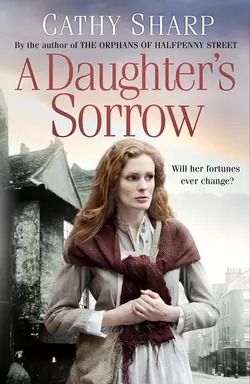

A Daughter’s Sorrow

Cathy Sharp

Heartache and hardship in London’s East End, from the bestselling author of The Orphans of Halfpenny StreetBridget has always been the one to take on the responsibility for looking after her family. With a drunken, violent mother, an unemployed brother who can't stay out of pub brawls and a wayward sister vulnerable to the smooth talk of shady men, it's hardly surprising when she falls for cheeky local lad, Ernie.But when he breaks her heart, she is drawn to the kind figure of Joe, despite the bad boys of the criminal underworld who lurk in the shadows and seem to have him in their sights.Bridget and Joe try hard to keep a hold on their livelihoods and to keep to the straight and narrow path, but misfortune dogs them and it seems that happiness is always just out of reach…

Copyright (#ua6a5f0f3-8d21-59c9-8916-5173fed1464e)

Harper

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd

The News Building

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

First published as ‘Bridget’ in Great Britain by Severn House Large Print 2003

Copyright © Linda Sole

Cover design © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2017

Cover photographs © Jeff Cottenden (girl); Heritage Images/Getty Images (background).

Linda Sole asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

A catalogue copy of this book is available from the British Library.

This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins.

Source ISBN: 9780008168582

Ebook Edition © January 2017 ISBN: 9780008168599

Version: 2016-12-08

Contents

Cover (#u1eeac3b7-fddb-58c3-9c0c-9af3a9dd821b)

Title Page (#u4374e8b5-607f-587f-970d-dec2aa2dd757)

Copyright

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Keep Reading …

About the Author

Also by Cathy Sharp

About the Publisher

One (#ua6a5f0f3-8d21-59c9-8916-5173fed1464e)

The sound of a foghorn somewhere out on the river was almost lost in the noise of chucking-out time at the Cock & Feathers, known locally simply as the Feathers. Lying in my bed in the little room at the back of the house, I heard the usual screams, yells and scuffles from the pub at the end of the lane. I was used to it and it was not the petty squabbles of my neighbours that had woken me. No, this was something much closer to home.

‘Can I get into bed with you, Bridget?’

I smiled at the sight of my six-year-old brother dressed in a worn flannel shirt that was three sizes too big for him and reached down to his ankles. Beneath that ridiculous shirt was a painfully thin body; he was hardly more than skin and bone and worried me more than I’d ever let on to him or anyone else.

‘O’ course you can, Tommy. Was it them villains from the pub that woke you?’

‘It’s our mam,’ Tommy whispered, and coughed as he tugged the thin blanket up to his chest and burrowed further down into the lumpy feather bed my sister and I usually shared. ‘She’s having a right old go at Lainie again.’

No sooner had he spoken than there was an almighty crash downstairs in the kitchen. Tommy shivered and I folded my arms about him protectively as our mother suddenly screamed out a torrent of abuse.

‘You’re a slut and a whore – and ’tis after throwing you out of the house, I am.’

The spiteful words could be clearly heard by us as we lay in bed, Tommy shivering against my side as he always did when Mam was in one of her rages.

‘Whatever I am, it’s what you made me, and if I go you’ll be the one to lose by it, Martha O’Rourke. It’s four shillings a week you’ll be missin’ if I leave,’ Lainie shrieked, full of anger. ‘You’re a cold-hearted bitch and I’ll be glad to see the back of this place, but you’ll not take too kindly to going without your drop of the good stuff.’

‘And we all know where the money comes from! You’ve been down the Seamen’s Mission again, selling yourself to them foreigners.’

‘Hans loves me and one day he’ll be wedding me. You know he’s the only one, Mam. I don’t know why you take on so. Our da was working the ships when you met him – and our Jamie was on the way before the wedd—’

There was a scream of rage from downstairs and then more crashing sounds as furniture was sent flying. Our mother and sister were having one of their frequent fights, which always upset Tommy. They weren’t the only ones to indulge – similar fights went on in houses up and down the street, especially on a Friday night – but Martha O’Rourke could be vicious and I was anxious for my sister.

‘If your father was here, he’d take his belt to you!’

‘Give over, Mam …’ Lainie gave a little scream.

I jumped out of bed and hastily pulled on my dress. I was worried about my sister leaving. Lainie wasn’t going to put up with much more. She would walk out, and then where would the rest of us be?

‘Where are you going?’ Tommy said, alarmed.

‘You stop here. I’m going to creep down and see what Mam’s doing to our Lainie. She’ll kill her one of these days if no one stops her.’

Tommy clutched at my hand, his wide, frightened eyes silently begging me not to leave him. He was terrified of Mam when she was in one of her rages, and with good cause. We had all felt the back of Martha O’Rourke’s hand often enough. She was a terrible tyrant when she was in a temper.

Even as I hesitated, I heard Lainie slam the kitchen door and I knew I had to hurry, but Tommy was hanging on for dear life.

‘You’ll be all right here. I shan’t let Mam see me, and I’ll be back before you know it. There’s no need to worry, me darlin’.’

Leaving Tommy, I crept along the painted boards of the landing on bare feet and began a careful descent of the stairs. They were uncovered stained wood and creaked if you stepped on the wrong spot, but I had become an expert at avoiding the creaks. This was hardly surprising since I was the one who scrubbed them three times a week from top to bottom.

‘Lainie …’ I whispered as I saw her at the door. ‘Don’t go …’

Either she didn’t hear me or she was too angry to listen as she left the house and banged the door after her with a vengeance. I ran down the rest of the stairs as quickly as I could, forgetting to avoid the creaks in my hurry which brought Mam to the door of the kitchen.

‘And where do you think you’re going at this time of night? Off down the docks to be a whore like your slut of a sister, I suppose?’

‘I’m going after Lainie. You can’t throw her out, Mam. It isn’t fair!’

‘I’ll give you the back of me hand, girl!’ She started forward purposefully but I took a deep breath and dodged past her, knowing that I was risking retribution later. Lainie had to come back, it would be unbearable at home without her. Besides, where would she go at this time of night?

When I reached the street, I saw that she was almost at the end of the lane and I called to her desperately, running to catch up with her. She looked back reluctantly, then slowed her footsteps and finally waited for me at the top of the lane.

‘What do you want?’

‘You’re not really going to leave us, are you? I can’t bear it if you go, Lainie – I can’t!’

The note of desperation in my voice must have got through to her, because her sulky expression suddenly disappeared as she said, ‘Sure, it’s not the end of the world, Bridget darlin’. I’ll only be living a few streets away, leastwise until Hans’ ship gets back. After that, I don’t know where I’ll be – but I’ll be seeing you before then. You can come to me if you want me. If I stay here Mam will kill me – or I’ll do for her. I’m best out of the way. You know it’s true, in your heart.’

‘But we’ll miss you – Tommy and me. You know Jamie can’t stand to be around her …’

Jamie, our elder brother, was going on twenty and seldom in the house. Mam yelled at him if she got the chance, but he was a big-boned lad and she didn’t dare hit him the way she did us. He took after Da, who had a reputation for being handy with his fists, and would have hit her back.

‘I’ll miss both of you, me darlin’,’ Lainie said and her eyes were bright with tears she would not shed. ‘I can’t stay another day, Bridget. Sure, I know ’tis hard for you, darlin’, but you’ve Mr Phillips to help you – and our Jamie if you need him. Until he gets sent down the line, leastwise.’

‘Oh, Lainie!’ I cried fearfully. ‘He’s not in trouble again?’

‘When have you ever known our Jamie not to be in trouble? He’s like Da. He hits out first and thinks after. One of these days he’ll do for someone – and then they’ll hang him.’

‘Please don’t,’ I begged. I stared at Lainie’s pretty face, hoping that she was joking, but there was no sign of a smile in her soft green eyes. ‘I can’t bear it when you talk like that. Ever since Da drowned—’

‘Huh!’ Lainie flicked back her fair hair. She was as fair as I was dark and far prettier than I thought I could ever be. She also smelled of a sweet rose perfume that Hans had given her. ‘Mam has been lying to us, our Bridget. There was no body – no proof he drowned. From the way the old bill haunted us for months, I reckon they know the truth. Jamie says he was away on a ship to America.’

‘Do you think that’s what happened?’ I looked at her anxiously. I’d cried myself to sleep after Mam told us our father had drowned in the docks. I’d had nightmares about him being down there in the river somewhere, his body eaten by fish.

‘I shouldn’t be surprised,’ Lainie said. ‘They’re always looking for someone to take on down the docks. When crew have jumped ship or drunk themselves silly and not signed back on. Hans says it’s likely Da was taken on and no questions asked.’

