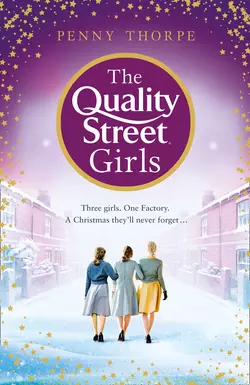

The Quality Street Girls

Penny Thorpe

Inspired by the true story of the Quality Street factory and its loyal workers, this is a nostalgic and compelling novel and the perfect Christmas treat.At sixteen years old, Irene ‘Reenie’ Calder is leaving school with little in the way of qualifications. She is delighted to land a seasonal job at Mackintosh’s Quality Street factory. Reenie feels like a kid let loose in a sweet shop, but trouble seems to follow her around and it isn’t long before she falls foul of the strict rules.Diana Moore runs the Toffee Penny line and has worked hard to secure her position. Beautiful and smart, the other girls in the factory are in awe of her, but Diana has a dark secret which if exposed, could cost her not only her job at the factory but her reputation as well.When a terrible accident puts supply of Quality Street at risk, Reenie has a chance to prove herself. The shops are full of Quality Street lovers who have saved up all year for their must-have Christmas treat. Reenie and Diana know that everything rests on them, if they are to give everyone a Christmas to remember…

Copyright (#ua99d1feb-5903-5249-a8ee-8159066b0299)

Published by HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

Copyright © Penny Thorpe 2018

First published in Great Britain by HarperCollinsPublishers 2018

The ‘Quality Street’ name and image is reproduced with the kind permission of Société des Produits Nestlé S.A.

Jacket design by Claire Ward © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2018

Jacket photographs @ Ildiko Neer / Arcangel Images (figures)

© Robert Lambert / Arcangel Images (terraced houses)

Shutterstock.com (http://www.Shutterstock.com) (window frame)

Penny Thorpe asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008307769

Ebook Edition © November 2018 ISBN: 9780008307776

Version: 2018-10-30

Dedication (#ua99d1feb-5903-5249-a8ee-8159066b0299)

In loving memory of Mary Lowes Walker, who made even more friends than Reenie.

Table of Contents

Cover (#uc901845d-5bc6-5738-93d5-e34121a08678)

Title Page (#u765dbb12-c736-528e-85eb-c36a64e2cd46)

Copyright (#u1ff7919d-8fdd-54a1-8a81-34e68879e2b1)

Dedication (#u63157930-36de-53fc-be24-8c28727f8067)

Chapter One (#u8785a685-4dbb-5451-a107-9b938d62aef4)

Chapter Two (#ua1ec0cf0-56bc-5927-b584-efeca1708b0c)

Chapter Three (#u6e4ab527-f1a2-557f-ad8b-71f5d4771d3b)

Chapter Four (#u9559a2c8-3415-5ec8-87b0-1dff9fa19b9d)

Chapter Five (#u6bd0b18b-4371-525e-836e-3f23eeed4f0f)

Chapter Six (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Seven (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Eight (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Nine (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Ten (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Eleven (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twelve (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Fourteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Fifteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Sixteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Seventeen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Eighteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Nineteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-One (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Two (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Three (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Four (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Five (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Six (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Seven (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Eight (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Nine (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirty (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirty-One (#litres_trial_promo)

Acknowledgements (#litres_trial_promo)

Toffee Town: The sweet heart of Halifax (#litres_trial_promo)

Q&A with Penny Thorpe (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter One (#ua99d1feb-5903-5249-a8ee-8159066b0299)

It was late, and the Baxter’s store on the corner at Stump Cross was closed, but the lights in the main window illuminated a sparkling display of Mackintosh’s Quality Street; the latest success from the sprawling factory they called Toffee Town. As Reenie rode her nag closer she could see that someone had taken the coloured cellophane wrappers from the chocolates and taped them between black sugar paper to make little stained glass windows. Between the tins and tubs and cartons were homemade tree baubles; an ingenious mixture of ping-pong balls, cellophane wrappers, glue and thread.

While there were plenty of other confectionery assortments that Baxter’s could have chosen to feature, Reenie couldn’t imagine they’d have had much luck making a stained glass window out of O’Neil’s wrappers. Besides, Quality Street was the best, everyone knew it; plenty of girls from Reenie’s school had left to work in Sharpe’s or O’Neil’s factories, but it was the really lucky ones that went to work at Mackintosh’s.

Reenie’s enormous, ungainly old horse shuffled closer to try to nose the glass, the explosion of colour bursting forth from the opened tins on display had caught his eye and was drawing his curious nature to the window. Reenie didn’t blame him; it was a beautiful sight and he deserved a treat when he was being so good about coming out after putting in a day’s work in the top field. She had a great deal of affection for the old family horse, and she liked spoiling him when she got the chance, so she let him dawdle a while longer.

Reenie gazed at the window display, and dreamed of growing up to be the kind of fine lady that bought Quality Street, and had a gardener, and got driven around in an automobile. For the moment she would have to be content with being a farmer’s daughter who had a vegetable patch and occasional use of her family’s peculiarly ugly horse. Fortunately for Reenie, she found it easy to be content with her lot, she was an easily contented girl. As long as she didn’t have to go into service she was happy.

‘Come on, Ruffian. We’ve got a way to go yet.’ Ruffian reluctantly allowed Reenie to steer him away from the bright lights, and continued up through the ever steeper streets of Halifax, over quiet cobbles she knew well. The night was cold for October, but she knew she had to ride out to get her father nonetheless.

Reenie didn’t mind; Ruffian was technically her father’s horse, and most fathers would not allow their daughter freedom of the valley with it, so she supposed she ought to feel pretty grateful. And it wasn’t as though she had to come out to get her father very often, she thought to herself. He only got this blotto once a year when the Ale Taster’s Society hired out the old oak room and had their ‘do’, apart from that she thought he was pretty good really. He was very probably the best dad.

Reenie’s thoughts kept drifting back to the sandwich that was waiting in her pocket, wrapped in waxed paper and bound up with a piece of twine. The sandwich contained a slice of tinned tongue and some mustard-pickled-cauliflower that her mother made for Reenie to give to her father to eat on his way back. Reenie’s stomach rumbled and she was tempted to take a bite out of it before she got to the pub, even though she’d had her tea. Her mother frequently told her that she was lucky to live on a farm where there was no shortage of food, but Reenie pointed out that there was no shortage of the same food: mutton, ewe’s milk cheese, ewe’s milk butter, ewe’s milk curd tart, and ewe’s milk. She rode in the dark past the Borough Market, there was a clamour outside The Old Cock and Oak. As she approached, Reenie didn’t like the look of what she saw. Ahead of her, she could see brass buttons glinting in the old-fashioned gaslight from the pub, and the tell-tale contours of Salvation Army hats and cloaks. It was going to be another one of those nights.

Reenie knew before she’d even rounded the corner that this was not the regular Salvation Army, they would be off doing something useful somewhere involving soup and blankets. This was a Salvation Army splinter group, who the rest of the Salvation Army considered to be nothing but trouble. Reenie tried to feel friendly towards them as she wasn’t in a hurry, but she did wonder privately why they didn’t just go to the cinema when they got time off like everyone else.

‘Think of your wives! Think of your children!’ Reenie couldn’t tell where in the throng of ardent believers the call was coming from, but she knew that they wouldn’t be popular with the pub regulars. There were several other pubs along Market Street, but the faithful had chosen to cram into the courtyard of The Old Cock and Oak to protest against the annual meeting of the Worshipful Company of Ale Tasters. Reenie couldn’t see what they were so fussed about, but this wasn’t anything new.

Reenie decided not to dismount this time and walked old Ruffian as close to the pub door as she could, keeping a loose, but expert grasp on the fraying rope that served as Ruffian’s bridle. ‘Comin’ through, ‘scuse me, if you’d let me pass, please.’ As the ramshackle old horse nosed its way through the faithful, the crowd parted, some out of courtesy but others to avoid being stamped on by a mud-caked hoof, or bitten by an almost toothless mouth. Ruffian may not have had the aristocratic pedigree, but like his rider, he encouraged good etiquette in his own way. Reenie was close enough now to see a few faces she knew guarding the doorway; exasperated men waiting for the do-gooders to move on, their arms folded. ‘Is me dad in there still?’

