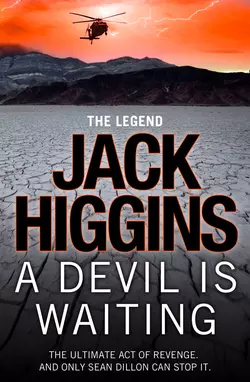

A Devil is Waiting

Jack Higgins

THE NEW HIGGINS HAS LANDED! The mesmerizing new Sean Dillon thriller of murder, terrorism and revenge from the Sunday Times bestselling author.Fresh from his mission in THE JUDAS GATE to seek out and eliminate one of al Qaeda’s most valued agents, a traitor responsible for countless soldiers’ deaths in Afghanistan, Sean Dillon is back in a blistering new adventure.The American President, on a planned visit to Europe, is entertained by the British Prime Minister on the terrace of the House of Commons. On the same day, London born Mullah Ali Salim makes an impassioned speech at Hyde Park Corner accusing the President of war crimes, objecting to his presence and offering a blessing to anyone who will assassinate him.Dillon, Major Ferguson and Daniel Holley are called into action, helped by a new recruit, Intelligence Corp Captain Sara Gideon, a war hero in the Afghan conflict, whose speciality is Pashta and Iranian. They quickly find themselves trying to handle a massive upsurge in terrorism from enemies near and far, all with links to al Qaeda.As a Sephardic Jew from a wealthy and ancient English family, Sara will find herself at the heart of the firestorm when she is swept into the heart of the terror organisation. Though their leader may be gone the threat remains as terrible as ever, and though Dillon and company may have won the first battle with al Qaeda, they will learn the war is far from over. A devil is indeed waiting and the assassination plan is only the beginning…

For Tessa-Gaye Coleman

Night & Day,

You Are the One

Where there is a sin

A devil is waiting

–IRISH PROVERB

Table of Contents

Title Page (#u5c6791ed-3800-57c0-9db8-0d88402bf7ca)

Dedication (#u0b288e4a-8fd0-5803-a38e-54c97200759d)

Epigraph (#u13b07126-b0b3-5e6a-9d69-566ea3e15726)

Brooklyn: London (#u2d6515ea-d7c1-5a97-80cd-2df0da6ae614)

Chapter 1 (#ufc81fffd-2caa-5e2a-83dd-8e25335158e5)

Washington: Afghanistan (#u8e07560d-9e3b-5e23-bb4a-4619db76a330)

Chapter 2 (#u31d0d9c0-1e5e-5a29-9a60-9e7c3971415b)

New York (#uc853226f-e8a4-513a-9c32-860a123ee93d)

Chapter 3 (#u1a3ce511-9d27-523a-b81e-d0c8c557e353)

London (#uf545f52f-768d-5898-93dc-8f5be6664487)

Chapter 4 (#ud5892986-8e23-5f66-95e3-5d831d93056c)

Chapter 5 (#u1a282d75-ccb0-5888-bbde-4b4f7d1edbf6)

Chapter 6 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 7 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 8 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 9 (#litres_trial_promo)

Pakistan: Peshawar, Afghanistan (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 10 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 11 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 12 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 13 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 14 (#litres_trial_promo)

Epilogue (#litres_trial_promo)

Also by Jack Higgins (#litres_trial_promo)

Copyright (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

BROOKLYN

1

It was late afternoon on Garrison Street, Brooklyn, as Daniel Holley sat at the wheel of an old Ford delivery truck, waiting for Dillon. There were parked vehicles, but little evidence of people.

Rain drove in across the East River, clouding his view of the coastal ships tied up to the pier that stretched ahead. A policeman emerged from an alley a few yards away, his uniform coat running with water, cap pulled down over his eyes. He banged on the truck with his nightstick.

Holley wound down the window. ‘Can I help you, Officer?’

‘I should imagine you could, you daft bastard,’ Sean Dillon told him. ‘Me being wet to the skin already.’

He scrambled in and Holley said, ‘Why the fancy dress? Are we going to a party?’

‘Of a sort. You see that decaying warehouse down there with the sign saying “Murphy & Son – Import-Export”?’

‘How could I miss it? What about it?’ Holley took out an old silver case, extracted two cigarettes, lit them with a Zippo, and passed one over. ‘Get your lips round that, you’re shaking like a leaf. What’s the gig?’

Dillon took a quick drag. ‘God help me, but that’s good. Ferguson called me from Washington and told me to check the place out, but not to do anything till I got a call from him.’ He glanced at his watch. ‘Which I’m expecting just about now.’

‘How kind of him to think of us. Brooklyn in weather like this is such a joy,’ Holley told him, and at that moment, Dillon’s Codex sounded.

He switched to speaker and General Charles Ferguson’s voice boomed out. ‘You’ve looked the place over, Dillon?’

‘As much as I could. Two cars outside it, that’s all. No sign of life.’

‘Well, life there undoubtedly is. I made an appointment by telephone for you, Daniel, with Patrick Murphy. Your name is Daniel Grimshaw, and you’re representing a Kosovo Muslim religious group seeking arms for defence purposes.’

‘And who exactly is Murphy and what’s it all about?’ Holley asked.

‘As you two well know, several dissident groups, all IRA in one way or another, have raised their ugly heads once again. The security services have managed to foil a number of potentially nasty incidents, but luck won’t always be on their side. You’ll remember the incident in Belfast not long ago when a bomb badly injured three policemen, one of whom lost his left arm. Since then another policeman has been killed by a car bomb.’

‘I heard about that,’ Dillon said.

‘Police officers are having to check under their cars again, just like in the bad old days, and some of them are finding explosive devices. We can’t have that. And there’s more. Attempts have started again to smuggle arms into Ulster. Last week, a trawler called the Amity tried to land a cargo on the County Down coast and was sighted by a Royal Navy gunboat. The crew did a runner and haven’t been caught, but I’ve firm evidence that the cargo of assorted weaponry originated with Murphy & Son.’

‘Was your source MI5?’

‘Good Lord, no. You know how much the security services hate us. The Prime Minister’s private army, getting to do whatever we want, as long as we have the Prime Minister’s warrant. At least that’s what they think. They just don’t appreciate how necessary our services are in today’s world—’

Holley cut in. ‘Especially when we shoot people for them.’

‘You know my attitude on that,’ Ferguson said.

‘Getting back to Murphy & Son, why not get the FBI to handle them? We are in New York, after all.’

‘I’d rather not bother our American cousins. This comes from Northern Ireland, and that’s our patch. Part of the UK.’

‘I’ve always thought that was part of the problem,’ Dillon said with a certain irony. ‘But never mind. What do you want us to do?’

‘Find out who ordered the bloody weapons in the first place, and I don’t want to hear any crap about some Irish American with a romantic notion about the gallant struggle for Irish freedom.’

‘Lean on them hard?’ Holley asked.

‘Daniel, they’re out to make a buck selling weapons that kill people.’ He was impatient now. ‘I couldn’t care less what happens to them.’

‘Wonderful,’ Dillon told him. ‘You’ve appointed us to be public executioners.’

‘It’s a bit late in the day to complain about that,’ Ferguson told him. ‘For both of you. What do they say in the IRA? Once in, never out?’

‘Funny,’ Holley said. ‘We thought that was your motto. But never mind. We’ll probably do your dirty work for you again. We usually do. How do you want them? Alive or dead?’

‘We’re at war, Daniel. Remember the four bastards who raped your young cousin to death in Belfast? They were all members of a terrorist organization. You shot them dead yourself. Are you telling me you regret what you did?’

‘Not for a moment. That’s the trouble.’

Dillon said, ‘Leave him alone, Charles, he’ll do what has to be done. Have you seen the President yet?’

‘No, I’m sitting here in the Hay-Adams with Harry Miller, looking out over the terrace at the White House, waiting for the limousine to deliver us to the Oval Office. We’ve prepared to brief him on the security for his visit to London on Friday, all twenty-four hours of it. As far as I can tell, we’ve got everything locked down, including his visit to Parliament and the luncheon reception on the terrace.’

‘Westminster Bridge to the left, the Embankment on the far side,’ Dillon said.

‘Yes, you’ve got experience with the terrace, haven’t you?’ Ferguson said. ‘Anyway, the Gulfstream is standing by, ready and waiting, so the moment I’m free, it’s off to New York for this UN reception at the Pierre. I want you two there, too.’

‘Any particular reason?’

‘I’ve got someone new joining the team from the Intelligence Corps.’

‘Really?’ Holley asked. ‘What have we got?’

‘Captain Sara Gideon, a brilliant linguist. Speaks fluent Pashtu, Arabic, and Iranian. Just what we’ve been needing.’

‘Is that all?’ Holley joked.

‘Ah, I was forgetting Hebrew.’

Dillon said, ‘You haven’t gone and recruited an Israeli, have you?’