‘Then he might still be alive?’

‘For all the good it will do any of us,’ Lainie said and pulled a face. ‘If he got away, he’ll not be after coming back. He’d be arrested as soon as they saw him. It was months before the law stopped hunting him. They haunted our Jamie at work, and watched the house. Da knows he’d hang for sure.’

‘Yes, I’m sure you’re right. It was better in the house before he left, that’s all.’

‘Only because he put his fist in her mouth if she opened it too wide. Don’t you remember all their rows?’

I remembered well enough, even though Sam O’Rourke had been gone for five years – years that his absence had made much harder for us all – but I also recalled Da giving me a halfpenny for sweets a few times. He had liked to ruffle my hair and call me his ‘darlin’ girl’.

‘Yes, I remember.’ I looked pleadingly at her. ‘You won’t change your mind and stay? Not even until the morning?’

‘I can’t,’ Lainie said and her mouth set into a stubborn, sullen line, which told me there would be no changing her. ‘Hans has begged me to leave home a thousand times. I only stayed as long as this for you and Tommy.’

‘What about your things? What are you going to do, Lainie? You can’t walk about all night—’

‘There isn’t much I want back at the house. I’m going to Bridie Macpherson. She’s asked me to work for her and she’ll provide uniforms. Hans will be back soon; he’ll give me money for what I need and then I shall go away with him. You can have my stuff and if I think of anything I want, I’ll let you know and you can smuggle it out to me.’

‘Will Hans marry you, Lainie?’

‘Yes.’ She smiled confidently. ‘He knows he’s the only one. I’ve never had another feller, Bridget. Mam carries on the way she does because he’s Swedish and not a Catholic, but Hans doesn’t care about that. He says he’ll convert if it’s the only way he can wed me.’

‘I’m glad for you.’ I loved my sister and I was going to miss her like hell, but I couldn’t hold her against her will. ‘Yes, yes, you must go, Lainie. It’s your chance of a better life.’

‘You’ll be all right,’ Lainie replied. ‘You’re clever, Bridget. I think you must take after great grandfather O’Rourke. He came over to England in 1827 when they were clearing the land for St Katherine’s Docks. They say he had a bit o’ money behind him, but he died of the cholera – there used to be a lot of it in the lanes in them days.

‘Grandfather O’Rourke was a lad of six years then, and his mother a widow with five small children. She had to struggle to bring them all up. When our grandfather was old enough to work, he started out as a labourer but ended as a foreman, running a gang under him. He would have done well for himself if he hadn’t taken a virulent fever and died. Leastwise, that’s what Granny always told us. Do you remember her at all?’

I had a vague memory of a white-haired woman in a black dress. ‘Yes, I think so. She used to sit on her doorstep and smoke a long-stemmed clay pipe, didn’t she?’

‘Yes.’ Lainie chuckled. ‘She died when you were about three. She was forever talking about the Old Country – and her brogue was so thick that I couldn’t always understand her.’

I stopped walking and looked back. We had already come a couple of streets and I knew Tommy would be waiting anxiously for my return.

‘I’d better get back then,’ I said and leaned towards her, kissing her cheek once more. ‘Take care of yourself, Lainie.’

‘You take care of yourself too, Bridget – and don’t let Mam bully you too much.’

I nodded, but it was easy for Lainie to say. She was nearly eighteen and she had someone who cared for her. I was almost a year younger and I couldn’t just walk out the way she had – someone had to watch out for Tommy.

Mam would be in a temper when I got back, but I was used to that. I hated to see Lainie go, but there was no point in making a fuss over spilled milk. I supposed Lainie ought to have left home long ago. She would be much happier working for Bridie – even though the hotel owner was a bit mean from all accounts.

I liked Mrs Macpherson, but then I didn’t have to work for her. She was a widow who had come to live near St Katherine’s Docks three years earlier and seemed to be a plump friendly person. When she had taken over the Sailor’s Rest, it had been a run-down hovel, but she had built it into a thriving business.

My thoughts were still with my sister as I walked slowly home, deliberately loitering despite the bitter cold, which was chilling me through to the bone. I knew what was waiting for me when I got back and I wasn’t looking forward to the row with Mam, who would take out her frustrations on me now that Lainie had gone.

It was only after a few minutes of walking on my own that I realized how late and dark it was in the lane. Most of the houses were shuttered, their lamps extinguished. I had never been out this late alone before. Nervously, I glanced over my shoulder as I sensed someone was watching me … following me even. Chills ran through me, giving me goose pimples all over; I was suddenly frightened.

The East End of London was a harsh dirty place in 1899, its air polluted by the smoke of the industrial revolution that had taken place throughout most of the past century. Crime was rife in the narrow lanes and alleyways that bordered the river and it was far from safe for a young woman to walk alone on a dark night. I began to walk faster, my heart jumping with fright.

The wind was blowing off the river bringing the stench of the oily water and refuse, dumped into the docks by the ships anchored out in the river, into the lanes, which already carried their own smell of decay. The houses here were better than the tenements a few streets away, but nearer to the river several deserted buildings harboured vagrants and rats.

I looked round again, but it was too dark to see anything. The suspicion that someone was following me sent prickles of fear down my spine. Lainie had often warned me about walking alone late at night. She’d told me that Hans always insisted that he walk her back to Farthing Lane after a night out.

When she was with him, Lainie was safe. Hans was a gentle man, but he was a blond giant with feet the size of meat plates and hands to match. One blow from him would knock most men’s heads off their shoulders. I’d met him once and he’d made me laugh with his stories about the days when the Vikings used to raid the English coast.

I wished Hans were here with me now or that my brother Jamie would come whistling down the lane to meet me. There was a man following me, I was certain of it now.

‘Where are you goin’? Bit late for you, ain’t it? Or ’ave you taken to walkin’ the streets for yer livin’?’

The voice was close behind me and made me jump. As I turned, I knew instantly who the voice belonged to and my fear abated slightly.

I lifted my head proudly, meeting that hateful, leering look on his face. Harry Wright had been after me since I was at school. Then he had been a snotty-nosed bully with no shoes and his arse hanging out of his trousers like all the rest of the kids in the lanes. Now he was dressed in a toff’s suit and leather shoes. He had made good and there was only one way to do that round here.

‘Who made it your business? Haven’t they locked you up yet, Harry Wright?’

‘Nah – and they ain’t goin’ ter neither,’ Harry said, eyeing me speculatively. ‘Leavin’ home then? Martha chucked yer out?’ he asked in his broad cockney accent. Harry was a Londoner through and through, but his manner was coarse and unlike most of the friendly people who lived in our lanes.

‘Take yourself off where you’re wanted,’ I retorted angrily.

‘Hoity toighty tonight, ain’t we? Got somewhere to go, ’ave yer? Only I could offer yer a bed fer the night – mine!’

Something in the way he looked at me was beginning to make me uneasy. ‘I’m going home – and I wouldn’t come with you if I wasn’t! I’d rather sleep under the bridge. So just you clear off, Harry Wright! I don’t want anythin’ to do with the likes of you …’

‘You’re too cocky for yer own good, Bridget O’Rourke!’ His eyes narrowed as he looked at me. ‘I bet yer a tart just like that bleedin’ sister of yours. Bin with a bloke down the docks ’ave yer? Yeah, yer a slut just like that Lainie.’

‘My sister isn’t a whore. You’re drunk, that’s what’s the matter with you. Just you leave me alone, Harry Wright! If you try anything I’ll tell Jamie and he’ll give you a thrashing.’

‘Stuck up bitch!’ he snarled and lurched at me, suddenly slamming me into the wall of the nearest house.

I could smell the stink of strong drink on his breath and knew I had guessed right: he was very drunk.

‘You’ve been givin’ it away to anyone who asks. Well, I’m takin’, not askin’. I’ll just ’ave a little taste of what yer’ve bin givin’ away …’

He was so strong and the pressure of his body was holding me pinned to the wall. I screamed once before his hand covered my mouth. Fear whipped through me but I was determined not to give in.

His hand was smothering me, making it difficult to breathe. I bit it as hard as I could and he swore, jerking back in pain and then striking me so hard across the face that I tasted blood in my mouth.

I screamed again, clawing at his face with my nails. My head was reeling and I hardly knew what I did as I struggled desperately to save myself. He was dragging my skirts up, clawing at me down there, where no man had touched me. I gave another cry of fear and pushed hard against him. For a moment I was able to wrench free of him, but he grabbed me and swung me round. I kicked out at him and then he hit me so hard my head went spinning. I gave a moan of pain and he punched me again, sending me crashing to the pavement. I hit my head hard as I fell, and then I knew no more.

