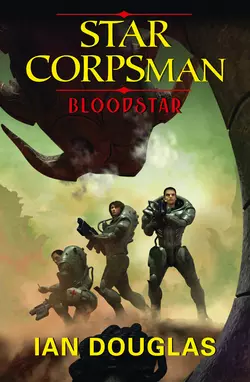

Bloodstar

Ian Douglas

Big, bold military science fiction action from one of the genre’s biggest names.In the 23rd Century, war is still hell…Corpsman Eliot Carlyle joined the Navy to save lives and see the universe. Now, he and Bravo Company’s Black Wizards of the interstellar Fleet Marine Force are en route to Bloodworld – a hellish, volatile rock, colonized by the fanatical Salvationists who desired an inhospitable world where they could suffer for humanity’s sins. However, their penance could prove fatal – for the mysterious alien race known as the Qesh have just made violent, bloody first contact.Suddenly, countless lives depend upon Bravo Company as the Marines prepare to confront a vast force of powerful, inscrutable enemies that unless stopped threaten the fate of homeworld Earth itself. And one dedicated medic, singled out by an extraordinary act of valour, will find himself with an astounding opportunity to alter the universe forever…

As always, now and forever,Brea

Table of Contents

Title Page (#u8d2a632f-e3c0-5965-8a9d-7c452b4f4fe4)

Dedication (#u16f90318-3a6b-52d1-a5a4-4362582d34fe)

The Qesh were solidly in control. (#u92056d5a-88fb-544c-9506-859664f3b992)

Chapter One (#ud344b36a-dae1-59ea-8842-8dd89359d4fa)

Chapter Two (#u5fe57270-6c76-5653-b0b9-8abb6c49d802)

Chapter Three (#ua32b5110-b5c5-579d-8581-139a044eba27)

Chapter Four (#uc396e156-bca2-5ec7-8098-cf34bb3fb778)

Chapter Five (#u369656b1-166d-543a-bd6c-e7d02dd2458c)

Chapter Six (#u6ea46376-5a06-5b10-9ab7-cf412786ac77)

Chapter Seven (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Eight (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Nine (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Ten (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Eleven (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twelve (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Thirteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Fourteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Fifteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Sixteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Seventeen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Eighteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Nineteen (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-One (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Two (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Three (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter Twenty-Four (#litres_trial_promo)

Epilogue (#litres_trial_promo)

Star Corpsman Timeline (#litres_trial_promo)

Star Corpsman Glossary (#litres_trial_promo)

By Ian Douglas (#litres_trial_promo)

Copyright (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

The Qesh were solidly in control.

There were armed guards standing at several busy intersections, and small groups of them patrolled the corridors like cops on a beat. The humans we saw watched the patrolling Qesh with expressions ranging from boredom to terror; no one tried to talk with the invaders, and for their part, the invaders didn’t seem predisposed to interfere with the human crowd.

About ten minutes passed before we started getting signal breakup, and then the image dissolved into pixels and winked out. The transmission, shifting around randomly across tens of thousands of frequencies each second, probably couldn’t be monitored by the Qesh, but it could be blocked, by tens of meters of solid rock if nothing else. What we received before that happened, though, had been useful.

And disturbing. If the humans were cooperating with the Qesh, had they already given the invaders access to their computer records?

Had the Qesh already learned the location of Earth?

And how could we find out if they had?

Chapter One

I’M JUST GLAD I’M NOT AFRAID OF HEIGHTS.

Well, at least not much.

Our Cutlass hit atmosphere at something like 8 kilometers per second, bleeding off velocity in a blaze of heat and ionization, the sharp deceleration clamping down on my chest like a boa constrictor with a really bad attitude. I hadn’t been able to see much at that point, and most of my attention was focused simply on breathing.

But then the twelve-pack cut loose, and my insert pod went into free fall. I was thirty kilometers up, high enough that I could see the curve of the planet on my optical feed: a sharp-edged slice of gold-ocher at the horizon, with a deep, seemingly bottomless purple void directly below. We were skimming in toward the dawn with all of the aerodynamic efficiency of falling bricks. The Cutlass scratched a ruler-straight contrail through the black above our heads, scattering chaff to help conceal our drop from enemy radar and lidar assets on the ground.

The problem with a covert insertion is that the covert part is really, really hard to pull off. The bad guys can see you coming from the gods know how far away, and you tend to make a lot of noise, figuratively speaking, when you hit atmosphere.

But that’s what the U.S. Marines—and specifically Bravo Company, 1

Battalion, the Black Wizards—do best.

“Deploying airfoil,” a woman’s voice, a very sexy woman’s voice, whispered in my head, “in three … two … one …”

Why do they make our AIs sound like walking wet dreams?

My insertion pod had been a blunt, dead-black bullet shape until now, three meters long and just barely wide enough to accommodate my combat-armored body. The shell began unfolding now, growing a set of sharply back angled delta wings. The air outside was still achingly thin, but the airfoil grabbed hold with a shock akin to slamming into a brick wall. Deceleration clamped down on me once more—that damned boa constrictor looking for breakfast again—this time with a shuddering jolt that felt like my pod was shredding itself to bits.

The external sensor feeds didn’t show anything wrong, nor did my in-head readout. I was dropping through twenty-two kilometers now, and everything was going strictly according to … what the hell is that?

Red-gold ruggedness seemed to pop up directly ahead of me, looming, night-shrouded, below—and huge, and I stifled a shrieking instant of sheer panic. It was the crest of Olympus Mons, the very highest, most easterly slopes catching the rays of the Martian dawn long before sunrise reaches the huge mountain’s base. That twenty-two kilometers, I realized with a shudder, was measured from the areodetic datum, the point that would mark sea level on Mars if the planet actually had seas.

Olympus Mons, the biggest volcano in the solar system, rises twenty-one kilometers from the datum, three times the elevation of Everest, on Earth, and fully twice the height of the volcano Mauna Kea as measured from the ocean floor. I was skimming across the six nested calderas at the summit now, the rocky crater floor a scant couple of kilometers beneath my fast-falling pod. The calderas’ interior deeps were still lost in midnight shadow, but the eastern escarpment, seemingly suspended in a mass of wispy white clouds, caught the light of the shrunken rising sun, and from my vantage point it looked like those vertical rock cliffs were about to scrape the nanomatrix from my pod’s belly. In another moment, however, the escarpment was past, the 80-kilometer-wide caldera dropping behind with startling speed.

The plan, I’d known all along, was to skim just above the volcanic summit, a simple means of foxing enemy radar, but I’d not been ready for the visual reality of that near miss. My pod was totally under AI control, of course, the sentient software flexing my delta wings in rapid shifts far too fast for a mere human brain to follow. The pilot was taking me lower still, until the escarpments behind loomed above, rather than below.

Olympus Mons is huge, covering an area about the size of the state of Arizona, and that means it’s also flat, despite the summit’s dizzying altitude. The average slope is only about five degrees, and you can be standing halfway up the side of the mountain and not even be aware of it.

The slope was enough, though, that it put the bulk of Mount Olympus behind us, helping to shield us from enemy sensors ahead as we glided into the final phase of our descent. The active nano coating on the hulls of our pods drank radar, visible light—everything up through hard X-rays—giving us what amounted to invisibility. But no defense is perfect. If the enemy had known what he was doing, he’d have had whole sensory array farms across the mountain’s broad summit—not to mention point-defense lasers and antiship CPB batteries.

Hell, maybe they did and we were already dead in their crosshairs. My sensors weren’t picking up any hostile interest, though. I wished I could talk to the others, compare technical notes, but Captain Reichert would have burned me out of the sky himself for breaking comm silence.

Follow the download. Ride your pod down. Leave the thinking to the AIs. They know a hell of a lot more about it than you do.

Two hundred kilometers farther, and the base escarpment of Olympus Mons, a sheer five-kilometer cliff, slipped past in the darkness. Across the Tharsis bulge now, still descending, beginning a shuddering weave through the predawn sky to bleed off my remaining speed. The three-in-a-row volcanoes of the Tharsis Montes complex slid past. Then the Tharsis highlands gave way to the broken and chaotic terrain of the Noctis Labyrinthus, a twelve-hundred-kilometer stretch of badlands where we did not want to touch down under any stretch of the imagination. I swept into the local dawn, the sun coming up directly ahead with the abruptness of a thermonuclear blast, but in total silence.

“Landing deployment in twenty seconds,” the sexy voice told me.

“Great. Any sign of bad guys picking us up?”

“Negative on hostile activity. Military frequency signals from objective appear to be normal traffic.”

