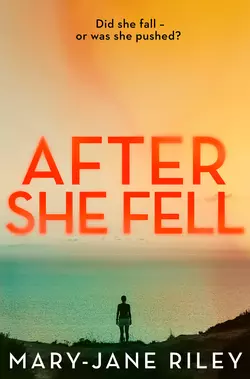

After She Fell: A haunting psychological thriller with a shocking twist

Mary-Jane Riley

A darkly compelling psychological thriller, full of twists and turns, perfect for fans of AFTER ANNA, HE SAID/SHE SAID and AFTER I’VE GONE.There are so many ways to fall…Catriona needs help. Her seventeen-year-old daughter Elena was found dead at the bottom of a cliff near her boarding school. The death has been ruled a suicide, but Catriona isn’t convinced.When her old friend, journalist Alex Devlin, arrives in Hallow’s Edge to investigate, she quickly finds that life at private boarding school The Drift isn’t as idyllic as the bucolic setting might suggest.Amidst a culture of drug-taking, bullying and tension between school and village, no one is quite who they seem to be, and there are several people who might have wanted Elena to fall…

AFTER SHE FELL

MARY-JANE RILEY

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

This is a work of fiction. Any references to real people, living or dead, real events, businesses, organizations and localities are intended only to give the fiction a sense of reality and authenticity. All names, characters, places and incidents are either the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously, and their resemblance, if any, to real-life counterparts is entirely coincidental.

Killer Reads

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.harpercollins.co.uk (http://www.harpercollins.co.uk)

First published by HarperCollinsPublishers 2016

Copyright © Mary-Jane Riley 2016

Mary-Jane Riley asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

Cover layout design by Micaela Alcaino © HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd 2017

Cover photograph © Shutterstock.com (http://www.Shutterstock.com)

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins e-books.

Ebook Edition © APRIL 2016 ISBN: 9780008181093

Version 2017-12-08

For my brothers: Patrick, Robert and Francis.

Table of Contents

Cover (#ubace2a03-0655-56be-80f5-2f75878d8589)

Title Page (#u4503c8e9-468b-5c88-9dcc-2c7266c0115b)

Copyright (#ub35f0a22-b472-5ca9-b5f6-75ccc0f59feb)

Dedication (#u7ad33507-546a-598b-9734-a459f91bdb44)

December (#u7f330652-ce4c-52ee-a2ee-da93be323f1f)

Five Months Later: Daily Courier (#u76dbf467-3e88-5eba-9a42-8f025140ad85)

Chapter 1 (#u4c8932f6-e4f3-584c-b293-8026f8cb1e2b)

Chapter 2 (#uebd48087-e816-5296-875c-b5dc079a466e)

Chapter 3: Elena (#u9ceb2e36-7b5e-5530-8e4f-d52134d74c32)

Chapter 4 (#ub0a329f9-ba92-5001-9e39-36289e2306c9)

Chapter 5 (#u9400414f-52d1-5a78-a017-f91ccbfb135b)

Chapter 6 (#ufbc31edc-4599-5873-bb05-d5fa99c6f08e)

Chapter 7 (#u601d8952-8e9a-5ec3-973d-3d9ff425a943)

Chapter 8: Elena (#u9fe437d6-7ad2-5e9f-ba4e-1d28309e040a)

Chapter 9 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 10 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 11 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 12 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 13: Elena (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 14 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 15 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 16 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 17: Elena (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 18 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 19 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 20 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 21: Elena (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 22 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 23 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 24: Elena (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 25 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 26 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 27: Elena (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 28: Elena (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 29 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 30 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 31: Elena (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 32 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 33 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 34: Elena (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 35 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 36: Elena (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 37 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 38 (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 39: Elena (#litres_trial_promo)

Chapter 40: Catriona (#litres_trial_promo)

Acknowledgements (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

Also by Mary-Jane Riley (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

DECEMBER (#u6c244bc9-dad8-5eb4-a1f8-e99bcb74d694)

Hunched against the wind that knifed through him, and trying to avoid the spray stinging his weathered cheeks even more, he didn’t see the body at first.

He had pulled his battered old overcoat tightly around himself, shifted his carrier bag of belongings from one hand to the other, watching as his feet sank into the sand, each footprint filling with water then draining away. He raised his head and, in the early grey half-light, saw what looked like seaweed in the ebb and flow of the sea on the shore. He squinted. Not seaweed, but hair, floating in the water. He moved closer. A girl, and a young one at that, pale face pummelled beyond all recognition and part of her scalp missing. Her body was at an awkward angle to her head – one eye gazing sightlessly up to the dark sky – lying like a broken puppet. Poor lass, he thought, poor, poor lass. He looked up and thought he could see a figure on top of the cliff where the end of the road had fallen into the sea. He thought he could see someone, but he wasn’t sure. A seagull wheeled and mewled above him.

FIVE MONTHS LATER (#u6c244bc9-dad8-5eb4-a1f8-e99bcb74d694)

Daily Courier (#u6c244bc9-dad8-5eb4-a1f8-e99bcb74d694)

The daughter of a top politician took her own life after a history of depression and eating disorders, an inquest has heard.

The body of Elena Devonshire, the 17-year-old daughter of MEP Catriona Devonshire, was found in December at the foot of cliffs in Hallow’s Edge, North Norfolk, close to the school where she was a pupil.

A post-mortem examination revealed Elena died from multiple injuries consistent with a fall. Toxicology tests also showed a small quantity of cannabis in her system.

Yesterday’s inquest was told that, between the ages of fourteen and sixteen, Elena had suffered from depression, coupled with an eating disorder.

PC Vic Spring from Norfolk Police said a text from the teenager to her mother had been discovered on the teenager’s phone, found in her bedroom at The Drift – the private boarding school she attended – which ‘strongly indicated’ she had intended taking her own life. ‘There was no suspicious evidence leading to her death and no neglect of care exhibited by the staff at her school,’ he said.

Norfolk coroner, Sarah Knight, recorded a verdict of suicide.

After the inquest Mrs Devonshire said, although her daughter had been treated for depression and an eating disorder in the past, she had since made a full recovery. ‘My daughter was looking forward to getting home for Christmas,’ she said.

Ingrid Farrar, one of two head teachers at the co-educational school, said, ‘Our hearts go out to Mrs Devonshire and Elena’s stepfather, Mark Munro, at this difficult time. The school has a robust pastoral care policy and we are more than satisfied we helped Elena all we could.’

Catriona Devonshire was elected to the European Parliament for the South and East on an independent ticket eighteen months ago. She has already proved an able campaigner in the area of human rights.

CHAPTER 1 (#u6c244bc9-dad8-5eb4-a1f8-e99bcb74d694)

May

Despite the heat of the day, the window of the room was closed tight. Alex Devlin’s sister sat in her chair, staring through the glass. Outside, trusted patients were standing around smoking or sitting on the benches at the edges of the grass. One woman was talking animatedly to her nurse, who nodded, looking into the middle distance. The garden was lovely at this time of year – the lawn lush and green, roses blooming in the sunshine, the silver birches coming into full leaf, and Alex could almost smell the honeysuckle that climbed through the hedge of bamboo at one end of the garden. Birds chattered and hopped from branch to bird table and back to branch again. She badly wanted to be out there, away from the stifling air and atmosphere of Sasha’s room.

‘Sash? Would you like me to take you into the garden? It’s a beautiful day.’

Alex had been in the room for fifteen minutes and so far her sister hadn’t said a word. She damped down a sigh. It was really hard going to keep on chatting when the person you were talking to didn’t respond in any way at all. Not a sign she’d heard anything Alex had said. Not a flicker of expression.

She looked around the room. It was, considering the circumstances, a homely place, decorated in soft pastels. The bed had her sister’s own patchwork bedspread thrown over it. There were two pictures on the walls, both with the glass removed, of course: the first, a scene of beach huts and seagulls; the second, a small photograph of Sasha’s twins forever caught in a time of sunshine and ice creams. The shelves were full of Sasha’s favourite books, from Enid Blyton to Kate Atkinson. Did her sister need anything? The soap she’d bought last time was still in its wrapping. Not that, anyway.

She tried again. ‘Love, it’s gorgeous out there and really, really warm, even for late May. You remember how you love the summer?’

‘Harry and Millie loved the summer.’ A tear trickled down Sasha’s face.

Alex’s heart twisted, pain blooming in her chest. Words, at last, but words that contained so much hurt. She went to hug her sister, but Sasha pushed her away.

‘I want you to go now,’ she snarled.

She had to try. ‘Sasha, please, let’s go outside. Have a walk. Feel the sun on our faces. Enjoy being together, if only for a few minutes.’

