraction of it, at least since the days of the ancient Greeks, was summarised by H. G. Wells in the touching title of one of his books, What Are We to Do with Our Lives? This dilemma was resolved, or at least shelved, by hostilities. Family conundrums were of no moment when one was issued with a Sten gun.

It is this kind of effect that makes war so popular.

Japanese military operations had been widely successful in the Far East. Events unravelled rapidly after the bombing of Pearl Harbor on 7 December 1941.

Hong Kong fell on Christmas Day. On 15 February 1942, the supposedly impregnable base of Singapore fell to a Japanese army. Thirty thousand Japanese confronted 85,000 British and Commonwealth troops. Shortly before the end, General Perceval, in command of the Singapore garrison, sent a message to Churchill in England: ‘Have 30,000 rounds of ammunition. What shall we do with it?’ Churchill cabled back: ‘How about firing it at the enemy?’ The suggestion was not carried out. Perceval surrendered, delivering the Commonwealth troops to a bitter imprisonment. A black day for the British Empire.

Two Japanese divisions had already advanced into Burma. Mandalay was taken in May of that year. Disaster and disillusion followed.

The Japanese became regarded as invincible, while their cruelty to the Chinese and other races who fell under their control was such that they were regarded almost as a sub-species of the human race. Their ability to live and fight in dense jungle caused the British to regard them as superhuman.

Clearly, the war in Europe was to be preferred as a theatre in which to fight. Death rates for prisoners captured by German and Italian armies amounted only to some four per cent, whereas under the Japanese the rate was twenty-seven per cent – higher still on the notorious Death Railway.

At this distance in time, it’s hard to recall the particular hells conjured up by the very name Burma. Our attitude towards the Japanese was compounded of a toxic mix of reality and racism.

In 1941 and 1942, Japanese advances in seven months were more spectacular than any of Adolf Hitler’s blitzkriegs. The wolves came down by boat, plane and bicycle. Their fleets crossed over 3,000 sea miles, their armies engulfed much of China, Hong Kong, the Philippines, Indochina, the Netherlands East Indies, multitudes of Pacific islands, Malaya, Singapore, and Burma, advancing westwards until they stood at the very gates of India. They struck to the south, deeply enough to launch air raids on Darwin in northern Australia. They were a fever virus on the body of the East. Wherever they went, Japanese armies behaved with punishing ruthlessness.

These were the facts we chewed over in Mhow as we handed in respirators lugged all the way from Norwich. We drew jungle green battledress and handed in the absurd KD – khaki drill – and topis with which we had been issued in England. We exchanged gaiters for puttees. Puttees protected ankles and lower legs from venomous things which could be hiding in long grass.

Two Japanese divisions entered Burma in January of 1942. With them went the Burma National Army, led by a man who knew the ground, Aung San, a courageous Burmese destined to fight on both sides in the war, and to father an even more courageous daughter, Aung San Suu Kyi. These divisions captured Rangoon and advanced northwards on Mandalay, which fell in May. It was another in a long line of British disasters. The British and Indians retreated from Mandalay by car, cart and foot. Only one road led out of the trap. They had to travel westwards on the long trail leading to Dimapur, and the railway line to Calcutta.

British counter-offensives along the Burmese coast and in the Arakan, under horrific conditions, met with little success. They served merely to reinforce the picture of a fiendish enemy who could not be beaten. The Japanese would call from the jungle in the dark, like parrots from a thicket, ‘Hello, Johnny! Hello, Johnny! Who fuckee your missus?’ To fire blindly at the taunting voices was to give your position away.

The struggle for Burma, a country larger than France, is a record of disillusion and heroism on both sides. The main protagonists, Britain and Japan (and the USA, as far as it entered the picture) were far distant from the scene of action. This factor contributed enormously to local difficulties. It explains too why very few war photographers were present to place the struggle on visual record.

Disease – malaria, dysentery and various fevers – accounted for as many men as did Japanese bullets and bayonets. Supplying the British XIVth Army was a very low priority where Churchill was concerned. That army felt itself neglected and abandoned to rot in miserable circumstances. It called itself, in a mood of romantic despair, the ‘Forgotten Army’. The label has stuck, and not without reason.

It was the insignia of that army I stitched on to my jungle greens in Mhow, before our detachment was shipped towards the leafy fighting terrain in Burma.

Not for the first time, my life was about to begin anew. But change, uncertainty, had been a feature of life in the years leading up to the outbreak of war with Germany.

2 (#uf6e7efb3-311b-598a-926c-6a7d2bc97f8f)

The West Country (#uf6e7efb3-311b-598a-926c-6a7d2bc97f8f)

Stop and think sometime about the roller coaster I’m on. Some day on Titan, it will be revealed to you just how ruthlessly I’ve been used, and by whom, and to what disgustingly paltry ends.

Kurt Vonnegut

The Sirens of Titan

Summer – time of innocence, time of wickedness.

In the summer of AD 1938, the Boxbaum family came to live next to the Aldiss family. They came in the night, time of secrets, husband and wife and two children. The houses in Bernard Road, Gorleston on Sea, were terraced. Short paths led straight from the gate, across the front gardens to the front door. My parents went out to greet the Boxbaums, who were exhausted and disoriented. Dot took them a standard English panacea, a pot of tea.

The Boxbaums, driven by Nazi tyranny, had arrived safely in England.

Frau Boxbaum was slight and raven-haired. She arrived in Gorleston speaking no English. The boy was about eight, tow-haired. His sister was probably ten or eleven, a pretty girl, dark-haired with eyes of Aegean blue. They were the first foreign children we had met. Playing with us, they mastered English very quickly; we were impressed, it had taken us years to learn the language.

Mother lent Frau Boxbaum cutlery and plates and various necessaries. The family had escaped with very few possessions. The behaviour of my parents – and of other people in the road – was exemplary. Carpets, rugs, an armchair, curtains, other necessities, arrived at Frau Boxbaum’s door. Bill, if not anti-Semitic, had talked freely of ‘Jew boys’, subscribing to the mild (mild?) British anti-Semitism of the time. That was all put away for this special case. The curtain had been lifted on what was happening in Germany.