“That,” I told her, “is the sweetest news I’ve heard all morning.”

Download

Mission Profile: Ocher Sands

Operation Damascus Steel/OPPLAN#5735/15NOV2245

[extract]

… while Second Platoon will deploy by squad via Cutlass TAV/AIP to LZ Damascus Blue, location 12

26’ S, 87

55’ W, in the Sinai Planum. Upon landing, squads will form up individually and move on assigned objectives utilizing jumpjets. Units will be under Level-3 communications silence, and will if possible avoid enemy surveillance.

Second Platoon Objective is Base Schiaparelli, located on the Ius Chasma, coordinates 7

19’ 30.66”, 87

50’ 46.40” W …

The Black Wizards’ LZ was on the Sinai Planum, south of Ius Chasma, some 3,500 kilometers southeast of the summit of Olympus Mons. This was the scary part, the part where everything could go pear-shaped in a big hurry if the bastard god Murphy decided to favor me with His omnipotent and manifold blessings. “Double-check me,” I told her as I ran through the final checklist.

I saw green across the board projected in my mind.

“All CA systems appear functional,” the voice told me. She hesitated, then added, “Good luck, Petty Officer Carlyle.”

And what, I wondered, did an AI know about luck? “Thanks, girlfriend,” I muttered out loud. “Whatcha doing after the war, anyway?”

“I do not understand your question.”

“Ah, it would never work anyway, you and me,” I told her, and I waited for her to dump me.

Half a kilometer above the red-ocher desert floor, my AIP-81 insertion pod peeled open beneath and around me as if at the tug of a giant zipper, and abruptly I was in the open air and falling toward the Martian surface.

But not far. The delta-winged pod continued to open somewhere above me, unfolding into an improbably large triangular airfoil attached by buckyweave rigging and harness to my combat armor. The jolt when the wing deployed fully felt like it was going to yank me back into orbit. The ground was rushing past, and up, at a sickening pace, and I resisted the urge to crawl up the rigging to escape the blur of rock and sand.

Then the autorelease fired and the harness evaporated. My backpack jets kicked in, the blast shrill and almost inaudible in the thin atmosphere, kicking up a swirl of pale dust beneath my boots as they dropped to meet their up-rushing shadows.

I hit as I’d been trained, letting the armor take the jolt, relaxing my knees, letting myself crumple with the impact.

And I was down.

Down and safe, at least for the moment. My suit showed full airtight integrity, I couldn’t feel any pain, no broken bones or sprains or strains from an awkward landing. I stood up, just a little shaky on my feet, and took in the broad expanse of the Martian landscape, brown and rust-ocher sand and gravel beneath a vast and deep mid-morning sky, ultramarine above, pink toward the horizon.

I was alone. Even my girlfriend was gone, the circuitry that had maintained her abbreviated personality nano-D’ed into microscopic dust.

Well, not entirely alone. Somewhere out there in all that emptiness were forty-seven men and women, the rest of my Marine insertion platoon.

First things first. Navy Hospital Corpsmen are the combat medics of the Marine Corps, but our technical training makes us the sci-techs of Marine advance ops as well. Planetology, local biology and ecosphere dynamics, atmosphere chemistry—I was responsible for all of it on this mission, at least so far as Squad Bravo was concerned.

I knew what the answers would be. This was Mars, after all, and humans had been living here for a couple of centuries, now. But I drew a test sample into my ES-80 sniffer and ran the numbers anyway. Do it by the download.

Carbon dioxide, 95 percent, with 2.7 percent nitrogen, 1.6 percent argon, and a smattering of other molecular components, all at 600 pascals, which is less than one percent of the surface atmospheric pressure on Earth. Temperature a brisk minus 60 degrees Celsius. Exotic parabiochemistries powered by the unfiltered UV from the distant sun. Thirty parts per billion of methane and 130 ppb of formaldehyde—that was from the microscopic native critters living at the lower permafrost boundaries underground, the reason we’d abandoned plans to terraform the place. Gotta keep Mars safe and pristine for the alien wee beasties, after all.

I recorded the data, exactly as if we had no idea what was on Mars, and uploaded it to the squadnet. I also needed to—

“Corpsman, front!” The voice of Corporal Lewis came over my com link. “Marine down!”

Shit! “Moving,” I said, my voice sounding uncomfortably loud within the confines of my helmet. I called up the tacsit display on my in-head, getting my bearings. There were ten green dots—the one at dead center was me—and one off to the side flashing red. I turned, getting a bearing. Private Colby was that way, 2 kilometers away. Corporal Lewis was with him.

“I’ve got you on my display,” I told Colby. Under a Level-3 comm silence, we were using secure channels—tightly beamed IR laser-com signals relayed both line of sight and through our constellation of micro comsats in orbit. The setup allowed short-range communications with little chance of the enemy tapping in unless he was directly in the path of one of our beams, but we were still supposed to keep long-range chatter to an absolute minimum.

I took a short and lumbering run, kicked in my jets, and flew.

Service Manual Download

Standard-Issue Military Equipment

MMCA Combat Armor, Mk. 10

[extract]

… including alternating ultra-light layers of carbon buckyweave fiber and titanium-ceramic composite with an active-nano surface programmable by the wearer for either high or low visibility, or for albedo adjustments for thermal control. Power is provided by high-density lutetium-polonium batteries, allowing approximately 300 hours service with normal usage depending upon local incident thermal radiation.

Internally accessible stores carry up to three days’ rations of air, water, and food, which can be extended using onboard extractors and nanassemblers. Service stores of cryogenic hydrogen and oxygen [crH

/crO

] can be carried to further extend extraction/assembled expendables.

Combat armor mass averages 20–25 kg, though with full expendables load-out this may increase to as much as 50 kilos …

Flight Mode

Mk. 10 units are capable of short periods of flight depending on local gravity, or of jet-assisted maneuvers in a microgravity environment. The M287 dorsal-mounted jumpjet unit uses metastable N-He

, commonly called meta, as propellant, stored in crogenically inert high-pressure backpack tanks.

Proper maintenance of meta HP fuel tanks is vital for safe storage, transport, and operation of jumpjet units …

Marine combat armor isn’t really designed for flight, especially in-atmosphere, but the Martian air is thin enough that it’s close to hard vacuum, and my “flight” was more a series of long, low bounds across the rocky, dark red-brown terrain, aided by the low gravity—about .38 of Earth normal. That meant I got more boost for my buck, and just a few quick thruster bursts brought me down in the boulder-strewn field where Private Colby was curled up on the sand, his arms wrapped around his left shin, with Corporal Lewis at his side.

I’d checked his readouts during my flight, of course—at least when I wasn’t watching my landings to avoid doing what I suspected Colby had just done to himself—landing like shit and breaking something. Just because you weigh less than half what you do on Earth here doesn’t mean you don’t still have your normal mass, plus the mass of your combat armor. Bones can only take so much stress, and a misstep can snap one. Colby’s data feed showed he was conscious and in pain, respiration and heart rate high, suit intact. Thank the gods for that much, anyway. A breach in the suit brings with it its own list of headaches.

“He hit a rock, Doc!” Lewis said, looking up as I slid to a halt in loose sand. “He hit a rock coming down!”

“So I see. How you doing, Colby?”

“How do you fucking goddamn think I’m fucking feeling goddamned stupid-ass bullshit questions—”

I had already popped the cover on Colby’s armor control panel, located high on his left shoulder, and was punching in my code. Before I hit the SEND key, though, I hit the transparency control for his visor, then rolled him enough that I could peer through his visor and into his eyes. “Look at me, Colby!” I called. “Open your eyes!”

His eyes opened, and I looked at his pupils, comparing one with the other. They were the same size. “Your head hurt at all?” I asked.

“Goddamn it’s my fucking leg not my head Doc will you fucking do something fer chrissakes—”

Good enough. I hit the SEND key, and Colby’s suit auto-injected a jolt of anodynic recep blockers into his carotid artery. Nananodyne can screw you up royally if you have a head injury, which was why I’d checked his pupils and questioned him first.

“Can we get him up on his feet, Doc?” Lewis asked.

“Don’t know yet” I said. “Gimme a sec, okay?”

I jacked into Colby’s armor and instituted a full scan. Infrared sensors woven into his skinsuit picked up areas of heat at various wavelengths and zipped a picture of his body into my head. The data confirmed no pressure leaks—those would have shown up as cold—but there was plenty of bright yellow inflammation around his left shin. No sign of bleeding; that would have appeared as a hot spot, spreading out and cooling to blue inside the greave. Colby was relaxing moment by moment. Those nanonarcs target the thalamus and the insular cortex of the brain, switching off the doloric receptors and blocking incoming pain messages.