‘Enjoy?’ Sasha’s voice was low; she didn’t move from her position at the window. ‘I can’t enjoy anything, Alex. You know that. I’ve got nothing left. Millie. Harry. Jez. Nothing.’ She gave a sigh that shook her whole body. ‘Please go.’ Her voice was the merest whisper.

‘Haven’t you punished yourself enough, Sasha?’ pleaded Alex. ‘Let’s go outside. Just this once.’

Silence. Sasha kept staring through the window, her shoulders tense. Alex knew there would be nothing more from her today. She bent down and kissed her sister’s cold cheek. ‘Bye, Sash. I’ll come again as soon as I can.’

Nothing.

Alex shut the door quietly and leaned against it. Was this a better visit than last time? At least, Sasha had spoken to her. Most of the time when she came to see her, Sasha didn’t say anything, so she supposed even a few bitter words were progress of a sort. But she could hardly bear the pain that was almost tattooed on Sasha’s eyes. Alex couldn’t imagine what it must be like to live inside her sister’s head, to know that you had killed your own children. She thought of her own boy – eighteen years old but still her boy – and how he had coped with the last few years. She was proud of him. She couldn’t even contemplate life without him.

‘Ah, Alex, I wanted to catch you before you left.’ Heather McNulty, the matron of the unit, bustled along the corridor towards her. A well-groomed woman a little older than Alex, Heather always had a cheerful expression on her face even though she was surrounded by unresponsive or troublesome patients. She didn’t wear a uniform, and today had a long skirt made of some sort of floaty material festooned with printed roses, teamed with a crisp white shirt. Alex liked the fact the staff wore their own clothes; it made it less of an institution, and made her feel better about Sasha being incarcerated there on the orders of the judge. Two years before, the judge, old and wrinkled but with a kind-looking face, had decreed that Sasha had suffered enough: for more than fifteen years she had lived with the knowledge that she had been responsible for drowning her own 4-year-old twins. But she would have to have treatment in a secure unit. Jez, Sasha’s police officer husband, hadn’t been so lucky to escape the wrath of the judge. He was jailed for weaving a tissue of lies and misinformation about what had happened on the fateful night, and for being responsible for the imprisonment of two people who had been wrongly convicted of murder. So, yes, Alex was grateful for Leacher’s House. A secure unit it might be, but it could have been such a lot worse.

Alex frowned and rubbed her forehead. ‘Is everything all right with Sasha? She hasn’t started to self-harm again has she?’

‘Not exactly. I only need to have a chat. Come with me to the office.’

Alex followed Heather down the corridor, transported back more than a quarter of a century to when she was a schoolgirl following the straight back and sharp shoulders of her head teacher to the office for a telling-off. She felt that same degree of apprehension now: stomach knotted, wanting to drag her feet, wanting to get it over with.

‘So, sit down, Alex.’

Alex sat.

Heather went round to the other side of her desk and neatly lowered herself into the chair, folding her hands in front of her. She took a deep breath. Fear rose in Alex’s throat.

‘Is Sasha ill?’ She laughed nervously. Shut up Alex. ‘I mean, more ill than normal?’

Heather clasped her hands together. ‘Sasha has not been responding to treatment as well as we would like.’

‘What do you mean?’

A small frown crossed Heather’s face before the sympathetic smile was in place once more. ‘Sasha has been suffering from, um, delusions, lately.’

Alex blinked. ‘Delusions?’

‘Sasha believes she murdered Jackie Wood.’ Heather’s voice was kind.

Alex caught her breath. Jackie Wood was the woman who had been imprisoned for fifteen years for what was then thought to have been her involvement in the murder of Sasha’s children. It was only after she was let out on a technicality that the truth about the children’s deaths began to unfold, and Sasha finally confessed. But before Jackie Wood could be exonerated she was murdered, and the murderer had never been found. There had been a time when Alex had wondered whether her sister had killed Jackie Wood, but now she refused to entertain that thought.

Heather was still talking. ‘And obviously, we don’t want her to regress further, so we feel – that is, her team feel – she needs a different regime.’

‘Regime? What does that mean? And what sort of treatment? She can stay here in Leacher’s House, can’t she?’ Alex heard her voice rise. Oh God, oh God. She had visions of her sister being force-fed drugs by a Nurse Ratched figure or being forced to undergo ECT and Sasha becoming a shell, losing her personality, any sense of identity and—

‘Alex.’ Heather’s voice was firm. ‘I can see the panic in your face. Sasha is in good hands.’

‘But she will get better, won’t she?’

‘As I say, she is in good hands. The best possible. Please don’t worry; this sort of review is part of an ongoing process, and this is the twenty-first century, you know.’ Her face was kind. ‘Things are very different now.’ Heather stood. The meeting was clearly over. ‘You will be kept informed every step of the way.’

Alex stood. ‘Thank you,’ she said. Though for what, she wasn’t quite sure.

Review. Ongoing process. Regime. Jackie Wood. The words went round and round in Alex’s head as she pushed open the door and went out into the fresh, warm air, trying to shake off the chemical floral smell of Leacher’s House. She took a few deep breaths to steady herself. The sun was bright and the sky was blue, like a children’s painting. A perfect day. It was at times like these Alex found herself thinking of Harry: drowned by Sasha, brought to the shore by Jez. She thought of Millie who’d been taken away by the North Sea, and wondered if her body would ever be found. She still looked for Millie in crowds of young people, just in case.

Walking to the car park, she glanced back to see Sasha still sitting, still in the same position, still looking. She had always known her sister was not right and had needed proper help, but over the years she had been so blinded by her grief over the twins and the guilt she carried around at having an affair with the man who was imprisoned for killing Harry and Millie that she hadn’t been able to see beyond her own feelings. She had let Sasha down. Now she was trying to make up for it.

Alex raised her hand and waved, and was rewarded by the tiniest of finger movements. The nearest she had come to a wave for a very long time. Love for her poor broken sister swelled in her chest. She couldn’t let Sasha down again.

CHAPTER 2 (#u6c244bc9-dad8-5eb4-a1f8-e99bcb74d694)

The small mews house was a stone’s throw away from Harrods and the moneyed part of Knightsbridge. Alex could smell the cash as she found the right address. Blood-red door flanked by two rose trees in square pots. The petals were a blush pink and when Alex bent to smell them they gave off a cloying scent. The woodwork of the windows was in the same blood-red, as were the garage doors. The other houses in the row had either the red or dark green wood. Three storeys of perfection. Not bad for a set of buildings that was once a line of stables.

She knocked on the door.

The woman who answered looked as though she hadn’t slept for days. Heavy make-up couldn’t disguise her grey skin and sunken eyes, the black shadows underneath. She was dressed in jeans and a tee-shirt, diamond studs in her ears. Her perfume was expensive though overlaid with the smell of cigarette smoke.

‘Alex. Thank you for coming.’ The woman held onto the door as if by letting go she would fall down.

‘Cat,’ Alex said, reaching out to hug the woman who had once been her closest friend. ‘Of course I came.’

There had been no question about her going to Grosvenor Place Mews, even though she should have been hunting for stories, chasing commissions, chasing the cash.

She’d been in her news editor’s office pitching an idea for looking into a story about people being trafficked for illegal organ removal when he’d leaned back in his chair and looked at her from under unruly eyebrows. ‘I had a call this morning.’

‘Right,’ said Alex, not sure what that had to do with her.

‘Someone looking for you.’

‘Right.’ Typical Bud, he liked to think he was being mysterious, building up the tension – all it succeeded in doing was to make her impatient. Even so, she wasn’t going to give him the satisfaction of winning the game. ‘Anyway, Bud, about the organ removal story. It’s early days, but I heard from a reasonably reliable source—’

‘Don’t you want to know who it was?’

She looked at him: sitting in his cubbyhole in a dark corner of the office ‘so the bean counters can’t find me’; overweight, paunch almost resting on the desk. Computer pushed right to the back; the front of the desk piled high with editions of The Post going back years. And a higgledy-piggledy heap of press releases, cuttings, jottings, and God knows what. Coffee mugs littered the desk too, dark slime at the bottom of some. All Bud Evans needed to complete the ‘I’m an old-fashioned editor and I don’t take any nonsense’ look was a green eyeshade. Bloody rogue. But he’d been good to her: employing her when nobody else would after it had all come out about Sasha and she felt she needed to leave Sole Bay and lose herself in the anonymity of London. Having taken her under his wing once in her life – when she was a raw recruit – Bud had come to her rescue again. She owed him.

She grinned. ‘What if I said no?’

He made a gruff noise, somewhere between a snort and a cough. ‘You want to know. Of course you do.’

She rolled her eyes. ‘Go on then.’

‘A Member of the European Parliament,’ he said with a flourish. ‘Asking for you personally. Said she was an old friend of yours. Didn’t know you moved in such illustrious circles. Or have you gone native on me? Hobnobbing with the enemy?’