‘Now then, Queenie Reenie, what’s this you comin’ in on a noble steed with your uniformed retinue.’ Fred Rastrick gave her a wicked grin as they both ignored the small, rogue faction of the otherwise helpful Halifax branch of the Salvation Army.

‘Don’t be daft, Fred, you know full well they’re nowt to do wi’ me. Now fetch us me dad, would ya’? It’s too cold for him to walk home, he’ll end up dead in a ditch. Go tell him I’m here and I’m not stopping out half the night so he has to be quick.’

‘Young lady! Young lady, how old are you?’ Reenie recognised the castigating voice of Gwendoline Vance, self-appointed leader of this band of Salvation Army members who’d taken it upon themselves to object to most things that went on in Halifax, including the Ale Tasters annual ‘do’. Reenie could have mistaken the woman’s face in the dark, even this close up, but there was no mistaking the way she was harping on.

‘What’s it to you?’ Reenie was not in a mood to be cross-examined by strangers, especially those in thrall to teetotalism.

‘Shouldn’t you be at school?’

‘Well, not just now as it’s half past ten at night.’

‘Well I meant in the morning, shouldn’t you be at home in bed by now so that you can go to school in the morning?’

‘No, and I’ll tell you for why. Firstly, I’m fifteen and I finished school at Easter; secondly, some of us would rather be spending our time helping our families than wasting it on enterprises that won’t get anyone anywhere; and thirdly (and forgive me if I think this is the most important), because today is a Friday, and when I were at school they taught me that the day that comes after Friday is Saturday, and that, madam, is when the school is closed. Now if you’ve quite finished, I want me’ dad. Fred!’ Reenie had to call out because Fred had disappeared further inside the pub. The Salvation Army devotee blanched and choked on her words. Reenie ignored her and turned her eyes to the doorway of The Old Cock and Oak.

‘He’s here, Reenie,’ Fred reappeared, ‘but he can’t walk.’

‘Well then tell him he doesn’t have to. I’m waiting with the ’orse.’

‘No, I mean he can’t walk. He’s blotto; out cold.’

‘Oh, good grief. Well, can someone drag him to the door, I don’t want to have to get off the horse or I’ll be here ‘til Monday.’

‘I’ll have a go.’ Fred turned to go back inside. ‘But he’s not as light as he used to be.’

‘Reenee,’ the do-gooder emphasised the Halifax pronunciation, ree-knee, and tried to assume an expression that was both patronising and penitent for her earlier mistake, ‘may I call you Reenie?’

‘No, you may not. Unless you’re gonna help with m’ dad.’

‘We’d be very, very glad to help with your father; it must be terribly hard on you and your family. Do you think you could bring him with you on Sunday to—’

‘No, I meant help lift him on the ’orse. Good grief, woman, are you daft? Fred! How’s he looking?’

‘Nearly there,’ Fred called out through gritted teeth as he attempted to pull the dead weight of Mr Calder out to his horse and daughter, then turned to a fellow drinker ‘Bert, can you give me an ‘and throwin’ him over Ruffian?’

Bert held up a hand and said, before darting back into the pub, ‘You wait right there; I think I know just the lad for this.’ Bert brought out a bemused-looking young man who Reenie didn’t recognise, slapping him on the shoulder with friendly camaraderie and pushing him in the direction of the horse. He didn’t have the slicked hair with razored back and sides that the other lads round here had. His hair wasn’t darkened by Brylcreem; instead, he had fine, golden toffee coloured hair that fell over his left eye and gave him away as a toff. Straight teeth, straight hair, straight nose, and a smarter suit of clothes than anyone else there; to Reenie, he looked hopelessly out of place among the factory workers and farm hands. It made her like him instantly for joining in with people who weren’t like him. She might not have a lot in common with this posh-looking lad, but there was one thing; he looked like the type who would make friends with anyone.

‘Reenie, Peter; Peter, Reenie.’ Bert skimmed over the necessary introductions. ‘We need to get Reenie’s dad here over the ’orse.’

Peter smiled and nodded, and with what seemed like almost no effort at all, he gathered Reenie’s father up and launched him in front of where Reenie sat, with his arms and legs dangling over the horse’s withers on either side. The landing must have been a rough one for Mr Calder because, though unconscious, he still managed to vomit onto the military-style black boots of the nearest Moral League man.

The sudden eruption caused a shriek from the group’s ringleader who turned to Reenie, ‘Oh you poor child. You shouldn’t have to see such things at your tender age.’

‘Oh gerr’over yourself, woman. Everyone’s dad drinks.’ Reenie bent over to check on her father because although she was confident that he’d be alright, she thought it was as well to make sure. Her shoulder-length red hair dangled down the horse’s side as she dropped her head level with her father’s, reassured by his loud snore; silly old thing, what was he like? Her mother would laugh at him come the morning. Reenie looked up to thank the young man, but to her disappointment, he’d already gone. She had wanted to tell him that her father wasn’t usually like this, and not to mind the Sally Army crowd because they weren’t bad as all that if you weren’t in a hurry to get anywhere. She had wanted to say so many things to him, but she supposed it was better she get a move on and take her father home to his bed. It didn’t occur to her that the young man had gone indoors to fetch his coat and hat so he could offer to walk her home like a gentleman.

Reenie pulled on Ruffian’s make-shift bridle and began to lead the horse away, then thought better of it and stopped to call over her shoulder ‘and my friend Betsy Newman’s in the Salvation Army and she says you six are pariahs! Go and help ‘em with the cleaning rota like they’ve told ya’, and stop botherin’ folks who’ve had an ‘arder week at work than you’ve ever known!’

Ruffian snorted, as if in agreement, and guided his mistress home.

Diana waited for Mary on the street outside; her father’s thick old coat wrapped tightly around her, and the wide collar turned up against the autumnal night. ‘She’s definitely not with him this time,’ Mary said, leaning one hand on the door frame of her mother’s soot-blackened one-up-one-down terrace as she hurriedly pulled on a well-worn shoe with the other hand ‘she’s promised she won’t see him anymore.’

Diana didn’t respond; it was a waste of effort, and she was bone tired. She had spent all day at work in the factory, then had come home to find her stepbrother hadn’t paid the rent and had taken off with Mary’s sister Bess. Not that this came as a surprise; nothing came as a surprise to Diana any more. Mary’s sister was in thrall to her no good stepbrother, as only a silly sixteen-year-old can be. Diana had been a silly sixteen-year-old herself once, although it felt like a lifetime ago and not the mere ten years that separated her from that other person she had once been. Diana had been in thrall to someone equally unsuitable, and she knew that there was nothing to be done for Bess now.

‘She realises now that he’s no good for her.’ Mary was following behind Diana and kicking at her shoe to move back the loose insole that had shifted when she’d pulled on her winter shoes over bare feet. ‘I don’t know where she’s gone tonight, but I’m certain she’s not with him.’

Diana didn’t ask why Mary was following her if she believed all of her sister’s promises; she didn’t need to. Diana was the oldest girl on their production line, and younger ones like Mary fell into line with whatever she said.

‘I mean,’ Mary went on as they turned the corner of Mary’s street and past the midnight blue billboard that announced that Rowntree’s Cocoa would nourish them all, ‘how do you know that it was definitely them?’

Diana stopped suddenly. She disliked walking while talking; she disliked talking at all, and she thought that if she didn’t stop to say what she had to say then Mary would carry on kicking at her shoe rather than ask her to wait while she fixed it. Stopping killed two birds with one stone. ‘I saw someone who told me that your sister and my stepbrother were in The Old Cock and Oak in town and that if I didn’t hurry he’d have all my rent money spent.’

‘But could they have been mistaken? I mean, what were their exact words?’ Mary hopped on one foot as she tried to arrange her shoe without letting her bare foot touch the ice-cold cobbles of the dirty street.

Diana sighed ‘He said “You want to get down to The Old Cock and Oak, Diana, before that no-good stepbrother of yours spends all your money. ‘The Blade’ as he likes to call himself is in there with the Good Queen, and he’s buying everyone a drink.” There’s no mistake; your sister is there with him.’

‘What does he mean ‘Good Queen’? Who’s ‘Good Queen’ when she’s at home?’ Mary looked genuinely confused.