Heart rate 140 and thready, BP 130 over 80, respiration 28 and shallow, and elevating adrenaline and noradrenaline, which meant an onset of the Cushing reflex. His body temp was cooling at the extremities which meant he was on the verge of going shocky as blood started pooling in his core. I told his suit to manage that—boosting the heat a bit and gently relaxing the constriction in the arteries leading to the head to keep his brain fed.

That would hold him until I could take a close-up look at his leg.

In the old days, there wouldn’t have been much I could have done except locking his combat armor, turning his left greave into an emergency splint. If the patient wasn’t wearing full armor, you used whatever was available, from a ready-made medical wrap that hardens into a splint when you run an electric current through it, to simply tying the bad leg to the good, immobilizing it. By keying a command into Colby’s mobility circuits, the armor itself would clamp down and hold the broken bones in place, but there was one more thing I could try in order to get him up and mobile.

I reached into my M-7 kit and removed a small hypo filled with 1 cc of dark gray liquid. The tip fit neatly into a valve located beside his left knee, opening it while maintaining the suit’s internal pressure, and when I touched the button, a burst of high-pressure nitrogen gas fired the concoction through both his inner suit and his skin. Nanobots entered his bloodstream at the popliteal artery, activating with Colby’s body heat and transmitting a flood of data over my suit channels. I thoughtclicked several internal icons, deactivating all of the ’bots that were either going the wrong way or were adhering to Colby’s skinsuit or his skin, and focused on the several thousand that were flowing now through the anterior and posterior tibial arteries toward the injury.

I wanted to go inside … but that would have given me a bit too intimate of a view, too close and too narrow to do me any good. What I needed to see was the entire internal structure of the lower leg—tibia and fibula; the gastrocnemius, soleus, and tibialis anterior muscles; the tibialis anterior and posterior tibial arteries; and the epifascial venous system. I sent Program 1 to the active ’bots, and they began diffusing through capillaries and tissue, adhering to the two bones, the larger tibia and the more slender fibula off to the side, plating out throughout the soft tissue, and transmitting a 3-D graphic to my in-head that showed me exactly what I was dealing with.

I rotated the graphic in my mind, checking it from all angles. We were in luck. I was looking at a greenstick fracture of the tibia—the major bone that runs down the front of the shin, knee to ankle. The bone had partially broken, but was still intact on the dorsal surface, literally like a stick half broken and bent back. The jagged edges had caused some internal bleeding, but no major arteries had been torn and the ends weren’t poking through the skin. The fibula, the smaller bone running down the outside of the lower leg, appeared to be intact. The periosteum, the thin sheath of blood vessel- and nerve-rich tissue covering the bone, had been torn around the break of course, which was why Colby had been hurting so much.

“How’s he doing, Doc?”

The voice startled me. Gunny Hancock had come up out of nowhere and was looking over my shoulder. I’d had no idea that he was there.

“Greenstick fracture of the left tibia, Gunny,” I told him. “Shinbone. I have him on pain blockers.”

“Can he walk?”

“Not yet. He should be medevaced. But I can get him walking if you want.”

“I want. The LT wants to finish the mission.”

“Okay. Ten minutes.”

“Shit, Gunny,” Colby said. “You heard Doc. I need a medevac!”

“You’ll have one. Later.”

“Yeah, but—”

“Later, Marine! Now seal your nip-sucker and do what Doc tells ya!”

“Aye, aye, Gunnery Sergeant.”

I ignored the byplay, focusing on my in-head and a sequence of thoughtclicks routing a new set of orders to the ’bots in Colby’s leg. Program 5 ought to do the trick.

“How you feeling, Colby?” I asked.

“The pain’s gone,” he said. “The leg feels a bit weak, though.” He flexed it.

“Don’t move,” I told him. “I’m going to do some manipulation. It’ll feel funny.”

“Okay …” He didn’t sound too sure of things.

Guided by the new program download, some hundreds of thousands of ’bots, each one about a micron long—a fifth the size of a red blood cell—began migrating through soft tissue and capillaries, closing in around the broken bone until it was completely coated above and below the break. In my in-head, the muscles and blood vessels disappeared, leaving only the central portion of the tibia itself visible. I punched in a code on Colby’s armor alphanumeric, telling it to begin feeding a low-voltage current through the left greave.

Something smaller than a red blood cell can’t exert much in the way of traction unless it’s magnetically locked in with a few hundred thousand of its brothers, and they’re all pulling together. In the open window in my head, I could see the section of bone slowly bending back into a straight line, the jagged edges nesting into place. The movement would cause a little more periosteal damage—there was no way to avoid that—but the break closed up neatly.

“Doc,” Colby said, “that feels weird as hell.”

“Be glad I doped you up,” I told him. “If I had to set your leg without the anodyne, you’d be calling me all sorts of nasty things right now.”

I locked the nano sleeve down, holding the break rigid. I sent some loose nanobots through the surrounding tissue, turning it ghostly visible on the screen just to double-check. There was a little low-level internal bleeding—Colby would have a hell of a bruise on his shin later—but nothing serious. I diverted some anodynes to the tibial and common fibular nerves at the level of his knee with a backup at the lumbosacral plexus, shutting down the pain receptors only.

“Right,” I told him. “Let me know if this hurts.” Gingerly, I switched off the receptor blocks in his brain.

“Okay?”

“Yeah,” he said. “It just got … sore, a little. Not too bad.”

“I put a pain block at your knee, but your brain is functioning again. At least as well as it did before I doped you.”

“You’re a real comedian, Doc.”

I told his armor to lock down around his calf and shin, providing an external splint to back up the one inside. I wished I could check the field medicine database, but the chance of the enemy picking up the transmission was too great. I just had to hope I’d remembered everything important, and let the rest slide until we could get Colby back to sick bay.

“Okay, Gunny,” I said. “He’s good to go.”

I know it seemed callous, but a tibia greenstick is no big deal. If it had been his femur, now, the big bone running from hip to knee, I might have had to call for an immediate medevac. The muscles pulling the two ends of the femur together are so strong that the nano I had on hand might not have been enough. I would have had to completely immobilize the whole leg and keep him off of it, or risk doing some really serious damage if things let go.

The truth of the matter is that they pay us corpsmen for two jobs, really. We’re here to take care of our Marines, the equivalent of medics in the Army, but in the field our first priority is the mission. They hammer that into us in training from day one: provide emergency medical aid to the Marines so that they can complete their mission.

“How about it, Colby. Can you get up?”

The Marine stood—with an assist from Lewis and the Gunny. “Feels pretty good,” he said, stamping the foot experimentally.

“Don’t do that,” I told him. “We’ll still need to get you to sick bay, where they can do a proper osteofuse.”

“Good job, Doc,” Gunny told me. “Now pack up your shit and let’s hump it.”

I closed up my M-7 and dropped both the hypo and the sterile plastic shell it had come in into a receptacle on my thigh. They’d drilled it into us in FMF training: never leave anything behind that will give the enemy a clue that you’ve been there.

While I’d been working on Colby, the rest of the recon squad had joined up about a kilometer to the north and started marching. Gunny, Lewis, Colby, and I were playing catch-up now, moving across that cold and rock-strewn desert at double-time.

According to our tacsit displays, we were 362 kilometers and a bit directly south of our objective, a collection of pressurized Mars huts called Schiaparelli Base. If we hiked it on foot, it would take us the better part of ten days to make it all the way.

Not good. Our combat armor could manufacture a lot of our logistical needs from our surroundings, at least to a certain extent. It’s called living off the air, but certain elements—hydrogen and oxygen, especially—are in very short supply on Mars. Oxygen runs to about 0.13 percent in that near-vacuum excuse for an atmosphere, and free molecular hydrogen is worse—about fifteen parts per billion. You can actually get more by breaking down the hints of formaldehyde and methane released by the Martian subsurface biota, but it’s still too little to live on. The extractors and assemblers in your combat armor have to run for days just to get you one drink of water. The units recycle wastes, of course; with trace additives, a Marine can live on shit and piss if he has to, but the process yields diminishing returns and you can’t keep it up for more than a few days.

So Lewis and I doubled up with Colby. There was a risk of him coming down hard and screwing the leg repairs, but with me on his right arm and Lewis on his left, we could reduce the stress of landing on each bound. We taclinked our armor so that the jets would fire in perfect unison, and put ourselves into a long, flat trajectory skimming across the desert. Gunny paced us, keeping a 360-eye out for the enemy, but we still seemed to have the desert to ourselves.