‘An MEP?’ Her heart began to beat faster. There was only one such person who could be asking for her personally: Catriona Devonshire.

She and Cat Devonshire had been inseparable through primary school and on into high school. Cat had been the sister to her that Sasha hadn’t been. They had shared secrets, problems, worries. They swore to look out for each other forever. They went their separate ways to uni, but they still kept in touch. When Gus came along, Cat made no judgements, but left her new husband, Patrick, at home, put her fledgling political career on hold and came to stay. Her presence had been a soothing balm on Alex’s soul.

And then the twins had been murdered and Alex’s life had been consumed by guilt and the need to look after Sasha. Her world began to narrow; she had no time, no room in her head for anyone but Sasha, so she excluded everything and everyone else from her life, including Cat. And when Cat’s daughter, Elena, had been born, a few short weeks later, Alex had broken off all contact.

‘But I want you here,’ Cat had pleaded. ‘I want you to be Elena’s godmother.’

‘Cat,’ Alex kept her tone deliberately without emotion, ‘you have your family. Your career. Any association with me would spoil both those things. We need to put distance between us.’

‘But Al—’

‘No, Cat. I have to be with my family.’ And then the sentence that had sounded the death knell on their friendship: ‘I don’t need you any more, Cat. I’ve got Sasha to look after. Gus. They are my family. They are the ones I need to look after now.’ It had almost killed her to say the words, to know that she was losing Cat’s friendship, but she didn’t want the events of her life to taint Cat’s. It had to be done.

And Cat had removed herself from Alex’s life.

But Alex had followed Cat’s career. Had felt proud of her friend as her political star rose and rose. Had grieved for her when Patrick died suddenly, and grieved even more when Elena was found dead at the bottom of the cliff. She’d wanted to go to Elena’s funeral, but had been in Spain chasing a story.

Now Cat was getting in touch with her again. Alex felt something shift inside her. Perhaps here was a chance for her to mend their relationship, for Cat to forgive her for pushing her away. Whatever the reason, Alex knew she’d been given a second chance.

‘Alex? Alex? Did you hear what I said?’

Alex blinked. ‘Sorry Bud. What were you saying?’

‘MEP? Wants to talk to you? Hasn’t got your number? Said she might have a story?’

‘Of course, the MEP—?’

‘Catriona Devonshire. Is she a friend of yours, then?’

‘She was.’

‘She was talking about an exclusive. For the paper. The paper you work for.’

Clever.

‘So you’ve got her number?’ Alex asked, as casually as she could.

‘Yep. Personal number, she said. Though God knows why she trusted me with it.’ He gave his bark of a laugh. ‘She must be desperate to talk to you.’ He picked up his e-cigarette, beginning to suck hard on it. ‘Bloody hell I hate these things,’ he said gloomily, vapours of steam curling up into the air. ‘Why does the sodding government have to spoil it for the rest of us?’ He took it out of his mouth and looked at it soulfully. ‘Nothing like the real thing.’ He put it back between his lips.

‘But we’re a lot healthier in this office, aren’t we?’ Alex said sweetly. ‘Now, Cat’s number?’

‘Cat is it now? Hang on. I wrote it down here somewhere.’ He began to sift through the papers on his desk. Not a chance, she thought. Her shoulders sagged.

‘Hah! Here we are.’ He waved a piece of paper triumphantly.

‘Thanks Bud.’ She breathed again as she plucked it from his fingers and turned to go.

‘And Alex?’

‘Yes?’ She tried not to laugh. Him and his e-cigarette just didn’t look cool.

‘She sounded desperate. Don’t know what she wanted, but stories involving corrupt MEPs always sell. Better if it’s a sex scandal. Didn’t she marry that much younger man recently?’

‘Mark Munro?’

‘That’s the one. Some city whizz-kid.’

‘They got hitched about this time last year. Whirlwind romance and a summer wedding abroad.’

‘And he’s younger than her.’ Bud looked thoughtful. ‘Maybe—’

Alex raised her eyebrows. ‘I thought The Post was a serious paper, not given to Hello!-style splashes or sidebars of shame reporting. And no one gives a toss if a man marries someone considerably younger than himself.’

‘Ach, cut your feminist whining. And in these days of falling circulation we’ll take anything.’ He grinned. ‘Almost anything. As long as you write it in the right way. So, if there’s a story there—’

She grinned back at him. ‘Don’t worry. You’ll be the last to know.’ She winked before closing the door, knowing the story about organ trafficking would have to wait until she’d seen Cat.

So the next day Alex found herself sitting on the white leather settee inside the Devonshires’ mews house. It was a house furnished for comfort: deep pile carpets, squashy sofas, one of those artificial fires that hung on the wall and cost a fortune. Tasteful paintings, from emerging artists she presumed, covered the neutral walls. A table here, a large pendant lamp there. A desk in the corner that was covered with bits of paper (rather like Bud’s, Alex thought) was the only discordant note in the room. But there was no mistaking the atmosphere of deep sadness; the grief like a weight pressing down and squeezing out the air.

Catriona Devonshire perched on the edge of the settee, sucking on a cigarette as if her life depended on it. The fingers that held the cigarette trembled. The nails were bitten, nail varnish chipped. Her husband, Mark, tall, dark-haired and with the boyish good looks of a thirty-something film actor, stood by the floor-to-ceiling window, his shoulders tense with … what? Worry? Anger? It was difficult to tell. She could still remember the snide headlines in the papers about cradle snatching and toy boys. His expression, as he looked at his wife, was one of concern. It must have been difficult for him – headlines when he married Catriona – headlines when her daughter died.

‘Coffee?’ said Catriona, suddenly leaping up, manically stubbing her cigarette out in an ashtray perched on the arm of the settee. The ashtray wobbled, but stayed put.

‘I’m fine, thank you,’ said Alex who could have done with something, but the preponderance of white around her made her certain she would spill it. ‘But you have one.’

‘I’ve already …’ she indicated a table by her side. ‘Everyone who comes makes me coffee. Even Mark makes me coffee. As if coffee could help.’ She sat down again. ‘Thanks for your letter, by the way. About Elena.’ Her eyes glistened.

‘It was the least I could do. I’m so sorry.’

‘Yes.’ She stared at nothing, twisting her hands together. She turned her head and looked directly at Alex. ‘I’ve missed you.’

‘Cat—’

‘You weren’t here when I needed you.’

‘I’m sorry. I’m so sorry.’ Alex wanted to say more: to explain about Sasha, about how her life had been, about how much she had missed her best friend. But today wasn’t about that, wasn’t about her. It was about Cat and what she, Alex, could do to help. She blinked away tears as she leaned forward. ‘Cat,’ she said gently, ‘you asked me to come here.’

‘Yes.’ She began tapping her foot.

‘Against my better judgement.’ This from Mark, who turned to give her what Alex could only think of as a sorrowful look mixed with annoyance. Interesting.

‘Mark, please—’

He sighed. ‘Oh Cat, you know my views on this.’

‘I do. But I have to try and understand, don’t you see? She was my daughter.’ Catriona scrabbled down the side of the leather cushion and brought out a rather squashed packet of cigarettes. Taking one out, she lit it with shaking hands. Alex caught Mark’s frown of disapproval. Surely he couldn’t begrudge her this?

He looked directly at Alex. ‘But to bring a journalist into the arena is asking for trouble.’ His voice was calm.

Alex wondered what arena she had been brought into. Was she here as a friend or as a journalist? It was obvious which side of the fence Mark thought she sat on. She shifted on her seat.

Catriona looked pleadingly at Mark. ‘She can help. She’s my oldest friend. I trust her.’

Mark shook his head. ‘Oh, very well, Cat. I can see you’re not going to budge.’

Catriona smiled sadly at Alex. ‘Mark doesn’t think I should be talking to you; he says we should go to the police. But I really don’t think they’ll do anything. When it happened, when Elena died …’ her voice faltered, ‘I told them it was impossible for Elena to have killed herself. She wasn’t depressed or anorexic or bulimic. She would have told me. She was looking forward to coming home. We were going skiing in the New Year with another couple and their two daughters. She was thinking about university. Everything. She had everything to live for.’ More desperate sucking on the cigarette. ‘She didn’t kill herself. I know she didn’t.’

Alex tried to keep her expression neutral. So this was what it was about: Catriona’s daughter. She had seen the results of the inquest and knew the verdict had been suicide.

‘Cat,’ she said. ‘The inquest—’

Catriona leapt off the sofa, knocking her cup over, spilling the coffee. ‘Fuck the inquest,’ she shouted.

The three of them watched as the brown liquid spread across the white leather. Alex wondered if it would stain and how much it would cost to get out.