‘That would be illegal, Dillon. No, she’s a Londoner. There have been Gideons around since the seventeenth century. I’m sure you’ve heard of the Gideon Bank. She inherited it. While she pursues her military agenda, her grandfather sits in for her as chairman of the board.’

‘You mean she’s one of those Gideons?’ Dillon said. ‘So why isn’t she married to some obliging millionaire, and what the hell is she doing in the army?’

‘Because at nineteen, she was at college in Jerusalem brushing up on her Hebrew before going up to Oxford when her parents visited her and were killed in a Hamas bus bombing.’

‘Ah-ha,’ Holley said. ‘So she chose Sandhurst instead of Oxford.’

‘Correct. And in the last nine years has served with the Intelligence Corps in Belfast, Bosnia, Kosovo, Iraq, and two tours in Afghanistan.’

‘Jesus, what in the hell is she after?’ Dillon said. ‘Is she seeking revenge, is she a war junkie, what?’

‘Roper’s just posted her full history, so you can read it for yourself.’

‘I wouldn’t miss it for anything,’ Dillon said.

‘Yes, I’m sure you’ll find it instructive, particularly the account of the nasty ambush near Abusan, where she took a bullet in the right thigh which left her with a permanent limp.’

‘All right, General, I surrender,’ Dillon said. ‘I’ll keep my big gob shut. I can’t wait to meet her in person.’

‘What do we do with her until you get to the Pierre?’ Holley asked.

‘Keep her happy. She was booking in at the Plaza after a flight from Arizona. There’s some secret base out there that the RAF are involved in, something to do with pilotless aircraft. She’ll be returning to London with us. She’s been on the staff of Colonel Hector Grant, our military attaché at the UN, and this will be her final appearance for him, so she’ll be in uniform.’

‘Does she know what she’s getting into with us?’

‘I’ve told Roper to brief her on everything – including you two and your rather murky pasts.’

‘You’re so kind,’ Holley said. ‘It’s a real privilege to know you.’

‘Oh, shut up,’ Ferguson told him. ‘Miller is very impressed with her, and I’m happy about the whole thing.’

‘Well, we’re happy if you’re happy,’ Dillon told him.

‘We’ve got to go now. Why don’t you two clear off and do something useful. I’ll see you tonight.’

Dillon walked away through the downpour, the nightstick in his right hand. He turned left into an alley and Holley waited for a few moments, then took from his pocket a crumpled Burberry rain hat in which a spring clip held a Colt .25. He eased it onto his head, got out of the truck, and walked quickly through the rain.

Dressed as he was as a beat cop, Dillon didn’t need to show any particular caution, tried a door, which opened to his touch, and passed into a decaying kitchen, a broken sink in one corner, cupboards on the peeling walls, and a half-open door that indicated a toilet.

‘Holy Mother of God,’ he said softly. ‘Whatever’s going on here, there can’t be money in it.’

He opened the far door, discovered a corridor dimly lit by a single lightbulb, and heard voices somewhere ahead. He started forward, still grasping the nightstick in his right hand, his left clutching a Walther PPK with a Carswell silencer in the capacious pocket of his storm coat.

The voices were raised now as if in argument and someone said, ‘Well, I think you’re a damn liar, so you’d better tell me the truth quickly, mister, or Ivan here will be breaking your right arm. You won’t be able to swim very far in the sewer after that, I’m afraid.’

There was no door, just an archway leading to a platform with iron stairs dropping down, and Dillon, peering out, saw a desk and two men confronting Holley, who was glancing wildly about him, or so it seemed. Dillon eased the Walther out of his pocket, stepped out, and started down the stairs.

When Holley had entered the warehouse he had found it dark and gloomy, a sad sort of place and crammed with a lot of rusting machinery. The roof seemed to be leaking, there were chain hoists here and there, and two old vans that had obviously seen better days were parked to one side. There was a light on further ahead, suspended from the ceiling over a desk with a couple of chairs, no sign of people, iron stairs descending from the platform above.

He called out, ‘Hello, is anyone there? I’ve got an appointment with Patrick Murphy.’

‘Would that be Mr Grimshaw?’ a voice called – Irish, not American.

The man who stepped into the light was middle-aged, with silver hair, and wore a dark suit over a turtleneck sweater. He produced a pack of cigarettes, shook one out, and lit it with an old lighter.

‘Yes, I’m Daniel Grimshaw,’ Holley said.

‘Then come away in.’

‘Thank you.’ Holley took a step forward, the rear door of the van on his right opened, and a man stepped out, a Makarov in his hand. He was badly in need of a shave, his dark unruly hair was at almost shoulder length, and he wore a bomber jacket. He moved in behind Holley and rammed the Makarov into his back.

‘Do you want me to kill him now?’ he asked in Russian, a language Holley understood.

‘Let’s hear what his game is first,’ Murphy told him in the same language.

‘Now, that’s what I like to hear,’ Holley said in Russian. ‘A sensible man.’

‘So you speak the lingo?’ Murphy was suddenly wary. ‘Arms for the Kosovans? Are the Serbs turning nasty again this year? Ivan here’s on their side, being Russian, but I’ll hear what you’ve got to say.’ This was said in English, but now he added in Russian, ‘Make sure he’s clean.’

Ivan’s hands explored Holley thoroughly, particularly between the legs, and Holley said, ‘It must be a big one you’re looking for.’

Ivan gave him a shove so violent that Holley went staggering, and his Burberry rain hat fell to the floor, disclosing the Colt, which the Russian picked up at once, throwing the hat across to the desk.

‘Now can I shoot him?’

Murphy pulled the Colt from the clip in the rain hat and examined it. ‘Very nice. I like it.’ He left the cap on the desk and slipped the Colt into his pocket.

Ivan said, ‘Only a pro would use a shooter like that.’

‘I know that, I’m not a fool. Show him where he’s going to end up if he doesn’t answer a few questions.’

Ivan leaned down, grasped a ring in the floor, and heaved back a trapdoor. There was the sound of running water, the smell of sewage.

Where the hell are you, Dillon? That was the only thought running through Holley’s mind. He glanced about him wildly, trying to act like a man in panic.

He said to Murphy, ‘What is this? What are you doing? I told you my name is Daniel Grimshaw.’

‘Well, I think you’re a damn liar, so you’d better tell me the truth quickly, mister, or Ivan here will be breaking your right arm. You won’t be able to swim very far in the sewer after that, I’m afraid.’

‘You’re making a big mistake.’

‘It’s not my mistake, my friend.’ Murphy shook his head and said to Ivan in Russian, ‘Break his arm.’

Dillon called in the same language, ‘I don’t think so,’ and shot Ivan in his gun hand. Ivan cried out, dropped the Makarov, and slumped to one knee beside the open sewer.

Murphy took the whole thing surprisingly calmly. Remembering that he’d slipped the Colt .25 into his pocket, he watched Holley pick up the Makarov and realized there was still a chance things might go his way.

‘I assume I’d be right in supposing that your fortunate arrival isn’t coincidental, Officer. I congratulate you on your performance – the NYPD would be proud of you.’

‘I used to be an actor,’ Dillon said. ‘But then I discovered the theatre of the street had more appeal. Audience guaranteed, you see, especially in Belfast.’

Murphy was immediately wary. ‘Ah, that theatre of the street? So which side did you play for? You couldn’t be IRA, not the both of you.’

‘Why not?’ Dillon asked.

‘Well, admittedly you’ve got an Ulster accent, but your friend here is English.’

‘Well, I’d say you’re a Dublin man myself,’ Dillon told him. ‘And admittedly there’s some strange people calling themselves IRA these days, and a world of difference between them. We, for example, are the Provo variety, and Mr Holley’s sainted mother being from Crossmaglen, the heart of what the British Army described as bandit country, his Yorkshire half doesn’t count.’

Murphy was beginning to look distinctly worried. ‘What do you want?’

Dillon smiled amiably. ‘For a start, let’s get that piece of shit on his feet. He’s a disgrace to the Russian Federation. Putin wouldn’t approve of him at all.’

Holley pulled Ivan up to stand on the edge of the sewage pit. Following Dillon’s lead, he said, ‘Is this where you want him, Dillon? He might fall in, you know.’

Dillon ignored him and said to Murphy, ‘I’m going to put a question to you. If you tell me the truth, I’ll let you live. Of course, if you turn out to have lied, I’ll have all the fuss of coming back and killing you, and that will annoy me very much, because I’m a busy man.’

Murphy laughed uneasily. ‘That’s a problem, I can see that, but how will you know?’

‘By proving to you I mean business.’ He turned to where Ivan stood swaying on the edge of the pit, pulled Holley out of the way, and kicked the Russian’s feet out from under him, sending him down with a cry into the fast-flowing sewage, to be swept away.

‘There he goes,’ Dillon said. ‘With any luck, he could end up in the river, but I doubt it.’

Murphy looked horrified. ‘What kind of a man are you?’