And four hours later we reached the Calydon Fossa, a straight-line ditch eroded through the desert, half a kilometer deep and six wide. It took another hour to get across that—the canyon was too wide for us to jet-jump it, and the chasma slopes were loose and crumbling. But we slogged down and we slogged up and eight kilometers more brought us to the Ius Chasma.

It’s not the deepest or the most spectacular of the interlaced canyons making up the Valles Marineris, but it’ll do: Five and a half kilometers deep and almost sixty kilometers across at that point, it’s deep enough to take in Earth’s Grand Canyon as a minor tributary. The whole Valles Marineris is almost as long as the continental United States is wide back home—two hundred kilometers wide and ten kilometers deep at its deepest—where the Grand Canyon runs a paltry 1,600 meters deep.

The view from the south rim was spectacular.

But we weren’t there for sightseeing. We rendezvoused with First Squad and made the final approach to Schiaparelli Base. I stayed back with Colby while the others made the assault, but everything went down smooth as hyperlube. The whole sequence would have been a lot more exciting if this had been a real op, but the bad guys were U.S. Aerospace Force security troops, and Ocher Sands is the annual service-wide training exercise designed to work out the bugs and accustom our combat troops to operating in hostile environments against a high-tech enemy.

I can’t speak for the USAF bluesuits, but we had a good day. Despite Colby’s injury and a bad case of the scatters coming down—someone was going to get chewed a new one for that little SNAFU—all eight squads pulled it together, deployed without being spotted, and took down their assigned objectives, on sched and by the download. An hour later we had a Hog vectoring in for medevac.

I rode back up to orbit with Colby.

And it was just about then that the fecal matter intercepted the rotational arc of the high-speed turbine blades.

Chapter Two

FOR A CENTURY NOW WE HUMANS HAVE BEEN LURKERS ON THE GALACTIC Internet, listening and learning but not saying a word. We’re terrified, you see, that they might find us.

The EG-Net, as near as we can tell, embraces a fair portion of the entire Galaxy, a flat, hundred-thousand-light-year spiral made of four hundred billion suns and an estimated couple of trillion planets. The Net uses modulated gamma-ray lasers, which means, thanks to the snail’s-pace crawl of light, that all of the news is out of date to one degree or another by the time we get it. Fortunately, most of what’s on there doesn’t have an expiration date. The Starlord Empire has been collapsing for the past twenty thousand years, and the chances are good that it’ll still be collapsing twenty thousand years from now.

The Galaxy is a big place. Events big enough to tear it apart take a long time to unfold.

The closest EG transmission beam to Sol passes through the EG Relay at Sirius, where we discovered it during our first expedition to that system 128 years ago. The Sirius Orbital Complex was constructed just to eavesdrop on the Galactics—there’s nothing else worthwhile in the system—and most of what we know about Deep Galactic history comes from there. We call it the EG, the Encyclopedia Galactica, because it appears to be a data repository. Nested within the transmission beams crisscrossing the Galaxy like the web of a drunken spider are data describing hundreds of millions of cultures across at least six billion years, since long before Sol was born or the Earth was even a gleam in an interstellar nebula’s eye. It took us twenty years just to crack the outer codes to learn how to read what we were seeing. And what we’ve learned since represents, we think, something less than 0.01 percent of all of the information available.

But even that microscopic drop within the cosmic ocean is enough to prove just how tiny, how utterly insignificant, we humans are in the cosmic scheme of things.

The revelation shook humankind to its metaphorical core, an earthquake bigger than Copernicus and Galileo, deeper than Darwin, more far-reaching than Hubbell, more astonishing than Randall, Sundrum, and Witten.

And the revelation damn near destroyed us.

“HEY, E-CAR!” HM3 MICHAEL C. DUBOIS HELD UP A LAB FLASK AND swirled the pale orange liquid within. “Wanna hit?”

I was just finishing a cup of coffee as I wandered into the squad bay, and still had my mug in hand. I sucked down the dregs and raised the empty cup. “What the hell are you pedaling this time, Doob?” I asked him.

“Nothing but the best for the Black Wizard heroes!”

“Paint stripper,” Corporal Calli Lewis told me, and she made a bitter face. I noticed that she took another swig from her mug, however, before adding, “The bastard’s trying to poison us.”

Doobie Dubois laughed. “Uh-uh. It’s methanol that’ll kill you … or maybe make you blind, paralyzed, or impotent. Wood alcohol, CH

OH. This here is guaranteed gen-u-wine ethanol, C

H

OH, straight out of the lab assemblers and mixed with orange juice I shagged from a buddy in the galley. It’ll put hair on your chest.”

“Not necessarily a good thing, at least where Calli’s concerned,” I said as he poured me half a mug.

“Yeah?” he said, and gave Calli a wink. “How do you know? Might be an improvement!”

“Fuck you, squid,” she replied.

“Any time you want, jarhead.”

I took a sip of the stuff and winced. “Good galloping gods, that’s awful!”

“Doc can’t hold his ’shine,” Sergeant Tomacek said, and the others laughed. A half dozen Marines were hanging out in the squad bay, and it looked like Doob had shared his talent for applied nanufactory chemistry with all of them. Highly contra-regs, of course. The Clymer, like all U.S. starships, is strictly dry. I suspected that Captain Reichert knew but chose not to know officially, so long as we kept the party to a dull roar and no one showed up drunk on duty.

The viewall was set to show an optical feed from outside, a deck-to-overhead window looking out over Mars, 9,300 kilometers below. The planet showed a vast red-orange disk with darker mottling; I could see the pimples of the Tharsis bulge volcanoes easily, with the east-to-west slash of the Valles Marineris just to the east. Phobos hung in the lower-right foreground, a lumpy and dark-gray potato, vaguely spherical but pocked and pitted with celestial acne. The big crater on one end—Stickney—and the Mars Orbital Research Station, rising from the crater floor, were hidden behind the moonlet’s mass, on the side facing the planet. The image, I decided, was being relayed from the non-rotating portion of the George Clymer. The Clymer’s habitation module was a fifty-meter rotating ring amidships, spinning six and a half times per minute to provide a modest four tenths of a gravity, the same as we’d experienced down on Mars.

“So what’s the celebration?” I asked Dubois. He always had a reason for breaking out the lab-nanufactured drinkables.

“The end of FMF training, of course! What’d you think?”

I took another cautious sip. It actually wasn’t too bad. Maybe that first swig had killed off the nerve endings.

“You’re one-eighty off course, Doob,” I told him. “We still have Europa, remember?”

FMF—the Fleet Marine Force—was arguably the most coveted billet in the entire U.S. Navy Hospital Corps. To win that silver insignia for your collar, you needed to go through three months of Marine training at Lejeune or Pendleton, then serve with the Marines for one year, pass their physical, demonstrate a daunting list of Marine combat and navigation skills, and pass a battery of tests, both written and in front of a senior enlisted board.

I’d been in FMF training since I’d made Third Class a year ago; our assignment on board the Clymer was the final phase of our training, culminating in the Ocher Sands fun and games that had us performing a live insertion and taking part in a Marine planetary assault. After this, we were supposed to deploy to Europa for three weeks of practical xenosophontology, swimming with the Medusae. After that, those of us still with the program would take our boards, and if we were lucky, only then would we get to append the letters FMF after our name and rank.

“Not the way I heard it, e-Car,” he said. He took a swig of his product straight from the flask. “Scuttlebutt has it we’re deploying I-S.”

I ignored use of the disliked handle. My name, Elliot Carlyle, had somehow been twisted into “e-Car.” Apparently there was a law of the Corps that said everyone had to have a nickname. Doob. Lewis was “Louie.” I’d spent the past year trying to get myself accepted as “Hawkeye,” a nod both to James Fenimore Cooper and to a twentieth-century entertainment series about military medical personnel in the field from which I’d downloaded a few low-res 2-D episodes years ago.

“Interstellar?” I said. “You’re full of shit. This stuff’s rotting your gray cells.”

“Don’t be so sure about your diagnosis, Doc,” Lewis told me. “I heard the same thing from a buddy in Personnel.”

“You’re both full of it,” I said. “Why would they send us?”

“Our dashing good looks and high intelligence?”

“In your case, Doob, it probably has to do with a punishment detail. You on the Old Man’s shit list?”

“Not so far as I know.”

“So what’s supposed to be going down?”

Dubois grew serious, which was damned unusual for him. “The Qesh,” he said.