‘What’s happening … don’t touch me!’ I screamed as the man bent over me and I stared wildly into the face of a stranger. ‘What are you doing to me? Leave me alone … leave me alone …’ I was almost sobbing now, hysterical. ‘Please leave me alone …’

‘Are you all right, lass?’ The man’s gentle voice was concerned as he knelt over me, helping me to sit up. ‘Someone attacked you. I think he was trying to – well, I believe I got here in time. You hit your head as you fell – does it hurt badly?’ He was touching my head as he spoke, feeling for the wound. ‘You’re bleeding. You must have fallen hard. It’s a wonder the bastard didn’t kill you! You should get your mother to bathe it for you. Where do you live – near here?’

‘Just down the road …’ I took a sobbing breath. I was beginning to remember. It wasn’t this man who had attacked me, in fact he had probably saved me from Harry Wright’s attempt to rape me. Shame swept over me and I hardly dared to look at him. ‘I’m all right … thank you for helping me. Are you sure he didn’t … you know?’

‘He was certainly attempting it,’ the man said. ‘I had been visiting a friend of mine, Fred Pearce, and I came out just as you fell.’ He smiled at me, a flicker of amusement in his greenish-brown eyes. ‘I think you can be sure that he didn’t manage it. He ran off when I yelled at him or I’d have thrashed the bugger for you!’

‘Thank you,’ I said again and blushed. I was overcome with shame as I realized that Harry Wright would have succeeded if it had not been for this stranger. I also wondered what I must look like with my clothes all over the place. ‘He … he frightened me. I was walking home and he followed me …’

‘Do you know him?’

I hesitated, then shook my head. If I told anyone that it was Harry Wright who had attacked me, Jamie would go wild. He would go after him and when he caught him, he would kill him. I didn’t care what happened to Harry Wright, but I couldn’t risk my brother getting into trouble over this.

‘No, I’d never seen him before in my life …’ I gave a cry of distress as I looked down at myself and saw that my dress had been torn and was stained with dirt from the road. ‘Mam will half kill me!’ I said and scrambled to my feet. ‘I’ve got to go …’

‘I’ll come with you,’ he said, steadying me as I nearly lost my balance. ‘Just in case that bastard is still hanging around. Besides, you look as if you need a hand.’

He was being kind but all I wanted to do was get away. My head hurt and I felt sick and dizzy and worst of all I thought that he must be thinking the worst of me – a common tart who’d fallen out with one of her clients.

‘No, thanks all the same. I’ll be all right in a moment. Mam will kill me for sure if she sees me with a feller. You can watch me until I get to me door, if you like?’

‘All right,’ he said and grinned as I dared to look at him again. He had a friendly smile, though he wasn’t a real looker; his hair was short and wiry and a sandy colour in the light of the gas lamp from Farthing Lane, but he had a nice manner and I knew I was lucky that he’d happened along when he did. ‘Cut along home then, lass. You’d best not keep your Mam waiting too long.’

‘Thank you for helping me. I’m Bridget O’Rourke. I don’t know your name …?’

‘I’m Joe Robinson,’ he said. ‘Take care of yourself. I’ll wait here and see as no one tries anything until you get home.’

I sent him an awkward smile and started to run, my heart pounding as my feelings rose up to overcome me. Inside, I was shaking, my mouth dry and my stomach riled. My head was sore where I’d banged it, but it was the feeling of shame that was so unbearable.

I had been attacked and almost raped! Things like that didn’t happen to decent girls, and I was certain Mam would go for me when I got in. She was already in a bad mood and when she saw the state I was in, she would lose her temper.

When I got to my house I turned and waved at Joe Robinson. He was still standing beneath the gaslight and nodded to me as I pointed to the door of my house, but he didn’t make a move. He was going to make sure I got inside safely.

Most of the houses in the area were just two-up two-down with a lean-to scullery at the back and a privy of sorts in the back yard. Ours was an end of terrace and luckily we had an extra small room built on over the back washhouse. It was this extra room that had made it easier for Mam to take in a paying lodger after Sam O’Rourke disappeared. Had it not been for the lodger and the little bit of money the rest of us brought in, she would have had to go out scrubbing floors at one of the factories, like most of the women in the lane, which, knowing Mam, would have made her temper even worse.

As I reached the bottom of the stairs, the front door opened and our lodger looked at me. He was a small, thin man with a pale face and sad eyes, and was just coming back home after visiting a friend. He often stayed out late in the evenings, but Mam never objected. She needed his rent too much to risk losing him. I put a finger to my lips, warning him not to give me away.

‘Don’t let on I’m here, Mr Phillips. I want to get upstairs before Mam sees me.’

‘What happened?’ he asked, looking at me in concern. ‘You’ve got mud on your dress – there’s blood in your hair …’

‘I’ll wash it out when I—’

The door from the kitchen opened and I heard my mother shout, ‘If that’s you, Bridget, you’d better get in here before I lay me hand round your ears. I hope you’re not after bringing that slut of a sister back with you …’

Mam came out into the hallway. She was a big-boned woman with a mottled complexion and dark hair streaked with grey dragged back into a bun at the nape of her neck. Her mouth was set in a grim line, her eyes cold with anger as she stared at me.

‘Bridget has had an accident,’ John Phillips said, standing in front of me as though prepared to defend me from her temper. He gave me a warning look and I took my cue from him.

‘I slipped and fell in the mud in the lane, Mam – must have banged my head. Leastwise, it’s bleeding.’

‘Perhaps I should take a look at it,’ Mr Phillips offered. ‘Come into the kitchen, Bridget.’

I followed as he went through the parlour to the back kitchen. The parlour itself was furnished better than most in the lane, with a half-decent sofa and two chairs, a table with ends that folded down, four chairs to match it, an oak dresser with a mirror and shelves for a few bits and pieces of china and glass fairings.

Mam lunged at me as we passed, giving me a slap on the ear that nearly sent me flying. I gave a yelp of pain and the lodger turned to look at her reprovingly.

‘Mrs O’Rourke! Surely such violence isn’t necessary? The girl has already had a nasty accident.’

‘You keep your nose out of it,’ Mam retorted, forgetting to be polite to him in her temper. ‘She’s a slut and needs to be taught a lesson or she’ll bring shame on us for sure. You ought to watch out, my girl. If your father were here he’d take his belt to you.’

‘I’ve done nothing wrong, Mam. I had to go after Lainie, you know I did. I tried to get her to come home, but she wouldn’t.’

Mam hit me again, making my head rock.

‘That’s enough, Mrs O’Rourke. I’ve told you before the girls will leave home if you continue to hit them like that. If you are trying to drive her on to the streets you are making an excellent job of it.’

‘He’s right, Mam. Lainie’s gone and she says she won’t come back – and if it weren’t for our Tommy I’d go with her.’

‘And where will you be going? No decent woman will take you into her home at this hour of the night. It’s after pickin’ up a man you’ll be. You’ll bide here and do as I tell you or you’ll feel the back of my hand and harder than you’ve felt it before, my girl.’

‘Bridie Macpherson will have me,’ I said, my voice rising with anger now. ‘She’s always looking for girls to help out in that hotel of hers. That’s where Lainie’s gone and if you hit me again I’ll go with her!’

My threat was not an idle one. Bridie Macpherson’s small but scrupulously clean hotel was only three streets away from Farthing Lane. It was patronized by the captains and first officers who preferred somewhere better to stay than the Seamen’s Mission, or the special hostel for foreign sailors. Jamie had told us the mission had been set up some forty years earlier, to protect the Lascars from being preyed on by river thieves. Before the hostels were built, they had often ended up penniless after being cheated or robbed of their pay by the rogues who lived in the dirty alleyways close to the docks.

Until now, both Lainie and I had worked in the brewery, which was just across the river from St Katherine’s.

St Katherine’s Dock was originally built on twenty-three acres between the Tower of London and the London Docks, making it conveniently near the city. The site had been home to more than a thousand families, a brewery and at one time St Katherine’s hospital, which had always been owned by royalty. Its land had been cleared though, despite the hardship it caused, and the docks given a grand opening in 1828. Commodities such as tallow, rubber, sugar and tea had all been stored in the sturdy yellow-brick warehouses some six storeys high, but for some reason the docks were not a financial success and had become part of the London Docks in 1864. However, to the people of the lanes, especially those that worked there, they would always be known as St Katherine’s.

There had been breweries near the river since the time of Queen Elizabeth when they supplied beer to the soldiers in the Low Countries, but Dawson’s, where Lainie and I worked, had only been built in the last five years, and produced ginger beer as well as three kinds of ale.

Lainie worked in the brewing side, but I had recently been taken on in the office. Before that, I’d had occasional work down the market, helping Maisie Collins with her flower stall, and giving Mam a hand with work in the house. Being in the office at the brewery was much better. At the moment I made the tea, tidied up and ran errands for three shillings a week, but I was learning to help keep the ledgers because I could copy letters in a neat hand and I was quick at figures. Mr Dawson had promised me another two shillings a week soon.