‘The stuff of nightmares, so don’t fug with me, Patrick,’ Dillon told him. ‘Last week a trawler named Amity was surprised by the Royal Navy as it attempted to land arms on the County Down coast. Our sources tell us the cargo originated with you. I’m not interested in Irish clubs or whoever raised funds over here. I want to know who ordered the cargo in Northern Ireland. Tell me that and you’re home free.’

For a moment, Murphy seemed unable to speak, and Holley said, ‘Are you trying to tell us you don’t know?’

Murphy seemed to swallow hard. ‘No. I know who it is. We do a lot of this kind of work, putting deals together for small African countries, people from the Eastern European bloc. None of the players are big fish. Lots of small agencies put things our way, stuff the big arms dealers won’t touch.’

‘So cut to the chase,’ Dillon told him.

‘I got a call from one of them. He said an Irish party was in town looking for assistance.’

‘And he turned up here?’

‘That’s right. Ulster accent, just like you. A quiet sort of man, around sixty-five, strong-looking, good face, greying hair. Used to being in charge, I’d say.’

Dillon said, ‘What was his name?’

‘I can only tell you what he called himself. Michael Flynn. Had a handling agent in Marseilles. The money was all paid into a holding company who provided the Amity with false papers, paid half a dozen thugs off the waterfront to crew it. Nothing you could trace, I promise you. My end came from Marseille by bank draft. It all came to nothing. I never heard from Flynn again, but from what I saw in the newspaper accounts, the Royal Navy only came on the Amity by chance. A bit unfortunate, that.’

Holley turned to Dillon. ‘Okay?’

‘It’ll have to be, won’t it?’

‘You mean I’m in the clear?’ Murphy asked.

‘So it would appear,’ Dillon told him. ‘Just try to cultivate a different class of friend in the future. That bastard Ivan was doing you no good at all.’

‘That’s bloody marvellous.’ Murphy hammered a fist on the desk and came round it. ‘You kept your word, Mr Dillon, and I’m not used to that, so I’ll tell you something else.’

Dillon smiled beautifully and turned to Holley. ‘See, Daniel, Patrick wants to unburden himself. Isn’t that nice?’

But even he couldn’t have expected what came next.

‘I was holding out on you on one thing. I actually did find out who Flynn really was. He wasn’t particularly nice to me, so I’ll tell you.’

Dillon wasn’t smiling now. ‘And how did you find that out?’

‘He called round to see me one evening and discovered his mobile hadn’t charged up properly. He was upset about it, because he had a fixed time to call somebody in Northern Ireland. He was agitated, so it was obviously important. He asked if he could use my landline.’

Dillon shook his head. ‘And you listened in on an extension.’

Murphy nodded. ‘He said it was Jack Kelly from New York, confirming that Operation Amity is a go. Arriving on the night of the eighth, landfall north beach at Dundrum Bay, close to St John’s Point.’

‘That’s County Down,’ Dillon said. ‘Anything else?’

‘I put the phone down. I didn’t want to get caught. I had the number checked on my phone bill and found it was to a phonebox in Belfast on the Falls Road.’

Holley said, ‘Whoever they are, they’re being very careful. That would have been untraceable.’ He paused. ‘Could Jack Kelly be who I think it is? It’s a common enough name in Ireland, God knows.’

‘You mean the Jack Kelly we ran up against, working for our old friend Jean Talbot?’

‘I know it doesn’t seem likely,’ Holley began, and Dillon cut in.

‘The same Jack Kelly who became an IRA volunteer at eighteen, was involved for over thirty years in the Troubles, and served on the Army Council?’

‘And never too happy about the peace process,’ Holley said. ‘So if it is him … I wonder what he’s up to.’

‘That’s for Ferguson and Roper to decide.’

‘Strange, us having a foot in both camps,’ Holley said. ‘How do you think that happened?’

‘Daniel, me boy, if I was of a religious turn of mind, I’d say God must have a purpose in mind for us, but for the life of me, I can’t imagine what it would be.’

‘Well, I’m damned if I can,’ Holley said. ‘Although I should imagine that the general will pay Kelly a call sooner rather than later.’

Dillon turned to Murphy. ‘Happy, are you, Patrick, now that you’ve come clean? I mean, as you did turn out to have lied, you must have thought I might take it the wrong way?’

‘Of course not, Mr Dillon,’ Murphy said, but there was a gathering alarm on his face.

‘Don’t worry,’ Dillon carried on. ‘You’ve done us a good turn. Although it would help the situation, restore mutual trust, you might say, if you produced my friend’s Colt .25. It doesn’t seem to be on the spring clip, which I can see quite clearly inside the rain hat on the desk there.’

Murphy managed to look astonished. ‘But that’s nonsense,’ he said, and then moved with lightning speed behind Holley, grabbed him by the collar, and produced the Colt.

‘I don’t want trouble, I just want out, but if I have to, I’ll kill your friend. So just drop that Walther into the sewage, and then we’ll walk to the door and I’ll get into my car and vanish. Otherwise, your friend’s a dead man.’

‘Now, we can’t have that, can we? Here we go, a perfectly good Walther down the toilet, in a manner of speaking.’ Dillon dropped it in.

Murphy pushed Holley towards the entrance, the Colt against his skull, and as Dillon trailed them, cried, ‘Stay back or I’ll drop him.’

Holley said to Murphy, ‘Hey, take it easy. Just be careful, all right? I hope you’re familiar with the Colt .25. If you don’t have the plus button on, those hollow-point cartridges’ll blow up in your face.’

They were just reaching the door. Murphy loosened his grip, a look of panic on his face, and fumbled at the weapon. Holley kicked out at him, caught him off guard, then ran away and ducked behind one of the old vans. Murphy fired after him reflexively and then, seeing that the Colt worked perfectly well, he realized he’d been had. He turned and ran out through the heavy rain into the courtyard.

Dillon had a replica of Holley’s Colt in a holder on his right ankle. He drew it now, ran to the entrance and fired at Murphy, who was trying to open the door of a green Lincoln. Murphy fired back wildly, then turned, ran across the road and up the stone steps leading to the walkway, the East River lapping below it. At the top, he hesitated, unsure of which way to go, turned, and found Dillon closing in, Holley behind.

‘No way out, Patrick. So have you told me the truth or not?’

‘Damn you,’ Murphy called, half-blinded by the heavy rain, and tried to take aim.

Dillon shot him twice in the heart, twisting him around, his third shot driving him over the low rail into the river. He reached the rail in time to see Murphy surface once, then roll over and disappear in the fast-running current.

Holley moved up to join him. ‘What was all that about? Sometimes you play games too much, Sean.’

‘Sure, and all I wanted was to make sure he was telling the truth. He’d lied at first – isn’t that a fact?’

‘So is the name really Jack Kelly?’

‘We’ll see, but for now, it’s time for the joys of the Plaza and our first meeting with the intriguing Captain Sara Gideon.’

‘Definitely something to look forward to,’ Holley said, and followed him down the steps.

At the same time they were driving away in their delivery truck, Patrick Murphy, choking and gasping, was swept under a pier two hundred yards away downstream. He drifted through the pilings, banged into stone steps with a railing, hauled himself out, and paused at the top, where there was a roofed shelter with a bench.

He sat down, shivering with cold, pulled off his soaking jacket, then his shirt. The bullet-proof vest he’d been wearing was the best on the market, even against hollow points. He ripped open the Velcro tabs, tossed the rest down into the river with his shirt, struggled back into his jacket, and walked through the rain to the warehouse.

He expected Dillon and Holley to be long gone and went straight inside and up to his office. He peeled off his jacket, pulled on an old sweater that was hanging behind the door, then lifted the carpet in the corner, revealing a floor safe, opened it, and removed a linen bag containing his mad money, twenty grand in large bills. He got a suitcase from the cupboard, put the money into it, and sat there thinking about the situation.

He had to get away for a while, the kind of place where he’d be swallowed up by the crowds. Vegas would be good, but he needed to cover his back, just in case he wanted to return to New York. He rang a number and, when a man replied, said, ‘I’m afraid I’ve got a problem, Mr Cagney.’

‘And what would that be?’

‘You sent me a nice piece of business. The man from Ulster, Michael Flynn.’

‘What’s happened?’

‘I had a client calling himself Grimshaw. He said he was seeking a consignment of weaponry, but the truth was he wanted information about the Amity and who’d been behind it.’

‘And did you tell him about Michael Flynn?’

‘Of course I did. He and another man with him killed Ivan and threatened to do the same to me if I didn’t tell them. Anyway, your client’s name isn’t Flynn, it’s Jack Kelly. He got careless using my phone one night.’

‘How unfortunate. Have you any idea who these people are?’

‘One posed as an NYPD officer, had an Ulster accent, and was called Dillon. The other was English, named Holley.’

‘They seem to have been rather careless with their names.’

‘That’s because I was supposed to end up dead, which I nearly was. Look, they claimed to be members of the Provisional IRA. I thought your client, Flynn or Kelly or whatever his name is, should know about that.’