Download

Encyclopedia Galactica/Xenospecies Profile

Entry: Sentient Galactic Species 23931

“Qesh”

Qesh, Qesh’a, Imperial Qesh, Los Imperiales, “Jackers,” “Imps”

Civilization Type: 1.165 G

TL 20: FTL, Genetic Prostheses, Quantum Taps, Relativistic Kinetic Conversion

Societal Code: JKRS

Dominant: clan/hunter/warrior/survival

Cultural library: 5.45 x 10

bits

Data Storage/Transmission DS/T: 2.91 x 10

s

Biological Code: 786.985.965

Genome: 4.2 x 10

bits; Coding/non-coding: 0.019.

Biology: C, N, O, S, S

, Ca, Cu, Se, H

O, PO

TNA

Diferrous hemerythrin proteins in C

H

COOH circulatory fluid.

Mobile heterotrophs, carnivores, O

respiration.

Septopedal, quad- or sextopedal locomotion.

Mildly gregarious, polygeneric [2 genera, 5 species]; trisexual.

Communication: modulated sound at 5 to 2000 Hz and changing color patterns.

Neural connection equivalence NCE = 1.2 x 10

T = ~300

to 470

K; M = 4.3 x 10

g; L: ~5.5 x 10

s

Vision: ~5 micrometers to 520 nanometers, Hearing: 2 to 6000 Hz

Member: Galactic Polylogue

Receipt galactic nested code: 1.61 x 10

s ago

Member: R’agch’lgh Collective

Locally initiated contact 1.58 x 10

s ago

Star F1V; Planet: Sixth

a = 2.4 x 10

m; M = 2.9 x 10

g; R = 2.1 x 10

m; p = 2.7 x 10

s

P

= 3.2 x 10

s, G = 25.81 m/s

Atm: O

26.4, N

69.2, CO

2.5, CO 2.1, SO

0.7, at 2.5 x 10

Pa

Librarian’s note: First direct human contact occurred in 2188 C.E. at Gamma Ophiuchi. Primary culture now appears to be nomadic predarian, and is extremely dangerous. Threat level = 1.

We’d all downloaded the data on the Qesh, of course, as part of our Marine training. Know your enemy and all of that. Humans had first run into them fifty-nine years ago, when the Zeng He, a Chinese exploration vessel, encountered them while investigating a star system ninety-some light years from Sol. The Zeng He’s AI managed to get off a microburst transmission an instant before the ship was reduced to its component atoms. The signal was picked up a few years later by a Commonwealth vessel in the area and taken back to Earth, where it was studied by the Encyclopedian Library at the Mare Crisium facility on the moon. The Zeng He’s microburst had contained enough data to let us find the Qesh in the ocean of information within the Encylopedia Galactica and learn a bit about them.

We knew they were part of the R’agch’lgh Collective, the Galactic Empire, as the news media insisted on calling it. We knew they were from a high-gravity world, that they were big, fast, and mean.

And with the ongoing collapse of the Collective, we knew they’d become predarians.

The net media had come up with that word, a blending of the words predators and barbarians. That was unfortunate, since in our culture barbarian implies a relatively low technology; you expect them to be wearing shaggy skins, horned helmets, and carrying whopping big swords in their primary manipulators, looking for someone to pillage.

As near as we could tell, they were predators, both genetically and by psychological inclination. Their societal code, JKRS—which is where “Jackers,” one of their popular nicknames, had come from—suggested that their dominant culture was organized along clan/family lines, that they’d evolved from carnivorous hunters, that they considered themselves to be warriors and possessed what might be called a warrior ethos, and, perhaps the most chilling, that they possessed an essentially Darwinian worldview—survival of the fittest, the strong deserve to live. The fact that their technological level allowed them to accelerate asteroid-sized rocks to near-c and slam them into a planet was a complementary extra.

These guys had planet-killers.

The Crisium librarians thought—guessed would be the more accurate term—that the Qesh constituted some sort of military elite within the R’agch’lgh Collective, a kind of palace guard or special assault unit used to take out worlds or entire species that the Collective found to be obstreperous or inconvenient. But with the fall of the Collective, the Qesh were thought to have gone freelance, wandering the Galaxy in large war fleets taking what they wanted and generally trying to prove that they were the best, the strongest, the fittest—something like a really sadistic playground bully without adult supervision.

That change of status must have been fairly recent—within the last couple of thousand years or so. According to the EG, they were still working for the Collective.

And for all we knew maybe some of them were, way off, deep in toward the Galactic Core, where the R’agch’lgh might still be calling the shots. Our local branch of the EG Library hadn’t been updated for five thousand years, however, and evidently a lot had happened in the meantime.

The Galaxy was going through a period of cataclysmic change, but from our limited perspective, it was all taking place in super-slow motion.

“What,” I said. “The Qesh are coming here?”

“My friend in Personnel,” Lewis said, “told me there’d been a call for help from one of our colonies. The colony is supposed to be pre-Protocol, so …” She shrugged. “Send in the Marines.”

It made sense, in a horrific kind of way. Commonwealth Contact Protocol had been developed in 2194, and it laid out very strict rules and regs governing contact with new species. Partially, that was to protect the new species, of course. Human history has a long and bloody tradition of one culture stumbling into a new and eradicating it, through disease, through greed, through conquest, through sheer, bloody-minded stupidity.

But even more it was to protect us. We were just at the very beginning of our explorations into the Galaxy, and there were Things out there we didn’t understand and which didn’t understand us—or they didn’t care, or they simply saw us as a convenient source of raw materials. Over the course of the past fifty years, we’d taken special steps to screen our civilization’s background noise, and the AI navigators in our starships were designed to purge all data that might give a clue to the existence and location of Earth or Earth’s colonies if they encountered an alien ship or world.

A Qesh relativistic impactor, it was believed, could turn Earth’s entire crust molten. We did not want to have them or their Imperial buddies showing up on our doorstep in a bad mood.

The problem was, the barn door had been open for a bunch of years, and the horses had long since gotten loose. Radio and television signals were expanding into interstellar space at the rate of one light year per year, in a bubble now something like six hundred light years across. Technology researchers liked to insist that the useful information/noise ratio drops off to damned near zero only a couple of light years out; anyone out there listening for a juicy young prespaceflight civilization probably wouldn’t be able to pick our twentieth-century transmissions out of the interstellar white noise—but the kicker was the word probably. We just don’t know what’s possible; the EG mentions galactic civilizations out there that are on the order of 5 × 10

seconds old—that’s longer than Earth has been around as a planet. I don’t think it’s possible for us to say what such a civilization could or could not do.

But things get uglier when it comes to our pre-Protocol colonies. There are a lot of them out there, scattered across the sky from Sagittarius to Orion. The earliest was Chiron, of course, at Alpha Centauri A IV, founded in 2109. They’re all close enough to Earth to have signed the Protocol shortly after it was written, but there are plenty of colonies out there that for one reason or another have nothing to do with Earth or the Commonwealth. Many of them we don’t even have listed, and if we don’t know they exist, we can’t police them.

But if they were established before the year 2194, they probably still have navigational coordinates for Earth somewhere in their computer network. And someone with the technology to figure out how our computers work, sooner or later, would break the code and they might come hunting for us.

Our only recourse in that case was to go looking for them. If we could contact them and get them to agree to abide by the Protocol, great.

But if they didn’t … well, as Lewis had so eloquently put it, Send in the Marines.

“Now hear this, now hear this,” a voice said from the squad bay’s intercom speaker. “All hands prepare for one gravity acceleration in ten minutes, repeat, ten minutes. Secure all loose gear and reconfigure hab module spaces. That is all.”

“That was fast,” Dubois said.

“Yeah, but where the hell are we going?” I wanted to know. I looked at Lewis. “Your friend have any word on that?”

“Actually,” she said, “from what he said, hell is a pretty good description.”

In fact, though, our destination turned out to be Earth.

Most of the hab space on board an attack transport like the Clymer is dedicated to living space. She carries 1,300 Marines besides her normal complement of 210 officers and crew, and all of that humanity is packed into the rotating ring around her central spine, along with the galleys and mess halls, sick bay, lab spaces, rec and VR bays, life-support nanufactories, and gear lockers.

They didn’t tell us, of course. After doing a quick check to make sure anything loose was tied down or put away—Doobie’s hooch went into a refrigerated storage tank in an equipment locker forward—we strapped ourselves standing against the acceleration couches growing out of the aft bulkhead. Ten minutes later, we felt the hab wheel spinning down, and for a few moments we were in microgravity. I could hear a Marine down the line being noisily sick—there’s always at least one—but I stayed put until the Clymer lit her main torch.