There was a long silence as Diana tried to decide whether or not to tell Mary what people called her; it might help her to do something about it, but then again it might not. Behind their backs Mary and Bess were known as the Tudor Queens; the porters on their production line had started calling Mary ‘Bad Queen Mary’ because she had a short fuse and no one had ever been able to get her to crack a smile. Her younger sister Bess was her polar opposite; she was cheerful to a fault. She had no concept of the consequences of her actions as she floated along in a happy bubble, and Diana had been forced to speak to her about it on the production line on a number of occasions, to no avail. Bess was all smiles and affection, and they called her ‘Good Queen Bess’.

It seemed odd to Diana that two people could look so different while looking so alike. They had the same large, upturned eyes, but where Bess’s looked pretty, Mary’s glasses made hers appear bug-like. They had the same porcelain-white skin, but where Bess’s looked delicate, Mary’s looked ghostly. They both had a strawberry mark on their left cheek, but where Bess’s looked like a cherubic kiss, Mary’s looked like she was crying tears of blood. They were their own worst enemies, Diana had told them so often enough; Mary had a short fuse because she tied herself up in knots with worry, while Bess was as useless as a chocolate teapot in the factory because she was too happy-go-lucky. Diana wondered if Bess would ever realise her job was to make toffees, not gaze dreamily into the middle distance. Diana could see why they’d ended up the way they had; Mary had to do the worrying for both of them, and Bess didn’t need to worry with a sister like Mary. If they could trade places for a day, it might do them the power of good.

‘Have you fixed that shoe yet?’ Diana didn’t want to wait in the road much longer, her stepbrother liked to flash money around when he had it, and he’d be on to another pub before closing time if she didn’t catch up with him first.

‘It keeps moving around.’ Mary huffed with annoyance and crouched down to unlace her shoe and fix it properly, fumbling as though she were worried that she was taking up too much of Diana’s valuable time.

Mary looked pitiful under the streetlamp. Her frizzy black hair was pulled tight back and twisted into a bun at the nape of her neck. All the other girls at the factory had their hair curled like the girls in the magazines, but not Mary; there were dark circles around her eyes and in the winter of 1936, Mary didn’t even have a warm coat. Poor kid, Diana thought to herself, she needs someone to look after her for a change.

‘Alright, I’m ready.’ Mary stood up and shook her foot in her shoe one last time. ‘I still don’t think it’s him.’

‘My stepbrother could hardly be mistaken for anyone else. Apart from the fact that he’s the only person in Halifax to dress like some American mobster from the pictures, he also looks like a cross between a rat and a frog, so his face is hardly going to blend into a crowd, is it?’ Diana started walking again. The trouble with Mary Norcliffe, she thought to herself, was that she couldn’t just walk in silence.

Mary followed Diana with her arms folded around herself and her shoulders hunched forward; her eyes were on the tram rails that stretched out down the road ahead of them, but then she looked up to Diana and said, ‘Thank you for calling on me though.’ There was an anxious pause as though Mary feared that every sentence was saying too much or too little. ‘I know she’s a nuisance, but she has promised she’ll change. Honestly she has.’

Diana knew that Good Queen Bess would never be capable of seeing the consequences of her actions, and her sister Mary would always be looking after her. It was none of Diana’s business, and so she said nothing. She helped them in her own way, but she wasn’t going to try to change them. ‘There’s something I want to talk to you about.’ Diana looked up see that Mary was already panicking. ‘I’ve arranged for you and your sister to work beside me on the new line. We move floors tomorrow.’

‘But, if we—’

Diana didn’t let her finish, ‘Everyone knows that you’ve been helping your sister to get her work done, but we can’t let the other girls cover up for you anymore. You’ll have to move up beside me where I’ll be the only person covering for you, and then if you’re caught helping Bess, the only people that will be in any trouble will be the three of us. No more risking the other girls’ positions, do you understand?’

Mary swallowed and nodded.

‘I know you’ll still have to help your sister for a while yet, but you do it in my section and no one else’s. If Mrs Roth catches you, it’s best I deal with her.’

Diana was eventually rewarded with her longed-for silence, but she couldn’t enjoy it because she knew that Mary was wrestling with all kinds of questions that she wanted to ask, but didn’t dare voice.

They turned the corner onto Market Street where the rainbow of shops had closed their shutters for the night, like spring blooms closing their petals each evening. The street was by no means sleeping, it was alive with factory workers who were out for a payday drink. It was hard to imagine what Diana had heard this morning about the men in Barnsley on their way down to Westminster on a hunger march. The people of Halifax had seen lean times, but on this Friday there was merriment.

As they passed The Boar, the girls were met with catcalls from the drinkers who had spilled out into the street outside the various pubs that filled the centre of town. Diana supposed the catcalls were not unfriendly, but they irked her none the less. There had been a time when Diana had painted the town red; when she’d been bright-eyed and infamous in Halifax. Back then she’d been the queen of all she surveyed; and then six years ago all that had changed. Her carefree day in the sun had ended, and she would never go back to being that Diana.

‘Ignore them.’ Diana was saying it as much to herself as Mary, and they walked on. Six years was a long time, but no one could forget Diana. She might be wrapped up in her late father’s old black coat, her shoes might be down at heel, but she still looked like she’d stepped down from a Hollywood movie poster.

‘Look at the state of that!’ A buck-toothed drinker in the doorway of The Boar called out. Diana cast a glance in his direction and realised that he was pointing at Mary, who was taking the abuse quietly, as though she thought she deserved it.

‘What did you say?’ Diana mouthed the words at him almost inaudibly, barely a whisper. She didn’t need to raise her voice; when she spoke the scattering of flat-capped drinkers who had spilled out of the pub fell silent. The old light was back in her eyes, and her iron-ringed irises were locked on the insolent young man.

He laughed awkwardly, looking around to his friends for them to join in. It was near closing time, and the lamp-lit street was busier with friends and acquaintances than it had been an hour ago. The young man had assumed that they would all make fun of the plain-faced girl that followed the beautiful one, but he was mistaken. His friends quietly shuffled backwards; some could sense what was coming, and others knew from experience that to cross Diana Moore was a mistake you only made once.

‘What,’ Diana remarked as she stalked toward the young man like a predator slowly closing in on its prey ‘did you say?’

‘Well …’ he laughed nervously, throwing his arm up to indicate Mary but with less conviction now. ‘Have you seen the state of her?’

‘What about her?’ Diana was close to him now, and without so much as a wrinkle of her celestial nose, she conveyed a menace more potent than this young man was ever likely to encounter again.

He faltered and then said, ‘Well … she doesn’t have a coat, does she?’ He’d have said more; he’d have said that she was plain or ugly, or skinny, or that her skin was sallow and her hair unattractive, but he felt a cold fear at the beautiful and unmoving face that was so close to his.

Diana leant forward slowly; with the elegance and poise of a dancer, her lips were so close to his that for a heart-stopping moment he thought that she was going to kiss him. He lifted his chin a little in hope, but her mouth moved past his without touching it, and then her mouth was at his ear, her breath warming his skin with a tingle, and in a whisper that was all at the same time tender as a lover, and unforgiving as death she said, ‘Then give her yours.’

In the silence that had fallen over the drinkers, everyone heard her words.

Diana gently stepped back and the young man looked around helplessly at his friends, his mouth falling open in hesitation, confusion, and fear. He didn’t know how to respond, so he laughed nervously again and waited for his friends to join in. All he wished was for the moment to pass so they could all continue with their Friday night drinking in peace. But his friends didn’t come to his rescue; they didn’t do any of the things that he expected them to do, they looked at him in silence and nodded in the direction of the girl he’d been mocking; they nodded as though to tell him to hand over his coat.

When they arrived at The Old Cock and Oak Diana appeared to be in a slightly better mood as she had shocked Mary into another brief silence.

‘I can’t keep this.’ Mary was wearing the coat that Diana had thrown around her shoulders as she’d led her away from The Boar, and she looked worried; she always looked worried. ‘I can’t take his coat off him.’

‘So leave it at the pub tomorrow, and they can give it back to him.’ Diana pushed open the door of The Old Cock and Oak, holding it open for Mary to follow her into the tap room, ‘But I forbid you to give it back to him tonight. He doesn’t deserve it.’