Catriona looked out of the window. Alex knew she wasn’t seeing the London street, but was seeing her daughter, her beautiful 17-year-old daughter. ‘Fuck the inquest,’ she said, quietly this time.

‘Was it an accident?’ Alex kept her voice neutral.

Catriona rubbed her eyes with the heels of her hands.

Mark stood impassively. He sighed. ‘My wife thinks Elena was murdered,’ he said.

CHAPTER 3 (#ulink_b9586000-f2d8-5dc1-8244-5d5985122356)

ELENA (#ulink_b9586000-f2d8-5dc1-8244-5d5985122356)

May: twenty-nine weeks before she dies

It starts halfway through the summer term.

Wednesday at two o’clock in the afternoon. For weeks after, I knew I would remember the exact moment when I felt someone watching me. Stupid really. I thought it was bollocks when people said the hairs on the back of their neck stood up, but that’s exactly what I felt right at that moment.

I am plucking the petals off a daisy: ‘Knob.’ Pluck. ‘Dick.’ Pluck. ‘Knob.’ Pluck. ‘Dick’ … What does it matter? My mother’s husband, my new stepfather, is both of those – and more. I throw the daisy on the ground. How could she have done it? Replaced Dad like that? And he’s younger than her, for Christ’s sake. I want to cry.

I look around, take the scrunchie off my wrist and gather my blonde hair away from my face and up into a ponytail. I am sitting on the grass by the tennis courts revising for my AS levels. All four of them. That’s the trouble with this damn school – they push and push and push until you feel as though your head is going to fucking explode. Surely your brain can only take in so much knowledge? The trouble with my brain is that the knowledge goes in and then bleeds out. I like Art and English, but I know my teachers want me to take Physics and Maths to A level. What the fuck for? I don’t need Physics and Maths. I need English and Art. I want to take English and Art, no matter what my teachers or my mother and new stepfather say. My new stepfather. Even as I think it I still can’t believe it. What did Mum do that for? Was it for the sex? Eeugh, please. Too much information. Mark Munro makes pots and pots of money. Some sort of banker wanker. And the bloody headlines when they got married! Jeez! You’d think no one in the world had ever married anyone younger than themselves. But there was such a lot of crap written and spoken about it all, especially as Mum is well-known and a bit older. There are times when I feel quite sorry for them. But, still …

‘Get your exams then you’ll have choices,’ Mark said to me just after he’d married Mum, when he thought he could get away with trying to be something like a dad to me.

I wanted to tell him to get fucked. You aren’t my dad.

And it always makes my insides curl up when I think about my real dad: dead from an asthma attack when I was only ten. But I can remember him, I really can. And the good times, like when we went to the seaside together – just me and him – leaving Mum to network or phone Obama or something. We paddled and swam and built sandcastles and had ice cream and fish and chips and ate them sitting on the harbour wall, watching people go by.

He wouldn’t have made me come to this school.

I shade my eyes from the sun. The Queen Bees are lying some fifty metres away, stretched out sunbathing, shirts tucked under their bras, skirts hitched as high as they dare, books discarded by their sides. Looking like razor shells in a row on the sand. They don’t seem to care about revising. Lucky sods. The line shifts, sits up, looks around. Queen Bee Naomi Bishop’s plump lips (courtesy of a so-called doctor in a clinic on Harley Street) are moving and I guess she’s talking about catching the rays and the glories of having a tan. Or perhaps she’s whining about something more meaningful like what colour to paint her nails at the weekend, and, of course, the acolytes are breathing in every word. When I first arrived at the school, full of simmering resentment because I felt Mum had listened to Mark and had pushed me away, I was courted by the Queen Bees.

‘Come on, darling.’ Queen Bee Naomi always manages to make every statement sound like a command. ‘You want to be one of us. We know the best hot men to shag, the purest smack, and the best high living. You know it makes sense. We don’t ask everybody, you know. Only girls like us.’

I remember I gave them what I hoped was a cool look (Tara said later I had looked cool), even though my heart was beating, like, really, really fast, and said, ‘No thanks’. Just like that.

Naomi laughed, but I thought at the time it sounded a bit strained, you know?

‘You will so regret it,’ warned Jenni Lewis, Naomi’s right-hand bee. ‘You can’t survive on your own in this dump.’

‘I’ll try,’ I said. But I’m not one for cosy confidences, giggling late at night, sneaking out for sex with one of the sixth form boys. Not my style.

As I watch them, trying not to look as though I am another of the Queen Bees, Natasha Wetherby sits up, looks around, flicks her hair off her face. She smiles over at me and blows me a kiss. Yeah, right. I roll my eyes massively. Helen Clements, the mousy one of the group with hair that hangs like a pair of curtains and eyebrows thicker than Frida Kahlo, giggles: a high-pitched noise that carries over to where I’m sitting.

A second group of girls is over the other side of the tennis courts, laughing and talking. Two from my year sit on a bench, revising. Actually revising. Bloody hell. And further away, under a large oak tree, three or four boys from the Lower Sixth are lying down or are propped up on their elbows, chatting. One of them – Felix – is trying to smoke a cigarette, all cocky looks and holding it by his finger and thumb, but sort of looking around as if he’s frightened of being caught. Another of the boys is Theo, in skin-tight jeans and gun-hugging tee-shirt: the current Queen Bees’ heart-throb. I don’t like either of them that much. Felix looks a bit, I dunno, angry all the time, as though it wouldn’t take much for him to explode. He has a mean look in his eye. And Theo? Smarmy. Knows he’s buff, got half the girls here thinking he’s gorgeous. Doesn’t do a lot for me.

And Max is with them. He should be doing games or homework or something with his mates from Year 11, not hanging around with guys from the sixth form. They treat him as a sort of mascot for them, get him to run their errands. I sigh as he catches my eye. Mistake. He smiles that wobbly, tentative smile of his that makes him look as though he’s about to be hit with a big stick. He’s had a bit of a thing about me ever since I found him being pushed around by the likes of Naomi and Natasha. They’d ambushed him in the changing rooms and were pulling his clothes off him, taunting him, laughing at the size of his dick, that sort of thing. He’s a boy that invites taunts. But I couldn’t let it happen and I managed to get him away from them. Since then he’s had a bit of a thing for me.

Now he glances around to make sure no one’s looking at him – no one is, they never do – and he gives me a little wave. I smile back. What else can I do?

‘Hey, Lee,’ Naomi calls across. ‘Whatcha doing? Come over here.’

My best mate, Tara Johnson, who is trying to find a blade of grass wide enough to make a squealy-farty noise, looks at me; almost pleading with me to get up and join them so that she can follow too. She desperately wants to be part of the club. I sigh. I understand Tara’s feelings, I really do. She likes to belong, be liked, to be part of the gang. Always wants to but never quite manages it. Laughed at for being fat and frumpy, for not being pretty enough, fashionable enough or interesting enough. At our old school I felt sorry for her and could protect her, but here at The Drift, life isn’t so easy. Tara has to swim in a sea of piranhas. I mean, I do my best to defend and shield her, but it’s tough. Tara does not fit in. At all. Any more than I do, but I can pretend if I have to. Tara tends to wear her heart on her sleeve. But she’s a good and loyal friend sticking with me through thick and, quite literally, thin. Tara knows most of my secrets. Knows about my depression, my bouts of anorexia; knows the hard protective shell I’m growing after Mum’s marriage to Mark. The shrinks said the eating thing and the depression were because I didn’t grieve properly when Dad died. Mum went to pieces. I had to be strong. There was only her and me at that time, until Mark Munro came along. Then Mum got her life back on track and I was the one who went to pieces. Because I couldn’t control my environment, they said. The only thing I could control was my eating.

They had a point.

And it was so easy to shut myself in my room and devour pro-ana sites and think all that shit was real. Poor fuckers. I was lucky. Mum got me help and I came out the other side. I think it made me stronger. What doesn’t kill you and all that.

But then Mum’s job became more important; she became more important, and everybody wanted a piece of her. She’d get invited to all sorts of things, and at some fundraising event for a cancer charity she met Mark, and boom! that was it. I ceased to be the most important thing in her life and dropped down to third. Plus, I don’t know what Mark’s real motives are for marrying Mum. He’s a bit too young for her so I reckon he’s in it for the reflected glory or something. And I think he was quite pleased when Mum came up with the idea of sending me to The Drift. ‘It’s a good school and you’re really clever,’ she said. ‘And I don’t want to leave you on your own when I’m away, and I can’t expect Mark to look after you.’

Guess not.

And she said she’d spoken to Tara’s mum (who writes the most salacious bonkbusters and has made a fortune) who was looking for a new school for Tara, and they both agreed The Drift – in the back of beyond and then some – was a good idea.

So now I’m here.