There was an odd moment of disorientation, because where “down” had been along the curving outer floor of the hab wheel, now it was toward the aft bulkhead. The bulkhead had become the deck, and instead of standing up against our acceleration couches, now we were lying in them flat. The viewall was reprogrammed to show on what had been the deck. Under Plottel Drive, we were accelerating at a steady one gravity, but “down” was now aft, not out toward the rim of the wheel.

They let us get up, then, and we spent the next hour learning to walk again. We’d been at .38 Gs for two weeks.

I was half expecting Alcubierre Drive to kick in at any time, but hour followed hour and we continued our steady acceleration. Thirty-four hours later we were ordered to the couches once more, and again there was a brief period of microgravity as the Clymer ponderously turned end for end.

That gave us an idea of where we were headed, though. There’d still been a good chance that we were headed for Europa, as originally planned. At the moment, however, Jupiter and its moons were a good six astronomical units from Mars—call it 900 million kilometers. Accelerate at one gravity halfway from Mars to Europa, and we’d have reached the turnover point in something over forty-two hours. A thirty-four-hour turnover—I ran the numbers through my Cerebral Data Feed in-head processors a second time to be sure—meant we’d covered half the current distance to Earth.

Which meant we were on our way home, to Starport One.

Once we were backing down, thirty hours out from Earth, though, we received a download over the shipnet on a planet none of us had ever heard of.

Download

Commonwealth Planetary Ephemeris

Entry: Gliese 581 IV

“Bloodstar”

Star: Gliese 581, Bloodstar, Hell’s Star

Type M3V

M = .31 Sol; R = 0.29 Sol; L = .013 Sol; T = 3480

K

Coordinates: RA 15

19

26

; Dec -07

43’ 20”; D = 20.3 ly

Planet: Gliese 581 IV

Name: Gliese 581 IV, Gliese 581 g, Bloodworld, Salvation, Midgard

Type: Terrestrial/rocky; “superearth”

Mean orbital radius: 0.14601 AU; Orbital period: 36

13

29

17

Inclination: 0.0

; Rotational period: 36

13.56

(tide-locked with primary)

Mass: 2.488 x 10

g = 4.17 Earth; Equatorial Diameter: 28,444 km = 2.3 Earth

Mean planetary density: 5.372 g/cc = .973 Earth

Surface Gravity: 1.85 G

Surface temperature range: ~ -60

C [Nightside] to 50

C [Dayside]

Surface atmospheric pressure: ~152 x 10

kPa [1.52 Earth average]

Percentage atmospheric composition: O

19.6, N

75.5, Ne 1.15, Ar 0.58, CO 1.42; CO

1.01, SO

0.69; others<500 ppm

Age: 8.3 billion years

Biology: C, N, H, Na, S

, O, Br, H

O; mobile photolithoautotrophs in oxygenating atmosphere symbiotic with sessile chemoorganoheterotrophs and chemosynthetic lithovores in librational twilight zones.

Human Presence: The Salvation of Man colony established in 2181 in the west planetary librational zone. Salvation was founded by a Rejectionist offshoot of the Neoessene Messianist Temple as a literal purgatory for the cleansing of human sin. There has been no contact with the colony since its founding.

“Jesus Christ!” Lance Corporal Ron Kukowicz said, shaking his head as he got up out of his download couch. “Another bunch of fucking God-shouters.”

“Shit. You have something against God, Kook?” Sergeant Joy Leighton said, sneering.

“Not with God,” Kukowicz replied. “Just with God’s more fervent followers.”

“The download said they’re Rejectionists,” I pointed out. “Probably a bunch of aging neo-Luddites. No artificial lights. No AI. No nanufactories. No weapons. That’s about as harmless as you can get.”

“Don’t count on that harmless thing, Doc,” Staff Sergeant Larrold Thomason said. “If they’re living there they’ve got technology. And they know how to use it.”

“Yeah,” Private Gutierrez said. “You can tell ’cause they’re still alive!”

Thomason had a point. The planet variously called Salvation and Hell was a thoroughly nasty place, hot as blazes and with air that would poison you if you went outside without a mask.

We’d been lying inside our rack-tubes as we took the download feed—“racked out” as military slang puts it. That allowed for full immersion; the virtual reality feed that had come with the ephemeris data suggested that the numbers didn’t begin to do justice to the place. The recordings had been made by the colonizing expedition sixty-four years ago, so the only surface structures we’d seen had been some temporary habitat domes raised on a parched and rocky plateau. Bloodstar, the local sun, was a red hemisphere peeking above the horizon, swollen and red, with an apparent diameter over three times that of Sol seen from Earth. Everything was tinged with red—the sky, the clouds, and an oily-looking sea surging at the base of the plateau cliffs.

And the native life.

With the download complete, we were up and moving around the squad bay again. My legs and back were sore from yesterday, but I no longer felt like I was carrying an adult plus a large child on my back. Private Gerald Colby, at my orders, was wearing an exo-frame; they’d fused his broken tibia in sick bay an hour after his return from the Martian surface, but Dr. Francis had wanted him to go easy on the leg for a week or so to make sure the fix was good. That meant he wore the frame, a mobile exoskeleton of slender, jointed carbon-weave titaniplas rods strapped to the backs of his legs and up his spine—basically a stripped-down version of the heavier walker units we use for excursions on the surfaces of high-gravity worlds.

The rest of us had been working out in the bay’s small gym space, getting our full-gravity legs back, and taking g-shift converters, nanobots programmed to maintain bone calcium in low-G, and blood pressure in high-G. Marines on board an attack transport like the Clymer had a rigidly fixed daily routine which included a lot of exercise time on the Universals.

I shared the daily routine to a certain extent—they had me billeted with Second Platoon—but today I had the duty running sick call. It was nearly 0800, time for me to get my ass up there.

I rode the hab-ring car around the circumference to the Clymer’s med unit and checked in with Dr. Francis.

Clymer sported a ten-bed hospital and a fairly well appointed sick bay. In an emergency, we could grow new beds, of course, but the hospital only had one patient at the moment, a Navy rating from the Clymer’s engineering department with thermal burns from a blown plasma-fusion unit.

“Morning, Carlyle,” Dr. Francis said as I walked in. “You ready for Earthside liberty?”

“Sure am, sir. If we’re there long enough.”

“What do you mean?”

I shrugged. “Scuttlebutt says we’re headed out-system. And they just gave us a download on a colony world out in Libra.”

He laughed. “You know better than to believe scuttlebutt.”

“Yes, sir.” But why had they given us the feed on Bloodworld?

The doctor vanished into a back compartment, and I began seeing patients. Sick call was the time-honored practice where people on board ship lined up outside of sick bay to tell us their ills: colds and flu, sprains and strains, occasional hangovers and STDs. Once in a long while there was something interesting, but the Marines were by definition an insufferably healthy lot, and the real challenge of holding sick call was separating the rare genuine ailments from the smattering of crocs and malingerers.

My very first patient gave me pause, though. Roger Howell was a private from 3rd Platoon. His staff sergeant had sent him up. Symptoms were general listlessness, headache, mild nausea, low-grade fever of 38.2, lack of appetite, and a cough with nasal congestion.

It sounded like a cold. When I pinched the skin on his arm, the fold didn’t pop back, which suggested dehydration. “You been vomiting?” I asked. “Diarrhea?”

“No, Doc,” he replied. “But my head is really killing me.”

“You been hitting the hooch?” Those symptoms might also point to a hangover.

He managed a weak grin. “I wish!”

When I shined a light in his eyes, trying to look at his pupils, he flinched away. “What’s the matter?”

“Light hurts my head, Doc.”

I didn’t press it. Photophobia with a headache isn’t unusual. “You get migraines?”

“What’s that?”

“Really, really bad headaches. Maybe on just one side of your head, behind the eye. You might see flashes of light, and the pain can make you sick to your stomach.”

“Nah. Nothing like that. Look, I just thought you’d shoot me up with some nanomeds, y’know?”

I had a choice. I could call it a mild cold and have him force fluids to take care of the dehydration, or I could look deeper. There was a long list of more serious ailments that could cause those kinds of low-grade symptoms.

I pulled a hematocrit on him and got a 54. That’s right on the high edge of normal for males—again, consistent with mild dehydration. I took a throat swab for a culture, checked his blood pressure and heart rate—both normal—and decided on option one.

“You might be coming down with something,” I told him. I reached up on the shelf behind me and took down a bottle with eight small, white pills. “Take these for your head. Two every four hours, as needed.”

“Yeah? What are they?”

“APCs,” I told him. “Aspirin.”