I brought my thoughts back to the present as Mam started on at me again. ‘Walk out of this house and you don’t come back! I’ll not have a slut livin’ under my roof. You’ll mend your ways or I’ll see the back of you.’

‘Now that’s foolish talk,’ Mr Phillips said. ‘Bridget has always been a good girl, Mrs O’Rourke. You would find it hard to manage the house without her.’

Mam’s face screwed up and I thought she was about to explode, but although she opened her mouth to tell him to mind his own business, she shut it again.

‘Get to bed before I change me mind,’ she said and scowled at me. ‘You can think yourself lucky that Mr Phillips spoke up for you. If I had my way I’d give you a good thrashing!’

I turned and fled towards the stairs, not stopping until I was in my own room.

Tommy sat up and looked at me. ‘Where’s our Lainie?’ he asked sleepily, clenched fists rubbing at his eyes.

‘She’s gone out to see a friend,’ I said and hushed him with a kiss on the top of his head. He smelled so good after I’d had him in the bath and scrubbed his hair with strong soap – the same as I used to scrub the house. Tommy hated it, but he hated the nits worse and I made sure he went to bed clean – even if he came back filthy every night. ‘Go back to sleep, darlin’.’

I held my brother closer, feeling protective towards him as I felt how thin and frail he was. There was no way I could ever walk out on him because he wouldn’t stand a chance left alone with Mam.

‘What happened to you, Bridget?’ Tommy touched my cheek and found a smear of blood. ‘Are you hurt?’ He looked anxious, as if afraid that I might suddenly disappear too.

I glanced down at myself, repressing the shiver that ran through me as his words reminded me of what had almost happened. Rape was something all decent girls lived in fear of, which was why we took notice of our mothers and didn’t go walking alone at night.

‘It’s nothing, darlin’ – just a tumble on some mud in the lane. You know how dirty it gets at this time of year. It was probably a bit icy, it’s freezin’ out so it is. I fell and banged my head. It knocked me out for a moment, but I’m all right.’

‘Let me look.’ Tommy scrambled out of bed.

‘Can you see anything?’

‘It’s cut open. Shall I bathe it for you, our Bridget?’

‘Will you, darlin’?’ I caught his hand as I saw the troubled look in his eyes. ‘Don’t look so worried, it’s nothing much. I might have a bit of a headache, but I’m all right.’

I poured some water into the earthenware bowl from the washstand and sat on the bed for Tommy to bathe the cut on my head. He was as careful as he could be, but it stung and I winced a couple of times.

‘I’m sorry, Bridget.’

‘It’s all right, Tommy. Let’s get to bed, darlin’, or you’ll be too tired for school in the morning.’

We got into bed together, me holding him as he settled to sleep. I wished I could sleep as easily and I fought desperately to stop myself thinking about Harry Wright and what he had almost done to me. I knew Jamie would have gone after him if I’d told him, and he had such a temper there was no telling what he might do.

It was quiet down in the kitchen now. Mam would be having a drop of the good stuff with her lodger before they came up – to separate rooms. Mam had made it plain to her lodger there was to be no funny stuff. She slept with Tommy as a rule and Mr Phillips had the room that had been Jamie’s and Tommy’s before Da disappeared. If Jamie came home at all, he would sleep on the couch, but most nights he stayed with a friend, leastwise that’s what he told Mam. I had heard stories that would make Martha O’Rourke’s hair curl, but I kept them to myself. There was enough trouble in the house as it was without stirring up more. Still, now that Lainie had gone perhaps things would settle down for a while …

As I lay sleepless beside my brother, I wondered what had happened to turn Martha O’Rourke into the hard cold woman she was. Had it happened when her husband had killed a man in a violent fight on the docks?

I knew Mam’s life had been hard these past years, but that didn’t account for her violent rages. Some of our neighbours had it even harder than us – though we were going to miss Lainie’s money. But there was real hatred in Martha O’Rourke.

Lainie was right when she said that Mam had always hated her. She’d never been as bad with me as she was with Lainie but that might change now I was the only daughter at home.

I shivered and snuggled into the warmth of my sleeping brother’s body. There wasn’t much point in worrying over something I couldn’t change. I’d had a lucky escape thanks to Joe Robinson and I would take good care not to give Harry Wright another chance to attack me.

Sighing, I closed my eyes and willed myself to sleep. It would soon be morning and I had to be up early.

Two (#ua6a5f0f3-8d21-59c9-8916-5173fed1464e)

Mam looked heavy-eyed when she came down the next morning. She had slept late and I’d already scrubbed the front step and given Tommy his slice of bread and dripping. He hadn’t wanted it, complaining that it made him feel sick, but I’d coaxed him into eating it.

‘Have you done them stairs yet, you lazy little cat? You can tell that boss o’ yours this mornin’ that I want you setting on in the works. You’ll earn more there than in that fancy office.’

‘You know he won’t give me Lainie’s job. She was on the ales and I’m too young. He gave me my job because I can’t start in the brewery proper until I’m eighteen. It’s his policy and he won’t change it for me.’

‘His policy is it?’ She sneered at me, an ugly expression on her face. ‘What fancy talk is that? Don’t you put on your posh airs with me, miss! You tell him what I said. If he won’t pay you at least four shillings a week you can go scrubbin’ floors.’

I didn’t want to work on the ales or scrub floors, but knew better than to answer my mother back when she was in this mood.

‘Get your brother ready first,’ she said. ‘I’m off down the market before the best stuff is gone.’ The front door slammed as she went out.

‘What do you want to take for your dinner at school, darlin’?’

‘Nothing. I ain’t hungry.’ Tommy coughed, a harsh sound that made me look at him anxiously

‘You must eat something,’ I urged. He was so thin, a puff of wind might blow him away! ‘Bread and jam do, love?’ He nodded unhappily. ‘Take it with you and promise me you’ll eat it and I’ll get you an egg for your tea.’

‘A whole egg just for me?’ Tommy brightened a little. ‘With bread and butter and not dripping?’

‘I get my wages today. Mr Dawson promised me a rise. I’ll keep a few pence back for us. Mam won’t know any different. Just eat your dinner in the playground like a good boy. Then I promise I’ll get that egg for your tea.’

‘Mam will hit you if she finds out you didn’t give her all your wages.’

‘If she can catch me.’ I was relieved to see a smile poke through at last. I loved this brother of mine more than anything or anyone in the whole world, and sometimes I was desperately afraid I was going to lose him. ‘You and me won’t tell her, will we? I’ll let on Fred Pearce gave me the eggs.’

‘Mam says he’s a dirty old man.’

Fred lived at the end of the lane in a house that looked as if the windows hadn’t been washed since he’d been there, and people often avoided him when he was trundling his little cart up the street, but I liked him and we often stopped for a chat when we met.

‘He doesn’t wash much, but I don’t suppose he can afford the soap,’ I said, deliberately ignoring what I knew was implied by Mam’s harsh words.

‘I don’t think that’s what Mam meant. She pulled a funny face the way she does, and said he’d have your knickers off you, if you don’t watch it.’

‘Mam says a lot of daft things – but don’t tell her I said so. Fred Pearce isn’t like that. He’s kind and he just likes to talk to me, that’s all. He’s never tried to touch me – not like some of the blokes round here.’

Tommy stared at me. ‘Does Mr Phillips try to touch you, our Bridget?’

‘No, o’ course not! I never heard the like. He’s a decent bloke. I like him. I just hope he doesn’t leave us. Mam would lose her rag. What made you ask me that, Tommy?’

‘Nothing. I just wondered if he was one of them what tried it on with you.’

‘No, he isn’t. Mr Ryan from next door tries it on when he’s drunk – pinchin’ my bum that’s all. He’d better not let Maggie see or she’ll go for him with the rolling pin. Do you remember in the summer when she chased him all the way down the lane?’

Tommy nodded. He had lost interest in the conversation and said he was going out the back to the lawy. I reminded him to wash his hands before he went to school. He nodded and promptly forgot my instructions as he shot through the kitchen without so much as a good morning to the lodger.

Mr Phillips was just preparing to leave for the day. I thought how smart he looked in his dark overcoat and bowler hat. He worked as an accountant in a big import firm on the docks and earned more in a week than I could in months. I knew how important it was that he continued to live with us and pay his rent of ten shillings a week.

‘Was your breakfast satisfactory, Mr Phillips?

‘The bacon you cooked was very nice.’

‘Have a good day at work, sir.’

‘I shall have a busy day,’ he replied. ‘I’m afraid no days are particularly good ones for me. Good morning, Bridget.’

I stared after him as he went out. I hadn’t thought of him as being a miserable sort of man, though he was a bit odd sometimes.

However, I certainly hadn’t got time to puzzle over it now. I’d better scrub the stairs and get off to the brewery or I would be late for work.