Frau Boxbaum had brought some photograph albums with her. We looked at pictures of smiling family groups as she turned the pages, trying out her few words of English. Her foreignness held the scent of a wider social sphere than ours, comfortable and yet doomed. These vistas excited Betty and me, already impatient with a knowledge of our provincialism. Other horizons, other costumes, other rooms.

They had lived well, in a large mansion somewhere outside Hamburg. Flowers on side-tables, salon paintings on walls. Plenty of servants, extensive grounds, cream-coloured automobiles with chauffeurs, family picnics in the countryside.

Not unlike the Boxbaums, our family too had come down in the world, from prosperity in East Dereham to a cramped little terraced house called Number Eleven. We felt ashamed for the Boxbaums, descended from luxury to a little hutch in Bernard Road.

Herr Boxbaum was an elegant man who spoke faultless English. Once he had seen his family settled safely in England, out of Himmler’s clutches, he determined to return to Germany, to salve some of their worldly goods ‘before things got too bad’. He kissed his wife and children goodbye and sailed for Hamburg.

His wife waited for him to return. He never did. The Gestapo caught him. I assume he died in a concentration camp.

The failure of Herr Boxbaum to return from Germany was a watershed, not only for his unfortunate little family. Bill no longer said there would be a war if Winston Churchill did not stop annoying Hitler; instead he warned us that war was coming. And for that event he made sensible preparations.

In that hot summer of 1938, I walked into town and back to buy my favourite magazine, Modern Boy. Nobody was about. The streets were deserted. The air was heavy, windows were open. Every radio in every house was tuned to the Test Match. It was England’s innings. Len Hutton was notching up remarkable scores against Australia.

Modern Boy had rearmament stamps to collect, battleships, tanks, heavy guns. I was excited; Mother said, ‘That’s nothing to look forward to.’ Neville Chamberlain was preparing to fly to Munich to discuss the fate of Czechoslovakia. In the house next to us, on the other side to the Boxbaums, Mrs Newton – devoted to her afternoon bottle of gin – threw open her bedroom window and screamed, ‘Help! Help! The Spaniards are coming!’

A correct statement in essence. Only the nationality was mistaken.

Perhaps in every childhood there comes a defining moment when, by some trick of behaviour, one is made aware for the first time of one’s own character, and that one has a personal idiolect of beliefs. And possibly that moment of insight – which remains always in memory – is a herald of one’s adult nature.

As a small boy of three or four, I was taken by my parents to a tall narrow stone house in Wisbech, on the Wash. There, among a muddle of armchairs, lived a number of distant cousins on my mother’s side of the family.

Permitted to run out into the garden, I saw among a clump of irises the perfect webs of the chubby-backed garden spider (araneus diadematus). I had admired this pretty spider, and its industry, in my grandmother’s garden in Peterborough. The intricate construction of the web was a task I had watched with respectful attention.

A passing butterfly, a cabbage white, flew into one of the webs. As its struggles began, a small girl in a white frock rushed from the house. Seeing the plight of the butterfly, she screamed at me to save it from the nasty spider.

Although I was keen to please the girl, I could not but see the matter from the spider’s point of view; in hesitating, I allowed her to rush out from her corner and seize upon the butterfly. The girl was distressed, and ran back into the house in tears, saying how horrid I was. Well, I too felt it was gruesome; but the butterfly’s agonies were brief and the spider had as much right to live as anyone.

Heaving themselves up from their armchairs, emerging from the house, angry distant cousins gained proximity. I was seriously scolded and ushered indoors – unfit to stay in their nice garden.

Upset though I was – and feeling a degree of guilt – I knew the grown-ups were wrong. The sundry shortcomings of nature, like the way in which we all ate each other or perished, were givens with which one had to live. In the circumstances, observation made more sense than interference. Unfortunately, this has become rather a lifetime principle.

Dot and I watched Bill as he rubbed black Cherry Blossom boot polish into his sideburns, which grey had already invaded. Preparing a lie about his age, he walked down to the recruiting office in Gorleston and volunteered for the RAF. He could still fly. He was lean and fit, forty-eight pretending to be forty-two. The recruiting officer turned him down. Bill was a brave man, and was shaken by this rejection.

His thoughts then turned to our safety. We could see the North Sea from our attic window. When war came, we would be shelled or bombed – or, of course, invaded. Bill decided therefore that we should move to the other end of the country.

In the school holidays of summer 1939, Betty and I walked barefoot from the house down to the beaches and promenades, to spend our whole sunny day there as usual, on the sand, in the sea, chatting to shopkeepers, sailing a clockwork speedboat in the yacht pool, or watching the Punch and Judy show (every scene of which we had by heart).

The front at Gorleston provided a spectacle of which we never tired. It was safe and peaceful. Somewhere across the sea, the tyrannies of Nazi Germany and the more firmly entrenched regime of Stalin’s Soviet Union were busy at their gruesome tasks of enslaving and killing whole populations.

But the British Empire was safe, the colour bar securely in place in its colonies. Tea was still served at four, while the Yankee dollar was worth only two half-crowns.

Betty and I were happy in Gorleston. When I fell ill and was confined to bed, I wrote and illustrated a long verse drama set in Victorian times. The story moved freely from a stage play into real life and back. Where I got the idea from I do not know; now it is a commonplace of deconstructionists – a word unknown in the thirties. It was my first sustained piece of writing. Its subject was the question of appearances: something was happening but – wait! – it was merely being acted!

From the local Woolworth – then still ‘The 3d and 6d Stores’ – Betty and I bought issues of McGlennan’s Song Book. In triple columns, it published the words of the latest popular songs. Betty and I sat in bed together, singing songs made famous by Hutch, Dorothy Carless, Gracie Fields and others: if not melodiously, enthusiastically.