The crowded saloon, and higgledy-piggledy layout of the pub made it difficult to see all the drinkers. A thick fug of tobacco smoke caught Mary square in the chest as they entered and she began coughing uncontrollably; Diana was used to it and immediately began looking for her stepbrother. She briefly looked around the corner into the Savile room, but realised that her stepbrother wouldn’t be there; that part of the pub was mostly occupied by older folks who still smoked their tobacco in clay pipes to save money on cigarette papers and Tommo wouldn’t deign to be seen with the likes of them.

Diana ducked her head under the minstrel gallery that spanned one side of the pub. It was a strange old place, like something from a fairy story. It was all carved oak mermaids and crazy staircases; Tommo tended to frequent billiard halls, or places where he could be a big fish in a small pond, this was not his sort of place at all, which meant that he was up to something. The pub was full, but the clientele were divided evenly into two groups: the first were the Worshipful Company of Ale Tasters who had come in for their annual ale tasting evening in the private room on the next floor up. The second group of drinkers were the relatively sober regulars who had stopped by for a small glass of bitter after a day at work and were trying to suppress their amusement at the ale tasters who were all stumbling down the 16th-century staircase in an attempt to make their various ways home. Diana overheard the barman telling another drinker that they’d had an incorrectly labelled ale submitted for their tasting that year and it was rather stronger than they had anticipated. She suspected there would be a lot of sore heads in the morning and was glad that she wasn’t one of them.

Over in the snug, she found Bess with a group of engineers that she recognised from the factory. Bess was under five feet tall, so when she saw her sister coming to get her she had no trouble darting behind one of the engineers to hide. Bess seemed to think it was all a game because she was giggling happily; the look of desperate exhaustion on her sister Mary’s face didn’t seem to register with her.

Diana approached the group, ‘Bess, your sister’s been worried sick.’

‘Don’t worry about her,’ Bess whispered conspiratorially, evidently still thinking that if she stayed out of the way her elder sister might not find her to make her go home. ‘Mary’s always angry about summut’, it won’t be ‘owt serious, let her go and cool off.’

It was too late, Mary had caught sight of her sister in their midst and had come round to forcefully grasp hold of her wrist and drag her out of the bar, calling out, ‘Landlady! My sister is under-age to drink, don’t serve her in future!’

Mrs Parish the landlady came out from behind the bar, ‘And when the bloody hell did you sneak in, young lady?’ She looked at Bess with a mixture of annoyance, amazement and confusion; Mrs Parish was a third generation licensee, and you had to get up very early in the morning to catch her out. If anyone got into her pub without her knowing it would have to be by some witchcraft.

Bess giggled, ‘I was hiding inside my friend’s coat when we all came in, and then I ran round into the snug. Didn’t you see us? We looked like a pantomime horse. Everyone laughed!’

The landlady’s shoulders sagged in exasperation. ‘I’ll remember your face, young lady. You’re barred.’ Mrs Parish narrowed her eyes at Mary. ‘And how old are you?’

Mary appeared to be mildly affronted by the question. ‘I only came in to get her. I’m going now. I wouldn’t come into a pub unless I had a good reason.’ Mary hustled her sister from the premises.

‘Oh, Mary,’ Bess’s contented, innocent expression hadn’t changed even though she was being hauled out of the pub, her bouncing, honey-blonde curls falling over her eyes prettily, ‘I was only coming out for a bit o’ fun with the engineers, there’s no harm in it. You should come out sometimes too; now you’re old enough.’

‘You’ll be fit for nothing at work tomorrow, and then where will we be?’

Diana followed the bickering sisters out into the courtyard, ‘Bess, have you seen my stepbrother? I need to know where he’s gone.’

‘Have you tried at home?’ Bess meant well, but it obviously didn’t occur to her that Diana would already have looked there; common sense was not Bess’s strong point.

‘He’s not at his mother’s house. Where did he say he would be? Where did you last see him this evening?’

‘I didn’t see him tonight. But maybe you could see him at the factory tomorrow? He wants to come and look round the factory in the morning.’ Bess said it as though she were imparting a nice piece of news that would please her sister and their colleague Diana.

‘What does he want to do that for?’ Diana was suspicious.

‘Well,’ Bess looked around and then leant forward conspiratorially, ‘I think he wants to get a job at the factory. I think he wants to get settled somewhere nice.’ She smiled; she genuinely believed the best of the young man who called himself Tommo ‘The Blade’ Cartwright.

‘Trust me, Bess, my brother is not trying to get a job in the factory. If he asks you to get him inside the gates you tell me about it straight away, you understand?’

‘Do you think we could get him an overlooker’s job on our line?’ Bess’s voice squeaked with cheerful optimism.

Mary and Diana sighed with exasperation. This was the last thing they needed.

Reenie rode home through the heather, and by the light of the moon. When there was moon enough she’d allow herself this luxury of travelling back over Shibden Mill fields instead of the road. There was good solid ground underfoot for Ruffian, and if the night was clear enough she could see out across the rooftops of half of Halifax (if she didn’t mind being unladylike and sitting backwards in her saddle and letting Ruffian take them both home).

Her father was no trouble as he slept, helpless as a babe, over the front of their horse. She realised, to her delight, that she could eat that tinned tongue sandwich in her pocket. Her father wouldn’t remember in the morning if she’d had it; she took the waxed paper package from her pocket, pulled away the twine and took a bite of the soft, fluffy bread. It was heavenly, and Ruffian plodded on while she tucked in. Reenie was just near enough to the lane that bordered her part of the field that she could make out the silhouette of a lone policeman on a bicycle, effortlessly freewheeling down the hill.

Reenie was in such good spirits that she decided to ride nearer to the fence and wish him a good evening.

With a mouth full of tinned tongue sandwich she called out, ‘Nah then! ‘Ow’s thi’ doin’?’

The officer pulled on his brakes and skidded the bicycle into a sideways halt just yards away from Ruffian. He didn’t speak immediately, but narrowed his eyes and assessed the teenaged girl who grinned at him naively in the moonlight; the almost-lifeless bundle of clothes that appeared to be a man; and the knock-kneed, run-down old horse that couldn’t have more than a year or two of life left in him. Finally, he asked, ‘Is this yours?’

‘What, the horse or the old man? The sandwich is mine, but you can have some if you’ve not had any tea.’

‘No, the land; is that your land?’ Sergeant Metcalfe became frustrated when he saw that the girl who was trespassing still didn’t understand. ‘You’re on private land, lass. Look at the signs and the fences. Can you not read the signs?’

‘Can you not go on it if you’re just using it to go home?’

‘No, you cannot trespass if you’re trespassing to go home. Trespassing’s a crime; you could be up before the magistrate.’

Reenie smiled amiably. ‘But I always go home this way.’

The policeman pinched the bridge of his nose and sighed, ‘Do you know what it means when someone says that you’re not doing yourself any favours?’

‘I don’t understand; am I in trouble? Is it because I haven’t got him on a saddle? Because he’s never had a saddle. We just use him for turning over the field and fetching dad and the like.’

The policeman sighed in frustration and thought about how late he’d have to stay at the station if he arrested a minor, and all the extra trouble of taking an unconscious man and an unsaddled horse into custody. Sergeant Metcalfe looked up into the happy, well-meaning face of Reenie Calder and decided that this was a battle he’d never win. ‘You know what,’ the policeman took a deep, exasperated breath, ‘No one died so just go home and don’t tell anyone I saw you or I’ll get it in the neck for not doing ‘owt about it. Don’t kick up the grass, don’t wander about, don’t let anyone else catch you, and don’t do it again.’

Reenie looked earnest, as though she was doing her best to help him, ‘Don’t do what again, exactly? Is it the horse, or is it me dad?’

Metcalfe threw up his hands. ‘Right, that’s it, I’m going home. You win. You will be the death of someone one day, but not me and not tonight. Get thi’ to bed and don’t let me see you here again.’ He knocked the kickstand back up off his bicycle ready to wend his way to the station to sign off duty for the night as quickly as he possibly could, but he stopped, thought, and asked: ‘You’re not Reenie Calder, are you?’

Reenie Calder looked him innocently in the eye. ‘No. Why?’

He held her gaze, debating once again whether or not to risk the ridicule of the station by taking in a girl, a drunk, and their horse into custody … No, it wasn’t worth the risk; and quietly, he went on his way.

‘Oh, well have a nice night, won’t you.’ Reenie shrugged to no one but herself. Reenie loved a bit of trespassing. She wasn’t sure if it was because she liked the thrill of naughtiness from this minor infringement of the land laws, or whether she liked the idea that she was taking a stand against all them rich folks that would seek to prevent a Yorkshireman from being taken home the quickest route in his own county. ‘Well Ruffian, it’s just me and thee. It’s a nice night for it. Now would you look at that sky?’