As I crossed the cobbled yard to the brewery office. I heard a shrill wolf whistle. Men were loading heavy barrels on to the wagons ready to deliver the beer to pubs all over the East End, and the smell of the horses mixed with the sharp odour from the brewery sheds. I didn’t bother to turn my head at the whistle because I knew who was responsible. It was that Ernie Cole. The cheeky devil! He drove a wagon and two lovely great shire horses for Mr Dawson – and thought he owned the world.

Well, he might be a tall strong lad with a fine pair of shoulders, but I wasn’t about to encourage his cheek. I wouldn’t give him the satisfaction of showing I’d heard, so I stuck my head in the air and walked on by.

I supposed I liked him in a way, but I never gave him the chance to get too close. I rather enjoyed putting him down and seeing his face fall. He was too sure of himself for his own good!

He was after walking out with me, I knew, but I wasn’t interested in anything like that. Not yet anyway. I was seventeen and a few months – too young for courting. Besides, I wanted to get on a bit in my job if I could and Mr Dawson thought a lot of me.

Mrs Dawson had told me that only the previous day: ‘My husband thinks you might take my place as his secretary one day, Bridget. He would like me to take things a little easier, stay at home and meet my friends.’

‘Take your place?’ I had stared at her in surprise. ‘But I could never do all the things you do, Mrs Dawson.’ I had never dreamed of such a thing until she put the idea into my head, but I had liked it at once.

‘Why not? You’re bright, careful and industrious. I think it entirely possible that you could learn to do everything I do.’

‘But how?’

‘Well, I can teach you a lot of it,’ Edith Dawson replied. ‘But my husband feels it might be worth paying for you to have special tuition. There are places where you can learn in the evenings after work. You might even learn to use one of those machines – typewriters I think they are called.’

I hadn’t known how to keep my joy to myself as I’d hurried home the previous evening. I had hoped to tell Lainie my good news when she came to bed, but the row had put it out of my head.

Stephen Dawson was waiting for me as I entered the office. He grinned at me. ‘Pop the kettle on, Miss O’Rourke,’ he said. He called me that sometimes just to tease me. ‘We’ll have a cuppa before we start, shall we?’

‘Oh, yes, please,’ I said. ‘I didn’t get one this morning and I’m proper parched, so I am.’ I glanced round the small office. ‘Mrs Dawson not in the mornin’?’

‘No – she had some shopping up town,’ he said. ‘Wants to buy herself some fripperies I dare say. Our daughter is getting wed after Christmas. We heard the news last night.’

‘That’s grand news,’ I said. ‘Give Miss Jane my love and tell her I hope she will be very happy. Lainie might be getting wed soon. She told me last night that her feller had asked her.’

‘That’s good,’ he said. ‘Though I’ll be sorry to lose your sister when she leaves. She’s been a good worker.’

‘She might have to leave before the wedding,’ I said as I remembered she’d told me she was going to Mrs Macpherson’s. ‘You haven’t heard from her the mornin’?’

‘No – not yet, though she may have spoken to the foreman.’ He glanced through the window, which had rivulets of water trickling down the glass because of the cold outside. ‘Ah, I just need to speak to Ernie before he leaves.’

‘You’ll catch him if you hurry.’

I went through to the little kitchen at the back of the office. I filled a kettle from the tap over a deep stone sink, then lit the gas stove and put the water on to boil. I set the cups out on a tray – blue and white china they were and not one of them chipped – then poured milk from the can into a matching jug so that I wouldn’t spill it as I served the tea. Mrs Dawson was most particular. She liked things nice and hated the smell of stale milk on her pretty tray cloths.

I picked up a thickly padded holder as the kettle began to whistle. The copper handle got hot and I didn’t want to burn my fingers. I had a lot of copying to do that morning.

‘Bridget …’ I turned as Mr Dawson called to me from the doorway. ‘Leave that for a moment. I want to talk to you.’

My heart caught with fright. ‘Have I done something wrong, sir?’

He shook his head but looked displeased. ‘You’ve done nothing, Bridget … but your brother, Jamie, is in trouble yet again.’

‘What has he done?’

‘Apparently he was in a fight last night. The police want someone to go down to the station and sign for him. He’s in a bit of a state and they won’t let him go unless a member of his family takes him home.’

‘What do you mean in a state – is he hurt?’

‘I think he may have been hurt during the arrest. The police couldn’t find Mrs O’Rourke so they sent a young constable here. I really can’t have this sort of thing, Bridget. This is a respectable business.’

‘I’m sorry,’ I said as I reached for my shawl. ‘I’ll come back as soon as I can, sir – and I’ll make up the time later.’

Mr Dawson nodded, but he was still frowning. This was the second time in as many months that the police had sent for someone to fetch Jamie, and he wasn’t pleased that his brewery should be associated with a known troublemaker.

I was anxious as I left the brewery office and hurried across the yard, ignoring Ernie Cole as he called out to me. He’d asked if I wanted a lift, which meant he knew where I was going. Everyone would know! I felt humiliated as I left the yard and set off in the direction of the police station, some ten minutes’ walk away.

Jamie was such a fool to himself when the drink was in him. Most of the time he was a good-natured, cheerful and generous man. There was violence in Jamie; it simmered beneath the surface, erupting every now and then in uncontrollable anger. Instead of thinking, he went in with his fists just the way Da had.

Hearing the rattle of a wagon on cobbles behind me, I glanced back and saw that Ernie had almost caught me up. He slowed the horses as he drew level.

‘Jump up, Bridget. You’ll get there all the quicker and it’s on my way, lass.’

‘Thank you, but I would rather walk.’

‘You’re a stubborn girl, Bridget O’Rourke. You’ll be quicker if you ride.’

‘No, I shan’t. I’m going to take the short cut by the river.’

‘It’s a rough area down there. Let me take you.’ He gave a sigh of exasperation. ‘Ah, Bridget, don’t be daft, lass …’

Ignoring him, I ran down a side alley towards the river. It was one of the worst areas in this part of the docks and I would normally have avoided it, but I had to get away from Ernie’s pestering. After the incident of the previous night, when Harry Wright had attacked me, I was less trusting than ever of men who wouldn’t take no for an answer.

The river looked dirty and oily where the waste from the ships lay floating in the shallows, and it was cold enough to freeze over. There were vagrants by the dilapidated warehouses on the banks, some of them hunched by a fire burning in an old metal pot, others drinking and lying on sacks.

I felt their eyes on me as I hurried by and a couple of them called out to me, but they were harmless enough, too beaten down by life to bother. It was the cocky ones like Harry Wright you had to be careful of – and Ernie Cole.

As I turned the corner towards the police station, I saw a young woman loitering on the pavement and recognized her at once. Her name was Rosie Brown and she was what Mam would call a whore. I’d heard that she had been seen hanging around the pubs with Jamie a few times.

As soon as she saw me she came to meet me and said, ‘Have you come for Jamie?’ She was a pretty girl, though her fair hair looked as if it needed a good wash and her clothes weren’t as clean as they might be. ‘They won’t let me in to see him, the rotten buggers.’

‘How is he, Rosie? What happened last night?’

‘Jamie got paid three shillin’s,’ she said and grinned wryly. ‘It was the first work he’d had in days and he spent all the money on drink. There was an argument with some bloke he knows … turned into a bleedin’ riot! They were smashin’ the furniture when the bleedin’ coppers arrived.’

‘Was Jamie hurt?’

‘Someone hit ’im from behind. I think it were a copper or it might ’ave bin one of the sailors he were fightin’. Your Jamie’s a proper bruiser, Bridget. ’E ought ter do it fer a livin’. Layin’ ’em out left and right he were, then someone cracked a bottle over his head, and the next thing the bleedin’ coppers were all over the place and one of ’em knocked Jamie down, even though he were already dazed. They carted ’im orf and I ain’t seen ’im since.’

‘They ought to be ashamed of themselves.’

‘I was worried about ’im,’ Rosie said looking at me oddly. ‘But I shan’t hang around now that you’re ’ere. Jamie will be all right wiv you, Bridget.’

‘I’m not too sure about that,’ I said ruefully. ‘Mam will go wild if there’s no money for her and if she finds out he spent his money on drink and spent the night in the cells, she’ll likely throw him out.’

‘She’s a hard woman, your ma.’ Rosie pulled a face. ‘Jamie knows he can come to me if he’s looking for a place to stay. You tell him that, Bridget.’

‘That’s kind of you,’ I said, ‘but you can’t keep him, Rosie. He needs to work – he ought to work. There’s nothing wrong with him, he’s strong as a bull.’

‘It ain’t easy to find work round ’ere. You don’t know what it’s like for ’im, Bridget, the men standin’ in line, waitin’ to be set on. If you’ve been in trouble you get the worse jobs. Jamie was unloading bones for the soap factory – dirty, stinking and crawling with maggots, ’e said they was. Had to wash the taste out of ’is mouth. You can’t blame ’im, Bridget.’