Sometimes I want to blame Mark for it all, and hope that one day Mum’ll see sense. Sometimes I think Mum really believes she has my interests at heart. Sometimes I think she and Mark really do love each other. And sometimes I see pigs flying.

But I long for my old London school in the middle of the city: a vibrant centre, full of life. I miss the constant noise, colour, and the different mix of people. I like the never-ending procession of traffic, the street lights that block out the sky, the green parks that give areas of calm among the madness; whereas here it’s dark nights, starry skies, hooting owls, and spoilt rich kids of fading TV stars or blockhead footballers. And the rich kids, who all seem to have been together since day one at the school, and often before that – attended the same prep school, darling – are obsessed with looks and fashion. Tara doesn’t stand a chance. And I don’t want to be a clone. A drone. A Queen Bee. After all, I’ve been there, done all that dieting stuff and it almost killed me. Never again. And as for boys, I can’t see what all the fuss is about. And that’s the problem. I have naff all in common with the Queen Bees, or with any of them. Nor does Tara, but she can’t see that.

‘Come on Lee, come over here. Leave fatso where she is.’ Naomi laughs, and the other members of the gang sitting with her dutifully follow suit.

‘No thanks, Naomi,’ I shout back. ‘I want to stay with my friend. She’s more interesting than you.’ And I grin like a mad woman.

Naomi waves, not fazed by or bothered by the sarcasm. ‘Suit yourself.’

I look at Tara, see her bottom lip wobble. ‘Come on, Tar, they’re not worth it.’

‘Easy for you to say,’ sniffs my friend. ‘You could go and be at one with the Queen Bees any time you like. I haven’t got a fucking chance.’

‘Tar. Haven’t heard you swear before.’ I am admiring.

‘Now you have.’ She is grumpy.

My phone pings.

hi gorgeous.

I look around again. Heart-throb Theo is looking straight at me. It must have been his eyes I felt on me. He smiles.

Oh God, I can do without this. As I say, neither he nor any of his mates interests me. No time for them. He might be the hottest dude in town but, you know, the Queen Bees can have him. I am about to fling my phone down on the grass when I think of something – it might be worth a flirtation just to piss off the Queen Bees. Yeah, could be fun. I text back, hiding a smile.

hi.

I don’t have to wait long for his reply.

wanna hook up later?

Nice chat-up line.

maybe

the old summerhouse?

Original in his destinations too. He sure knows how to woo a girl.

maybe

’bout 8?

maybe. If I can get out

course you can. see you then.

Actually, I feel normal doing that. Not that I have any intention of going. I look across at him. He gives me a small wave and then turns back to talk to his group of mates.

They are laughing, and my face burns.

The skin on the back of my neck prickles. I know someone is watching me. And it’s not Theo.

Hey you, it’s me.

That was when it first started, wasn’t it? You … lying there on the grass, long, tanned legs stretched out in front of you, talking to Tara, texting that boy. And there I was. Looking at you. I couldn’t stop it you know, looking and wondering about you. Thinking, you don’t know how gorgeous you are. Wondering if you would let me get close to you or if you wouldn’t want to know. That’s when I thought: I will try. I couldn’t waste the opportunity. You see, I thought my life wasn’t going anywhere, that I was trapped. But I was frightened, worried about how you might react if I made a move. Then I told myself I shouldn’t worry about it, that I should go slowly and test the water. I looked at you again. You felt me looking at you, didn’t you? You even turned and looked at me, but didn’t see me.

But you didn’t know then that it was me.

CHAPTER 4 (#ulink_3e87400d-e90a-5bea-a5e5-fbe36a675955)

June

Murdered.

The blunt word hung heavy in the air.

‘Cat,’ began Alex, her voice still gentle, ‘is that right?’ She’d had plenty experience of living with the thought that someone you loved had been murdered. It was something that never left you: that feeling of helplessness; the useless ‘if only’ thoughts that came in the depths of the night. Alex was still trying to live with all of that.

Catriona sighed long and hard, then sat up straight, her mouth in a determined line. ‘Yes. It is. I feel it in here.’ She thumped her breastbone with her fist. ‘Elena wouldn’t have done that to me. We went through a lot together, especially after her dad died. She wouldn’t leave me this way.’

Alex nodded and thought back to what she knew about the 17-year-old’s death. The teenager had been found in the early morning at the bottom of cliffs not far from her very exclusive boarding school, only days before the school broke up for the Christmas holidays. Alex could imagine what sort of Christmas the Devonshires would have had. She’d been through many of those when her sister’s children had disappeared. She frowned. ‘Cat, forgive me but the police found a text on her phone, didn’t they? To you from her?’

‘Yes, there was no doubt about that. But—’

‘And she had been depressed and anorexic or bulimic or both,’ Mark Munro cut across his wife.

‘No, she had not been either of those things.’ Cat balled her fists. ‘She was well. Completely well.’ The strain on her face deepened the lines around her eyes.

Alex frowned. ‘What made you think she was ill, Mark?’

‘I—’ His eyes darted around the room.

‘Mark?’ Cat’s voice was sharp.

‘Catriona. Can we do this when we’re alone, please?’ He had regained control and his voice was stern.

Cat looked at him then shook her head. ‘No. I want Alex to help me. Us. I don’t want to hide anything from her. But if you’re hiding something from me—’

He stared at Cat for a few moments before wiping his face wearily with one hand. ‘Very well. If you must know I spoke to her. A couple of weeks before … before she died.’

‘What? You never told me that.’

‘I didn’t think it would get this far.’ He went over to a cupboard in the corner and took out a bottle of whisky. ‘Drink?’

‘Mark, you can’t solve this with a drink.’ She let out a hiss through her teeth.

‘I’m not, Catriona. I just want a whisky, that’s all. It’s not a crime.’ He banged a tumbler down on the top of the cupboard. ‘Alex?’

‘Not for me, thank you.’

‘Mark.’ Cat again, pain naked on her face. ‘What do you mean you spoke to her? Why didn’t you tell me?’

‘I didn’t want to upset you.’

‘And did she say she was ill?’ interjected Alex. She had to get a grip on this, see what she might be getting herself into.

Mark poured himself a drink then drank it down in one swallow. ‘Not in so many words, no.’ He poured himself another couple of fingers.

‘What does that mean?’ demanded Cat. ‘What the hell does that mean? And why didn’t you say something sooner? Why didn’t it come up at the inquest?’

‘Nobody asked me, and as you know, I didn’t go to the inquest. I was abroad at the time and it wasn’t thought necessary to call me. You know all this,’ he said simply. ‘And I didn’t want to make things any worse than they were. The text had been found and that was that.’

He was too smooth.

‘So you thought,’ said Cat, bitterly.

‘Mark,’ Alex made her voice firm, ‘what made you think Elena was ill?’

He shrugged. ‘Just the way she was talking. A bit lost, a bit helpless. She said things hadn’t been going well at school. I suggested she talk to her housemother or whatever they call them at the school, that’s what they’re there for.’

‘That’s what I’m here for,’ said Cat, a break in her voice. ‘I’m her mother.’

‘But you weren’t around, darling, were you?’ her husband said, gently. ‘You were in Brussels. Some high-level meeting or something – I can’t remember now – Elena said she had tried to speak to you but your mobile was off all the time.’

How could the man be so cruel? thought Alex. Did he realize what he was doing to his wife?

‘The migrant crisis. All those displaced people. That’s what it was. I wanted to help. But I—’ Cat looked bewildered. ‘If she’d left a message or something I’d’ve got back to her. She knew that. I always did.’

‘But she phoned me instead,’ said Mark.

‘And you didn’t tell me?’

‘We thought it best not to. You were busy, had a lot on your plate; we thought it was best you weren’t worried.’

‘My daughter was feeling suicidal and you thought it was best not to worry me?’ The fury was etched deep on Cat’s face.

Mark shook his head. ‘No, no, you’re not listening.’ He kept calm. ‘She never said she was suicidal, only that things weren’t going well and she wasn’t eating properly.’

‘But—’

‘Mark, Cat.’ Alex knew if she didn’t bring the conversation back to the point the two of them would be going round and round in circles and they wouldn’t get anywhere. ‘We can look into Elena’s state of mind just before she died. What I want to know is why you, Cat, think Elena was murdered?’

Cat let out a deep breath and leaned back into the cushions. ‘You will help, then? You are interested?’ She reached out and took Alex’s hands, squeezing them tightly. ‘I knew you would understand. That I could trust you. We still have it, don’t we? That tie, that closeness?’

Alex nodded. It was true. It was as if they had spoken only yesterday.

‘And you know what it’s like to lose people close to you. You know how I feel.’

‘For God’s sake.’ Mark’s calm veneer suddenly cracked. ‘I know how you feel. Don’t leave me out of this.’