Cagney said, ‘I appreciate your warning, Patrick. What do you intend to do now?’

‘Get the hell out of New York.’

‘Where can I contact you?’

‘I’ll let you know.’

Murphy replaced the phone, grabbed the suitcase, and went out. Within minutes, he was driving the undamaged car, a Ford sedan, out of the courtyard.

Shortly afterwards, Liam Cagney, a prosperous 60-year-old stockbroker by profession and Irish American to the core, was phoning Jack Kelly in Kilmartin, County Down, in Northern Ireland.

‘It’s Liam, Jack,’ he said when the receiver was picked up. ‘You’ve got a problem.’

‘And what would that be?’

‘Somebody’s asked Murphy about the Amity. Do the names Dillon and Holley mean anything to you?’

‘By God, they do. They’re both Provisional IRA renegades now working for Charles Ferguson and British Intelligence. What did Murphy tell them?’

‘He told me they killed his man Ivan and almost got him. He also heard you using your real name in a phone call.’

Kelly swore. ‘I knew that was dangerous, but I had no choice. So he’s on the run? I don’t like that. You never know what he might do.’

‘Don’t worry, it’s taken care of. He won’t be going anywhere.’

‘That’s good to know. You’ve served our cause well, Liam, and thanks for the information about Dillon and Holley. If they turn up here, we’ll be ready for them. It’s time someone sorted those two out. Take care, old friend.’

He was seated behind his desk in his office at Talbot Place, the great country house in County Down, where he was estate manager. He sat there thinking about it, then opened a drawer, took out an encrypted mobile phone, and punched in a number.

There was a delay, and he was about to ring off when a voice said, ‘Owen Rashid.’

‘This is Kelly, Owen. Sorry to bother you.’

In London, Rashid’s flat was huge and luxurious, and as he got rid of his tie, he walked to the windows overlooking Park Lane. ‘Is there a problem? Tell me.’

Which Kelly did. When he was finished, he said, ‘Sorry about this.’

‘Not your fault.’ Rashid poured himself a brandy. ‘Dillon and Holley. They’re bad news, but nothing I can’t deal with. My sources will tell me if they try anything.’

‘I’m always amazed by what you know, Owen.’

‘Not me, Jack, Al Qaeda. In spite of bin Laden’s death, it’s still a worldwide organization. We have people at every level, from a waiter serving lunch to a talkative senator in New York, to a disgruntled police chief in Pakistan, to a disenchanted government minister in some Arab state who hates corruption – or a humble gardener right here in London’s Hyde Park, watching me take my early-morning run and seeing who I’m with. In this wonderful age of the mobile phone, all they have to do is call in.’

‘And I’m not sure I like that,’ Kelly said.

‘No sane person would. Is Mrs Talbot still with you?’

‘She flew to London yesterday in the Beach Baron.’

‘I’ll look her up. As to Dillon, Holley, and Murphy, don’t worry, we’ll sort it. But it’d be a good idea if you called Abu and reported in.’

‘Where is he?’ Kelly demanded.

‘Waziristan, for all I know. He’s a mouthpiece, Jack, passing us our orders and receiving information in return. He could be living in London, but I doubt it.’

‘Why do you say that?’

‘He knows too much. They wouldn’t want to take the chance of him falling into the wrong hands. He’ll be sitting there, nice and safe in a mud hut with no running water or flush toilet, but the encrypted phone is all he needs. I would definitely give him a call, if I were you.’

‘Okay, I will,’ and Kelly switched off.

Owen stood under the awning on the terrace, rain dripping down, late-night Park Lane traffic below and Hyde Park in the darkness. He loved London and always had. Half-Welsh, thanks to the doctor’s daughter his father had met at Cambridge University, who had died in childbirth; half-Arab from one of the smaller Oman states.

Rubat had little to commend it except its oil. It didn’t have the interminable billions of the other states, but the wealth generated by Rashid Oil was enough to keep the small population happy. Sultan Ibrahim Rashid was chairman, and his nephew, Owen Rashid, was CEO, running the company from the Mayfair office and living in considerable comfort, especially as he’d managed to avoid marriage during his forty-five years.

His one mistake had been to get involved with Al Qaeda. He was not a jihadist and wasn’t interested in the religious side of things, but he’d reasoned that it would give him more muscle in the workplace and more power in the business world for Rashid Oil. He had been welcomed with open arms, but then found he had made a devil’s bargain, for he had to obey orders like everyone else.

Right now his task was to cultivate Jean Talbot, the chairman of Talbot International. Her son had been under Al Qaeda’s thumb – pure blackmail – until he died, and he had started by attending her son’s funeral. She had apparently known nothing about the connection, but Jack Kelly had, an old IRA hand who was itching to see some action again.

To meet Jean Talbot, he’d visited the Zion Gallery in Bond Street, where there was an exhibition of her art, and loitered until she’d turned up. A compliment on her famous portrait of her son had led to lunch at the Ivy.

The point of all this had only recently been made clear by his Al Qaeda masters. A single-track railway ran down from Saudi Arabia and ended up in Hazar next door to Rubat. It was called the Bacu. In modern times, it had been convenient to run pipes alongside the railway from the oil wells in southern Arabia, and over years of wheeler-dealing, the Bacu had ended up being owned by Talbot International.

Owen Rashid’s primary task was to persuade Jean Talbot to look favourably on the idea of extending the Bacu line through Rubat. The benefit to Yemen, a hotbed of Al Qaeda activity, was obvious: the possibility of instant access to the world’s biggest oil fields.

The truth was that he’d come to like Jean immensely, but that was just too bad. He had his orders, so he raised his glass and said, softly, ‘To you, Jean. Perhaps you’ll paint my portrait one day.’

At the same time in New York, Patrick Murphy was leaving his apartment and proceeding along the street to catch a cab. He hadn’t packed a suitcase. He’d decided he’d buy new clothes in Vegas, so he was just carrying the suitcase. He didn’t hear a thing, was just suddenly conscious of someone behind him and a needle point slicing into his clothes.

‘Just turn right into the next doorway.’ The voice was very calm.

Murphy did as he was told. ‘Please listen. If Cagney’s sent you, there’s no need for this. I’ve got money, lots of money. Just take it.’

The knife went right in under the ribs, finding the heart, killing him so quickly that he wasn’t even aware of the man picking up his suitcase and walking away, leaving him dead in the doorway.

WASHINGTON

2

A veteran of both Vietnam and the Secret Service, Blake Johnson had served a string of presidents as personal security adviser and was something of a White House institution. He’d known Ferguson and Miller for years.

Now he joined them in the rear of the limousine, closing the window that cut them off from the driver. ‘I can’t tell you how good it is to see you,’ he said. ‘Things are pretty rough for all of us these days. I wonder how the Prime Minister would cope if he didn’t have you.’

‘Oh, he’d manage, I’m sure,’ said Ferguson. ‘But my team is always ready to handle any situation with the appropriate response.’

‘Which usually means general mayhem,’ Harry Miller put in. Miller was the Prime Minister’s main troubleshooter and an under-secretary of state.

‘Well, you should know,’ Ferguson told Miller. ‘Mayhem is your general job description. When you’re not being used to frighten other Members of Parliament to death.’

‘A total exaggeration, as usual,’ Miller told Blake. ‘Anyway, I’m sure the President will be happy with our security arrangements for his brief visit to London. We wish it could be longer, but I know he’s expected in Paris and Berlin.’

Ferguson said, ‘I’m surprised he can find the time at all with everything going on in the Middle East and Africa.’

‘And Al Qaeda threatening worldwide spectaculars in capital cities,’ Miller put in. ‘In revenge for the death of bin Laden.’

‘We can’t just sit back and wait for things to happen,’ Ferguson said. ‘We’ve got to go in hard, find those responsible for running the show these days, and take them out.’

‘Well, I think you’ll find that’s exactly what the President wants to talk to you about,’ Blake said. ‘You know he supports action when necessary. But I think you’ll find he favours a more conciliatory approach where possible.’

Ferguson frowned. ‘What does that mean?’

Miller put a warning hand on Ferguson’s knee. ‘Let’s just see what the President says.’

The general pulled himself together. ‘Yes, of course, we must hear what the President has to say.’

In the Oval Office, the President and Blake faced Ferguson and Miller across a large coffee table. Clancy Smith, the President’s favourite Secret Service man, stood back, ever watchful.

‘London, Paris, Berlin, Brussels – it’s going to be quite a stretch in four days,’ said the President. ‘But I’m really looking forward to London, particularly the luncheon reception at Parliament.’

‘It’ll be a great day, Mr President,’ Ferguson said. ‘We’ve completely overhauled our security system for your visit. Major Miller is the coordinator.’

‘Yes, I’ve read your report. I couldn’t leave it in better hands. What I actually wanted to ask you about was your report of the inquiry into the Mirbat ambush in Afghanistan that cost us so many lives. It seems you were right when you supposed that British-born Muslims were fighting in the Taliban ranks.’