‘No, I don’t suppose so, but he’s his own worst enemy, Rosie.’

‘Jamie’s Jamie,’ she said and smiled, her eyes warm with affection. ‘Don’t nag ’im, luv. He’s down enough as it is.’

I watched her walk away. I was well aware that it was hard for my brother having to wait in line to be given a job. Until a year previously he’d been in regular work, but some trouble on the docks had led to his being dismissed and since then he’d had to take whatever he could get.

As I entered the station the sergeant behind the desk gave me a sour look. ‘Come for that brother of yours, I suppose?’

‘Yes, please, Sergeant Jones. I am sorry he caused you some bother.’

‘Not your fault,’ Bill Jones replied, his frown lifting at the tone of my voice. ‘He’s a fool to himself. He’s got a good brain, he should make some use of it.’

‘It’s only when the drink is in him, Sergeant Jones.’

‘I know that. If I didn’t I would have had him on a charge before this. As it is, the landlord didn’t want to push charges. He’s used to his customers causing trouble, and it wasn’t him that called us in. Take Jamie home and see if you can make him see sense, will you, Miss O’Rourke? He’s getting a bad name for himself. Tell him that it’s only a matter of time before he’ll be in serious trouble if he goes on this way. He might listen to you.’

‘Yes, perhaps,’ I said and smiled at him. ‘And thank you for not sending him up before the magistrate.’

‘One of these days he’ll go too far … He’s got a sore head and feels a bit sorry for himself. You’d best take him home and give him a cup of tea, miss.’

One of the younger policemen had been sent to fetch Jamie from the cells. He came in through a side door, his jacket slung carelessly over his shoulder and an air of defiance about him, but his expression changed as he saw me.

‘So they sent for you,’ he said, and just for a moment a flicker of shame showed in his eyes. ‘There was no need. I’m sober now.’

‘You were injured last night,’ Sergeant Jones said and glared at him. ‘Go home with your sister and think about your life, lad. You’re wasting your time with all this drinking and brawling.’

Jamie scowled but made no answer, merely jerking his head at me as he left the station.

‘Goodbye, Sergeant Jones,’ I said. ‘Thank you.’

‘Why did you thank the bastard?’ Jamie growled as we walked along the street. ‘It was probably him that hit me.’

‘You know it wasn’t, Jamie. Rosie Brown said you were hit by one of them varmints you were fighting with, then one of the coppers knocked you down, but you were half out anyway.’ I looked at him anxiously. ‘Does your head still hurt bad?’ My own was feeling sore after the incident the previous night, but I wasn’t going to tell him that. He was in enough trouble already.

‘It aches a bit. The police surgeon patched me up earlier, said I should go to bed for a couple of days when I got home. But I’m off down the docks to see if I can get a few hours’ work.’

‘Surely it doesn’t matter for one day? Have a rest, Jamie.’

‘I can’t afford to, Bridget. I’ve no money for Mam …’

‘You’ll likely earn some another day.’

‘And when’s that likely to be? I can’t stand it, Bridget. Sometimes I think I’ll run away – go to America like Da did.’

‘Do you think that’s where he is? Mam said he was drowned, but Lainie said she was lyin’.’

‘Well, it was what we told the coppers,’ Jamie said. ‘Maybe Mam believes it now, but I reckon he got away. He’d spoken of going back to the old country and from there to America. Ah, it’s a grand life there so they say – the streets are paved with gold, so they are.’

‘You don’t really believe that?’

Jamie grinned, his arrogant manner back in place. ‘No, but there’s more opportunity for a man to get on. I’m sick of bowing and scraping just to get a day’s work …’

‘Why don’t you try something else, Jamie? Something better than casual work on the docks. Why let them humiliate you? Show them you’re better than that!’

‘There’s nothing else on offer round here, Bridget. I’ve been everywhere and none of them would give me a chance, even if they wanted a man—’

‘Then go further afield … don’t just give up, Jamie. Try to make some sort of a life for yourself.’

‘It might mean me being away for weeks – even months. There would be no money until I got a chance to come back for a visit.’

‘We could manage. And if you went to America we might never see you again. At least this way you could come home now and again.’

‘Would you miss me, darlin’?’

‘You know I would, Jamie, but you’re wasting your time around here. I’d like to see you settled …’

‘I’ll think about it,’ he said and then frowned. ‘Why don’t you get back to work, Bridget? Mr Dawson won’t be too pleased as it is, I’ll wager?’

‘No, he wasn’t,’ I admitted and studied his face. ‘Are you sure you’re all right? Sergeant Jones said I should make sure you got home safely.’

‘I’ll see Mam, then I’ll be off. Make inquiries about work elsewhere. No doubt they’ll be fallin’ over themselves for me services …’ He grinned at me, his old confidence coming through. ‘If you don’t see me for a while you’ll know I’ve taken your advice.’

‘You won’t go to America?’

Jamie hesitated, then shook his head. ‘No – not yet, anyway. I promise I’ll tell you if I decide to go and I’ll see you’ve got a bit o’ money in your pocket. Get off then before Mr Dawson gives you up for lost.’

I ran all the way back to the brewery, terrified that I would lose my job. It was going to be hard enough without Lainie’s money, and if Jamie didn’t bring anything in either Mam would create, but I was glad I’d told him he ought to move on. Being out of work so often was making him bitter and I wanted the old, carefree Jamie back – even if it meant that I had to bear the brunt of Ma’s temper.

Mr Dawson didn’t dismiss me that day. Instead, he gave me a rise of two shillings and sixpence. It was more than he’d promised and I thought he wanted to make up for being sharp with me earlier.

I decided not to give this first rise to Mam and I bought some eggs at the shop on the way home and a tiny corner of butter for Tommy. I hesitated over some raspberry drops, then bought a small twist for him as a treat.

‘Put these in your pocket and don’t let Mam find them,’ I told him as I gave him the sweets. ‘It’s our secret.’

‘If she finds them I’ll tell her I won them off a lad at school.’

Mam was in a bad temper when she came in from gossiping with Maggie Ryan. She looked at the eggs I’d cooked for our tea and then glared at me.

‘I suppose I know where they came from!’ she muttered and banged the pots on the stove. ‘You just watch yourself with that Fred Pearce, my girl. He’s up to no good – giving you things …’

‘It’s only a few eggs, Mam. I gave Tommy two because he’s growing, but I saved one for you. Shall I boil it or fry it for you?’

‘Neither. I’ll put it in the pudding for Mr Phillips’ dinner.’ Her gaze narrowed menacingly as she looked me over. ‘If I find out you’ve been up to something …’

‘I wouldn’t, Mam. You know I wouldn’t do anything to shame you.’

‘You’ll rue the day you were born if I catch you hanging about with men.’ She cuffed my ear in passing as I rose to gather the tea things. ‘Did you speak to Mr Dawson about putting you on the ales?’

‘No, Mam …’ I ducked as she came at me again. ‘Don’t hit me! Mr Dawson is going to give me a rise next week – and Mrs Dawson is going to teach me to be a secretary.’

‘You watch your language, my girl!’ She stared at me suspiciously. ‘What’s that supposed to mean then? I know his sort, all hands. If you’re lettin’ him do things to you …’

‘No, Mam! It means I’m going to keep the accounts and learn to use one of those typing machines. Mrs Dawson says I’ll earn a lot more once I’ve learned than I will on the ales.’

‘How much more?’

‘Perhaps as much as fifteen shillings a week when I’m trained.’

Her mouth twisted in disbelief. ‘She’s having you on, Bridget. They’ll never pay you that! Unless he’s interfering with you? Bloody men, they never know when to keep their hands to themselves.’

‘Of course he isn’t doing anything – Mr Dawson isn’t like that, you know he isn’t. And I wouldn’t let him if he tried. I shan’t get that sort of money for a long time, but the more I learn the more they will pay me. Please don’t make me leave, Mam. I like it there and Mr Dawson said he wouldn’t put me on the ales yet anyway. I should have to go scrubbin’ and then there would be no chance of anything better.’

‘We’ll be needing more money with that whore of a sister of yours leaving us in the lurch, and Jamie bringing home next to nothing.’

‘Jamie hasn’t been able to find regular work. It isn’t his fault … the bosses won’t give him a proper job.’

‘And whose fault is that? He’s a troublemaker like Sam. Always fighting! It was the worst day of my life when I met Sam O’Rourke. I had a good place in service until he …’ She broke off and scowled. ‘If you’re lying to me about the money I’ll make you sorry.’

‘You’ll see, Mam. I’ll bring you extra money next week.’

‘See you do,’ she muttered, clipping my ear again. ‘That’s nothing to what you’ll get if I catch you out, miss. Now you can go up the Feathers and get me a jar of whisky.’ She took half a crown from the shelf and slapped it down on the table in front of me. ‘Come straight back and don’t lose the change.’