‘I’m not leaving you out of this, Mark, but you still think she killed herself. I don’t.’ She looked at Alex. ‘The inquest was last week.’ She visibly winced. ‘It was horrible. Having to relive it all, listen to the lies about Elena. The details. The pitying look from the coroner as she told everyone Elena had thrown herself from the cliff. The reporter scribbling down the details in his notebook so they could fill a page of their grubby little paper.’ Cat’s eyes were glistening. ‘And that text. The one they found on her phone. I never got it.’

‘Are you sure?’

‘Of course I’m sure. I’d have remembered if I’d got a text like that. We were always texting, you see. The last time I heard from her was about ten days before she died. But I deleted it.’ She began to cry and rock herself backwards and forwards. ‘I deleted it because the storage on my phone was almost full. I deleted it. I keep texts from my secretary, but I deleted my daughter’s texts.’

Alex put a hand on her arm. ‘Cat, it’s all right.’

‘No it’s not all right.’ Gulping sobs escaped her.

‘Tell me what the texts said.’

‘Do we have to drag all this up?’

Cat jerked her head up. ‘Yes we do, Mark.’ She looked at Alex. ‘She said she was looking forward to coming home. Said there were things going on at the school that she had to tell me about, worrying things, she said. She said …’ Cat gulped back tears, ‘she said she had to talk to me. I asked her to tell me there and then but she wouldn’t.’ She looked at Mark. ‘But nothing about not eating or being depressed.’

Out of the corner of her eye Alex could see Mark trying to catch her eye as if to say, ‘See, no definite proof.’

‘And you don’t know what she was referring to?’

‘No. But then I got this.’

Suddenly she had her mobile phone in her hand and she turned the screen towards Alex. ‘Here. Look.’

Alex looked. It was a Facebook tribute page – she had seen quite a few of them in her time when she’d written stories on young people who had died – a special page dedicated to that person. She took the phone from Cat and scrolled through the page. It was full of the usual: ‘I love you hun RIP;You’re the best, we’ll miss ya;You’ll be an angel in heaven now.’

She looked up at Cat. ‘It’s great your daughter’s friends cared, but—’

‘Oh for goodness’ sake.’ Cat snatched the phone back and scrolled down, her finger moving at a frantic pace. ‘There. See.’ She thrust the phone at Alex.

Elena did not kill herself

The comment was prefaced by a picture of a silhouette – standard practice when people didn’t want a profile photo – and the name ‘Kiki Godwin’.

‘And again. Look, underneath that message.’ Cat’s eyes were bright, feverish, her hands shaking. ‘Another one.’

It’s true. Elena did not kill herself.

Again, the same silhouette picture, the same name: ‘Kiki Godwin’.

‘And if you look, everybody else posted their messages just after Elena died and in the following few weeks. These two were posted four days ago, after the inquest.’ Her excitement was palpable.

Alex clicked on Kiki Godwin’s name. It took her to a Facebook page that echoed the silhouette but had no details about Kiki Godwin. She took her own phone out of her bag, opened the Facebook app and found Kiki’s name herself. Then she sent her a friend request. Let’s see if we get any reply to that, she thought.

‘I’m guessing’, said Alex, putting her phone away, ‘you don’t know who Kiki is?’

‘No. Not at all. I presume it’s one of her friends, but then, why doesn’t she have a profile?’

‘And have you shown this to the police?’

Cat met her eyes. ‘No. Not yet. I don’t trust them like I trust you. Them and their great size thirteen boots. No finesse, no subtlety. All they’d do is scare everyone off. Nobody would talk to them, least of all Kiki Godwin, whoever she – or possibly he – might be. Anyway, they wouldn’t believe me. Even my own husband doesn’t believe me. No, I want you to look into it, Alex. Please.’

‘But Cat, the police have resources, know-how, manpower and all that.’

‘That’s what I keep telling her,’ said Mark, now onto his third – or was it fourth? – whisky. ‘Let the coppers handle it. Show them that message. Though personally I think it’s one of those trolls. You get them all the time on these sorts of pages. We’re lucky it hasn’t been worse. Sometimes there’s all sorts of filth there too. You can’t believe what people can be like.’

‘Mark, please.’

‘I’m sorry Cat, but it’s true. It should be in the hands of the police.’

‘Who think she killed herself.’

‘But you won’t have it.’ Mark tossed more whisky down his throat.

Alex thought of the articles she should be pitching, the money she should be earning. How Mark could well be right and it was a troll. It did happen; not so long ago some inadequate youth had been jailed for mocking the death of a teenager who’d thrown herself in front of a train.

She tried again. ‘Cat, you should tell the police. That’s the best. Let them deal with it. You’re a politician; it’ll go to the top of the pile.’

Cat gave a deep sigh and sat back on the settee, a steely look in her eyes. ‘They have closed the case and they won’t want to reopen it. Look, go and take a look around for me. Spend a couple of days up there, spy out the ground. Please. You can ask the right questions; I know you can. That’s all I’m asking. A few questions. You’re good at that.’

Alex looked at her helplessly. ‘Cat, I don’t know …’

All at once Cat smiled gleefully, like a little child, her eyes feverishly bright. ‘But I do. I know you can help. And your editor – Bud, isn’t it? – he thought there could be a good story in it. He was interested.’

Of course he was. He’d said as much to her. But he didn’t have to come and see the raw emotions on Cat’s face, the amount of hope she had.

‘Look,’ her friend continued, ‘we’ve even got a little cottage up there where you can stay; it’s one we use when we go – used to go – to see Elena on her free weekends. We rent it out, but the couple who were supposed to be staying there at the moment cancelled. Wedding or something. Please, Alex. I’m begging you. Two weeks – one week – and if you’re getting nowhere then call it a day. I’ll try and accept it … Elena’s death. I’ll show the Facebook thing to the police and see if they’ll do anything. Though I know they won’t.’

‘An offer you can barely refuse, hmm? Free accommodation and story you could sell anywhere,’ said Mark, looking at Alex with a barely concealed sneer.

Alex bridled.

‘Mark, stop it. Please, Alex, say you’ll do it?’

‘I’ll have to think about it, Cat.’ Did she, though? Here was a chance to help her friend – her oldest friend – find out the truth about her daughter’s death, even if that truth were unpalatable. And if she found out that Elena did throw herself off the cliff then at least Cat would know for sure. She wouldn’t live a half-life like she, Alex, had done. And she hated seeing the pain Cat was in. Perhaps she could do something to make that a little better. Then there was Elena. A beautiful girl who’d had a bright future in front of her. A girl similar in age to Gus. A girl who had grit and determination and who’d coped with the death of her father and a debilitating eating disorder. Elena deserved her help too. And she knew if it had been the other way round, if she was asking Cat for help with Gus, Cat wouldn’t hesitate.

And what about the mysterious message? The reclusive Kiki Godwin? Alex’s fingers started tingling, a surge of adrenaline in her gut: sure signs she was getting excited about a story. What if Cat was right? What if Elena’s death wasn’t suicide and this Kiki Godwin had some information?

‘It could be a good story, Alex. And I know you’ll be truthful, not sensationalist. It’ll be an exclusive. And you can have an interview with me and Mark, whatever you find out.’

‘Oh, count me out, Cat,’ said Mark, anger evident in his voice. ‘I can go so far but not that far, thank you. I’m not subscribing to this charade any longer.’ He took a few breaths, which seemed to calm him. ‘Please, Cat, let it go. You’ll make yourself ill.’

Cat stood and walked purposefully across to her husband. She took his hands in hers. ‘I have to do this, please Mark, please. I need your support.’ She leaned into his body.

Alex watched as Mark’s anger subsided. Tenderly he tucked a lock of Cat’s hair behind her ear and planted a kiss on her forehead. ‘For you, Cat. For you.’

Cat turned to Alex. ‘One other thing that makes me think – no, know – that Elena didn’t throw herself off that cliff. She was scared of heights. Terrified. She wouldn’t even go to the top of the slide on Brighton beach last year, that’s how terrified she was. She wouldn’t have gone anywhere near that edge.’

CHAPTER 5 (#ulink_ee56cc97-7041-5a2b-9c22-a21df0d28ceb)

It was no wonder Cat Devonshire was described by the broadsheets as an ‘up and coming’ Member of the European Parliament with a sharp brain and incisive mind, thought Alex, as she drove along the M11 towards East Anglia. Once Alex had agreed she would go and look into Elena’s death, Cat had gone into overdrive: organizing the house in Hallow’s Edge for her, making sure she had enough cash, promising to email over any documents that could be useful. And the last few days had been a whirlwind, what with preparing to leave her tiny ground floor flat (with garden) in West Dulwich (Tulse Hill, if she were honest), making sure the cat would be fed for however long she was to be away, telling Bud she was going up to North Norfolk and, yes, there could be a story in it, and managing to get custody of a company credit card. Bud had been rather begrudging about that, it had to be said. She did have to come back with a story of some sort now.