‘I’m afraid so.’

‘That’s bad enough in itself, but the fact that the man leading them was a decorated war hero, that he was chairman of one of the most respected arms corporations in the business – it defies belief.’

‘Talbot was a wild young man, hungry for war,’ Miller said. ‘Originally his supplying illegal arms to the Taliban across the border was strictly for kicks, but that led to Al Qaeda blackmailing him.’

‘As you can see from our report, he had Dillon’s bullet in him when he crashed his plane into the sea off the Irish coast,’ Ferguson shrugged. ‘An act of suicide to protect the family name.’

‘So his mother knew nothing about this Al Qaeda business?’

‘No. And she’s now chairman of Talbot International simply because she owns most of the shares.’

‘And in the world’s eyes, he just died in a tragic accident?’

Ferguson said, ‘Of course, Al Qaeda knows the truth, but it wouldn’t be to their benefit to admit to it. Nobody would believe such a story anyway.’

‘And thank God for that, and for the part you and your people played in bringing the affair to a successful conclusion, particularly your Sean Dillon and Daniel Holley. I see the Algerian foreign minister has given Holley a diplomatic passport.’

‘The Algerian government is just as disenchanted with Al Qaeda as we are,’ said Ferguson. ‘That passport makes him a very valuable asset.’

‘Who in his youth was a member of the Provisional IRA, as was Sean Dillon. Men who are the product of extreme violence tend perhaps to believe that a violent response is the only way forward.’

‘International terrorism is the scourge of our times, Mr President, powered by fanatics who insist on extreme views. It’s like a cancer that needs to be cut out to stop it spreading.’

The President said, ‘As you know, General, I believe in necessary force. But you can’t kill them all. The only way forward is to engage in dialogue with people with extreme views and attempt to reach a compromise. With Osama out of the way, I have great hopes for such an approach.’

‘I agree,’ Ferguson said. ‘But what about those who believe in the purity of violence and are willing to bomb the hell out of anyone who refuses to agree with them? Wouldn’t it be better to have people like Dillon and Holley stamp out such a fire before it spreads?’

‘Can such actions ever be condoned?’ the President asked.

Ferguson said, ‘In 1947, a brilliant commando leader named Otto Skorzeny was accused of war crimes because he had sent his men into action behind American lines wearing GI uniforms. Many of these men, when captured, were executed out of hand by the American forces.’

‘What’s your point?’

‘The chief witness for the defence was one of the most brilliant British Secret Service agents operating in occupied France. He admitted he’d been responsible for many operations in which his men had fought and killed German soldiers while wearing German uniforms. He also spoke of his superiors handing out such orders that could only be concluded by assassination. He told the court that if Skorzeny was guilty of a war crime, then he was just as guilty.’

There was a brief silence, and the President said, ‘What was the verdict?’

‘The case was thrown out of court. Skorzeny was acquitted of all charges.’

There was a long silence, and then the President said bleakly, ‘So what is the answer?’

‘That the kind of war we now face is a nasty business,’ Miller said. ‘And you can only survive if you play as dirty as the other side. That’s what twenty years of army service during the Irish Troubles taught me.’

The President sighed heavily. ‘I suppose I could have picked a better time to take up the highest office in the land, but here I am and, by God, I’ll see it through.’ He stood up and held out his hand. ‘Thank you for coming, gentlemen. We’ll meet again on Friday.’

Blake insisted on returning them to the hotel personally. In spite of the rain, there were a number of people outside the White House gates, mainly tourists by the look of them.

‘I told you how it would be,’ Blake said. ‘This is America, land of the free. The President has a difficult path to tread. We tried the Guantánamo Bay solution and received hate mail from all over the world. And there are even those who disapprove of the way we handled Osama.’

‘We know that, Blake. The trouble is that you can say what you want about universal freedom, individual liberty, the rule of law, but when you get into power, the intelligence services pass confidential dossiers across your desk full of information that proves how bloody awful the threat really is. More 9/11s have been foiled by the skin of our teeth than the public could imagine.’

‘And often because the Sean Dillons and Daniel Holleys of this world are prepared to act in the way they do,’ Harry Miller said, ‘and take responsibility for it in a way other people can’t.’

‘And thank God for it,’ Ferguson said. ‘You know, we’ve been good friends with the French Secret Service for some time now.’

Blake said, ‘I’m surprised. I thought you used to be at odds with them?’

‘Not any more. Their agents, some of whom have Algerian Muslim roots, infiltrate Al Qaeda training camps in Afghanistan and Pakistan, and the information gained has enabled the French to crush many terrorist cells in France since 9/11. But not only in France.’ Ferguson laughed grimly. ‘They call our capital city Londonistan – did you know that? From time to time, they pass over information to us of crazy plots to blow up Nelson’s Column, Tower Bridge, Harrods. You get the picture?’

‘I surely do,’ Blake said. ‘I suppose in Paris it’s the Eiffel Tower.’

‘I’d hate to be a Muslim living in Paris,’ Miller said. ‘I remember how the French reacted in the Algerian War. Nobody would want that.’

‘Al Qaeda would,’ Ferguson said as the limousine turned in to the hotel. ‘It would suit them down to the ground to return to the bad old days, so they could produce a few martyrs who’d been fixed up for sound.’

‘Dillon and Holley would seem tame by comparison,’ Miller said.

The limousine drove away with Blake and they watched it go. Harry Miller said, ‘What do you think?’

‘That I’d like a large bourbon on the rocks, but I’ll leave it until we’re on the Gulfstream. Let’s get our things and go,’ Ferguson said, and he led the way into the hotel.

When Captain Sara Gideon boarded the plane at Tucson for her flight to New York, she wore combat fatigues. This was America, where patriotism ruled and the military were received with enthusiasm, especially when the wearer was a good-looking young woman with cropped red hair. The shrapnel scar that slanted down from the hairline to just above the left eye made her even more interesting-looking. She was five foot six with high cheekbones in a calmly beautiful face that gave nothing away. It was as if she was saying: This is me, take me or leave me, I don’t give a damn. She had a window seat in first-class, and people glanced curiously as a flight attendant approached to offer her a glass of champagne.

‘Actually, I think that would be very nice,’ Sara Gideon told her.

‘Oh Lord, you’re English,’ the young woman said.

Sara gave her a smile of unexpected charm. ‘I’m afraid so. Is that all right? I mean, we’re all fighting the same war, aren’t we?’

The flight attendant was totally thrown. ‘No, no, I didn’t mean it like that. My older brother is a Marine, serving in Afghanistan. Sangin Province. I don’t suppose you’ve been there?’

‘I have, actually. The British Army was in Sangin for some time before the Marines took over.’

‘I’m so glad,’ the attendant said. ‘Let me get you your drink.’

She went away and Sara stood up, took her shoulder bag out of the locker, removed her laptop, and put it on the seat beside her. She replaced the shoulder bag and sat down as the flight attendant returned and gave her the champagne.

‘This Sangin place? It’s okay, isn’t it? I mean, Ron always says there’s not much going on.’

A good man, Ron, lying to his family so they wouldn’t worry about him. She’d been through two tours attached to an infantry battalion that suffered two hundred dead and wounded, herself one of them. But how could she tell that to this girl?

She drank her champagne down and handed the glass to her. ‘Don’t you worry. They’ve got a great base at Sangin. Showers, a shop, burgers and TV, everything. Ron will be fine, believe me.’

‘Oh, thank you so much.’ The girl was in tears.

‘Now you must excuse me. I’ve got work to do.’

The attendant departed, and Sara opened her laptop, feeling lousy about having to lie, and started to write her report. At the Arizona military base, location classified, she had been observing the new face of war: pilotless Reaper drones flying in Afghanistan and Pakistan but operated from Arizona, and targeting dozens of Taliban and Al Qaeda leaders.

It took her around two hours to complete. When she finished, she replaced the laptop in her shoulder bag. It had been a hell of an assignment – and where was it all going to end? It was like some mad Hollywood science-fiction movie, and yet it was all true.

Her head was splitting, so she found a couple of pills in her purse, swallowed them with some bottled water, and pushed the button for attention.

The young flight attendant appeared at once. ‘Anything I can get you?’

‘I’m going to try to sleep a little. I’d appreciate a blanket.’

‘Of course.’ The girl took one out of the locker and covered her with it as Sara tilted the seat back. ‘Sweet dreams.’

And how long since I’ve had one of those? Sara thought, and closed her eyes.

The dream followed, the same dream, the bad dream about the bad place. It had been a while since she’d had it, but it was here now and she was part of it, and it was so intensely real, like some old war movie, all in black and white, no colour there at all. It was the same strange bizarre experience of being an observer, watching the dream unfold but also taking part in it.

The reality had been simple enough. North from Sangin was a mud fort at a deserted village named Abusan. Deep in Taliban territory, it was used by the BRF – the Brigade Reconnaissance Force – a British special ops outfit made up of men from many regiments. The sort who would run straight into Taliban fire, guns blazing.