Being mere children, Betty and I were not privy to Bill’s plans. One day, we were hauled in from the beach and told we were going on holiday to the West Country, to Devon.

The Bernard Road house was closed up, our beloved cat Tiny was left in a neighbour’s care. We then undertook a trek across the south of England, arriving eventually at Witheridge, in the middle of Devon. Norfolk born and bred, we were impressed by, or perhaps a little contemptuous of, the hills and valleys; we had grown to prefer a flat world. In Witheridge we stayed on Thorn’s farm, where the young farmer’s wife fed us enormous breakfasts and evening meals. My fourteenth birthday occurred on the farm; my parents gave me a watch.

The sights, sounds and smells of the farm absorbed all our attention. In Witheridge, they had never heard of Hitler. Bill had his gun, went out shooting rabbits, was a countryman again, trying to forget his recent disasters in East Dereham.

The time of childhood was not entirely over. Whatever my new watch said, hours and days were still dawdling by. On the farm we had for company other creatures who did not live in the brisk adult time flow: the calves, young sheep, kittens and the Thorns’ two dogs. We measured out our days in Wellington boots. It was a timeless time – less than a month away from the declaration of war.

We left the farm and drove to a place called Pinhoe, on the outskirts of Exeter, where Father bought a caravan. We had to live in it for two days on the sales area by a busy road until Bill’s cheque was cleared by the local bank.

Towing the caravan, we drove to Cornwall, sleeping overnight – sensation – in a farmer’s field. Next day, we arrived at Widemouth Bay, to the west of Bude. Betty and I had yet to realise that that caravan was actually our home.

Widemouth was a beautiful wild place, not far from Tintagel, legendary home of King Arthur. Sheep had grazed the grass short to the very edge of the cliffs. Contained in the bowl of pasture was a small whitewashed cottage which served as the only shop for miles; it sold milk, bread, and – more importantly as far as Betty and I were concerned – Lyons’ fruit pies, 4d. Just beyond the shop was a sheer drop of cliff to the rocks below, all vastly different from the tame seasides of the Norfolk coast. We climbed the rocks, ventured into deep pools, caught small fish, watched the waters of the Atlantic wallop into barnacled fissures in the cliff face. Whatever I did, my small sister followed faithfully.

Close by the whitewashed cottage, one other caravan stood. From our caravan window we enjoyed a panorama of the Atlantic. How quiet was the Atlantic in those brassy August days! And I ventured at last to pluck up courage and ask Bill, ‘Will I go back to Framlingham?’

He answered casually, as if everything had long been settled in his mind. ‘We’ll find you a school near here.’

Oh, the joy of it! The relief!

War had presented me with an escape from a fate I feared more than anything else. I firmly believed that Framlingham College spelt spiritual death for me. Every day of my three years there was spent in dread.

To give an instance of the teaching, which was Gradgrindian in temperament: our French lessons were devoted to learning irregular verbs, we were not taught to speak French, or to enjoy the beauties of French literature; long lists of irregular verbs offered better opportunity for chastisement. Days were spent moving from classroom to classroom, carting books about, learning how to escape punishment.

Hardly surprisingly, by reflex we punished each other. Carrying those books about, we always put our Bibles on top of the pile. One boy allowed a Latin textbook to lie on top of his Bible. We beat him up.

And the foul hours of night. Arriving within those walls at the age of eleven, I was unaware of sex, except as a sort of game we had innocently played. Sex had been unknown at St Peter’s Court, my preparatory school. That first week in the junior dormitory at Framlingham, the head boy of the dormitory crept into my bed. I was overwhelmed with disgust and shame at his advances, and I feebly pushed him away.

From then on, this sneering bully was always about, always leering at me. Salt in the wound was that his first name was the same as mine. I hated his stupid face, his staring eyes, his winks and jeers, and would have killed him if I could. But he was twice my weight.

That first loathing of homosexual acts remained with me. Rather worse, it left me with a distaste for the flesh for some years.

Perhaps my story-telling in that dorm, at which I became so successful, protected me from further insults of the kind.

So Betty and I played light-heartedly in the rock pools, while time and tide dawdled. It did not bother us that we knew no one else in the world. The sun dazzled on the water, the little crabs scuttled at the bottom of our rubber buckets. We cared as greatly for the events in Europe – the Panzers, the sabres, the fruitless cavalry charges, the Stukas – as did the crabs.

Noon on 3 September. The summer had crumbled away, along with peace. Britain and France declared war on Nazi Germany, only twenty-one years after the last war had run its course. Dot was preparing lunch in our new caravan. Bill and I stood with our neighbour, outside his caravan, where his large wife was frying up. Neville Chamberlain’s voice mingled with the gurgle of sausages wallowing in their fat.

I see it all as if it were a photograph. The world has faded to sepia, along with much else. I described the scene in my novel Forgotten Life. Fiction is often the best medium for such drama, when momentous and meagre clash.

At that solemn time, with Britain plunging ill prepared into war, I went about in a state of sin, secretly rejoicing, I don’t have to go back to bloody Framlingham! May all those bastards there rot! Thank you, God, thank you, Hitler!

That night, we blacked out the tiny square window in the caravan roof, some with fury, others with shrieks of laughter which served to ripen the adult anger.

We woke on the 4th and went running out across the green while breakfast was prepared. There was the wonderful view, the sea, the cliffs, the white cottage. Sheep grazed by the wheels of our car. Wartime!

We were to all intents and purposes homeless. Bill drove into Bude, to return with a key. A bungalow stood empty on the cliffs just above Widemouth. We went to look it over with a builder. Bill was agreeing to rent it by the month, Dot was chirping with pleasure.

Betty danced in the empty rooms. Bill shouted, ‘Come here! Behave!’ Sunlight poured through the front windows. The bungalow was unfurnished, as neat as new, and bereft of everything except a copy of Fantasy, lying alone on a window seat.