Reenie drank in the night air, the beauty of the stars, the joy of being on her way home with Ruffian, and the delight of having made a monkey of two adults in one night; and dismounted from her horse. She knew Ruffian only too well, and she knew that although he would put on a brave face, he was too old now to carry two people home. He was becoming more and more useless as a workhorse, and more and more precious as a friend. As she walked alongside him, wishing he could live for ever, her heart broke a little.

Chapter Two (#ua99d1feb-5903-5249-a8ee-8159066b0299)

Bess sauntered along behind her sister Mary who was moving at a quick pace, eager to get home to bed. Mary walked awkwardly in the stranger’s grey wool coat; she was glad of the warmth, but not the circumstances in which she’d acquired it, and the almost inaudible rustling of the fabric lining felt deafeningly loud to her.

Bess didn’t seem to notice the cold, she lost her balance every so often in her silver, t-strap Louis heels, but then with a click against the cobbles, she’d right herself again, scattering some of the ha’penny bag of chip shop scraps in her wake. Chip shop scraps were all they seemed to eat for their tea these days, and on this occasion, Bess was lucky that they’d been passing a chippy that was still open so that Mary could get her something hot on their way home.

Bess offered some to her sister as she trotted faster to try to keep with her. ‘Don’t you want any? They’re lovely and tasty; I love the smell of hot vinegar when it gets into the paper and goes all tangy.’

‘You eat them. Mother’s not got us anything in for breakfast so that’ll have to do you until dinner time at work.’

‘I don’t mind. I don’t get hungry in the morning.’

Mary’s wandering mind was interrupted by a call from the house opposite to their own:

‘You found her then?’

‘Yes, thank you Mrs Grimshaw.’ Mary tried to shove her sister unceremoniously through the soot-blackened front door. Leaping at the chance to start a cheery conversation with the neighbour, Bess called over Mary’s shoulder:

‘Goodnight, Mrs Grimshaw! Thank you for the lovely bread you left—’

‘Don’t start that, just get inside.’ Mary whispered to her sister, ‘You’ll wake the whole street.’

‘You’re alright.’ The neighbour sucked casually on her old white clay pipe as she stood on her doorstep, placidly waiting for Mary knew-not-what.

She always did that, Mary thought to herself, she was always standing on her front step in her slippers and housecoat smoking on a pipe waiting for nothing in particular when they got back late. It was an unfortunate coincidence that Mrs Grimshaw always seemed to go out for a pipe when Bess was out late, and Mary had gone to fetch her. What must the woman think of the pair of us? Then Mary realised that if Mrs Grimshaw thought her younger sister was a dirty stop out, then she was, in fact, correct. However, Mary preferred to think that her sister was somehow a special case and that it wasn’t as bad as it looked. Then she remembered what Bess had told her the preceding week and realised that it was worse.

‘I don’t know why you won’t let me pass the time of day with Mrs Grimshaw.’ Bess tottered into the front parlour that opened straight onto the street. She clattered over the bare boards on silver high heeled shoes as silly as herself while her sister lit a slim, farthing candle from the table beside the front door.

‘Take your shoes off; you’ll wake Mother.’ Mary didn’t need to look over to the corner of the parlour to know that their mother was asleep under grandad’s old army coat in her chair beside the dying embers of the range. As far as Mary could remember their mother had never stayed awake to see that they came home safely because, like Bess, her mother took it for granted that they always would. The reason she slept in the parlour was no late-night vigil for her only children, but the practical solution to the problem of space; since their father died they had been forced to make do with a one-up-one-down. Mary and Bess shared a bed upstairs in the only bedroom. At a squeeze, Mrs Norcliffe might have been able to fit into it with her daughters, but she had moved down to the parlour years ago.

Bess unfastened the dainty t-straps of her shoes and carried them with her up the creaking stairs to their bedroom. She didn’t lower her voice because her mother was deaf as a post and wouldn’t hear them, but they were both careful to tread softly, and in stockinged feet, to avoid shaking the floor and waking her that way.

‘I like her ever so much.’ Bess dropped the shoes onto the floor beside the dresser and hung up her coat on the open door of their wardrobe. ‘I think she wishes you’d talk to her more because I know that she’s very fond of you.’

‘Mrs Grimshaw does not like me.’ Mary said it as though it were a fact that she had come to terms with long ago and only shared in passing as she folded the stranger’s coat neatly and laid it in the corner furthest away from her as though it were a dangerous animal that might attack.

‘Oh, but she does!’ Bess’s large, blue baby-doll eyes were wide with concern and love, and she reached out to rub her sister’s shoulder reassuringly, ‘You worry too much, and if you’d just talk to people and let them get to know you—’

‘You’re too trusting.’ Unlike her sister, Mary didn’t have to remove cheap costume jewellery and climbed into their lumpy, old, but nonetheless welcome bed. ‘You’re used to everyone liking you, so you don’t see when you’re getting yourself into trouble.’

Bess had pulled on her nightdress and thrown her silk stockings carelessly over the top of her messily heaped shoes. ‘Your trouble,’ she threw her arms around her sister’s neck to give her a goodnight hug, ‘is that you’re too hard on yourself!’ Bess giggled, kissed her sister on the cheek and then wriggled down beneath the coverlet to sleep.

Mary was sitting up in bed, about to lean over and blow out the candle beside her, but in her exhaustion her mind caught up with what she had seen. Her sister had just taken off a pair of fancy-looking stockings, so Mary picked the candle up to cast the weak light a little higher. ‘Bess?’

‘Mmm.’

‘Are those silk stockings?’

‘Mmm.’ Bess hummed the affirmative contentedly into her pillow ‘They’re lovely.’

‘Where did you get them from?’

‘Tommo, he gave them to me as a present at lunchtime when I saw him at the factory gates.’

Mary turned to look down at her younger sister who had already closed her pretty, long-lashed eyes, and put her head on her faded-grey pillow. The candle wax melted down Mary’s knuckles but she ignored it. ‘I cannot believe you sometimes! I thought I told you that you weren’t to see him anymore. If he thinks that he can just—’

Bess pulled herself up in bed for a moment, leant over, and blew out her sister’s candle, plunging them both into darkness. Mary could feel Bess plonking her head back on her pillow and settling down to sleep. She sat up for a moment longer, debating whether or not to waste a match re-lighting it and trying to pursue the subject, but she knew better than to try. Her sister would never see reason, Mary would have to take matters into her own hands.

Diana could hear a church clock striking four o’clock in the morning somewhere down near Queen’s Road. She was standing in the dark, galley kitchen waiting for Tommo to return; she had waited all night. To pass the time Diana had attempted to clean up some of the usual detritus that littered her stepmother’s kitchen. An empty Oxo tin was lying on the flagstones, the crumbs trodden into the floor along with innumerable other ills. Diana had cleaned what she could without waking little Gracie and her stepmother. She had swept up crumbling shards of plaster that had fallen from the damp, mould-blackened walls; she had reset the rusted mouse trap and returned it to its place under the stove that badly needed blacking, and she had folded up the dirty sheets of newspaper that her stepmother had laid out on the kitchen table. None of them ever read much of the pages from the papers these days; the sheets were there to eat their bread and dripping off instead of crockery, and they were always a few days out of date.

As she had folded up the dirty sheets of the West Yorkshire Gazette, she’d cast her eye over stories about Italy, Spain, and Germany and fascists. The stories all seemed to weave into one another; the Spanish were fighting their fascist leader, the Germans were bombing the Spanish to stop them fighting the fascists, the Italians were with the Germans, and Londoners in the East End rioted. They’d shouted, ‘They shall not pass’ in Spanish when the British Union of Fascists had tried to march through Whitechapel. Fascism was spreading across Europe like the plague, and carefully constructed treaties were toppling all over the world like a flimsy house of cards.