It was all perfectly simple. They’d got a badly wounded Taliban leader at Abusan, a top man who looked as if he might die on them and refused to speak English. No chance of a helicopter pick-up, two down already that week, thanks to new shoulder-held missiles from Iran. Headquarters in its wisdom had decided it was possible for the right vehicle to get through to Abusan under cover of darkness, and further decided that a fluent Pashtu speaker should go in with it, which was where Sara came in.

She reported as ordered, wearing an old sheepskin coat over combat fatigues, a Glock pistol in her right pocket with a couple of extra magazines, a black-and-white chequered headcloth wrapped around her face, loose ends falling across the shoulders, leaving only her eyes exposed.

The vehicle that picked her up in the compound was an old Sultan armoured reconnaissance car, typical of many such vehicles left behind by the Russians when they had vacated the country. Three banks of seats, a canvas top rolled back over the rear two, and a general-purpose machine gun mounted up front. It was painted in desert camouflage.

The three members of the BRF who met her looked like local tribesmen. Baggy old trousers, ragged sheepskins, and soiled headcloths like her own. They carried AK-47 rifles, were decidedly unshaven, and stank to high heaven.

One of them said, ‘Captain Gideon?’

‘That’s right. Who are you?’

‘We dispense with rank in our business, ma’am. I’m the sergeant in charge, but just call me Frank. This rogue on the machine gun is Alec, and Wally handles the wheel and radio. You can use the rear seat. You’ll find a box of RPGs to one side, just in case, ma’am.’

‘Sara will be fine, Frank,’ she told him, and climbed in as the engines started up and the trucks nosed out of the gates in procession.

‘Convoy to supply outposts in the Taliban areas,’ Frank told her. ‘Best done at night. We tag on behind, then branch off about fifteen miles up the road and head for Abusan, cross-country.’

‘Sounds fine to me.’ As she climbed into the seat, he said, ‘Have you done much of this kind of thing before?’ Another truck eased up behind them.

‘Belfast, Bosnia, Kosovo, Iraq, and this is my second tour in Afghanistan.’

‘Forgive me for asking.’ He climbed into the second bank of seats. ‘Get after them, Wally.’ He lit a cigarette and shivered. ‘It’s cold tonight.’

Which it was – bitter winter, with ice-cold rain in bursts and occasional flurries of wet snow. The canvas roof offered a certain protection, and Sara folded her arms, closed her eyes, and dozed.

She came awake with a start as Frank touched her shoulder. ‘We’re leaving the convoy soon and going off to the left.’

She glanced at her watch and was surprised to see that an hour had slipped by since leaving the compound. As she pulled herself together and sat up, a tremendous explosion blew the lead truck apart, the sudden glare lighting up the surrounding countryside.

‘Christ almighty,’ Frank said. ‘The bastards are ambushing us.’ As he spoke, the rear truck behind them exploded.

Passing through a defile at that part of the road, the convoy was completely bottled up and the light from the explosions showed a large number of Taliban advancing.

Guns opened up all along the length of the convoy, and Alec started to fire the machine gun as Wally called in on the radio. There was general mayhem now, the tribesmen crying out like banshees, firing as they ran, and several bullets struck the Sultan. Sara crouched to one side in the rear seat and fired her Glock very carefully, taking her time. Frank leaned over, opened the box of RPGs, loaded up and got to work, the first grenade he fired exploding into the advancing ranks. There was a hand grenade hurled in return that fell short, exploding, and Sara was struck by shrapnel just above her left eye.

She fell back, still clutching her Glock, and fired into the face of the bearded man who rushed out of the darkness, the hollow-point cartridges blowing him back, and the man behind him. There was blood in her eye, but she wiped it away with the end of her headcloth and rammed another clip into the butt of the Glock.

Wally, behind the wheel, was firing his AK over the side into the advancing ranks and suddenly cried out as a bullet caught him in the throat. Alec was standing up behind the machine gun, working it furiously from side to side, while Frank fired another grenade and then a third.

The headcloth pressed against the shrapnel wound stemmed the blood, and Sara fired calmly, making every shot count as the Taliban rushed in out of the darkness.

Frank, standing behind her to fire another grenade, cried out, staggered, dropped the launcher, and fell back against the seat, hit in his right side. Above him, Wally was blown backwards from his machine gun, vanishing over the side of the Sultan.

Sara pulled off her headcloth, explored Frank with her fingers until she found the hole in his shirt and the wound itself. She compressed her headcloth and held it firmly in place. As he opened his eyes, she reached for his hand.

His eyes flickered open, and she said, ‘Can you hear me?’ He nodded dimly. ‘Press hard until help comes.’

She scrambled up behind the machine gun, gripped the handles, and started to fire in short bursts at the advancing figures. The gun faltered, the magazine box empty. There weren’t as many out there now, but they were still coming. Very slowly, and in great pain, she took off the empty cartridge box and replaced it with the spare. There was blood in her eye, and she was more tired than she had ever been in her life.

She stood there, somehow indomitable in the light of the fires, with her red hair, and the blood on her face, and glanced down at Frank.

‘Are you still with me?’ He nodded slightly. ‘Good man.’

She reached for the machine gun again and was hit somewhere in the right leg so that she had to grab the handles to keep from falling over. There was no particular pain, which was common with gunshot wounds – the pain would come later. She heaved herself up.

A final group of Taliban was moving forward, and she started firing again, methodically sweeping away a whole line of them. Suddenly, they were all gone, fading into the darkness. She stood there, her leg starting to hurt.

There was a sound of helicopters approaching fast, the crackle of flames, the smell of battle, the cries of soldiers calling to one another as they came down the line of trucks. She was still gripping the handles of the machine gun, holding herself upright, but now she let go, wiped her bloody face with the back of her hand, and leaned down.

‘It’s over, Frank. Are you all right?’

He looked up at her, still clutching her headcloth to his body. ‘My God, I wouldn’t like to get on the wrong side of you, ma’am,’ he croaked.

She reached down, grabbing his other hand, filled with profound relief, and then she became aware of the worst pain she had ever experienced in her life, cried out, and, at that instant, found herself back in her seat on the plane to New York.

NEW YORK

3

The flight attendant was leaning over her anxiously.

‘Are you okay? You called out.’

‘Fine, just fine. A bad dream. I’ve been under a lot of stress lately. I think I’ll go to the restroom and freshen up.’

She moved along the aisle, limping slightly, a permanent fixture now, although it didn’t bother her unless she got overtired. She stood at the mirror, ran a comb through her hair, touched up what little make-up she wore, and smiled at herself.

‘No sad songs, Sara Gideon,’ she said. ‘We’ll go now and have a delicious martini, then think about tonight’s reception at the Pierre.’

At Kennedy, her diplomatic status passed her straight through, and she was at the Plaza just after five o’clock. The duty manager escorted her personally to her suite.

‘Would you have any news on General Ferguson’s time of arrival?’ she enquired.

‘Eight o’clock, but I believe that’s open, ma’am.’

‘And his two associates, Mr Dillon and Mr Holley?’

‘They booked into the hotel yesterday, but I think they’re out. I could check.’

‘No, leave it. I think I’ll rest. Would you be kind enough to see that no calls are put through, unless it’s the general?’

‘I’ll see to it, ma’am. Your suitcase was delivered this morning. You’ll find it in the bedroom. If you need any assistance, the housekeeper will be happy to oblige.’

He withdrew, and she didn’t bother to unpack. Instead of lying down, though, she put her laptop on the desk in the sitting room and sat there going over all the material sent to her by Major Giles Roper, whose burned and ravaged face had become as familiar to her as her own, this man who had once been one of the greatest bomb-disposal experts in the British Army, now reduced to life in a wheelchair.

It would be after eleven at night in London, but experience had taught her that if he was sleeping, it would be in his wheelchair anyway, in front of his computer bank, which was where she found him when she called him on Skype.

‘Giles, I’m at the Plaza and just in from Arizona. My report on Reaper drones will curl your hair.’

‘I look forward to reading it, Sara. You’re looking fit.’ They’d already become good friends. ‘Are you likely to enjoy tonight’s little soirée?’

‘There will be nothing little about it. No word from the general yet?’

‘I’ve spoken to him. He and Harry Miller have met with the President and should arrive at Kennedy around eight, if the weather holds. I was going to call you anyway. Your boss, Colonel Hector Grant – boss until midnight anyway – would appreciate you being there before eight.’

‘Happy to oblige him. I haven’t seen Dillon and Holley. They’re apparently out at the moment.’

‘Yes, they’re seeing to something for Ferguson.’

‘In New York? Is that legal?’

‘You wouldn’t want to know.’

She shook her head. ‘This whole business is the weirdest thing that’s ever happened to me. That General Charles Ferguson could take over my military career by Prime Minister’s warrant, which I never even knew existed, and make me a member of his private hit squad, which I’d always heard rumours about but never believed in.’