On the cover of that 1939 issue, Fantasy: A Magazine of Thrilling Science Fiction, was an imaginative painting of fire engines drawn up in the centre of London, in Piccadilly, fighting off giant caterpillars with jets of plaster of Paris. In a year’s time, the brigades would be dealing with another kind of invasion from the sky.

We moved into the bungalow behind Widemouth cliffs. A few sticks of furniture were bought in Bude. Autumn held its breath: days remained calm and brassy. Looking out of the window at the Atlantic as the sun went down, Bill would say over the frugal supper table, ‘It’s been a lovely day.’ His aggrieved tone comes back to me. ‘It’s been a lovely day.’ On the horizon, black against the sinking sun, our first convoys – those convoys in which I would one day find myself – were setting out for foreign waters. The weather remained too calm for war to be real.

As that ominous season advanced towards winter, the bungalow crouching near the cliffs became more isolated. Over Bill fell a mood of hopelessness. The whitewashed store on the bay closed its shutters. Cars ceased to run along the coast road. Betty and I wandered about the strange wild place, among the gorse, imitating the shrieks of the seagulls overhead, much as Wordsworth’s boy ‘blew mimic hootings to the silent owls, That they might answer him’.

The wet Cornish season closed in. Rain pelted down, rushing to get to the centre of the earth. And when the rain abated, the Atlantic became angry, dashing with such force against the rock below the cliffs that spindrift cracked smartly against our window panes, gust after gust.

Before I was installed in a second public school, Bill and I made what I regarded as an epic journey. Setting out at four in the morning in our Rover, he and I, we drove all the way to Gorleston. It was dark when we started out from Widemouth. Roads had no cats’ eyes in those days. Our headlights were dimmed to meet blackout regulations. We arrived at the house in Bernard Road at about midday.

The Boxbaums had gone from next door. Their house, like others in the road, was closed up. A forsaken dog wandered loose in the street; Dennis Wheatley’s alarming novel Black August came to mind, like a vision of the near-future fulfilled. I still wonder what happened to the Boxbaums, in particular to that girl with the blue Aegean eyes. No doubt the Jewish community took care of them.

Bill packed everything into crates, in preparation for a removal firm to come and the house to be sold up for next to nothing. Nobody wanted to live on the east coast now. I helped him – or perhaps hindered, because he told me to take a walk and look at the sea. I made my way down to the front, where Betty and I had spent our most halcyon days.

In the few weeks of our absence a great change had overcome the town. The bandstand was locked, ‘for the duration’, as the saying went. Everything looked forlorn, with a more-than-mid-winter desertion about it. The lovely stretches of sand were empty. The shops we knew were almost all shut down; some had boarded up their windows with improvised shutters. Barbed wire was being unrolled along the promenade.

Bill and I started back to Cornwall before nightfall with Dot’s canary in its cage on the back seat. The canary sang all the way home. Retrieved from the neighbour, Tiny also accompanied us.

Two events on the journey remain in mind, my tongue-tied awe at being alone with my father at close quarters, and our stop for a cup of tea and cake in Oxford – my first sight of that venerable city. I was excited, and not only at the prospect of tea. The waitresses in the St Giles Café were so slow in coming to serve us that Bill, never a patient man, walked out after a minute or two. I perforce followed.

That was the last I saw of Oxford for ten years.

When I was sent to my new school on the fringes of Exmoor, Bill set about finding work. His nest egg from Dereham looked less generous now. He and Dot drove a long way in search of a viable property. He had always been good at property deals, but the war made values uncertain. A newsagent’s shop in Chard, Somerset attracted him. There was something in Wincanton. Mother liked the idea of a tearoom. Or perhaps a shop in Exeter?

Exeter had many beautiful old features. Some narrow streets were medieval, resembling the Shambles in York. A particularly interesting book shop stood beside the cathedral. Life continued there as normal; how else? Except that some public buildings were fortified by walls of sandbags.

At first, I hated West Buckland. The grounds on which the school stands were donated by a local landowner, the Second Earl Fortescue, in the 1850s. The Fortescue family still live near by and maintain their friendly connection with the school. WBS consists of a series of stone buildings, not unlike a prison in appearance (in the manner of most public schools), well suited to the rather bare landscape in which it was planted. The quads were of an amazing draughtiness, as the wind howled in from the Atlantic, past Morte Point, bouncing over Fullabrook and Whitefield Downs, clowning its way across the Seven Sisters, to arrive in time for morning parade outside the headmaster’s offices.

WBS was heroically uncomfortable. In those early months of the war, everything in the country was in confusion. The school shared in that confusion. Compelled to take on extra boys, many of them evacuated from London, it scarcely knew how to house them. I found myself deposited in an emergency form room with an emergency name, Lower IV A. The room, with its raked desks, had been a chemistry lecture room. The desks were open; nothing could be stowed away in them. Nor were there such luxuries as common rooms. After class, you stayed in the classroom. There was no privacy. The blackout added to the gloom. All around, the winds and rains of Exmoor prowled and hammered at the buildings.

I was completely uprooted. The distance between East Dereham and West Buckland was too great.

I wrote to Bill to say that I wished to be taken away. Answer came from my mother that I would have to stick things out. There was nowhere else to go. My sister, meanwhile, had been sent to a school in Bideford. That did not suit her. She also begged to be rescued. Probably she begged more vehemently than I. She was rescued.

But things sorted themselves out. I was also in the throes of puberty – a rather delayed puberty, it seemed. In the baths after rugger, hulking great dayboys sported clumps of pubic bush, sticking out dismally like Norwegian beards.

A few bubbles foamed from my pipeline, then, at last, the real thing, that phlegm-like substance which makes babies. Puberty is a time of anxiety for boys: will they ever, preferably next week, possess massive dongs like the dayboys, together with thickets of hair like the furze on Hardy’s Egdon Heath? Then, low and behold, the miracle happens! There it is, the new weapon, in the pink, sniffing inquisitively at the randy world … And many kinds of interesting childish thought are doomed: instead you start wondering how you can get hold of a girl, get a hand down her blouse and up her skirt – particularly up her skirt – and feel her all over, to check on the legends you are hearing from all sides.