I was resentful as I made my way towards the pub at the end of the lane. It was still early in the evening and there were plenty of people about. Mr Ryan from next door was on his way home from work.

Tilly Cullen waved as she scurried home to get her husband’s tea. She was the laziest woman in the street, spending most of her time gossiping with her friend. Maggie Ryan had told me that Tilly’s house was a tip most of the time.

‘I don’t know how she gets away with it,’ Maggie had said. ‘My Mick would take his belt to me if I let things go the way she does.’

When I came out of the Feathers, I glanced round uneasily, half fearing that Harry Wright might be hanging around waiting to grab me again, but there was no sign of him. I breathed a sigh of relief and did my best to put the incident out of my mind; it wasn’t likely that I would see Harry for a while. He couldn’t be sure that I hadn’t told Jamie, and he would be aware of my brother’s reputation.

Even so, I walked home quickly. Ernie Cole and a group of other young men and women were walking up the lane towards me, obviously heading for the pub and a night out. Ernie waved to me but I ignored him as always, hurrying inside the house.

Mam snatched the whisky jar from me as soon as I went into the kitchen. I gave her the change, which she counted before putting it on the mantelpiece.

‘Haven’t you got anything better to do with yourself, Bridget O’Rourke? It’s time you fetched Tommy to bed, and then you can do the ironing. Out of my way, girl! I’ve got to see to Mr Phillips’ dinner.’

I turned away, feeling the resentment bite deep. What did Mam do with herself all day? She washed the clothes and sheets twice a week because of the lodger, but I did most of the other work.

For a few minutes rebellion flared inside me. The future seemed bleak despite the promise of a better job, and I wished I could just walk out the way Lainie had.

Thinking about my sister cheered me up a little. Maybe I could find a way to take Tommy to visit her that weekend. I still had a few pennies left in my pocket. Maisie would sell me a nice bunch of flowers for that.

I called Tommy in from the yard, where he had been playing with Billy Ryan and some of the other lads. He was the reason I stayed here. As long as I had him to take care of, I would put up with Mam and her temper.

Three (#ua6a5f0f3-8d21-59c9-8916-5173fed1464e)

‘Harry Wright did what to you?’ Lainie stared at me in horror. ‘Did he hurt you, Bridget? He didn’t manage to … well, you know …?’

‘Careful,’ I warned, ‘I don’t want Tommy to hear. If he were to tell Jamie – you know what would happen. I don’t want Jamie in more trouble.’ I glanced at Tommy, who was playing with a cat in Bridie Macpherson’s back yard and eating an apple.

‘He would go after that bastard for sure,’ Lainie said. ‘He deserves a thrashing for what he did to you.’

‘But then Jamie would go to prison.’

‘Let that devil wait until I see him,’ she said. ‘I’ll have a thing or two to say to him. You should have told Sergeant Jones. He would have sorted him out for you.’

‘I couldn’t. It’s too embarrassing. Don’t let’s talk about it any more. I’m all right. My head was sore for a bit and it gave me a nasty feeling inside, but I’m over it now.’

‘Nothing bothers you for long, does it? If I’d been more like you maybe I wouldn’t have quarrelled with Mam so much.’

‘It was Mam’s fault not yours. Her temper is getting worse all the time.’

‘That’s the drink,’ Lainie said. ‘She guzzles too much of that rot gut stuff from the Feathers. It’s not like good whisky, Bridget. I’m after thinkin’ it’s turned her mind.’

‘You don’t mean that?’

‘It seems that way to me. She wasn’t this bad a few years back, but it’s been coming on for a while … since Da left.’

‘That made things hard for her, Lainie.’

‘She was better off than a good many. I’ve tried to work it out, but I’ve never understood why she’s so hard … so bitter.’

Mrs Macpherson had come into the yard to tell us there was a pot of tea and cakes waiting. ‘You can have your tea with your sister, Lainie,’ she said. ‘Then I need you in the kitchen. We’ve an extra guest this evening and he wants his dinner at six.’

‘I should be going soon anyway,’ I said. ‘It was good of you to let Lainie have time off to talk to us, Mrs Macpherson.’

People might say she was hard on her girls, but I thought Lainie was lucky. Mam would have me at it night and day if she could, and some nights I was so tired I could hardly wait to get my things off and go to bed.

‘Lainie’s a good worker,’ she said. ‘I was pleased to get her, but don’t expect to visit every week. Once a month will suit me, and Lainie gets a half-day every other week.’

We followed Mrs Macpherson into the hotel. She’d set a tray in the little back parlour and she’d been generous with slices of seed cake and treacle tart. Tommy fell on them with delight, wolfing down two slices of each.

‘Don’t make yourself sick,’ I warned, but Lainie smiled and ruffled his hair.

‘Let him enjoy himself, Bridget. Bridie won’t expect any left over. She’s always generous with food, even if she does drive us girls hard.’

‘Is it all right here, Lainie?’

‘It’s better than being at home with Mam after me all the time. And I shall go with Hans as soon as he gets back.’

‘When will that be, Lainie?’

‘He said it would be a short voyage this time. He always stays here and he’ll be surprised to find me waiting for him.’

‘I hope he comes soon,’ I said and felt an odd chill that I couldn’t explain at the back of my neck. ‘I want you to be happy.’

‘Don’t worry about me …’ She paused, wrinkling her nose. ‘I’m going to talk to Hans about you and Tommy. When we’re settled – I might send for you both.’

‘Do you mean it? Would Hans let us? You don’t want to spoil things for yourself.’

‘You don’t know Hans if you think that,’ she said confidently. ‘He’s so good to me, Bridget. I think he would give me the moon if he could …’

Mrs Macpherson was looking at us from the doorway. I jumped up and caught Tommy’s hand. ‘Thank you for the lovely tea,’ I said. ‘We’ll be going now.’

She nodded her approval, ruffling Tommy’s hair as we passed by. ‘You’ve got good manners, Bridget,’ she said. ‘If you ever want to leave home I could find work for you here.’

‘Thank you. It’s generous you are, Mrs Macpherson. I shan’t forget.’

It was cold outside and I shivered, pulling my shawl tighter around me as we passed a gentleman who was about to enter the hotel. He was carrying a large bunch of crimson chrysanthemums and something about his manner made me look at him and smile.

‘Someone is going to be lucky,’ I said. ‘Aren’t they lovely – really big heads and that sort always smells so good.’

He glanced at me, surprised at first and then he replied with an answering smile, ‘They are rather special, aren’t they? I bought them for a friend.’

‘Did you get them from Maisie?’ I asked, chattering on because he seemed such a pleasant man. His clothes told me he didn’t belong in the area; they were too smart – too expensive. I thought he must be gentry, perhaps a country gentleman in town on business and calling on a friend. ‘She had some on her stall yesterday.’

‘What an observant young lady you are,’ he said. ‘Yes, I bought them from Maisie. I usually visit her whenever I’m this way.’

‘On business I suppose?’

I wondered at myself even as I spoke. Normally, I wouldn’t have asked a stranger questions, but I was curious about him. He didn’t look as if he were one of Mrs Macpherson’s regular guests, but he was clearly about to go inside.

‘Business and pleasure,’ he replied looking amused. ‘Bridie is a friend of mine – the flowers are for her. I visit her now and then … When I’m here on business, as you said.’

‘Oh …’ I flushed as I realized that he was laughing at me. ‘I shouldn’t have asked …’

‘I don’t mind.’ He offered me his hand. ‘I am Philip Maitland – and who do I have the honour of addressing?’

‘Bridget O’Rourke,’ I said, suddenly shy as I felt the warm clasp of his hand about mine. ‘My sister Lainie is working for Mrs Macpherson and Tommy and me have been visiting – and I talk too much!’

‘Ah – Miss Bridget O’Rourke,’ he said and nodded. ‘So that’s the source of that delightful accent … just a trace of Irish and very attractive if I may be permitted to say so. Perhaps we shall meet again one day?’

‘Yes, perhaps.’ I was beginning to feel embarrassed. ‘I have to go now.’

‘In that case I must not delay you.’

‘Did you know him?’ Tommy asked when we were out of earshot. ‘Mam will belt you if she knows you were makin’ up to a toff, Bridget.’

‘He was a gentleman. And Mam won’t know, because I shan’t tell her – and you mustn’t either.’

‘You know I wouldn’t tell on you,’ Tommy said giving me a reproachful look. ‘But Tilly Cullen went past while you were laughin’ with him, and you know what she’s like.’

‘Well, we’ll just have to hope she doesn’t tell Mam. Besides, we weren’t doing anything wrong – just talking.’

But I crossed my fingers and hoped Mam wouldn’t hear anything.