The only downside was that it had been difficult to explain to Sasha that she didn’t know when she was going to be able to visit again. But tell her she had, and she even thought she had seen tears in Sasha’s eyes as she left.

The heat was building, layer upon layer, the sky a pale blue as if the sun had bleached the colour out of it. The air vents were blowing warm air around the car and for the umpteenth time she wished she’d had the air-conditioning seen to. The motorway was long and boring and she still had a way to go.

She pressed the CD button and David Bowie’s voice filled the car. That was better. Now she wouldn’t think about Sasha, or about her own 18-year-old son who was somewhere in Europe trying to find himself. She hadn’t heard from him since he’d got the ferry to France two weeks earlier.

‘I’ll be fine Mum,’ he’d said as he heaved his rucksack onto his back ready to catch the bus to Dover. ‘I need to get away, you know that. Exams can wait. And I’ll FaceTime you.’ Then he gave her a kiss on her cheek and went out of the house – whistling. Whistling! As if last night’s quarrel had never happened.

It had started after supper when she took his clean washing into his bedroom for him to stuff into his rucksack.

‘Mum,’ he said, ‘I know you don’t like talking about my dad, which is why I hardly ever ask about him, but—’ He stopped and began to chew his lip.

‘It’s okay,’ Alex said, unnecessarily refolding a tee-shirt and admiring the way she spoke so calmly. ‘I understand. I just thought we had each other all these years and we were a unit. A family.’ And she had never wanted to go into details about how Gus had been conceived during a drunken, drug-fuelled one-night stand in Ibiza.

‘We are. A unit, I mean. You are my family, Mum, and you’ve been bloody brilliant. It’s just that I want to know where I come from. Who I am.’ He didn’t look at her as he carried on packing.

Alex tried to smile. ‘Darling, you are a wonderful person and—’

‘Mum. Who is he?’

‘Gus.’ How she so didn’t want to do this. ‘What’s brought this on?’

‘Tell me. You see, when I was younger I figured he was probably a Premiership footballer, or an actor, or a rock star.’ He laughed. ‘But then as I got older I thought maybe he was a murderer or a kiddie fiddler.’

‘His name was Steve,’ she said, smoothing the tee-shirt flat.

‘Steve who?’

‘I don’t know.’

He turned to look at her. ‘You must.’

She shook her head. ‘No, I don’t. I was in Ibiza on a newspaper jolly. We went to a club. He was the DJ there. I was young; it was my first taste of freedom; I didn’t know what I was doing – there was free alcohol, some drugs – and I ended up going back to Steve’s place.’ Every word made her feel ashamed.

‘And you never wanted to find him?’

‘No.’

‘Not even for my sake?’

‘No.’

‘That’s so selfish, Mum, so bloody selfish.’ She could see tears in his eyes.

‘I’m sorry Gus; I never wanted to hurt you. I thought it was best left alone.’ She wanted to cry too.

‘And you wouldn’t have said anything, even now, would you? Even now that I’m eighteen and about to go off travelling. Unless I’d asked.’

‘Gus—’

‘Well, I’ve got news for you. I’m going to find him.’

‘How?’

‘With the help of a friend,’ he said coldly, before turning away from her.

She left his room.

Now she turned up the volume on the CD player, drumming her fingers on the steering wheel in time to Bowie, singing along with him, loudly and tunelessly: determined not to worry about Gus. He was a grown-up now.

Merging onto the A11 she began to feel she was in East Anglia proper, for the first time in two years. She thought about Cat, about Mark, and about Elena. At first sight, Elena’s death seemed such an open-and-shut case. The coroner had thought so, too. A teenager for whom everything had got too much. A teenager with problems. Was that what had made her take her own life? But why so close to Christmas? And what about the text that had been found on her phone?

Mum, I don’t think I can do this any more.

On her phone but not sent. Why?

She’d been depressed in the past. Had suffered from anorexia. Alex drummed her fingers on the steering wheel. Christmas – the lead up, the day itself – was always stressful, always the time when domestic violence increased, marriages broke up, people killed themselves; why shouldn’t it be the season when Elena felt she couldn’t go on? She’d crept out of school in the middle of the night (how easy was that these days? In all honesty, Alex’s experience of boarding schools was Enid Blyton’s Malory Towers books with their jolly midnight feasts and Harry Potter and magic goings-on – not exactly an in-depth knowledge), found her way to the end of the road that ended abruptly, falling away to the beach. Then she’d apparently thrown herself off the cliff road and down onto the rocks below before the tide had come in and dragged her poor broken body out, then in again; leaving it on the shoreline waiting to be found. What a waste.

According to the newspaper article about the inquest, it was an open-and-shut case. And, of course, her mother couldn’t believe her beloved daughter would do such a thing, would reach such a deep and dark place that she could see no other way out.

Yet Cat’s absolute conviction that it wasn’t so open-and-shut had begun to chip away at Alex. Who had Elena spoken to in those last days, hours? Had the school noticed anything amiss? Had she become depressed and anorexic again, or was that just a convenient excuse trotted out by the school, the police, the authorities? The inquest seemed to exonerate the school of all blame. But still. Wouldn’t they have noticed something about her behaviour in the days leading up to her death? Shouldn’t they have noticed? Would you pay the thirty-odd thousand pounds to the school if you didn’t expect some modicum of pastoral care? And she knew how much Cat regretted sending Elena to the boarding school. ‘It was because I was away so much,’ she’d told Alex, as if wanting Alex to absolve her from some mortal sin. ‘I – we – thought it was best. And I had just got married.’ She’d looked shamefaced. ‘So selfish. Now I wish I could have all that time back with her, all the growing up I missed. All the worries she must have had going to a new school. And what did I do? Texted her. Some mother I am.’

Through Thetford and after – the tall conifers at either side of the road reaching up to the sky, and David Bowie changed for Lou Reed. She ought to try and get into some of the new music, but she liked the old rockers. Always had since hearing them on her father’s old record player as a child.

The road stretched on as the sun became even higher in the sky. Skirting round Norwich – a city she loved and had missed – then up to the flat of The Broads, passing farm shops, bed and breakfast places, garden centres, a huge solar farm that went on for miles, and churches, always churches, some with the unusual round tower. Then on to the busy town of Wroxham, teeming with early summer visitors who spilled from the paths onto the narrow roads. As she went over the little bridge she glanced at where the boats were moored and thought about how she had never taken a boat out on The Broads. Maybe, she mused, she would rectify that this summer. Perhaps take … who? With a lurch she realized there was no one she could take. Gus would be away for the whole summer, and Sasha? Well, Sasha wasn’t likely to be out on day release or whatever they called it anytime soon.

Her mind drifted back to her friend.

‘Would you like to see Elena’s bedroom?’ Cat had asked.

Alex nodded. Of course she would; it might give her a bit of an insight into the teenager she had never known.

She followed Cat upstairs, and stood for a moment on the threshold of the room. She wanted to get a sense of her daughter, a feel for her. What sort of girl had she been? She knew how difficult it was being a teenager in this day and age – Gus proved it – so she had sympathy with both Elena and Cat as far as that was concerned. It was hard growing up in a world that expected you to be perfect, expected you to either succeed well or fail badly; there seemed to be no middle ground.

It was obvious Cat had changed nothing since Elena had left for the start of the Christmas term the year before. Alex had a sudden flashback to Sasha who hadn’t been able to give away Harry and Millie’s clothes and toys for years. Eventually Alex had stepped in and taken all the stuff to the Red Cross shop in Sole Bay. It had broken Sasha even more.

Elena’s room was that of a typical teenager, though maybe less messy, as she hadn’t been there the whole time. Posters of bands Alex hadn’t heard of were Blu-tacked on the walls. A flowery vintage cover on her bed. Poetry books, Harry Potter, The Twilight series, Judy Blume books were lined up on the shelves. Adult books too: Belinda Bauer, Lee Child, Antonia Honeywell, Jojo Moyes. An expensive iPod dock and computer sat on a sleek glass desk. A laptop made up the triumvirate.

‘I presume she had a computer at school? And phone?’ asked Alex.

‘Oh yes,’ said Cat, sitting on the bed, her hands absent-mindedly brushing the duvet cover, tears not far from her eyes. ‘The laptop on her desk there, that’s what she used. The police took it away but couldn’t find anything. The phone’s in her drawer. I didn’t want to look through it.’ She swallowed. ‘It seemed too much like prying.’

‘Hmm.’ Alex knew that if there was no suspicion of foul play the police would have had only a cursory look at Elena’s electronic stuff; they didn’t have the resources to do a thorough job unless it was absolutely necessary.