“Shit. What about nanomeds?”

“Try these first. If you’re still hurting tomorrow, come to sick call again and maybe we can give you something stronger. In the meantime, I want you to drink a lot of water. Not coffee. Not soda. Water.”

“Shit, Doc! Aspirin?”

Yeah, aspirin. Corpsmen have been handing out APCs since the early twentieth century, when we didn’t even know why it worked; the stuff inhibits the body’s production of prostaglandins, among other things, which means it helps block pain transmission to the hypothalamus and switches off inflammation.

And the “something stronger” would be a concoction of acetaminophen, chlorpheniramine maleate, dextromethorphan, and phenylephrine hydrochloride—a pain reliever, an antihistamine, a cough suppressant, and a decongestant. Nanomedications can do a lot, but in the case of the old-fashioned common cold, the old-fashioned symptom-treating remedies do just as well and maybe better. We don’t automatically hand out the cold pills, though, because there are just too many creative things bored sailors and Marines can do to turn them into recreational drugs. You can’t get high on aspirin.

Howell looked disappointed, but he took the bottle and wandered out.

Next up was a Marine who was having trouble sleeping, even with VR sleep-feeds in his rack-tube.

Four hours later, I was getting ready to go to chow when a call came over the intercom. “Duty Corpsman to B Deck, eleven two. Duty Corpsman to B deck, eleven two. Emergency.”

I grabbed my kit and hightailed it. And I knew I had big trouble as soon as I walked into the berthing compartment.

It was Private Howell, screaming and in convulsions.

Chapter Three

DAMN IT! WHAT THE HELL HAD I MISSED?

Howell was on the deck in front of his rack-tube; the convulsions were hitting him in waves, and each time his muscles contracted he let loose a bellow that rang off the bulkheads. His face was bright red and sweating, his eyes wide open but apparently staring at nothing. A dozen Marines were gathered around him, trying to hold him down, trying to keep him from slamming his head against the deck. Someone had thought fast and jammed a rag into his mouth to keep him from biting through his own tongue.

I knelt beside him and felt for a pulse. Faster than two a second, and pounding.

The fastest way to derail convulsions is a shot of nano programmed to hit the brain’s limbic system and decouple the spasmodic neuronic output, a nanoneural suppression, or NNS. That’s the way we treat epileptic seizures. The trouble was, this wasn’t necessarily epilepsy, and messing with the brain, outside of relatively straightforward pain control, is not business as usual for a Corpsman.

I opened an in-head CDF channel. “Dr. Francis? I need you up here. B Deck, berthing compartment eleven two.”

“Already on my way, Carlyle. What do we have?”

“Twenty-year-old male in convulsions. Elevated heart and BP.” I hesitated. “He was at sick call this morning with symptoms of the flu.”

“Go ahead and initiate an NNS.”

“Aye, aye, sir.”

I pulled a spray injector from my kit and clicked in a plastic capsule of gray liquid, held the tip against Howell’s carotid, and fired it into his bloodstream. Elsewhere in my kit was an N-prog, a handheld device that used magnetic induction to program nanobots after they were inside the body. I switched it on and glanced at the screen.

What the hell? The device was picking up easily twice the dosage of ’bots, and they were already running a program. Not only that, they were recruiting the new ’bots, passing on their programming as the new ’bots flooded into Howell’s brain. On-screen, I could see a graphic representation of the nanotech war going on inside his brain—a haze of red dots and gray dots, with more and more of the gray switching to red as I watched.

And the seizures became more violent, horrifically so. Howell’s back arched so sharply, his hips thrust forward, I was afraid his spine was going to snap. With each thrust, he gave another bellow. The muscles were standing out on his neck like steel bars, his mouth wide open, and blood was streaming from his nose. This was not good. If I didn’t get the convulsions under control soon, he would have a massive stroke or a heart attack on the spot.

I punched in my code, then entered Program 9, holding the N-prog close to the side of his head. The remaining gray dots turned green and, slowly, slowly, the red dots began switching to green as well.

“C’mon! C’mon!” I breathed, watching the slow change in colors. Green ’bots meant they’d accepted the new program, which would guide them through the brain tissues to the limbic system and to the motor-control areas and the cerebellum, where they should start damping out the neural storm that was wracking Howell’s brain.

Damn it. I wanted to call it epilepsy, but it wasn’t, though it showed some of the same signs and symptoms. It looked as though Howell’s limbic system had just started firing off high-energy signals. The red nano was behind it, I suspected. Somehow, they appeared to be programmed to enter the limbic system and stimulate the neuron firings that had resulted in Howell’s bizarre seizure. I could see that the red ’bots were clustered in several particular spots deep within Howell’s brain—a region called the ventral tegemental area, or VTA, and another called the substantia nigra. I didn’t know what that meant; Corpsmen are given basic familiarization in brain anatomy, of course, but detailed brain chemistry is definitely a subject for specialists and expert AIs.

I needed to know what was going on in there chemically. I tapped out a new program code, setting it to affect just ten percent of the nanobots I’d just put into Howell’s brain.

Interstitial fluid—the liquid that fills the spaces between the body’s cells—is a witches’ brew of water filled with salts, amino acids and peptides, sugars, fatty acids, coenzymes, hormones, neurotransmitters, and waste products dumped by the cells. It’s not the same as blood or blood plasma; red cells, platelets, and plasma proteins can’t pass through the capillary walls, though certain kinds of white blood cells can squeeze through to fight infection. The exact composition depends on where in the body you’re measuring, but with nerve cells the interstitial fluid is where the chemical exchange takes place across a synapse, the gap between one nerve cell and another. I was telling the ’bots to begin directly sampling the mix of complex molecules floating among Howell’s neurons.

The answer came back as a long scrolling list of substances, but one formula by far outweighed all of the others: C

H

NO

. I had to look it up in my in-head reference library, and when I saw what it was I could have kicked myself.

Dopamine.

About then is when Dr. Francis arrived. “Make a hole!” one of the Marines barked, and the cluster of people around me and Howell scattered apart. I handed him my N-prog with the formula still showing on the screen.

“Shit,” was all he said when he read it.

Using my N-prog, he took over the programming of the nanobots, checking the progress of Program 9 first. There were definitely fewer of the red specks now, and a lot more of the green. In addition, some had switched over to orange, the ’bots engaged in sampling Howell’s cranial interstitial fluid.

The nanoneural suppression routine appeared to be working, once the green ’bots got a substantial upper hand over the red ’bots in numbers. Howell’s back was still arched, the muscular contractions were continuing, but they were decidedly weaker now, and expressing themselves as a long, steady quiver rather than the violent thrusting motions of a moment ago.

Dr. Francis was tapping in a new program code. “Neuroleptic intervention at the D2 receptors,” he told me. “It blocks dopamine.”

The ’bots clustered in Howell’s VTA were almost all green now, and the effect was spreading out through the motor region of his cerebral cortex and his cerebellum as well. The motor cortex is what plans and controls voluntary motor functions of the body—muscular movements, in other words. The cerebellum is the part of the brain at the very back and bottom of the organ that regulates the body’s muscular movements. It doesn’t initiate them, but it does help control them to fine-tune motor activity, timing, and coordination. Those parts of Howell’s brain had been completely out of control, causing all of his muscles to lock up in an involuntary, spasmodic seizure. As the motor-control regions relaxed, Howell’s body relaxed. His face sagged out of its rigid, openmouthed grimace, his fists unclenched, his spine eased into a more normal posture. Howell was panting now, but his eyes blinked, and he seemed to be aware of us now.

His eyes looked unusually dark.

“What happened, Private?” I asked him.

“I … dunno, Doc. I was just relaxing in my bunk, and wham! I don’t know what hit me.”

“How long have you been doing onan?” Dr. Francis asked, his voice level and matter-of-fact.

“Onan? I … ah … don’t know what you mean, sir.”

“Sure you do, son,” Francis replied. “You have enough dopamine in your system to trigger a hundred sexual orgasms. You were onanning and o-looping. Feels better than the real thing, eh?”

Of course, when the doctor said that it was all obvious. “Shit!” I said. “He’s addicted?”

“That’s one word for it,” Francis replied, studying the N-prog’s screen. “Ah. The dopamine levels are coming down. I think we’ve broken the monkey’s back.”

I only half heard him. I was in-head, opening up my personal library and downloading the entry on onan. I’d known this stuff, once, but it wasn’t the sort of thing you worked with every day, and I never thought about it.

Download, Ship’s Medical Library

“Onan,” “onanning”

From “O-nano,” a contraction for “orgasmic nano.”