She was in an unusually mellow mood when we got in. She grumbled at me and asked where I’d been, but accepted it when I said we’d been to visit Lainie.

‘Mrs Macpherson gave us tea,’ I told her. ‘She says we can visit again next month if we want.’

‘If that slut of a sister of yours is still there. But at least you’ve had your tea so you can get on with cleaning the bedrooms. Mr Phillips has gone on a visit of his own, but he’s paid his rent in full for next week – so we shan’t have to feed him. And he bought me a present.’ She stroked almost lovingly the bottle of good Irish whisky standing on the table in front of her. ‘Well, what are you waiting for?’

‘Do I have to do his room tonight, Mam? If he’s away the week … All right, but I only polished it through two days ago.’

‘Well, you can do it again – and less of your cheek, miss. Or you’ll feel the back of me hand.’

She took a swipe at me as I went past her, but her heart wasn’t in it for once and I was able to avoid the blow. She was pouring herself a glass of whisky as I collected my polishing rags and went through to the parlour. Tommy came clattering up the stairs after me. His face had lost the bright look it had worn all afternoon and I could see that he was close to tears.

‘What’s the matter, me darlin’?’

‘Mam told me to get out of her way. What’s wrong with her, Bridget? Maggie Ryan gets cross with Billy sometimes, but she’s not like Mam.’

I took hold of his hand, leading him into my bedroom and we sat on the bed. He had a little coughing fit, so I waited for him to finish.

‘I don’t know why she’s the way she is, Tommy. I don’t mind her getting at me, but I wish she would be kinder to you.’

‘I wish we could run away together. When I’m grown up I’m going to America to make my fortune and then you can come and live with me. I’ll take care of you, Bridget. Mam won’t shout at you then.’

‘I don’t mind her grumbling,’ I told him and kissed the top of his head. ‘Why don’t you slip next door with Billy and Maggie? I’ll come and fetch you when it’s time for bed.’

He nodded, clearly still troubled, and rubbed at his chest as if it hurt him. ‘Do you ever wish she would die, Bridget?’

‘No, of course not – and nor must you. It would be a mortal sin and you know what Father Brannigan would have to say about that, don’t you?’ The priest was his teacher at the Catholic school he attended, and Tommy respected him. He nodded but looked miserable as I continued: ‘I know Mam has a terrible temper, darlin’, but I don’t wish her harm. One day you and me will go away together.’

‘You should marry Ernie Cole,’ Tommy said and grinned as I pulled a face. ‘He’s sweet on you, our Bridget. You’re a real looker with them green eyes o’ yours. Ernie would come courting if you gave him half a chance.’

‘Get off next door, you cheeky monkey. I’ve work to do!’

I smiled to myself as he laughed and ran out, thinking about what he had said for a moment, but I sneaked a look at myself in the mirror. I supposed I wasn’t bad looking, my hair had reddish tints sometimes and my eyes were a bit green. I knew Ernie liked me, but I doubted he had any thoughts of marriage. I’d seen him off to the pub on Friday and Saturday nights, and the company he chose told me that he wasn’t thinking of settling yet.

I wasn’t sure whether I wanted to be taken out by Ernie – or anyone else come to that. I supposed that I might think of marriage one day, though I was a bit wary of getting trapped into the kind of marriages that some of my neighbours endured.

Anyway, there wasn’t much chance of my getting married, I didn’t have time to go courting.

Tommy’s cough was getting worse again. I wrapped a scarf I’d knitted around his neck as I sent him off to school.

‘Don’t stand about in the cold wind,’ I told him. ‘And ask Father Brannigan if you can stay in at break. Tell him I told you to ask.’

‘I’m all right,’ Tommy said, but he looked pale and he’d been awake half the night with his cough. ‘Can we visit Lainie tomorrow?’

‘Yes, I should think so. I spoke to Mrs Macpherson as I was walking home last night from the brewery. She said she was expecting us and I was to be sure to bring you, as she would have a special treat for you.’

Tommy’s face lit up and he gave me a quick hug, then ran off to call for Billy Ryan. Mam was still in her room; she’d grumbled about having a headache and told me to cook the lodger’s breakfast when I’d gone to call her earlier. I was still at the sink washing the dishes when Maggie Ryan opened the door and asked if she could come in.

‘O’ course you can.’ I dried my hands on a bit of towel. ‘I’ve done now, but I’ve time for a cuppa before I go to work if you fancy one? I could take one up to Mam – she’s feeling a bit under the weather the mornin’.’

‘Don’t you bother for me, Bridget love,’ Maggie said. She hesitated uncertainly for a moment. ‘It was your Tommy I came about, Bridget. He’s been after coughin’ again all night. Tell me to mind my own business if you like, but shouldn’t you be thinkin’ of takin’ him to the doctor?’

‘Do you think I ought, Maggie?’ Her words had echoed thoughts I had been trying to keep at bay. ‘Does he seem poorly to you? I asked Mam but she said it was just a chill, told me she’d no money to waste on visits to doctors.’

‘I’ve been wondering if I should tell you,’ Maggie said and again she was hesitant. ‘Our Billy says he was coughin’ up blood the other day in the playground.’

‘Blood? Maggie, no! Do you think he’s got …’

I couldn’t bring myself to say the word. Consumption was such a terrible illness. Children in the slum areas caught all kinds of nasty diseases, such as rickets and worms and a hundred and one other things, but consumption was contagious and they usually sent people in the final stages to the isolation infirmary, which was a horrible place.

‘Ah, don’t take on so, Bridget. Mick said as I shouldn’t say anything – you’ve troubles enough so you have – but it’s been on my mind.’

‘I’m glad you told me. I shall have to speak to Lainie – see what she thinks. We’re visiting her tomorrow. Tommy is looking forward to it.’

I glanced up at the ceiling as I heard a thumping noise upstairs. ‘It sounds as though Mam’s getting up. She had a headache this mornin’. Are you sure you won’t stay for a cup of tea, Maggie?’

‘No, I’m off to the market.’ She paused, then: ‘If there’s anythin’ I can do at any time, Bridget. I know it must be hard for you … the way things are with your mam.’

‘Thank you, Maggie. I shall have to run now or I’ll be late for work.’

‘I’ll call upstairs to your mam,’ Maggie said. ‘You get off, love. You’re in more of a hurry than me.’

‘Bless you, Maggie.’

I grabbed my shawl from the hook behind the door. Mrs Dawson had been quite sharp with me recently. She wouldn’t be happy if I was late again.

As I hurried through the lane to the brewery, my thoughts were with my brother. What would happen to Tommy if he had consumption? I knew that sometimes people went away to places where the air was better to get over it, but that was bound to cost money. We couldn’t afford to send Tommy to the mountains for a cure in some fancy hospital in Switzerland. Even the cost of a visit to the doctor was going to stretch my slim resources, but somehow I would find the money.

I thought of Tommy’s pale face as I’d sent him off to school that morning, and my heart caught with pain. What would I do if anything happened to him?

Lainie was looking pleased with herself when I saw her that Saturday afternoon. I asked if she’d heard from Hans, but she shook her head, a little smile on her mouth.

‘Why are you smiling like the cat that got the cream then?’

‘Am I?’ She touched something at her throat and I saw that she was wearing a heavy gold cross and chain. ‘I wonder why …’

‘Where did you get that? I’ve never seen you wear it before.’

‘A friend gave it to me …’ She laughed huskily, a sly look in her eyes. ‘Don’t look at me like that, Bridget. It was a gift, that’s all. I didn’t do anything for it – nothing wrong anyway.’

‘What will Hans say if he sees you wearing it?’

‘I can’t help it if men find me attractive,’ she said, looking sulky. ‘Hans said he would be back before now. If he’d come when he promised I wouldn’t have met … someone else.’

‘I thought you said you loved Hans?’

‘I do … in a way,’ she said and there was guilt in her eyes. ‘But … this other person … well, he treats me as if I were special.’

‘Hans wants to marry you,’ I reminded her.

‘I shall marry him when he comes back,’ she said, sounding cross. ‘I’m just having a little fun, Bridget. Besides, what has it got to do with you? You’re not my keeper. You’re nearly as bad as Mam.’

‘If that’s the way you feel I might as well go …’ I got up to leave but she caught at my hand.

‘Ah no,’ she said, giving me a shamefaced look. ‘Don’t go, me darlin’. I don’t want to quarrel with you.’

‘No, we shan’t quarrel over it,’ I said and sat down again. ‘But be careful, Lainie. You’ve always told me that Hans was a good man. Don’t throw his love away for a necklace.’

She smiled and tucked the cross inside her dress and I knew she wasn’t listening. ‘Forget it,’ she said. ‘I shall probably never see the other one again …’ She frowned as she heard Tommy coughing. ‘He doesn’t seem to get any better.’

‘Maggie said her Billy saw him coughing up blood in the playground.’