‘I come and sleep in here sometimes,’ Cat’s voice was faint. Unbearably sad. ‘To be near her. I won’t let anyone wash the sheets. I can still smell her, just. I don’t want to lose that smell. Sometimes, if I don’t look at a photograph of her I feel as though I might lose what she looked like. Forget her face. The scar on her knee from where she fell off her bike trying to ride it without stabilizers for the first time. The birthmark on the inside of her wrist. The way one ear sticks out more than the other. Stuck out more than the other. Then I can’t stop crying.’ She looked up at Alex. ‘That’s the trouble. I can’t stop crying.’

‘I know. I understand.’ Alex nodded.

‘I know you do. You had to help Sasha through everything, despite what happened at the end. And you’ve got Gus. I know you would do anything to keep him safe. I couldn’t keep Elena safe, that’s why I’m begging you to help me. Please.’

There was no way, Alex knew, she was not going to help Cat now.

‘Would you mind if I took the laptop and phone away with me? To have a look, see what she was doing at school?’

For a moment her friend looked panicked. ‘I don’t know … I’m not sure …’

‘It might help me get a picture of her life, that’s all,’ said Alex gently, knowing the tremor in Cat’s voice was, after all she had said, due to the possibility of losing something of her daughter’s. ‘I won’t do any harm, or destroy anything, I promise.’

‘But her passwords?’

‘Leave that to me,’ said Alex.

‘She wanted to be an artist, you know. She was good enough too,’ said Cat, her face sad. ‘That’s one of hers. It’s Hallow’s Edge.’

She pointed to a painting on the wall. Oil. A landscape. A beach, the sea, white horses, groynes, all painted as if the artist was sitting on the beach. And in the corner, on the edge of the cliff … was that a tiny figure? Alex moved nearer to peer at it, but the picture dissolved into a mass of paint blobs. She moved away, further across the room, and the blobs morphed into a figure that seemed to be wearing a long coat and scarf. It could have been anybody.

‘She painted that in her last term; it was part of her Art A level. They let me bring it home. It’s lovely, isn’t it? I think it’s somewhere near the school, but—’ Catriona looked as though she was about to cry.

‘Who’s the figure in the top corner?’

Cat shook her head. ‘No idea.’ She got up and stood next to Alex. ‘I hadn’t noticed it. I didn’t look closely enough. I didn’t take enough interest. Not then.’ She gulped back a sob.

‘Cat …’ Alex hesitated, not wanting to appear intrusive. ‘Would you mind if I took a photograph of the painting?’

‘No. If you think it’ll help in some way, any way, then please do.’

Alex snapped the painting. ‘And do you have a recent picture of Elena? I’ll give it back to you, I promise.’

Catriona nodded and went out of Elena’s bedroom, coming back with a photo frame. ‘This is the most recent one I have of her.’ Her voice broke. ‘It was taken during the summer holidays. We managed a couple of days in Dorset. Lovely little village called Kimmeridge. She seemed relaxed for the first time in ages.’

Elena had been strikingly beautiful. Long blonde hair framing a heart-shaped face with angular cheekbones. Dark brown eyes. A slight smile curved a rosebud mouth.

‘That’s odd,’ said Cat, peering at the picture. ‘I hadn’t thought about that before.’

‘What’s that?’

She pointed at the photo. ‘See? The ring?’

Alex looked. Elena was holding one hand up to the camera. She might have been waving or telling her mother not to take the picture. On the fourth finger of her right hand was an oddly shaped silver ring. ‘Looks like one of those his and hers eternity rings. Seems as though there should be a partner to it, doesn’t it?’

‘That’s what I said to Elena when I saw it. I think she was given it by somebody for her birthday. She gave me one of her mysterious smiles so I backed off. Didn’t want to interfere. I wish I’d asked her more.’

Oh, Alex knew all about not interfering. Sometimes, though, you had to. ‘And?’

‘She was wearing it all summer holidays, wouldn’t take it off. And she kept stroking it when she thought I wasn’t looking. It was obviously very important to her. The thing is …’ she paused, ‘there was no sign of it in any of her stuff they gave back to me.’

‘Maybe she lost it.’ Or perhaps it had come off her finger as her body was battered by the sea.

‘Maybe.’ Cat was thoughtful. She traced the outline of her daughter’s face. ‘I had the impression it was something she would keep through thick and thin. As I say, something really important.’ She shrugged. ‘Oh well, maybe it’s nothing. Maybe she did lose it.’

The traffic was heavy now as she passed through some of The Broads villages before arriving at the real flatlands of Norfolk and she knew she wasn’t too far away from Hallow’s Edge. She could feel the lightness of air, the big sky above, the space around her, and she remembered why she loved East Anglia so.

After saying goodbye to Cat and Mark, Alex made a call and then went to Streatham, to an ordinary residential road. The house she was looking for was halfway up and part of a row of terraces with each tiny front garden having at least two wheelie bins. Number 102 had a decrepit armchair as a garden feature as well. A blanket hung across the ground floor window in place of curtains. She walked up the path and knocked.

A tall thin woman of about twenty-five whose pallor indicated she hardly ever saw daylight opened the door. She was wearing faded jeans and a tee-shirt with the dates of a long-gone music tour inscribed on it.

‘Hey, Honey,’ said Alex.

‘Yeah. It’s early, y’know?’

Alex grimaced. ‘Sorry, I do know. But I wanted to get it to you as soon as.’

Honey rubbed the top of her head making her ginger crop stand up in spikes. ‘Sure.’ She yawned, widely, showing two sets of perfect teeth. ‘I’ll do my best.’ She held out her hand. ‘Give it here.’

Alex handed over Elena’s laptop and phone. ‘I need them back in pristine condition, Honey,’ she warned.

‘Come on, Alex, you know me. No one will ever know I’ve been in there.’

Alex smiled. She really did trust this hacker who’d somehow almost managed to stay below the radar of the authorities since she was sixteen. The one (and seemingly only) time she’d come a cropper was when Alex had found her after a tip-off for a story she was doing at the time about cyber security, and she’d managed to get Honey off the hook with the coppers in return for information. Honey had been grateful ever since.

She was on the road that wound along the Norfolk coast, sometimes going near enough to the sea, most of the time winding through flat acres of fields. Eventually she saw a signpost for Hallow’s Edge and turned into the narrow road with hedges either side. For about half a mile there was nothing, then she spied a farm set back from the road, a couple of flint cottages and a modern bungalow. It really was as if she was entering a time warp. She drove slowly, praying she wouldn’t meet a tractor coming the other way, and stopped the car by a curved flint wall before getting out. The heat hit her like a sledgehammer.

There it was. The Drift. Elena’s school. A school for the privileged. Beautiful. It was at the end of a long gravel drive, lined with lime trees, that swept up to the front of the house. Two of the four brick and flint wings of the house made a graceful curve. Large wooden front door in the middle. Magnificent thatched roof. Heavy on the insurance. Alex knew there were two other wings curving at the back with beautiful views over the coastline and the sea. Shaped like a butterfly, it was built during the Arts and Craft movement. She knew all this because she’d looked it up online, and the pictures had been fantastic. She’d had to look up about the Arts and Craft movement, but, hey, that was what Wikipedia was for.

Alex breathed in deeply. East Anglian air. More specifically, North Norfolk air with its taste of salt and freedom and sense of space. There was a reason why everybody talked about the wide East Anglian skies – the world seemed to go on forever. She closed her eyes, continuing to breathe in the air that, despite its heat, felt cleaner and fresher than the diesel, spices, and dirt of London. She had missed this. For all the ghastly events of two years ago, she had missed this. Of course, this trip to find out more about Elena’s death was another burst of conscience easing, but, who knew, maybe some good could come of it, if only to help Cat.

‘Hi.’

She turned towards the voice and found herself looking at a boy – teenager, a young man – who could only be described as beautiful. Thick dark hair was brushed away from his forehead, cheekbones were sharp, top lip was slightly fuller than the bottom. Chocolate-brown eyes that were fringed by long, girlish lashes appraised her. He held a cigarette loosely between his fingers. For a moment Alex felt awkward, gauche even. Then she told herself not to be so silly. This was an adolescent. A beautiful one, but one who was about Gus’s age. Younger. ‘Hallo,’ she said, smiling.

‘Did you want some help? Only …’ The boy raised his eyebrows. Looked her up and down, slowly.

She felt discomforted. ‘Only what?’

‘You looked … lost, that’s all.’ He smiled back at her. Dazzling.

‘No, not lost,’ she said. ‘Only looking. It’s a beautiful building.’

‘What?’ He followed her gaze. ‘Oh, yeah. That.’ He shrugged. ‘It’s school, that’s all I know.’