A photograph in one of the newspapers caught Diana’s eye; it showed a razor-necked Oswald Mosley in his black, military-style uniform. He wore a black peaked cap like a police sergeant but his was emblazoned with the lightning bolt of the BUF, and the shiny peak was tilted rakishly over his right eye to disguise a slight squint. His uniform had echoes of Great War army officers, and an official status that he clearly longed for, but did not possess. Diana spat on his face before screwing up the damp-softened news sheets and cramming them into the empty grate of the stove. She didn’t like leaving anything about Mosley and his lot lying around if she could help it. Her stepbrother had a weakness for joining with the biggest bullies he could find, and she worried that it was only a matter of time before he realised there were even bigger fish than the criminals in Leeds that he so idolised.

Diana laid out fresh newspaper and saw a happier headline: Essie Ackland was singing at the Crystal Palace. Diana’s father had loved Essie Ackland, and she still had his wind-up gramophone in the parlour with his collection of records. She was feeling melancholy, and decided to put on one of her father’s favourites very quietly in the parlour so that the family upstairs wouldn’t hear. She crept through to the room at the front of the house and the cheap and dirty pine shelves that were built into the alcoves either side of the fireplace. In the right-hand alcove, a row of yellowing paper record sleeves stood as a lone reminder of happier times in a better place. Diana gently ran her fingertips along the record jackets that were so familiar to her now that she could tell them by their worn corners without reading their labels. She picked out Essie’s recording of ‘Goodbye’. It was an old favourite, and as she lowered the needle to the shining black disc, she felt she even remembered the pattern of crackles that preceded that haunting opening bar.

Diana lowered herself into the horsehair armchair that had seen better days, and closed her eyes, imagining she was in the Crystal Palace with her late father.

Her moment was rudely interrupted as she heard Tommo fighting with the lock of their front door. She pulled herself up out of her chair, lovingly returned the record to its sleeve, and its sleeve to its shelf, and returned to the darkness of the kitchen before he’d even managed to get his latchkey into the door. She waited with arms folded.

The house they shared with Tommo’s mother was only a two-up-two-down which meant that from where Diana leant against the kitchen sink she could see straight into the hallway. As Tommo entered the house, he could see her in the shadows.

‘Wharra you lookin’ at?’ Tommo was even more disgusting to her than usual. A cigarette butt clung to the wet bottom lip of his wide and ugly mouth. As he sneered at her, he revealed dirty, crooked teeth. It was times like these that she pitied Bess; the girl could do immeasurably better than Tommo Cartwright.

‘You didn’t pay the rent.’ Diana walked through to the parlour but didn’t get very close before the fumes of beer and gin on her brother’s stinking breath hit her.

‘You pay it for a change. What do you think I am? Yer bleeding …’ Tommo waved a skinny wrist around ‘… money machine.’

‘I buy the food. Where’s the rent money.’

‘I spent it.’

Diana knew that he wouldn’t be short of money. It might not be his, but he always had some. ‘Are you telling me you’ve got nothing? Are you telling me you’re no better than anyone else on this street?’ She knew that would rile him and if he had any money it would soon show itself just to prove his superiority; Diana had been pressing her stepbrother’s buttons for years and it was second nature now, undignified though it might be.

Tommo pulled himself up an inch or two taller and with drunken slur said, ‘I’m never penniless.’ He reached into his various pockets and pulled out a crumpled, damp pound note and a collection of coins and detritus, all of which he threw onto the floor disdainfully.

Their rent was ten shillings, and Diana had no intention of taking any more or less than that. She bent down and picked it up coin by coin in silence and with as much dignity as she could muster.

‘What’s this?’ she said, unfurling a slip of paper.

Tommo sniffed and snatched it out of her outstretched hand. ‘That’s me being clever, that is.’

Diana had seen what it was; a betting slip from an illegal bookmakers that had been written out by hand. They’d been taking bets on whether or not the coronation of the new King was still going to happen in a few months’ time, and Tommo had put on five shillings against. ‘How is that you being clever?’

‘I saw it in the paper, didn’t I? Everyone’s saying it won’t happen. He’ll off hisself before then. That’s how them toffs get out of a jam; no brains.’

Diana didn’t say anything. There was no point telling him that he was disgusting for laying bets that another human being would take his own life; king or not. Diana turned to walk up the stairs. ‘Keep your voice down,’ she told him, ‘I don’t want you waking the house.’

Diana returned upstairs to the room she shared with little Gracie. All the houses in their street were two-up-two-down, but being the middle house in Vickerman Street, they had one small extra attic room that jutted out of the row of rooftops; to Diana, it was a lifesaver. When her stepmother had offered it to Diana, she had been apologetic about the damp, the smallness, the drafts and the mice, but Diana had been too relieved to care. Diana was still glad not to have to share a room with her stepmother; her stepmother was a kind woman, but she snored like a drain.

Diana went to her single small window that looked out over the town; it wouldn’t be light for hours. The street lamps picked out the undulations of the valley, the warren of tightly packed tiny rooftops, silhouettes of enormous factory chimneys rose up like an industrial forest of brick-built trees giving life and death to the town simultaneously, with their jobs and their smoke.

Diana couldn’t go back to bed now; she was too wide awake, and she didn’t want to wake Gracie. Now that she had money to pay the rent, that was one battle over, but as soon as she won one battle there was always another. Life was a never-ending series of battlegrounds, and she had no one to fight by her side. She missed her father so much it hurt; he had been her sole champion, and he had never taken any of Tommo’s nonsense. Diana remembered the first time Tommo had talked about getting himself involved with the Leeds gangs, and her father had locked him in the coal shed until he had agreed not to go looking for trouble. What would her father say if he could see her now? Living in Ethel’s attic room, the house full of stolen goods that Tommo was fencing to his Leeds connections, and not a hope of ever escaping. Her father would have laughed Tommo to scorn for giving himself a ridiculous name like ‘The Blade’, and he’d have made sure that Diana didn’t have to live in a house with stolen goods inside. Diana wished her dad was there; she wished he’d been there to help her save Gracie from the dirt, the damp and the life they were having to live.

It was the tenth of October, and when Reenie woke up she remembered that it was Saturday and today was her birthday. Her little brother’s present to her was to muck out Ruffian’s shed, so she didn’t have to and her sister had promised to bake the bread. They had both got up early to do her jobs and had given her the bed to herself, and she was delighted.

As she lay, like a starfish, across the lumpy mattress that she had shared with Katherine since as long as they could remember, she planned her day. Reenie liked to plan her day so that she could get the absolute most out of it she possibly could. Today she thought she’d bring forward wash day; nothing gave her a feeling of achievement quite like the sight of sheets being bleached by the sun on a dry day. All those girls she’d known at school who had gone off to get fancy jobs in shops, and tea houses, and the coveted piece-work places at the sweet factories, they couldn’t possibly know the true satisfaction of a successfully completed wash day. At least, that’s what she kept telling herself. She was better off at home; those stuck up girls could keep their stinking jobs, she had enough to do. And as for going into service; she didn’t even want to think about that.

Reenie couldn’t help dwelling on the words of the Salvation Army lady that she had met the night before; it was too late for Reenie to go back to school now that she was sixteen, but her mother was always nagging her about secretarial classes, or teaching herself shorthand. ‘If you don’t do something with your life you’ll end up living from week to week in the pawnbrokers like your Uncle Mal,’ her mum was always saying. Reenie had just never been any good at school work or anything like that; she would always prefer to be useful at home than useless in a classroom. She didn’t necessarily like all of the jobs that she did at home (the ones she particularly disliked she had farmed out to her siblings that day), but working at home gave her a sense of purpose, and that was what she wanted. Reenie did have a dream, but she tried not to think about it; better to be useful.

‘Reenie!’ Her mother called from the kitchen, ‘Reenie, are you up yet?’

‘It’s my birthday! I don’t have to do ’owt!’

‘You’ve got a present!’

‘I know, and I’m making the most of it!’

‘You’ve got to come down here and open it!’

Reenie sat up. Open her present? She never had presents that you opened; there’d sometimes be something for one of the younger ones, but she was sixteen now and past all that stuff. Reenie threw off the thick, warm layers of blankets that she’d been hiding in like a cocoon, and fumbled for her father’s old slippers and her coat to put on over her nightshirt so that she didn’t freeze on her way down to the kitchen. Even though it was only October, it was still Halifax in October. She ran a comb through her shoulder-length, bright auburn hair and tied it back hastily hoping that if she did it herself, her mother wouldn’t pounce on her with a brush while she tried to eat her breakfast. She turned and neatened the bedclothes, disappointed that she was having to leave her warm cocoon so early, and then made her way down the stairs that she’d swept only the day before.