It must have been about that time I recited, ‘Hush, hush, whisper who dares. Christopher Robin is counting his hairs.’

So there it was. Constant erections to set against the draughty dormitories, the meagre meals, the parades, the clanging of the school bell. Ask not for what the bell tolls: it tolls for your erection.

I grew to love West Buckland. Perhaps it was in my second term, the term when, even on bleak Exmoor, winter yields to spring. The lanes round about East and West Buckland burst forth in primroses, primroses trailing as far as Shallowford, about which Henry Williamson wrote, the hedges fill with birds’ nests, and the nests with eggs. Soon, rugger will give way to cricket.

At Framlingham, we were incarcerated within the grounds, as in a high-security prison. At Buckland, we could get exeats which allowed us to wander the countryside on Sundays. You dressed in your rugger kit, collected some rough-and-ready sandwiches from the kitchens, and off you went in twos or threes. Wild Exmoor! How free it seemed, how strange! Once, Bowler and I saw a stag up on the hills. Shallow streams, ideal for damming, meandered about. And there were pits, corries more correctly, full of pure spring water, paved with pebbles six feet down. We actually took dips in them. They were freezing. We splashed and shouted in agony. Coming out, we pulled on shirt and shorts and ran about howling to restore circulation, yelling and laughing at our own madness.

Beatings at WBS were euphemistically known as ‘dabbing’. The custom was to make no sound while the beating was in progress.

I grew to relish the Spartan aspect of WBS and the grittiness of playing rugger in the teeming rain. But wartime WBS lacked the contrasts needed to fill the bleak hours after prep: magnificent productions of opera and plays, films with talks by travellers, scientific demonstrations to excite intellectual curiosity, rich things. Our form was not alone in enjoying education, in seeking to acquire knowledge. Knowledge is to civilisation what DNA is to inheritance.

The nurture side of school life needed improvement; shutting boys up in teenage monasteries was not the answer. WBS went coeducational some years ago, under Michael Downward, an enlightened headmaster. As one token of his enlightenment, Michael recently made me Vice-president of the school.

Bill settled on a property near Barnstaple, a corner shop up for sale. I felt sadness for my father, and disgrace for myself. What a comedown from H. H. Aldiss’s shop in Dereham! The Barnstaple shop was a small general store. It sold groceries, cigarettes and newspapers, and housed a sub-post office in one corner.

Bill applied himself to this new trade with dedication. He opened the shop out, incorporating a small storeroom into the design. When rationing began, a coupon had to be exacted for every tin of baked beans, every quarter-pound of sugar. All coupons had to be cut from ration books. Accounting had to be done every weekend. Dot ran the post office. Both of them worked day and night, with no time for their children. We lived in tiny rooms behind and over the shop.

The straggling village of Bickington proved friendly. The post office counter gave Mother an ideal conversation post. Her character changed; she became open and genial. The fears and suspicions of Dereham were things of the past. In no time, she was elected Chairman of the local Women’s Institute, and was a popular success. The tradesmen ate out of her hand. Throughout the war, we never lacked for food. Sometimes fresh salmon, poached from a local river, was on the menu.

Cockney evacuees came down from London. The Women’s Institute proved equal to the task, and welcomed them with a reception – tea and music. Among the evacuees was a splendid strapping blond woman, a Mrs McKechnie – plainly a whore, loud and rude, but that traditional thing, a whore with a heart of gold – with whom Dot became friendly.

When the first wartime Christmas came round, I asked Bill if we were going to go to church, as previously we had always done in East Dereham.

He regarded me almost with scorn. ‘No,’ he explained.

It was impossible to make new friends in school holidays. One was there for so short a time. Penny North and I had a pale affection for each other. Betty and I played together, two strange children who got in the way of Bill’s shop activities. We dressed up and made stinks with my chemistry set, yet never managed quite to blow anything up. When she was ill, I made her a book of stories and drawings, The Stock-Pot Book.

One advantage of the cramped house was that you could climb out of my bedroom window on to a narrow ledge, then to another ledge, and from that get down to the ground. At night, I could escape by that route and walk about the blacked-out village.

More interestingly, I could climb out of a rear window, work my way across a rooftop, and get to a skylight in the roof of a defunct bakery. Levering with a screwdriver, I managed to break the catch of the skylight, and so swarm through into the deserted rooms below.

Here I often stood, wondering, wondering. A certain dark-haired evacuee girl had caught my attention. I talked to her over the back wall and offered to show her my precious secret hideaway, but she would not take the bait, or show me her precious secret hideaway.

The bakery was rat-infested. The rats could get through into Bill’s store by the side of the shop and run along a beam at the far end. This store, freezing in winter, had a corrugated-iron roof. Bill developed a hobby. He would stand with his .22 in the kitchen doorway at one end of the store and shoot rats down at the other end, as they ran along the beam, like clay pipes in a shooting gallery at a fair.

Bill had retained his rifles through all our removals. As France fell in 1940, Italy, the Fascist Italy of Mussolini, entered the war against us. Everyone expected that Hitler’s next move would be to invade England. Bill handed me one of his guns.

‘We may have to defend the street. You never know,’ he said. ‘Keep it clean.’

The gun was mine. Later, I almost killed my father with it.

At school, we all joined the OTC, the Officers Training Corps, and wore uniform. I became a good shot. When we weren’t playing rugger or running round the countryside, we went on military exercises through the local farms. The romps were enjoyable, even in pouring rain, when we wore stiff gas capes. One learnt useful things in the OTC, how to read a compass, how to read a map, how to sneak into an out-of-bounds pub for a pint of cider.