Slang term referring to the use of programmed medical nano to affect the pleasure center of the brain directly in order to generate sexual orgasm. Nanobot programs can be directed to effect the release of massive amounts of dopamine in the brain, or to trigger spasmodic muscle contractions, or, more usually, both.

The term “onan” is a play on Onan, the name of a minor character in the Book of Genesis (q.v.).

Cute. I remembered it now. In the Jewish-Christian Bible, there’s the story of Onan, who dumped his semen on the floor rather than impregnate his dead brother’s wife, which apparently pissed Yahweh off so badly he struck Onan dead on the spot. For years, onanism was a synonym for masturbation, and carried with it the idea that God was going to throw a lightning bolt at you if you jacked or jilled off. What generation upon generation of relaxed but guilt-ridden teenagers afterward managed to miss was that the sin of Onan lay in his disobeying God—according to Jewish law he was supposed to father a son by his sister-in-law to preserve his brother’s bloodline. It had nothing to do with masturbation.

Today, of course, the so-called sin of Onan is long forgotten, but orgasmic nanotechnics are very much with us. You can program one-micron nanobots, you see, to go into the brain’s limbic system and trigger the neurochemical processes that result in sexual orgasm. Sometimes we do this deliberately, as a treatment for certain types of sexual dysfunction, but there’s also a thriving underground business in providing doses of sex-programmed nanobots that can go into the brain and stimulate an orgasm, and then do it again, and again, and again …

That part, programming the ’bots to give you one orgasm after another every second or two is known as o-looping, and it can be addictive—very highly so.

Not to mention dangerous.

It turns out that drugs like cocaine and amphetamines either trigger or mimic the release of dopamine, and they affect the same areas of the limbic system that light up during an orgasm—the VTA and the brain’s mesolimbic reward pathway. In fact, a brain scan taken during an orgasm shows a process ninety-five percent identical to a heroin rush. Drugs and orgasms hit the same part of the brain, and that’s what makes cocaine and other such drugs addictive.

That doesn’t mean sex is bad, of course. It’s natural, normal, and healthy. But deliberately and artificially overstimulating dopamine production can lead to an addiction requiring higher and higher dopamine levels to get the same kick as the dopamine receptors begin closing down. And the program Howell had been running, evidently, had involved overstimulation of the parts of the brain responsible for muscular contraction as well. It was a way to boost the orgasmic feeling, yeah, but it could have killed him too.

The curious thing is that dopamine doesn’t give you the feel-good kick itself. Dopamine is the hormone that makes you want—it’s the craving.

But it’s the flood of dopamine that makes a heroin addict want another hit.

And it drives our orgasmic cravings as well.

“I take it,” Dr. Francis said quietly, “that you didn’t check him for dope levels at sick call this morning.”

“No, sir.”

“Why not?”

“I didn’t see any need. It looked like a cold or maybe flu.”

“Did you look at his eyes?”

I glanced down at Howell’s face. In the harsh light from the overhead, his pupils were so widely dilated that his eyes looked unusually dark.

“No, sir. He was complaining that the light hurt his eyes.”

“Uh-huh. Addicts will do that, to hide their pupils. They’ll look everywhere except right at you. Did you notice that he happened to have a monster hard-on?”

“No, sir.” The long bulge at the crotch of Howell’s skinsuit was fading, but still hard to miss. Marines shipboard tend to wear nano-grown skinsuits like work utilities, since they’re disposable and Marines wear them under combat armor anyway. The things are pretty revealing, which doesn’t matter since the old American nudity taboos have pretty much gone the way of the dinosaur, and service men and women sleep and shower communally anyway.

His erection was painfully evident, even now. But, no, I hadn’t noticed. There’d been other things on my mind at the time besides Howell’s crotch.

“Get a stretcher team and get him down to sick bay,” Francis told me. “He should be okay, but we’ll need to follow up the neuroleptics, and he’ll need a complete scan to check for internal injury, electrolyte balance, and lactic-acid buildup. Once things are back in balance, we’ll do a flush on the ’bots, get them out of there.” He pinched Howell’s arm as I had earlier. “Dehydrated. When you get him to sick bay, put him on IV fluids. Think you can manage that?”

“Yes, sir.”

“Hey, Doc?” Howell said. His voice was weak, and it trembled a bit. “Am I in trouble?”

“You’re on report,” Dr. Francis told him, “if that’s what you mean. Misuse of nanomedical technology is damned dangerous. I imagine Captain Reichert is going to have words with you about damaging government property.”

“What government property?”

“You. Your body.”

I’d already used my in-head com link to call for a stretcher team. In the meantime, I helped Howell get up and into his bunk. The other Marines began dispersing, a little reluctantly. It had been quite a show.

And by the time we had him in sick bay, with an IV dripping Ringer’s lactate into his arm, we were sliding into Earth orbit, the tugs on their way out to haul us in and dock us with the Supra-Cayambe Starport Facility.

Later that afternoon, Lieutenant Commander Francis called me into his office. “Have a seat, Carlyle.”

“Yes, sir.”

“You missed some important shit with Howell, son.” He didn’t sound angry. He sounded disappointed, which was worse.

“I know that, sir.”

“Why?”

“I … no excuse, sir.”

“On board ship, our patients tend to be young and very, very healthy. Oh, you’ll get the occasional case of appendicitis or a sprained ankle or even a cold, but when one comes to you with vague symptoms like that, you need to consider the possibility that he did something to himself.

“Because our patients on board ship also tend to be very bored. They tend to be good at figuring out ways to subvert the system and apply technology to alleviate that boredom.”

I thought about Doobie and his lab-brewed hooch. “Yes, sir.”

“That’s especially true if he comes to you asking for a dose of nanomeds. Every technology can be misused in one way or another. It’s ridiculously easy for these kids to go on liberty and buy a handheld unit that can program ’bots to do damned near anything, just about. Onans are probably the most common. But they have them for programming a heroin rush, which is pretty much the same thing. Or cocaine. Or even, believe it or not, the feeling of contentment after a good meal.”

“Is that addictive, Doctor?”

“Can be. I saw one young enlisted woman a few years ago who was anorexic. She used an N-prog to feel full, like she’d just had a good meal, and stopped eating. We almost didn’t save her.”

“That’s just nuts, sir.”

“No, it’s just human. Humans do stupid things, or humans get screwed up in the head and that makes them to do stupid things.”

“Yes, sir.” I hesitated. “But—”

“But what?”

“I’m curious about Howell, sir. If he programmed the ’bots in his system to stimulate dopamine production … that’s just the craving, isn’t it? How did that cause the muscle spasms? And why did he go into convulsions? I didn’t give him any nanomeds this morning. Just aspirin.”

“Hm.” For a moment, he got a faraway look in his eyes, as though he were listening to something. “Do you know the term synaptic plasticity?”

“No, sir. I know what a synapse is.”

“The gap between one nerve cell and the next, yes. Synaptic plasticity is the tendency of the connection across the synapses to change in strength, either with use or with disuse. Among other things, it means the ability to change the quantity of neurotransmitters released into a synapse, and how well the next neuron in the chain responds to them. It’s an important factor in learning.”

“Okay …”

“Aspirin can affect synaptic plasticity. One of aspirin’s metabolic by-products, salicylate, acts on the NMDA receptors in cells, and that affects the flow of calcium ions across a neural synapse.”

At this point, Dr. Francis was way over my head. I had absolutely no idea what an NMDA receptor might be.

He must have sensed my confusion. “Don’t worry about it. My guess is Howell had a resident population of nanobots in his brain, programmed to give him an orgasm anytime he wanted, okay?”

I nodded.

“Dopamine is a neurotransmitter. One of the characteristics of neurotransmitters is you get a weakening effect each time you fire them.” He waved his hand in a descending series of peaks to illustrate. “You get this much of a jolt, then a little less, and a little less, like this. In an addiction, you need to boost the dosage of your drug of choice to get the same bang for your buck, right?”

“Yes, sir.” This was more familiar territory.

“Well, the same thing happens with dopamine. He might even have been going into withdrawal. Dopamine affects the same parts of the limbic system that heroin and cocaine hits.”

“Yeah. Headache. Runny nose. General aches and pains.”

“Symptoms like the flu,” Francis said. “Exactly. So he came to you to get you to prescribe a shot of nano, with the idea that more is better. He could reprogram what you gave him … or it looks like the nanobots he already had were set to reprogram anything new. You gave him aspirin instead. Maybe he took them back to the berthing compartment and downed them all, just hoping something would happen. The full chem workup we pulled on him this afternoon showed elevated salicylate levels.