‘There you are! I thought you’d never get up. Sit down and open this.’

Reenie looked down at the scrubbed kitchen table where an ominous-looking parcel was waiting for her, wrapped in newspaper and tied with string. Reenie sidled into the middle of the bench underneath it and looked up at her family, trying to conceal her confusion. She lifted the parcel gingerly, the crisply ironed newspaper still warm against her fingertips; she could tell immediately what it was. She wondered what precious object they had sold or pawned to raise the money to buy her something so unnecessary, and how long it would take them to buy it back. She hoped they hadn’t pawned the kettle because she wanted her tea.

Reenie turned over the parcel in her hands and made a show for her family of being excited and surprised, but out of the corner of her eye, she was scanning the kitchen to see what was missing. The ramshackle, low-ceilinged, worn-out old farmhouse kitchen looked unchanged: the freshly blackened range was hot enough to be boiling the kettle (which was a minute or two off singing); the pink china that her mother saved for best was drying on the wooden rack beside the sink that was big enough to bathe in. The old pine table and benches, discoloured with age and use and her daily scrubbing, were all where they should be. Out of the windows, she could see Ruffian chewing up the paddock, and wondered how much longer he could last with no money for the vet.

‘Are you checking on Ruffian!’ Her brother had caught her furtive glance out of the window and was outraged. ‘I told you I’d see to him, and I will, I just—’

‘All right, that’s enough you two, don’t start.’ Reenie’s mother went to see to the kettle. ‘Reenie’s got to hurry up this morning. Reenie, open your present, love.’

‘Why have I got to hurry up?’

‘Just open your present, love, there’s a good lass.’

Reenie tentatively pulled at the string of the parcel. She was almost certain she knew what it was before she opened it, but as the inky paper fell away, she furrowed her brow in puzzlement. There, as she had expected, was a ½ lb tin of toffees that they couldn’t afford, but what she hadn’t expected was the envelope stuck to the top of the tin with her name typed on a typewriter; they didn’t know anyone with a typewriter. These weren’t cheap toffees either, these were Mackintosh’s Celebrated Toffees. Even the tin, decorated with dancing carnival figures, and a lid edged in red and gold, was alive with magic.

‘Go on, keep going, open that too.’

Reenie was stunned into silence, and she was about to open the lid of the tin when her younger sister said: ‘No, silly, open the envelope.’ Reenie could see that Katherine was even more excited than her, and that her mother must have let her in on the surprise.

John looked around in annoyance as he realised he’d been kept out of their circle, but his mother shushed him.

‘Is this what I think it is?’ Reenie, usually so loud and confident was quiet and nervous now. She turned the white, business-like envelope over in her work-worn fingers and took a deep breath.

‘Only one way to find out, love. But best hurry, eh?’ Her mother passed a clean table knife towards her daughter, and Reenie picked it up and slid it along the gummed seal.

There was a long silence as Reenie held her breath not daring to look at the page, and then she read aloud the first official letter addressed to her in her short life. ‘Dear Miss Calder, We are pleased to offer you the position of Seasonal Production Line Assistant in our Halifax factory …’ Reenie gasped in surprise and delight. ‘Oh, Mum! I’ve got a job! I’ve got a job! I’m going to Mackintosh’s! I’m going to Toffee Town! They’ve given me a job!’

‘I know, love; I wrote to them. They got a reference from Miss Dukes at your school, and a reference from the vicar, and we had such a time keeping it a secret in case it didn’t come off, and then they wrote and said they wanted you to start right away.’

‘Right away? Well, when right away?’

‘Today! So go and wash your neck and get a wiggle on. Your birthday present from me is a job.’

‘Don’t I have to have an interview?’

‘What sort of job do you think it is? Chief Accountant? You’re not going into the offices; you’re packing cartons, and every day’s your interview. Be faster than everyone else, and they’ll keep you until Christmas.’

‘If I’m faster than anyone they’ve ever had do you think they might keep me longer than—’

‘Now don’t go getting attached; you know what you’re like. Just be glad that you’ve got until Christmas and enjoy it. It’s not everyone that gets into Mack’s.’

‘But if I were really, really fast and they’d had loads of girls leave at Christmas for Christmas weddings—’

‘Christmas weddings? How many droves of girls are you expecting to leave for Christmas weddings?’

‘Well, just say if there were a lot, do you think there’s a chance that I might not have to go into service?’

Mrs Calder dried her hands on her apron and sat down at the edge of the table. ‘Now listen, you three, I know you all talk like goin’ into service is the worst thing in the world, and I know I used to tell you some terrible stories of what it was like in my day. Being in service now isn’t like it used to be; you hardly ever have to live-in, and they all send their laundry out. Look, what I’m saying is: if any of you do have to go into service I think you’ll have a wonderful time.’ Reenie’s mother tried to appeal to Reenie’s imagination, ‘Reenie, what if you went into service in a little place, and then a fine lady visited and spotted you, and you got to go to work in a big house and make friends with all the quality? Can you imagine?’

Reenie’s tight-lipped smile gave her away; she was trying to agree with her mother, but in her heart of hearts Reenie desperately didn’t want to. Reenie had hope now, and it was a letter from Mackintosh’s.

The overlooker who was showing the new girls their place marched them through the corridor of the factory walking two-by-two in what she called a ‘crocodile’. As far as Reenie could tell the overlookers were to the factories what the teachers were to her old school, and Reenie was immediately in awe of them. The overlookers decided where the girls went, which jobs they worked at, and how long for. Everyone wanted to stay in the overlookers good books.

‘No talkin’ at the back! Listen wi’ your ears, not wi’ your mouths! You are going to walk through here every day for the next several years if you’re lucky, but no one is going to show you where to go after today, so remember where you’re goin.”

Reenie followed dutifully, memorising the plan of the building in her head: up through the old Albion Mill, along a wide corridor where she could see the railway line running parallel, down three flights of stairs and up another two. By Reenie’s reckoning this older girl, who’d collected them at the gates, seemed to be doubling back on herself to make them go a longer route. ‘Excuse me!’ Reenie was a third of the way down the crocodile of obedient new girls, but she was near enough to the front to shout naive, well-meant questions. ‘Why did you take us down two flights of stairs and then up another two? Is there not some—’

‘No questions, you’re here to go where you’re told.’

‘Are you lost, though,’ Reenie tried to sound kind because she couldn’t imagine that this girl enjoyed being lost, ‘because if you’re lost, we could just stop someone and ask them for directions. Excuse me!’ Reenie called out to two gentlemen who were passing them in the echoing, whitewashed corridor. ‘Sorry to bother you,’ she paused for a happy moment as she realised that she recognised one of them, ‘but we’re on our way to the—’

‘We are not stopping! Follow me, please.’ The older girl tried to hurry the girls along, but the older of the two gentlemen raised his hand politely to indicate that they should all stay.

‘Good morning, ladies.’ He made a slight bow of his head in a style that was almost Victorian. He was an older man, perhaps getting close to retirement; thick silver hair, bold silver moustache, dark blue neatly cut suit. ‘I am Major Fergusson, and this is my colleague Peter McKenzie. Is this your first day at Mack’s?’

A chorus of ‘Yes, sir’ rang through the corridor and the crocodile line of girls all fixed their eyes on the young man beside Major Fergusson.

‘Well, isn’t that nice. And what is your name?’

‘Reenie Calder, sir.’ Reenie tried to look at him as she spoke, but her eyes darted to Peter to see if he would recognise her. She willed him to recognise her.

‘And where are you going to, Reenie?’

‘Don’t answer him!’ The girl in charge was determined to get them away, ‘They’re the Time and Motion men, and you don’t talk to the Time and Motion men without your Union present.’

In the face of such obvious rudeness, Major Fergusson and Peter remained pleasant and calm; this was a sign, Reenie thought, of what her mother called ‘Good Breeding’.

‘We are here to help everyone find a way of doing their jobs more easily,’ the Major said to Reenie, ‘sometimes we conduct tests on the way the line works and in those circumstances, we have to work with the Unions to make sure that we are all helping each other. You can all talk to us any time, there’s no need to be shy, or to ask permission of your Union.’