The war was going depressingly badly. After the fall of France, Britain stood alone against the horrible black machine devouring the continent. Bill built an air-raid shelter outside the back door. Dot bought a wind-up gramophone to cheer us up when air raids were in progress.

Once, when a raid was on, we trooped down to the shelter and sat there for an hour or two by candlelight. The shelter proved to be rather damp. After that, Bill used the place as a bacon store, while Betty and I took over the gramophone, on which to play, among other favourites, ‘The Ferryboat Serenade’, ‘Elmer’s Tune’, ‘Green Eyes’, ‘The Hut-Sut Song’ and ‘The Memory of a Rose’.

We lay awake at nights, listening to Dornier engines, like an ischaemic event in the lower cerebellum, as Goering’s Luftwaffe flew overhead. The Dorniers came in squadrons, passing very slowly, throb-throb-throb … The distinctive noise rolled down our chimneys. Listening, you felt as an animal feels, hiding when hunters are near.

One night at midnight, Bill roused me from my bed and we walked up the village to climb Belmont Hill, from whence there was a good view of the surrounding country.

A glow lit the whole sky to the south.

‘Exeter’s getting it,’ Bill said.

Later, we drove to Exeter to witness the extent of the damage. Most of the city had gone. Rubble had been cleared away by then. Nothing remained. Nothing, except the cathedral, which stood alone on an unearthly flat plain. Here and there, as we drove, we passed an occasional lamp standard which remained upright. No living person was to be seen; those unburied had decamped to adjoining villages. The Germans had wiped the city off the map. In this surreal landscape, Air Marshal Hermann Goering had done Salvador Dali’s work.

The English, so tolerant, so enduring, so brave, during World War II, became a lesser race after the war. Exeter was rebuilt as an anonymous town, without that sense of style its old black-and-white buildings had conveyed. Little memory was retained of what it had once been. The Germans, Poles, French rebuilt their cities according to old plans and photographs, effecting smart restorations and canny improvements. British town planners held no such reverence for what had been, as they plugged the standard chain stores into the city centres. The English made no great protest at what was happening.

The blackout lent an enchantment to banal village streets. On more than one occasion, we climbed Belmont Hill to watch the Luftwaffe at their work of destruction.

Far distant, as if an angry planet were about to rise, a fan-shaped light would grow on the horizon. We stood silent on the hill to witness the raid on Plymouth. Even the burning of distant Swansea was visible. Hundreds of civilians died, and with them fabrics and traditions of an earlier age.

After witnessing the air raids we would walk back down the hill, and huddle in the little kitchen behind the shop while Dot made us cups of tea. By the time we were in bed, we would hear the Dorniers returning to Germany. Throb-throb-throb, down the chimney again.

On Belmont Hill stood a small public school, run by a regimental sergeant-major posing as headmaster. The dramatist John Osborne, four years my junior, was incarcerated there as a boy. He used frequently to come down to our shop to buy a packet of Player’s ‘Weights’, whereupon he became friendly with Dot. Growing sick of the sergeant-major, Osborne dotted him a punch in the eye, for which he was expelled.

One great advantage of the blackout was the darkness everywhere, allowing the stars and Milky Way to shine clearly. With my little Stars at a Glance in hand, I used to stand on top of our air-raid shelter and watch the constellations. How peaceful were those regions of fire – so different from Exeter burning. Surely in the marvellous beauty of the night sky lay some hope for humanity, war or no war.

Since then, I have stood in the Dandenong Hills in Australia and looked up at a different sky. All the familiar populations of the northern hemisphere have gone. It is as if one stood on a different planet. Even the night sky seen from Mars would appear less alien: the Plough, Cassiopeia, and other constellations would look much the same from Olympus Mons as seen from our air-raid shelter. The distance between Earth and Mars is so short, if insuperable as yet.

At West Buckland, things settled down. The headmaster, Sammy Howells, was a master of sarcasm. He wore pince-nez and had a ginger moustache. The lapels of his suit were permanently discoloured by a W. D. & H. O. Wills’ product, Gold Flake cigarettes. Ciggies must have served him as dummy and mistress, and fumigated the perpetual pong of small boys from his nostrils.

To give the devil his due, he ran a tight ship in stormy times. Sammy was a brilliant teacher of English and in particular of English grammar. With his withering tongue, practised at dissecting the language, he could take any unfortunate boy apart. I relished those lessons, much as I feared Sammy. He took a particular dislike to me, calling me ‘The Comedian’. Sammy liked to be the one making the jokes.

It was noticeable that when he picked on one boy in the class, everyone else laughed fawningly, protecting themselves from the line of fire. They also professed to like him, for the same reason. I really hated Sammy. The old bastard died just before my first book was published. The smokes got him in the end. His lungs went. Poor Sammy Howells – a good headmaster, a brilliant teacher, a dedicated man, a shit.

One thing stands for ever to Sammy Howells’ credit. Whenever Winston Churchill was due to address the nation, Sammy had us all assemble in the Memorial Hall to listen to his speech. Listen we did to that great master of oratory, during those testing years the inspiration of our country.

Obtaining masters to teach was a wartime problem. Most of them had been called up into the Forces. Sammy engaged two conscientious objectors. One was a mathematics teacher, a Mr Coupland, immediately nicknamed, with cruel perception, Chicken Coupland. Coupland knew much maths but could not convey it. Despite furious beatings, liberally dispersed, he could not make us learn. I regret it; I never entered the world of maths, on which most sciences depend.

Mr Foster was a strange man, a refugee from somewhere. We tended to make fun of him. He was known as Mitabout Foreskin, a Bowler christening. Then he took us for a German lesson, and sang ‘Roselein’ to us in a beautiful tenor voice. From then on we were much more respectful.