‘Well, it does.’

‘And I find myself in your hands, face-to-face on screen with a man who sits in a wheelchair, hair down to his shoulders, smokes cigarettes, constantly drinks whiskey, and seems to eat only bacon sandwiches at all hours, day and night.’

‘I can’t deny any of it.’

Tony Doyle, a black London Cockney and sergeant in the military police, appeared beside Roper with a mug of tea. He handed it to him and smiled at Sara. ‘Good to see you, ma’am.’

‘Tony, just go away.’ He laughed and went out.

‘It’s like a movie, Giles. I only see what you want me to. I have to take your word for everything.’

‘My dearest girl, all that I’ve told you about Holland Park is true, and you’ve got photos of everyone who works here, the details of their lives, their doings.’

‘So Dillon trying to blow up John Major and his Cabinet in London all those years ago, that’s true?’

‘And he got well paid for it.’

‘And Daniel Holley really was IRA and now he’s a millionaire and some sort of a diplomat for the Algerian foreign minister?’

‘Absolutely. He’s not just a pretty face in a Brioni suit, our Daniel.’

‘I didn’t say he was.’ She shrugged. ‘Obviously, he’s killed a few people.’

‘A lot of people, Sara, don’t kid yourself. And he’s too old for you. By the way, I went to hear your grandfather give a sermon.’

‘You what?’

‘I looked him up online. Rabbi Nathan Gideon, Emeritus Professor at London University, and famous for his sermons, so I went to hear one. I saw him at a synagogue in West Hampstead. Tony took me in the van. People were most kind, loaned me a yarmulke for my head and provided one for Tony, also. He thoroughly enjoyed the sermon. Human rights and what to do about its failures. I introduced myself and told him I worked for the Ministry of Defence and that we were going to be colleagues. He asked us back for tea. Whether this broke the Sabbath ruling, I’m not sure, but he did also provide some rather delicious biscuits.’

‘And this was at the Highfield Court house in Mayfair?’

‘That’s right. Tony was fascinated. Your grandfather gave him a book on Judaism, and he talks of nothing else.’

‘Are you completely mad?’

‘I sometimes think I am, but one thing is certain – Nathan Gideon is a wonderful man, and I’d be privileged to have his friendship.’

‘Is there anything else I should know?’

‘Yes, since you appear to be interested in Holley. His father was a hardline Protestant who didn’t like Catholics, but happened to fall in love with one who came from an equally hardline IRA family.’

‘So that explains his foot in both camps?’

‘Yes. And it led him as a young man to take refuge with the IRA, who sent him to a terrorist training camp in the Algerian desert, from which he emerged a thoroughly dangerous individual. So be warned. Anything else?’

‘Holland Park. What’s its purpose?’

‘To keep watch over terrorism. London is the dream destination for any jihadist. He can speak openly about intending to destroy our way of life and even involve himself in a plot or two.’

‘But the security services and the police are there to do something about that.’

‘Like arrest him and then discover that because of human rights laws, he can’t even be deported when he entered the country illegally?’

‘It’s hard to believe that.’

‘You’ll take worse things than that in your stride when you work for us. A couple of years ago, an Al Qaeda-based unit caused a terrible accident to happen to Harry Miller’s limousine on Park Lane. Unfortunately, Harry’s wife was using the car that morning. She and the chauffeur were killed.’

‘That’s terrible. What happened then?’

‘The bombmaker was traced. It was an IRA sleeper living in London. He was dying of cancer and fingered his Al Qaeda paymaster. After he died, Dillon called in a disposal team.’

‘Disposal team?’

‘A quick bullet solves most problems, but you need our personal undertaker, Mr Teague, and his associates to clean up and take the body away. A couple of hours later and it’s six pounds of grey ash.’

‘What happened to the paymaster?’ Sara asked.

‘Harry made that personal. Went round to the Al Qaeda guy’s house, shot him dead, and left Al Qaeda to clear up. I mean, they wouldn’t be likely to call in the police, would they?’

‘I wonder if I’m going to be able to cope with Holland Park.’

‘You’ll do fine. I’ve seen your file. There were at least twenty Taliban corpses around that Sultan.’

‘That was war.’

‘And so is this, sweetheart. By the way, I’m told you’ve been awarded a Military Cross for Abusan.’

She was reeling now. ‘But that can’t be true.’

‘The Intelligence Corps couldn’t resist putting their golden girl up for a medal for bravery. Of course, people like us don’t get medals, it’s too public, so Ferguson isn’t pleased. But don’t worry, you’ll get it. Just don’t expect a fuss.’

‘Giles, why don’t you go to hell and take Ferguson with you?’

‘I’ve been there, Sara, and it wasn’t good. Enjoy the Pierre, give my best to Sean, and watch it with Daniel.’

‘Just go, Giles.’ And he did.

She checked on the screen again, thoroughly annoyed, and brought up Daniel Holley. Medium height, brown hair that was rather long, the slight smile of a man who didn’t take his world too seriously and who looked ten years younger than he was.

In spite of the tattoos on his arms, common to convicts who’d spent time in the Lubyanka Prison, there was no sign of the killer on that handsome and rather attractive face, and yet that was exactly what he was. It was all there, his record in the field, meticulously put together by Giles Roper.

She went and unpacked, just the essentials since she was accompanying Ferguson to London, but she’d made sure to bring her dress uniform for tonight’s reception. The Yanks would be there, but they were friends. The Russians were another matter, and she had heard that Colonel Josef Lermov of Russian Military Intelligence, the GRU, head of station at the London Embassy, would be present. His book on international terrorism had become essential reading in military circles.

She hung up her uniform tunic with the medal ribbons, the neat skirt, shirt and tie, high-polished shoes, the dress cap. Good old khaki splendour. Just like graduating at Sandhurst, except for the medals. Ten years of her life.

‘Stop feeling sorry for yourself, Sara,’ she murmured, then went into the splendid bathroom and started to fill the tub.

At seven-thirty that evening, Dillon was sitting at a corner seat in the bar at the Pierre, dressed in a black velvet corduroy suit and enjoying a Bushmills whiskey, when Holley entered, wearing a beautifully tailored single-breasted suit of midnight blue, a snow-white shirt, and a blue striped tie.

‘Daniel, you look like a whiskey advert. You’ve excelled yourself. What about our new associate?’

Holley waved to the waiter and called for a vodka on crushed ice. ‘I tried to get through to her room, but the duty manager said she was resting. Roper’s put everything online, though.’

‘Is there much there?’

‘The usual identity card photos that make anyone, male or female, look like a prison officer. She has red hair.’

‘I look forward to that,’ Dillon said. ‘I love red hair.’

‘There was one unusual thing. Some video footage of her undergoing therapy for her wounded leg at Hadleigh Court.’

‘The army rehab centre?’ Dillon said.

‘I found it a bit disturbing.’

‘What’s her birth date?’

‘Fourth of September.’

‘Virgo.’ Dillon shook his head. ‘The only zodiac sign represented by a female. Still waters run deep with one of those, and you being the wrong sort of Leo, with Mars in opposition to Venus, you’ve got nothing but trouble on your plate where the ladies are concerned.’

‘Thanks very much, Sean, most helpful, particularly as I’m not in the market for a relationship.’

‘What did Roper have to say about Sara Gideon?’

‘She’s a bit bothered about being dragooned into Holland Park. And apparently she’s up for a Military Cross for Abusan. He read me the details.’

‘Impressive?’

‘You could say that. I had a call from Harry. They’re about to land, and they’ll see us here.’

‘And Sara Gideon?’

‘I’ve just checked at the Plaza desk. She left in a military vehicle.’

‘Seems a bit excessive, since we’re only a few blocks away.’

‘It seems her boss, this Colonel Hector Grant, was in the car.’

‘Well, there you are,’ Dillon told him. ‘Privileges of rank. Probably fancies her. Let’s drink up, go upstairs, and see if we can ruin his evening.’

The UN reception was all that you might expect: politicians from many countries, plus their military, the great and the good, and many familiar television faces. Waiters passed to and fro, the champagne flowed, and a four-piece band played music, helped out by an attractive vocalist.

A few couples were already taking a turn on the floor, among them Sara Gideon with a grey-haired colonel in British uniform who, at a couple or three inches over six feet, towered above her – at a guess, Colonel Hector Grant.

Holley said, ‘That red hair is fantastic.’

‘A lovely creature she is, to be sure.’ Dillon nodded. ‘I’d seize the day if I were you, while I go and embarrass Ferguson and Harry. I can see them over there queuing up with Josef Lermov, waiting their turn to shake hands with the ambassador.’

He walked away, and Holley stayed there, watching. Colonel Grant was smiling fondly, and she was smiling up at him with such charm that it touched the heart. They were dancing slowly, and the limp in her right leg was apparent, but only a little, and she laughed at something the colonel said.