‘I think that’s quite enough—’ their guide was silenced with another polite bow of the Major’s hand. He clearly out-ranked her but didn’t enjoy showing it. The Major smiled at Reenie and permitted her to speak:

‘Can we ask you for directions?’ Reenie didn’t like to contradict her guide, but she suspected that the other girl needed some help. Reenie, in her naivety, believed she’d be doing the girl a kindness if she did the asking for her. ‘It’s just an overlooker is taking us to our new workstations, and we’ve been told to memorise the route that we’re going along because we’ll need to go this way every day, but I don’t think it’s right.’

‘What makes you think that?’ The Major was either ignorant of the girls gazing wistfully into Peter’s smoke-grey eyes, or he was used to it.

Reenie didn’t need time to think, ‘Well, we came in by green painted double doors at the end of the old mill. We passed the timekeeping office where there were three commissionaires having their breakfast butties; then we went under a staircase where some fella in shiny shoes was smokin’ and chattin’ up a lass. Then we went out a single door – which was right small for all of us – into a yard where there was some men unloading sacks of sugar off a waggon. At the other end of the yard there was a sign that said no waiting, and we went past that into a new block where we went up three flights of stairs, then down a big corridor with a pine floor and big window frame that smelled of new paint. From there we walked down two flights of stairs just back there through that door which you can see from the window is loopin’ us back to Albion Mills, so why can’t we just stay in Albion Mills in the first place? Are we lost?’

The Major gave Peter another knowing, amused look; he supposed that this rigmarole the guide was putting them through was more imaginative then sending them for ‘a long stand’.

‘You remembered all of that?’ the Major seemed to admire Reenie for it, and the other girls were intensely jealous of the beautiful, wide-eyed smile that Peter gave her.

‘Well, it has only just happened. I’m not a total doyle.’

‘Young lady,’ the Major was addressing Reenie again, but eyeing her guide with suspicion, ‘you mentioned that you had already met your overlooker. Where did she go after you met her?’

‘Well this is her, this is our overlooker.’

The guide gulped the air like a fish and stammered out defensively, ‘I’m the overlooker of the new girls on their first day when they go through to their new places. It’s very easy for them to wander about and get lost and someone needs to give them a firm—’

The Major ignored her and spoke directly to Reenie. ‘overlookers all have coloured collars on their white overalls. They are either red, blue, yellow, or green. If you see someone with a white overall, you know that they are the same rank and file as you.’ He didn’t point out that their guide’s collar was white, or that she’d been deliberately taking them a longer route so that they would be lost for the whole of their first week at Mack’s; he didn’t need to. ‘Now, let’s see if we can’t get you all on to your first day on the double. Peter, we’ve got time for a detour this morning, haven’t we?’

Peter nodded brusquely.

‘I think I can guess where you’re all going to. Quality Street line, by any chance?’ the Major asked Reenie.

‘Yes, how did you know that?’

‘It’s all hands on deck at Quality Street, my dear. Christmas is coming!’

Reenie and the girls followed the Major to their new line, and although Reenie caught Peter’s eye, he didn’t speak to her. He smiled, and then he smiled again, but he didn’t speak.

When Diana arrived at the toffee factory gates that Saturday morning, tired from very little sleep the night before, she was disgruntled to be stopped by the watchman. Diana tended to go in by one of the lesser-used entrances on the Bailey Hall road to avoid the undignified crush at the start and end of each shift. It added a few minutes to her journey, but Diana didn’t care; dignity was more important to her than an inconvenience. The morning was crisp but not cold; the Indian summer of 1936, but she still wore her father’s coat and her plain work shoes. A light wave of her ashes and caramel-coloured hair fell over tired eyes, and she slipped through the factory gate with her head down, her collar up, and her hands in her pockets like any other working day.

‘Diana Moore?’ The factory watchman had stepped out of his gatehouse cabin with a note in his hand.

‘You know I am.’ She said with an exasperated sigh.

‘Message for you.’ He handed over an internal memo envelope and went back to his business; answering queries from men who’d turned up on spec looking for work.

Diana moved out of the stream of other workers and found a quiet recess in a soot-blackened brick wall where she could stand apart and read the message. The note was evidently from someone who knew which gate she always used, or they’d left a note at every gate; either way she felt a slight discomfort about it. Diana was well known, but she didn’t like to be that well known.

Mackintosh’s Women’s Employment Department

October 10th,1936

Dear Diana,

Please present yourself at the office of Mrs Wilke’s on your arrival today.

Yours sincerely,

Miss Watson

Secretary to the Women’s Employment Manager

Diana realised that Mrs Wilkes of the Women’s Employment Department was waiting for her. This was unusual, but it didn’t worry her; she knew that her job was not at risk. Diana knew that the factory couldn’t run half the lines without her. This wasn’t arrogance on her part; arrogance would mean that she enjoyed her position. In reality, Diana simply didn’t care anymore. There had been a time, years ago when she had relished ruling the roost, but now the daily pettiness was exhausting, and keeping the younger girls in line was just one more battle for her.

Diana assumed that she was going to be asked to use her influence, unofficially, with some wayward girl or other; perhaps put down a group of troublemakers before they could put their own jobs at risk. It happened often enough. The senior management of the Mackintosh’s business had realised long ago that it was more efficient to allow the girls to manage themselves, and Diana would occasionally be invited to the grand old directors’ floor of the Art Deco office block to be unofficially asked to ‘Have a word.’ She never met the directors themselves; they were all down in Norwich at the newly acquired Caley factory. Rumour had it that they thought Norwich was more refined and they were moving there en masse to run the business remotely. It didn’t make any difference to Diana, they sometimes came down to the factory floor to talk to one another while pointing out different machines, but they didn’t speak to her or any of the other girls.

She folded the note and slipped it into the inside pocket of her old coat and began weaving her way in and out of the workers, wagons, and factory outhouses to the opulent main office building, and her interview with Mrs Wilkes.

Diana knew her way to Mrs Wilkes’ office; she’d had to go there nearly six years previously when a different Women’s Employment Manager had been in place. Diana had gone there to make her case for an extended leave of absence to care for a sick relative in the country, and whether the manager at that time had believed her or not, she’d argued persuasively and they’d let her go. Diana went in through the deco door decorated with M’s, and up the six flights of winding white stairs with crisscrossed iron bannisters like giant strings of cat’s cradle. The upper landing opened onto a hexagonal hallway, lined with the doors to the director’s offices. She didn’t want to linger long, her objective was to get in and out and back to work as quickly as possible.

In the centre of the hallway was a large antique hexagonal table, decorated with an intricate pattern of walnut veneer. High above, there was a sparkling, domed ceiling in every colour of glass, as though the hallway were a tin of cellophane-wrapped toffees bursting into the Halifax sky. Diana marvelled at the extravagance of it.

Following the narrow corridor at the other end of the hexagon, Diana found the door of Mrs Wilke’s office. It looked like it would be less out of place in a stately home, oak-panels were decorated alternately with an acorn, oak leaf or the letter ‘M’. The Mackintosh family were proud of the acorn from which their great oak of a business had grown.

Diana knocked three sharp raps and then waited.

‘Come!’

Diana realised that although she knew Mrs Wilkes name well enough, she didn’t think she had ever seen her and was surprised by what waited for her on the other side of the door. A straight-backed woman in a cream silk blouse looked up from paperwork on her grand desk, but she was not an ogre like her overlooker Frances Roth; she had the potential to be far less easy to manipulate. Diana made immediate assumptions about this Mrs Wilkes: grammar school girl, father a doctor, comfortable upbringing but not so comfortable that she didn’t have to work hard at school, turned down an offer or two of marriage from an earnest young man because they didn’t have enough money. Probably thinks all the factory girls are no more than beasts of burden, or wayward children.

Mrs Wilkes was undoubtedly a woman who had always possessed good looks; she was perhaps ten or fifteen years older than Diana. She still had a trim figure, and her neat, glossy hair framed her face in a way that enhanced its symmetry.

Diana thought that she could respect Mrs Wilkes, but she didn’t know if she could really trust her. Mrs Wilkes didn’t mix with the factory floor workforce; she was strictly an office manager and rarely ventured out of the smart Art Deco tower. Diana was more accustomed to life in the old mill buildings where her co-workers made the chocolate and toffee. Diana didn’t know Mrs Wilkes’ first name; she knew that the woman wasn’t married because married women weren’t permitted to keep their jobs at Mackintosh’s Toffee Factory. But then again, married women weren’t allowed to keep their jobs anywhere after they married, unless there was another war.