‘Crasher’ Fay taught us German and English in the upper forms. Most lessons were enjoyable. It was the boredom after class, the lack of privacy, the noise that got to you. All well exemplified in Lindsay Anderson’s film of public school life, If …

The truth was that the hardships of wartime Buckland, together with the rigours of the climate – over eighty inches of rain a year, compared with East Dereham’s twenty-eight – formed a common bond between masters and staff. Once a term, a barber and his assistant would drive out from Barnstaple on rationed petrol and cut the hair of every boy in the school, working steadily all day, class by class. We went in to the torture chamber maned like lions, to emerge as criminals, scarred here and there by the hasty razor. Of course we laughed, unaware that similar shavings were taking place in Auschwitz and Buchenwald.

Some masters, some boys could not stand the rugged conditions. A brief visitant among the masters was an eccentric S. P. B. Mais, then quite a famous name, a popular broadcaster and writer. I knew his name from the pages of Modern Boy, for which he wrote spy stories. He walked about the school complaining, swaddled in sweaters, swathed in scarves. He taught maths in English lessons, algebra in geography, and anything in anything else. I was to meet him later in life. He left Buckland after one or two terms to write a grouchy little book about the place – a book banned by Sammy but adored by Sammy’s prisoners.

Certainly the place was remarkably cold and wet. Spartan was its ethos. After lights out in our house dormitory, the blacked-out windows had to be opened, the ones to the north, the ones to the south. Mid-ocean gales blew through the rafters, wafting Atlantic chill with them. Plumbing was rudimentary. Each of us had an enamel bowl, filled overnight with cold water. Many a winter’s morning we broke the ice before we could wash. I’m convinced this hardship was good for us, at least for those who survived.

Then came summer. We did not at that time appreciate the beauty of North Devon. But there were long evenings spent out on the playing fields, rehearsing cricket strokes, feeling both the sound and the motion of bat striking ball; or simply playing catch with friends, the leather pill flying high in the air as the shadows of the trees along the drive lengthened. We could also swim in the school pool, but the rule of nudity was never to my taste, concerned as I was with privacy and secrecy.

Once my parents had enlisted me in Buckland, they never visited the school again, although it was only eleven miles from the shop. At the end of term I might cadge a lift in a van to Barnstaple or else walk with others three miles down the valley to Filleigh station, there to catch a Barnstaple train. (Filleigh station has long since been closed.) From Barnstaple, one caught a bus up Sticklepath Hill to Bickington, where it stopped almost opposite our shop.

On one occasion, I returned from school, went upstairs, flung myself on an ottoman, and lay there reading in peace. The relief after the racket of school was considerable. Dot came upstairs from the shop, annoyed because I was so unsociable. I used to stay awake at nights, reading into the small hours.

Having exhausted all the astronomy books in the school library, I turned more eagerly to science fiction magazines, which in those days regarded astronomy as the queen of the sciences. In the fifties they were to become propagandists for space travel. Curious to think that today much SF finds its place less among the stars than inside computers, in games and thought-sequences that recycle old ideas in new form. Not, in fact, outward but inward.

SF magazines introduced me to the name of Friedrich Nietzsche. I went to the Barnstaple Atheneum and applied for membership. The old men were curious to find a fifteen-year-old in their midst. Sitting in a large leather chair, I read Thus Spake Zarathustra. There I came across that conception of the Übermensch which was enjoying such popularity across the Channel in Berlin.

Nietzsche’s ideas filled me with indifference, even when I encountered them, diversified, diluted, in the writings of such SF authors as Ayn Rand and Robert A. Heinlein, whose books enjoyed wide popularity. I marked myself down as the eternal underdog. This canine trail led upwards later, from underdog to Steppenwolf.

As for the Übermensch, they were part of the fantasies with which I, like many others, scared myself. To relieve the tedium of the bus ride from Bickington to Barnstaple, I would play the British spy travelling on a German bus. The innocent conductor, working his way along the aisle to sell us tickets, was the Gestapo Überleutnant, checking papers and passports. He would find me out. I would be captured and shot, and my body flung into the Rhine.

This drama so took hold of me that on one occasion I jumped from a moving bus as it crossed the Taw bridge, to go sprawling in the road. The conductor watched grinning from the back of his bus, but luckily did not fire at me.

At the Atheneum I became acquainted with the writings of a local Barnstaple author, W. N. P. Barbellion, author of The Journal of a Disappointed Man. The misanthropic Journal was more to my taste than Zarathustra. Barbellion is splendid on himself and on the War – even if in his case it was the Great War. He writes, ‘They tell me that if the Germans won it would put back the clock of civilisation for a century. But what is a meagre hundred years? Consider the date of the first Egyptian dynasty! We are now only in AD 1915 – surely we could afford to chuck away a century or two? Why not evacuate the whole globe and give the ball to the Boche to play with – just as an experiment to see what they can make of it. After all there is no desperate hurry. Have we a train to catch?’

How could Barbellion foresee that within about twenty-five years after he wrote, the Boche were indeed intent on experimenting with the globe – and making a hell of it (aided and abetted by their allies the Japanese)? Did I but know it in AD 1942, they had already put the clock back by many centuries.

As for Barbellion on himself – to read him was to see myself in his sickly mirror.

‘I am so steeped in myself – in my moods, vapours, idiosyncrasies, so self-sodden, that I am unable to stand clear of the data, to marshall and classify the multitude of facts and thence draw the deduction what manner of man I am. I should like to know – if only as a matter of curiosity. So what in God’s name am I? A fool, of course, to start with – but the rest of the diagnosis?

‘One feature is my incredible levity about serious matters. Nothing matters, provided the tongue is not furred.’

The adventures of Barbellion’s psyche led me to that epicentre of adolescent turbulence, The Journals of Marie Bashkirtseff. I came across the book in two tall volumes, translated by Mathilde Blind – a name in its way as exciting as Bashkirtseff. This Ukrainian-Russian girl died aged twenty-five, thus becoming even more romantic than Barbellion, who ran to thirty-one years. The tempestuous Marie loved herself, hated herself. Misery excited her: it was something to pour into her many diaries. And she discovered as others have done that she was really two people.

‘At present I am vexed, as if for another person.