At that moment, they turned and she was facing Holley. She stopped smiling, frowning a little as if she knew him and was surprised to see him there. The music finished. She reached up to speak to the colonel, then turned, glanced briefly at Holley, and moved towards the exit leading to the ladies’.

A voice said, ‘Heh, I bet that colonel’s more than just her boss. I love a girl in uniform, and that limp is kind of sexy. Maybe I could do myself some good here.’

There were two of them, middle-aged, well-dressed and arrogant, and already drunk. They made for the exit, drinking from their glasses as the music started up again, and Holley went after them.

At that moment, the corridor happened to be empty, just Sara Gideon approaching the restroom door, and the one who was doing all the talking put his glass down on a stand in front of a mirror, moved up fast behind her, and put a hand on her shoulder.

‘Hang on there, young lady. I know you soldier girls like a little action. We know just the place to take you.’

‘I don’t think so,’ she said as Holley approached behind them. ‘I think my friend wouldn’t like that.’

‘And which friend would that be?’ the second man asked.

Holley punched him very hard in the kidneys and, as he cried in pain and doubled over, kicked his feet from under him and stamped in the small of his back. The other man reached into his inside breast pocket and tried to withdraw what turned out to be a small pistol. Sara put her elbow in the man’s mouth, then twisted his wrist in entirely the wrong direction until he moaned with pain and dropped the weapon. Holley picked it up. ‘Two-shot derringer with hollow points. I didn’t know there were still any of these around. Very lethal.’ He smacked the man’s face. ‘What’s your name?’

‘Leo,’ the man gasped. ‘Don’t hurt me.’

‘The NYPD would just love to catch you with one of these. You’d be in a cell in Rikers tonight and, what’s worse, the showers in the morning. So I suggest you pick your friend up by the scruff of the neck and get out of here while I’m in a good mood.’

‘Anything you say, anything.’ Leo was terrified and reached down to his friend, hauling him up.

Holley said to Sara, ‘I get the impression you know who I am.’

‘Let’s say I’ve seen you on screen.’

‘Do you still need the loo?’

‘No, I think that can wait. I could do with a drink, but I’d prefer to go to the hotel bar for it and catch my breath.’

‘The bar it is, then.’ He offered her his arm, and, behind them, Leo managed to get his friend on his feet, and they lurched away.

They sat at a corner table and waited until a waiter brought a martini cocktail for her and a large vodka for him. She picked up her glass.

‘You don’t take prisoners, do you?’ she asked.

‘I could never see the point. The way you handled that guy with the derringer, though, suggests you could have managed quite well on your own.’

‘I have a black belt in aikido. Giles Roper warned me about you, you know.’

‘So you’re familiar with my wicked past?’

‘And Holland Park,’ she said. ‘And what goes on there. I’ve been given full access. I must say he’s very thorough.’

‘He’s that, all right.’

‘That horrible man.’ She sipped her martini. ‘He was afraid for his life. You frightened the hell out of him.’

‘I meant to, he deserved it.’ He took his vodka down in a quick swallow, Russian-style, and she watched him gravely, waiting for more. ‘Look, I was involved in a terrible incident years ago that makes it impossible for me to stand by and do nothing when I see a woman in trouble.’

‘Being familiar with your file, I understand why.’

‘Well, there you are, then,’ Holley said. ‘Anything else you’d like to know?’

‘I saw you watching me dancing with Colonel Grant, but you looked startled for some reason.’

He shrugged. ‘Just astonished at finding the best-looking woman I’d seen in a uniform for years.’

She smiled. ‘Why, Daniel, you certainly know how to please a lady.’

‘No, I don’t. I’ve never had much time for relationships, not in my line of work. Here today and possibly gone forever tomorrow, if you follow me. What about you?’

‘If you’ve immersed yourself in my career, you’ll know that the past ten years have been one bloody war after another. There was a chap I got close to in Bosnia who was killed by a Serb sniper. Then there was a major in Iraq who went the same way, courtesy of the Taliban.’

‘What about Afghanistan?’

‘With my Pashtu and Iranian, I travelled the country a lot.’ She smiled bleakly. ‘Death seemed to follow me around.’

‘Well, he must have thought he’d got you in his clutches at last on the road to Abusan.’ He smiled. ‘If somebody did decide to make a movie, they couldn’t do better than let you play yourself.’

‘You should be my agent, Daniel.’

‘That’s the second time you’ve called me by my first name. That’s got to mean something.’ He looked beyond her and saw Ferguson, Miller, and Dillon entering the bar, Colonel Josef Lermov with them. ‘Look who’s here.’

The Russian, instead of his uniform, was wearing an old tweed country suit, blue shirt, and brown woollen tie. He advanced on Holley and hugged him.

‘I must say you’re looking wonderful, Daniel.’ He looked down at Sara. ‘And this can only be the remarkable Captain Sara Gideon.’ He reached for her hand and kissed it. ‘A great honour and privilege, one soldier to another.’

‘Coming from the author of Total War, Colonel Lermov, I must say the privilege is all mine,’ she replied in perfect Russian.

He smiled. ‘So your reputation as an exceptional linguist speaks for itself. I’m impressed.’

Miller called for coffee and they all sat down, Ferguson beside Sara. ‘Been in the wars, my dear, so Security tells me? You were on camera.’

‘I’ve just seen it, Daniel,’ Dillon told Holley. ‘You were your normal totally brutal self, and served those bastards right.’

‘I agree,’ Lermov said. ‘Frankly, I’d like to sentence them to a year in Station Gorky in Siberia and see what they made of that. Unfortunately, this is not my parish.’

‘So what’s going to happen?’ Sara asked.

‘We’ve discussed it with management, and the gentlemen involved, having been suitably threatened and banned from ever visiting the hotel again, have departed with their tails between their legs.’

‘They can count themselves lucky,’ Holley said. ‘NYPD could have caused them real trouble over that derringer.’

‘Anyway, there it is,’ Ferguson said. ‘Welcome to the club, Sara, glad to have you on board. Congratulations to you, Dillon and Holley, for your handling of the Amity business. Though Murphy wasn’t shot to death in Brooklyn, as we thought. He must have been wearing some sort of body armour. He’s turned up close to his apartment, stabbed in the heart. Whoever he was dealing with obviously wanted his mouth shut.’

‘It must have been a hell of a good vest he was wearing when I shot him into the East River,’ Dillon said.

‘Yes, but the important thing was the Irish connection you turned up and our old friend Jack Kelly.’ Coffee was being passed around and he carried on, ‘You may be surprised that we’re talking about our highly illegal conduct in Brooklyn in front of Colonel Lermov here.’ He turned to Lermov. ‘Perhaps you’d like to make a point, Josef?’

‘Of course, Charles.’ He removed his spectacles and polished them with a handkerchief. ‘In the old Cold War days, we were sworn enemies, but in a world of international terrorism, we’d be fools not to help each other out. Putin agrees with me.’ He turned to Holley. ‘The Al Qaeda plot to assassinate Putin in Chechnya last year was foiled by information supplied by you, Daniel. He will never forget that.’

‘I wish he would,’ Holley said.

Ferguson ignored him. ‘So we have common interests, but never mind that now. I’ll be in touch with you sooner than you think, Josef, but for the moment, we’ll say good-bye. We’re all heading back to London tonight.’

He shook hands with Lermov, walked to the door, and they all followed, Holley taking Sara’s hand. ‘Is it always like this?’ she demanded.

‘Only most of the time,’ Dillon said, and turned to glance at them, smiling. ‘I see you two seem to have met somewhere.’

And they walked into the night.

LONDON

4

It was an hour before midnight, New York time, when Ferguson’s Gulfstream rose up through heavy rain to 40,000 feet and headed out into the Atlantic. Lacey and Parry, his usual RAF pilots, were at the controls – Sara had met them in the departure lounge and they’d indicated their approval. She was lying back in a red seat, and Parry passed her and spoke to Ferguson.

‘Definitely heavy winds in mid-Atlantic, General. Could take us seven hours at least. Will that be all right?’

‘It will have to be, Flight Lieutenant,’ Ferguson told him. ‘Carry on.’

Parry paused as he passed Sara and grinned. ‘He can be grumpy on occasion. Sorry we didn’t have a steward, but you’ll find anything you could want in the kitchen area. We’re very free and easy.’

He returned to the cockpit and she stretched out comfortably and listened to what was going on, for they had the screen on and were having a face-to-face with Roper.

‘I can see you in the back there, Sara,’ Roper called. ‘I warned you about Daniel.’

‘Enough of this erotic by-play,’ Ferguson growled, ‘and let’s get down to business. These different kinds of IRA dissidents, Giles, is it really possible for them to work together?’

‘I don’t see why not, but Dillon and Holley are the ones to ask. They’ve been there and done that, Dillon since he was 19. What’s your opinion, Sara? After all, the peace process was supposed to solve things, giving Sinn Fein seats at Stormont.’