‘Indeed, the woman who is writing, and her whom I describe, are really two persons. What are all her troubles to me? I tabulate, analyse, and copy the daily life of my person; but to me, to myself, all that is very indifferent. It is my pride, my self-love, my interests, my envelope, my eyes, which suffer, or weep, or rejoice; but I, myself, am there only to watch, to write, to relate, and to reason calmly about these great miseries, just as Gulliver must have looked at the Liliputians …’ (Paris, May 30th 1877.)

Copying out these sentences now, I recall that for a brief period I lusted for this amazing emotional girl, long dead. I heard her satin skirts sweeping the Second Empire carpets, her voice at the piano, I empathised with her intense longings, feeling we would be a perfect match for one another, a consummation and a disaster waiting to happen.

Of course I was ashamed of these feelings. In this callow, shallow period, I was ashamed of all feeling. Much like the divine Marie, I could not tell how distraught I was. When I did have a real girlfriend, I dared not by a flicker of the eye reveal as much to my parents, or even to Betty, who might have told Dot.

Impossible to admit that I had a sex life. They would have murdered me. Or, worse still, laughed at me.

In some ways, it became more comfortable to be at school – though there was always the dread of leaving home, of feeling that I was being kicked out. I never shed tears – except when I said goodbye privately to Tiny, who was growing old.

Ours became an excellent form as we moved steadily up the school. We laughed a lot. I endeavoured to read every book in the moderately well-equipped library. This was when I started on Freud and Gibbon and Eddington and anything to do with astronomy or the workings of the human mind. My mind was already giving me trouble. The novelists we much admired were Evelyn Waugh, Aldous Huxley, Eric Linklater and J. B. Priestley. Graham Greene came along a little later.

Buckland was and is a sporting school. We played Chivenor, the nearby RAF station, at rugger, as well as various other public schools such as Blundells, outside Tiverton. All that strenuous exercise prepared us not only for the Army, but for life, to endure its hard knocks.

At the beginning of the autumn term, lorries arrived to collect the senior part of the school and drive us out to new agricultural developments on Exmoor, where heath had been turned into farm land. Acres and acres of potatoes were being grown. We worked from early in the morning until late, digging up long rows, turning up nests of those smooth vegetable eggs, while the sun sloped low towards the Atlantic.

It was backbreaking work. Our reward was to be driven home to school for mass baths, all grubby naked bodies steaming together, followed by a meal in hall of sausage with piles of mashed potatoes, our potatoes.

We also held drives for the Forces. At one time, a group of us, wearing clean rugger togs, pushed the school barrow around Swimbridge, collecting waste paper. We knocked on people’s doors. Sometimes they invited us in and plied us with cups of tea. Generously they gave, throwing out valuable books, sets of Edwards’ Birds, first editions of Anthony Trollope’s novels. But, ‘Us’ll keep us bound volumes of Punch, because them’s real valuable’.

What was really worthwhile went out with the rubbish. The mediocre was saved.

As in an inverted morality play.

3 (#ulink_8c43a985-6e1b-5cc6-9d2b-5166923c5086)

The School (#ulink_8c43a985-6e1b-5cc6-9d2b-5166923c5086)

Suddenly, after a long silence, he began to talk … ‘A man goes to knowledge as he goes to war, wide-awake, with fear, with respect, and with absolute assurance. Going to knowledge or going to war in any other manner is a mistake, and whoever makes it will live to regret his steps.’

Carlos Castaneda

The Teachings of Don Juan: A Yaqui Way of Knowledge

We held a ‘Wings for Victory’ fair on WBS rugger field, the Huxtable. It was a great event. Our vendettas against local farmers were set aside so that we could borrow their carts. I turned what had been shameful into satire against myself and became Adolf for a day.

Some years previously, one of the innumerable Framlingham bullies, a creature with the skin of a bullfrog and hyperthyroid eyes to match, grabbed me and declared that I resembled Adolf Hitler. Dragging me into his foul den, he pulled a lock of my hair down over my forehead and painted a moustache of black boot polish on my upper lip. I was then made to goose-step round a senior common room, giving the Sieg Heil for the delectation of all the other bullies – many of whom would doubtless have given their eyeteeth to dress up in Nazi uniforms, rape Slav women, and bugger each other while strangling Jews.

By Buckland’s ‘Wings for Victory’ day, I had sufficiently recovered from this degradation to put the act to good use. Suitably uniformed, I mounted one of the farm carts and addressed all and sundry in gibber-German, looking remarkably like Adolf. Or so my friends and admirers told me later.

Hitler still exerts an awful attraction. He has proved to be many things to many men. Hugh Trevor-Roper captured something of the truth when he described Hitler’s mind as ‘a terrible phenomenon, imposing indeed in its granitic harshness and yet infinitely squalid in its miscellaneous cumber – like some huge barbarian monolith, the expression of giant strength and savage genius, surrounded by a festering heap of refuse – old tins and dead vermin, ashes and eggshells and ordure – the intellectual detritus of centuries.’

Well, that does sound fascinating …

It is terrible to think one should still hold Hitler in mind. And I once imitated him! Even the young and innocent are fascinated by wickedness. I suppose it helped prepare us at WBS to be soldiers.

To Crasher Fay I owe more than mere learning. For English classes, we had to produce an essay every Monday. I was excused. Crasher permitted me to present a story instead. A gratifying privilege as we trudged towards the School Certificate …

By this time, the writing of short stories had become a continuous occupation. Our form enjoyed, shared, quoted, laughed aloud at Sellar & Yeatman’s 1066 and All That, as well as their less famous books, such as Horse Nonsense and Garden Rubbish. I wrote ‘Invalids and Illnesses’. It was sanitary enough to take home, where my mother read it. I overheard her saying to someone, after reading out a funny bit about diphtheria, ‘You may not like it, but it is clever.’ Eavesdroppers seldom hear good about themselves; I felt she had summed me up.